Abstract

Introduction

The unprecedented COVID-19 pandemic has exposed healthcare professionals (HCPs) to exceptional situations that can lead to increased anxiety (ie, infection anxiety and perceived vulnerability), traumatic stress and depression. We will investigate the development of these psychological disturbances in HCPs at the treatment front line and second line during the COVID-19 pandemic over a 12-month period in different countries. Additionally, we will explore whether personal resilience factors and a work-related sense of coherence influence the development of mental health problems in HCPs.

Methods and analysis

We plan to carry out a sequential qualitative–quantitative mixed-methods design study. The quantitative phase consists of a longitudinal online survey based on six validated questionnaires, to be completed at three points in time. A qualitative analysis will follow at the end of the pandemic to comprise at least nine semistructured interviews. The a priori sample size for the survey will be a minimum of 160 participants, which we will extend to 400, to compensate for dropout. Recruitment into the study will be through personal invitations and the ‘snowballing’ sampling technique. Hierarchical linear regression combined with qualitative data analysis, will facilitate greater understanding of any associations between resilience and mental health issues in HCPs during pandemics.

Ethics and dissemination

The study participants will provide electronic informed consent. All recorded data will be stored on a secured research server at the study site, which will only be accessible to the investigators. The Bern Cantonal Ethics Committee has waiv ed the need for ethical approval (Req-2020–00355, 1 April 2020). There are no ethical, legal or security issues regarding the data collection, processing, storage and dissemination in this project.

Trial registration number

Keywords: mental health, anxiety disorders, depression and mood disorders, public health, primary care, statistics and research methods

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The mixed-methods design with quantitative and qualitative phases that include several validated instruments and the matched follow-up and semistructured interviews will provide substantial insight on the state and development of psychological health and the thoughts of healthcare professionals (HCPs) during infectious pandemics in several countries.

The sophisticated statistical analysis will include a clustered hierarchical data structure and any imbalanced data by allowing residual components at each level in the hierarchy.

Interdisciplinary and interprofessional cooperation between physicians and health psychologists will combine different research approaches and will therefore yield more holistic data by bridging disciplinary gaps.

The participating HCPs might not be representative of the entire population and for all countries.

The survey will be accessible in English, to target a broad participation of international HCPs. This may limit participation and compliance of HCPs in regions where English is not common and may introduce biases due to under-representation or misunderstandings.

Introduction

In December 2019, a new coronavirus, known as severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), appeared for the first time in Wuhan, China. SARS-CoV-2 causes COVID-19, which can lead to severe hypoxaemic pneumonia and other serious complications. Despite containment measures, the virus spread exponentially. The first case outside China was reported on 13 January 2020 in Thailand, which was connected to travel to Wuhan.1 On 11 March 2020, the WHO defined the COVID-19 outbreak as a pandemic.2 In Europe, an Italian cluster developed exponentially, with the first deaths reported on 23 February 2020.3 It was soon clear that the health system in northern Italy could not cope with the large numbers of new patients with respiratory failure who required invasive ventilation support.4 The COVID-19 pandemic put healthcare professionals (HCPs) in an unprecedented situation. The long working hours, the need for ‘hard triage’5 6 for ventilation support and the tight restrictions on daily life implemented by the government had serious effects on both healthcare workers and the general population.7

Infectious diseases arise frequently and nearly every year. However, these seldom challenge healthcare systems (eg, limited capacity of hospital beds and understaffing of personnel) in the way seen for the COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, data on the impact of such pandemics on HCPs are still not available.

A recent study from China showed a high prevalence of mental health symptoms among all HCPs, including depression, insomnia, anxiety or trauma–stress disorder,8 similar to those experienced by military personnel after participation in war scenarios.9 Front-line HCPs who are involved in diagnosis, treatment and care of patients with COVID-198 are at particular risk of developing psychological distress and other mental health symptoms.8 10 HCPs are expected to be under the highest perceived threat of COVID-19, and if they believe that their infection with COVID-19 is likely (ie, perceived vulnerability), this might have serious consequences on their own health. Additionally, concerns about the spread of the virus to their family members or friends, their need for self-isolation, their feelings of not having enough support and their exposure to the catastrophic news in the media are believed to have a role in the development of such symptoms.8–11 These negative stress outcomes can impact not only on the well-being of HCPs but also on their ability to care effectively for others.12 13

At the other end of the spectrum, people who have to endure significant challenges might experience a degree of post-traumatic growth,14 which is a term used to describe the strengthening of psychological resilience and values after exposure to particularly demanding situations.15 Although there is as yet no universal definition, psychological resilience is generally considered to be multidimensional and to consist of behaviours, thoughts and actions. In short, resilience refers to positive adaptation despite adversity.16 17 Adopting resilience-enhancing strategies might therefore improve the day-to-day performance of HCPs at work.18

Personal resilience is also related to a sense of ‘coherence’.18 19 A sense of coherence is defined as a disposition to perceive life circumstances as manageable, comprehensible and meaningful. This might influence individuals’ resilience by making them more adaptable in dealing with distress and adverse events.18–21 People with a strong sense of coherence are less prone to burn-out and are generally healthier.13 22–25

Due to the increasing prevalence of emerging infectious diseases (eg, SARS-CoV-1, Middle East respiratory syndrome-CoV) and other worldwide catastrophic events, the capacity to adapt is important, as it allows HCPs to act effectively and to stay healthy in potentially life-threatening situations.18 More information about associations between resilience factors and a work-related sense of coherence of HCPs in such situations will help to counsel and support HCPs who are facing the consequences of ‘COVID-19 anxiety’, perceived vulnerability, hopelessness, depression and traumatic–stress symptoms.

This project is designed to primarily determine the degree of COVID-19 anxiety, perceived vulnerability, depression and traumatic–stress symptoms and their variation in HCPs for specific time periods and regions around the world. Additionally, the aim was to explore differences in COVID-19 anxiety, perceived vulnerability, depression and traumatic–stress symptoms between front-line (HCPs directly treating patients with COVID-19) and second-line (HCPs not involved in direct care of patients with COVID-19) HCPs. A third aim was to determine whether there are any associations between these factors and individual resilience and a work-related sense of coherence across the different phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Therefore, the research questions of this study are as follows:

Do COVID-19 anxiety and perceived vulnerability differ over time between different countries?

Do COVID-19 anxiety and perceived vulnerability differ over time between first-line and second-line HCPs?

How do individual resilience and a work-related sense of coherence influence the development of COVID-19 anxiety, perceived vulnerability, depression and traumatic–stress symptoms during the different phases of a pandemic outbreak?

How do individual resilience and a work-related sense of coherence influence the development of COVID-19 anxiety, perceived vulnerability, depression and traumatic–stress symptoms of front-line HCPs?

What factors contribute to or alleviate COVID-19 anxiety and perceived vulnerability over the study period for first-line HCPs?

Which components of individual resilience and a work-related sense of coherence influence the development of COVID-19 anxiety, perceived vulnerability, depression and traumatic–stress symptoms during the study phases for front-line HCPs?

Methods and analysis

Study design overview

We will conduct a sequential mixed-methods study based on an explanatory design.26 The first quantitative phase will explore the association of individual resilience, a work-related sense of coherence and the development of mental health symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic, and their variations over time, between countries and between front-line and second-line HCPs. The qualitative phase, collected and analysed after the quantitative phase, will consist of semistructured interviews and will elaborate on the development of mental health symptoms, use of coping strategies and personal resilience factors during the COVID-19 pandemic in front-line HCPs. The combination of these two methodological approaches will allow triangulation and provide a more granular understanding of the processes involved in any associations with anxiety, perceived vulnerability, depression, traumatic–stress symptoms and resilience factors over the course of the current COVID-19 pandemic. The quantitative data and their subsequent analysis will provide a general understanding of the development of mental health symptoms during the pandemic, while the qualitative data and their analysis will refine and explain the statistical findings more in-depth by exploring participants’ views, thoughts and feelings.27–29 Data collection will be sequential (first quantitative and then qualitative), but both study parts will be given equal priority.

Quantitative phase: longitudinal online survey

Data collection

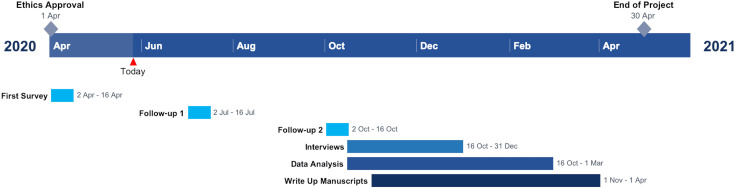

An online survey was launched on 2 April 2020, in English. This will collect data for 2 weeks. The follow-ups are planned for July and October 2020, over another 2-week period. Depending on the results of the follow-ups, a third might be added in late 2020.

The longitudinal internet-based survey is a 64-item questionnaire (online supplementary digital content 1) based on six pre-existing validated self-reporting questionnaires and demographic data. This questionnaire is hosted online at Qualtrics (Provo, Utah, USA), which restricts access to one response per device.

bmjopen-2020-039832supp001.pdf (114.7KB, pdf)

The survey link will be primarily distributed through social media (LinkedIn, Facebook, Twitter, WhatsApp and Threema), using the ‘snowballing’ sampling technique.30–32 Later, personal contacts via email invitations from all of the authors will invite further study participants, with supporting (inter)national societies emailing the link via their own mailing lists to better distribute the survey. Contact persons are asked to further distribute the survey to promote the greatest number of responses as possible over the entire study period.

To minimise the possibility of attrition bias, we ensure a good communication between study coordinators and participants, send several personalised follow-up invitations and apply an oversampling technique.33 Moreover, we contacted several HCP associations and societies in different countries to ensure an HCP-oriented distribution of the survey and to minimise sample selectivity bias. We undertook a short pilot testing with the coauthors and some of the authors’ colleagues.

Participant inclusion and exclusion criteria

We will include HCPs over 18 years of age who agree to participate. An HCP is defined as a postgraduate person listed in the submajor group 22 (health professionals), according to the International Standard Classification of Occupations, with exclusion of minor group 225 (veterinarians).34 This includes medical doctors, nursing and midwifery professionals, traditional and complementary medicine professionals, paramedical practitioners, dentists, pharmacists and environmental and occupational health and hygiene professionals. All participants who do not comply with these criteria will be excluded.

Measurements

The primary outcome of this study is the variation in COVID-19 anxiety in different regions, over three time periods, measured using a modified version of the Swine Influenza Anxiety Items,35 a 10-item survey developed to measure anxiety disorders and somatisation (Cronbach’s alpha=0.85).

The secondary outcomes will include

The Perceived Vulnerability to Disease questionnaire score,36 a 15-item tool used to measure subjective vulnerability to disease (Cronbach’s alpha=0.82).

The Patient Health Questionnaire score,37 a 9-item tool developed for depression evaluation (Cronbach’s alpha=0.89).

The Impact of Event Scale-6 score,38 a 6-item tool for evaluation of symptoms of post-traumatic stress reactions (Cronbach’s alpha=0.80).

The Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC)-10 score,39 a 10-item tool, a short version of the CD-RISC-25,40 to evaluate individual resilience (Cronbach’s alpha=0.85).

The Work-Sense of Coherence Scale score,41 a 9-item tool to evaluate the perceived comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness of an individual’s current work situation (Cronbach’s alpha=0.83).

A globally measured current risk perception for becoming infected while working, as assessed by a self-created item, ‘I am afraid I will become infected with COVID-19 while on the job’ (measured on a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10).

A globally measured current perception of stress at work, as a second self-created item, ‘How stressful is your current work situation for you?’ (measured on a visual analogue scale from 0 to 10).

Sociodemographic variables and work-related and COVID-19-related characteristics: country and city of current occupation, age, sex, profession, main working place, years working in the healthcare system, belonging to a risk population, sharing a household with other people, being in a relationship, having children, being pregnant or living with a pregnant woman, private close contact with people belonging to the risk population, having had direct contact with COVID-19-infected patients, being infected with COVID-19 and having been positively tested for COVID-19 antibodies.

Sample size calculation

The required sample size was calculated using an a priori power analysis with G*Power V.3.1.42 Assuming a small effect size (f2=0.15) for a repeated-measure analysis of variance with three time points and within–between interaction (α=0.05, 1-β=0.95), we found that the minimum required sample size for four language groups was n=160. To compensate for drop-out over the three measurement times, we will aim for 400 responders.

Statistical analysis plan

To accommodate between effects and within effects in light of possibly unequal numbers of observations, hierarchical linear mixed models will be fit to the longitudinal measures of the primary and secondary outcome variables.43 Hierarchical linear regression accounts for non-independence of observations and attrition inherent in longitudinal data.43 The analyses will be conducted using the R-package: nlme44 in R Statistical Language,45 using full maximum likelihood estimations. The normal distributions of the outcome variables will be examined by residual diagnostics of the fitted multilevel models.

For each primary and secondary outcome variables, the analysis will proceed according to different steps.43 First, a null model (intercept-only model) will be estimated, which allows an estimation of the proportion of variation in the outcome variables, that is, between and within the persons in the sample. The first model (unconditional growth model with random intercept) will examine the within-persons trajectories of change across measurement points. The second model (conditional growth model with random intercept and cross-level interactions) will examine the effects of country/front-line and second-line HCPs across the different times (ie, the pandemic phase).

To address the research questions that are focused on the relationships between the different outcome variables and the resilience and work-related sense of coherence, structural equation modelling will be performed.46 These analyses will be carried out using the R-package: lavaan47 in the R Statistical Language,45 using full maximum likelihood estimation.

Statistical strategies for dealing with threats to internal validity (ie, attrition bias, sample selectivity bias and multiple-testing bias) include extensive drop-out analyses,33 reporting of attrition by socioeconomic factors,33 statistical comparison of participants’ key characteristics with population characteristics and application of linear hierarchical regression analyses, which include all available data41 and compensate for multiple testing.48

Qualitative phase: semistructured interviews

Data collection

After completion of the online survey, the participants will be invited to participate in the semistructured interviews. We will select all of the participants for the qualitative phase according to availability and region. We will select them from the pool used in the quantitative phase, so as to best represent their experience and views. As the study is sequential in nature, it is impossible to pre-emptively select participants for the qualitative phase. Therefore, we will perform stratified purposive sampling into homogeneous focus groups, stratified by front-liners or second-liners, profession and country of origin, to enable comparisons.49 50 We aimed to perform at least nine semistructured interview groups. All interviews will be coded in a phased fashion, with interim analysis to check for saturation (ie, when additional data do not lead to any new themes). If saturation is not reached, three more interviews will be performed. Sixty-minute semistructured interviews will be conducted after the quantitative phase is finished, in different locations in Europe. The aim was to explore participants’ views on the influence of resilience and a work-related sense of coherence on the development of anxiety, depression and trauma–stress disorder during the pandemic outbreak. We used the protocol proposed by Castillo-Montoya51 to develop a semistructured interview guide (online supplementary digital content 2). We first ensured that interview questions were aligned with our research questions; we then constructed an inquiry-based conversation; we asked for external feedback on interview protocols; and we will pilot the interview guide in the near future. The interview data will consist of the audio and video recordings, which will be further transcribed by two members of the study team.

bmjopen-2020-039832supp002.pdf (2.4MB, pdf)

Strategies for dealing with threats to validity of the qualitative data used in this study include method triangulation, member-checking (also known as participant validation),52 peer support and an audit trail. The use of triangulation of different data sources will enhance objectivity and strengthen intersubjective agreement.53 A thorough methodological description will also help credibility.

Analysis plan

All of the data will be processed with the software MaxQDA 2020 (Verbi, Berlin, Germany). Data originating from the semistructured interviews will be processed according to the Miles et al54 framework for data analysis. This initially includes data reduction—including segmenting, editing and summarising the data—followed by data display and finally conclusion verification. Two investigators will code the first group interviews independently and will agree on the coding scheme for the remaining interviews. Respondent validation and paired coding will be performed as a way to increase quality. Memoing will be performed parallel to coding.

Trial status

The trial started to recruit participants for the first round of the survey (quantitative data) on 2 April 2020, for a period of 2 weeks. The next rounds are planned for July and October 2020. After the quantitative data collection ends, we will move on to the qualitative phase.

Ethics and dissemination

The Bern Cantonal Ethics Committee waived the need for ethical approval on 1 April 2020, according to the Swiss Act for Human Research (BASEC Nr. 2020–00355, Professor Dr Christian Seiler, Murtenstrasse 31, 3010 Bern, Switzerland, Tel:+41–31–6337070, info.kek.kapa@gef.be.ch). All procedures for this investigation will follow the Helsinki Declaration.55

All of the participants will be sent a link to the survey, with a detailed cover letter that explains the entire project, the purpose of the project, the context of the research and the contacts of the lead investigator (available at https://psyunibe.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3WYgbkLWqiDPDG5). Electronic informed consent to participate will be obtained from all of the participants at the beginning of the survey. Should any participants decide not to participate in the study, their decision will not affect them in any way. No incentives will be offered or given. Participants will be asked for their email to enable contact with them during the follow-up and qualitative phases of the study and for pairing purposes. During the interviews, participants’ faces will not be included in the video recordings, and their performances will not be shared with any external subjects.

All of the researchers involved will comply with the Data Protection Act and the Swiss Law for Human Research. There are no ethical, legal or security issues regarding the data collection, processing, storage and dissemination for this project. We will neither obtain nor generate sensitive data, and we will not sign any confidentiality agreement. All data will be stored for up to 10 years after the project, according to the Swiss Law for Human Research.

This study has been registered at the UK-based International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number. All relevant data generated or used by the research project (ie, raw data, all processed data that directly underlie the reported results, and all ancillary information necessary to understand, evaluate, interpret and reuse the results of the study) will be stored on the official server of the Institute of Psychology, Department of Health Psychology and Behavioural Medicine at the University of Bern. All of the data are, and will be, password protected and only accessible by SA and HE. The datasets will be flagged for long-term storage. Datasets flagged for long-term storage are subjected to specific measures to preserve data integrity and data safety, such as additional backups, regular rewrites to new storage media and redundant storage in third-party repositories.

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study will be available from the primary investigator on reasonable request from university-based research groups with suitable and answerable research questions. The primary investigator will be responsible for ensuring that electronic file permissions are correctly assigned and for advising on other aspects of data storage and security. Both qualitative and quantitative data are expected to be available from March 2021. We expect no limitations with respect to publishing the data.

The study results will be published in a peer-reviewed international medical journal after the first trimester of 2021. A full timeline of the project is shown in figure 1.

Figure 1.

Project timeline.

Public involvement statement

This research will be carried out without patient involvement, as patients are not the study subjects. We have involved the Swiss Association of Assistants and Registrars, the Swiss Society of Anaesthesiology and Reanimation and the European Airway Management Society to comment on the study design and have consulted HCPs on relevant outcomes. After the data analysis, we will invite them to interpret the results again. We have not had time to invite persons outside the study group to contribute to the writing or editing of this document because of the velocity of the progression of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Importance of the study

Despite the large body of literature that is focused on the prevalence of mental health symptoms after catastrophes or natural disasters, the investigation of the resilience of HCPs is scarce, particularly in the face of a surge capacity. In disaster situations, the prevalence of resilience appears to depend on adequate preparedness, good social support and proactive coping styles.9 However, most disaster sites do not impose social distancing and self-isolation procedures, which might further compromise HCPs’ ability to cope. It has been shown before that professionals involved in disaster relief work can develop post-traumatic growth.14 15 Establishing a clear relationship between resilience and a work-related sense of coherence with the development of mental symptoms during exceptional situations like the current COVID-19 pandemic might help to identify HCPs who are both particularly protected and at risk, which will allow adequate distribution of psychological interventions. Organisations can also potentiate resilience in their employees by ensuring that they are adequately trained. This is would be an affordable measure that can save money and resources by keeping the staff at work and avoiding sick leave.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @alexffuchs

Contributors: This study was conceptualised by RG and AF, but all authors contributed equally to the final methodology. JB-E, RG and AF recruited the participants. SA and HE hosted the survey and performed the data collection and analysis. All authors significantly contributed to the writing of the manuscript. The manuscript was reviewed and edited prior to submission, and all authors agreed on the final version.

Funding: This work is supported by an unrestricted grant from the Department of Anaesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, conduct, reporting or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods and analysis section for further details.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Organization WH Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) - situation report 1. World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Organization WH Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation report – 51. World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization WH Novel Coronavirus (2019-nCoV) - situation report 34. World Health Organization, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Remuzzi A, Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet 2020;395:1225–8. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Italian Society of Anesthesia A, Resuscitation and Intensive Care (SIAARTI) Clinical ethics recommendations for the allocation of intensive care treatment, in exceptional, resource-limited circumstances, 2020. Available: http://www.siaarti.it/SiteAssets/News/COVID19%20-%20documenti%20SIAARTI/SIAARTI%20-%20Covid-19%20-%20Clinical%20Ethics%20Reccomendations.pdf [Accessed 02 Apr 2020].

- 6.Bouadma L, Lescure F-X, Lucet J-C, et al. Severe SARS-CoV-2 infections: practical considerations and management strategy for intensivists. Intensive Care Med 2020;46:579–82. 10.1007/s00134-020-05967-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson E, Hershenfield K, Grace SL, et al. The psychosocial effects of being quarantined following exposure to SARS: a qualitative study of Toronto health care workers. Can J Psychiatry 2004;49:403–7. 10.1177/070674370404900612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelly FE, Osborn M, Stacey MS. Improving resilience in anaesthesia and intensive care medicine - learning lessons from the military. Anaesthesia 2020;75:720-723. 10.1111/anae.14911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee AM, Wong JGWS, McAlonan GM, et al. Stress and psychological distress among SARS survivors 1 year after the outbreak. Can J Psychiatry 2007;52:233–40. 10.1177/070674370705200405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wong TW, Yau JKY, Chan CLW, et al. The psychological impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak on healthcare workers in emergency departments and how they cope. Eur J Emerg Med 2005;12:13–18. 10.1097/00063110-200502000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barnett JE, Baker EK, Elman NS, et al. In pursuit of wellness: the self-care imperative. Prof Psychol 2007;38:603–12. 10.1037/0735-7028.38.6.603 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Van der Colff JJ, Rothmann S, et al. Occupational stress, sense of coherence, coping, burnout and work engagement of registered nurses in South Africa. SA j ind psychol 2009;35:1–10. 10.4102/sajip.v35i1.423 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brooks S, Amlôt R, Rubin GJ, et al. Psychological resilience and post-traumatic growth in disaster-exposed organisations: overview of the literature. BMJ Mil Health 2020;166:52–6. 10.1136/jramc-2017-000876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, et al. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ 2020;368:m1211. 10.1136/bmj.m1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luthar S. Resilience in development: A synthesis of research across five decades : Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, Developmental psychopathology: risk, disorder, and adaptation. 2 edn New York: John Wiley & Sons Inc, 2006: 739–95. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manyena SB. The concept of resilience revisited. Disasters 2006;30:434–50. 10.1111/j.0361-3666.2006.00331.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Streb M, Häller P, Michael T. PTSD in paramedics: resilience and sense of coherence. Behav Cogn Psychother 2014;42:452–63. 10.1017/S1352465813000337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky's sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health 2006;60:376–81. 10.1136/jech.2005.041616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Antonovsky A. Unraveling the mystery of health: how people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-bass, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Antonovsky H, Sagy S. The development of a sense of coherence and its impact on responses to stress situations. J Soc Psychol 1986;126:213–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gilbar O. Relationship between burnout and sense of coherence in health social workers. Soc Work Health Care 1998;26:39–49. 10.1300/J010v26n03_03 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Levert T, Lucas M, Ortlepp K. Burnout in psychiatric nurses: contributions of the work environment and a sense of coherence. S Afr J Psychol 2000;30:36–43. 10.1177/008124630003000205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tselebis A, Moulou A, Ilias I. Burnout versus depression and sense of coherence: study of Greek nursing staff. Nurs Health Sci 2001;3:69–71. 10.1046/j.1442-2018.2001.00074.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pahkin K, Väänänen A, Koskinen A, et al. Organizational change and employees’ mental health: the protective role of sense of coherence. J Occupat Environ Med 2011;53:118–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schifferdecker KE, Reed VA. Using mixed methods research in medical education: basic guidelines for researchers. Med Educ 2009;43:637–44. 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03386.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossman GB, Wilson BL. Numbers and words: combining quantitative and qualitative methods in a single large-scale evaluation study. Eval Rev 1985;9:627–43. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tashakkori A, Teddlie C, Teddlie CB. Mixed methodology: combining qualitative and quantitative approaches. Sage, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Creswell J. Research design: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches. 4 edn Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baltar F, Brunet I. Social research 2.0: virtual snowball sampling method using Facebook. Internet Res 2012;22:57–74. 10.1108/10662241211199960 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zdravkovic M, Berger-Estilita J, Sorbello M, et al. An international survey about rapid sequence intubation of 10,003 anaesthetists and 16 airway experts. Anaesthesia 2020;75:313–22. 10.1111/anae.14867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zdravkovic M, Osinova D, Brull SJ, et al. Perceptions of gender equity in departmental leadership, research opportunities, and clinical work attitudes: an international survey of 11 781 anaesthesiologists. Br J Anaesth 2020;124:e160–70. 10.1016/j.bja.2019.12.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hindmarch P, Hawkins A, McColl E, et al. Recruitment and retention strategies and the examination of attrition bias in a randomised controlled trial in children's centres serving families in disadvantaged areas of England. Trials 2015;16:79. 10.1186/s13063-015-0578-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ganzeboom HB International standard classification of occupations ISCO-08 with ISEI-08 scores Geneva: international labour office, 2012. Available: www.ilo.org/public/english/bureau/stat/isco/docs/publication08.pdf

- 35.Wheaton MG, Abramowitz JS, Berman NC, et al. Psychological predictors of anxiety in response to the H1N1 (swine flu) pandemic. Cognit Ther Res 2012;36:210–8. 10.1007/s10608-011-9353-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Duncan LA, Schaller M, Park JH. Perceived vulnerability to disease: development and validation of a 15-item self-report instrument. Pers Individ Differ 2009;47:541–6. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thoresen S, Tambs K, Hussain A, et al. Brief measure of posttraumatic stress reactions: impact of event scale-6. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2010;45:405–12. 10.1007/s00127-009-0073-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Campbell-Sills L, Stein MB. Psychometric analysis and refinement of the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC): validation of a 10-item measure of resilience. J Trauma Stress 2007;20:1019–28. 10.1002/jts.20271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Connor KM, Davidson JRT. Development of a new resilience scale: the connor-davidson resilience scale (CD-RISC). Depress Anxiety 2003;18:76–82. 10.1002/da.10113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vogt K, Jenny GJ, Bauer GF. Comprehensibility, manageability and meaningfulness at work: construct validity of a scale measuring work-related sense of coherence. SA j ind psychol 2013;39:1–8. 10.4102/sajip.v39i1.1111 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang A-G, et al. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007;39:175–91. 10.3758/bf03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pinheiro J, Bates D, DebRoy S, et al. Linear and nonlinear mixed effects models, 2007: 57. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Team RC R: a language and environment for statistical computing Vienna, Austria, 2013. Available: https://www.r-project.org

- 46.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford publications, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rosseel Y. Structural equation modeling with lavaan. J Stat Softw 2012;48:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gelman A, Hill J, Yajima M. Why we (usually) don't have to worry about multiple comparisons. J Res Educ Eff 2012;5:189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Teddlie C, Tashakkori A. Foundations of mixed methods research: integrating quantitative and qualitative approaches in the social and behavioral sciences. Sage, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teddlie C, Yu F. Mixed methods sampling: a typology with examples. J Mixed Methods Res 2007;1:77–100. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Castillo-Montoya M. Preparing for interview research: the interview protocol refinement framework. Qual Rep 2016;21. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Morse JM. Critical analysis of strategies for determining rigor in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res 2015;25:1212–22. 10.1177/1049732315588501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Robson C, McCartan K. Real world research: a resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. 4 edn Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldaña J. Qualitative data analysis: a methods sourcebook. 3 edn Thousand Oaks, California: Sage, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 55.World Medical Association World medical association declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013;310:2191–4. 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-039832supp001.pdf (114.7KB, pdf)

bmjopen-2020-039832supp002.pdf (2.4MB, pdf)