Abstract

Introduction:

Pharmacists have been well recognized as an active and have a more integrated role in the preventive services within the National Health Services. This study assessed the community pharmacists’ attitudes, beliefs, and practices toward oral health in the Malaysian setting.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey-based study was used to conduct this project. An anonymous self-administered questionnaire was developed and distributed among community pharmacists within Kuala Lumpur and Selangor states areas, Malaysia. The data collection was carried out from the beginning of November to the end of December 2018.

Results:

Of the 255 pharmacists, 206 agreed to participate in the study, yielding a response rate of 80.8%. Overall, approximately half of the pharmacists provided two to five oral health consultations per week and two to five over the counter (OTC) oral health products recommendations per week. The main services provided by community pharmacists in were the provision of OTC treatments (93.7%), referral of consumers to dental or medical practitioners when appropriate (82.5%), and identify signs and symptoms of oral health problems in patients (77.2%). In addition, more than 80% of the pharmacists viewed positively and supported integrating oral health promotion and preventive measures into their practices. The most commonly reported barriers to extending the roles of pharmacists in oral health care include lack of knowledge or training in this field, lack of training resources, and lack of oral health educational promotion materials.

Conclusion:

The study shows that community pharmacists had been providing a certain level of oral health services and play an important role in oral health. The findings highlighted the need of an interprofessional partnership between the pharmacy professional bodies with Malaysian dental associations to develop, and evaluate evidence-based resources, guidelines, the scope of oral health in pharmacy curricula and services to deliver improved oral health care within Malaysian communities.

KEYWORDS: Attitude, community pharmacy, dental services, Malaysia, oral health, pharmacist

INTRODUCTION

Oral health is essential to general health and quality of life. It can be defined as being free from any diseases or disorders that refrain an individual from biting, chewing, smiling, speaking, and psychosocial well-being.[1] Although the majority of the oral conditions are not life-threatening, quality of life can be affected because of the consequences of poor oral health. The high cost of dental treatment has been a burden to the community, especially among poor and socially disadvantaged individuals.[2] The expenditure in Malaysia on oral health-care services in 2015 was estimated at RM401.2 million, equivalent to approximately 3.4% of total national health expenditure.[3] Interprofessional teamwork between pharmacist and dentistry may help to encourage community pharmacist to take a more active role in promoting oral health. By providing information and assistance for self-care and the use of over the counter (OTC) products for minor problems on oral health, it can greatly reduce the dental cost of consumers and provide better patient care in the Malaysian health-care system.[4] Community pharmacies play an essential role in providing primary health-care services. They could be the first health-care professionals that contact with the public in regards to oral health because of convenient accessibility and are based within the centre of the local community.[5,6]

The pharmacist’s role is undergoing significant changes whereby the role has evolved from merely compounding and dispensing to include a broader range of functions relating to primary care. Pharmacists have been considered for an active and more integrated role in the preventive services within the National Health Services (NHS) including assisting patients in self-monitoring of their blood glucose levels and blood pressure levels. They provide medication counseling for noncommunicable diseases and help to increase patient’s compliance and adherence to medication therapy.[7] Community pharmacies may also logistically serve as ideal health-care destinations to implement and deliver prevention, early intervention, and referral of oral health services to reduce the incidence of potentially preventable oral conditions including tooth decay, gum disease, and oral cancer. Community pharmacy staff play a critical role in delivering quality health care to people of all income levels and stages of life because of their trustworthy, knowledgeable, and well-respected health-care professionals.[8]

According to a National Survey on the Quality Use of Medicine (NSUM) in 2015, of 3000 consumers in Malaysia.[9] Around 76% of them obtained their medical supplies from a retail pharmacy. Moreover, 70% of them reported that they require additional counseling with the pharmacist to better understand and overcome any difficulty with their medicines. This reflects that although the role of the community pharmacist in the health-care system of Malaysia is growing continuously, there are still opportunities for enhancement in pharmacist’s role focusing on patient-centered care in the near future.[9] The overall prevalence of reported oral health problems among the Malaysian population was 5.2% (95% CI 4.8–5.6).[3] Risk factors of poor oral health include poor-quality diets, high sugar intake in foods and drinks, inappropriate infant feeding practices, poor hygiene, excessive smoking, and alcohol consumption.[6] Almost all Malaysian experience dental or oral health issue at some time in their lives and the types of oral health-seeking behavior in Malaysia’s population includes self-care/self-medication, seek treatment or advice from health-care providers, purchase medication after obtaining advice from the pharmacist, and seek advice other than from a health-care provider. It was reported that 23.2% of the population seek oral health advice and medication from the pharmacist, thus pharmacists are ideal in providing oral health care and promoting oral health awareness.[3]

There is a paucity in studies that examine the role of community pharmacists in dental services. Previous studies showed that the pharmacist has a key role in oral health services and they are interested to expand their knowledge in this field. Moreover, the studies highlighted the need for growing partnerships between pharmacy and dental health-care professionals.[10,11] To date, there is no information regarding oral health knowledge, attitudes, practice, and skills among practicing community pharmacists in Malaysia. However, there is only one study conducted among undergraduate pharmacy students to assess their knowledge and attitude toward oral health.[12] The purpose of this study was to examine the current role of the Malaysian community pharmacist as oral health advisors. On the basis of the previous literature, it is obvious that pharmacists play an important role in oral health promotion. Therefore, we aimed to carry out this study to assess knowledge, attitudes, practice, and skills of community pharmacists toward addressing oral health issues. Furthermore, data from the study would be useful to help identify any future training requirements to enhance pharmacists’ knowledge of oral conditions and help shape future plans and policies to further provide better primary care for Malaysian consumers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This study adopted an observational cross-sectional survey design. Data collection has been carried out in the period from mid of November 2018 to mid of December 2018 using an anonymous structured questionnaire distributed to pharmacists working in the community setting using convenience sampling method and pharmacists were approached physically. Verbal consent was obtained from all respondents to participate in the study. To show the power of the study, questionnaires were distributed to four destinations of Kuala Lumpur and Selangor (North, South, East, and West) to represent the majority areas of the two states. Only pharmacists who are Malaysian working in the community setting in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor were included, whereas pharmacists who were not willing to participate were excluded. The participated pharmacist must be either Fully Registered Pharmacist (FRP) or Provisionally Registered Pharmacist (PRP) in Malaysia.

The items of the questionnaire were developed based on previous studies.[10,11] The selected items were modified based on the Malaysian context. The content validity of the research questionnaire was done by two experts in the field. The aim was to ensure the suitability of the selected items to the Malaysian context. Then, it was followed by a pilot study among a sample of the population (n = 15 respondents). The reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s α value, which was 0.71 for this questionnaire. It was divided into four sections collecting information to address the objectives of the study: Section A consists of items related to the demographics of the participant; Section B consists of questions related to oral health-care services provided in the pharmacy; Section C comprised questions related to the pharmacist’s attitude, preferences, and opinions regarding oral health-care provision; and Section D includes questions about training areas and further support required in the oral health. The questionnaire responses were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software, version 24.0 (IBM, Guildford, UK). The characteristics of the community pharmacists were described using both descriptive statistics and frequency distributions of the variables. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (ID No. 14230).

RESULTS

A total of 461 invitations were sent to the community pharmacists around Kuala Lumpur and Selangor provinces in Malaysia, with a response rate of 80.8%. Among the 206 returned questionnaires, the majority of participants responded were aged between 25 and 29 (43.2%) years old, female (64.1%), and of Chinese ethnicity (88.3%) [Table 1]. Most of the pharmacists were having a bachelor degree (84.5%), employee pharmacist (61.7%), and only around 26% who received training on oral health care in the past 12 months.

Table 1.

Characteristic of pharmacist who responded to the survey and type of pharmacy (n = 206)

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age | Under 25 | 21 (10.2) |

| 25–29 | 89 (43.2) | |

| 30–39 | 69 (33.5) | |

| 40–49 | 18 (8.7) | |

| 50–59 | 6 (2.9) | |

| 60 and over | 3 (1.5) | |

| Gender | Male | 74 (35.9) |

| Female | 132 (64.1) | |

| Education status | Bachelor | 174 (84.5) |

| Master | 31 (15.0) | |

| Doctorate | 1 (0.5) | |

| Years of experience | 1–5 years | 105 (51.0) |

| 6–10 year | 49 (23.8) | |

| 11–15 years | 26 (12.6) | |

| > 15 years | 26 (12.6) | |

| Type of pharmacy | Single-outlet independent pharmacy | 39 (18.9) |

| Multi-outlet independent pharmacy | 49 (23.8) | |

| Chain pharmacy | 118 (57.3) | |

| Pharmacist position | Pharmacy owner and manager | 29 (14.1) |

| Pharmacy manager | 50 (24.3) | |

| Employee pharmacist | 127 (61.7) | |

| Percentage of worktime on patient facing role | 0–25% | 10 (4.9) |

| 26–50% | 23 (11.2) | |

| 51–75% | 105 (51.0) | |

| 76–100% | 68 (33.0) | |

| CPD training on oral health care in the past 12 months | No | 153 (74.3) |

| Yes | 53 (25.7) |

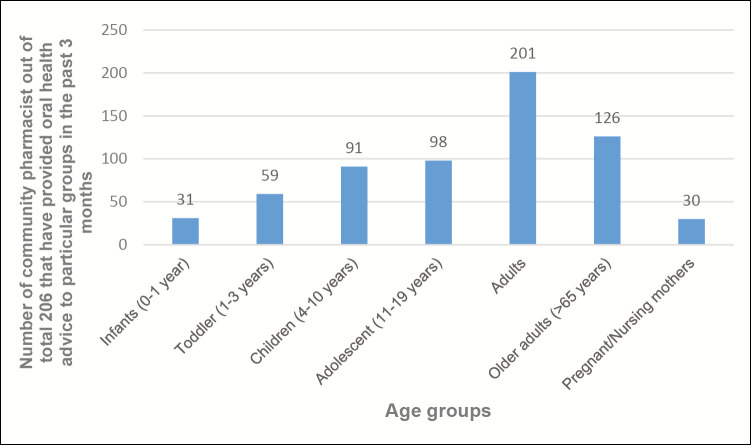

Study findings showed that the main services provided by community pharmacists are the provision of OTC treatments (93.7%), refer the consumer to dental or medical practitioners when appropriate (82.5%), and identify sign and symptoms of oral health problems in patients (77.2%) [Table 2]. The least service provided was holding oral health promotion activities to provide education and raise awareness of issues relevant to oral health (10.7%). In the past 3 months, approximately half of the community pharmacists who responded to the questionnaire provided two to five consultations per week and two to five OTC products recommendations per week. Table 3 shows that most oral health-care products were provided in community pharmacies except high-fluoride oral care products (26.7%), Recaldent® (3.5%), Orthodontic Wax (18%), Dentafix filling repair (8.3%), and Dentist in a Box® dental emergency kits (4.4%). Community pharmacists who participated in this survey provided oral health consultation mainly to adults (96.7%) followed by older adults (61.2%), adolescents (47.6%), children (44.2%), toddler (28.6%), infants (15%), and lastly pregnant or nursing mothers (14.5%) as shown in Figure 1. Consultation time, reference, and acceptability to receiving oral health advice from community pharmacist are shown in Table 4. Approximately half of the participants spent 1–9min in oral health consultation with their patients. Only about 2% of participants spend less than 1min in the oral health consultation. Most community pharmacists in both Kuala Lumpur and Selangor do not refer to any references or guidelines when providing oral health advice (87.9%). For those who did refer to references or guidelines, the most commonly used references were MIMs and Micromedex. Most of the participants (60%) believed that health consumers were receptive to receiving oral health-care advice.

Table 2.

Oral health services provided by community pharmacist in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor (n = 206)

| Oral health services | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Provide over-the-counter (OTC) treatments for oral health presentations | 193 (93.7) |

| Refer consumers to dental or medical practitioners when appropriate | 170 (82.5) |

| Identify signs and symptoms of oral health problems in patients | 159 (77.2) |

| Provide guidance and counseling for the treatment and prevention of oral health issues | 133 (64.6) |

| Opportunistically discuss oral health care with patients where appropriate | 75 (36.4) |

| Provide oral health-care-related written information for patients | 56 (27.2) |

| Follow up with patients regarding previous oral health-care enquiries/consultations | 43 (20.9) |

| Brief clinical examination of the patient’s oral cavity | 42 (20.4) |

| Hold oral health promotion activities to provide education and raise awareness of issues relevant to oral health | 22 (10.7) |

Table 3.

OTC products stocked in community pharmacy

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Not sure (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dental hygiene products, for example, toothbrushes, fluoride toothpaste, floss, and interdental brushes | 206 (100) | – | – |

| Natural-based dental hygiene products, for example, teatree/manuka/propolis toothpastes, and sprays | 164 (79.6) | 38 (18.4) | 4 (1.9) |

| Sensitive teeth toothpastes | 206 (100) | – | – |

| Teeth-whitening products | 183 (88.8) | 23 (11.2) | – |

| High fluoride oral care products, for example, Colgate Neutrafluor 5000 toothpaste 29 (14.1) | 55 (26.7) | 122 (59.2) | |

| Alcohol-based antibacterial/plaque mouthrinses | 187 (90.8) | 15 (7.3) | 4 (1.9) |

| Alcohol-free antibacterial/plaque mouthrinses | 203 (98.5) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5) |

| Chlorhexidine containing mouth products (gels/mouth rinses) | 198 (96.1) | 6 (2.9) | 2 (1) |

| Fluoride-based mouth-rinses | 110 (53.4) | 65 (31.6) | 31 (15) |

| Recaldent® (CPP-ACP)-based products | 8 (3.9) | 140 (68) | 58 (28.2) |

| Dry mouth products | 128 (62.1) | 70 (34) | 8 (3.9) |

| Sugar-free confectionary and gum | 143 (69.4) | 55 (26.7) | 8 (3.9) |

| Orthodontic wax | 37 (18) | 149 (72.3) | 20 (9.7) |

| Denture adhesive products | 190 (92.2) | 14 (6.8) | 2 (1) |

| Denture cleansers | 197 (95.6) | 8 (3.9) | 1 (0.5) |

| OTC products for toothache/oral-related pain | 203 (98.5) | 3 (1.5) | – |

| OTC products for mouth ulcers/sores | 203 (98.5) | 2 (1) | 1 (0.5) |

| OTC products for oral thrush | 164 (79.6) | 37 (18) | 5 (2.4) |

| Dentafix filling repair and cap repair products | 17 (8.3) | 180 (87.4) | 9 (4.4) |

| Dentist in a Box® dental emergency kits | 9 (4.4) | 190 (92.2) | 7 (3.4) |

| Other | 3 (1.5) | 180 (87.4) | 23 (11.2) |

Figure 1.

Age groups that have consulted community pharmacist relating to oral health

Table 4.

Consultation time, reference, and acceptability to receiving oral health advice from community pharmacist

| Frequency (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Consultation time | <1 min | 4 (1.9) |

| 1–3 min | 108 (52.4) | |

| 3–5 min | 79 (38.3) | |

| >5 min | 15 (7.3) | |

| Follow or refer to any resources or guidelines | No | 181 (87.9) |

| Yes | 25 (12.1) | |

| Acceptability | Always | 21 (10.2) |

| Most of the time | 120 (58.3) | |

| Sometimes | 58 (28.2) | |

| Hardly every | 3 (1.5) | |

| Unsure | 4 (1.9) |

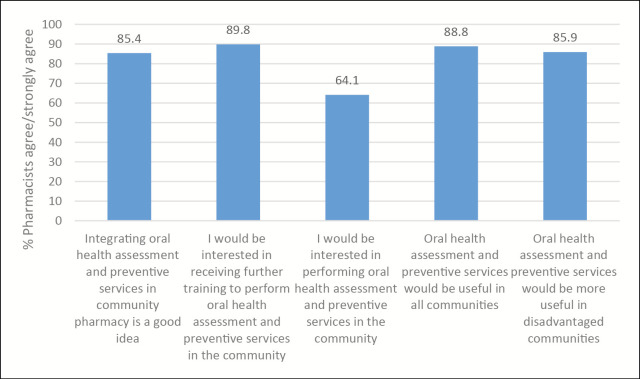

The pharmacists were asked about the opinions regarding different aspects of pharmacy practice in oral health care using a 5-point rating Likert scale [Table 5]. Nearly all pharmacists strongly agreed or agreed (95%) that they would be interested in receiving further training to better identify/diagnose oral health issues and make appropriate evidence-based product recommendations for their patients and they had an important role to play in promoting oral health care in the community. Majority of the pharmacists strongly agreed or agreed (88%) that they would be interested in working collaboratively with other health-care professionals in the local area to support better oral health for the community and identifying/diagnosing oral health issues and making appropriate evidence-based product recommendations was part of their professional responsibility. Figure 2 represents community pharmacists’ interest regarding incorporating prevention, early intervention, and referral to oral health-care services within community pharmacies. This includes but is not limited to performing oral health services such as dental cavity risk assessments, screening, and dental practitioner referral programs, fluoride varnish application, providing smoking cessation, and patient education or guidance to promote and maintain good oral health. The participants showed an overall positive response to these services and most of them supported integrating oral health services into the community pharmacy. However, only around 60% of them would be interested in performing oral health assessment and preventive services in the community.

Table 5.

Pharmacist opinions regarding different aspects of pharmacy practice in oral health care

| Strongly agree (%) | Agree (%) | Neither agree or disagree (%) | Disagree (%) | Strongly disagree (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pharmacists have an important role to play in promoting oral health care in the community | 52 (25.2) | 138 (67.0) | 14 (6.8) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| I am comfortable looking inside a patient’s mouth to identity/ diagnose oral health issues | 15 (7.3) | 95 (46.1) | 70 (34.0) | 24 (11.7) | 2 (1.0) |

| Identifying/diagnosing oral health issues and making appropriate evidence-based product recommendations is part of my professional responsibility | 40 (19.4) | 122 (59.2) | 37 (18.0) | 7 (3.4) | 0 (0) |

| I would be interested in receiving further training to better identify/diagnose oral health issues and make appropriate evidence-based product recommendations for my patients | 62 (30.1) | 133 (64.6) | 9 (4.4) | 2 (1.0) | 0 (0) |

| Offering oral health care programs/services in pharmacies is a good use of time and money | 28 (13.6) | 113 (28.2) | 58 (28.2) | 7 (3.4) | 0 (0) |

| I would be interested in working collaboratively with other health-care professionals in the local area to support better oral health for the community | 49 (23.8) | 134 (65.0) | 20 (9.7) | 3 (1.5) | 0 (0) |

Figure 2.

Pharmacist attitudes toward the provision of oral health assessment and preventive services

In addition, the pharmacists were asked regarding the factors that they feel would improve the ability of pharmacies to better promote oral health care in Malaysia [Table 6]. The majority of the participants felt that further training for pharmacists would improve the ability of Malaysia’s pharmacies to better promote oral health care (85%). Moreover, they were asked about their preferred format to receive training. Most of the pharmacists preferred face to face (79.6%) and the online format to receive training on how to identify/diagnose and manage oral health problems (70.4%). Participants also preferred face-to-face and online format to receive training on providing oral health assessment and preventive services (169 [82.0%]; 138 [67.0%]). Most pharmacists believed that oral health knowledge/training would be best delivered during continuing professional development (CPD) followed by within their undergraduate degree (170 [82.5%] and 142 [68.9%], respectively).

Table 6.

Factors that would improve the ability of pharmacies to promote better oral health in Malaysia

| Frequency (%) | |

|---|---|

| Further training for pharmacists | 175 (85.0) |

| Pharmacy-specific practice guidelines, decision support pathways, information, and educational resources for oral health promotion/management of oral health issues | 168 (81.6) |

| Private counseling/consultation to support oral health-care roles in pharmacy | 127 (61.7) |

| Further training for pharmacy assistants | 122 (59.2) |

| Payment for provision of additional oral health assessment and preventive services in my pharmacy | 82 (39.8) |

| Extra staff to provide appropriate advice, counseling, and support to assist customers | 79 (38.3) |

| Payment for providing oral health advice | 70 (34.0) |

| Other | 6 (2.9) |

DISCUSSION

The findings showed that around 70% of the participants provided up to five oral health consultations and OTC products recommendation regarding oral health each week, 10% lesser as compared with the study conducted by Christopher et al.[10] Most of the community pharmacists (193 of 206) who responded to the questionnaire provided OTC treatments for oral health presentations. Almost all oral health products that were listed in the questionnaire were stocked in the community pharmacies across Kuala Lumpur and Selangor except high-fluoride oral care products, Recaldent®, orthodontic wax, Dentafix filling repair, and Dentist in a Box® dental emergency kit. The reason less than half of the pharmacies stocked these five products is not entirely known. It could be because of low demand from the public or the need for more specific professional advice or skills on the usage of such products.[13]

According to the report of Malaysia Health Systems Research (MHSR), there is a growing trend toward excessive spending on secondary and tertiary care relative to primary care by the public, which likely contributes to higher costs and worse health outcome.[14] The results indicated that more than half of the participants referred the consumer to dental or medical practitioners when appropriate and identify signs and symptoms of oral health problems in patients. Majority of the participants believed that health consumers were receptive toward oral health advice given. The previous findings showed that community pharmacists in Malaysia offer a trusted environment as a potential oral health-care resource and can be expected to take on more responsibilities as oral health-care providers.[15] Generally, the high cost of dental treatments can be avoided by effective prevention and oral health promotion measures.[1,16] This study indicated that less than half of the participants offered oral health promotion activities to provide education and raise awareness of issues relevant to oral health. This may attributed to the lack of knowledge or training in the oral health-care field, lack of staff training resources, and lack of oral and dental health educational promotion materials for consumers which were barriers reported by the participants to furthering their role in oral health care. This is not surprising as only 12% of pharmacists referred to references or guidelines which is lower compared to pharmacists in Australia (15.8%) due to the lack of pharmacy-specific practice guidelines regarding oral health in Malaysia.[10]

Majority of the participants viewed positively of integrating oral health assessment and preventive services in the community pharmacies. Despite having a lower prevalence of dental caries among children of age five than those in Malaysia’s neighboring countries, caries prevalence and DMFT status for Malaysian adults aged 35–44 years and teenagers are higher than that of in Singapore and Thailand. [The DMFT Index is the sum total of the number of teeth decayed (D), missing/extracted (M), or filled (F)].[17] Therefore, there is a need for oral health assessment and preventive services within the community pharmacies to improve the oral health outcome of the community and reduce the burden associated with the high cost of dental treatments.

The most commonly reported oral health condition that the pharmacists were confident in identifying signs or symptoms of mouth ulcer, oral thrush, and poor general oral hygiene practices. Of 25 oral health conditions, only less than half of the pharmacists were confident in identifying 14 of the conditions, this finding was consistent with a previous study.[10] This could be due to the lack of pharmacy-specific guidelines to refer to as mentioned, leading to lesser confidence to advice on different diseases related to oral health care. The other reasons that majority of the pharmacists were confident in only a few oral health conditions could be the lack of knowledge or training in this field which was reported as the highest perceived barriers to furthering their role in oral health care. A study conducted to assess Malaysia pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitude and practice toward oral health revealed that there was lack of oral health knowledge among the pharmacy students, indicating that oral health should be given emphasis in the pharmacy undergraduate curricula.[12] A practical approach to this would be forming an interprofessional partnership with dental associations to develop pharmacy-specific evidence-based guidance on oral health-care topics and enhance the pharmacy undergraduate curricula by emphasizing on oral health topics. This is in concert with the belief of the Ministry of Health Malaysia which recognizes that the health of Malaysians can only be improved through the interprofessional collaborations of all health professions.[6] Pharmacists would then be better equipped to provide oral health services in the community pharmacies.

Most of the pharmacists in this study preferred the face-to-face or online training during CPD followed by training within their undergraduate degree or studies. This presents an opportunity for Malaysian pharmacy professional bodies to form collaborative partnerships with Malaysian dental associations/schools to develop evidence-based CPD programs in oral health care tailored for community pharmacists. This study also shows that the scope of oral health in pharmacy curricula could be expanded through this interprofessional collaboration to further equip the pharmacy students with sufficient knowledge to be able to deal with oral health inquiries confidently in their profession. Early exposure of pharmacy students to collaborative practices through interprofessional education experiences enhances the awareness of the role of the dentist, further improving patients’ outcome.[4]

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS

This study is considered the first (to the best of our knowledge) national study evaluating the belief, practices, and attitudes of community pharmacists toward dental care. Our study targeted pharmacists practicing in many areas in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor, which provides a representative sample and ensures the generalizability of our finding. However, some researchers have voiced their concern over the applicability of such surveys; they remain an interesting tool that offers accurate information about belief, attitude, and practice that can be used for educational purposes

The study has few limitations; the sampling method that is vulnerable to selection bias and influences beyond the control of the researcher. In addition, the number was not sufficient to conduct further biostatistical analysis. This is due to the limited time of the data collection, which may potentially limit the generalizability of the findings. However, the sample size obtained in this study allowed us to capture a range of Malaysian pharmacist and pharmacy assistant descriptive responses. Finally, it may be self-reported and subject to respondent recall and social desirability bias.

CONCLUSIONS

Community pharmacists across Kuala Lumpur and Selangor states do already provide some degree of oral health services and they expressed a positive attitude to gain further their knowledge in this field through training to further improve the ability of pharmacies to provide better oral health-care in Malaysia. In addition, this study provides evidence for the need of an interprofessional partnership between the Malaysian pharmacy professional bodies with Malaysian dental associations to develop, implement, expand, and evaluate evidence-based resources, guidelines, the scope of oral health in pharmacy curricula, and services to deliver improved oral health care within all Malaysian communities. Community pharmacists are expected to take on more responsibilities as oral health-care providers.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was approved and funded (covering the cost of research materials and traveling only) by the School of Pharmacy, Monash University Malaysia under the BPharm program (Summer Project Fund).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization. Oral health. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2018. [Last accessed on 2019 Feb 7]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taiwo OO, Panas R. Roles of community pharmacists in improving oral health awareness in Plateau State, Northern Nigeria. Int Dent J. 2018;68:287–4. doi: 10.1111/idj.12383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Institute for Public Health (IPH) National Health and Morbidity Survey 2015 (NHMS 2015) Vol II: Non-communicable diseases, risk factors & other health problems. Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lygre H, Kjome RLS, Choi H, Stewart AL. Dental providers and pharmacists: A call for enhanced interprofessional collaboration. Int Dent J. 2017;67:329–31. doi: 10.1111/idj.12304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Muirhead VE, Quayyum Z, Markey D, Weston-Price S, Kimber A, Rouse W, et al. Children’s toothache is becoming everybody’s business: Where do parents go when their children have oral pain in London, England? A cross-sectional analysis. BMJ Open. 2018;8:e020771. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oral Health Division. National oral health plan for Malaysia 2011–2020. Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson S. Community pharmacy and public health in Great Britain, 1936 to 2006: how a phoenix rose from the ashes. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:844–8. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.055442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joyce AW, Sunderland VB, Burrows S, McManus A, Howat P, Maycock B. Community pharmacy’s role in promoting healthy behaviours. J Res Pharm Pract. 2007;37:42–4. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pharmaceutical Services Division-Ministry of Health Malaysia. A National Survey on the Use of Medicines (NSUM) by Malaysian consumers. Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Freeman CR, Abdullah N, Ford PJ, Taing M-W. A national survey exploring oral healthcare service provision across Australian community pharmacies. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e017940. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mann RS, Marcenes W, Gillam DG. Is there a role for community pharmacists in promoting oral health? Br Dent J. 2015;218:E10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2015.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rajiah K, Ving CJ. An assessment of pharmacy students’ knowledge, attitude, and practice toward oral health: An exploratory study. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2014;4:S56–62. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.144601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dealing with dental disasters: A guide for community pharmacists. Pharm J. 2007;278:561–2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ministry of Health Malaysia and Harvard T.H. Chan. Malaysia Health Systems Research––Volume I: Contextual analysis of the Malaysian health system. Malaysia: Ministry of Health; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maunder PEV, Landes DP. An evaluation of the role played by community pharmacies in oral healthcare situated in a primary care trust in the north of England. Br Dent J. 2005;199:219. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4812614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suga USG, Terada RSS, Ubaldini ALM, Fujimaki M, Pascotto RC, Batilana AP, et al. Factors that drive dentists towards or away from dental caries preventive measures: Systematic review and metasummary. PLoS One. 2014;9:e107831. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0107831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jaafar S, Noh KM, Muttalib K, Othman NH, Healy J, Maskon K, et al. Malaysia health system review. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2013. p. 3. [Google Scholar]