Highlights

-

•

We link social exchange relationships to the family relationships in entrepreneurship.

-

•

Family support have mixed effects on entrepreneurial stressors-well-being relationships.

-

•

The moderating effects entail more between-person heterogeneity than within -person heterogeneity.

Keywords: Entrepreneurial stressors, Entrepreneurial well-being, Between- and within-person effects, Family support, Social exchange

Abstract

Current studies suggest mixed effects concerning the impact of the family system on entrepreneurial outcomes. Through the integration of the family embeddedness theory and social exchange theory, we further investigate the potential benefits and costs of family support as a social exchange process between entrepreneurs and their family members. We propose that perceived family support can differentially shape well-being across different entrepreneurial contexts (financial and workload stressors) depending on the nature of the exchange relationship (economic vs. social), thereby dual effects are anticipated from time-based and temporal processes. After analyzing the data gathered from 61 entrepreneurs over 14 days, we found evidence that high levels of family support attenuate the relationships between the financial stressor and the well-being indicators but amplify the relationships between the workload stressor and the well-being indicators. These results demonstrate family support process models are central to between-person heterogeneity. The theoretical and practical implications are discussed.

1. Introduction

Family plays an essential role in the entrepreneurial process because of robust associations between family embeddedness in business and entrepreneurial actions or outcomes (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Jennings and McDougald, 2007, Sharma, 2004). The family embeddedness perspective highlights the significance of family roles and relationships and focuses on the interpersonal exchange process between entrepreneurs and family members (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Aldrich and Kim, 2007). Within such an exchange process, entrepreneurs mobilize resources from their family members that can be conducive to new venture performance (objective success) and to themselves (subjective success), while family members potentially receive economic or social benefits (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Rogoff and Heck, 2003).

Decades of research, however, demonstrate that specific family embeddedness actions (e.g., family capital, family support) generate various outcomes for both ventures and entrepreneurs. For instance, some studies reveal that the financial capital or support provided by family members decreases the entrepreneurs' likelihood of establishing ventures (Sieger & Minola, 2017), as well as undermines the success of the business (Au & Kwan, 2009), whereas others suggest that family support or capital enhances both entrepreneurs’ well-being and business performance (Hatak and Zhou, 2019, Powell and Eddleston, 2013, Powell and Eddleston, 2017). In terms of these inconsistent findings, we assume that there is a need to further theorize and test how family members and entrepreneurs initiate interpersonal exchanges and how entrepreneurs or their ventures benefit from these relationships, depending upon the type of supportive resource.

We contend that the impact of the family system on entrepreneurial outcomes depends on the specific interpersonal exchanges and entrepreneurial contexts. Drawing on the social exchange theory, regarded as a nuanced theoretical lens for studying social relationships in work settings (Cropanzano et al., 2017, Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005), we conceptualize the interpersonal exchange processes between entrepreneurs and family members as social exchange relationships using the construct family support. Consistent with the premises of this theory, interpersonal connections as they occur in the workplace can be divided into economic or social exchange relationships (Foa & Foa, 1980), which evolve depending on the individuals’ motivations and reciprocity rules (Blau, 1964). That is, embedded in entrepreneurial contexts, the economic exchange relationship is formed to meet the entrepreneurs’ financial needs, with family members obtaining economic repayment, whereas the social exchange relationship is formed to address the entrepreneurs’ social and esteem needs, which strengthens mutual trust and obligation. Hence, through explicitly modeling the exchange context, our study adds clarity to the family’s influence on entrepreneurship.

Second, we assume that the exchange process between entrepreneurs and family members frequently occurs in stressful contexts that characterize the entire entrepreneurial process (Rauch, Fink, & Hatak, 2018). Entrepreneurial stressors, defined as the specific conditions entrepreneurs encounter in their daily work lives (Boyd and Gumpert, 1983, Dijkhuizen et al., 2016, Kollmann et al., 2019), impact entrepreneurial well-being (Stephan, 2018, for a review), which is increasingly regarded as a critical indicator for subjective venture success (Wiklund et al., 2019). We focus on the moderating effects of family support on the association between entrepreneurial stressors and entrepreneurial well-being, according to the theoretical model of family social support in an entrepreneurial setting (Kim et al., 2013, Powell and Eddleston, 2013). We posit that when exposed to different stressors (e.g., financial, workload), the entrepreneurs’ perceived family support might generate different effects on their well-being relative to the nature of the social exchange relationships (economic vs. social).

Third, a constraining assumption for prior studies has been to conceptualize the linkage between family embeddedness actions and entrepreneurship as a stable and enduring property. Nevertheless, researchers call for dynamic inferences about the effects of the family system on the dynamic entrepreneurial process (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Levesque and Stephan, 2020). Therefore, we incorporate time into the theoretical model and explore the temporal patterns in the proposed relationships. Facilitating the contributions with time-based and temporal hypotheses spurs researchers to consider two models, i.e., between-person differences and within-person processes (Curran and Bauer, 2011, McCormick et al., 2020, Uy et al., 2010). The between-person analysis allows us to explore how entrepreneurs differ in their responses to higher or lower levels of entrepreneurial stressors when experiencing higher or lower levels of family support. Of particular note, between-person differences can manifest because of time, thus demonstrating how entrepreneurs differ in terms of temporal constructs (Shipp & Cole, 2015). In contrast, within-person analysis allows us to explore how entrepreneurs respond to varying levels of stressors based on varying levels of family support within the context of time. Because these two levels of analysis can differ in direction and impact in the empirical analyses (Curran and Bauer, 2011, McCormick et al., 2020), we adopted the experience sampling method (ESM), which is considered an outlet for modeling time-based and temporal patterns in entrepreneurial settings (Uy et al., 2010). Each entrepreneur completed survey items related to perceived family support, entrepreneurial stressors, and well-being over a period of two weeks.

Fourth, we test the proposed theoretical framework utilizing Chinese entrepreneurs. As has been noted (Bruton, Zahra, & Cai, 2018), it is especially meaningful to study entrepreneurship in developing or emerging economies (rather than just the U.S. and European economies) to provide insights into the entrepreneurial process across contexts and espouse Western-based theoretical values and foundations. The research shows that among emerging economies, China has a high proportion of entrepreneurs who have contributed to significant economic growth and job creation (Ahlstrom and Ding, 2014, Su et al., 2015). In addition, several studies have emphasized the role of family relationships in establishing and operating new ventures in China (e.g., Au and Kwan, 2009, Pistrui et al., 2001); this special role of the family can also be found in other contexts (e.g., Chang et al., 2009). Thus, the Chinese context provides a fresh perspective to study the effects of the social exchange process between entrepreneurs and family members, with the potential for further generalizability.

Our study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, by integrating the social exchange perspective into the family embeddedness theory, we generate new insights into the different effects of family support on entrepreneurial outcomes relative to the nature of the familial exchange relationship. In addition to showing the varying effects within different social exchange relationships, we further illuminate the mixed role that family members can play in entrepreneurship and provide additional evidence of the interpersonal relationship between entrepreneurs and family members. To this end, we extend the current theoretical perspective concerning the association between family embeddedness and entrepreneurship (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Jennings and McDougald, 2007). Second, through incorporating time into the proposed theoretical model, our study primarily responds to the call to explore organizational and entrepreneurial phenomena using a temporal lens (Levesque and Stephan, 2020, McMullen and Dimov, 2013, Shipp and Cole, 2015). We explicitly formulate a multilevel framework (between-person vs. within-person) to explore the joint effects of family support and stressors on entrepreneurial well-being. The results show that the constructs’ relationships lead to more between-person differences than within-person processes. Hence, our study advances a complete understanding of how the different types of social exchange relationships between entrepreneurs and family members can vary because of and within the context of time. Third, through testing the theoretical model rooted in Western contexts with entrepreneurs residing in an emerging economy, our study contributes to understanding the context-specific entrepreneurial process and expands the Western-based theoretical foundations (Bruton et al., 2018, Su et al., 2015).

2. Theoretical background

2.1. The role of family embeddedness in entrepreneurship

In accordance with the family embeddedness theory, family members’ roles and relationships in entrepreneurship can influence the entire entrepreneurial process from organizational emergence to venture success (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Rogoff and Heck, 2003, Sharma, 2004). One prominent characteristic of such a relational embeddedness is that entrepreneurs can take full advantage of the resources provided by family members to engage in entrepreneurial actions. Typical examples of these resources include labor, knowledge, information, and finance (Pearson et al., 2008, Dyer et al., 2014). Researchers operationalize family embeddedness empirically using different theoretical constructs, such as family capital (Chang et al., 2009, Chua et al., 2011), family support (Powell and Eddleston, 2013, Powell and Eddleston, 2017), or family ties (Arregle et al., 2015), and find that the family system exerts a significant influence on entrepreneurial processes (e.g., start-up decisions) and outcomes (e.g., firm performance, well-being), with both positive and negative effects.

The past research has demonstrated the relative benefits of family resources to entrepreneurship based on the limited resources available to entrepreneurs. For example, in relation to the start-up process, two studies reveal that family social capital, also measured as family support, helps entrepreneurs establish or prepare for a new venture (Chang et al., 2009, Edelman et al., 2016). Another study shows that family involvement may be instrumental in the acquisition of debt financing for start-up activities (Chua et al., 2011). Regarding the venture development process, several lines of research suggest that family resources help entrepreneurs expand their social networks, such as financial (Steier, 2007) and political (Ge, Carney, & Kellermanns, 2019) networks. There is also evidence that family resources are beneficial for immigrant and serial entrepreneurship (Bird & Wennberg, 2016). Overall, the studies demonstrate that family resources enhance both firm performance (Cruz, Justo, & De Castro, 2012) and personal well-being (Powell and Eddleston, 2013, Powell and Eddleston, 2017).

In contrast, researchers posit that the relational dimension of embeddedness also emphasizes strong ties among individuals and carries the expectation of reciprocity and equity (Adler and Kwon, 2002, Granovetter, 1985). Through these strong ties, entrepreneurs and family members can forge shared obligations and expectations closely related to both business and nonbusiness activities (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003). If such mutual obligations and expectations are not met, however, family embeddedness could lead to conflicts among family members and place resources at risk, which, in turn, exerts a negative impact on entrepreneurial processes and outcomes. Seen in this light, the empirical studies have shown that family members’ financial support is negatively related to entrepreneurs’ start-up decisions (Edelman et al., 2016, Sieger and Minola, 2017), in particular, that family embeddedness or family-to-business interference can undermine firm performance (Au and Kwan, 2009, Arregle et al., 2015) and lead entrepreneurs to consider exiting (Hsu, Wiklund, Anderson, & Coffey, 2016). Thus, to further understand the mixed effects of family resources on entrepreneurship, we take the perspective of reciprocity and equity in the interpersonal relationship between entrepreneurs and family members by utilizing the social exchange theory (Blau, 1964, Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005).

2.2. A social exchange perspective on family embeddedness in entrepreneurship

The social exchange theory applied in work settings explicitly regards social relationships as involving transactions or exchanges between two or more individuals based on the norms of reciprocity and equity (Cropanzano et al., 2017, Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005), which can be further classified as economic or social relationships in terms of the exchanged resources and anticipated benefits (Foa & Foa, 1980). Specifically, economic exchange relationships entail extrinsic benefits that have economic value and include the reciprocation of tangible assets (e.g., money), whereas social exchange relationships entail intrinsic benefits that convey emotional attachments and include the reciprocation of intangible assets (e.g., care, esteem). Although each relationship can morph into the other as trust grows in both parties (Meyer, Stanley, Herscovitch, & Topolnytsky, 2002), explicitly separating them as forms of exchange allows us to theoretically clarify how both parties initiate interpersonal exchanges as well as how they benefit from these relationships (Cropanzano & Mitchell, 2005). It is assumed that there should be a match between the type of exchange relationship and the exchanged resources in terms of the quality of the relationship. For instance, in economic relationships, if the actor fails to execute economic obligations, either the actor or the target (or both) might reconsider the reciprocity norm and lessen their investment in this relationship, causing both to feel a decreased sense of well-being (Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999).

Regardless of its typology, the exchange process begins and evolves in a similar way. The actor initiates either positive or negative actions (e.g., support) and the target reciprocates with good or bad relational (e.g., well-being) and behavioral responses (e.g., start-up behavior) (Cropanzano et al., 2017). For example, family members may provide financial support or capital to entrepreneurs who need financial resources for start-up activities (positive actions). Entrepreneurs will reciprocate with relational and behavioral responses based on their judgment and business contexts. Prior studies have shown that financial support is negatively related to young entrepreneurs’ start-up behaviors in terms of reciprocity and equity (negative behavioral responses) (e.g., Edelman et al., 2016). Other studies, however, suggest that family support is positively related to well-being, such that entrepreneurs should feel cared for and valued in terms of familial emotional bonds and their own psychological states (positive relational responses) (e.g., Powell & Eddleston, 2013).

Drawing on this theoretical distinction, we model the two types of social exchange relationships between entrepreneurs and family members as they occur in entrepreneurs’ daily lives by focusing on stressors that constrain entrepreneurs’ actions or well-being (Kollmann et al., 2019, Rauch et al., 2018). According to a recent study (Stephan, 2018), financial and workload stressors that are seen as the most widely explored types of stressors are intrinsic to entrepreneurial processes, such that entrepreneurs operate ventures in unique conditions that demand excessive time and effort (Cardon & Patel, 2015), as well as financial resources, which are critical to sustain and develop the business (Shepherd, Wiklund, & Haynie, 2009). These stressors appear to be closely associated with economic and social exchange relationships. Thus, we investigate how entrepreneurs’ perceived family support (positive actions) can impact their relational responses (entrepreneurial well-being) across these two entrepreneurial contexts. Specifically, for the economic exchange relationship, we test whether perceived family support can buffer the impact of financial stressors on entrepreneurial well-being. With regard to the social exchange relationship, we test whether perceived family support attenuates or amplifies the impact of workload stressors on entrepreneurial well-being. In particular, we take a time-based and temporal focus to determine how these relationships evolve and change both between and within entrepreneurs’ daily work lives and frame our hypotheses based on these assumptions. Fig. 1 depicts our different predictions about the impact of family support on well-being across entrepreneurial contexts in terms of the type of exchange relationship in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives.

Fig. 1.

Hypothesized theoretical model in current study.

3. Hypotheses development

3.1. The economic exchange relationship: Family support, financial stressors, well-being

Research suggests that financial stressors pose significant barriers to the development of new ventures and have a negative impact on entrepreneurial well-being (Annink et al., 2016, Au and Kwan, 2009, Pollack et al., 2012). A lack of financial resources seriously impedes entrepreneurs’ pursuit of their goals, such as adjusting business strategies, reducing expenses, and seeking revenue resources. This spiral of resource loss impairs entrepreneurs’ positive emotions and job satisfaction and leads to distress (Annink et al., 2016, Pollack et al., 2012).

Nonetheless, entrepreneurs can utilize their available job resources to cope with such critical entrepreneurial stressors (Dijkhuizen et al., 2016). Since entrepreneurs have frequent personal contacts with their close family members (e.g., parents, spouses), the availability of family support can moderate the relationship between financial stressors and well-being. This typically reflects the economic exchange relationship between entrepreneurs and their family members because entrepreneurs' work and family roles are more intertwined than those of employees (Aldrich & Cliff, 2003). The supportive resources provided by family members are positive initiating actions, which include more flexible funding sources for entrepreneurs who need to nurture and sustain new ventures, compared with sources from other financial institutions or investors (Edelman et al., 2016, Rogoff and Heck, 2003). An entrepreneur who needs financial capital to solve an urgent business issue on a given day may turn to a family member rather than an outside source. This perceived family support may buffer the negative effect of financial stressors on entrepreneurial well-being and, hence, facilitate positive relational responses. As a consequence, entrepreneurs might reciprocate by providing economic benefits to family members.

Further, we argue that this moderating effect can evolve and change at both the between- and within-person levels. At the between-person level, the focus is on how interindividual differences manifest in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives. Entrepreneurs who perceive higher levels (compared to lower levels) of family support can effectively cope with financial stressors and, thus, feel an enhanced sense of well-being. Higher levels of family support grant entrepreneurs both tangible and intangible resources that can be utilized to solve business issues and regulate emotional distress caused by financial issues (Steier, 2003, Powell and Eddleston, 2013). In addition, higher levels of family support help entrepreneurs make adjustments to their daily entrepreneurial goals related to financial issues. For instance, given that entrepreneurs need financial resources to develop new products or services, family members, in addition to providing financial support, might facilitate obtaining resources through their broad networks of potential buyers, suppliers, or other stakeholders (Arregle et al., 2015, Rogoff and Heck, 2003). Such individual differences in perceived support might explain why some entrepreneurs maintain their subjective well-being when exposed to financial crises along the entrepreneurial process. Therefore, the perceived availability of family support appears to be directly related to the betterment of well-being, particularly when coping with financial stressors. We propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1

Entrepreneurs’ perceived family support moderates the relationship between financial stressors and well-being such that financial stressors are more positively related to well-being when family support is high (compared to low) in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives.

In contrast, within-person processes focus on intraindividual differences and reflect the fluctuating nature of the proposed relationships in constructs (McCormick et al., 2020, Uy et al., 2010). Rather than comparing the effects between different entrepreneurs, within-person analysis uncovers how varying levels of perceived family support can moderate the fluctuating internal relationship between financial stressors and well-being for entrepreneurs. Hence, we assume that the stress-buffering effect of perceived family support may vary internally for entrepreneurs on a daily basis or via the context of their daily work lives. For instance, an entrepreneur who encounters an urgent and difficult financial issue on a particular day may feel that the severity of the financial stressor fluctuates in relation to the business operations. In this situation, it is unclear whether higher levels of family support remain functional in this temporal exchange process (e.g., facilitating debt-financing, helping to adjust goals). This situation-specific assumption is in accordance with the uncertain nature of entrepreneurship that is linked to the occurrence of entrepreneurial stressors (Rauch et al., 2018). Accordingly, this suggests that although there are interindividual differences in this moderating effect, some entrepreneurs may benefit (or not) from this exchange process in a particular situation. We propose a similar hypothesis as follows:

Hypothesis 2

Within entrepreneurs, perceived family support moderates the relationship between financial stressors and well-being such that financial stressors are more positively related to well-being when family support is high (compared to low) in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives.

3.2. The social exchange relationship: Family support, workload stressors, well-being

Because new ventures lack efficient structures that mature firms have already developed, entrepreneurs’ daily business lives consist of excessive workloads, including long working hours, employee problems, and operational issues (Bradley and Roberts, 2004, Cardon and Patel, 2015). Unlike a financial stressor, which is a hindrance to new ventures, a workload stressor is seen as both challenging and motivating and is associated with personal development and gain (LePine, Podsakoff, & LePine, 2005). In terms of this critical perspective towards the sources of stressors, we believe that there are inconsistent findings concerning the linkage between workload stressors and well-being. While a majority of studies suggest that different types of workload stressors are negatively related to entrepreneurial well-being and health (e.g., Kollmann et al., 2019, Stephan and Roesler, 2010), others suggest no association with entrepreneurial well-being (e.g., Millan, Hessels, Thurik, & Aguado, 2013).

We model family support as the boundary condition for the association and assume that this moderation effect fits into the context of the social exchange process between entrepreneurs and family members. Although excessive workload can be stressful and exhaustive in nature, entrepreneurs accept such conditions and attempt to exert more control over job-related tasks. For instance, a study shows that differences in job control can explain why entrepreneurs experience lower levels of job stressors than do employees (Hessels, Rietveld, & van der Zwan, 2017). Family support, then, may not be seen as an essential or efficient coping resource but as generating socioemotional connections or mutual obligations (Arregle et al., 2015, Edelman et al., 2016). The need to reciprocate might make the entrepreneur feel beholden and, ultimately, put family relationships at risk (Arregle et al., 2015, Sieger and Minola, 2017). As a consequence, such a relationship might lead to entrepreneurs having mixed relational responses (positive vs. negative) and threaten their personal well-being (Buunk & Schaufeli, 1999).

We posit that the consequences of the social exchange relationship are impacted by individual differences in entrepreneurs’ perceptions of different levels of family support in their daily work lives, with higher levels of family support amplifying the impact of workload stressors on entrepreneurial well-being. Entrepreneurs who have received sufficient monetary resources from family members to relieve their financial stress might feel beholden and more stressed if they continue to invest other family resources into the business domain (e.g., cope with workload) (Arregle et al., 2015, Steier, 2003). According to the reciprocity norm of family embeddedness, utilizing excessive family resources not only places family assets at risk but also undermines the sustainability of the family system (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Olson et al., 2003). In such a situation, higher levels of family support can stimulate entrepreneurs’ sense of guilt over family members’ expectations, which, in turn, causes them to feel incapable of reciprocating.

Second, higher levels of family support aimed at relieving the entrepreneurial workload may indicate that family members are overembedded in entrepreneurs’ business networks. This overembeddedness may restrain entrepreneurs from seeking outside resources and establishing relationships with stakeholders (i.e., investors), which potentially limits venture growth and profits (Arregle et al., 2015, Jack, 2005). Perhaps the most significant issue is that overembeddedness is closely linked to family-to-business interference. If entrepreneurs constantly feel indebted to family members or constrained by family resources, they may experience role conflict between their work and family domains (Jennings & McDougald, 2007). Prior studies show that entrepreneurs who experience family-to-business interference are subject to increased stress as well as decreased life satisfaction and psychological well-being (Beutell, 2007, Shelton, 2006).

In contrast, entrepreneurs who perceive lower levels of family support in their daily work lives might experience increased well-being when exposed to workload stressors. Lower levels of family support entail lower levels of reciprocation and family-to-business interference, permitting entrepreneurs to be more autonomous in dealing with their business affairs via expanding other social networks. To some extent, they can devote more time and energy to cope with workload stressors by utilizing certain levels of family support. For instance, an empirical study shows that Chinese entrepreneurs utilize initial funding from family members rather than from outsiders based on lower levels of transaction costs and family interference in the business (Au & Kwan, 2009). Another qualitative study clearly shows that entrepreneurs try to utilize different strategies to maximize the advantages of family capital (Zhang & Reay, 2018). Thus, we propose the following hypothesis for the social exchange relationship related to average effects as follows:

Hypothesis 3

Entrepreneurs’ perceived family support moderates the relationship between workload stressors and well-being such that workload stressors are more negatively related to well-being when family support is high, whereas workload stressors are more positively related to well-being when family support is low in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives.

Another critical issue is how entrepreneurs respond to varying levels of workload stressors under varying levels of perceived family support in their daily work lives, alongside the fluctuating severity of the workload. As entrepreneurs have their own construal of working environments and relationships over time, the impact might vary within entrepreneurs. For some, higher levels of family support can significantly amplify the impact of workload stressors on well-being, whereas for others, higher levels of family support might bear attenuating effects. For instance, according to the dynamic approach to the effects of social support in stressful contexts (e.g., Hilpert et al., 2018, Taylor, 2011), supportive actions enacted by close others in times of need should be beneficial to recipients’ well-being. That is, it can be assumed that on days of high workload stressors (compared to low), entrepreneurs might benefit from higher levels of family support because of strong familial cohesiveness, which leverages the impact of support (Edelman et al., 2016, Sieger and Minola, 2017). In a similar vein, lower levels of family support have similar or different moderating effects compared with the effects proposed at the between-person level. Lacking sufficient levels of family support in times of need might cause entrepreneurs to doubt the quality of their family relationships and even their own family status (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Therefore, we propose competing hypotheses relative to between-person effects as follows:

Hypothesis 4

Within entrepreneurs, perceived family support moderates the relationship between workload stressors and well-being such that workload stressors are more positively related to well-being when family support is high, whereas workload stressors are more negatively related to well-being when family support is low in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives.

4. Methods

4.1. Data collection

We utilized ESM to collect diary data, which is the optimal method for separating the between- and within-person relationships in temporal constructs (Curran and Bauer, 2011, McCormick et al., 2020). This approach holds several advantages for our research question, including capturing entrepreneurs’ daily experiences as they occur in entrepreneurial contexts, thus allowing social exchange processes to be explored in situ, and reducing retrospection by having participants report on the event on the day that it occurred (Beal, 2012).

Two days before the beginning of the ESM survey, entrepreneurs completed a survey that assessed their demographics, such as firm size, firm age, participant gender, and participant age. Afterwards, adopting a day reconstruction method (Bakker, Demerouti, Oerlemans, & Sonnentag, 2013), we asked the participants to respond to daily surveys every evening over two consecutive weeks (starting on a Monday). We used a social media application (APP) that is widely used on smart phones in China (WeChat) and includes a Web survey platform. Through the APP, we then established four discussion groups involving all entrepreneurs to remind them to take the surveys. To streamline the process and ensure the quality of the data collection, we sent participants links to the surveys through the platform every day at 8:00p.m. The respondents were asked to report their entrepreneurial stressors, well-being, and perceived family support between 8:00 and 9:00p.m. Altogether, we sent 882 notifications or alerts one hour after the beginning of the survey and we received 827 valid reports. This high response rate reflects our investment of time and effort to interact with all the entrepreneurs before and during the study.

4.2. Sample

Entrepreneurial parks or clusters support the generation of new ventures, commercialize new technologies or services, and promote the accumulation of experience and knowledge sharing (Zahra, Wright, & Abdelgawad, 2014). In China, the number of such parks or clusters represents the developmental level of entrepreneurship, which has increasingly gained political and financial support (e.g., microcredit, free offices, tax incentives). Thus, we recruited entrepreneurs who reside in entrepreneurial parks or clusters attached to three large cities (Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen). We surveyed active entrepreneurs who, as founders, are independently in charge of new ventures, which involves exploiting opportunities and resources under the context of uncertainty. Using the random sampling method, in collaboration with governmental institutions within parks or clusters, we identified and contacted almost 200 entrepreneurs, of whom 100 expressed interest in our study. We sent letters of invitation to these 100 entrepreneurs; 63 entrepreneurs replied and agreed to participate. Two responses were eliminated due to a substantial amount of missing information, resulting in a final sample of 61 entrepreneurs.

The average age of the entrepreneurs in our sample was 35.36 (SD = 6.22). The majority of respondents were male (82%) and had earned a university degree (76%). The average age of these ventures was four years (SD = 3.91) and the average number of full-time staff was six (SD = 9.76). The participants worked an average of 11 h per day (SD = 3.36) and represented a variety of industries as follows: wholesale and retail (27%), information technology (13%), financial and professional services (17%), and other industries (43%).

4.3. Measures

Because entrepreneurs have extremely busy daily work lives, we utilized shortened versions of all measures, which is in line with the daily survey strategy (Beal, 2012) and other studies focusing on daily processes in entrepreneurial settings (Uy et al., 2017, Weinberger et al., 2018).

Daily entrepreneurial stressors. We focused on two types of stressors that are intrinsic to entrepreneurship: workload and financial stressors (Stephan, 2018). In order to capture how entrepreneurs perceived these stressors in their daily work lives, we generated stress items based on the Daily Inventory of Stressful Events (DISE, Almeida, Wethington, & Kessler, 2002). This scale was developed utilizing checklist measures of discrete events occurring in both life and work domains by using a single word or phrase (i.e., arguments, stressors at work, network stressors), which is useful in assessing an individual’ s exposure to daily stressors (e.g., Sin et al., 2015). Following this approach, we adapted the scale to accommodate discrete entrepreneurial contexts and used two single words to assess the workload and financial stressors, respectively. During the survey period, the entrepreneurs answered the question, “Did you experience the following two entrepreneurial stressors today?” and then rated the intensity of their experience on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all to 5 = extremely).

Although this measure is adapted based on a widely used scale for assessing daily stressors, this is the first time that it has been used in entrepreneurial contexts. Therefore, we performed strict validity and reliability tests. We first conducted Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) to ensure that the construct validity and the fit indices of the two-factor model met the criteria well (χ2 = 43.54, df = 4, CFI = 0.95, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.03). To ensure the reliability of the daily measures, we calculated two types of Cronbach’ s alpha (Cranford et al., 2006). The between-person reliability (R) of measures was averaged over 14 (K) days (Rkf) and the within-person reliability of change over 14 days was also calculated (Rc). For the stress scale, Rkf was 0.97 and Rc was 0.35. The lower levels of within-person reliability might be attributed to the assessment of the stressors across different work domains and the aggregation of the two items. It further indicates the need to separate the between- and within-person levels of analysis.

Daily perceived family support. Initially, we asked each entrepreneur which family member(s) they were most likely to turn to when exposed to stressors in their daily work lives. Forty percent reported parents, 25% reported intimate partners or spouses, 20% reported both parents and intimate partners, and 15% mentioned other relatives. Therefore, in line with prior studies focusing on general family members (e.g., Bird and Wennberg, 2016, Edelman et al., 2016, Powell and Eddleston, 2013, Sieger and Minola, 2017), we asked participants to rate the intensity of perceived family support provided by their general family members rather than a specific member. To assess participants’ perception of daily family support, we used four items adapted from the 2-Way Social Support Scale (2-Way SSS, Shakespeare-Finch & Obst, 2011) as well as the Family-to-Business Support scale, which was designed for and was used specifically in entrepreneurial contexts (Eddleston and Powell, 2012, Powell and Eddleston, 2013). The participants were asked to indicate their agreement to given statements using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). The items for family support were: “Today, there is someone from my family that I can talk to about my business”; “Today, when I’m frustrated by my business, there is someone from my family that can try to understand”; “Today, there is someone from my family who would offer the following to me (e.g., offering business solutions, providing financial assistance, sharing household chores)”; and “Today, there is someone from my family that can give me useful feedback about my ideas concerning my business.” Even if the items tapped different types of support (e.g., emotional, practical) that might exert different effects on family relationships, we were interested in exploring the impact of overall family-to-business support on the social exchange relationships placed on a temporal framework (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Thus, we aggregated all the items that can represent daily perceived family support. The reliability of the aggregated items was high to moderate (Rkf = 0.99 and Rc = 0.74).

Daily entrepreneurial well-being. Wiklund and colleagues (Wiklund et al., 2019) conceptualized entrepreneurial well-being as the experience of satisfaction, positive affect, infrequent negative affect, and psychological functioning. We focused on the affective (positive and negative emotions) and cognitive (job satisfaction) components of entrepreneurial well-being that can fluctuate daily in organizational and entrepreneurial contexts (Foo et al., 2009, Uy et al., 2017). We utilized the shortened Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) to assess the participants’ momentary negative and positive emotions. The options for positive emotions were: enthusiastic, attentive, proud, interested, and inspired. The corresponding options for negative emotions were: upset, irritable, nervous, distressed, and jittery. The participants were asked, “How do you feel at the moment?” In relation to job satisfaction, we adapted three items from the global job satisfaction scale (Linzer et al., 2000), which was administered with momentary time instructions (“Right now, I find my entrepreneurial work personally rewarding”; “At this very moment, I am satisfied with my entrepreneurial work”; and “Today, my work in this practice has met my expectations”). All ratings were recorded on a 5-point scale (1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). To ensure the construct validity of entrepreneurial well-being, we conducted CFA. The fit indices of the three-factor model met the criteria well (χ2 = 245.43, df = 62, CFI = 0.96, TLI = 0.95, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.03). The reliability of the measures was Rkf = 0.99 and Rc = 0.81 for positive emotions, Rkf = 0.99 and Rc = 0.83 for negative emotions, and Rkf = 0.98 and Rc = 0.81 for job satisfaction.

Control variables. We controlled for both the person- and firm-level characteristics to rule out potential confounding effects. In relation to person-level variables, we controlled for age and gender, which are associated with entrepreneurial processes and outcomes (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). We controlled for prior venture experience as it shapes the effects of entrepreneurial stressors on entrepreneurial well-being (Kollmann et al., 2019). Because we focused on the effects of perceived family support, we controlled for marital status (assessed by whether participants were married) (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). With regard to firm-level variables, we controlled for firm age and size, which are seen as important contextual factors shaping entrepreneurs’ perceptions of daily stressors (Stephan, 2018). As we adopted a temporal and time-oriented approach and were especially interested in how entrepreneurs exhibited fluctuations in stressors, family support, and well-being over time, we controlled for the variable of time (coded from 0 to 13) (Shipp & Cole, 2015).

4.4. Analytical strategy

Multilevel analyses. Our data have a typically nested nature, such that daily data were nested within entrepreneurs and within-person variables were nested within between-person variables. Accordingly, we used multilevel modelling to test all hypotheses (Curran & Bauer, 2011), allowing us to simultaneously model the between-person level (Level 2) and within-person level (Level 1). We grand-mean centered all independent variables to model between-person relationships that indicate the average scores for each entrepreneur across 14 days, whereas we group-mean centered all independent variables to model within-person relationships that indicate daily deviations in study variables across all analyzed days. This approach avoids multicollinearity and generates reliable statistical estimations (Curran & Bauer, 2011). The dependent variable (entrepreneurial well-being) and control variables remained uncentered.

Hypothesis testing. To test our hypotheses, we ran several multilevel models following a stepwise approach (Hoffman, 2015). First, because we proposed hypotheses relative to both between- and within-person relationships, we conducted two preliminary analyses to confirm our decision. We conducted homology tests to check whether these two levels of analysis differed significantly using a Fisher r-to-z transformation (Bliese, 2016, McCormick et al., 2020). We then ran unconditional cell means models to check the within-person variances (intraclass correlation, ICC). Second, using a full maximum likelihood estimation, we ran the main effect models, including both fixed and random effects. Third, we included interaction effects across all levels to examine the hypotheses. Finally, we used two indices to assess the model fit and effect sizes. The first value (Rm) was the marginal R of the model, which explains the model fit for only the fixed effects; the second value (Rc) was the conditional R of the model, which explains the overall model fit (Nakagawa & Schielzeth, 2013). All the statistical models were calculated with the software R.

5. Results

5.1. Preliminary analyses

Table 1 shows the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study and control variables. We checked whether statistically significant differences existed between the between- and within-person correlations in the main effects. Table 1 shows that of nine groups of correlation comparisons, only four were insignificant (workload stressor-job satisfaction, financial stressor-positive emotions, financial stressor-job satisfaction, and family support-negative emotions) while others were significant. In addition, we found substantial within-person variances (ICC) in daily variables and confirmed the use of multilevel modeling (47% for workload stressor, 72% for financial stressor, 72% for family support, 64% for positive emotions, 58% for negative emotions, and 46% for job satisfaction).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study variables.

| Variables | Mean | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily variables | ||||||||||||||

| 1Workload stressor | 1.89 | 1.03 | 0.22*** | -0.05 | -0.02 | 0.13*** | -0.03 | |||||||

| 2 Financial stressor | 2.17 | 0.97 | 0.34*** | -0.04 | 0.02 | 0.13*** | 0.03 | |||||||

| 3 Family support | 2.85 | 0.89 | -0.09* | -0.26*** | 0.16*** | -0.03 | 0.18*** | |||||||

| 4 Positive emotion | 3.23 | 0.88 | -0.11** | -0.15*** | 0.47*** | -0.20*** | 0.65*** | |||||||

| 5 Negative emotion | 1.98 | 0.83 | 0.37*** | 0.38*** | -0.15*** | -0.20*** | -0.09* | |||||||

| 6 Job satisfaction | 2.75 | 0.94 | -0.06 | -0.03 | 0.46*** | 0.65*** | -0.09* | |||||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||||||

| 7 Age | 36.36 | 6.22 | -0.13*** | -0.06 | -0.19*** | -0.01 | -0.06 | -0.07* | ||||||

| 8 Gender | 0.83 | 0.38 | 0.11** | 0.02 | -0.06 | -0.08* | 0.09* | -0.05 | 0.05 | |||||

| 9 Marital status | 0.76 | 0.43 | -0.13*** | -0.13*** | -0.07*** | 0.02 | -0.13*** | -0.04 | 0.51*** | 0.06 | ||||

| 10 Prior venture experience | 0.40 | 0.49 | 0.12*** | 0.04 | -0.09* | 0.07* | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.37*** | 0.00 | -0.04 | |||

| 11Firm age | 4.21 | 3.81 | -0.08* | -0.04 | -0.14*** | -0.14*** | -0.04 | -0.17*** | 0.34*** | 0.06 | 0.24*** | 0.06 | ||

| 12 Firm size | 5.62 | 9.76 | -0.05 | -0.01 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.09* | -0.03 | 0.02 | 0.13*** | -0.04 | 0.13*** | -0.09** | |

| 13 Time | 6.50 | 4.03 | -0.02 | -0.10** | -0.02 | -0.07* | -0.10** | -0.10** | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.00 |

Note. SD = standard deviation; Gender: 0 = male/1 = female; Marital Status: 0 = married /1 = unmarried; Prior venture experience: 0 = no experience/1 = having experience. Correlations above the diagonal is within-person correlations (only daily variables) and below the diagonal is between-person correlations. The correlation coefficients in bold indicate that the between-and within-person correlations are significantly different from each other.

* p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001.

5.2. Hypothesis testing

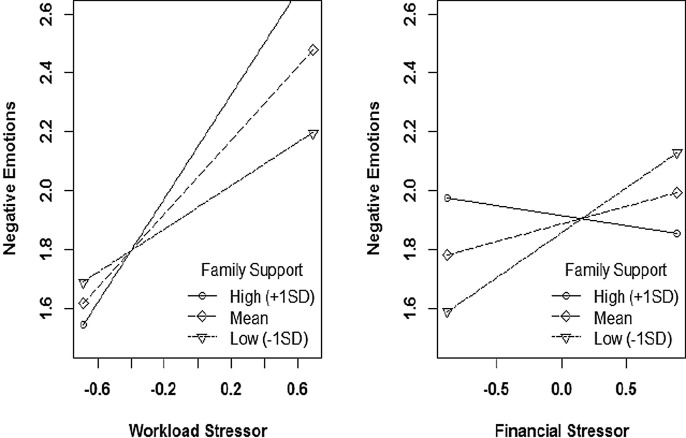

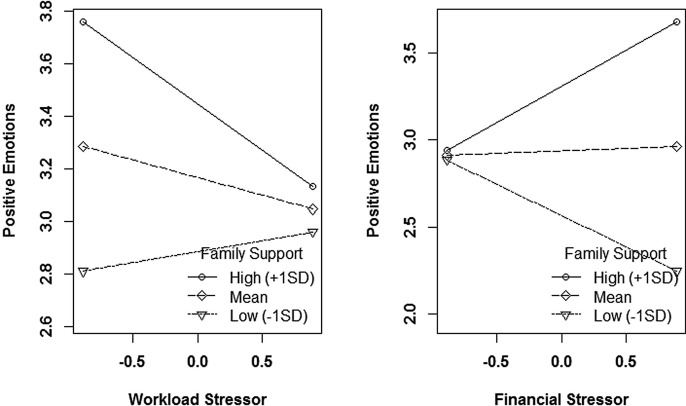

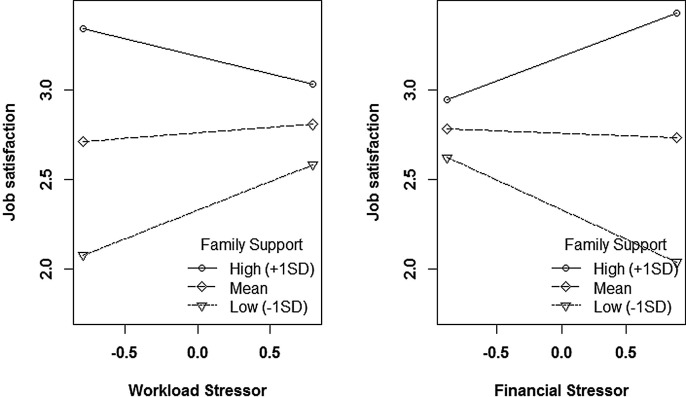

In terms of the economic exchange relationship, H1 and H2 argued for stress-buffering effects of perceived family support on the linkage between financial stressor and entrepreneurial well-being at the between- and within-person levels. As displayed in Table 2 , we found that perceived family support had a stress-buffering effect at the between-person level (positive emotion: b = 0.50, SE = 0.16, p < 0.01; negative emotion: b = -0.28, SE = 0.14, p < 0.05; job satisfaction: b = 0.39, SE = 0.15, p < 0.05). Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 demonstrate the interaction effects. The subsequent simple slope analyses showed that the linkages between the financial stressor and positive well-being indicators were negative at lower levels of family support (positive emotion: b = -0.36, p < 0.05; job satisfaction: b = -0.33, p < 0.005) and positive at higher levels of family support (positive emotion: b = 0.42, p < 0.05; job satisfaction: b = 0.27, p = 0.08). The linkage between financial stressor and negative emotions was positive at lower levels of family support (b = 0.35, p < 0.01) and negative at higher levels of family support (b = -0.08, p = 0.59). In comparison, we did not find any effects at the within-person level (see Table 2). Thus, H1 was fully supported and H2 was not.

Table 2.

Multilevel estimates for same-day effects of entrepreneurial stressors and family support on entrepreneurial well-being.

|

Positive emotions |

Negative emotions |

Job satisfaction |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

Model 7 |

Model 8 |

Model 9 |

|||||||||

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 3.21*** | 0.49 | 3.19*** | 0.48 | 2.94 | 0.43 | 1.82*** | 0.41 | 1.73*** | 0.39 | 1.89*** | 0.37 | 2.78*** | 0.44 | 2.92*** | 0.42 | 2.76*** | 0.39 |

| Control variables | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Gender | -0.08 | 0.20 | -0.12 | 0.19 | -0.19 | 0.17 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.16 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.15 | -0.00 | 0.17 | -0.02 | 0.17 | -0.08 | 0.16 |

| Marital status | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.12 | 0.20 | 0.05 | 0.18 | -0.14 | 0.17 | -0.18 | 0.16 | -0.13 | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 |

| Prior venture experience | 0.24 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.29† | 0.15 | -0.08 | 0.14 | -0.15 | 0.13 | -0.19 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.07 | 0.17 | 0.02 | 0.16 |

| Firm age | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.02 | -0.00 | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.02 | -0.03† | 0.02 | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.02 |

| Firm size | -0.00 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 | -0.02 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 |

| Time | -0.01** | 0.00 | -0.02*** | 0.00 | -0.02*** | 0.00 | -0.01** | 0.01 | -0.02** | 0.01 | -0.02** | 0.01 | -0.02*** | 0.01 | -0.02** | 0.01 | -0.02** | 0.01 |

| Main effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| Workload stressor (BP) | -0.05 | 0.13 | -0.01 | 0.12 | -0.15 | 0.11 | 0.38*** | 0.10 | 0.36*** | 0.10 | 0.44*** | 0.10 | 0.20† | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.11 | 0.07 | 0.11 |

| Financial stressor (WP) | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.12** | 0.03 | 0.12** | 0.04 | 0.13** | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Workload stressor (BP) | -0.07 | 0.09 | -0.07 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.08 | 0.16*** | 0.08 | 0.19* | 0.07 | 0.14† | 0.07 | -0.08 | 0.08 | -0.10 | 0.08 | -0.03 | 0.08 |

| Financial stressor (WP) | -0.03 | 0.04 | -0.02 | 0.04 | -0.03 | 0.04 | 0.16*** | 0.04 | 0.14** | 0.05 | 0.13* | 0.05 | -0.05 | 0.05 | -0.01 | 0.06 | -0.01 | 0.06 |

| Family support (BP) | 0.50*** | 0.11 | 0.56*** | 0.10 | 0.48*** | 0.11 | -0.01 | 0.09 | -0.01 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.58*** | 0.09 | 0.56 | 0.09 | 0.56*** | 0.10 |

| Family support (WP) | 0.32*** | 0.04 | 0.31*** | 0.06 | 0.31*** | 0.06 | -0.03 | 0.05 | -0.03 | 0.05 | -0.03 | 0.05 | 0.34*** | 0.05 | 0.37 | 0.06 | 0.37*** | 0.06 |

| Interaction effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| WS × FP (BP) | -0.67*** | 0.16 | 0.42** | 0.14 | -0.38* | 0.15 | ||||||||||||

| FS × FP (WP) | 0.11 | 0.06 | -0.06 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | ||||||||||||

| WS × FP (BP) | 0.50** | 0.16 | -0.28* | 0.14 | 0.39* | 0.15 | ||||||||||||

| FS × FP (WP) | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.09 | -0.08 | 0.11 | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intercept variance | 0.28 | 0.53 | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.22 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 0.43 | 0.16 | 0.40 | 0.20 | 0.45 | 0.21 | 0.46 | 0.18 | 0.42 |

| Slope variance (CS) | 0.02** | 0.15 | 0.02*** | 0.15 | 0.03** | 0.16 | 0.03† | 0.16 | 0.01 | 0.11 | 0.02† | 0.13 | ||||||

| Slope variance (HS) | 0.01** | 0.11 | 0.01*** | 0.11 | 0.02** | 0.15 | 0.02† | 0.15 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.02† | 0.15 | ||||||

| Slope variance (FP) | 0.07** | 0.26 | 0.07*** | 0.26 | 0.02** | 0.15 | 0.02† | 0.16 | 0.03 | 0.18 | 0.02† | 0.14 | ||||||

| Residual | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 0.49 | 0.34 | 0.58 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.31 | 0.57 | 0.46 | 0.68 | 0.44 | 0.66 | 0.44 | 0.66 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.27/0.65 | 0.30/0.70 | 0.39/0.70 | 0.26/0.52 | 0.25/0.55 | 0.29/0.56 | 0.25/0.48 | 0.24/0.50 | 0.27/0.50 | |||||||||

Note. SE = standard error; WS = workload stressor; FS = Financial stressor ; FP = family support BP = between-person; WP = Within-person. The right side of Pseudo-R2is the marginal R and the left side is the conditional R of the models. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; †p < 0.10.

Fig. 2.

The moderation effects of family support on the linkage between negative emotion and stressors Note. All the moderation effects are between-person moderation effects.

Fig. 3.

The moderation effects of family support on the linkage between positive emotion and stressors Note. All the moderation effects are between-person moderation effects.

Fig. 4.

The moderation effects of family support on the linkage between job satisfaction and stressors Note. All the moderation effects are between-person moderation effects.

In terms of the social exchange relationship, H3 argued for the amplifying effect for higher levels of perceived family support and the attenuating effect of lower levels of family support on the association between workload stressor and entrepreneurial well-being at the between-person level. In contrast, H4 argued for the opposite moderating effects in terms of higher vs. lower levels of family support at the within-person level. As shown in Table 2, we identified moderation effects only at the between-person level (positive emotion: b = -0.67, SE = 0.16, p < 0.001; negative emotion: b = 0.42, SE = 0.14, p < 0.01; job satisfaction: b = -0.38, SE = 0.15, p < 0.05). Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4 demonstrate the interaction effects. The simple slope analyses further consolidated the findings, except for negative emotions. The linkages between the workload stressor and positive well-being indicators were positive at lower levels of family support (positive emotion: b = 0.10, p = 0.49; job satisfaction: b = 0.36, p < 0.05) and negative at higher levels of family support (positive emotion: b = − 0.41, p < 0.05; job satisfaction: b = -0.23, p = 0.22). The linkage between workload stressor and negative emotions at both higher and lower levels of family support was positive (high: b = 0.79, p < 0.001; low: b = 0.33, p < 0.05). Hence, H3 received partial support and H4 was rejected.

5.3. Supplementary analyses

Since time is central to our theoretical model, we conducted two additional time-related analyses by considering the temporal precedence and temporal context. First, in relation to the temporal precedence, we explored the lagged relationships between variables (Deboeck & Preacher, 2015), which allows us to understand the causal effects in combination with the same-day effects. As shown in Table 3 , controlling for well-being on prior days, we identified some effects that were different from same-day effects for emotional well-being. For the positive emotion indicators, the interaction effects were almost the same, except for the within-person effects of family support for positive emotion and job satisfaction, suggesting that entrepreneurs who perceived higher levels of family support on the previous day felt an enhanced sense of positive well-being the next day. In relation to negative emotions, we did not identify within-person effects of either financial or workload stressor, indicating that stressors experienced on a prior day did not exert lingering effects on the next day’s negative emotions. We did not find a stress-buffering effect of family support on the relationship between financial stressor and negative emotions. Therefore, we conclude that the between-person effects are stronger than the within-person effects in all of the examined relationships.

Table 3.

Multilevel estimates for lagged effects of entrepreneurial stressors and family support on entrepreneurial well-being.

|

Positive emotions |

Negative emotions |

Job satisfaction |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Model 1 |

Model 2 |

Model 3 |

Model 4 |

Model 5 |

Model 6 |

Model 7 |

Model 8 |

Model 9 |

|||||||||

| b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | b | SE | |

| Fixed effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intercept | 2.60*** | 0.41 | 2.53*** | 0.40 | 2.38*** | 0.36 | 1.39*** | 0.31 | 1.42*** | 0.31 | 1.56*** | 0.30 | 2.22*** | 0.35 | 2.28*** | 0.34 | 2.16*** | 0.33 |

| Control variables | ||||||||||||||||||

| Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 |

| Gender | -0.12 | 0.16 | -0.13 | 0.15 | -0.21 | 0.14 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.12 | -0.06 | 0.13 | 0.06 | 0.13 | -0.02 | 0.13 |

| Marital status | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.14 | -0.06 | 0.13 | -0.04 | 0.13 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.07 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.07 | 0.13 |

| Prior venture experience | 0.17 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.13 | 0.25* | 0.12 | -0.06 | 0.10 | -0.04 | 0.10 | -0.09 | 0.10 | 0.10 | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.11 |

| Firm age | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.02 | 0.02 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 | -0.03† | 0.01 | -0.03† | 0.01 | -0.02† | 0.01 |

| Firm size | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.01 | 0.00 |

| Time | -0.01 | 0.01 | -0.01† | 0.01 | -0.01† | 0.01 | -0.01† | 0.01 | -0.01† | 0.01 | -0.01* | 0.01 | -0.02** | 0.01 | -0.02** | 0.01 | -0.02** | 0.01 |

| Prior day’s well-being | 0.16*** | 0.04 | 0.18*** | 0.04 | 0.19*** | 0.04 | 0.25*** | 0.04 | 0.24*** | 0.04 | 0.24*** | 0.04 | 0.20*** | 0.04 | 0.21*** | 0.04 | 0.20*** | 0.04 |

| Main effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| Workload stressor (BP) | -0.04 | 0.10 | -0.04 | 0.10 | -0.15† | 0.09 | 0.29*** | 0.08 | 0.30*** | 0.08 | 0.37*** | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.09 | 0.13 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 0.08 |

| Financial stressor (WP) | 0.06† | 0.03 | 0.07† | 0.04 | 0.07* | 0.04 | -0.02 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.04 | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.01 | 0.04 | -0.00 | 0.04 | -0.01 | 0.04 |

| Workload stressor (BP) | -0.04 | 0.07 | -0.03 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.16** | 0.06 | 0.16** | 0.06 | 0.12* | 0.06 | -0.05 | 0.06 | -0.06 | 0.06 | -0.00 | 0.06 |

| Financial stressor (WP) | 0.07† | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.04 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.06 |

| Family support (BP) | 0.39*** | 0.09 | 0.38*** | 0.09 | 0.32*** | 0.09 | -0.00 | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.43*** | 0.08 | 0.44*** | 0.08 | 0.45*** | 0.09 |

| Family support (WP) | 0.02 | 0.05 | -0.02 | 0.06 | -0.01 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.05 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.07 | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.03 | 0.07 |

| Interaction effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| WS × FP (BP) | -0.52*** | 0.13 | 0.31** | 0.11 | -0.28* | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| FS × FP (WP) | -0.07 | 0.07 | 0.14† | 0.11 | 0.04 | 0.09 | ||||||||||||

| WS × FP (BP) | 0.40** | 0.13 | -0.16 | 0.11 | 0.31* | 0.12 | ||||||||||||

| FS × FP (WP) | 0.05 | 0.10 | -0.13 | 0.11 | -0.02 | 0.13 | ||||||||||||

| Random effects | ||||||||||||||||||

| Intercept variance | 0.16 | 0.41 | 0.15 | 0.39 | 0.12 | 0.34 | 0.08 | 0.28 | 0.08 | 0.29 | 0.07 | 0.27 | 0.10 | 0.31 | 0.10 | 0.32 | 0.09 | 0.29 |

| Slope variance (CS) | 0.01 | 0.09 | 0.01** | 0.09 | 0.01 | 0.12 | 0.07* | 0.27 | 0.00 | 0.04 | 0.00 | 0.07 | ||||||

| Slope variance (HS) | 0.00 | 0.05 | 0.00** | 0.05 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.02* | 0.13 | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.02 | 0.14 | ||||||

| Slope variance (FP) | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.05** | 0.22 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 0.01* | 0.09 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.03 | 0.17 | ||||||

| Residual | 0.29 | 0.54 | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.52 | 0.37 | 0.61 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 0.60 | 0.49 | 0.70 | 0.48 | 0.69 | 0.47 | 0.69 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.29/0.55 | 0.30/57 | 0.39/0.58 | 0.30/0.43 | 0.29/0.44 | 0.26/0.38 | 0.26/0.40 | 0.29/0.41 | ||||||||||

Note. SE = standard error; WS = workload stressor ; FS = Financial stressor; FP = family support BP = between-person; WP = Within-person. The right side of Pseudo-R2is the marginal R and the left side is the conditional R of the models. * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; †p < 0.10.

Our data set covered two consecutive weeks for each variable so that we could conduct tests to determine whether weekdays and weekends, treated as temporal contexts, had different effects on the examined relationships. Because a majority of entrepreneurs engage in entrepreneurial activities over the whole week, we estimated additional models to explore whether the variable of the weekend moderated the main effects and whether there was a three-way interaction between weekend, entrepreneurial stressors, and family support. We identified two three-way interactions: the interaction between weekend, workload stressor, and family support at the between-person level for positive emotion (b = -0.20, SE = 0.10, p < 0. 05) and the same interaction effect at the within-person level for job satisfaction (b = 0.42, SE = 0.17, p < 0.05). Fig. 5 illustrates that there was little difference at the between-person level for positive emotion. With regard to the effect at the within-person level for job satisfaction, weekend and weekday effects differed in direction. Entrepreneurs who perceived higher levels of family support were more satisfied with their jobs on days of higher levels of workload stressor, demonstrating the impact of weekend and weekday effects at the within-person level. After testing the weekend effects in lagged models using the same steps, we identified a three-way interaction between weekend, family support/workload stressor, and job satisfaction at the between-person level, which differed only slightly.

Fig. 5.

The three-way interactions among workload stressor, family support and weekend Note. The upper panel is between-person moderation effect and the lower panel is within-person moderation effects.

6. Discussion

Prior studies have yielded inconclusive results concerning the impact of family embeddedness (family support or capital) on entrepreneurship. Thus, taking a time-based and temporal perspective, we theorize how entrepreneurs’ perceived family support can moderate the associations between entrepreneurial stressors (economic vs. workload) and entrepreneurial well-being in economic and social exchange processes at both the between- and within-person levels. Although we found only between-person effects, the advantage of the combination of between- and within-person approaches offers a better and more coherent understanding of the function of individual differences in the relationships of these constructs by acknowledging both enduring structures and dynamic processes in family embeddedness. Perceived family support has different moderating effects (stress-buffering and stress-amplifying) on the associations between different stressors and well-being. Results align with the assumptions relative to different interpersonal exchange contexts.

6.1. Theoretical implications

Our study has important theoretical implications for the entrepreneurship research. First, we demonstrate that the positive and negative consequences of family support on entrepreneurial well-being depend on the nature of the relationship context (economic vs. social exchange) under corresponding entrepreneurial contexts. In this respect, our study should add some clarity to the mixed roles of family embeddedness in entrepreneurial processes and outcomes (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, Jennings and McDougald, 2007). Specifically, in relation to economic exchange relationships, results reveal that family support can attenuate the negative effects of financial stressors on well-being in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives, which further confirms that family support plays a pivotal role in facilitating nonpecuniary entrepreneurial success (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Although prior studies have suggested that family support or capital can impede entrepreneurial actions (e.g., establishing ventures) (Sieger & Minola, 2017), we show that entrepreneurs might have positive relational responses and that these effects might change in terms of the relationship context. That is, family support is conducive to entrepreneurs who are exposed to financial stressors when this support is matched to economic contexts rather than to general entrepreneurial contexts. Hence, it is important to theorize both how entrepreneurs and family members make exchanges and on what benefit the exchange is based (Cropanzano and Mitchell, 2005, Cropanzano et al., 2017).

In regard to social exchange relationships, our findings suggest that different levels of family support (high vs. low) exert mixed influences on entrepreneurial well-being under the context of the daily workload. Consistent with our assumptions, higher levels of family support entail negative consequences for entrepreneurs who are exposed to workload stressors whereas lower levels of family support show opposite effects (especially for positive emotion and job satisfaction), further proving that entrepreneurs do not desire their family members’ interference in their business affairs but demand more autonomy (Arregle et al., 2015, Hsu et al., 2016). Thus, we move beyond prior studies by illustrating that the ambiguous consequences of family embeddedness might be explained by matched family relationship contexts. Embedded in social exchange contexts, our theorizing shifts the important conversation of family embeddedness theory to consider how a specific entrepreneurial context may cultivate different family relationships that lead to distinct types of responses.

Second, we extend prior studies that are exclusively based on cross-sectional and time-invariant designs by taking a time-based and temporal approach, which offers a theoretical framework to explain family embeddedness and entrepreneurship as a dynamic process (Aldrich and Cliff, 2003, McMullen and Dimov, 2013). Further, rather than solely examining within-person processes (favored in temporal studies), we explored both between- and within-person patterns of effects that are equally central to understanding the role of time in interpreting organizational phenomena (Shipp & Cole, 2015). Only the between-person hypotheses, however, were supported, perhaps because family support does not function in a timely manner but remains neutral on days when entrepreneurs deal with particularly complex business issues. Another possible explanation is that the resources provided by family members are not as effective in fluctuating entrepreneurial situations (e.g., stressors) as are substitutes for other supportive resources. Thus, the null findings regarding within-person relationships provide another perspective of explicating the mixed roles of family support based on situations, while the identification of between-person relationships further illustrates the importance of understanding general individual differences in the effects of family support over time. Moreover, our results are also consistent with a meta-analysis showing that the between-person effects of the job stress–strain process are stronger than the within-person effects in dairy studies (Pindek, Arvan & Spector, 2019).

We believe that our within-person findings are valuable based on our evidence of entrepreneurs’ real-life stressful experiences and the resulting well-being effects. The findings of the lagged model and tests of the weekend effect further support the notion that we should seriously consider the effects of time and within-person effects on the microfoundation of the entrepreneurial process (Levesque and Stephan, 2020, Shepherd, 2015). To understand the theoretical processes in entrepreneurial contexts, scholars can continue drawing on between- and within-person theorizing to formulate nuanced hypotheses and develop compelling rationales for why processes across levels are either different or similar (Uy et al., 2010, McCormick et al., 2020).

Third, our study provides insights into how Western-based theoretical models can be applied to an emerging economy (China), prompting scholars to consider the necessity of theory refinement and development across different entrepreneurial contexts (Bruton et al., 2018). Our theoretical framework puts a strong emphasis on the important and mixed role of family relationships that shape entrepreneurs’ perceptions of subjective venture success (e.g., Au and Kwan, 2009, Pistrui et al., 2001). Thus, connecting the local phenomenon to the global perspective of the family embeddedness theory in entrepreneurial contexts has important implications for indigenous theory development (Bruton et al., 2018, Su et al., 2015). We, therefore, hope to inspire future studies to shift from theory application to the next contexts to the incorporation of the specific context into theory development (Su et al., 2015). For instance, boundary conditions (e.g., institutional and cultural factors) (Castaño et al., 2015, Ge et al., 2019) should be added to existing theoretical models.

6.2. Practical implications

Our study has practical implications for entrepreneurs regarding their relationship with family members. Results suggest that family support has both positive and negative impacts on the regulation of stressful situations and entrepreneurial well-being. Entrepreneurs who can fully utilize their family resources or turn to family members for business advice and emotional reassurance in times of need are much better able to manipulate their well-being. Indeed, it is important for entrepreneurs to recognize the critical supportive function of the family background and family members regarding the context of relationships. Family members should avoid providing support that does not meet entrepreneurs’ needs, such as interfering with business affairs on entrepreneurs’ usual workdays. Entrepreneurs and family members should engage in interpersonal exchange processes that are matched to the entrepreneurial contexts.

Entrepreneurs who are constantly exposed to entrepreneurial stressors should be aware of the situation-specific and time-varying characteristics of these stressors and learn how to manage and actively cope with different types of stressors by taking advantage of family support. Given that the ultimate goal of engaging in entrepreneurship is to maintain lifelong well-being (Stephan, 2018), entrepreneurs are encouraged to appraise stress and develop stress management techniques based on fluctuating situations and the availability of family support. Reappraising and effectively managing entrepreneurial stressors are not only beneficial to entrepreneurial well-being but also help to maintain the relational balance between family members and entrepreneurs.

While our study predates the pandemic caused by Covid-19, entrepreneurial stress and its interrelationships with family support are probably more salient than ever. Strong family support may help entrepreneurs to successfully weather the current adverse environmental circumstances to keep positive emotions and overall job satisfaction high. It is important not only that the entrepreneur is aware of the potential positive effects from their family, but also that the family is made aware of the important support function it can provide.

6.3. Limitations and future research

Given that social exchange relationships frequently occur between entrepreneurs and their family members, collecting data from a single source (the entrepreneur)might lead to common method variance. Future studies might consider assessing entrepreneurs’ family members to examine the impact of family relationships on entrepreneurs’ daily work lives. Because family embeddedness can be constructed in different forms, such as family capital (Edelman et al., 2016) or family ties (Arregle et al., 2015), other types of constructs in both social and economic exchange relationships should be considered.

Second, assessing the variables repeatedly in this context (i.e., 61 entrepreneurs over a two-week period) created challenges. For instance, emotions and job satisfaction are regarded as dynamic and fluctuating affective and cognitive components of well-being, which could be measured multiple times within a day or within other time frames (Foo et al., 2009). Because entrepreneurs experience considerable time constraints, capturing these variables in entrepreneurial contexts is particularly challenging. Therefore, we utilized brief measures that have the potential for slightly lower but still acceptable reliability (Uy et al., 2010). Scholars may consider using longer time lags (months, years) and a variety of samples across different entrepreneurial stages (e.g., incubation) to test the between-person differences and within-person fluctuations over time.

Third, although our study advances our understanding of the impact of the joint effects of daily stressors and family support on entrepreneurial well-being, researchers could focus on additional antecedents, consequences, and entrepreneurial outcomes (e.g., behavioral) concerning the between- and within-person effects in the hypothesized relationships. For example, we need to better understand the potential reciprocal relationships between entrepreneurial stressors and family support, as well as how these relationships evolve and change over time. Alternatively, it is necessary to understand whether entrepreneurs can provide equal amounts of support to family members, either in the form of economic returns or emotional support, so that we can examine the supportive reciprocity mechanism between them. This entails important implications for the mixed roles of family embeddedness in entrepreneurs’ relational and behavioral outcomes and even firm-level outcomes. Again, the timing and potential accumulation of the effects over time are important to consider.

Fourth, although the between- and within-person theorizing relative to testing the theoretical framework is widely generalizable in entrepreneurial contexts (Uy et al., 2010), we conducted empirical analyses with a sample of Chinese entrepreneurs, who may be subject to unique institutional and cultural influences (e.g., Castaño et al., 2015). Hence, we suggest that these social exchange relationships deserve further theory development and empirical investigation across cultural contexts or emerging and mature economies. In addition, given that we test the theoretical framework with a group of Chinese entrepreneurs, our empirical results might not be generalizable to entrepreneurs residing in other economies (e.g., U.S., Europe), as entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial actions are affected by the social, cultural, and economic factors within specific countries (e.g., Castaño et al., 2015, Fritsch et al., 2019). While management systems and approaches have become more similar across countries (Carr, 2005) and this attenuates the generalizability concerns, we would still encourage future research to conduct a cross county study with explicitly taking the effect of social, cultural, and economic variables into account that could be theoretically related to the well-being effects. For example, unemployment rates, corruption perceptions, or the GEI (global entrepreneurs index), which is a comprehensive measure of the quality of a country's entrepreneurship ecosystem (Acs et al., 2017) could be by useful areas to investigate.

Finally, we demonstrated the importance of family support for entrepreneurs. These findings may be even more relevant during the Covid-19 pandemic, a drastically changing environment that offers numerous potential future research opportunities. First, other salient family-related variables could be investigated, such as family-work conflict (e.g., Carr & Hmieleski, 2015). In addition, other factors related to the ability to deal with stress could be investigated; for example, entrepreneurial resilience (e.g., Santoro et al., 2020), grit, (Duckworth & Quinn, 2009), or entrepreneurial passion (e.g., Cardon et al., 2009), which could generate important insights to better understand entrepreneurial stressors and satisfaction levels when entrepreneurs are faced with severe economic downturns or other catastrophic impacts.

7. Conclusion

There is no doubt that in the entrepreneurial process, family relationships are important resources for entrepreneurs. Through integrating the family embeddedness theory and the social exchange relationships framework, our study demonstrates the mixed impact of family support on entrepreneurial well-being across different stressful contexts (stress-attenuating or stress-amplifying effects) depending on the nature of interpersonal exchange relationships (economic vs. social). Notably, these effects are mainly manifested at the between-person level in entrepreneurs’ daily work lives. By limiting our empirical analyses to Chinese entrepreneurs, we might have neglected to consider how specific cultural, social, and economic factors can shape these familial relationships. We suggest that future studies should incorporate context-specific theoretical concepts into the hypothesized relationships by considering time-based and multilevel approaches.

Biographies

Feng Xu is an assistant Professor at the College of Economics and Management, South China Agricultural University. His research focuses on the stress-coping processes and the well-being effects in entrepreneurial contexts. He has published papers in Psychological Assessment, Journal of Family Psychology, International Journal of Psychology, International Journal of Stress Management and Journal of Happiness Studies.