ABSTRACT

Background

Snacking continues to be a major component in the dietary patterns of most Americans despite conflicting evidence surrounding snacking healthfulness. Low-sugar, highly nutritive snacks, such as hummus, can lead to improvements in diet quality, appetite, and glycemic control.

Objectives

The purpose of the study was to examine the effects of afternoon snacking on diet quality, appetite, and glycemic control in healthy adults.

Methods

Thirty-nine adults (age: 26 ± 1 y; BMI: 24.4 ± 0.5 kg/m2) randomly completed the following afternoon snack patterns for 6 d/pattern: hummus and pretzels [HUMMUS; 240 kcal; 6 g protein, 31 g carbohydrate (2 g sugar), 11 g fat]; granola bars [BARS; 240 kcal; 4 g protein, 38 g carbohydrate (16 g sugar), 9 g fat]; or no snacking (NO SNACK). On day 7 of each pattern, a standardized breakfast and lunch were provided. The respective snack was provided to participants 3 h after lunch, and appetite, satiety, and mood questionnaires were completed throughout the afternoon. At 3 h postsnack, a standardized dinner was consumed, and an evening snack cooler was provided to be consumed, ad libitum at home, throughout the evening. Lastly, 24 h continuous glucose monitoring was performed.

Results

HUMMUS reduced subsequent snacking on desserts by ∼20% compared with NO SNACK (P = 0.001) and BARS (P < 0.001). HUMMUS led to greater dietary compensation compared with BARS (122 ± 31% compared with 72 ± 32%, respectively; P < 0.05). HUMMUS reduced indices of appetite (i.e., hunger, desire to eat, and prospective food consumption) by ∼70% compared with NO SNACK (all P < 0.05), whereas BARS did not. Additionally, satiety was ∼30% greater following HUMMUS and BARS compared with NO SNACK (both P < 0.005) with no differences between snacks. Lastly, HUMMUS reduced afternoon blood glucose concentrations by ∼5% compared with BARS (P < 0.05).

Conclusions

Acute consumption of a low-sugar, afternoon hummus snack improved diet quality and selected indices of appetite, satiety, and glycemic control in healthy adults. Long-term trials assessing the effects of hummus snacking on health outcomes are warranted.

Keywords: hummus, legumes, snacks, satiety, diet quality

Introduction

Snacking remains a major component in the dietary patterns of most Americans despite the ongoing controversy as to whether eating between and/or replacing meals with smaller eating occasions is a “healthful” habit. Whereas snacking can contribute to detrimental weight gain by promoting the consumption of empty calories, recent evidence supports the role of nutrient-dense snacking to promote health (1).

There are several snacking strategies that improve indices of weight management. Specifically, increased appetite control, increased satiety, and reduced unhealthy snacking have been reported with the consumption of higher-protein snacks (2–7), higher-fiber snacks (see review in reference 8); and those that have a lower glycemic index (9). Another important aspect of health includes the ability to improve and/or maintain glucose control throughout the day. Although limited, 1 study reported improvements in postprandial glycemic control with a snack that had a lower glycemic index (9). Collectively, further work is needed to explore the effects of commonly consumed snacks on these health outcomes.

The consumption of hummus has increased in the United States and globally over the past few years (10). Due to the low glycemic index properties (11), high nutritive value (11), and palatability of hummus, it is plausible that the inclusion of this food into an afternoon snack might result in improvements in diet quality, ingestive behavior, and glycemic control.

Thus, the purpose of this study was to determine whether a lower-sugar afternoon hummus snack compared with a common higher-sugar snack improves diet quality, appetite, satiety, and glycemic control compared with no snacking in healthy adults.

Methods

Study participants

From May 2018 to May 2019, adult males and females were recruited from the greater Lafayette, Indiana, area through advertisements, flyers, and e-mail listservs to participate in the study. Eligibility was determined through the following inclusion criteria: 1) age range 18–50 y; 2) normal to obese (BMI: 18–32 kg/m2); 3) no metabolic, psychological, or neurological diseases/conditions; 4) not currently or previously on a weight-loss or other special diet (in the past 6 mo); 5) nonsmoking; 6) not clinically diagnosed with an eating disorder; 7) habitually eats (i.e., ≥4 times/wk) an afternoon snack between 14:00 and 16:00; 8) no food allergies related to the study snacks; 9) no overnight shift work schedules; 10) rates the palatability (i.e., overall liking) of hummus greater than “neither like nor dislike” on the screening palatability questionnaire; and 11) reviewed the study evening snack cooler and rated it as “acceptable.”

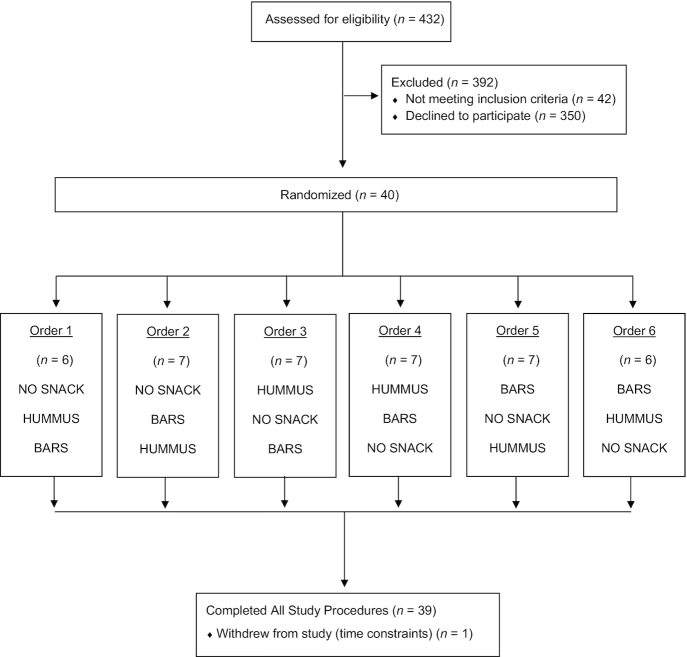

Initially, 432 adults were interested in participating in the study; 40 met the screening criteria, passed the snack palatability test, and began the study, and 39 completed all study procedures (May 2019; Figure 1). The 1 participant who did not complete the study withdrew because of time constraints.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram. BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

Participant characteristics of those who completed the study are presented in Table 1. In general, the participants were healthy, normal-to-obese adults. All participants were informed of the study purpose, procedures, and risks. All participants signed the consent form. All procedures were followed in accordance with the ethical standards of the Institutional Review Board. The participants received a total of $150 ($50/treatment) for completing all study procedures. The study was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT03595462).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of participants who completed the study1

| Sex (men:women), n | 14:25 |

| Age, y | 26 ± 1 |

| Height, cm | 170 ± 2 |

| Weight, kg | 68.5 ± 2.2 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 24.4 ± 0.5 |

| Afternoon snacking occasions, n/wk | 5 ± 1 |

Values are mean ± SEM, n = 39.

Experimental design

Thirty-nine healthy adults participated in the following randomized crossover-design study. The participants were acclimated to the respective afternoon snack patterns, at home, for 6 d in randomized order: 1) hummus and pretzel (HUMMUS), 2) granola bars (BARS), or 3) no snack (NO SNACK). The NO SNACK treatment served as a negative control because no snacks were provided, whereas the BARS served as a positive control because the participants were habitual afternoon snackers on high-sugar snacks. On the third day of each treatment, a continuous glucose monitor (CGM) was inserted and free-living glycemic control was assessed over the following 5 d.

On the seventh day of each pattern, the participants consumed a standardized breakfast and reported to the testing facility 15 min prior to their habitual lunch time to complete the respective 6 h testing day. The participants were placed in a comfortable room, void of all time cues, and remained there throughout the day. The participants began the testing day by completing a prelunch appetite, satiety, and mood questionnaire before consuming a standardized lunch. When lunch was finished, participants completed presnack appetite, satiety, and mood assessments. At 3 h postlunch, the respective snack was provided to the participant and consumed within 20 min. Snack palatability was assessed. Appetite, satiety, and mood questionnaires were measured for the remainder of the day until a standardized dinner was provided 3 h postsnack. In addition to these assessments, the participants also reported when they wanted to eat again (i.e., eating initiation) to denote actual satiety. After dinner, the participants were provided with a snack cooler, left the facility, and were permitted to snack, ad libitum, until going to bed that evening. On the following day, the participants returned the snack cooler and had the CGM removed. There was ∼7 d between each testing day.

Study snacks

The dietary characteristics of the snacks are shown in Table 2. Each snack was ∼240 kcal. The HUMMUS snack composition was 10% of energy as protein, 50% of energy as carbohydrate (6% of which was sugar), and 40% energy as fat, whereas the BARS comprised 6% of energy as protein, 61% of energy as carbohydrate (42% of which was sugar), and 33% energy as fat.

TABLE 2.

Snack characteristics and palatability of NO SNACK, BARS, and HUMMUS snack patterns1

| NO SNACK | BARS | HUMMUS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Snack mass, g | 0 | 54 | 83 |

| Energy content, kcal | 0 | 240 | 240 |

| Energy density, kcal/g | 0 | 4.44 | 2.89 |

| Protein, g | 0 | 4 | 6 |

| Carbohydrate, g | 0 | 38 | 31 |

| Sugar, g | 0 | 16 | 2 |

| Fiber, g | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Fat, g | 0 | 9 | 11 |

| Palatability,2 mm | N/A | 76 ± 3 | 85 ± 1* |

1BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

2Palatability assessed from the 100-mm visual analog scale; Values are means ± SEMs, n = 39. *Different from BARS, P = 0.01.

The sensory properties [i.e., appearance, aroma, flavor, texture, and overall liking (palatability)] of each snack were assessed after the first bite of each snack during the testing days. A paper visual analog scale questionnaire incorporating a 100-mm horizontal line rating scale was used. The questions were worded as, “How strong is the...,” with anchors of “not at all” to “extremely.” Palatability is reported in Table 2 and was higher within the HUMMUS snack vs. BARS, P<0.05.

The HUMMUS snack contained 2 servings (i.e., 4 tablespoons, 57 g) of roasted red pepper hummus (Sabra Dipping Company, LLC); 1 serving of original pretzel crisps (10 pretzel crisps, 28 g; Snack Factory); and 8 oz (237 mL) water. The BARS consisted of 2 servings of granola bars (2 bars, 54 g) of chewy oats and honey granola bars (Sunbelt Bakery) and 8 oz (237 mL) water. The NO SNACK contained only the 8 oz (237 mL)water.

Specific procedures

Dietary intake and diet quality

To standardize the type and quantity of the breakfast foods consumed prior to the start of the day 7 testing days, the participants were provided with specific breakfast foods (i.e., quesadillas and pineapple bits) to consume ad libitum. The respective quantity was then provided to each participant to be consumed between 07:00 and 09:00 on the morning of each testing day. On average, breakfast contained 410 ± 25 kcal (17% of energy as protein, 61% of energy as carbohydrate, and 22% of energy as fat).

The participants were also provided with specific lunch and dinner foods during the testing days. The lunch meal was standardized across all participants and consisted of a personal pizza and crème de menthe thin mints. The lunch meal was 440 kcal (18% of energy as protein, 41% of energy as carbohydrate, and 41% of energy as fat). The dinner meal consisted of 1 of 4 frozen options for the participants to choose from: beef teriyaki, four-cheese ravioli and chicken marinara, kung pao chicken, and tortellini primavera. On average, dinner contained 275 ± 5 kcal (23% of energy as protein, 57% of energy as carbohydrate, 20% of energy as fat).

The ad libitum evening snack cooler, provided after dinner to be consumed at home, consisted of a variety of commonly consumed snack foods and contained a total of ∼5500 kcal. There were 11 different snacks, including brownie bites, chocolate chip cookie dough ice cream, fruit-flavored sugary candy, peanut butter cups, potato chips, pretzels, beef jerky, almonds, hummus, apples, and carrots. All snack foods included within the ad libitum evening snack cooler were weighed before the packout and any remaining items were reweighed upon return to determine energy and macronutrient content as well as snack type and quantity of foods consumed. This approach was used in our previous breakfast and snack studies with excellent compliance (2, 12).

Appetite, satiety, and mood questionnaires

Validated computerized questionnaires assessing perceived appetite sensations (i.e., hunger, fullness, desire to eat, prospective food consumption) and mood and energy states (i.e., sleepy, energetic, alert) were completed every hour before the snack and every 30 min after the snack throughout each of the testing days (13). The questionnaires contained visual analog scales incorporating 100-mm horizontal-line rating scales for each response. The questions were worded as, “How strong is the...,” with anchors of “not at all” to “extremely.” The Adaptive Visual Analog Scale software (Neurobehavioral Research Laboratory and Clinic; San Antonio, TX) was used for data collection. In addition, the participants were also asked whether they would like to request to eat (again) as another marker of eating initiation and satiety. When the response was “Yes, I want to eat right now,” the time from snack was recorded.

Continuous glucose monitoring

Free-living glucose measures were performed for 4 consecutive days using a CGM (iPRO; Medtronic). On approximately day 3 of each pattern, the participants reported to our facility for CGM insertion. A small area on the participant's abdomen was cleaned and a tiny glucose sensor was inserted just under the skin and held in place with Tegaderm tape (3M). The iPRO sensor measures glucose every 10 s and records a mean glucose value every 5 min for up to 144 h. Calibration was performed by 4 finger sticks/d with a glucose analyzer. The participants wore the CGM until day 8 of each pattern.

Data and statistical analyses

The difference between treatment groups in afternoon hunger, fullness, and eating initiation from our previous snack study (effect sizes: 1.37, 1.38, and 2.00, respectively) indicated that a sample size of n = 32 would provide 80% power to detect differences in all primary outcomes in the current study (3). An estimated dropout rate was initially set at 20% to establish the study sample size of n = 40. Thus, the final sample size of n = 39 was more than adequate to detect differences in study outcomes.

Summary statistics (sample means and sample SDs) were computed for all data. Values for net incremental AUC across the day and across the 3 h postsnack period were calculated from the postprandial time points for the appetite, satiety, and mood and energy outcomes. Percentage dietary compensation was calculated as followed:

|

(1) |

Thus, a score of 100% equals perfect compensation of the snack. A score <100% indicates undercompensation (or overeating), whereas a score >100% indicates overcompensation (or undereating). The CGM data from day 7 (i.e., testing day) were divided into the following time intervals: 18 h (upon waking to bedtime), afternoon snack period (3 h postsnack), and afternoon snack and evening period (8 h postsnack). Within the different time intervals, net incremental AUC, mean, and variability (defined as the mean of the SDs across the 18 h) were calculated. Daily intake, dietary compensation, evening snacking energy and macronutrient content were determined. In addition, intake was broken into food categories of interest [i.e., vegetables, high-fat (>5 g fat/serving), and high-sugar snacks (>10% kcal)]. Repeated-measures ANOVA examining the main effects of treatment was applied for all outcomes. When main effects were detected, post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed using Fisher least significant differences. Additionally, a paired t test was performed on test-day palatability of BARS compared with HUMMUS.

Data are reported as means ± SEMs. Analyses were conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS version 21.0; IBM). A value of P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Dietary intake and diet quality

Energy content provided at all standardized meals as well as during the ad libitum snacking assessment is shown in Table 3. No differences in daily energy content were observed between the snack patterns; however, the HUMMUS snack led to greater compensation (of the snack) by reducing intake to a greater extent compared with BARS (P = 0.05). In addition, a main effect of snack pattern was observed for ad libitum evening snacking (P < 0.001). Both the HUMMUS and BARS snacks led to fewer calories consumed in the evening compared with NO SNACK (both P < 0.05). However, no difference in evening energy content from snacking was observed for HUMMUS compared with BARS.

TABLE 3.

Energy intake throughout the testing days following the NO SNACK, BARS, and HUMMUS snack patterns in healthy adults1

| NO SNACK | BARS | HUMMUS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standardized meal energy intakes, kcal | |||

| Breakfast | 405 ± 25 | 410 ± 25 | 415 ± 25 |

| Lunch | 440 ± 0 | 440 ± 0 | 440 ± 0 |

| Afternoon snack | 0 ± 0 | 240 ± 0 | 240 ± 0 |

| Dinner | 270 ± 0 | 270 ± 0 | 270 ± 0 |

| Ad libitum evening snack energy intake, kcal | 1400 ± 120a | 1220 ± 125b | 1110 ± 120b |

| Total daily energy intake, kcal | 2540 ± 135 | 2610 ± 140 | 2490 ± 130 |

| Dietary compensation, % | N/A | 71.7 ± 32.0a | 122.4 ± 31.1b |

¹Values are means ± SEMs, n = 39. Labeled means in a row without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

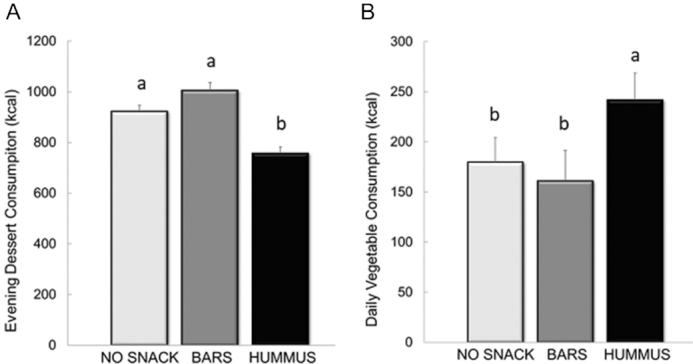

When the evening snack foods were allocated into food categories, a main effect of snack pattern was detected for high-sugar (dessert) snacks (P < 0.001) (Figure 2A). Specifically, only the HUMMUS snack reduced subsequent snacking on high-sugar desserts compared with NO SNACK (P = 0.001), whereas the BARS did not. Further, the HUMMUS led to lower high-sugar dessert consumption compared with BARS (P < 0.001). The HUMMUS pattern also increased daily vegetable consumption compared with NO SNACK and compared with the BARS (P < 0.001) (Figure 2B). No differences were observed between the NO SNACK and the BARS.

FIGURE 2.

Energy intake from evening snack consumption of high-sugar (dessert) foods (A) and daily snack consumption of vegetables (B) following the NO SNACK, BARS, and HUMMUS snack patterns in healthy adults. Values are means ± SEM, n = 39. Different letters denote significance, post hoc pairwise comparisons, P < 0.05. BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

Appetite and satiety

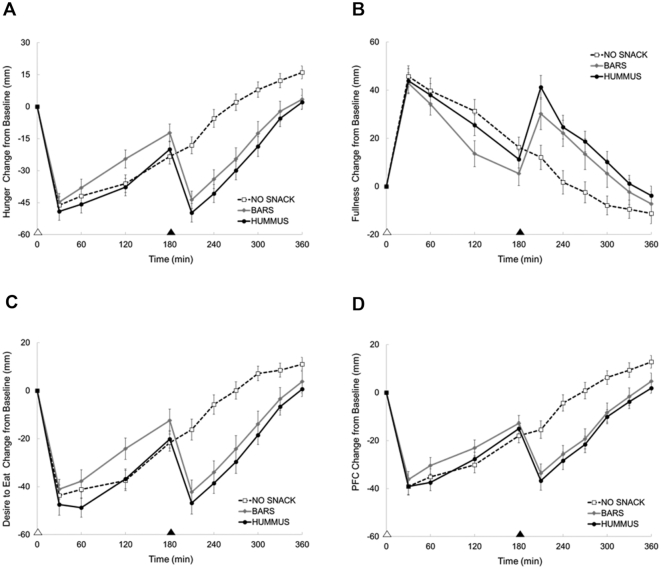

Figure 3A–D depicts the appetite and satiety responses throughout the testing day following each of the study snacking periods.

FIGURE 3.

Perceived hunger (A), fullness (B), desire to eat (C), and prospective food consumption (PFC) (D) responses across the day following each snack pattern in healthy adults. Appetite questionnaires using 100-mm visual analog scales were used; Values are means ± SEM, n = 39. White triangle denotes lunch; black triangle denotes snack. BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

Main effects of snack pattern were observed for daily and postsnack hunger responses (both P < 0.005). The HUMMUS snack led to greater reductions in daily hunger (−11,000 ± 1170 mm•360min) compared with NO SNACK (−6300 ± 1100 mm•360min; P < 0.005) and BARS (−8540 ± 1340 mm•360min; P = 0.05), whereas the BARS were not different compared with NO SNACK. In the postsnack period, both the HUMMUS and BARS reduced hunger compared with NO SNACK (P < 0.005). No differences in postsnack hunger were observed between the BARS and HUMMUS.

No difference in daily fullness responses were observed between snack patterns (NO SNACK: 5410 ± 1360 mm•360min; BARS: 5840 ± 1690 mm•360min; HUMMUS: 7990 ± 1150 mm•360min). However, an overall main effect was observed for postsnack fullness (P < 0.005). Both the HUMMUS and BARS led to greater increases in postsnack fullness compared with NO SNACK (both P < 0.005). No differences in postsnack fullness were observed between the BARS and HUMMUS.

Main effects of snack pattern were observed for daily and postsnack desire to eat (both P < 0.03). The HUMMUS snack led to greater reductions in daily desire to eat (−10,900 ± 1140 mm•360min) compared with NO SNACK (−6400 ± 1060 mm•360min; P < 0.005), whereas the BARS were not different (−8420 ± 1440 mm•360min) compared with NO SNACK. Further, the HUMMUS snack tended to reduce daily desire to eat compared with BARS ( P = 0.07). During the postsnack period, both the HUMMUS and BARS led to greater reductions in desire to eat compared with NO SNACK (both P < 0.005), with no differences between BARS compared with HUMMUS.

Main effects of snack pattern were observed for daily and postsnack prospective food consumption (both P < 0.03). The HUMMUS snack led to greater reductions in daily prospective food consumption (−8190 ± 867 mm•360min) compared with NO SNACK (−5280 ± 935 mm•360min; P = 0.01), whereas the BARS were not different (−7010 ± 1050 mm•360min) compared with NO SNACK. No differences were observed between the BARS compared with HUMMUS. During the postsnack period, both the HUMMUS and BARS led to greater reductions in prospective food consumption compared with NO SNACK (both P < 0.005), with no differences between the BARS compared with HUMMUS.

Eating initiation (satiety)

Participants voluntarily requested to eat again at ∼1 h (i.e., 50 ± 7 min) after their respective habitual snack time during the NO SNACK pattern and ∼2 h after the HUMMUS (i.e., 124 ± 10 min) and BARS (136 ± 9 min). A main effect of snack pattern was detected for this outcome (P < 0.005). The consumption of the BARS and HUMMUS snacks delayed the request to eat again compared with NO SNACK (P < 0.005) with no differences observed between the BARS and HUMMUS.

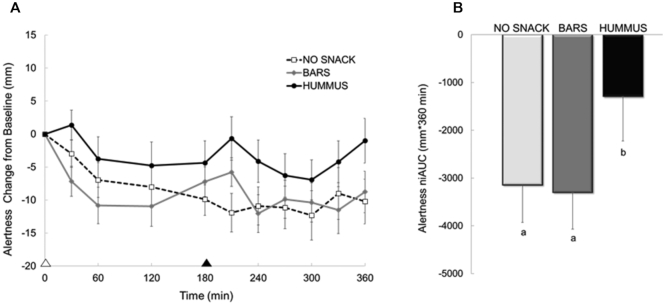

Mood

Figure 4 depicts the feelings of alertness following each snack pattern. The line graph (Figure 4A) illustrates the time course throughout the day and the bar graph (Figure 4B) represents the 6 h AUC assessment. A main effect of snack pattern was observed for daily and postsnack alertness (both P < 0.005). The HUMMUS snack led to smaller declines in daily and postsnack alertness compared with NO SNACK (P < 0.001) and BARS (P < 0.001), whereas the BARS were not different compared with NO SNACK. No other differences in any other indices of mood (i.e., perceived energy or sleepiness) were detected between snack patterns (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

Perceived alertness across the day following each snack pattern in healthy adults. Panel A depicts the time course, whereas Panel B depicts the 360-min net incremental area under the curve (niAUC). Alertness assessed using a 100-mm visual analog scale; Values are means ± SEM, n = 39. White triangle denotes lunch; black triangle denotes snack. Different letters denote significance, post hoc pairwise comparisons, P < 0.05. BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

Glycemic control

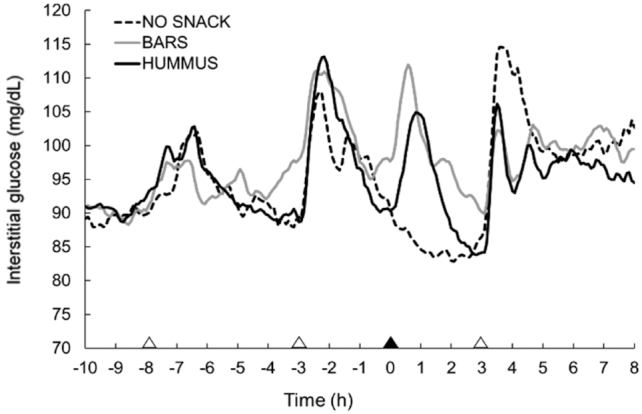

The glucose responses of the participants on the testing day of each snack pattern are illustrated in Figure 5. From the figure, postprandial rises and declines in interstitial glucose are observed following the standardized meals and respective snacks.

FIGURE 5.

Glucose responses across the day following each snack pattern in healthy adults. White triangles denote meals; black triangle denotes snack. Values are means ± SEM, n = 39. BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

No significant difference in daily responses were observed between treatments (Table 4). A main effect of snack pattern was observed for 3-h postsnack blood glucose mean (P < 0.005), AUC (P < 0.005), and variability (P < 0.005). Specifically, the BARS and HUMMUS led to greater 3-h postsnack blood glucose mean, AUC, and variability compared with NO SNACK (all P < 0.05). The HUMMUS snack resulted in lower postsnack blood glucose mean, AUC, and variability compared with BARS (both P < 0.05). Lastly, when comparing the evening responses following the respective snack pattern, a main effect was detected for evening glucose variability only (P < 0.05), with both the BARS and HUMMUS eliciting lower variability compared with NO SNACK (both P < 0.05).

TABLE 4.

Glucose responses throughout the testing days following the NO SNACK, BARS, and HUMMUS snack patterns in healthy adults1

| NO SNACK | BARS | HUMMUS | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily glucose responses | |||

| AUC, mg/dL•18 h | 103,000 ± 2670a | 106,000 ± 1180a | 103,000 ± 1950a |

| Mean concentrations, mg/dL | 94.7 ± 2.4a | 97.5 ± 1.1a | 95.1 ± 1.8a |

| Variability ± SD2 | 12.7 ± 2.8a | 10.9 ± 2.4a | 11.7 ± 2.5a |

| Postsnack glucose responses | |||

| AUC, mg/dL•3 h | 15,300 ± 476a | 17,800 ± 299b | 16,800 ± 355c |

| Mean concentrations, mg/dL | 85.2 ± 2.6a | 98.9 ± 1.6b | 93.0 ± 1.9c |

| Variability ± SD2 | 4.2 ± 0.5a | 10.2 ± 1.0b | 9.3 ± 1.5c |

| Evening snack glucose responses | |||

| AUC, mg/dL•8 h | 45,400 ± 1390a | 47,100 ± 693a | 45,300 ± 816a |

| Mean concentrations, mg/dL | 95.6 ± 2.9a | 99.3 ± 1.4a | 95.3 ± 1.7a |

| Variability ± SD2 | 13.2 ± 1.4a | 10.1 ± 0.8b | 10.1 ± 1.1b |

¹Values are means ± SEMs unless indicated otherwise; n = 39. Labeled means in a row without a common letter differ, P < 0.05. BARS, granola bars; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

The mean of the SDs across the data is calculated to determine glucose variability.

Discussion

The acute consumption of a lower-sugar, afternoon hummus snack improved diet quality through reductions in high-sugar desserts and increases in vegetable consumption compared with a higher-sugar afternoon snack and/or no afternoon snack. Additionally, hummus snacking led to improvements in selected indices of appetite, satiety, mood, and glycemic control compared with higher-sugar snacking and/or no afternoon snacking. These data suggest that the daily consumption of a low-sugar snack containing hummus might be a potential strategy to improve diet quality and selected health outcomes in adults.

Over the past few decades, between-meal snacking has become increasingly popular. Frequency of snacking has increased from 1 snack/d to 2.2 snacks/d in the last 4 decades (14, 15), and snacks are now responsible for about 24% of daily energy intake in US adults (14). Although increased snacking often results in an increase in eating frequency throughout the day, it does not always increase daily energy intake if it is compensated for by decreased portion sizes in subsequent eating occasions (16). However, many popular snacks are energy dense, contain “empty calories,” and elicit weak postprandial satiety (2, 17–19). Thus, increased snacking frequency can result in excess daily energy intake (17, 18). In the current study, regardless of snack quality, the addition of an ingestive event in the form of an afternoon snack did not increase daily caloric intake. However, better dietary compensation observed following the HUMMUS snack compared with the BARS suggests that the type of snack consumed influences subsequent energy intake.

High-glycemic foods are digested and absorbed quickly and can promote overeating (20). Alternately, low-glycemic foods, like hummus, are digested and absorbed more slowly and can promote weight management through increased satiety and subsequent reductions in food intake (21, 22).

Traditional hummus is a creamy dip prepared by mixing cooked, mashed chickpeas with other ingredients such as tahini, olive oil, garlic, lemon juice, and various spices (23). Legumes such as the chickpeas found in hummus are low glycemic, with a mean glycemic index score of 28 ± 9/100 on the glucose reference scale, which has a maximum score of 100 (21). Besides being low glycemic, chickpeas and other legumes are also high in fiber and have a high ratio of slowly digestible starch to readily digestibly starch (24). Legume consumption provides several health benefits, including increased satiety, improved body weight, and prevention of diseases such as type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease (23).

Most studies that have investigated appetite and satiety following legume consumption are short-term, single-bolus feeding trials. In these studies, legume consumption within a meal appears to reduce postprandial hunger and increase satiety but has little to no effect on second meal intake when compared with energy-controlled comparison foods such as white bread or cereal grains (25, 26). In a long-term study by Murty et al. (27), legume consumption and satiation were assessed before and after 12 wk of chickpea supplementation (104 g/d). The addition of chickpeas into the habitual diet resulted in higher satiation ratings compared with habitual diets in healthy adults. The findings from this study are in line with the current body of evidence supporting the consumption of legumes, as hummus, for improved appetite control and satiety (26, 27).

In addition to the improvements in appetite and satiety, short-term studies report that the consumption of beans, chickpeas, and other legumes reduces postprandial glucose elevation compared with other carbohydrate foods (28). Further, a meta-analysis found that consuming legumes daily for >4 wk results in significantly lower fasting blood glucose and insulin (29). However, much less research has been conducted on hummus and its effect on glycemic response. One previous study illustrated lower postprandial blood glucose concentrations in the hour after hummus consumption compared with white bread consumption (11). Similarly, the present study found that the HUMMUS snack improved the afternoon glycemic response when compared with a higher-sugar BARS snack. This is an especially important consideration for people who struggle with glycemic control, such as type 2 diabetics. Previous studies have found that legume consumption improves glycemic control in diabetics (29, 30), which indicates that hummus might present a healthy, risk-reducing snack option for these individuals.

Limitations

Although this study included a tightly controlled feeding design, it was an acute trial and thus cannot determine potential improvements in long-term health outcomes. For instance, the HUMMUS snack led to fewer calories consumed as high-sugar evening dessert snacks, greater calories from vegetables, and reduced glucose concentrations throughout the afternoon. However, it is unclear whether the acute changes might lead to improvements in diet quality and glycemic control over the long term.

Second, the study intervention snacks varied in a number of factors that impact appetite and subsequent food intake (31–34). For example, the HUMMUS snack contained fewer carbohydrates and less sugar compared with the BARS. The HUMMUS snack was larger in terms of volume, lower in energy density, and higher in palatability ratings compared with the BARS. We acknowledge that this is a food comparison study, making it challenging to identify the primary mechanism of action. However, this study highlights the unique nutritive, physical, and sensory profile of HUMMUS that collectively improves health-related outcomes.

Lastly, because the HUMMUS snack included hummus and pretzels, we were unable to isolate the effects of hummus (or even legumes) on the outcomes of interest. We chose this approach for several reasons. First, we wanted to perform an isocaloric comparison between a low and a higher glycemic index snack. To match the energy in our comparator (i.e., granola bars) with hummus alone would have required a larger quantity of hummus than the standard snack serving size. Along these lines, the inclusion of vegetables with hummus would have required a fairly large quantity of vegetables. Both approaches would have limited the palatability of the HUMMUS treatment and potentially reduced compliance. Given the cultural preferences in the United States (to eat hummus with other snack foods such as pretzels or pita chips), we felt that the inclusion of pretzels with hummus was more appropriate from a consumption perspective. Further, the inclusion of pretzels allowed us to closely match the glycemic index of the vehicle food in the HUMMUS snack with that of granola bars in the BARS snack (20), which to a certain extent enabled us to isolate the effects of hummus within the overall snack. Thus, future research specifically isolating the effects of hummus is needed.

Conclusions

These data suggest that the daily consumption of a low-sugar afternoon hummus snack might be an important dietary strategy to improve diet quality, selected indices of appetite and satiety, and glycemic control. Long-term trials assessing the effects of hummus snacking on health outcomes are warranted.

Acknowledgments

The authors’ responsibilities were as follows—EJR and HJL: designed the research; EJR: conducted research; EJR and HJL: analyzed the data; EJR: wrote the first draft of the paper; EJR and HJL: reviewed and edited the draft; and both authors: read and approved the final manuscript.

Notes

This study was supported by the Sabra Dipping Company, LLC

Author disclosures: HJL is a member of the scientific advisory board for Sabra Dipping Company. EJR reports no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations used: BARS, granola bars snack; CGM, continuous glucose monitor; HUMMUS, hummus and pretzels snack; NO SNACK, no afternoon snack.

References

- 1. Bellisle F. Meals and snacking, diet quality and energy balance. Physiol Behav. 2014;134:38–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leidy HJ, Todd CB, Zino AZ, Immel JE, Mukherjea R, Shafer RS, Ortinau LC, Braun M. Consuming high-protein soy snacks affects appetite control, satiety, and diet quality in young people and influences select aspects of mood and cognition. J Nutr. 2015;145:1614–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Douglas SM, Ortinau LC, Hoertel HA, Leidy HJ. Low, moderate, or high protein yogurt snacks on appetite control and subsequent eating in healthy women. Appetite. 2013;60:117–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Marmonier C, Chapelot D, Louis-Sylvestre J. Effects of macronutrient content and energy density of snacks consumed in a satiety state on the onset of the next meal. Appetite. 2000;34:161–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Poppitt SD, Proctor J, McGill A-T, Wiessing KR, Falk S, Xin L, Budgett SC, Darragh A, Hall RS. Low-dose whey protein-enriched water beverages alter satiety in a study of overweight women. Appetite. 2011;56:456–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Potier M, Fromentin G, Calvez J, Benamouzig R, Martin-Rouas C, Pichon L, Tomé D, Marsset-Baglieri A. A high-protein, moderate-energy, regular cheesy snack is energetically compensated in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2009;102:625–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Johnstone AM, Shannon E, Whybrow S, Reid CA, Stubbs RJ. Altering the temporal distribution of energy intake with isoenergetically dense foods given as snacks does not affect total daily energy intake in normal-weight men. Br J Nutr. 2000;83:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Njike VY, Smith TM, Shuval O, Shuval K, Edshteyn I, Kalantari V, Yaroch AL. Snack food, satiety, and weight. Adv Nutr. 2016;7:866–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Papakonstantinou E, Orfanakos N, Farajian P, Kapetanakou AE, Makariti IP, Grivokostopoulos N, Ha M-A, Skandamis PN. Short-term effects of a low glycemic index carob-containing snack on energy intake, satiety, and glycemic response in normal-weight, healthy adults: results from two randomized trials. Nutrition. 2017;42:12–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Sawant A. Hummus market top companies strategy, value analysis, gross margin, sales, global production and consumption by forecast to 2027. [Internet] 2019. [Last accessed 2020 May 5]. Available from, https://www.abnewswire.com/pressreleases/hummus-market-top-companies-strategy-value-analysis-gross-margin-sales-global-production-and-consumption-by-forecast-to-2027_428095.html [Google Scholar]

- 11. Augustin LSA, Chiavaroli L, Campbell J, Ezatagha A, Jenkins AL, Esfahani A, Kendall CWC. Post-prandial glucose and insulin responses of hummus alone or combined with a carbohydrate food: a dose–response study. Nutr J. 2015;15:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leidy HJ, Ortinau LC, Douglas SM, Hoertel HA. Beneficial effects of a higher-protein breakfast on the appetitive, hormonal, and neural signals controlling energy intake regulation in overweight/obese, “breakfast-skipping,” late-adolescent girls. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:677–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Flint A, Raben A, Blundell JE, Astrup A. Reproducibility, power and validity of visual analogue scales in assessment of appetite sensations in single test meal studies. Int J Obes. 2000;24:38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Piernas C, Popkin BM. Snacking increased among U.S. adults between 1977 and 2006. J Nutr. 2009;140:325–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sebastian RS, Wilkinson Enns C, Goldman JD. Snacking patterns of US adults. What We Eat in America, NHANES 2007–2008. [Internet]. USDA Agricultural Research Service Food Surveys Research Group Dietary Data Brief no. 4;2011. [Last accessed 2020 May 5]. Available from: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/80400530/pdf/DBrief/4_adult_snacking_0708.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Mattes RD. Snacking: a cause for concern. Physiol Behav. 2018;193:279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Forslund HB, Torgerson JS, Sjöström L, Lindroos AK. Snacking frequency in relation to energy intake and food choices in obese men and women compared to a reference population. Int J Obes. 2005;29:711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhu Y, Hollis JH. Associations between eating frequency and energy intake, energy density, diet quality and body weight status in adults from the USA. Br J Nutr. 2016;115:2138–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ortinau LC, Hoertel HA, Leidy HJ. Effects of high-protein vs. high-fat snacks on appetite control, satiety, and eating initiation in healthy women. Nutr J. 2014;13:97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ludwig DS. The glycemic index: physiological mechanisms relating to obesity, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. JAMA. 2002;287:2414–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Atkinson FS, Foster-Powell K, Brand-Miller JC. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2281–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brand-Miller JC, Holt SHA, Pawlak DB, McMillan J. Glycemic index and obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:281S–5S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wallace TC, Murray R, Zelman KM. The nutritional value and health benefits of chickpeas and hummus. Nutrients. 2016;8:766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Thorne MJ, Thompson LU, Jenkins DJ. Factors affecting starch digestibility and the glycemic response with special reference to legumes. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983;38:481–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. McCrory MA, Hamaker BR, Lovejoy JC, Eichelsdoerfer PE. Pulse consumption, satiety, and weight management. Adv Nutr. 2010;1:17–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Li SS, Kendall CWC, de Souza RJ, Jayalath VH, Cozma AI, Ha V, Mirrahimi A, Chiavaroli L, Augustin LSA, Blanco Mejia S. Dietary pulses, satiety and food intake: a systematic review and meta‐analysis of acute feeding trials. Obesity. 2014;22:1773–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Murty CM, Pittaway JK, Ball MJ. Chickpea supplementation in an Australian diet affects food choice, satiety and bowel health. Appetite. 2010;54:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hutchins AM, Winham DM, Thompson SV. Phaseolus beans: impact on glycaemic response and chronic disease risk in human subjects. Br J Nutr. 2012;108:S52–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Sievenpiper JL, Kendall CWC, Esfahani A, Wong JMW, Carleton AJ, Jiang HY, Bazinet RP, Vidgen E, Jenkins DJA. Effect of non-oil-seed pulses on glycaemic control: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled experimental trials in people with and without diabetes. Diabetologia. 2009;52(8):1479–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jenkins DJA, Kendall CWC, Augustin LSA, Mitchell S, Sahye-Pudaruth S, Mejia SB, Chiavaroli L, Mirrahimi A, Ireland C, Bashyam B. Effect of legumes as part of a low glycemic index diet on glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1653–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Leidy HJ, Clifton PM, Astrup A, Wycherley TP, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Luscombe-Marsh ND, Woods SC, Mattes RD. The role of protein in weight loss and maintenance. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1320s–9s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johnson F, Wardle J. Variety, palatability, and obesity. Adv Nutr. 2014;5(6):851–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Gray R, French S, Robinson T, Yeomans M. Dissociation of the effects of preload volume and energy content on subjective appetite and food intake. Physiol Behav. 2002;76(1):57–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rouhani MH, Surkan PJ, Azadbakht L. The effect of preload/meal energy density on energy intake in a subsequent meal: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eat Behav. 2017;26:6–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]