Abstract

Phospholipid signaling has clear connections to a wide array of cellular processes, particularly in gene expression and in controlling the chromatin biology of cells. However, most of the work elucidating how phospholipid signaling pathways contribute to cellular physiology have studied cytoplasmic membranes, while relatively little attention has been paid to the role of phospholipid signaling in the nucleus. Recent work from several labs has shown that nuclear phospholipid signaling can have important roles that are specific to this cellular compartment. This review focuses on the nuclear phospholipid functions and the activities of phospholipid signaling enzymes that regulate metazoan chromatin and gene expression. In particular, we highlight the roles that nuclear phosphoinositides play in several nuclear-driven physiological processes, such as differentiation, proliferation, and gene expression. Taken together, the recent discovery of several specifically nuclear phospholipid functions could have dramatic impact on our understanding of the fundamental mechanisms that enable tight control of cellular physiology.

Keywords: chromatin, gene expression, nuclear phospholipid signaling, phosphoinositides

1 |. INTRODUCTION

The ability of metazoans to control cellular physiology is fundamentally regulated at the level of transcription. Metazoan gene expression is modulated through several mechanisms, including compaction and de-compaction of chromatin, recruitment of transcription factors to DNA, RNA polymerase II activity, among many others (Phillips, 2008). RNA messages must then be modified to enhance stability and for export to the cytoplasm where translation takes place. This review summarizes recent data indicating that nuclear phospholipids and phospholipid signaling enzymes play critical roles in all of these important nuclear processes.

2 |. PHOSPHOLIPIDS PLAY WELL-KNOWN ROLES IN CELLULAR MEMBRANE PHYSIOLOGY

Proliferating cells depend on membrane phospholipids to proliferate and maintain homeostasis (Fritz & Fajas, 2010). Phospholipids make up the bulk of membranes that encase all mammalian cells, and all membranes must grow and increase in volume proportional to the rate of proliferation. Thus, cells require significant membrane biosynthesis to survive, and it is unsurprising that phospholipid biosyntheticpathways are up-regulated in many human pathologies where cellular growth is required, such as cancer (Baenke, Peck, Miess, & Schulze, 2013; Garcia-Gil & Albi, 2017). However, it is well known that signaling pathways use phospholipids as second messengers to participate in cellular processes that are independent of membrane anabolism; including calcium signaling, transcriptional regulation and apoptosis, in addition to cellular proliferation (Cascianelli et al.,, 2008). The p110 phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3-kinases) are well established to drive proliferation, extensively reviewed elsewhere (Chalhoub & Baker, 2009). This particular function of membrane phospholipids has been enormously important to both our understanding of cellular signaling and the development of anti-cancer therapeutics (Liu, Thoreen, Wang, Sabatini, & Gray, 2009).

3 |. NUCLEAR PHOSPHOLIPIDS EXIST OUTSIDE MEMBRANES, WITHIN THE NUCLEOPLASM

Several decades of biochemical observations as well as more recent structural studies have established that phospholipids in the nucleus can exist outside of membranes bound to non-membrane, water-soluble proteins (Figure 1). Similar observations have been made in all eukaryotic organisms examined to date, including yeast (Alcázar-Román, Tran, Guo, & Wente, 2006; Drobak & Heras, 2002; Odom, Stahlberg, Wente, & York, 2000; Shen, Xiao, Ranallo, Wu, & Wu, 2003; Steger, Haswell, Miller, Wente, & O’Shea, 2003; York, Armbruster, Greenwell, Petes, & York, 2005), plants (Cheng & Shearn, 2004; Dieck, Wood, Brglez, Rojas-Pierce, & Boss, 2012; Mishkind, Vermeer, Darwish, & Munnik, 2009;), insects (Tilley, Evans, Larson, Edwards, & Friesen, 2008), nemtodes, (Mullaney et al., 2010), and humans (Berezney & Coffey, 1974; Cocco et al., 1988; Krylova et al., 2005; Manzoli, Maraldi, Cocco, Capitani, & Facchini, 1977). Very hydrophobic fatty acids, sterols, sphingosines, and phospholipids have all been observed outside nuclear membranes within the nucleoplasm, and have also been linked to transcriptional control (Blind, Suzawa, & Ingraham, 2012; Burris et al., 2013; Hait et al., 2009; Levi et al., 2013; Manzoli, Muchmore, Bonora, Capitani, & Bartoli, 1974; Sablin et al., 2015). Electron microscopy experiments suggest that removing the nuclear envelope with mild non-ionic detergents can leave a significant amount of phospholipid remaining within the nucleoplasm (Rose & Frenster, 1965). Radioisotope metabolic labeling has further determined that the phospholipid mass that can be extracted from active chromatin is far greater than the phospholipid mass that can be extracted from repressed chromatin or reconstituted DNA (Manzoli et al., 2005; Shepherd, Noland, & Roberts, 1970). But perhaps the best evidence that nuclear phospholipids are distinct from membrane phospholipids is the observation that the nuclear pool of phosphoinositides can be metabolized distinctly from the plasma membrane pool of phosphoinositides (Lindsay et al., 2006). While membrane phospholipids and phospholipid signaling enzymes are well studied in growth and proliferation, non-membrane nuclear phospholipids have only recently been recognized as relevant factors participating in nuclear regulatory activities (Irvine, 2003; Martelli et al., 2011; Shah et al., 2013; York, 2006; Tribble et al., 2016).

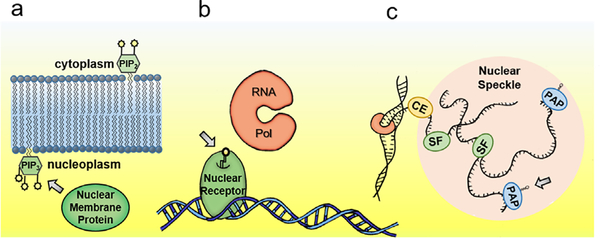

FIGURE 1.

Lipids play key regulatory roles within the nucleus. Within membranes lipids (a) initiate signal cascades via recruitment of nuclear membrane proteins, as is the case in the best understood pathways correlated with extracellular signaling such as hormonal, cell migration signaling, inflammation or apoptotic response, and intracellular metabolic pathways such as the mTOR pathway; (b) as activators of nuclear receptors that activate or repress transcription, as is the case in PPAR-associated transcription and SF-1 targeted expression; and (c) within enigmatic nuclear micro-structures, such as nuclear speckles, where phospholipids mediate mRNA splicing factor activity (SF), polyadenylating polymerase activity (PAP) and modifications such as mRNA capping (CE). All these important activities highlight the importance of nuclear phospholipids in cellular physiology

4 |. NUCLEAR PHOSPHOINOSITIDES HAVE HIGH INFORMATION STORAGE POTENTIAL

Phosphoinositide phospholipids are perhaps the best studied of all the nuclear phospholipids. These potent signaling molecules have significant potential to store biological information in the nucleus. When thought of in simple binary terms, each of the 3, 4, and 5-positions on the D-myo-inositol headgroup ring of phosphoinositides can exist in a phosphorylated or un-phosphorylated state, variations on which can yield 64 unique molecules, which has been described as a 6-bit electric circuit (York, 2006). Despite this intriguing potential, it is poorly described how any nuclear phosphoinositide might elicit an effect outside a membrane system. Moreover, how hydrophobic phospholipid molecules, which will spontaneously form membrane-like structures in water, can remain soluble in the aqueous nucleoplasm has remained an area of speculation and conjecture for many decades (Barlow, Laishram, & Anderson, 2010; Irvine, 2003).

5 |. ORPHAN NUCLEAR RECEPTOR LIGANDS ARE HYDROPHOBIC, NUCLEAR SMALL SIGNALING MOLECULES

Hydrophobic, cholesterol-based molecules (e.g., steroids and oxysterols), fatty acids, and some phospholipids can serve as hormone-like ligands for the nuclear receptor superfamily, which are ligand-regulated transcription factors that control transcriptional activation and repression (reviewed in Benoit et al., 2006). In early work, nuclear receptors were identified using these hormones as bait. The advent of sequencing yielded many genes related to characterized nuclear receptors, but with unknown hormone ligands. Indeed, many of the nuclear receptors identified in humans are called “orphan receptors” as these receptors were identified by homology, not by direct ligand binding (Burris et al., 2013). The complete mechanism describing orphan nuclear receptor regulation is incompletely understood (Benoit et al., 2006). Despite this, orphan nuclear receptors regulate a wide range of extremely important physiologic and developmental processes, and continue to serve as excellent targets for drugs controlling a wide array of human pathologies (Cantello et al., 1994).

Phospholipid interactions with nuclear receptors could conceivably explain the presence of non-membrane phospholipids observed in animals. However, since the nuclear receptor superfamily is restricted to metazoans, non-membrane nuclear phospholipids cannot be explained in species that do not contain nuclear receptors in their genomes, such as plants and yeast. Further, only a very small fraction of nuclear receptors are capable of interacting with phospholipids in vitro, further suggesting that other soluble, nuclear proteins that are more evolutionarily conserved interact with nuclear phospholipids to hold them soluble within the nucleoplasm.

6 |. PHOSPHOLIPIDS CAN BE SHUTTLED IN THE NUCLEUS

While it is known that several phospholipid-derived ligands can associate with nuclear receptors, the means by which these very hydrophobic molecules come to bind soluble nuclear receptors is not well understood (Figure 2). The hydrophobic tails of phospholipids are typically buried within the bilayer of a membrane, and the polar head group is solvent exposed on the surface of the membrane where it can function in signaling to recruit proteins to the membrane (Lemmon, 2008). How nuclearreceptors come to possess phospholipid ligands is far less well understood than howphospholipids can transfer between their site of synthesis in the endoplasmic reticulum and noncontiguous cellular compartments (Blind, 2014). In the next section, we review the data indicating that hydrophobic lipid ligands can be transferred via phospholipid shuttling proteins.

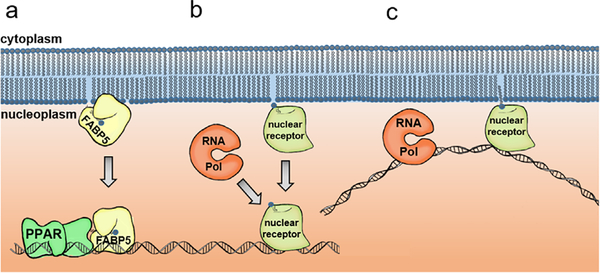

FIGURE 2.

Possible mechanisms describing how phospholipids reach soluble nuclear receptors. (a) FABP5 is a well-studied shuttle protein that transfers yet unknown lipid ligands to its target nuclear receptor, PPAR, which plays an important role in differentiation, development and metabolism. (b) It is still unknown whether such nuclear receptors as SF-1 retrieve lipid ligands from the inner leaflet of the nuclear membrane and then migrate to the surface of chromatin to enact transcriptional changes, or whether the lipid ligand is shuttled to the nuclear receptor by an unknown vector. (c) It is also possible that nuclear receptors bridge chromatin and lipid ligands within intranuclear membranes, as it has been shown that various loci can co-localize at perinuclear locations, possibly by DNA tethering membrane-based proteins

7 |. FABP5 MEDIATES PPAR LIGAND BINDING

Fatty Acid Binding Protein 5 (FABP5) delivers lipid ligands from the cytosol directly to the nuclear receptor PPARβ/δ; Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARs) are nuclear receptors that play a role in the regulation of cellular growth (Tachibana, Yamasaki, Ishimoto, & Doi, 2008). Binding of FABP5 to PPAR facilitates lipid binding to PPAR and stimulation of transcription. PPAR activation can dramatically alter genome expression patterns and cellular physiology, including increasing the tumorigenic potential of prostate cancer cell lines (Morgan, Kannan-Thulasiraman, & Noy, 2010). While the physiological ligands of FABP5 are unknown, biochemical analyses have shown that FABP5 has highest affinity for long-chain fatty acids, and crystal structures where FABP5 is incubated with palmitic acid or linoleic acid show that FABP5 completely envelopes these fatty acids (Hohoff, Börchers, Rüstow, Spener, & van Tilbeurgh, 1999). This mechanism of protecting the lipid from the polar solvent of an aqueous environment provides a general mechanism for lipid solubility once that have arrived at their target receptor (Armstrong, Goswami, Griffin, Noy, & Ortlund, 2014). However, it remains very unclear if all nuclear lipids are shuttled by binding proteins. It is very important to note that the purified ligand binding domains of the NR5A class of nuclear receptors (NR5A1, Steroidogenic Factor-1, or NR5A1; and NR5A2, Liver Receptor Homolog-1, or LRH-1) can acquire phospholipids from any membrane system in vitro, without the aid of any transfer protein whatsoever. Thus, although transfer proteins such as FABP5 are capable of helping particular nuclear receptors acquire hydrophobic ligands, it is unclear if any regulatory mechanisms consistently aid in lipid transfer to nuclear receptors.

8 |. PHOSPHOLIPIDS CAN BE MODIFIED WHILE ASSOCIATED WITH NUCLEAR PROTEINS

Phospholipids are best known to function as signaling molecules at membranes, where they act as docking surfaces to scaffold signaling enzymes. Considering the structure of FABP5 shuttle protein and its fatty acid ligands, it could be expected that once incorporated into a nuclear receptor, a phospholipid ligand might remain statically bound to the nuclear receptor. Indeed, recent work described below demonstrates that phospholipids bound to nuclear receptors can have solvent-exposed groups can be directly modified by certain phospholipid signaling enzymes while the nuclear phospholipid remains statically bound to a soluble protein receptor.

9 |. PIP2 BOUND TO THE NUCLEAR RECEPTOR NR5A1 CAN BE DIRECTLY MODIFIED

NR5A1 (Steroidogenic Factor 1, SF-1) was originally identified as a transcription factor that binds to DNA regulatory elements in the proximal promoter regions of steroidogenic enzyme genes, and is considered a master regulator of steroidogenesis (Parker et al., 2002). NR5A1 transcriptionally regulates genes important in sexual development and reproduction, especially the target gene Steroidogenic Acute Regulatory protein (StAR), which has been found to have anti-apoptotic effects in fibroblasts (Anuka et al., 2013). NR5A1 can accommodate several phospholipid- derived ligands in its binding pocket (Bunce, Bergendahl, & Anderson, 2006; Krylova et al., 2005; Sablin et al., 2009). The NR5A1 phospholipid binding domain structurally engulfs the acyl chain groups of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) phospholipids, but the polar phosphate head groups are solvent-exposed (Blind, 2014). PIP2 is a critical small signaling molecule in both the cytosolic and nuclear phosphoinositide cycles (Whitman, Downes, Keeler, Keller, & Cantley, 1988). PIP2 can be phosphorylated by membrane phosphoinositol-3-kinases(PI3Ks)toproducemembrane PIP3, the mostpotentandleast abundant phosphoinositide signaling molecule, which activates AKT to regulate cell growth and survival (Auger, Serunian, Soltoff, Libby, & Cantley, 1989; Myers et al., 1998).

Kinase assays using NR5A1-PIP2 as a substrate showed that Inositol Polyphosphate Multi-Kinase (IPMK), but not the p110 PI3Ks, phosphorylates PIP2 while PIP2 is bound in the pocket of NR5A1, generating PIP3 bound to NR5A1 (Figure 3). Treatment of NR5A1-PIP2 complexes with phospholipid-displacing synthetic ligand RJW100, which displaces PIP2 from NR5A1, prevents IPMK from incorporating any radiolabel into the PIP2/NR5A1 substrate. Further kinetic experiments showed that IPMK prefers to phosphorylate PIP2 when PIP2 is bound to NR5A1, rather than PIP2 bound in membrane systems such as micelles or vesicles. Indeed, IPMK shows a sixfold increase in the specificity constant (apparent KM/apparent VMAX)on NR5A1-PIP2 when compared to PIP2 in membranes. This novel activity shows that not only do nuclear phospholipids exist outside membranes, but that non-membrane phospholipids can be selectively and specifically phosphorylated while bound to nuclear proteins. These data indicate an important role for phospholipid-signaling enzymes beyond the plasma membrane. Cell physiological effects of this modification become apparent when knock down of IPMK using small-interfering RNAs (siRNA) and chemical inhibitors of IPMK activity resulted in decreased expression of NR5A1 targeting genes. The PIP3 phosphatase activity antagonizing IPMK kinase activity was then discovered to be PTEN. Complementing PTEN back into PTEN negative cell lines resulted in a decrease in NR5A1 activity. In vitro assays showed that PTEN efficiently counteracts IPMK activity by removing radiolabeled phosphate from NR5A1-PIP3 with outstanding kinetic properties compared to more well established PTEN substrates. These data show that dephosphorylation of nuclear PIP3 while bound to a nuclear protein is possible within a more physiologically relevant setting. PTEN has lost function in many human cancers, and PTEN’s most well characterized cellular target is PIP3 (Clarke et al., 2001). These results bring to light new questions: Do PTEN and IPMK act in a similar fashion on other phospholipid-binding nuclear proteins across the genome? If so, what regulatory processes do these enzyme activities affect? Do these activities provide a new mechanism by which we can pharmacologically target PTEN-dependent cancers? The transcriptional regulation of NR5A1 by PTEN and IPMK remodeling PIP2 and PIP3 bound to this nuclear protein, coupled with the widespread observations of non-membrane nuclear phospholipids, are consistent with a new model of nuclear phospholipid signaling where nucleoprotein/phospholipid complexes are unique substrates for lipid signaling enzymes in this cellular compartment.

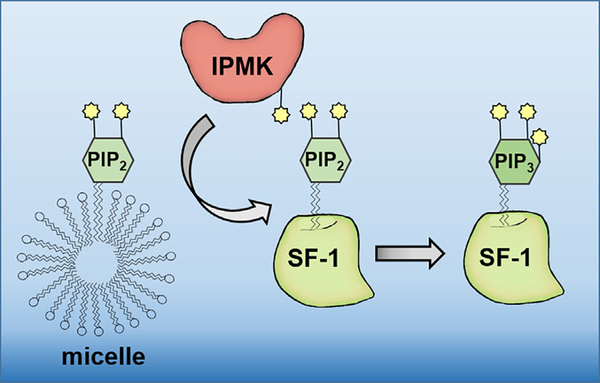

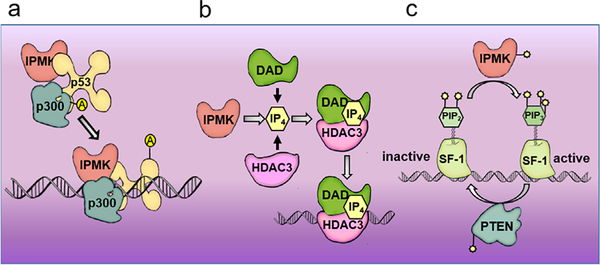

FIGURE 3.

Phosphoinositides can be specifically modified while bound to nuclear proteins. IPMK is capable of phosphorylating phosphatidylinositol-4,5-phosphate (PIP2) with excellent enzyme kinetics when PIP2 was seeded within the transcription factor SF-1, but IPMK is a much poorer enzyme acting on PIP2 help within phospholipid micelles, more accurately representing a typical cytoplasmic membrane context

10 |. PHOSPHOLIPID SIGNALING ENZYMES IN THE NUCLEUS REGULATE GENE EXPRESSION

While PTEN and IPMK are important phospholipid signaling enzymes, other classic phospholipid signaling enzymes are also present in the nucleus as well as their phospholipid substrates and products. Levels of phospholipids and the enzymes that regulate phospholipid production fluctuate depending on developmental stage and position in the cell cycle (Park et al., 2012). While nuclear phospholipid-modifying enzymes haveclear effects on regulationof geneexpression (Bunce et al., 2006), the mechanisms whereby these enzymes elicit nuclear effects are still not well-defined. This is a very important question to answer biomedically as the activity of nuclear phospholipid modifying enzymes is often highly correlated with transformation and tumor malignancy.

11 |. NUCLEAR PHOSPHOLIPASE C (PLC) ACTIVITIES ARE ROBUST

Phospholipase C (PLC) is a phospholipid signaling enzyme with several isoforms present in both the cytoplasm and nucleus, all of which contain a phospholipid-interacting Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain (Paris et al., 2010). Several Phospholipase C isozymes are deregulated in cancer and play important roles in cell proliferation, migration, survival, and death (Bertagnolo et al., 2006; Danielsen et al., 2011; Lattanzio, Piantelli, & Falasca, 2013; Paris et al., 2010) (Figure 4). The PLCβ2 isoform is highly expressed in a large majority of breast tumor samples, its expression correlated with size, proliferation index, final grade, and predicted poor prognosis (Leung et al., 2004). Up-regulation of PLCγ4 gene expression is linked with rapid proliferation and activation of the ERK mitogenic pathway which itself induces tumorigenic gene expression (Albi et al., 2003). The nuclear isoforms of phospholipase C (PLC) are implicated in cell cycle control, and different isoforms appear to play discriminate roles in cell cycle progression. PLCβ1 associates with DNA replication sites within chromatin and may trigger DNA replication (Poli et al., 2016). Meanwhile the γ isoform associates with the nuclear membrane and may be involved in G2/M phase transition (Poli et al., 2016). While not well understood mechanistically, these processes imply that PLC enzymes could play a role in regulating proliferative gene expression within the nucleus, reviewed elsewhere (Matteucci et al., 1998).

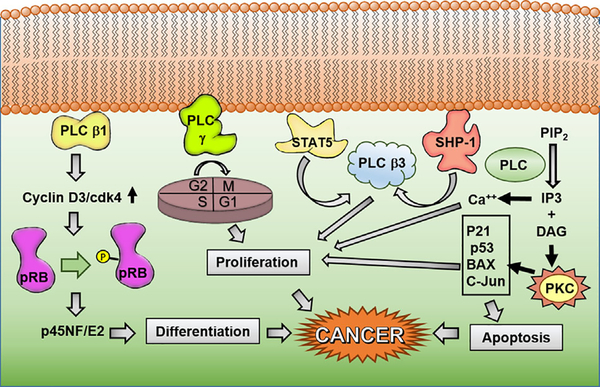

FIGURE 4.

Phospholipase C (PLC) isoforms regulate many signaling pathways. Each isoform is involved in proliferation and growth, including up-regulation of expression of cell cycle genes, mediating checkpoints, calcium signaling involved in gene expression and kinase activation, differentiation, DNA damage response genes and other intranuclear pathways involved in apoptotic gene expression

12 |. NUCLEAR, BUT NOT CYTOPLASMIC PLCβ-ACTIVITY CORRELATES WITH CELL PROLIFERATION AND INHIBITION OF DIFFERENTIATION

PLCβ1 containing a nuclear localization sequence directly targets expression of transcription factor p45/NF-E2, a key regulator of differentiation, whereas transfection of PLCβ1 lacking a nuclear localization sequence has no effect (Faenza et al., 2000, 2002). Overexpression of PLCβ1 is sufficient to induce Cyclin D3 accumulation as well as cdk4 RNA. PLCβ1 also increases phosphorylation of retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein (pRb) and activates expression of the E2F transcription factor. All these events are hallmarks of up-regulated progression through G1 cell cycle phase (Xiao et al., 2009). The effects of phospholipase C on cancer gene expression are mostly conducted through signaling of its enzymatic products, however PLCβ3 is also known to act as an adapter protein, mediating the interaction of the SHP-1 phosphatase with Stat5 (Xiao et al., 2009). This explains why PLCβ3 knockout mice have an increased proliferation of pro-acute lymphoblastic and myeloid leukemia blood cells (Xiao et al., 2009).

The classic PLC-Calcium signaling pathway (Streb, Irvine, Berridge, & Schulz, 1983) showed that PLC-mediated cleavage of the bond between the glycerol and phosphate groups of the signaling molecule phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) yields diacylglycerol (DAG) and inositol-1,4,5-triphosphate (IP3) in the cytoplasm. Nuclear IP3 is also involved in nuclear calcium dynamics, which are important for gene expression (Bading, Hardingham, Johnson, & Chawla, 1997). Nuclear, but not cytosolic Ca2+ regulates hepatocyte proliferation, and interestingly impaired nuclear Ca2+ signaling can sensitize adenocarcinoma cells to radiotherapy (Amaya et al., 2014; Andrade et al., 2012). Hairpin RNA-mediated knockdown of legumain results in a 50% decrease in proliferation of the SK HEP1 cells (Andrade et al., 2012).

Just as important as calcium-driven PLC signaling, the diacylglycerols (DAG)s produced by PLCs also activate members of the Protein Kinase C (PKC) family. PKCs are calcium and phospholipid-dependent serine/threonine kinases that function in numerous cell types and are implicated in tumorigenesis and metastasis in numerous cancers (Amaya et al., 2014; Koivunen, Aaltonen, & Peltonen, 2006). PKCs have a highly intricate role in modulating numerous proliferative and apoptotic pathways in the cell, and can regulate gene expression via phosphorylation of a number of known tumorigenic transcription factors including p21, p53, BAX, and C-JUN (Kang, 2014; Yamasaki, Takahashi, Pan, Yamaguchi, & Yokoyama, 2009). However, it is currently unknown if nuclear PLCβ1 functions are mediated through PKC, or occur independent of PKC functions.

13 |. NUCLEAR PLC IS DIRECTLY INVOLVED IN TRANSCRIPTIONAL REGULATION

While DAG and IP3 signaling have been well characterized, there may be more direct mechanisms of PLC activity on gene expression that have yet to be discovered. Recently it was found that PLC1p in yeast, which is most closely related to the mammalian PLCγ isoform, is required for normal levels of histone acetylation, a modification that is essential for active gene expression (Galdieri, Chang, Mehrotra, & Vancura, 2013; Rebecchi & Pentyala, 2000). Due to PLC presence in the chromatin fraction of mammalian cells, it would not be surprising if PLC were discovered to play a similar role in the regulation of mammalian histone modifications and thus transcriptional activation.

14 |. THE CHARACTERIZED NUCLEAR ACTIVITIES OF PTEN ARE PHOSPHATASE-INDEPENDENT

One of the most important nuclear phospholipid signaling enzymes is the tumor suppressor phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN), which dephosphorylates the 3-position in phosphoinositide phospholipid substrates (Maehama & Dixon, 1998; Yin & Shen, 2008). PI3K activation promotes cell survival, growth, and proliferation, and so unsurprisingly PTEN is a very common loss-of-function mutation in many human tumors (Keniry & Parsons, 2008; Leevers, Vanhaese-broeck, & Waterfield, 1999; Vivanco & Sawyers, 2002; Zhang & Yu, 2010). More than 60% of primary tumors exhibit loss or mutation of at least one PTEN allele, and homozygous inactivation of PTEN is typically associated with metastasis (Ginn-Pease & Eng, 2003; Simpson & Parsons, 2001).

The presence of PTEN in the nucleus is cell cycle dependent with high levels during G1/G0 and G2 phases and lower levels in S phase in normal cells (Chung & Eng, 2005). Shuttling of PTEN into the nucleus appears to be mediated by mono-ubiquitination at residues K289 and K13, passive diffusion and active transport through NLS-like signals (Chang et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2005; Trotman et al., 2007). Phosphorylation of PTEN is critical for translocation into the nucleus during oxidative stress in murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Lachyankar et al., 2000). There is also preferential nuclear PTEN localization in differentiated or resting cells (Jacob, Romigh, Waite, & Eng, 2009; Lian & Di Cristofano, 2005). Lower nuclear levels and high cytoplasmic levels in tumorigenic cells supports the hypothesis that presence of PTEN in the nucleus is anti-proliferative, likely because PTEN loss mimics high levels of PIP3 and growth factor stimulation (Chung & Eng, 2005; Stambolic et al., 1998; Zhang et al., 2010). When in the nucleus, PTEN is associated with cell cycle arrest DNA repair, centromere stability and apoptosis (Di Cristofano & Pandolfi, 2000). Thus, there is clear evidence that the subcellular location of PTEN correlates with the cell’s position within the cell cycle.

15 |. NUCLEAR PTEN REGULATES p53 IN A PHOSPHATASE-INDEPENDENT MANNER

The aforementioned functions are tied to PTEN’s role in stabilizing the critical tumor suppressor p53 (Parsons, 2004; Sansal & Sellers, 2004; Stambolic et al., 2001). Among its many activities, p53 induces cell cycle arrest or apoptosis in the DNA damage response. While functionally distinct, PTEN and p53 are thought to cooperatively enhance the activity of one another. A p53 binding element exists directly upstream of the PTEN gene at which p53 can bind and trans-activate the expression of PTEN (Li et al., 2006). Meanwhile, PTEN can stabilize p53 in a phosphatase-independent manner by binding p53 and acetylating it. This mechanism involves PTEN forming a complex with the histone acetyltransferase p300 in the nucleus and promoting high p53 acetylation in response to DNA damage (Li, Luo, Brooks, & Gu, 2002). Acetylation is thought to stabilize p53 protein and activate p53 sequence-specific DNA binding as well as recruit transcriptional co-activators to p53-responsive promoters (Barlev et al., 2001; Espinosa & Emerson, 2001; Levine, 1997; Liu et al., 2005).

The tumor suppressor p53 is a short-lived protein due to MDM2-mediated ubiquitination and proteasome-targeted degradation; therefore, stabilization of p53 is crucial for its tumor suppressor function (Tang, Zhao, Chen, Zhao, & Gu, 2008). Acetylation of p53 effectively excludes MDM2 from binding at p53-responsive promoters (Mayo & Donner, 2001). PTEN also aids in suppressing MDM2 translocation to the nucleus by inhibiting the AKT/PI3K pathway via de-phosphorylation of PIP3. Phosphorylation by AKT/PKB at serine 166 and serine 186 of MDM2 is necessary for translocation of MDM2 from the cytoplasm to the nucleus where it engages in p53 binding and targeting for degradation (Freeman et al., 2003).

The PTEN/p53 complex can enhance p53 DNA binding and transcriptional activity, completely independent of PTEN phosphatase activity(Eiteletal.,2009;Fritz&Fajas,2010).Infact,p53transcriptional activity is reduced about 50% in PTEN homozygous deletion cell lines. Interestingly, p53 may also act as a failsafe in PTEN-deficient tumors. In mouseprostate cells, conditional inactivation of Trp53,the mouseallele of p53, fails to produce transformation whereas complete PTEN inaction triggers non-lethal invasive prostate cancer (Chen et al., 2005). When PTEN deletion is combined with p53 deletion, cellular transformation occurs in a much shorter time frame and eventually leads to lethality. In PTEN null cells, Trp53 is responsible for the upregulation of cell cycle arrest regulator p21, and senescence marker plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) (Chen et al., 2005). This prevents proliferation and subsequently transformation into prostate cancer. Taken together, these findings suggest that p53-mediated senescence is responsible for restricting cell growth after PTEN loss.

16 |. NUCLEAR FUNCTIONS OF AKT/PKB KINASE ARE IMPORTANT

As mentioned previously, PTEN can regulate gene expression indirectly via regulation of its downstream targets. AKT (also known as protein kinase B), a serine/threonine-specific kinase that is important in proliferation and cell survival, is an important indirect target of PTEN (Kandel et al., 2002). AKT contains a Pleckstrin Homology (PH) domain, which binds to phosphoinositides with high affinity, in particular PIP2 and PIP3. AKT activationat the membraneis dependent on recruitment to PIP3, a phospholipid that is cleaved by PTEN to form PIP2. AKT is normally activated by growth factors that stimulate phosphoinositol-3-kinase (PI3K), the upstream regulator of AKT. Activators of AKT are often up-regulated in human cancers while AKT antagonists, such as PTEN and SHIP are usually lost or inactivated (Kandel et al., 2002). One of the most important effects of AKT on gene expression is its role in the repression of the E-cadherin gene, CDH1 (Grille et al., 2003). As described earlier, AKT activation can be regulated by PIP4Kβ, reduced expression of which also leads to loss of E-cadherin in the cell. In fact, several signal transductions pathways converge on AKT to repress E-cadherin transcription, including pathways involving growth factor Cripto-1, hyaluronan, and M-Ras (Larue & Bellacosa, 2005). While the exact mechanism of AKT-mediated repression of CDH1 transcription is still not well understood, cells that produce constitutively active AKT alsoinduceproductionofthetranscriptionfactor,SNAIL,whichbindsat the CDH1 promoter repressing E-cadherin expression (Nieto, 2002). Loss of E-cadherin expression leads to loss of cell–cell adhesion and increase in cellular motility.

17 |. NUCLEAR PHOSPHOINOSITIDES REGULATE ALY

AKT also plays a role in the export of mature messenger RNAs to the cytoplasm for translation. Nuclear phosphoinositides associate with pre-mRNA splicing machinery and are enriched in nuclear speckles (Boronenkov, Loijens, Umeda, & Anderson, 1998). Nuclear speckles are sub-nuclear structures rich in splicing factors and poly adenylating polymerases, enzymes responsible for some of the post-transcriptional modifications of mRNAs (Lamond & Spector, 2003). ALY, a nuclear speckle protein thought to be recruited during splicing of mRNAs to facilitate export from the nucleus, is a physiological substrate of AKT kinase, and is also altered in a wide variety of tumor samples (Domínguz-Sánchez, Sáez, Japón, Aquilera, & Luna, 2011; Okada, Jang, & Ye, 2008). ALY binds strongly with PIP3 and PIP2 when purified from HEK293T cell extracts, and addition of PI3K inhibitors reduces this interaction as well as diminishes its nuclear localization (Wickramasinghe et al., 2013). Nuclear PI3K signaling also regulates the cell proliferation and mRNA export activities of ALY. While AKT phosphorylation of ALY does not affect ALY sub-nuclear residency, phosphorylation at the T219 residue enhances mRNA export and the lack of phosphorylation markedly diminishes export. ALY mutants that can neither bind PIP3 nor be phosphorylated by AKT show a large decrease in cell proliferation. Interestingly AKT is also activated by IPMK (Resnick et al., 2005) and IPMK also regulates ALY biological activity (Wickramasinghe et al., 2013).

18 |. IPMK ANTAGONIZES A PHOSPHATASE-DEPENDENT AND p110-INDEPEDENT FUNCTION OF NUCLEAR PTEN

IPMK is an inositol and PIP2-kinase essential for the synthesis IP4 (both Ins(1,3,4,5)P4 and Ins(1,4,5,6)P4)IP5 as well as other highly phosphorylated inositol phosphate (IP)species and has a significant presence in the nucleus (Abel, Anderson, & Shears, 2001; Frederick et al., 2005). When IPMK is down-regulated, the synthesis of the majority of inositol pentakisphosphate, hexakisphosphate, and pyrophosphate species is disrupted, suggesting that IPMK is necessary for generating all highly phosphorylated inositol phosphate species (Powis et al., 1994). Although IPMK is not structurally related to the p110 phosphoinositol-3-kinases and is not inhibited by Wortmannin, IPMK is responsible for generating a substantial amount of nuclear PIP3 in the cell. It is likely that IPMK is regulated by wortmannin-sensitive PI3Ks through an uncharted signaling network, as Wortmannin treatment reduces the PI3K activity of IPMK. Further, broad-spectrum protein dephosphorylation of IPMK purified from HEK293T cells also inhibits IPMK activity (Maag et al., 2011), suggesting that IPMK is a phospho-protein somehow regulated downstream of classic PI3-kinase signaling pathways.

19 |. IPMK AFFECTS CHROMATIN REMODELING

IPMK appears to play a part in almost every facet of gene expression including histone modification, transcriptional regulation at the site of nuclear receptors and mRNA export (Figure 5). At the level of histone regulation, IPMK is essential for the metabolism of Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 which is a critical mediator of co-molecular components of the HDAC3-bound SMRT-DAD complex (Santiago & Esteller, 2007).

FIGURE 5.

IPMK is involved in gene expression. (a) IPMK enhances p300 acetylation of p53, stabilizing the tumor suppressor and thus subsequent p53-targeted gene expression. (b) IPMK product inositol (1,4,5,6) phosphate is necessary for association of histone deacetylase HDAC3 with the SMRT complex resulting in transcriptional repression of proliferation genes at the site of nucleosomes. (c) IPMK has thus far been identified as the only lipid-modifying enzyme that can phosphorylate PIP2 within a nuclear receptor resulting in transcriptional activation, effects of which appear to be countered by phosphatase PTEN, and critical in the process of development

Histone deacetylases (HDAC) play an essential role in histone modification and thus chromatin remodeling, as well as being potent tumor suppressors and targets for new therapeutics (Godman et al., 2008). The non-canonical histone deacetylase complex 3 (HDAC3) is overexpressed in many colon adenocarcinomas (Wang, Zang, et al., 2008).When HDAC3 is lost orpoorly expressed incancers, acetylation at lysine 12 on histone 4 (H4K12ac) increases, a modification that is associated with active promoters-particularly of proliferation and growth genes, and is highly present in proliferating cells (Codina et al., 2005; Wang, Zang, et al., 2008).

HDAC3 is an inactive enzyme by itself but is recruited to promoters and activated by the DAD(deacetylase activation domain) component of the SMRT complex (silencing mediator for retinoid or thyroid hormone receptor (Burton, Azevedo, Andreassi, Riccio, & Saiardi, 2013). The inositol phosphate Ins(1,4,5,6)P4 (IP4) is required for interaction between HDAC3 and DAD and thus assembly of the SMRT complex (Santiago & Esteller, 2007; Watson et al., 2012). Among inositol phosphates,IP4 is likely the physiological ligand as it is so tightly bound to the SMRT-DAD complex that it is retained through stringent purification. The presence of the phospholipid is critical for the enzymatic activity of the HDAC3-SMRT complex in repressing proliferation genes. It is likely that IPMK regulates other highly phosphorylated species associated with histones and is likely a useful target for therapeutic inhibition (Millard et al., 2013; Watson et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2013).

20 |. IPMK CAN ACTIVATE GENE EXPRESSION

IPMK also regulates gene expression in a kinase-independent manner via its function as an adaptor protein in transcriptional co-activation complexes. IPMK co-localizes with p53 at p53-target promoters (PUMA, Bax, and p21) in human colon cancer and osteosarcoma cells undergoing apoptosis, and can increase transcript abundance regardless of its catalytic activity (Sei et al., 2015). IPMK also appears to enhance p53-mediated transcription by stimulating the acetylation of p53 through enhancement of co-activator p300, loss of IPMK results in greatly reduced recruitment of p300 to target promoters Lack of catalytic IPMK in cancer patients with defective p53 transcriptional programming have been observed to harbor catalytically inactive IPMK. Truncated IPMK lacking both nuclear localization signal and kinase domain is present in the B lymphoblasts of patients with sporadic small intestinal carcinoids; these patients showing deregulation of p53 activity in the nucleus suggest that lack of functioning nuclear IPMK affects p53-transcription of apoptosis and cell-cycle arrest (Maacke, Opitz, et al., 2000).

21 |. IPMK REGULATES RAD51

At the level of mRNA export, IPMK appears to be necessary for recognition of mRNA transcripts necessary for maintaining genomic stability. RAD51 is an essential DNA repair protein involved in homologous recombination, and is commonly overexpressed in multiple cancers, in particular breast cancers showing loss of BRCA1 and BRCA2 alleles (Barbano et al., 2011; Jadav, Chanduri, Sengupta, & Bhandari, 2013; Maacke, Jost, et al., 2000; Martin et al., 2007; Mitra et al., 2009; Prakash et al., 2015; Wickramasinghe et al., 2013). When IPMK is depleted or catalytically inactivated in human cells there is a reduction in the nuclear export of polyadenylated mRNA transcripts that encode essential homologous recombination factors such as RAD51, CHK1, or FANCD2 but not those factors encoding for nonhomologous-end-joining, which is a more error-prone method of DNA repair (Strahl & Allis, 2000). The mRNA export recognition factor ALY binds RAD51 transcripts at a particular sequence in their 5' untranslated region, and this recognition is restored upon incubation with synthetic PIP3 indicating that it is the PI3K activity of IPMK that is necessary for this specific recognition.

As evidenced by the example of IPMK in chromatin remodeling and mRNA export, phospholipids act as essential mediators of protein-protein interactions as well as DNA-protein, and mRNA-protein interactions. While nuclear receptor-bound phospholipid modification and regulation is one of the most direct means that phospholipid-modifying enzymes affect gene expression, phospholipid-signaling enzymes also regulate levels and the phosphorylation status of phospholipids essential for histone-modification and chromatin remodeling enzyme complexes. Many of the chromatin-remodeling proteins regulated by phospholipids and phospholipid-modifying enzymes have been recognized as bona fide tumor suppressors.

22 |. PHOSPHOLIPID-BINDING HISTONE MODIFIERS CAN INHIBIT CELLULAR GROWTH

Members of the ING family associate with enzyme complexes in histone modification and several of these members have been identified as tumor suppressors. ING co-regulators are found associated primarily with histone acetyltransferase (HATs) and deacetylases (HDACs). Acetylation of histones is thought to reduce the positive charge on lysine residues in the histone tail thereby decreasing the affinity of histones for negatively charged DNA (Kelly & Cowley, 2013). This“loosens” the chromatin making it more available for binding by transcriptional cofactors and machinery, thus acetylated chromatin is associated with active transcription, and deacetylation of histones is associated with transcriptional repression. HDACs alone have little substrate specificity and as such rely on co-factors in large complexes to confer specificity (Hayakawa & Nakayama, 2010). One of these complexes is the Sin3a histone deacetylase complex which plays a critical role in development (Pile, Spellman, Katzenberger, & Wassarman, 2003). Sin3a is thought to act like a scaffold onto which the deacetylase RPD3 binds, although neither of these two subunits are capable of DNA recognition within the HDAC1 complex (Wagner, Hackanson, Lübbert, & Jung, 2010). Members of the ING family aid in localization of such HDAC complexes. Histone deacetylases display aberrant activity in numerous tumors, and HDAC inhibitors have recently been promoted as possible therapeutics (Feng, Hara, & Riabowol, 2002; Marks & Brewlow, 2007; Nebbioso, Carafa, Benedetti, & Altucci, 2012; Qiu et al., 2013).

23 |. THE ING PHD DOMAIN MEDIATES NUCLEAR PHOSPHOINOSITIDE INTERACTIONS

Members of the ING family of nuclear proteins utilize phospholipids to aid in localization at chromatin. All members of the ING family, which include ING1-ING5 contain a highly conserved Plant Homeodomain (PHD) finger that is found in many chromatin regulatory proteins including CBP/p300 acetyltransferase proteins, ACF chromatin remodeling protein, and the other ING family of putative tumor suppressor proteins (Fyodorov & Kadonaga, 2002; He, Helbing, Wagner, Sensen, & Riabowal, 2005; Kalkhoven, Teunissen, Houweling, Verrijzer, & Zantema, 2002). ING1 and ING2 in particular have varying basic residues in their PHD domains, which grants them specificity for different phosphoinositides. While both ING1 and ING2 interact with phospholipids through acommon polybasicdomain made up of lysine and arginine residues in the PHD finger, ING2 shows the strongest affinity for bioactive nuclear phosphoinositides (Shimada, Saito, Suzuki, Takashi, & Horie, 1998; Tallen & Riabowal, 2014). ING2 was identified in a candidate tumor suppressor screen because it shared considerable homology with known tumor-suppressor ING1 (Kumamoto et al., 2009). Since then ING2 has been found to be up-regulated in colon cancer, has loss of heterozygosity in basal cell carcinomas, head and neck squamous cell carcinomas and in hepatocellular carcinomas (Borkosky et al., 2009; Sironi et al., 2004; Ythier et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2010). While no mutation in ING2 has been observed in tumors, loss of expression at the mRNA level has been observed (Doyon et al., 2006).

24 |. NUCLEAR PHOSPHOLIPIDS ARE ESSENTIAL FOR PROPER LOCALIZATION OF HISTONE MODIFICATION ENZYMES

ING2 functions as a core component of the chromatin remodeling complex Sin3a-HDAC1 (Gozani et al., 2003). ING2 was identified as a phosphoinositide-binding candidate in a PIP-affinity resin screen, with highest specificity for phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate (PI5P) (Shi et al., 2006). Three basic lysine residues (K49, K51, K53) in the PHD domain of ING2 mediate phosphoinositide interaction, and mutation of these residues reduces binding to PI5P by over eightfold. When levels of PI5P are down-regulated by overexpression of the II beta isoform of the PI4-kinase (PI4K2β), ING2 signal becomes weaker in the nucleus and stronger in the cytoplasm. Also, ING2 no longer remains tightly bound to the nuclear matrix fraction in detergent-treated fractions of HT1080 cells indicating that interaction with the phospholipid helps localize ING2 subunits to the nucleus (Shi et al., 2006). When the bacterial enzyme Phospholipid Phosphatase IpgD is expressed at the plasma membrane, it can dephosphorylate plasma membrane bound PI(4,5)P2 to produce PI5P. Ectopically expressed IpgD induces specific recruitment of ING2 to the membrane, further strengthening the argument that PI5P is necessary for ING2 membrane localization (Bua, Martin, Binda, & Gozani, 2013).

Besides recruitment to chromatin via interaction with PIP2, ING2 has also shown specific binding activity to tri-methylated lysine 4 of histone 3 in nucleosomes (H3K4me3), a modification associated with active gene transcription. The phospholipid-binding activity of the PHD domain is not involved in ING2 binding to H3K4me3, instead the binding is mediated by aspartate 230 (D230) in the PHD domain (Peña et al., 2006). It is possible that these two different interactions within the same domain work as part of a mechanism by which PI5P aids in localization of ING2 and then disengages to allow for the subunit to bind at methylated lysines within chromatin. This interaction appears necessary to stabilize the ING2/mSin3a-HDAC1 complex at the promoters of proliferation genes (Shi & Gozani, 2005). This results in transcriptional repression of such critical cell-cycle regulators as cyclin D1 (Nagashima et al., 2001). Chromatin immunoprecipitation hybridized to microarray (ChIP-chip) analyses show that ING2 has low occupancy in nucleosome-poor transcriptional start sites (TSS) (Peña et al., 2006). This is consistent with ING2 being recruited to active chromatin via interaction between its PHD domain and H3K4me3, and then interaction with co-regulator PI5P which can then recruit HDAC complexes. This bridging interaction suggests that ING2 is useful in acute transcriptional repression responses.

25 |. PLANT HOMEODOMAINS CAN MEDIATE NUCLEAR PIP2 FUNCTIONS

This phospholipid binding function of the PHD finger also appears to be critical for p53 acetylation and subsequently p53-dependent induction of apoptosis gene expression programming. Previous studies report that ING2 overexpression stimulates acetylation of p53 at lysine 382 and then subsequently induces apoptosis (Clarke et al., 2001). Cells over-expressing wild-type ING2 increase acetylation levels of p53, as well as up-regulate p53-response gene p21, but mutant ING2 lacking the phospholipid-binding residues in its PHD domain lacks all of these effects (Shi et al., 2006). The acetylation and activation of p53 during UV response as well as the recruitment to actively transcribed chromatin may indicate that ING2 is involved in acute transcriptional repression during p53-mediated DNA damage response. Thus, PHD domains may be critical mediators of nuclear PIP3 functions.

26 |. TAF3 CAN DIRECTLY TRANSDUCE CHANGES IN NUCLEAR PHOSPHOINOSITIDE SIGNALING TO CHANGES IN GENE EXPRESSION

Using a discovery-based phosphoinositide interaction screen, Stijf-Bultsma et al. (2015) found that the PHD finger of the basal transcription factor TAF3 can interact with phosphoinositides, and can read out nuclear PI5P signaling. Phosphoinositide binding to TAF3 licenses interaction of TAF3 with a histone modification associated with activated transcription (K3K4me3), demonstrating that nuclear phosphoinositide signaling directly participates in fundamental aspects of gene regulation. This discovery firmly plants the flag of nuclear phosphoinositide signaling in the realm of chromatin biology and regulation, leading to brand new questions about how phosphoinositide signaling can affect epigenetics, differentiation, and other fundamental aspects of cellular physiology.

27 |. NUCLEAR PIP4K CAN ACTIVATE TRANSCRIPTION

Beyond interactions with ING2 and TAF3, PI5P is important within a number of signaling pathways. Levels of nuclear phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate (PI5P) increase throughout the cell cycle, and are modulated by the phosphatidylinositol-4-kinase (PIP4K) family of enzymes (Bunce, Boronenkov, & Anderson, 2008; Jones, Foulger, Keune, Bultsma, & Divecha, 2013). PIP4K converts PI5P to phosphatidylinositol-4,5-phosphate (PIP2), an important signaling molecule in both the cytosol and nucleus (Ciruela, Hinchliffe, Divecha, & Irvine, 2000; Fiume et al., 2015). The three isoforms of PIP4K are differentially localized in cells, with α and γ in the cytoplasm and β traversing both cytoplasm and nucleus (Han, Lee, Bibbs, & Ulevitch, 1994). Inhibition of PIP4Kβ results in an increase in PI5P levels, particularly during UV, topoisomerase II inhibitor etopiside treatment and oxidative damage stresses. This inhibition is mediated by phosphorylation of PIP4Kβ at Ser326 by p38, a mitogen activated protein kinase that is responsive in various cellular stresses (Baum & Georgiou, 2011; Jones et al., 2006). Overexpression of PIP4Kb results in a decrease of PI5P levels and subsequent decrease in ING2 levels within the chromatin enriched fraction of HEK293 cells (Baum & Georgiou, 2011). Overexpression of PIP4Kβ also decreases occupancy of ING2 at targeted promoters such as putative oncogene CIP2A in HT1080 cells (Baum & Georgiou, 2011). These results imply that the role of PIP4Kβ positively regulating ING2-regulator PI5P is critical for repression of growth and proliferation at actively transcribed promoters during cellular stresses, thus solidifying its role as a tumor suppressor.

28 |. NUCLEAR PIP4K CAN REPRESS TRANSCRIPTION

While in the case of ING2 PIP4K activity has been found to regulate transcriptional repression, the inverse also is true for at least one important protein that helps prevent metastasis in tumors. Low expression of PIP4Kβ is correlated with low CDH1 expression and reduced patient survival in breast cancers. E-cadherin, encoded by CDH1, is an epithelial adhesion molecule that requires calcium to mediate cell–cell contact with neighboring cells, and the loss of E-cadherin is considered a hallmark of the epithelial to mesenchymal transition as part of the process of metastasis in transformation (Keune et al., 2013). In a study that analyzed 489 advanced breast tumor samples, low PIP4Kβ expression was strongly correlated with poor prognosis and showed significant correlation with histological grade, size, and expression of Ki676 (a gene implicated in cellular proliferation) (Baum & Georgiou, 2011). While PIP4Kβ can regulate AKT activation, a critical inhibitor of apoptosis with downstream effects on gene expression, AKT activation and downstream targets were not noticeably different in PIP4Kβ knockdown cells although basal mRNA levels of CDH1 were decreased (Keune et al., 2013). Still, a study in SW480-ADH cells indicates that VDR (Vitamin D receptor signaling) activation is required for transcriptional upregulation of E-cadherin by PIP4Kβ, and that PIP2 mediates the interaction (Kouchi et al., 2011; Gelato et al., 2014). These various results indicate that the effect of PIP4Kβ nuclear signaling on gene expression is complex and can work through various enzymatic mechanisms with various phospholipid co-regulators.

29 |. PI5P REGULATES OTHER PHD-DOMAIN CONTAINING HDAC CO-REGULATORS

Recently, it was discovered that PI5P interaction is required for the binding of Ubiquitin-like with PHD and RING finger domains 1 (UHRF1) to the tri-methylated lysine residue of histone 3 (H3K9me3) (Arita, Ariyoshi, Tochio, Nakamura, & Shirakawa, 2008). UHRF1 is a unique protein that appears to be involved in DNA replication and DNA repair, but also is associated with targeting HDACs to actively transcribed chromatin via interaction with phospholipids. UHRF1 is important for recruiting DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase-1 (DNMT-1) to copy methylation patterns to daughter strand DNA during replication (Avvakumov et al., 2008; Liu et al., 2013). It has been shown that UHRF1 interaction with either hemi-methylated CpGs or H3K9me3 modified histone proteins was sufficient to recruit DNMT-1 to replicating DNA (Mudbhary et al., 2009). UHRF1 has a number of domains including a PHD domain similar to other HDAC-associating proteins. The polybasic region of this PHD domain normally blocks access of the tandem tudor domain (TTD) of UHRF1 to H3K9me3. Binding of PI5P causes an allosteric conformational change allowing the interaction between the TTD and H3K9me3 to take place. Similar to ING2 and TAF3, the levels of PI5P are likely critical for these interactions. PI5P is most highly present during the G1 phase of the cell cycle, and is almost absent in proliferating nuclei, supporting the idea that PI5P aids in activating UHRF1 during DNA replication (Jones et al., 2013). This role may be one of the reasons why UHRF1 is up-regulated in hepatocellular carcinoma as well as breast, prostate, and lung cancer (Bronner, Fuhrmann, Chédin, Macaluso, & Deh-Paganon, 2010; Choi, Thapa, Tan, Hedman, & Anderson, 2015). Although the mechanism by which the ubiquitin ligase activity of the enzyme UHRF1 regulates DNA methylation at histone sites is not well understood, UHRF1 is essential and over-expression leads to genomic instability, DNA hypomethylation, and p53-mediated senescence in human cells (Arita et al., 2008).

30 |. NUCLEAR PIP2 MEDIATES THE INTERACTION BETWEEN BASP-1 AND WILMS' TUMOR 1 PROTEIN

Other nuclear phospholipids have also been associated with chromatin modification. Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) is the most abundant species among the known phosphoinositides, and is a substrate for phospholipases and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinases (PI3Ks) to generate other phospholipid messengers (Toska et al., 2012). BASP-1, a corepressor of Wilms’ Tumor 1 protein, the transcription factor found mutated in the most common cancer of the kidneys in children, requires association with PIP2 to associate with HDAC1 in the nucleus (Toska et al., 2012). This study was able to show that PIP2 associates with target promoters using chromatin immunoprecipitation. Although it is unclear how PIP2-BASP1 interaction drives association with HDAC1, PIP2 is likely present at the promoter regions of WT-1 target genes to elicit transcriptional repression, further implicating nuclear phosphoinositides in gene regulation and chromatin structure.

31 |. NUCLEAR SPHINGOSINE-1-PHOSPHATE INHIBITS HISTONE DEACETYLASES

Ceramide derivatives are another ubiquitous class of nuclear phospholipids involved in chromatin modification. One derivative of ceramide metabolism, sphingosine has been found to regulate histone acetylation. Levels of sphingosine-1-phosphate (S1P) are up-regulated in ovarian cancer patient ascites in epithelial ovarian cancer, one of the deadlier gynecologic diseases (Paris et al., 2002). Interestingly, S1P preserves fertility in UV-treated female mice without inducing genomic damage as measured by chromosome breaks or rearrangements, as well as protect human cells during UVB treatment. This suggests that S1P may be involved in genome maintenance functions (Hait et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2003; Wang, Zhao, et al., 2008). S1P inhibits the enzymatic activity of HDAC1 and HDAC2 in nuclear extracts (Spiegel & Mistien, 2007). A binding assay showed that active or inactive Sphingosine Kinase 2 (SphK2) bound specifically to histone H3, although expression assays showed that catalytically active SphK2 increased acetylation of lysine 9 of histone 3, lysine 5 of histone H4, and lysine 12 of H2B (Spiegel & Mistien, 2007). Addition of SphK2 products S1P or dihydro-S1P increased specific acetylation of all of those aforementioned histone residues but interestingly also acted as endogenous inhibitors of HDAC activity which in turn reduced p53 activation of protein p21. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis also showed that SphK2 associated with the proximal p21 promoter much like HDAC1 (Spiegel & Mistien, 2007). The role of S1P in histone modification is an example of how phospholipids can act to activate transcription and repress DNA damage response. More regulatory roles for sphingolipids are likely to be discovered, as ceramide-derived phospholipids are extremely abundant in the nuclear space. For instance, sphingomyelin, the most abundant nuclear sphingolipid, is found associated with chromatin assembly and has a substantial presence in the nuclear matrix (Mellman et al., 2008).

32 |. NUCLEAR PIP2 REGULATES STAR-PAP

Phospholipids mediate the interaction between enzymes and pre-mRNA transcripts for genome maintenance proteins. Posttranscriptional modification of mRNA is necessary for its stability as well as recognition for export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm for translation. One of these modifications is an addition of a string of adenosine nucleotides to the 3' end of mRNA transcripts. Recently a non-canonical polyadenylating polymerase (PAP) that performs this function was found to be regulated by PIP2 in the nucleus. Nuclear speckle targeted PIPKIa regulated-poly(A)polymerase (Star-PAP) couples with transcriptional machinery and requires PIP2 for recognition of specific mRNA transcripts (Laishram & Anderson, 2010). While StAR-PAP recruits common mRNA 3'-end processing factors that are also components of canonical PAP complexes, it has unique sequence targets at the 3'-end of transcripts that are not able to be recognized by other PAP complexes (Gonzales, Mellman, & Anderson, 2008; Laishram &Anderson,2010). PI3K signaling enzymes PIPKIα and PKCδ are part of the Star-PAP complex. PIPKIα is well-known to catalyze production of PIP2 while PKCδ regulates the initiation and processivity of Star-PAP activity (Didichenko & Thelen, 2001; Gonzales et al., 2008; Laishram & Anderson, 2010). PIPKIα, PIP2, and PI3K all assemble at nuclear speckles where mRNA processing factors localize, including Star-PAP(Li et al., 2012; Li & Anderson, 2014; Osborne, Thomas, Gschmeissner, & Schiavo, 2001). While PIP2 stimulates the activity of Star-PAP by over 10-fold, Star-PAP association with PIP2-producing enzyme PIPKIα, and DAG-regulating PKCδ is enhanced only in the presence of DNA damage. The mRNA transcripts modified by Star-PAP encode for anti-tumorigenic proteins such as BCL2-interacting killer (BIK) protein which activates the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway (Mekhail & Moazed, 2010). These results suggest that Star-PAP is critical for the expression ofanti-tumorigenictranscripts tothe cytoplasmintheevent of DNA damage. Interestingly, Star-PAP has been shown to control the HPV-virus-generated E6 protein, a component of the E3 ubiquitin-ligase E6-associated protein that aids in p53 degradation, and contributes to cervical cancer (Li & Anderson, 2014). Star-PAP is further activated by PIP2-derived diacylglycerol (DAG), however, this may not apply to all Star-PAP targets since DAG does not mediate all PIPKIα- and PKCδ-regulated Star-PAP activities (Mekhail & Moazed, 2010). This suggests that Star-PAP requires various different phospholipid co-regulators for targeting specific transcripts suggesting that it is involved in a finely tuned phospholipid-signaling pathway. While there is still much to discover about targets of the phosphoinositide-regulated Star-PAP, the requirements for both Star-PAP and PIPKIα in the expression of certain mRNAs provides a novel mechanism for nuclear PI signal transduction to regulate gene expression, which may play an important role in cancer.

The discovery that phosphoinositide kinases and their phospholipid substrates exist outside the nuclear membrane and in the nucleoplasm represented a fundamental shift in our understanding of nuclear events and cellular physiology (Cocco et al., 1987, 1988). Despite the large amount of data describing phospholipid-signaling enzymes in the cytoplasm at the plasma membrane, the nuclear functions of these molecules are poorly understood. The extensive work to develop inhibitors of PI3K signaling pathways to serve as anti-cancer therapeutics has focused on the cytoplasmic functions of these enzymes. However, an abundance of research suggests that phosphoinositide signaling enzymes and substrates may play equally important roles within the nucleus of cells, regulating gene expression via highly specific and modifiable phospholipid-enzyme interactions at the level of DNA and chromatin.

It is evident that changes in nuclear phosphoinositide levels can affect changes to the genome, including histone modification, transcription, RNA maturation and RNA export. These phospholipid-signaling pathways are complex, sometimes redundant and highly interwoven. For many essential cellular processes, phospholipid regulation is highly specific and can offer novel points for therapeutic interventions in human disease.

In spite of all the recent progress made in our understanding of nuclear lipid signaling, many questions remain. For instance, how are phosphoinositides trafficked within the nucleus, and how are the pools of phospholipids maintained and regulated? How do phospholipids reach nuclear receptors? Can phospholipid-signaling enzymes modify nucleoprotein/lipid complexes similarly in both nucleus and at membranes? Is there a “phospholipid code” that can be read by phospholipid interaction domains, providing novel mechanisms of transcriptional activation?

Although we have a much better understanding of how PIPs are involved in various aspects of gene expression, we do not understand how these signaling networks are coordinated. As more advanced tools to track and manipulate the flow of phospholipids within cells are developed, we will be better equipped to answer these intriguing questions.

Acknowledgments

Funding information

V Foundation for Cancer Research, V-Scholar Award V2016-015; National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases P30 DK020593; National Cancer Institute K01 CA172957; American Cancer Society IRG-58-009-56

REFERENCES

- Abel K, Anderson RA, & Shears SB (2001). Phosphatidylinositol and inositolphosphate metabolism. Journal of Cell Science, 114,2207–2208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albi E, Rossi G, Maraldi NM, Magni MV, Cataldi S, Solimando L, & Zini N (2003). Involvement of nuclear phosphatidylinositol-dependent phospolipases C in cell cycle progression during rat liver regeneration. Journal of Cellular Physiology, 197, 181–188. 10.1002/jcp.10292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alcázar-Román AR, Tran EJ, Guo S, & Wente SR (2006). Inositol hexakisphosphate and Gle1 activate the DEAD-box protein Dbp5 for nuclear mRNA export. Nature Cell Biology, 8(7), 711–716. 10.1038/ncb1427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amaya MJ, Oliveira AG, Guimaraes ES, Casteluber MC, Carvalho SM, Andrade LM, … Leite MF (2014). The insulin receptor translocates to the nucleus to regulate cell proliferation in liver. Hepatology, 59, 274–283. 10.1002/hep.26609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrade LM, Geraldo JM, Gonçalves OX, Leite MT, Catarina AM, Guimarães MM, … Leite MF (2012). Nucleoplasmic calcium buffering sensitizes human squamous cell carcinoma to anticancer therapy. Journal of Cancer Science & Therapy, 4, 131–139. 10.4172/1948-5956.1000127 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anuka E, Yivgi-Ohana N, Eimerl S, Garfinkel B, Melamed-Book N, Chepurkol E, … Orly J (2013). Infarct-induced steroidogenic acute regulatory protein: A survival role in cardiac fibroblasts. Molecular Endocrinology, 27(9), 1502–1517. 10.1210/me.2013-1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arita K, Ariyoshi M, Tochio H, Nakamura Y, & Shirakawa M (2008). Recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA protein UHRF1 by a base-flipping mechanism. Nature, 455, 818–821. 10.1038/nature07249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong EH,Goswami D,Griffin PR, Noy N, & Ortlund EA(2014). Structural basis for ligand regulation of the fatty acid-binding protein 5, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor β/δ (FABP5-PPARβ/δ) signaling pathway. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 289(21), 14941–14954. 10.1074/jbc.M113.514646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auger KR, Serunian LA, Soltoff SP, Libby P, & Cantley LC (1989). PDGF-dependent tyrosine phosphorylation stimulates production of novel polyphosphoinositides in intact cells. Cell, 57(1), 167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvakumov GV, Walker JR, Xue S, Li Y, Duan S, Bronner C, … Dhe-Paganon S (2008). Structural basis for recognition of hemi-methylated DNA by the SRA domain of human UHRF1. Nature, 455, 822–825. 10.1038/nature07273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bading H, Hardingham GE, Johnson CM, & Chawla S (1997). Gene regulation by nuclear and cytoplasmic calcium signals. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 236(3), 541–543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baenke F, Peck B, Miess H, & Schulze A (2013). Hooked on fat: The role of lipid synthesis in cancer metabolism and tumour development. Disease Model Mechanisms, 6(6), 1353–1363. 10.1242/dmm.011338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbano R, Copetti M, Perrone G, Pazienza V, Muscarella LA, Balsamo T, … Parrella P (2011). High RAD51 mRNA expression characterize estrogen receptor-positive/progesteron receptor-negative breast cancer and is associated with patient’s outcome. International Journal of Cancer, 129(3), 536–545. 10.1002/ijc.25736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlev NA, Liu L, Chehab NH, Mansfield K, Harris KG, Halzonetis TD, & Berger SL (2001). Acetylation of p53 activates transcription through recruitment of coactivators/histone acetyltransferases. Molecular Cell, 8, 1243–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow CA, Laishram RS, & Anderson RA (2010). Nuclear phosphoinositides: A signaling enigma wrapped in a compartmental conundrum. Trends in Cell Biology, 20(1), 25–35. 10.1016/j.tcb.2009.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum B, & Georgiou M (2011). Dynamics of adherens junctions in epithelial establishment, maintenance, and remodeling. Cell Biology, 192, 907–917. 10.1083/jcb.201009141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit G, Cooney A, Giguere V, Ingraham H, Lazar M, Muscat G,… Laudet, V. (2006). International union of pharmacology. LXVI. Orphan nuclear receptors. Pharmacological Reviews, 58(4), 798–836. 10.1124/pr.58.4.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berezney R, & Coffey DS (1974). Identification of a nuclear protein matrix. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 60(4), 1410–1417. https://doi.org/0006-291X(74)90355-6(pii) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertagnolo V, Benedusi M, Querzoli P, Pedriali M, Magri E, Brugnoli F, & Capitani S (2006). PLC-b2 is highly expressed in breast cancer and is associated with a poor outcome: A study on tissue microarrays. International Journal of Oncology, 28(4), 863–872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blind RD, Suzawa M, & Ingraham HA (2012). Direct modification and activation of a nuclear receptor-PIP2 complex by the inositol lipid kinase IPMK. Science Signaling, 19(5), ra44 10.1126/scisignal.2003111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blind RD (2014). Disentangling biological signaling networks by dynamic coupling of signaling lipids to modifying enzymes. Advances in Biological Regulation, 54,25–38. 10.1016/j.jbior.2013.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borkosky SS,Gunduz M,Nagatsuka H,Beder LB,Gunduz E,Ali MA, …Nagai,N.(2009).FrequentdeletionofING2locusat4q35.1associates with advanced tumor stage in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology, 135(5), 703–713. 10.1007/s00432-008-0507-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boronenkov IV, Loijens JC, Umeda M, & Anderson RA (1998). Phosphinositide signaling pathways in nuclei are associated with nuclear speckles containing pre-mRNA splicing factors. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 9(12), 3547–3560. 10.1091/mbc.9.12.3547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronner C, Fuhrmann G, Chédin FL, Macaluso M, & Deh-Paganon S (2010). UHRF1 links the histone code and DNA methylation to ensure faithful epigenetic memory inheritance. Genetics Epigent, 2009,29–36. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bua DJ, Martin GM, Binda O, & Gozani O (2013). Nuclear phosphatidylinositol-5-phosphate regulates ING2 stability at discrete chromatin targets in response to DNA damage. Scientific Reports, 3:2137 10.1038/srep02137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce MW, Bergendahl K, & Anderson RA (2006). Nuclear PI(4,5)P2: A new place for an old signal. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1761, 560–569. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2006.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunce MW, Boronenkov IV, & Anderson RA (2008). Coordinated activation of the nuclear ubiquitin ligase Cul3-SPOP by the generation of phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 283(13), 8678–8686. 10.1074/jbc.M710222200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burris TP, Solt LA, Wang Y, Crumbley C, Banerjee S, Griffett K,… Kojetin DJ (2013). Nuclear receptors and their selective pharmacologic modulators. Pharmacological Reviews, 65, 710–778. 10.1124/pr.112.006833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton A, Azevedo C, Andreassi C, Riccio A, & Saiardi A (2013). Inositol pyrophosphates regulate JMJD2C-dependent histone demethylation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 110(47), 18970–18975. 10.1073/pnas.1309699110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantello Barrie CC, Cawthorne MA, Haigh D, Hindley RM, Smith SA, & Thurlby PL (1994). The synthesis of BRL 49653—A novel and potent antihyperglycaemic agent. Bioorganic, 4(10), 1181–1184. 10.1016/S0960-894X(01)80325-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cascianelli G,Villani M, Tosti M,Marini F, Bartoccini E, Magni MV, & Albi E (2008). Lipid microdomains in cell nucleus. Molecular Biology of the Cell, 19(12), 5289–5295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chalhoub N, & Baker SJ (2009). PTEN and the PI3-kinase pathway in cancer. Annual Review of Pathology, 4, 127–150. 10.1146/annurev.pathol.4.110807.092311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C-J, Mulholland DJ, Valamehr B, Mosessian S, Sellers WR, & Wu H (2008). PTEN nuclear localization is regulated by oxidative stress and mediates p53-dependent tumor suppression. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 28(10), 3281–3289. 10.1128/MCB00310-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Z, Trotman LC, Shaffer D, Lin HK, Dotan ZA, Niki M, … Pandolfi PP (2005). Crucial role of p53-dependent cellular senescence in suppression of Pten-deficient tumorigenesis. Nature, 436(4), 725–730. 10.1038/nature03918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng MK, & Shearn A (2004). The direct interaction between ASH2, a Drosophila trithorax group protein, and SKTL, a nuclear phosphatidylinositol 4-phosphate 5-kinase, implies a role for phosphatidylinositol 4, 5-bisphosphate in maintaining transcriptionally active chromatin. Genetics, 167(3), 1213–1223. 10.1534/genetics.103.018721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi S, Thapa N, Tan X, Hedman AC, & Anderson RA (2015). PIP kinases define PI4,5P2 signaling specificity by association with effectors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1851(6), 711–723. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JH, & Eng C (2005). Nuclear-cytoplasmic partitioning of phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 (PTEN) differentially regulates the cell cycle and apoptosis. Cancer Research, 65, 8096–8100. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciruela A, Hinchliffe KA, Divecha N, & Irvine RF (2000). Nuclear targeting of the beta isoform of type II phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (phosphatidylinositol 5-phosphate 4-kinase) by its alpha-elx 7. Biochemical Journal 346(Part 3), 587–591. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke JH, Letcher AJ, D’santos CS, Halstead JR, Irvine RF, & Divecha N (2001). Inositol lipids are regulated during cell cycle progression in the nuclei of murine erthyroleukaemia cells. Biochemical Journal, 357(Pt 3), 905–910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco L, Gilmour RS, Ognibene A, Letcher AJ, Manzoli FA, & Irvine RF (1987). Synthesis of polyphosphoinositides in nuclei of Friend cells. Evidence for polyphosphoinositide metabolism inside the nucleus which changes with cell differentiation. Biochemical Journal, 248(3), 765–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocco L, Martelli AM, Gilmour RS, Ognibene A, Manzoli FA, & Irvine RF (1988). Rapid changes in phospholipid metabolism in the nuclei of Swiss 3T3 cells induced by treatment of the cells with insulinlike growth factor I. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 154(3), 1266–1272. https://doi.org/0006-291X(88)90276-8(pii) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codina A, Love JD, Li Y, Lazar MA, Neuhaus D, & Schwabe JW (2005). Structural insights into the interaction and acitvatin of histone deacetylase 3 by nuclear receptor corepressors. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102, 6009–6014. 10.1073/pnas.0500299102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsen SA, Cekaite L, Ågesen TH, Sveen A, Nesbakken A, Thiis-Evensen E, … Lothe RA (2011). Phospholipase C isozymes are deregulated in colorectal cancer—Insights gained from gene set enrichment analysis of the transcriptome. Public Library of Science, 6(9), e24419 10.1371/journal.pone.0024419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristofano A, & Pandolfi PP (2000). The multiple roles of PTEN in tumor suppression. Cell, 100, 387–390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Didichenko SA, & Thelen M (2001). Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase c2alpha contains a nuclear localization sequence and associates with nuclear speckles. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276(51), 48135–48142. 10.1074/jbc.M104610200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieck CB, Wood A, Brglez I, Rojas-Pierce M, & Boss WF (2012). Increasing phosphatidylinositol (4,5) bisphosphate biosynthesis affects plant nuclear lipids and nuclear functions. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry, 57, 32–44. 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domínguz-Sánchez MS, Sáez C, Japón MA, Aquilera A, & Luna R (2011). Differential expression of THOC1 and ALY mRNP biogenesis/ export factors in human cancers. BMC Cancer 11:77 10.1186/1471-2407-11-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyon Y, Cayrou C, Ullah M, Landry AJ, Côté V, Selleck W, …Côté J (2006). ING tumor suppressor proteins are critical regulators of chromatin acetylation required for genome expression and perpetuation. Molecular Cell, 21(1), 51–64. 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drobak BK, & Heras B (2002). Nuclear phosphoinositides could bring FYVE alive. Trends in Plant Science, 7(3), 132–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eitel JA, Bijangi-Vishehsaraei K, Saadatzadeh MR, Bhavsar JR, Murphy MP, Pollok KE, & Mayo LD (2009). PTEN and p53 are required for hypoxia induced expression of maspin in glioblastoma cells. Cell Cycle, 8(6), 896–901. 10.4161/cc.8.6.7899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinosa JM, & Emerson BM (2001). Transcriptional regulation by p53 through intrinsic DNA/chromatin binding and site-directed cofactor recruitment. Molecular Cell, 8,57–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faenza I, Matteucci A, Manzoli L, Billi AM, Aluigi M, Peruzzi D,… Cocco L (2000). A role for nuclear phospholipase Cb 1 in cell cycle control. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 275, 30520–30524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faenza I, Matteucci A, Bavelloni A, Marmiroli S, Martelli AM, Gilmour RS,… Cocco L (2002). Nuclear PLCbeta (I) acts as a negative regulator of p45/NF-E2 expression levels in Friend erythroleukemia cells. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, 1589, 305–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng X, Hara Y, & Riabowol K (2002). Different HATS of the ING1 gene family. Trends in Cell Biology, 12, 532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiume R, Stijf-Bultsma Y, Shah ZH, Keune WJ, Jones DR, Jude JG, & Divecha N (2015). PIP4K and the role of nuclear phosphoinositides in tumour suppression. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids, 1851(6), 898–910. 10.1016/j.bbalip.2015.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frederick JP, Mattiske D, Wofford JA, Megosh LC, Drake LY, Chiou S-T,… York JD (2005). An essential role for inositol polyphosphate multikinase Ipk2, in mouse embryogenesis and second messenger production. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 102(24), 8454–8459. 10.1073/pnas.0503706102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman DJ, Li AG, Wei G, Li HH, Kertesz N, Lesche R,…Wu H (2003). PTEN tumour suppressor regulates p53 protein levels and activity through phosphatase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cancer Cell, 3, 117–130. 10.1016/S1535-6108(03)00021-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritz V, & Fajas L (2010). Metabolism and proliferation share common regulatory pathways in cancer cells. Oncogene, 29(31), 4369–4377. 10.1038/onc.2010.182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fyodorov DV, & Kadonaga JT (2002). Binding of Acf1 to DNA involves a WAC motif and is important for ACF-mediated chromatin assembly. Molecular and Cellular Biology, 22, 6344–6353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galdieri L, Chang J, Mehrotra S, & Vancura A (2013). Yeast phospholipase C is required for normal acetyl-CoA homeostasis and global histone acetylation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 288(39), 27986–27998. 10.1074/jbc.M113.492348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Gil M, & Albi E (2017). Nuclear lipids in the nervous system: What they do in health and disease. Neurochemical Research, 42(2), 321–336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelato KA, Tauber M, Ong MS, Winter S, Hiragami-Hamada K, Sindlinger J, … Fischle W (2014). Accessibility of different histone H3-binding domains of UHRF1 is allosterically regulated by phosphatidylinositol 5-Phosphate. Molecular Cell, 54, 905–919. 10.1016/j.molcel.2014.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginn-Pease ME, & Eng C (2003). Increased nuclear phosphatase and tensin homologue deleted on chromosome 10 is associated with G0-G1 in MCF-7 cells. Cancer Research, 63(2), 282–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godman CA, Joshi R, Tierney BR, Greenspan E, Rasmussen TP, Wang H-W, … Giardina C (2008). HDAC3 impacts multiple oncogenic pathways in colon cancer cells with effects on Wnt and vitamin D signaling. Cancer Biology & Therapy, 7(10), 1570–1580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]