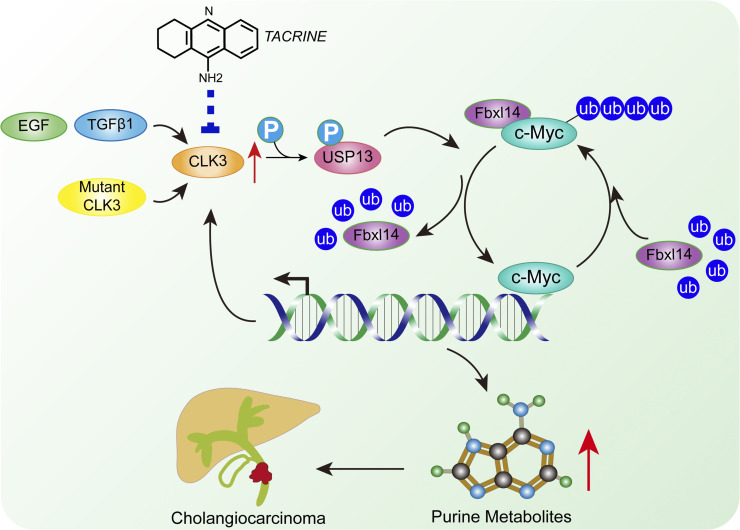

Zhou et al. characterize a critical role of CLK3 on purine metabolism in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA). Overexpressed or mutated CLK3 promotes CCA progression in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, CLK3 may serve as a biomarker and potential drug target for CCA.

Abstract

CDC-like kinase 3 (CLK3) is a dual specificity kinase that functions on substrates containing serine/threonine and tyrosine. But its role in human cancer remains unknown. Herein, we demonstrated that CLK3 was significantly up-regulated in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) and identified a recurrent Q607R somatic substitution that represented a gain-of-function mutation in the CLK3 kinase domain. Gene ontology term enrichment suggested that high CLK3 expression in CCA patients mainly was associated with nucleotide metabolism reprogramming, which was further confirmed by comparing metabolic profiling of CCA cells. CLK3 directly phosphorylated USP13 at Y708, which promoted its binding to c-Myc, thereby preventing Fbxl14-mediated c-Myc ubiquitination and activating the transcription of purine metabolic genes. Notably, the CCA-associated CLK3-Q607R mutant induced USP13-Y708 phosphorylation and enhanced the activity of c-Myc. In turn, c-Myc transcriptionally up-regulated CLK3. Finally, we identified tacrine hydrochloride as a potential drug to inhibit aberrant CLK3-induced CCA. These findings demonstrate that CLK3 plays a crucial role in CCA purine metabolism, suggesting a potential therapeutic utility.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) stemming from cholangiocytes is a primary hepatic malignancy and is divided as extrahepatic and intrahepatic according to its anatomical position (Maroni et al., 2013). The incidence of CCA is increasing worldwide, and its prognosis has remained dismal. So far, there are no uniquely identified markers for CCA, and very few options for its treatment are available. Although several risk factors such as ERBB2, FOXM1, and Yap have been shown to promote CCA initiation (Sugihara et al., 2019), they are not typically found in most CCA patients. Recently, genetic studies have enhanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms by which normal biliary cells acquire the properties of malignant transformation in human CCA (Marks and Yee, 2016). Therefore, more efforts in this direction might form the basis for developing new diagnostic approaches and more effective therapy for CCA.

Uncontrolled cell proliferation is a characteristic of human cancer. Purines are the most abundant metabolic substrates by providing necessary components for DNA and RNA to support cell proliferation (Yin et al., 2018). Therefore, enhanced purine biosynthesis is tightly associated with the progression of cancer. We and other groups previously reported that several kinases and transcriptional factors, for example, mechanistic target of rapamycin kinase (mTOR), activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4), microphthalmia-associated transcription factor (MITF), and c-Myc, dictated cancer-dependent purine biosynthesis (Ben-Sahra et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2019). However, the direct signaling network linking the purine synthesis pathway and CCA development is entirely unknown.

CDC-like kinase 3 (CLK3) is a nuclear dual-specificity kinase that functions on substrates containing serine/threonine and tyrosine (Nayler et al., 1997). CLK3 modulates RNA splicing by phosphorylating serine/arginine–rich proteins such as SRSF1 and SRSF3 (Cesana et al., 2018). Recently, CLK3 dysregulation was indicated to be a high-penetrant factor in different types of human tumors even though its functions in tumors were not clearly characterized (Bowler et al., 2018).

In this work, we identified a critical Q607 somatic mutation of CLK3 in CCA patients by exon sequencing. Then, we uncovered the importance of this CLK3 mutant as an oncogene in promoting de novo purine synthesis in CCA. Moreover, through drug screening, for the first time we identified tacrine hydrochloride as a potential drug to inhibit the aberrant CLK3-induced CCA. Thus, our data provide a new therapeutic strategy for CCA harboring CLK3 dysregulation.

Results

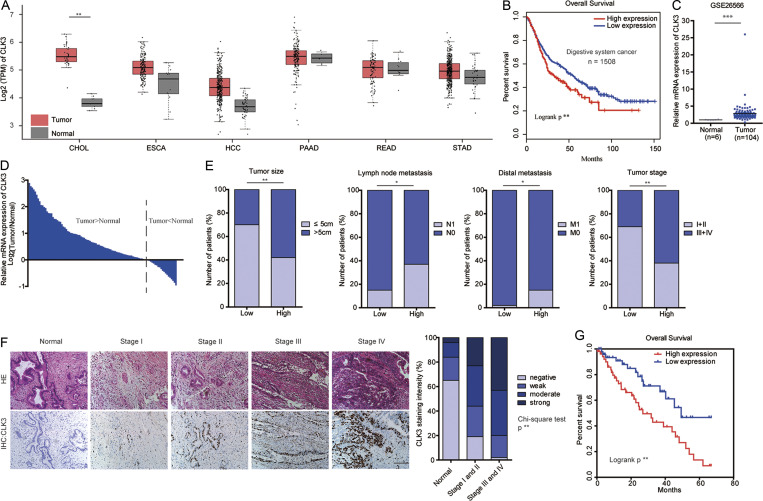

The levels of CLK3 in CCA and other digestive system cancers are significantly up-regulated and associated with decreased overall survival (OS)

It is well known that the kinase families play important roles in the development of various types of cancer. Therefore, by analyzing openly available databases, we hoped to screen several candidate kinases that may have significant effects on carcinogenesis. By thoroughly analyzing gene expression profiles across 1,508 digestive system tumors with various histological subtypes in The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA), we found that CLK3 was significantly up-regulated compared with nontumor controls (Fig. 1 A) and that the survival of patients with high CLK3 expression significantly decreased (Fig. 1 B), suggesting a potential pro-oncogenic role of CLK3 in the human digestive system. However, very little is known about the physiological function of CLK3 in cancer. Thus, we focused on CLK3 in this study. Given that the change in the level of CLK3 expression was most notable in CCA compared with other tumors (Fig. 1 A), in the following experiments, we mainly examined the clinical significance and action mechanisms of CLK3 in CCA.

Figure 1.

The levels of CLK3 in CCA and other digestive system cancers are significantly up-regulated and associated with decreased OS. (A) TCGA analysis of CLK3 mRNA expression in 1,508 human digestive system tumors. Data are mean ± SD. **, P < 0.01; unpaired Student’s t test. (B) The survival of patients with high CLK3 expression was poor based on TCGA data in A. **, P < 0.01; Kaplan-Meier analysis. (C) Analysis of CLK3 expression based on open GSE26566 data. Data are mean ± SD. ***; P < 0.001; unpaired Student’s t test. (D) CLK3 mRNA expression in 100 human CCA specimens and matched normal samples was determined by quantitative PCR. (E) CLK3 expression in 100 human CCA specimens was analyzed as follows: level, tumor size, metastasis, and stage. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; χ-square test. (F) IHC analysis of CLK3 expression in 100 human CCA specimens and matched normal samples. Representative pictures are presented. Bar, 100 µm. **, P < 0.01; χ-square test. (G) Stratified by CLK3 levels in CCA patients (n = 100), Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS is presented. **, P < 0.01. CHOL, cholangiocarcinoma; ESCA, esophageal carcinoma; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HE, hematoxylin and eosin; PAAD, pancreatic adenocarcinoma; READ, rectum adenocarcinoma; STAD, stomach adenocarcinoma; TPM, transcripts per million.

Analysis of open GSE26566 data and CCA cell lines confirmed that CLK3 expression was enhanced compared with their controls (Fig. 1 C and Fig. S1 A). Tissue array data indicated that the percentage of cells with CLK3 expression was positively associated with the stages of CCA patients (Fig. S1 B), implying that the levels of CLK3 tightly correlate with CCA malignancy. Analysis of a cohort of 100 CCA patients further validated that CLK3 expression was up-regulated and positively related to tumor size, stage, and metastasis (Fig. 1, D–F; and Table S1). Kaplan-Meier data from two independent cohorts indicated that CCA patients with higher levels of CLK3 had shorter OS (Fig. 1 G and Fig. S1 C). Multivariate analyses identified CLK3 as an independent prognostic factor in CCA (Table S2). Together, our data uncovered that CLK3 may promote the pathogenesis of CCA.

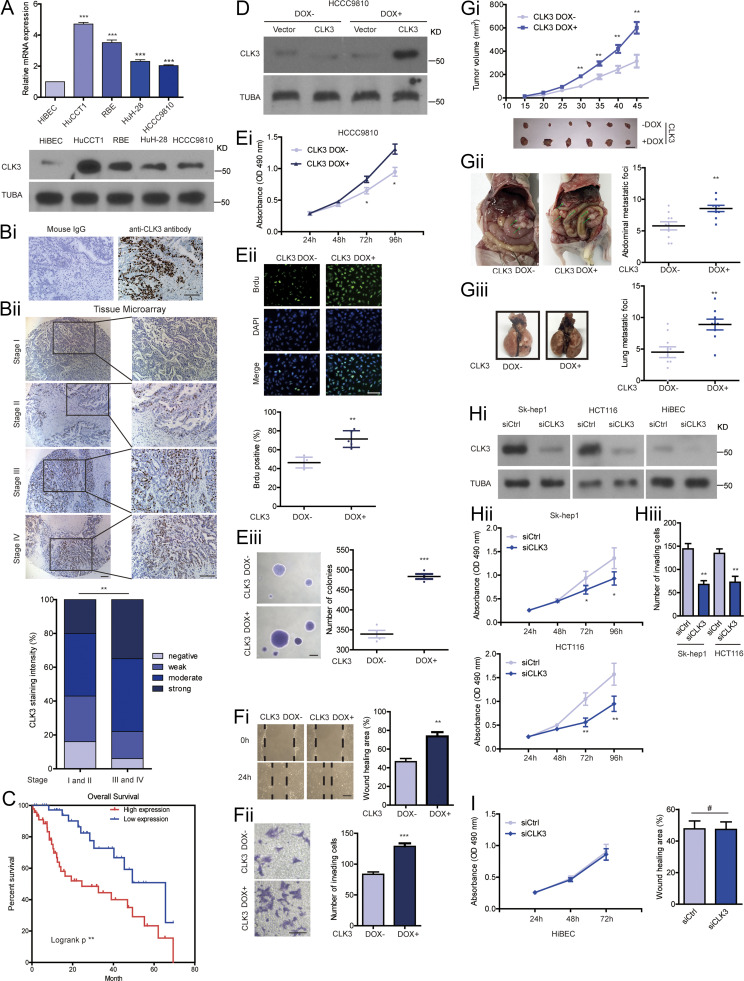

Figure S1.

CLK3 in CCA is significantly up-regulated and associated with decreased OS and acts as an oncogene. (A) Examining the mRNA (upper panel) and protein (lower panel) levels of CLK3 in normal cholangiocytes and CCA cell lines. (Bi) Serial slides were incubated with either mouse IgG or CLK3 antibody for IHC detection. Bar, 100 µm. (Bii) IHC analysis of CLK3 expression in a CCA patient’s tissue array (n = 100). Representative pictures are presented. Bars, 100 µm. (C) Stratified by CLK3 levels in CCA patients (n = 84), Kaplan-Meier analysis of OS is shown. (D and Ei) MTT assays were performed to compare the proliferation of HCCC9810 cells with Dox-induced CLK3 expression or without, which was confirmed using immunoblotting. (Eii) BrdU assay in D. (Eiii) Soft agar assays in D. Bar, 100 µm. (Fi and Fii) Transwell assays and wound healing using HCCC9810 treated as in D. (Gi) The effect of CLK3 overexpression induced by Dox on HCCC9810 xenografts. (Gii and Giii) Dox-inducible expression of CLK3 in HCCC9810 cells significantly promoted the number of CCA abdominal metastatic nodules (ii) and lung metastatic nodules (iii) compared with their controls. (Hi and Hii) MTT assays were performed to compare the proliferation of Sk-hep1 and HCT116 cells with CLK3 knockdown, which was confirmed using immunoblotting. (Hiii) Transwell assay in Hi. (I) MTT assays and wound healing using HiBEC treated as in D. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, not significant. Data are mean ± SEM and are from three (F, G, Hii, Hiii, and I) and four (E) independent experiments or representative of three independent experiments with similar results (A lower panel, D, and Hi). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (E–G, Hii, Hiii, and I) or one-way ANOVA (A) or χ-square test (Bii). KD, knockdown; TUBA, alpha tubulin.

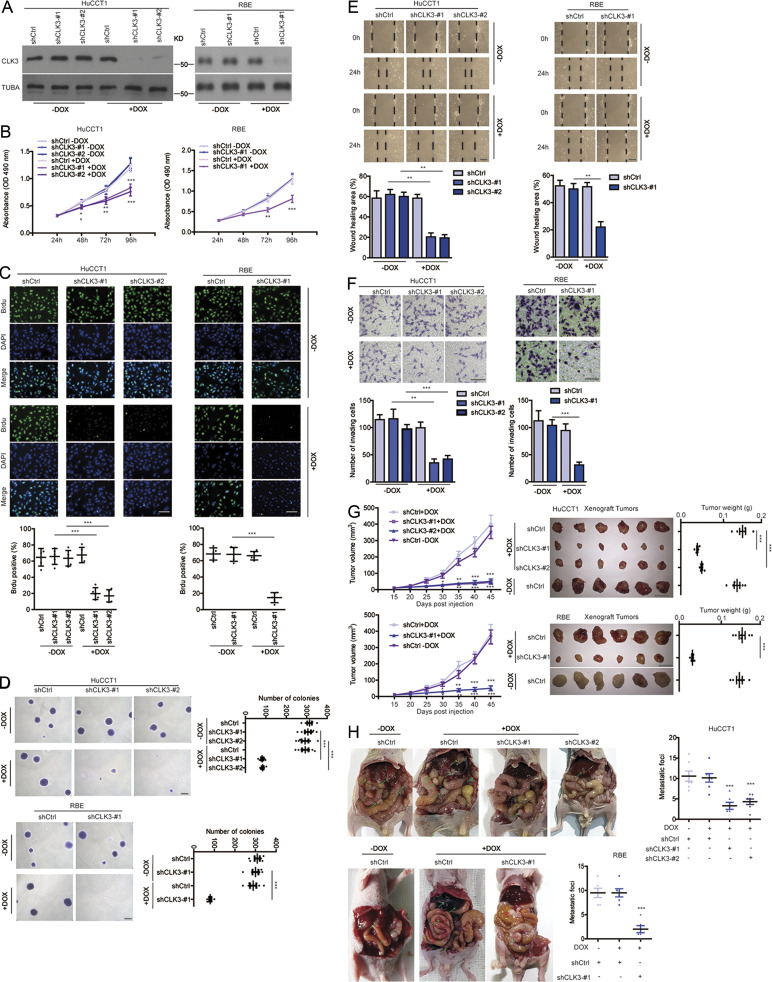

Silencing CLK3 strongly suppresses the aggressiveness of CCA cells

To uncover the exact biological roles of CLK3 in CCA, we first examined the effect of CLK3 knockdown or overexpression on CCA cell proliferation. As shown in Fig. 2, A–C, doxycycline (Dox)-induced CLK3 deficiency significantly impaired HuCCT1 and RBE cell proliferation and BrdU incorporation. Consistently, CLK3 knockdown suppressed the anchorage-independent growth of CCA cells (Fig. 2 D). However, overexpression of CLK3 in CLK3-low HCCC9810 and HuH-28 cells had the opposite effects (Fig. S1, D–Eiii; and data not shown), implicating CLK3 as a direct oncogene. Wound healing and transwell experiments demonstrated the invasive function of CLK3 in CCA cells (Fig. 2, E and F; and Fig. S1, Fi and Fii). In accordance with in vitro findings, CLK3 silencing in CLK3-high HuCCT1 and RBE cells significantly inhibited the development of mice xenograft tumors, whereas its overexpression in HCCC9810 cells enhanced this development (Fig. 2 G and Fig. S1 Gi). The knockdown of CLK3 markedly reduced the number of CCA abdominal metastatic nodules (Fig. 2 H). However, CLK3 overexpression significantly promoted CCA metastasis (Fig. S1, Gii and Giii). Together, our findings confirm the tumor-promoting activity of CLK3 in CCA.

Figure 2.

Silencing CLK3 strongly suppresses the aggressiveness of CCA cells. (A and B) MTT assays for measuring the proliferation of the HuCCT1 and RBE cells with or without 4 µg/ml Dox-induced knockdown of CLK3, which was confirmed using immunoblotting. (C) BrdU incorporation assay was performed using samples in A. Bars, 100 µm. (D) Examining anchorage-independent growth using samples in A. Bars, 100 µm. (E and F) Wound healing and transwell experiments using samples in A. Bars, 100 µm. (G) The effect of CLK3 deficiency induced by Dox in HuCCT1 and RBE cells on mice xenografts. Bars, 1 cm. (H) Dox-inducible knockdown of CLK3 in HuCCT1 and RBE cells significantly inhibited the number of CCA abdominal metastatic nodules. Arrows indicate metastatic foci. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P< 0.001. Data are mean ± SEM and are from three (B and E–H), four (C), and five (D) independent experiments or are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (A). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (B and G) or one-way ANOVA (C–F and H). KD, knockdown; TUBA, alpha tubulin.

We also examined the effect of CLK3 knockdown on other cells lines from other cancers and on normal biliary epithelial cells (HiBEC). As shown in Fig. S1, Hi and Hii, we observed similar effects on Sk-hep1 cells (hepatocellular carcinoma) and HCT116 cells (colon cancer) compared with CCA cells, whereas there were few effects on HiBEC cells after CLK3 knockdown (Fig. S1 Hiii).

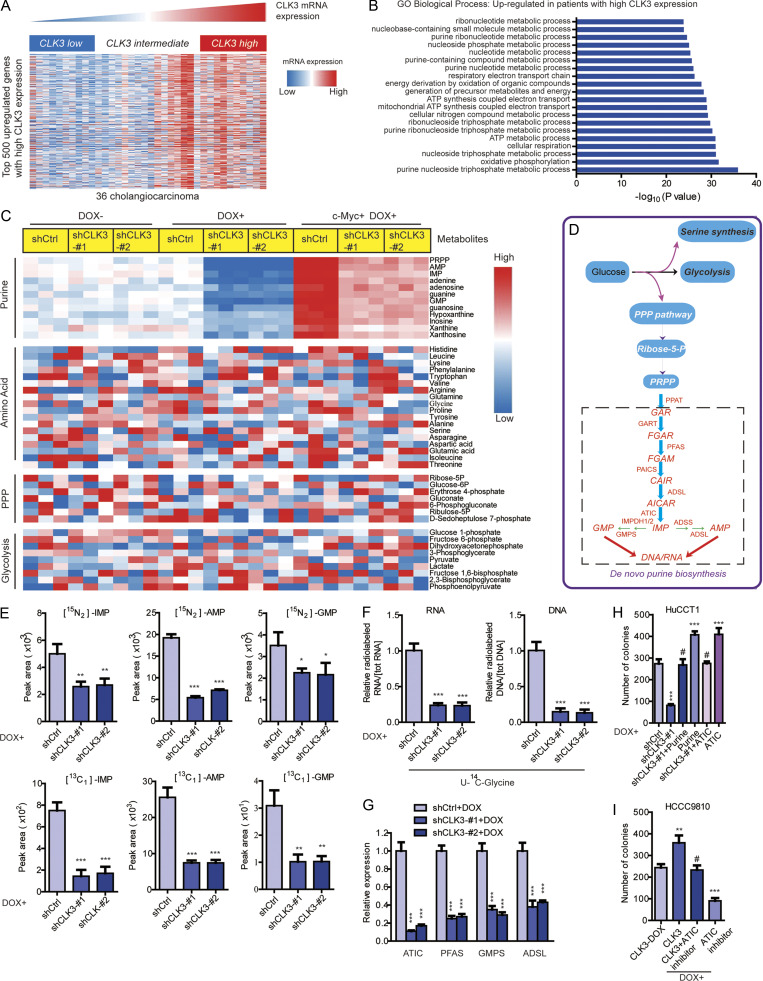

CLK3 up-regulation promotes CCA development by reprogramming purine metabolism

To further uncover the action mechanism of CLK3 in CCA, we assessed the transcriptomes of TCGA of human CCA to examine the top 500 differentially expressed genes with varying CLK3 expression (Fig. 3 A and Table S3). Gene ontology term enrichment suggested that high CLK3 expression in CCA patients might primarily reprogram tumor metabolism, particularly purine metabolism (Fig. 3 B). Thus, mass spectrometry (MS) was performed to collect metabolic profiling of HuCCT1 cells with or without Dox-induced CLK3 knockdown. Interestingly, CLK3 silencing mainly down-regulated the intracellular pools of purine intermediates (Fig. 3, C and D; and Table S4), suggesting that silencing CLK3 in CCA cells primarily inhibits purine synthesis.

Figure 3.

CLK3 up-regulation promotes CCA development by reprogramming purine metabolism. (A) Heatmap of top 500 up-regulated genes in human CCA with a high abundance of CLK3. (B) Top 20 biological processes uncovered among CCA patients with high CLK3 expression using gene ontology term enrichment. (C) LC-MS/MS was used to examine the metabolites in HuCCT1 cells with or without CLK3 deficiency induced by Dox or with Dox-induced c-Myc introduction. The data are shown in the heatmap. (D) Schematic representation of the main metabolic pathways. (E) LC-MS/MS analysis was performed to measure 15N-glutamine–labeled intermediates of purine synthesis (upper panel) or metabolites labeled with 13C-glycine (lower panel) in HuCCT1 cells with Dox-induced CLK3 knockdown. (F) Measuring RNA and DNA with the incorporation of 14C-glycine using samples in E. (G) Quantitative RT-PCR assays were used to analyze the effects of CLK3 silencing on the genes deciding purine metabolism in HuCCT1 cells. (H) CLK3 silencing significantly decreased HuCCT1 cell proliferation, while overexpressing ATIC or adding purine markedly reverted this defect. (I) ATIC inhibitor significantly reverted the proliferation of HCCC9810 cells induced by CLK3 overexpression. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, not significant; one-way ANOVA. Data are from three independent experiments (C and E–I; mean ± SEM). GO, gene ontology; KD, knockdown; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate.

Supporting this finding, Dox-induced CLK3 knockdown in HuCCT1 cells significantly inhibited the numbers of 15N-purine intermediates (inosine monophosphate, adenosine monophosphate, and guanosine monophosphate; Fig. 3 E, upper panel). Second, similar findings were observed when the flux of 13C-glycine into purine intermediates was analyzed (Fig. 3 E, lower panel). Third, Dox-induced CLK3 knockdown significantly decreased the levels of DNA and RNA labeled with 14C-glycine in HuCCT1 cells (Fig. 3 F). Fourth, Dox-induced CLK3 knockdown in HuCCT1 cells significantly suppressed the critical enzymes that are necessary for the de novo purine synthesis pathway (Fig. 3 G). However, Dox-induced CLK3 overexpression in HCCC9810 cells had the opposite effects (Fig. S2, Ai and Bi). Our data strongly confirm that CLK3 mainly activates de novo purine synthesis in CCA.

Figure S2.

CLK3 promotes purine synthesis and CCA progression through enhancing the stabilization and nuclear translocation of c-Myc. (Ai) LC-MS/MS analysis was performed to measure 15N-glutamine–labeled intermediates of purine synthesis in HCCC9810 cells with or without Dox-induced CLK3 overexpression. (Aii and Aiii) LC-MS/MS was used to analyze metabolites labeled with 13C-glycine (ii) and 14C-glycine (iii) in HCCC9810 cells with or without Dox-induced CLK3 overexpression. (Bi) Performing quantitative RT-PCR assays as indicated in HCCC9810 cells with or without Dox-induced CLK3 overexpression. (Bii) CLK3 silencing significantly decreased HuCCT1 cell invasion while overexpressing ATIC or adding purine markedly reverted this defect. (Biii) ATIC inhibitor significantly reverted the invasion of HCCC9810 cells induced by CLK3 overexpression. (Ci) Western blots confirmed CLK3 overexpression and c-Myc knockdown in HCCC9810 cells. (Cii) The effects of silencing c-Myc on the levels of GMP, AMP, and IMP in HCCC9810 cells with CLK3 overexpression. (Ciii) Silencing c-Myc reduced the levels of U-14C-glycine in HCCC9810 cells with CLK3 overexpression. (D) The knockdown of c-Myc suppressed purine-associated enzymes in HCCC9810 cells with CLK3 overexpression. (Ei and Eii) The impacts of CLK3 knockdown or overexpression on the nuclear translocation of c-Myc in HuCCT1 (i) or HCCC9810 (ii) cells were analyzed by immunofluorescence staining and were quantified. Bars, 50 µm. (F) Silencing c-Myc reverted the aggressiveness of HCCC9810 cells with CLK3 overexpression. (G) CLK3 knockdown reduced the mRNA levels of genes of ribosome components (i) and their regulators (ii). *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, not significant. Data are mean ± SEM and are from three (A, B, Cii, Ciii, D, E, and Fii, and Fiii) and four (Fi) independent experiments or are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (Ci). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (Ai, Bi, and Ei) or one-way ANOVA (Bii, Biii, Cii, Ciii, D, Eii, and F). KD, knockdown; IB, immunoblot; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; TUBA, alpha tubulin.

Next, we explored the physiological significance of CLK3-mediated de novo purine synthesis in CCA progression. As shown in Fig. 3 H and Fig. S2 Bii, although CLK3 silencing strongly inhibited the proliferative and invasive abilities of HuCCT1 cells, supplementation of purine or overexpression of ATIC (one critical enzyme in the purine synthesis pathway) significantly rescued these defects. Conversely, ATIC inhibitor significantly reverted the proliferation, migration, and invasion of HCCC9810 cells induced by CLK3 overexpression (Fig. 3 I and Fig. S2 Biii).

Taken together, our data indicate that CLK3 up-regulation promotes CCA development at least partially by reprogramming de novo purine metabolism.

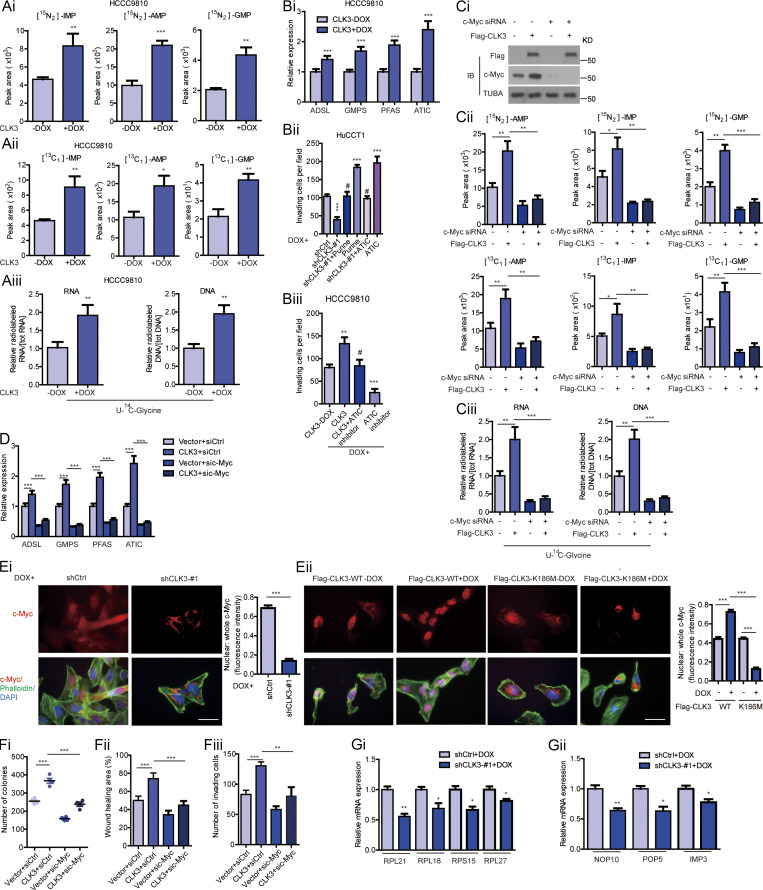

CLK3 promotes de novo purine synthesis and CCA progression through enhancing the stabilization and nuclear translocation of c-Myc

Given that mTOR, c-Myc, MITF, and ATF4 dictated the de novo purine synthesis pathway (Ben-Sahra et al., 2016), we hypothesized that they might mediate the effects of CLK3 on CCA. Interestingly, the knockdown of c-Myc but not MITF or ATF4 or mTOR inhibition significantly reverted CLK3-driven increase in the purine metabolism intermediates in HCCC9810 cells (Fig. S2 C; and data not shown). Conversely, c-Myc introduction reverted the shCLK3-mediated effects on purine metabolism (Fig. 3 C and Fig. 4, A and B). The knockdown of c-Myc also significantly down-regulated the abundance of several enzymes that are necessary for purine metabolism reprogramming in HCCC9810 cells with CLK3 overexpression (Fig. S2 D).

Figure 4.

CLK3 promotes de novo purine synthesis and CCA progression through enhancing the stabilization and nuclear translocation of c-Myc. (A and B) The effects of introducing c-Myc on shCLK3-mediated purine metabolites in HuCCT1 cells. (C) The effect of CLK3 knockdown or overexpression on c-Myc mRNA abundance in HuCCT1 cells (left) or HCCC9810 cells (right), respectively. (D and E) The c-Myc half-life in HuCCT1 (D) and HCCC9810 (E) cells treated using CHX (20 µg/ml). (F) The effect of MG132 on c-Myc degradation in HuCCT1 cells. (G) The impacts of CLK3 knockdown or overexpression on the subcellular localization of c-Myc in HuCCT1 (i) or HCCC9810 (ii) cells were analyzed by Western blot and quantified. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, not significant. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (D and E) or from three independent experiments (A–C, F, and G; mean ± SEM). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (C and G) or one-way ANOVA (A, B, and F). Cyto, cytoplasmic; KD, knockdown; Nucl, nuclear; PPP, pentose phosphate pathway; AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; TUBA, alpha tubulin.

Notably, CLK3 overexpression up-regulated the protein levels of c-Myc but did not affect its mRNA levels (Fig. 4 C and Fig. S2 Ci). Cycloheximide (CHX) chase assays indicated that CLK3 deficiency in HuCCT1 cells significantly reduced the half-time of c-Myc protein. However, WT-CLK3 but not active-dead CLK3-K186M overexpression in HCCC9810 cells had the opposite effect (Fig. 4, D and E). Furthermore, MG132 reverted c-Myc down-regulation mediated by CLK3 silencing (Fig. 4 F). These data indicate that overexpression of CLK3 enhances the stability of c-Myc protein in CCA cells.

We also observed that overexpression of WT-CLK3 but not CLK3-K186M enhanced c-Myc nuclear translocation, while the deficiency of CLK3 had the opposite effect (Fig. 4, Gi and Gii; and Fig. S2, Ei and Eii), suggesting that CLK3 overexpression promotes purine synthesis by enhancing the transcriptional activity of c-Myc.

Functionally, silencing c-Myc significantly reverted CLK3-induced HCCC9810 cell proliferation, migration, and invasion (Fig. S2 F). Therefore, we propose that c-Myc is a necessary effector downstream of CLK3 in CCA.

To elucidate if other importantly oncogenic pathways regulated by c-Myc (such as ribosome biogenesis; van Riggelen et al., 2010) were similarly affected, we reexamined the top 500 genes affected by CLK3. As shown in Table S5, a set of genes involved in ribosome biogenesis was present. To further confirm if ribosome biogenesis was also affected by CLK3, we determined the mRNA levels of several representative genes. As shown in Fig. S2 G, their mRNA levels were down-regulated after CLK3 depletion, suggesting that CLK3 also affects ribosomal biogenesis in CCA.

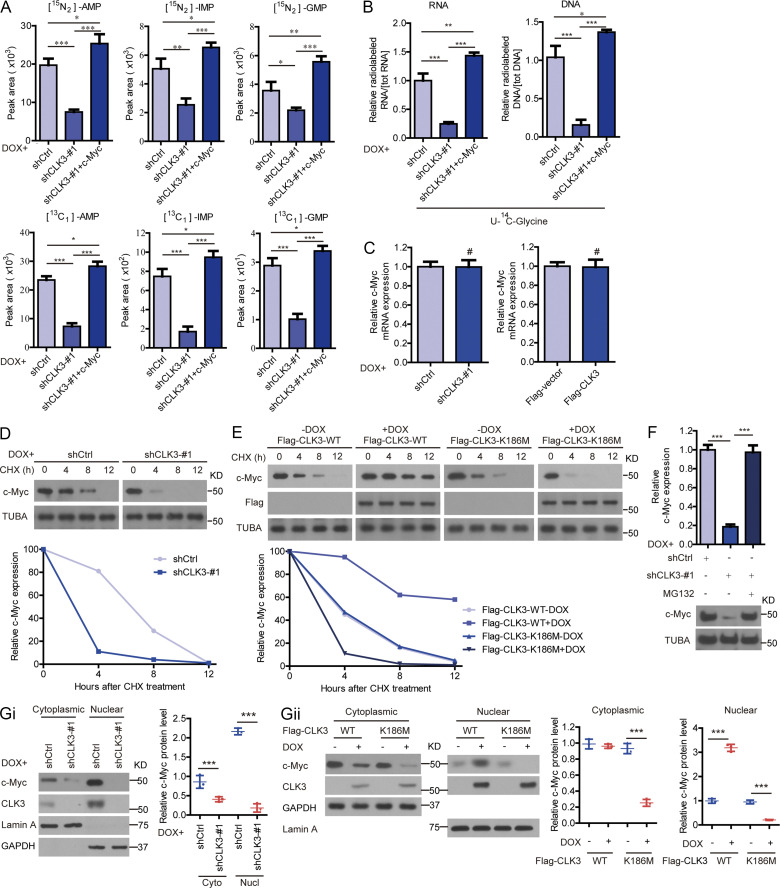

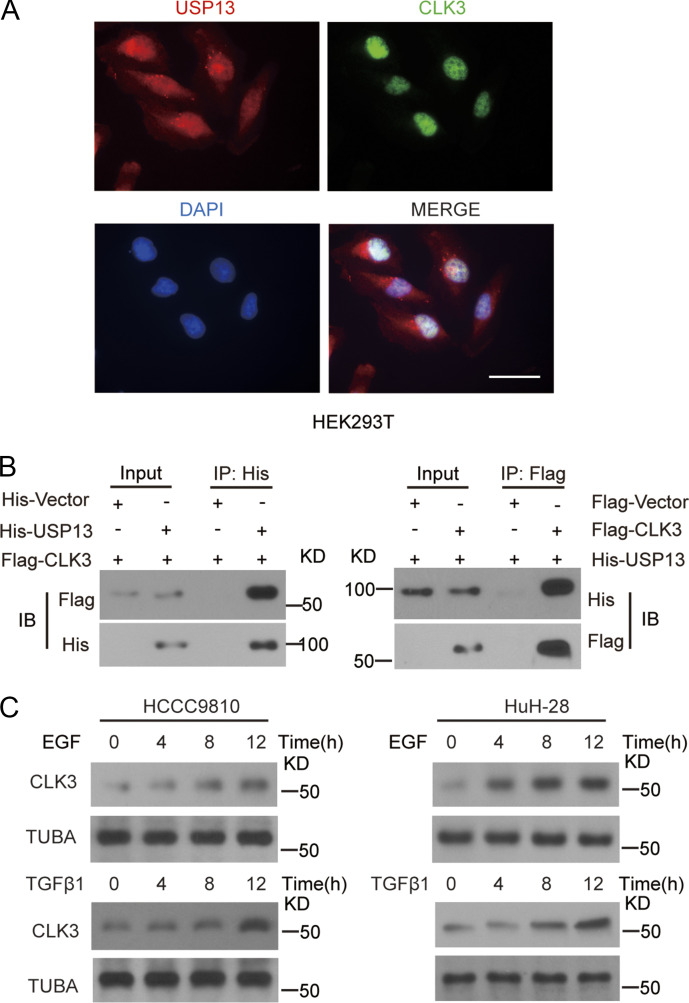

CLK3 directly interacts with and phosphorylates USP13 at Y708

To clarify the regulatory mechanism by which CLK3 stabilized c-Myc, the proximity-dependent biotin (BioID2) experiment was performed in HCCC9810 cells. This screening identified SRSF1 and SRSF3, two bona fide CLK3 interactors (Cesana et al., 2018), validating the approach (Fig. 5 A and Table S6). Given that USP13 was exclusively observed in CLK3-BioID2 interactors and was previously shown to prevent Fbxl14-mediated c-Myc ubiquitination (Fang et al., 2017), we reasoned that USP13 mediated a potential link between CLK3 and c-Myc. We found that USP13 coimmunoprecipitated and colocalized with endogenous CLK3 in HuCCT1 cells or with exogenous CLK3 in HEK293 cells (Fig. 5 B and Fig. S3, A and B). A pulldown experiment suggests a direct binding of USP13 to CLK3 (Fig. 5 C). An in vitro kinase assay indicated that WT-CLK3 but not CLK3-K186M was able to directly phosphorylate USP13 (Fig. 5 D). MS identified highly conserved tyrosine 708 in USP13 as a CLK3-mediated phosphorylation site (Fig. 5 E). USP13-Y708 mutation to phenylalanine (Y708F) abrogated CLK3-mediated phosphorylation (Fig. 5 F). We made a special antibody against USP13-Y708 phosphorylation for the following experiments. Interestingly, CCA-associated epidermal growth factor (EGF) and TGFβ1 treatment significantly increased endogenous phospho-USP13–Y708 levels by approximately threefold without changing USP13 levels in HuCCT1 and RBE cells (Fig. 5 G). However, CLK3-K186M transfection impaired this increase (Fig. 5 H). Consistently, His-USP13 was phosphorylated at tyrosine, but not at serine or threonine in HCCC9810-transfected Flag-CLK3 upon EGF or TGFβ1 treatment (Fig. 5 I). Notably, EGF and TGFβ1 treatment significantly up-regulated CLK3 expression in HCCC9810 and HuH-28 cells (Fig. S3 C). Together, USP13 is a new substrate of CLK3 in CCA.

Figure 5.

CLK3 directly interacts with and phosphorylates USP13 at Y708. (A) Volcano plot showing CLK3 interactors identified in HCCC9810 cells with Empty-BioID2 or CLK3-BioID2 (n = 6). (B) Co-IP assays for endogenous CLK3 and USP13 from HuCCT1 cells. IB, immunoblot. (C) GST pulldown assays were performed. (D) Ni-NTA agarose beads were used to immobilize bacterially purified His-CLK3 proteins as indicated. Then, these beads were incubated with purified GST-USP13 and [γ-32P] ATP kinase buffer. Autoradiography was performed. (E) MS was performed to identify CLK3-induced phosphorylation site of USP13 (lower panel). Sequences containing Y708 across species are shown (upper panel). (F) The effect of USP13-Y708F on CLK3-mediated phosphorylation. (G) HuCCT1 and RBE cells were treated with or without EGF or TGFβ1. IP with USP13 was performed. A specific anti-phospho-USP13-Y708 antibody produced by this group was used to detect USP13 phosphorylation. (H) HuCCT1 cells with or without CLK3-K186M transfection were treated by EGF (50 ng/ml) or TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml). IP with USP13 was performed. A specific anti-phospho-USP13-Y708 antibody was used to detect USP13 phosphorylation. (I) HCCC9810 cells stably expressing Flag-CLK3 and His-USP13 were treated with EGF (50 ng/ml) or TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml) for 60 min. Western blots were performed as indicated. Phosphotyrosine (p-Tyr), phosphoserine (p-Ser), and phosphothreonine (p-Thr) were analyzed. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (B–D and F–I). TUBA, alpha tubulin.

Figure S3.

CLK3 directly interacted with USP13, and CLK3 expression was up-regulated on EGF or TGFβ1 treatment. (A) Immunofluorescence staining indicated the nuclear colocalization of CLK3 and USP13 in HuCCT1 cells. Bar, 50 µm. (B) Indicated constructs were transfected into HEK293T cells. Co-IP was performed with indicated antibody. (C) HCCC9810 and HuH-28 cells were added with or without EGF (50 ng/ml) or TGFβ1 (10 ng/ml) for indicated time. CLK3 expression was analyzed using immunoblotting. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results. IB, immunoblot; TUBA, alpha tubulin.

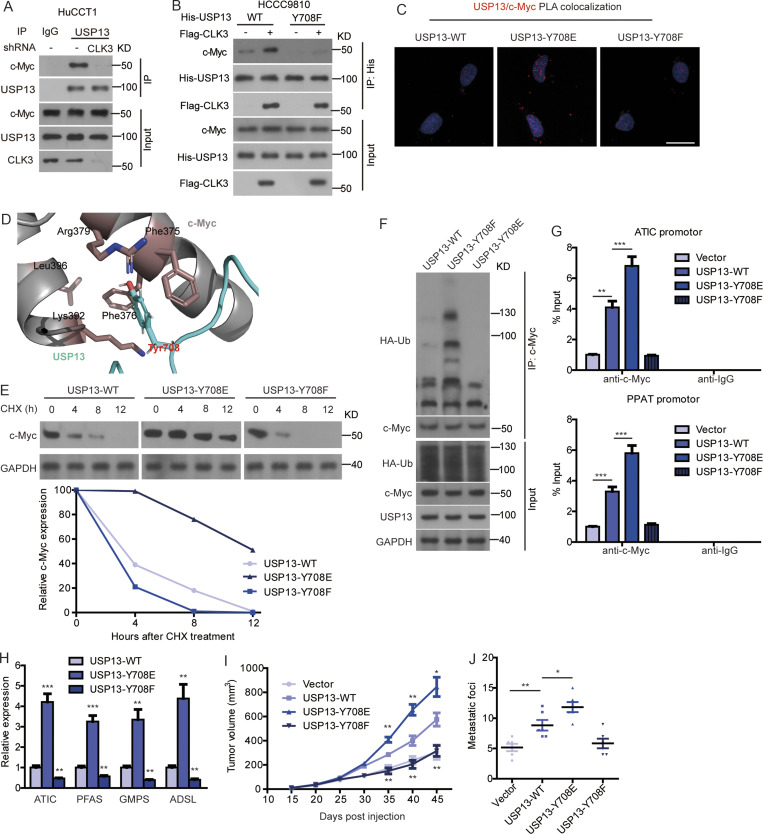

CLK3-dependent phosphorylation of USP13 at Y708 promotes CCA progression by activating c-Myc–mediated purine synthesis

We then examined the physiological significance of USP13 phosphorylation by CLK3 at Y708. Fig. 6 A indicates that CLK3 knockdown in HuCCT1 cells strongly impaired the interaction of USP13 with c-Myc. However, overexpression of CLK3 in HCCC9810 cells promoted the binding of c-Myc to WT-USP13, not USP13-Y708F mutant (Fig. 6 B). Proximity ligation assay further confirmed these findings (Fig. 6 C). Computational modeling of structures predicted in ZDOCK and Pymol software showed that Y708 phosphorylation was necessary for the direct binding of USP13 to c-Myc (Fig. 6 D).

Figure 6.

CLK3-dependent phosphorylation of USP13 at Y708 promotes CCA progression by activating c-Myc–mediated purine synthesis. (A) Knockdown of CLK3 blocked the interaction of USP13 with c-Myc in HuCCT1 cells treated as indicated with MG132. (B) HCCC9810 cells were transfected with His-WT-USP13 or USP13-Y708F or together with Flag-CLK3 and treated with MG132. Co-IP was performed using His antibody. (C) Proximity ligation assay indicating the binding of USP13 to c-Myc in HCCC9810 cells. Bar, 50 µm. (D) Computational molecular docking to analyze the molecular mechanism by which USP13-Y708 phosphorylation was involved in its interaction with c-Myc. Based on the prediction in ZDOCK and Pymol software, Y708 of USP13 lay in the interface between c-Myc and USP13, and Y708 phosphorylation greatly enhanced the binding affinity of USP13 to c-Myc by increasing hydrophilic forces. (E) HEK293T cells were transfected with WT-USP13 or phospho mutants and then treated using CHX. Western blotting was performed as indicated. (F) HEK293T cells were treated with WT-USP13 or phospho-deficient or phosphomimetic mutant with HA-tagged ubiquitin and MG132. Western blotting was performed to determine c-Myc ubiquitination. (G) ChIP assays from HCCC9810 cells treated as indicated. (H) Quantitative RT-PCR in samples treated as indicated. (I and J) The impacts of WT-USP13 and its phosphorylation mutants on CCA growth and metastasis using mice model. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (A–C, E, and F) or are from three independent experiments (G–J; mean ± SEM). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (I) or one-way ANOVA (G, H, and J). KD, knockdown; PLA, proximity ligation assay; TUBA, alpha tubulin.

CHX chase assays indicated that overexpression of WT-USP13, particularly a phosphomimetic USP13-Y708E, but not USP-Y708F, significantly up-regulated the half-time of the c-Myc protein in HEK293 cells (Fig. 6 E). Consistently, USP13-Y708E transfection in HEK293 cells significantly inhibited c-Myc ubiquitination, while USP13-Y708F significantly increased it (Fig. 6 F). As expected, USP13-Y708E transfection in HEK293 cells significantly inhibited the binding of c-Myc to Fbxl14, while USP13-Y708F significantly increased it (data not shown), revealing that USP13 phosphorylation at Y708 reverts c-Myc ubiquitination mediated by Fbxl14, thereby enhancing its stability (Fig. 6 F).

The expression of USP13-Y708E but not USP13-Y708F mutant significantly promoted the recruitment of c-Myc on the promoters of purine-associated enzymes (Fig. 6 G), consequently enhancing their expression (Fig. 6 H).

In vivo, the expression of WT-USP13, particularly USP13-Y708E construct in HCCC9810 cells, significantly enhanced the metastasis and growth of CCA cells, while the USP13-Y708F construct was resistant to carcinogenesis after implanting in nude mice (Fig. 6, I and J).

Therefore, we propose that CLK3-induced Y708 phosphorylation of USP13 promotes CCA progression by activating c-Myc–mediated purine synthesis.

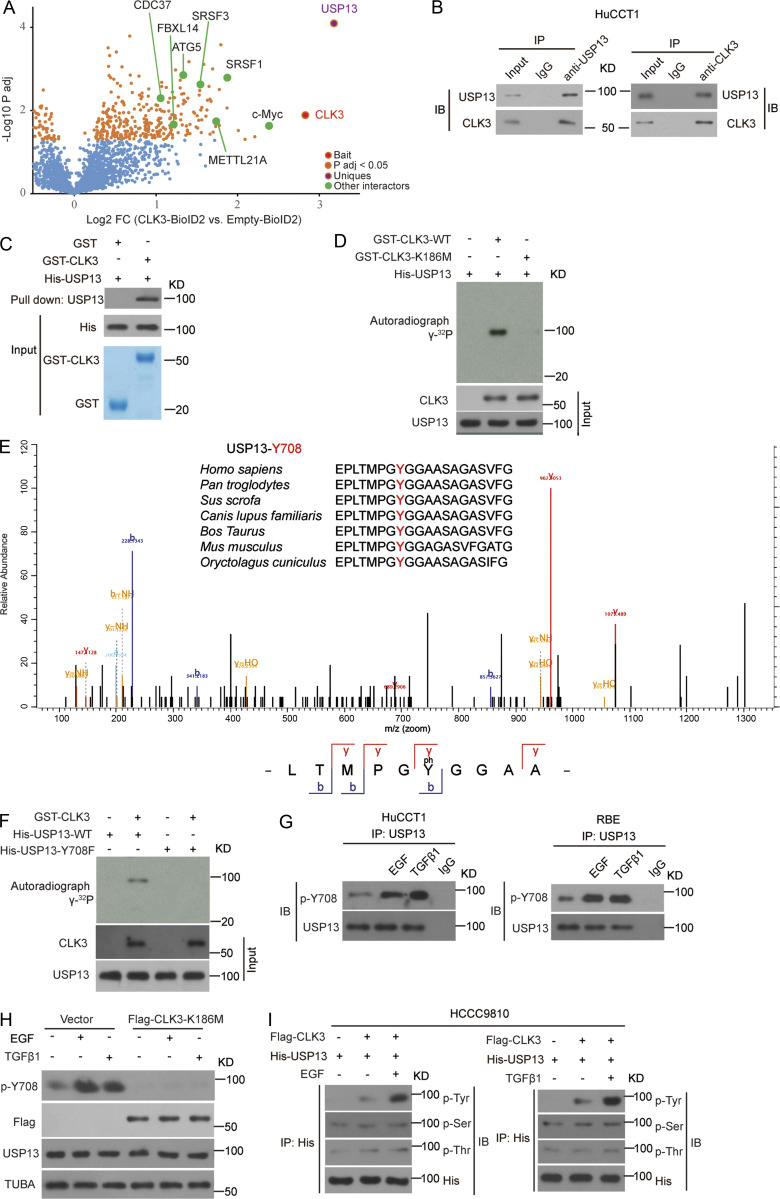

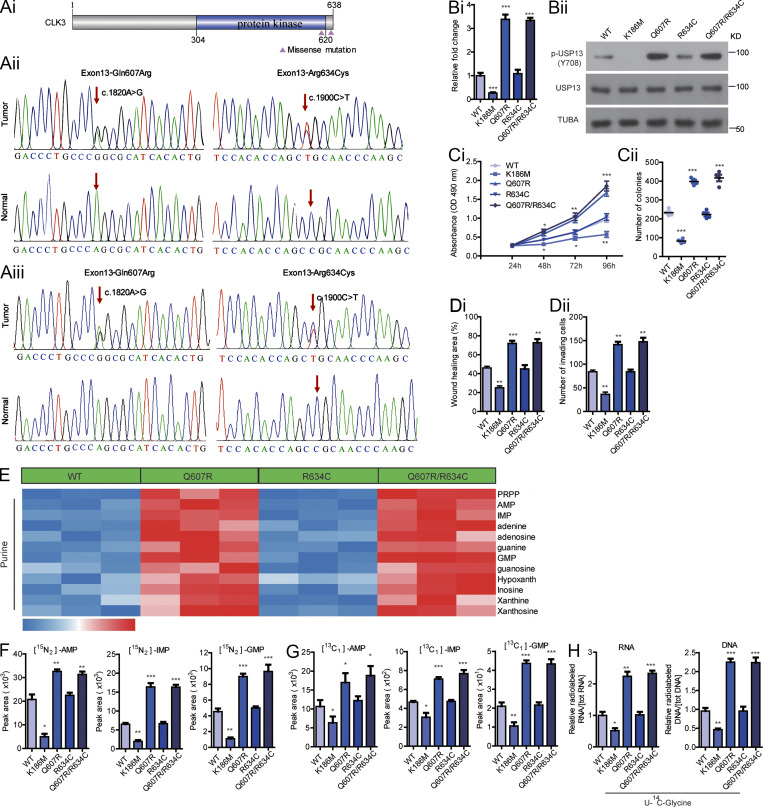

CLK3 is frequently mutated and activated in human CCA

To further uncover the clinical significance of CLK3 in CCA, we sequenced all exons of CLK3 to identify recurrent somatic mutations in a cohort of 100 CCA patients. As shown in Fig. 7, Ai and Aii, two missense mutations (Gln607Arg or Q607R and Arg634Cys or R634C) were identified in 8% of patients. Although Polyphen-2 analysis predicted that Q607R and R634C mutants might be benign (Adzhubei et al., 2013; Table S7), the clinical data analysis indicated that these mutations were closely associated with a higher level of CA19-9 and metastasis (Table S8). We verified the two missense mutations in another cohort of samples (Fig. 7 Aiii and Table S9). Particularly, given that the mutation Q607R happened in the kinase domain, we reasoned that this mutation might affect the kinase activity of CLK3.

Figure 7.

CLK3 is frequently mutated and activated in human CCA. (Ai) Schematic presentation of somatic mutations in CLK3 in 100 CCA patients. (Aii and Aiii) Sanger sequencing to identify CLK3 mutations in 100 (ii) and 75 (iii) human CCAs. Arrows indicate the location of the mutation in the tumor, but not in the tumor tissue. (B) IP kinase assay. Briefly, CLK3 was immunoprecipitated with anti-HA antibodies from HEK293 cells expressing WT-CLK3 or its mutants. The immunoprecipitated proteins mixed with the SRSF1 protein (a known substrate of CLK3) synthetic peptide and [γ-32P] ATP. The phosphocellulose paper assay was used to measure kinase activity. The results were normalized to 1.0 for WT-CLK3. (C) The effects of human CCA-associated CLK3 mutants on the proliferation and colony formation of HCCC9810 cells. (D) The impact of human CCA-associated CLK3 mutants on HCCC9810 cell wound healing and invasion. (E) Heatmap showing WT-CLK3 and its mutants in CCA patients on purine metabolism in HCCC9810 cells. (F–H) The effects of WT-CLK3 and its mutants in CCA patients on purine intermediates in HCCC9810 cells. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (Bii and E) or are from three independent experiments (Bi, C, D, and F–H; mean ± SEM). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (Ci) or one-way ANOVA (Bi, Cii, D, and F–H). AMP, adenosine monophosphate; GMP, guanosine monophosphate; IMP, inosine monophosphate; TUBA, alpha tubulin.

As expected, the Q607R mutant greatly increased the activity of CLK3, while R634C had no noticeable effect (Fig. 7 Bi). The Q607R mutant also up-regulated USP13 phosphorylation at Y708 (Fig. 7 Bii). Importantly, overexpression of WT-CLK3 or CLK3–Q607R/R634C mutant significantly promoted aggressiveness compared with CLK3-K186M overexpression in HCCC9810 cells, while the enhancing effect of the Q607R but not the R634C mutant was significantly bigger than in WT (Fig. 7, Ci–Dii). As expected, the enhancing effect of the Q607R but not the R634C mutant on the purine synthesis pathway was significantly bigger than in WT (Fig. 7, E–H; and Table S10).

Therefore, our findings indicate that the oncogenic effect of CLK3 is often activated by its Q607R mutation in CCA patients.

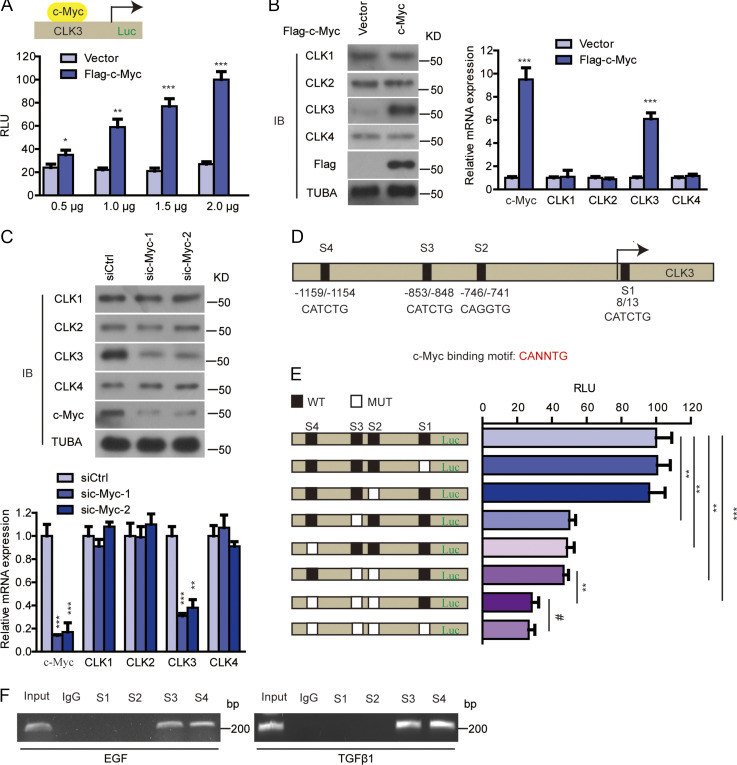

c-Myc enhances transcriptional activation of the CLK3 promoter in CCA cells

As an important transcription factor, c-Myc overexpression was found to enhance CLK3 promoter activity and expression, while the other member of the CLK family was not affected (Fig. S4, A and B). Silencing c-Myc had the opposite effect (Fig. S4 C).

Figure S4.

c-Myc enhances transcriptional activation of CLK3 promoter in CCA cells. (A) HEK293T cells were overexpressed with empty vector or Flag–c-Myc with or without CLK3-Luc (−1,328 bp) reporter as indicated. Relative luciferase activity was measured and normalized based on CMV-LacZ expression. (B) Flag–c-Myc or empty vector was transfected into HCCC9810 cells. 24 h later, we performed quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting (IB) assays. (C) siRNA against c-Myc or scramble was transfected into HuCCT1 cells. 24 h later, we performed quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting assays. (D) Positions of four putative c-Myc–binding motifs (E-box) relative to the transcription start in the CLK3 promoter are indicated. (E) The effect of mutating each of four putative c-Myc–binding sites on the luciferase reporter of CLK3 promoter in HEK293T cells transfected with a c-Myc. Relative luciferase activity was measured. (F) EGF- or TGFβ1-treated HuCCT1 cells were used to perform ChIP with c-Myc antibody. PCR was performed using primers flanking four putative E-box sites of the CLK3 promoter. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, not significant. Data are mean ± SEM and are from three (A, B, right panel; C, lower panel; and E) independent experiments or are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (B, left panel; C, upper panel; and F). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (A and B) or one-way ANOVA (C and E). TUBA, alpha tubulin.

Although four possible c-Myc–binding E-boxes were in the sequence of the CLK3 promoter (Fig. S4 D), only mutation of site 3 or 4 inhibited c-Myc–induced CLK3 expression (Fig. S4 E). Physiologically, EGF or TGFβ1 treatment promoted the recruitment of c-Myc to sites 3 and 4 in the CLK3 promoter in HuCCT1 cells (Fig. S4 F). Together, our data show that c-Myc is a transcriptional activator of CLK3.

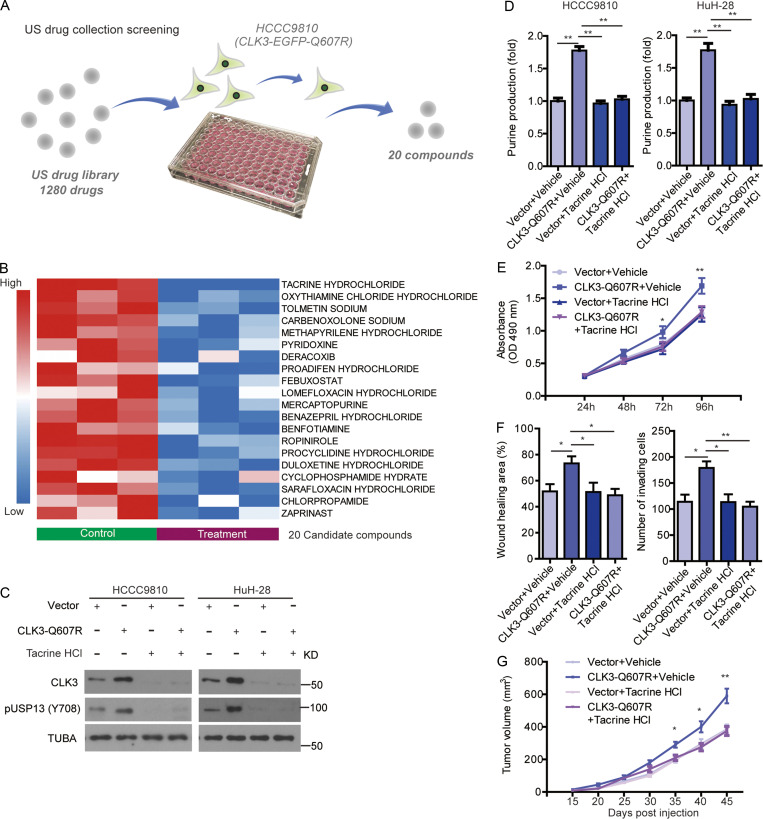

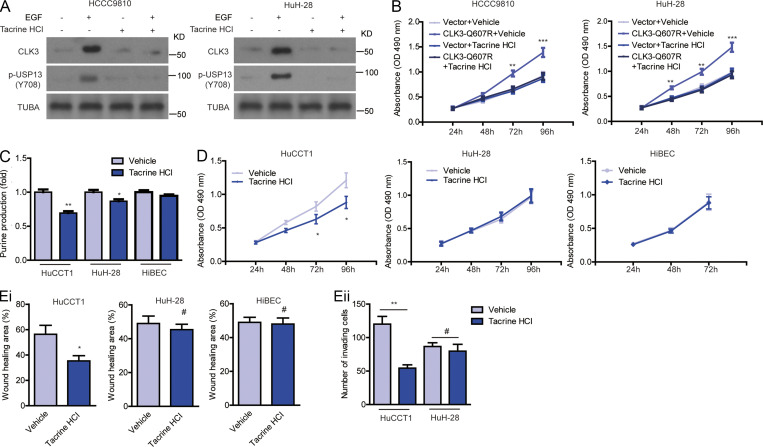

Tacrine hydrochloride inhibits CCA with aberrant CLK3 expression

Finally, we tried to screen therapeutic agents against CCA with aberrant CLK3 expression or Q607R mutant. 1,280 compounds from the US drug collection were respectively added to HCCC9810 cells stably expressing EGFP-CLK3-Q607R (Fig. 8 A). The results indicated that 20 compounds decreased the fluorescence of CLK3-Q607R, with tacrine hydrochloride being the highest hit (Fig. 8 B). Further analysis found that tacrine hydrochloride significantly decreased CLK3-Q607R–enhanced purine production and USP13-Y708 phosphorylation in CCA cells (Fig. 8, C and D). Tacrine hydrochloride also inhibited the proliferation and invasion of HCCC9810 cells stably expressing the CLK3-Q607R mutant (Fig. 8, E and F). Similar data were also observed in the EGF-induced increase in CLK3 expression, USP13 phosphorylation at Y708, and proliferation in CCA cells (Fig. S5, A and B). Furthermore, we compared the effect of tacrine hydrochloride on HuCCT1 with HuH-28 and HiBEC. The results showed that HuCCT1 was more sensitive to tacrine hydrochloride than HuH-28 and HiBEC (Fig. S5, C–E).

Figure 8.

Tacrine hydrochloride inhibits CCA with aberrant CLK3 expression. (A) Schematic representation of screening CLK3 inhibitors using the US drug collection. pEGFP-CLK3-Q607R mutant was stably transfected into HCCC9810 cells, which then were treated with 1,280 drugs. The compounds were screened based on change in fluorescence intensities. (B) 20 candidate drugs are shown by heatmap of CLK3 levels. (C) HCCC9810 and HuH-28 cells stably expressing CLK3-Q607R or empty vector were treated with tacrine hydrochloride for 24 h. Immunoblotting was performed as indicated. (D) Measuring the levels of purine in HCCC9810 and HuH-28 cells treated as indicated. (E and F) The effect of tacrine hydrochloride on the aggressiveness of HCCC9810 cells stably expressing CLK3-Q607R mutant. (G) The effect of tacrine hydrochloride on CCA growth in mice treated as indicated. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01. Data are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (B and C) or are from three independent experiments (D–G; mean ± SEM). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (E and G) or one-way ANOVA (D and F). TUBA, alpha tubulin.

Figure S5.

Tacrine hydrochloride inhibits CCA with aberrant CLK3 expression. (A and B) Tacrine hydrochloride inhibited the EGF-induced increase in CLK3 expression, USP13 phosphorylation at Y708 (A), and proliferation in HCCC9810 and HuH-28 cells (B). (C) Measuring the levels of purine in HuCCT1, HuH-28, and HiBEC cells treated as indicated. (D and E) The effect of tacrine hydrochloride on the growth (D) and migration (E, i) of HuCCT1, HuH-28, and HiBEC cells and on the invasion (Eii) of HuCCT1 and HuH-28 cells. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; #, not significant. Data are mean ± SEM and are from three (B–E) independent experiments or are representative of three independent experiments with similar results (A). P values were calculated using unpaired Student’s t test (B–E). TUBA, alpha tubulin.

In vivo, tacrine hydrochloride significantly inhibited the growth of CCA in mice with CLK3-Q607R overexpression (Fig. 8 G). Therefore, tacrine hydrochloride might be a candidate compound for the treatment of human CCA with aberrant CLK3 expression or mutant.

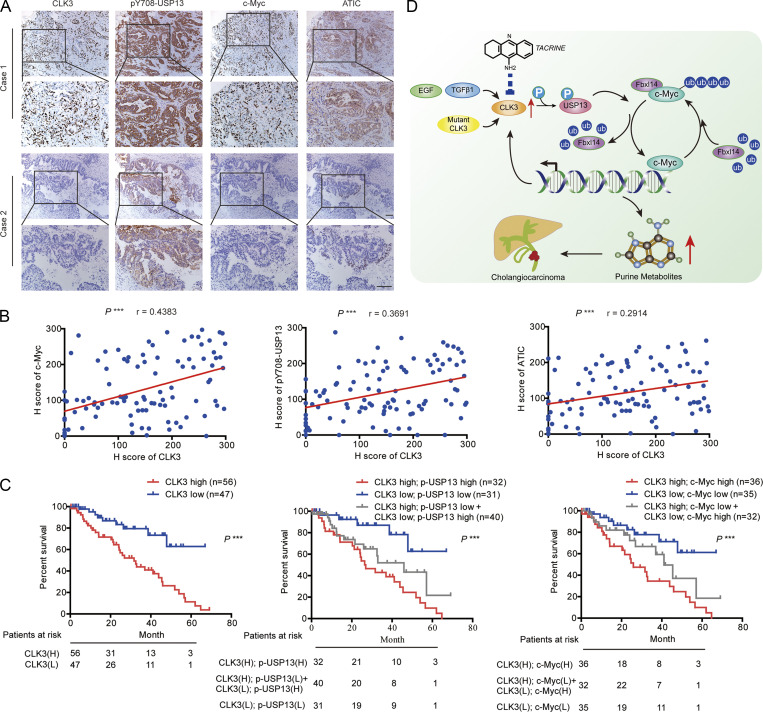

Clinical correlations between CLK3, p-USP13–Y708, c-Myc, and ATIC in CCA patients’ tissues

To further reveal the clinical significance of our data, we examined the associations between CLK3, p-USP13–Y708, c-Myc, and ATIC in 103 CCA patients’ samples. The immunohistochemistry (IHC) assays indicated a significant positive correlation between these markers (Fig. 9 A and Table S11). These findings were further validated using Pearson analysis (Fig. 9 B). Kaplan-Meier data indicated that the high levels of CLK3, p-USP13–Y708, and c-Myc in CCA significantly correlated with poor OS (Fig. 9 C). Another independent cohort of CCA patients also presented similar results (data not shown). Together, these findings suggest that targeting the CLK3/USP13/c-Myc feedback loop might be critical in treating human CCA (Fig. 9 D).

Figure 9.

Clinical correlations between CLK3, p-USP13–Y708, c-Myc, and ATIC in CCA patients’ samples. (A) The pictures show CLK3, p-USP13–Y708, c-Myc, and ATIC protein expression in two human CCA specimens. Bars, 100 µm. (B) Pearson correlation coefficient analysis about the expression of CLK3, p-USP13–Y708, c-Myc, and ATIC protein in patients with CCA (n = 103) by IHC. ***, P < 0.001. (C) OS data from CCA patients stratified by the level of CLK3 with p-USP13–Y708 or c-Myc. ***, P < 0.001; Kaplan-Meier analysis. (D) EGF or TGFβ1 or human CCA-associated CLK3 mutant activates CLK3 and thereby enhances p-Y708 levels of USP13; this event significantly increases the association of USP13 with c-Myc and disrupts Fbxl14-mediated c-Myc ubiquitination, which activated the de novo purine biosynthesis pathway and promoted the development of CCA. Interestingly, activated c-Myc transcriptionally up-regulated CLK3 expression. Finally, tacrine hydrochloride inhibits aberrant CLK3-induced CCA. H, high; L, low.

Discussion

This report uncovered for the first time an important role of CLK3 kinase in the reprogramming of CCA metabolism. We demonstrated that (1) a recurrent Q607R somatic substitution in CLK3 was identified in 8% of 100 human CCAs, particularly in patients with CCA metastasis; (2) the expression of CLK3 was significantly up-regulated in CCA compared with matched control tissues; (3) CLK3 knockdown significantly inhibited CCA aggressiveness in vitro and in vivo; (4) gene ontology term enrichment and MS assays indicated that high CLK3 expression in CCA patients mainly regulated nucleotide metabolism, especially purine biosynthesis; (5) mechanistically, CLK3 directly phosphorylated USP13 at Y708, which promoted its binding to c-Myc, a critical purine synthesis–associated transcription factor, thereby preventing Fbxl14-mediated c-Myc ubiquitination and activating the transcription of purine metabolic genes; (6) the CCA-associated CLK3-Q607R mutant induced USP13-Y708 phosphorylation and enhanced the activity of c-Myc; (7) in turn, c-Myc transcriptionally up-regulated CLK3; (8) importantly, levels of CLK3 significantly correlated with the expression of phospho-USP13-Y708, c-Myc, and ATIC in human CCA specimens; and (9) tacrine hydrochloride was identified as a potential compound to inhibit the aberrant CLK3-enhanced CCA invasiveness. Together, our data elucidate a previously unrecognized mechanism that is operational in CCA, thus providing a new and viable therapeutic strategy for CCA harboring CLK3 mutation.

Many genetic driver mutations in CCA have been identified by large-scale parallel sequencing studies, most notably those affecting p53, EGFR, and KRAS (Chong and Zhu, 2016). However, our knowledge about the genetic driver genes in CCA remains limited. In this study, our cellular and genetic studies not only identified CLK3 as an additional significantly mutated gene in CCA but also demonstrated the CLK3-Q607R mutant as a gain-of-function mutation in CCA patients that accelerates oncogenic CLK3-driven CCA progression. These findings therefore suggest CLK3 mutation is a typical driver that facilitates CCA development by activation of the purine synthesis signaling pathway. Future studies should examine whether this mutation-activating CLK3 happens in other tumor types.

Notably, only one Q607K substitution in the entire COSMIC database can be found, and no R634 mutation is reported, even though we did not find its functional effect on CCA. Possible reasons why the R634 mutation was not found before are as follows. (1) Although >500 CCA samples have been included in COSMIC, they cannot represent overall CCA incidences. Therefore, it is still possible for undiscovered mutations to be identified. In fact, COSMIC, as the largest resource for mutation, has been constantly updated to include new mutation data. (2) Genomic background may affect mutation status, although mutation information on CCA in COSMIC comes from three studies, none of which includes Chinese samples. However, in our study, we used Chinese CCA samples.

Understanding the functional consequences of genetic driver mutations dramatically facilitates the development of targeted cancer therapies. When a US drug collection approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) was exploited, tacrine hydrochloride was identified as one candidate that effectively down-regulated the CLK3 level in CCA. Tacrine hydrochloride is a cholinesterase inhibitor and has been approved by the FDA to treat Alzheimer’s disease (de los Ríos and Marco-Contelles, 2019). Interestingly, a recent study reported that tacrine or its derivative displayed strong anticancer ability (Qin et al., 2018), which is consistent with our findings. Given that in a clinical setting, tacrine hydrochloride had been demonstrated to have good safety and high potency, it might become a candidate drug for treating human CCA. And it also might serve as a useful tool in CLK3-related research. Although our preliminary data indicated the effects of anti-CCA by tacrine hydrochloride, the detailed mechanism by which tacrine hydrochloride decreased CLK3 expression and its preclinical application in CCA definitely needs to be further explored.

The functional and targeted therapeutic study against CLK3 is reminiscent of the Dyrk kinase family. First, sequence analysis of the catalytic domains of proteins from this superfamily showed that CLK3 forms a sister group with the Dyrk family, and literature confirmed that CLK3 kinase shares a high sequence homology with the Dyrk kinase family (Tomás-Loba et al., 2019). Second, similar to CLK3, the Dyrk family has very important effects on the nervous system. Notably, inhibiting Dyrk1A has been shown to be a potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease (Stotani et al., 2016). Third, the Dyrk family also modulates metabolic disorders and cancers. Several Dyrk family inhibitors, such as harmine, have been known to be effective anticancer agents (Uhl et al., 2018). Fourth, our recent study reported that Dyrk3 inhibits liver cancer by impairing purine synthesis (Ma et al., 2019). These findings indicate that structural and sequencing similarities suggest a functional similarity between CLK and Dyrk kinase families (Schmitt et al., 2014), which will be very helpful for us in uncovering the unrecognized function of the CLK family. Considering their similarities, it is tempting to hypothesize that Dyrk family inhibitors might affect CLK3 function. Future studies are needed to test this hypothesis, which may provide new insights into the CLK3 signaling network in CCA.

By using the basic online tool Gepia (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/) to analyze the CCA TCGA dataset in this study, we indicate that CLK3 is overexpressed in CCA. However, when using cBioPortal, another online tool, CLK3 was not up-regulated in virtually all CCAs. How can this discrepancy be explained? We think there are at least two reasons. First, the sample number of CCAs analyzed by using these two basic online tools (Gepia and cBioPortal) was totally different. Second, cBioPortal does not contain any expression data from normal tissue samples.

Additionally, by analyzing the public Oncomine database, we found that genomic DNA of CLK3 is also frequently amplified in esophageal carcinoma and gastric cancer (data not shown). However, KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) function pathway analysis did not indicate its involvement in purine synthesis (data not shown). Based on these findings, we speculate that CLK3-mediated purine metabolism may be unique in CCA, while CLK3 may be involved in esophageal carcinoma and gastric cancer carcinogenesis by other alternative mechanisms. For instance, (1) CLK3 was reported to regulate HMGA2 splicing through SRSF1, which affects stem cell development (Cesana et al., 2018), and (2) CLK3 contributed to tumor progression via activating the Wnt/β–catenin signaling pathway (Li et al., 2019). Our MS data also suggest that CLK3 may regulate tumor-related autophagy. If this is the case, future studies should explore other possible Myc-independent mechanisms in diverse tumor types, including CCA.

In summary, CLK3 may represent a unique type of kinase that is essential for the de novo purine synthesis of CCA cells. This confirmation strongly supports the potential of CLK3 as a therapeutic target in CCA, which will provide a new approach toward the treatment of this devastating disease. Our research also suggests that tacrine hydrochloride, an FDA-approved drug for Alzheimer’s disease treatment, can be repurposed for CCA treatment. Future studies in higher-animal models for CCA are required for further pharmacological confirmation.

Materials and methods

Cell culture, reagents, and antibodies

HEK293T, normal human intrahepatic epithelial cholangiocyte (HiBEC; as a control), and CCA cell lines (HuCCT1, RBE, HuH-28, and HCCC9810) were provided by Shanghai Cell Bank of the Chinese Academy of Science, ScienCell, and American Type Culture Collection or as a gift from Dr. Bing Wang at Rutgers University (New Brunswick, NJ). FBS, 13C-glycine, X-film, and 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) were from Millipore and Sigma. Protease inhibitor cocktail was obtained from Santa Cruz. 14C-glycine was from Perkin Elmer. Lipofectamine 2000, PBS, antibiotics, and DMEM were purchased from Invitrogen. Tween 20 and X-film were provided by Sigma. The Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent) was QuikChange II. Alexa Fluor 488 Phalloidin was from Thermo Fisher. The antibodies were listed as follows: anti–glutathione S-transferase (GST) antibody (Abcam; #ab19256), anti-Flag M2-conjugated agarose was from Sigma, anti-His (Abcam; #ab18184), CLK3 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; #sc-365225), ADSL (GeneTex; #GTX84956), Fbxl14 (Sigma; #SAB2103691), ATF4 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; #sc-390063), CLK2 (Abcam; #ab86147), GAPDH (Abcam; #ab9485), c-Myc (Abcam; #ab39688), ATIC (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; #sc-53612), MITF (Abcam; #ab20663), CLK1 (Abcam; #ab74044), GMPS (Abcam; #ab135538), CLK4 (Abcam, #ab67936), PFAS, (Abcam; #ab251740), phosphoserine (Abcam; #ab9332), Tubulin (Abcam; #ab18251), USP13 antibody (Bethyl Laboratories; #A302-762A), phosphothreonine (Abcam; #ab9337), phosphotyrosine (Abcam; #ab10321), phosphoserine/threonine (Abcam #ab17464), and secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad; #1706515 and #1706516). P-USP13–Y708–specific antibody was made by this laboratory using similar methods as described previously (Hong et al., 2018).

Screening of compounds against CLK3

CLK3-Q607R mutant was stably transfected into HCCC9810 and HuH-28 cells. Then, these cells were cultured using 96-well plates to 50% confluence. Then, 1 µM 1,280 drugs from the US drug collection were individually added to each well. After 12 h, the CCA cells were washed with PBS, and fluorescence intensity was measured to determine the levels of CLK3 in transfected CCA cells.

Transfection, constructs, shRNA, and siRNA

For Tet-inducible overexpression of CLK3, we used the Tet-On 3G Inducible Expression System (Clontech) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, CLK3 cDNA or flag-CLK3 was cloned into a Tet-inducible vector, pTRE3G (Clontech), and HCCC9810 or HuH-28 cells were stably transfected with pCMV-Tet-3G plasmid (500 µg/ml of G418, for 2 wk) using Xfect transfection reagent (Clontech) to generate Tet-On 3G cell lines. Then, the Tet-On 3G cell lines were transfected with pTRE3G-CLK3 under puromycin selection (1 µg/ml, for 2 wk) to generate double-stable Tet-On 3G inducible cell lines. For Tet-inducible knockdown of CLK3, two different shRNAs against CLK3 (shCLK3-#1 and #2) were respectively cloned into pLVCT-tTR-KRAB (Addgene; plasmid #11643) in which we replaced GFP with puromycin. For transfection, as previously reported (Zhu et al., 2019), HuCCT1 and RBE cells were transduced through spinoculation with pLVCT-tTR-KRAB-shCLK3 and pLVCT-tTR-KRAB-shcontrol lentivirus particles at a multiplicity of infection ∼1. About 2 wk of antibiotics selection (1 µg/ml) later, stable polyclonal CCA cell lines with shcontrol or shCLK3 were established. The cells above were maintained in the absence or presence of Dox conditions depending on the experimental requirement. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used to perform siRNA transfection for siATF4, siMyc, siMITF, or scramble negative control (Invitrogen) following the protocol. Immunoblots were used to determine the efficiency of knockdown at 2 d after transfection. All siRNA and shRNA, which were from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, were as follows: shCLK3-#1: 5′-AGTCAGACATCAAGACACAC-3′; shCLK3-#2: 5′-GAUGCUUGAUCUUGCACAATT-3′; or shcontrol: 5′-AATGCTCGCACAGCACAAG-3′; siMITF: 5′-GAAACUUGAUCGACCUCUACA-3′; siATIC: 5′-CAGUCUAACUCUGUGUGCUACGCCA-3′; siATF4: 5′-CCACGUAUGACACUUGdTdT-3′; sic-Myc #1: 5′-TCCGTACAGCCCTATTTCA-3′; and sic-Myc #2: 5′-GTTCTAATTACCTCATTGTCT-3′. CLK3, c-Myc, and USP13 constructs were purchased from GeneChem. Mutants or truncated fragments from different genes, such as CLK3 and USP13, were constructed as described previously (Hong et al., 2014), and sequencing was used to verify the resulting mutants.

The sample collections of CCA patients

In this study, tissue samples of all CCA patients and corresponding nontumor samples were collected from 2012 to 2017 at the Affiliated Hospitals, Anhui Medical University and Harbin Medical University. This study ethic was passed by the Harbin Medical University Institute Research Ethics Committee. Each CCA participant signed the informed consent. All tumor tissues for RNA isolation and IHC were histopathologically confirmed by a pathologist. Tumor-node-metastasis, a cancer staging system, was used to define the histological type and cancer stage according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (seventh edition).

Western blot

CCA tissues or cell lines were collected using the lysis buffer radioimmunoprecipitation assay as previously described (Song et al., 2018). bicinchoninic protein reagent (Pierce) was used to measure protein concentration. Denaturing 10% SDS-PAGE separated all samples, which were then transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane. After blocking using tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 containing 5% milk for 1 h, the indicated primary antibody was added on polyvinylidene fluoride membranes at 4°C overnight. As previously described (Qu et al., 2016), the secondary antibody was added, and enhanced chemiluminescence reagents (Pierce) were applied to visualized blots.

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP)

As described (Qu et al., 2016), the indicated antibodies were added to 500 µg of precleared samples and were rotated at 4°C for ∼8 h Then A&G beads (Sigma) were mixed with the samples for 3 h. Finally, the immunoprecipitation (IP) complexes were subjected to blot analysis.

PCR

TRIzol (Thermo Fisher) was purchased to purify indicated RNA from CCA cells or CCA tissues. Then, random primers and the Reverse Transcription Kit (Invitrogen) were purchased for RT of total RNA into cDNA. Subsequently, RT-PCR was finished by Applied Biosystems. Primers for the respective genes were synthesized by Invitrogen. The relative levels of indicated proteins were analyzed through the 2−ΔΔCt method. The endogenous control was GAPDH. All primer sequences are: CLK1: 5′-ACAAGACATTATAGAGCACCGGA-3′ and 5′-GTGGTCCAAGAATCCTTTCCATC-3′; USP13: 5′-GCGAAATCAGGCTATTCAGG-3′ and 5′-TTGTAAATCACCCATCTTCCTTCC-3′; CLK2: 5′-CGAACACTATCAGAGCCGAAAG-3′ and 5′-GAACGTGGTAGCTGTCCTCC-3′; CLK3: 5′-CGTACCTGAGCTACCGATGGA-3′ and 5′-TCCCTTCGGGACGGGTATC-3′; CLK4: 5′-ATGCGGCATTCCAAACGAAC-3′ and 5′-GTACTGCTGTGAGACCTTCTCT-3′; ATF4: 5′-TTCTCCAGCGACAAGGCTAAGG-3′ and 5′-CTCCAACATCCAATCTGTCCCG-3′; GMPS: 5′-ATGGCTCTGTGCAACGGAG-3′ and 5′-CCTCACTCTTCGGTCTATGACT-3′; PFAS: 5′-CCCAGTCCTTCACTTCTATGTTC-3′ and 5′-GTAGCACAGTTCAGTCTCGAC-3′; ADSL: 5′-TAGCGACAGGTATAAATTCC-3′ and 5′-TCTCCTGCCCTTGCTTTCCT-3′; GART: 5′-GGAATCCCAACCGCACAATG-3′, and 5′-AGCAGGGAAGTCTGCACTCA-3′; ATIC: 5′-CACGCTCGAGTGACAGTG-3′ and 5′-TCGGAGCTCTGCATCTCCG-3′; c-Myc: 5′-AATGAAAAGGCCCCCAAGGTAGTTATCC-3′ and 5′-CGTACTGGAGAGTTCCGGTTTG-3′; RPL21: 5′-CAAGGGAATGGGTACTGTTCAAA-3′ and 5′-CTCGGCTCTTAGAGTGCTTAATG-3′; RPL18: 5′-ATGTGCGGGTTCAGGAGGTA-3′ and 5′-CTGGTCGAAAGTGAGGATCTTG-3′; RPS15: 5′-CCCGAGATGATCGGCCACTA-3′ and 5′-CCATGCTTTACGGGCTTGTAG-3′; RPL27: 5′-TGGCTGGAATTGACCGCTAC-3′ and 5′-CCTTGTGGGCATTAGGTGATTG-3′; NOP10: 5′-CAGTATTACCTCAACGAGCAGG-3′ and 5′-GGCTGAGCAGGTCTGTTGTC-3′; POP5: 5′-ATGGTGCGGTTCAAGCACA-3′ and 5′-GAACTCGGTCATCGAGGCTTA-3′; IPM3: 5′-CCCTGACGTGGTTACCGAC-3′ and 5′-CCGCTTGATCTTGGACGAGT-3′; and GAPDH: 5′-GCCCAATACGACCAAATCC-3′ and 5′-CACCACATCGCTCAGACAC-3′.

In vivo deubiquitination

Indicated constructs were transfected into indicated cells for 48 h. Before these cells were collected, 5 µg/ml MG132 (Bio-Rad) was added and incubated for ∼4 h. Then, cells were lysed in denaturing buffer containing 0.1 M NaH2PO4 and Na2HPO4, 6 M guanidine-HCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 400 mM Tris-HCl. These lysates were mixed with nickel beads for 3 h at cold room temperature. Finally, immunoblotting was performed with the indicated antibodies.

Metabolite assays

Liquid chromatography–tandem MS (LC-MS/MS) was used to analyze intracellular metabolites of indicated cells as described previously (Ben-Sahra et al., 2016). Briefly, glycine-free DMEM was used to wash the indicated cells, and then cells were added with the same medium containing 400 µM [13C1]-glycine for 30 min. Metabolites were extracted using 4 ml 80% methanol on dry ice. After spinning at 4000 ×g at 4°C, the insoluble pellets were isolated by 0.5 ml 80% methanol via spinning at 20,000 ×g at 4°C. An N-EVAP from Organomation Associates was used to dry the metabolites under nitrogen gas. 10 µl of HPLC-grade water was added to the resuspended pellets, and then MS analysis was performed. Finally, AB/SCIEX, a Multi Quant v2.0 software program, was used to analyze the metabolite SRM (selected reaction monitoring) transition. The SRMs were used to analyze the incorporation of 15N or 13C by LC-MS/MS.

Detection of CLK3 mutations by Sanger sequencing

We first isolated DNA from tissues using the High Pure PCR Template Preparation Kit (Roche; #11796828001). DNA amplification was performed by conventional PCR with CLK3 mutation analysis by direct Sanger sequencing. The PCR primers were supplied by Sangon Biotech, and the PCR mixture included 0.2 mM deoxy-ribonucleoside triphosphate, 0.2 µM primer, 10× PCR buffer, Platinum Taq DNA Polymerase, and 1.5 mM Mg2+ (Invitrogen; #15966005). PCR was performed as follows: 94°C for 2 min, 94°C for 30 s, ∼60°C for 30 s (depending on primer melting temperature), and 72°C for 1 min (for 35 cycles). After confirmation of the band of interest, the PCR products were purified using the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen; #28104) and then sent for sequencing by Tsingke. All of the primers used for independent amplification of 13 exons of CLK3 are listed in Table S12.

Identifying CLK3-binding proteins and USP13 phosphorylation sites by MS

BioID2-based screening was used to identify CLK3-binding proteins as described previously (Kim et al., 2016). Briefly, myc-BioID2-CLK3 or myc-BioID2 was stably transfected into HCCC9810 cells. 50 mM biotin was added to the medium of these cells for 2 d. Then, proteins were extracted by spinning and keeping the supernatant. Biotinylated proteins were purified by using AssayMap streptavidin cartridges. Finally, LC-MS/MS analysis was performed, and USP13 phosphorylation sites were identified as described previously (Caporarello et al., 2017).

Soft agar assay

Soft agar experiments were performed as previously described (Ma et al., 2019). Briefly, CCA cells were cultured in the top agar (0.4%) in 6-well plates (5,000 cells per well). After ∼3 wk, 0.05% crystal violet was used to stain colonies for 1 h. A digital camera was used to count the colonies. All experiments were repeated in at least triplicates.

Cell invasion assays

For invasion assays, transwell assay with 8-µm pores and Matrigel (Corning) were used to measure the invasive ability of CCA cell lines. Briefly, after 48 h of transfection, the indicated 2 × 104 cells per well were cultured in the upper chamber with 100 µl of medium without FBS. Then, 500 µl of medium was added to the lower chambers, including 10% FBS, which acted as a chemoattractant. 24 h later, a cotton swab was used to wipe off cells left on the upper membrane while keeping the invaded cells. After fixing in 4% formaldehyde, 1% crystal violet was used to stain the invaded cells. An inverted microscope (Nikon) was used to count 10 random visual fields.

MTT assay

Briefly, ∼1 × 104 cells were cultured in 12-well plates. 4 µg/ml Dox was added to the medium for 3 d. Then, at 37°C, 1 ml of MTT reagent was added to treat the cells for 30 min, and 1 ml of acidic isopropanol was added. At 595 nm, the absorbance was analyzed with background subtraction at 650 nm.

Wound-healing (scratch) experiments

Experiments were done as described previously (Mereness et al., 2018). Briefly, indicated cells were cultured on coated 12-well plates at 3 × 105 per well and grown to confluence for 24 h. A pipette tip was used to vertically scratch a monolayer in each well. At 0 and 24 h, images of the scratch were taken.

GST pulldown assay

As previously described (Song et al., 2014), Escherichia coli was used to express GST-fusion proteins. Then, isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactoside induced their expression. Proteins were purified using glutathione-sepharose 4B beads purchased from Sigma. GST-tagged CLK3 or USP13 and GST (around 10 µg) were cross-linked by dimethyl pimelimidate dihydrochloride to glutathione-sepharose in reaction buffer, pH 8.0. After elution with sample buffer, Coomassie staining and Western blot were used to analyze the samples.

Luciferase reporter assays

As described previously (Song et al., 2019), we cultured HEK293T cells to perform the dual-luciferase reporter assays. Briefly, using Lipofectamine 2000 overnight after plating, 0.2 µg of the firefly promoter luciferase reporter constructs (WT-CLK3 or CLK3 mutant promoter) was cotransfected with the indicated plasmids. The control group was PGL-TK Renilla luciferase plasmid. The activity was monitored via the Dual-Luciferase System bought from Promega, and luciferase activity was averaged from three replicates.

Chromatin IP (ChIP)

As described (Song et al., 2019), the primers that were adopted for c-Myc motif are: 5′-GACGGAGTTTTGCTCTCTTG-3′ and 5′-CTGCCTCCCGGGTTTAAGTG-3′; 5′-CTCCCACCTCAGCCTCC-3′ and 5′-AGGCGCGTGCCACCACGTCT-3′; 5′-CATGTTGGCCAGACTGGTCT-3′ and 5′-GCCTCCCAAAGTACTGGGAT-3′; and 5′-CTCAAAAGATCCCCACCTCA-3′ and 5′-GCCTCGTAATCCTGTCCGAC-3′.

Mice xenograft experiments and metastasis model

In accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines, mice experiments were performed; the Institutional Animal Committee at Anhui Medical University and Harbin Medical University approved the animal protocols. For the xenograft or metastasis model, 106 Dox-inducible knockdown or overexpression of CLK3 cells with their corresponding control cells were subcutaneously or intraperitoneally or intravenously injected into 4–6-wk-old BALB/c nu/nu mice (n = 6–10/group). Mice were given drinking water containing 2 mg/ml Dox and 10% sucrose for inducible knockdown or overexpression of CLK3. The xenograft tumors or metastatic peritoneal or metastatic lung tumors were monitored at the indicated time points after injection. At the indicated time, the size and volume of the tumor were calculated as described previously (Qu et al., 2016).

Tissue arrays and IHC staining

CCA tissue microarray was purchased from Alenabio Company, and IHC staining was performed for CLK3 as described previously (Hong et al., 2018). IHC staining was evaluated and scored using the scale 0, 1+, 2+, and 3+ representing no staining, weak staining, moderate staining, and strong staining, respectively. The final H-score was calculated based on the formula reported previously (Ma et al., 2019). The indicated protein levels were defined by H-score, and then low- and high-expression patient groups were divided.

IP kinase analysis

As described before (Bankston et al., 2017), an IP kinase assay was done. Briefly, the lysate (1 mg) was mixed with anti-HA antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; #sc-57592). 24 h later, protein G–agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology; #sc2002) were added. The immunocomplexes were resuspended in buffer containing 1 mm Na3VO4. Using the phosphocellulose paper assay, the immunoprecipitated CLK3 activity was examined as follows. One synthetic peptide (1 mM) derived from the SRSF1 protein phosphorylation site (a known substrate of CLK3) was added as a substrate in the mixture (0.4 mM ATP, 1 mm Na3VO4, 20 mM Tris, [γ32P] ATP, pH 7.4, and 10 mM MgCl2). 30 min later at 30°C, 10% trichloroacetic acid terminated the reaction. Then the mixtures were loaded as a dot on the p81 phosphocellulose paper. Scintillation counting was used to determinate incorporation of 32P into the peptide.

TCGA and Gene Expression Omnibus analysis

Whole-genome RNA sequencing data about the CCA TCGA dataset were downloaded using the Xena Functional Genomics Explorer website (https://xenabrowser.net). Patients with unavailable survival data were excluded. The relevant clinical characteristics, including age, gender, pathological tumor-node-metastasis, disease stage, survival time, and censor, were obtained from the TCGA dataset. We used Gepia (http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/), an interactive web server for analyzing the RNA sequencing expression data of tumors and normal samples from the TCGA and the Genotype Tissues Expression projects (Tang et al., 2017), to examine CLK3 expression in CCA. These TCGA data of CCA include 36 tumor samples and nine normal samples. According to user instructions of this online tool, the results are presented with log2(TPM+1; TPM means transcripts per million) and analyzed by using Student’s t test. The mRNA array data about CLK3 analysis in CCA are publicly available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (accession no. GSE26566). The expression pattern was plotted using GraphPad Prism 5 software.

In vitro kinase assay

1 µg recombinant CLK3 protein and purified WT-USP13 or its mutant proteins were mixed with 1X reaction buffer containing 10 µM ATP and 0.2 mM Na3VO4 and 10 µCi [γ-32P] ATP. The reaction proceeded at 30°C for 15 min. Then, the mixtures were separated and the incorporated [γ-32P] radioisotope was detected by using the imaging plate–autoradiography system.

BrdU assay

Briefly, indicated cells (∼4,000 cells/well) were plated into a 96-well plate. After 24 h, the proliferation of CCA cells was examined using a chemiluminescent BrdU kit (Sigma) as described by the manufacturer.

Statistics

The results from two groups were compared using Student’s t test. When comparing data from groups greater than two, we used one-way ANOVA. To analyze the growth curves, we used two-way ANOVA. Pearson correlation analysis was used to elucidate the correlation of two proteins. Programs for GraphPad Prism 5, R software package (version 3.0.0), and Social Sciences software 20.0 were used. Determining Kaplan-Meier data required the log-rank test. Data were reported through mean ± SD, performed in at least triplicates. *, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, and **, P < 0.01 or ***, P < 0.001 was considered very significant; # indicates no significance.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows that CLK3 in CCA is significantly up-regulated and is associated with decreased OS and acts as an oncogene. Fig. S2 shows that CLK3 promotes purine synthesis and CCA progression through enhancing the stabilization and nuclear translocation of c-Myc. Fig. S3 shows that CLK3 interacts with USP13 and that CLK3 expression was up-regulated on EGF or TGFβ1 treatment. Fig. S4 documents that c-Myc enhances transcriptional activation of the CLK3 promoter in CCA cells. Fig. S5 shows that tacrine hydrochloride inhibits CCA with aberrant CLK3 expression. Table S1 describes the relationship between CLK3 expression and clinicopathological features of CCA patients. Table S2 shows univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with survival in CCA patients. Table S3 shows the top 500 differentially expressed genes with high CLK3 expression. Table S4 shows metabolic profiling of CCA cells with or without CLK3 knockdown. Table S5 summarizes ribosome-related genes among the 500 up-regulated genes in Table S3. Table S6 documents the CLK3-interacting proteins. Table S7 and Table S9 document the CLK3 mutations. Table S8 shows the relationship of CLK3 mutation with clinicopathological features of CCA. Table S10 shows purine metabolite profiling of WT and mutant HCCC9810 cells. Table S11 describes the relationship between CLK3 or p-USP13–Y708 or c-Myc expression and clinicopathological features of CCA patients. Table S12 lists the primers for Sanger sequencing.

Supplementary Material

shows the relationship between CLK3 expression and clinicopathological features of CCA patients (n = 100).

describes the univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with survival in CCA patients (n = 100).

lists the top 500 differentially expressed genes with CLK3 up-regulation.

shows MS-based metabolic profiling of HuCCT-1 cells expressing shCtrl and shCLK3 with or without c-Myc in the presence or absence of Dox.

lists genes that are associated with ribosomal biogenesis among the 500 up-regulated genes.

identifies CLK3-interacting proteins via MS.

shows the systematic investigation of mutation of CLK3 in 100 CCA samples.

shows the relationship of CLK3 mutation with clinicopathological features of CCA (n = 100).

presents the systematic investigation of mutation of CLK3 in 75 CCA samples.

lists MS-based purine metabolites profiling WT and mutant HCCC9810 cells.

shows the relationship between CLK3 or p-USP13–Y708 or c-Myc expression and clinicopathological features of CCA patients (n = 103).

lists all primers used for independent amplification of 13 exons of CLK3.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 81702387, no. 81702744, and no. 81960520), the Science and Technology Planned Project in Guilin (20190206-1), the Guangxi Distinguished Experts Special Fund (2019-13-12), the Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (no. 2017J01368 and no. 2017J01369), the Training Program for Young Talents of Fujian Health System (no. 2016-ZQN-85), Fujian Provincial Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists (no. 2018D0016), the Fujian Health Education Joint Research Project (WKJ2016-2-17), the Heilongjiang Postdoctoral Science Foundation (LBH-Z17176), the Science and Technology Foundation of Shenzhen (JCYJ20170412155231633 and JCYJ20180305164128430), the Shenzhen Economic and Information Committee “Innovation Chain and Industry Chain” integration special support plan project (20180225112449943), the Shenzhen Public Service Platform on Tumor Precision Medicine and Molecular Diagnosis, and the Shenzhen Cell Therapy Public Service Platform.

Author contributions: Q. Zhou, M. Lin, X. Feng, and F. Ma acquired and analyzed experimental data. Y. Zhu, X. Liu, C. Qu, H. Sui, H. Huang, B. Sun, H. Zhang, A. Zhu, J. Sun, Z. Gao, Y. Zhao, J. Jin, and Y. Bai provided administrative, technical, or material support. Z. Zhang, X. Hong, and C. Zou designed the study, and Z. Zhang drafted the manuscript.

References

- Adzhubei I., Jordan D.M., and Sunyaev S.R.. 2013. Predicting functional effect of human missense mutations using PolyPhen-2. Curr. Protoc. Hum. Genet. Chapter 7:20 10.1002/0471142905.hg0720s76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bankston A.N., Ku L., and Feng Y.. 2017. Active Cdk5 Immunoprecipitation and Kinase Assay. Bio Protoc. 7 e2363 10.21769/BioProtoc.2363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Sahra I., Hoxhaj G., Ricoult S.J.H., Asara J.M., and Manning B.D.. 2016. mTORC1 induces purine synthesis through control of the mitochondrial tetrahydrofolate cycle. Science. 351:728–733. 10.1126/science.aad0489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler E., Porazinski S., Uzor S., Thibault P., Durand M., Lapointe E., Rouschop K.M.A., Hancock J., Wilson I., and Ladomery M.. 2018. Hypoxia leads to significant changes in alternative splicing and elevated expression of CLK splice factor kinases in PC3 prostate cancer cells. BMC Cancer. 18:355 10.1186/s12885-018-4227-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caporarello N., Lupo G., Olivieri M., Cristaldi M., Cambria M.T., Salmeri M., and Anfuso C.D.. 2017. Classical VEGF, Notch and Ang signalling in cancer angiogenesis, alternative approaches and future directions (Review). Mol. Med. Rep. 16:4393–4402. 10.3892/mmr.2017.7179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesana M., Guo M.H., Cacchiarelli D., Wahlster L., Barragan J., Doulatov S., Vo L.T., Salvatori B., Trapnell C., Clement K., et al. 2018. A CLK3-HMGA2 alternative splicing axis impacts human hematopoietic stem cell molecular identity throughout development. Cell Stem Cell. 22:575–588.e7. 10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong D.Q., and Zhu A.X.. 2016. The landscape of targeted therapies for cholangiocarcinoma: current status and emerging targets. Oncotarget. 7:46750–46767. 10.18632/oncotarget.8775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Los Ríos C., and Marco-Contelles J.. 2019. Tacrines for Alzheimer’s disease therapy. III. The PyridoTacrines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 166:381–389. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2019.02.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X., Zhou W., Wu Q., Huang Z., Shi Y., Yang K., Chen C., Xie Q., Mack S.C., Wang X., et al. 2017. Deubiquitinase USP13 maintains glioblastoma stem cells by antagonizing FBXL14-mediated Myc ubiquitination. J. Exp. Med. 214:245–267. 10.1084/jem.20151673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong X., Song R., Song H., Zheng T., Wang J., Liang Y., Qi S., Lu Z., Song X., Jiang H., et al. 2014. PTEN antagonises Tcl1/hnRNPK-mediated G6PD pre-mRNA splicing which contributes to hepatocarcinogenesis. Gut. 63:1635–1647. 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong X., Huang H., Qiu X., Ding Z., Feng X., Zhu Y., Zhuo H., Hou J., Zhao J., Cai W., et al. 2018. Targeting posttranslational modifications of RIOK1 inhibits the progression of colorectal and gastric cancers. eLife. 7 e29511 10.7554/eLife.29511 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Kim D.I., Jensen S.C., Noble K.A., Kc B., Roux K.H., Motamedchaboki K., and Roux K.J.. 2016. An improved smaller biotin ligase for BioID proximity labeling. Mol. Biol. Cell. 27:1188–1196. 10.1091/mbc.E15-12-0844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Cui X., Hu Q., Chen X., and Zhou P.. 2019. CLK3 Is A Direct Target Of miR-144 And Contributes To Aggressive Progression In Hepatocellular Carcinoma. OncoTargets Ther. 12:9201–9213. 10.2147/OTT.S224527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma F., Zhu Y., Liu X., Zhou Q., Hong X., Qu C., Feng X., Zhang Y., Ding Q., Zhao J., et al. 2019. Dual-Specificity Tyrosine Phosphorylation-Regulated Kinase 3 Loss Activates Purine Metabolism and Promotes Hepatocellular Carcinoma Progression. Hepatology. 70:1785–1803. 10.1002/hep.30703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks E.I., and Yee N.S.. 2016. Molecular genetics and targeted therapeutics in biliary tract carcinoma. World J. Gastroenterol. 22:1335–1347. 10.3748/wjg.v22.i4.1335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maroni L., Pierantonelli I., Banales J.M., Benedetti A., and Marzioni M.. 2013. The significance of genetics for cholangiocarcinoma development. Ann. Transl. Med. 1:28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mereness J.A., Bhattacharya S., Wang Q., Ren Y., Pryhuber G.S., and Mariani T.J.. 2018. Type VI collagen promotes lung epithelial cell spreading and wound-closure. PLoS One. 13 e0209095 10.1371/journal.pone.0209095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayler O., Stamm S., and Ullrich A.. 1997. Characterization and comparison of four serine- and arginine-rich (SR) protein kinases. Biochem. J. 326:693–700. 10.1042/bj3260693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin Q.-P., Wang S.-L., Tan M.-X., Wang Z.-F., Luo D.-M., Zou B.-Q., Liu Y.-C., Yao P.-F., and Liang H.. 2018. Novel tacrine platinum(II) complexes display high anticancer activity via inhibition of telomerase activity, dysfunction of mitochondria, and activation of the p53 signaling pathway. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 158:106–122. 10.1016/j.ejmech.2018.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C., He D., Lu X., Dong L., Zhu Y., Zhao Q., Jiang X., Chang P., Jiang X., Wang L., et al. 2016. Salt-inducible Kinase (SIK1) regulates HCC progression and WNT/β-catenin activation. J. Hepatol. 64:1076–1089. 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt C., Miralinaghi P., Mariano M., Hartmann R.W., and Engel M.. 2014. Hydroxybenzothiophene ketones are efficient pre-mRNA splicing modulators due to dual inhibition of Dyrk1A and Clk1/4. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 5:963–967. 10.1021/ml500059y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song R., Song H., Liang Y., Yin D., Zhang H., Zheng T., Wang J., Lu Z., Song X., Pei T., et al. 2014. Reciprocal activation between ATPase inhibitory factor 1 and NF-κB drives hepatocellular carcinoma angiogenesis and metastasis. Hepatology. 60:1659–1673. 10.1002/hep.27312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Feng X., Zhang M., Jin X., Xu X., Wang L., Ding X., Luo Y., Lin F., Wu Q., et al. 2018. Crosstalk between lysine methylation and phosphorylation of ATG16L1 dictates the apoptosis of hypoxia/reoxygenation-induced cardiomyocytes. Autophagy. 14:825–844. 10.1080/15548627.2017.1389357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song H., Feng X., Zhang H., Luo Y., Huang J., Lin M., Jin J., Ding X., Wu S., Huang H., et al. 2019. METTL3 and ALKBH5 oppositely regulate m6A modification of TFEB mRNA, which dictates the fate of hypoxia/reoxygenation-treated cardiomyocytes. Autophagy. 15:1419–1437. 10.1080/15548627.2019.1586246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stotani S., Giordanetto F., and Medda F.. 2016. DYRK1A inhibition as potential treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Future Med. Chem. 8:681–696. 10.4155/fmc-2016-0013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugihara T., Isomoto H., Gores G., and Smoot R.. 2019. YAP and the Hippo pathway in cholangiocarcinoma. J. Gastroenterol. 54:485–491. 10.1007/s00535-019-01563-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Z., Li C., Kang B., Gao G., Li C., and Zhang Z.. 2017. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(W1):W98–W102. 10.1093/nar/gkx247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás-Loba A., Manieri E., González-Terán B., Mora A., Leiva-Vega L., Santamans A.M., Romero-Becerra R., Rodríguez E., Pintor-Chocano A., Feixas F., et al. 2019. p38γ is essential for cell cycle progression and liver tumorigenesis. Nature. 568:557–560. 10.1038/s41586-019-1112-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]