Abstract

Despite widespread use of the Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; E. M. Mullen, 1995) as a cognitive test for children with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities, the instrument has not been independently validated for use in these populations. Convergent validity of the MSEL and the Differential Ability Scales (DAS; C. D. Elliott, 1990, 2007) was examined in 53 children with autism spectrum disorder and 19 children with nonspectrum diagnoses. Results showed good convergent validity with respect to nonverbal IQ(NVIQ), verbal IQ(VIQ), and NVIQ–VIQ profiles. These findings provide preliminary support for the practice of using MSEL age-equivalents to generate NVIQ and VIQ scores. Establishing convergent validity of cognitive tests is needed before IQs derived from different tests can be conceptualized as a uniform construct.

Diagnostic assessment of autism spectrum disorders relies on the use of parent-report and direct-observation instruments to measure impairments in reciprocal social interaction and communication and the presence of restricted and repetitive behaviors and interests (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In addition to measures of core symptoms of autism spectrum disorders, a complete diagnostic battery also includes tests of cognitive abilities (i.e., IQ) and language skills (see Gotham, Bishop, & Lord, 2011). This information is useful not only in recommending appropriate intervention and educational goals, but it is also necessary to accurately interpret the child’s level of social and communicative impairment in relation to other abilities. A 6-year-old child with an intellectual disability would not be expected to exhibit the same level of social ability as a 6-year-old child with above-average intelligence. Therefore, diagnosticians must not underestimate the importance of cognitive testing as a routine component of diagnostic assessment for autism spectrum disorders.

Cognitive testing also serves an important role in research protocols for autism spectrum disorders. Individuals with autism spectrum disorders vary widely with respect to intellectual ability (Fombonne, 2005), and IQ has been found to be one of the most robust predictors of response to intervention (e.g., Harris & Handleman, 2000; Smith, 1999) and long-term outcomes in these individuals (Billstedt & Gillberg, 2005; Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2004). IQ also plays a central role in the manifestation of core and associated symptoms in autism spectrum disorders (Bishop, Richler, & Lord, 2006; Borden & Ollendick, 1994; Carpentieri & Morgan, 1996; Coplan &Jawad, 2005; Estes, Dawson, Sterling, & Munson, 2007; Fein et al., 1999; Sevin et al., 1995; Volkmar, Cohen, Bregman, Hooks, & Stevenson, 1989), and it is associated with risk of comorbid conditions such as epilepsy (Gillberg & Steffenburg, 1987). Recently, some authors have proposed that IQ profiles could be used to organize children with autism spectrum disorders into different phenotypic subtypes (Joseph, Tager-Flusberg, & Lord, 2002; Munson et al., 2008).

One of the challenges associated with evaluating IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders is determining which test(s) to use. Measures commonly used in typically developing populations, such as the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th ed.; WISC; Wechsler, 2003) or the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (3rd ed.; WPPSI; Wechsler, 2002), may not always be appropriate for children with developmental disabilities because of the high language demands of these instruments. Tests that combine verbal and nonverbal reasoning into a single score, such as earlier editions of the Bayley Scales of Infant Development (BSID; Bayley, 2005), have also presented significant limitations. Individuals with autism spectrum disorders often exhibit large discrepancies between verbal and nonverbal IQ (Joseph et al., 2002), and, thus, an overall IQ score may not be meaningful. Another problem related to assessing IQ in children with developmental disabilities in general is that there have been few empirical investigations to establish the psycho-metric properties of standardized cognitive tests in these individuals. Validation samples for most intelligence tests are composed almost entirely of typically developing children (Roid, 2003; Wechsler, 2003), which raises questions about whether the tests perform similarly in atypical populations. Particularly among children with intellectual disabilities, it should not be assumed that scores at the very low end of the scale (which are largely extrapolated based on assessments of typically developing children) provide valid estimates of cognitive ability.

In many cases, it is not even possible to derive standard scores for children with intellectual disabilities or developmental delays because the child is outside of the standard age range for which the test was developed or because the child’s raw scores are below the lowest scores for which standard scores are provided. In these cases, researchers and clinicians may rely on age equivalents or ratio IQs (i.e., “mental age” divided by chronological age). However, the extent to which these scores correspond to standard IQ scores is not well understood.

The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL; Mullen, 1995) is a developmental test for young children that is less commonly mentioned in the general child assessment literature but frequently used in research and clinical evaluations of children with autism spectrum disorders. Given increasing interest in the early identification and early development of young children with autism spectrum disorders, the MSEL is now commonly used as a measure of cognitive and/or language skills in research protocols (e.g., Chawarska, Klin, Paul, & Volkmar, 2007; Dawson et al., 2009; Landa & Garrett-Mayer, 2006; Werner, Dawson, Munson, & Osterling, 2005; Zwaigenbaum et al., 2007). It has also been used in longitudinal investigations of children with autism spectrum disorders (Lord et al., 2006) and has been selected as one of the preferred IQ measures in multisite collaborative projects, such as the Simons Simplex Collection (see https://sfari.org/simons-simplex-collection).

The MSEL was originally designed to yield a single standard score, the Early Learning Composite (ELC), although many researchers have adopted the practice of using age-equivalent scores from the MSEL scales to derive ratio IQ scores that provide separate estimates of verbal IQ (VIQ and nonverbal IQ (NVIQ e.g., Richler, Bishop, Kleinke, & Lord, 2007). The MSEL manual reports good internal, test-retest, and interrater reliabilities, as well as good convergent validity with the BSID. The internal consistency for the ELC is high, suggesting that the ELC can be used as an as overall measure of cognitive functioning. Nevertheless, a systematic review of cognitive testing in young children noted the lack of independent studies to support the predictive, concurrent, or construct validity of the MSEL (Bradley-Johnson, 2001).

Information about convergent validity with more established measures of IQ is needed to justify use of the MSEL in research studies, particularly those in which the MSEL is used in conjunction with other cognitive tests. The MSEL only assesses skills within a relatively narrow range of development (1–68 months), so studies that include children across a wider range of age and ability must use other tests in addition to the MSEL to obtain IQ scores for everyone in the sample. However, the validity of analyzing MSEL scores with scores obtained from other tests of cognitive ability has not been assessed. It is not clear whether the MSEL yields similar results as these other tests. In addition, it has not been empirically established that non-verbal and verbal ratio IQ scores (extrapolated from MSEL age-equivalent scores) correspond to standardized measures of VIQ and NVIQ.

In the current study, we evaluated the convergent validity of nonverbal and verbal ratio IQ scores on the MSEL compared with standard scores obtained simultaneously on the Differential Ability Scales (DAS; Elliott, 1990). Like the MSEL, the DAS has been used to assess cognitive abilities in several studies of children with autism spectrum disorders (e.g.,Joseph et al., 2002; Sherer & Schreibman, 2005; Sutera et al., 2007). In the current study we used the first edition of the DAS, although a second edition (the DAS-II; 2007) has recently been released. The DAS can be administered to children between the ages of 30 months and 17 years, 11 months. The Preschool Form is intended for children up to the age of 6 years, 11 months, and the School-Age Form is administered to children 7 years and older. The DAS manual supports the internal, test-retest, and interrater reliabilities of this measure and reports strong convergent validity with the WPPSI, WISC, and Stanford-Binet 4 (Thorndike, Hagen, & Sattler, 1986). Independent investigations have also reported good convergent validity with the WISC in typically developing children (Byrd & Buckhalt, 1991) and in children with learning disabilities (Dumont, Cruse, Price, & Whelley, 1996). Because the DAS is a more established measure of cognitive functioning that has also shown high agreement with other well-established intelligence tests, it provides a metric against which to evaluate the validity of the MSEL as a measure of NVIQ and VIQ.

Method

Data for this project were obtained from a large existing database of participants seen through various research projects or clinic assessments at the University of North Carolina, University of Chicago, and University of Michigan. Participants with autism spectrum disorders were recruited and referred from local physicians and community organizations or self-referred if parents had concerns regarding their child’s development. Participants with diagnoses other than autism spectrum disorders were either seen through a clinic specializing in assessment of autism spectrum disorders or were recruited specifically as control participants for research studies.

Participants

Participants were selected from the database if they had completed both the MSEL and the DAS during a single diagnostic assessment. Because this study was concerned with investigating the psychometric properties of the MSEL, the sample was limited to children who were within the standard age range for administration of the test (i.e., between 1 and 68 months). At the time of testing, children ranged in age from 2 years, 8 months to 5 years, 7 months, with a mean of just over 4 years. Demographics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics

| Variable | Participant category | |

|---|---|---|

| Autism spectrum disorder | Non-autism spectrum disorder | |

| (n = 53): n (%) | (n = 19): n (%) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 44 (83) | 12 (63) |

| Female | 9 (17) | 7 (37) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Caucasian | 43 (81) | 15 (79) |

| African American | 4 (7) | 4(21) |

| Asian American | 2 (4) | 0 |

| Biracial | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Other/Unknown | 3 (6) | 0 |

| Age at assessment in months (SD) | 50.00 (8.99) | 48.21 (8.85) |

| Site | ||

| North Carolina | 22 (42) | 17 (89) |

| Chicago | 21 (39) | 0 |

| Michigan | 10 (19) | 2 (11) |

There were different reasons why children in the sample would have received both tests as part of their assessment. Approximately half of participants in this sample were seen through the Early Diagnosis Study (EDX Study; see Lord et al., 2006 [Autism 2–9]). During the early waves of data collection for this study, the standard research protocol involved administration of both the MSEL and the DAS for participants who were capable of completing both tests. Other participants were seen through clinic evaluations at the University of Chicago or the University of Michigan. Whenever possible (e.g., when time allows, when the child is not too fatigued), standard protocol for diagnostic assessments conducted at these clinics involved administering two different IQ tests to obtain two separate estimates of NVIQ and VIQ.

Assessments were conducted by clinical psychologists or advanced clinical psychology graduate student trainees. The order in which the tests were administered was not regulated but was instead left up to the clinician to determine. Unfortunately, information about test order was not systematically documented and is, therefore, not available for the current study. However, given that different clinicians were involved in conducting these assessments and that the particular order of tests was not specifically legislated, we assume that the order of the two tests varied nonsystematically across participants. All but 2 of the children were administered the MSEL and the DAS during the same appointment (i.e., on the same day). The 2 remaining children completed the tests within 1 month of each other.

In total, 72 participants met the study criteria, but not all participants in the sample had NVIQ and VIQ scores from both measures. NVIQ data were available for 51 participants, and VIQ data were available for 62 participants. Because these participants were seen for assessments over the course of several years (between 1992 and 2006), they received slightly different versions of the MSEL. Whereas some children received the original version of the MSEL, others received the more recently revised version published in 1995. The test items on the two versions are highly similar, but the revised MSEL includes expanded norms and changes in the way that basals and ceilings are determined (Mullen, 1995). In the current study, 61% of participants received the original edition of the MSEL and 39% were administered the revised version. A second edition of the DAS (the DAS-II) is also now available, but all participants in the current study received the first edition. Because of their young age, all participants completed the Preschool Form of the DAs.

Diagnoses of autism spectrum disorders or another disorder, such as language delay or intellectual disability, were assigned by experienced clinicians. Clinical diagnoses incorporated information from the Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised (ADI-R: Rutter, Le Couteur, & Lord, 2003), the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS: Lord, Rutter, DiLavore, & Risi, 1999), and developmental histories and record reviews.

Calculation of IQ Scores

Both the MSEL and the DAS yield standardized, norm-referenced scores for full-scale IQ. However, unlike the DAS, the MSEL does not provide separate standard scores for NVIQ and VIQ. To calculate separate NVIQ and VIQ scores from the MSEL, ratio IQs (i.e., developmental quotients) were derived using age-equivalent scores. For NVIQ, age-equivalent scores from the Fine Motor and Visual Reception domains were averaged, divided by the child’s chronological age, and multiplied by 100. For VIQ, age-equivalent scores from the Receptive Language and Expressive Language domains were averaged, divided by the child’s chronological age, and multiplied by 100. All NVIQ and VIQ scores reported from the MSEL are ratio IQs based on age equivalents. NVIQ and VIQ scores reported from the DAS are standardized, norm-referenced IQ scores.

Results

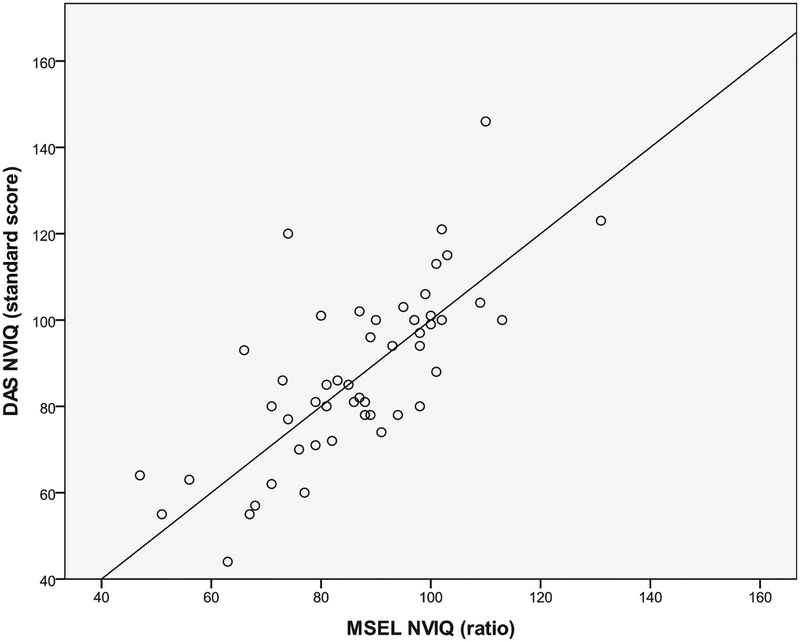

Nonverbal IQ

NVIQ scores on the MSEL were similar to NVIQ scores on the DAS. A paired samples t test indicated that NVIQ scores on the MSEL were not significantly different from NVIQ scores on the DAS, t(50) = 0.56, p = 0.58. Scores on the two tests were correlated at .74 (df = 49, p < .01; see Figure 1). As seen in Table 2, the average absolute difference between MSEL and DAS scores was 10.20 points (SD = 8.85), ranging from 0 to 46 points. The majority of children (77%) received MSEL NVIQ scores that were within 1 standard deviation (i.e., 15 IQ points) of their DAS NVIQ scores. For a subgroup of children, discrepancies between NVIQ scores on the MSEL and the DAS were larger. Five children (10%) received DAS scores that were between 1 and 2 standard deviations higher than their MSEL scores, 5 children (10%) received DAS scores that were between 1 and 2 standard deviations lower than their MSEL scores, and 2 children (4%) received DAS scores that were more than 2 standard deviations higher than their MSEL scores. For example, 1 child received a 74 on the MSEL and a 120 on the DAS (difference of 46 IQ points). Another child received an MSEL score of 63 and a DAS score of 44 (difference of 19 points).

Figure 1.

MSEL and DAS NVIQ score correlation. The line is provided as a reference line and does not represent a regression line. MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995); DAS = Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 1990); NVIQ = nonverbal IQ.

Table 2.

IQ Descriptive Statistics

| Test and statistic | M | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| NVIQ (n = 51) | |||

| MSEL ratio NVIQ | 86.69 | 16.23 | 47–131 |

| DAS deviation NVIQ | 87.75 | 19.96 | 44–146 |

| Absolute NVIQ score difference (DAS-MSEL) | 10.20 | 8.85 | 0–46 |

| VIQ (n = 62) | |||

| MSEL ratio VIQ | 72.76 | 16.42 | 43–110 |

| DAS deviation VIQ | 74.35 | 15.04 | 50–115 |

| Absolute VIQ score difference (DAS-MSEL) | 7.89 | 5.27 | 0–23 |

Note. NVIQ = nonverbal IQ; MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995); DAS = Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 1990); VIQ = verbal IQ.

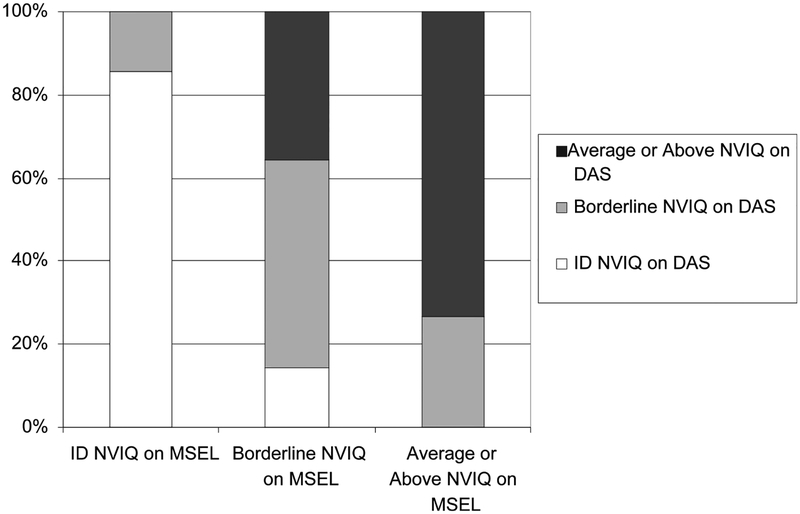

We also examined the number of children whose NVIQ scores on the MSEL fell in a different range of cognitive ability (i.e., average-above average, borderline, intellectual disability) than their scores on the DAS. As seen in Figure 3, 69% of children scored in the same cognitive range on both measures. For the majority of cases in which range differences were observed, the child had received a score on one instrument that was in the borderline-low-average range (IQ = 70–85) and a score on the other instrument that was in either the average range (>85) or range of intellectual disability (<70): for example, receiving a score of 73 on the MSEL and a score of 86 on the DAS or a score of 71 on the MSEL and a score of 62 on the DAS. There was only 1 case in which NVIQ scores differed across more than one cognitive ability range—this child received a score in the range of intellectual disability on the MSEL (NVIQ 5 66) and a score in the average range on the DAS (NVIQ = 93).

Figure 3.

NVIQ cognitive range classifications on the MSEL and the DAS. NVIQ = nonverbal IQ; MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995); DAS = Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 1990).

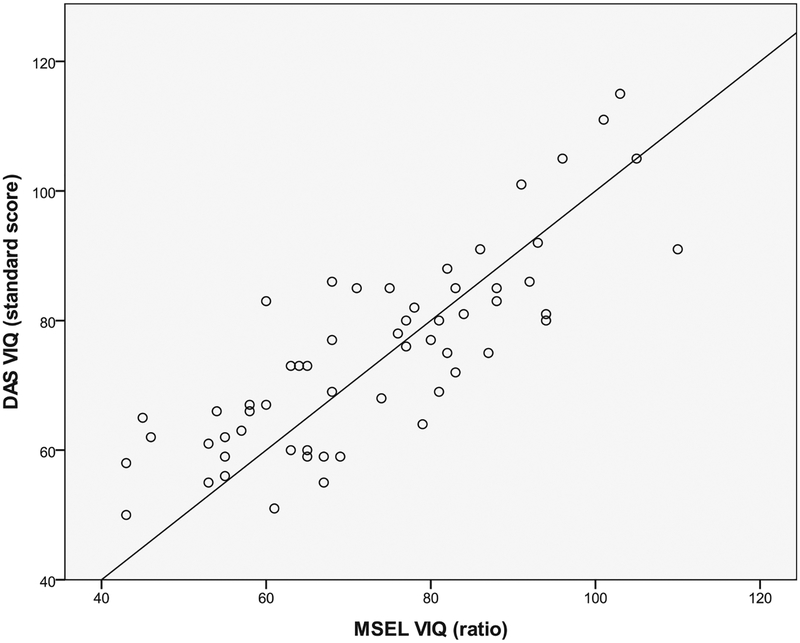

Verbal IQ

VIQ scores on the MSEL were also not significantly different than VIQ scores on the DAS, t(61) = 1.34, p = 0.19. VIQ scores on the two tests were correlated at.83 (df = 60, p < .01; see Figure 2). As seen in Table 2, the average absolute difference between MSEL and DAS scores was 7.89 points (SD = 5.27), ranging from 0 to 23 points. Most children (89%) received DAS scores that were within 1 standard deviation of their scores on the MSEL, 5 children (8%) received DAS scores that were between 1 and 2 standard deviations higher than their MSEL scores, and 2 children (3%) received DAS VIQ scores that were between 1 and 2 standard deviations lower than their MSEL VIQ scores. No one received VIQ scores on the tests that differed by 2 or more standard deviations.

Figure 2.

MSEL and DAS VIQ score correlation. The line is provided as a reference line and does not represent a regression line. MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995); DAS = Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 1990); VIQ = verbal IQ.

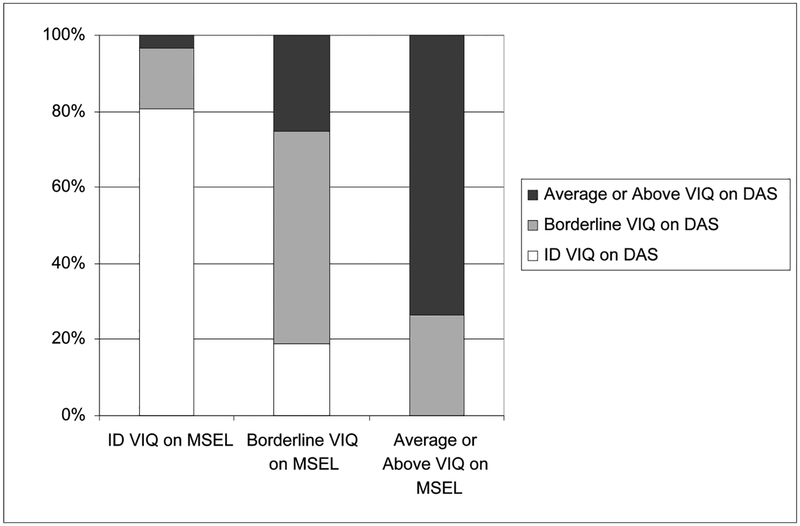

As was the case with NVIQ, the majority of children (73%) received scores in the same range of cognitive ability on both measures (see Figure 4). Sixteen children (26%) scored in the borderline-low-average range on one instrument and in either the intellectual disability or average range on the other instrument. One child received an MSEL score of 68 in the intellectual disability range and a DAS score of 86 in the average range.

Figure 4.

VIQ cognitive range classifications on the MSEL and the DAS. VIQ = verbal IQ; MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995); DAS = Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 1990).

Variables Associated With Absolute Score Differences

We were interested in exploring whether certain variables were associated with larger absolute differences (i.e., the magnitude of difference in scores, not accounting for positive versus negative differences) between scores on the MSEL and scores on the DAS. For NVIQ and VIQ, absolute score discrepancies were not significantly correlated with child age at the time of testing (NVIQ: r = −.11, df = 49,p = .44; VIQ: r = .01, df = 60, p = .95). Diagnosis (autism spectrum disorders vs. non- spectrum disorders) was not associated with absolute score differences for either NVIQ, F(1,49) = 0.01, p = .91, or VIQ, F(1, 60) = 1.51, p = .22.

Correlations were used to determine whether higher or lower scores on one or both tests were related to larger score discrepancies. For NVIQ, a trend-level association was revealed between scores on the DAS and absolute score differences between the two tests (r = .25, df = 49, p = .08). Although the relationship was not significant (possibly due to small sample size), additional investigation of the data revealed that 4 out of the 5 children who received above-average NVIQ scores on the DAS received MSEL NVIQ scores that were between 12 and 46 points lower.

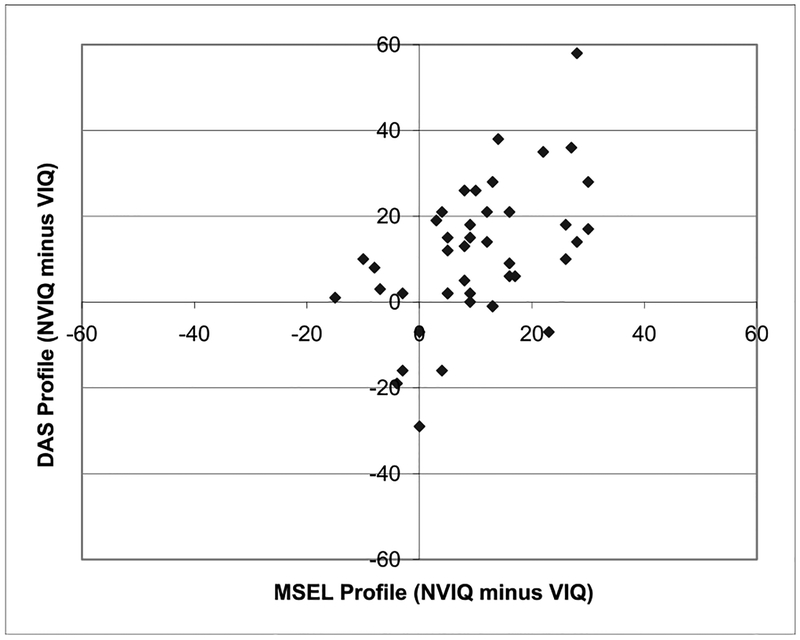

NVIQ–VIQ Profiles

Given recent interest in using the MSEL to examine cognitive profiles in children with autism spectrum disorders (e.g., Munson et al., 2008), we conducted analyses to determine whether patterns of NVIQ-VIQ scores on the MSEL were similar to patterns observed on the DAS in this sample of children with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities. Profile scores on each test were assessed by subtracting VIQ scores from NVIQ scores. A positive profile score indicated a higher NVIQ than VIQ, whereas a negative profile score indicated the opposite pattern. Among children for whom profile scores could be calculated on both tests (n = 43), the majority had scores in the same direction (i.e., either both positive or both negative). In 11 cases, there were disagreements between the two tests in whether the VIQ or the NVIQ was higher. In some such cases, the difference was not substantial. For example, 1 child had an MSEL profile that indicated that his NVIQ was 3 points lower than his VIQ and a DAS profile that indicated his NVIQ was 2 points higher than his VIQ. In other cases, however, the tests indicated highly discrepant profiles, including 1 child who received identical NVIQ and VIQ scores on the MSEL but a DAS NVIQ score that was 29 points lower than his DAS VIQ(see Figure 5). Thus, whereas profile scores on the two instruments were significantly correlated (r = .52, df = 41, p < .001), a relatively small percentage of children may have been categorized into different IQ profiles depending on which test scores had been used to do so.

Figure 5.

NVIQ–VIQ profile differences between the MSEL and the DAS. NVIQ = non-verbal IQ VIQ = NVIQ = verbal IQ; MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995); DAS = Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 1990).

Discriminant Validity

As shown in Table 3, we ran additional correlations for children with NVIQ and VIQ scores on both measures (n = 43) to address the issue of discriminant validity. For the DAS, whereas NVIQ and VIQ scores were significantly correlated with each other, each score was most highly related to its respective score on the MSEL. Similarly, MSEL VIQ scores showed the strongest relationship with DAS VIQ scores and were less highly correlated with NVIQ scores on either measure. On the other hand, MSEL NVIQ scores were equally highly correlated with all other scores and did not show the expected strongest relationship with DAS NVIQ scores compared with VIQ scores on both measures.

Table 3.

Correlations Among MSEL NVIQ, MSEL VIQ, DAS NVIQ, and DAS VIQ

| Variable | MSEL VIQ | DAS NVIQ | DAS VIQ |

|---|---|---|---|

| MSEL NVIQ | .76* | .74* | .76* |

| MSEL VIQ | — | .48* | .82* |

| DAS NVIQ | — | .56* |

Note. NVIQ = nonverbal IQ; MSEL = Mullen Scales of Early Learning (Mullen, 1995); VIQ = verbal IQ; DAS = Differential Ability Scales (Elliott, 1990).

Discussion

Children with suspected developmental disabilities are common recipients of IQ testing, yet psychometric data for cognitive tests are often derived primarily from samples of typically developing children. The lack of information about the use of these tests in nonnormative populations creates ambiguity in interpreting standardized scores for children with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities. Because the developmental patterns of these children are likely to be different from those of most children in typical norming samples, it is important to empirically assess the validity of cognitive tests such as the MSEL in samples of children with disabilities.

In the current study, the MSEL was found to have good convergent validity with a more established measure, the DAS, in a sample of young children with autism spectrum and nonspectrum diagnoses. For both VIQ and NVIQ, less than one third of children received scores on the two tests that were in different cognitive ability ranges. Even when larger score differences between the MSEL and the DAS were apparent, these differences did not consistently affect children’s cognitive ability classifications. For example, 1 child who received a NVIQ score of63 on the MSEL and a 44 on the DAS had a 19-point score discrepancy but still scored in the range of intellectual disability on both instruments. Another child who received a 110 on the MSEL and a 146 on the DAS exhibited a 36-point difference score but remained in the average–above-average range on both measures. When movement occurred between cognitive ability ranges, it was usually between the borderline–low-average range on one test and the intellectual disability or average range on the other test. These findings indicate that a child would be unlikely to simultaneously obtain a score in the average range on one of the tests and a score in the intellectual disability range on the other test.

Some of the largest score discrepancies were observed in children who received scores in the high-average range on the DAS. Four out of the 5 children who received above-average NVIQ scores on the DAS received MSEL NVIQ scores that were much lower. This may be due to the fact that the MSEL was designed as a developmental test, whereas the DAS is a test of cognitive abilities. The MSEL may be better used to differentiate children who are developmentally “on target” from those with delays, whereas the DAS can provide more fine-grained distinctions within the average and above-average ranges of intelligence. It is also possible that the DAS may overestimate abilities (or that the MSEL may underestimate abilities) in some young children. Because the lower end of the DAS age range is much higher than the lower end of the MSEL age range (30 months compared with 1 month), there are fewer items that a child must pass on the DAS to score in the average-above-average range compared with the MSEL. In addition, the DAS uses item sets rather than requiring that a child fail a certain number of items in a row, so the DAS can potentially be much shorter to administer than the MSEL. Thus, depending on where the clinician started on the MSEL, it is possible that some children with higher abilities may have received lower scores on the MSEL because they became fatigued as the test progressed. In our clinical experience, we often find that children seem less interested in the higher items on the MSEL compared with the lower MSEL items or the DAS items, so it is possible that these children simply lost motivation or attention during the administration of the MSEL. Examinations of predictive validity of IQ scores from the MSEL and the DAS will be informative in determining whether scores on one test or the other provide more accurate estimates of later cognitive abilities in young children with developmental disabilities.

The majority of children in the current study obtained similar scores on the MSEL and the DAS. These results provide some basis for using the MSEL and DAS together in studies that require more than one cognitive test option, as the tests appear to yield similar results when used concurrently. Furthermore, whereas the current study did not directly address the issue of predictive validity, establishing convergent validity between the MSEL and the DAS is an important first step in determining whether it is appropriate to use the DAS in follow-up studies of school-age children and adolescents who were assessed at younger ages with the MSEL. Given that scores on these two tests appear to be related when administered at the same time, it would be worthwhile for future research to examine the extent to which early MSEL scores are predictive of later DAS scores. However, to separate the issue of real changes in IQ over time, it may be necessary to explore first whether changes in (or stability of) MSEL scores during early childhood are similarly reflected by changes in DAS scores.

It is important to note that high agreement between MSEL and DAS scores in the current study was seen even though MSEL scores were derived using age equivalents (ratio IQs) and DAS scores were generated from standardized norm tables. There are several notable limitations to the current study, but these findings provide some support for the method of extrapolating ratio V IQ and NVIQ scores from the MSEL. On the other hand, because our sample only included preschoolage children, it is not clear whether using age equivalents to derive ratio IQs in school-age children or adolescents yields scores that would be comparable with norm-referenced IQ scores. Another important caveat pertains to the issue of discriminant validity and the need for additional research to investigate the psychometric properties of the MSEL as it is currently being used (i.e., extrapolating separate nonverbal and verbal domain scores). In the current study, MSEL NVIQ scores were highly related to DAS NVIQ scores, but they were equally highly related to VIQ scores on both measures. In contrast, MSEL VIQ scores were less highly related to DAS NVIQ scores than they were to DAS VIQ scores, indicating that the MSEL VIQ construct exhibits superior discriminant validity than the MSEL NVIQ construct. DAS NVIQ and VIQ scores were also correlated with each other but less so than with their comparable domain scores on the MSEL and much less so than NVIQ and VIQ scores on the MSEL. The MSEL was developed to provide one overall score (the ELC), whereas the DAS was constructed to yield scores in multiple domains. Consistent with the intended purpose of each measure, our results suggested that the MSEL is less well equipped than the DAS to provide independent measures of NVIQ and VIQ. Nevertheless, given that MSEL NVIQ and VIQ scores were differentially related to NVIQ and VIQ scores on the DAS (e.g., MSEL VIQ scores were more highly associated with DAS VIQ scores than DAS NVIQ scores), these findings provide some support for the continued practice of separating the MSEL into two domain scores. Again, it will be important for future research to further explore the question of whether extrapolated MSEL NVIQ and VIQ scores show similar relationships or lack of relationships with other measures of verbal and nonverbal abilities in other samples of children of different ages and ability levels.

The MSEL and DAS agreed in general with respect to NVIQ–VIQ profiles. However, approximately one fourth of children in this sample had profiles on the two tests that were in discrepant directions (e.g., higher NVIQ on the MSEL and lower NVIQ on the DAS), including a handful in which the discrepancies were large. Researchers who intend to use IQ as a primary study variable, such as for the purposes of organizing children with autism spectrum disorders into IQ-based subgroups, may wish to obtain more than one measure of IQ for each participant. Researchers could then ensure the validity of the profiles by choosing to only include children who demonstrated consistent profiles across multiple instruments. Another important cautionary note for researchers is that whereas most children did not shift ranges between the two tests, the average absolute score difference was more than 10 points for NVIQ and almost 8 points for VIQ. Thus, calculating absolute score differences to measure changes or outcomes could be dangerous when different tests are used at different time points. For example, if treatment effects are going to be measured using IQ scores, and changes in scores of 0.5 to 1 standard deviation are considered meaningful, a significant number of children in the study could be expected to show gains simply as an artifact of differences between the two tests. On the other hand, children in the current study did not consistently receive higher or lower scores on one of the instruments, so children in a treatment study would presumably be equally likely to show decreases in IQ as they would gains, if indeed the changes were fully the result of testing effects.

Limitations

There are a number of methodological limitations to the current study that underscore the need to view these as preliminary findings. Participants in the current study were drawn from an existing database of children seen through clinic and research evaluations and are not necessarily representative of all children with autism spectrum disorders or other developmental disabilities. Information about the order in which the tests were administered was not available, and formal interrater reliability assessments of administration and scoring procedures were not performed (although all clinicians were instructed to follow manualized procedures). Our ability to draw firm conclusions about the MSEL as an instrument was also limited by the relatively restricted age and ability range of our sample. Because the DAS is only appropriate for children over the age of 30 months, it was not possible to assess the convergent validity of the MSEL and the DAS in very young children and/or those with very low mental ages. Many recent studies of children with autism spectrum disorders and other developmental disabilities include infants and toddlers in the first 2 years of life. Our results do not provide information about how well the MSEL corresponds with other measures of ability in these children.

Assuming that the revised version of the MSEL is more psychometrically sound than its predecessor, we would predict similar results if all of the sample members had received the revised MSEL, but we cannot be certain of this. In addition, this study used the first edition of the DAS, but a second edition (Elliott, 2007) has since been published. Establishing convergent validity between the revised MSEL and the DAS-II, as well as between other IQ measures that are commonly used with children with developmental disabilities, will be an important topic of future study.

Another important limitation is that this study relied on classical test-theory procedures to assess relationships between the MSEL and DAS scores and assumed the linear equating method. Therefore, although these analyses offer some practical information about the equivalence of scores derived from the two tests, the methods of analysis did not allow us to evaluate whether information obtained from the MSEL and the DAS could be truly equated. Use of item response theory (IRT) methods in future studies would provide a useful alternative for exploring the relationships between scores on these two tests.

Conclusions

When the MSEL and the DAS were administered concurrently to a sample of children with autism spectrum and nonspectrum diagnoses, the MSEL showed good agreement with the DAS. Both in terms of actual scores and cognitive ability ranges, the MSEL and the DAS had high convergent validity. Given the central role of IQ scores in research on autism spectrum disorders and in clinical practice, it is important to undertake systematic investigations of the construct validity of cognitive tests. Researchers should not assume that different cognitive tests yield comparable scores. Particularly for longitudinal examinations of IQ stability, or for analyses of large samples of participants who are diverse in age and ability and assessed using different tests, it will be important to establish that IQ has a consistent meaning across instruments.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01 HD065277–01) to S. Bishop, from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH066496; R01 MH081873), and from the Collaborative Programs for Excellence in Autism (U19 HD35482) to C. Lord. Catherine Lord receives royalties from a publisher of diagnostic instruments described in this article. All profits generated in this regard are donated to charity. We thank Carrie Thomas, Kathryn Larson, and Kathy Hatfield for their assistance in preparing this article. We gratefully acknowledge the many clinicians at the University of Chicago, University of North Carolina, and University of Michigan who conducted the assessments of participants in this study, and we especially thank the children and families for their participation.

Contributor Information

Somer L. Bishop, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Whitney Guthrie, Florida State University.

Mia Coffing, SD Associates, LLC, Rutland, VT.

Catherine Lord, Weill-Cornell Medical College.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washington, DC: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Bayley N (2005). Bayley Scales of Infant Development. San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Billstedt E, & Gillberg C (2005). Autism after adolescence: Population-based 13-to 22-year follow-up study of 120 individuals with autism diagnosed in childhood. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 351–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop SL, Richler J, & Lord C (2006). Association between restricted and repetitive behaviors and nonverbal IQ in children with autism spectrum disorders. Child Neuropsychology, 4, 247–267. doi: 10.1080/09297040600630288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borden M, & Ollendick T (1994). An examination of the validity of social subtypes in autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 24, 23–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley-Johnson S (2001). Cognitive assessment for the youngest children: A critical review of tests. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 19, 19–44. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd PD, & Buckhalt JA (1991). A multitraitmultimethod construct validity study of the Differential Ability Scales. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 9, 121. [Google Scholar]

- Carpentieri S, & Morgan S (1996). Adaptive and intellectual functioning in autistic and nonautistic retarded children. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 26, 611–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chawarska K, Klin A, Paul R, & Volkmar F (2007). Autism spectrum disorder in the second year: Stability and change in syndrome expression. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 48, 128–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan J, & Jawad A (2005). Modeling clinical outcome of children with autistic spectrum disorders. Pediatrics, 116, 117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson G, Rogers S, Munson J, Smith M, Winter J, Greenson J, et al. (2009). Randomized, controlled trial of an intervention for toddlers with autism: The Early Start Denver Model. Pediatrics, 125, e17–e23. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dumont R, Cruse CL, Price L, & Whelley P (1996). The relationship between the Differential Ability Scales (DAS) and the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (WISC-III) for students with learning disabilities. Psychology in the Schools, 33, 203–210. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott C (2007). Differential Ability Scales (2nd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Harcourt Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott CD (1990). Differential Ability Scales. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Estes AM, Dawson G, Sterling L, & Munson J (2007). Level of intellectual functioning predicts patterns of associated symptoms in school-age children with autism spectrum disorder. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 112, 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fein D, Stevens M, Dunn M, Waterhouse L, Allen D, Rapin I, et al. (1999). Subtypes of pervasive developmental disorder: Clinical characteristics. Child Neuropsychology, 5, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E (2005). The epidemiology of pervasive developmental disorders In Casanova MF (Ed.), Recent developments in autism research (pp. 1–25). New York: Nova Biomedical Books. [Google Scholar]

- Gillberg C, & Steffenburg S (1987). Outcome and prognostic factors in infantile autism and similar conditions: A population-based study of 46 cases followed through puberty. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 17, 273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotham K, Bishop SL, & Lord C (2011). Diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders In Amaral, Geshwind, & Dawson (Eds.), Autism spectrum disorders (pp. 30–43). New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Harris SL, & Handleman JS (2000). Age and IQ at intake as predictors of placement for young children with autism: A four-to six-year follow-up. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 30, 137–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, & Rutter M (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45, 212–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00215.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph RM, Tager-Flusberg H, & Lord C (2002). Cognitive profiles and social-communicative functioning in children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 43, 807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landa R, & Garrett-Mayer E (2006). Development in infants with autism spectrum disorders: A prospective study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 47, 629–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, & Bishop SL (2009). The autism spectrum: Definitions, assessment and diagnoses. British Journal of Hospital Medicine (London), 70, 132–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Risi S, DiLavore PS, Shulman C, Thurm A, & Pickles A (2006). Autism from 2 to 9 years of age. Archives of General Psychiatry, 63, 694–701. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.6.694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, DiLavore PC, & Risi S (1999). Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Mullen EM (1995). Mullen Scales of Early Learning. Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. [Google Scholar]

- Munson J, Dawson G, Sterling L, Beauchaine T, Zhou A, Koehler E, et al. (2008). Evidence for latent classes of IQ in young children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Intellectual and Developmental Disability, 113, 449–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richler J, Bishop S, Kleinke J, & Lord C (2007). Restricted and repetitive behaviors in young children with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 73–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roid G (2003). Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales (5th ed.). Rolling Meadows, IL: Riverside Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M, Le Couteur A, & Lord C (2003). Autism Diagnostic Interview—Revised (ADI-R). Los Angeles: Western Psychological Services. [Google Scholar]

- Sevin J, Matson J, Coe D, Love S, Matese M, & Benavidez D (1995). Empirically derived subtypes of pervasive developmental disorders: A cluster analytic study. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 25, 561–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherer MR, & Schreibman L (2005). Individual behavioral profiles and predictors of treatment effectiveness for children with autism. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Ppsychology, 73, 525–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T (1999). Outcome of early intervention for children with autism. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice, 6, 33–49. [Google Scholar]

- Sutera S, Pandey J, Esser EL, Rosenthal MA, Wilson LB, Barton M, et al. (2007). Predictors of optimal outcome in toddlers diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Journal ofAutism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 98–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike RL, Hagen EP, & Sattler JM (1986). The Stanford-Binet Intelligence Test. Chicago: Riverside. [Google Scholar]

- Volkmar F, Cohen D, Bregman J, Hooks M, & Stevenson J (1989). An examination of social typologies in autism. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 28, 82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2002). Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence (3rd ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2003). Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (4th ed.). San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Werner E, Dawson G, Munson J, & Osterling J (2005). Variation in early developmental course in autism and its relation with behavioral outcome at 3–4 years of age. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35, 337–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwaigenbaum L, Thurm A, Stone W, Baranek G, Bryson S, Iverson J, et al. (2007). Studying the emergence of autism spectrum disorders in high-risk infants: Methodological and practical issues. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 466–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]