Malignant pleural mesothelioma (MPM) is a locoregionally aggressive malignancy with dismal outcomes. Trimodality therapy including neoadjuvant chemotherapy, surgical resection, and adjuvant radiotherapy (RT) is associated with a survival benefit in selected patients.1, 2 However, 50%-60% of patients are unable to complete trimodality treatment—resection is deferred because of disease progression during chemotherapy and RT is deferred because of postoperative complications.3 In their article, Nelson and colleagues4 explore factors affecting the likelihood of returning to RT after surgical resection for MPM.

The authors reviewed the medical records of patients with MPM completing surgical resection and the reasons they did not receive RT. Sixty-five percent of patients completed RT, which is consistent with published results.5 On multivariate analysis, smoking history and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score >3 were associated with decreased probability of RT completion (OR, 0.42 and 0.27). More than two-thirds of patients had ASA score >3, which, if accurate, should identify patients with severe systemic disease.6 Although ASA score is used by anesthesiologists in the preoperative assessment, it is unlikely that patients with severe systemic disease were selected for aggressive resection by this experienced group, which demonstrates the limitations of ASA score. Preoperative comorbidities and performance status measures, such as Karnofsky and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group, which can help to stratify patients, were not included in the study. On univariate analysis, cardiovascular or pulmonary complications were associated with a 50% decreased likelihood of RT completion.

Type of resection did not translate into significant differences in likelihood of RT completion. The limited prognostic value of resection type is consistent with previous findings from meta-analyses that, although early postoperative mortality is higher with extrapleural pneumonectomy, there is no difference in long-term survival.7 Whether patients with higher rates of comorbidities were selected for pleurectomy decortication over extrapleural pneumonectomy and whether this influenced results should be considered. Nevertheless, because resection type is not prognostic for completion of trimodal therapy, the authors do not suggest changes to the standard of care regarding choice of resection type.

The authors suggest patients with higher baseline rates of comorbidities should not be considered for cytoreduction. Respiratory complications are common after resection for MPM and can account for delay or avoidance of RT. However, these patients may also be at risk of significant respiratory complications following RT.8 Furthermore, 13% of patients did not complete RT because of bulky remaining or recurrent tumor, perhaps owing to tumor location; it is unlikely these patients would benefit from RT without surgery. As the authors group previously demonstrated, multimodality therapy including surgery is superior to medical management alone.9 Thus, failure to complete RT does not justify forgoing surgery.

Patients with a lower likelihood of RT completion or who are at risk of surgical complications might benefit from emerging therapies such as immunotherapy to complete or replace the trifecta. RT may boost antitumor immune responses, especially when given at or in a rationally based dose or regimen.10 Rational combinations of existing and emerging therapies should be investigated in the management of MPM.

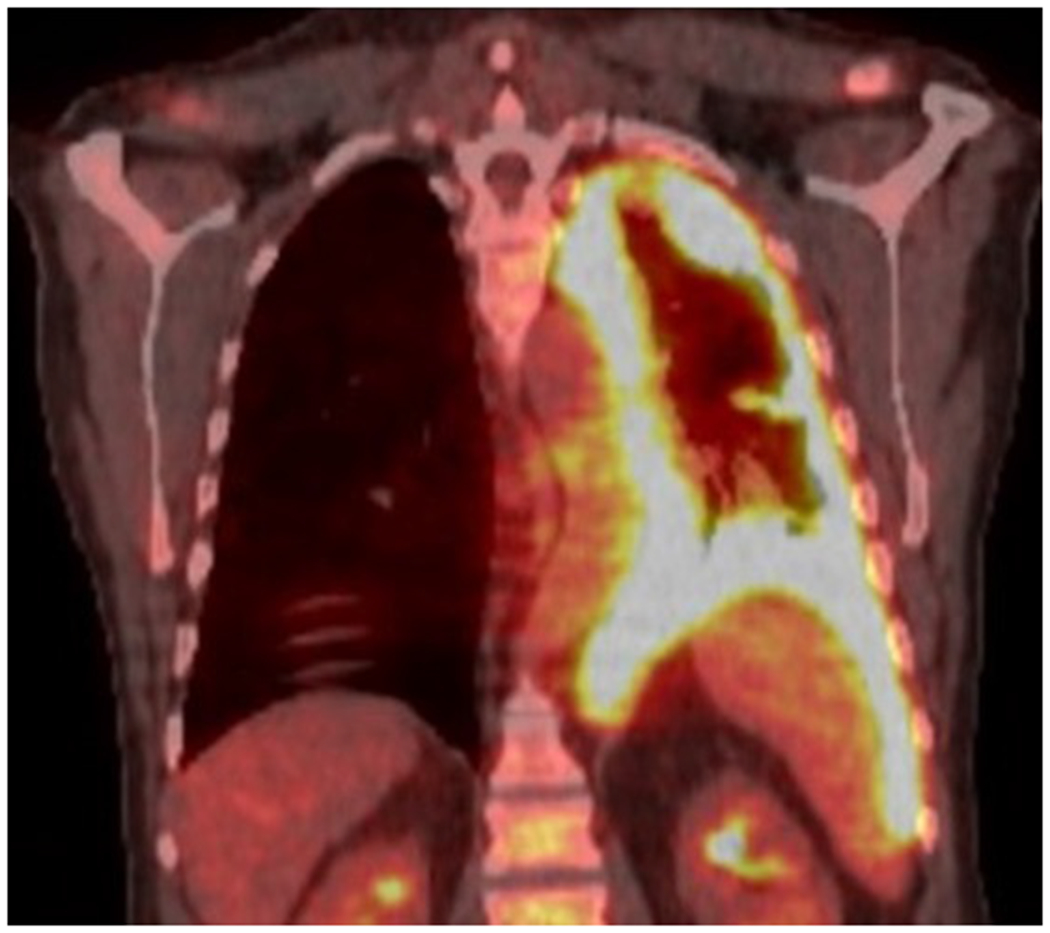

Figure 1:

PET scan demonstrating malignant pleural mesothelioma

Central message:

Rational combinations of existing and emerging therapies should be investigated in the management of malignant pleural mesothelioma.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have nothing to disclose with regard to commercial support.

References

- 1.Gomez DR, Hong DS, Allen PK, Welsh JS, Mehran RJ, Tsao AS, et al. Patterns of failure, toxicity, and survival after extrapleural pneumonectomy and hemithoracic intensity-modulated radiation therapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8:238–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shaikh F, Zauderer MG, von Reibnitz D, Wu AJ, Yorke ED, Foster A, et al. Improved Outcomes with Modern Lung-Sparing Trimodality Therapy in Patients with Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2017;12:993–1000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Casiraghi M, Maisonneuve P, Brambilla D, Solli P, Galetta D, Petrella F, et al. Induction chemotherapy, extrapleural pneumonectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2017;52:975–981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson DB, Rice DC, Mitchell KG, Tsao AS, Gomez DR, Sepesi B, et al. Return to Intended Oncologic Treatment After Surgery for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2019; 158:924–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rimner A, Zauderer MG, Gomez DR, Adusumilli PS, Parhar PK, Wu AJ, et al. Phase II Study of Hemithoracic Intensity-Modulated Pleural Radiation Therapy (IMPRINT) As Part of Lung-Sparing Multimodality Therapy in Patients With Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:2761–2768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sankar A, Johnson SR, Beattie WS, Tait G, Wijeysundera DN. Reliability of the American Society of Anesthesiologists physical status scale in clinical practice. Br J Anaesth. 2014;113:424–432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taioli E, Wolf AS, Flores RM. Meta-analysis of survival after pleurectomy decortication versus extrapleural pneumonectomy in mesothelioma. Ann Thorac Surg. 2015;99:472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chance WW, Rice DC, Allen PK, Tsao AS, Fontanilla HP, Liao Z, et al. Hemithoracic intensity modulated radiation therapy after pleurectomy/decortication for malignant pleural mesothelioma: toxicity, patterns of failure, and a matched survival analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91:149–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nelson DB, Rice DC, Niu J, Atay S, Vaporciyan AA, Antonoff M, et al. Long-Term Survival Outcomes of Cancer-Directed Surgery for Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma: Propensity Score Matching Analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3354–3362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho BC, Feld R, Leighl N, Opitz I, Anraku M, Tsao MS, et al. A feasibility study evaluating Surgery for Mesothelioma After Radiation Therapy: the “SMART” approach for resectable malignant pleural mesothelioma. J Thorac Oncol. 2014;9:397–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]