Abstract

This opinion article results from a collective analysis by the Editorial Board of Food Security. It is motivated by the ongoing covid-19 global epidemic, but expands to a broader view on the crises that disrupt food systems and threaten food security, locally to globally. Beyond the public health crisis it is causing, the current global pandemic is impacting food systems, locally and globally. Crises such as the present one can, and do, affect the stability of food production. One of the worst fears is the impacts that crises could have on the potential to produce food, that is, on the primary production of food itself, for example, if material and non-material infrastructure on which agriculture depends were to be damaged, weakened, or fall in disarray. Looking beyond the present, and not minimising its importance, the covid-19 crisis may turn out to be the trigger for overdue fundamental transformations of agriculture and the global food system. This is because the global food system does not work well today: the number of hungry people in the world has increased substantially, with the World Food Programme warning of the possibility of a “hunger pandemic”. Food also must be nutritious, yet unhealthy diets are a leading cause of death. Deepening crises impoverish the poorest, disrupt food systems, and expand “food deserts”. A focus on healthy diets for all is all the more relevant when everyone’s immune system must react to infection during a global pandemic. There is also accumulating and compelling evidence that the global food system is pushing the Earth system beyond the boundaries of sustainability. In the past twenty years, the growing demand for food has increasingly been met through the destruction of Earth’s natural environment, and much less through progress in agricultural productivity generated by scientific research, as was the case during the two previous decades. There is an urgent need to reduce the environmental footprint of the global food system: if its performances are not improved rapidly, the food system could itself be one main cause for food crises in the near future. The article concludes with a series of recommendations intended for policy makers and science leaders to improve the resilience of the food system, global to local, and in the short, medium and long term.

Keywords: Global food security, crises, spatial scales, time characteristics, system resilience, earth system, environmental footprint

Introduction

The global food system is “a vast machine” (Edwards 2010). It is a complex, human-made structure inherited from many centuries of social, cultural, economic and technological evolution. In a world where globalisation has been steadily accelerating, this structure remains heterogeneous, extraordinarily diverse, and retains features reflecting its local history. The global food system involves many different, nested scales and many inter-linked, non-linear processes involving feedback and feedforward effects (Pinstrup-Andersen and Watson 2011). It is because of the complexity of these scales and processes that the system reveals itself to be extremely fragile in some of its parts, and yet extraordinarily resilient in others. This has been shown in many crises humanity has faced including conflicts, environmental disasters, the global food price crises of 1974 and 2007–2008, economic downturns such as the world Great Depression of the 1930s, and pandemics of human diseases, including the plagues of the European Middle Ages and of Imperial China, as well as the current covid −19 epidemic.

There are different ways to consider the global food system. One consists in considering a series of components that contribute to food security. These components may be seen as successive stages in the process (De Wit and Goudriaan 1978) towards the achievement of food security, from production, to storage, to transport, to economic access, and to consumption (Desker et al. 2013; Rötter and Van Keulen 2007; FAO-ESA 2006; FAO-IFAD-WFP 2013; HPLE 2017; Savary et al. 2017). Another more recent view considers three main constituents of food systems (the food supply chain, the food environment, and consumer behaviour), in connection with diets, livelihoods and environmental outcomes, and with an emphasis on a set of drivers that influence food systems: biophysical and environmental, innovation and technology, policies and economics, sociocultural, and demographic (Swinburn et al. 2013; HPLE 2017; Turner et al. 2018). The two views are different and do not completely overlap. The second for instance emphasizes the factors and forces leading to observed diets, while the first strongly emphasizes the production of food in its many processes and its challenges. We shall use in the following a hybrid of the two views, which considers the components of the first, and the drivers of change of the second view.

We can consider the global food system in two main parts: a food production system (which translates into food being generated) and a food consumption system (which translates into food being part of diets). The food production system is a mosaic of very diverse production units distributed over the world (Fresco and Westfal 1988; Cassman et al. 2005). From one extreme to another, these production units include the large-scale commercial farms of the global North, with their high level of mechanisation and inputs (synthetic and also biological, with highly selected and specialised seed) as well as the small-scale, smallholder farms of the global South, with their large labour force, their crop diversity, the frequent inclusion of livestock in agriculture, and their limited reliance on external inputs. In the second part, the food consumption system where food access and utilization are of utmost importance, we can contrast “staple” food and “nutritious” food, which are both essential to human health, and the recent advent of ‘ultra-processed foods’ which are not (Monteiro et al. 2018). Staple food is mostly represented by grain that has limited water content, is easily transported, stored, and traded, involving relatively simple supply chains, sometimes over very long distances. Nutritious food is far more diverse, including meat and fish, dairy, eggs, fruits, and vegetables. It contains much more water and is much harder to transport, store, and trade. It involves very diverse, complex, and specialised supply chains, generally over short distances, owing to the perishable nature of products.

The global food system thus involves many components and processes operating at many spatial scales and these components have different time characteristics (De Wit and Goudriaan 1978). The current Covid-19 crisis makes this apparent: while small and medium food businesses in Western Europe have had a few weeks to adapt, the European Union needs months to shape new financial instruments and policies to assist national and within-country regional economies. For a rickshaw driver in the suburbs of Delhi, however, the time-step is less than a day: not finding a job in the morning means being hungry in the evening. Finding a proper way to consider processes that have so many different time constants is a major challenge; this, however, is essential to understanding how the system works and how it may react to both continued stress and to interventions.

The linkages between human needs, agriculture and the environment are the subject of critical research and assessment today (see, e.g., Hazell and Wood 2008 and Willett et al. 2019for an overview): while agriculture provides food (and fibre and materials) to humans, unsustainable agriculture depletes resources and destroys the environment, rendering it in turn hostile to humans and unsuited to agriculture. Humans appropriate a large fraction of photosynthesis products in the biosphere (Rojstaczer et al. 2001), and the global food system is the premier cause of global environmental change (Willett et al. 2019; see Box 1: Environmental footprint of food production): while the current functioning of the global food system constitutes in itself a threat to the earth system (IPCC - Climate Change and Land 2019), addressing its flaws constitutes a compelling angle to prevent future crises, including food crises. In the following, we shall therefore include elements pertaining to the links between global food and the environment.

Box 1.

Environmental foot print of food production

| The global food system has a huge impact on the environment with nearly 8 billion people to be fed and still counting (Gerland et al. 2014). The current functioning of the global food system leads to extraordinarily expensive and unsustainable practices towards the environment, not only causing biodiversity loss and accelerating climate change (see, e.g. West et al. 2010), but also resulting in exceedance of a number of planetary boundaries (Rockström et al. 2009), hence, jeopardizing the achievement of several of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). | |

| To meet increasing food demands, we first need to grow more food on the current cropland (i.e., narrowing yield gaps; Cassman and Grassini 2020). This is because we are already farming the best soils and expanding into new areas destroys natural habitats or has other environmental impacts. Next, we need to grow food more efficiently. Globally, agriculture is the biggest contributor of greenhouse gas emissions and water use, as well as a major driver of water quality degradation and habitat loss (e.g., Willett et al. 2019). Moreover, we must use what has been grown more efficiently. In some western countries the main share of all calories produced on croplands is used as livestock feed. It takes many feed calories to produce a calorie of meat (Eisler and Lee 2014; Poore and Nemecek 2018). Further, since 2000, the amount of maize production used for ethanol jumped from a few percent to more than 30 percent. Finally, somewhere between a third and half of the food we produce gets wasted in the food service industry, retailers, and our kitchens. |

Collectively, human diseases generate another set of connecting loops (e.g., Rohr et al. 2019) in a complex system, such as these: (i) food production contributes to population growth; (ii) diseases suppress population growth; (iii) high population densities favour diseases; (iv) food production (agriculture) favours pathogen emergence; and (v) adequate nutrition helps suppress diseases. We do not address the details of the complexity of the human health - agriculture - environment - disease interactions (see Box 2: Human disease and food security in sub-Saharan Africa), but nevertheless consider the possible consequences of human pandemics on the global food system, with an emphasis on the vulnerability points of this system.

Box 2.

Human disease and food security in sub-Saharan Africa

| Human infectious disease has long been considered to be an especially severe burden in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis, malaria, dengue and Chikungunya, diarrheal diseases including cholera, haemorrhagic fevers such as Ebola, hepatitis, meningococcal meningitis, schistosomiasis, and bacterial and viral lower respiratory tract infections, are among the most important infectious diseases of humans in SSA (WHO 2020; Fenollar and Mediannikov 2018). Covid-19 infection is a newcomer in this complex landscape. | |

| In much of SSA, the human disease burden on smallholder agriculture and on the food security of rural and urban households severely affects multiple aspects of food systems (Ericksen 2008; Pinstrup-Andersen 2012; Aberman et al. 2014). Human mortality and morbidity due to disease recurrently compromises farmers' decision making and reduces both the availability and productivity of labour. Labour inputs into SSA smallholder agriculture are very high and a shortage of labour from land preparation through to harvest processing for marketing, but especially for adequate weeding, is a widespread and severe constraint to crop production (e.g., Ogwuike et al. 2014; Leonardo et al. 2015). | |

| Householder time allocations are disrupted and income is reduced due to a need to care for the infirm and for medications; the amounts and diversity of foods available can be severely affected, as can the quality of food preparation for meals, affecting all members of households. Effects extend to urban areas, which can suffer reductions in the supply of agricultural products and in market demand for foods, as well as direct effects of disease (e.g. Crush et al. 2011). Consequences for human nutrition and health, and on livelihoods and welfare throughout households and communities, can be severe and persist well after a decline in the direct effects of a disease (Barnett et al. 1995; Murphy et al. 2005). | |

| HIV/AIDS has been especially devastating in Southern and Eastern Africa. Substantial research over several decades has demonstrated deep-seated, widespread, and prolonged effects of the disease on food production systems, and on food and livelihood security in the region (Gillespie 1989; Barnett et al. 1995; de Waal and Whiteside 2003; Murphy et al. 2005; Masuku and Sithole 2009; Crush et al. 2011; Ncube et al. 2016). Additional to effects on agricultural production and food supply, individuals living in households afflicted by HIV/AIDS consume fewer calories, have less diverse diets and poorer nutrition and health (e.gAberman et al. 2014; Ncube et al. 2016). The consequences of HIV/AIDS for food, nutrition and livelihood security have been manifest throughout society in Africa, in both urban and rural settings (Crush et al. 2011; Aberman et al. 2014), leading to numerous interventions, including food and nutrition policies (see Haddad and Gillespie 2005; Aberman et al. 2014). The impacts of the spread of covid-19 in SSA are just beginning, but it will only add to an already very serious overall situation. |

Major generic phases in the generation, access and use of food -- components of food security -- may be distinguished in food systems. The food security literature typically considers six components (Desker et al. 2013; Rötter and Van Keulen 2007; FAO-ESA 2006; FAO-IFAD-WFP 2013; HPLE 2017; Savary et al. 2017):

Component 1: Primary production of food: refers to the primary production of food, including the potential of any system to generate food over the long-term;

Component 2: Stability of production: refers to the ability of a food system to generate a regular supply of food, including its resilience to shocks of many kinds;

Component 3: Food reserves and stockpiles: pertains to the regular in- and outflows, to and from, storage systems, including the reserves that can be established at the local and national levels;

Component 4: Physical access to food: refers to physical infrastructures, including railways, canals, and roads, as well as physical market places where food may be channelled, traded, and purchased by individuals;

Component 5: Economic access to food: pertains to the ability of individuals and households to purchase food, and includes elements pertaining to the price of food and to household income which is available for food purchase;

Component 6: Diets: refers to the ensemble of food utility, including the nutritional value, qualitative and quantitative, towards households and importantly towards individuals including the elderly, the children, and women.

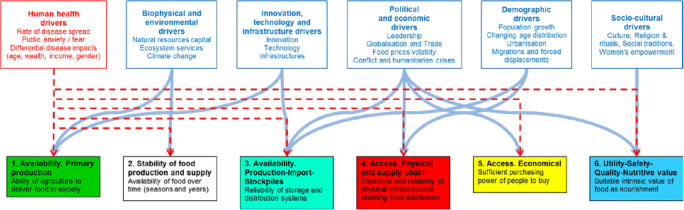

These components may be considered in their relations with a number of drivers (HPLE 2017; Fig. 1); and these drivers may be considered in turn in assessing the vulnerability of the global food system: biophysical and environmental; innovation and technology; political and economic; demographic; and socio-cultural. We shall use in this article the above set of six food security components under the collective influence of this set of drivers, among which we distinguish an additional one, in the form of a human health driver (Fig. 1), to account for the rate of disease spread, the public anxiety and fear, and the existence of differential disease impacts, including age, wealth, income, and gender. As suggested in Fig. 1, we form the hypothesis that all six components of food security can be affected by this human health driver.

Fig. 1.

Drivers and components of food security. Modified from: FAO-ESA 2006; Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO), International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) and World Food Programme (WFP) 2013; Desker et al. 2013; HPLE 2017

While this article is being drafted in May and June 2020, and while the covid-19 crisis is still unfolding, making it very hard to anticipate its full consequences, thousands of articles have already been published on the covid-19 crisis; many thousands will follow. This article is of course motivated by the current crisis; but we refer to past events, as well as to already available theories and concepts. It is meant to provide a series of lines of thoughts to better understand the crisis from a food security standpoint. With this aim, the article is organised along a main text, where we address impacts on food security in a systematic manner, and a series of boxes, where we briefly address some additional aspects which might be overlooked in a broad, sweeping perspective, but which we feel are relevant, both in terms of understanding and illustrating impacts.

Mapping vulnerability points in food systems

The global food system is so complex, so diverse, that exploring all the possible ways through which any crisis could affect it would be futile. The current crisis generated by a pandemic offers the possibility to consider a series of paths to analyse impacts and detect vulnerability points. In the following, we therefore take the covid-19 crisis as a current example, and expand our analysis to consider the vulnerability points of the global food system to future crises. The vulnerability of food systems, local to global, may be analysed along two directions: over time, and across food security components. Considering the time dimension, disruptions in the food system may be scaled considering impacts in the short- (0–3 months), medium- (3–12 months), and long-term (1 year or more). These time-ranges are suitable to account for the many time characteristics involved in food systems.

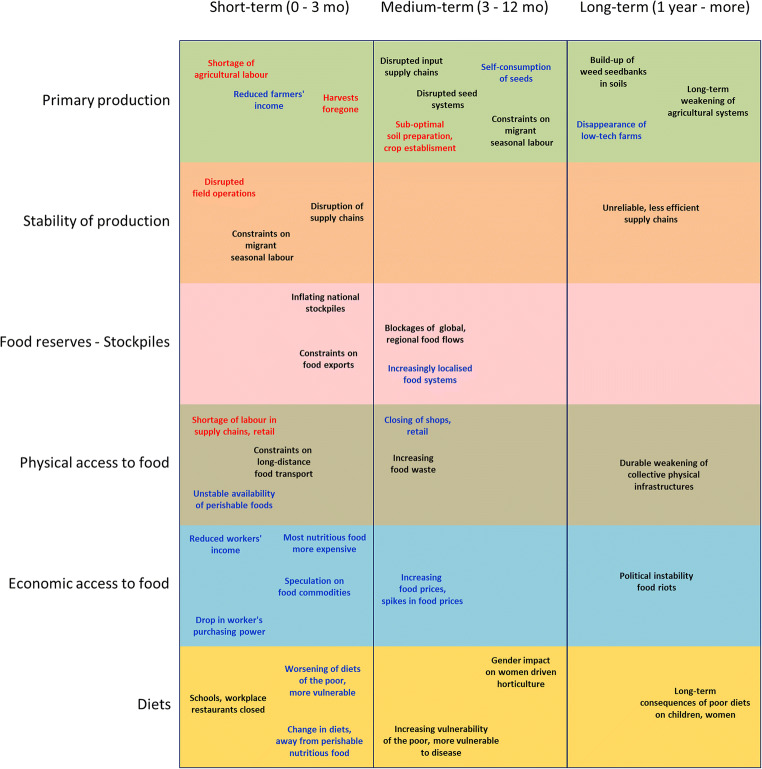

Impacts of crises, as exemplified by the covid-19 pandemic, may be directly the result of disease itself, and of the reduction of labour it causes, especially in the two production components (Primary and Stability, Components 1 and 2), but also in many other places in the global food systems, notably the physical access (Component 4). Some indirect (but potentially rapid) impacts are economic in nature. These can be the immediate drop in wages in the farm sector (causing a perturbation of Stability, Component 2), in the retail sector (Components 2 and 4) and result in a rapid reduction in food affordability (Component 5), especially with respect to more expensive nutritious food (Component 6). Some impacts may be policy-related. One immediate policy implemented to control an epidemic can be a lock-down of households, of markets and shops, of factories and offices, with a number of rapid consequences on all six components. Other policies may have severe consequences in the medium term, such as the sudden build-up of national stockpiles and restrictions of trade (Component 3). Yet other policies can be implemented to mitigate impacts, re-start stranded economic processes or even re-orient economic systems. One must also consider long-term consequences. The economic downturn may be severe; it may affect the ability of the agricultural system to deliver food (Component 1), because farms are abandoned, seed stocks are depleted or of low-quality, infrastructure such as irrigation canals are in disarray, or because the seed-bank of weeds in soils has increased beyond control. Figure 2 is an illustration of possible impacts, which we map according to time-scales and to the nature of food security components affected.

Fig. 2.

Mapping the impacts of crises on food security: a conceptual overview of the impacts the Covid-19 pandemic could have. Impacts that are directly caused by human disease are shown in red; impacts that have mainly economic origins are shown in blue; impacts that have combined human disease and economic, or other causes, are shown in black

The six components of food security will be addressed subsequently below. In a context of crisis, and especially when making reference to the current covid-19 crisis, it is logical to think of Component 2 first. What is seen and perceived first is a disturbance from the usual, especially a disturbance in production; it is thus reasonable to first think of the shock that the crisis generates on the stability of a food system, starting with the stability of production. The six components are thus addressed below, starting with Component 2 “Stability”.

Stability of food production

Any disruptions of primary food production in the major bread-baskets of the world could be devastating (Foley et al. 2011; Challinor et al. 2015; Asseng et al. 2015), especially if the disruptions were to occur simultaneously in several of these breadbaskets (Trnka et al. 2019; Kornhuber et al. 2020). The bulk of food production of the major staples (maize, wheat, rice, potato and soybean) is located in just a few countries: Argentina and Brazil, Australia, China, the European Union, India, and the USA (Hazell and Wood 2008; Foley et al. 2011; West et al. 2014). Reduced food production in the global bread baskets would hit urban and rural poor consumers most through increases in food prices (Tadasse et al. 2014; Pinstrup-Andersen 2014). While these staple foods, which are vital to food security, have been the focus of agricultural policies, the supply of nutritious foods has generally been left to the forces of markets.

By mid May 2020, two months after economies had been largely shut down worldwide in an effort to combat the spread of the covid-19 pandemic, the stability of primary agricultural production at the global scale had already been affected. However, there are considerable regional differences in how production levels of different agricultural commodities have been affected, and how and to what extent this has played out in terms of food security.

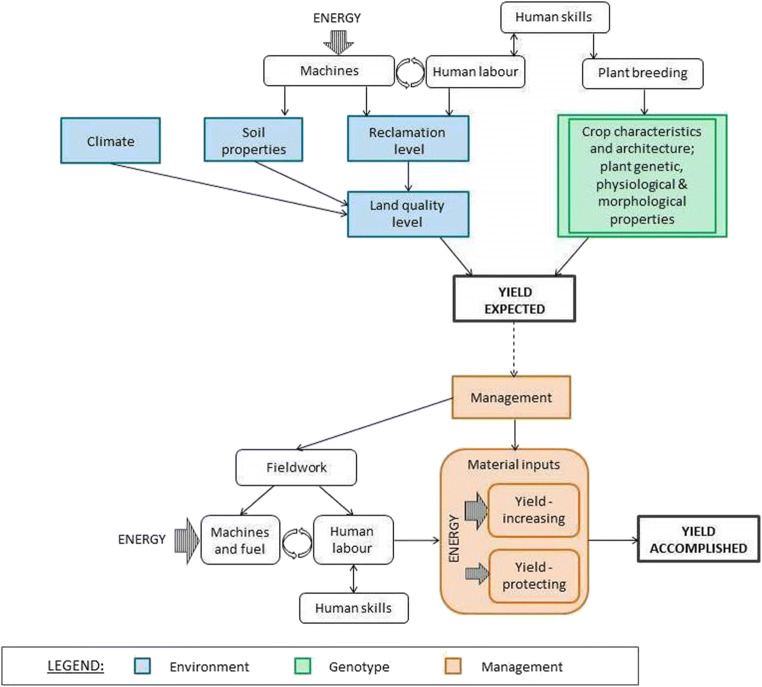

In order to explain the impacts of a shock such as covid-19 on short, medium, and long-run agricultural productivity and stability (or what impacts a similar shock may have), we first need to look at the main factors and drivers of the agricultural production process (Fig. 3) and their relative importance in the different farming systems around the world. In the short term, the key words are: shortage of agricultural labour, reduced field operations, and the need to protect the health of farmers and farm workers.

Fig. 3.

Schematic of the agricultural production process (modified from Van Keulen and Wolf 1986, p. 7)

Availability of sufficient skilled human labour is crucial to keep the production process going. In this, humans act in the role of farmers or farm workers, planning and carrying out fieldwork activities such as land preparation, planting, weeding or harvesting. They are also suppliers of material inputs (agribusiness providing seeds, fertilizers, biocides, machinery, etc.), agricultural extension officers providing advice on new technologies and management practices, sellers of their produce to traders or transporting agents to bring produce to the market. The functioning of humans in these roles depends on good health conditions, which may be affected by disease (See Box 2: Human Disease and Food Security), including covid-19. As has been learned from the HIV/AIDS epidemic (Barnett et al. 1995; Aberman et al. 2014), which especially hit populations in low income countries of sub-Saharan Africa, a shortage of healthy farmers and farm labourers can severely disrupt field operations, considerably reduce agricultural production and increase food insecurity at local levels (Rötter et al. 2007).

What matters in the first place is how much the availability of required agricultural labour is affected by:

-

(i)

constraints on the health of farmers and farm workers,

-

(ii)

restricted local mobility (e.g., no or limited access to the fields), or

-

(iii)

disrupted mobility of seasonal labourers that provide the required labour force at times of peak labour requirements.

The last can affect both the production of staples such as wheat and rice, and the production of high value, nutritious, commodities. Such disrupted mobility of seasonal labourers has happened in the past and is happening now under Covid-19 (See Box 3: Examples of short term impacts of epidemic-induced shortage of agricultural labour). This is observed for example in the harvest of high value commodities such as asparagus in Germany by migrant workers from eastern Europe or in the harvest of cereals in the intensive rice-wheat systems of the western part of the Indo-Gangetic plains by migrant workers from states of eastern India (Aggarwal et al. 2001). Disruption in the mobility of seasonal labourers obviously has consequences other than just a disruption in stability of production: this has massive and immediate impacts on the income and welfare of poor, vulnerable, and displaced people, as well as the families to whom they may send remittances (Regmi and Paudel 2017; Obi et al. 2020).

Box 3.

Examples of short term impacts of epidemic-induced shortage of agricultural labour

| The current impacts the covid-19 epidemic is having on agricultural labour and on the stability of food production can be illustrated by a few examples: | |

| • Finland: when the lockdown was loosened in Finland (April 2020) and school children were again admitted to schools, many parents of farm families did not allow children to go to school in fear of them being infected and then infecting adult family members or Finnish farm workers – which in this coronavirus situation would have been detrimental since the usually available farm workers from other Baltic countries, such as Estonia, were still prevented from entering Finland. | |

| • South Africa: at the time (mid-May) of writing this piece, the complete lockdown (level 5) that prevented farm workers from entering the tree orchards for harvesting macadamia nuts, avocado, or other high value commodities, has been loosened (to level 4) and now again allows almost normal farm operations. | |

| • Western Europe (France, Germany): in spite of lock down measures including the prevention of crossing national borders and quarantine rules, the health of migrant workers from Eastern Europe and local workers was compromised; e.g. workers from Poland, Romania, etc. were allowed to enter Germany and France in April for the harvesting of high value crops (such as asparagus). | |

| • USA and Mexico: Suspension of USA temporary worker visas and near closure of the Mexico-USA land border (the most transited international border in the world) means that several hundred thousand agricultural workers from Mexico and central America are unable to take up their normal seasonal work in the USA with major consequences for the management, harvest and marketing of numerous high value crops, leading to shortages and high prices, as well as hardship in home communities. |

Persistently unreliable supply chains (inputs and outputs from farms) would constitute major cause for lasting instability in food production (Fig. 2). For the rural poor producers, the associated reduced farm income in the short-term will lead to food insecurity at the farm household level, and may lead some to change their livelihoods in the longer-term (Kuiper et al. 2007). Farms where human labour is critical, such as low-tech farms of subsistence agriculture, are likely to be most vulnerable (Fig. 2) and their disappearance would in turn lead to a reduction in food security.

Reduction of primary production

In the longer term, impacts of a crisis may affect the amounts and types of foods produced over multiple growing seasons. In a pessimistic scenario, this might lead to a reduction in production in the world’s bread baskets: this is where a crisis in the production component of the food system would have the worst global effects (West et al. 2014; Trnka et al. 2019; Kornhuber et al. 2020). For instance (Fig. 2), the shortage of agricultural labour combined with constraints in seasonal labour affecting the stability of food production may also translate into reduction in production in the long term. Figure 2 provides a number of possible impacts that may result in a reduction of production.

The impact of a shortage in human labour on primary production may also depend, in the medium- to long-term (Fig. 2), and in some agricultural systems, on the extent to which human labour can be substituted in the production process by machinery and fuel (Fig. 3). Among the world’s bread baskets, The European Union, the USA, Argentina and Brazil, and Australia are the main exporters of calories (e.g. Challinor et al. 2015; Trnka et al. 2019). The level of mechanization in these regions is already high.

Agriculture requires infrastructure, both material (access roads, irrigation systems, storage equipment, machines and repair shops) and non-material (credit system, advisory networks, cooperatives, input retail). These infrastructure components connect the food production system with the rest of the food system: inputs (material, such as, e.g., seeds, fertilisers, water; and non-material, such as, e.g., technical advice, pricing information) and outputs (the products of agriculture, to be marketed in many different ways along diverse food supply chains). Infrastructure needs continuous support and maintenance, at a cost often borne by agricultural activities. In the medium term, a shortage of agricultural labour can result in forgone harvests or serious crop production shocks and crop failures, leading to long-term reduction in production potential.

Agriculture also depends on natural capital, in different forms. One example is the bio-physical capital of soils, where weed seed-banks may increase beyond control (e.g., Dekker 1999; Chauhan et al. 2012). Another form of biological capital is genetic, represented by seeds: good quality seed is an essential component of good crop performances: this, too, is at stake in times of crisis (Box 4: Covid-19, seed security and social differentiation). Another example involving both the biological capital (host plant resistance genes) and non-material infrastructure (farmers’ advisory systems, farmers’ associations, and ICT) is the management of crop health. Plant pathogens and pests are persistent, major, and yet chronically overlooked causes of reduced food production both in quantity (reduced yields) and in quality (reduced nutritional value, or accumulation of compounds toxic for humans). The agricultural world has seen many pandemics of pathogens of crop plants (see Box 5: Pandemics of plant diseases and food security), and it seems that these pandemics are becoming much more frequent owing to global exchanges.

Box 4.

Covid-19, seed security and social differentiation

| For the poor, covid -19 represents yet another uncertainty. Society’s poorest are commonly considered the least food secure, facing high vulnerability and low resilience, as is also described in relation to climate change and its interacting factors (Kaijser and Kronsell 2014). The concept of intersectionality highlights that the poorest are often disadvantaged across a number of interacting social dimensions (ibid), subjecting them to different mechanisms of marginalization and clusters of interlocking disadvantages (Cleaver 2005). Women are disproportionately afflicted because they typically make up more than half of this fraction of society. | |

| Seed security directly determines food security for many smallholder farmers in developing countries (McGuire and Sperling 2011). Saving one’s own seed for the next sowing is the most common seed sourcing practice of smallholder farmers across the majority of food crops. At first thought one may expect self-provisioning of seed to be a relatively covid-19 tolerant practice – which justifies advice to stimulate seed saving practices. However, for the poorest smallholders, food and seed security are also closely intertwined in another way: because usually food production falls short of household consumption demands and cash constraints are pressing, next year’s seed is at risk of being eaten or sold outright. This explains why many of the poorest farmers end up sourcing seed from neighbours, family, or local markets when planting time arrives (e.g. Tadesse et al. 2016). Saving one’s own seed is a practice that only the better-off in the community can afford. It is also often assumed that covid -19- related disruptions in food production, seed security, and other livelihood impacts, would increase people’s reliance on social networks. If this were the case, the poorest would again face a disadvantage. In addition to acting as safety nets, social ties also represent a set of social obligations which are often restrictive (Cleaver 2005); and this applies too for seed sourcing (Coomes et al. 2015). Off-farm income generation (e.g. day labour, local construction jobs, seasonal migrant labour, and remittances) are important lifelines for many of the poorest. The impact of covid-19 on these sources of income will disproportionately affect the poor. |

Box 5.

Pandemics of plant diseases and food security

| The impact of plant disease epidemics on food security (Strange and Scott 2005) constitutes a field of research of its own, where chronic disease vs. acute disease epidemics may be distinguished (Savary et al. 2011). The latter may be caused by pandemics of plant diseases, which may affect both non-cultivated and cultivated plants (Zadoks and Schein 1979). Much debate exists as to the causes of famines in relation to plant disease (Zadoks 2008). While in many cases, deficient physical infrastructure -- roads, storage systems (hampering physical access to food) combined with the affordability of food (economic access), and the policies leading to these deficiencies, are considered the ultimate causes, plant diseases have been documented as the proximate causes of famine in several instances. The relations between plant disease pandemics and food security have especially been discussed in the case of the Potato Late Blight and the Famine of Ireland in the 19th century (Bourke 1964; Fraser 2003). The Bengal Famine of the mid-20th century was associated with the brown spot disease, a chronic disease of rice (Padmanabhan 1973). |

In the long-term, a severe crisis may thus weaken agricultural systems, especially those involving resource-poor farmers confronted by both food shortage and drastically reduced farm income (Fig. 2). This might lead many smallholders to lose their livelihoods and exit farming (Kuiper et al. 2007), further damaging the fabric of agricultural systems.

The global food system has known many crises. The Covid-19 crisis may turn out to be the trigger for overdue fundamental transformations of agriculture and the global food system, and also in other sectors such as energy and industry. In a longer term, a transformation of the global food system may be unavoidable, since the agro-ecosystems upon which food production and stability are based will otherwise be increasingly damaged by environmental degradation in its many forms, including effects of climate change (West et al. 2014; Campbell et al. 2017; Herrero et al.2020).

The implicit or explicit backdrop in these analyses is the stagnation of crop yield and the overall decline in total factor productivity (Ray et al. 2012; Ramankutty et al. 2018). The analysis of crop performances of 1501 lowland rice farmers’ fields across tropical Asia (from India to the Philippines, and from Indonesia to China) over a period exceeding 20 years (1987–2011) for example indicates (1) a non-significant change in crop yield (at about 4.5 t.ha−1), (2) a large increase in mineral fertilizer inputs; (3) a large increase in insecticide and fungicide inputs; (4) a shortening of fallow periods; and (5) limited, often non-significant, changes in crop losses to pests, pathogens, and weeds (Savary et al. 2014), thus indicating a steady drop in total factor productivity in the production of the world’s first staple during the post-Green Revolution.

Over the years, agricultural diversification has been increasingly considered as a powerful way to: (1) enable resource-poor farmers to exit subsistence-only agriculture; (2) stabilise agricultural performances and enhance the resilience (economic, agronomic, environmental) of agricultural systems; and (3) reduce the dependence of production on chemical inputs, especially fertilisers and pesticides. A case in point is sub-Saharan Africa, today a major concern for food security (Van Ittersum et al. 2016), where great hopes are grounded on ecological intensification (Van Ittersum et al. 2016) and a diversification process (Waha et al. 2018). Indeed, agricultural diversification at multiple scales (Eisler and Lee 2014; Kahiluoto et al. 2014; Waha et al. 2018) is considered an important step (Herrero et al. 2020; Rockström et al. 2020) toward making the global food system more resilient (Box 6: Climate change and food crises) to a range of shocks at different spatial and temporal scales. Agricultural diversification may take many shapes, from plant to field, to farm and region, and to the national scale and beyond. At regional and national scales, this may generate increased independence from food imports and externally sourced inputs, while increasing food self-sufficiency (e.g. Kahiluoto et al. 2014; Webber et al. 2014; Herrero et al. 2020).

Box 6.

Climate change and food crises

| The current global food system, and in particular its production component, are at risk of shocks from extreme weather events such as drought, heat-waves, heavy storms and flooding (Coughlan et al. 2014). Drought, in particular, is a major driver of crop production shocks (Challinor et al. 2015; Lesk et al. 2016). An increase in the frequency of extreme events resulting from global warming and changing rainfall patterns can already be seen in historical weather records (Dai 2013; Coumou and Rahmsdorf 2012; Challinor et al. 2015); moreover, global climate models predict that both the frequency and severity of weather extremes will further increase (Rummukainen et al. 2012). There is also accumulating evidence that shifts in the climate system are already responsible for the currently higher frequency and severity of such extreme events (Kornhuber et al. 2019). The evidence pointing to a higher likelihood for the simultaneous occurrence of such extremes in the major breadbaskets is accumulating as well (Kornhuber et al. 2020). So far too little effort has been devoted to quantifying the risk of simultaneous multiple failures in the world's breadbaskets, with few exceptions such as the impacts of simultaneous drought on global wheat production (Trnka et al. 2019). | |

| In the long run, climate change with marked shifts in temperature regimes and rainfall patterns will create additional risks to agricultural production, e.g., through novel combinations of abiotic and biotic stresses (Rötter et al. 2018). This is especially detrimental for areas where crops are currently grown at or beyond temperature thresholds or aridity thresholds (Kahiluoto et al. 2014). Climate change will affect all dimensions of food security (Wheeler and Von Braun 2013). | |

| As a result of the uncertainties in climate models and emission scenarios and in the imperfections of agricultural impact models (e.g. Rötter et al. 2011), there are great uncertainties in projecting climate change impacts on agricultural production, especially at the regional and local scales where farmers act (Rummukainen 2012; Tao et al. 2018). Uncertainty in future conditions will require new ways of managing cropping systems which must be made more flexible and adaptable to more volatile and occasionally extreme weather (Kahiluoto et al. 2014). | |

| Adaptation to climate change calls for resilient, knowledge-intensive yet resource-frugal cropping systems that are efficient in converting resources into stable crop yields at acceptable levels (Webber et al. 2014). Although the current pandemic-driven crisis profoundly differs in its causes from the climate crisis, both point at inadequacies of the current production systems, and to solutions requiring changes in food production systems towards resilience, as opposed to short-term performances. |

Disruptions in the import and export of food, and in national stockpiles

Covid −19 has made global food trade more difficult (Box 7: Grain export restriction timeline), both by reducing direct trade in food and agricultural inputs and by reducing the income generated through trade activities on which millions rely for their food security. The pandemic and the policy responses to it may lead to price decreases, price increases, or U-shaped patterns if demand shocks would matter more in the short run and supply reductions grow increasingly large over time.

Box 7.

Grain export restriction timeline

| • Mar 24 – Vietnam imposes rice export ban until June. | |

| • Mar 27 – Kazakhstan imposes export restrictions on wheat, carrots, and cabbages and a ban on sugar, potatoes, and some vegetables. | |

| • Apr 5 – Cambodia bans white rice exports; Ukraine restricts wheat exports through May, but this restriction is not binding. | |

| • Apr 10 – Vietnam change rice export ban to restriction (500,000 ton export quota). | |

| • Apr 26 – Russia imposes wheat export ban until July 1. | |

| • Apr 30 – Vietnam removes all rice export restrictions. | |

| • May 20 – Cambodia allows white rice exports. | |

| Additional information may be found at IFPRI’s Food Trade Policy Tracker: https://www.ifpri.org/project/covid-19-food-trade-policy-tracker |

Pandemics and the economic shutdowns they may cause decrease a citizenry’s demand for foreign-produced food and inputs through: loss of income, fear of foreign contagion, changes in where food is consumed, and dietary changes (see below). Additionally, border closures and curfews delay imported products entering a country. In West Africa, meat and other highly perishable foods typically cross borders at night, only to be stopped by curfews, additional regulations designed to protect against the spread of disease, and a 30% increase in bribe collection (Bouët and Laborde 2020). The labour shortages and bottlenecks in supply chains (see below) decrease the extent to which imports or exports are able to flow through the economy, adding to spatial price variance, food waste, and instability as has occurred even in the absence of crisis conditions (Bassett 1988; Dorosh et al. 2009; Yaffe-Bellany and Corkery 2020).

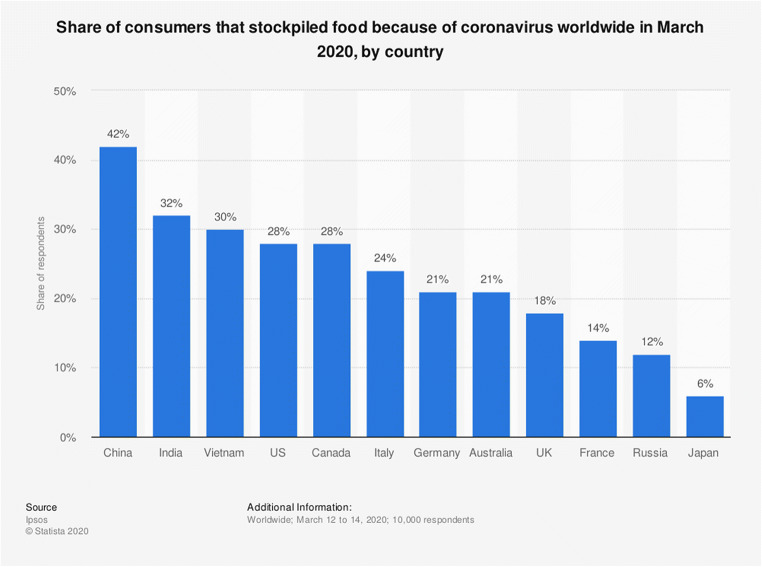

The global grain stocks in 2020 are twice as high as they were during the 2007–2008 food price crisis (Rötter and Van Keulen 2007; Torero 2020). Despite these more comfortable circumstances, many governments are again increasing their stocks through higher import orders and lower import tariffs. Some consumers are also increasing their household food storage (Fig. 4). This increased food hoarding, public and private, increases the demand for some products, and hence their prices. Sen et al. (2020) urge governments to distribute national stocks to needy families.

Fig. 4.

Proportion of consumers that stockpiled food at home because of Covid-19 in March 2020, by country. Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1105759/consumers-stockpiling-food-by-country-worldwide/

As they did during the 2007–2008 food price crisis, a number of governments have established export restrictions and bans (see Box 7: Grain export restriction timeline). Despite warnings from the FAO, WHO, and WTO (Joint Statement 2020; Torero 2020) that what the world needs now is greater cooperation and coordination, even countries with higher than expected food production have been closing their borders to exports. Export restrictions have been shown to significantly increase global food prices to the detriment of net food consumers (Headey 2011; Coughlan et al. 2014; Fellmann et al. 2014). Private sector firms and workers may voluntarily lockdown because of illness, fear of contagion, or fear of delays and harassment by police if they cannot readily prove their exempt status.

In the longer run, trade barriers and supply chain bottlenecks prevent needed agricultural inputs from arriving in markets in a timely manner for the next planting season. This has decreased and could continue to decrease production, reduce the stability in supply, and increase hunger and food insecurity for some time. The net effect of many governments’ policy responses so far may well produce higher food price volatility and greater food insecurity among poor households worldwide (Naylor and Falcon 2010; Tadasse et al. 2014).

Disruptions of food supply chains

International and internal movement restrictions such as border, road and public transport closures and stay-at-home order or advisory have impeded and delayed food supplies at wholesale and retail stores around the world (Cappelli and Cini 2020; Torero 2020; Hobbs 2020). The supply gaps have been compounded by excessive demand for food items sparked by panic buying (Fig. 4) and restaurant closures (Power et al. 2020; Bhattacharjee and Jahanshah 2020). Additionally, labour shortages in agriculture and food processing and packaging facilities have been a major threat to food supply chain resilience. Peak season agricultural activities in many low-income countries rely heavily on migrant labour. As lockdown has hindered inter-district and cross-border labour movements, farm communities of Asia, Europe and North America have suffered a significant loss in production and revenue due to acute labour shortages during harvesting seasons (Trofimov and Craymer 2020; Pasricha 2020; FAO 2020). Labour shortages have also been an issue for large-scale food processors and suppliers. A growing number of workers are taken ill in food processing facilities where the operational model is not conducive to safe physical distancing. Consequently, a large number of food processing plants temporarily suspended production in Europe and North America (Hailu 2020; Hart et al. 2020; The Deutsche Welle 2020).

In any crisis, it is important to consider both supply and demand forces. Decreases in global food supply – whether caused by bad weather, lockdowns, export restrictions, transportation bottlenecks, climate change, or other emergencies – manifest themselves as income losses for most farmers and higher food prices for most consumers. Decreases in food demand, particularly those caused by recessions, tend to lower food prices and farmers’ income. Both negative supply shocks and negative demand shocks tend to hurt farmers – who are both net-sellers and net-buyers of food – but food price inflation may vary by location and food product. For example, FAOSTAT (2020) shows that overall global food prices are declining, while rice prices have increased 50% in Kiribati (Gunia 2020), corn futures are trading at their lowest level in four years, and evidence of food price inflation has started to emerge in both developed and developing countries (Akter 2020; WFP 2020a). If unchecked, these supply and demand forces are likely to favour food insecurity by reducing low-income households’ access to food (Barrett 2020).

Governments around the world have taken various actions to increase the resilience of their food supply chains. The most common strategy has been economic stimulus packages that aim to shield small-scale farmers against income shocks. Efforts have been intensified to increase the flow of food and other essential items by increasing the capacity of transportation networks. Multilateral agreements have been reached by countries such as Singapore, Australia and New Zealand to keep the flow of essential goods and services uninterrupted and eliminate trade barriers (The Straits Times 2020). The United States’ government has taken an extreme step to invoke its Defence Production Act to keep meat and poultry processing facilities open (Jacobs and Mulvany 2020).

Governments of both developed and developing countries have launched programs to procure agricultural products from farmers amidst the lockdown. The United States has announced its plan to purchase US$3 billion worth of dairy, meat, and produce from farmers starting from mid-May 2020 (Reuters 2020a). Likewise, the governments of India and Bangladesh are set to procure rice and wheat from farmers to support livelihoods as well as to maintain supply for their extended social safety net programs (Ministry of Food Bangladesh 2020; Department of Food and Public Distribution, India 2020).

Worker safety remains an integral component of resilient supply chains. Governments should take appropriate actions to minimize infection risks for workers as well as to keep food safe for the consumers following WHO and FAO guidelines (WHO and FAO 2020). Workers should be provided with personal protective equipment, should be prioritized for testing for covid-19 and should have access to good health insurance coverage or receive free treatment.

Disruption in the economic access to food

According to the latest World Food Program (WFP) estimate, the number of hungry people in the word has increased from 821 million in 2019 to 1.03 billion in May 2020 (WFP 2020a). The WFP Executive Director has warned global leaders against an unfolding “hunger pandemic” of “biblical proportions” that could result in 300,000 deaths per day (WFP 2020b). Modelling further suggests that hunger could rise further as a result of pandemic response policies (Sulser and Dunston 2020). Such dire predictions are based on the extent to which the share of the global population–a majority of whom live in low- and lower middle-income countries–are expected to lose livelihoods and consequently lose their access to food. The Covid-19 crisis situation dangerously resonates with Sen’s (1982) empirical analysis of four major famines of the twentieth century, namely, the Great Bengal Famine (1943), the Ethiopian Famine (I972–74), the Famine in the Sahel (1973) and the Famine in Bangladesh (1974). Sen concluded that mass food deprivations are rarely about a decline in food availability; rather they can be largely explained by loss of food entitlement, which is often caused by shortage of income and purchasing power of certain occupation groups.

According to the latest ILO estimate (as of April 29, 2020), 68% of the global workforce currently live in countries that either implemented or recommended workplace closures (ILO 2020a). Informal economy workers are the hardest-hit group among all occupational groups (ILO 2020a). In low- and lower middle-income countries, the informal economy workers suffered an 82% decline in income due to covid −19 lockdowns (ILO 2020a). The sectors that witnessed the largest decline in economic activities so far are accommodation and food services, manufacturing, wholesale and retail trade, and real estate and business activities (ILO 2020b). These four sectors collectively employ 37.5% of the global workforce (ILO 2020b).

A common national-level response to such widespread income shocks in low-income countries has been cash or food transfer or selling of subsidized food in the open market (Akter and Basher 2014; Headey 2013; Dorosh and Rashid 2013). However, the Covid −19 pandemic poses some unique challenges to the utilization of the traditional social safety net measures. Evidence reveals that food or cash transfer programs move at a slow pace, without a coordinated distribution plan or a national database of target groups causing the distribution outlets to attract large crowds, long queues, and a high potential for leakages (Yuda 2020; Reuters 2020b). Governments of many low-income countries are struggling to fund income support programs, given the uncertainty of the consequences of the pandemic and the growing need for infection surveillance and treatment, (Lanker et al. 2020). The fall in commodity prices on which many of these governments rely is a further aggravation.

The covid −19 induced food crisis has also led to a mass exodus of urban population to their rural roots in nations such as India and Bangladesh following the lockdown announcement, increasing food demand in rural areas (Denis et al. 2020; Randhawa 2020). Foreign remittance income and charitable giving have been hampered by the pandemic (Bamzai 2020). These have been economic lifelines for poor households during previous food crises (Generoso 2015; Jalan and Ravallion 2001; Mozumder et al. 2009; Regmi et al. 2016). While on the one hand, the pandemic has prompted many migrant workers, many of whom were infected, to return home (Moroz et al. 2020), the income shocks have decreased charitable giving in wealthier countries and households.

What we know of “food deserts” (Whelan et al. 2002; Beaulac et al. 2009, see Box 8: Expanding food deserts) suggests that crises tend to enlarge these areas, often urban or peri-urban, where no affordable healthy food is easily accessible. Food deserts are created by the joint dynamics of social, economic, and geographical processes, which might well be stimulated by the current crisis. Their expansion is also associated with degradation of diets, which we address below.

Box 8.

Expanding food deserts

| The concept of "food desert" (Whelan et al. 2002; Beaulac et al. 2009) refers to contexts where nutritious fresh foods, and even basic staples, are unavailable and unaffordable to poor or impoverished consumers who have only access to cheap, often highly-processed, non-nutritious, food. The concept has mostly been used in the context of the (urban) Global North, but can also apply to situations in the Global South (e.g., Li et al. 2019; Tuholske et al. 2020). Limited physical and economic access to food, including poor overall urban planning, deficient or non-existent public transport, urban decay, and generalised poverty have been cited as factors favouring the development of food deserts. Overall policies to improve purchasing power for food, combined with local policies (such as strategic planning for grocery stores establishment, based on population density, spatial poverty distribution, and access to transport), have been considered as effective ways to control and reduce food deserts (Koh et al. 2019). |

Disruption of diets

Diets depend on the food environment, which may be defined as the “collective, physical, economic, policy and sociocultural surroundings, opportunities and conditions that influence people’s food and beverage choices and nutritional status” (Swinburn et al. 2013, cited in Turner et al. 2018).

The various impacts reviewed above all play out ‘downstream’ as impacts on what people are able to eat, and therefore on hunger, diets, and ultimately on the nutrition and health of individuals, households, and nations. Having enough to eat is among the first thought of families and governments in this crisis. Beyond having enough food to survive, a focus on healthy diets – those containing the nutrients we need to thrive, not just to survive – becomes even more relevant during a global pandemic, as good nutrition is a driver of immunity and recovery which will be sorely needed as we fight off the disease within our own bodies (Sima et al. 2016). Unhealthy diets (overly based on staple foods or ultra-processed foods) were a leading cause of death and disease before covid −19, and underlie 11 million deaths per year (Afshin et al. 2019). A focus on diet quality (diets containing adequate nutrient-dense fresh foods, and devoid of toxins or toxicants) is therefore all the more relevant when making policies that affect food systems in times of epidemics.

Food system disruptions can cause major changes in the availability or accessibility of those foods (usually perishable) that are the most nutritious. This has been seen with covid-19 for meat in the USA (BBC 2020), vegetables in Ethiopia and India (Tamru et al. 2020; Harris et al. 2020, this issue), and dairy in India (Headey and Ruel 2020), for instance. Price changes tend to fall along similar lines: the price of staple foods is kept steady as much as possible by government policy; processed foods tend to be cheapest; and it is nutritious animal and plant foods that vary most in price, as seen in previous disruptions such as the drought and economic crisis in Indonesia (Block et al. 2004). Both supply and price issues shape the environments within which households buy their food, and households facing uncertain food access are known to shift away from nutritious perishable foods and towards staple foods and processed items with longer shelf-life but lower micronutrient value in times of crisis (Block et al. 2004; Béné et al. 2015). Healthy diets based on diverse plant foods were already too expensive for over 1.5 billion people in the world pre- covid −19 (Hirvonen et al. 2020), and disruptions that reduce availability or incomes, or increase prices, are known to reduce the quality of people’s diets before they reduce the quantity of calories consumed (Darnton-Hill and Cogill 2010).

The diets of the most marginalized in society are most affected in times of crisis. This has been seen in other major health shocks such as HIV/AIDS (Gillespie 2008; Gillespie et al. 2009), and in economic shocks such as the 2008 financial crisis (Hossain and Scott-Villiers 2017). In any given context, the poorest and most vulnerable segments of the population (including low-wage and casual food system workers) will have fewer resources to cope with loss of jobs and incomes. Any increase in the prices of healthy foods will lead to reduced ability to adapt their diets to the crisis and remain healthy. Outside of the immediate household context, many people rely on food transfer programmes such as school feeding, workplace meals, and public distribution programmes; with schools and workplaces closed down, many vulnerable populations will be missing these meals and the nutrition they provide. Beyond economic marginalisation, we know that broader equity considerations play out in the context of health shocks for diets and nutrition, for instance women tend to be differentially affected through their multiple roles as producers, entrepreneurs and carers (Harris 2014; Quisimbing et al. 2020). The consequences of food system disruptions for healthy diets should be assessed with an equity lens therefore, both in understanding the situation and determining solutions.

Food system policies to address disruptions and their political economy

Food policies can be classified into at least one of three classes: economy-wide policies, policies directed specifically at increasing food supply or improving the supply chain, and safety nets for households. The first class includes trade, price, tax, and monetary policies as well as acting on food stocks. Generally, these policies change food prices without changing in the short term the amount of food produced. The second group includes input subsidies, investments in agricultural research, land rights (titling and transfers), rural infrastructure and other needed public goods, dissemination of market information, government marketing boards, regulations in food processing or trade sectors. Safety net policies include minimum wage and welfare laws, in-kind food transfers, work projects, school feeding programs, social security or pension reform, and food vouchers. They focus on changing household access to food, with secondary effects on food prices.

Border closures are one of the most common responses to crises, with often very negative consequences at multiple scales (Abbott 2012). These consequences include, but are not limited to: inflation of national stocks and reduction of foreign exchange from food exports (at the national scale); reduced efficiency and reliability of supply chains and disrupting input supply chains (at the supply chain scale); and reduction of physical access to food, increase in food prices, and reduction of dietary diversity (at the consumer and household scale). The current covid-19 crisis involves all these missteps.

Some of the specific policies to deal with a crisis such as covid-19, which also impact food security, include quarantines, confusing directives on which workers are deemed “essential”, and the closure of restaurants, schools, and other institutions that provide meals for school children and vulnerable populations. These policies have sparked historically large recessions (Gopinath 2020), reduced government revenue from taxes and commodity sales (especially oil) at a time when additional spending may be most needed, and eroded trust in government and civic organizations (at the national scale); created additional bottlenecks throughout local and global food systems (at the supply chain scale); and lowered incomes and food access for domestic and foreign workers (at the household scale). Such policies disproportionately harm poor and more vulnerable households, who had limited access to food to begin with.

The foregoing sections have argued and provided evidence for a number of policy options. Governments should be distributing national food stocks rather than accumulating larger stocks during crises and removing export barriers (national scale). At the supply chain scale, governments should ensure that any policy designed to protect human health and well-being should not inadvertently harm it (indirectly) by creating new input or labour bottlenecks in the food system. The physical and social infrastructures on which the food system relies (from access roads and irrigation systems to cooperatives, agricultural extension work, land rights, and the credit system) must be preserved and viewed through an equity lens. Worker safety remains an integral component of resilient supply chains. Governments should take appropriate actions to minimize infection risks for workers as well to keep food safe for the consumers following the WHO and FAO guidelines (WHO and FAO 2020). Workers should have access to personal protective equipment, should be prioritized for infection testing, and should have access to good health insurance coverage or receive free treatment.

A human disease-associated disruption such as the current covid-19 pandemic brings about specific concerns. At the household scale, even though food and cash transfer programs have been reported to attract large crowds (risk of infection) and entail the risk that people could receive benefits they do not directly need, Sen et al. (2020) submit that the cost of not reaching needy people is much higher currently than the cost of giving out excess benefits. Policies to ensure adequate dietary diversity are especially important to ensure that individuals have stronger immunity to disease. Food systems policies should use a dietary lens, with a view to making healthy diets available, accessible, affordable, desirable and safe. Not only farmers and grocery workers, but seasonal labourers, processors, traders, and transportation and storage workers also need adequate protection from disease.

Among the difficulties in studying changes in food policy is the dynamic nature of the events being studied. Policy changes are both a cause and consequence of food price volatility and changes in food availability and access, mediated throughout by the actions of private citizens, civil servants, non-government organizations, international institutions, and other food system actors. The set of policies in place at any given time is a function of previous episodes of price volatility and of the political reactions to them. This creates serious endogeneity problems in identifying the impacts of different government policies. If, for example, governments with very high levels of covid-19 infection enact stricter border policies, a naïve correlation will make it look like stricter border policies increase infection rates.

The “naïve” model assumed implicitly by most policy analysis is that governments are trying to maximize some form of social welfare function – ensuring, for example, higher GDP/capita, greater levels of food security, or reduced poverty as their primary goal. Swinnen and van der Zee (1993) and Swinnen (1994) give important critiques of why policy advice based on this naïve model will fail to have the desired impact and why it is important to take the political economy of food policy seriously.

Social scientists have a wide range of political economy models to understand how governments make decisions. One model views government as relatively passive, responding to the needs of competing interest groups who try to adjust the levels of different policies to create and capture economic rents (Knudsen and Nash 1990; Karp and Perloff 2002). Interest groups may differ by insider/outsider status (Maloney et al. 1994), and food policy advocates will want to adopt different methods depending on their access to decision makers through interest groups. A more active, self-interested model envisions a government that uses policies to secure economic or political gains for itself (Grossman and Helpman 1994; De Gorter and Swinnen 2002). Such a government is unlikely to give food system resilience a high priority until its own political survival is at stake, such as during a food crisis. However, government decision making is seldom the result of a single individual with a unique, well-defined social welfare function. Fragmented government decision making creates multiple entry points for policy changes (Resnick et al. 2018), but also leads to conflicting policies, delays, policy reversals, and greater uncertainty. For example, when Vietnam’s Prime Minister announced the export ban on March 24, 2020, the Ministry of Industry and Trade – who oversee farmer welfare – began arguing the next day that production was sufficient to meet domestic demand and that the export ban should be lifted or reduced (Hai and Talbot 2015; Watson 2017; Tu et al. 2020).

A set of case studies on how a representative sample of governments responded to the global food price crisis of 2007–08 determined that “the responses to past crises are the best guides to predicting future [government] actions” (Watson 2017; Pinstrup-Andersen 2014; see also Pokrivcak et al. 2006). Even though the covid-19 crisis completely differs from the shock that the world was facing in the 2007–008 crisis, it is noteworthy that many of the same policies used then are being trotted out today. The same countries that imposed food export bans have reacted that way again (e.g., Vietnam, Russia). Countries that provide vouchers or in-kind food distribution over cash distributions did so again, while those that have favoured cash in the past continue to do so today.

Trying to change this political inertia is challenging. Pelletier et al. (2012) indicate that while it is relatively easy to generate political attention to nutrition matters, political and system commitment only form after significant, prolonged efforts by policy entrepreneurs who draw regular attention to nutrition issues. They further find that capacity constraints and lack of harmonization between administrative entities prevent mid-level administrators from making use of high-level political commitment to create new policies.

Then as now, decision makers face great uncertainty about exactly how widespread the disease will be, how much it will impact food production and distribution, and how food prices will change in the short and medium run. Even small changes in the assumptions of epidemiological models can lead to widely different forecasts. This problem is compounded by the fact that the parameters change in response to changes in human behaviour and government policy. This makes it difficult to prepare adequately: a prudent government that prepares for the worst would be liable to be criticized for its excess of caution even though that prudence prevented the worse; while a government downplaying the health situation would aggravate mortality by failing to take appropriate measures.

Perspectives

Looking at the global food system: Three angles among many

The global food system indeed is a “vast machine”. It has a massive influence on the everyday life of all humans, on the well-being of billions, and on the trajectory the earth system takes. The current disruption exposes again that the global food system currently is not working properly for all people or for the planet. It is the strongest driver of global environmental change -- it is the largest consumer of energy and natural resources, to the point that it is bringing the earth system away from a safe operating space (IPCC 2019; Willett et al. 2019); it is a principal driver of biodiversity loss, of land use change, of freshwater use, and it heavily interferes with the global nitrogen and phosphorus cycles (Steffen et al. 2015). Yet, the world is confronted with surging numbers of humans undernourished (about 1 billion) and of humans who are malnourished (about another 2 billions), out of a total of 7.8 billion today (Rockström et al. 2020).

This article has addressed some of the aspects of the food system that may be particularly vulnerable to the current covid-19 crisis. This crisis is an opportunity to investigate where and why the global food system is vulnerable, why it often functions wrongly, and how it could be improved so that it could address future crises to mitigate, or even prevent them. We have expanded our discussion to the overall vulnerability points of the global food system to future disruptions. To close this article, we wish to bring to the fore two additional angles of thought on which progress is, in our view, absolutely necessary to render food systems globally and locally resilient.

One first angle is the divide between considerations pertaining to quantitative food and qualitative diets. The former refers to the very large amount of grain, roots, and tubers that provide the caloric basis of diets worldwide, which mostly involves field crops. In many cases, this entails long distance transport (for the grain or the dried roots), leading to large-scale trade worldwide. The latter refers to extremely diverse agricultural products, including vegetables, fruits, eggs, milk and dairy, and meat – which must be free of toxins, toxicants, and contaminants. This second set of food elements concerns the provision of essential nutritional elements besides calories, involves production at very variable scales, often at the household scale, and implies trade of perishable goods that most commonly takes place over short distances. The two types of food sources have been related to differing policies (Pingali 2015), with a bias that has long favoured the quantitative, largely “grain-based” type, against the qualitative, perishable, nutrient-rich type. The report by the EAT–Lancet Commission (Willett et al. 2019) provides a broader view: Diets inextricably link human health and environmental sustainability. The two types of foods are necessary parts of diets which must be balanced for the sake of human and world health; the difference between “good” and “bad” food may be difficult for consumers to make; so that both policies and research need inclusiveness, and be driven not by consumers’ demand and markets only (Pingali 2015), but also by public health and environmental concerns (Willett et al. 2019).

A second angle concerns the links between food production and the environment. Many reviews and syntheses (see also Box 1: Environmental footprint of food production) have emphasized the magnitude of environmental impacts of food production (Campbell et al. 2017; Poore and Nemecek 2018). The two drivers of these impacts are: (1) the still increasing world population (Crist et al. 2017), especially in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Gerland et al. 2014), and (2) the global shift of diets towards more energy-expensive, especially sugar-rich and meat-rich, diets (Willett et al. 2019). Meat proteins, especially from beef meat, is extremely expensive environmentally: on average, globally (Poore and Nemecek 2018), 100 g of meat proteins costs the emission of 50 kg of CO2 equivalent: this is nearly ten times more environmentally-expensive than 100 g of poultry meat proteins, and fifty times more than 100 g of legume proteins.

A recent article by Cassman and Grassini (2020) provides fresh numbers and evidence on the environmental impacts of agricultural production. During the 1980–2002 period, most of the increase in global production of rice (87%), wheat (100%), maize (68%), and soybean (31%) were attributable to productivity gains (i.e., increase in yield per unit land); so that the global increase in production owed relatively little to the expansion of crop production area. During the 2002–2014 period, however, a much smaller fraction of the increase in global production of rice (57%), wheat 83%), maize (66%), and soybean (15%) resulted from productivity gains; therefore, a very large fraction of the increase of global food resulted from agricultural area expansion over non-cultivated land. The report by Cassman and Grassini (2020) therefore suggests that since 2002, the growing demand for food has increasingly been met through the destruction of the natural environment, not through increase of agricultural productivity resulting from scientific progress, as was the case in the two previous decades. Expanding agriculture has also been meeting part of the feed (soybean) and energy (maize) growing demands: it appears that since the beginning of the twenty-first century, the world’s population has literally been eating its natural environment, its forests, to secure its calories and its increasing demand for meat.

Disruptions and crises are a recurrent feature in the history of food systems. The covid-19 crisis is exposing a number of the vulnerability points of the global food system (Fig. 2). The present crisis impacts all the components of food security, and all the scales of the food system, from the household up to the global scale. So will, we believe, future crises. This is why addressing the current crisis should not overshadow the looming crisis associated with the Food-Population-Environment nexus, and instead should lead to research and policies to improve the all-connected world food systems for everyone.

A third angle pertains to the human capital in food systems. This has many aspects, but we wish to briefly give examples. Time and again, this article has mentioned labour in the food chain, especially long distance migrant labour. The covid-19 crisis is showing how weak this point is in the global food system: migrant labour is very sensitive to regulations and policies that may restrict movement, and migrant labourers are so vulnerable to disease. Migrant labour implies the exploitation of zero-qualifications, with zero-prospects of professional growth, paid with low wages under harsh working, social, and family conditions (Seddon et al. 2002). It commonly is employed in some select, high value, intensive productions, which are intended for international, not local, markets: some of the basmati rice in South Asia; some vegetables and fruits across Europe; some fruits and vegetable across North America, often shipped in refrigerated cargos. Economic logic commonly presents us with two interpretations: one is that remittances constitute an important way of economic growth in developing countries (e.g., McCarthy et al. 2006); another, that remittances are an effective instrument for sustained misery at home (e.g., Seddon et al. 2002; Berdegué and Fuentealba 2011).

Workers’ expertise in the global food system is not sufficiently recognised, not properly fostered, not adequately developed through formal education. India is concerned to replace its ageing farmers: the profession means hard work, tiny income, difficult quality of life, and limited prospects (Mahapatra 2019). Yet agriculture entails many skills and involves new technologies. The latter should be supported by independent extension services which ironically have declined over the years, in the global South (Anderson and Feder 2004; Savary et al. 2014) and the global North alike (e.g., Labarthe and Laurent 2013), and have been replaced in many countries by private interests, often linked with the agricultural input industry, with adverse effects on small farms (Labarthe and Laurent 2013).

Towards resilient food systems: Recommendations

The concept of resilience comes from material physics and has been formally and operationally defined in the environmental sciences (Fresco and Kroonenberg 1992) as the speed of restoration of an output trend after major disturbance of a system. Here, the system considered can be the global food system, or one of the many sectoral or local food systems; the output considered corresponds to any of the six components of food security discussed above and in Figs. 1 and 2. When applicable, these outputs are marked in brackets below: [1] to [6] (see Fig. 1), or with [S] when referring to food systems in their entirety.

As in Fig. 1, we consider three time ranges: short (0–3 months), medium (3–12 months), and long (beyond one year) term. There are conceptual reasons for considering different time scales (Fresco and Kroonenberg 1992): while the persistence of a system’s performances pertains to its sustainability, the capacity of a system to recover its properties and performances after disturbance depends on its resilience. There are also practical reasons: while the impacts of the current covid-19 crisis are still, as this article goes to press, surrounded with great uncertainty, the long-term consequences of not improving the performances of the global food system, as part of the Earth system, are paradoxically becoming clearer with accumulating scientific evidence.

Recommendations for short and medium term impacts (0–12 months)

[3]: Trade of staple food and agricultural inputs is vital in times of crisis, and must be uninterrupted and even facilitated. This can be achieved through international co-operation.

[1]: Access to quality seed, which matches farmers’ needs and practices as well as consumers’ requirements, must be ensured at all times, especially in times of crises.

[S]: Policies are required to ensure the availability of labour in food systems (farm, extension services, supply chain, distribution, sales). Health of these workers needs specific attention and resources.