Abstract

Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM) experience alarming HIV disparities alongside sub-optimal engagement in HIV interventions. Among MSM, stigma toward anal sexuality could interfere with engagement in HIV prevention, yet few studies have examined MSM perspectives on anal sex stigma or its health-related sequelae. Guided by theory, we aimed to characterize anal sex stigma, related sexual concerns, and barriers to health seeking, like concealment. We elicited community input by purposively interviewing 10 experts in MSM health and then 25 racially, ethnically, and geographically diverse cisgender MSM. Participants reported experienced, internalized, and anticipated forms of anal sex stigma that inhibited health seeking. Experienced stigma, including direct and observed experiences as well as the absence of sex education and information, contributed to internalized stigma and anticipation of future devaluation. This process produced psychological discomfort and concealment of health-related aspects of anal sexuality, even from potentially supportive sexual partners, social contacts, and health workers. Participants characterized stigma and discomfort with disclosure as normative, pervasive, and detrimental influences on health-seeking behavior both during sex and within healthcare interactions. Omission of information appears to be a particularly salient determinant of sexual behavior, inhibiting prevention of harm, like pain, and leading to adverse health outcomes. The development of measures of anal sex stigma and related sexual concerns, and testing their impact on comfort with disclosure, sexual practices, and engagement in health services could identify modifiable social pathways that contribute to health disparities among MSM, like those seen in the HIV epidemic.

Keywords: sexual stigma, anal sexuality, anal sex stigma, men who have sex with men, HIV/AIDS, qualitative research

INTRODUCTION

Stigma is a social process that devalues groups of people based on specific attributes (Goffman 1963; Herek 2009a; Link & Phelan. 2001; Stahlman et al. 2017). Sexual stigma more specifically refers to the devaluation of any non-heterosexual behavior, identity, relationship, or community, embodied in distinct experienced, internalized, and anticipated forms (Herek et al. 2007). Experienced stigma involves negative actions, like discrimination (e.g., shaming, punishment) and neglect (e.g., sex education focused solely on reproduction) (Kubicek et al. 2010; Middelthon 2002). Experiences can then be internalized as part of one’s personal value system and self-concept, and eventually anticipated as likely to be enacted by others in the future (Herek et al. 2007). Sexual stigma often prompts urges to conceal (Herek et al. 1998; Overstreet et al. 2013; Quinn & Earnshaw 2011; Quinn et al. 2019), to the extent that people can hide their devalued attributes (Pachankis 2007; Quinn & Chaudoir 2009).

Sexual stigma impedes health seeking (Herek 2009b; 2009a; Institute of Medicine 2011; Stahlman et al. 2017). Among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (MSM), sexual stigma interferes with access to health interventions, like condoms, lubricants, and medications, by contributing to discomfort and stereotyping among health workers as well as to men’s discomfort and difficulty disclosing sexual identity and activity (Ayala et al. 2013; Calabrese et al. 2013; Kinsler et al. 2007; Krakower & Mayer 2012; Mantell et al. 2009; Wolitski & Fenton 2011). Health workers report particular difficulty broaching the subject of sexual behavior with MSM (Drainoni et al. 2009) and variable comfort obtaining a sexual history, essential components to identify opportunities for intervention (Carter et al. 2014). For MSM, concealment of sexual behavior and sexual identity is fairly normative (McKirnan et al. 2013; Meites et al. 2013), even more so among racial and ethnic minorities (Bernstein et al. 2008; Eaton et al. 2015; Glick & Golden 2010; Millett et al. 2012; Radcliffe et al. 2010), and may function as a potential buffer against stigma (Cole et al. 1997; Pryor et al. 2004). However, concealment itself is generally associated with impediments to health and wellbeing, like delayed medical treatment, incomplete medical history, and reluctance to seek preventive care (Bernstein et al. 2008; Dean et al. 2000; Eaton et al. 2015; Glick & Golden 2010; Millett et al. 2012; Qiao et al. 2018; Radcliffe et al. 2010).

For MSM, understanding health-seeking behavior is paramount, in part because their HIV incidence remains disproportionately high (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] 2018; Prejean et al. 2011). Furthermore, engagement of MSM in efficacious biomedical and behavioral HIV prevention remains consistently low (Beyrer et al. 2012; CDC 2014; Crepaz et al. 2006; Hammack, Meyer, Krueger, Lightfoot, & Frost 2018; Khanna et al. 2014; Miller et al. 2013; Singh et al. 2014; Sullivan et al. 2012). For example, five years after approval by the Food and Drug Administration, only 4% of MSM had engaged in pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) (Hammack et al., 2018), and while engagement has since increased (Finlayson, Cha, Xia, Trujillo, Denson, Prejean, et al.) retention continues to be sub-optimal (Chan et al. 2019). One possible impediment to health seeking among MSM is stigma toward the sexual behavior most associated with HIV transmission, anal sex, which is both prevalent and highly stigmatized among both MSM and heterosexual populations (Baggaley et al. 2010; Carter et al. 2010; Heywood & Smith 2012; McBride & Fortenberry 2010). Indeed, both MSM and heterosexuals conceal aspects of anal sexuality, like receptive positioning and desire for pleasure, in part to prevent maltreatment (McDavitt & Mutchler 2014; Quinn et al. 2019; Ravenhill & de Visser 2018; Roye et al. 2013). Among those who do disclose this sexual behavior, stigma still limits health in structural ways beyond the reach of their immediate social interactions. For example, anti-sodomy laws have likely delayed research on anal sexuality (Begay et al. 2011; Kelley et al. 2016; Kelvin et al. 2009) despite its public health relevance across populations (Baggaley et al. 2010; Dosekun & Fox 2010; O’Leary et al. 2016). Likewise, sex education rarely includes information about anal physiology and sexual functioning (Kubicek et al. 2010), thereby increasing vulnerability to physical and psychological harm during intercourse (Duby, Hartmann, Mahaka, et al. 2015; Duby, Hartmann, Montgomery, et al. 2015; Kubicek et al. 2010; McDavitt & Mutchler 2014; Middelthon 2002).

Theoretical Framework

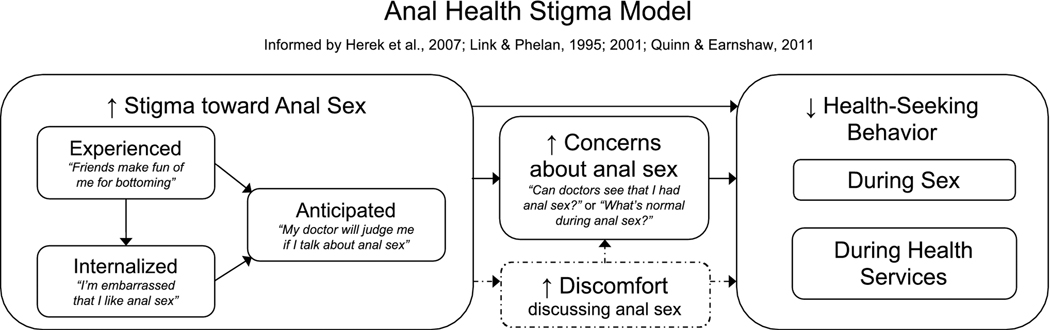

We sought to understand stigma toward anal sexuality and its implications for health seeking, as a formative step toward quantifying its relation to HIV prevention among MSM. We developed a preliminary conceptual model (Figure 1, solid lines), based on the literature and a consolidation of theories related to sexual stigma (Herek et al. 2007), fundamental causes of disease (Link & Phelan 1995; 2001), and concealable stigmatized identities (Quinn & Earnshaw 2011). As a fundamental cause of disease, stigma includes the power to devalue targeted people and thereby produce multiple risk factors of disease further upstream from a person’s most proximate factor, in this case, individual sexual behavior (Link & Phelan 1995; 2001). Concealable stigmatized identities are devalued social identities or attributes, like sexual behavior, that can be kept concealed from others (Quinn & Earnshaw 2011), with potentially distinct effects of experienced, internalized, and anticipated forms of stigma on health-related behavior (Earnshaw et al. 2013). Additionally, we posited that the absence of sex education and information about anal sexuality may contribute to questions and psychological anxieties about sexual behavior (i.e., sexual concerns) which may then mediate the relationship between stigma and inhibited discussion and health seeking. Our aim was to examine the model empirically through qualitative interviews and then to revise the model, after qualitative analyses, in order to inform an eventual statistical evaluation of the model’s constructs and associations.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model describing elements of anal sex stigma, subsequent elevated sexual concerns, and health-seeking behavior, including HIV-related behavior. Solid lines portray a preliminary conceptual model, prior to data collection. Dashed lines indicate a revision informed by qualitative inquiry, to include discomfort discussing anal sexuality.

METHOD

We began by conducting a literature review related to stigma, concealment, and anal sexuality. We then developed the preliminary conceptual model described above, hypothesizing how these constructs might relate to one another. To explore the relevance of our conceptual model to the lived experiences of MSM, we conducted one-time interviews with key informants in the field of MSM health followed by one-time interviews with MSM participants. Procedures were approved by the University of Washington, with continued analyses approved by the New York State Psychiatric Institute.

Participants

We interviewed a total of 10 key informants (KI) and 25 MSM participants.

Key informants were recruited through community-based organizations, research groups, clinical practices, and book authors whose public profiles reflected knowledge of MSM sexual health. Selection for interviews was purposive and aimed to reflect racial, ethnic, age, geographic, and occupational diversity.

To encourage inclusion of MSM concerned about concealment of their sexual identity and behavior, we recruited online through announcements via email listservs, community-based organizations, and social media. Screening, consent for interviews, and demographic questionnaires were administered through an online survey hosted by the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington (Qualtrics 2017).

Of 165 screening survey visitors, 89 met eligibility: cisgender male; living in the U.S.; English speaking, reading, and writing; 18 years of age or older; with at least one male anal sex partner in the past year, as reported through an online demographic survey. “Anal sex” could involve any form (i.e., “any sexual contact with the ass, like touching, licking or penetration”). Participants could request an online chat rather than a telephone interview. Seventy-five men from 21 states and the District of Columbia completed demographic and contact information questions. From these, we purposively sampled 25 MSM who collectively reflected diversity in age, geography, socioeconomic status, medical engagement (no vs. yes for primary care provider), number of past year anal sex partners, HIV status (including use of PrEP), racial and ethnic diversity, and presumed interest in greater anonymity (indicated by requests for online chat).

Interview Procedures

Interviews lasted approximately 1 hour and were conducted by the first author (BAK). Key informant interviews (5 phone, 5 in-person) were conducted in December 2015. All MSM interviews (17 phone, 6 online chat, 2 both formats) were completed in March and April 2016. Participants were allotted a raffle entry to win one of three $50 gift certificates.

Qualitative Inquiry

Interview guides (summarized in Table 1) allowed pre-existing concepts, theories, and findings from this model to inform components of the interview, consistent with Grounded Theory (Strauss & Corbin 1994) and causation coding (Miles et al. 2019; Saldana 2015).

Table 1.

In-depth interviews related to stigma, concealment and health seeking

| Key Informants | Professional background, including geographic and population diversity |

| Anal sexuality (e.g., “When MSM hear ‘anal sex,’ what are their first responses? What’s on the positive side? And the negative side?”) | |

| Concerns among MSM (e.g., “If you had to list all of the questions or concerns that men have about anal sex, what would be on that list?”) | |

| Influence of concerns on sexual behavior and communication (e.g., “How do you think that might affect a guy?”; “Is this at all related to HIV? If so, how?”) | |

| Feedback on conceptual model (e.g., “What’s not there that should be?”) | |

| MSM Participants | Positive experiences with anal sex (e.g., “What made that experience stand out to you?”) |

| First experiences (e.g., expectations; surprises; somatic, emotional and cognitive reactions) | |

| Recent experiences (e.g., preferences, sources of pleasure, negatively-valenced experiences) | |

| Questions about anal sex (e.g., specific questions, concerns, worries; changes over time; concerns of other MSM) | |

| Sources of information, including pornography and peers | |

| Behavioral responses during sex (e.g., efforts to increase pleasure; influences of sexual concerns, including but not limited to HIV/STIs) | |

| Stigma (e.g., maltreatment; facilitators and inhibitors of disclosure; intersectionality; beliefs about anal sex) | |

| Behavioral responses in healthcare (e.g., relationships with providers; disclosure; anticipated responses) | |

| Additional topics (e.g., “What’s one question you’d like me to ask other men?”) | |

For key informants, our interview guide (Supplement 1) asked how MSM experience and perceive anal sexuality and, at the end of each interview, a request for guidance to revise our preliminary conceptual model to better reflect community experience and knowledge. This feedback then guided development of an interview guide for MSM participants (Supplement 2), to query their perceptions of how they and other people (e.g., peers, sex partners, family, health workers) think, talk, and act about the subject, and how this influences their own thoughts and behavior.

Data Management and Analyses

After each MSM interview, the first author (BAK) wrote a debriefing report to capture reflexivity statements, memorable content, emerging themes and how these themes might support or refute findings from preceding interviews (Simoni et al. 2019). Given that the first author conducted all interviews, we used two approaches to constrain the potential effects of bias. First, a larger research team periodically discussed the debriefing reports, allowing for alternative interpretations to arise. Additionally, the senior author (JMS) periodically reviewed recordings, and suggested additional topics to probe as well as ways to balance curiosity about confirming emergent themes from previous interviews with openness to new and distinct content from future interviews.

The first author developed an initial codebook based on the interview guides and themes documented in the debriefing reports. The first author then collaborated with an honors undergraduate. This student prepared for qualitative inquiry by reading a literature review, the debriefing reports, and an initial codebook. These two coders then double-coded 10 percent of transcripts, iteratively allowing for clarification of existing codes, the addition of new codes, and resolution of discrepancies by consensus. The first author completed coding in Atlas.ti 7.5.2 (Muhr, 2012), then examined themes by diagramming excerpts (Maietta et al. 2018) in mindmapping software (MindNode) to visualize relationships between constructs, including excerpts that supported and refuted relationships (Miles et al. 2019).

RESULTS

Participants

Demographic characteristics of key informants and MSM participants are detailed in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of key informants (n = 10)

| n (%) |

|

|---|---|

| Age in years M (SD) | 44.6 (12.6) |

| Male gender | 9 (90) |

| Professional role* | |

| Counselor or therapist | 4 (40) |

| Medical provider | 3 (30) |

| Sex educator | 6 (60) |

| Business owner | 1 (10) |

| Activist | 3 (30) |

| Advocate | 3 (30) |

| Researcher/Community Engagement | 3 (30) |

| Income | |

| Below $15,000 | 1 (10) |

| $45,000 - $59,999 | 1 (10) |

| $60,000 - $74,999 | 2 (20) |

| $90,000 or more | 6 (60) |

| Education | |

| Some College | 1 (10) |

| 4-year College Degree | 1 (10) |

| Master’s Degree | 4 (40) |

| Doctoral Degree | 3 (30) |

| Professional Degree (MD) | 1 (10) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Black or African American | 2 (20) |

| Latino (no racial group specified) | 2 (20) |

| Latino (White or Caucasian) | 1 (10) |

| White or Caucasian | 5 (50) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Gay | 7 (70) |

| Bisexual | 1 (10) |

| Queer | 1 (10) |

| Heterosexual (straight) | 1 (10) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 3 (30) |

| Dating (not living together) | 2 (20) |

| Married | 4 (40) |

| Married, Polyamorous | 1 (10) |

| Housing | |

| A house, apartment, or condo I own | 3 (30) |

| A house, apartment, or condo I rent | 5 (50) |

| Someone else’s house, apartment, or condo | 2 (20) |

Multiple responses allowed

Table 3.

Demographic characteristics of MSM (n = 25)

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Age in years M (SD) | 34.0 (9.1) |

| Income | |

| Below $15,000 | 2 (8.0) |

| $15,000 - $29,999 | 7 (28.0) |

| $30,000 - $44,999 | 11 (44.0) |

| $45,000 - $59,999 | 3 (12.0) |

| $60,000 - $74,999 | 1 (4.0) |

| $75,000 - $89,999 | 1 (4.0) |

| Education | |

| Some High School | 1 (4.0) |

| Some College | 6 (24.0) |

| 2-year College Degree | 5 (20.0) |

| 4-year College Degree | 8 (32.0) |

| Master’s Degree | 4 (16.0) |

| Doctoral Degree | 1 (4.0) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Asian or Asian American | 2 (8.0) |

| Black or African American | 9 (36.0) |

| Latino (Black or African American) | 2 (8.0) |

| Latino (White or Caucasian) | 4 (16.0) |

| White or Caucasian | 8 (32.0) |

| HIV status | |

| Never tested | 1 (4.0) |

| Most recently tested seronegative | 17 (68.0) |

| Prescribed PrEP | 4 (22.2) |

| HIV seropositive | 7 (28.0) |

| Undetectable viral load | 6 (85.7) |

| Sexual orientation | |

| Gay | 21 (84.0) |

| Bisexual | 1 (4.0) |

| Two-spirit | 1 (4.0) |

| Queer | 2 (8.0) |

| Relationship status | |

| Single | 7 (28.0) |

| Casually dating several people | 3 (12.0) |

| Boyfriend or girlfriend | 12 (48.0) |

| Partner or lover | 2 (8.0) |

| Married/civil partner/commitment ceremony | 1 (4.0) |

| Open relationship or not sure* | 7 (46.7) |

| Sexual position preference | |

| ‘Bottoming’ | 7 (28.0) |

| ‘Topping’ | 2 (8.0) |

| Versatile’ | 15 (60.0) |

| No preference | 1 (4.0) |

| Number of PY anal sex partners | |

| 1 | 6 (24.0) |

| 2–5 | 5 (20.0) |

| 6–10 | 2 (8.0) |

| 11–15 | 4 (16.0) |

| 16–20 | 2 (8.0) |

| 21–25 | 1 (4.0) |

| 26 or more | 5 (20.0) |

| Housing | |

| Own | 5 (20.0) |

| Rent | 19 (76.0) |

| Someone else’s home | 1 (4.0) |

| Primary care physician | 21 (84.0) |

Among those reporting a “Boyfriend or girlfriend”, “Partner or lover,” or “Married/civil partner/commitment ceremony”

Qualitative Findings

Results from our qualitative inquiry describe major components of our conceptual model: experienced, internalized, and anticipated forms of stigma; anal sex-related questions and concerns; concealment of anal sexuality; and health-seeking behavior both during sex and in health services.

Experienced Stigma: “A lot of shaming that goes on in the community”

Participants reported characterizations of anal intercourse as inherently unhealthy and conflated with stigma toward homosexuality, but also distinctly taboo compared to other same-sex behaviors, like oral sex.

[T]here are lots of people who believe that every man has given or received a blowjob but once you cross the anal divide, you’re into a whole different place sexually. [KI-06/63yo/Black/Advocate]

Several reported “bottom shaming,” that MSM who vocalize their desire and pleasure specifically for receptive sex experience slander – even by fellow MSM, with a “slur” like “used goods,” “trash,” “such a bottom,” “whore,” and someone to “watch your man around.” Indeed, insertive-only MSM also disparaged receptive sex.

I’ve had patients say, “I’m not gonna let somebody do that to me.” Do that to you?!? What does that mean “Do that to you”? Almost like this is a bad thing that’s happening. So, you’re being an insertive partner with the person you’re having sex with and that’s okay – but you don’t feel like it would be okay for them to do that to you. Somehow there’s something somehow going on here that may not necessarily be kosher, y’know? [KI-01/58yo/White/Healthcare]

Respondents also noted the omission of information about anal sexuality. For the most part, participants felt left to “learn along the way,” lacking specific guidance or education.

People … [use] what they know from their friends, which may or may not be correct … you see people kind of are shocked at what they thought was right. … I feel as though there really isn’t a place where I can say, okay, this is everything about anal sex. And this is how to go about that. [MSM-03/23yo/Black]

[W]hen I’ve taught my workshop [on prostate stimulation], a lot of them are surprised by how little they know. Like a lot of them think they know more than they actually do. … “Yeah, I’ve been having anal sex for years and I had no idea about these things.” Like they didn’t know where their prostate is or they didn’t understand that the internal anal sphincter is controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system so your moods and your emotions and your feelings affect its ability to relax. They just didn’t have that information. [KI-02/45yo/White/Healthcare]

Internalized Stigma: “[I]t still seems a little weird”

Respondents noted that experienced stigma could linger beyond specific encounters or exposures as internalized shame – cumbersome and difficult to shed.

I still feel awkward. I don’t necessarily express that to my partner, but I definitely feel a little awkward, and I think that’s just because of what I mentioned before with cleanliness and just – the whole idea of anal sex, yes, I have it, but it still seems a little weird, and I’m guessing that’s just cultural things I grew up [with]. I was Catholic. I was a Boy Scout and that type of thing growing up. I assume, somewhere, I still have that guilt in the back of my head. [MSM-14/32yo/White]

One participant [MSM-10/32yo/Black Latino] commented that he may never let go of his mental discomfort related to anal sex. When asked what he thought the interviewer might think about this comment, he quickly emphasized how unique and alone he felt in his struggle: “That I’m a weirdo. That you’ve never heard anyone talk like that about engaging in sex. Like I may be like this unsound data point in your study.”

Anticipated Stigma: “‘People are gonna be looking at me crazy’”

Participants anticipated that denigration toward anal sex differed to some degree from stigma toward sexual orientation. The participant quoted above sought medical attention in his mid-teens for a painful fissure that followed his initial, unlubricated efforts at anal sex. His partner decided not to accompany him to the appointment, to avoid being “identified” for maltreatment himself, specifically for his contribution during anal sex.

[My partner] was like, “If I go in there with you, they’re gonna know I did that to you, and then people are gonna be looking at me crazy.” So it was like this whole thing like he felt like he was gonna be outed again or something. [MSM-10/32yo/Black Latino]

A key informant seemed to confirm this as a generalizable experience, sharing that health workers themselves are often not skilled enough to address or willing to discuss anal health, which patients can detect, internalize and then anticipate in the future.

I think patients know that the majority of healthcare providers don’t want to deal with their bottoms. I have so many providers that will send their patients to me just for a rectal exam or to do a swab. An anal swab which takes 30 seconds. They don’t want to do it. They don’t want to go near it. When I was in surgery [training] and somebody had like a perianal abscess or they had a problem with their butt, the surgeons would be rock-paper-scissoring over who had to go down and deal with it because nobody wanted to. And I think that the patients can sense that. And so it creates a kind of baseline stigma there, “Oh, God, nobody wants to deal with my ‘you-know’.” You associate it with poop and smelling and farts and all of the above – and then if you get a sense that your primary care [provider] or somebody else doesn’t want to deal with it, it makes you feel like there’s something wrong with that.” [KI-04/34yo/White/Healthcare]

Sexual Concerns: “Is this normal to happen during anal sex?”

Along with experienced, internalized, and anticipated stigma, respondents harbored worrisome questions about anal sex that they wished they could answer but were ambivalent about disclosing to other people. The absence of reliable, accurate educational resources seemed to reinforce anxiety and deepen men’s internalization of stigma.

[W]hat’s supposed to go on during anal sex? Like, is that possible? Is this a thing that’s normal? Oh, I saw a secretion. Or I saw this come out after I got done preparing for anal sex, or like this happened while I was using my enema or my Shower Shot [a rectal cleaning device] or whatever it may be. Is this normal to happen during anal sex? [MSM-03/23yo/Black]

When I was younger, and before I even completely understood more about my personal body, I would be freaked out for two or three days [after receptive sex]. Or, I’d feel like if I used the bathroom, I was going to re-infect myself with feces and stuff, because I’ve teared a hole in there … Now I know that that has not happened, and I’ve had enough sex to know the likeliness of that happening is not likely, but no one ever educated me or told me, before I started this process, that those things might jump out and stress me out or be concerns of mine. [MSM-04/36yo/Black]

A few noted that HIV messaging characterized anal sex solely as a risk factor, reinforcing negative connotations and precluding more holistic discussion of additional concerns, like pleasure and emotional well-being.

I feel like so often, anal health, especially for gay men, kind of gets left out of the equation, and we act like the only thing going on for gay men is HIV, which is not the case. … We focus on, “Oh, your ass is so weak…” We never [focus on] the good things that come from your ass, the pleasure that comes from it, the enjoyment that happens. [MSM-08/29yo/Black]

When we talk about anal health, it’s usually always the same old, same old. “Make sure you use condoms, make sure you’re not bleeding.” But I think we don’t go into the emotional standpoint and the repercussions of what can happen when things don’t work out right. [MSM-05/25yo/Black]

Concealment: “[They] don’t go anywhere with their questions”

Respondents described how stigma discourages discussion of sexual behavior and sexual concerns, confining conversations to a very limited audience.

I know so many guys who don’t go anywhere with their questions. And they have the questions and it just sits there with them. And I’m guilty of that too. [KI-10/29yo/Latino/Activist]

[A] lot of my friends say, “You’re the only person I talk to this about.” … I hear a lot of men who do not talk about the specifics of anal sex. They talk about doing it or having it done. But not really discussing their discomforts, their fears, their worries, how they could maybe enjoy it more. [KI-07/33yo/Latino/Healthcare]

Concealment even manifested during interviews. One younger participant (MSM-20/26yo/Asian), who had experienced oral-anal sex but never intercourse or a romantic relationship, initially concealed from the interviewer an aspiration to delay penetration until he could meet a lifelong partner, anticipating ridicule (“I just feel like you might laugh”). Another participant [MSM-01/29yo/Black] began his phone interview by describing himself as “very straightforward.” Yet when later asked to share his approach to preparing for anal sex, or recommendations for others, he repeatedly shied away from disclosure. He said that his approach was “very, very simple,” but too personal to specify during the interview – despite that he had already disclosed living with HIV, his involvement in sex work, and his versality with regard to anal sex.

Among men who do talk about anal sex, many – regardless of sexual positioning – appear to truncate or circumscribe what they disclose, both to heterosexual contacts and other MSM, particularly their non-infectious disease concerns, like desire for less discomfort and emotional connection. One [MSM-14/32yo/White] described an amalgam of anticipated and internalized stigma – specifically toward sexual behavior, not sexual orientation – that inhibited discussion with his heterosexual friends: “[E]ven if they’re supportive of my being gay, which most of my [straight] friends are, I would still feel as if I’m making them uncomfortable if I’m talking with them about sexual experiences.” He could only really imagine discussing his concerns about anal sex with his one or two gay friends and, even then, under specific relaxed conditions, like while listening to a sex-related podcast on a road trip. Still, he added, “I would also judge how they were responding if I were to have that conversation with them and how much to share or not to share.”

Health Seeking during Sex: “I bottomed because I was afraid to even discuss the idea”

Many MSM reported learning to have anal sex “by trial and error,” independently echoing that the absence of guidance to mitigate sex-related concerns left them vulnerable to harm during sexual encounters. One MSM [MSM-18/56yo/Black] relayed another’s problematic use of sexual aids: “I had this one friend that used to frighten me because he would use Preparation H [hemorrhoidal cream] as a lubricant.” A different friend used to “double bag … [with] two condoms instead of one,” intending to mitigate his concern about contact with feces but unwittingly increasing the chance that both condoms might break. Another participant [MSM-02/29yo/Black] felt he had been “doing it wrong” even 4 years after his sexual debut. He reported using a lubricant he did not like, “taking someone pounding” him even though anal sex hurt, and trading his greater concern about “poop on my mind” for a lesser, albeit “horrible,” feeling “like I was raw inside” from over-the-counter enemas.

A lack of reliable, accurate information about anal physiology and sexual response – and reliance on sexual partners and pornography rather than sex education – appeared to contribute to internalized expectations of discomfort and pain, whether physical or psychological. These harms seemed almost normative: expected, tolerated, and addressed to some extent, but not prevented entirely.

If I was on the giver with three different people, and they all said that it hurt and now my current partner and I, I want to try being on the receiving side, I have this expectation that it’s going to hurt. Or that line from so much cheesy porn, the pain that turns into pleasure. There’s this sort of expectation that it’s supposed to hurt and you’re just supposed to either endure it or get over it. [KI-17/45yo/White/Healthcare]

Several described feeling naïve during their first experiences, relying on partners to determine safety, only learning to advocate sexually to prevent discomfort after aversive consequences like physical damage, or contracting HIV or other sexual transmitted infections.

It was kinda like discovering for myself, so it was like as being with my partner, I wanted to please him, but I really didn’t have any foresight on using more lubrication and like taking my time with it, so then the ripping occurred. [MSM-10/32yo/Black Latino]

I remember the first time I had gay sex I bottomed because I was afraid to even discuss the idea that anal sex could be something that could be navigated and talked about. / It was more you tell me what I am supposed to do. There was definitely no conversations about protection and feeling like I had anyone I could talk about those types of things with [MSM-20/41yo/White]

Even after gaining more experience, respondents described emotional investments in not interrupting sex, urges that seemed related to stigma, sexual concerns, and concealment. One [MSM-14/32yo/White] assumed condoms themselves contained sufficient lubricant and preferred not to add any himself, in part to conceal his discomfort from partners. Some felt that the more investment in preparation for penetration, the more investment in not interrupting sex once it happens, even if the sex is uncomfortable, given the effort and deprivation involved in getting ready for penetration.

[Bottoms have] had to go on their dick diet [not eating or eating limited foods]. They’ve had to irritate their body [with enemas], and now it’s a role of theirs to have sex tonight, so all that hard work that they put into it don’t go to waste. And then, if it doesn’t happen, you feel twice as empty, like twice as rejected, because you put such force and effort, and then nothing comes of it. [MSM-04/36yo/Black]

Health Seeking in Health Services: “I don’t want to go to a doctor unless I’m sure it’s an issue.”

Stigma toward anal sexuality – and related discomfort discussing anal sex issues, whether on the part of clients or providers – prompted participants to avoid, delay or discontinue health care. Some shied away because, as one [MSM-09/27yo/White] noted, “There is some something a little bit more personal [about anal health], so I don’t want to go to a doctor unless I’m sure it’s an issue.” Others more specifically worried they might magnify social discomfort if they posed sex-related questions, either by humiliating themselves or by humiliating medical personnel who lack expertise.

No one, other than my current doctor, has ever talked about [anal sex] in any more terms, other than, you know, are you the receptive or the insertive partner. … [A]ll of my doctors have been straight. Straight people don’t really know about sex in those terms, so it’s kind of hard for them to even talk about it, even in a clinical setting. [MSM-12/49yo/Black]

Some men reported willingness to discuss their sexual concerns with health workers, qualified by a need to “vet” providers by first coming out as gay or assessing another sensitive topic – like gay marriage or “topical things in the news” – that might reveal prejudice, then girding themselves to disclose. This resolve, however, was couched in reticence and aversion.

If I just say “I’m gay” to my doctor and … get a weird or non-response then that next step [sharing about anal sex] … takes a lot more of you just sucking it up and doing it. … If you’re already getting signals of like – not that it’s going to fall on deaf ears, but it’s going to fall on ears that don’t know what to do with the information – you’re like, “Oh, this next part is going to really suck.” [MSM-16/28yo/White Latino]

Even MSM who report comfort disclosing their sexual orientation may experience similar inhibition when discussing anal sexuality, including with practitioners who are MSM themselves.

It’s like we talk about everything and right when we’re about to go back [for an anorectal exam] – and I do it too, as a patient myself. … You think if you say it really quick at the end, like it didn’t happen. So I get a lot of that too. “By the way, I’m bleeding everywhere after I’m bottoming.” I’m like, “What? That should’ve been the first thing that you told me.” [KI-04/34yo/White/Healthcare]

Stigma also appeared to interfere with access to health promotion materials. One [MSM-05/25yo/Black] noted that his “health department” provided free lubricants, but in insufficient quantities and with brands he found irritating. This required purchases that his more concealed partners typically relied on him to make, because they did not want to be identified as needing those products themselves.

Anal Health Stigma Model

Our results informed refinement of our conceptual model (Figure 1, dotted lines) for our next steps to test associations with HIV-related behavior. The model hypothesizes how stigma toward anal sex might relate to health-seeking behavior, including HIV prevention during sex and in health services. We originally conceived of concealment as a behavior within healthcare settings. However, respondents reported discomfort with disclosure and the urge to hide aspects of anal sexuality, including with otherwise supportive friends, family, and sexual partners, as well as medical providers – and even after sexual orientation and sexual behavior were already apparent. This observation suggests that in future efforts to quantify associations between these constructs we should consider discomfort discussing anal sexuality, rather than outright concealment, as a potential mediator between stigma and engagement.

DISCUSSION

Analysis of interviews supported links between different forms of stigma (experienced, internalized, anticipated), sexual concerns, concealment of these concerns and sexual behavior, and health-related responses to stigma during sex and within medical settings. Overall, the triad of stigma discourages communication about anal sexuality and this concealment appears to be normative, isolating MSM from discussion of their sexual concerns, despite that these concerns were commonly endorsed. Stigma and concealment, in turn, impede health-seeking behavior by producing vigilance about the risks of communication both during sexual encounters and while seeking medical services, when stigma might be enacted or sexual concerns inadvertently revealed and punished.

Men required time to unencumber themselves from stereotypes and the anticipation of stigma, some with more efficiency and effectiveness than others. This suggests, optimistically, that MSM do find ways to mitigate the effects of stigma. For example, they may learn from peers and “trial and error” to use products and practices that minimize pain and increase pleasure, as other researchers have noted (Kubicek et al. 2010). Still, stigma lingered in health care settings, even longer than participants would expect and even with gay-friendly providers and anal health specialists. Participants described how this stigma informed their reticence to share relevant, health-related sexual concerns and sexual behavior, unless absolutely necessary. In addition, even for men unencumbered by urges to conceal their sexual behavior, clinicians’ lack of knowledge, skill, and motivation, for example to perform anorectal examinations, may effectively limit men’s ability to benefit from health services, even on topics they would like to address.

The finding that stigma impedes engagement in health-seeking behavior by encouraging delays in disclosure is consistent with findings on stigma toward other concealable social identities, like sexual orientation and HIV status (Institute of Medicine 2011; Smit et al. 2012) and, to some extent, qualitative findings among MSM about disclosure of specific anal sex practices like receptive positioning (e.g., Quinn et al. 2019; Ravenhill & de Visser 2018). Respondents generally wanted to find knowledgeable providers who might accurately respond to their questions about anal sexuality. However, they also considered a high threshold for medical consultation and disclosure. Although our model now conceives of discomfort as a mediator, we should be cautious and consider that the effects of discomfort are not just in one direction, from stigma to engagement. In fact, this urge to conceal may reinforce stigma (Pachankis 2007). At the same time, behavior within health care is malleable and this leads us to consider that stigma toward anal sexuality may be a future target for interventions to mitigate sexual stigma (Chaudoir et al. 2017), particularly in medical settings (Mayer et al. 2012).

Our finding that stigma toward anal sexuality adds to a sense of devaluation beyond simply stigma toward sexual orientation is consistent with a growing literature on intersectionality and health (Richman & Zucker 2019) and recent quantified associations between sexual stigma and health behavior among MSM (Rendina et al. 2018). Across a diverse set of social identities and experiences, MSM are subjected to syndemic conditions that burden their health, including their HIV risk (Halkitis et al. 2013). A particularly stubborn, increasing level of incident HIV continues each year among subpopulations of MSM, notably young MSM and racial and ethnic minority MSM, and in specific high-stigma regions like the southern U.S. (CDC 2016). Data already suggest that sexual stigma functions in magnified and detrimental ways for racial minorities, for example impeding prescription of PrEP for Black MSM (Calabrese et al. 2013). Data also suggest that concealment of sexual behavior and orientation vary by racial identification (Bernstein et al. 2008; Eaton et al. 2015; Glick & Golden 2010; Millett et al. 2012; Radcliffe et al. 2010). Our findings justify a deeper look at the intersection of sexual stigma with racism and other forms of social devaluation, as the effects of stigma toward anal sexuality may function differently across social identities in ways that could inform assessment and intervention.

We also found that MSM harbor a set of worrisome and unaddressed anal sex concerns that, if discussed, might prevent harmful health sequelae. Some concerns have been documented elsewhere, for example about contact with feces and about damage to physiological functioning (Agnew 2000; Collier et al. 2015; Damon & Rosser 2005; Sandfort & de Keizer 2001). These concerns may encourage health-seeking behavior if they reach a threshold for disclosure, as they did for respondents who required medical intervention – after damage had already occurred. But waiting for MSM to bring their concerns to health care providers late in the course of illness misses an opportunity for earlier prevention (Middelthon 2002). Late diagnosis also artificially constrains health-related conversations to the most dire sequelae, thereby burdening the public portrayal of anal sex with confirmation bias of harm, as others have noted (Morin 2010).

It may not be surprising that MSM themselves conflate anal sex with its potential harms (Middelthon 2002), given public health messaging that focuses on anal sex narrowly, as a risk factor for HIV and infectious disease (Bourne et al. 2013). In our sample, this social context appeared to predispose men to accept harmful consequences as natural and inherent to anal sex, rather than a result of hidden social processes (Meyer 2003) that, for example, have devalued education about anal sexuality except as it pertains to HIV and STI prevention. This acceptance of harm as inevitable appears to reduce the likelihood that MSM entertain the possibility of more healthful experiences, in turn diminishing their motivation to share sexual concerns that might be amenable to change, for example with the help of potentially supportive sexual partners, social contacts, and health workers. Quantifying a set of concerns and assessing men’s ambivalence about addressing these concerns could guide the development of practitioner training and health education materials to encourage more candid discussion and intervention. Indeed, addressing gaps in knowledge about anal sexuality would align with men’s own priorities (Hooper et al. 2008) – and could promote earlier engagement in both HIV prevention and health-seeking more generally (Bourne et al. 2013), before harm accumulates. Shared decision making, which has empirical support (Durand et al. 2014), could provide a model for how to intervene.

Our study should be considered in the context of several limitations. We relied on purposive sampling and expect that selection bias limits our findings. Those most interested in concealment are also likely the least interested in discussing anal sex. We proactively addressed this limitation by offering an additional layer of anonymity through online chat and telephone interviews. It is perhaps all the more evident that stigma and concealment are important to assess quantitatively because our participants disclosed important health-related themes but were also, at times, reluctant to disclose aspects of their sexual behavior. Prevalence estimates of anal sex appear to be underestimated when participants’ sense less anonymity (Baggaley et al. 2010), likely attributable to reporting bias. Development of assessment measures that measure stigma and sexual concerns in a more anonymous fashion than in-depth interviews, for example anonymously online, could better establish the prevalence and correlates of the experiences we heard in our sample.

In sum, experiences of stigma, internalization of these experiences, and anticipation of some form of their reenactment appear to guide decisions about concealment of sexual behavior and sexual concerns both in clinical settings and between MSM during anal sex. This has implications for health-seeking behavior and warrants an effort to quantify these phenomena and their potential associations with health outcomes, like HIV, that disproportionately affect MSM. Anal health is, of course, not limited to HIV and anal sex is practiced around the world not just by MSM (Baggaley et al. 2010; Boily et al. 2009; McBride & Fortenberry 2010). Formative and theory-informed research on measurement and associations might therefore reveal opportunities to intervene on a manifestation of stigma that has likely functioned to some extent across populations as a fundamental cause of disease (Link & Phelan, 2001), even before the onset of the HIV epidemic (Agnew 1985).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to key informants and participants for their willingness to share their experiences and to colleagues in HIV services for their dedication to the mitigation of health disparities and, in this particular study, their essential contributions to recruitment of men of color. We thank the first author’s dissertation committee members Drs. Kevin King, Shannon Dorsey, and Steven Goodreau as well as research consultants B. R. Simon Rosser and Stefan Baral. We would also like to thank those who aided in project conception and implementation at the University of Washington, including Megan Ramaiya, Kira Brist and Santino Camacho and Drs. Kimberly Nelson and Joyce Yang. This research project was supported by the National Institutes of Health (T32AI07140, PI: Sheila Lukehart; T32MH019139, PI: Theodorus Sandfort; and P30MH43520, PI: Robert Remien) and the Bolles Graduate Fellowship through the Department of Psychology at the University of Washington.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards with approval by the University of Washington Human Subjects Division (Study 50334) and the Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute (Study 7627) affiliated with Columbia University. This article does not contain any studies with animals performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent: Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study through an online information statement.

REFERENCES

- Agnew J. (1985). Some anatomical and physiological aspects of anal sexual practices. Journal of Homosexuality, 12(1), 75–96. doi: 10.1300/J082v12n01_04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agnew J. (2000). Anal manipulation as a source of sexual pleasure. Venereology, 13(4), 169. [Google Scholar]

- Baggaley RF, White RG, & Boily MC. (2010). HIV transmission risk through anal intercourse: systematic review, meta-analysis and implications for HIV prevention. International Journal of Epidemiology, 39(4), 1048–1063. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyq057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein KT, Liu K-L, Begier EM, Koblin B, Karpati A, & Murrill C. (2008). Same-sex attraction disclosure to health care providers among New York City men who have sex with men: implications for HIV testing approaches. Archives of Internal Medicine, 168(13), 1458–1464. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.13.1458 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyrer C, Sullivan PS, Sanchez J, Dowdy D, Altman D, Trapence G, et al. (2012). A call to action for comprehensive HIV services for men who have sex with men. Lancet. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61022-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boily M-C, Baggaley RF, & Mâsse B. (2009). The role of heterosexual anal intercourse for HIV transmission in developing countries: Are we ready to draw conclusions? Sexually Transmitted Infections, 85(6), 408–410. doi: 10.1136/sti.2009.037499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourne A, Hammond G, Hickson F, Reid D, Schmidt AJ, & Weatherburn P. (2013). What constitutes the best sex life for gay and bisexual men? Implications for HIV prevention. BMC Public Health, 13, 1083–1083. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, & Dovidio JF. (2013). The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): Assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS and Behavior, 18(2), 226–240. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0675-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter JW Jr, Hart-Cooper GD, Butler MO, Workowski KA, & Hoover KW. (2014). Provider barriers prevent recommended sexually transmitted disease screening of HIV-infected men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 41(2), 137–142. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter M, Henry-Moss D, Hock-Long L, Bergdall A, & Andes K. (2010). Heterosexual anal sex experiences among Puerto Rican and Black young adults. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 42(4), 267–274. doi: 10.1363/4226710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. (2014). Gaps in care among gay men with HIV. Retrieved September 26, 2014 from http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2014/HIV-Care-Among-Gay-Men.html.

- CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention). (2016, May 1). HIV in the southern United States. Retrieved February 22, 2019 from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/policies/cdc-hiv-in-the-south-issue-brief.pdf.

- CDC. (2018). HIV and gay and bisexual men. Retrieved February 22, 2019 from https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/group/msm/cdc-hiv-msm.pdf.

- Chan PA, Patel RR, Mena L, Marshall BD, Rose J, Sutten Coats C, et al. (2019). Long-term retention in pre-exposure prophylaxis care among men who have sex with men and transgender women in the United States. Journal of the International AIDS Society, 22(8), e25385. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir SR, Wang K, & Pachankis JE. (2017). What reduces sexual minority stress? A review of the intervention “toolkit”. The Journal of Social Issues, 73(3), 586–617. doi: 10.1111/josi.12233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole SW, Kemeny ME, & Taylor SE. (1997). Social identity and physical health: accelerated HIV progression in rejection-sensitive gay men. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(2), 320–335. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.72.2.320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collier KL, Sandfort TG, Reddy V, & Lane T. (2015). “This will not enter me”: Painful anal intercourse among Black men who have sex with men in South African townships. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(2), 317–328. doi: 10.1007/s10508-014-0365-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, et al. (2006). Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS, 20(2), 143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damon W, & Rosser BRS (2005). Anodyspareunia in men who have sex with men. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity, 31(2), 129–141. doi: 10.1080/00926230590477989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean L, Meyer IH, Robinson K, Sell RL, Sember R, Silenzio VMB, et al. (2000). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health: Findings and concerns. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 4(3). doi: 10.1023/A:1009573800168 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dosekun O, & Fox J. (2010). An overview of the relative risks of different sexual behaviours on HIV transmission. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS, 5(4), 291–297. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a88a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drainoni M-L, Dekker D, Lee-Hood E, Boehmer U, & Relf M. (2009). HIV medical care provider practices for reducing high-risk sexual behavior: results of a qualitative study. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 23(5), 347–356. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duby Z, Hartmann M, Mahaka I, Munaiwa O, Nabukeera J, Vilakazi N, et al. (2015). Lost in translation: Language, terminology, and understanding of penile–anal intercourse in an HIV prevention trial in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. The Journal of Sex Research, 1–11. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2015.1069784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duby Z, Hartmann M, Montgomery ET, Colvin CJ, Mensch B, & van der Straten A. (2015). Condoms, lubricants and rectal cleansing: Practices associated with heterosexual penile-anal intercourse amongst participants in an HIV prevention trial in South Africa, Uganda and Zimbabwe. AIDS and Behavior, 20(4), 754–762. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1120-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand MA, Carpenter L, Dolan H, Bravo P, Mann M, Bunn F, & Elwyn G. (2014). Do interventions designed to support shared decision-making reduce health inequalities? A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(4), e94670. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0094670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, & Copenhaver MM. (2013). HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: A Test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS and Behavior, 17(5), 1785–1795. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaton LA, Driffin DD, Kegler C, Smith H, Conway-Washington C, White D, & Cherry C. (2015). The role of stigma and medical mistrust in the routine health care engagement of Black men who have sex with men. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), e75–e82. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finlayson T, Cha S, Xia M, Trujillo L, Denson D, Prejean J, et al. (2019). Changes in HIV preexposure prophylaxis awareness and use among men who have sex with men - 20 urban areas, 2014 and 2017. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 68:597–603. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6827a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glick SN, & Golden MR. (2010). Persistence of racial differences in attitudes toward homosexuality in the United States. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 55(4), 516–523. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181f275e0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. (1963). Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity. New York: Simon & Schuster, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Halkitis PN, Wolitski RJ, & Millett GA. (2013). A holistic approach to addressing HIV infection disparities in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men. American Psychologist, 68(4), 261–273. doi: 10.1037/a0032746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammack PL, Meyer IH, Krueger EA, Lightfoot M, & Frost DM. (2018). HIV testing and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use, familiarity, and attitudes among gay and bisexual men in the United States: A national probability sample of three birth cohorts. PLoS ONE, 13(9), e0202806–11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. (2009a). Sexual Prejudice. In Nelson TN. (Ed.), Handbook of Prejudice, Stereotyping, and Discrimination (pp. 441–467). Hoboken: Taylor and Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. (2009b). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(1), 54–74. doi: 10.1177/0886260508316477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Chopp R, & Strohl D. (2007). Sexual stigma: Putting sexual minority health issues in context. In Meyer IH & Northride ME. (Eds.), The Health of Sexual Minorities: Public Health Perspectives on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender Population. New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Cogan JC, & Gillis JR. (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, (2)1, 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Heywood W, & Smith AMA (2012). Anal sex practices in heterosexual and male homosexual populations: A review of population-based data. Sexual Health, 9(6), 517–526. doi: 10.1071/SH12014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper S, Rosser BRS, Horvath KJ, Oakes JM, & Danilenko G. (2008). An online needs assessment of a virtual community: What men who use the internet to seek sex with men want in Internet-based HIV prevention. AIDS and Behavior, 12(6), 867–875. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9373-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. (2011). The Health of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender People. Washington D.C., National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khanna AS, Goodreau SM, Gorbach PM, Daar E, & Little SJ. (2014). Modeling the impact of post-diagnosis behavior change on HIV prevalence in Southern California men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS and Behavior, 18(8), 1523–1531. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0646-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, Beyer WJ, Weiss G, Iverson E, & Kipke MD. (2010). In the dark: Young men’s stories of sexual initiation in the absence of relevant sexual health information. Health Education & Behavior, 37(2), 243–263. doi: 10.1177/1090198109339993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG & Phelan J. (2001). Conceptualizing stigma. Annual Review of Sociology, 27(1), 363–385. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Maietta RC, Hamilton A, Swartout K, Mihas P, & Petruzzelli J. (2018). Sort & sift, think and shift: Let the data be your guide. Presented at the Qualitative Inquiry Camp, Carrboro, NC. Research Talk, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Mayer KH, Bekker L-G, Stall R, Grulich AE, Colfax G, & Lama JR. (2012). Comprehensive clinical care for men who have sex with men: an integrated approach. Lancet, 380(9839), 378–387. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60835-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McBride KR, & Fortenberry JD. (2010). Heterosexual anal sexuality and anal sex behaviors: a review. Journal of Sex Research, 47(2), 123–136. doi: 10.1080/00224490903402538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDavitt B, & Mutchler MG. (2014). “Dude, You’re Such a Slut!” Barriers and facilitators of sexual communication among young gay men and their best friends. Journal of Adolescent Research, 29(4), 464–498. doi: 10.1177/0743558414528974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKirnan DJ, Bois Du, S. N., Alvy LM, & Jones K. (2013). Health care access and health behaviors among men who have sex with men: the cost of health disparities. Health Education & Behavior, 40(1), 32–41. doi: 10.1177/1090198111436340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meites E, Krishna NK, Markowitz LE, & Oster AM. (2013). Health care use and opportunities for human papillomavirus vaccination among young men who have sex with men. Sexually Transmitted Diseases, 40(2), 154–157. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31827b9e89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer IH. (2003). Prejudice as stress: Conceptual and measurement problems. American Journal of Public Health, 93(2), 262–265. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middelthon A-L (2002). Being anally penetrated: Erotic inhibitions, improvizations and transformations. Sexualities, 5(2), 181–200. doi: 10.1177/1363460702005002003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miles MB, Huberman AM, & Saldana JM. (2019). Qualitative Data Analysis (4 ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WC, Powers KA, Smith MK, & Cohen MS. (2013). Community viral load as a measure for assessment of HIV treatment as prevention Lancet, 13(5), 459–464. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70314-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millett GA, Jeffries WL, Peterson JL, Malebranche DJ, Lane T, Flores SA, et al. (2012). Common roots: a contextual review of HIV epidemics in black men who have sex with men across the African diaspora. Lancet, 380(9839), 411–423. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60722-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morin J. (2010). Anal Pleasure and Health: A Guide for Men, Women, and Couples (4 ed.). San Francisco: Down There Press. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary A, Dinenno E, Honeycutt A, Allaire B, Neuwahl S, Hicks K, & Sansom S. (2016). Contribution of anal sex to HIV Prevalence Among Heterosexuals: A modeling analysis. AIDS and Behavior, 21(10), 2895–2903. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1635-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet NM, Earnshaw VA, Kalichman SC, & Quinn DM. (2013). Internalized stigma and HIV status disclosure among HIV-positive black men who have sex with men. AIDS Care, 25(4), 466–471. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2012.720362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pachankis JE. (2007). The psychological implications of concealing a stigma: A cognitive-affective-behavioral model. Psychological Bulletin, 133(2), 328–345. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.2.328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, et al. (2011). Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS ONE, 6(8), e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502.t005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryor JB, Reeder GD, Yeadon C, & Hesson-McLnnis M. (2004). A dual-process model of reactions to perceived stigma. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 87(4), 436–452. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.87.4.436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qiao S, Zhou G, & Li X. (2018). Disclosure of Same-sex behaviors to health-care providers and uptake of HIV testing for men who have sex with men: A systematic review. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(5), 1197–1214. doi: 10.1177/1557988318784149 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qualtrics. (2017). Qualtrics. Provo, Utah, USA.

- Quinn DM, & Chaudoir SR. (2009). Living with a concealable stigmatized identity: The impact of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, and cultural stigma on psychological distress and health. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 97(4), 634–651. doi: 10.1037/a0015815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn DM, & Earnshaw VA. (2011). Understanding concealable stigmatized identities: The role of identity in psychological, physical, and behavioral outcomes. Social Issues and Policy Review, 5(1), 160–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-2409.2011.01029.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Zarwell M, Pearson B, & Lewis M. (2019). “A Gay Man and a Doctor are Just like, a Recipe for Destruction”: How racism and homonegativity in healthcare settings influence PrEP uptake among young Black MSM. AIDS and Behavior, 23(7), 1951–1963. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2375-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radcliffe J, Doty N, Hawkins LA, Gaskins CS, Beidas R, & Rudy BJ. (2010). Stigma and sexual health risk in HIV-Positive African American young men who have sex with men. dx.doi.org. doi: 10.1089/apc.2010.0020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravenhill JP, & de Visser RO. (2018). “It takes a man to put me on the bottom”: Gay men’s experiences of masculinity and anal intercourse. Journal of Sex Research, 55(8), 1033–1047. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2017.1403547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rendina HJ, López-Matos J, Wang K, Pachankis JE, & Parsons JT. (2018). The role of self-conscious emotions in the sexual health of gay and bisexual men: Psychometric properties and theoretical validation of the sexual shame and pride scale. Journal of Sex Research, 1–12. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2018.1453042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richman LS, & Zucker AN. (2019). Quantifying intersectionality: An important advancement for health inequality research. Social Science & Medicine. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.01.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roye CF, Tolman DL, & Snowden F. (2013). Heterosexual anal intercourse among Black and Latino adolescents and young adults: a poorly understood high-risk behavior. Journal of Sex Research, 50(7), 715–722. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.719170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldana JM. (2015). The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Sandfort TG, & de Keizer M. (2001). Sexual problems in gay men: An overview of empirical research. Annual Review of Sex Research, 12(1), 93–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simoni JM, Beima-Sofie K, Amico KR, Hosek SG, Johnson MO, & Mensch BS. (2019). Debrief Reports to Expedite the Impact of Qualitative Research: Do they accurately capture data from in-depth interviews? AIDS and Behavior, 43(4), 1–5. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-02387-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Bradley H, Hu X, Skarbinski J, Hall HI, & Lansky A. (2014). Men living with diagnosed HIV who have sex with men: Progress along the continuum of HIV Care - United States, 2010. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 63(38), 829–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit PJ, Brady M, Carter M, Fernandes R, Lamore L, Meulbroek M, et al. (2012). HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: A literature review. AIDS Care, 24(4), 405–412. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2011.613910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahlman S, Hargreaves JR, Sprague L, Stangl AL, & Baral SD. (2017). Measuring sexual behavior stigma to inform effective HIV Prevention and treatment programs for key populations. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 3(2), e23. doi: 10.2196/publichealth.7334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss A, & Corbin J. (1994). Grounded theory methodology: An overview. In Denzin NK & Lincoln YS. (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research (pp. 273–285). Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PS, Alex C-D, Coates T, Goodreau SM, McGowan I, Sanders EJ, et al. (2012). Successes and challenges of HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. Lancet, 380(9839), 388–399. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60955-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.