Abstract

Background

Outcomes instruments are used to measure patients’ subjective assessment of health status. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global-10 was developed to be a concise yet comprehensive instrument that provides physical and mental health scores and an estimated EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) score.

Methods

A total of 175 prospectively enrolled patients with shoulder instability completed the PROMIS Global-10, EQ-5D, American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES), Single Assessment Numeric Evaluation (SANE), and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index. Spearman correlations between PROMIS scores and the legacy instruments were calculated. Bland–Altman analysis assessed agreement between estimated and actual EQ-5D scores. Floor and ceiling effects were recorded.

Results

Correlation between actual and estimated EQ-5D was excellent-good (0.64/p < 0.0005), but Bland–Altman agreement revealed high variability for estimated EQ-5D scores (95% CI: −0.30 to +0.34). Correlation of PROMIS physical scores was excellent-good with ASES (0.69/p < 0.0005), good with SANE (0.43/p<0.0005), and poor with WOSI (0.17/p = 0.13). Correlation between PROMIS mental scores and all legacy instruments was poor.

Conclusions

PROMIS Global-10 physical function scores show high correlation with ASES but poor correlation with other legacy instruments, suggesting it is an unreliable outcomes instrument in populations with shoulder instability. The PROMIS Global-10 cannot replace actual EQ-5D scores for cost-effectiveness assessment in this population.

Level of evidence

Level II, study of diagnostic test.

Keywords: PROMIS Global-10, ASES, EQ-5D, SANE, WOSI, patient-reported outcome measures, shoulder instability, performance, validation

Introduction

Patient-reported outcomes (PROs) are commonly utilized in orthopedic practices, in part as a result of the encouragement of their use by several international orthopedic societies and governing bodies.1–3 They are used to quantify disease burden,4 assess a patient’s response to medical treatment,5 and predict which patients make ideal surgical candidates.6 These measures are based solely on patient perception, and not on the assessment of a health care provider.7–11 There are numerous PROs available, including those that quantify general health and quality of life, such as the EQ-5D12 and the Short-Form 36 health survey (SF-36),13 those that quantify the effects of specific disorders, and those that quantify the function of specific anatomical sites. Shoulder function and subsequently, shoulder instability, is routinely assessed using “legacy” PROs14 such as the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons shoulder assessment form (ASES)15,16 and the Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI).17

Although it would be ideal to administer multiple PRO instruments to gain a comprehensive profile of a patient’s health, quality of life, and injury status, this remains difficult in a clinical setting due to the time-consuming nature of completing multiple lengthy questionnaires. Recently, clinicians have aimed to reduce the patient burden involved with PRO completion by utilizing fewer, more streamlined, and more efficient instruments without sacrificing accuracy and reliability of data collection.18,19 The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) was developed out of the “Roadmap for Medical Research” created by the United States’ National Institutes of Health (NIH) in 2002 as an concise and efficient set of PROs for use in multiple medical specialties.20,21 PROMIS consists of a variety of non-injury-specific PROs, allowing it to focus on improving the overall patient health and function, as opposed to targeting solely the effects of the injury or disease. This mandate is an agreement with the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health.22

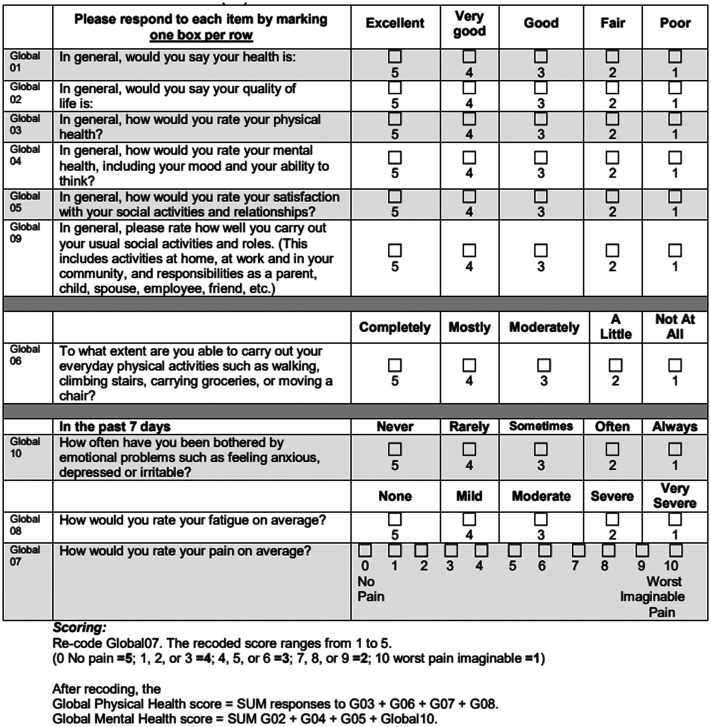

The PROMIS system consists of both extremity-specific and general health PROs. The PROMIS-Global 10 falls into the latter category and consists of 10 questions (Figure 1) that assess the general physical function as well as the social and emotional wellbeing.10,19,23 It outputs three distinct health status scores, including a physical health score, mental health score, as well as an estimated EQ-5D score.10,24,25 Its advantage over extremity-specific PROs such as the PROMIS upper extremity (UE), the ASES, and the WOSI include its shorter length and its potential to be used as a consistent outcome measurement tool for patients with a variety of diseases across many medical specialties. The use of a single validated global health PRO in place of multiple disease- or extremity-specific PROs would reduce patient burden while allowing standardization of data collection within an entire health system and multispecialty practices. For these reasons, the validation of the PROMIS Global-10 compared with legacy PRO instruments in a variety of patient subgroups is warranted.

Figure 1.

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global-10 form.

In patients with a diagnosis of shoulder instability, the PROMIS UE has previously been shown to have an excellent correlation with the SF-36 physical function (PF) (r = 0.79, p < 0.01) and ASES (r = 0.71, p < 0.01), while the PROMIS PF CAT showed an excellent correlation with SF-36 PF (r = 0.72, p < 0.01) and an excellent-good correlation with ASES (r = 0.67, p < 0.01).26 However, the PROMIS Global-10 has not been validated against these legacy shoulder specific and general health PROs in shoulder instability patients.

The purpose of this study is to validate the PROMIS Global-10 PRO compared with legacy general health (EQ-5D), extremity-specific (ASES, SANE) and disease-specific (WOSI) PROs for patients with a diagnosis of shoulder instability. We hypothesize that (1) there is good or better correlation (defined as a correlation coefficient ≥0.4) between the PROMIS Global-10 physical and mental health scores and legacy PROs (EQ-5D, SANE, WOSI), (2) there is good or better correlation and low variance between actual EQ-5D scores and estimated EQ-5D scores from the PROMIS Global-10, (3) and the PROMIS Global-10 will not show floor or ceiling effects.

Materials and methods

This study received Institutional Review Board approval (Protocol Number 1510016580) and was compliant with HIPAA protocols. Data were prospectively collected from January 2015 to October 2017 by two fellowship trained shoulder and elbow surgeons in outpatient, academic clinics. Inclusion criteria were English-speaking patients who were 14 years of age and older with a primary diagnosis of shoulder instability. Informed consent was obtained from all patients. For patients under 18 years, consent was also obtained from a parent or guardian who was present during the data collection. All patients had proven pathology and were incorporated to further delineate the universal applicability of the PROMIS 10 to patients with shoulder instability. A power analysis was performed a priori, determining 46 patients were needed to detect a correlation of 0.4 (good/moderate) between PRO instruments for a two-sided test and alpha level of 0.05.

A total of 175 patients meeting our inclusion criteria were enrolled. The participants prospectively completed the PROMIS Global-10, EQ-5D, Single Numeric Assessment Evaluation (SANE), and ASES in sequential order on an iPad tablet (Apple, Cupertino, CA, USA). The participants were also prospectively asked if they knew their diagnosis, and if they knew to have shoulder instability, then they completed the WOSI (i.e. these patients had previously received a diagnosis of shoulder instability; new patients who were yet to receive a diagnosis were therefore unable to complete this section). Demographic information, including age, gender, hand dominance, and affected side was collected. The patients were additionally asked to designate their recreational activity level on a five-point scale (minimally active, somewhat active, noncontact sports, contact sports, professional athlete), their work activity level on a four-point scale (light/sedentary, mildly strenuous, moderately strenuous, heavy/manual labor), and whether they participated in athletics involving overhead motion (baseball, football quarterback, tennis, cricket, volleyball, competitive swimming, etc.). All data were stored on REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture),27 a HIPAA compliant electronic database.

The PROMIS Global-10 provides physical and mental health raw scores, t-scores (derived from the raw scores and standardized such that the US general population mean is 50 and the standard deviation is 10), as well as an estimated EQ-5D score generated from the results of eight questions, as described by Revicki et al.24 To assess construct validity, raw scores and t-scores of the PROMIS Global-10 physical and mental health scores were correlated with results of the SANE, ASES, and WOSI using Spearman correlation coefficients. Correlations (p < 0.05) were defined as excellent (>0.7), excellent-good (0.61–0.70), good (0.4–0.6), or poor (<0.4), with an acceptable correlation defined as good or better (≥0.4) and achieving statistical significance (p < 0.05).26,28 Agreement and variation between the actual and estimated EQ-5D scores were compared using Spearman correlation coefficients and a Bland–Altman analysis. Subgroup analyses to determine correlations between the PROMIS Global-10 and legacy PROs and correlations between the estimated and actual EQ-5D were carried out for adequately powered subgroups (at least 46 patients) based on diagnosis (labral tear, n = 130) and activity level (athletes, n = 73, nonathletes, n = 102, overhead athletes, n = 48). Means of physical function score for the athlete and nonathlete subgroups were compared using an independent two-tailed t-test.

To test for the presence of floor and ceiling effects, the percentage of participants with the highest or lowest physical or mental scores possible was calculated. A floor or ceiling effect was considered present if >15% of patients had the highest or lowest score.29,30 Since younger patients tend to have fewer medical comorbidities and would be expected to score higher on measures of global physical and mental health, we sought to determine whether age effected the likelihood of receiving the maximum or minimum score by testing for floor and ceiling effects in stratified age brackets. Subgroup analysis was performed to test for floor and ceiling effects in all patient subgroups defined as less than 18 years old, 18–25 years old, 25–40 years old, and greater than 40 years old.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 25 software (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) with statistical significance set at p < 0.05, two-sided.

Results

A total of 175 patients were included in this study. Demographic information for all patients and for subgroups based on diagnosis, athletic involvement, and work activity level are reported in Table 1. PRO scores for all patients and for subgroups are reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

Demographics of patient population.

| Parameter | Total | Parameter | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Occupation | ||

| n (n missing) | 175 (0) | Heavy or manual labor | 20 (11.4%) |

| Mean (SD) | 41.8 (17.7) | Moderately strenuous work | 78 (44.6%) |

| Medan (range) | 41.7 (16–90) | Mildly strenuous work | 50 (28.6%) |

| Sex | Light or sedentary work | 27 (15.4%) | |

| Male | 113 (64.6%) | Shoulder | |

| Female | 62 (35.4%) | Right | 99 (56.6%) |

| Hand | Left | 71 (40.6%) | |

| Right | 146 (83.4%) | Both | 5 (2.8%) |

| Left | 18 (10.3%) | Labral tear | |

| Ambidextrous | 11 (6.3%) | Yes | 130 (74.2%) |

| Activity | No | 45 (25.8%) | |

| Professional athlete | 1 (0.6%) | Bankart fracture | |

| Contact sports | 30 (17.1%) | Yes | 11 (6.3%) |

| Noncontact sports | 42 (24.0%) | No | 164 (93.7%) |

| Somewhat active | 68 (38.9%) | Hill Sachs lesion | |

| Minimally active | 34 (19.4%) | Yes | 21 (12.0%) |

| Sports with overhead motion | No | 154 (88.0%) | |

| Yes, Professional | 1 (0.6%) | ||

| Yes, With organized officiating | 21 (12.0%) | ||

| Yes, Without organized officiating | 26 (14.9%) | ||

| No | 127 (72.2%) |

This study included 175 patients, 64.6% male and 35.4% female, between 16 and 90 years of age. The majority of patients were right handed (83.4%). 73 patients (41.7%) reported participating in athletics of any level, with 30 patients (17.1%) participating in contact sports and 48 patients (27.4%) participating in sports involving a hard overhead throwing motion. The majority of patients (74.2%) had a diagnosis of labral tear.

Table 2.

Summary of PRO scores for shoulder instability patients.

| Instrument | Scale | n (n missing) | Mean ± SD | Median (range) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PROMIS Global-10 Physical Health | 4–20 | 175 (0) | 13.8 (2.7) | 14.0 (6.0–20.0) |

| PROMIS Global-10 Mental Health | 4–20 | 175 (0) | 15.1 (3.4) | 16.0 (6.0–20.0) |

| PROMIS Global-10 Physical T-Score | 0–100 | 175 (0) | 44.9 (7.7) | 44.9 (23.5–67.7) |

| PROMIS Global-10 Mental T-Score | 0–100 | 175 (0) | 51.7 (9.4) | 53.3 (28.4–67.6) |

| EQ-5D | 0–1 | 175 (0) | 0.70 (0.21) | 0.78 (0.11–1.0) |

| PROMIS Estimated EQ-5D | 0–1 | 175 (0) | 0.68 (0.10) | 0.68 (0.40–0.85) |

| ASES | 0–100 | 174 (1) | 50.5 (21.4) | 50.0 (0–100) |

| WOSI | 0–100 | 80 (95) | 55.6 (33.5) | 53.12 (4.4–100) |

| SANE | 0–100 | 174 (1) | 49.4 (23.8) | 50.0 (0–100) |

ASES: American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; WORC: Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index; SANE: Subjective Assessment Numerical Evaluation.

Correlations between PROMIS Global-10 physical and mental health scores and legacy PROs for all patients and for the subgroup of 130 patients with a diagnosis of labral tear are reported in Table 3. Correlation coefficients and p-values for all correlations (including in subgroups) were identical whether PROMIS raw score or t-score was used. Overall, PROMIS Global-10 physical health score showed an acceptable correlation only with ASES (excellent-good, r = 0.69, p < 0.0005), and an unacceptable correlation with SANE (good, r = 0.43, p < 0.0005) and WOSI (poor, r = 0.17, p = 0.13). PROMIS Global-10 mental health score showed a poor correlation with all three instruments. The results were similar for patients with a diagnosis of labral tear, with physical health score correlation grades matching those of the entire patient cohort (ASES excellent-good, r = 0.69, p < 0.0006; SANE good, r = 0.44, p < 0.0005; WOSI poor, r = 0.10, p = 0.485) and mental health scores correlating poorly with all three instruments.

Table 3.

Spearman correlation coefficients between the PROMIS Global-10 and legacy instruments.

| Instrument | n (n missing) | R-Value | p-Value | Correlation strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entire patient cohort (n = 175) | ||||

| PROMIS Global-10 | ||||

| EQ-5D | 175 (0) | 0.67 | <0.0005 | Excellent-Good |

| Global-10 Physical Health | ||||

| ASES | 174 (1) | 0.69 | <0.0005 | Excellent-Good |

| WOSI | 80 (95) | 0.17 | 0.13 | Poor |

| SANE | 174 (1) | 0.43 | <0.0005 | Good |

| Global-10 Mental Health | ||||

| ASES | 174 (1) | 0.38 | <0.0005 | Poor |

| WOSI | 80 (95) | 0.12 | 0.304 | Poor |

| SANE | 174 (1) | 0.25 | 0.001 | Poor |

| Labral tear subgroup (n = 130) | ||||

| Global 10 Physical Health | ||||

| ASES | 129 (1) | 0.69 | <0.0005 | Excellent-Good |

| WOSI | 51 (79) | 0.10 | 0.485 | Poor |

| SANE | 129 (1) | 0.44 | <0.0005 | Good |

| Global 10 Mental Health | ||||

| ASES | 129 (1) | 0.37 | <0.0005 | Poor |

| WOSI | 51 (79) | 0.11 | 0.462 | Poor |

| SANE | 129 (1) | 0.25 | <0.0005 | Poor |

ASES: American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; WORC: Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index; SANE: Subjective Assessment Numerical Evaluation.

Table 4 shows correlations between PROMIS Global 10 and legacy PROs for subgroups based on athletic involvement. For athletes (n = 73) and overhead athletes (n = 48), physical health score showed excellent correlation with the ASES (r = 0.72, p < 0.0005; r = 0.76, p < 0.0005, respectively) and good correlation with SANE (r = 0.47, p < 0.0005; r = 0.51, p < 0.0005, respectively). Physical raw scores for the nonathlete (n = 102) subgroup differed significantly from those of the athlete subgroup (athletes, mean 15.12; nonathletes, mean 12.83, p < 0.0005) and showed good correlation between physical score and ASES (r = 0.52, p < 0.0005) and poor correlation between physical score and SANE (r = 0.21, p = 0.036). All correlations with mental health scores were poor. WOSI scores were not analyzed for these subgroups due to inadequate power.

Table 4.

Spearman correlation coefficients between the PROMIS Global-10 and legacy instruments for various subgroups.

| Instrument | n (n missing) | R-Value | p-Value | Correlation strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Athletes subgroup (n = 73) | ||||

| Global-10 Physical Health | ||||

| ASES | 73 (0) | 0.72 | <0.0005 | Excellent |

| SANE | 73 (0) | 0.47 | <0.0005 | Good |

| Global-10 Mental Health | ||||

| ASES | 73 (0) | 0.33 | 0.005 | Poor |

| SANE | 73 (0) | 0.19 | 0.103 | Poor |

| Nonathletes subgroup (n = 102) | ||||

| Global 10 Physical Health | ||||

| ASES | 102 (0) | 0.52 | <0.0005 | Good |

| SANE | 102 (0) | 0.21 | 0.036 | Poor |

| Global 10 Mental Health | ||||

| ASES | 102 (0) | 0.23 | 0.022 | Poor |

| SANE | 102 (0) | 0.08 | 0.443 | Poor |

| Overhead athletes subgroup (n = 48) | ||||

| Global 10 Physical Health | ||||

| ASES | 48 (0) | 0.76 | <0.0005 | Excellent |

| SANE | 48 (0) | 0.51 | <0.0005 | Good |

| Global 10 Mental Health | ||||

| ASES | 48 (0) | 0.32 | 0.026 | Poor |

| SANE | 48 (0) | 0.27 | 0.059 | Poor |

ASES: American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; WORC: Western Ontario Rotator Cuff Index; SANE: Subjective Assessment Numerical Evaluation.

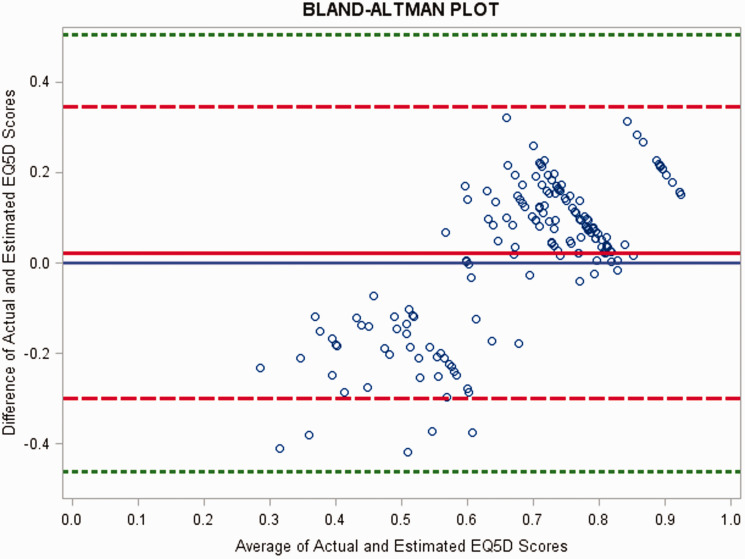

The PROMIS Global-10 estimated EQ-5D scores showed an overall acceptable correlation with actual EQ-5D scores (excellent-good, 0.67, p < 0.0005), with a mean difference of 0.02 between actual and estimated scores. Variability between answer responses was assessed using a Bland–Altman analysis (Figure 2) and showed that at scores below 0.6, PROMIS Global-10 overestimates the actual EQ-5D score, whereas at scores above 0.6, PROMIS Global-10 underestimates the actual EQ-5D. 95% confidence intervals were 0.30 below to 0.34 above on a 0 to 1 scale indicating high levels of variability.

Figure 2.

Plot demonstrating the difference between the actual EQ-5D score and the estimated EQ-5D score from PROMIS (vertical axis) and the average of actual EQ-5D score and the estimated EQ-5D score (horizontal axis). Each dot represents one respondent. The blue lines are the lower and upper 95% limits of agreement, and the red lines are the lower and upper 95% confidence interval for the lower and upper limits.

No floor or ceiling effects were present in the entire patient cohort (Table 5), although ceiling effects were noted for PROMIS mental health score in patients aged less than 18 (25% with maximum score) and patients aged 18–25 (18.8% with maximum score). No patients reached the minimum physical or mental score.

Table 5.

Analysis of floor and ceiling effects of the PROMIS Global-10: number of patients reaching minimum or maximum score.

| Minimum score (%) | Maximum score (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Entire patient cohort (n = 175) | ||

| Global-10 Physical Health Score | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) |

| Global-10 Mental Health Score | 0 (0%) | 16 (9.1%) |

| Age <18 years subgroup (n = 12) | ||

| Global-10 Physical Health Score | 0 (0%) | 1 (8.3%) |

| Global-10 Mental Health Score | 0 (0%) | 3 (25.0%) |

| Age 18–25 years subgroup (n = 32) | ||

| Global-10 Physical Health Score | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Global-10 Mental Health Score | 0 (0%) | 6 (18.8%) |

| Age 25–40 years subgroup (n = 41) | ||

| Global-10 Physical Health Score | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Global-10 Mental Health Score | 0 (0%) | 3 (7.3%) |

| Age > 40 years subgroup (n = 90) | ||

| Global-10 Physical Health Score | 0 (0%) | 0 (0) |

| Global-10 Mental Health Score | 0 (0%) | 4 (4.4%) |

Discussion

This study set out to validate the PROMIS Global-10 compared with legacy PROs in patients with shoulder instability to determine its utility as a universal outcome collection tool. To improve the efficacy of orthopedic care, it is essential to reliably and efficiently record and analyze patient outcomes. The PROMIS Global-10 is a low-burden 10-question assessment that evaluates both physical and mental health status which, if valid across a variety of disease states and patient populations, may provide a consistent means of recording outcomes across a variety of treating specialties. However, in our study population of 175 patients, the PROMIS Global-10 physical health scores showed an acceptable correlation with ASES score (excellent-good) and an unacceptable correlation with SANE (good) and WOSI (poor). The PROMIS Global-10 mental health scores were poorly correlated with all three traditional PROs. Anthony et al.26 previously validated the PROMIS UE in patients with shoulder instability, finding excellent correlation with SF-36 PF (r = 0.78, p < 0.01) and ASES (r = 0.71, p < 0.01) and excellent-good correlation with WOSI (r = 0.63, p < 0.01). They also evaluated the PROMIS PF CAT, reporting excellent correlation with SF-36 PF (r = 0.72, p < 0.01) and excellent-good correlation with ASES (r = 0.67, p < 0.01) in the same cohort. Taken together with our study findings, alternative use of the PROMIS UE or PROMIS PF CAT rather than legacy PROs appears to be more appropriate and valid than using the PROMIS Global-10 for patients with shoulder instability.

The PROMIS Global-10 physical scores showed excellent and good correlation with ASES and SANE, respectively, in a subgroup analysis of athletes and overhead athletes, while physical health scores in nonathletes showed a good correlation with ASES and poor correlation with SANE. Plausible explanations for these differing results include that nonathletes tend to be older and likely possess a greater number of medical comorbidities compared to athletes. The presence of medical comorbidities would likely jeopardize the correlation between a global health PRO and an extremity-specific PRO because only the score of the former would be decreased by a nonshoulder-related disease.

In our study cohort, the estimated EQ-5D score from the PROMIS Global-10 showed an acceptable correlation with the actual EQ-5D score (excellent-good, r = 0.67, p < 0.0005). However, Bland–Altman analysis revealed significant levels of variance between actual and estimated EQ-5D scores, with PROMIS Global-10 tending to overestimate EQ-5D score at lower scores and underestimate it at higher scores. The 95% limits of agreement comprised 0.30 below to 0.34 above the mean score on a 0 to 1 scale, which is outside of the −0.2 to +0.2 limits of acceptance reported by Revicki et al.10,24 Therefore, in this study population, the estimated EQ-5D score from the PROMIS Global-10 is not a sufficient substitute for EQ-5D-derived quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for use in cost-effectiveness evaluations.

Neither the PROMIS Global-10 physical nor mental health scores showed floor or ceiling effects in this patient population, but a ceiling effect in mental health scores was noted in patients under the age of 25. This suggests that in patients with shoulder instability, PROMIS Global-10 physical health score is capable of measuring extremes of physical function, but PROMIS Global-10 mental health score is not capable of measuring minor differences in young patients with excellent mental health.

Limitations of this study include the lack of comparison between PROMIS PF CAT and PROMIS UE with PROMIS Global-10 results, which prevents the comparison of our results with those of previous studies validating other PROMIS instruments in patients with shoulder instability. Additionally, asking patients to complete multiple lengthy PROs in immediate succession may have led to fatigue, jeopardizing the validity of the results of later questionnaires. All patients completed the WOSI last, which may partially explain its poor correlation with PROMIS results as well as its poor response rate (completed by 80/175, 46% of patients). This incomplete response rate for the WOSI also limited our ability to correlate WOSI results in the subgroups of athletes, nonathletes, and overhead athletes, all of which did not have enough WOSI responses to provide adequate power based on our a priori calculation. These issues may be addressed in future studies by randomizing the sequence of PRO administration. The method of obtaining WOSI responses by relying on patients to select a diagnosis of shoulder instability, if known, may also have introduced selection bias in WOSI results, since only patients whose shoulder instability had previously been assessed and diagnosed were able to complete the WOSI. Furthermore, all patients in this population received treatment at a single large academic institution, potentially reducing the generalizability of our results to patients being seen at other institutions or at smaller, private clinics. Finally, the acquisition of longitudinal PRO measurements including preoperative and postoperative assessments would prove useful for the validation of PROMIS Global-10 patient responsiveness to the surgical treatment.

Conclusions

The findings from this study suggest that the PROMIS Global-10 is not a valid alternative to legacy general and upper-extremity specific PROs in patients with shoulder instability. While the Global-10 physical function score demonstrated an acceptable correlation with ASES, the correlations to SANE and WOSI were below acceptable standards. Since WOSI is the only disease-specific PRO evaluated in this study, it is arguably the most important legacy instrument for evaluating the loss of physical function that specifically results from shoulder instability. Therefore, the poor correlation with WOSI suggests that the PROMIS physical function score alone is an unsatisfactory assessment of disability in this patient population. Furthermore, due to its poor correlation with all legacy PROs that we compared it to, the PROMIS Global-10 mental health score could not replace legacy PROs for this shoulder disorder. Lastly, the estimated EQ-5D from the PROMIS Global-10 does not agree well with actual EQ-5D scores due to a high level of individual response variability, and as such, it is not a valid alternative to the EQ-5D to derive QALYs for cost-effectiveness evaluations.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: David Kovacevic is a committee member of American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, American Orthopaedic Association, and American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons, and serves on the editorial or governing board for Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. Hafiz Kassam serves on the editorial or governing board for the Journal of Shoulder and Elbow Arthroplasty.

Ethical Review and Patient Consent

Investigation approved by the Yale University Human Investigation Committee (HIC) as per HIC Protocol Number 1510016580. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. For patients under 18 years, written informed consent was obtained from a parent or guardian who was present during questionnaire completion.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Funding for this work was made possible by the Yale Shoulder & Elbow Research Foundation.

References

- 1.Baker A. Crossing the quality chasm: a new health system for the 21st century. Br Med J 2001; 323: 1192–1192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stulberg J. The physician quality reporting initiative – a gateway to pay for performance: what every health care professional should know. Qual Manage Healthc 2008; 17: 2–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Group M. Patient-reported outcomes in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg 2018; 100: 436–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patrick DL, Guyatt GH and Acquadro C. Patient-reported outcomes. In: Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: Cochrane book series, 2008, pp. 531–545.

- 5.Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. Br Med J 2013; 346: f167–f167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Porter ME. What is value in health care? New Engl J Med 2010; 363: 2477–2481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hurwitz SR, Slawson D, Shaughnessy A. Orthopaedic information mastery: applying evidence-based information tools to improve patient outcomes while saving orthopaedists’ time. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2000; 82: 888–894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung M, Clegg DO, Greene T, et al. Evaluation of the PROMIS physical function item bank in orthopaedic patients. J Orthop Res 2011; 29: 947–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wyer PC, Silva SA. Where is the wisdom? I–a conceptual history of evidence-based medicine. J Eval Clin Pract 2009; 15: 891–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, et al. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res 2009; 18: 873–880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Graham B, Green A, James M, et al. Measuring patient satisfaction in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015; 97: 80–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jansson K-Å, Granath F. Health-related quality of life (EQ-5D) before and after orthopedic surgery. Acta Orthop 2011; 82: 82–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bohannon RW, DePasquale L. Physical Functioning Scale of the Short-Form (SF) 36: internal consistency and validity with older adults. J Geriatr Phys Ther 2010; 33: 16–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fidai MS, Saltzman BM, Meta F, et al. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system and legacy patient-reported outcome measures in the field of orthopaedics: a systematic review. Arthroscopy 2018; 34: 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.King GJ, Richards RR, Zuckerman JD, et al. A standardized method for assessment of elbow function. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8: 351–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kocher MS, Horan MP, Briggs KK, et al. Reliability, validity, and responsiveness of the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons subjective shoulder scale in patients with shoulder instability, rotator cuff disease, and glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2005; 87: 2006–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kirkley A, Griffin S, McLintock H, et al. The development and evaluation of a disease-specific quality of life measurement tool for shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 1998; 26: 764–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jepson C, Asch DA, Hershey JC, et al. In a mailed physician survey, questionnaire length had a threshold effect on response rate. J Clin Epidemiol 2005; 58: 103–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beckmann JT, Hung M, Bounsanga J, et al. Psychometric evaluation of the PROMIS Physical Function Computerized Adaptive Test in comparison to the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score and Simple Shoulder Test in patients with rotator cuff disease. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2015; 24: 1961–1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cella D, Yount S, Rothrock N, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS): progress of an NIH Roadmap cooperative group during its first two years. Med Care 2007; 45: S3–S3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ader DN. Developing the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS). LWW, 2007.

- 22.Smith MV, Klein SE, Clohisy JC, et al. Lower extremity-specific measures of disability and outcomes in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94: 468–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith MV, Calfee RP, Baumgarten KM, et al. Upper extremity-specific measures of disability and outcomes in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2012; 94: 277–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Revicki DA, Kawata AK, Harnam N, et al. Predicting EuroQol (EQ-5D) scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items and domain item banks in a United States sample. Qual Life Res 2009; 18: 783–791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Riley WT, Rothrock N, Bruce B, et al. Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) domain names and definitions revisions: further evaluation of content validity in IRT-derived item banks. Qual Life Res 2010; 19: 1311–1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anthony CA, Glass NA, Hancock K, et al. Performance of PROMIS instruments in patients with shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med 2017; 45: 449–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap) – a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform 2009; 42: 377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shoukri MM, Cihon C. Statistical methods for health sciences, Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McHorney CA, Tarlov AR. Individual-patient monitoring in clinical practice: are available health status surveys adequate? Qual Life Res 1995; 4: 293–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]