Abstract

Background

Syncephalastrum species belong to the class Zygomycetes and order Mucorale. These are found in the environment and tropical soil, usually presenting as colonizers and rarely cause human infection. Syncephalastrum racemosum is a species of the genus Syncephalastrum and is the most commonly identified pathogen. Most cases are reported in immunocompromised individuals, such as patients on long term steroids, poorly controlled diabetes, or patients with malignancy.

Case presentation

We are describing two cases of rare fungal infection by Syncephalastrum species causing invasive pulmonary manifestation. Both patients had compromised immune status and presented with worsening dyspnea to the emergency room. Both had signs and symptoms of bilateral worsening pneumonia evident by chest X-ray showing bilateral pulmonary infiltrates. Syncephalastrum species were isolated from sputum cultures. Deoxycholate amphotericin B was started and the response was monitored. One patient expired while the other improved. Syncephalastrum species belong to class Mucormycosis, rarely causing invasive infection but when they do outcome is potentially fatal. Very few cases are reported worldwide so the clinical course is still unclear. To the best of our knowledge, these are the first two cases to be reported from Pakistan.

Conclusions

These two cases describe pneumonia as a result of concomitant infection by rare fungal speciesSyncephalastrum and MRSA in immunocompromised patients. Few cases are reported so limited data is available to understand complete disease implications. Mucormycosis is a therapeutic challenge because of the phylogenetic diversity, un-availability of any serological testing and invasive disease pattern.

Abbreviations: MRSA, Multi drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus; IV, intravenous; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CT, Computed Tomography; MIC, Minimum inhibitory concentration; VATS, video assisted thoracic surgery

Keywords: Mucormycosis, Syncephalastrum, Pneumonia, Fungal, Pakistan

Introduction

Mucormycosis also known as Zygomycosis is infection with a class of fungi including three orders, the largest of them is Mucorales. The most common species of this order are Rhizopus and Mucor [3] but there are certain rare species such as Syncephalastrum. These are often responsible for opportunistic fungal infections in immunocompromised patients [13]. Syncephalastrum racemosum, the species of the genus Syncephalastrum species is potentially fatal to human beings. Although usually resulting in cutaneous infections and onychomycosis, there have been few case reports of respiratory and CNS infections in immunocompromised hosts [14]. Since this is a rare entity, hardly any data is available on treatment response to different antifungal agents. However recent improvements in diagnostic strategies result in early identification and treatment. Amphotericin B is the drug of choice due to its low MICs [15]. We are describing these cases to emphasize the importance of considering rare fungal infections in the differential diagnosis of an immunocompromised patient as timely diagnosis and management results in improved clinical outcomes.

Case report

Case 1

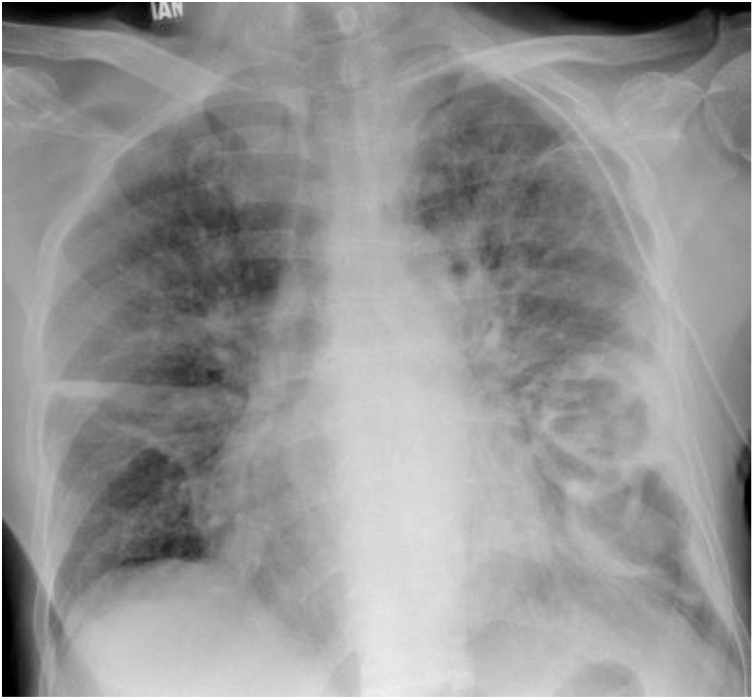

A 55-year-old South Asian gentleman recently diagnosed with Acute Myeloid Leukemia, not on treatment, presented to the emergency room with one day history of severe shortness of breath, fever, and scanty sputum production. On examination he was found to be hypoxic with oxygen saturation (SaO2) of 90 % on room air, hypotensive with pressures of 90/60 mmHg, temperature of 38 °C, tachycardia with a pulse rate of 102/min, and bilateral coarse crepitations on auscultation. Chest X-ray (Fig. 1) showed bilateral infiltrates. In view of his recent hospitalization, he was provisionally diagnosed with hospital-acquired pneumonia and was started on empirical piperacillin/tazobactam. However, based on his sputum culture showing Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and Syncephalastrum species, deoxycholate amphotericin B and vancomycin were introduced in the regimen resulting in a gradual reduction of white blood counts from 23 × 109/L (17 % blast cells) to 10.7 × 109/L. Histopathology or tissue sampling was not performed in this patient. The patient improved initially but after 8 days of therapy, he developed acute kidney injury, hypotension and severe lactic acidosis. Both drugs were adjusted according to a creatinine clearance of 10 mL/min; deoxycholate amphotericin B 1 mg/kg/day was reduced to 0.5 mg/kg/day and vancomycin was adjusted to keep trough levels between 10−20 mg/L. The patient gradually improved on treatment but subsequently deteriorated as evident by declining creatinine clearance on day 8. A progression of his primary disease was thought to be an accelerating factor. He developed metabolic and respiratory acidosis and was intubated on day 12 and hemodialysis was planned but he expired after 12 days of admission (after receiving 10 days of deoxycholate amphotericin B and vancomycin).

Fig. 1.

Chest X-ray. First X-ray of Case 1 on presentation.

Case 2

A 73-year-old gentleman, known patient of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), on tablet prednisolone 5 mg for the past one month (after a recent tapering from 30 mg/day) and inhaled salmeterol with fluticasone 25/250 mcg for almost 3 years. He presented with gradually worsening shortness of breath for one week in the emergency room. He had mucoid sputum production but no fever. On presentation, he had SaO2 of 88 % on room air, with low pressures of 100/60 mmHg, no fever, and a pulse rate of 90/min. He also had bilateral crepitations associated with a wheeze. Chest X-ray and CT chest (Fig. 2, Fig. 3 respectively) showed infiltrates and cavity formation. The total leucocyte count on presentation was 18.2 × 109/L. The patient was started empirically on piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin. Later, therapy was switched to deoxycholate amphotericin B, and vancomycin was continued according to his culture which grew MRSA, Aspergillus flavus, and Syncephalastrum species. Both A. flavus and Syncephalastrum spp. were identified on gross and microscopic morphology. Identification to genus level was performed for Syncephalastrum spp. as speciation was not possible with available laboratory capacity.

Fig. 2.

Chest X-ray. First X-ray of Case 2 on presentation.

Fig. 3.

CT Scan chest. Pretreatment Scan of Case 2 showing infiltrates and cavity formation.

Serum Beta D glucan level performed on day 5 of admission was 62.14 pg/mL, where levels <60 pg/ml were considered negative, 60−80 pg/ml borderline, and >80 pg/ml as positive as per manufacturer [Fungitell (Cape Cod, USA)]. Serum Aspergillus galactomannan index [Platiella (Biorad, France)] sent on the same day was 0.26, where a single value of >0.7 or two consecutive samples with a value of >0.5 were considered positive while a value <0.5 was deemed negative. The patient’s creatinine clearance declined to 27 mL/min after 7 days of therapy so doses were adjusted by reducing deoxycholate amphotericin B to 0.8 mg/kg/day from 1 mg/kg/day and trough levels for vancomycin were maintained between 10−20 mg/L. After 8 days of therapy on adjusted doses, the patient suddenly developed tachypnea, hypoxia, and hypotension. CT chest showed empyema so emergency video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) with decortication was performed. Chest tubes were also placed. Histopathology of pleural tissue performed showed moderate acute and chronic inflammatory cells with no evidence of granuloma formation or malignancy in the available material. Although gram stain and PAF were not performed on paraffin-embedded tissue sections, the sample was also sent to Microbiology for smear and culture. Gram stain of the tissue performed showed only gram positive cocci and cultures grew MRSA. No fungal culture was sent at that time. Acid-fast stain, GeneXpert MTB/RIF, and mycobacterial cultures were later reported negative. The patient received vancomycin and deoxycholate amphotericin B for MRSA and Syncephalastrum pneumonia for two weeks. He improved clinically after the surgery and was discharged after 44 days of stay on oral voriconazole as subsequent cultures grew Aspergillus flavus. Vancomycin was switched to oral linezolid with an early follow-up. His chest X-ray improved (Fig. 4) on day 50 of therapy. The patient was advised regular follow-ups. He eventually got better after 6 weeks of outpatient therapy. He was treated for total twelve weeks (including both in- and out-patient duration).

Fig. 4.

Chest X-ray. Post treatment X-ray of Case 2.

The diagnosis was made in both cases after the sputum culture reports were finalized, but at the initial presentation the differential diagnosis, keeping in view the immune status and recent hospitalization, included viral pneumonia, atypical and multi drug-resistant bacterial pneumonia, fungal pneumonia as with Pneumocystis jiroveci, and primary disease progression. In both cases, diagnosis of co-infection with MRSA and Syncephalastrum was considered.

Both cases were treated with deoxycholate amphotericin B, case 1 for 10 days, and case 2 for two weeks. In both cases, deoxycholate amphotericin led to acute kidney injury. However, in case 2, follow-up sputum cultures were sent 26 days after the the initial positive culture which came out negative for fungi. Due to limited data present and unavailability of management guidelines, it is unclear whether the negative culture report depicted that two weeks were sufficient enough for treatment or that the pathogen was a contaminant. A third sputum sample for culture sent at 34 days grew Aspergillus flavus, so voriconazole alone was continued for the next 6 weeks.

Discussion

Syncephalastrum species belong to the class Zygomycetes and order Mucorale [1]. These are found in the environment, and tropical soil [2] and usually present as colonizers [12] and rarely cause human infection [1,5]. When clinically significant, they are usually implicated in cutaneous infections and onychomycosis [3,11]. Very few cases are reported involving sites other than skin and nail tissues. Syncephalastrum species rarely result in pneumonia or a fungal ball like Aspergillus species [8]. Syncephalastrum racemosum belongs to genus Syncephalastrum and is the most commonly identified pathogen in this genus [4]. It has ribbon-like aseptate, branched fungal hyphae and sporangiophores, which terminate in swollen vesicles with radial merosporangiae filled with spores [6]. This pathogen formed light greyish-white fluffy colonies which filled a 90 mm plate completely in 48 h. Reverse was grey white. The colonies later became dark brown due to sporulation. Most cases are reported in immunocompromised individuals (Table 1), e.g. patients on long term steroids, poorly controlled diabetes [9], or patients with malignancy [13]. These patients are at high risk of developing an infection [7] and the combination of compromised immune status with a fungal infection, no doubt has a high mortality. Like other species of Mucormycosis, Syncephalastrum can also cause rhino-cerebral or rhino-orbital-cerebral infection [10]. Only one case with intra-abdominal infection is reported [14]. Syncephalastrum racemosum closely mimics Aspergillus in microscopy due to its vesicle surrounded by radially arranged sporangia, and is likely to be misidentified. Even when recognized correctly, since it is usually a contaminant, a high index of suspicion and systematic approach in accurate diagnosis is needed to establish its clinical significance for the successful outcome of treatment [3]. The only effective treatment option available is amphotericin B or posaconazole but possibly not isavuconazole/ ravuconazole [17]. Early identification and initiation of therapy is the mainstay of improved clinical outcome. Apart from these, the immune status of patients also helps in determining the prognosis.

Table 1.

Review of previous case reports.

| Case report authors | Sites involved | Co morbid | Management | outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sabitha B. et al [3] | Nails - onychomycosis | Diabetic | Surgical debridement + nystatin | Survived |

| Kamalam A. et al [7] | Nails - onychomycosis | Diabetic | Local debridement | Died of other complications |

| Kirkpatrick MB. Et al [8] | Lung | – | – | Unknown |

| Mangaraj S [9] | Subcutaneous tissue | Diabetic | Surgical debridement + Amphotericin B | Survived |

| Pavlovic MD [12] | Nails-onychomycosis | Immune competent | Nail plate avulsion + nystatin | Survived |

| Mathuram AJ [10] | Rhino-orbito cerebral | Diabetes | Amphotericin B | Unknown |

| Rodriguez-Gutierrez G [12] | Lung | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | Amphotericin-B itraconazole, caspofungin, voriconazole + surgical resection | Died |

| Schlebusch S. et al [14] | Intra-abdominal collection | Immune competent | Surgical debridement + Amphotericin B | Survived |

| Arunava k. et al [16] | Ear | Diabetic | Surgical debridement + Amphotericin B | Survived |

These two cases describe pneumonia as a result of concomitant infection by rare fungal species Syncephalastrum and MRSA in immunocompromised patients.

Few cases are reported so limited data is available to understand complete disease implications. Only two cases of lung infection leading to pneumonia were reported and even in those the management strategy used was variable and unclear. In our case report; case 1 had untreated malignancy and repeated hospital encounters, similar to another case report with Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma patient. In both our and their cases, patients expired suggesting the invasiveness of this pathogen, but the natural disease course was not fully understood. In case 2, in contrast to available case reports, patients with COPD with acute pneumonia and on long-term steroids but otherwise healthy was also managed on the lines of probable pulmonary mucormycosis with co-infection. Keeping in account the acuity of his illness, Aspergillus in repeat culture might not be the only answer to his condition. In one case report, a combination treatment strategy was also used, so azoles may show some efficacy against Syncephalastrum spp. if used in combination. However, since repeat cultures were sent late and after two weeks of amphotericin therapy, we still are not sure about the actual pathogens involved in the disease process. More substantial evidence is needed to conclude the definitive treatment strategy and management protocol. For now, management plan for mucormycosis is no doubt a therapeutic challenge because of the phylogenetic diversity, unavailability of any serological testing and invasive disease pattern. So far management strategy is individualized for every case, so till any specific guidelines are devised, every case is worth reporting.

Authors’ contributions

MI, NN, SFM and JF were responsible for manuscript writing and editing. UHH, MI, NN, and SFM were involved in management of patients during hospital stay. MI, JF and SFM thoroughly reviewed the manuscript. All authors have made substantial contribution to this case report and have read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

Data Sharing is not applicable to this study as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study

Sources of funding

No fundings were availed

Consent

Details mentioned in ERC. This study is a retrospective case series of two cases and an ERC exemption was obtained instead of informed consent

Declaration of Competing Interest

No conflicts of interest

Acknowledgements

Authors thank the microbiology team at Aga Khan University Hospital for isolating Syncephalastrum species.

References

- 1.Amatya R., Khanal B., Rijal A. Syncephalastrum species producing mycetoma-like lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2010;76(3):284–286. doi: 10.4103/0378-6323.62977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barcoto M.O., Pedrosa F., Bueno O.C., Rodrigues A. Pathogenic nature of Syncephalastrum in Atta sexdens rubropilosa fungus gardens. Pest Manag Sci. 2017;73(5):999–1009. doi: 10.1002/ps.4416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baby S., Ramya T.G., Geetha R.K. Onychomycosis by syncephalastrum racemosum: case report from kerala. India. Dermatol Reports. 2015;7(1):5527. doi: 10.4081/dr.2017.5527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buayairaksa M., Kanokmedhakul S., Kanokmedhakul K., Moosophon P., Hahnvajanawong C., Soytong K. Cytotoxic lasiodiplodin derivatives from the fungus Syncephalastrum racemosum. Arch Pharm Res. 2011;34(12):2037–2041. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-1205-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garg N., Prakash O., Pandey B.K., Singh B.P., Pandey G. First report of black soft rot of indian gooseberry caused by Syncephalastrum racemosum. Plant Dis. 2004;88(5):575. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.5.575C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jindal N., Kalra N., Arora S., Arora D., Bansal R. Onychomycosis of toenails caused by Syncephalastrum racemosum: a rare non-dermatophyte mould. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2016;34(2) doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.176844. 257- [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kamalam A., Thambiah A.S. Cutaneous infection by Syncephalastrum. Sabouraudia. 1980;18(1):19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirkpatrick M.B., Pollock H.M., Wimberley N.E., Bass J.B., Davidson J.R., Boyd B.W. An intracavitary fungus ball composed of syncephalastrum. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;120(4):943–947. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1979.120.4.943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mangaraj S., Sethy G., Patro M.K., Padhi S. A rare case of subcutaneous mucormycosis due to Syncephalastrum racemosum: case report and review of literature. Indian J Med Microbiol. 2014;32(4):448. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.142252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mathuram A.J., Mohanraj P., Mathews M.S. Rhino-orbital-cerebral infection by Syncephalastrum racemosusm. J Assoc Physicians India. 2013;61(5):339–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pavlovic M.D., Bulajic N. Great toenail onychomycosis caused by Syncephalastrum racemosum. Dermatol Online J. 2006;12(1):7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao C.Y., Kurukularatne C., Garcia-Diaz J.B., Kemmerly S.A., Reed D., Fridkin S.K. Implications of detecting the mold Syncephalastrum in clinical specimens of New Orleans residents after Hurricanes Katrina and Rita. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(4):411–416. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e31803b94f9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rodriguez-Gutierrez G., Carrillo-Casas Em, Arenas R., Garcia-Mendez Jo, Toussaint S., Moreno-Morales Me. Mucormycosis in a non-hodgkin lymphoma patient caused by Syncephalastrum racemosum: case report and review of literature. Mycopathologia. 2015;180(1-2):89–93. doi: 10.1007/s11046-015-9878-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schlebusch S., Looke D.F. Intraabdominal zygomycosis caused by Syncephalastrum racemosum infection successfully treated with partial surgical debridement and high-dose amphotericin B lipid complex. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(11):5825–5827. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5825-5827.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Espinel-Ingroff A., Chakrabarti A., Chowdhary A., Cordoba S., Dannaoui E., Dufresne P. Multicenter evaluation of MIC distributions for epidemiologic cutoff value definition to detect amphotericin B, posaconazole, and itraconazole resistance among the most clinically relevant species of Mucorales. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2015;59(3):1745–1750. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04435-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arunava K., Shamly V. Otomycosis caused by Syncephalastrum racemosum: a case report. http://lawarencepress.com/ojs_uploads/journals/26/articles/29/submission/review/29-128-1-RV.docx

- 17.Pettit Natasha, Carver Peggy. Isavuconazole: A New Option for the Management of Invasive Fungal Infections. Ann Pharmacother. 2015;49 doi: 10.1177/1060028015581679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data Sharing is not applicable to this study as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study