Abstract

Background.

Minimizing emergency department (ED) use is a common goal of emerging population health initiatives. Our objective was to assess the impact of chronic conditions on children’s ED use.

Methods.

Retrospective analysis of 1,850,027 ED visits in 2010 by 3,250,383 children ages 1-21 years continuously enrolled in Medicaid from 10 states included in the Truven Marketscan Medicaid Database. The main outcome was the annual ED visit rate not resulting in hospitalization per 1,000 enrollees. We compared rates by enrollees’ characteristics, including type and number of chronic conditions, and medical technology (e.g., gastrostomy, tracheostomy), using Poisson regression. To assess chronic conditions, we used AHRQ’s Chronic Condition Indicator system, assigning chronic conditions with ED visit rates ≥75th percentile as having the “highest” visit rates.

Results.

The overall annual ED visit rate was 569 per 1000 enrollees. As the number of the children’s chronic conditions increased from 0 to ≥3, visit rates increased by 180% (from 376 to 1053 per 1000 enrollees, p<0.001). Rates were 174% higher in children assisted with vs. without medical technology (1546 vs. 565, p<0.001). Sickle cell anemia, epilepsy, and asthma were among the chronic conditions associated with the highest ED visit rates (all ≥1003 per 1000 enrollees).

Conclusions.

The highest ED visit rates resulting in discharge to home occurred in children with multiple chronic conditions, technology assistance, and specific conditions such as sickle cell anemia. Future studies should assess the preventability of ED visits in these populations and identify opportunities for reducing their ED use.

Keywords: Medicaid, emergency department, chronic conditions

Introduction

Health systems are striving to optimize health, improve patient experience, and reduce health care related costs of their populations served.(1) Minimizing unnecessary healthcare use has become a focal point across efforts to achieve these goals, especially for patients with chronic conditions that are associated with high resource use.(2) Increasingly targeted for reduction in these efforts are emergency department (ED) visits for health problems that may have either been avoided entirely or effectively managed in other outpatient or community settings that offer urgent care health services.(3-6)

Patients using Medicaid are a particular focus of state and federal health system initiatives to reduce ED use.(7-9) In prior studies, adult patients with Medicaid use the ED at a rate that is twice as high as privately insured individuals.(10) Medicaid beneficiaries tend to be in poorer health; have a higher prevalence of disability and chronic health problems; have more unmet healthcare needs, and more often lack access to preventive and disease management health services.(11) In adults using Medicaid, the highest ED users have mental health and substance abuse problems.(12-14)

Similar to adults, children using Medicaid visit the ED more frequently than children who are privately insured;(15) children using Medicaid also tend to have substandard access to high quality outpatient care and often have more unmet healthcare needs. For some of these children, ED use may be particularly high.(7, 8) For example, nearly one-third of children using Medicaid who have an uncommon, complex chronic condition (e.g., sickle cell disease) annually visit the ED at least once.(16) On a population level, however, it remains unknown which chronic conditions experienced by children using Medicaid account for the greatest number of ED visits, especially visits resulting in discharge to home. In contrast to adults with Medicaid, mental health and substance abuse problems may not be the explanatory conditions in children. Thus, the objectives of this study are to (1) assess variation in ED visit rates across chronic conditions experienced by children in Medicaid; and (2) distinguish which chronic conditions are associated with the highest ED use for such visits.

Methods

Study Design, Patients, and Setting.

This retrospective cohort study included visits by children 0-21 years of age who were continuously enrolled in Medicaid programs from 10 U.S. states for at least 11 of 12 months between 1/1/2010-12/31/2010. Data were obtained from the Truven MarketScan Medicaid claims dataset (Truven Analytics, Ann Arbor, MI). In the dataset, Medicaid eligibility is reported by family income or presence of a disability. Children are followed longitudinally across healthcare encounters using a unique identifier. Although the Truven data usage agreement precludes publicly revealing participating states, all geographic regions of the U.S. are represented. The Institutional Review Board at Boston Children’s Hospital declared this study exempt from review.

Main Outcome Measures.

To assess which chronic conditions are associated with the highest ED use, we measured and report two annual outcomes: (1) ED visit rate, calculated as the total number of ED visits resulting in discharge to home per 1000 enrolee years and (2) the total number of annual ED visits. The reason for each ED visit was categorized using the ED Diagnosis Grouping System based on primary International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9) code to allow for clinically sensible groupings of diagnoses.(17)

When measuring ED use, only ED visits resulting in discharge to home (i.e., visits not resulting in hospital admission) were included. Visits resulting in admission were not measured because they are variably documented across states because payment is not made for an ED visit claim on the same day as hospital admission. Consequently, data about these ED visits are not recorded in the Truven database. Prior studies of ED use in children report that 3-7% of all ED visits result in hospital admission; these percentages could be higher in children with chronic conditions.(18)

We assessed both the visit rate and count because some children with a rare, complex chronic condition (e.g., leukodystrophy) may have a high ED visit rate but a low total count due to a small population size. Alternatively, some children with a common condition (e.g., asthma) might have a lower ED visit rate but a high total count because of their larger population size. We defined the highest ED visit rates and counts as those that were in the ≥75th percentile of the distributions.(19)

Assessment of Chronic Condition Type and Number.

We used the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)’s open-source, publicly-available diagnosis classification scheme - the Chronic Condition Indicator and Clinical Classification System – to assess the type and number of chronic conditions experienced by each child enrolled in Medicaid.(19-23) Used previously to asses chronic conditions in children(19, 22, 24) and with their Medicaid data(16, 23), the Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) component of the AHRQ scheme classifies ~14,000 ICD9 diagnosis codes as chronic or not chronic. The scheme defines a chronic condition as a condition that lasts 12 months or longer and meets one or both of the following criteria: (a) it places limitations on self-care, independent living, and social interactions; and (b) it results in the need for ongoing intervention with medical products, services, and special equipment.

The multi-level Clinical Classification System (CCS) component of the scheme groups the chronic ICD9 codes identified from the CCI into a clinically comprehensive, mutually exclusive set of chronic conditions. For the purposes of the present study, we assessed specific chronic conditions occurring in at least 50 children in the dataset. We also did not assess or count chronic conditions identified by the system that some clinicians may not consider a true chronic condition (e.g., myopia and other vision problems). All ICD9 codes recorded for each child across every healthcare encounter during the study period were used to assess the presence of chronic conditions.

Children with a chronic condition were further classified as having a complex chronic condition (CCC) using a previously described classification scheme.(25) CCCs represent defined diagnosis groupings expected to last longer than 12 months, and involve either a single organ system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and hospitalization, or multiple organ systems.(26, 27) We also assessed children assisted with medical technology, identified with ICD9 codes indicating the use of a medical device to manage and treat a chronic illness (e.g., ventricular shunt to treat hydrocephalus) or to maintain basic body functions necessary for sustaining life (e.g. a tracheostomy tube for breathing).(28, 29)

Demographic Characteristics.

Demographic characteristics assessed were age in years at the beginning of the study period, race/ethnicity (i.e. non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, and other), and reason for enrollment in Medicaid (i.e. disability vs. other).

Statistical Analysis.

Descriptively, ED visit rates are presented as the number of ED visits per 1,000 enrollee years. For each visit rate presented, the denominator (i.e., enrollee years) is specific to the subpopulation clarified in the presentation (e.g., ED visit rates for children with asthma = number of ED visits for children with asthma divided by 1000 enrollees with asthma). In bivariable analysis, we used chi square tests and Poisson regression to assess the relationship between the ED visit rate and experiencing ≥1 ED visits and ≥2 ED visits respectively, with the children’s demographic and clinical characteristics.

We then assessed which of the children’s chronic conditions were associated with the highest ED use (i.e., the highest quartile of both ED visit rate and count). To do this, we plotted, by chronic condition, the children’s ED visit rates against their total number of ED visits. The number of ED visits was log-transformed to make the data more easily visualized across different points of the distribution. Separate plots were generated for children with single vs. multiple chronic conditions. The statistical threshold was set at p<0.05 for all analyses. All analyses were performed with Statistical Analysis Software (Cary, NC) v 9.2.

Results

Study Population.

Among 3,250,383 children in the study there were 1,850,027 ED visits resulting in discharge to home. The median age was 9 years [interquartile range (IQR), 4-14]; 50.5% were male, 48.2% were non-Hispanic white, and 4.2% were enrolled in Medicaid because of a disability (Table 1). Fifty-three percent of children had at least one chronic condition; with 27.3% having multiple chronic conditions. Six percent of children had a complex chronic condition and 0.4% were assisted with medical technology. The most common diagnosis groups for ED visits were ear, nose, mouth and throat infections (20.8%), fever (5.4%), and lower respiratory infections (5.3%).

Table 1.

Emergency Department Visit Rates Resulting in Discharge to Home in Children with Medicaid by Chronic Condition and Other Patient Characteristics

| Characteristics | N (%) | ED Use Not Resulting in Hospital Admission |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % with 1 visits1,2 |

% with ≥2 visits1,2 |

Visit rate1,2 |

||

| Overall cohort | 3250383 | 19.3% | 13.0% | 569 |

| Number of Chronic Conditions | ||||

| 0 | 1532215 (47.1) | 16.6% | 8.1% | 376 |

| 1 | 830046 (25.5) | 20.5% | 13.2% | 572 |

| 2 | 422671 (13.0) | 22.2% | 17.5% | 733 |

| 3+ | 465451 (14.3) | 23.4% | 24.6% | 1053 |

| Complex Chronic Condition | ||||

| No | 3044345 (93.7) | 19.1% | 12.3% | 538 |

| Yes | 206038 (6.3) | 22.6% | 23.8% | 1019 |

| Technology Assistance | ||||

| No | 3236111 (99.6) | 19.3% | 12.9% | 565 |

| Yes | 14272 (0.4) | 24.6% | 35.2% | 1546 |

| Age at the Beginning of the Study Period | ||||

| 1-4 years | 874086 (26.9) | 23.2% | 20.9% | 857 |

| 5-12 years | 1398077 (43.0) | 17.9% | 8.9% | 414 |

| 13-17 years | 677609 (20.8) | 17.2% | 9.2% | 427 |

| 18-21 years | 300611 (9.2) | 19.3% | 17.3% | 772 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1640109 (50.5) | 19.7% | 12.9% | 562 |

| Female | 1610274 (49.5) | 18.9% | 13.1% | 576 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| White | 1568127 (48.2) | 19.6% | 13.5% | 591 |

| Black | 1005299 (30.9) | 20.7% | 14.1% | 610 |

| Hispanic | 310761 (9.6) | 16.2% | 9.4% | 418 |

| Other | 366196 (11.3) | 16.8% | 11.0% | 492 |

| Reason for Enrollment | ||||

| Blindness/disability | 137196 (4.2) | 19.3% | 12.8% | 755 |

| Other | 3113187 (95.8) | 19.5% | 16.9% | 561 |

Emergency department (ED) visit rate was calculated as the total number of annual ED visits not resulting in hospital admission per 1,000 enrollees

p <0.001 for comparison of the percentage of enrollees with 1 or ≥2 ED visits as well as ED Visit Rate across the subcategories of each characteristic

Emergency Department Visit Rates.

The annual rate of ED visits was 569 per 1000 enrollees; 32.3% of children had at least 1 ED visit; 19.3% had a single ED visit and 13.0% had multiple ED visits (Table 1). ED visit rates varied by the number and type of chronic conditions and technology assistance (p<0.001 for all). As the number of chronic conditions increased from 0 to ≥3, ED visit rates increased by 180% from 376 to 1053 visits per 1000 enrollees (p<0.001), and the percentage of children with multiple ED visits increased from 8.1% to 24.6%. The ED visit rate was 89% higher in children with vs. without a complex chronic condition (1019 vs. 538 per 1000 enrollees, p<0.001). The ED visit rate was 174% higher in children with vs. without technology assistance (1546 vs. 565 per 1000 enrollees, p<0.001).

ED visit rates also varied significantly (p<0.001) by age, race/ethnicity, and reason for enrollment. For example, the ED visit rate was 42% higher in non-Hispanic white (591 ED visits per 1000 enrollees) and 44% higher for non-Hispanic black children (610 ED visits per 1000 enrollees) than in Hispanic children (418 ED visits per 1000 enrollees). (Table 1)

Specific Chronic Conditions Associated with the Highest Emergency Department Use.

There was significant (p<0.001) variation in ED use by the specific chronic conditions experienced by the children (Figures 1 and 2). Presented below are the findings of the chronic conditions associated with the highest ED use (ED visit rate and number of visits equal to or greater than the 75 percentile).

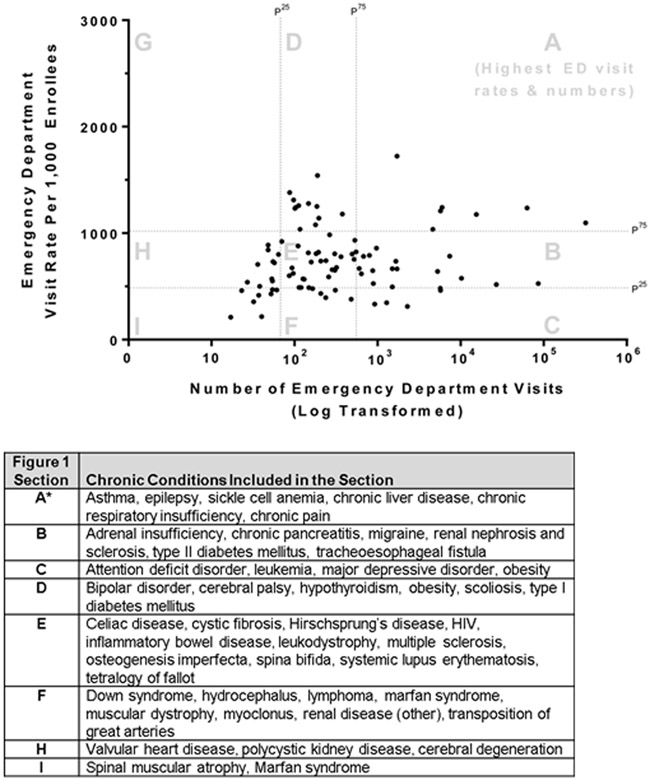

Figure 1.

Figure sections, labeled with letters A through I, are divided by the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution of annual ED visits (x-axis) and ED visit rates (y-axis). The dots in each section represent mutually exclusive groups of children distinguished by their single chronic condition. Chronic conditions included in each section are presented in the accompanying table. For ED visits, the 25th and 75th percentiles are 67 and 548 per 1000 enrollees. ED visits are presented in log-transform to produce a better visualization of the data. For annual ED visit rates, the 25th and 75th percentiles are 493 and 1003 per 1,000 enrollees

*Highest ED visit rates and numbers of the study population

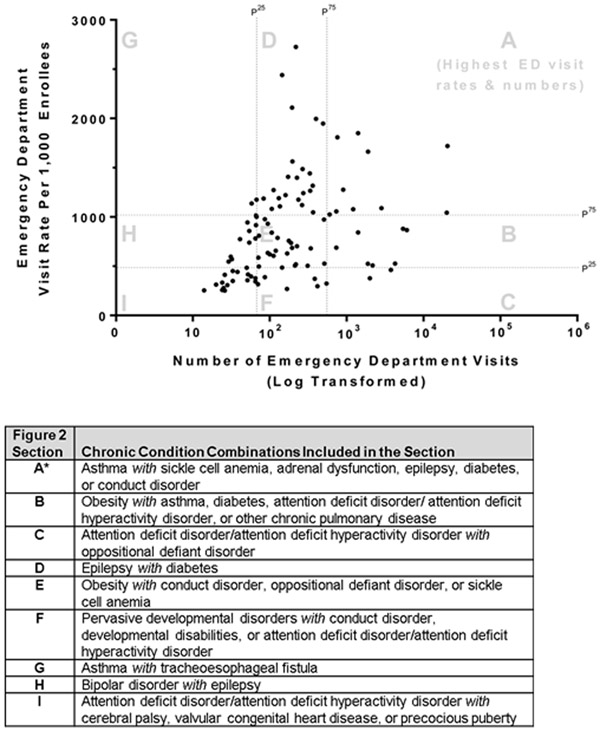

Figure 2.

Figure sections, labeled with letters A through I, are divided by the 25th and 75th percentiles of the distribution of annual ED visits (x-axis) and ED visit rates (y-axis). The dots in each section represent mutually exclusive groups of children distinguished by their profile of multiple chronic conditions. Chronic condition combinations included in each section are presented in the accompanying table. For ED visits, the 25th and 75th percentiles are 67 and 548 per 1,000 enrollees. ED visits are presented in log-transform to produce a better visualization of the data. For annual ED visit rates, the 25th and 75th percentiles are 493 and 1003 per 1,000 enrollees.

*Highest ED visit rates and numbers of the study population

Children with a Single Chronic Condition.

Children with a single chronic condition who had the highest ED use (11.3% of the total cohort, n=365,940) accounted for 22.2% of all ED visits (n=411,121) during the study year for children in Medicaid. The chronic conditions experienced by these children were asthma, epilepsy, sickle cell anemia, chronic liver disease other chronic pulmonary disease (e.g., bronchopulmonary dysplasia), or chronic pain. (Figure 1, Section A) ED visit rates for these conditions were 1115 (asthma), 1003 (epilepsy), 1125 (sickle cell anemia), 1337 (chronic liver disease), 1167 (other chronic pulmonary disease), and 1383 (chronic pain) per 1,000 enrollees.

Children with Multiple Chronic Conditions.

Children with multiple chronic conditions who had the highest ED use (0.6% of the total cohort, n=19,297) accounted for 1.6% of all ED visits (n=30,118) for children in Medicaid. There were 7 distinct groups of children, distinguished by their chronic condition profile, with the highest ED use. (Figure 2, Section A) All of the children had a chronic respiratory problem [asthma (n=5), chronic pulmonary disease (n=1), or both (n=1)] plus an additional chronic condition. ED visit rates for these children with multiple chronic conditions ranged from 1,056 per 1,000 enrollees (children with obesity and chronic respiratory disease) to 1,850 per 1,000 enrollees (children with sickle cell disease and asthma).

Discussion

This study reports new information about children in Medicaid with the highest use of the ED for visits resulting in discharge to home. The main findings suggest that children with younger age, non-Hispanic ethnicity, multiple chronic conditions, and technology assistance experienced higher ED visit rates than children without these attributes. The chronic conditions associated with the highest ED use – that is, those children with both the highest ED visit rates and the greatest number of ED visits – included asthma, epilepsy, and sickle cell anemia. Children with multiple chronic conditions who had the highest ED use had a high prevalence of chronic respiratory problems.

It is important to recognize that some children in the current study had ED visits that were equal or greater than the rates of elderly individuals, who are frequently targeted to contain ED use. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality reports nearly 500 ED visits not resulting in admission for every 1,000 individuals age ≥85 years.(30) In the present study, children with multiple chronic conditions, complex chronic conditions, and technology assistance had ED visit rates that were two-to-three times higher (i.e., 1,000-1,500 per 1,000 patients). Aside from the tenuous health status experienced by many of these children, there are other, modifiable reasons that might help explain their high ED use. For example, an emerging body of literature suggests that many of children with these attributes do not have sufficient primary care clinicians equipped to provide urgent care for them.(31, 32) Many of these children do not visit with a primary care provider annually, do not have a usual source of care, and do not have a healthcare provider taking charge of their care.(31, 33-38) Further investigation is warranted to assess whether primary care of this nature is associated with increased reliance on the ED for first-contact, acute care for these children.

Although reducing ED use in children with medical complexity (i.e., those with multiple chronic conditions, technology assistance, etc.) is increasingly declared a core goal of state and federal health system improvement efforts(39, 40), it is important to recognize that children without a chronic condition as well as children with asthma only (i.e., no other chronic conditions) accounted for nearly one-half of the total number of ED visits among all children with Medicaid. These findings are congruent with prior studies reporting that ED visits not resulting in admission occur most frequently for children without a chronic condition or children with a “less complex” chronic condition, such as asthma.(15) Subsequent investigation is needed to assess the feasibility and effectiveness of population health initiatives striving to contain ED use in these “healthier” children compared to those with medical complexity. For children with asthma, straightforward initiatives involving enhanced asthma education have decreased ED visits.(41) For children with medical complexity, initiatives that decrease ED visits appear to be more time consuming and effort intense, with complicated care coordination and collaboration across primary care, specialty care, and other outpatient and community health services (e.g., home care programs for children with tracheostomy).(42, 43) For some children with medical complexity (e.g., those with a medical technology malfunction), the ED may have been the only care setting equipped with the diagnostic testing, therapeutics, health monitoring, and specialty consultation required to promptly address the problem and prevent hospitalization.

Should there be interest, on the population level, in further exploration of optimizing ED use in children with complex chronic conditions, then children with sickle cell anemia could be an important focus.(44) For children with sickle cell anemia, vaso-occlusive episodes and pain – the leading causes of their ED visits(45) – are known to be reduced with consistent use of hydroxyurea.(46) However, some studies suggest the vast majority of children from low-income families are not regularly using hydroxyurea.(47) In children with Medicaid, efforts to improve hydroxyurea use in children with sickle cell anemia might have a substantial population effect on ED visits.(47) Also, day treatment programs in children with sickle cell are an emerging safe and effective alternative to ED care for acute management of pain crises.(48, 49) Perhaps these programs, where available, might benefit children with sickle cell anemia who use Medicaid.

The present study has several caveats and limitations. Although we assessed chronic conditions across all healthcare claims (i.e. outpatient primary and specialty care visits, ED, etc.) clinical data (e.g., from chart review) might be preferable to identify chronic conditions in children. It is possible that some children classified without a chronic condition could have had one even if their chronic condition was not coded during any health services encounter across the care continuum during the study period. The present study is not positioned to assess which ED visits were preventable. The database does not contain clinical information about patients’ physiologic status or treatments used in the ED. The specific U.S. states in the Truven database have not been disclosed. Children with less continuous enrollment patterns may have different ED use than those more continuously enrolled. Therefore, the study findings may or may not generalize to all child Medicaid beneficiaries; there are approximately 12 million ED visits annually for children using Medicaid.(18) Moreover, although up to 65% of children in the U.S. are insured by Medicaid(50), the findings may not generalize further to the remainder of children who use private insurance. Additionally, because children are assigned their own unique identifiers in the year after their birth, we were unable to include children less than one year old in the study. When compared with older children, infants have been shown to have different patterns of resource utilization in the ED.(51) Finally, the administrative data were neither equipped to assess the time of day for the ED visits nor to assess families’ understanding of the best way to engage the health system for urgent care during and after daytime office hours; this understanding might be limited for some families of children using Medicaid.

Despite these limitations, this study may help to inform population health initiatives that strive to optimize ED use in children with Medicaid. For example, state Medicaid programs could replicate the methods for their own enrollees, cross-referencing the number of ED visits with the ED visit rate to (1) identify which children use the ED the most; (2) explore opportunities that might optimize outpatient and community acute care for those children; and (3) measure, longitudinally, the impact of the efforts on the children’s ED use. A state program could also use the results from the present study to case-mix adjust, benchmark, and compare ED use of specific populations of children from their state (e.g., children with sickle cell anemia or epilepsy) with our broader cohort. Future ED research and quality improvement endeavors may wish to assess the most appropriate settings for first-contact, acute care for important subpopulations of children with the greatest ED impact (e.g., those without a chronic condition or those with asthma, epilepsy, or sickle cell anemia).

Conclusions

In this multi-state, retrospective study of children using Medicaid, the highest ED visit rates resulting in discharge to home occurred in children with multiple chronic conditions, technology assistance, and specific conditions, such as sickle cell anemia. Future studies should assess the true reasons for, the treatment administered during, and the preventability of such ED visits in these populations and identify opportunities for reducing their ED use.

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: Dr. Berry was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (R21 HS023092-01). Dr. Freedman was supported by the Alberta Children Hospital Foundation Professorship in Child Health and Wellness. Dr. Cohen was supported as the 2015/2016 Commonwealth Fund Harkness/Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement Fellow in Health Care Policy and Practice. The funders, their directors, officers and staff were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or in the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Abbreviations:

- ED

Emergency Department

- IQR

Interquartile range

- AHRQ

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality

- CCI

Chronic Condition Indicator

- CCS

Clinical Classification Software

- CCC

Complex Chronic Condition

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Berry had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References

- 1.Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:759–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whittington JW, Nolan K, Lewis N, Torres T. Pursuing the Triple Aim: The First 7 Years. Milbank Q. 2015;93:263–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mann C Reducing Nonurgent Use of Emergency Departments and Improving Appropriate Care in Appropriate Settings. Baltimore: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinick RM, Burns RM, Mehrotra A. Many emergency department visits could be managed at urgent care centers and retail clinics. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29:1630–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal S, Conway PH. Aligning emergency care with the triple aim: Opportunities and future directions after healthcare reform. Healthc (Amst). 2014;2:184–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montalbano A, Rodean J, Kangas J, Lee B, Hall M. Urgent Care and Emergency Department Visits in the Pediatric Medicaid Population. Pediatrics. 2016; 137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brousseau DC, Gorelick MH, Hoffmann RG, Flores G, Nattinger AB. Primary care quality and subsequent emergency department utilization for children in Wisconsin Medicaid. Acad Pediatr. 2009;9:33–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brousseau DC, Hoffmann RG, Nattinger AB, Flores G, Zhang Y, Gorelick M. Quality of primary care and subsequent pediatric emergency department utilization. Pediatrics. 2007;119:1131–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lochner KA, Goodman RA, Posner S, Parekh A. Multiple chronic conditions among Medicare beneficiaries: state-level variations in prevalence, utilization, and cost, 2011. Medicare Medicaid Res Rev. 2011;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Revisiting Emergency Department Use in Medicaid. Washington D.C.: Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sommers AS, Boukus ER, Carrier E. Dispelling myths about emergency department use: majority of Medicaid visits are for urgent or more serious symptoms. Res Brief. 2012(23):1–10, 1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu SW, Nagurney JT, Chang Y, Parry BA, Smulowitz P, Atlas SJ. Frequent ED users: are most visits for mental health, alcohol, and drug-related complaints? Am J Emerg Med. 2013;31(10):1512–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norman C, Mello M, Choi B. Identifying Frequent Users of an Urban Emergency Medical Service Using Descriptive Statistics and Regression Analyses. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(1):39–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vinton DT, Capp R, Rooks SP, Abbott JT, Ginde AA. Frequent users of US emergency departments: characteristics and opportunities for intervention. Emerg Med J. 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neuman MI, Alpern ER, Hall M, Kharbanda AB, Shah SS, Freedman SB, et al. Characteristics of recurrent utilization in pediatric emergency departments. Pediatrics. 2014;134(4):e1025–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry JG, Hall M, Neff J, Goodman D, Cohen E, Agrawal R, et al. Children with medical complexity and Medicaid: spending and cost savings. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(12):2199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alessandrini EA, Alpern ER, Chamberlain JM, Shea JA, Gorelick MH. A new diagnosis grouping system for child emergency department visits. Acad Emerg Med. 2010;17(2):204–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Weiss AJ, Wier LM, Stocks C, Blanchard J. Overview of Emergency Department Visits in the United States, 2011: Statistical Brief #174. 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Peltz A, Hall M, Rubin DM, Mandl KD, Neff J, Brittan M, et al. Hospital Utilization Among Children With the Highest Annual Inpatient Cost. Pediatrics. 2016;137:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) for ICD-9-CM Rockville, MD: 2011. [cited 2013 April 29]. Available from: http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/chronic/chronic.jsp. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Friedman B, Jiang HJ, Elixhauser A, Segal A. Hospital inpatient costs for adults with multiple chronic conditions. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63:327–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Berry JG, Hall M, Dumas H, Simpser E, Whitford K, Wilson KM, et al. Pediatric Hospital Discharges to Home Health and Postacute Facility Care: A National Study. JAMA Pediatr. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kuo DZ, Hall M, Agrawal R, Cohen E, Feudtner C, Goodman DM, et al. Comparison of Health Care Spending and Utilization Among Children With Medicaid Insurance. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1521–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, Jha AK, Nakamura MM, Klein DJ, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309:372–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Zhong W, Hall M, Dai D. Pediatric complex chronic conditions classification system version 2: updated for ICD-10 and complex medical technology dependence and transplantation. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Berry JG, Hall DE, Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Feudtner C, et al. Hospital utilization and characteristics of patients experiencing recurrent readmissions within children’s hospitals. Jama. 2011;305:682–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric deaths attributable to complex chronic conditions: a population-based study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000;106:205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Palfrey JS, Walker DK, Haynie M, Singer JD, Porter S, Bushey B, et al. Technology’s children: report of a statewide census of children dependent on medical supports. Pediatrics. 1991;87:611–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feudtner C, Villareale NL, Morray B, Sharp V, Hays RM, Neff JM. Technology-dependency among patients discharged from a children’s hospital: a retrospective cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2005;5:8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Skinner HG, Blanchard J, Elixhauser A. Trends in Emergency Department Visits, 2006–2011: Statistical Brief #179. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Statistical Briefs; Rockville (MD)2006. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berry JG, Agrawal RK, Cohen E, Kuo DZ. The Landscape of Medical Care for Children with Medical Complexity. Alexandria, VA; Overland Park, KS: Children’s Hospital Association, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.O’Donnell R Reforming Medicaid for medically complex children. Pediatrics. 2013;131 Suppl 2:S160–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berry JG, Goldmann DA, Mandl KD, Putney H, Helm D, O’Brien J, et al. Health information management and perceptions of the quality of care for children with tracheotomy: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;11:117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuo DZ, Cohen E, Agrawal R, Berry JG, Casey PH. A national profile of caregiver challenges among more medically complex children with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165:1020–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller AR, Condin CJ, McKellin WH, Shaw N, Klassen AF, Sheps S. Continuity of care for children with complex chronic health conditions: parents’ perspectives. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin SC, Margolis B, Yu SM, Adirim TA. The role of medical home in emergency department use for children with developmental disabilities in the United States. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30:534–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vohra R, Madhavan S, Sambamoorthi U, St Peter C. Access to services, quality of care, and family impact for children with autism, other developmental disabilities, and other mental health conditions. Autism. 2014;18:815–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zajicek-Farber ML, Lotrecchiano GR, Long TM, Farber JM. Parental Perceptions of Family Centered Care in Medical Homes of Children with Neurodevelopmental Disabilities. Matern Child Health J. 2015;19:1744–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Health care innovation awards round two project profiles. Bethesda: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barton J, Castor K. Advancing Care for Exceptional Kids Act of 2014, H.R. 546 Energy and Commerce Committee, Subcommittee on Health. U.S. Congress; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Woods ER, Bhaumik U, Sommer SJ, Ziniel SI, Kessler AJ, Chan E, et al. Community asthma initiative: evaluation of a quality improvement program for comprehensive asthma care. Pediatrics. 2012;129:465–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon JB, Colby HH, Bartelt T, Jablonski D, Krauthoefer ML, Havens P. A tertiary care-primary care partnership model for medically complex and fragile children and youth with special health care needs. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161:937–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mosquera RA, Tyson JE, Avritscher EB, Pedroza C, Harris TS, Samuels CL, et al. Effect of an enhanced medical home on serious illness and cost of care among high-risk children with chronic illness: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014. December 24-31;312:2640–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brousseau DC, Owens PL, Mosso AL, Panepinto JA, Steiner CA. Acute care utilization and rehospitalizations for sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2010;303:1288–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yusuf HR, Atrash HK, Grosse SD, Parker CS, Grant AM. Emergency department visits made by patients with sickle cell disease: a descriptive study, 1999–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:S536–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Charache S, Terrin ML, Moore RD, Dover GJ, Barton FB, Eckert SV, et al. Effect of hydroxyurea on the frequency of painful crises in sickle cell anemia. Investigators of the Multicenter Study of Hydroxyurea in Sickle Cell Anemia. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1317–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Andemariam B, Jones S. Development of a New Adult Sickle Cell Disease Center Within an Academic Cancer Center: Impact on Hospital Utilization Patterns and Care Quality. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2016;3:176–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adewoye AH, Nolan V, McMahon L, Ma Q, Steinberg MH. Effectiveness of a dedicated day hospital for management of acute sickle cell pain. Haematologica. 2007;92:854–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wright J, Bareford D, Wright C, Augustine G, Olley K, Musamadi L, et al. Day case management of sickle pain: 3 years experience in a UK sickle cell unit. Br J Haematol. 2004;126:878–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wier LM, Yu H, Owens PL, Washington R. Overview of Children in the Emergency Department, 2010: Statistical Brief #157. 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Alpern ER, Clark AE, Alessandrini EA, Gorelick MH, Kittick M, Stanley RM, et al. Recurrent and high-frequency use of the emergency department by pediatric patients. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2014;21:365–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]