Abstract

The Harmonized Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia for Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI–DAD) is a population-representative, prospective cohort study of late-life cognition and dementia. It is part of an ongoing international research collaboration that aims to measure and understand cognitive impairment and dementia risk by collecting a set of cognitive and neuropsychological assessments and informant reports, referred to as the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP). LASI–DAD provides nationally representative data drawn from a subsample of the ongoing Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI). One of LASI–DAD’s distinctive features is its rich geriatric assessment, including the collection of venous blood samples and brain imaging data for a subsample of respondents. In this paper, we discuss the methodological considerations of developing and implementing the HCAP protocol in India. The lessons we learned from translating and applying the HCAP protocol in an environment where illiteracy and innumeracy are high will provide important insights to researchers interested in measuring and collecting data on late-life cognition and dementia in developing countries. We further developed an innovative blood management system that enables us to follow the collection, transportation, assay, and storage of samples. Such innovation can benefit other population surveys collecting biomarker data.

Introduction

Rising life expectancy is contributing to rapid increases in the size of the older population and is expected to lead to a sharp rise in prevalence of dementia, from about 47 million people worldwide today, to potentially more than 140 million in 2050 (Livingston et al. 2017). The epidemic scale of dementia given an aging global population has led to an intensified effort to advance dementia research. Reflecting these priorities, the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health issued a call for applications to develop comparable cognition and dementia measures across countries with different levels of economic development, which gave rise to an international research collaboration that seeks to measure and understand dementia risk using the existing population survey platform of the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) family of nationally representative studies. To foster cross-country comparisons, this research network has promoted the use of the Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP), which consists of a carefully selected set of established cognitive and neuropsychological assessments and informant reports. In this paper, we discuss the methodological considerations given to and the lessons learned from designing and implementing the HCAP protocol in India.

The Longitudinal Aging Study in India (LASI) is a nationally representative, multidisciplinary panel study on aging in India, which is designed to be conceptually comparable to the HRS in the United States and appropriately harmonized with other HRS sister studies. LASI also include a set of policy relevant questions, particularly measuring the awareness and coverage of a variety of government programs (including health insurance, various old-age programs, etc.), as well as questions designed to capture unique institutional and cultural characteristics, such as caste, yoga. Taking advantage of its rich data and nationally representative sampling frame, we drew a subsample of 3,891 respondents aged 60 and older from LASI for an in-depth study of late-life cognition and dementia.

The aims of the LASI–Diagnostic Assessment of Dementia (DAD) are to (1) estimate the prevalence of dementia and mild cognitive impairment (MCI); (2) contribute to a better understanding of the determinants of late-life cognition, cognitive aging, and dementia; and (3) study the impact of dementia and MCI on families and society. To accomplish these aims, we developed a protocol to assess dementia and MCI by evaluating the suitability of the HCAP protocol, developed by the HRS–HCAP (Weir, Langa, and Ryan 2016), and the 10/66 protocol (Prince et al. 2007), and by considering other protocols used in India, including the Hindi Mental State Exam (Ganguli et al. 1995) and the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences’ Neuropsychological Battery (Tripathi et al. 2013). In this paper, we discuss the steps we have taken to ensure quality data collection to assess late-life cognitive function and dementia risk.

Further, we enriched our project protocol by conducting geriatric assessments to enable further investigation of risk factors for dementia and late-life cognitive impairment, including collecting venous blood samples (VBS) and neuroimaging data. We will discuss the innovative blood management scheme we developed to track VBS and the challenges we faced in collecting neuroimaging data for a population survey.

Development of the HCAP for India

The LASI–DAD study is a collaborative project, led by the principal investigators from two institutions: the University of Southern California (USC), United States, and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, India. Before the official launch of the project, the project team conducted a feasibility study at AIIMS, New Delhi, in September 2014 to evaluate whether the HRS–HCAP could be used in collecting cognitive data from older adults in India. A sample of 22 subjects—12 with dementia and 10 without—were recruited from the AIIMS patient base. The HRS–HCAP; the LASI cognition module; and the 10/66 protocol, which was developed to assess dementia and late-life cognition in developing countries, including India, were administered, using the Computer-Assisted Personal Interview (CAPI). Five resident doctors from the Department of Geriatric Medicine, AIIMS, New Delhi, conducted the interviews after two days of training from the HRS and LASI training teams with expertise in administering cognitive tests and the CAPI. Twenty respondent interviews and 22 informant interviews were completed, demonstrating that respondents in India were able to complete most of the HRS–HCAP protocol. Respondents without dementia performed better than those with it in the cognitive tests administered, and the differences in the distributions of test scores suggested that the HRS–HCAP tests could have prognostic ability.

The LASI–DAD project was officially launched in December 2015. The project team solicited advice from an international advisory board that consists of expert researchers and collaborating institutions, including the International Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai, India; the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health; the University of Michigan; and the University of California, Los Angeles. The appointed project managers from USC and AIIMS attended a hands-on session of the HRS–HCAP interviewer training conducted at the University of Michigan in April 2016. Through this training, the LASI–DAD project managers fully familiarized themselves with the HRS–HCAP protocol, particularly the details entailed in cognitive test administration and the interviewing techniques needed for the informant interview.

The project team then evaluated the HRS–HCAP closely and modified it to suit India’s cultural milieu. For example, since many older adults in Indian are illiterate and/or innumerate, we replaced the Mini Mental State Exam (MMSE) by Folstein, Folstein, and McHugh (1975) with the Hindi version of the MMSE (HMSE) developed by Ganguli et al. (1995). Modifications also reflect considerations for cultural or contextual constraints. For example, there is considerable geographic variation with respect to the presence of cacti across India, so LASI-DAD respondents are instead asked about coconut in the object-naming test in a modified version of the Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status (TICS) by Brandt, Spencer, and Folstein (1988). Another component of TICS that asks the name of the President of the United States was changed to ask the name of the Prime Minister of India. The story from the Logical Memory tests were modified to use Indian names and streets and to reflect local context. We further considered cognitive and neuropsychological test batteries developed by the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences, Bengaluru, India, and consulted with other experts in the field, including geriatricians, community medicine experts, psychiatrists, cognitive psychologists, and members of the HRS–HCAP advisory group.

The cognitive tests were translated into 10 languages – Assamese, Bengali, Hindi, Kannada, Malayalam, Marathi, Odiya, Tamil, Telugu, and Urdu. A rigorous process of forward and backward translation was conducted for each of the 10, with the aim of minimizing any differences that could arise due to language. The data received during pre-tests were scrutinized carefully to look for differences in response to translated questionnaires from different regions, and relevant changes were made accordingly.

We conducted two pre-tests: the first pre-test was carried out in November 2016 in New Delhi, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh, and the second in February 2017 in Kerala, Karnataka, and Rajasthan. Several amendments were made to the protocol based on the observations and feedback received from these two pre-tests. For example, in the HRS–HCAP CERAD word list memory and recall test (CERAD 1987), subjects viewed 10 high-imagery words for two seconds each. The subject reads each word aloud as it was presented and then was tested on an immediate recall procedure and later on a delayed recall procedure and on recognition. This was difficult for us to adapt due to illiteracy and respondents’ visual impairment due to advanced age. Additionally, during the pre-tests we learned that respondents found a computer voice reading the words to be more difficult to comprehend. As a result, we decided to modify this test by asking the interviewers to read each word to the respondent who was asked to repeat each word aloud, and was then tested on immediate recall. The respondent was presented with the same list three times in different orders and was asked to recall as many words as possible after every presentation. After roughly five minutes, the respondent was asked again to recall as many words from the initial list as possible to get a score for delayed recall.

Some tests had to be omitted to avoid redundancy. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment test (MOCA) by Nasreddine et al. (2005) was initially included and was taken out after the first pre-test because many items were repetitions of other cognition tests like MMSE and TICS. Additionally, some questions in MOCA like the animal-naming tests had pictures of animals like rhinoceros, which the majority of participants could not answer as this animal is not commonly seen in India. Similarly, we administered both the black-and-white Raven’s test (Raven 2000), which is a part of the HRS–HCAP study, and a coloured version of the Raven’s test (Colour Matrix Progression), which is considered to be easier and to work better in illiterate populations. From the phase 1 data, we observed respondents’ fatigue doing two versions of the Raven’s test done one after another, in which they performed worse on the coloured version, as it was administered after the black-and-white version. Therefore, we kept only the black-and-white version of the Raven’s test.

However, we added a digit span forward and backward test (Wechsler 1997) in addition to the HRS–HCAP cognitive test batteries. The test helps in studying the attention and psychomotor speed domain of cognition.

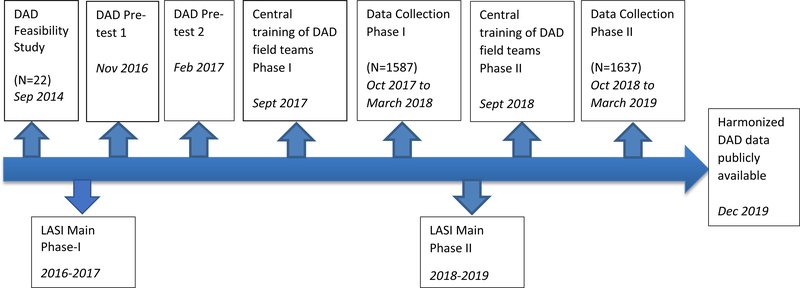

After the two pre-tests, the cognitive test protocol was finalized for the main data collection, which started in October 2017. A summary of the fieldwork timeline is presented in Figure 1. We selected the tests listed in Table 1 after the rigorous pre-tests. Administering these cognitive tests took an average of 1 hour to complete. The selected tests cover the essential domains required to diagnose major neurocognitive disorder or dementia as stated in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders or DSM-V (American Psychiatric Association 2013) guidelines; these domains are complex attention (symbol cancellation, digit span, and Go–No Go test), executive function (Raven’s matrices, clock drawing), learning and memory (CERAD word recall, logical memory), language (object naming, animal naming, Community Screening Interview for Dementia), and perceptual motor function (constructional praxis).

Figure 1.

Timeline of fieldwork for LASI-DAD.

Table 1.

Cognitive tests selected for LASI–DAD

| Test Name | Description | Domain tested |

|---|---|---|

| HMSE (Ganguli et al. 1995) | The HMSE is the Hindi translation and adaptation of the MMSE for screening the Hindi-speaking, illiterate rural elderly population. The HMSE (like the MMSE) assesses general cognitive status with measures of cognitive orientation, language, and memory. This test is often used in clinical and research settings to identify individuals with likely cognitive impairment or dementia. | Orientation to time and place; language: comprehension and expression, confrontation naming; visuo-constructional skill; immediate and delayed verbal recall; planning |

| TICS (Brandt, Spencer, and Folstein 1988) | This section includes three questions from the HRS–TICS. This includes questions to identify two words (vocabulary) and naming the Prime Minister of India (replacing the HCAP question about the name of the U.S. President and Vice President). This measure is based on the full TICS. | Language: responsive naming; semantic memory |

| Word learning and recall (CERAD 1987) | This test presents 10 high-imagery words for 2 seconds each. The respondent hears each word and repeats it aloud as it is presented and is then tested on an immediate recall procedure. The respondent is presented this list three times in different orders and is asked to recall as many words as possible after every presentation. In addition to correct recall responses, number of intrusions (words not on the list) are also recorded. We do the delayed recall 5 minutes after the first administration. | Verbal learning; immediate and delayed verbal memory |

| Digit span forward and backward (Wechsler 1997) | A list of random numbers is read out loud at the rate of one per second. Subjects listen to the series of single-digit numbers and are asked to repeat them back in the same order they were given. At the end of a sequence, they are asked to recall the items in reverse of the presented order. | Attention; working memory |

| Symbol cancellation (Lowery et al. 2004) | This test assesses attention and speed, specifically in the illiterate population. Subjects are given a sheet with different symbols. They are then shown a specific symbol, which is present among the different symbols in the sheet, and are asked to scan the sheet as quickly as possible (in a minute) and circle the symbol shown to them. Scores include the number of correctly and incorrectly circled symbols. | Attention and inattention; psychomotor speed; visual search |

| Logical memory (Wechsler 2009) | This section involves the reading of stories to the respondent and is scored based on the number of story points the respondent can immediately recall after hearing each story. The first story read to the respondent is the Brave Man story, included in many dementia studies around the world. The second story read to the respondent is one of two from the Wechsler Memory Scale (WMS-IV). | Immediate and delayed episodic verbal memory; recognition memory |

| Constructional praxis (with delayed recall) (Rosen, Mohs, and Davis 1984) | The constructional praxis tests the subject’s ability to copy four geometric forms of varying difficulty shown on a sheet of paper (circle, overlapping rectangles, diamond, and cube). In the delayed recall test, the subjects are asked to recall these shapes and draw them from memory after some time. | Visuospatial ability, visuo-constructional ability, spatial/nonverbal memory |

| Retrieval fluency (Woodcock, McGrew, and Mather 2001) | Animal naming asks respondents to name as many animals as possible in a minute. This measure assesses verbal retrieval and processing speed. Adapted by McArdle and Woodcock from the Woodcock Johnson Test III Tests of Achievement. | Language: word retrieval (category), fluency |

| Backward count (Agrigoroaei and Lachman 2011) | Respondents are asked to begin with the number 100 and to count back as fast as possible for 30 seconds. | Sustained attention; speed |

| Serial 7s (Ruesch 1944) | In this test, the respondent is asked to subtract seven from 100 in the first step and then asked to continue subtracting seven from the previous number in each subsequent step. All the subtractions are evaluated individually. This is also a part of MMSE. | Attention; speed |

| CSI-D (Hall, Hendrie, and Brittain 1993) | This series of questions derives from the 10/66 and Community Screening Interview for Dementia (CSI-D) surveys to assess cognitive impairment and dementia. The questions evaluate language, knowledge, and the ability to follow directions. | Language: confrontation naming, responsive naming, comprehension; semantic memory; spatial memory |

| Raven’s test (Raven 2000) | This test evaluates picture-based pattern reasoning of varying difficulty. Each question presents a geometric picture with a small section that appears to have been cut out. The respondent is shown a set of smaller pictures that fit the missing piece and is asked to identify which is the correct one to complete the pattern. We follow HRS–HCAP wherein they have selected a subset of 17 questions out of the 60 in the full test, including one practice question. | Nonverbal fluid intelligence |

| Go–No Go (Gomez, Ratcliff, and Perea 2007) | In this test, the respondent is given a task in which stimuli are presented in a continuous stream and participants perform a binary decision on each stimulus. One of the outcomes requires participants to make a motor response (go), whereas the other requires participants to withhold a response (no go). Accuracy is measured for each event. | Executive function: inhibiting a response, responding to feedback |

| Hand movement sequencing test (Mattis 1988) | In this test, the subject is shown hand-sequencing movements and is asked to repeat the action shown. The test is adopted from Hindi hand-sequencing movements, which were adapted from Mattis dementia rating scales. | Executive function: nonverbal planning and sequencing; gross motor movements |

| Token test (De Renzi and Vignolo 1962) | The subject is presented with a show card with tokens of different shapes, sizes, and colors. He/she is given verbal commands like touching the different colored tokens, different shapes, one shape or color before the other, etc. The commands start with simple tasks and progress to more complex ones. | Language: verbal comprehension |

| Judgment & problem solving (Morris, 1993) | The subject is asked to (1) identify similarities and differences between things and (2) describe what s/he would do if s/he find a lost child on road. | Judgment; problem solving |

Backward counting from 100 was tested during data collection in phase-1 states. The interviewer had difficulty counting the number of errors the participant made, as the errors could range from missing 1–2 numbers to skipping as many as 10 numbers. Proper scoring of this test turned out to be very difficult. Despite considerable efforts by the neuropsychologist to develop a consistent scoring rule, scoring continued to be an issue, and the test was subsequently dropped in the second phase of the study. In the second phase of data collection, we added the executive function and the judgement and problem-solving questions, as these domains were underrepresented in the questionnaire. The tests added were the hand-movement sequence (Mattis 1988) and the Token test (De Renzi and Vignolo 1962) for executive function (Table 1). A few similarities, differences, problem-solving questions, and simple numeric calculation tests were also added for the judgement and problem-solving section.

Informant Report.

The informant interview is another key component of the HCAP. It consists of questions about the respondent’s functional status, such as his/her ability to engage in activities of daily living (ADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL), social engagements, and memory. Closely following the HRS–HCAP, we conducted the pre-tests for the informant interview and did not run into any problems for our study sample. As with the HRS–HCAP, respondents were asked to nominate an informant, such as a close family member or friend who knows the respondent well, interacts with him/her frequently, and therefore knows his/her daily functions and can report on them. Informants are most likely to be spouses, partners, children, or long-time caregivers. The informant interview includes questions about the informant, particularly his/her relationship with the respondent and his/her own demographic characteristics; the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE) (Jorm and Jacomb 1989); Blessed Part 1 and 2 (Blessed, Tomlinson, and Roth 1968; Morris et al. 1989); questions about respondents’ activities; and signs of cognitive impairment drawn from the 10/66 Brief Screener for Dementia (Prince et al. 2007). We made only one modification from the HRS–HCAP protocol, administering the Blessed Part 1 instrument to everyone, instead of making the questions contingent to the answers to the Jorm IQCODE questions. The informant report took an average of about 30 minutes to complete, and most of the informant interviews were done face to face, but telephone interviews were allowed at the request of the informants.

Sample Design

The LASI–DAD sample was drawn from the LASI main study sample which is representative of both the nation and all of its 30 states and 6 Union Territories. Our target sample was 3,890 persons aged 60 years and above which would be representative of the country’s 60+ population. The 60-year age threshold was chosen to trace cognitive decline as people age, keeping in mind India’s life expectancy. According to WHO (2014), the remaining life expectancy at age 60 is 16 years for men and 18 years for women, which will allow tracking of their cognitive changes for an average of 17 years.

To obtain national representation within the budgetary constraints and maintain quality supervision of the fieldwork, we collaborated with 11 regional centers (RCs) and AIIMS, New Delhi, for interviewer recruitment and fieldwork management. AIIMS, New Delhi, was the nodal point that coordinated with all the other RCs and provided logistic support to all these centers. These centers were All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneshwar; Dr. SN Medical College, Jodhpur; Government Medical College, Thiruvananthapuram; Grant Medical College and J.J. Hospital, Mumbai; Guwahati Medical College, Guwahati; Institute of Medical Sciences, BHU Varanasi; Madras Medical College, Chennai; Medical College, Kolkata; National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru; Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad; and Sher-e-Kashmir Institute of Medical Sciences, Srinagar. Considering proximity to these RCs, we selected the samples from 14 states across the country. These 14 states were Assam, Delhi, Haryana, Jammu and Kashmir, Karnataka, Kerala, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Telangana, Uttar Pradesh, and West Bengal. AIIMS, New Delhi, also monitored the fieldwork at Haryana and Madhya Pradesh in addition to Delhi.

As our aim was to study dementia risk, a simple random sampling of age-eligible LASI respondents would not yield an adequate number of cognitively impaired respondents to allow for a sufficiently precise estimation of the relationship between dementia and its correlates. Therefore, we employed a two-stage stratified random sampling approach with oversampling of those at high risk of cognitive impairment to identify enough respondents with dementia and MCI. Using this approach, we first classified respondents into high and low risk of cognitive impairment based on the LASI main study’s cognitive tests and the proxy report for those who did not complete the cognitive tests. Specifically, cognitive impairment risk was determined based on the following criteria. We first grouped the LASI respondents into four groups based on age (60–69 and 70+) and education (no schooling and some education), which are two known risk factors of cognitive decline. We then defined cognitive impairment risk within age/education groups based on their relative performance of memory and non-memory cognitive tests, overall test performance, refusal or inability to participate in the cognitive tests, and proxy interviews in the main LASI. Respondents were classified as high risk if (1) overall cognitive test performance in the main LASI was in the bottom tertile, (2) memory score was in the bottom 15th percentile, (3) non-memory cognitive scores were in the bottom 15th percentile, (4) the number of missing cognitive tests was in the top 15th percentile, or (5) the IQCODE score was 3.9 or higher. We then randomly drew the sample with about equal numbers of those at high risk of cognitive impairment and those not at high risk.

On average, about four months after the baseline interview, we recruited the selected respondents and a close family member chosen by the respondent as an informant for interviews. Based on the respondents’ preference and their proximity to the hospital, the interview team, which consisted of clinical psychologists, social workers, and nurses, administered the HCAP protocol either at the hospital or in the respondent’s home setting. The field team sometimes travelled up to 12 hours by automobile to reach respondents residing in remote villages.

The original plan was to bring most participants to the hospital for assessments, which would serve as phenotyping units. Hospitals with geriatric units or having regional geriatric centers were preferred, as this would facilitate the geriatric assessment of the participants, which consisted of objective tests of functionality among other tests. However, respondents often had difficulty coming to the hospitals for several reasons, including disabilities and dependence on the availability of often busy caregivers. In such circumstances, we interviewed the respondents at their home and eventually gave the respondents a choice for where to be interviewed.

Protocol Enrichment for Epidemiological Research

As the LASI–DAD draws its sample from the main LASI survey, rich information on the respondents’ demographics, health, employment, social network, housing environment, household income, consumption, and wealth is already available. We further collected rich epidemiological data by conducting geriatric assessments, collecting venous blood specimens, and obtaining neuroimaging data for a subset of respondents.

Geriatric Assessment.

The geriatric instrument was put together by geriatricians of AIIMS, New Delhi and University of California, Los Angeles. It included specific physical measures like blood pressure; anthropometry, including height, weight, mid-arm circumference, calf circumference, and knee height; questions on Activities of daily living (ADL) (Mahoney & Barthel, 1965), Instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (Lawton & Brody, 1969); anxiety (Beck et al. 1988), depression (Radloff, 1977) and nutrition (Vellas et al. 1999); and performance tests, such as the Timed up and go test (Podsiadlo and Richardson 1991) and the Six-minute walk test (American Thoracic Society 2002); and a screening test for hearing impairment, using a Hearcheck Screener (Siemens, 2007). It is important to note that the 6-minute walk test was only administered for the hospital interviews due to the difficulty associated with administering the test in the community setting. The geriatric assessment takes an average of 25 minutes.

In older adults multiple morbidities are common, which leads to polypharmacy or prescription of multiple medicines. Though this is a common term used in geriatric clinics, the definition of polypharmacy remains ambiguous. The most commonly reported definition of polypharmacy is the consumption of five or more medications daily (Masnoon et al. 2017). We collected information regarding the number of medications the respondents take to assess the prevalence of polypharmacy in our sample. The participants were asked to show the interviewers all the medications they were taking so that they could record the names of the medicines. We are currently coding the collected data and sorting it into medication type for future analysis of drug intake and its potential association with cognition status.

Venous Blood Collection, Processing, and Assays.

We also collected and assayed venous blood specimens in partnership with Metropolis Laboratory, a leading independent pathology laboratory in India that offers a comprehensive menu of more than 4,500 tests in clinical chemistry, clinical microbiology, cytogenetics, haematology, molecular diagnostics, and surgical pathology and is accredited by the National Accreditation Board for Testing and Calibration Laboratories. The laboratory has branches and franchisees in each of the 14 states from where data would be collected. Metropolis Laboratory was responsible for providing a phlebotomist for blood draws, for conducting preliminary processing of the blood sample, and for transportation of the blood to the central laboratory in Delhi.

The LASI–DAD study team carried out centralized training of phlebotomists to emphasize proper techniques for aseptic blood collection; preliminary processing of samples at peripheral laboratories; and labelling, packaging, and maintenance of optimum temperature during the transportation of samples to the central laboratory. Temperature loggers were used to monitor the cold chain from the time of blood collection to its receipt in the central laboratory and to AIIMS, New Delhi. Temperature loggers (for 4 degrees and −20 degrees Celsius) were introduced to track the transfer of blood from its collection site to the testing lab. Table 2 breaks down the total blood collected in different tubes for different assays and their storage and transportation details. Every step was monitored for optimum temperature maintenance and time taken for transportation of sample. Whenever the standard time of 48 hours was exceeded, the personnel responsible were alerted by a system-generated email and trace the VBS samples and flag delays in VBS transportation to account for potential quality damage.

Table 2.

Venous blood specimens collected for bioassays and storage

| Collection tube | Blood volume | Vacutainer type | Tube destination | Shipping temperature (after processing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 3.5 ml | SST | Central Lab | 4°C |

| B | 3.5 ml | SST | Central Lab then AIIMS | 4°C |

| C | 3 ml | EDTA | Central Lab | 4°C |

| D | 2 ml | EDTA | Earmarked Genetic Lab | 4°C |

| E | 5 ml | Plasma preparation tube (EDTA) | Central Lab then AIIMS | −20°C |

Total: Five tubes and 17 mL of blood collected

ml: milliliters; SST: serum separation tube; EDTA: ethylene diamine acetic acid; °C: centigrade

A small amount of blood (2.5 ml) was transported to an earmarked genetic laboratory for future whole genome sequencing. The central Metropolis laboratory, after receiving the samples, segregated them for analysis at its location and sent serum, plasma, buffy coat, and dried blood spot cards to the Department of Geriatric Medicine, AIIMS, New Delhi, for storage in anticipation of future studies. A total of 17 ml of fasting blood (wherever possible) was collected from each participant. The blood-based assays done were complete blood counts; glycosylated hemoglobin; lipid panel; lipoprotein A; metabolic panel; homocysteine; Vitamin B12; folic acid; Vitamin D; thyroid-stimulating hormone; high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; and N-terminal pro-b-type natriuretic peptide.

Neuroimaging.

The LASI–DAD protocol collected neuroimaging data on a pilot basis for a subsample of respondents. This was the first attempt at implementing a neuroimaging protocol in a population survey, and we evaluated the feasibility for a multisite magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) study. The MRI acquisition protocol derives from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) 3 protocol and was developed and implemented in collaboration with the USC-based Laboratory of Neuro Imaging (LONI) team (Jack et al. 2008). Our clinical MRI sites included NIMHANS (Bangalore) and NM Medical Centre (Mumbai) using a 3.0 Tesla MRI scanner with 32-channel head coil. The core sequences included magnetization prepared rapid gradient echo (MP-RAGE) for morphometry, fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) for cerebrovascular disease pathology detection, high-resolution T2 structural imaging of the hippocampus for volumetric study, and multi-echo susceptibility-weighted imaging (SWI) for flow and mineral deposition quantification. We also included resting-state functional MRI to examine functional cortical connectivity and diffusion-weighted imaging for white matter tractography. The MRI protocol required around 55 minutes for completion.

Structural image analysis consisted of the Freesurfer analysis pipeline (Dale, Fischl, and Sereno 1999) and FMRIB’s Automated Segmentation Tool (FAST) (Zhang, Brady, and Smith 2001) and FIRST (Patenaude et al. 2011) in software package FMRIB Software Library (FSL) (Woolrich et al. 2009). Freesurfer’s surface-based analysis used each respondent’s 2x MP-RAGE and FLAIR scans to test for changes of volume, thickness, area, and curvature in the cortex between the various measures of interest. Voxel-based measures of subcortical structures was further supplemented with Freesurfer’s hippocampal subfield and nuceli of amygdala tool, which used the previous Freesurfer analysis along with the high-resolution T2 hippocampal scan. These analyses have been compared to voxel-based measures from FAST and FIRST in FSL. Thus far, the preliminary results have been similar between analysis pipelines.

Our current analyses of imaging data have focused on the temporal lobe, which has been found to have significant degeneration with both increasing age and, even more so, in those with Alzheimer’s Disease (Wisse et al. 2014). However, previous studies have found structural differentiation between healthy controls and MCI to be much less distinctive than between healthy controls and those with Alzheimer’s disease (Gómez-Sancho, Tohka, and Gómez-Verdejo 2018). Some differences in degeneration profile have been found in the CA1 subfield of the hippocampus (Apostolova et al. 2010). Furthermore, the experimental scans (resting-state fMRI and diffusion MRI) may allow increased differentiation by imaging aspects of the brain that may be affected earlier in Alzheimer’s disease progression (Khazaee, Ebrahimzadeh, and Babajani-Feremi 2017).

So far, we have completed 50% of our target sample of 200 cases and have encountered several challenges. First, many older respondents found the protocol to be long, and a few respondents became impatient and were unable to complete the entire protocol. Therefore, over time we re-ordered the MRI protocol sequence, starting with the core sequences and moving into functional MRI last. Second, although respondents were requested not to move inside the scanner, but in case if the movement was noticed in the middle of a sequence, the repetition of that particular sequence/s made the duration of the protocol much longer for elderly. To address this issue we have reminded the respondents before carrying out each sequence with appropriate instruction about the approximate duration of that sequence. Third, as we collaborated with multiple institutions across the country, different institutions have different equipment hence we tailored our protocol as per each site’s technical requirements.

Fieldwork Organization and Implementation

As our sample was drawn from 14 states to achieve representativeness and to cover diverse cultural and geographic variations, we developed a fieldwork plan to accommodate such diversity in partnership with 11 collaborating regional centers with AIIMS, New Delhi, as the main coordinating center. Because the main LASI fieldwork unfolded in three phases (originally planned as two phases, but due to administrative requirements, phase 2 fieldwork was further staged), we organized the LASI–DAD fieldwork in two phases, covering seven states in each phase. The phase 1 states were Delhi, Haryana, Karnataka, Kerala, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, and Uttar Pradesh, and the phase 2 states were Assam, Jammu and Kashmir, Madhya Pradesh, Maharashtra, Odisha, Telangana, and West Bengal.

Field Team Selection, Training, and Certification.

For each phase of the fieldwork, we started with a two-week training of interviewers, site preparation, and initiation, followed by data collection. The head of RCs recruited interviewers and coordinators based on predetermined criteria set by the central project management team. The eligibility criteria for the coordinator was preferably a Master’s degree in social work or any other related field and the criteria for the interviewers was either a degree in nursing or clinical psychology or social work. All members of the field team were required to possess a good working knowledge of English and computers. Candidates with at least one year’s experience in community work received preference. Each field team consisted of a coordinator and 4–6 interviewers according to the target sample size of the state (which in turn depended on the state’s population). One interviewer was assigned for about 60 participants. The selected team members took part in the centralized training of field staff for the study.

All team members had to undergo a certification process at the end of training based on HCAP certification criteria for the different cognitive tests and on observation of the interviewer’s skills. Only certified and trained staff members were retained for data collection. After completion of the training, the field staff was required to practice interviews during the following weeks using CAPI techniques and to upload data for review by the trainers. They were also responsible for site preparation for final data collection.

Site Preparation.

The central project management team visited each regional center 2–3 weeks after the training, helping the local fieldwork team get ready for fieldwork, supervising the preparedness, and starting formal data collection. The training team addressed concerns and logistical issues faced by the fieldwork team. The duties of the local fieldwork team included scheduling interviews (from the sample drawn from main LASI), bringing respondents and informants to hospitals for interviews, coordinating with the earmarked laboratories to complete the venous blood draw and dispatch the blood samples, conducting interviews at the hospital and/or in the community, providing incentives (food, transport, remuneration), and proper uploading of collected data. Several logistical issues arose for various reasons, including poor internet connection, bad weather, failure to locate respondents, etc., and the central team helped address these logistical issues and kept in close contact with the local team throughout the fieldwork period.

Computer-Assisted Sample and Blood Specimen Management.

We conducted the CAPI using mini laptops. The CAPI enables us to track not only respondents and their informants in a sample management system, but also allows tracking of venous blood samples. As the fieldwork progressed, the collected data were uploaded at least weekly, enabling us to monitor the fieldwork progress and the quality of data collected. The project management team was in constant communication with the local fieldwork teams through social media, emails, or telephone. Daily monitoring of the fieldwork plan, interviews completed, successful uploading of data, and proper collection of venous blood samples for biomarker and genetic studies was done by the core management team. Once blood was collected, it was shipped to the central Delhi Metropolis Laboratory and MedGenome Laboratories in Bengaluru for genetic studies. The shipping time and transport temperatures were monitored, as both have a potential effect on the analysis quality. An automated procedure in the Blood Management System was in place to check transit times to ensure they were not exceeded. If a tube was in transit too long, an automated email would be sent to the fieldwork supervisor, who could follow up with the laboratories and the couriers. The temperature logs were checked weekly to ensure temperatures stayed below the aforementioned shipment temperatures. A robust communication system among all echelons of office bearers helped in troubleshooting whenever required.

Data Monitoring and Quality Control.

Taking advantage of the CAPI system, we closely monitored data quality. Specifically, we examined the distribution of each test and its missingness due to “don’t know” and “refusal” by site, interviewer, age group, and education group. The larger project team, including additional experts in neuropsychology, psychiatry, geriatrics, and epidemiology reviewed the collected data every week during the first two months of fieldwork at each site, and an automated quality control (QC) protocol was developed. This QC protocol was designed to examine fieldwork progress and to identify unusual response patterns (e.g., extreme values), incomplete recording, and interview time (e.g., unusually short or lengthy interview), signalling potential problems in fieldwork implementation. In addition, the consistency of cognitive test scores for a given respondent with his/her performance in the LASI main wave and the informant reports was examined to identify the cases in which consistency was questionable. The monitoring team also closely examined variations across sites and across interviewers to identify any systematic biases from specific sites or interviewers.

Incentives.

To encourage participation, we offered token remuneration (per IRB approval) to the participants in appreciation for their time. Arrangements were made to transport participants to and from the hospital for hospital interviews and for the neuroimaging study. Meals and refreshments were also provided to them after the blood draw. The decision to provide transportation to the hospitals proved to be fruitful. It increased respondent compliance, as traveling alone to hospitals and locating the place of interview in a busy hospital might have been a deterrent in consenting to take part in the study. Finally, we also provided a health report, which was not a part of the original protocol, but was done in response to frequent requests by respondents. This report includes information about physical parameters like height, weight, body-mass index, blood pressure, heart rate readings, and blood reports (complete blood count, lipid profile, serum creatinine, glycosylated haemoglobin, and serum calcium).

Discussion and Conclusion

Data collection for phase I and II of the first wave of the LASI-DAD study was completed in 2019. It has been an enriching learning experience for the team of researchers involved in the study. We look forward to sharing valuable data on dementia and mild cognitive impairment and their correlates with the global research community. In this section, we discuss some of the challenges we encountered and how they were addressed, in order to assist similar future studies.

Logistics.

The logistics of conducting longitudinal research are demanding and require an appropriate and robust infrastructure that can support the actual duration of the study. As the study was conducted at multiple remote sites, much time and planning were invested. Maintaining standardization and consistency of data collection by following the study protocol at the different sites was essential. Management of personnel and equipment and proper coordination among sites were essential in achieving a high standard of data quality. As seen in other longitudinal studies, regular monitoring of outcome measures and focused review of any areas of concern is essential (Newman 2010). These studies are dynamic and necessitate regular updating of procedures and protocols as dictated by events and circumstances (Caruana et al. 2015). Multiple stakeholders were involved, and proper coordination among them was essential. The collaborating centers, AIIMS, New Delhi, and USC, had to coordinate closely with the regional collaborating hospitals, which played a leading role in data collection. Venous blood collection for biomarker assay and the genetic and neuroimaging studies had to be planned and coordinated with the main interviews. Procurement and disbursement of instruments to the different sites for data collection, provision of computers for fieldwork, budgeting and fund allocation for fieldwork, recruitment and training of staff, and translation of the instrument to different regional languages were some of the main logistical issues. The Indian Institute of Population Sciences, Mumbai, the nodal institution for the main LASI, has supported the project by sharing maps to help locate respondents and sharing letters of support from the Government of India and state governments to demonstrate project legitimacy.

Translation.

India is known for its linguistic diversity, with 22 official languages. Each state has its own unique language and script, and frequently the same state has different dialects of the same language depending upon the rural–urban divide. The main LASI-DAD questionnaire was developed in English. A rigorous process of forward and backward translation was followed to translate the LASI-DAD questionnaire into regional languages. The practicality and authenticity of the translated questionnaire had to be checked during the pre-tests so that standardization of the questions asked was maintained. While the training was done with the original questionnaire in English, inputs were taken from the regional teams to harmonize the regional translations to the original instrument in English. Data collected during pre-tests were scrutinized for differences among states to rule out incongruency in questions asked in different languages.

LASI-DAD phase I and II interviews were conducted in 11 languages. Almost 32% of the interviews were conducted in Hindi, which is predominantly spoken in northern and central states of India (Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Haryana and Madhya Pradesh). The next largest group was Malayalam (predominantly spoken in the state of Kerala) accounting for 11% of interviews, followed by Tamil (predominantly spoken in the state of Tamil Nadu) and Bengali (predominantly spoken in the state of West Bengal) accounting for 9% each. The proportion of remaining languages – Odiya (state of Odisha), Kannada (state of Karnataka), Marathi (state of Maharashtra), Assamese (state of Assam), Telugu (state of Telangana), Urdu (state of Jammu & Kashmir) – ranged between 5 to 8%, while English was almost negligible at 0.3%. We explored whether translation to different languages might have affected comparability of various cognition tests across India. While the scores are different across some language groups, the patterns are similar for cognition tests that require higher use of language alone – for example the word recall tests, logical memory tests using story-telling, TICS, CSID and animal naming test, compared to those that require relatively lower reliance on language alone like constructional praxis, digit span, symbol cancellation and Raven’s. It is also important to note that language and state are highly correlated, hence it cannot be concluded that any mean differences in test scores are due to language, or due to state-level differences in other factors.

CAPI.

The field teams took time to familiarize themselves with the data collection and uploading using the CAPI system. The core management team was in constant contact with the field teams, helping them resolve CAPI-related technical issues. Paucity of electrical charging points in rural and remote areas was a disadvantage for the fieldworkers. These field experiences made the teams wiser; they made it a point to charge their laptops before going into the field, and maps were provided to the field teams to fall back on while locating sampling units. The field teams were in continual contact with the core management team, and technical experts were always available to troubleshoot problems whenever the teams faced a roadblock in the field during data collection.

Fieldwork Planning.

Each state’s field team coordinator had to plan the fieldwork diligently. Respondents living nearby were brought to the collaborating hospitals for interviews and venous blood draws. The coordinator was responsible for providing safe transportation for the respondent and informant to the hospital and back, coordinating the blood draw, and supervising and assisting the interviewers. For respondents residing farther away, the coordinator had to make travel arrangements for the entire field team, including accommodation and transportation, with the help of the core training team. Some sampling units required up to 12 hours by car to reach, and because of the distance from the regional collaborating centers, it was more efficient for the team to lodge nearby to the sampling units while carrying out fieldwork to avoid time lost traveling. The regional collaborating centers played an important role in arranging data collection from both nearby and distantly located respondents.

Blood Management System.

Collection of venous blood deserves a special mention as it required tremendous effort and coordination. In hospital samples, the phlebotomist had to be informed regularly about the number of blood draws planned per day by the field team coordinator. While collecting samples from the community, where the team had to travel far distances and stay for a few days to complete interviews, a special day was assigned to collect fasting venous blood. Logistics and planning had to be done beforehand to maintain the proper cold chain during transport of venous blood from faraway locations to the regional branches of the earmarked laboratories, and further to the central processing laboratory. Diverse climatic conditions in different states of India along with weather extremes like rains, floods or extreme heat or cold conditions posed challenges for transportation of venous blood samples. Hence, a system generated alarm mechanism was put in place which would intimate key persons in the training team if there were any breach in protocol in the blood flow system.

Sample Characteristics.

While the sample size of LASI is 72,000, the LASI-DAD donor sample size was 31,516 since it comprised of the 60+ sample interviewed earlier in LASI. Among these 41.8% were categorized as at high-risk of cognitive impairment and 58.2% as at low-risk of cognitive impairment as per their performance on cognitive tests administered during LASI. Among these, 3891 individuals were chosen to be LASI-DAD respondents, with 51.5% consisting of those categorized as at high-risk of cognitive impairment. The average time interval between the main LASI and the LASI-DAD interviews was seven months. Data collection for phase I and II of the first wave of LASI-DAD was completed in 2019 and the data has been made publicly available to the research community. 93 MRI cases have been completed so far of which 41% are high risk of cognitive impairment individuals, and more are ongoing. We briefly discuss below refusals and response rates, internal consistency and informant characteristics, and comparison with HCAP studies from the United States and Mexico.

Refusals and Response Rates.

The field teams had to face refusals to take part in the study, which occurred more in metropolitan and urban areas. The core project management team provided further training to convert refusal to participation, and the blood report was provided as another incentive for the respondents in addition to small cash honoraria. Difficulties were also faced in locating households due to movement of participants to other locations, particularly in slum areas. Attrition due to death of LASI samples was also observed, and the main LASI study plans to conduct an interview with the family member of the deceased respondents during wave 2 data collection.

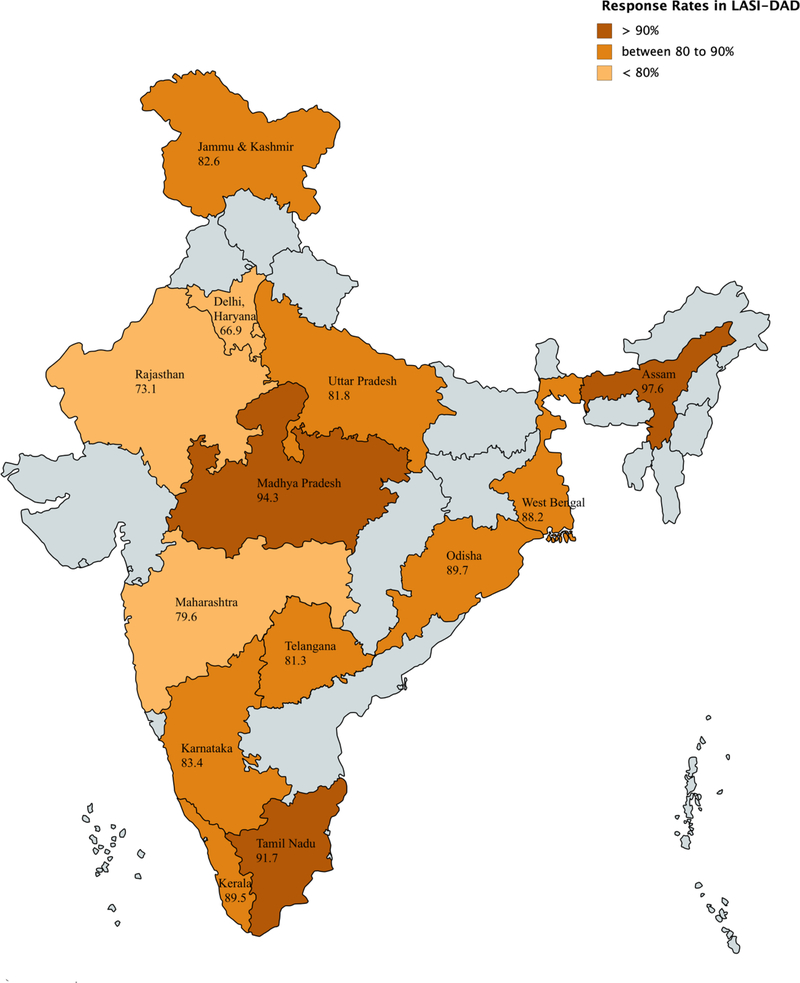

Overall response rate for the LASI-DAD interviews was almost 83% (data collected for 3,224 individuals out of the chosen sample of 3,891). There were no notable differences by age, or risk of cognitive impairment. Response rates were lower among men than women by 5%, lower among higher education groups, and lower in urban areas by 15% compared to rural areas. Looking at geographic variation, 11 out of 14 states had a response rate close to or higher than 80% (see Figure 2 for further details).

Figure 2.

LASI-DAD Response Rates by States of India.

Missing data vary not only across cognition tests, but also test components, as well as are generally higher among women and respondents with no formal education2. For example, among the HMSE components, response to the test on being able to correctly mention current year is missing for 34% of the sample. This is largely driven by the sub-sample with no formal education – response to year naming is missing for 60% of this subsample. This could potentially be due to these individuals solely following various versions of Hindu calendars, some of which differ with respect to when they consider the new year to begin. Serial 7s are missing for 44% of the sample due to innumeracy. For HMSE components like 3-word recall and object naming, rate of missings are as low as 2 to 3%. Since missingness in data is systematic for some components which might result in biased statistics and estimates, and makes the construction of combined cognition scores difficult, harmonized version of the LASI-DAD also provides imputed values of tests scores. The implemented method was inspired by the imputations of cognition variables used in the HRS (Fisher et al., 2017). Specifically, imputation was based on a regression model for each cognition variable as a function of the other cognition variables and a rich set of background variables: health, demographics, and socio-economic variables. Further details of imputation strategy are described in the Harmonized DAD Data Codebook available from the project website (lasi-dad.org).

Internal Consistency.

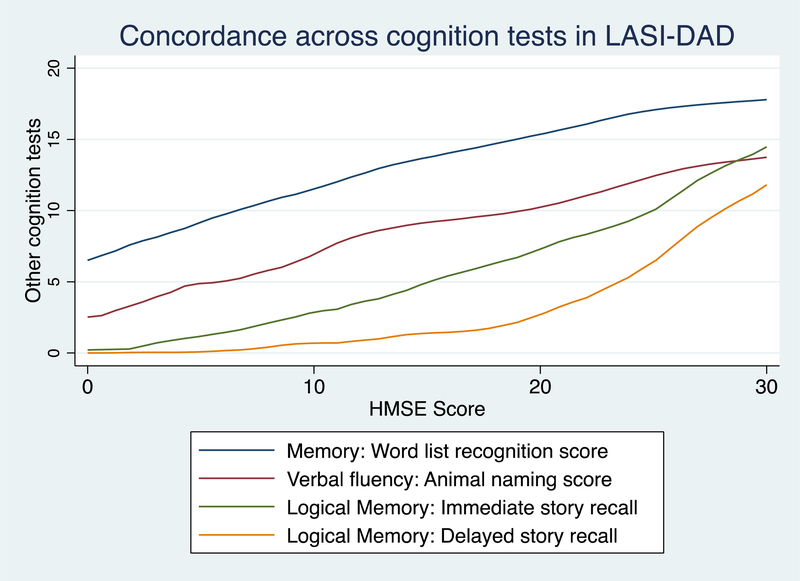

Analyses of the data collected look very good, showing high levels of internal consistency. We checked for this by looking at the correspondence among the cognition test scores, as is evident in Figure 3. There is also a close correspondence between the cognitive test performance and the informant report – scores are lower for respondents for whom the JORM IQCODE score is higher – as reported in Table 3. Hence, the informant report is a valuable component of the LASI-DAD.

Figure 3.

Internal Consistency: Correspondence across Various (Mean) Test Scores

Table 3.

Internal consistency in the LASI-DAD data as per concordance between cognition test scores and Informant report.

| Average cognition test score | JORM Score < 3.1 | JORM Score between 3.1 & 3.8 (N=1464) | JORM Score > 3.8 (N=798) |

|---|---|---|---|

| (N=962) | (N=1464) | (N=798) | |

| HMSE | 25.0 | 23.3 | 19.6 |

| TICS | 2.3 | 2.1 | 1.6 |

| CSID | 3.7 | 3.5 | 3.1 |

| 10-word recall (immediate) | 3.2 | 2.8 | 2.1 |

| 10-word recall (delayed) | 3.9 | 3.2 | 2.1 |

| Word list recognition | 17.0 | 16.2 | 14.5 |

| Retrieval fluency | 12.9 | 11.7 | 9.3 |

| Logical Memory (immediate) | 11.6 | 9.7 | 6.2 |

| Logical Memory (delayed) | 8.0 | 6.0 | 3.0 |

| Constructional praxis (immediate) | 6.5 | 5.6 | 3.9 |

| Constructional praxis (delayed) | 3.4 | 2.7 | 1.6 |

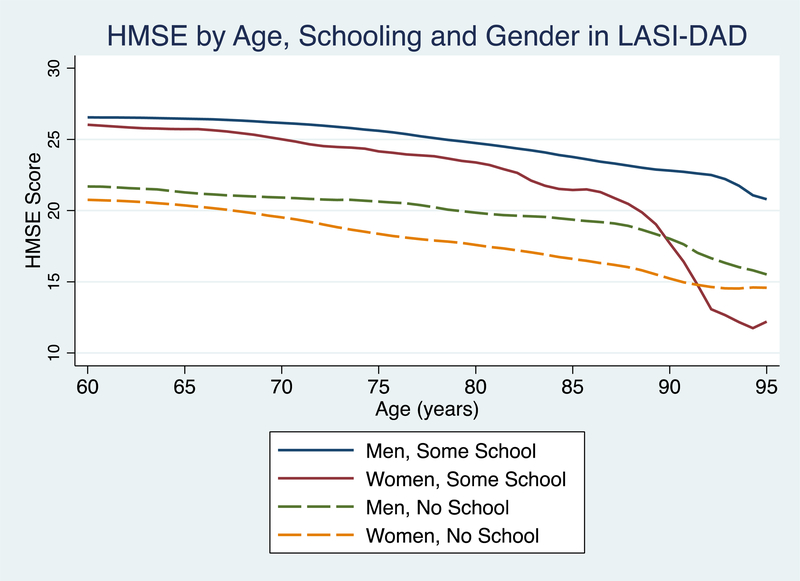

Looking at informant characteristics, 65% of the informants are female and 83% report to be caregivers for the respondent. Further, 31% of informants are spouses, followed by daughters-in-law at 22%, sons at 16% and daughters at 8%. These patterns are expected since the joint family system continues to be prevalent in India. Families are also patriarchal and patrilocal – sons stay with the parents after marriage and their wives (daughters-in-law) are often assigned caregiving responsibilities for dependent parents. Remaining categories are grandchild (6%), parent or parent-in-law (8%), and other relatives (9.5%). There are also expected patterns with respect to known correlates of cognition such as age and education, as demonstrated by the HMSE score in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Cognition by Age, Schooling and Gender

Comparison with sister HCAP studies.

LASI-DAD is one of several population-based cognitive impairment and dementia studies using HCAP; this family of studies includes the Health and Retirement Study – HCAP (HRS-HCAP), the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing – HCAP (ELSA-HCAP), and the Mexican Health and Aging Study’s Cognitive Aging Ancillary Study (Mex-Cog), along with the China Health and Retirement Survey (CHARLS), Health and Aging in Africa: A Longitudinal Study of an INDEPTH Community in South Africa (HAALSI)3. Since certain components of the LASI-DAD instrument were adapted to account for high levels of illiteracy and/or innumeracy among the older population in India, we compare the LASI-DAD with HRS-HCAP and MexCog, which were publicly available at the time of writing this paper. The comparisons are presented in Table 4. It is important to note two major demographic differences across the three study samples with respect to age and education levels, presented in Panel A. While the minimum age in LASI-DAD is 60, it is 65 in HRS-HCAP and 55 in MHAS-MexCog. Hence, when comparing cognition test scores in Panel B of Table 4, we restrict the sample to those aged between 65 to 85 years of age – this helps with not only the varying minimum age across the three studies, but also with the very different life expectancies by dropping those who are very old. Educational attainment is highest in the US, followed by Mexico and lowest in the Indian sample. Almost 50% of the LASI-DAD sample did not attend any school, while this proportion is 17% for the sample in Mexico and negligible in the HRS-HCAP sample. Since education is one of the most significant correlates of cognition, any comparisons across countries need to keep these differences in educational attainment in mind, as well as the nature of selection – the 80% sample of HRS-HCAP who have completed high school education and above are relatively more representative of the US older population than the 8.2% in the LASI-DAD which are a highly selective sub-sample among the Indian older population.

Table 4.

Cross-country comparisons of LASI-DAD with dementia studies from USA (HRS-HCAP) & Mexico (MHAS-MexCog)

| HRS-HCAP (N=3496) | MHAS-Mexcog (N=2042) | LASI-DAD (N=3224) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A: Demographic variables | |||

| Female (%) | 59.9 | 58.9 | 53.9 |

| Age# | 76.0 | 68.1 | 69.3 |

| Proportion aged < 69 | 25.3 | 59.7 | 58.6 |

| Proportion aged >=70 | 74.7 | 40.3 | 41.4 |

| Education: | |||

| Never attended any school | 0.6 | 17.3 | 47.2 |

| Attended or completed primary school | 5.7 | 55.6 | 26.4 |

| Middle or less than high school | 14.0 | 17.0 | 18.2 |

| High school completed and above | 79.6 | 10.2 | 8.2 |

| Panel B: Cognition (subsample: age 65 to 85) | |||

| Examples of non-modified tests | |||

| Animal naming | 16.4 | 14.4 | 11.3 |

| Word list recall (immediate) | 7.2 | 5.1 | 4.9 |

| Word list recall (delayed) | 5.3 | 2.7 | 2.9 |

| Word list recognition | 18.7 | 16.1 | 15.8 |

| CSID | 3.7 | 3.3 | 3.4 |

| Constructional Praxis (immediate) | 8.2 | 7.8 | 5.4 |

| Constructional Praxis (delayed) | 6.0 | 4.8 | 2.5 |

| Examples of modified tests | |||

| Symbol cancellation: correct## | n.a. | 23.5 | 7.8 |

| Symbol cancellation: incorrect | n.a. | 1.0 | 2.1 |

Notes:

Minimum age is 65 in HRS-HCAP, 55 in MHAS-MexCog and 60 in LASI-DAD.

HRS-HCAP uses the Letter cancellation test for which the maximum value is 37, while the maximum value for symbol cancellation tests in LASI-DAD and MexCog is 60.

Among the average cognition test scores, we first compare those tests which were not modified, like the 10-word list recall and recognition, CSID, and constructional praxis. Scores are highest for the HRS-HCAP respondents, followed by the MexCog and then the LASI-DAD, except for delayed word recall and CSID where LASI-DAD scores are only slightly higher than MexCog. While the HRS-HCAP used the Letter Cancellation test, MexCog and LASI-DAD used the symbol cancellation test. The raw scores across letter and symbol cancellation tests are not comparable since the range of values is different. MexCog respondents do much better on the symbol cancellation test than their LASI-DAD counterparts. These patterns are not unexpected given the levels of education across the three subsamples. Researchers keen on comparisons of the letter cancellation test with symbol cancellation (or any other tests for which the numeric range of raw values are different across the HCAP studies) could attempt constructing simple or age-and-gender adjusted z-scores or conduct item-response theory (IRT) analysis to use underlying latent construct.

These findings suggest that data collected using the HCAP protocol enables comparative analysis of cognitive function as many common tests were employed, and for the countries where illiteracy is high among older adults, the common tests that do not require literacy (e.g., symbol cancellation test) was administered. The administration of similar HCAP projects in multiple countries around the world will provide an opportunity to investigate cross-country variations in the risk and protective factors of late-life cognition and dementia.

Acknowledgement:

We thank Drs. David Weir and Mary Ganguli for their advice and support for the project. This project is funded by the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG051125, RF1 AG055273). We received the ethical approval from the Indian Council of Medical Research and all participating institutions.

Appendix

Table A1.

Percentage of missing data by HMSE components among LASI-DAD respondents.

| Overall (N=3224) | Male (N=1487) | Female (N=1737) | No School (N=1522) | Some School (N=1702) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hindi Mental State Examination Components | |||||

| Orientation to time: month | 12.1 | 9.1 | 14.7 | 20.4 | 4.8 |

| Orientation to time: year | 34.3 | 22.6 | 44.4 | 56.3 | 14.7 |

| Orientation to time: week day | 8.4 | 6.9 | 9.8 | 13.7 | 3.8 |

| Orientation to time: season | 9.0 | 7.5 | 10.3 | 13.1 | 5.3 |

| Orientation to time: date | 21.8 | 15.4 | 27.3 | 34.8 | 10.2 |

| Orientation to place: state | 22.3 | 11.0 | 32.0 | 36.5 | 9.5 |

| Orientation to place: city | 4.4 | 2.9 | 5.6 | 6.6 | 2.4 |

| Orientation to place: floor | 4.9 | 3.3 | 6.2 | 7.5 | 2.5 |

| Orientation to place: name | 14.0 | 6.3 | 20.6 | 22.9 | 6.0 |

| Orientation to place: address | 9.3 | 4.7 | 13.3 | 15.0 | 4.2 |

| 3-word recall: immediate | 2.0 | 1.8 | 2.2 | 2.8 | 1.4 |

| 3-word recall: delayed | 5.3 | 4.3 | 6.2 | 8.0 | 2.9 |

| Backward Day Naming | 10.7 | 8.1 | 12.9 | 19.1 | 3.1 |

| Object Naming 1 | 2.6 | 2.6 | 2.5 | 3.6 | 1.6 |

| Object Naming 2 | 2.5 | 2.4 | 2.5 | 3.5 | 1.5 |

| Whether able to repeat a phrase | 4.7 | 4.0 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 2.9 |

| Follow Command | 2.9 | 3.2 | 2.6 | 3.6 | 2.3 |

| Paper folding | 2.9 | 2.7 | 3.1 | 4.1 | 1.8 |

| Sentence writing/speaking | 4.2 | 4.6 | 3.8 | 5.4 | 3.1 |

| Pentagon drawing | 8.1 | 7.8 | 8.3 | 11.6 | 4.9 |

Notes: Individual level data from Phase I and II of LASI-DAD.

Table A2.

Percentage of missing data by cognition tests among LASI-DAD respondents.

| Overall (N=3224) | Male (N=1487) | Female (N=1737) | No School (N=1522) | Some School (N=1702) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CERAD Word list | |||||

| 10-word list: Trial 1 | 2.8 | 2.3 | 3.2 | 4.5 | 1.2 |

| 10-word list: Trial 2 | 3.0 | 2.5 | 3.4 | 5.0 | 1.2 |

| 10-word list: Trial 3 | 3.5 | 2.8 | 4.2 | 5.9 | 1.4 |

| 10-word list: Delayed | 3.5 | 2.9 | 4.1 | 5.5 | 1.8 |

| Word list recognition: previous | 6.1 | 5.2 | 6.8 | 9.9 | 2.7 |

| Word list recognition: new | 6.0 | 5.3 | 6.6 | 9.8 | 2.6 |

| Logical memory | |||||

| Brave man story (immediate) | 6.4 | 4.9 | 7.7 | 10.2 | 3.0 |

| Brave man story (delayed) | 8.1 | 7.1 | 8.9 | 12.9 | 3.8 |

| Robbery story (immediate) | 8.6 | 6.4 | 10.4 | 13.7 | 4.0 |

| Robbery story (delayed) | 13.6 | 11.2 | 15.6 | 20.7 | 7.2 |

| Story recognition | 14.9 | 12.8 | 16.8 | 22.6 | 8.0 |

| TICS: scissors | 2.6 | 2.3 | 2.9 | 4.3 | 1.1 |

| TICS: coconut | 9.0 | 7.3 | 10.4 | 12.3 | 6.0 |

| TICS: prime minister | 23.3 | 11.7 | 33.2 | 37.9 | 10.2 |

| Digit Span Forward | 6.0 | 3.1 | 8.5 | 9.9 | 2.6 |

| Digit Span Backward | 7.5 | 4.2 | 10.2 | 12.4 | 3.1 |

| Symbol Cancellation | 2.9 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 4.0 | 1.9 |

| Retrieval Fluency | 3.1 | 3.1 | 3.2 | 4.4 | 2.0 |

| Constructional Praxis (immediate) | |||||

| Circle | 8.2 | 7.6 | 8.6 | 12.1 | 4.6 |

| Rectangle | 9.2 | 8.3 | 10.0 | 13.9 | 5.0 |

| Cube | 10.6 | 8.6 | 12.3 | 16.6 | 5.3 |

| Diamond | 8.7 | 7.9 | 9.5 | 13.3 | 4.7 |

| Constructional Praxis (delayed) | |||||

| Circle | 15.0 | 12.8 | 16.8 | 21.5 | 9.1 |

| Rectangle | 16.2 | 13.9 | 18.2 | 23.2 | 10.0 |

| Cube | 19.2 | 17.0 | 21.1 | 27.3 | 12.0 |

| Diamond | 16.9 | 15.0 | 18.5 | 24.1 | 10.5 |

| Clock drawing | 10.4 | 8.7 | 11.7 | 15.0 | 6.2 |

| CSID: elbow | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.0 | 4.3 | 2.2 |

| CSID: hammer | 3.8 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 5.6 | 2.3 |

| CSID: store | 4.2 | 3.4 | 4.9 | 5.8 | 2.8 |

| CSID: point | 4.2 | 4.4 | 4.0 | 6.0 | 2.6 |

| Raven’s | 10.6 | 9.3 | 11.7 | 16.8 | 5.0 |

Footnotes

Disclosure statement. All authors disclose no conflict of interest.

Other countries also include Chile. Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE), The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA), and Northern Ireland Cohort for the Longitudinal Study of Ageing (NICOLA) have also been recently funded to administer HCAP in multiple countries in Europe.

References

- Agrigoroaei S, and Lachman ME. 2011. Cognitive Functioning in Midlife and Old Age: Combined Effects of Psychosocial and Behavioral Factors. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B 66B(suppl_1): i130–40. 10.1093/geronb/gbr017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th Ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Thoracic Society. 2002. ATS Statement Guidelines for the Six-Minute Walk Test. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 166(1): 111–17. 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apostolova LG, L Mosconi P M Thompson, A E Green, K S Hwang, A Ramirez, R Mistur, W H Tsui, M J de Leon. Subregional hippocampal atrophy predicts Alzheimer’s dementia in the cognitively normal. Neurobiology of Aging 31, 1077–1088 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Epstein N, Brown G, and Steer RA. 1988. An Inventory for Measuring Clinical Anxiety: Psychometric Properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 56(6): 893–97. 10.1037/0022-006X.56.6.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blessed G, Tomlinson BE, and Roth M. 1968. The Association between Quantitative Measures of Dementia and of Senile Change in the Cerebral Grey Matter of Elderly Subjects. The British Journal of Psychiatry 114(512): 797–811. 10.1192/bjp.114.512.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt J, Spencer M, and Folstein M. 1988. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, & Behavioral Neurology 1(2): 111–17. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana EJ, Roman M, Hernández-Sánchez J, and Solli P. 2015. Longitudinal Studies. Journal of Thoracic Disease 7(11): E537, E540–E540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CERAD. 1987. Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease: Clinical Assessment Packet for Clinical/Neuropsychological Assessment for Alzheimer’s Disease. https://sites.duke.edu/centerforaging/cerad/.

- Dale AM, Fischl B, and Sereno MI. 1999. Cortical Surface-Based Analysis: I. Segmentation and Surface Reconstruction. NeuroImage 9(2): 179–94. 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Renzi E, and Vignolo LA. 1962. The Token Test: A Sensitive Test to Detect Receptive Disturbances in Aphasics. Brain 85(4): 665–78. 10.1093/brain/85.4.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher GG, Hassan H, Faul JD, Rodgers WL, & Weir DR. Health and Retirement Study: Imputation of Cognitive Functioning Measures: 1992 – 2014 (Final Release Version): Data Description . Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan, Survey Research Center, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein MF, Folstein SE, and McHugh PR. 1975. “Mini-Mental State”: A Practical Method for Grading the Cognitive State of Patients for the Clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research 12(3): 189–98. 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, Ratcliff G, Chandra V, Sharma S, Gilby J, Pandav R, Belle S, et al. 1995. A Hindi Version of the MMSE: The Development of a Cognitive Screening Instrument for a Largely Illiterate Rural Elderly Population in India. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 10(5): 367–77. 10.1002/gps.930100505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomez P, Ratcliff R, and Perea M. 2007. A Model of the Go/No-Go Task. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 136(3): 389–413. 10.1037/0096-3445.136.3.389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Sancho M, Tohka J, and Gómez-Verdejo V. 2018. Comparison of Feature Representations in MRI-Based MCI-to-AD Conversion Prediction. Magnetic Resonance Imaging 50(July): 84–95. 10.1016/j.mri.2018.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall KS, Hendrie HC, and Brittain HM. 1993. The Development of a Dementia Screening Interview in 2 Distinct Languages. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research 3(1): 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Fox NC, Thompson P, Alexander G, Harvey D, Borowski B, et al. 2008. The Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): MRI Methods. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 27(4): 685–91. 10.1002/jmri.21049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm AF, and Jacomb PA. 1989. The Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): Socio-Demographic Correlates, Reliability, Validity and Some Norms. Psychological Medicine 19(4): 1015–22. 10.1017/S0033291700005742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khazaee A, Ebrahimzadeh A, and Babajani-Feremi A. 2017. Classification of Patients with MCI and AD from Healthy Controls Using Directed Graph Measures of Resting-State FMRI. Behavioural Brain Research 322(Pt B): 339–50. 10.1016/j.bbr.2016.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP, and Brody EM. 1969. Assessment of Older People: Self-Maintaining and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living. The Gerontologist 9(3_Part_1): 179–86. 10.1093/geront/9.3_Part_1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Sommerlad A, Orgeta V, Costafreda SG, Huntley J, Ames D, Ballard C, et al. 2017. Dementia Prevention, Intervention, and Care. The Lancet 390(10113): 2673–2734. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31363-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowery N, Ragland D, Gur RC, Gur RE, and Moberg PJ. 2004. Normative Data for the Symbol Cancellation Test in Young Healthy Adults. Applied Neuropsychology 11(4): 216–19. 10.1207/s15324826an1104_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney FI, and Barthel DW. 1965. Functional Evaluation: The Barthel Index: A Simple Index of Independence Useful in Scoring Improvement in the Rehabilitation of the Chronically Ill. Maryland State Medical Journal 14: 61–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masnoon N, Shakib S, Kalisch-Ellett L, and Caughey GE. 2017. What Is Polypharmacy? A Systematic Review of Definitions. BMC Geriatrics 17(1): 230 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattis S 1988. Dementia Rating Scale. Professional Manual. Florida: Psychological Assessment Resources. [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC. The clinical dementia rating (CDR): current version and scoring rules. Neurology. 1993. November;43(11):2412–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, Hughes JP, van Belle G, Fillenbaum G, Mellits ED, and Clark C. 1989. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and Neuropsychological Assessment of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology 39(9): 1159–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bédirian V, Charbonneau S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, and Chertkow H. 2005. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A Brief Screening Tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 53(4): 695–99. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman AB 2010. An Overview of the Design, Implementation, and Analyses of Longitudinal Studies on Aging. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 58(s2): S287–91. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patenaude B, Smith SM, Kennedy DN, and Jenkinson M. 2011. A Bayesian Model of Shape and Appearance for Subcortical Brain Segmentation. NeuroImage 56(3): 907–22. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podsiadlo D, and Richardson S. 1991. The Timed “Up & Go”: A Test of Basic Functional Mobility for Frail Elderly Persons. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 39(2): 142–48. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01616.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prince M, Ferri CP, Acosta D, Albanese E, Arizaga R, Dewey M, Gavrilova SI, et al. 2007. The Protocols for the 10/66 Dementia Research Group Population-Based Research Programme. BMC Public Health 7(1): 165 10.1186/1471-2458-7-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS 1977. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement 1(3): 385–401. 10.1177/014662167700100306. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Raven J 2000. The Raven’s Progressive Matrices: Change and Stability over Culture and Time. Cognitive Psychology 41(1): 1–48. 10.1006/cogp.1999.0735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosen WG, Mohs RC, and Davis KL. 1984. A New Rating Scale for Alzheimer’s Disease. The American Journal of Psychiatry 141(11): 1356–64. 10.1176/ajp.141.11.1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruesch J 1944. Intellectual Impairment in Head Injuries. American Journal of Psychiatry 100(4): 480–96. 10.1176/ajp.100.4.480. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simens HearCheck Screener. 2007. HearCheck Screener: User Guide. https://www.connevans.info/image/connevans/38shearcheck.pdf

- Tripathi R, Kumar JK, Bharath S, Marimuthu P, and Varghese M. 2013. Clinical Validity of NIMHANS Neuropsychological Battery for Elderly: A Preliminary Report. Indian Journal of Psychiatry 55(3): 279–82. 10.4103/0019-5545.117149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vellas B, Guigoz Y, J Garry P, Nourhashemi F, Bennahum D, Lauque S, and Albarede JL. 1999. The Mini Nutritional Assessment (MNA) and Its Use in Grading the Nutritional State of Elderly Patients. Nutrition 15(2): 116–22. 10.1016/S0899-9007(98)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. 1997. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd Ed. San Antonio, Texas: The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. 2009. Wechsler Memory Scales—Fourth Edition (WMS-IV): Technical and Interpretive Manual. San Antonio, Texas: Pearson Clinical Assessment; https://www.pearsonassessments.com/store/usassessments/en/Store/Professional-Assessments/Cognition-%26-Neuro/Wechsler-Memory-Scale-%7C-Fourth-Edition/p/100000281.html. [Google Scholar]

- Weir DR, Langa KM, and Ryan LH. 2016. Harmonized Cognitive Assessment Protocol (HCAP): Study Protocol Summary. Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan. http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/index.php?p=shoavail&iyear=ZU. [Google Scholar]

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2014. WHO Methods for Life Expectancy and Healthy Life Expectancy. Geneva: Department of Health Statistics and Information Systems; https://www.who.int/healthinfo/statistics/LT_method_1990_2012.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Wisse LEM, Biessels GJ, Heringa SM, Kuijf HJ, Koek DL, Luijten P/R, and Geerlings MI. 2014. Hippocampal Subfield Volumes at 7T in Early Alzheimer’s Disease and Normal Aging. Neurobiology of Aging 35(9): 2039–45. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2014.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, McGrew KS, and Mather N. 2001. The Woodcock–Johnson III (WJIII), Tests of Achievement. Itasca, IL: Riverside Publishing Co. [Google Scholar]

- Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, Chappell M, Makni S, Behrens T, Beckmann C, Jenkinson M, and Smith SM. 2009. Bayesian Analysis of Neuroimaging Data in FSL. NeuroImage, Mathematics in Brain Imaging, 45(1, Supplement 1): S173–86. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brady M, and Smith S. 2001. Segmentation of Brain MR Images through a Hidden Markov Random Field Model and the Expectation-Maximization Algorithm. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 20(1): 45–57. 10.1109/42.906424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]