Abstract

Nitroxyl contrast agents (nitroxyl radicals, also known as nitroxide) are paramagnetic species, which can react with reactive oxygen species (ROS) to lose paramagnetism to be diamagnetic species. The paramagnetic nitroxyl radical forms can be detected by using electron paramagnetic resonance imaging (EPRI), Overhauser MRI (OMRI), or MRI. The time course of in vivo image intensity induced by paramagnetic redox-sensitive contrast agent can give tissue redox information, which is the so-called redox imaging technique. The redox imaging technique employing a blood–brain barrier permeable nitroxyl contrast agent can be applied to analyze the pathophysiological functions in the brain. A brief theory of redox imaging techniques is described, and applications of redox imaging techniques to brain are introduced.

Keywords: Redox imaging, nitroxyl contrast agents, Overhauser MRI, electron paramagnetic resonance imaging, reactive oxygen species, hypoxia, hyperoxia

1. Introduction

1.1. Redox-Sensitive Contrast Agent

Nitroxyl contrast agents (nitroxyl radicals, also known as nitroxide) are paramagnetic species, which have one unpaired electron. Structures of several commonly used nitroxyl radicals are shown in Fig. 20.1. Nitroxides belong to two main structural groups, i.e. five-member ring (pyrrolidine derivatives or so-called PROXYL derivatives) and six-member ring (piperidine derivatives or so-called TEMPO derivatives). Substitutional groups on the pyrrolidine ring of the PROXYL derivatives or the piperidine ring of the TEMPO derivatives determine the in vivo distribution of these agents as well as their sub-cellular distribution. Nitroxyl contrast agents with appropriate substitutional groups on the ring can be directed to intracellular locations, such as the mitochondria, or restricted to extracellular spaces or even penetrate the blood–brain barrier (BBB) and localize intracellularly. The membrane permeability of nitroxyl contrast agents can be relatively easily modified by chemical substituents on pyrrolidine or piperidine rings of the molecule. Various nitroxyl contrast agents which have distinct membrane permeabilities have been reported. For example, the carboxy-PROXYL can not go through the BBB; however, methoxy-carbonyl-PROXYL (also known as MC-PROXYL or CxP-M), which is synthesized by esterification of carboxy-PROXYL, can readily go through the BBB (1, 2).

Fig. 20.1.

Structures and common names of commercialized nitroxyl radicals. a PROXYL derivatives and b TEMPO derivatives.

The nitroxyl contrast agents are stable free radical species at room temperature in the solid form or even in solutions at physiological pH. However, the nitroxyl radical can be chemically and/or enzymatically reduced to the corresponding hydroxylamine form (Fig. 20.2). The nitroxyl radicals can also be oxidized to oxoammonium cation by reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide (·O2−) and hydroxyl radical (·OH). The oxoammonium cation can be reduced by superoxide by a one-electron reduction back to the nitroxyl radical form or by two electrons to the corresponding hydroxylamine form by reduced glutathione (GSH), reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), and/or reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH) (3, 4). The hydroxylamines can be again re-oxidized to the corresponding nitroxyl radicals under oxidative conditions (5). When a nitroxyl radical is administrated to an experimental animal, the nitroxyl radical is mainly metabolized to the corresponding hydroxylamine form (6). This intrinsic in vivo one-electron reduction of nitroxyl radical can be modified (amplified or retarded) by abnormal tissue redox conditions, such as hypoxia, hyperoxia, and/or several oxidative stress conditions accompanying excess ROS generation. In addition to the redox sensitivity of nitroxyl radicals, BBB permeability with suitable substituents makes them suitable for imaging redox reactions in the brain.

Fig. 20.2.

Reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as superoxide (·O2−) and hydroxyl radical (·OH), undergo one electron reduction of nitroxyl radicals in the presence of hydrogen donors (H-donors), such as reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH), and/or reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADPH). The nitroxyl radicals were once oxidized to an oxoammonium cation by ROS and then reduced to hydroxylamine by receiving a hydrogen atom from H-donors. Reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxoammonium cations may make another complex irreversibly. Therefore, the generation of total ROS can be estimated by a reduction of the nitroxyl radical under coexisting GSH.

1.2. Redox Properties of Nitroxyl Contrast Agent

The reactivity of nitroxyl radicals with ROS is, in other words, that nitroxyl radicals can have antioxidant properties. In fact, several anti-oxidative properties of nitroxyl radicals have been reported (7–11). Leading such studies, the radio-protective activity of TEMPOL also has been studied prosperously (12–16). The radio-protective mechanism of TEMPOL has been considered that is based on its anti-oxidative property, i.e., the reaction of TEMPOL with ROS generated during irradiation of ionizing radiation, such as X-ray and/or γ-ray. In addition, the superoxide dismutase (SOD)-like activity of TEMPOL and its reaction mechanism has been reported (17–19). The currently known reaction mechanisms of nitroxyl radicals and ROS are summarized in Fig. 20.2. As described above, the process of one-electron reduction of nitroxyl radicals to corresponding hydroxylamines goes along with two steps, at first one-electron oxidation, then two-electron reduction. A recent study showed that the reaction of oxoammonium cation and GSH mainly gives a stable complex rather than hydroxyl radicals, although the structure of the complex has not been identified yet (20). However, the main in vivo reaction of nitroxyl radicals is the one-electron reduction to the hydroxylamme (6). Hydroxylamme can be re-oxidized to nitroxyl radical by some oxidants, such as ·OH and/or Fe3+, in vivo. This redox cycle reactions support SOD mimetic catalytic activity, which may underlie its radio-protective effect of TEMPOL.

The hydroxylamine form of TEMPOL, i.e., TEMPOL-H, does not have radio-protective activity for cell (12, 21). However, TEMPOL-H has a radio-protective effect, when TEMPOL-H was administered to a mouse (22). This is because of in vivo re-oxidation of hydroxylamine to the radio-protective nitroxyl radical. The re-oxidation of hydroxylamine to the nitroxyl radical, which is an oxygen-dependent reaction, cannot occur in a hypoxic tumor tissue. Therefore no radioprotective effects of nitroxyl radicals (23, 24) in hypoxic tumors can be expected because of their facile reduction to hydroxylamines. In contrast, slight nitroxyl radical can be continuously available in normoxic normal tissues after dynamic equilibrium between reduction of nitroxyl radical and oxidation of hydroxylamme. Recently, a significantly fast decay of TEMPOL in tumor tissue compared with other normal tissues was reported using an MR-based redox imaging technique (24). It is suggested that nitroxyl radicals can be proposed as a normal tissue-selective radio-protector.

The redox properties of nitroxyl radicals can give us double benefits which are (i) as redox-sensitive contrast agents and (ii) as a normal tissue-selective radio-protector. Both benefits are useful for a first diagnosis of a tumor and radiation therapy planning. These will give a radio-protective treatment for normal tissues in subsequent radiotherapy. Therefore, the magnetic resonance-based redox imaging techniques using nitroxyl contrast agents can have wide possibility.

1.3. Applying Nitroxyl Contrast Agent to Brain Redox Imaging

Redox imaging techniques using electron paramagnetic resonance imaging (EPRI), Overhauser MRI (OMRI), or MRI (25, 26) can visualize and estimate the redox status in living experimental animals. The basis of redox imaging is to obtain a time course of image intensity, which is induced by paramagnetic redox-sensitive contrast agent.

One suitable approach of redox imaging techniques is a brain image (27). The relation between ROS and several brain disorders, such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s disease, is well established (28–30). Likewise, the relation between memory loss and radiation-induced oxidative injuries in brain/neuronal system has also been reported (31–33). Therefore, the redox imaging techniques employing a BBB permeable nitroxyl contrast agent can be another approach to analyze the pathophysiological function in the brain. A brief theory of redox imaging techniques is described, and applications of redox imaging techniques to the brain are introduced.

2. Redox Imaging in EPRI

Paramagnetic nitroxyl radicals can be directly detected by EPR, while the hydroxylamines which are the reduction products of nitroxyl radicals are diamagnetic and therefore EPR silent species. Therefore, detecting a decrease in EPR signal intensity from nitroxyl radicals due to their reduction in biological/chemical samples can be used to monitor redox reactions in vivo. Nitroxyl radicals have been utilized as in vivo molecular probes to estimate redox status in the tissue of experimental animals using in vivo EPR (34, 35). Using low frequency (300–1,200 MHz) EPR spectrometers (36–39) or X-band EPR spectrometers with special sampling techniques for in vivo measurements (40–43) the signal decay and/or the spectral change of nitroxyl spin probe in live animals can be monitored. Combining with EPR imaging techniques using field gradients, the distribution and time course of nitroxyl spin probes in tissues can be visualized (44–47).

Information related to tissue redox status using nitroxyl agents can be visualized by attaching some additional dimensions to an EPRI, such as time axis and/or spectral axis, to a simple image of spatial distribution of the probe molecule (Fig. 20.3). The time axis can be easily achieved by sequential measurement of several images of the spatial distribution of the spin probe. For example, when the image intensities decrease/increase in a time-dependent manner, a mapping of pixel-wise decay/increment rates of image intensities can be observed and the slopes of the image intensity change can be used to generate the “redox map” of the region of interest in an in vivo experiment

Fig. 20.3.

A schematic drawing of the concept of dynamic imaging. The additional time dimension to the spatial mapping of the paramagnetic contrast agent, functional information, such as pharmacokinetics of the contrast agent, can be tagged on to the EPR image. The time axis is by sequential measurement of several EPR images. Consequently, pixel-wise decay rates of EPR image intensity can be obtained.

Most in vivo EPR spectrometers operate in a continuous-wave (CW) modality, where the sample is irradiated continuously at low RF powers and the magnetic field is slowly swept to obtain an EPR spectrum. The temporal resolution of EPR spectroscopy and imaging is limited by the time of a relatively slow magnetic field scan. Recent developments in hardware and new data acquisition techniques achieved EPRI data acquisition capabilities in the range of seconds (48–50). Such a rapid data acquisition will improve the temporal resolution of EPRI in in vivo biological applications. However, the larger EPR linewidths of nitroxyl molecules and the available magnetic field gradients for imaging make the spatial resolution limited. In addition, no anatomical information is available by EPRI. To provide anatomic co-registration to EPR images of nitroxyl distribution in vivo, fusion techniques of EPRI and MRI have been developed by several groups (51–53).

3. Redox Imaging inOMRI

OMRI, which is also known as proton electron double resonance imaging (PEDRI), is a double-resonance technique involving both EPR and NMR (54–56). At a given magnetic field, by virtue of their stronger magnetic moments, the electrons’ spin levels are polarized to a greater extent than the corresponding spin levels of nuclei. When an aqueous solution containing a paramagnetic agent, such as a nitroxyl radical, is placed in a magnetic field within a resonator assembly which is tuned to the resonant frequencies of both the electron and the nucleus, a significant enhancement of the NMR signal results via the Overhauser effect (57) when the NMR signal of 1H of H2O is collected after a period of irradiation at the EPR frequency. Comparing the images obtained with the EPR-irradiation (OMRI signal) and without irradiation (native MRI signal), the paramagnetic contrast agents used can be quantified based on intensity enhancement patterns.

The imaging of nitroxyl contrast agents using OMRI was started by Lurie and colleagues in the late 1980s (54, 55). OMRI is a double resonance imaging technique. It relies on an EPR irradiation pulse followed by an MRI imaging sequence. In this technique, when a paramagnetic species, such as nitroxyls, are present in tissue, irradiating by an EPR pulse at the resonance frequency of the nitroxyl enhances the signal intensity of the surrounding water protons. This makes the image resolution dependent on MRI which is intrinsically a higher resolution technique compared to EPR imaging allowing the imaging of free radicals with ~ millimeter resolution. In addition, OMRI techniques can obtain not only distribution but also EPR spectral information of nitroxyl contrast agents (58). Nitroxyl radicals give a doublet or triplet EPR spectrum by hyper-fine-splitting due to 15N or 14N nuclear spin. Each of these can be separately obtained in the form of OMRI signal by using a different frequency for EPR excitation of either the 14N or the 15N nuclei. Utsumi et al. (58) proposed a novel imaging technique to separate the reduction and oxidation reactions in an identical sample simultaneously using a nitroxyl contrast agent and its hydroxylamine form labeled by different isotopes (i.e., 14N and 15N). They also showed that simultaneous reactions occurred separately inside and outside of liposomes using membrane permeable and impermeable nitroxyls. OMRI is an EPR-dependent spectroscopic imaging technique that displays a high temporal and spatial resolution. It hence affords the rapid imaging of in vivo metabolism of multiple nitroxyl radical probes simultaneously.

4. Trial of EPR-Based Brain Redox Imaging

Using a suitable BBB-permeable nitroxyl contrast agent, the time course of nitroxyl reduction rates in the brain can be visualized. CxP-M (also known as MC-PROXYL: 3-methoxy-carbonyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-pyrrolidine-l-oxyl) (2, 59, 60) and CxP-AM (acetoxymethyl-2,2,5,5-tetramethyl-pyrrolidine-l-oxyl-3-carboxylate) were designed as BBB-permeable spin probe for EPR imaging (2). CxP-AM can be metabolized to BBB-impermeable CxP by esterases in the brain and can also be retained in the brain (2). CxP-AM has been commercialized and is currently available from LABOTEC Co. (Tokyo, Japan).

Anzai et al. (59) reported the distribution of CxP-M in the rat brain using autoradiography with 14C-labeled CxP-M and 3D EPRI. Figure. 20.4a shows a scheme of chemical synthesizing 14C-labeled CxP-M. Figure 20.4b shows autoradiograms of coronal sections of rat head obtained after administration with 14C-CxP-M or 14C-carbamoyl-PROXYL. They suggested that CxP-M is a suitable paramagnetic probe for the study of free radical reactions in the brain using in vivo EPR imaging. Lee et al. (60) reported a faster nitroxyl decay in the brain of spontaneously hypertensive rats compared with Wistar rat using the in vivo EPRI technique with CxP-M. Miyake et al. (61) reported the development of other BBB-permeable nitroxyl radical probes designed for the purpose of oxygen mapping in the brain. Molecular oxygen with two unpaired electrons is paramagnetic and by collisional interaction with the paramagnetic nitroxyls, broadens their EPR spectra in a concentration-dependent manner via a T2 contrast process typical in MRI. The oxygen-dependent spectral broadening can be monitored by EPR imaging allowing the determination of tissue oxygen.

Fig. 20.4.

Autoradiograms of axial sections of rat head obtained after 3 min i.v. or 15 min after i.p. treatment with 14C-labeled MC-PROXYL or 14C-labeled carbamoyl-PROXYL. The black region shows high radioactivity and the white, no radioactivity, showing that MC-PROXYL, but not carbamoyl-PROXYL, can penetrate the BBB and is well distributed to brain tissue.

Figure 20.5 shows an example of EPR-based brain redox imaging in the mouse brain (2). From two small ROIs selected in the brain area, the result of EPR imaging showed that the different parts of the brain have different decay rates of the nitroxyl radical. However, anatomical information is not obtained from the EPR imaging experiment. The exact anatomical location of the ROIs in the brain cannot be estimated directly from the EPR image itself. Co-registering of EPR images of nitroxyl radical distribution with anatomical images from MRI is therefore necessary to reliably visualize the regions of interest where the redox reactions occur.

Fig. 20.5.

Time-resolved 2D EPR images in the head of a mouse. A 100 mL volume of CxP-AM (25 mM) in PBS with 10% (v/v) of ethanol was injected into the tail veins of mice and the data for images were collected at various time points. a Data collected 0.9–9.9 min after injection. b Data collected 10.4–19.3 min after injection, c Data collected 19.8–28.7 min after injection. d A semilogarithmic plot of the imaging intensity of two different regions (ROI 1 and ROI 2) in the brain after intravenous injection of CxP-AM.

5. NMR-Based Redox Imaging

If one needs to monitor the levels of nitroxyl probes, EPR spectral information is not required. In such applications, larger linewidths and spectral multiplicity of the EPR spectra would be interference in attempts to obtain the spatial distribution of nitroxyl radicals in vivo. Paramagnetic nitroxyl radicals, which have proton T1 shortening effect, can be detected using T1-weighted MRI. The feasibility of nitroxyl radicals as T1 contrast agents in MRI has been examined in the early 1980s, before their use in the field of EPR imaging. However, nitroxyl radicals were found to be not optimal as MR contrast agents in 1980s due to their low relaxivity and rapid in vivo bio-reduction. Now, recent MRI scanners operating at higher magnetic field with better signal to noise ratio and time-efficient T1-weighted pulse sequences once again make it useful to reconsider nitroxyl radicals as potential T1 contrast agents. Several problems (e.g., low spatial resolution, low temporal resolution, small sample volume) typical in EPR imaging experiments can be overcome using T1 contrast-based MRI. Two unique features distinguish nitroxyl radicals from Gd-based T1 contrast agents. (i) Being organic molecules of molecular weight ~ 200 Da, they can be specifically directed to extra- or intracellular locations. (ii) Unlike Gd-complexes which do not undergo biological redox transformations, nitroxides not only undergo reversible biological redox transformations to diamagnetic species but also depend on cellular redox status (62, 63), oxygenation status (38, 64), focal inflammatory processes involving ROS (65).

Figure 20.6 shows a simulation of T1-weighted gradient echo MR contrast as a function of concentration of a nitroxyl radical. The relaxivity of the nitroxyl radical used in this calculation was 0.13 mM−1s−1 at 37° C. At such a low relaxivity, the relationship between T1 enhancement and concentration of a contrast agent is almost linear especially in the lower concentration region below 2 mM.

Fig. 20.6.

Relationship between a paramagnetic nitroxyl contrast agent and an intensity change of T1-weighted SPGR-based MRI. a Simulated ΔM% increased with the concentration of paramagnetic nitroxyl contrast agent. b Low concentration region (<1.5 mM) in (a) (dotted rectangle area) was expanded. Fairly good linearity (R2 = 0.9995) was obtained between simulated ΔM% and the concentration of the low concentration region. Values used for the simulation were as follows: r1 = 0.13 mM−1 s−1, M0 = 1,000, TR = 75 ms, TE = 3 ms, FA = 45°, T1i = 2,350 ms, and T2* = 50 ms.

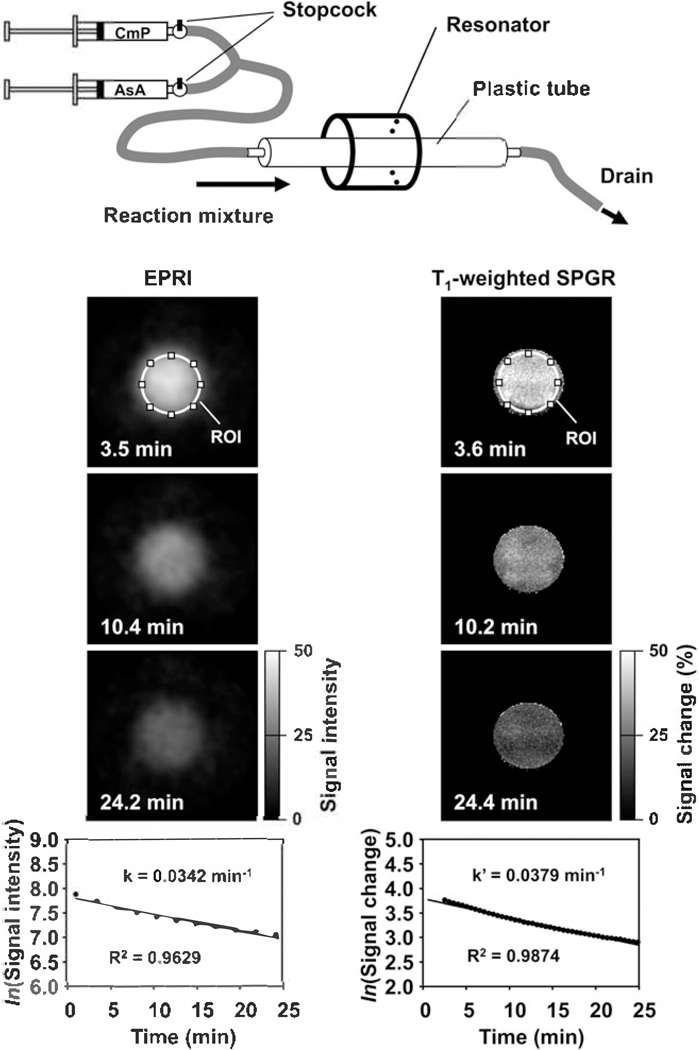

Figure 20.7 is a comparison of EPR imaging and T1-weighted MR imaging of nitroxyl radicals undergoing chemical reduction at a rate determined by the concentration of the reductant, ascorbic acid (AsA). Solutions of a nitroxyl radical and ascorbic acid were loaded in individual syringes and mixed rapidly to initiate the reaction in a cylindrical reactor placed within the resonator. Although MRI has a higher spatial and temporal resolution than EPR imaging, the decay rate was similar to that from EPR imaging (66). This decay rate obtained from MR T1-contrast can be treated as a pseudo-decay rate (67).

Fig. 20.7.

Comparison of EPR and MR redox imaging demonstrated using a phantom. Upper cartoon is a representation of the experimental device.

In vivo nitroxyl decay rate imaging in SCC tumor implanted in a mouse leg was examined using MRI (66). Figure 20.8a indicates the location of a 2 mm axial slice, including the SCC tumor bearing leg and the normal leg. Figure 20.8b shows a time course of nitroxyl-induced T1-weighted signal enhancement, ΔM%, after the injection of the nitroxyl contrast agent, carbamoyl-PROXYL, and the T2 map of the corresponding slice. The T1-weighted signal enhancement of a given pixel at (x, y) coordination, ΔM%x,y is as follows:

| (1) |

Fig. 20.8.

In vivo MR redox imaging. a Position of the slice scanned. b A time course of T1-weighted signal enhancement in the slice and a T2-mapping of the identical slice as a scout image. c A comparison of the time course of T1-weighted signal enhancement in the ROI-1 and ROI-2. d A redox map calculated based on the time course of nitroxyl-induced tissue T1-weighted signal enhancement.

where Sx,y is an image intensity of pixel (x, y). Image intensity enhancement via T1-contrast was enhanced in both normal and tumor tissues after the administration of carbamoyl-PROXYL and then gradually decreased with time. Figure 20.8c shows the time course of average ΔM% in ROI-1 and ROI-2. The tumor region showed faster decay rate than the normal region. The decay rate maps (Fig. 20.8d) showed clear difference between tumor region and normal tissues.

There is a question whether the in vivo decay of MR T1-contrast is a reduction of nitroxyl radical to the corresponding hydroxylamine or just a simple clearance of nitroxyl radical from the tissue. Chemically, the hydroxylamine can be oxidized to the corresponding nitroxyl radical by adding mild oxidant, such as potassium ferricyanide (FeK3(CN)6) after which the total amount of the nitroxyl agent in the tissue samples (nitroxyl radical form plus hydroxylamine form) can be measured and quantified by EPR (Fig. 20.9). From a set of five animals, whose tissue (both normal and tumor) were analyzed for nitroxyl content after chemical oxidation, it was found that the time course of the total amount of the nitroxyl in both tumor and normal tissues was stable during the time period used in the imaging experiment (Fig. 20.10). These observations suggest that the in vivo disappearance of T1-contrast induced by a nitroxyl contrast agent as a function of time is due to a reduction (67, 68).

Fig. 20.9.

Re-oxidation of a hydroxylamine to the corresponding nitroxyl radical by a chemical oxidant. Ferricyanide (FeK3(CN)6) has been usually used to oxidize hydroxylamine to the nitroxyl radical.

Fig. 20.10.

Time course of total amount (nitroxyl radical form + hydroxylamine form) of a contrast agent, carbamoyl-PROXYL, in normal and tumor tissues after i.v. injection.

6. Recent Trial of NMR-Based Brain Redox Imaging

Figure 20.11 shows nitroxyl-induced T1 contrast in the head region of mice. These images show varying distributions of nitroxyl contrast agents in the brain depending on their membrane permeability. Highly membrane permeable TEMPOL and CxP-M showed significant T1 contrast induction in whole brain area. Carbamoyl-PROXYL (CmP), which has a limited membrane permeability, showed modest T1 contrast in the brain, while the membrane impermeable CxP displayed no induction of T1 contrast in the brain. These results show that a membrane permeable nitroxyl contrast agent, such as TEMPOL or CxP-M, in combination with their antioxidant properties and their ability to participate in intracellular redox reactions, can be useful with MRI to assess tissue redox status in vivo in various organs of interest, including the brain.

Fig. 20.11.

Nitroxyl-induced T1 contrast at the head part of mice. a TEMPOL, b CxP-M, c carbamoyl-PROXYL, and d CxP showed difference of distribution in brain region.

Hyodo et al. (27) investigated the ability of CxP-M as a BBB-permeable MRI contrast agent in rats to monitor the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in the brain after reperfusion following defined periods of ischemia. In addition, they demonstrated fast T1 mapping acquired by a Look–Locker (LL) sequence (69). T1-weighted signal enhancement was readily noticed throughout the brain after administering CxP-M. Maximum T1-weighted signal enhancement, occurred at about 3 min after injection of CxP-M and returned to baseline by 15 min (Fig. 20.12a, c). The BBB-impermeable CxP, however, showed no enhancement of the T1-weighted signal in the brain region (Fig. 20.12b, d). Figure 20.12e shows the effect of cessation of blood flow on the reduction of CxP-M. When the blood flow was stopped by a KCl injection 40 s after administration of CxP-M, the respiration stopped, i.e., the rat died 15–20 s after KCl injection. MR signal intensity in the brain is still decreased after the death of a rat, except the reduction rate became slower than that found with normal cerebral perfusion. Disruption of blood perfusion and/or subsequent tissue injury, such as an ischemia-reperfusion (IR) model, can make abnormal redox status. For example, the reduction rate of CxP-M in the right hemisphere after reperfusion following ischemic periods was found to be significantly lower compared to that observed in the sham group (Fig. 20.12f) suggesting either a lower reduction rate of nitroxyls or a faster re-oxidation of the hydroxylamines to nitroxyls.

Fig. 20.12.

Time-course SPGR MR images of rat head region after injection of a CxP-M (cell-permeable) and b CxP (cell-impermeable). Contrast agents were injected 2 min after the MR scan was started. Sixty serial images were obtained in 20 min. The SPGR MR parameters were as follows: image resolution was 256 × 128 zero-filled to 256 × 256 (0.125 mm resolution), FOV = 3.2 × 3.2 cm, slice thickness = 2.0 and 0.2 mm gap. The number of slices was six. The green color shows % enhancement of MR signal intensity, ΔM%. The time courses of intensity change of c CxP-M and d CxP in the ROI of cerebral cortex (red color) and thalamus (blue color) are shown. e Intensity change of CxP-M without blood flow is shown. KCI (2 mL) was injected 40 s after CxP-M injection and rats died within 20 s.

While T1 is a quantitative value, the T1-weighted signal enhancement ratio is not always quantitative especially in a tissue of relatively short T1. Figure 20.13a shows a time course of T1 maps of the rat head region scanned before and after injection of CxP-M. T1 maps were obtained every 20 s with 13 slices (1.5 mm slice thickness) by the EPI-LL sequence. The T1 maps clearly showed the difference of T1 relaxation time between cerebral cortex and thalamus (Fig. 20.13a). The T1 relaxation times in cerebral cortex and thalamus before injection were 1,577 ± 19.9 and 1,315 ± 11.9 ms, respectively (Fig. 20.13b). The T1 values of these regions rapidly decreased after injection of CxP-M, and the minimum T1 values of cerebral cortex and thalamus regions were 1,034 ± 70.4 and 779 ± 70.2 ms, respectively. The recovery of T1 in the cerebral cortex and thalamus showed similar trends. According to the T1 changes before and after injection of CxP-M and in vitro relaxivity of CxP-M (0.16 mM−1s−1), the expected in vivo concentrations of CxP-M were calculated for all time points (Fig. 20.13c). The maximum concentrations in cerebral cortex and thalamus 30 s after injection were 1.9 ± 0.35 and 3.0 ± 0.50 mM, respectively. The CxP-M concentration calculated in the brain based on the T1 maps was in agreement with the results directly measured by ex-vivo EPR.

Fig. 20.13.

MRI signal dynamic of a SLENU and b SLCNUgly in the brain and surrounding tissues after i.v. injection in mice (0.4 mmol/kg b.w.). Each image was obtained within 20-s intervals using a Gradient-echo T1-weighted MRI. The red color in the images is the extraction of the signal between every single slide and the averaged baseline signal (first five slides – before injection). The red and black colors in the chart represent the MRI signal dynamic in the brain or entire area, respectively. A representative image from three independent experiments is shown in the figure.

7. MR Imaging of BBB-Permeable Drugs

A recent study demonstrated the feasibility of using a combination of nitroxyl radical linked with a therapeutic drug and the use of T1-weighted MRI to examine the BBB permeability of a nitroxyl labeled drug (70). This study demonstrates a BBB permeability for two TEMPO-labeled analogs (SLENU and SLCNUgly) of the anticancer drug Lomustine [1-(2-chloroethyl)-3-cyclohexyl-1-nitrosourea] using MRI at 7 T. SLENU and SLCNUgly were rapidly transported and randomly distributed in the brain tissue, which indicated that the exchange of the cyclohexyl part of Lomustine with TEMPO radical did not suppress the BBB permeability of the anticancer drug. In drug delivery imaging, nitroxyl-labeled anti-tumor drugs can therefore work not only as a tracer but may also have a role as a diagnostic probe for tumor physiology.

8. Conclusion

Brain redox imaging using a nitroxyl contrast agent as described in this chapter has a great potential to visualize the redox status in brain tissue. Non-invasive detection and visualization of the redox status in the brain will be an important contribution to the study of the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases, such as stroke, Parkinson’s disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Future therapeutic applications in these diseases can also be considered. Developing brain redox imaging techniques will be crucial to analyze redox phenomena and their influence on brain functions.

References

- 1.Sano H, Matsumoto K, Utsumi H. Synthesis and imaging of blood-brain-barrier permeable nitroxyl-probes for free radical reactions in brain ofliving mice. Biochem Mol Biol Int 1997;42:641–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sano H, Naruse M, Matsumoto K, Oi T, Utsumi H. A new nitroxyl-probe with high retention in the brain and its application for brain imaging. Free Radie Biol Med 2000;28:959–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samuni AM, DeGraff W, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB Nitroxides as antioxidants: Tempol protects against EO9 cytotoxicity. Mol Cell Biochem 2002;234/235:327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Krishna MC, Grahame DA, Samuni A, Bitchell JB, Russo A. Oxoammonium cation intermediate in the nitroxide-catalyzed dismutation of superoxide. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1992;89:5537–5541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ui I, Okajo A, Endo K, Utsumi H, Matsumoto K. Effect of hydrogen peroxide in redox status estimation using nitroxyl spin probe. Free Radie Boil Med 2004;37:2012–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Takeshita K, Utsumi H, Hamada A. Whole mouse measurement of paramagnetism-loss of nitroxide free radical in lung with a L-band ESR spectrometer. Biochem Mot Biol Int 1993;29:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miura Y, Utsumi H, Hamada A. Antioxidant activity of nitroxide radicals in lipid peroxidation of rat liver microsomes. Arch Biochem Biophys 1993;300:148–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blonder JM, McCalden TA, Hsia CJ, Billings RE Polynitroxyl albumin plus tempol attenuates liver injury and inflammation after hepatic ischemia and reperfusion. Life Sci 2000;67:3231–3239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Samuni AM, DeGraff W, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB Nitroxides as antioxidants: Tempol protects against EO9 cytotoxicity. Mot Cell Biochem 2002;234–235:327–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herrling T, Jung K, Fuchs J. Measurements of UV-generated free radicals/reactive oxygen species (ROS) in skin. Spectrochim Acta A 2006;63:840–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Venditti E, Scire A, Tanfani F, Greci L, Damiani E. Nitroxides are more efficient inhibitors of oxidative damage to calf skin collagen than antioxidant vitamins. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1780:58–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mitchell JB, DeGraff W, Kaufman D, Krishna MC, Samuni A, Finkelstein E, Ahn MS, Hahn SM, Gamson J, Russo A Inhibition of oxygen-dependent radiation-induced damage by the nitroxide superoxide dismutase mimic, tempol. Arch Biochem Biophys 1991;289:62–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goffman T, Cuscela D, Glass J, Hahn S, Krishna CM, Lupton G, Mitchell JB Topical application of nitroxide protects radiation-induced alopecia in guinea pigs. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1992;22: 803–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miura Y, Anzai K, Ueda J, Ozawa T. Novel approach to in vivo screening for radioprotective activity in whole mice: In vivo electron spin resonance study probing the redox reaction of nitroxyl. J Radiat Res 2000;41:103–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitolo JM, Cotrim AP, Sowers AL, Russo A, Wellner RB, Pillemer SR, Mitchell JB, Baum BJ The stable nitroxide tempol facilitates salivary gland protection during head and neck irradiation in a mouse model. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:1807–1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anzai K, Ueno M, Yoshida A, Furuse M, Aung W, Nakanishi I, Moritake T, Takeshita K, Ikota N. Comparison of stable nitroxide, 3-substituted 2,2,5,5-tetramethylpyrrolidine-N-oxyls, with respect to protection from radiation, prevention of DNA damage, and distribution in mice. Free Radie Biol Med 2006;40:1170–1178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Samuni A, Mitchell JB, DeGraff W, Krishna CM, Samuni U, Russo A. Nitroxide SOD-mimics: Modes of action. Free Radie Res Commun 1991; 12–13:187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeGraff WG, Krishna MC, Russo A, Mitchell JB Antimutagenicity of a low molecular weight superoxide dismutase mimic against oxidative mutagens. Environ Mot Mutagen 1992;19:21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krishna MC, Russo A, Mitchell JB, Goldstein S, Dafni H, Samuni A. Do nitroxide antioxidants act as scavengers of O2− or as SOD mimics? J Biol Chem 1996;271:26026–26031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsumoto K, Okajo A, Nagata K, DeGraff WG, Nyui M, Ueno M, Nakanishi I, Ozawa T, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC, Yamamoto H, Endo K, Anzai K. Detection of free radical reactions in an aqueous sample induced by low linearenergy-transfer irradiation. Biol Pharm Bull 2009;32:542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hahn SM, Krishna CM, Samuni A, DeGraff W, Cuscela DO, Johnstone P, Mitchell JB Potential use of nitroxides in radiation oncology. Cancer Res 1994;54:2006s–2010s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hahn SM, Krishna MC, DeLuca AM, Coffin D, Mitchell JB Evaluation of the hydroxylamine tempol-H as an in vivo radioprotector. Free Radie Biol Med 2000;28:953–958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hahn SM, Sullivan FJ, DeLuca AM, Krishna CM, Wersto N, Venzon D, Russo A, Mitchell JB Evaluation of tempol radioprotection in a murine tumor model. Free Radie Biol Med 1997;22:1211–1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cotrim AP, Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Sowers AL, Cook JA, Baum BJ, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB Differential radiation protection of salivary glands versus tumor by tempol with accompanying tissue assessment of tempol by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Cancer Res 2007;13:4928–4933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Subramanian S, Matsumoto K, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC Radio frequency continuous-wave and time-domain EPR imaging and overhauser-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of small animals: Instrumental developments and comparison of relative merits for functional imaging. NMR Biomed 2004;17:263–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Matsumoto K, Subramanian S, Murugesan R, Bitchell JB, Krishna MC Spatially resolved biologic information from in vivo EPRl, OMRl, and MRl. Antioxid Redox Signal 2007;9:1125–1141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hyodo F, Chuang KH, Goloshevsky AG, Sulima A, Gfiffiths GL, Mitchell JB, Koretsky AP, Krishna MC Brain redox imaging using blood-brain-barrier-permeable nitroxide MRl contrast agent. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008;28:1165–1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slemmer JE, Shacka JJ, Sweeney MI, Weber JT Antioxidants and free radical scavengers for the treatment of stroke, traumatic brain injury and aging. Curr Med Chem 2008;15:404–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yokoyama H, Kuroiwa H, Yano R, Araki T. Targeting reactive oxygen species, reactive nitrogen species and inflammation in MPTP neurotoxicity and parkinson’s disease. Neurol Sci 2008;29:293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guan ZZ Corss-talk between oxidative stress and modification of cholinergic and glutaminergic receptors in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Pharmacol Sci 2008;29:773–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manda K, Ueno M, Anzai K. Space radiation-induced inhibition of neurogenesis in the hippocampal dentate gyms and memory impairment in mice: Ameliorative potential of the melatonin metabolite, AFMK. J Pineal Res 2008;45:430–438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thotala DK, Hallahan DE, Yazlovitskaya EM Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3p attenuates neurocognitive dysfunction resulting from cranial irradiation. Cancer Res 2008;68:5859–5868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fuller CD, Schillerstrom JE, Jones WE 3rd, Boersma M, Royall DR, Fuss M. Prospective evaluation of pretreatment executive cognitive impairment and depression in patients referred for radiotherapy. Int JRadiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;72:529–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Utsumi H, Muto E, Masuda S, Hamada A. In vivo ESR measurment of free radicals in whole mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1990;172:1342–1348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Utsumi H, Yamada K. In vivo electron spin resonance-computed tomography/nitroxyl probe technique for non-invasive analysis of oxidative injuries. Arch Biochem Biophys2003;416:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Phumala N, Ide T, Utsumi H. Non-invasive evaluation of in vivo free radical reactions catalyzed by iron using in vivo ESR spectroscopy. Free Radic Biol Med 1999;26:1209–1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamatari M, Yasui H, Ogata T, Sakurai H. Local pharmacokinetic analysis of a stable spin probe in mice by in vivo L-band ESR with surface-coil-type resonator. Free Radic Res 2002;36:1115–1125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ilangovan G, Li H, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P. In vivo measurement of tumor redox environment using EPR spectroscopy. Mol Cell Biochem 2002;234/235:393–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yasukawa K, Kasazaki K, Hyodo F, Utsumi H. Non-invasive analysis of reactive oxygen species generated in rats with water immersion restraint-induced gastric lesions using in vivo electron spin resonance spectroscopy. Free Radic Res 2004;38: 147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takechi K, Tamura H, Yamaoka K, Sakurai H. Pharmacokinetic analysis of free radicals by in vivo BCM (blood circulation monitoring)-ESR method. Free Radic Res 1996;26:483–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matsumoto K, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB Novel pharmacokinetic measurement using X-band EPR and simulation of in vivo decay of various nitroxyl spin probes m mouse blood. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2004;310:1076–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsumoto K, Okajo A, Kobayashi T, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC, Endo K. Estimation of free radical formation by beta-ray irradiation in rat liver. J Biochem Biophys Methods 2005;63:79–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Okajo A, Matsumoto K, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC, Endo K. Competition of nitroxyl contrast agents as an in vivo tissue redox probe: Comparison of pharmacokinetics by the bile flow monitoring (BFM) and blood circulating monitoring (BCM) method suing X-band EPR and simulation of decay profiles. MMagn Reson Med 2006;56:422–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kuppusamy P, Afeworki M, ShankarR A, Coffin D, Krishna MC, Hahn SM, Mitchell JB, Zweier JL In vivo electron paramagnetic resonance imaging of tumor heterogeneity and oxygenation in murine model. Cancer Res 1998;58:1562–1568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kuppusamy P, Li H, Ilangovan G, Cardounel AJ, Zweier JL, Yamada K, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB Noninvasive imaging of redox status and its modification by tissue glutathione levels. Cancer Res 2002;62:307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ilangovan G, Li H, Zweier JL, Krishna MC, Mitchell JB, Kuppusamy P. In vivo measurement of regional oxygenation and imaging of redox status in RIF-1 murine tumor: Effect of carbogen-breathing. Magn Reson Med 2002;48:723–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamada K, Kuppusamy P, English S, Yoo J, Irie A, Subramanian S, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC Feasibility and assessment of non-invasive in vivo redox status using electron paramagnetic resonance imaging. Acta Radiol 2002;43:433–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ohno K, Watanabe M. Electron paramagnetic resonance imaging using magnetic-field-gradient spinning. J Magn Reson 2000;143:274–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Deng Y, He G, Petryakov S, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL Fast EPR imaging at 300 MHz using spinning magnetic field gradients. J Magn Reson 2004;168: 220–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Subramanian S, Koscielniak JW, Devasahayam N, Pursley RH, Pohida TJ, Krishna MC A new strategy for fast radiofrequency CW EPR imaging: Direct detection with rapid scan and rotating gradients. J Magn Reson 2007;186:212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Di Giuseppe S, Placidi G, Sotgiu A. New experimental apparatus for multimodal resonance imaging: Initial EPRI and NMRI experimental results. Phys Med Biol 2001;46:1003–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He G, Deng Y, Li H, Kuppusamy P, Zweier JL EPR/NMR co-imaging for anatomic registration of free radical images. Magn Reson Med 2002;47:571–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hyodo F, Yasukawa K, Yamada K, Utsurni H. Spatially resolved time-course studies of free radical reactions with an EPRI/MRI fusion technique. Magn Reson Med 2006;56:938–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lurie DJ, Bussell DM, Bell LH, Mallard J. R Proton electron double resonance imaging of free radical solutions. J Magn Reson 1988;76:366–370. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lurie DJ, Nicholson I, Foster MA, Mallard J. R Free radicals imaged in vivo in the rat by using proton-electron double-resonance imaging. Phil Trans R Soc Lond 1990;A333:453–456. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Krishna MC, English S, Yamada K, Yoo J, Murugesan R, Devasahayam N, Cook JA, Golman K, Ardenkjaer-Larsen JH, Subramanian S, Mitchell JB Overhauser enhanced magnetic resonance imaging for tumor oximetry: Coregistration of tumor anatomy and tissue oxygen concentration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002;99:2216–2221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Overhauser AW Polarization of nuclei in metals. Phys Rev 1953;92:411–415. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Utsuurni H, Yamada K, Ichikawa K, Sakai K, Kinoshita Y, Matsumoto S, Nagai M. Simultaneous molecular imaging of redox reactions monitored by overhauser-enhanced MRI with 14n- and 15n-labeled nitroxyl radicals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:1463–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Anzai K, Saito K, Takeshita K, Takahashi S, Miyazaki H, Shoji H, Lee MC, Masurnizu T, Ozawa T. Assessment of ESR-CT imaging by comparison with autoradiography for the distribution of a blood-brain-barrier permeable spin probe, MC-PROXYL, to rodent brain. Magn Reson Imaging 2003;21:765–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee MC, Shoji H, Miyazaki H, Yoshino E, Hori N, Miyake S, Ikeda Y, Anzai K, Ozawa T. Measurement of oxidative stress in the rodent brain using computerized electron spin resonance tomgraphy. Magn Reson Med Sci 2003;2:79–84. ‘ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyake N, Shen J, Liu S, Shi H, Liu W, Yuan Z, Pritchard A, Kao JPY, Kiu KJ, Rosen GM Acetoxymethoxy-carbonyl nitroxides as electron paramagnetic resonance proimaging agents to measure 02 levels in mouse brain: A pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006;318:1187–1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yamada K, Inoue D, Matsumoto S, Utsumi H. In vivo measurement of redox status in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rat using targeted nitroxyl probes. Antioxid Redox Signal 2004;6:605–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tsutsumi T, Ide T, Yamato M, Kudou W, Andou M, Hirooka Y, Utsuurni H, Tsutsui H, Sunagawa K. Modulation of the myocardial redox state by vagal nerve stimulation after experimental myocardial infarction. Cardiovasc Res 2008;77:713–721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Okajo A, Ui I, Manda S, Nakanishi I, Matsumoto K, Anzai K, Endo K. Intracellular and extracellular redox environments surrounding redox-sensitive contrast agents under oxidative atmosphere. Biol Pharm Bull 2009;32:535–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Utsuurni H, Yasukawa K, Soeda T, Yamada K, Shigemi R, Yao T, Tsuneyoshi M. Noninvasive mapping of reactive oxygen species by in vivo electron spin resonance spectroscopy in indomethacin-induced gastric ulcers in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2006;317:228–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Matsumoto K, Hyodo F, Matsumoto A, Koretsky AP, Sowers AL, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC High resolution mapping of tumor redox status by magnetic resonance imaging using nitroxides as redox-sensitive contrast agents. Clin Cancer Res 2006;12:2455–2462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Matsumoto K. Utility decay rates of T1-weighted MRI contrast based on redox-sensitive paramagnetic nitroxyl contrast agents. Biol Pharm Bull 2009;32: 711–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hyodo F, Matsumoto K, Matsumoto A, Mitchell JB, Krishna MC Probing the intracellular redox status of tumors with magnetic resonance imaging and redox-sensitive contrast agents. Cancer Res 2006;66:9921–9928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Chuang KH, Korestsky A. Improved neuronal tract tracing using manganese enhanced magnetic resonance imaging with fast Tl mapping. Magn Reson Med 2006;55:604–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhelev Z, Bakalova R, Aoki I, Matsumoto K, Gadjeva V, Anzai K, Kanno I. Nitroxyl radicals for labeling of coventional therapeutics and non-invasive magnetic resonance imaging of their permeability for blood-brain barrier: Relationship between structure, blood clearance, and MRI signal dynamic in the brain. Mot Pharm 2009;6:504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]