Abstract

Background:

Diet therapies may be recommended for pediatric functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs). However, little is known about the frequency with which diet therapy is recommended in these group of patients. The aims of the study were to determine and contrast the frequency and types of diet recommendations provided to children with FGIDs by pediatric gastroenterologists (PGI) compared to primary care pediatricians (PCP).

Methods:

A retrospective chart review was performed using data from a large metropolitan children’s academic healthcare system to identify subjects meeting Rome IV criteria for functional abdominal pain, functional dyspepsia, irritable bowel syndrome and/or abdominal migraine over a period of 23 months.

Results:

Of 1929 patient charts reviewed, 268 had a Rome IV diagnosis and were included for further analyses. Of these, 186 patients (69%) were seen by PGI and 82 (31%) by PCP. The most common diagnosis was irritable bowel syndrome (49% for PGI and 71% for PCP). Diet recommendations were provided to 115 (43%) patients (PGI group: 86 (75%) vs. PCP group: 29 (25%); P<0.1. The most frequent recommendations were high fiber (PGI: 15%; PCP: 14%) and low FODMAP diet (PGI: 12%; PCP: 4%). Of those provided diet recommendations, only 20% (n=23) received an educational consult by a registered dietitian. Provision of diet recommendations was not affected by years in practice.

Conclusions:

Despite increasing awareness of the role of diet in the treatment of childhood FGIDs, a minority of patients receive diet recommendations in tertiary or primary care settings. When diet recommendations were given, there was great variability in the guidance provided.

Keywords: Education, Diet, IBS, FODMAPs

INTRODUCTION

Functional gastrointestinal pain disorders (FGIDs) represent one of the most prevalent conditions causing abdominal pain in children and adults; they affect an estimated 5-20% of the population worldwide 1,2. Patients with FGIDs are seen both in primary and tertiary care 2.

Treatment of FGIDs is challenging; however, diet-based therapies are gaining increasing recognition as being effective. Diet therapy in FGIDs is important as up to 80%-90% of both children and adults with FGIDs report that certain foods exacerbate their symptoms (abdominal pain, bloating, diarrhea, etc) 3-5. Avoidance in the diet of specific foods often can decrease symptoms6-9. For children and adults with FGIDs, treatments focused on altering diet intake have shown efficacy in improving symptoms and may lead to better clinical health outcomes and quality of life 10-12. Given these data, in children with FGIDs, diet-based therapies are often considered as first-line therapy 13.

Despite the importance of diet in treating FGIDs, the frequency with which diet recommendations are provided to children with FGIDs is, to our knowledge, unknown. Similarly, it is unclear what types of diet therapy are recommended in clinical practice. In addition, whether the setting (tertiary vs. care primary) affects whether diet recommendations are provided, and if so, what diets are suggested, is unclear. Thus, the aims of our study were to investigate the frequency and types of diet recommendations provided by tertiary versus primary care physicians to pediatric patients with FGIDs. We hypothesized that pediatric gastroenterologists (PGI) would be more likely to provide diet recommendations than primary care pediatricians (PCP). Secondarily, age/years in practice have been shown to affect physicians’ clinical practice methods14-16. Thus, we also hypothesized that years in practice might influence the frequency of providing diet recommendations.

METHODS

Design

We conducted a retrospective chart review of patients with FGIDs seen for the first time by either pediatric gastroenterology (PGI) or primary care (PCP) physicians at Texas Children’s Hospital in Houston, Texas from January 2015 to November 2017. The study was approved by the Baylor College of Medicine IRB. An initial diagnosis of FGIDs was made for the first time at the visit.

Study population

Children 4 to 18 years of age meeting Rome IV criteria 17 for one or more of the following FGIDs were included: functional abdominal pain (FAP), functional dyspepsia (FD), irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and/or abdominal migraines (AM). Patients were excluded if they had other chronic gastrointestinal diseases (e.g., inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease, eosinophilic esophagitis, acid reflux disease, peptic ulcer disease, functional constipation and cyclic vomiting) or other significant comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, cystic fibrosis, neurological disorders, endocrine disorders cardiovascular disease or renal disorders). For those patients initially diagnosed by a PCP and later referred to a PGI, only the initial encounter with the PCP was included. No subsequent visits were evaluated.

Data extraction

Patients were identified using ICD-10 codes for FAP, FD, IBS unspecified, IBS with diarrhea, IBS with constipation, and AM. Clinical data were extracted from an electronic medical records database (EPIC©, 2015, Verona, Wisconsin). Data collected included patient demographics (age, sex, race/ethnicity), diagnosis, provider (PGI vs PCP), time in practice, type of diet(s) recommended, and whether a dietitian consultation was obtained. Both PGI and PCP physicians had onsite access to a registered dietitian. All notes, patient’s instructions and after visit summaries were reviewed to identify diet recommendations provided.

Statistical analysis

Stata Version 15 (College Station, Texas) was used for data analysis. Patient and clinical characteristics were summarized using mean and standard deviation and frequency with percentage. Summary statistics were stratified by diet and provider and compared using a two-sample t-test, Wilcoxon rank sum test, Fisher’s exact test, or Chi-square test as appropriate. General estimating equations (GEE) with binomial family and logit link and exchangeable correlation were used to assess the association between provider and the odds of diet prescribed individually. Statistically significant factors were included in a multivariable GEE model. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

RESULTS

Patient Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

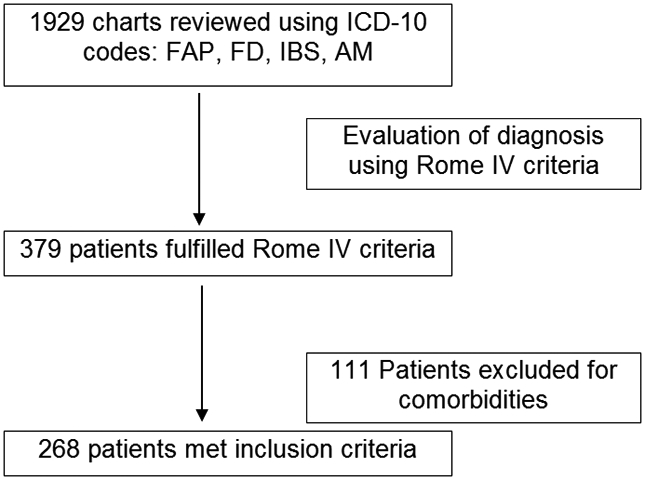

A total of 1929 charts were reviewed; of these, 375 patients met Rome IV criteria. Because of exclusion comorbidities, 268 patients met inclusion criteria (Figure 1). The demographic and clinical characteristics of the included patients are illustrated in Table 1. The mean ages were similar between groups. The proportion of females was greater in the PGI (66%) vs the PCP group (48%) (P=0.006). Race/ethnicity did not differ between the groups with White/Hispanic being the most common. IBS was the most common diagnosis in both groups.

Figure:

Patient Identification strategy

Table 1:

Demographics and Clinical Characteristics

| Variable | PGI (n=186) |

PCP (n=82) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 14.5 ± 2.8 * | 13.9 ± 3.0 * | 0.11 |

| Gender | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Female | 123 (66.1) | 39 (47.5) | 0.006 |

| Male | 63 (33.9) | 43 (52.5) | |

| Race | |||

| White | 138 (74.2) | 50 (61.0) | 0.081 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 29 (15.6) | 13 (15.9) | |

| African American | 8 (4.3) | 7 (8.5) | |

| No Specified | 8 (4.3) | 7 (8.5) | |

| Asian | 2 (1.1) | 3 (3.7) | |

| Other | 1 (0.5) | 2 (2.4) | |

| Diagnosis | |||

| IBS unspecified type | 91 (48.9) | 58 (70.7) | <0.001 |

| IBS with Diarrhea | 20 (10.8) | 18 (22.0) | |

| IBS with constipation | 35 (18.8) | 1 (1.2) | |

| IBS with Constipation and Diarrhea | 16 (8.6) | 4 (4.9) | |

| Functional Dyspepsia | 14 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Functional Abdominal pain | 8 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IBS and Functional Dyspepsia | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) |

Mean ± SD

Diet recommendations

Overall, of the 268 patients, 115 (43%) received medical nutrition therapy (Table 2). The proportion of patients receiving diet recommendations did not differ between the two groups (P=0.1, Table 2). Of the 115 provided diet advice, only 23 (19.8%) received an educational consult by a registered dietitian. Of the 23 who spoke with a registered dietitian, similar proportions were PGI vs PCP patients (PGI: n=13, 57%; PCP: n=10, 43%; P=1.0). For those who received recommendations, the most frequently prescribed diets were high fiber, the low fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAP) diet, and lactose restriction (Table 3).

Table 2:

Comparison between PGI vs PCP: Dietary education.

| No Dietary Recommendation (n=153) |

Dietary Recommendation (n=115) |

CHI Square P Value Primary Care vs Pediatric GI |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider type | |||||

| Pediatric GI | n=100 | 64.9% | n=86 | 74.8% | 0.10 |

| Primary Care | n=53 | 34.4% | n=29 | 25.2% | |

Table 3.

Types of Recommended Diets

| Type of Diet | PGI | PCP |

|---|---|---|

| Not specified* | 100 (53.8) # | 53 (64.6) |

| High fiber | 28 (15.1) | 12 (14.6) |

| Low FODMAPs | 22 (11.8) | 3 (3.7) |

| Lactose restriction | 13 (7.0) | 6 (7.4) |

| Healthy diet, low in fast/ processed foods. | 8 (4.3) | 0 (0.0) |

| High fiber, Lactose free diet | 1 (0.6) | 3 (3.7) |

| Avoidance of large meals, reduced intake of fat, insoluble fibers | 4 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Elimination diet | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) |

| Avoid fatty/fried and spicy food | 2 (1.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Avoidance of dietary triggers | 1 (0.6) | 1 (1.2) |

| Dairy, caffeine and tobacco restriction | 2 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) |

| Small portions, low fat, low acidity | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dietary log | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Low FODMAPs + High fiber | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Decrease cruciferous vegetables | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

| High calorie diet | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Fructose restriction diet | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.2) |

Not specified = no diet recommendation documented

Number (percent)

Time in Practice

Years in practice tended to be fewer in the PGI (12.5 ± 13.2 years) group versus the PCP group (17.5 ± 12.4 years) but did not reach statistical significance (P=0.07). Years in practice was not related to the likelihood of providing diet recommendations (P= 0.76, 95% CI: −0.52 to −10.5).

DISCUSSION

Studies continue to confirm the importance of diet as a therapeutic approach for treating FGIDs 18. Diet-based therapy is recommended as one of the first treatments to consider when managing FGIDs 13,19. However, even in a large pediatric hospital system such as ours, we identified that fewer than half of children with a FGID receive diet recommendations whether they are seen in tertiary or primary care. When diet recommendations were given, there was great variability in the diet guidance provided. These results suggest greater dissemination, implementation, and standardization of diet education for children with FGIDs are needed.

Studies have emphasized not only the importance of diet education for patients with FGIDs but also how enhancing knowledge in general about the disorders, including pharmacologic therapy and the importance of follow-up, can enhance patient quality of life 20,21. The potential clinical implications of identifying that only a minority of subjects receive diet advice may be found in the study by Ostgaard et al. 12. These investigators compared adult IBS patients who received two sessions of diet guidance versus those who did not 12. Two years after receiving education, the IBS education group continued to have a healthy diet, improved quality of life and reduced symptoms compared with the IBS patients not receiving diet guidance 12. Whether a lack of diet education results in a potential long-term decrease in quality of life in children with FGIDs remains to be determined.

Diet education for patients with FGIDs has been found to be an area of need as many patients with FGIDs demonstrate a lack of knowledge regarding basic concepts (definition, pathophysiology, therapy, diet, etc). One study showed that of 86 adult patients with IBS diagnosed in a primary care setting, 80% stated they had some general knowledge about IBS but 55% stated that it was “vague” and 24% stated that they had not received any information from their physicians 22. These results in adults parallel our observation in children with FGIDs, as a majority did not receive any diet information (Table 2). This is a particular concern, as a majority of patients prefer to receive medical information directly from healthcare physicians rather than from the Internet, handouts or books 23. Unfortunately for those subjects with FGIDs who do search for diet information on the internet, the information is often of low quality with a wide variety of recommendations provided 24. Additionally, further research is needed to determine the most efficacious, practical diet(s) and nutrition interventions using evidence-based principles.

Tertiary vs. primary care settings may differ in the recommendations provided for a variety of disorders 25,26. However, we did not identify a difference in the proportion of PGI versus PCP physicians who provided diet guidance. This is somewhat surprising given that FGIDs account for approximately 50% of all referrals to PGI and are one of the most common reasons for referral to PGI 27,28.

This study has some limitations. It is a retrospective study and therefore documentation of diet education was not routinely standardized. However, the low utilization of medical nutrition therapy provided by a registered dietitian in our study supports our overall finding of low rates of diet education. Our study reflects the practice of a single pediatric health care system and therefore our findings should be confirmed in additional healthcare settings. Finally, we only evaluated the first visit. It is possible that diet recommendations were given if there were subsequent visits. Strengths of the study include obtaining information from two practice settings (tertiary vs. primary care,) and the use of “real world” clinical practice data. These strengths are likely to add to the generalizability of our findings. Additional strengths include the relatively large sample size and evaluation of time in practice as a potential variable.

Overall our study results stress the need for physicians caring for children with FGIDs to be more cognizant to provide diet education and to refer to a registered dietitian for not only diet education but overall nutrition assessment that may ensure a better outcome. Efforts in this area will respond to the desire of patients and their parents to have better knowledge regarding potential diet interventions29 and also may lead to better clinical outcomes.

Clinical Relevancy Statement.

Diet education from physicians and referral to a registered dietitian for medical nutrition therapy can impact the ability of patients and families to understand how diet can improve health outcomes. Our goal is that physicians become aware of the need of providing diet education and referral services in the outpatient setting, to not only improve adherence to diet treatment, but to better understand how diet can impact the management of GI disorders.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure:

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health: Dr. Chumpitazi grants # (K23 DK101688 and R03 DK117219). Dr. Shulman is funded by NIH grant# (R01 NR013497), the Daffy’s Foundation, and the USDA/ARS under Cooperative Agreement No. 6250-51000-043, and P30 DK56338 which funds the Texas Medical Center Digestive Disease Center.

Abbreviations:

- FGIDs

Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders

- FAP

Functional Abdominal Pain

- FD

functional dyspepsia

- IBS

Irritable Bowel Syndrome

- AM

Abdominal migraine

- PGI

Pediatric Gastroenterologists

- PCP

Primary Care Physicians

- SD

Standard Deviation

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Robin SG, Keller C, Zwiener R, et al. Prevalence of Pediatric Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders Utilizing the Rome IV Criteria. J Pediatr. 2018;195:134–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oshima T, Miwa H. Epidemiology of Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in Japan and in the World. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2015;21(3):320–329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee HJ, Kim HJ, Kang EH, et al. Self-reported Food Intolerance in Korean Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chumpitazi BP, Weidler EM, Lu DY, Tsai CM, Shulman RJ. Self-Perceived Food Intolerances Are Common and Associated with Clinical Severity in Childhood Irritable Bowel Syndrome. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016;116(9):1458–1464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chumpitazi BP, McMeans AR, Vaughan A, et al. Fructans Exacerbate Symptoms in a Subset of Children With Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(2):219–225 e211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chumpitazi BP, Cope JL, Hollister EB, et al. Randomised clinical trial: gut microbiome biomarkers are associated with clinical response to a low FODMAP diet in children with the irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42(4):418–427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Halmos EP, Power VA, Shepherd SJ, Gibson PR, Muir JG. A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(1):67–75 e65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carroccio A, Brusca I, Mansueto P, et al. Fecal assays detect hypersensitivity to cow’s milk protein and gluten in adults with irritable bowel syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9(11):965–971 e963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fritscher-Ravens A, Pflaum T, Mosinger M, et al. Many Patients With Irritable Bowel Syndrome Have Atypical Food Allergies Not Associated With Immunoglobulin E. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):109–118 e105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cozma-Petrut A, Loghin F, Miere D, Dumitrascu DL. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome: What to recommend, not what to forbid to patients! World J Gastroenterol. 2017;23(21):3771–3783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paul SP, Basude D. Non-pharmacological management of abdominal pain-related functional gastrointestinal disorders in children. World J Pediatr. 2016;12(4):389–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ostgaard H, Hausken T, Gundersen D, El-Salhy M. Diet and effects of diet management on quality of life and symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Mol Med Rep. 2012;5(6):1382–1390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandhu BK, Paul SP. Irritable bowel syndrome in children: pathogenesis, diagnosis and evidence-based treatment. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(20):6013–6023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sood R, Sood A, Ghosh AK. Non-evidence-based variables affecting physicians’ test-ordering tendencies: a systematic review. Neth J Med. 2007;65(5):167–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liao K, Blumenthal-Barby J, Sikora AG. Factors Influencing Head and Neck Surgical Oncologists’ Transition from Curative to Palliative Treatment Goals. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017;156(1):46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whiting P, Toerien M, de Salis I, et al. A review identifies and classifies reasons for ordering diagnostic tests. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60(10):981–989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyams JS, Di Lorenzo C, Saps M, Shulman RJ, Staiano A, van Tilburg M. Functional Disorders: Children and Adolescents. Gastroenterology. 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.El-Salhy M, Gundersen D. Diet in irritable bowel syndrome. Nutr J. 2015;14:36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hyams JS. Irritable bowel syndrome, functional dyspepsia, and functional abdominal pain syndrome. Adolesc Med Clin. 2004;15(1):1–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Joc EB, Madro A, Celinski K, et al. Quality of life of patients with irritable bowel syndrome before and after education. Psychiatr Pol. 2015;49(4):821–833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mishima Y, Furuta K, Ishihara S, Adachi K, Kinoshita Y. Education to the patients of irritable bowel syndrome: diet and lifestyle advice. Nihon Rinsho. 2006;64(8):1511–1515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ringstrom G, Agerforz P, Lindh A, Jerlstad P, Wallin J, Simren M. What do patients with irritable bowel syndrome know about their disorder and how do they use their knowledge? Gastroenterol Nurs. 2009;32(4):284–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flik CE, van Rood YR, de Wit NJ. Systematic review: knowledge and educational needs of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27(4):367–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alfaro-Cruz L, Kaul I, Zhang Y, Shulman RJ, Chumpitazi BP. Assessment of Quality and Readability of Internet Dietary Information on Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(3):566–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, Smyth C. Irritable bowel syndrome: the view from general practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9(7):689–692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, Smyth C. Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral. Gut. 2000;46(1):78–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dipasquale V, Corica D, Gramaglia SMC, Valenti S, Romano C. Gastrointestinal symptoms in children: Primary care and specialist interface. Int J Clin Pract. 2018;72(6):e13093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Soares RL. Irritable bowel syndrome: a clinical review. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(34):12144–12160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hughes M. Patient attitudes to health education in general practice. Health Education Journal. 1988;4(4):130–132. [Google Scholar]