Abstract

Purpose

To design and implement a novel, universally offered, computerized clinical decision support (CDS) gonorrhea and chlamydia (GC/CT) screening tool embedded in the emergency department (ED) clinical workflow and triggered by patient-entered data.

Methods

The study consisted of the design and implementation of a tablet-based screening tool based on qualitative data of adolescent and parent/guardian acceptability of GC/CT screening in the ED and an advisory committee of ED leaders and end users. The tablet was offered to adolescents 14–21 years and informed patients of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention GC/CT screening recommendations, described the testing process and assessed whether patients agreed to testing. The tool linked to CDS that streamlined the order entry process. The primary outcome was the patient capture rate (proportion of patients with tablet data recorded). Secondary outcomes included rates of patient agreement to GC/CT testing and provider acceptance of the CDS.

Results

Outcomes at the main and satellite EDs, respectively, were as follows: one year patient capture rates were 64.6% and 64.5%; 9.9% and 4.4% of patients agreed to GC/CT testing and of those, the provider ordered testing for 73% and 72%..

Conclusion

Implementation of this computerized screening tool embedded in the clinical workflow resulted in patient capture rates of almost two thirds and clinician CDS acceptance rates > 70% with limited patient agreement to testing. This screening tool is a promising method for confidential GC/CT screening among youth in an ED setting. Additional interventions are needed to increase adolescent agreement for GC/CT testing.

Keywords: Medical informatics, Clinical decision support systems, Electronic health records, Pediatrics, Sexually transmitted diseases, Sexually transmitted infections, Adolescents

Over 20 million new sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are diagnosed every year with half occurring among 15 to 24 year olds [1]. STI screening among adolescents is particularly important not only because they are at relatively high risk for STIs, but are also a difficult population to reach due to lack of a medical home [2]. Many of these adolescents seek care in the emergency department (ED) for a variety of healthcare issues [3–6]. Preliminary ED data showed that symptomatic adolescents routinely receive STI testing, but <1% of asymptomatic adolescents are screened [7]. Baseline rates of overall STI testing are lacking in the literature with only one pediatric ED reporting baseline STI testing of 9.3%. [8]

The United States Preventive Services Task Force and experts in this field have noted the potential for EDs to serve as an effective site for STI screening. [9–11] Although 79% of US hospitals now use an electronic health record (EHR), effective modifications to the EHR to implement gonorrhea and chlamydia (GC/CT) ED screening programs into the clinical workflow are limited.

Previous qualitative studies have demonstrated that most ED healthcare providers (HCP) are supportive of STI screening if it can be incorporated into the clinical workflow [12]. Literature has shown that the technology must be user friendly and easily incorporated into an existing EHR [13–15]. Adolescents who participated in a qualitative study regarding ED STI screening preferred that screening be offered in a private room using tablet based technology. The adolescents and parents/guardians believed that tablets would address concerns about confidentiality, be preferable due to adolescent familiarity with technology and potentially increase the rate of agreement to be screened [16]. Additionally, the use of direct patient reported information is particularly appealing as it provides a confidential venue for transmission of sensitive sexual health information among adolescents [17, 18]. Therefore, the goal of this study was to design and implement a novel, universally offered, computerized, confidential clinical decision support (CDS) GC/CT screening tool embedded in the clinical workflow and triggered by patient-entered data.

METHODS

Selection of Participants

All ED patients 14–21 years of age were eligible to participate in the tablet based screening tool. The implementation goal was to universally offer confidential, tablet based GC/CT screening regardless of sexual activity, as this approach is consistent with the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommendations for age-based HIV screening [19]. We focused solely on GC/CT screening because the CDC recommends yearly screening for women < 25 years and men in high risk settings [20]. Throughout the manuscript, a reference to STI indicates GC and CT.

Study Design and Setting

Information technology expertise was used to design a GC/CT screening tool in a real world setting and incorporate the tool into current clinical flow. This screening tool was implemented in two pediatric EDs at the same institution and data was collected over one year. The first is the institution’s main ED, which is an urban, tertiary care, level 1 trauma center with over 62,000 annual visits; approximately 25% are ages 14–21, 41% Black, 56% White, 2.8% Hispanic, 52% government insured and 41% privately insured. The second is the institution’s satellite ED, which is located in a northern suburb and has over 36,000 annual visits; approximately 20% are ages 14–21 years,15% Black, 78% White, 6.8% Hispanic, 35% government insured and 62%privately insured. Both sites have rotating trainees and use the Epic EHR (Verona, WI; 2009) for all documentation and orders. This study was reviewed and approved by the hospital’s Institutional Review Board.

Informatics Infrastructure

The initial phase consisted of the design of a tablet-based screening tool. The design was based on a qualitative study of adolescent and parent/guardian acceptability of ED STI screening, and feedback from ED leaders and end users [16]. The registration staff were assigned to administer the tablet to all 14 −21 year olds. Prior to implementation of the tablet screening intervention, it was standard workflow for registration staff to interact with each patient and his/her family in their private room. Therefore, we did not alter any already established workflow. The patient rooms were all individual rooms with doors, and family may have been present during the process. The initial tablet screen (Figure 1) provided a standardized script for registration staff to introduce the tablet and refer parent questions to the clinical staff.

Figure 1:

Tablet screenshot of patient screening script and options for decline reasons

If there was a specific reason for not offering screening to a patient, the registration staff had the ability to choose a refusal reason. A drop down menu of common refusal reasons and a free text field was available. Reasons included: parent declines, patient declines, non-English speaking, critically ill, developmentally delayed, aggressive/violent or other free text reason.

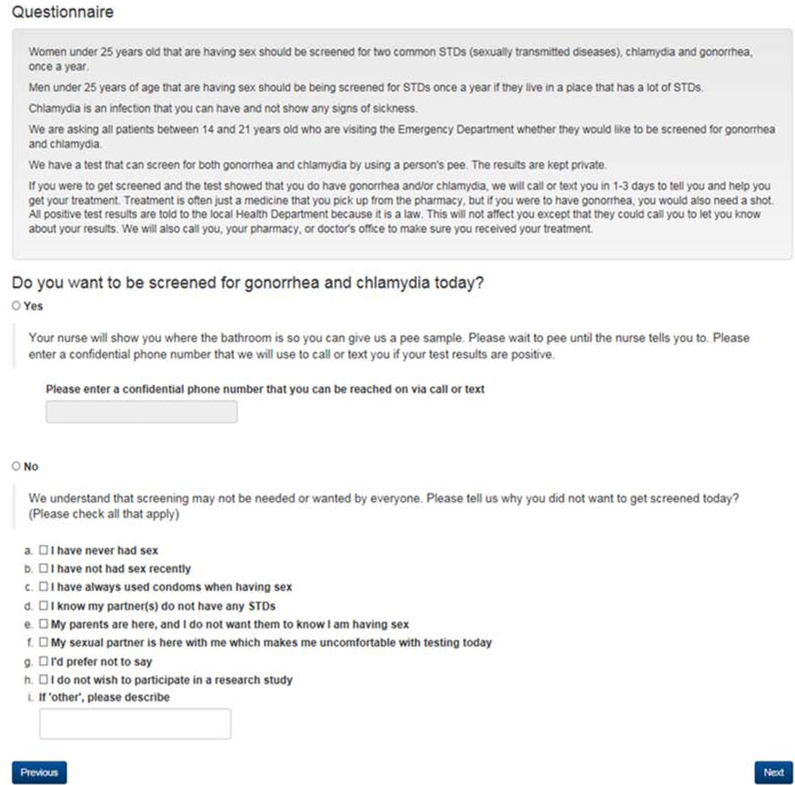

The tablet interface for patient interaction (Figure 2) was developed to inform patients of CDC STI screening recommendations, to describe the clinical testing process and to ask patients whether they agree to testing during their visit. The text was based on existing literature and qualitative data collected from adolescents [16]. Cognitive interviews were administered to assure readability and comprehension. The word content was formatted to reflect an eighth grade reading level per the Flesch-Kincaid Readability Scale. Adding the words gonorrhea and chlamydia elevated the reading level to eleventh grade [21]. To use proper terminology when referring to STIs, we retained these words in the text. Version 1 was administered to 10 patients, and edits were made based on patient feedback and comprehension. Version 2 was administered to 8 patients and no further changes were indicated.

Figure 2:

Tablet screenshot that patient completes for GC/CT screening

The final tablet screen was designed to ensure the patient entered information was transferred to the correct chart. This screen included fields to enter the patient’s medical record number, the encounter number and staff credentials. This step initiated the transfer of data from the tablet to the EHR through an Application Programming Interface. The patient’s choice for STI screening (yes/no) was incorporated into an EHR flowsheet and timeline, with a comment indicating that this was patient-entered data.

Once the patient tablet screens were finalized, the provider CDS was designed in the form of a Best Practice Advisory. The CDS displayed when a patient chose “yes” to STI screening. This CDS alert (Figure 3) informed the provider of the patient’s choice and included links to GC/CT orders as well as a field to document the reason for not placing the suggested order if applicable.

Figure 3:

Epic screenshot of Best Practice Advisory/Clinical Decision Support displayed for those patients who agree to GC/CT screening

Workflow Considerations

During the iterative process of designing the tool and evaluating the related workflow, we evaluated several aspects: 1) which ED staff were responsible for offering screening, 2) time during ED visit when screening was offered, 3) content and format of information relayed at the time of screening, and 4) methods for approaching adolescents in the presence of parents.

We obtained provider and registration staff feedback during the testing process through email, face-to-face interaction and supervisor-relayed feedback. In order for this process to be successful, it was important that registration leadership supported the intervention. Because many of the registration staff were not clinically trained, there was some anxiety surrounding the sensitive topic of STI testing. Therefore, anonymous feedback forms were placed in a designated ED location for provider or registration staff who were uncomfortable giving feedback directly to their supervisor during the re-design process. We ensured the laboratory was adequately equipped to meet the increased demand for STI testing. We educated ED providers, ancillary care and registration staff regarding the purpose and planned execution of the program.

The final tablet screening process was presented at physician, nurse practitioner and nursing staff meetings. Job aids describing how to use the CDS were emailed to all providers. A video outlining the process was developed and was posted on the residents’ orientation website. All rotating residents received an email prior to their ED rotation explaining the screening process and providing a link to the video.

Implementation of Intervention

All tablets were locked-down to only access the web-based screening tool. To login to the tablet, a password was required as mandated by information technology security at our institution. All registration staff were informed of the password. After log-in, the registration staff entered the patient’s date of birth only to confirm that the patient met the age range eligibility. If the date of birth was outside the age range of eligibility, no further tablet screens would appear. The registration staff could decide that the patient was ineligible to receive the tablet per previously listed refusal reasons and were able to enter a reason for exclusion/decline (Figure 1) or choose “other” and enter a free text reason for exclusion thus discontinuing the process.

Patients who met age criteria and were not excluded by the registration staff were given the tablet. At the top of the first screen, we listed the CDC recommendations regarding screening guidelines, the process for screening and follow up procedures. The patient then electronically agreed to or declined STI testing (Figure 2). Those who agreed to STI testing also completed a field entering his/her confidential phone number to be used to relay final test results. Once completed, the subsequent tablet screen instructed the patient to return the tablet to the registration staff who did not have access to any patient entered responses. The registration staff then entered the patient’s medical record and encounter number and “signed” the tablet with their log-in credentials. The two patient identifiers were entered to assure the information was being transmitted to the appropriate patient EHR. The registration staff credentials were entered to “send” the information to the EHR.

The patient’s choice of STI screening then auto-populated into the EHR and was documented in a flow sheet row and the timeline as “yes” or “no”. If the patient refused STI screening, the patient was asked to provide a refusal reason and nothing further occurred (Figure 2). If the patient agreed to STI screening, a pop-up CDS alert was displayed in the patient’s EHR when the chart was initially opened by the provider. The CDS acknowledged the patient agreed to GC/CT testing and then prompted the provider to order testing. Once completed, the CDS did not appear again. While logic was created to suppress the CDS if existing orders were present, if the CDS appeared, we provided “already ordered” as a decline option to account for possible duplicate orders and identify any logic errors. If the provider chose not to order the testing, he/she was prompted to document a reason (Figure 3). Once either of these choices were selected, the CDS would not appear again. If this was not the provider’s patient (e.g. the provider mistakenly opened the incorrect chart), he/she could select that option, and the CDS would re-appear for the next provider who accessed the chart. Additionally, if the provider closed the CDS without interacting with it, the CDS would not appear again.

There were early connectivity issues to the server that intermittently interfered with implementation. When hospital servers were updated, challenges arose with server connectivity. Since our information technology department took responsibility for the tablets once implemented, all technologic issues could be addressed 24 hours a day, thus there were minimal interruptions in tablet functionality. Because up to four registration staff worked simultaneously, we allocated six tablets so that several could be charging while others were being used. All tablets had a charging cord and a designated locked space where they were stored and charged.

Spot checks of staff compliance were initiated after the process was implemented. There were instances of discrepancy between the staff entered data and patient report of whether the process was offered. We did not have a process in place to reliably check every registration staff decline, instead, registration staff were given his/her monthly individual data regarding the number of eligible patients he/she registered, number of patients who were missed, number of patients with a decline reason and the number of patients with patient entered data. This was implemented to encourage staff to comply with this new process. This information was distributed to the registration individuals and supervisors on a weekly basis.

Outcome Measures

The primary outcome was patient capture rate, defined as the number of patients seen in the ED 14–21 years of age with any tablet data recorded (including registration staff refusal data) in relation to all 14–21 year olds who presented to the ED during the same time period. This was a measure of feasibility and acceptability of this process among the registration staff.

The secondary outcome was the rate of HCP ordering STI testing among those patients in whom the CDS was triggered. Additional secondary outcomes included the proportion of patients agreeing to STI testing among those who had tablet data recorded, refusal reasons documented by registration staff, refusal reasons documented by the patient and clinician reasons for not ordering testing among patients whom the CDS was triggered. Counts, descriptive statistics and chi-square tests were reported.

RESULTS

Prior to this intervention, total GC/CT testing rates were 7.9% at the main ED and 2.6% at the satellite ED, and asymptomatic screening rates were <1% at both sites. Over one year, 15,252 patients between the ages of 14 and 21 years sought care at the main ED. Monthly patient capture rates of administering the tablet ranged from 58% to 69.9% of age-eligible patients with a total capture rate over the 12 month study period of 9851 (64.6%) patients. At the satellite ED, 7003 patients between the ages of 14 and 21 years sought care. Monthly patient capture rates ranged from 52.4% to 71.7% of age-eligible patients with a total capture rate over the 12 month study period of 4516 (64.5%) patients. Between 30% and 40% of these patients at both sites had a refusal reason entered by registration staff. These reasons and adolescent decline reasons among patients who were offered the tablet, are reported in Table 1.

Table 1:

Registration staff and patient decline reasons

| Main ED total declines n=8875 n(%) |

Satellite ED total declines n=4316 n(%) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Total Registration Staff Declines | 3565* | 1287* |

| Violent patient | 235 (6.6%) | 73 (5.7%) |

| Critically ill | 499 (13.9%) | 242 (18.8%) |

| Developmentally delayed | 342 (9.6%) | 161 (12.5%) |

| Non-English speaking | 96 (2.7%) | 62 (4.8%) |

| Parent declined | 455 (12.8%) | 221 (17.2%) |

| Patient declined | 1198 (33.6%) | 301 (23.4%) |

| Other | 1189 (33.4%) | 365 (28.4%) |

| Alleged sexual abuse | 3 | 25 |

| Tablet not functioning | 31 | 9 |

| Patient condition (e.g. Migraine) | 552 | 224 |

| Psychiatric | 67 | 10 |

| Staff/care interruptions | 210 | 31 |

| No reason documented | 304 | 66 |

| Total Patient Declines | 4756* | 2590* |

| Not sexually active | 2721 (57.2%) | 1641 (63.4%) |

| No recent sex | 728 (15.3%) | 324 (12.5%) |

| Uses condoms | 554 (11.6%) | 232 (9%) |

| Uninfected partner | 730 (15.3%) | 324 (12.5%) |

| Parents present | 200 (4.2%) | 101 (3.9%) |

| Partner present | 22 (0.5%) | 6 (0.2%) |

| Prefer not to say | 244 (5.1%) | 102 (3.9%) |

| Declined research study participation | 802 (16.9%) | 534 (20.6%) |

| Other | 173 (3.6%) | 73 (2.8%) |

| Already tested previously | 103 | 35 |

| Patient condition (e.g. Migraine) | 6 | 9 |

| Non-English speaking | 2 | 0 |

| Parent refused | 3 | 0 |

| No reason documented | 59 | 29 |

More than one reason for decline may have been indicated.

Of those who had tablet data at the main ED (n=9854), 979 (9.9%) agreed to STI testing and those who agreed were more likely to be female versus male (p<.01), ages 18–21 years (p<.01) versus the younger age groups, black versus white or other races (p<.01), and government insured versus private or self-pay (p<.01). There was a statistically significant difference in ethnicity but an extremely small absolute difference. Among these patients, the CDS was triggered in the EMR 704 (72%) times. At the satellite ED 4,516 had tablet data and 200 (4.4%) agreed to STI testing. Those who agreed were more likely to be 16–17 years of age versus the older or younger age groups (p<.01), government insured or self-pay vs. privately insured (p<.01) and other or white race versus black (p=0.01). There was no difference in gender or ethnicity. Among these patients, the CDS was triggered 124 (62%) times.

Among patients for whom the CDS was triggered at the main ED (n=704), the HCP ordered STI testing for 512 (73%) patients (Figure 4a). HCP reasons for not ordering GC/CT testing included: testing already ordered (n=7), not my patient (n=3), accepted the CDS initially but subsequently removed the orders (n=131), nothing recorded (n=4), or other (n=47). Among those who agreed to STI testing but the CDS did not trigger (n=275), 229 (83%) already had testing ordered, and thus the CDS was not needed. Most of the remaining 45 patients had no CDS trigger because they were already discharged in the EMR due to being registered and consented at the end of their visit.

Figure 4:

Main (a) and satellite ED (b) flow charts of patient uptake and refusals

Among patients for whom the CDS was triggered at the satellite ED (n=124), the HCP ordered STI testing for 89 (72%) patients (Figure 4b). HCP reasons for not ordering the testing included: testing already ordered (n=1), not my patient (n=1), accepted the CDS initially but subsequently removed the orders (n=25) or other (n=8). Among those who agreed to STI testing but the CDS did not trigger (n=76), 44 already had testing ordered, and thus the CDS was not needed. Similarly to the Base ED, most of the remaining 32 patients had no CDS trigger because they were already discharged in the EHR.

DISCUSSION

The design, development, and implementation of a computerized, universally offered GC/CT screening process was described. This screening process is innovative in that it is the first process that universally offers computerized GC/CT screening in the pediatric ED setting based on age rather than risk factors [8, 22]. This is important as it has been shown that adolescents are not always truthful in their responses to sexual history questions, which may result in inaccurately categorizing their risk and consequently excluding them from being offered screening [23, 24]. This design is supported by previous literature of school based and pediatric ED screening programs that have demonstrated feasibility using an age-based screening approach as well as the HIV screening approach recommended by the CDC [19, 25, 26]. In our study, adolescents were informed of the screening recommendations and subsequently asked to choose for him/herself whether he/she would like to be screened.

Overall, tablet data were entered on 65% of all 14–21 year olds at both ED sites. Our participation rates were slightly higher than a previous study which used research personnel to administer the tablet. This may be related to the fact that our study included patients presenting 24 hours a day as opposed to those presenting only during specified research assistant hours. [8] This highlights the real world challenges of relying on personnel to initiate the screening process. Despite the intention to offer screening to every adolescent 14–21 years of age, 35% of the eligible population did not have any tablet data documented.

Of the patients with recorded tablet data, 30–40% had decline reasons entered by the registration staff. Those adolescents did not have the opportunity to agree or decline testing on the tablet. Despite providing weekly, individual feedback reports to registration staff, the number of decline reasons remained consistent throughout the implementation process and the registration staff decline reasons were similar between sites. The most common reason at both sites for not offering the tablet to the patient was that the patient initially declined or there was an unspecified “other” reason recorded. It is unclear the accuracy of these decline reasons as some staff initially expressed being uncomfortable offering a tablet on a sensitive subject. Therefore, it is possible that the unspecified “other” reason reflected the individual staff discomfort. Among patients who entered data into the tablet, patient declines also were similar between both sites with over half declining due to no history of sexual activity. This was expected as sexual activity was not initially used as an exclusion criteria.

Among those patients who had tablet data, patient agreement to STI testing was more than double at the main ED (9.9%) versus the satellite ED (4.4%). As in our previous study, those who agreed to testing at the main ED were more likely to be black and government insured [27]. The greater acceptance of patients seen at the main ED is likely secondary to the urban location and the epidemiology of GC/CT in the surrounding county versus the satellite ED [28]. Baseline rates of testing and positivity are much higher at the main ED which suggests a difference in the number of symptomatic patients seeking care at each site. Patients frequenting the main ED may be more accustomed to seeking STI care in the ED setting, and thus more willing to participate in screening opportunities. However, the percentage of clinician acceptance of the CDS tool to order STI testing was similar at both sites (72–73%) which was likely a result of the same providers working at both sites. It is possible that those providers who didn’t order the STI testing may not agree that the ED has a role in preventive care thus only ordered testing on those who were symptomatic [12].

The generalizability of this study may be limited as the Epic EHR may not be available at other institutions. Additionally, because registration staff interacted with each patient in his/her private exam room, we chose to use these personnel to administer the tablets. This decision was made based on key informant input and not on a rigorous workflow analysis. Therefore, it is possible that uptake and patient acceptance would have been improved with another method of tablet administration. Some institutions may also lack the financial resources and staff to maintain tablets and create the tool interface. There may be challenges with buy-in from ED administration, staff who are responsible for following up an increased number of lab results and concerns around staff and patient time needed to distribute and complete the tool. In developing the CDS, technical constraints and health system policies added complexity to the workflow that we will work to overcome in future work.

Implementation of a computerized CDS STI screening tool embedded in the clinical workflow and triggered by patient-entered data resulted in patient capture rates of almost two thirds of the population and clinician CDS acceptance rates above 70%. This computerized screening tool is a promising method to increase confidential STI screening among high risk youth in an ED setting, but additional interventions are needed to further increase acceptance of STI testing by adolescents. Future research is needed to examine the most efficient method to integrate this intervention into multiple institutions nationally while increasing the acceptance rates of testing among ED adolescents.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONTRIBUTIONS.

Screening adolescents confidentially for sensitive health topics in the emergency department can be challenging. This computerized screening approach was embedded into clinical workflow and is a promising method for various preventative screening interventions among adolescents that can be implemented at other institutions.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Jill S. Huppert MD, MPH for her mentorship, support and editing of this manuscript.

Funding source:

NICHD/NIH K23HD075751 Career Development Award. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

This publication was supported by an Institutional Clinical and Translational Science Award, NIH/NCATS 1UL1TR001425. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

List of Abbreviations

- CDS

Clinical Decision Support

- GC

Gonorrhea

- CT

Chlamydia

- STIs

Sexually Transmitted Infections

- ED

Emergency Department

- HCP

Healthcare Providers

- EHR

Electronic Health Records

- BPA

Best Practice Advisory

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: All authors report no conflicts of interest.

Clinical Trials Registry Site and Number: N/A

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- [1].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/default.htm Accessed August 22 2019.

- [2].Irwin CE Jr., Adams SH, Park MJ, et al. Preventive care for adolescents: few get visits and fewer get services. Pediatrics 2009;123:e565–572. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2008-2601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Wilson KM, Klein JD. Adolescents who use the emergency department as their usual source of care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2000;154:361–365. DOI: 10.1001/archpedi.154.4.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Ziv A, Boulet JR, Slap GB. Emergency department utilization by adolescents in the United States. Pediatrics 1998;101:987–994. DOI: 10.1542/peds.101.6.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Cohen DA, Kanouse DE, Iguchi MY, et al. Screening for sexually transmitted diseases in non-traditional settings: a personal view. Int J STD AIDS 2005;16:521–527. DOI: 10.1258/0956462054679115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Mossenson A, Algie K, Olding M, et al. ‘Yes wee can’ - a nurse-driven asymptomatic screening program for chlamydia and gonorrhoea in a remote emergency department. Sex Health 2012;9:194–195. DOI: 10.1071/SH11064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Dexheimer JW, Taylor RG, Kachelmeyer AM, et al. The Reliability of Computerized Physician Order Entry Data for Research Studies. Pediatr Emerg Care 2019;35:e61–e64. DOI: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000001726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ahmad FA, Jeffe DB, Plax K, et al. Computerized self-interviews improve Chlamydia and gonorrhea testing among youth in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2014;64:376–384. DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Mehta SD, Hall J, Lyss SB, et al. Adult and pediatric emergency department sexually transmitted disease and HIV screening: programmatic overview and outcomes. Acad Emerg Med 2007;14:250–258. DOI: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.10.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Meyers D, Wolff T, Gregory K, et al. USPSTF recommendations for STI screening. Am Fam Physician 2008;77:819–824. DOI: https://www.aafp.org/afp/2008/0315/p819.pdf. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Mehta SD. Gonorrhea and Chlamydia in emergency departments: screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Curr Infect Dis Rep 2007;9:134–142. DOI: 10.1007/s11908-007-0009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gillespie GL, Reed J, Holland CK, et al. Pediatric emergency department provider perceptions of universal sexually transmitted infection screening. Adv Emerg Nurs J 2013;35:76–86. DOI: 10.1097/TME.0b013e31827eabe5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Hesse BW, Shneiderman B. eHealth research from the user’s perspective. Am J Prev Med 2007;32:S97–103. DOI: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Marcy TW, Kaplan B, Connolly SW, et al. Developing a Decision Support System for Tobacco Use Counseling Using Primary Care Physicians. Inform Prim Care 2008;16:101. DOI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Wears RL, Berg M. Computer technology and clinical work: still waiting for Godot. JAMA 2005;293:1261–1263. DOI: 10.1001/jama.293.10.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Reed JL, Punches BE, Taylor RG, et al. A Qualitative Analysis of Adolescent and Caregiver Acceptability of Universally Offered Gonorrhea and Chlamydia Screening in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med 2017;70:787–796 e782. DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Deshpande PR, Rajan S, Sudeepthi BL, et al. Patient-reported outcomes: A new era in clinical research. Perspect Clin Res 2011;2:137–144. DOI: 10.4103/2229-3485.86879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].National Quality Forum. Patient Reported Outcomes (PROs) in Performance Measurement. Available at: http://www.qualityforum.org/WorkArea/linkit.aspx?LinkIdentifier=id&ItemID=72537 Accessed August 22, 2019.

- [19].Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep 2006;55:1–17; quiz CE11–14. DOI: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5514a1.htm. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep 2015; Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm Accessed May 15, 2019.

- [21].Readability Formulas. The Flesch Grade Level Readability Formula. Available at: http://www.readabilityformulas.com/flesch-grade-level-readability-formula.php Accessed August 22, 2019.

- [22].Goyal MK, Fein JA, Badolato GM, et al. A Computerized Sexual Health Survey Improves Testing for Sexually Transmitted Infection in a Pediatric Emergency Department. J Pediatr 2017;183:147–152 e141. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.12.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Rosenthal SL, Burklow KA, Biro FM, et al. The reliability of high-risk adolescent girls’ report of their sexual history. J Pediatr Health Care 1996;10:217–220. DOI: 10.1016/S0891-5245(96)90004-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Clark LR, Brasseux C, Richmond D, et al. Are adolescents accurate in self-report of frequencies of sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancies? J Adolesc Health 1997;21:91–96. DOI: 10.1016/s1054-139x(97)00042-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Silva A, Glick NR, Lyss SB, et al. Implementing an HIV and sexually transmitted disease screening program in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med 2007;49:564–572. DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Han JS, Rogers ME, Nurani S, et al. Patterns of chlamydia/gonorrhea positivity among voluntarily screened New York City public high school students. J Adolesc Health 2011;49:252–257. DOI: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Schneider K, FitzGerald M, Byczkowski T, et al. Screening for Asymptomatic Gonorrhea and Chlamydia in the Pediatric Emergency Department. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43:209–215. DOI: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Ohio Department of Health. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Data and Statistics. Available at: https://odh.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/odh/know-our-programs/std-surveillance/data-and-statistics/sexually-transmitted-diseases-data-and-statistics Accessed August 22, 2019.