Abstract

Purpose

While the annual rate of new HIV infections and diagnoses has remained stable for most groups, troubling increases are seen in transgender women and racial/ethnic-minority men who have sex with men (MSM), groups that are disproportionately affected by HIV. The primary purpose of this systematic review is to examine factors that impact attitudes and beliefs about preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and treatment as prevention (TasP) and to explore barriers to PrEP uptake in MSM and transgender women.

Methods

Using MeSH terms and relevant keywords, we conducted a systematic review of studies published between 2010 and 2019. We searched 4 literature databases and identified studies on MSM and transgender women to elucidate perceptions of PrEP and TasP as well as barriers to access.

Results

The search yielded several prominent themes associated with beliefs about HIV prevention approaches and barriers to PrEP access in MSM and transgender women. One was a lack of awareness or insufficient knowledge of PrEP and TasP. Structural barriers and geographic isolation also prevent access to HIV prevention. Sexual minority and HIV-related stigma, internalized homonegativity, and misinterpretations of messages within HIV prevention campaigns have negatively impacted PrEP uptake and beliefs about PrEP and TasP. Quality of the relationship MSM or transgender people have with their health care provider can facilitate or hinder HIV prevention. Finally, variability in beliefs about the efficacy of TasP has negatively affected the impact of TasP messaging campaigns.

Conclusions

Although there is evidence of increasing PrEP use in at-risk individuals, several barriers prevent wider acceptance and uptake. Misunderstanding about the meaning of “undetectable” and skepticism about the evidence behind TasP messaging campaigns are likely to delay the World Health Organization’s stated goal of getting to zero transmissions.

Keywords: HIV, preexposure prophylaxis, MSM, transgender women, treatment as prevention

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved Truvada® (200 mg emtricitabine/300 mg tenofovir disoproxil fumarate; Gilead Sciences, Inc.) for preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) of HIV in adults in 2012 and expanded use for at-risk adolescents in 2018.1 PrEP has proved to be an effective biomedical approach to HIV prevention in which HIV-negative individuals use an antiretroviral medication to reduce the risk of seroconversion.2 For optimal efficacy of PrEP for HIV prevention, patients must understand their HIV risk level, have good health literacy and access to health information, maintain access to PrEP medication and health care services, have a strong commitment to taking medication daily, and feel comfortable engaging in treatment with a trusted health care provider.

An additional approach to HIV prevention is treatment as prevention (TasP), which has been endorsed by the World Health Organization and the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as an effective population health strategy. Empirical evidence from clinical trials, beginning with the landmark HPTN 052 study, indicated that sustained suppression of HIV viral load in HIV-positive patients effectively eliminates the risk of transmission to HIV-negative sexual partners.3,4 Following the HPTN 052 study, the large-scale PARTNER1 and PARTNER2 studies provided further evidence on viral suppression and HIV transmission through condomless sex for gay and heterosexual serodiscordant or mixed-status couples.5 While TasP can be effective in preventing HIV transmission, the existing body of literature suggests minimal research has been conducted to assess attitudes and beliefs toward TasP or people’s willingness to act on beliefs about TasP. From the few studies published, findings suggest variability in knowledge and beliefs about TasP.4,6,7

Despite the availability of HIV prevention services, complex socioecological factors may serve as barriers to access. HIV case data and U.S. health statistics suggest that the rate of new HIV infections has remained stable over the past several years but is increasing in some groups of people.8,9 Comparing new HIV infections (ie, “HIV incidence”) in 2016 and 2010, the CDC found that the infection rate for Hispanic/Latino gay and bisexual men increased and that African Americans and Hispanics/Latinos were disproportionately affected by HIV. There is a critical need to fully understand and address all factors contributing to the health disparities seen in sexual and racial minorities.

The primary purpose of this systematic review is to examine factors that affect beliefs about PrEP and TasP and to explore barriers to PrEP uptake in men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women.

METHODS

Search Strategy

In April 2019, we conducted a literature review using 4 databases as sources (MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Health Source: Nursing/Academic Edition) to identify articles on perceptions of PrEP and TasP, using terms for our target population. We used database limiters and the search terms “MSM,” “men who have sex with men,” and “transgender women” to target studies conducted with our population of interest. We also sought articles that explored barriers to PrEP uptake in MSM and transgender women. We used MeSH terms in CINAHL and MEDLINE for relevant keywords such as “HIV,” “PrEP,” “pre-exposure prophylaxis,” “HIV prevention,” “TasP,” and “treatment as prevention.” These search terms were used in PsycINFO as keywords.

Eligibility Criteria

We limited our search to full-text, peer-reviewed articles published in academic journals between January 2010 and April 2019. Although FDA approval of medication for PrEP did not occur until 2012, we included articles published between 2010 and 2012 to assess awareness or knowledge of PrEP, as it was under investigation as a prevention option. We limited the subject to “HIV prevention” and subject subset to “HIV/AIDS” in databases offering the limiter to ensure the return of articles for which prevention was the main idea of the study exploration. When prevention research was not a focus, those articles were excluded from analysis.

Study Selection

Citations were managed using Zotero 5.0 (Corporation for Digital Scholarship). Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by the primary reviewer; when relevance was unclear, the full text was obtained. As a reliability check, a second rater checked the eligibility of all located papers. All excluded articles and studies were maintained in the citation manager with a note indicating the reason for exclusion. We included studies conducted on adult populations within the United States when a specific aim was the exploration of barriers to PrEP use or attitudes about PrEP and TasP. We excluded articles and studies that did not include a sample of MSM or transgender women.

RESULTS

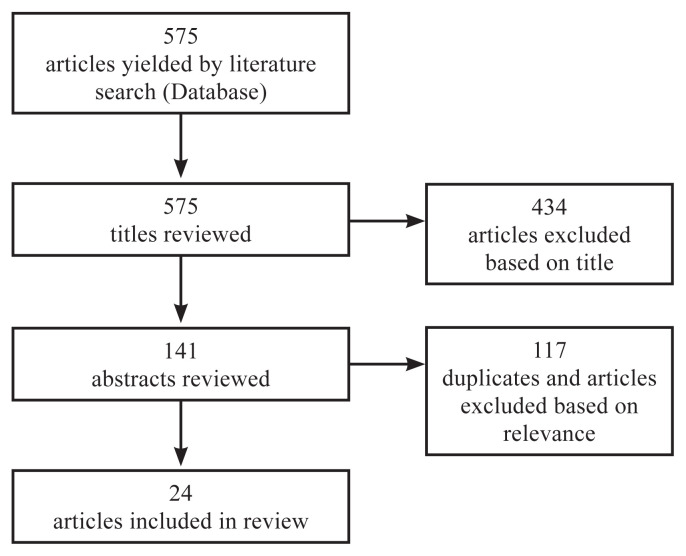

Searches using the terms yielded a total of 575 records. We first reviewed article titles and found 141 potential articles for inclusion. After examining abstracts to further eliminate unrelated articles, a total of 24 nonduplicated full-text articles met the inclusion criteria and were included for discussion in this review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Systematic literature review flowchart.

One frequently occurring challenge with research on transgender populations is the poor capture of data that are unique to the population. For example, data collected about sexual orientation and sex-related behaviors of transgender women would help eliminate barriers and further clarify needs in terms of HIV prevention. For our purposes, we included articles that referred to transgender women or transgender women who have sex with men.

This systematic review of the literature yielded some major themes that were categorized as key barriers and missed opportunities. Table 1 indicates the final number of articles meeting the inclusion criteria, according to barriers addressed by the population of interest. While identified barriers are discussed individually, it is reasonable to assume that the challenges faced are a result of the complex interaction of these barriers and how each influences the strength or direction of the relationship between other barriers as they exist over time.

Table 1.

Articles Meeting Inclusion Criteria (n=24) by Barrier Type

| Author(s) | Year | Title | Focus | Barriers (population) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Golub et al20 | 2013 | From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City | PrEP | knowledge, stigma, providers (MSM, TW) |

| Escudero et al31 | 2015 | Inclusion of trans women in pre-exposure prophylaxis trials: a review | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma (TW) |

| Eaton et al10 | 2015 | Minimal awareness and stalled uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis among at risk, HIV-negative, black men who have sex with men | PrEP | knowledge, structural, providers (MSM) |

| Parker et al36 | 2015 | Patient experiences of men who have sex with men using pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection | PrEP | providers (MSM) |

| Pérez-Figueroa et al2 | 2015 | Acceptability of PrEP uptake among racially/ethnically diverse young men who have sex with men: the P18 study | PrEP | knowledge, structural (MSM) |

| Sevelius et al11 | 2016 | ‘I am not a man’: trans-specific barriers and facilitators to PrEP acceptability among transgender women | PrEP | knowledge, structural, providers (TW) |

| Wilson et al12 | 2016 | Awareness, interest, and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis candidacy among young transwomen | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma, individual-adherence (TW) |

| Lelutiu-Weinberger and Golub13 | 2016 | Enhancing PrEP access for black and Latino men who have sex with men | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma, providers (MSM) |

| Garcia et al32 | 2016 | Psychosocial implications of homophobia and HIV stigma in social support networks: insights for high-impact HIV prevention among black men who have sex with men | PrEP | structural, stigma (MSM) |

| Hubach et al17 | 2017 | Barriers to access and adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) in a relatively rural state | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma, provider (MSM) |

| Holloway et al33 | 2017 | Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis willingness among young men who have sex with men who use geosocial networking applications in California | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma, individual-risk perception (MSM) |

| Rolle et al25 | 2017 | Challenges in translating PrEP interest into uptake in an observational study of young black MSM | PrEP | knowledge, structural (MSM) |

| Gupta et al14 | 2017 | Low awareness and use of preexposure prophylaxis in a diverse online sample of men who have sex with men in New York City | PrEP | knowledge (MSM) |

| Marks et al24 | 2017 | Potential healthcare insurance and provider barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among young men who have sex with men | PrEP | structural (MSM) |

| Cahill et al21 | 2017 | Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma (MSM) |

| LeVasseur et al38 | 2017 | The effect of PrEP on HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in the context of condom use, treatment as prevention, and seroadaptive practices | PrEP, TasP | knowledge, structural, individual-adherence (MSM) |

| Pawson and Grov22 | 2018 | 'It's just an excuse to slut around': gay and bisexual mens' constructions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis as a social problem | PrEP | knowledge, stigma (MSM) |

| Parisi et al18 | 2018 | A multicomponent approach to evaluating a pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation program in five agencies in New York | PrEP | knowledge, structural, individual-retention (MSM, TW) |

| Goedel et al40 | 2018 | Effect of racial inequities in pre-exposure prophylaxis use on racial disparities in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men: a modeling study | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma (MSM) |

| Garnett et al15 | 2018 | Limited awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City | PrEP | knowledge, structural (MSM, TW) |

| Zucker et al41 | 2018 | Missed opportunities for engagement in the prevention continuum in a predominantly black and Latino community in New York City | PrEP | structural (MSM) |

| Elopre et al19 | 2018 | Perceptions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among young, black men who have sex with men | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma (MSM) |

| Rendina and Parsons4 | 2018 | Factors associated with perceived accuracy of the Undetectable = Untransmittable slogan among men who have sex with men: implications for messaging scale-up and implementation | TasP | knowledge (MSM) |

| Marcus et al16 | 2019 | Barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis use among individuals with recently acquired HIV infection in Northern California | PrEP | knowledge, structural, stigma, providers |

MSM, men who have sex with men; PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis; TasP, treatment as prevention; TW, transgender women.

Results are further summarized in the Discussion section. Findings regarding PrEP are presented first, followed by findings related to TasP.

DISCUSSION

Lack of Awareness or Insufficient Knowledge About PrEP

Overall, the literature suggests that a key barrier to PrEP uptake is a lack of awareness or insufficient knowledge about PrEP, especially with younger people, black and Latino MSM, transgender people, and individuals with lower education and income levels.10–16 Information about PrEP is not reaching all at-risk groups, and there is significant variability in the source and quality of the information. Perez-Figueroa et al found that only half of their study participants (N=100) who were young MSM living in New York City had “some knowledge” about PrEP as a form of HIV prevention.2 Efforts to achieve zero HIV infections will be disrupted without knowledge or access to accurate information about PrEP.

Poor access to or low participation in sexual health education exacerbates the problem of insufficient knowledge about PrEP, as does geographical isolation for those living in rural communities.17 People connected to one or more HIV testing sites or other nonclinical community-based organizations had higher PrEP awareness and knowledge.14 Participants of studies or programs that provided psychoeducation and adequate PrEP information held positive beliefs about PrEP and expressed high interest after receiving adequate information.10 An effective approach to addressing the lack of awareness and insufficient information acquisition may be for HIV prevention programs that offer PrEP to collaborate with community-based organizations and conduct community outreach. This model has been shown to improve health care entities’ ability to identify, recruit, and retain patients.18 However, information and outreach must align with the unique needs of the intended patient. Studies looking into PrEP awareness in transgender populations find the absence of trans-inclusive educational and marketing PrEP materials to be a significant barrier to knowledge and access.11

A study by Marcus and colleagues attempted to elucidate the problem of lack of PrEP knowledge by surveying people recently diagnosed with HIV. Among 122 Northern California respondents recently diagnosed with HIV, only 30% reported having discussed PrEP with a health care provider before their diagnosis, and only 4.1% of those surveyed reported prior PrEP use. For those with information about PrEP, financial concerns (eg, prescription costs, availability, and cost of insurance coverage) was a prevalent barrier to PrEP uptake, especially for people with lower incomes.16

In terms of information exchange, some individuals seek out information from trusted friends or gay-friendly settings, while others utilize online discussion groups or social networks.15 The anonymity of online groups discussing sexual health topics may allay stigma concerns and serve as a facilitator for obtaining information, especially for black MSM and transgender women. However, the accuracy of that information may vary. Despite the benefits of the internet and online groups, seeking information about PrEP and eligibility can be difficult for those residing in communities where stigma is high and LGBT-targeted resources are scarce.19

For those with some PrEP awareness, insufficient knowledge led to inaccurate beliefs about PrEP or unaddressed concerns. Some concerns and beliefs documented in the literature were fear that PrEP use would result in increased high-HIV-risk behaviors, belief that serious long-term consequences from PrEP use would occur, belief that PrEP was limited to serodiscordant couples, and concerns that antiretroviral drugs used as PrEP would no longer work in the case of seroconversion.20–22 Focus groups and studies with racial and ethnic minorities who identify as MSM indicated deeply held concerns about the use of PrEP. One commonly cited obstacle to PrEP initiation was fear about side effects, many of which were largely exaggerated or untrue.6,23 Support and psychoeducation about PrEP during the exploration or initiation phase of PrEP treatment could help allay concerns so that patients can make better-informed decisions. Ensuring that patients can obtain accurate information, have forthcoming conversations with their providers, and obtain the needed support to manage adherence will improve prevention efficacy and increase knowledge accuracy. Many patients who learn more about PrEP and side effects are more willing to consider PrEP as an HIV prevention option.21

Structural Barriers and Geographical Isolation

Important structures for facilitating availability and accessibility to health care include community institutions, public and private health insurance, and health care systems. These structures also serve as a barrier to access, especially for young people and racial or ethnic minorities, which is often compounded by issues of socioeconomic status and geographical isolation.24 Delay in time from request to prevention services, lack of insurance or insufficient insurance coverage, cost of prescriptions or co-payment, and geographical limitations to accessing facilities and providers with sufficient knowledge about antiretroviral drugs and PrEP were identified barriers to PrEP initiation.17,21,24–26 Additionally, community clinics may be perceived as serving a singular purpose of treating people with sexually transmitted infections. This perception prompts fear and an unwillingness to utilize community clinics to obtain HIV prevention information or PrEP, especially in MSM who reside in rural areas or stigmatizing environments in the United States.17

For communities of color living in the southern region of the United States, PrEP uptake has been slow due to cultural barriers, stigma about HIV and gay men, geographical isolation, and cost of health care services and medication.2,15,21,24 These factors also serve as barriers to PrEP awareness, inaccurate assessment of a patient’s HIV risk by health care providers, and missed opportunities to address issues related to cost and affordability.16,17 Proper linkage to health care and the ability to maintain consistent access to facilities, providers, health insurance, pharmacies, and community organizations are essential for effective use of PrEP as HIV prevention.

Where public transportation may be inefficient or unavailable, telehealth-based interventions may help keep MSM and transgender women connected to community-based organizations and health care providers. Telehealth has shown promise for keeping patients engaged in treatment, especially for stigmatizing medical conditions such as HIV. There is potential for telehealth to support linkage to prevention and treatment services as well.27

Stigma Associated with MSM, HIV, and PrEP

Sexual-related stigma and stigmatizing attitudes about HIV can lead to fear, testing and prevention interference, poor knowledge about transmission and risk level, misperceptions about sexual minorities, and health disparities. HIV-associated stigma has been linked to adverse health and psychosocial events and vulnerability to poorer mental health outcomes in people living with HIV.28,29 Negative outcomes from enacted or anticipated stigma result by way of internal or external mechanisms. At the individual level, MSM or transgender women may internalize stereotypes and negative beliefs held at the community or structural levels, impacting how they feel about their sexual or gender identity. Further, HIV- and MSM-related stigma may transfer to PrEP and HIV prevention approaches, treatment, or community institutions serving those impacted by HIV. These negative attitudes and beliefs may serve as a barrier to PrEP uptake or utilization of community-based services for sexual minorities or those at risk for HIV. For MSM, when internalized homonegativity is high, feelings of guilt and shame along with social isolation can lead to disavowing the sexual minority identity or focusing on behaviors that serve to distance the person from the identity.30

Sexual minority stigma, HIV-related stigma, and PrEP-related stigma were found to negatively impact attitudes about PrEP and HIV prevention strategies, especially in gender, ethnic, and racial minority groups.17,20,22,31–33 Stigma and the intersectionality of race, ethnicity, sexual minority status, and geographical location perpetuate health disparities in HIV and sexually transmitted infections, especially in rural and socially conservative populations. While having limited numbers of HIV prevention and treatment centers within a community is a barrier to accessing PrEP, internalized homonegativity is associated with HIV testing frequency and likewise serves as a barrier to PrEP acceptance and uptake.17,30,32 MSM or transgender women who experience a higher level of stigma within their communities are less likely to engage in HIV testing or other preventive measures that may require behavioral effort, which leads to missed opportunities to receive accurate information about PrEP and explore PrEP as an option after testing negative for HIV.30

The degree to which HIV-related stigma impacts PrEP uptake is not fully understood. Findings from our systematic review indicate that some HIV-negative MSM and transgender women hold grave concerns about what others will think if they were to start PrEP.20 Internalized homonegativity, HIV-related stigma, and perceived and enacted stigma continue to harm both people living with HIV and those who wish to obtain prevention services given their engagement in high-HIV-risk behaviors.32 Findings from HIV-related stigma studies indicate that the ability to take care of one’s self through medication and the use of antiretroviral therapies can decrease with the increase of HIV stigmatization, resulting in life-threatening consequences.34 It is not unreasonable to assume that this form of HIV-related stigma also would negatively impact adherence to PrEP treatment in both MSM and transgender women.

Messaging from HIV prevention campaigns is critical for dismantling HIV stigmatization or promoting HIV prevention. However, these messages may be misinterpreted by those who internalize HIV- or PrEP-related stigma. Despite years of PrEP availability, PrEP-related stigma continues to exist and serves as a barrier to uptake. This stigma prevents the initiation of important discussions about HIV prevention and sexual health as well as the correction of negative beliefs held by some that PrEP is for sexually promiscuous people or will cause an increase in risky sexual behavior.19,35 Some MSM and transgender women who have sex with men hold PrEP-related stigma along with conspiracy-related beliefs arising from mistrust with government entities and the pharmaceutical industry.35

While some MSM associate PrEP with sexual promiscuity, others fear rejection and discrimination from potential sex partners should they disclose their use of PrEP.22 For black MSM, PrEP-related stigma is exacerbated by the complexity of reconciling their self-constructed meaning about being black, gay, and living in the South, with public health messaging around HIV as a social problem.19 Individuals with multiple stigmatizing identities are aware of their invisibility to others and the existence of discrimination and negative stereotypes. Professionals working with black MSM must support their patients’ efforts to untangle the internalized stigma associated with each identity and realize a self-identity that is free from guilt and shame. Only then will these young men be better able to advocate for their health and well-being.

Understanding and addressing the central factors associated with stigma as a barrier to PrEP uptake is critical (Table 2). Health care entities may find success from partnerships with community-based organizations that have earned the trust of community members and leaders. Targeted anti-stigma campaigns and HIV prevention education is key to dismantling harmful beliefs about for whom PrEP is intended. Frameworks emphasizing self-efficacy and internal locus of control may help reduce beliefs about PrEP causing increased sexual risk-taking.

Table 2.

Major Factors Impacting Attitudes and Beliefs About PrEP and Treatment as Prevention

| Factors | Possible solution(s) |

|---|---|

|

Increase opportunities to receive educational materials about HIV and approaches to prevention through social media, advertising, and messaging campaigns in targeted settings. Create content with the unique needs of diverse patient populations in mind. |

|

Focus on HIV and effective prevention and refrain from discussing risk behaviors in ways that may cause shame or guilt. Information and conversations should consider sociopolitical context specific to region, while focusing on empowerment and self-efficacy. Actively engage in efforts to correct misperceptions about the purpose of PrEP and who it is intended for. |

|

Increase representation of sexual and gender minorities in health care and public health settings. Increase public knowledge about cost of research and development in pharmaceuticals while advocating for public policies that minimize financial barriers to those who need PrEP most. Make cultural-competency training for providers visible to patients and the public while creating spaces that are inclusive to sexual and gender minorities. |

PrEP, preexposure prophylaxis.

Health Care Providers

Health care providers offer an opportunity to serve as a reliable informant to patients at risk of HIV or in need of accurate information about prevention practices. Physicians take an oath in the conduct of their professional activities that promote advocacy of patient welfare and sensitivity to a diverse patient population. Unfortunately, several sexual and gender minority populations have reported concerns about discussing matters of sexual health with their primary care providers, effectively serving as a barrier to PrEP knowledge and access.17,20 Stigma and living in geographically isolated areas seem to magnify the problem of health care providers as barriers to PrEP for those who cite mistrust of providers as a barrier to patient-provider collaboration about HIV and sexual health.21,24,33 There appear to be significant regional differences in terms of stigma and discrimination experiences, and forecasted stigma negatively impacts a patient’s level of disclosure and the overall patient-provider relationship.21,24

In focus groups with MSM, some patients who inquired about or requested PrEP reported insensitive or dismissive responses from primary care providers that range from advising an end to the sexual or romantic relationship due to HIV risk to explicit anti-gay stigma within the health system by some health care staff.21 Physician reaction to the patient’s initial disclosure may dictate whether future discussion occurs again, especially for patients who are gender nonconforming or identify as transgender.11,17

There is evidence to suggest that some health care providers hold mistaken beliefs about who is at risk of HIV infection or make inaccurate assumptions about risk levels in different patients.11 Other providers lack familiarity with PrEP, believe that infectious disease specialists or HIV specialists are best suited for prescribing PrEP, or cite issues about reimbursement and prescription coverage that impede treating patients seeking PrEP or HIV prevention services.16,36,37 Unfortunately, factors associated with a provider’s comfort- or knowledge-level about PrEP contribute to the disparate burden of HIV in MSM and transgender women who would be good candidates for PrEP.16,38

It is not implausible that given the long history of HIV and prevention messaging emphasizing abstinence or condom use, many providers may have concerns about messaging that does not emphasize the use of condoms. Many individuals in HIV-serodiscordant relationships may prefer to engage in condomless sex and use evidence from TasP studies to inform their decision. These empirical studies conclude that sustained suppression of HIV viral load effectively eliminates the risk of HIV transmission between serodiscordant sexual partners.3–5 Concerns about other sexually transmitted infections, viral rebound in HIV-positive patients due to viral “blips,” and possible antiretroviral drug nonadherence dampen health professionals’ enthusiasm about PrEP and willingness to discuss TasP as a prevention strategy with their patients.4

Overall, mistrust toward providers, the health care system, and the pharmaceutical industry, along with skepticism about the effectiveness of PrEP, serve as barriers to PrEP information and uptake in transgender women and racial-minority MSM.11,13,21 Compared to other MSM, black and Latino MSM hold greater mistrust about PrEP, further impacting discussions about sex and sexual health with providers.13,39

Examining attitudes and beliefs held by health care providers about HIV prevention and PrEP, and training providers about PrEP and care for sexual and gender minority populations, are essential to improving patient-provider relationships. It may be necessary to scale up access to PrEP, in addition to HIV testing, antiretroviral drugs, and risk assessments. Scale-up may require bringing in primary care providers to help identify ways they can contribute to this effort and become more culturally competent. When patients trust their providers and believe they will not be admonished or judged for their sexual behaviors, they are more likely to engage in frank discussions about sexual health and accurately assess their HIV risk. Provider collaboration with the patient leads to improved care that meets the unique situational needs of the patient.

Variability in Beliefs About TasP Efficacy

TasP is an effective approach to HIV prevention in which HIV-positive patients achieve a sustained suppressed plasma viral load (ie, less than 200 copies/ml), eliminating the chance of transmitting the virus to an HIV-negative sexual partner.3–5 The World Health Organization’s “undetectable = untransmittable” (U=U) messaging campaign is based on this approach. The U=U campaign aims to increase awareness of TasP and encourage individuals with HIV who receive antiretroviral drug treatment to achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load so they cannot transmit the virus to others. U=U is grounded in treatment as prevention science arising out of the empirical evidence from the HPTN 052, PARTNER1, and PARTNER2 studies.5,7

Overall, few studies examined the attitudes and beliefs of MSM and transgender women about TasP. Although the U=U campaign is expanding, many people either do not understand what undetectable means or believe the message conveyed is partially or entirely inaccurate.4 Rendina and Parsons conducted a nationwide study of gay and bisexual MSM in the United States to examine sociodemographic and behavioral factors associated with different perceptions of U=U messaging. Their findings indicated that subgroups of uninfected and HIV-positive people would benefit from targeted campaign messaging to improve understanding about U=U and eliminate misperceptions about the accuracy of the message.4

It is likely that U=U campaign messaging could be valuable in influencing public opinion in a positive direction. Stigma, low health literacy, and access barriers continue to serve as a critical barrier to HIV testing and prevention services. Additional studies are needed to determine whether U=U messaging can help destigmatize HIV, reduce fears about HIV, and increase awareness about all HIV prevention options.

Limitations

A number of limitations in our methodology should be considered. First, we did not include unpublished grey literature, which could fill gaps in the academic literature. Our rationale was to focus exclusively on peer-reviewed, published literature. Further, we had further concerns about the challenges and time required to systematically evaluate the grey literature. Also, we limited our review to English-language articles, posing a risk of publication bias. Finally, we opted to use the search term “HIV OR AIDS” and did not include “human immunodeficiency virus,” which may have resulted in a smaller sample of studies.

CONCLUSIONS

Most of the literature on HIV prevention attitudes, beliefs, and engagement in MSM or transgender women focuses on preexposure prophylaxis. PrEP is considered an effective biomedical approach to HIV prevention. Although there is evidence of increasing PrEP use in at-risk individuals, several barriers prevent wider acceptance and uptake. While health care policy and regulatory changes have occurred to increase parity for LGBT health and minimize financial barriers, other psychosocial and systemic barriers may work to diminish the success of these policy changes. The barriers identified in this systemic review are complex and sometimes interconnected in ways that prevent the uptake of PrEP.

There is a paucity of literature on perceptions, attitudes, and beliefs about TasP and U=U messaging. U=U messaging campaigns and the empirical evidence supporting that approach have been received with mixed results, and there is variability in people’s perceptions and acceptability of TasP. The larger volume of literature on PrEP compared to TasP may likely be due to PrEP’s longer history and the very recent ramp-up of communication about TasP. However, TasP will suffer a similar fate as PrEP uptake if more is not done to increase TasP awareness and address HIV-related stigma.

Patient-Friendly Recap.

Preexposure prophylaxis medication (PrEP) and virus-suppressing treatments (TasP) are two proven means of preventing the spread of HIV from those who have the infection to sex partners who do not.

The authors analyzed findings from 24 published studies to determine the reasons why these prevention strategies might not be used by transgender women and men who have sex with men, or MSM.

HIV-related stigma, patient-provider distrust, and lack of awareness were major barriers to PrEP uptake in at-risk individuals. Widespread misunderstanding and skepticism about TasP is also likely to slow the global goal of reaching zero HIV transmissions in the near future.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

Study design: Matacotta. Data acquisition or analysis: all authors. Manuscript drafting: Matacotta, Carrillo. Critical revision: Matacotta, Rosales-Perez.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

References

- 1.Ocfemia MCB, Dunville R, Zhang T, Barrios LC, Oster AM. HIV diagnoses among persons aged 13–29 years – United States, 2010–2014. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67:212–5. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6707a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pérez-Figueroa RE, Kapadia F, Barton SC, Eddy JA, Halkitis PN. Acceptability of PrEP uptake among racially/ethnically diverse young men who have sex with men: the P18 study. AIDS Educ Prev. 2015;27:112–25. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2015.27.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mustanski B, Ryan DT, Remble TA, D’Aquila RT, Newcomb ME, Morgan E. Discordance of self-report and laboratory measures of HIV viral load among young men who have sex with men and transgender women in Chicago: implications for epidemiology, care, and prevention. AIDS Behav. 2018;22:2360–7. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2112-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rendina HJ, Parsons JT. Factors associated with perceived accuracy of the Undetectable = Untransmittable slogan among men who have sex with men: implications for messaging scale-up and implementation. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(1):e25055. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodger AJ, Cambiano V, Bruun T, et al. Risk of HIV transmission through condomless sex in serodifferent gay couples with the HIV-positive partner taking suppressive antiretroviral therapy (PARTNER): final results of a multicentre, prospective, observational study. Lancet. 2019;393:2428–38. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30418-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Young I, McDaid L. How acceptable are antiretrovirals for the prevention of sexually transmitted HIV? A review of research on the acceptability of oral pre-exposure prophylaxis and treatment as prevention. AIDS Behav. 2014;18:195–216. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0560-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siegel K, Meunier É. Awareness and perceived effectiveness of HIV treatment as prevention among men who have sex with men in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:1974–83. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02405-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.HIV.gov. HIV basics: US statistics. [Accessed April 3, 2019]. Last updated 2019 Mar 13. https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/overview/data-and-trends/statistics.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2015. [Accessed April 3, 2019]. Published 2016 Nov http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/library/reports/hiv-surveillance.html.

- 10.Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Bauermeister J, Smith H, Conway-Washington C. Minimal awareness and stalled uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among at risk, HIV-negative, black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:423–9. doi: 10.1089/apc.2014.0303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sevelius JM, Keatley J, Calma N, Arnold E. ‘I am not a man’: trans-specific barriers and facilitators to PrEP acceptability among transgender women. Glob Public Health. 2016;11:1060–75. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2016.1154085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wilson E, Chen YH, Pomart WA, Arayasirikul S. Awareness, interest, and HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis candidacy among young transwomen. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2016;30:147–50. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Golub SA. Enhancing PrEP access for black and Latino men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;73:547–55. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gupta S, Lounsbury DW, Patel VV. Low awareness and use of preexposure prophylaxis in a diverse online sample of men who have sex with men in New York City. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2017;28:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garnett M, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Franks J, Hayes-Larson E, El-Sadr WM, Mannheimer S. Limited awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York city. AIDS Care. 2018;30:9–17. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1363364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcus JL, Hurley LB, Dentoni-Lasofsky D, et al. Barriers to preexposure prophylaxis use among individuals with recently acquired HIV infection in Northern California. AIDS Care. 2019;31:536–44. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1533238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubach RD, Currin JM, Sanders CA, et al. Barriers to access and adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) in a relatively rural state. AIDS Educ Prev. 2017;29:315–29. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2017.29.4.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Parisi D, Warren B, Leung SJ, et al. A multicomponent approach to evaluating a pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) implementation program in five agencies in New York. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2018;29:10–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2017.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elopre L, McDavid C, Brown A, Shurbaji S, Mugavero MJ, Turan JM. Perceptions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among young, black men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32:511–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Rendina HJ, Surace A, Lelutiu-Weinberger CL. From efficacy to effectiveness: facilitators and barriers to PrEP acceptability and motivations for adherence among MSM and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27:248–54. doi: 10.1089/apc.2012.0419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cahill S, Taylor SW, Elsesser SA, Mena L, Hickson D, Mayer KH. Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2017;29:1351–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1300633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pawson M, Grov C. ‘It’s just an excuse to slut around’: gay and bisexual mens’ constructions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as a social problem. Sociol Health Illn. 2018;40:1391–403. doi: 10.1111/1467-9566.12765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holloway IW, Dougherty R, Gildner J, et al. Brief report: PrEP uptake, adherence, and discontinuation among California YMSM using geosocial networking applications. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;74:15–20. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marks SJ, Merchant RC, Clark MA, et al. Potential healthcare insurance and provider barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis utilization among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31:470–8. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rolle CP, Rosenberg ES, Siegler AJ, et al. Challenges in translating PrEP interest into uptake in an observational study of young black MSM. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2017;76:250–8. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang HL, Rhea SK, Hurt CB, et al. HIV preexposure prophylaxis implementation at local health departments: a statewide assessment of activities and barriers. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77:72–7. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jongbloed K, Parmar S, van der Kop M, Spittal PM, Lester RT. Recent evidence for emerging digital technologies to support global HIV engagement in care. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2015;12:451–61. doi: 10.1007/s11904-015-0291-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dowshen N, Binns HJ, Garofalo R. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:371–6. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Logie CH, Newman PA, Chakrapani V, Shunmugam M. Adapting the minority stress model: associations between gender non-conformity stigma, HIV-related stigma and depression among men who have sex with men in South India. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1261–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goldenberg T, Stephenson R, Bauermeister J. Community stigma, internalized homonegativity, enacted stigma, and HIV testing among young men who have sex with men. J Community Psychol. 2018;46:515–28. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Escudero DJ, Kerr T, Operario D, Socías ME, Sued O, Marshall BD. Inclusion of trans women in pre-exposure prophylaxis trials: a review. AIDS Care. 2015;27:637–41. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.986051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia J, Parker C, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Philbin M, Hirsch JS. Psychosocial implications of homophobia and HIV stigma in social support networks: insights for high-impact HIV prevention among black men who have sex with men. Health Educ Behav. 2016;43:217–25. doi: 10.1177/1090198115599398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Holloway IW, Tan D, Gildner JL, et al. Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis willingness among young men who have sex with men who use geosocial networking applications in California. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2017;31:517–27. doi: 10.1089/apc.2017.0082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitzel LD, Vanable PA, Carey MP. HIV-related stigmatization and medication adherence: indirect effects of disclosure concerns and depression. Stigma Health. 2019;4:282–92. doi: 10.1037/sah0000144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Price D, Finneran S, Allen A, Maksut J. Stigma and conspiracy beliefs related to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and interest in using PrEP among black and white men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1236–46. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1690-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parker S, Chan PA, Oldenburg CE, et al. Patient experiences of men who have sex with men using pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV infection. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:639–42. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Petroll AE, Walsh JL, Owczarzak JL, McAuliffe TL, Bogart LM, Kelly JA. PrEP awareness, familiarity, comfort, and prescribing experience among US primary care providers and HIV specialists. AIDS Behav. 2017;21:1256–67. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1625-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.LeVasseur MT, Goldstein ND, Tabb LP, Olivieri-Mui BL, Welles SL. The effect of PrEP on HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in the context of condom use, treatment as prevention, and seroadaptive practices. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;77:31–40. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Ghani MA, Nogg K, Winder TJ, Soto JK. Getting PrEPared for HIV prevention navigation: young black gay men talk about HIV prevention in the biomedical era. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2015;29:490–502. doi: 10.1089/apc.2015.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Goedel WC, King MRF, Lurie MN, Nunn AS, Chan PA, Marshall BDL. Effect of racial inequities in pre-exposure prophylaxis use on racial disparities in HIV incidence among men who have sex with men: a modeling study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2018;79:323–9. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zucker J, Patterson B, Ellman T, et al. Missed opportunities for engagement in the prevention continuum in a predominantly black and Latino community in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32:432–7. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]