Abstract

The G4C2 hexanucleotide repeat expansion (HRE) in C9orf72 is the commonest cause of familial amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). A number of different methods have been used to generate isogenic control lines using clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 and non-homologous end-joining by deleting the repeat region, with the risk of creating indels and genomic instability. In this study, we demonstrate complete correction of an induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) line derived from a C9orf72-HRE positive ALS/frontotemporal dementia patient using CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing and homology-directed repair (HDR), resulting in replacement of the excised region with a donor template carrying the wild-type repeat size to maintain the genetic architecture of the locus. The isogenic correction of the C9orf72 HRE restored normal gene expression and methylation at the C9orf72 locus, reduced intron retention in the edited lines and abolished pathological phenotypes associated with the C9orf72 HRE expansion in iPSC-derived motor neurons (iPSMNs). RNA sequencing of the mutant line identified 2220 differentially expressed genes compared with its isogenic control. Enrichment analysis demonstrated an over-representation of ALS relevant pathways, including calcium ion dependent exocytosis, synaptic transport and the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes ALS pathway, as well as new targets of potential relevance to ALS pathophysiology. Complete correction of the C9orf72 HRE in iPSMNs by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HDR provides an ideal model to study the earliest effects of the hexanucleotide expansion on cellular homeostasis and the key pathways implicated in ALS pathophysiology.

Introduction

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) is a rapidly progressive and uniformly fatal adult-onset neurodegenerative disorder characterized by loss of motor neurons (MNs) in the brain and spinal cord, with an average survival of ~2.5 years from symptom onset (1). The clinical, genetic and pathological overlap with frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is now well established (2). A hexanucleotide repeat expansion (HRE) mutation in the C9orf72 gene is responsible for 35–40% of cases of familial ALS (fALS), 5–7% of sporadic ALS (sALS) and ~25% of cases of familial FTD (fFTD) in populations of Northern European genetic heritage (3,4). The hexanucleotide expansion is located in a non-coding region of the gene, which forms either the upstream promoter or the first intron of C9orf72 transcripts. The number of (G4C2)n hexanucleotide repeats in affected individuals is typically more than 1000 (5,6).

Multiple mechanisms of C9orf72-HRE toxicity have been proposed. The accumulation of (G4C2)n transcripts in RNA foci in neuronal nuclei may lead to the sequestration of RNA binding proteins, with disruption of RNA handling or induction of nucleolar stress. Repeat-associated non-ATG (RAN) translation across the G4C2 repeat expansion in both sense and antisense directions produces aggregation-prone, potentially toxic, polydipeptide repeats (DPRs) (7,8). In addition, HRE result in transcriptional downregulation of C9orf72 mRNA and reduced protein levels in affected regions of the brain of ALS/FTD patients (9), suggesting that haploinsufficiency may also contribute to the phenotype.

RNA foci and RAN-translation products can be detected in induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived MNs (iPSMNs) derived from patients with C9orf72 hexanucleotide expansions, in association with varied phenotypes, including altered neuronal excitability, sequestration of RNA-binding proteins, increased endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress and defects in nucleocytoplasmic transport and autophagy (10–16).

A key challenge in using techniques such as RNA sequencing for the identification of disease mechanisms using iPSC neuronal models is that inherent biological variance arising from differences in genetic background, clonal selection and inconsistencies in reprogramming and differentiation protocols, may be greater than the expression changes due to a disease-causing mutation. Genome editing techniques, such as clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 and zinc-finger nuclease mediated-gene targeting, have been employed to remove point mutations in iPSCs from an ALS patients with SOD1 mutations and in iPSCs from an FTD patient with a progranulin mutation, to create isogenic control lines (17–20). Recently, the successful excision of C9orf72 (G4C2)n using CRISPR/Cas9 technology has also been reported, yielding isogenic lines with a missing repeat region (16).

Here, we report the generation of isogenic iPSC line from an ALS/FTD patient carrying an expansion of 1000 G4C2 repeats in C9orf72 using CRISPR/Cas9-mediated HDR to replace the pathogenic expansion with a donor template carrying a normal repeat size of (G4C2)2. To reduce the possibility of off-target mutations and improve on-target specificity, a double-nicking approach with the D10A mutant nickase version of Cas9 (Cas9n) was used (21). In MNs differentiated from the corrected iPSC lines, we demonstrate the correction of pathological markers of the C9orf72 HRE, such as sense and antisense RNA foci and dipeptide (DP) toxicity. We also demonstrate restoration of C9orf72 transcript expression and methylation to levels seen in normal controls. Using RNA sequencing, we identify dysregulation of ALS relevant pathways specific to lines carrying the expansion, including glutamate excitotoxicity and cell death and the functional validation of selected pathways in the corrected cell lines. This study therefore demonstrates that HDR-mediated correction in patient-derived iPSCs can lead to the generation of induced MN-like cells that display features characteristic of normal cells, and has the advantage over other techniques of generating a more precise isogenic control line free of indels.

Results

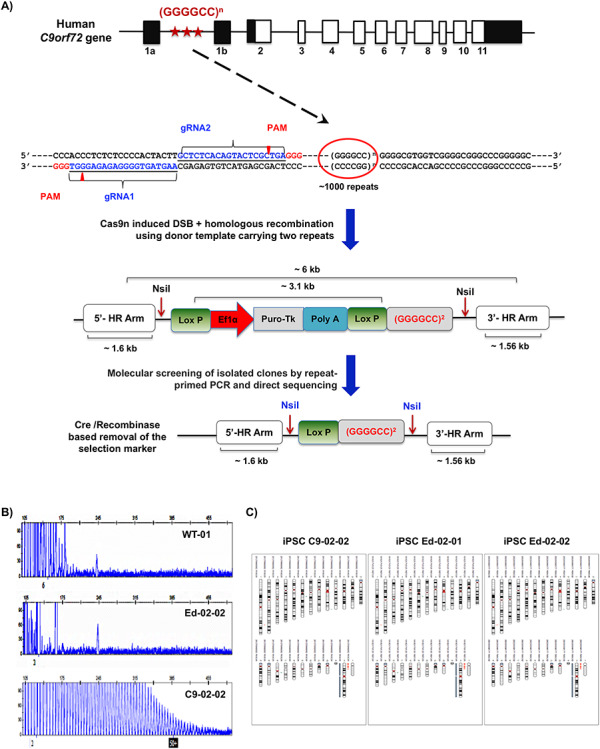

CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing of the C9orf72 G4C2 repeat expansion

Skin fibroblasts obtained from an ALS/FTD patient (C9-02) carrying an expansion of ~1000 G4C2 hexanucleotide repeats in C9orf72, estimated by Southern blotting, were used to generate two iPSC lines (C9-02-02 and C9-02-03) as previously described (10). All lines used in this study are summarized in Supplementary Material, Table S1. To correct the HRE mutation and generate isogenic lines, double-nicking CRISPR/Cas9 and HDR was applied to the C9-02-02 iPSC line using a double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) plasmid donor template harbouring two G4C2 repeats and containing two long homology arms flanking each side of the target site, to replace the large repeat expansion (~1000 repeats) via homologous recombination. A puromycin/TK selection-counterselection cassette was inserted ~53 bp upstream of the repeat region, driven by an EF1a promoter and flanked by two LoxP sites, to facilitate screening and isolation of the corrected clones (Fig. 1A). The cleavage efficiency of the two guide RNAs was evaluated using a T7E1 cleavage assay after transfecting HEK293T cells either with individual gRNAs or with both gRNAs at the same time. The cleavage assay allowed the detection of double-strand breaks (DSBs), indicated by the presence of heteroduplex DNA (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1A). This demonstrates that both gRNAs were able to introduce DSBs when applied simultaneously, ensuring that they could be used in the subsequent editing experiments in iPSCs.

Figure 1.

CRISPR gene targeting strategy for complete correction of the G4C2 repeat expansions in ALS/FTD patient iPSCs. (A) The overall scheme of the experiment is shown. The G4C2 hexanucleotide repeat region is indicated by stars. The subsequent diagram shows sequences of both guide RNAs, ~140 bp upstream of the repeat region, in blue. The homologous donor template design with LoxP-flanked Puro-TK selection cassette for the introduction of normal repeat size is shown in the next image. Cre/LoxP mediated excision was used to remove the selection cassette leaving one copy of LoxP integrated in the genome as demonstrated in the final diagram. (B) Electropherogram for a healthy control (WT-01), an edited iPSC clone (Ed-02), and the parental C9-02-02 iPSC clone. All puromycin resistant clones were assessed by RP-PCR to identify the presence or absence of the repeat expansion. Twenty-four clones showed normal electropherogram profile. (C) Karyograms produced using Karyostudio 1.3 from SNP array show no detected changes in the edited iPSC line Ed-02-01 versus the parent patient line C9-02. iPSC Ed-02-02 shows no additional detected changes, but note that the C7q amplification and C17q small amplified regions indicated in C9-02 and Ed-02-01 fall below the detection cut-off for Ed-02-02. Key (bands to left of indicated chromosome): red, loss or single copy; green, gain of copy; grey, loss of heterozygosity on autosomes, or two copies of X chromosome (i.e. this is a female line).

Following nucleofection of the C9-02-02 line, puromycin selection was performed and ~100 colonies were isolated and evaluated by repeat-primed PCR (RP-PCR) to confirm the elimination of the expanded hexanucleotide in 24 clones as indicated by the normal electropherogram profile (Fig. 1B). Sanger sequencing of the repeat region confirmed correct replacement by the donor template in two heterozygous (2% mono-allelic) and three homozygous clones (3% bi-alleic) (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1B). The specific integration of the donor template at the 5′ and 3′ junctions was also evaluated by direct sequencing and restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), confirming specific integration of the donor template (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1C). Bi-allelic clones were excluded due to the manipulation of both alleles with the donor template.

Cre/LoxP-mediated excision and negative selection with ganciclovir yielded multiple isogenic lines free of the selection marker, as confirmed by PCR using primers inside the cassette and outside the 5′ homology arm (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1D). After that, two sub clones, Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 were selected and the repeat region was amplified and sequenced, confirming the absence of the repeat and presence of the remaining LoxP site in the targeted alleles (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1E and F). The absence of the 6 kb expansion in the edited isogenic lines was further confirmed using Southern blotting analysis (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1G). These sequencing results confirmed the presence of the normal repeat size derived from HDR and demonstrating successful editing of HRE mutation by CRISPR/Cas9 system in iPSCs.

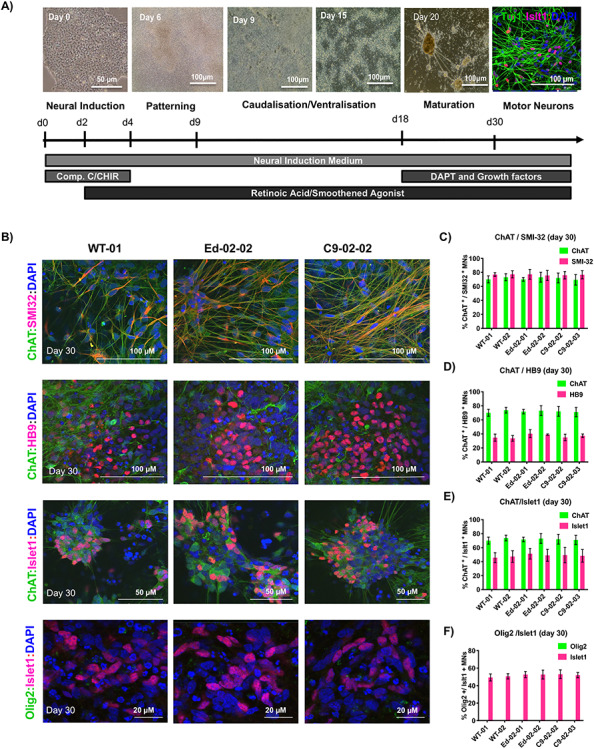

Immunostaining of pluripotency markers (NANOG, OCT4 and TRA-1-60) after gene editing showed that Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 iPSCs retain normal expression of these markers (Supplementary Material, Fig. S1H). Karyotyping of Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 also revealed that both lines retained their normal chromosomal profile when compared with the parental iPSCs (C9-02) (Fig. 1C). Immunostaining for MN specific differentiation markers Olig2 and Islet1 on Day 20, and Islet-1, HB9, SMI-32 and ChAT at Day 30 showed that the gene editing process had no effect on MN differentiation (Fig. 2A and B), with similar morphology and differentiation efficiencies seen in all differentiated lines (Fig. 2C–F).

Figure 2.

Characterization and MN differentiation of edited clones. (A) Schematic of the timeline of the MN differentiation protocol and morphology of the cells during the differentiation process. (B) Representative immunofluorescence images of the MN differentiation markers (Olig2, Isl1, ChAT, SMI32, HB9) derived from WT-01 (healthy control), the Ed-02-02 (edited clone) and the C9-02-02 (C9orf72 HRE positive clone). (C–F) Quantification of positive MN specific markers in iPSC-derived MN cultures from two healthy lines (WT-01 and WT-02), two edited lines (Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02) and two patient lines (C9-02-02 and C9-02-03). On Day 30, 60–70% of MNs population showed positive staining for ChAT, 75–80% of cells stained for SMI32 and 35–40% for HB9 with no differences between the analyzed samples (P > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Olig2 was completely absent on day 30 of differentiation, while Islet1 showed 35–40% nuclear staining. Bar graphs showing mean ± SD. Data from three independent differentiations, minimum of 100 cells per differentiation for each genotype.

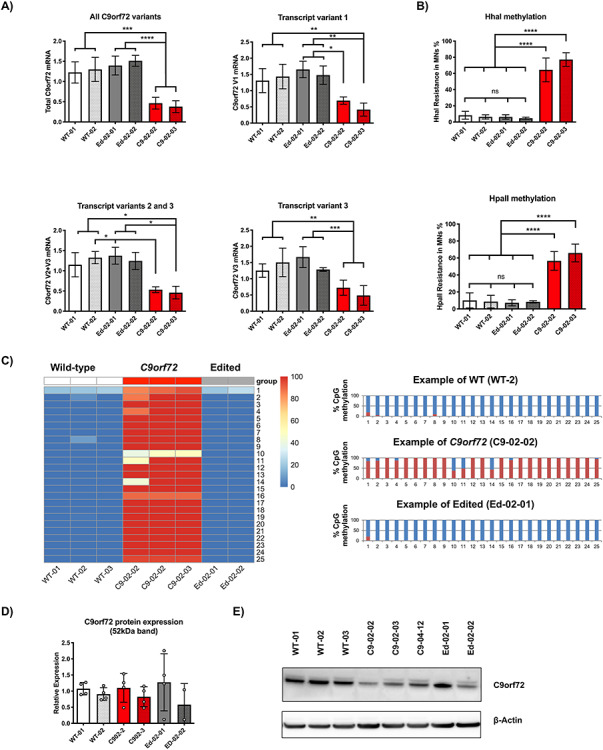

CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing restores normal C9orf72 expression and DNA promoter methylation levels

Since the HRE in C9orf72 has previously been shown to reduce the expression of C9orf72 in iPSMNs, we sought to establish whether normal regulation of expression had been restored by CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing. Quantitative RT-PCR with primers amplifying all C9orf72 RNA isoforms and the individual variants revealed that total C9orf72 RNA levels and the levels of the V1 and V2 mRNA variants were reduced in C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 compared with the normalized levels in Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02, which showed similar levels to WT-01 and WT-02 (P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA) (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Evaluation of C9orf72 promoter methylation and gene expression. (A) A reduction in Total, V1 and V2 C9orf72 RNA is seen in C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 clones compared with healthy controls and edited lines Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 (***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison’s test). The results suggest restoration of normal transcription at the C9orf72 locus following genome editing. Data showing mean ± SD from three independent differentiations (n = 3 for every cell line). (B) Following digestion with the methylation sensitive restriction enzymes Hha1 and HpaII, CpG island hypermethylation is demonstrated in the C9orf72 promoter region of patient lines C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 compared with both controls WT-01 and WT-02 and edited lines Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 (****P < 0.0001, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison’s test). Data showing mean ± SD from three independent differentiations (n = 3 for every cell line). (C) Bisulfite sequencing of all CpG islands in the 5′ region upstream of the C9orf72 HRE demonstrated hypermethylation in the C9orf72 positive lines. In the two edited lines studied, this was restored to normal. The right panel displays three example plots showing the ratios of methylated (red) to unmethylated (blue) cytosines at each CpG locus (n = 1 for all lines except for line C9-02-02, for which two samples were studied as shown). (D) C9orf72 protein expression unchanged in clones from patient C9-02 compared with both edited lines and lines from healthy controls (P > 0.05 Bonferroni’s multiple comparison’s test, n = 4 independent differentiations). (E) Example western blot of C9orf72 protein expression. Note: line C9-04-12 not included in this study.

Previous studies have also shown that C9orf72 gene expression may be reduced by repeat-associated methylation of the CpG promoter (22,23). To evaluate methylation levels upstream of the repeat, we performed a methylation sensitive restriction enzyme-quantitative real time PCRs (qPCR) which has previously been described (24,25). Restriction digestion of the CpG site by HhaI and HpaII occurs in the absence of CpG DNA methylation. Quantification of the digested DNA derived from both enzymes showed that CpG methylation was higher in C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 patient lines compared with WT-01 and WT-02 healthy controls and Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 lines for HhaI (P < 0.0001) and HpaII digestion (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3B).

In order to ascertain the methylation status of multiple CpG sites within the 5′ CpG island region of C9orf72, genomic DNA samples isolated from iPSMNs clones were treated with sodium bisulfite and subjected to PCR using primers specific to the 5′ CpG region. Direct Sanger sequencing of PCR products allowed relative quantification of C versus T nucleotides at each CpG site as a measure of methylation, since unmethylated C is converted to T by bisulfite, while methylated C (mC) remains unchanged. A total of 26 CpG sites could be assessed by this method, including one site (CpG 5) formed by an A>G single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) positioned 151 nucleotides upstream of the exon 1a start site (rs1373537, hg38 9:27574017T>C), which was present in all DNA samples analyzed in this study. Although the C allele of this SNP is not present in the reference sequence, it is in fact the predominant genotype in all populations studied, with the T allele having a minor allele frequency of only 0.01 as determined by the 1000 Genomes Project.

Using this method, all 26 CpG residues from iPSC MN clones derived from C9orf72 HRE-positive patients were found to be methylated (>50% mC). In contrast, the same CpG residues were found to be unmethylated (<30% mC) in control iPSMNs clones and in edited clones. Notably, the majority (86%) of CpG residues in the analyzed samples were either 100 or 0% methylated. CpG 1 was the site most likely to have a mixed methylation pattern, being mixed in every sample tested. Note that in this assay, CpG 2 corresponds to the site assayed by the methylation-sensitive restriction digestion assay (Fig. 3C).

Finally, we investigated whether C9orf72 mRNA expression levels affected C9orf72 protein expression. Western blotting using a published antibody against C9orf72 (26) demonstrated no difference in C9orf72 protein expression in patient lines compared with both control lines and edited lines (Fig. 3D).

Collectively, these results suggest that gene editing of the repeat expansion resulted in normalization of C9orf72 gene expression through restoration of normal methylation patterns, but no change in protein expression.

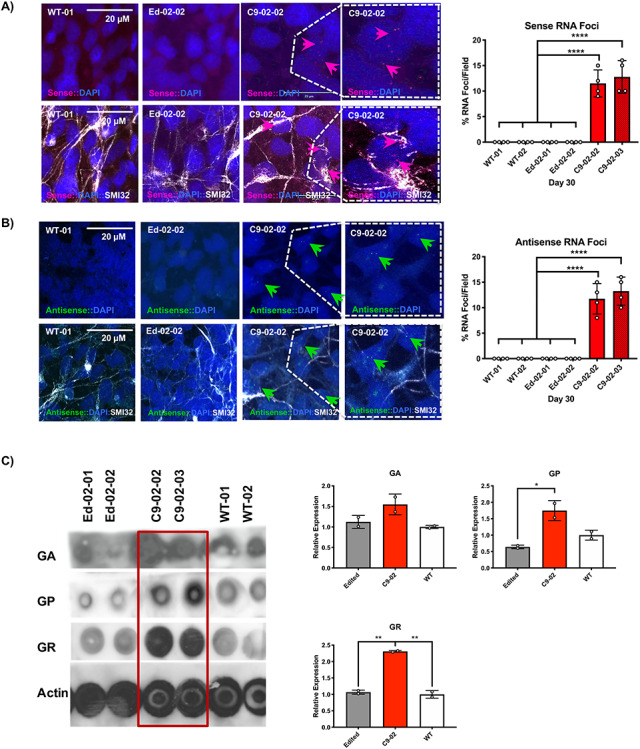

RNA foci and polydipeptides are abolished in CRISPR/Cas9 corrected iPSMNs

The presence of RNA foci and toxic polydipeptides are established neuropathological hallmarks of the C9orf72 HRE expansion and can be detected in iPSMNs derived from affected patients. We evaluated the presence of sense and antisense RNA foci in the iPSMNs using fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH). Both sense and antisense RNA foci were seen in MNs derived from C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 patient lines, but were absent from healthy controls WT-01 and WT-02 and edited clones Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 (Fig. 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Abolition of sense and antisense RNA foci and reduction of RAN translation products. (A and B) FISH with G2C4-Cy3 and G4C2-Alexa488 probes showing G2C4 sense (red) G4C2 antisense RNA foci (green) in C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 iPSC-derived MNs. Foci are absent in healthy and edited clones (****P < 0.0001, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison’s test). Nuclear foci are indicated by arrows and SMI32 was used as a MN-specific marker. Four fields of view containing a minimum of 100 neurons each were counted (n = 4). (C) Dot-blot of GA, GP, and GR DP repeats in C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 compared with both healthy controls and edited lines. Quantification showing differences between C9orf72 HRE lines and edited lines for GP and GR DP and between C9orf72 HRE lines and WT lines for GR (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison’s test, n = 2 lines per group, 1 differentiation).

To examine whether editing in MNs rescues the formation of RAN–DPs, we performed a dot-blot analysis of the GA, GP and GR polydipeptides using protein samples from all experimental lines. Higher concentrations of the DPs were detected in iPSMNs of C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 lines compared with healthy and edited lines (Fig. 4C). These results confirm that removal of the G4C2 HRE successfully corrects the typical pathology of nuclear RNA foci and DPs in iPSMNs.

CRISPR/Cas9 correction improves cell survival and the response to cellular stress

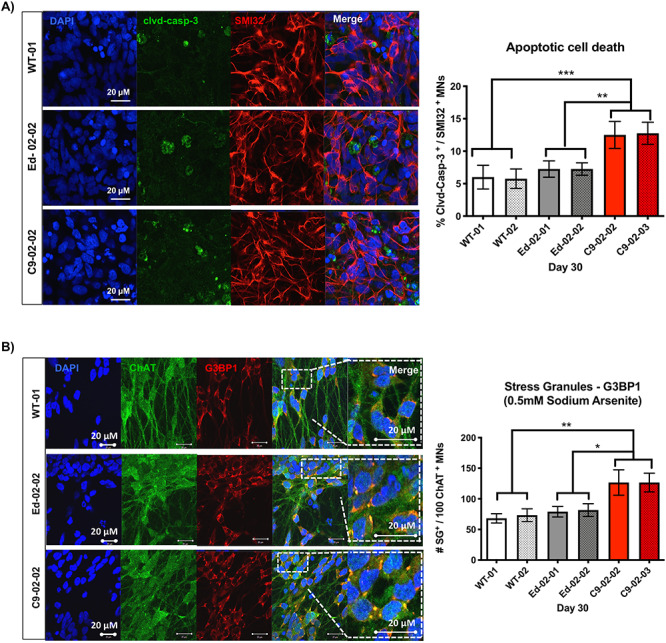

In previous work, we identified increased susceptibility of C9orf72 HRE positive iPSMNs to apoptosis in basal conditions (10). In this study, we confirmed increased levels of cleaved caspase3 in C9orf72 HRE positive iPSMNs using immunofluorescence imaging and demonstrate that edited iPSMNs, Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02, showed a decrease in cleaved caspase-3 staining compared with patient lines C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 (Fig. 5A, P < 0.001).

Figure 5.

Edited iPSMNs are less susceptible to apoptotic cell death and toxicity. (A) Representative images of cleaved caspase-3 activation in iPSMNs from lines WT-01, Ed-02-02 and C9-02-02 at basal conditions. Quantification of the proportion of cleaved caspase-3 positive MNs (mean ± SD from three independent differentiations (n = 3), minimum 100 cells per line and differentiation, Day 30) demonstrates a decrease in cleaved caspase-3 frequency in Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 cells compared with C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 iPSMN cultures (**P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison’s test). (B) G3BP1 accumulation in stress granules following 1 h 3 min of arsenite treatment was detected at higher frequency in C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 patient iPSC-MNs compared with healthy controls WT-01 and WT-02 as well as edited lines Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 clones (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Bonferroni’s multiple comparison’s test, mean ± SD from three independent differentiations (n = 3), minimum 100 ChAT positive cells per line and differentiation, day 30).

We have previously reported that the C9orf72 iPSMNs show a reproducible increase in markers of cellular stress, including a higher frequency of stress granules. iPSMNs were assessed for stress granule formation following sodium arsenite treatment for 1 h 30 min. Compared with C9-02-02 and C9-02-03 lines, the number of G3BP-positive stress granules in Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 iPSC-derived MNs was restored to levels similar to control lines (Fig. 5B, P < 0.01). In basal conditions, Poly-A binding protein (PABP) staining was similarly increased in C9orf72 iPSMNs but not in edited or control lines (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2).

RNA sequencing confirms C9orf72 haploinsufficiency and retention of the repeat-containing intron in C9orf72 HRE carriers

To enable an unbiased appraisal of the biological consequences of the hexanucleotide expansion and its editing, we performed RNA sequencing of iPSMN cultures at 30 days differentiation. We sequenced a total of seven edited samples (4 Ed-02-01 and 3 Ed-02-02), four samples with the hexanucleotide expansion (all C9-02-02) and one control patient sample. All differentiations were performed independently by a total of three operators. GC content was 43.4% (SD 0.7), 5′–3′ bias obtained from Picard tools was 0.36 (SD 0.07) and read depth was 56.6 million (SD 4.6 million), and these did not differ between groups (P > 0.05). Further quality control was performed by the addition of ‘sequin’ spike-ins that showed a good correlation between actual and predicted concentrations (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3A).

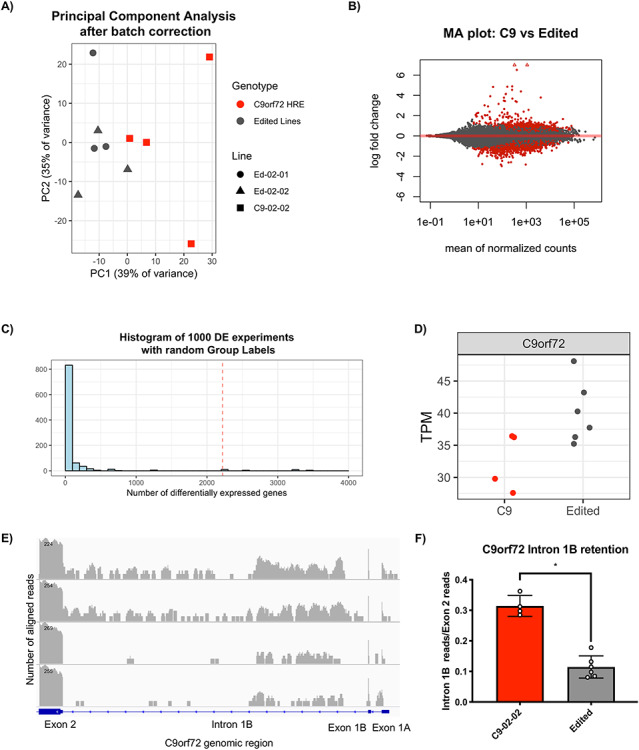

On exploratory data analysis, there was separation between C9-02-02 and edited controls in principal component 1, after correcting for the batch effect introduced by multiple individuals performing differentiations (Fig. 6A). MNs from this differentiation had a rostral identity, corresponding to cervical HOX gene expression and in line with other studies (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3B). Pluripotency markers were not expressed (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3C) and MN markers were expressed in all cell lines (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3D).

Figure 6.

Genome editing of C9orf72 results in significant differential expression and reduced retention of the repeat containing C9orf72 intron. (A) Principal component analysis using the 500 genes with the largest variance shows separation between the C9orf72 HRE positive parent line and both edited controls. (B) Differential expression analysis comparing the C9-02-02 clone with both edited clones reveals 1013 upregulated and 1203 downregulated genes as seen on this MA plot. Significantly differentially expressed genes are plotted in red, triangles represent datapoints outside the graphing area. (C) Histogram of permutation analysis using shuffled line labels demonstrates statistical significance of the sequencing analysis (P = 0.034). Histogram indicates frequency of having N differentially expressed genes upon permutation. Dashed red line indicates result without permutation. (D) TPM showing normalized expression for all C9orf72 transcripts combined (FDR = 0.002). (E) Representative images showing stacked reads aligned to the first three exons and corresponding introns of C9orf72 (log scale). Top two panes show two independent differentiations of line C9-02-02 and the lower two panes show reads from Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02. The gene diagram is annotated with the used nomenclature. (F) Quantification of intron retention of the repeat containing intron divided by the number of reads in the adjacent exon 2 shows reduced intron retention after genome editing (mean ± SD, P = 0.01, Mann–Whitney test).

On gene level differential expression analysis, 2220 genes were found differentially expressed at an FDR threshold of 0.05, of these 1017 were upregulated and 1203 were downregulated (Fig. 6B). Permutation analysis of differential expression was statistically significant (P = 0.027, Fig. 6C). Total C9orf72 expression was reduced by 22.5% in C9orf72 HRE MNs compared with the edited controls, confirming previous qPCR findings (FDR = 0.002, Fig. 6D). Finally, in line with other studies (27), we detected retention of the repeat containing intron in the C9orf72 HRE positive lines which was restored to lower levels in the edited lines (P = 0.01, Mann–Whitney test, Fig. 6E and F). On analysis of splicing changes throughout the genome using rMATS (version 4.0.1), no statistically significant differential alternative splicing events were found (P = 0.2).

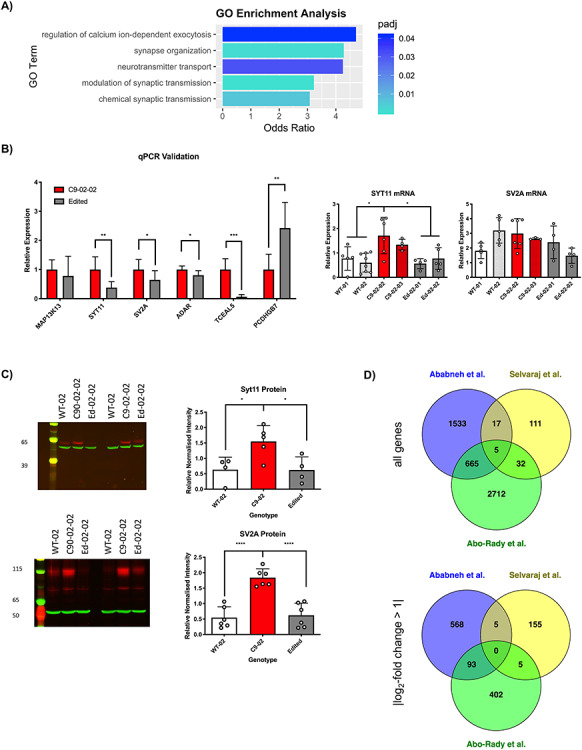

Enrichment of ALS-relevant pathways including synaptic function in C9orf72 HRE positive motor neurons

Overrepresentation analysis revealed striking differences in up- and down-regulated genes. Genes upregulated in C9orf72 HRE positive MNs were enriched for calcium-ion dependent exocytosis, synapse organization and neurotransmitter transport, whereas downregulated genes were enriched for cell division (Fig. 7A).

Figure 7.

Geneset and overrepresentation analyses of gene expression increased in C9orf72 HRE neurons compared with edited controls reveals pathways relevant to ALS. (A) GO overrepresentation analysis of genes upregulated in C9orf72 HRE iPSMNs compared with the edited controls (FDR < 0.05) reveals enrichment of pathways of calcium-ion dependent exocytosis and synaptic transmission. (B) A number of differentially expressed targets were selected for validation of RNA sequencing. Validation was performed on six C9-02-02 lines and seven edited lines (mean ± SD; Mann–Whitney test: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05). For genes of interest, more extensive validation was undertaken as follows: WT-1 5 differentiations, WT-2 eight differentiations, C9-02-03 four differentiations, C9-02-02 six differentiations, Ed-02-01 five differentiations and Ed-02-02 four differentiations. (mean ± SD; Bonferroni’s post-hoc test: *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001). (C) Six independent differentiations of patient lines (C9-02-02 and C9-02-03), edited lines (Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02) and a control line (WT-02) were performed for western blotting using synaptotagmin 11 and SV2A antibodies. The left panels show quantification across all six differentiations (mean ± SD). Synaptotagmin 11 has increased expression in C9-02 lines compared with edited lines (P = 0.04, Bonferroni’s post-hoc test) and healthy controls (P = 0.04, Bonferroni’s post-hoc test). SV2A is increased in C9-02 lines compared with edited lines (P < 0.001, Bonferroni’s post-hoc test) and healthy controls (P < 0.001, Bonferroni’s post-hoc test). The right panels show representative western blots for both proteins (actin green, antibody of interest red). (D) Comparison with published datasets. On comparison with published datasets, there was a statistically significant overlap between this dataset and the reanalysis of Abo-Rady et al. (P < 0.001, permutation analysis with replacement). No statistical overlap was found between either of these two datasets and the results list published by Selvaraj et al. (P > 0.05).

To corroborate these findings using a different method that does not depend on a P-value threshold, geneset enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the reactome database was performed. The top terms enriched in MNs from C9orf72 HRE carriers included Ras activation upon Ca2+ influx and neurotransmitter release (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4A). Interestingly, the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) Pathway for ALS was also enriched in C9orf72 HRE positive iPSMNs (adjusted P-value 0.03). The pathway contains genes involved in a number of ALS relevant pathogenic processes, such as glutamate toxicity, mitochondrial dysfunction, ubiquitin proteasome dysfunction as well as neurofilament damage (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4B). Leading edge analysis using all enriched reactome genesets (adjusted P < 0.05) was performed, to look for genes that are enriched in multiple pathways and therefore may be involved in pathway regulation (Supplementary Material, Fig. S4C). This analysis yielded a group of genes shared by four or more pathways, which included AMPA and NMDA glutamate receptor subunits, synaptic genes, neurofilament light chain and Ras nucleotide exchange factors. Of relevance to functional results indicating caspase3 activation, the KEGG ALS pathway analysis results included an enrichment of ALS-relevant apoptotic pathways including an upregulation of BAX (FDR = 0.04, log2-fold change 0.8).

Validation of the RNA sequencing study by qPCR was undertaken in an expanded sample cohort and confirmed the findings from the sequencing study (Fig. 7B). For further validation, we focused on the enrichment of transcripts encoding synaptic proteins in C9orf72 HRE positive MNs. The synaptic constituent synaptotagmin 11 was found to be consistently upregulated in C9orf72 HRE iPSMNs compared with both isogenic controls and healthy controls. Synaptotagmin 11 transcript levels in another C9orf72 HRE positive iPSMN line from the same patient were similarly elevated (Fig. 7B).

To study whether the increased levels of synaptotagmin 11 affect protein expression, we performed western blotting on total soluble protein obtained from six independent MN differentiations and were able to confirm increased levels of synaptotagmin 11 and SV2A in C9-02 iPSMN lines compared with both healthy controls and edited lines (Fig. 7C), demonstrating that gene editing has restored the expression of these proteins to their baseline levels.

We performed a comparison between this dataset and several publicly available RNA sequencing datasets comparing C9orf72 HRE positive lines with edited controls. We reanalyzed the recently published dataset from Abo-Rady et al. (28), finding a total of 3414 differentially expressed genes between the C9orf72 line and the edited line, of which 500 had an absolute log2-fold change greater than 1. The differences in differential expression counts between our analysis and the original report are likely attributable to a more conservative estimate of prior variance used here for consistency (betaPrior = TRUE option in DESeq2 (29)). We also compared these two results lists with the list of genes published in Selvaraj et al. (16), which is not a comprehensive dataset but instead contains the overlap between the differential expression of the C9orf72 HRE and independent controls as well as the differential expression of one C9orf72 HRE line and its edited control. We found that there was a significant overlap (greater than chance) between our data and the Abo-Rady et al. dataset (P < 0.001, permutation analysis without replacement), but not between either of these two datasets and the Selvaraj et al. gene list (P > 0.05). These results were consistent when analyzing all genes, and when only using genes meeting |log2-fold change > 1| (Fig. 7D). There was no significant overlap between any of the three datasets when analyzing up- and down-regulated genes separately, however. This demonstrates that edited lines corrected with different methods are not biologically equivalent.

Discussion

Modelling ALS using iPSMNs offers novel opportunities in studying human MNs in vitro and has substantially contributed to the understanding of C9orf72 HRE positive ALS (10,15,30). Key challenges in the interpretation of expression changes in iPSC-based models include genetic differences between individuals and also biological variance between cell lines from the same individual, which might mask true expression changes related to the disease mutation. This makes it challenging to relate changes in transcription to cellular phenotypes to individual mutations, and to the underlying pathophysiology of ALS. The complex genetic architecture of ALS, in which even apparently monogenic forms of the disease may have an oligogenic contribution, makes it even more challenging to isolate the specific impact of individual mutations on cellular phenotypes relevant to ALS (31,32). Genome editing, particularly using the CRISPR/Cas9 nuclease, provides a method to address these challenges directly by creating isogenic control lines, and has been successfully used to correct ALS-causing point mutations (17–19).

The CRISPR/Cas9 system is a very versatile and simple RNA-mediated system for genome editing in diverse cell types and organisms, with the major advantage of the capacity to target virtually any gene in a sequence-dependent manner (33). Targeting of Cas9 to a specific genomic site is mediated by a 20-nucleotide guide sequence within an associated single guide RNA (sgRNA), which directs the Cas9 to cleave complementary target DNA-sequences adjacent to short sequences known as protospacer-adjacent motifs (PAMs). Cas9 introduces a DSB 3-base pairs upstream of the PAM, which is repaired by either of two pathways, non-homologous end-joining (NHEJ) that leads either to insertion/deletion (indel) mutations of various lengths, or by homology-directed repair (HDR), which can be used to introduce specific mutations or sequences through recombination of the target locus with exogenously supplied DNA ‘donor’ templates (34).

Using this approach, Selvaraj et al. have reported the excision of the C9orf72 HRE and its flanking region in three iPSC lines from different patients demonstrating the correction of neuropathological features in iPSMNs, as also demonstrated in this study (16). Among several hundred transcriptional changes, they demonstrate increased GluA1 AMPA receptor expression in patient compared with edited lines. Editing resulted in a reduction of MN-specific vulnerability to excitoxicity. The three lines in the study were corrected using NHEJ, resulting in deletions of variable extent in the promoter region of the most abundant C9orf72 transcript. A second study using a similar approach in two cell lines, demonstrated upregulation of proapoptotic pathways including ATM and p53 that were corrected by excision of the repeat (35). A third, most recent study used a method relying on CRISPR-guided double-stranded breaks, and introduced a donor template with a zeocin cassette, which was retained for subsequent studies (28), demonstrating axonal trafficking defects in the patient line compared with the edited control.

Our study uniquely uses homology-directed repair to reintroduce a donor template from the other allele, thereby avoiding the deletion of promoter RNA, and leaving behind two short LoxP insertions. We demonstrate that this method results in restoration of normal C9orf72 expression and correction of repeat-associated hypermethylation of CpG islands, as well as in reduced intron retention. We did not demonstrate restoration of protein levels but cannot exclude the possibility of smaller fluctuations in C9orf72 protein abundance. Similar to Selvaraj et al. (16), we also observe an increase in Ca2+ permeable subunits of AMPA receptors in patient cells, suggesting increased glutamate toxicity.

In line with previous results (10,35), this study also demonstrates increased caspase-3 cleavage in C9orf72 HRE positive iPSMNs, which is restored to normal levels after genetic correction. Cleaved caspase-3 is an indicator of ER stress and apoptosis, and has been associated with gain of toxic function in poly-GA overexpressing mouse cortical neurons (36). The pro-apoptotic milieu associated with the C9orf72 HRE is further corroborated by RNA sequencing results, which show increased BAX expression in patient iPSMNs and is in line with our previous findings of reduced Bcl-2 and increased levels of BIM and Bcl-XL (10).

The bioinformatic comparison between our dataset and Selvaraj et al. and Abo-Rady et al. provides insight into discordant results between these studies, which all carried out CRISPR-correction of the C9orf72 HRE in iPSCs. The modest overlap between our study and Abo-Rady et al. is interesting, but does not persist when analyzing up- and down-regulated genes separately, explained by the fact that many genes that are downregulated in C9orf72 patients in our study are upregulated in Abo-Rady et al. While our study finds a relative balance between up- and down-regulated genes, in the Abo-Rady et al. dataset more genes are downregulated in the edited line compared with the C9orf72 HRE positive line, indicating more fundamental changes in the gene expression profile and underlying biology. Using existing data, we cannot estimate which variables are responsible for the divergent results between all three studies, and differences in age, gender and heritage of the patients as well as differences in reprogramming and differentiation techniques may all play a role. Likewise, there may be an effect of the editing strategy. We have attempted to minimize the interference of the correction by careful CRISPR site design, the use of two edited clones in our study to mitigate the chance of correction-specific off-target effects, and by the use of homology-directed repair with replacement of a donor template.

In summary, this study provides further evidence for specific pathways underlying the pathogenicity of the C9orf72 HRE expansion by restoring normal cellular phenotypes following focused correction of the expansion using homology-directed repair of the C9orf72 HRE. The successful correction of both gain and loss of function mechanisms demonstrates correction of the consequences of the HRE, which has therapeutic application in the longer term; however, the low efficiency of HDR in mature neurons would first need to be overcome. RNA sequencing further confirms the correction of pathways relevant to ALS and offers new potential targets for investigation such as upregulation of synaptic proteins seen in this study.

Materials and Methods

Fibroblast reprogramming

Skin fibroblasts obtained from an ALS/FTD patient (C9-02) carrying the (G4C2)n repeat expansion mutation in the C9orf72 gene, confirmed by repeat primed PCR and Southern blotting, were used to generate two iPSC lines (C9-02-02 and C9-02-03) using the CytoTune-1-iPSC reprogramming kit (Life Technologies), as previously described (10). Ethical approval for the collection and use of these cells was obtained from the South Wales Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 12/WA/0186).

Karyotyping

Genomic DNA was extracted using the DNeasy kit (QIAGEN). Genome integrity for iPSC lines and their corresponding fibroblasts was assessed using the Human OmniExpress24 array (~700 000 markers, Illumina) and analyzed using KaryoStudio software (Illumina).

CRISPR/Cas9 gRNA construct preparation and guide RNA construction

Guide-RNAs (gRNA1 and gRNA2) were designed to target a sequence 140 bps upstream of the repeat region. All PCR reactions were done using Phusion High Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in a 50 μl total volume. Sanger sequencing was performed by Source BioScience (Oxford, UK). Oligo sequences for gRNA synthesis are listed in Supplementary Material, Table S3. gRNA synthesis was performed using the pX335 vector (Addgene, Plasmid #42335) containing a D10A nickase for the co-expression of SpCas9 and gRNA, following a published protocol (34). For the construction of gRNA 1 and 2, the pX335 vector was linearized with BbsI and gel-purified. The two oligos for each gRNA were annealed, phosphorylated, and ligated into the pX335 vector. The vector was then transformed into Stabl2 Escherichia coli and DNA minipreps were prepared and sequenced to check for the presence of correct gRNA sequences. Finally, two midipreps were prepared for successfully constructed gRNA 1 and 2.

Design of homology-directed repair template

The DNA regions upstream and downstream of the repeat were assessed individually for the presence of any SNPs using two sets of specific primers listed in Supplementary Material, Table S4. The left and right homology arms were amplified from the wild-type allele of the same patient DNA (C9-02), which contains two G4C2 repeats. The amplification was performed using two units of Phusion polymerase with 10× buffer (NEB), 10 μm forward primer, 10 μm reverse primer, 10 mm dNTP mix and 5 ng DNA (HR-F and HR-R primers in Supplementary Material, Table S4). The mixture was heated to 98°C for 2 min, then 35 cycles of 98°C for 15 s, 67°C for 20 s and 72°C for 3 min and followed by 5 min of final extension at the same temperature. The purified PCR product was inserted into the pGEMT easy vector (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Two Nsi1 sites upstream and downstream of the repeat region were inserted using site-directed mutagenesis (SDM) to allow the evaluation of successfully targeted clones by polymerase chain reaction–RFLP (PCR–RFLP), using the same PCR reaction conditions listed above (SDM-F and SDM-R primers in Supplementary Material, Table S4). After that, 1 μl of DpnI restriction enzyme was directly added to the PCR product and incubated for 30 min at 37°C to remove the original plasmid. A LoxP-flanked EF1α-Puro-Tk cassette in a pENTR plasmid (Invitrogen) was inserted between the two homology arms ~100 bp upstream of the repeat region and in between the two Nsi1 sites. The cassette was amplified by PCR then ligated to the donor template using Gibson Assembly Master Mix (NEB, primers in Supplementary Material, Table S4). The reaction was incubated at 50°C for 15 min, followed by bacterial transformation and miniprep preparation. The resulting construct was checked by direct sequencing and midiprep was prepared.

Cell culture and transfection of HEK293T cells for cleavage activity testing

Genomic DNA samples from untransfected and transfected cells were extracted using DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen). The genomic region flanking the CRISPR cleavage site was amplified by PCR using specific Surv-F and Surv-R primers to amplify 900 bp surrounding the genomic cleavage site (Supplementary Material, Table S4) and the resulting products were purified using PCR Cleanup kit (Qiagen). Cleavage assays were performed using 400 ng of PCR products that were denatured by heating at 95°C then reannealed to form heteroduplex DNA using a thermocycler. Then, the reannealed PCR products were digested with T7 endonuclease 1 (T7E1, New England Biolabs). Digestion was performed using 10 unites of T7E1 enzyme and incubated for 15 min at 37°C. The T7EI reaction was stopped by adding 2 μl of 0.25 M EDTA solution. The digested products were analyzed on 3% agarose gel electrophoresis stained with ethidium bromide to check for heteroduplex DNA formation.

CRISPR-mediated genome targeting of iPSCs

On Day 0, iPSCs were pre-treated with 2 μm of Rho Kinase (ROCK) inhibitor for at least 1 h prior to nucleofection. Cells were dissociated into single cells by incubating them with TrypLE for 5 min at 37°C, mixing with PBS and followed by centrifugation at 400 g for 5 min. Two million cells were transfected with 2.5 μg of each gRNA-encoding plasmid and 4 μg of donor plasmid using the Neon Transfection system (Life Technologies). A GFP puromycin-free plasmid was used as a positive control. Following electroporation, cells were plated on 10-cm dishes coated with drug-resistant (DR4) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in human embryonic stem (hES) cell media composed of knock-out Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) (Gibco), 10% knock-out-serum replacement (Gibco), 2 mm glutamax-I (Gibco) 100 U/ml, penicillin/streptomycin (P/S) (Gibco), 1% non-essential amino acids (NEAA) (Gibco), 0.5 mm 2-mercaptoethanol (Gibco) and 10 ng/ml basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) (R&D) and also supplemented with 10 mm ROCK inhibitor Y-27632 (RI) for overnight. On Day 3, puromycin was added at 0.35 μg/ml to initiate the selection process. Surviving individual colonies were picked and expanded in 24-well plates coated with DR4 MEFs. Confluent wells were further split for expansion and molecular screening.

Repeat-primed PCR

iPSC clones were grown and passaged on two 24-well plates for DNA extraction and freezing in LN for storage. Total DNA was extracted using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (QIAGEN) and resuspended in Nuclease free water. The clones were screened first by RP-PCR. Primer sequences used in RP-PCR are listed in Supplementary Material, Table S4. Two RP-PCRs were performed, RP-PCR1 to assess the presence of the repeats on the 5′ direction, and RP-PCR2 to assess the presence of the repeats on the 3′ direction. RP-PCR assays were performed as previously described with a brief modification on the primer sequences (9,37). Both PCR mixes were prepared individually in a reaction volume of 15 μl, containing 100 ng of genomic DNA, 8 μl Extensor mastermix (Thermo Scientific), 6 μl of 5 M betaine, 20 μm of both forward and repeat specific primer and 2 μm of reverse primer. The reactions were subjected to touchdown PCR programme consisting of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s and 72°C for 30 s, then 1 μl of each PCR product was mixed with 8 μl of formamide, and 0.5 μl GeneScan size standard (Applied Biosystems).

PCR and direct sequencing of the repeat region

Following RP-PCR, 24 clones without the repeat expansion were screened by PCR amplification of the repeat region in a 50 μl reaction volume using Repeats-F and Repeats-R in Supplementary Material, Table S4. PCR was performed as follows: 2 min at 98°C, 35 cycles of 15 s at 98°C, 30 s at 67°C 2 min at 72°C and one final step for 5 min at 72°C. The PCR product was purified using QIAquick PCR Purification kit (QIAGEN). Sequencing analysis was performed using the Repeats-R primer (Source Bioscience).

In-out PCR and direct sequencing of intended modification

Clones without repeat expansion were screened by PCR amplification inside the EF1α-Puro-TK cassette and outside either 5′ or 3′ homology arms (5′-in-out, 3′-in-out PCRs). Sequences and specifications of the primers are shown in Supplementary Material, Table S4. PCR cycling conditions were performed as follows: 2 min at 98°C, 35 cycles of 15 s at 98°C, 30 s at 67°C and 2 min at 72°C and one final step for 5 min at 72°C. About 35 microliters of PCR products were purified using QIAquick PCR Purification kit (QIAGEN) and sequenced to confirm site-specific integration and successful insertion of Nsi1 (primers in Supplementary Material, Table S4). Ten microliters of PCR products were digested with Nsi1 (3 h with five units of Nsi1 enzyme (NEB)) and then, PCR fragments were visualized on 2% agarose gel electrophoresis to confirm the insertion of Nsi1 sites.

Removal of Puro/Tk cassette using Cre-Lox P system

To excise the selection cassette, iPSCs from one of the heterozygous targeted clones (Ed-02) and one homozygous clone (Ed-03) were nucleofected using Cre mRNA following the same nucleofection experiment as described above. iPSCs were nucleofected with 0.5 μg Cre mRNA and seeded on 10-cm plates pre-coated with MEFs and maintained in hES supplemented with 10 μm Y-26732 and no antibiotics. After few days of nucleofection, cells were treated with 3 μg/ml Ganciclovir added directly to the feeding media. After 7–10 days, some of the growing colonies were picked up and transferred into 96-well plate coated with MEFs then split into two new plates, one used for freezing and one for genotyping and PCR analysis of Puro/Tk cassette-free clones. Multiple-edited isogenic lines were generated from Ed-02 heterozygous clone after excision of the selection marker. Ed-03 derived clones were used as controls for Cre excision efficiency. Two edited clones were used after excision of the cassette Ed-02-01 and Ed-02-02 for phenotyping experiments. DNA was extracted from iPSCs of the Cre-treated and untreated edited clones and from the parental cells (C9-02-02). After that, PCR amplification was performed using 5′-out-F and Puro-R primers to amplify inside the Puro/Tk cassette and outside the 5′-homology arm. Another PCR was carried out using Exc-F and Exc-R primers to amplify the repeat region, generating a fragment of 75 and 109 bp for the wild-type and the targeted allele, respectively. The difference in size is related to the presence of a LoxP site after excision of the cassette using Cre-LoxP system. All primers sequences are in Supplementary Material, Table S4.

Southern blot

Southern blotting was applied on genomic DNA derived from edited cells, healthy controls and diseased cells. Briefly, DNA was extracted with DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit and 5–10 μg of genomic DNA was digested overnight at 37°C with AluI- and DdeI. Then digested samples were separated by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gel, and then transferred overnight to a positively charged nylon membrane by capillary blotting (Roche Applied Science). In the next day, membrane was cross-linked by UV irradiation, and hybridized overnight at 55°C with 1 ng/ml digoxigenin-labelled (GGGGCC)5 oligonucleotide probe (Integrated DNA Technologies) in 25 ml hybridization reaction (EasyHyb Granules, Roche). Following denaturation of the probe at 95°C for 5 min, probe was snap cooled on ice for 30 s and immediately added to the prehybridized membrane. The following day, the membrane was washed twice with stringency washes (2× saline-sodium citrate buffer (SSC) and 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), each for 15 min at 65°C in the hybridization oven. The membrane was then washed twice at the same temperature and conditions with 1× SSC and 0.1% SDS and finally washed twice with 0.5× SSC and 0.1% SDS for further 15 min at room temperature. The membrane was washed with 1× wash buffer (Roche Applied Science) for 2 min, then incubated with blocking solution (Roche Applied Science) for 1–2 h. After that, the membrane was incubated with Anti-DIG-AP Fab fragments (Roche) for 25–30 min and washed three times with 1× washing buffer. Ready-to-use CDPD (Roche Applied Science) chemiluminescent substrate was added to the membrane and signals were visualized on detection film. All samples were compared with DIG-labelled DNA molecular-weight markers II (Roche Applied Science) and repeat number was estimated compared with the DNA marker sizes.

Differentiation of iPSCs to motor neurons

iPSCs were differentiated to mature MNs (iPSMNs) using a previously described protocol (10), which was adapted with minor modification from the protocol described by Maury et al. (38). Briefly, the iPSCs were grown on Matrigel until confluency, then neural induction was started using DMEM/F12:Neurobasal 1:1, N2, B27, ascorbic acid (0.5 mm), 2-mercaptoethanol, compound C (3 μm) and Chir99021 (3 μm). After 4 days in culture, RA (1 μm) and SAG (500 nm) were added to the medium. On the next day, Chir99021 and compound C were removed from the medium, and the cells were cultured for another 4–5 days. After that, cells were split 1:3 on approximately Day 10. Subsequently, the medium was supplemented with growth factors BDNF (10 ng/ml), GDNF (10 ng/ml), N-[N-(3,5-difluorophenacetyl)-L-ala-nyl]-S-phenylglycine t-butyl ester (DAPT) (10 mm) and laminin (0.5 mg/ml). After 7 days, DAPT and laminin were removed from the medium, and the neurons were allowed to mature until Days 25–30.

Immunofluorescence of motor neuron cultures

Cells on coverslips were washed once with PBS, then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS and blocked in blocking buffer (0.01% TritonX-100/TBS with 10% normal goat serum) for 1 h. Cells were subsequently incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies: goat anti-ChAT, mouse anti-SMI-32, rabbit anti-Islet1/2 and rabbit anti-HB9, and goat anti-Olig2 (Supplementary Material, Table S2), followed by three washes in 0.1% Triton X-100/PBS and 1 h of incubation with the secondary antibodies Alexa Fluor 488 and Alexa Fluor 568 (1:500, Life Technologies). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. The structures of MNs were visualized using a Zeiss LSM Confocal Microscope. The percent of positive cells were quantified using ImageJ software and normalized to number of positive staining for Olig2+ or SMI-32+ or ChAT+ on each image.

Quantitative RT-PCR

RNA was extracted from iPSMNs using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN). cDNA was synthesized using the iScript cDNA Synthesis kit (Bio-Rad) with oligodT primers. qPCRs were performed on 2 μl cDNA using SYBR Fast mastermix (Applied Biosystems) and specific primers for overall C9orf72 mRNA levels, V1 transcript, V2 + V3 transcripts and V3 transcripts, in a total volume of 25 μl per each reaction (Supplementary Material, Table S4). Master mixes and cDNA samples were loaded in a 96-well plate and samples were run on Applied Biosystems StepOne machine and analyzed using relative quantitation methods. All samples were amplified in triplicates from at least three different differentiation experiments. All gene expression analysis was performed using ΔΔCt method with normalization to GAPDH reference gene. Melting curve analysis was used to verify the specificity of the primers. PCR cycling conditions: 95°C 20 s initial denaturation, followed by 40 cycles of [95°C 3 s, 60°C 30 s].

Promoter methylation assay

For quantitative assessment of methylation levels, quantitative PCR with methylation-sensitive restriction enzymes was applied to measure the C9orf72 promoter methylation following published methods (24,25). Briefly, 100 ng of genomic DNA was digested with 10 units of HhaI (NEB) and 2 units of HaeIII (NEB) or 10 units of HpaII (NEB) and 2 units of HaeIII (NEB), to assess the methylation status of two CpG sites in the promoter region. DNA samples digested with only 2 units of HaeIII were used as a mock reaction. The digestion mixture was incubated overnight at 37°C followed by heat inactivation at 80°C for 20 min. qPCR was carried out using 30 ng of digested DNA per reaction and 2× FastStart SYBR Green Master mix (Applied Biosystems) using primers amplifying the differentially methylated C9orf72 promoter region (Supplementary Material, Table S4). The difference in the number of cycles to threshold amplification between double (HaeIII and HhaI) versus single digested DNA (HaeIII) was used as measure of CpG methylation. Both HhaI and HpaII restriction enzymes cut sites are within the unmethylated C9orf72 promoter and the amplification of the unmethylated digested products after enzyme digestion represents the methylation level.

Bisulfite sequencing

Direct bisulfite sequencing was achieved using an assay adapted from one described by Xi et al. (39). 400 ng of genomic DNA was bisulfite-converted using the EpiTect bisulfite-converted using the EpiTect bisulfite kit (QIAGEN). PCR was performed on bisulfite-treated DNA using the following primers (as used by Liu et al.) (24) to amplify the 5′ CpG island of C9orf72: forward 5′-GGAGTTGTTTTTTATTAGGGTTTGTAGT-3′, reverse 5′-TAAACCCACACCTACTCTTACTAAA-3′. GoTaq Hot Start polymerase (Promega) was used under the following thermal cycling conditions: 95°C for 5 min, followed by 10 cycles of touchdown PCR with 30 s denaturation at 95°C, 30 s annealing reducing the annealing temperature from 70 to 60°C by −1°C per cycle and with 1 min extension at 72°C, followed by 30 cycles with the annealing temperature at 60°C and with a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. PCR products of 466 bp were purified by agarose gel extraction and commercially Sanger sequenced by Source BioScience using the forward primer. Resulting chromatograms were analyzed using Chromas v2.6 software and the percentage of methylcytosine (mC) determined for each CpG using relative peak heights, whereby %mC = C/(C + T). In all samples, more than 95% of unmethylated C nucleotides were converted to T.

RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization

RNA FISH was performed using modified methods previously published (40). Cells grown on 12 mm RNase-free coverslips in 24 well plates were fixed using 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min, washed in PBS and permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. Cells were then dehydrated in a graded series of alcohols, air dried and rehydrated in PBS, briefly washed in 2× SSC and incubated for 30 min in pre-hybridization solution containing 2× SSC and 50% formamide. Hybridization was carried out for 2 h in 250 μl of pre-heated hybridization solution (50% formamide, 2× SSC, 0.16% BSA, 0.8 mg/ml salmon sperm, 0.8 mg/ml tRNA, 8% dextran sulfate, 1.6 mm vanadyl ribonucleoside, 5 mm EDTA, 0.2 ug/ml probe) at 80°C. Coverslips were firstly washed three times for 30 min each at 80°C in 1 ml high-stringency wash solution (50% formamide/0.5× SCC), and then washed three times for 10 min each at room temperature in 1 ml of 0.5× SCC. This was followed by a brief wash in PBS and immunofluorescence staining with SMI-32 (1:1000, DSHB) was performed to assess the presence of foci in SMI-32+ cells as described above. Optional treatments using RNase A (0.1 mg/ml; Life Technologies: 12091-021) or DNase (150 U/ml, Quiagen: 79254) were performed at 37°C for 1 h following permeabilization. After treatment the cells were dehydrated and air dried and the hybridization protocol was resumed as described above. 2′O-methyl RNA sense probes were conjugated with Cy3, whereas antisense probes were conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (Integrated DNA Technologies). Probe sequences were (C4G2)4, (G4C2)4 or (CAGG)6.

RNA sequencing

RNA was extracted from whole iPSMN cultures at day 30. Sequin spike-ins were added to the RNA prior to submission to the sequencing centre, with Mix A added to CRISPR samples and Mix B to C9orf72 HRE positive iPSMNs. Library preparation was carried out using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Sample Prep Kit v2 by the Oxford Centre for Human Genomics. RNA sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq4000 platform over 75 cycles. Sequences were paired-end. Fastq files were generated from the sequencing platform using the manufacturer’s proprietary software. RNA sequencing data from this study have been deposited with NCBI GEO with the accession code: GSE139144.

Mapping and quality control

Reads were mapped to the custom genome using STAR (2.4.2a, (41)) using the two-pass method. Maximum intron size was specified as 2 000 000. During the first run, STAR was run with an index and junctions generated using the custom genome annotation, as well as the following options: —outFilterType BySJout —outFilterMismatchNmax 999 —outFilterMismatchNoverLmax 0.04 —outFilterIntronMotifs RemoveNoncanonicalUnannotated. The junction file generated in the first run was used in the second run, without additional options. The mapping files from different sequencing lanes were merged at this stage. Quality control was performed on individual Fastq files as part of the cgatflow pipelines readqc, rnaseqqc and bamstats (42). In summary, fastq quality was evaluated using FastQC (0.11.2) and contamination by other organisms was excluded using FastQ Screen (0.4.4). Files were not trimmed. Mapping quality control included Picard (1.106) metrics, and plotting of alignment statistics, mapping statistics, library complexity, splicing statistics as well as gene profile plots for assessment of coverage and fragmentation biases.

Differential expression analysis

Transcripts per million (TPM) and counts tables were obtained using Salmon (0.8.2 (43)) with kmer size option 31 and index option fmd. Salmon results were imported into R using tximport (1.10.0 (44)). Following variance-stabilizing transformation of the counts table, exploratory data analysis was performed using heat maps, hierarchical clustering and principal component analysis. Differential expression analysis was performed DESeq2 (1.22.1 (45)), including the person performing the differentiation as a factor in the model, to account for variability across differentiations. Multiple testing correction was performed using the Benjamini–Hochberg correction. The significance of the differential expression results was ascertained using 1000 simulations using random permutations of the group label across all samples with replacement.

Overrepresentation and enrichment analysis

The results were interpreted using annotations from the gene ontology (GO) database, KEGG database and the mouse genome informatics (MGI) database. RNA Sequins were analyzed by providing TPMs and differential expression results tables to RAnaquin (1.2.0 (46)). GSEA and was performed using fgsea (1.8.0 (47)), and leading edge analysis was performed using the GSEA desktop application (48).

qPCR for validation

Validation of RNA sequencing results was performed on an extended sample cohort that included 10 genome edited samples, 10 control samples, six C9-02-02 samples and four samples from the C9-02-03 clone from independent differentiations. Following RNA extraction with the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN), cDNA was prepared using the high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Primers for qPCR were validated using control iPSMN cDNA with five serial 1:5 dilutions and included an RT- control. Primer sequences are shown in Supplementary Material, Table S4. qPCR was performed using the Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using 0.2 μl of cDNA and 250 μm primers. About 20 μl samples were run in triplicate on the Lightcycler480 (Roche) using standard cycling conditions. Three reference genes were used for all reactions (TOP1, RPL13A and ATP5B), and the geometric mean of all three genes was used as the reference for gene expression estimation. Relative abundance estimation was carried out using the 2-ΔΔCt method.

Western blotting

Protein was extracted for iPSMN cultures at Day 30 using radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA) buffer with protease inhibitors and combined with sample reducing agent and lithium dodecyl sulfate (LDS) sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Samples were not heated (except C9orf72) and run in precast NuPAGE 4–12% bis-tris gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 100 V for 100 min. Protein was transferred on nitrocellulose membranes using the iBlot2 dry blotting system (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and blocked in TBS with 10% skimmed milk containing 0.1% Tween-20. Primary antibodies C9orf72 (1:1000, clone 3H10, gift from Nicolas Charlet-Berguerand (26)) SV2A (1:1000, Synaptic Systems 119002) and Syt11 (1:1000, Abcam ab204589) were incubated for 2 h followed by three washes and either anti-mouse HRP-linked (GE Healthcare, 1:10 000) or fluorescent secondary antibody incubation (Licor 800CW and 680RD, 1:10 000). Membranes were visualized in a ChemiDoc imaging system (BioRad).

Data analysis and statistics for molecular biology experiments

Statistical analyses and data visualizations other than for sequencing analysis were performed using GraphPad Prism. Venn Diagrams were drawn with Venny (49).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the High-Throughput Genomics Group at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics (funded by Wellcome Trust grant reference 090532/Z/09/Z) for the generation of the sequencing data. We would like to thank Dr Timothy R. Mercer and the Garvan Institute of Medical Research for the provision of sequin spike-ins.

Funding

Motor Neurone Disease Association (945-795 to J.S., 832-791 to K.T.); Medical Research Council (MR/L002167/1 to J.S.); University of Jordan (scholarship to N.A.); ‘All About Alie’ (to K.T.); Academy of Medical Sciences (SGL014\1004 to A.D.); National Institute for Health Research (CL-2015-26-001 to A.D.); Wellcome Trust (WTISSF121302 to S.C.); Oxford Martin School (LC0910-004 to S.C.); Parkinson’s UK (Monument Trust Discovery Award to S.C.); European Union Innovative Medicines Initiative (StemBANCC) (115439 to R.F.).

EU IMI provides the following statement: The research leading to these results has received support from the Innovative Medicines Initiative Joint Undertaking under grant agreement no 115439, resources of which are composed of financial contribution from the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7/2007-2013) and EFPIA companies’ in kind contribution. This publication reflects only the author’s views and neither the IMI JU www.imi.europa.eu nor EFPIA nor the European Commission are liable for any use that may be made of the information contained therein.

Conflict of Interest statement

We declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; ChAT, choline acetyl transferase; DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; DNA, deoxyribonucleic acid; dNTP, deoxynucleotide; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; FGF, fibroblast growth factor; FISH, fluorescence in situ hybridization; FTD, frontotemporal dementia; GDNF, glial-cell derived neurotrophic factor; GO, gene ontology; HRE, hexanucleotide repeat expansion; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell; iPSMN, induced pluripotent stem cell derived motor neuron; KEGG, Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes; MGI, mouse genome informatics; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; qPCR, quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction; RNA, ribonucleic acid; RRM, RNA recognition motif; RT-PCR, reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; SSC, sodium-saline citrate; TBS, tris-buffered saline; WT, wild-type

References

- 1. Chio A., Mora G., Leone M., Mazzini L., Cocito D., Giordana M.T., Bottacchi E., Mutani R. and Piemonte and Valle d’Aosta Register for ALS (2002) Early symptom progression rate is related to ALS outcome: a prospective population-based study. Neurology, 59, 99–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ling S.-C., Polymenidou M. and Cleveland D.W. (2013) Converging mechanisms in ALS and FTD: disrupted RNA and protein homeostasis. Neuron, 79, 416–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Majounie E., Renton A.E., Mok K., Dopper E.G.P.P., Waite A., Rollinson S., Chiò A., Restagno G., Nicolaou N., Simon-Sanchez J. et al. (2012) Frequency of the C9orf72 hexanucleotide repeat expansion in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Neurol., 11, 323–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Smith B.N., Newhouse S., Shatunov A., Vance C., Topp S., Johnson L., Miller J., Lee Y., Troakes C., Scott K.M. et al. (2013) The C9ORF72 expansion mutation is a common cause of ALS+/−FTD in Europe and has a single founder. Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 21, 102–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. van Blitterswijk M., DeJesus-Hernandez M., Niemantsverdriet E., Murray M.E., Heckman M.G., Diehl N.N., Brown P.H., Baker M.C., Finch N.A., Bauer P.O. et al. (2013) Association between repeat sizes and clinical and pathological characteristics in carriers of C9ORF72 repeat expansions (Xpansize-72): a cross-sectional cohort study. Lancet Neurol., 12, 978–988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nordin A., Akimoto C., Wuolikainen A., Alstermark H., Jonsson P., Birve A., Marklund S.L., Graffmo K.S., Forsberg K., Brännström T. et al. (2015) Extensive size variability of the GGGGCC expansion in C9orf72 in both neuronal and non-neuronal tissues in 18 patients with ALS or FTD. Hum. Mol. Genet., 24, 3133–3142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mori K., Weng S.-M., Arzberger T., May S., Rentzsch K., Kremmer E., Schmid B., Kretzschmar H.A., Cruts M., Van Broeckhoven C. et al. (2013) The C9orf72 GGGGCC repeat is translated into aggregating dipeptide-repeat proteins in FTLD/ALS. Science (80- ), 339, 1335–1338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mackenzie I.R.A., Frick P., Grässer F.A., Gendron T.F., Petrucelli L., Cashman N.R., Edbauer D., Kremmer E., Prudlo J., Troost D. et al. (2015) Quantitative analysis and clinico-pathological correlations of different dipeptide repeat protein pathologies in C9ORF72 mutation carriers. Acta Neuropathol., 130, 845–861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. DeJesus-Hernandez M., Mackenzie I.R., Boeve B.F., Boxer A.L., Baker M., Rutherford N.J., Nicholson A.M., Finch N.A., Flynn H., Adamson J. et al. (2011) Expanded GGGGCC hexanucleotide repeat in noncoding region of C9ORF72 causes chromosome 9p-linked FTD and ALS. Neuron, 72, 245–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Dafinca R., Scaber J., Ababneh N., Lalic T., Weir G., Christian H., Vowles J., Douglas A.G.L.A.G.L.L., Fletcher-Jones A., Browne C. et al. (2016) C9orf72 hexanucleotide expansions are associated with altered endoplasmic reticulum calcium homeostasis and stress granule formation in induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neurons from patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal demen. Stem Cells, 34, 2063–2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sareen D., O’Rourke J.G., Meera P., Muhammad A.K.M.G., Grant S., Simpkinson M., Bell S., Carmona S., Ornelas L., Sahabian A. et al. (2013) Targeting RNA foci in iPSC-derived motor neurons from ALS patients with a C9ORF72 repeat expansion. Sci. Transl. Med., 5, 208ra149–208ra149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Donnelly C.J., Zhang P.W., Pham J.T., Heusler A.R., Mistry N.A., Vidensky S., Daley E.L., Poth E.M., Hoover B., Fines D.M. et al. (2013) RNA toxicity from the ALS/FTD C9ORF72 expansion is mitigated by antisense intervention. Neuron, 80, 415–428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhang K., Donnelly C.J., Haeusler A.R., Grima J.C., Machamer J.B., Steinwald P., Daley E.L., Miller S.J., Cunningham K.M., Vidensky S. et al. (2015) The C9orf72 repeat expansion disrupts nucleocytoplasmic transport. Nature, 525, 56–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Haeusler A.R., Donnelly C.J., Periz G., Simko E.A.J., Shaw P.G., Kim M.-S., Maragakis N.J., Troncoso J.C., Pandey A., Sattler R. et al. (2014) C9orf72 nucleotide repeat structures initiate molecular cascades of disease. Nature, 507, 195–200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Devlin A.-C., Burr K., Borooah S., Foster J.D., Cleary E.M., Geti I., Vallier L., Shaw C.E., Chandran S. and Miles G.B. (2015) Human iPSC-derived motoneurons harbouring TARDBP or C9ORF72 ALS mutations are dysfunctional despite maintaining viability. Nat. Commun., 6, 5999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Selvaraj B.T., Livesey M.R., Zhao C., Gregory J.M., James O.T., Cleary E.M., Chouhan A.K., Gane A.B., Perkins E.M., Dando O. et al. (2018) C9ORF72 repeat expansion causes vulnerability of motor neurons to Ca2+−permeable AMPA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity. Nat. Commun., 9, 347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang L., Yi F., Fu L., Yang J., Wang S., Wang Z., Suzuki K., Sun L., Xu X., Yu Y. et al. (2017) CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted gene correction in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis patient iPSCs. Protein Cell, 8, 365–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bhinge A., Namboori S.C., Zhang X., VanDongen A.M.J. and Stanton L.W. (2017) Genetic correction of SOD1 mutant iPSCs reveals ERK and JNK activated AP1 as a driver of neurodegeneration in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Stem Cell Rep., 8, 856–869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kiskinis E., Sandoe J., Williams L.A., Boulting G.L., Moccia R., Wainger B.J., Han S., Peng T., Thams S., Mikkilineni S. et al. (2014) Pathways disrupted in human ALS motor neurons identified through genetic correction of mutant SOD1. Cell Stem Cell, 14, 781–795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Raitano S., Ordovàs L., De Muynck L., Guo W., Espuny-Camacho I., Geraerts M., Khurana S., Vanuytsel K., Tóth B.I., Voets T. et al. (2015) Restoration of progranulin expression rescues cortical neuron generation in an induced pluripotent stem cell model of frontotemporal dementia. Stem Cell Rep., 4, 16–24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shen B., Zhang W., Zhang J., Zhou J., Wang J., Chen L., Wang L., Hodgkins A., Iyer V., Huang X. et al. (2014) Efficient genome modification by CRISPR-Cas9 nickase with minimal off-target effects. Nat. Methods, 11, 399–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cohen-Hadad Y., Altarescu G., Eldar-Geva T., Levi-Lahad E., Zhang M., Rogaeva E., Gotkine M., Bartok O., Ashwal-Fluss R., Kadener S. et al. (2016) Marked differences in C9orf72 methylation status and isoform expression between C9/ALS human embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep., 7, 927–940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Belzil V.V., Bauer P.O., Prudencio M., Gendron T.F., Stetler C.T., Yan I.K., Pregent L., Daughrity L., Baker M.C., Rademakers R. et al. (2013) Reduced C9orf72 gene expression in c9FTD/ALS is caused by histone trimethylation, an epigenetic event detectable in blood. Acta Neuropathol., 126, 895–905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Liu E.Y., Russ J., Wu K., Neal D., Suh E., McNally A.G., Irwin D.J., Van Deerlin V.M. and Lee E.B. (2014) C9orf72 hypermethylation protects against repeat expansion-associated pathology in ALS/FTD. Acta Neuropathol., 128, 525–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Russ J., Liu E.Y., Wu K., Neal D., Suh E., Irwin D.J., McMillan C.T., Harms M.B., Cairns N.J., Wood E.M. et al. (2015) Hypermethylation of repeat expanded C9orf72 is a clinical and molecular disease modifier. Acta Neuropathol., 129, 39–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Boivin M., Pfister V., Gaucherot A., Ruffenach F., Negroni L., Sellier C. and Charlet-Berguerand N. (2020) Reduced autophagy upon C9ORF72 loss synergizes with dipeptide repeat protein toxicity in G4C2 repeat expansion disorders. EMBO J., 39, e100574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sznajder Ł.J., Thomas J.D., Carrell E.M., Reid T., McFarland K.N., Cleary J.D., Oliveira R., Nutter C.A., Bhatt K., Sobczak K. et al. (2018) Intron retention induced by microsatellite expansions as a disease biomarker. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 115, 4234–4239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Abo-Rady M., Kalmbach N., Pal A., Schludi C., Janosch A., Richter T., Freitag P., Bickle M., Kahlert A.K., Petri S. et al. (2020) Knocking out C9ORF72 exacerbates axonal trafficking defects associated with hexanucleotide repeat expansion and reduces levels of heat shock proteins. Stem Cell Rep., 14, 390–405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Love M.I., Anders S. and Huber W. (2014) Differential Analysis of Count Data—the DESeq2 Package, Vol. 15. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Almeida S., Gascon E., Tran H., Chou H.J., Gendron T.F., Degroot S., Tapper A.R., Sellier C., Charlet-Berguerand N., Karydas A. et al. (2013) Modeling key pathological features of frontotemporal dementia with C9ORF72 repeat expansion in iPSC-derived human neurons. Acta Neuropathol., 126, 385–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Renton A.E., Chiò A. and Traynor B.J. (2014) State of play in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis genetics. Nat. Neurosci., 17, 17–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Blitterswijk M., van Es M.A., Hennekam E.A.M., Dooijes D., van Rheenen W., Medic J., Bourque P.R., Schelhaas H.J., van der Kooi A.J., de Visser M. et al. (2012) Evidence for an oligogenic basis of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Hum. Mol. Genet., 21, 3776–3784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K.M., Aach J., Guell M., DiCarlo J.E., Norville J.E. and Church G.M. (2013) RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science (80-), 339, 823–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ran F.A., Hsu P.D., Wright J., Agarwala V., Scott D.A. and Zhang F. (2013) Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc., 8, 2281–2308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lopez-Gonzalez R., Yang D., Pribadi M., Kim T.S., Krishnan G., Choi S.Y., Lee S., Coppola G. and Gao F.-B. (2019) Partial inhibition of the overactivated Ku80-dependent DNA repair pathway rescues neurodegeneration in C9ORF72-ALS/FTD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., 116, 9628–9633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Zhang Y.-J., Jansen-West K., Xu Y.-F., Gendron T.F., Bieniek K.F., Lin W.-L., Sasaguri H., Caulfield T., Hubbard J., Daughrity L. et al. (2014) Aggregation-prone c9FTD/ALS poly(GA) RAN-translated proteins cause neurotoxicity by inducing ER stress. Acta Neuropathol., 128, 505–524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Renton A.E., Majounie E., Waite A., Simón-Sánchez J., Rollinson S., Gibbs J.R., Schymick J.C., Laaksovirta H., van Swieten J.C., Myllykangas L. et al. (2011) A hexanucleotide repeat expansion in C9ORF72 is the cause of chromosome 9p21-linked ALS-FTD. Neuron, 72, 257–268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Maury Y., Côme J., Piskorowski R.A., Salah-Mohellibi N., Chevaleyre V., Peschanski M., Martinat C. and Nedelec S. (2014) Combinatorial analysis of developmental cues efficiently converts human pluripotent stem cells into multiple neuronal subtypes. Nat. Biotechnol., 33, 89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Xi Z., Zinman L., Moreno D., Schymick J., Liang Y., Sato C., Zheng Y., Ghani M., Dib S., Keith J. et al. (2013) Hypermethylation of the CpG island near the G4C2 repeat in ALS with a C9orf72 expansion. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 92, 981–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mizielinska S., Lashley T., Norona F.E., Clayton E.L., Ridler C.E., Fratta P. and Isaacs A.M. (2013) C9orf72 frontotemporal lobar degeneration is characterised by frequent neuronal sense and antisense RNA foci. Acta Neuropathol., 126, 845–857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M. and Gingeras T.R. (2013) STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics, 29, 15–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]