Abstract

Nanotechnology offers several attractive design features that have prompted its exploration for cancer diagnosis and treatment. Nano-sized drugs have a large loading capacity, the ability to protect the payload from degradation, a large surface on which to conjugate targeting ligands and controlled or sustained release. Nano-sized drugs also leak preferentially into tumor tissue through permeable tumor vessels and are then retained in the tumor bed due to reduced lymphatic drainage. This process is known as ‘the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect’. However, while the EPR effect is widely held to improve delivery of nano-drugs to tumors, it in fact offers less than a 2-fold increase in nano-drug delivery compared with critical normal organs, resulting in drug concentrations that are not sufficient for curing most of cancers. In this review, we first overview various barriers for nano-sized drug delivery with an emphasis on the capillary wall’s resistance, the main obstacle to delivering drugs. Then, we discuss current regulatory issues facing nanomedicine. Finally, we discuss how to make the delivery of nano-sized drugs to tumors more effective by building on the EPR effect.

Keywords: nano-drug, cancer, enhanced permeability and retention effect, pharmacokinetics, regulatory approval

1. INTRODUCTION

Solid tumors often develop drug resistance due to a number of well-known mechanisms, including alternative drug export pumps, alterations in gene expression that render the tumor insensitive, changes in the metabolic pathways that affect the metabolism of cytotoxic drugs, deregulation of DNA repair, and subsequent apoptosis induction. Along with these well-described mechanisms, the tumor microenvironment plays an important role in drug resistance by imposing barriers that limit drug delivery to the tumor. Thus, a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms, microenvironment, and barriers are needed to address the issues related to the limited efficacy of cancer chemotherapy. 1

Nano-sized agents have a number of theoretical advantages over conventional low molecular weight agents including a large loading capacity, the ability to protect the payload from degradation, specific targeting, and controlled or sustained release. 2-5 Their features can be enhanced by changing characteristics such as size, shape, payload, and surface features. 6, 7 Thus, the field of nanomedicine has been rapidly evolving, particularly for the diagnosis and treatment of cancer. 5, 8-11

However, nano-sized drugs are, by definition, larger than most drugs and therefore, leak more slowly from capillary beds. Fortunately, the vasculature of solid tumors is characterized by leaky vessels with poor lymphatic drainage. When administered intravenously, nano-sized agents tend to circulate for a long period of time if they are not small enough to be excreted by the kidney or large enough to be rapidly recognized and trapped by the reticuloendothelial system (RES). 12 Nano-sized agents with long circulation times leak preferentially into tumor tissue through the permeable tumor vasculature and are then retained in the tumor bed due to reduced lymphatic drainage. This phenomenon is known as ‘the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect’. 13, 14

The basis for nano-sized drug delivery is accumulation of the agent within tumors due to the EPR effect followed by release of their therapeutic payloads. However, EPR effects are relatively modest, offering less than a 2-fold increase in delivery compared with critical normal organs. 13 The longer the drug stays in circulation, the more likely it is to extravasate into the tumor through the EPR effect, but at the same time, the drug can also extravasate into normal tissues albeit at a slower rate. Thus, methods that even temporarily increase the local EPR effect within the tumor are needed to improve the specific uptake of the drug within the tumor, thereby improving its therapeutic effect.

In this review, we first overview the barriers to delivery, focusing on the capillary wall’s resistance of tumor. Then, we discuss the current regulatory environment facing nanomedicine in general. Finally, we discuss methods that enhance the EPR effect, thereby increasing the delivery of nano-sized drug to the tumor.

2. ENHANCED PERMEABILITY AND RETENTION EFFECT

Intravenously injected nano-sized drugs are delivered into pathological lesions through arterioles and released from capillaries. Therefore, the key mediators of intratumoral delivery are small vessels, especially capillaries. 15 Normal capillaries are lined by a tightly sealed endothelium, firmly attached and supported on the abluminal side by stellate-shaped pericytes, which are further enveloped in a thin layer of basement membrane (BM). 16 In normal tissues, pericyte coverage of the endothelial abluminal surface varies among different organs and blood vasculatures, with a general range between 10 and 70 %. 16, 17 The vasculature BM, with major components of type IV collagen, laminin, entactin (nidogen), fibronectin, usually envelops blood vessels with a thickness ranging from 100 to 150 nm. 18, 19

In order to grow, tumor cells recruit a neovasculature to ensure an adequate supply of nutrients and oxygen. As tumors grow, they recruit new vessels or engulf existing blood vessels. Unlike normal blood vessels, the tumor vasculature usually has incomplete endothelial lining causing relatively large pores (0.1-3 μm in diameter), leading to significantly higher vascular permeability and hydraulic conductivity. 20, 21 In addition, the extent of pericyte coverage on tumor vessels is typically diminished compared to normal tissues. 16 Both pericytes and BM are loosely associated with endothelial cells and occasionally penetrate deep in the tumor parenchyma, increasing the transendothelial permeability. 16, 22-25 Moreover, perivascular smooth muscle is often lacking in tumor vessels, making them poorly reactive to normal vasoregulation.26

Matsumura and Maeda were the first to show that nanoparticles are able to extravasate through the inherent leaky and loosely compacted vasculature to reach the tumor space and stay there due to the poor lymphatic drainage of tumors. 13 This phenomenon was later termed the EPR effect and paved the way for the passive targeting of tumors using nano-sized drugs. However, drug delivery due to EPR is still limited, as the rate of leakage from the vessels is slow and the drug can either be excreted or metabolized during the time it takes for the accumulation to reach therapeutic levels. 27 EPR effects are also modest, providing less than 2-fold increases in delivery compared with critical normal organs. This is generally insufficient for achieving therapeutic levels within the tumor, although, side effects are usually greatly reduced as a result of very low accumulation within normal tissues lacking EPR. 28

3. BARRIERS TO THE DELIVERY OF NANO-SIZED DRUGS

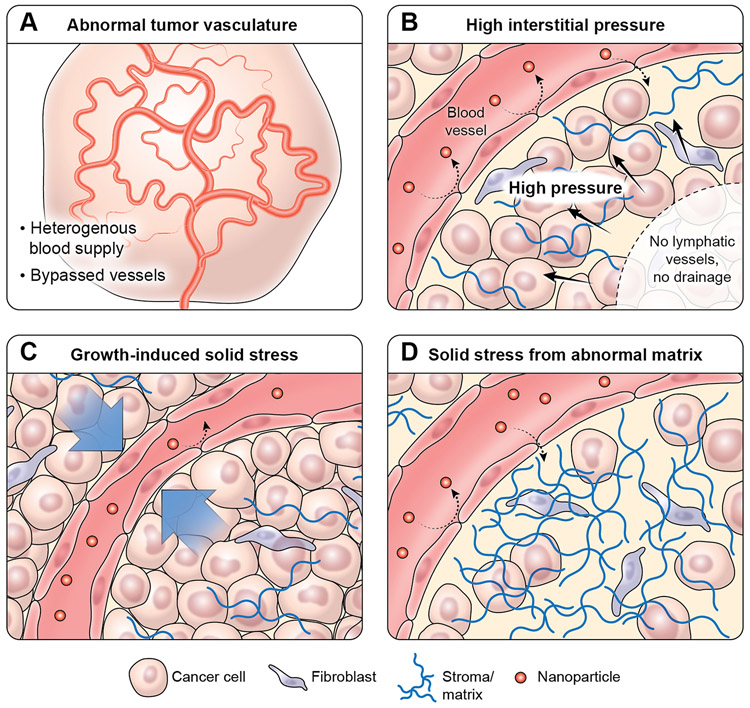

The EPR effect improves nano-sized drug accumulation in the extravascular space of tumors. In normal organs, circulating nano-sized drugs are cleared from the circulation by the mononuclear phagocyte system (MPS) or by glomerular filtration in the kidney. The capillary wall’s resistance to the transport of macromolecules and resistance through the interstitium limit nano-sized drug extravasation from blood vessels into the interstitial space. 25, 29 In spite of the EPR effect, overall permeability of the tumor endothelium is a limiting factor for the uptake of macromolecules like antibodies, and the tumor antibody concentration is always 100-1000 fold lower than the plasma concentration. Analogous to resistors in series in an electric circuit, the capillary wall’s resistance to the transport of macromolecules is significantly greater than subsequent resistance through the tumor interstitium. 30, 31 Here, we will focus on the capillary wall’s resistance, in other words, barriers for extravasation of nano-sized drug into tumors (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Barriers for the delivery of nano-sized drugs into tumors

3.1. Abnormal tumor vasculature

The tumor vascular network is characterized by dilated, tortuous, and saccular channels with haphazard patterns of interconnection and branching. 32-34 Unlike the microvasculature of normal tissue, which has an organized and regular branching order, tumor microvasculature is disorganized and lacks the conventional hierarchy of blood vessels. 35 Arterioles, capillaries, and venules are not identifiable as such and instead, vessels are enlarged and often interconnected by bidirectional shunts. 36 One physiological consequence of these vascular abnormalities is heterogeneity of tumor blood flow, 37 resulting in poor and heterogeneous perfusion in the tumor and elevated interstitial fluid pressure from constant extravasation of fluid, which, in turn, creates hypoxic and acidic intratumoral conditions. This environment prevents the penetration of nano-sized drugs deep within the tumor and therefore, contributes to tumor progression, metastasis and drug resistance. 21, 38-40

3.2. High interstitial fluid pressure

As tumor tissues have high osmotic pressure, high interstitial fluid pressure (IFP) may hinder adequate delivery of anti-cancer drugs. 41 IFP is elevated in solid tumors not only due to increased vessel permeability and hyperperfusion, but also due to poor lymphatic drainage which normally maintains fluid balance as well as hyperplasia around blood vessels and increased production of extracellular matrix components. 42 In normal tissues, IFP is approximately 0 mmHg; whereas in tumors, IFP can reach microvascular pressure levels (with a range of 10-40 mmHg). 43 High IFP limits the convection of nano-sized drugs, while paradoxically promoting passive diffusion out of the tumor. 43 Diffusion is a much slower transvascular process than convection, especially for the transport of large nano-sized drugs. 44 Moreover, stroma cells compress intratumoral blood and lymphatic vessels, further impairing blood flow, leading to blood stasis, loss of function, and further inhibition of nano-sized drug penetration. 45 Finally, because of the steep drop in IFP on the edge of tumors, intratumoral fluid can escape from the tumor periphery into the surrounding tissue, thus, spilling nano-sized drugs from their intended target, the tumor, into surrounding tissue. 44 Thus, high IFP poses a formidable barrier to both the delivery and efficacy of nano-sized drugs.

3.3. Growth-induced solid stress

Tumor growth is associated with the production of intratumoral mechanical forces, both fluid and solid, due to the unrestrained and rapid tumor cell proliferation in a limited area. Solid stress and mechanical forces are generated when cellular and non-cellular components of the tumor microenvironment interact with adjacent noncancerous cells and parts of their matrix. In certain tumor types with a less supportive stroma, solid stress-mediated vessel compression can occur due to proliferating tumor cells, hindering the distribution of blood-borne anti-cancer drugs into tumor tissue. 45, 46 Therefore, high tumor cell density is the foremost obstacle for penetration of nano-sized drugs deep into tumor tissues. 47 Solid stress caused either by cancer and stromal cell compression or deformation of vascular and lymphatic structures thereby contributes to tumor progression. Cell compression simultaneously results in changes in gene expression, cellular proliferation, apoptosis, invasion, and stromal cell-related extracellular matrix production and organization. 46, 48 Altogether, excessive growth-induced solid stress compresses tumor vessels and reduces perfusion. Tumor overgrowth may also create an interstitial barrier for efficient drug penetration into tumor tissues. Thus, alleviation of solid stress by targeting the tumor or stromal cells may provide an effective strategy for improving drug delivery. 49

3.4. Solid stress from abnormal stromal matrix

In normal tissues, the composition and structure of the extracellular matrix (ECM) is unique and dynamic and functions to regulate cell growth. The major ECM components are collagen, glycoprotein, proteoglycan, elastin, and hyaluronan. The ECM-associated structural components, enzymes and growth factors are crucial for the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation, ultimately prolonging cell survival and homeostasis. The ECM is localized at two different sites: the basement membrane and the interstitial space. For instance, the matrix of the basement membrane contains highly compact and less porous structures compared to that of tumors formed by collagen (type IV), fibronectin, laminins, and other related proteins that help to link collagen with other matrix proteins. Type I collagen, glycoproteins, and proteoglycans are abundant in the interstitial matrix and are collectively responsible for tensile strength of normal tissues. 50, 51

In contrast to these normal stromal features, tumor stroma is comprised of a modified ECM attached to multifaceted stromal cells including fibroblasts, pericytes, endothelial cells and immune cells. 52 Moreover, altered biophysical and biological characteristics of the tumor ECM in a hypoxic microenvironment contribute to tumor progression and metastases. 53 Fibrosis is a hallmark of many types of cancers; it develops due to excessive ECM production or limited ECM turnover in tumor tissues. 54 Severe desmoplastic or fibrotic reactions are characterized by deregulated accumulation of various types of collagen networks, 50 leading to extracellular matrix abnormalities that promote tumor progression through architectural and signaling interactions. 51

Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) play a major role in extracellular matrix-mediated malignant changes, which include upregulated extracellular matrix synthesis, posttranslational modifications, and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-induced extracellular matrix remodeling, leading to the reduction of drug uptake in tumors. 55, 56 Resting fibroblasts are transformed into CAFs in response to tumor-associated growth factors such as TGF-β, stroma-derived factor (SDF-1), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), and basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF). 49 Thus, the abnormal matrix found in tumors further interferes with nano-sized drug delivery to tumor.

4. CHALLENGES LIMITING CLINICAL TRANSLATION OF CANCER NANO-THERAPEUTICS

Despite the huge investments by government and industry and an astonishing number of scientific publications regarding “nanotechnology for cancer treatment” in the last 10 years, the translation of nano-sized drugs into clinical practice has been slow compared to that for small-molecule drugs. 57, 58 In fact, the majority of nanomaterials designed for clinical use are barely at the stage of in vivo evaluation, and even fewer have reached clinical trials. Existing knowledge gaps in science and technology are delaying the development of widely accepted modeling and predictive screening strategies, which would speed up the process between conception of innovative nanomedicine platforms and clinical approval. Challenges also lie in integrating the expert input required from a wide variety of disciplines. Nanomedicine requires a focused effort to integrate all of the relevant disciplines and go beyond the limits of discipline-specific knowledge and jargon. In addition, clear regulatory guidelines for the translation of nanotechnology-based therapies into clinically marketable products are lacking. 59 Practically, if nano-drugs rely on the EPR effect for delivery, their circulating half-life has to be sufficiently long for a sufficient amount of the nano-drug to enter the tumor. In general, acute and subacute toxicity must be evaluated for at least ten half-lives which, in the case of nano-drugs mandates a lot of time and cost. Therefore, nano-drugs carry with them greater regulatory costs than typical small molecular drugs.

Regulatory challenges

Currently in the United States, nanomaterials in pharmaceuticals are regulated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 60 The FDA is authorized to regulate new pharmaceuticals under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act. New drugs undergo an extensive premarket approval process, where authorities evaluate the drug’s benefits and risks on a case-by-case basis. 61 From a regulatory point of view, the lack of a clear and widely accepted definition of “nanomaterial”,62, 63 and thus “nanomedicine,” is another source of uncertainty. The FDA initially adopted a definition of nanotechnology in the 2007 National Nanotechnology Initiative (NNI) as involving all of the following elements: (1) the research and technology development at the atomic, molecular or macromolecular scale leading to the controlled creation and use of structures, devices and systems with a length scale of approximately 1-100 nm; (2) creating and using structures, devices, and systems, which have novel properties and functions as a result of their small and/or intermediate size; and (3) ability to control or manipulate these properties on an atomic scale. In 2011, the FDA issued a draft guidance for industry entitled “Considering Whether an FDA Regulated Product Involves the Application of Nanotechnology”,64 where it noted that the FDA chose not to adopt a regulatory definition of nanotechnology or related terms. In determining if an FDA-regulated product involves the use of nanotechnology, the FDA parameters are:

Whether the engineered material or end product has at least one dimension in the nanoscale range (approximately 1-100 nm); or

Whether the engineered material or end product exhibits properties or phenomena, including physical or chemical properties or biological effects, that are attributable to its dimensions, even if these dimensions fall outside the nanoscale range, up to 1 μm.

From the European perspective, the European Commission (EC) provided an official and more detailed definition of “nanomaterial” in the Recommendation 2011/696/EU. According to the EC recommendation:

Nanomaterial means a natural, incidental or manufactured material containing particles, in an unbound state or as an aggregate or as an agglomerate and where, for 50 % or more of the particles in the number size distribution, one or more external dimensions is in the size range 1-100 nm.

In specific cases and where warranted by concerns for the environment, health, safety, or competitiveness, the number size distribution threshold of 50 % may be replaced by a threshold between 1 and 50 %.

The EC recommends the above definition for all fields of application of nanotechnology, but a distinct regulatory definition is not provided as in the case of nanomedicine. It is clear that nanomedicines are often not within the 1-100 nm size range, unlike non-medical nanomaterials where quantum effects are paramount for their use (e.g., in electronic or optical devices). This size limitation is not usually relevant for drug delivery. In fact, the EPR effect typically operates in the range of 100-400 nm. 62 Thus, the EC acknowledged that an upper limit of 100 nm is not scientifically justified across the whole range of nanomaterial applications, and noted that “special circumstances prevail in the pharmaceutical sector” by stating that the recommendation should “not prejudice the use of the term ‘nano’ when defining certain pharmaceuticals and medical devices”. 65, 66

Ultimately, even though the US NNI and EC definitions of nanotechnology and nanomaterial are substantially different, the fundamental difficulty in providing a clear and unequivocal definition of a nanomedicine seems to be shared by both US and EU regulators. 59

Regulating clinical translation

According to the FDA, regulations can only be based on the current best information, the product has to be fundamentally safe and effective, independent of whether it employs a nanomaterial, and evaluation is based on case-by-case assessment. In 2007, the FDA stated that existing regulations were sufficiently comprehensive to ensure the safety of nanoproducts because these products would undergo premarket testing and approval either as new drugs under the New Drug Application (NDA) process, or in the case of medical devices, under the Class-3 Premarket Approval (PMA) process. 62, 67 This conclusion was based on the assumption that the regulatory requirements in place would detect toxicity during the required safety studies, even if nanoproducts presented unique properties related to their size. Many experts criticized this view because most FDA-approved nanoproducts obtain approval based in whole or in part on studies of non-nano versions of the drug, so they do not undergo the full PMA or NDA process. 62 In 2011, the FDA re-opened the dialogue on nanomedicine regulation by publishing proposed guidelines on how the agency will identify whether nanomaterials have been used in FDA-regulated products. 64 The FDA’s purpose here was to help medical product developers identify when there is a need to consider the regulatory status, safety, effectiveness, or health issues that could arise from the use of nanomaterials in FDA-regulated products. In 2012, the FDA commissioner summarized in general terms a “broadly inclusive initial approach” with respect to “nano-governance” in a two-page policy paper published in Science. This paper stated that the “FDA does not categorically judge all products containing nanomaterials or otherwise involving the application of nanotechnology as intrinsically benign or harmful. As with other emerging technologies, advances in both basic and applied nanotechnology science may be unpredictable, rapid, and unevenly distributed across product applications and risk management tools. Therefore, the optimal regulatory approach is iterative, adaptive, and flexible” .68 Most experts in the nanomedicine field continue to criticize the FDA’s effort to regulate nanotechnology, pointing to the fact the delay in addressing nano-specific regulation could have a very harmful effect on investors, public confidence, and commercialization efforts. 62

5. HOW TO IMPROVE THE EPR EFFECT?

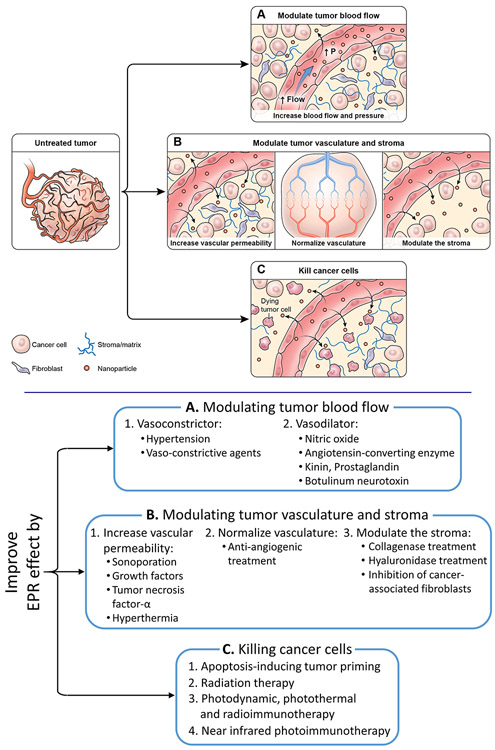

The extent of the EPR effect is dependent on several factors. 44, 69 By manipulating either local tumor or systemic conditions, EPR effects can increase, leading to increased nano-sized drug delivery. The three most important modifiable parameters that improve the tumor capillary wall’s resistance include (1) modulating the tumor blood flow; (2) modulating the tumor vasculature and stroma; (3) killing the cancer cells to reduce their barrier function (Figure 2). 31, 70

Figure 2.

Methods for improving cancer nano-sized drug delivery based on EPR effects by manipulating intrinsic physiological barriers.

5.1. Modulating tumor blood flow

One of the hallmarks of solid tumors is inefficient blood flow, which limits drug transport in the tumor and contributes to a reduced or absent transcapillary pressure gradient. Both effects reduce the uptake and distribution of antitumor drugs. In order to restore an efficient tumor blood flow, both vasoconstrictors and vasodilators have been used as promoter drugs that modulate tumor blood flow. This appears paradoxical, but both approaches aim to increase the transcapillary pressure gradient through different mechanisms such as increasing blood pressure with vasoconstrictors or decreasing flow resistance with vasodilators.

Vasoconstrictor

To improve perfusion in the tumor, the overall physiological condition of the patient can be altered. For example, Nagamitsu et al. induced systemic hypertension in patients with solid tumors using angiotensin II during infusion of nanoparticles. 71 They found that this strategy increased the accumulation of nanoparticles and resulted in improved therapeutic response, less toxicity, and a shorter time to achieve tumor regression. 72 While inducing hypertension has been shown to be a promising approach on a clinical basis, augmenting the EPR effect through a strategy that alters the physiological condition of the patient has challenges since it may affect the whole body. In the case of inducing hypertension, treatment is limited to patients not already on antihypertensive medication. In countries such as the US, where approximately a third of the population have hypertension, 73 some cancer patients may not be eligible for this treatment. Therefore, strategies augmenting the EPR effect that affect the whole body will have to take the demographics of the population into consideration. 39

Normal vessels retain their ability to respond to extrinsic vasoconstrictors whereas tumor vessels lose their responsiveness to such agents. When vasoconstrictive drugs are administered, normal vessels become constricted due to contraction of muscular fibers in the vessel wall, limiting blood flow and increasing blood pressure. In contrast, tumor vessels do not respond to vasoconstrictors because of insufficient muscular structure. This leads to a relative increase in the blood flow in vessels supplying tumors. 74 This phenomenon was recognized in the 1970s during diagnostic angiography for tumor localization and was termed “pharmaco-angiography”. 75 During diagnostic angiography, vaso-constricting agents, including alpha receptor agonists, were injected via a catheter to constrict normal vessels while accentuating tumor vessels. 76, 77 Later, pharmaco-angiography was used to constrict vessels after the delivery of a nanodrug therapy to reduce washout and increase exposure of the tumor to the therapy. 78 Diagnostic pharmaco-angiography is no longer needed for conventional diagnostic scanning because CT and MRI scans have become proficient at detecting cancers, but the effect can still be put to use to selectively increase drug delivery. 70

Vasodilator

To enhance the EPR effect, a number of vascular mediators are utilized. 14 Nitric oxide (NO) is an endogenous mediator that causes vessels to dilate and thereby lowers blood pressure. Many solid tumors manifest vascular embolism or vascular clogging. If nitroglycerin is administered to restore the vascular blood flow of such tumors, drug delivery is increased and hence a greater EPR effect occurs. Seki and others published investigations of the application of nitroglycerin and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, such as enalapril, in which they reported increased delivery of Evans blue-albumin to tumors. 79-84 Fang et al. also showed that carbon monoxide-releasing micelles enhanced drug delivery. 85, 86 Yasuda et al. reported significant benefits of using an NO-releasing agent (nitroglycerin) using conventional low molecular weight anticancer agents in clinical settings. 87, 88

Another vascular mediator involved in the EPR effect, Kinin, is a major mediator of inflammation that induces extravasation and accumulation of body fluids in inflammatory tissues (edema). 89, 90 Kinin is known to activate endothelial cell-derived NO synthase, 91 which ultimately leads to an increase in NO, an important mediator of tumor vascular permeability.

Prostaglandins (PGs) are lipid compounds that are derived enzymatically from arachidonic acid by means of cyclooxygenases (COXs). 92, 93 Similar to bradykinin, PGs are important mediators in inflammation and can be upregulated by inflammatory cytokines as well as kinin. 94, 95 Among the various PGs, PGE1 and PGI2 exhibit effects similar to those of NO, i.e., preventing platelet aggregation, leukocyte adhesion, and thrombosis formation and facilitating extravasation and the EPR effect. Injection of a stable analogue of PGI2, beraprost sodium (Dorner), which has a long plasma half-life in humans, resulted in increased extravasation of the Evans blue/albumin complex from 2- to 3-fold. 96

Ansiaux et al. have shown that local administration of Botulinum neurotoxin type A increases tumor oxygenation and perfusion, leading to improvement in the tumor response to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. This is the result of interference with neurotransimitter release at the perivascular sympathetic varicositities, leading to the inhibition of the neurogenic contractions of tumor vessels and improvement of tumor perfusion and oxygenation. 97

5.2. Modulating the tumor vasculature and stroma

Use of promoter drugs or methods that induce selective enhancement of the permeability of the tumor endothelial barrier is another strategy to improve uptake and distribution of drugs. In fact, despite areas of leakiness and increased permeability, the endothelial barrier represents a major limiting factor for drug delivery. It may appear paradoxical that two maneuvers that lead to opposite effects, i.e. reduction of the vascular permeability through normalization of tumor blood vessels, and enhancement of the permeability of tumor blood vessels, allow for increased uptake and penetration of drugs. The crucial point, however, for drugs that modulate tumor blood flow, is that both maneuvers temporarily lead to an increased transcapillary pressure gradient, which results in enhanced tumor uptake of drugs. 31

Since the ECM is an additional key determinant of solid stress, it also hinders interstitial drug distribution within tumor tissue. A tumor priming strategy to alleviate stroma-mediated solid stress by targeting the ECM (directly by degradation or indirectly by inhibiting its synthesis) may be useful to improve chemotherapeutic efficacy.

5.2.1. Enhancement of the permeability of tumor blood vessels

Sonoporation

Sonoporation combines ultrasound (US) and microbubbles (MB) to induce stable and inertial cavitation effects, which permealizes cell membranes and opens tight junctions in vascular endothelium. Sonoporation has been reported to enhance the ability of nano-sized drugs to extravasate out of blood vessels into the tumor interstitium, suggesting that sonoporation may be a useful strategy for improving EPR-mediated drug targeting to tumors. 98, 99 However, while it might be tempting to damage endothelial cells in an attempt to increase permeability, this can only be achieved at the risk of decreasing or even eliminating blood flow to the tumor due to thrombosis. Moreover, sonoporation is untargeted, so both tumor and surrounding normal tissue may be damaged by the drug.

Growth factors

Initially, tumors are dependent on the vasculature of the surrounding host tissues for their blood supply. However, as they grow further, they switch into an angiogenic state in order to meet their increasing metabolic demands. 100 Tumors also show increased levels of growth factors like vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) among others. 101, 102 These growth factors significantly increase permeability of macromolecules by modulating the sub-endothelial structures. 103 However, the vascular permeability of tumors is also very heterogeneous in its distribution due to this abnormal angiogenesis, which can negate the effects of EPR. Application of exogenous VEGF was found to increase the pore size of human colon carcinoma xenografts, allowing for the enhanced extravasation of albumin (7 nm) as well as PEGylated liposomes (100-400 nm). 104 There is also some reluctance to use growth factors such as VEGF as they might have an unpredictable effect on tumor growth, to the extent that receptors are found not only on endothelial cells but also on tumor cells.

Tumor necrosis factor-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α(TNF) is an inflammatory cytokine that causes hemorrhagic tumor necrosis in mice. 105 Studies showed high response rates where high-dose TNF in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs was administered by isolated-limb perfusion to patients with melanoma or sarcoma of the extremities. 106-109 Clear evidence was obtained in these studies for TNF as a promoter drug that increases tumor uptake and penetration of chemotherapeutic effector drugs. However, in humans the drug is very toxic and functions only in a narrow range of doses before causing severe systemic side effects.

Hyperthermia

Kong et al. reported that with hyperthermia, a 100-nm liposome experienced the largest relative increase in extravasation from tumor vasculature; moreover, hyperthermia did not enable extravasation of 100 nm liposomes from normal vasculature, potentially allowing for tumor-specific delivery. 110 Li et al. have shown that local hyperthermia was able to increase the vascular permeability up to particle diameters of 10 μm in a variety of tumor models. 111 This allowed for increased liposomal extravasation not seen with normothermia. Similarly, Liu et al. were able to demonstrate that the thermally induced extravasation of liposomes led to their increased accumulation in murine mammary carcinomas. 112 Tumor-specific hyperthermia induced by high intensity focused ultrasound has also been reported to improve drug delivery to tumors. 113-117 Once again, it is difficult to contain hyperthermia just to the tumor and therefore, this method can increase drug delivery to normal tissue at the periphery of the tumor causing off-target side effects.

5.2.2. Reduction of the vascular permeability

Vascular normalization

Abnormalities in tumor vasculature and lymphatic system create an unfavorable tumor microenvironment for molecular movement, which ultimately prevents adequate and homogenous distribution of anticancer drugs (either small molecules or macromolecules, including nano-sized drugs and antibodies) in solid tumors. 118,119 Vascular normalization repairs not only abnormal structures, but also the functions of tumor vasculature by correcting rapid angiogenic signaling. Anti-angiogenic treatment reestablishes the balance between pro- and anti-angiogenic agents, and the blood vessels become more stable and uniform in structure and function. 120 Hence, remarkable improvements have been demonstrated in the delivery as well as efficacy of anticancer therapeutics. 121, 122 However, normalized vessels also tend to reduce the size of fenestrations which will hinder EPR-based delivery of large nano-sized drugs to tumor tissue. Therefore, vascular normalization tends to improve tumor penetration only in the case of smaller nano-sized drugs (< 60 nm). Moreover, this improvement in the delivery of drugs has also been reported to be short-lived so that accurate timing between normalization and administration of the nano-drug is mandatory. 123

Decrement of interstitial fluid pressure

High IFP in tumors is a direct consequence of angiogenesis and limits nano-sized drug extravasation. Targeting angiogenesis is a simple approach to circumvent this barrier. 124, 125 Paclitaxel treatment has been shown to be effective in reducing IFP values in the clinic. 126 A VEGF blockade to inhibit angiogenesis is another promising strategy to aid in drug penetration against the pressure gradient. 127 Treatment with Imatinib, a PDGF receptor-β inhibitor, led to decreased VEGF expression and subsequently decreased IFP. 128 Similarly, Dickson et al. have shown that pretreatment with Bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF monoclonal antibody, helped to improve the anti-tumor efficacy of systemically administered topotecan in a murine neuroblastoma model. 129 Vascular disrupting agents such as combretastatin and ZD6126, a tubulin-binding agent, have also been used to successfully reduce IFP. 130, 131

5.2.3. Modulating the stroma

Direct extracellular matrix degradation

Abnormal ECM composition and structure in solid tumors are the major obstacles for penetration of anticancer drugs, especially in desmoplastic tumors. In solid tumors, penetration of macromolecular therapeutic agents is particularly affected by interstitial stromal barriers such as collagen networks. 132 Numerous studies have shown that the ECM-degrading enzyme collagenase can improve the distribution of macromolecules in solid tumors. 133, 134 The hormone relaxin has been reported to also be effective in increasing drug delivery by modifying collagen structure. 44 The collagen content in tumors showed correlation with the IgG diffusion coefficient measured in situ with fluorescence, and IgG penetration into tumor interstitial tissue increased after collagenase treatment. 135 Similar to collagen, hyaluronan, also called hyaluronic acid (HA), is a key matrix element that increases IFP and vascular collapse. Hyaluronidase has been reported to induce HA degradation, thus improving vascular perfusion and facilitating efficient penetration of chemotherapeutic agents. 42, 136 However, this only will be effective where it is injected and to that extent is non-targeted.

Reduction of extracellular matrix synthesis by inhibition of CAFs

CAFs are key regulator of tumorigenesis. In contrast, in tumor cells, which are genetically unstable and mutate frequently, the presence of genetically stable fibroblasts in the tumor-stromal compartment makes them an optimal target for cancer immunotherapy. Loeffler et al. proposed the use of an oral DNA vaccine targeting fibroblast activation protein (FAP), which is specifically overexpressed by fibroblasts in the tumor stroma. Through CD8+ T cell-mediated killing of CAFs, this vaccine successfully suppressed primary tumor cell growth and metastasis of multidrug-resistant murine colon and breast carcinoma. Furthermore, tumor tissue of FAP-vaccinated mice revealed markedly decreased collagen type I expression and up to 70 % greater uptake of chemotherapeutic drugs. 56

In addition to killing CAF cells, ECM deregulation can be inhibited by blocking the growth factors involved in CAF stimulation. Hence, inhibiting collagen synthesis has been accomplished either by using anti-TGF-β antibodies or agents that have anti-fibrotic activity by causing TGF-β signaling blockade, and resulted in an enhanced delivery of therapeutic agents. 137 Losartan, a well-known antihypertensive agent with antifibrotic effects, has also been reported to be effective in reducing the tumor tissue collagen content and successfully used to enhance diffusive transport and efficacy of intravenously administered nanoparticles. 138, 139 Pentoxifylline, which has antifibrotic activity, also induced significant changes in the collagen content in a human pancreatic tumor xenograft, resulting in improved distribution of doxorubicin and its liposomal formulation. 49 These approaches are especially appealing as they target the tumor microenvironment, and, in theory, do not affect normal capillary beds.

5.3. Killing the cancer cells to reduce their barrier function

Nanodrug delivery reportedly increases after many cancer therapies. The likely explanation for this is that tumor cells themselves act as a barrier to deeper penetration of nanodrugs. The heterogeneity of the blood supply within the tumor microenvironment leads to marked heterogeneity in the rate of cell proliferation; cancer cells near the vessels proliferate rapidly, while cancer cells further away from the vessels suffer nutrient deprivation and proliferate more slowly. 140, 141 Microscopy reveals that tumor cells grow as sleeves or sheaths concentric with tumor vessels. 142 Such highly cellular layers may interfere with drug penetration to the inner layers of the tumor. 143

Apoptosis-inducing tumor priming for solid stress alleviation

Successful decompression of tumor blood vessels was first reported by Jain who used taxanes (paclitaxel and docetaxel) to induce apoptosis in murine mammary carcinoma and human soft tissue sarcoma. Taxane induced apoptosis, thus alleviated solid stress by decreasing the cancer cell mass, and also restored the vessel diameter, which consequently lowered microvascular pressure and IFP. 144 A solid stress alleviation strategy using apoptosis induction has also been proposed by Au’s group. They considered high tumor cell density as a penetration barrier and reported that changes in cell density induced by paclitaxel improved drug penetration in a schedule-dependent manner in solid tumor histoculture models. 74 The term ‘tumor priming’ was coined by Au’s group when they first used it to describe paclitaxel-induced reduction of tumor cell density and expansion of the interstitial space, which promoted distribution of doxorubicin-HCl liposomes into the inner layers of the tumor in xenograft models. 47

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy has also been reported to increase perfusion and permeability of nanoparticles. 145 Radiation therapy primarily damages cancer cells with a much less pronounced effect on the vasculature. Nano-sized molecules can enter radiation treated tumors at a rate 2.2-fold higher than unirradiated tissue. 146 Radiation killed well-oxygenated cancer cells near tumor vessels, therefore, radiation temporarily increased vascular permeability by reducing the barrier function of the cancer cells. The greatest cell damage occurred in perivascular cancer cells, which subsequently underwent apoptosis. However, excessive radiation damaged the vessels sufficiently to shut down blood flow, which negatively affected nano-drug delivery. 70

Photodynamic, photothermal and radioimmunotherapy therapy

Light therapy with conventional photodynamic therapy (PDT) can also enhance the EPR effect up to 3-fold compared with control tumors, although this effect is limited to within 0 and 12 h after PDT. 147-149 However, similar to radiation therapy, because PDT causes damage to both tumor vasculature and the tumor vascularity, there is a danger that PDT can also reduce vascularity, thus negatively affecting drug delivery. 150, 151 In recent work, the cancer cells were targeted via the GRP78 receptor using a GRP78-targeting peptide conjugated to a PEGylated gold nano-rod. When light was applied, photo-thermal damage led to tumor cell killing that increased EPR effects up to approximately 2-fold compared with untreated controls. 152 Furthermore, systemic radioimmunoconjugates preferably killed perivascular tumor cells resulting in improved drug delivery. 153, 154 However, these methods could also damage tumor vasculatures resulting in thrombotic occlusion from the bystander effect.

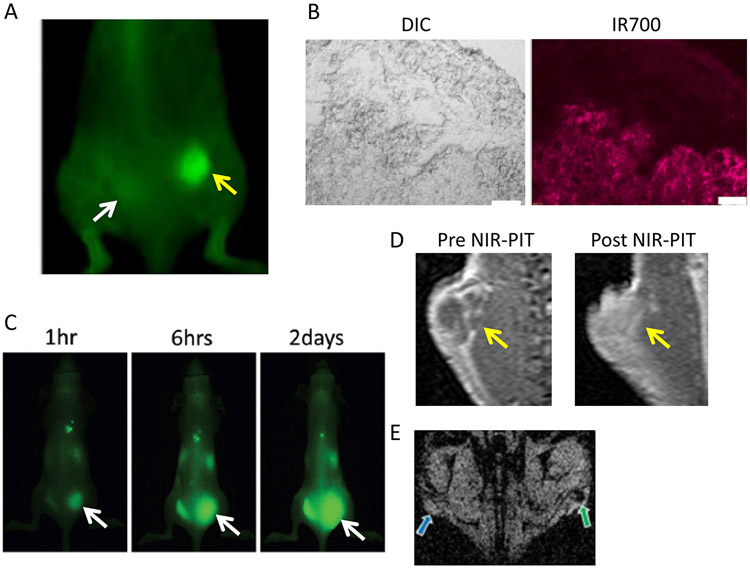

Near infrared photoimmunotherapy

Near infrared photoimmunotherapy (NIR-PIT) is a newly developed cancer treatment that employs a targeted monoclonal antibody conjugated to a photon absorber, IRDye700DX (IR700, silica-phthalocyanine dye). 155 The first-in-human phase 1 trial of NIR-PIT in patients with inoperable head and neck cancer targeting epidermal growth factor receptor was approved by the US FDA, and is underway as of June 2015 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT02422979). In this trial, a patient is injected with an antibody-photoabsorber conjugate (APC) that binds to target molecules on tumor’s cell membrane. About 24 hours later, the tumor is exposed to NIR light at a wavelength of 690 nm, which is absorbed by the dye. This induces nearly immediate necrotic cell death rather than apoptotic cell death. Within minutes, cells treated with NIR-PIT rapidly increase in volume, leading to rupture of the cell membrane and extrusion of cell contents into the extracellular space. 156-159 In contrast, cell death by apoptosis tends to shrink tumor size without membrane disruption and requires a period of several days. 160-162 Moreover, because the APC tends to preferentially bind to the layers of cells in the immediate perivascular space, subsequent NIR-PIT treatment leads to further perivascular tumor cell death, thereby promoting increases in vascular permeability and permitting even nano-sized particles to enter the treated tumor beds. The dramatic increase in permeability for nanoparticles, followed by their retention in NIR-PIT treated tumors, has been termed ‘super-enhanced permeability and retention (SUPR)’ (Figure 3). SUPR effects induced by NIR-PIT have been reported to allow an increase in nano-drug delivery up to 24-fold compared with untreated tumors in which only the EPR effect is present. 163, 164 Unlike radiation therapy and PDT, NIR-PIT can only induce SUPR effects because of the specific killing of cancer cells adjacent to tumor vasculatures that removes the “solid stress” without decreasing the blood flow in tumors. It was also reported that cell killing after NIR-PIT was primarily on the surface, however, APCs administered immediately after NIR-PIT penetrated deeper into tissue compared to the 1st NIR-PIT session, resulting in improved cell killing after a 2nd NIR-PIT session. 165 Moreover, these changes occur within 20 minutes of NIR light exposure, yet gross tumor size and shape do not change for several days after NIR-PIT. 163, 166 However, the effects are also short lived, lasting a period of hours after NIR-PIT, sufficient to administer nano-sized drugs in combination. Thus, NIR-PIT could have a direct impact on the therapeutic effects of nanosized cancer drugs.

Figure 3.

A. 800 nm fluorescence image. NIR-PIT induced SUPR effects delivered PEGylated quantum dots (800 nm emission; 50 nm in diameter) into a NIR-PIT treated tumor at a 24-fold higher concentration than in nontreated tumor with conventional EPR effects at 1 hour after injection. Yellow arrow indicates the NIR-PIT treated tumor and the white arrow indicates the nontreated tumor. B. DIC (left) and IR700 fluorescence microscopic image (right) of N87 tumor. IR700 injected after NIR-PIT accumulated in the deeper area of NIR-PIT treated tumor. C. Super enhanced delivery of antibody-drug conjugate (ADC, trastuzumab-CA4) into NIR-PIT treated tumor (arrow indicates NIR-PIT treated tumor). ADC accumulated in NIR-PIT treated tumor only 1 hour after injection and accumulation area increased gradually, indicating the retention of ADC due to the SUPR effect. D. SUPR delivery of gadofosveset, a protein-binding MRI contrast agent. Gadofosveset greatly and homogeneously enhances only post NIR-PIT treated tumor 30 in after injection. Arrow indicates tumor. E. Intratumoral leakage of large nanoparticles (~200 nm) following NIR-PIT. NIR-PIT treated tumor showed low signal intensity on T2* weighted MR images after administration of super paramagnetic iron oxide (SPIO; mean diameter ~200 nm), indicating the selective uptake of SPIO (green arrow). Blue arrow indicates non-treated tumor.

6. CONCLUSIONS

Nano-sized cancer drugs are highly promising because of their unique chemical and biological characteristics. For instance, they can be highly loaded with anti-cancer agents which release their payload within the tumor. To date, specificity has been conferred by the EPR effect which increases extravasation and retention within the tumor bed. However, the EPR effect provides relatively modest specificity and less than 2-fold increases in nano-drug delivery compared with normal organs. Several promising methods to enhance the EPR effect by overcoming various barriers of nano-drug delivery into tumors have been reported. These include efforts to regulate vessels, regulate permeability, physically disrupt vessels and act on the tumor microenvironment through controlling cancer associated fibroblasts. While many of these are promising, the magnitude of these effects is typically 2-fold (200%) times the baseline of the EPR effect. In contrast, super-enhanced EPR (SUPR) effects which occur after NIR-PIT induce damage in the layers of cancer cells immediately adjacent to the tumor vasculature without damage to the tumor vasculature itself. SUPR can have dramatic effects on perfusion, with improvements in the delivery of nanoparticles up to 24-fold (2400%) compared with untreated tumors. Moreover, these changes occur within 20 minutes of NIR light exposure, therefore, the SUPR effect does not require that nano-sized drugs have long circulation times associated with higher toxicity and regulatory barriers. Thus, the SUPR effect induced by NIR-PIT should be a powerful tool for nano-drug delivery to the tumor.

The clinical translation of nanomedicine has given rise to regulatory questions that are unique to this new class of drugs. In that respect, nano-sized drugs may require regulators to adopt different criteria for approval. This is not a problem limited to one country or one regulatory system. The international nanomedicine stakeholder community and its professional networks must integrate scientifically, technologically, and legislatively to develop sensible guidelines for developers to understand. The overall goal is to bring the global health benefits of nanomedicine closer than ever. 59

ACKNOLEDGEMENTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Tannock IF, Lee CM, Tunggal JK, Cowan DS, and Egorin MJ (2002) Limited penetration of anticancer drugs through tumor tissue: a potential cause of resistance of solid tumors to chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 8, 878–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Ng KK, Lovell JF, and Zheng G (2011) Lipoprotein-inspired nanoparticles for cancer theranostics. Accounts of chemical research 44, 1105–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Patel S, Bhirde AA, Rusling JF, Chen X, Gutkind JS, and Patel V (2011) Nano delivers big: designing molecular missiles for cancer therapeutics. Pharmaceutics 3, 34–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Perche F, and Torchilin VP (2013) Recent trends in multifunctional liposomal nanocarriers for enhanced tumor targeting. Journal of drug delivery 2013, 705265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Stylianopoulos T, and Jain RK (2015) Design considerations for nanotherapeutics in oncology. Nanomedicine : nanotechnology, biology, and medicine 11, 1893–907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Longmire M, Choyke PL, and Kobayashi H (2008) Clearance properties of nano-sized particles and molecules as imaging agents: considerations and caveats. Nanomedicine (Lond) 3, 703–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Longmire MR, Ogawa M, Choyke PL, and Kobayashi H (2011) Biologically optimized nanosized molecules and particles: more than just size. Bioconjugate chemistry 22, 993–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Rose PG (2005) Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin: optimizing the dosing schedule in ovarian cancer. Oncologist 10, 205–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).McNerny DQ, Leroueil PR, and Baker JR (2010) Understanding specific and nonspecific toxicities: a requirement for the development of dendrimer-based pharmaceuticals. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. Nanomedicine and nanobiotechnology 2, 249–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Matsumura Y, and Kataoka K (2009) Preclinical and clinical studies of anticancer agent-incorporating polymer micelles. Cancer Sci 100, 572–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Kobayashi H, and Brechbiel MW (2003) Dendrimer-based macromolecular MRI contrast agents: characteristics and application. Molecular imaging 2, 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Kobayashi H, and Brechbiel MW (2005) Nano-sized MRI contrast agents with dendrimer cores. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 57, 2271–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Matsumura Y, and Maeda H (1986) A new concept for macromolecular therapeutics in cancer chemotherapy: mechanism of tumoritropic accumulation of proteins and the antitumor agent smancs. Cancer Res 46, 6387–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Maeda H, Tsukigawa K, and Fang J (2016) A Retrospective 30 Years After Discovery of the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect of Solid Tumors: Next-Generation Chemotherapeutics and Photodynamic Therapy-Problems, Solutions, and Prospects. Microcirculation 23, 173–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Nishihara H (2014) Human pathological basis of blood vessels and stromal tissue for nanotechnology. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 74, 19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Armulik A, Genove G, and Betsholtz C (2011) Pericytes: developmental, physiological, and pathological perspectives, problems, and promises. Developmental cell 21, 193–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Sims DE (1986) The pericyte--a review. Tissue & cell 18, 153–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Yokoi K, Kojic M, Milosevic M, Tanei T, Ferrari M, and Ziemys A (2014) Capillary-wall collagen as a biophysical marker of nanotherapeutic permeability into the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res 74, 4239–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Inoue S (1989) Ultrastructure of basement membranes. International review of cytology 117, 57–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Danquah MK, Zhang XA, and Mahato RI (2011) Extravasation of polymeric nanomedicines across tumor vasculature. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 63, 623–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).McDonald DM, Thurston G, and Baluk P (1999) Endothelial gaps as sites for plasma leakage in inflammation. Microcirculation 6, 7–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Yurchenco PD, and Ruben GC (1987) Basement membrane structure in situ: evidence for lateral associations in the type IV collagen network. The Journal of cell biology 105, 2559–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Kanapathipillai M, Brock A, and Ingber DE (2014) Nanoparticle targeting of anti-cancer drugs that alter intracellular signaling or influence the tumor microenvironment. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 79–80, 107–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Baluk P, Morikawa S, Haskell A, Mancuso M, and McDonald DM (2003) Abnormalities of basement membrane on blood vessels and endothelial sprouts in tumors. Am J Pathol 163, 1801–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Miao L, and Huang L (2015) Exploring the tumor microenvironment with nanoparticles. Cancer treatment and research 166, 193–226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Chan RC, Babbs CF, Vetter RJ, and Lamar CH (1984) Abnormal response of tumor vasculature to vasoactive drugs. J Natl Cancer Inst 72, 145–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Prabhakar U, Maeda H, Jain RK, Sevick-Muraca EM, Zamboni W, Farokhzad OC, Barry ST, Gabizon A, Grodzinski P, and Blakey DC (2013) Challenges and key considerations of the enhanced permeability and retention effect for nanomedicine drug delivery in oncology. Cancer Res 73, 2412–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).O'Brien ME, Wigler N, Inbar M, Rosso R, Grischke E, Santoro A, Catane R, Kieback DG, Tomczak P, Ackland SP, et al. (2004) Reduced cardiotoxicity and comparable efficacy in a phase III trial of pegylated liposomal doxorubicin HCl (CAELYX/Doxil) versus conventional doxorubicin for first-line treatment of metastatic breast cancer. Ann Oncol 15, 440–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Rabanel JM, Aoun V, Elkin I, Mokhtar M, and Hildgen P (2012) Drug-loaded nanocarriers: passive targeting and crossing of biological barriers. Curr Med Chem 19, 3070–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Thurber GM, Schmidt MM, and Wittrup KD (2008) Antibody tumor penetration: transport opposed by systemic and antigen-mediated clearance. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60, 1421–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Marcucci F, and Corti A (2012) How to improve exposure of tumor cells to drugs: promoter drugs increase tumor uptake and penetration of effector drugs. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 64, 53–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Fukumura D, Duda DG, Munn LL, and Jain RK (2010) Tumor microvasculature and microenvironment: novel insights through intravital imaging in pre-clinical models. Microcirculation 17, 206–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Ziyad S, and Iruela-Arispe ML (2011) Molecular mechanisms of tumor angiogenesis. Genes & cancer 2, 1085–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Papetti M, and Herman IM (2002) Mechanisms of normal and tumor-derived angiogenesis. American journal of physiology. Cell physiology 282, C947–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Konerding MA, Miodonski AJ, and Lametschwandtner A (1995) Microvascular corrosion casting in the study of tumor vascularity: a review. Scanning microscopy 9, 1233–43; discussion 1243-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Jain RK (2003) Molecular regulation of vessel maturation. Nature medicine 9, 685–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Jain RK (1988) Determinants of tumor blood flow: a review. Cancer Res 48, 2641–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Carmeliet P, and Jain RK (2000) Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature 407, 249–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Huynh E, and Zheng G (2015) Cancer nanomedicine: addressing the dark side of the enhanced permeability and retention effect. Nanomedicine (Lond) 10, 1993–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Jain RK (2005) Normalization of tumor vasculature: an emerging concept in antiangiogenic therapy. Science 307, 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Jain RK (1987) Transport of molecules in the tumor interstitium: a review. Cancer Res 47, 3039–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Jacobetz MA, Chan DS, Neesse A, Bapiro TE, Cook N, Frese KK, Feig C, Nakagawa T, Caldwell ME, Zecchini HI, et al. (2013) Hyaluronan impairs vascular function and drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut 62, 112–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Boucher Y, and Jain RK (1992) Microvascular pressure is the principal driving force for interstitial hypertension in solid tumors: implications for vascular collapse. Cancer Res 52, 5110–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Jain RK, and Stylianopoulos T (2010) Delivering nanomedicine to solid tumors. Nature reviews. Clinical oncology 7, 653–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Padera TP, Stoll BR, Tooredman JB, Capen D, di Tomaso E, and Jain RK (2004) Pathology: cancer cells compress intratumour vessels. Nature 427, 695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Stylianopoulos T, Martin JD, Chauhan VP, Jain SR, Diop-Frimpong B, Bardeesy N, Smith BL, Ferrone CR, Hornicek FJ, Boucher Y, et al. (2012) Causes, consequences, and remedies for growth-induced solid stress in murine and human tumors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109, 15101–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Lu D, Wientjes MG, Lu Z, and Au JL (2007) Tumor priming enhances delivery and efficacy of nanomedicines. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 322, 80–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Jain RK, Martin JD, and Stylianopoulos T (2014) The role of mechanical forces in tumor growth and therapy. Annual review of biomedical engineering 16, 321–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Khawar IA, Kim JH, and Kuh HJ (2015) Improving drug delivery to solid tumors: priming the tumor microenvironment. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 201, 78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Egeblad M, Rasch MG, and Weaver VM (2010) Dynamic interplay between the collagen scaffold and tumor evolution. Current opinion in cell biology 22, 697–706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Lu P, Weaver VM, and Werb Z (2012) The extracellular matrix: a dynamic niche in cancer progression. The Journal of cell biology 196, 395–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Maquart FX, Bellon G, Pasco S, and Monboisse JC (2005) Matrikines in the regulation of extracellular matrix degradation. Biochimie 87, 353–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Gilkes DM, Semenza GL, and Wirtz D (2014) Hypoxia and the extracellular matrix: drivers of tumour metastasis. Nature reviews. Cancer 14, 430–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Frantz C, Stewart KM, and Weaver VM (2010) The extracellular matrix at a glance. Journal of cell science 123, 4195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Egeblad M, Nakasone ES, and Werb Z (2010) Tumors as organs: complex tissues that interface with the entire organism. Developmental cell 18, 884–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Loeffler M, Kruger JA, Niethammer AG, and Reisfeld RA (2006) Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Invest 116, 1955–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Venditto VJ, and Szoka FC Jr. (2013) Cancer nanomedicines: so many papers and so few drugs! Adv Drug Deliv Rev 65, 80–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Valencia PM, Farokhzad OC, Karnik R, and Langer R (2012) Microfluidic technologies for accelerating the clinical translation of nanoparticles. Nature nanotechnology 7, 623–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Bregoli L, Movia D, Gavigan-Imedio JD, Lysaght J, Reynolds J, and Prina-Mello A (2016) Nanomedicine applied to translational oncology: A future perspective on cancer treatment. Nanomedicine : nanotechnology, biology, and medicine 12, 81–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Vance ME, Kuiken T, Vejerano EP, McGinnis SP, Hochella MF Jr., Rejeski D, and Hull MS (2015) Nanotechnology in the real world: Redeveloping the nanomaterial consumer products inventory. Beilstein journal of nanotechnology 6, 1769–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Wacker MG, Proykova A, and Santos GM (2016) Dealing with nanosafety around the globe-Regulation vs. innovation. International journal of pharmaceutics 509, 95–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (62).Bawa R (2013) Bio-Nanotechnology: A Revlution in Food, Biomedical and Health Science, 2012/October/09 ed., Wiley-Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- (63).Tinkle S, McNeil SE, Muhlebach S, Bawa R, Borchard G, Barenholz YC, Tamarkin L, and Desai N (2014) Nanomedicines: addressing the scientific and regulatory gap. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1313, 35–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Draft Guidance for Industry. (2011) Considering whether and FDA regulated product involves the application of nanotechnology 2011 Available from: http://www.fda.gov/RegulatoryInformation/Guidances/ucm257698.htm. [Google Scholar]

- (65).Commision Recmmendation of 18 October 2011 on the definition of nanomaterial. nanomaterial. (2014) Available from: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2011:275:0038:0040:EN:PDF.

- (66).Scientific Committee on Emerging and Newly Identified Health Risks. Scientific basis for the definition of the term “nanomaterial”. (2010) Available from: http://ec.europa.eu/health/scientific_committees/emerging/docs/scenihr_o_030.pdf.

- (67).U.S. Food and Drug Administration. (2007) Nanotechnology: a report of the US Food and Drug Administration, Nanotechnology Task Force. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/Nanotechnology/ucm2006659.htm.

- (68).Hamburg MA (2012) Science and regulation. FDA's approach to regulation of products of nanotechnology. Science 336, 299–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (69).Lammers T, Kiessling F, Hennink WE, and Storm G (2012) Drug targeting to tumors: principles, pitfalls and (pre-) clinical progress. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 161, 175–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (70).Kobayashi H, Turkbey B, Watanabe R, and Choyke PL (2014) Cancer drug delivery: considerations in the rational design of nanosized bioconjugates. Bioconjugate chemistry 25, 2093–100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (71).Suzuki M, Hori K, Abe I, Saito S, and Sato H (1981) A new approach to cancer chemotherapy: selective enhancement of tumor blood flow with angiotensin II. J Natl Cancer Inst 67, 663–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (72).Nagamitsu A, Greish K, and Maeda H (2009) Elevating blood pressure as a strategy to increase tumor-targeted delivery of macromolecular drug SMANCS: cases of advanced solid tumors. Jpn J Clin Oncol 39, 756–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (73).Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, Arnett DK, Blaha MJ, Cushman M, Das SR, de Ferranti S, Despres JP, Fullerton HJ, et al. (2016) Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2016 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation 133, e38–e360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (74).Jang SH, Wientjes MG, and Au JL (2001) Enhancement of paclitaxel delivery to solid tumors by apoptosis-inducing pretreatment: effect of treatment schedule. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 296, 1035–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (75).Ji RC (2005) Characteristics of lymphatic endothelial cells in physiological and pathological conditions. Histology and histopathology 20, 155–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (76).Turini D, Nicita G, Fiorelli C, Selli C, and Villari N (1976) Selective transcatheter arterial embolization of renal carcinoma: an original technique. The Journal of urology 116, 419–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (77).Georgi M, and Freitag B (1980) [Pharmaco-angiography of liver tumours (author's transl)]. Rofo 132, 287–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (78).Li CJ, Miyamoto Y, Kojima Y, and Maeda H (1993) Augmentation of tumour delivery of macromolecular drugs with reduced bone marrow delivery by elevating blood pressure. Br J Cancer 67, 975–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (79).Maeda H (2012) Macromolecular therapeutics in cancer treatment: the EPR effect and beyond. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 164, 138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (80).Maeda H (2012) Vascular permeability in cancer and infection as related to macromolecular drug delivery, with emphasis on the EPR effect for tumor-selective drug targeting. Proceedings of the Japan Academy. Series B, Physical and biological sciences 88, 53–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (81).Maeda H (2014) Research spotlight: emergence of EPR effect theory and development of clinical applications for cancer therapy. Therapeutic delivery 5, 627–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (82).Maeda H, Bharate GY, and Daruwalla J (2009) Polymeric drugs for efficient tumor-targeted drug delivery based on EPR-effect. European journal of pharmaceutics and biopharmaceutics : official journal of Arbeitsgemeinschaft fur Pharmazeutische Verfahrenstechnik e.V 71, 409–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (83).Miyamoto Y, and Maeda H (1991) Enhancement by verapamil of neocarzinostatin action on multidrug-resistant Chinese hamster ovary cells: possible release of nonprotein chromophore in cells. Japanese journal of cancer research : Gann 82, 351–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (84).Seki T, Fang J, and Maeda H (2009) Enhanced delivery of macromolecular antitumor drugs to tumors by nitroglycerin application. Cancer Sci 100, 2426–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (85).Fang J, Qin H, Nakamura H, Tsukigawa K, Shin T, and Maeda H (2012) Carbon monoxide, generated by heme oxygenase-1, mediates the enhanced permeability and retention effect in solid tumors. Cancer Sci 103, 535–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (86).Yin H, Fang J, Liao L, Nakamura H, and Maeda H (2014) Styrene-maleic acid copolymer-encapsulated CORM2, a water-soluble carbon monoxide (CO) donor with a constant CO-releasing property, exhibits therapeutic potential for inflammatory bowel disease. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 187, 14–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (87).Yasuda H (2008) Solid tumor physiology and hypoxia-induced chemo/radio-resistance: novel strategy for cancer therapy: nitric oxide donor as a therapeutic enhancer. Nitric oxide : biology and chemistry / official journal of the Nitric Oxide Society 19, 205–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (88).Yasuda H, Yamaya M, Nakayama K, Sasaki T, Ebihara S, Kanda A, Asada M, Inoue D, Suzuki T, Okazaki T, et al. (2006) Randomized phase II trial comparing nitroglycerin plus vinorelbine and cisplatin with vinorelbine and cisplatin alone in previously untreated stage IIIB/IV non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 24, 688–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (89).Del Rosso M, Fibbi G, Pucci M, Margheri F, and Serrati S (2008) The plasminogen activation system in inflammation. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library 13, 4667–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (90).Maeda H, Wu J, Okamoto T, Maruo K, and Akaike T (1999) Kallikrein-kinin in infection and cancer. Immunopharmacology 43, 115–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (91).Kou R, Greif D, and Michel T (2002) Dephosphorylation of endothelial nitric-oxide synthase by vascular endothelial growth factor. Implications for the vascular responses to cyclosporin A. J Biol Chem 277, 29669–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (92).Wu J, Akaike T, and Maeda H (1998) Modulation of enhanced vascular permeability in tumors by a bradykinin antagonist, a cyclooxygenase inhibitor, and a nitric oxide scavenger. Cancer Res 58, 159–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (93).Reichman HR, Farrell CL, and Del Maestro RF (1986) Effects of steroids and nonsteroid anti-inflammatory agents on vascular permeability in a rat glioma model. Journal of neurosurgery 65, 233–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (94).Chand N, and Eyre P (1977) Bradykinin relaxes contracted airways through prostaglandin production. The Journal of pharmacy and pharmacology 29, 387–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (95).Furuta I, Yamada H, Sagawa T, and Fujimoto S (2000) Effects of inflammatory cytokines on prostaglandin E(2) production from human amnion cells cultured in serum-free condition. Gynecologic and obstetric investigation 49, 93–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (96).Tanaka S, Akaike T, Wu J, Fang J, Sawa T, Ogawa M, Beppu T, and Maeda H (2003) Modulation of tumor-selective vascular blood flow and extravasation by the stable prostaglandin 12 analogue beraprost sodium. Journal of drug targeting 11, 45–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (97).Ansiaux R, Baudelet C, Cron GO, Segers J, Dessy C, Martinive P, De Wever J, Verrax J, Wauthier V, Beghein N, et al. (2006) Botulinum toxin potentiates cancer radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res 12, 1276–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (98).Theek B, Baues M, Ojha T, Mockel D, Veettil SK, Steitz J, van Bloois L, Storm G, Kiessling F, and Lammers T (2016) Sonoporation enhances liposome accumulation and penetration in tumors with low EPR. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (99).Ho YJ, Chang YC, and Yeh CK (2016) Improving Nanoparticle Penetration in Tumors by Vascular Disruption with Acoustic Droplet Vaporization. Theranostics 6, 392–403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (100).Folkman J, Watson K, Ingber D, and Hanahan D (1989) Induction of angiogenesis during the transition from hyperplasia to neoplasia. Nature 339, 58–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (101).Chen W, Tang T, Eastham-Anderson J, Dunlap D, Alicke B, Nannini M, Gould S, Yauch R, Modrusan Z, DuPree KJ, et al. (2011) Canonical hedgehog signaling augments tumor angiogenesis by induction of VEGF-A in stromal perivascular cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 108, 9589–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (102).Kerbel RS (2008) Tumor angiogenesis. N Engl J Med 358, 2039–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (103).Stan RV, Tse D, Deharvengt SJ, Smits NC, Xu Y, Luciano MR, McGarry CL, Buitendijk M, Nemani KV, Elgueta R, et al. (2012) The diaphragms of fenestrated endothelia: gatekeepers of vascular permeability and blood composition. Developmental cell 23, 1203–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (104).Monsky WL, Fukumura D, Gohongi T, Ancukiewcz M, Weich HA, Torchilin VP, Yuan F, and Jain RK (1999) Augmentation of transvascular transport of macromolecules and nanoparticles in tumors using vascular endothelial growth factor. Cancer Res 59, 4129–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (105).Helson L, Green S, Carswell E, and Old LJ (1975) Effect of tumour necrosis factor on cultured human melanoma cells. Nature 258, 731–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (106).Eggermont AM, Schraffordt Koops H, Lienard D, Kroon BB, van Geel AN, Hoekstra HJ, and Lejeune FJ (1996) Isolated limb perfusion with high-dose tumor necrosis factor-alpha in combination with interferon-gamma and melphalan for nonresectable extremity soft tissue sarcomas: a multicenter trial. J Clin Oncol 14, 2653–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (107).Eggermont AM, van Geel AN, de Wilt JH, and ten Hagen TL (2003) The role of isolated limb perfusion for melanoma confined to the extremities. Surg Clin North Am 83, 371–84, ix. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (108).Fraker DL, Alexander HR, Andrich M, and Rosenberg SA (1996) Treatment of patients with melanoma of the extremity using hyperthermic isolated limb perfusion with melphalan, tumor necrosis factor, and interferon gamma: results of a tumor necrosis factor dose-escalation study. J Clin Oncol 14, 479–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (109).Lienard D, Ewalenko P, Delmotte JJ, Renard N, and Lejeune FJ (1992) High-dose recombinant tumor necrosis factor alpha in combination with interferon gamma and melphalan in isolation perfusion of the limbs for melanoma and sarcoma. J Clin Oncol 10, 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (110).Kong G, Braun RD, and Dewhirst MW (2000) Hyperthermia enables tumor-specific nanoparticle delivery: effect of particle size. Cancer Res 60, 4440–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (111).Li L, ten Hagen TL, Bolkestein M, Gasselhuber A, Yatvin J, van Rhoon GC, Eggermont AM, Haemmerich D, and Koning GA (2013) Improved intratumoral nanoparticle extravasation and penetration by mild hyperthermia. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 167, 130–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (112).Liu P, Zhang A, Xu Y, and Xu LX (2005) Study of non-uniform nanoparticle liposome extravasation in tumour. International journal of hyperthermia : the official journal of European Society for Hyperthermic Oncology, North American Hyperthermia Group 21, 259–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (113).Ranjan A, Jacobs GC, Woods DL, Negussie AH, Partanen A, Yarmolenko PS, Gacchina CE, Sharma KV, Frenkel V, Wood BJ, et al. (2012) Image-guided drug delivery with magnetic resonance guided high intensity focused ultrasound and temperature sensitive liposomes in a rabbit Vx2 tumor model. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 158, 487–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (114).Dromi S, Frenkel V, Luk A, Traughber B, Angstadt M, Bur M, Poff J, Xie J, Libutti SK, Li KC, et al. (2007) Pulsed-high intensity focused ultrasound and low temperature-sensitive liposomes for enhanced targeted drug delivery and antitumor effect. Clin Cancer Res 13, 2722–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (115).Frenkel V (2008) Ultrasound mediated delivery of drugs and genes to solid tumors. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60, 1193–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (116).Deckers R, and Moonen CT (2010) Ultrasound triggered, image guided, local drug delivery. Journal of controlled release : official journal of the Controlled Release Society 148, 25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (117).Ferrara KW (2008) Driving delivery vehicles with ultrasound. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 60, 1097–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (118).Fang J, Nakamura H, and Maeda H (2011) The EPR effect: Unique features of tumor blood vessels for drug delivery, factors involved, and limitations and augmentation of the effect. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 63, 136–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (119).Hicks KO, Pruijn FB, Secomb TW, Hay MP, Hsu R, Brown JM, Denny WA, Dewhirst MW, and Wilson WR (2006) Use of three-dimensional tissue cultures to model extravascular transport and predict in vivo activity of hypoxia-targeted anticancer drugs. J Natl Cancer Inst 98, 1118–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (120).Goel S, Wong AH, and Jain RK (2012) Vascular normalization as a therapeutic strategy for malignant and nonmalignant disease. Cold Spring Harbor perspectives in medicine 2, a006486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (121).Turley RS, Fontanella AN, Padussis JC, Toshimitsu H, Tokuhisa Y, Cho EH, Hanna G, Beasley GM, Augustine CK, Dewhirst MW, et al. (2012) Bevacizumab-induced alterations in vascular permeability and drug delivery: a novel approach to augment regional chemotherapy for in-transit melanoma. Clin Cancer Res 18, 3328–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (122).Wildiers H, Guetens G, De Boeck G, Verbeken E, Landuyt B, Landuyt W, de Bruijn EA, and van Oosterom AT (2003) Effect of antivascular endothelial growth factor treatment on the intratumoral uptake of CPT-11. Br J Cancer 88, 1979–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (123).Chauhan VP, Stylianopoulos T, Martin JD, Popovic Z, Chen O, Kamoun WS, Bawendi MG, Fukumura D, and Jain RK (2012) Normalization of tumour blood vessels improves the delivery of nanomedicines in a size-dependent manner. Nature nanotechnology 7, 383–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (124).Jain RK (2001) Normalizing tumor vasculature with anti-angiogenic therapy: a new paradigm for combination therapy. Nature medicine 7, 987–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (125).Sriraman SK, Aryasomayajula B, and Torchilin VP (2014) Barriers to drug delivery in solid tumors. Tissue barriers 2, e29528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (126).Taghian AG, Abi-Raad R, Assaad SI, Casty A, Ancukiewicz M, Yeh E, Molokhia P, Attia K, Sullivan T, Kuter I, et al. (2005) Paclitaxel decreases the interstitial fluid pressure and improves oxygenation in breast cancers in patients treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy: clinical implications. J Clin Oncol 23, 1951–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]