Abstract

Overview.

This work builds on previous efforts to delineate cross-cutting factors of evidence-based therapies. In this report, we target a single therapeutic factor—skills training for addictive behavior change—and we operationalize this factor in a manner that will aid clinical training and quality control. Specifically, we identify principles, which we defined as broader understandings on the part of the therapist that must be kept in mind when implementing a specific therapeutic practice. We define a practice as discrete action step or specific type of intervention that the therapist uses when addressing skills training content with clients.

Method.

We conducted a literature review and qualitative content analysis of 30 source documents (i.e., therapy manuals, literature reviews, and government issued practice guidelines) and videos (i.e., therapy demonstration videos). We performed analysis of source materials in NVIVO.

Results.

We identified 10 principles and 30 therapeutic practices. Together, the principles suggest that skills training in evidence-based addiction therapies can be characterized as a client-centered approach to teaching and behavioral practice. The identified practices fell into four function themes: 1) client-centered goal-setting, 2) building client self-efficacy, 3) engaging in teaching, and 4) engaging in practice.

Conclusions.

When the identified principles and practices are combined, they can inform a fidelity-based approach to behavioral skills training that is applicable to a wide range of alcohol or other drug (AOD) content topics, therapeutic modalities, and implementation settings. We discuss future implications regarding standardized training and fidelity assessment.

Keywords: Alcohol treatment, Common factors, Drug treatment, Treatment fidelity, Therapist training

1. Introduction

The 1990s saw a proliferation of manualized therapies in the addictions field and in mental health, more broadly. Concurrently, large-scale reviews of addiction treatment suggested that while some evidence-based modalities showed a slight advantage over others, there were several effective alcohol or other drug (AOD) treatments available (Miller & Willbourne, 2002). Fast forward to the present where the notion that distinct evidence-based modalities are often equally efficacious, or the dodo bird verdict, is well accepted in the field (e.g., Imel, Wampold, Miller, & Fleming 2008; Wampold, 2001; Wampold & Imel, 2015). To emerge from close to three decades of efficacy trials with such a conclusion may have been disheartening to some, but the more pressing concern is, What’s next?

The National Institutes of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism and Drug Abuse (NIAAA; NIDA, respectively), as well as the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) now identify several evidence-based therapies for AOD disorders with moderate and generally similar effectiveness (e.g., NIDA, 2018). Questions about how to improve upon moderate effectiveness as well as how to encourage wide-scale adoption are the current raison d’etre in public health research. Implementation science has grown exponentially in recent years, as the addictions field seeks to ensure that the best available interventions are reaching the largest number of consumers in need of care. With multiple possible interventions for implementation, intervention selection can be difficult and the needs, resources, and interests of each respective implementation setting must be considered (Damschroder & Hagedorn, 2011). For example, SAMHSA Treatment Improvement Protocol 34 on Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies for Substance Abuse (2012) identifies seven different modalities for clinicians or agency administrators to select from and provides only general guidelines as to potential patient or agency matching factors.

In response to an ever-growing number of available evidence-based therapies, researchers in child and adolescent mental health have considered selection and implementation of “practice elements” rather than manualized interventions. Specifically, Chorpita, Daleiden, and Weisz (2005) reviewed intervention descriptions in 43 clinical trials, identifying 26 practice elements that were common to varied modalities, but that could be clustered by frequency of use within diagnostic categories (e.g., depression, anxiety). In later work, they reviewed 322 trials and the number of practice elements was raised to 54 (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009). Examples include assertiveness training, communication skills, problem-solving, relapse prevention, and social skills, which can be selected based on a patient-to-element matching algorithm (i.e., the Distillation and Matching Model; Chorpita, Becker, & Daleiden, 2007). In a similar effort, Abraham and Michie (2008) examined 195 published intervention descriptions in nutritional health and identified 26 “behavior change techniques”. This work was broadened to other health outcomes and the number of techniques was raised to 54 (Michie, Johnson, Frances, Hardeman, & Eccles, 2008). In contrast to Chorpita’s work, which sought to directly inform intervention selection, Michie, van Stralen, & West (2011) note an intent to develop a single nomenclature for identifying and defining discrete intervention components within clinical trials, systematic reviews, and implementation research. Overtime, Michie, Atkins, and West (2014) developed a Behavior Change Taxonomy comprising 93 techniques (e.g., problem-solving, self-monitoring, coping skills training) that have been disseminated to guide intervention development and description in clinical outcome research. Together, these efforts represent novel clinical and research directions, by offering an alternative to an emphasis on specific-modality, evidence-based therapies.

1.1. Rationale and objective

The current work builds upon efforts to delineate cross-cutting factors of evidence-based therapies in health and mental health. Here, we do something compatible, yet different. First, we focus on the addictions and addictive behavior change. Second, we target a single therapeutic factor, skills training, and we operationalize this factor in a manner that will aid future clinical training and quality control. We define skills training as a didactic and experiential therapeutic process for training intra- and inter-personal skills with clients. We have targeted skills training because it can be considered a broader category that includes many of the “elements” or “techniques” identified above. Specifically, these elements/techniques can be broadly categorized by commonalities in their process rather than in their content. For example, avoidance of cues, self-monitoring, and problem-solving (Michie, Atkins, & West, 2014) are all coping skills taught in behavioral addictions therapies. They may have differences in topical content, but an intervention process that is personalized (i.e., involving assessment of a skill deficit), didactic (i.e., involving teaching of a new skill), and experiential (i.e., involving application and practice of that skill) characterizes all of them. In other cases, even differences in topical content are unclear such as assertiveness training, social skills, and communication skills (Chorpita & Daleiden, 2009). These skills share a personalized, didactic, and experiential process, while also sharing a content emphasis on enhancing interpersonal functioning. Therefore, while the noted efforts to dismantle various modalities into shared elements or techniques are a pragmatic response to the proliferation of available evidence-based therapies, the individual selecting targets for clinical training or performance monitoring (e.g., clinician or administrator) will still have a large and diffuse field for selection.

In a literature review and qualitative content analysis of evidence-based addictions therapy sources (e.g., therapy manuals, demonstration videos), we first define skills training as a commonly used therapeutic factor and we then operationalize this factor with an emphasis on its process. Our rationale is that many approaches to training addictions and other therapies instead place the emphasis on content, and provide comparatively less direction on exactly how that content should be communicated to clients. We do not argue that content is unimportant, but that it is well-addressed in the existing literature and is therefore, not addressed here. The current work describes the skills training process, and thus provides a clinical guide that is applicable to a wide range of trainees and addiction care providers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Literature review: A cross-section of evidence-based addictions therapies

The current work followed three review phases. First, we obtained a purposive sample of manuals on the delivery of evidence-based, addictions therapies. The manual search process included expert consultation and access to available manuals on government websites such as NIAAA, NIDA, and SAMHSA. Given the emphasis on skills training in this report, we over sampled from behavioral models, such as cognitive behavioral therapy and relapse prevention. That said, we argue that the didactic and experiential process of skills training is cross-cutting1, and, thus, we reviewed therapy manuals from other modalities listed as evidence-based with adult AOD2 (NIDA, 2018). We selected therapy manuals as the primary source for analysis based on Chorpita and colleagues (2005) rationale: “Psychotherapy manuals help clearly specify therapy content, operationalize therapeutic procedures, specify a sequence to the operations, and provide a reliable dimension on which to aggregate across studies” (p. 10).

Within these manuals, procedural guidelines (e.g., pre-requisites, directions, sequencing), regardless of skills training content, were of primary interest. Second, we obtained therapy demonstration videos from two providers of video-format educational content. From these providers, we selected all available videos that focused on treating substance use disorders (e.g., American Psychological Association [APA]: Specific Treatments for Specific Populations Series; Pychotherapy.net: Brief Therapy for Addiction Series). Third, we searched the literature for other procedural descriptions, such as government-issued practice guidelines and clinical overviews on specific modalities. The result was a sample of 10 therapy manuals, 11 therapy training videos, 5 clinical overviews/literature reviews, and 4 practice guidelines.

2.2. Qualitative content analysis: Identifying the principles and practices of skills training

For each manual or other source document, two elements of process were of interest—principles and practices, or, in other words, being versus doing. For example, motivational interviewing (MI) identifies the core therapeutic principle of therapist empathy that can be measured by the specific “skill” of reflective listening. The MI therapist is being empathic while doing a reflection, and measures of MI fidelity contain both of these levels of performance assessment3. In the current case, the full definition of a principle is a broader understanding or way of being on the part of the therapist that must be kept in mind when implementing a specific therapeutic practice. In Goldfried’s (2019) formulation, the principle is a “middle level of abstraction” somewhere between a given theoretical orientation and a specified technique. We define a practice as discrete action step or specific type of intervention that the therapist uses when addressing skills training content with clients. Content, on the other hand, will depend on the goals and orientation of the treatment or provider context, and was not of major concern to this analysis. Using this a priori framework for a qualitative content analysis, we reviewed procedural guidelines within source documents. Review of video demonstrations was similar with the exception that we inferred principles and practices from observation if the video did not provide annotation to the demonstration.

The first author collected all data in NVIVO (version 12). We extracted each source excerpt (i.e., bullet point, sentence, paragraph, or observation) that qualified as a skills training principle or practice either as a direct quote or paraphrase, and then we assigned it to an emerging set of categories or nodes. We based these assignments on shared subject matter; for example, we grouped all excerpts about therapist “style” or “stance” into a single node about “therapist style” (i.e., Principle Ten). Principles were rare in the data relative to practices, which were quite frequent both within and across sources. As a result, we counted each file containing a reference to a given practice category/node to provide a frequency measure of salience within the data4. We also aggregated these derived practices according to themes, representing broader functions within the skills training process. Finally, to enhance rigor and reproducibility in the data, a trained research assistant rated excerpts from a 15% subsample of source references. Here, we reversed the order of operations (i.e., confirmatory goal)—we provided the research assistant with the operationally defined principle and practice categories (i.e., Tables One and Two) and asked them to make an orthogonal code (i.e., select only one designation) for each excerpt. This process is referred to as a “check on clarity of categories” (Thomas, 2006). The results of this process yielded an alpha of .92 for agreement against “gold standard” ratings that the first author5 provided, where values above .80 are considered acceptable (Krippendorff, 2004).

Table 1.

The overarching principles of the skills training process.

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| 1) Skills training is an action-oriented treatment process | Treatment benefit will require client action. |

| 2) Skills training requires a client-centered, working, relationship | Action-oriented therapeutic work requires a strong working relationship. |

| 3) Skills training is grounded in a shared goal, which provides an explicit rationale for the learning process | The foundation of a working relationship is a shared goal, which justifies the importance of each action-oriented therapeutic task. |

| 4) Skills training attends to client ambivalence as a natural part of the behavior change process | Although action is required for benefit, ambivalence may arise and should be attended to throughout the skills-training process. |

| 5) Skills training facilitates integration of a new behavioral norm | The goal is uptake and integration of learned coping skills. |

| 6) Skills training attends to client self-efficacy as a foundation component of successful behavior change | Practicing new behaviors is difficult and requires client self-efficacy; the skills-training process attends to and facilitates this needed client attribute. |

| 7) Skills training requires structure and time management to ensure reinforcement of client learning | The skills-training therapist should always be clear they have the time required for sufficient attention to a given topic; they should manage the time well to ensure all elements of the teaching process are addressed. |

| 8) Skills training involves teaching that is clear, interactive, and personally relevant to the client | Skills training is an educational process; the skills-training therapist should always be clear, should query client input, and should tailor learning content to client world view, needs and circumstances. |

| 9) Skills training involves practice that is consistent, reinforced, and personally relevant to the client | What distinguishes skills training from psychoeducation is the practice component; the skills-training therapist should be prepared to engage in consistent and personally-tailored practice exercises. |

| 10) The skills-training therapist is active, informed, engaged, compassionate, and detail-oriented | The skills-training therapist must demonstrate many qualities simultaneously, including being both flexible and client-centered as well as structured and detail-oriented. |

Table 2.

The technical practices of the skills training process.

| Skill | Description |

|---|---|

| Client-Centered Goal Setting | |

| Set goals on immediate needs | Therapist sets a clear goal based on client-identified and imminent/near-term needs. |

| Set goals in incremental steps | Therapist and client identify a task or series of tasks that will facilitate goal achievement; these tasks are highly feasible and likely to result in client success. |

| Set goals with an emphasis on client agency | Therapist makes explicit effort to instill and reinforce a sense of personal autonomy when setting goals in pursuit of behavior change. |

| Set goals using ‘we language’ | Therapist is thoughtful about collaborative language use, including the use of the pronoun “we” to reinforce an egalitarian climate and a shared goal. |

| Get a clear commitment on goals and steps | Therapist is very explicit and consistent in seeking client verbal commitment to agreed-upon goals and tasks. |

| Set goals while attending to client ambivalence | Therapist recognizes that motivation and commitment are dynamic, and influenced by intrapersonal and environmental factors; as such, the therapist attends closely to signs of client ambivalence related to agreed-upon goals and promptly explores client concerns. |

| Create a detailed plan to reach goals | Therapist facilitates creation of an action plan with measurable goals and tasks, timelines for completion, and an explicit plan for progress monitoring. |

| Query barriers and resources to reaching goals | Therapist explores both barriers and resources for pursuit of the agreed-upon action plan, and does so each time goals or tasks are discussed. |

| Building Self-Efficacy | |

| Build self-efficacy through optimism | Therapist communicates genuine optimism about client capacity for behavior change. |

| Build self-efficacy through affirmation | Therapist consistently affirms client qualities, efforts, and progress; these affirmations are thoughtful and genuine. |

| Build self-efficacy through questions | Therapist, where possible, evokes rather than instills client self-efficacy via targeted questions about client qualities, efforts, and progress. |

| Build self-efficacy through incremental gains | Therapist creates opportunities for client success and incremental goal achievement; when these moments occur, the therapist reinforces them via affirmations or evocation. |

|

Engaging in Teaching Teach with an agreed-upon agenda |

Therapist and client pursue an explicit and agreed-upon skills training agenda. |

| Teach with a clear, informed, and client-centered rationale | Therapist provides a well-informed, clear, and client-relevant rationale that is described in plain language. |

| Teach with structure and time management | Therapist provides structure and time-management to ensure that attention to teaching content is thorough. |

| Teach with successive difficulty | Therapist teaches skills that increase in difficulty; this ensures client early success and scaffolding early skills to learn later skills. |

| Teach with personally-salient content | Therapist uses evocation and reinforcement of client-derived material to underscore all teaching points. |

| Teach with plain language | Therapist always uses simple language when explaining skills training content. |

| Teach with questions | Therapist most often uses questions when teaching such that the teaching process then functions as a dialogue rather than a lecture. |

| Teach with repetition | Therapist often repeats and reinforces skills training content; this may occur through actual repetition, but most often occurs via targeted questions and reflections that serve to thread teaching content throughout the skills training dialogue. |

| Teach with specific teaching strategies | Therapist uses teaching strategies such as a teach back, normalizing, use of hypothetical scenarios, use of metaphors and imagery and slow processing of teaching content. |

| Teach with specific teaching materials | Therapist uses teaching materials such as a white broad, handouts, journals, or worksheets; all materials function to make teaching content more understandable and memorable. |

| Engaging in Practice | |

| Practice with a clear rationale specific to treatment benefit | Therapist always provides a practice rationale; the rationale is clear, succinct, and underscores the role of practice in achieving agreed-upon goals and tasks. |

| Practice with feasibility | Therapist provides opportunities for practice and practice assignments that are highly feasibly and likely to lead to client success. |

| Practice with compassion | Therapist explicitly recognizes the risks, barriers, and discomfort involved in practice. |

| Practice with attention to ambivalence | Therapist attends closely to signs of client ambivalence related to agreed-upon practice exercises and promptly explores client concerns. |

| Practice with modeling | Therapist always demonstrates skill enactment so that the client has a clear model to follow. |

| Practice with consistency and depth | Therapist utilizes practice consistently and always devotes sufficient time, attention, and resources to practice content. |

| Practice with performance feedback | Therapist provides specific, constructive feedback on client skill demonstration; therapist them provides opportunity for the client to apply feedback in subsequent practice. |

| Practice with review and debrief | Therapists always allots time for review and debrief of in and outside of session practice exercises. |

3. Results

3.1. Skills training as a cross-cutting therapeutic factor in evidence-based addictions therapies

In this subsection, we provide the results of the first pass review of all source materials. Here, we provide a broad overview of each evidence-based modality, and we briefly discuss the relevance of skills training within each modality. The goal here is to underscore the ubiquity of skills training across a range of evidence-based therapies for AOD.

3.1.1. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)

CBT for AOD can be defined as a brief intervention that targets cognitive, emotional, and environmental triggers for substance use and provides training in coping skills to help an individual achieve and maintain abstinence or use reduction. Approaches to delivery are often based on Marlatt and Gordon’s (1985) work on relapse prevention, and there are available manuals for use with AOD use disorders. Within the CBT etiological framework, an overreliance on the use of substances has compromised an individual’s coping capacity, and treatment, therefore, takes an explicitly educational approach (Center for Substance Abuse Treatment [CSAT], 2012). Behavioral skills training is a central feature of treatment and one that distinguishes CBT from more traditional cognitive therapy methods (Carroll, 1998). Intervention broadly encompasses three phases: 1) assessment and self-monitoring with functional analysis; 2) training in copings skills related to: avoidance of triggers/high risk situations, mood management, coping with craving, and a broad range of social skills; and 3) lifestyle enhancement and other maintenance considerations. Therefore, while content may vary, a personalized, didactic, and experiential skills training process characterizes the full course of CBT for AOD.

3.1.2. Behavioral couples therapy (BCT)

BCT for AOD is a CBT-based method grounded in the etiological assumption that central relapse precipitants are interpersonal, and that significant others are an important naturalistic support for facilitating client abstinence (O’Farrell & Schein, 2000). In BCT, clinicians pursue two phases of intervention, initial abstinence and relationship functioning, each with respective skills training components. For client stabilization with respect to substance use, a daily recovery contract acts both as a self-monitoring tool and a venue for mutual commitment and problem-solving among participating partners. In contrast to CBT, most self-monitoring is related to treatment-focused activities such as medication adherence, 12-step program attendance, and positive couple activities. Alcohol-focused behavior therapy (ABCT) and BCT can be distinguished by the former’s early emphasis on CBT for client substance use, including the use of CBT-based self-monitoring practices such as functional analysis (McCrady, Wilson, Munoz, Fink, Fokas, & Borders, 2016). When treatment enters the relational functioning phase, skills training foci include mood management, communication, and other relationship skills; instituting consistent interpersonal reinforcers for abstinence; and relapse prevention (McCrady et al., 2016; O’Farrell & Schein, 2000).

3.1.3. Motivational enhancement therapy (MET)

MET for AOD can be defined as a client-centered, MI-based brief intervention delivered over multiple sessions that incorporates personalized feedback on patterns of use in relation to age, gender, and often, location-matched norms. MET can be contrasted with more behaviorally oriented therapies, such as CBT or BCT, because there is no prescribed course of change. Rather, the intervention seeks to mobilize an internal change process that will be self-directed (Miller, 2000). While the feedback portion of the intervention is educational, experiential processes such as role play, homework, or other elements of practice are largely absent in intervention guidelines (e.g., Miller, Zweban, DiClemente, & Rychtarik, 1992). However, when planning for change, potential barriers to reaching self-directed goals are explored and therapist-provided resources, including anticipation and preparation for difficulties, are entirely appropriate (Martino et al., 2006). Modern cognitive behavioral modalities also attend closely to client motivation, including exploration and resolution of client ambivalence, rolling with resistance, and use of reflective listening (e.g., Miller, 2002; Smout, 2008). Therefore, clinical training materials in the addictions will have the greatest ecological validity if they are integrative (e.g., Combined Behavioral Intervention; Miller, 2002), and, as a result, we argue that skills training is relevant to MET, and therapist could use it when problem-solving during the change planning process.

3.1.4. Integrative modalities and 12-step modalities

Many other evidence-based addiction treatments incorporate skills training content. For example, the community reinforcement approach (CRA), including the community reinforcement approach with voucher incentives (i.e., contingency management), and community reinforcement and family training are considered “broad-spectrum behavioral interventions”, and skills training content is incorporated throughout the intervention process (Meyers & Smith, 1995). In essence, CRA can be considered an integrative treatment that includes a range of strategies such as motivational enhancement; functional analysis; social, recreational, and vocational skills training; medication management; contingent reinforcement; and relaxation training (Meyers & Smith, 1995; Miller, Meyers & Hiller-Sturmhofel, 1999). Similarly, mindfulness-based relapse prevention (Witkiewitz, Marlatt, & Walker, 2005) and the MATRIX Model (Smout, 2008) are an integration of existing CBT methods with Eastern philosophy-based mindfulness, relaxation, and/or acceptance and commitment therapy methods. In all cases, these are integrative modalities with substantial attention devoted to cognitive and behavioral skills training. Finally, modalities that emphasize client utilization of 12-step programs, such as twelve step facilitation (TSF), include numerous extra-session activities such as guided reading, journaling, and Alcoholics or Narcotics Anonymous meeting attendance (Nowinski, Baker, & Carroll, 1992). These activities are analogous to CBT homework or practice exercises and qualify as skills training content under our operational definition. The TSF client must also take numerous interpersonal risks, such as asking a 12-step program member to be a sponsor. When these kinds of impending treatment events arise, we advise that a role play with the therapist is appropriate, depending on the client’s level of interpersonal functioning (Nowinski et al., 1992).

3.2. The principles of skills training

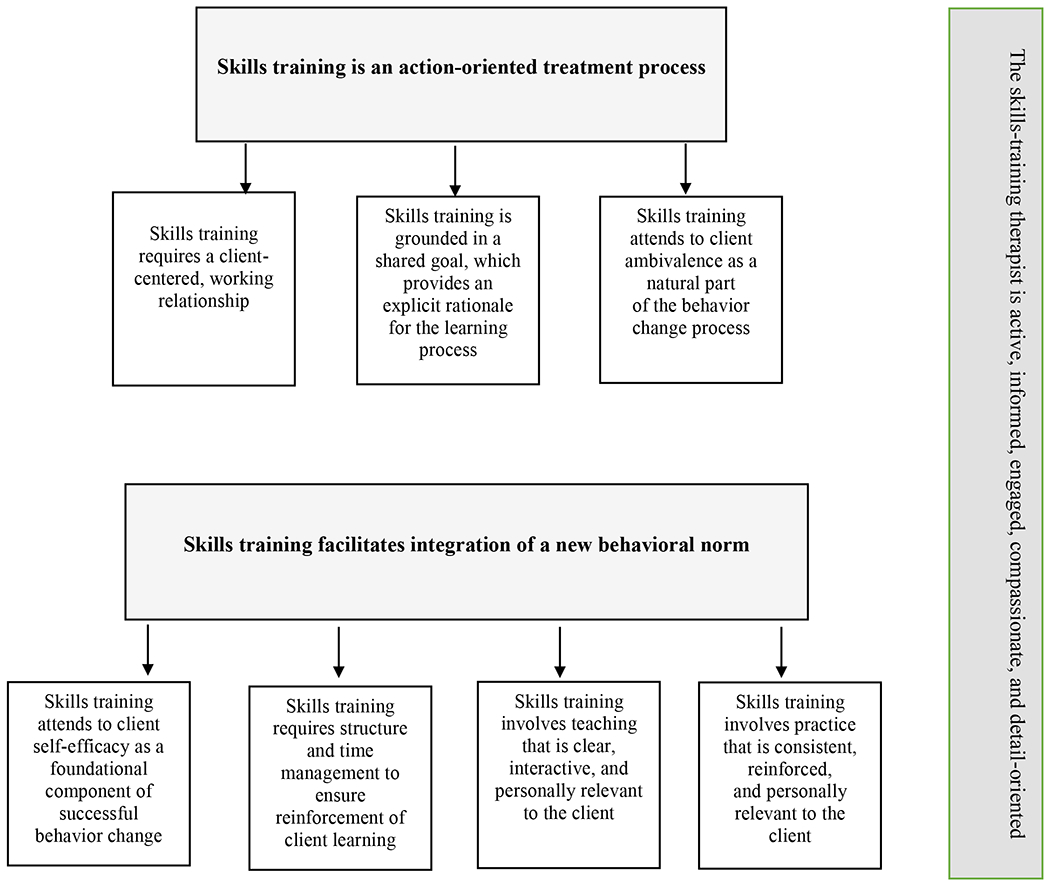

While the above section briefly demonstrates the cross-cutting relevance of skills training to various evidence-based AOD modalities, what follows is a description of the key principles derived from the content analysis of source materials (see also Fig. 1).

Fig. 1:

Conceptual flow chart for overarching principles of the skills training process.

The first principle of skills training is that it is action-oriented, and principle two speaks to the importance of a working therapeutic relationship in any action-oriented treatment process. A condition that is often misunderstood or under emphasized in behaviorally oriented therapy training is the importance of the therapy relationship as a necessary foundation for the work (Carroll, 1998). The relationship is not assumed, but rather actively attended to throughout the skills training process. Principle two also relates closely to principle three—the importance of a shared goal. Specifically, principle three argues that the goal of any skills training work must be explicit and shared, and will therefore, act as a clear rationale for the rigorous therapeutic activity that skill uptake requires. Because client action is central to therapeutic benefit (Nowinski et al., 1992), attention to the dynamics of client motivation and ambivalence are also constant throughout the skills training process (principle four). Attention to the agenda, protocol, or other aspects of content should never undermine attention to the relationship, fluctuating aspects of client motivation, or their most imminent needs (Carroll, 1998; Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Kadden et al., 1992; Miller, 2002; Monti et al., 2002). In summary, given the action-oriented nature of skills training, clear and consistent attention to the therapy relationship, to an explicit and shared goal, and to client motivation and ambivalence are central to the quality and success of any skills training intervention.

While principles one through four emphasize the role of relational and motivational factors in skills training, principles five through nine speak more to the nuts and bolts of intervention delivery. Here, principle five argues the overarching goal of any skills training endeavor is integration of a new behavioral norm (Nowinski et al., 1992), and this is not easily accomplished by clients. Therefore, principles six through nine describe the kind of therapeutic consistency and rigor this level of learning will require. In principle six, client self-efficacy is attended to as a foundational element of the process. The activity of the therapeutic work both requires and fosters self-efficacy, and the skills training therapist is quite explicit in targeting this needed client attribute (Monti et al., 2002). Principle seven concerns the issue of time management. Because adoption of a new cognitive or behavioral norm is a learning process, the needed amount of time, structure, and consistency must be a central consideration. Does the therapist have the time and resources to teach a skill in session, practice a skill in session, assign extra-session exercises based on that skill, and then review those exercises in subsequent sessions? Such steps are essential and without them, the skill-based content will receive lip-service at best (Carroll, 1998). Next, and because the skills training process requires significant time and attention, the skills trainer must be engaging. This means that the skills training therapist does not talk more than the client, and will typically rely on open-ended questions and reflective listening techniques that may be more typically associated with client-centered therapy methods (see e.g., Marlatt 1997, APA; Liese, 2000, Pychotherapy.net; McCrady, 2000, Pychotherapy.net). Therefore, the teaching style is interactive and personalized as a means of maintaining client engagement (principle eight). Finally, principle nine argues that practice is essential and should be consistent, thorough, and personalized, based on client information evoked during the teaching process.

The final principle (principle ten) offers a description of the role, nature, and style of the skills training therapist. Here, we highlight the role of content, because it is vital that the therapist is well-informed of the specific skills training content they are teaching. Under this condition, they are equipped to deliver that content in a flexible, integrated, and highly engaging manner. Most cognitive-behavioral manuals cautioned strongly against any lecturing, reading, or other use of overly directive methods (Carroll et al., 1998; Kadden et al., 1992; Meyers & Smith, 1995; Miller, 2002; Monti et al., 2002). Rather, the content is so well integrated into the therapist repertoire, that it can be delivered via discussion and can be readily retrieved to underscore its relevance to the client’s thoughts, language, and experiences as they arise at any point during the therapeutic dialogue (McCrady, 2000, Pychotherapy.net). The overarching theme for principle ten is that the skills training therapist is highly engaging and client-centered, while also being structured, repetitious, and detail-oriented. This is not an easy balance to strike. However, source materials underscored that the combination of these relational and teaching capacities is essential (Miller, 2002). Finally, the skills training therapist is optimistic that there will be benefits for the client, but also entirely realistic and compassionate about the difficulties inherent in the behavior change process (see Table 1 for principles one through ten, with definitions).

3.3. The practices of skills training

While the above principles describe a way of being with the client, the following practices describe the how of skills training; these practices can be organized into four function themes: 1) client-centered goal-setting, 2) building client self-efficacy, 3) engaging in teaching, and 4) engaging in practice (see Table 2 for definitions).

3.3.1. Client-centered goal-setting

First, 26 of 30 source documents and videos discussed procedural elements related to client-centered goal setting. This category of practices facilitates the noted principles of having and maintaining a working relationship, a shared goal, and a highly personalized teaching and practice experience (principles two, three, eight, and nine). Client-centered goal setting acts both as assessment and contracting, given it is evocative (i.e., involving primarily questions) and collaborative (i.e., mutually agreed upon; McCrady, 2000, Pychotherapy.net), respectively. As noted in principle three, the explicit and shared goal provides the rationale for the therapeutic work that is to follow. Specific goal-setting practices include targeting immediate needs (6/30 sources; i.e., the presenting concern at this time in treatment, e.g., making a change in alcohol or other drug use behavior) as well as incremental steps (11/30 sources; i.e., the specific coping skills or other therapeutic tasks that will help the client to address their immediate needs). Several manuals cautioned against loosing focus on the agreed-upon goal in the face of shifting client priorities or other crises (Carroll et al., 1998; Kadden et al., 1992; Monti et al., 2002). Specifically, the therapist should balance a directive approach to goal pursuit with the flexibility to shift focus when it is clearly warranted.

The overarching aims of any skills training, goal-setting process will be to identify goals and tasks that are shared, clear, feasible, and that will foster experiences of success, including client gains in self-efficacy and personal autonomy. In fact, the most commonly recommended goal-setting procedures were related to the therapist’s explicit emphasis on client agency (17/30 sources). The dialogue of goal setting should thus include reinforcement of client ideas about goals and tasks, decision-making capacity, responsibility for change, and will include brief verbal cues such as permission seeking in, for example, moments of advising or redirection (Liese, 2000, Pychotherapy.net; Lejuez, 2018, APA; Wubbolding, 2000, Pychotherapy.net; Zweban, 2000, Pychotherapy.net). Moreover, the therapist will often select the pronoun “we” over “I’ or “you” to further communicate a shared agenda (Marlatt, 1997 APA; Lejuez, 2018, APA; McCrady, 2000, Pychotherapy.net). The second most common goal-setting recommendation involved seeking explicit client commitment on goals and tasks (12/30 sources, e.g., Carroll, 1998; Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Miller, 2002; Miller et al., 1992; Martino et al., 2006; Nowinski et al., 1992; O’Farrell & Schein, 2000). The source documents and videos underscored the importance of both “meeting clients where they are” with respect to commitment and the need to obtain verbal commitment wherever possible. Similarly, the skills training therapist should attend closely to signs of fluctuating client commitment, should have compassion for ambivalence as a natural part of the behavior change process, and should explore client ambivalence when it arises (10/30 sources, e.g., Carroll, 1998; Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Martino et al., 2006; Meyers & Smith, 1995; Miller, 2002; Smout, 2008). The final recommendations relate to the skills training action plan itself; here goals and tasks must be clear, measurable, and include timelines for completion as well as plans for progress monitoring (11/30 sources). As part of the plan and whenever goal- or task-setting discussions arise, the process will query barriers and resources for change (9/30 sources).

3.3.2. Building client self-efficacy

Among sources, 24 contained clear references to strategies to build and reinforce client self-efficacy regarding behavior change (principle five). A significant majority of source references were specific to direct, verbal affirmation of client qualities, efforts, and progress (21/30 sources e.g., Carroll, 1998; Kadden et al., 1992; Martino et al., 2006; Miller, 2002; Miller et al., 1992; Nowinski et al., 1992), but more subtle recommendations about the need for therapist optimism (10/30 sources) were also important. Therapist optimism can be considered more of a pre-requisite or principle than a concrete skill, although the therapist can verbalize optimism to clients (Miller, 2007, APA). The pre-requisite of optimism and the skill of affirmation must intersect. Sources underscored that affirmations must be genuine or the client will not receive them well and that that could negatively impact the working relationship (Miller, 2000, Pychotherapy.net). One common source of genuine affirmation was direct acknowledgement of client efforts, including all approximations of success in goal and task achievement (8/30 sources). Client self-efficacy in skills training is both a needed client attribute and a mechanism of change, and as such, efforts to instill self-efficacy must be skillful, consistent, and genuine. A final strategy to facilitate genuine affirmation is to build self-efficacy via evocation. In other words, the most powerful reinforcement of client strengths will come from clients themselves. Questions that can enhance self-efficacy include direct self-assessment questions, and querying past successes and self-identified progress (10/30 sources e.g., Lejuez, 2018, APA; Marlatt, 1997, APA; Norcross, 2000, Pychotherapy.net). In this sense, all areas of reinforcement can be evoked from the client rather than instilled by the therapist.

3.3.3. Engaging in teaching

Given that we oversampled for behaviorally oriented treatment sources, we understand why the majority included some recommendation on teaching procedures (29/30 sources). Interestingly, the most commonly cited skill was teaching in a manner that incorporated client material. In all aspects of teaching, sources recommended use of client language, imagery, examples, and ample use of Socratic questioning techniques (23/30 sources). Teaching for integration of a new behavioral norm (principle five) requires significant effort for both therapist and client, although it is the therapist who has primary responsibility for pursuing the learning agenda (9/30 sources). As a result, the therapist should be well-informed, and the rationale should be clear; personally salient to the client; and communicated in plain, preferably client-derived language (Carroll, 1998; Martino et al., 2006). Teaching skill content should also occur with successive difficulty if multiple skills are being taught (6/30 sources e.g., Monti et al., 2002). Finally, the therapist should appropriately structure the therapeutic time to allow a detailed and thorough treatment of any skills training content (13/30 sources). By teaching via dialogue rather than lecture, the therapist’s style should promote client acceptance of therapist-enacted time management whenever a skills training topic, goal, or task is the subject of the therapy session.

While a client-centered rationale and structure provide the back drop for a skills training session, sources underscored the importance of consistent therapist effort to counteract the capacity of the teaching process to become rote or disempowering for the client. As noted, teaching should occur via a dialogue with ample opportunities for client input (14/30 sources). The client should speak more than the therapist, and this can be accomplished via questions and threading reflections that reinforce the skills training content (Marlatt, 1997 APA; Liese, 2000, Pychotherapy.net; McCrady, 2000, Pychotherapy.net). Repetition is vital in a behavioral modification context, but must occur within a client-centered dialogue (15/30 sources). Therefore, the therapist teaches with plain language (7/30 sources) that is meaningful and salient to the client (9/30 sources) and may employ specific strategies (12/30 sources) such as a teach back (i.e., asking the client to explain the teaching content in their own words), normalizing (i.e., connecting the client experience to the experience of other clients or to population-based research data), hypothetical scenarios (i.e., possible situations where skills could be applied), the use of metaphor or imagery (e.g., “craving can be like a wave; it begins, grows and crests, but it will eventually subside and go away”), and slow-processing (e.g., “I am hoping you can slow the story down for me, and then together we can identify possible high risk situations that occurred along the way”). Finally, the therapist teaches with specific materials that serve to make skills training more understandable, feasible, and memorable (10/30 sources).

3.3.4. Engaging in practice

The central element of skills training, and the feature that distinguishes it from psychoeducation, is the experiential aspect of practice. We define practice as any within or postsession activity that provides opportunity for application of skills training content. These opportunities may include role play, self-monitoring, engaging with health promotion computer applications, planned interactions with friends or family, other planned coping activities, and attending support groups. As a result, our definition of practice incorporates both in-session exercises and assigned homework. Among sources, 22 contained references to practice and additionally underscored that the practice element is the very foundation of skill uptake and generalization. Many document sources also offered substantial discussion of the difficulties inherent in achieving high quality practice and consistent practice compliance (e.g., Carroll, 1998; Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Kadden et al., 1992; Monti et al., 2002). A common reference was to the importance and nature of the practice rationale. Specifically, the within or outside of session practice exercises should be preceded by a clear and succinct rationale that highlights the role of practice in goal and task achievement (9/13 sources). Sources also noted the rationale for practice as an assessment of tool (Carroll, 1998) as well as a source of feedback on treatment progress (Lejuez, APA, 2018).

Given the natural risks involved in the application of learned coping skills, other common recommendations were related to ensuring the feasibility of task completion and the relational aspects of negotiating practice (7/13 sources). To be feasible, the practice task must be highly relevant to client interests, needs, and circumstances, which can be achieved via the above noted goal-setting and teaching practices. Other considerations for promoting feasibility include identifying a specific time for task completion (Monti et al., 2002), providing any needed tools or materials (Kadden et al., 1992; McCrady, 2000, Pychotherapy.net), and modeling all procedures (Carroll, 1998; Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Kadden et al., 1992; Meyers & Smith, 1995; Monti et al., 2002). Many source recommendations were also related to negotiating practice exercises with compassion (4/30 sources) and attention to client ambivalence (6/30 sources). Here, the therapist must have compassion for the practical (e.g., available time and resources) and emotional (e.g., risk taking, performance anxiety) barriers involved in practice, both in and outside of sessions. Sources recommended directly noting and normalizing these concerns and even sharing any of the therapist’s own discomfort with some exercises such as role play (Monti et al., 2002). Attention to ambivalence may include attending to subtle cues such as changing the subject and more overt cues such as not completing assignments (Carroll, 1998). A number of sources underscored the need to review all assigned exercises or homework, or risk communicating a belief that these efforts are unimportant and superfluous to the work that occurs within sessions (13/30 sources, e.g., Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Kadden et al., 1992; Liese, 2000, Pychotherapy.net; Nowinski et al., 1992; Witkiewitz, Marlatt, & Walker, 2005).

The remaining recommendations speak more to exactly how behavioral practice should be undertaken, and are relevant both to in and outside of session exercises. A number of key sources recommended “role reversaf’ in instances of role play such that the client would always have the opportunity to witness and learn from the therapist demonstration of the skill first (6/30 sources, e.g., Carroll, 1998; Epstein & McCrady, 2009; Kadden et al., 1992; Monti et al., 2002). These same sources underscored the importance of consistency and depth to any skill uptake and behavioral integration. Examples of consistency include the steps involved in the practice exercise (e.g., 1) provide rationale, 2) demonstrate [therapist], 3) demonstrate [client], 4) performance feedback, 5) demonstrate [client], 6) review and debrief), in the amount of time allotted (e.g., one third of session), and in the frequency of engagement (e.g., every session). Granted, such consistency may not be feasible when skills training is not the central goal of therapy, but therapists must ensure that they have enough time and resources to devote to a given skills training topic (principle seven). For all exercises in and outside of sessions, feedback on performance should be provided (6/30 sources). Source recommendations included first inviting a self-assessment, affirmation of effort and strengths of performance, providing specific enhancements, and then providing opportunity for the client to apply the feedback in a repeated performance (Carroll, 1998; Kadden et al., 1992; Miller, 2002; Monti et al., 2002). Finally, a summary review should always be undertaken that allows the client to process the emotional, behavioral, and consequential aspects of the experience, while also building commitment for maintenance of change (9/30 sources).

4. Discussion

In this work, we speak primarily to technically eclectic or integrative therapists and trainees who find themselves engaging in skills training work with their clients, but who do not consider themselves expert in CBT for addictions. Among a nationally representative sample of inpatient and outpatient addiction treatment programs, 94% reported using substance abuse counseling always or often (National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services, SAMHSA, 2018), which is likely a blend of strategies from the evidence-based modalities discussed in this review. As a result, our work is likely relevant to a broad range of professional, paraprofessional, and trainee providers of AOD services. We have also argued that the content of skills training is well-addressed in the existing literature and is thus not the focus here. The current review, instead, outlines the process of skills training in a content agnostic manner. The principles and practices operationalized here can be used as a fidelity-based guide to delivering skills training content, regardless of the nature of that content and of the theoretical orientation of the provider.

4.1. An operationalized process of skills training: Some key points

This manual, video, and guideline review yielded an integrative, client-centered approach to behavioral skills training with relational and didactic methods sharing equal emphasis in the qualitative results. Government-issued practice guidelines on AOD care highlight the following shared characteristics of brief addiction therapies: 1) they target a specific behavioral outcome, 2) they rely on a strong working relationship, 3) the therapist is both active and empathic, and 4) responsibility for change is with the client (CSAT, 2012). These characteristics were repeatedly represented in this review of various modalities. This speaks to the first key point. The contribution of this work may not be novel knowledge, but rather the synthesis of existing, but diffuse, knowledge into a single clinical process guide. A minority of sources provided entire sections or chapters on therapeutic procedures (i.e., what we term process; e.g., Kadden et al., 1992. Guidelines for Behavioral Rehearsal Role Plays). The remaining sources noted procedural elements throughout content descriptions, and many times we had to infer them from application examples. We derived a second key point primarily from the video sources. Despite varying titles and therapy foci descriptions, the sessions we observed were remarkably similar. These master therapists were delivering client-centered, behaviorally oriented therapy with particular attention to developing a rapport and attending to client motivation. Part of this may have been because all session demonstrations were first time sessions, but the consistency in therapist methods suggests that many evidence-based addiction therapies can be characterized by commonalities in their process even if they have differences in topical content. A question for future research is which of these—process or content—holds the greatest promise as a mechanism of client change. A final key point is that skills training, resulting in a new behavioral norm, requires a significant and sustained concerted effort from the therapist and client. As a result, providers must be committed to implementing the principles and practices described here with real consistency and dedication if skill uptake and generalization is the goal.

4.2. Toward a fidelity-based approach to skills training: Key implications

This review sets a foundation for future work on therapist training and fidelity monitoring of skills training delivery. Here, we use Bellg and colleagues’ (2004) guidelines to outline key implications for applying our results to a training context. With respect to provider training, training procedures should be standardized, including length of training, mode of training (e.g., in person versus online), mode of follow-up assessment (e.g., standardized patient or self-report measure), and measurement of skill acquisition. In the case of skills training, the training process can act as a parallel process, modeling many of the teaching techniques the trainees will be expected to enact with clients. We would even argue that clinicians could employ some relational and motivational techniques described here to promote adherence with post-training skill maintenance tools. Further, feasible and acceptable skill maintenance tools should be considered a requirement given that research underscores the need for some post-training follow-up in the form of performance coaching to prevent provider “drift” (Bellg et al., 2004; Carroll et al., 2006; Martino, Ball, Nich, Canning-Ball, Rounseville, & Carroll, 2011; Miller, Yahne, Moyers, Martinez, & Pirritano, 2004). Post-training skill acquisition measures should parallel fidelity monitoring measures, with standards of competence to guide evaluators (e.g., Moyers et al., 2016). While a pre- and post-test of skill change, using a standardized patient role play, is needed for initial proof-of-concept testing, practitioners must develop additional training and fidelity monitoring materials that provide a “good enough”, low burden alternative for ease of implementation by individual trainers. Finally, online platforms for individual management of learned skills, including opportunity for “deliberate practice” (Rousmaniere, 2017) can provide greater flexibility for trainee maintenance efforts.

4.3. Limitations and conclusions

This literature review and qualitative content analysis yielded 10 principles and 30 practices relevant to the process of skills training in evidence-based addiction therapies. While the sample size for content analysis may have been small relative to the universe of possible sources (i.e., all possible addiction therapy manuals, guidelines, or videos), our selection was purposive and based primarily on government-recommended materials (i.e., NIAAA, NIDA, SAMHSA). With that said, we do not know whether a larger sample would have yielded novel principles and/or practices. In addition, review of face validity with a third party rater showed that the observed principles and practices can be encoded with a high level of agreement, but future research is needed to empirically establish capacity for reliable fidelity assessment. Finally, the content analysis was a single rater procedure, which reflects an important limitation of this work.

In conclusion, we offer a novel resource with much pragmatic appeal to trainees, providers, and clinical supervisors who do not emphasize expertise in a single evidence-based modality, but who do find themselves delivering skills training content with AOD clients. We have characterized the process of skills training, as an integrative approach to client-centered teaching and behavioral practice. This review is the foundation for future work establishing training, fidelity monitoring, and skill maintenance tools for the principles and practices described here. Finally, the methods of this work can be applied to other cross-cutting or common therapeutic factors (e.g., relationship building, setting and monitoring treatment goals, providing psychoeducation, working with naturalistic support systems), providing a series of process-oriented guides for providers seeking to demonstrate evidence-based, addiction therapy skills with fidelity.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

The goal of this literature review and qualitative analysis was to operationalize the cross-cutting process of skills training for addictive behavior change.

Thirty source documents (i.e., therapy manuals, literature reviews, and government issued practice guidelines) and videos (i.e., therapy demonstration videos) were examined.

Ten principles and 30 therapeutic practices were identified, and suggest that skills training can be characterized as a client-centered approach to teaching and behavioral practice.

This work informs a fidelity-based approach to behavioral skills training that is applicable to a wide-range of alcohol or other drug (AOD) content topics, therapeutic modalities, and implementation settings.

Acknowledgement:

This research is supported by #AA027546, awarded to Molly Magill.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest:

none

Crosscutting with respect existence in or relevance too, other modalities. However, it was expected that skills training would have a more central emphasis in cognitive behavioral therapy or relapse prevention than in many other approaches.

While this work may be broadly applicable to adolescent AOD care, we did not explicitly sample adolescent evidence-based therapies.

In the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scale (Moyers et al., 2005; 2016) and the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (Miller, 2000; Houck et al., 2010), these indicators are referred to as relational global scales and technical skill behavior counts, respectively.

Because some manuals were derivations of others (e.g., Kadden et al., 1992 is based on Monti et al., 1989/2001), a fair amount of repetition was observed in the data.

See Supplemental Information for sample excerpts and subsequent principle or practice category codes.

References

* References marked with an asterisk used in literature and content analysis review

- Abraham C & Michie S (2008). A taxonomy of behavior change techniques used in interventions. Health Psychology, 27, 379–387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellg AJ, Borrelli B, Resnick B, Hecht J, Minicucci DS, Ory M, … & Czajkowski S (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. Health Psychology, 23(5), 443–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Carroll KM (1998). A cognitive behavioral approach: Treating cocaine addiction National Institute on Drug Abuse: Therapy Manuals for Drug Addiction [Publication No. (ADM) 98–4308)]. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Carroll KM, Ball SA, Nich C, Martino S, Frankforter TL, Farentinos C, Kunkel LE…Woody GE (2006). Motivational interviewing to promote treatment engagement and outcome in individuals seeking treatment for substance abuse: A multisite effectiveness study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 83, 301–312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2004). Substance Abuse Treatment and Family Therapy Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 39 HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15–4219. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2012). Brief Interventions and Brief Therapies for Substance Abuse Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 34 HHS Publication No. (SMA) 12-3952. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- *Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. (2017). Addiction Counseling Competencies: The Knowledge, Skills, and Attitudes of Professional Practice Technical Assistance Publication (TAP) Series 21 HHS Publication No. (SMA) 15-4171. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Becker KD, & Daleiden EL (2007). Understanding the common elements of evidence based practice: Misconceptions and clinical examples. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 46(5), 647–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, & Daleiden EL (2009). Mapping evidence-based treatments for children and adolescents: Application of the Distillation and Matching Model to 615 treatments from 322 randomized trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 566–579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Daleiden EL, & Weisz JR (2005). Identifying and selecting common elements of evidence based intervention: A distillation and matching model. Mental Health Services Research, 7(1), 5–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damschroder LJ & Hagedorn HJ (2011). A guiding framework and approach for implementation research in substance use disorders treatment. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 25(2), 194–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Epstein EE & McCrady BS (2009). Overcoming alcohol use problems: A cognitive-behavioral treatment program. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfried MR (2019). Obtaining consensus in psychotherapy: What holds us back? American Psychologist, 74, 484–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houck JM, Moyers TB, Miller WR, Glynn LH, & Hallgren KA (2010). Motivational Interviewing Skill Code 2.5 (MISC). Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico CASAA. [Google Scholar]

- Imel ZE, Wampold BE, Miller SD, & Fleming RR (2008). Distinctions without a difference: Direct comparisons of psychotherapies for alcohol use disorders. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 22(4), 533–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kadden R, Carroll KM, Donovan D, Cooney N, Monti P et al. (1992). Cognitive-Behavioral Coping Skills Therapy Manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series. Vol. 3 [Publication No. (ADM) 92-1895)] Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- Krippendorff K (2004). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- *Liese BS (2000). Cognitive therapy for addictions: Brief therapy for addictions series. United States: Allyn & Bacon [Google Scholar]

- *Lejuez CW (2018). Functional analysis and behavioral activation for substance abuse: Series II Specific treatments for specific populations. United States: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- *Marlatt GA (1997). Cognitive behavioral relapse prevention: Series II Specific treatments for specific populations. United States: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- *Marlatt GA (2000). Harm reduction therapy for addictions: Brief therapy for addictions series. United States: Allyn & Bacon [Google Scholar]

- *Marlatt GA (2005). Mindfulness for addiction problems: Series VI Spirituality. United States: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, & Gordon JR (1985). Relapse Prevention: Maintenance strategies in the treatment of addictive behaviors. New York: Guilford [Google Scholar]

- *Martino S, Ball SA, Gallon SL, Hall D, Garcia M, Ceperich S, Farentinos C, Hamilton J, & Hausotter W (2006) Motivational Interviewing Assessment: Supervisory Tools for Enhancing Proficiency. Salem, OR: Northwest Frontier Addiction Technology Transfer Center, Oregon Health and Science University. [Google Scholar]

- Martino S, Ball SA, Nich C, Canning-Ball M, Rounseville BJ, & Carroll KM (2011). Teaching community program clinicians motivational interviewing using expert and train-the-trainer strategies. Addiction, 106(2), 428–441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *McCrady BS (2000). Couples therapy for addictions: Brief therapy for addictions series. United States: Allyn & Bacon [Google Scholar]

- *McCrady BS, Wilson AD, Munoz RE, Fink BC, Fokas K, & Borders A (2016). Alcohol-focused behavioral couples therapy. Family Process, 55(3), 443–459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Meyers RJ & Smith JE (1995). Clinical guide to alcohol treatment: The community reinforcement approach. New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Atkins L, & West R (2014). The Behaviour Change Wheel: A Guide to Designing Interventions. London: Silverback Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, Johnston M, Francis J, Hardeman W, & Eccles M (2008). From theory to intervention: mapping theoretically derived behavioural determinants to behaviour change techniques. Applied Psychology: an International Review, 57, 660–680. [Google Scholar]

- Michie S, van Stralen MM, & West R (2011). The Behaviour Change Wheel: a new method for characterizing and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR (2000). Manual for the Motivational Interviewing Skill Code (MISC). Unpublished Manual.

- *Miller WR (2000). Motivational interviewing: Brief therapy for addictions series. United States: Allyn & Bacon [Google Scholar]

- *Miller WR Ed. (2002). Project Combine: Combined Behavioral Intervention. Unpublished Manual: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. [Google Scholar]

- *Miller WR (2007). Drug and alcohol abuse: Series III Behavioral health and health counseling. United States: American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- *Miller WR, Meyers RJ, & Hiller-Sturmhofel S (1999). The community reinforcement approach. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(2), 116–120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Yahne CE, Moyers TB, Martinez J, & Pirritano M (2004). A Randomized Trial of Methods to Help Clinicians Learn Motivational Interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1050–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, & Willbourne PL (2002). Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders, Addiction, 97(3), 265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Miller WR, Zweban A, DiClemente CC, & Rychtarik RG (1992). Motivational Enhancement Therapy Manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series. Vol. 2 [Publication No. (ADM) 92-1894)]. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- *Monti PM, Abrams DB, Kadden RM, & Cooney NL (1989). Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide. New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- *Monti PM, Kadden RM, Rohsehow DJ, Cooney NL, & Abrams DB (2002). Treating alcohol dependence: A coping skills training guide (2nd edition). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- *Monti PM & Rohsenow DJ (1999). Coping skills training and cue-exposure therapy in the treatment of alcoholism. Alcohol Research & Health, 25(2), 107–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Martin T, Manuel JK, Hendrickson SM, & Miller WR (2005). Assessing competence in the use of motivational interviewing. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 25(1), 19–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyers TB, Rowell LN, Manuel JK, Ernst D, & Houck JM (2016). The motivational interviewing treatment integrity code (MITI 4): Rationale, preliminary reliability and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 36–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2018). Principles of Drug Abuse Treatment. http://www.drugabuse.org

- *Norcross JC (2000). Stages of change for addictions: Brief therapy for addictions series. United States: Allyn & Bacon [Google Scholar]

- *Nowinski J, Baker S, & Carroll KM (1992). Twelve-Step Facilitation Therapy Manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treatment individuals with alcohol abuse and dependence NIAAA Project MATCH Monograph Series. Vol. 1 [Publication No. (ADM) 92-1893)]. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. [Google Scholar]

- *O’Farrell TJ, & Schein AZ (2000). Behavioral couples therapy for alcoholism and drug abuse. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 22(3), 193–215. [Google Scholar]

- QSR International Pty Ltd (2018). NVivo qualitative data analysis software (Version 12). QSR International Pty Ltd. https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo [Google Scholar]

- Rousmaniere T (2017). Deliberate practice for psychotherapists. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- *Smout M (2008). Psychotherapy for methamphetamine dependence: Treatment Manual Drug and Alcohol Services Southern Australia [ISBN 978-0-9803130-5-5]. [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2018). National Survey of Substance Abuse Treatment Services (N-SSATS) Data on Substance Abuse Treatment Facilities. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- *Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. (2019). Enhancing Motivation for Change in Substance Use Disorder Treatment Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series No. 35 SAMHSA Publication No. PEP 19-02-01-003 Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas DR, (2006). A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. American Journal of Evaluation, 27(2), 237–246. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE (2001). The great psychotherapy debate: Models, methods, and findings. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Wampold BE, & Imel ZE (2015). The great psychotherapy debate: Research evidence for what works in psychotherapy (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- *Witkiewitz K, Marlatt GA, & Walker D (2005). Mindfulness-based relapse prevention for alcohol and substance use disorders. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy: An International Quarterly, 79(3), 211–228. [Google Scholar]

- *Wubbolding RE (2000). Reality therapy for addictions: Brief therapy for addictions series. United States: Allyn & Bacon; [Pychotherapy.net] [Google Scholar]

- *Zweban JE (2000). Integrating therapy with 12 step programs: Brief therapy for addictions series. United States: Allyn & Bacon; [Pychotherapy.net] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.