Abstract

Remodeling of extracellular matrix in the womb facilitates the dramatic morphogenesis of maternal and placental tissues necessary to support fetal development. In addition to providing a scaffold to support tissue structure, extracellular matrix influences pregnancy outcomes by facilitating communication between cells and their microenvironment to regulate cellular adhesion, migration, and invasion. By reviewing the functions of extracellular matrix during key developmental milestones, including fertilization, embryo implantation, placental invasion, uterine growth, and labor, we illustrate the importance of extracellular matrix during healthy pregnancy and development. We also discuss how maladaptive matrix expression contributes to infertility and obstetric diseases such as implantation failure, preeclampsia, placenta accreta, and preterm birth. Recently, advances in engineering the biotic–abiotic interface have potentiated the development of microphysiological systems, known as organs-on-chips, to represent human physiological and pathophysiological conditions in vitro. These technologies may offer new opportunities to study human fertility and provide a more granular understanding of the role of adaptive and maladaptive remodeling of the extracellular matrix during pregnancy.

Impact statement

Extracellular matrix in the womb regulates the initiation, progression, and completion of a healthy pregnancy. The composition and physical properties of extracellular matrix in the uterus and at the maternal–fetal interface are remodeled at each gestational stage, while maladaptive matrix remodeling results in obstetric disease. As in vitro models of uterine and placental tissues, including micro-and milli-scale versions of these organs on chips, are developed to overcome the inherent limitations of studying human development in vivo, we can isolate the influence of cellular and extracellular components in healthy and pathological pregnancies. By understanding and recreating key aspects of the extracellular microenvironment at the maternal–fetal interface, we can engineer microphysiological systems to improve assisted reproduction, obstetric disease treatment, and prenatal drug safety.

Keywords: Extracellular matrix, pregnancy, placenta, maternal–fetal interface, obstetric diseases

Introduction

Before conception and throughout gestation, the womb integrates a multitude of signals to become a receptive environment capable of supporting embryonic growth and development. While much attention has been given to the role of hormones and growth factors during this transformation,1,2 cells in the womb also receive important biophysical and biochemical cues from their surrounding extracellular matrix. Extracellular matrix is composed of fibrous proteins and viscous proteoglycans that provide a three-dimensional scaffold within which cells adhere.3,4 Once viewed as a passive substrate,5 the extracellular matrix is now recognized as a key regulator of embryonic development, organ growth, and disease progression.6,7 While it is well accepted that extracellular matrix regulates cell differentiation and morphogenesis in the embryo proper,8 the role of extracellular matrix in regulating the structural and functional changes that occur in the womb and at the maternal–fetal interface is not yet fully appreciated.

During pregnancy, extracellular matrix maintains the structural integrity of the uterus, facilitates embryo adhesion, and regulates placental invasion into the endometrium to form the maternal–fetal interface. To mediate these processes, the extracellular matrix attaches to the cells via membrane bound adhesion molecules including integrins and selectins.9,10 Through these connections, cells sense the physical characteristics of their microenvironment, including substrate stiffness, pressure, shear, and stretch, and convert these mechanical cues into chemical and electrical signals that regulate cell structure and behavior.11–13 Throughout gestation, the extracellular matrix is dynamically remodeled, constantly deposited and degraded to support evolving tissue functions.14 The spatiotemporal regulation of this remodeling is critical; if matrix molecules in the womb are abnormally expressed, pathological conditions of reproduction and pregnancy often occur.15–19 For example, placenta accreta spectrum disorder—an obstetric disease characterized by unrestricted placental invasion—is thought to arise from maladaptive matrix signaling from fibrotic scar tissue in the womb. As a result, placental overgrowth poses a great risk of maternal hemorrhage, often necessitating surgical removal of the placenta and uterus upon delivery.20 While this condition was once extremely rare, placenta accreta is becoming more prevalent as the rate of cesarean deliveries increases,21 and there are few options for more conservative treatments.22 Thus, there is a pressing need to better understand the interactions between cells and extracellular matrix at the maternal–fetal interface in the progression of healthy pregnancies to inform efforts to treat obstetric diseases.

In this review, we argue that extracellular matrix in the uterus and at the maternal-fetal interface is a primary determinant of pregnancy outcome. To support this claim, we review the functions of the extracellular matrix and matrix-mediated cellular processes in the context of key milestones that occur throughout gestation. We discuss how extracellular matrix in the womb facilitates cellular adhesion and migration and supports tissue growth mediated by mechanical signaling. We also review extracellular matrix composition and remodeling typical of a healthy pregnancy and discuss cases where aberrant expression or maladaptation of the remodeling process results in reproductive and obstetric complications such as implantation failure, preeclampsia, placenta accreta, and preterm labor. Finally, we discuss the recreation of native matrix in in vitro models of the female reproductive tract to study developmental toxicities and to facilitate the discovery of novel treatments for infertility and obstetric diseases.

Extracellular matrix facilitates fertilization and implantation

Even before conception, extracellular matrix in the reproductive tract lays the foundation for a successful pregnancy. In mammalian ovaries, oocytes mature in follicles surrounded by cumulus cells that produce a matrix cushion that encapsulates and protects the egg.23 In response to an ovulatory surge in luteinizing hormone, this cushion thickens to form the zona pellucida.24 The zona pellucida is a transparent membrane which is composed of a hyaluronic acid and specialized glycoproteins that protects the egg during release from the ovary and facilitates fertilization.25 If matrix molecules or their crosslinkers are disrupted or missing from the zona pellucida, oocyte release and fertilization are impaired, resulting in infertility or sterility.26–28 Matrix composition is affected by a number of factors, including disrupted endocrine function during the menstrual cycle and genetic abnormalities that affect matrix protein production.29,30

A few days after an egg is fertilized, the resulting conceptus must implant into the endometrium, the inner lining of the uterus, to continue normal growth and development. Because both embryonic and endometrial signaling pathways must be synchronized, the timing of implantation is critical.31,32 If implantation occurs two or three days early or late, the risk of spontaneous abortion or pregnancy complications increases dramatically.33,34 Steroid hormones35 and other signaling molecules are coordinated during the menstrual cycle to create a “window of receptivity”, a period when conditions are optimal for embryo implantation. The composition of extracellular matrix in the endometrium helps to define this window of receptivity (Table 1, Figure 1(a)), which is marked by a reduction of matrix molecules that prevent adhesion and an increase in integrin expression to facilitate attachment between the embryo and uterine wall.36

Table 1.

Distribution of select extracellular matrix proteins in the womb.

| Matrix | Location/structure | Adaptive remodeling | Refs | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Endometrium | Collagen I | Interstitial fibers | – | 14,37 | |

| Collagen III | Interstitial fibers | ↓ in decidualization | 14 | ||

| Collagen V | Interstitial fibers | ↑ in decidualization | 14 | ||

| Fibrillin | Decidual cells | ↑ in 1st & 2nd trimester | 38 | ||

| Fibulin | Decidual cells | ↓ during 1st trimester | 39 | ||

| Elastin | – | – | 38 | ||

| Tenascin C | Stroma | ↓ in secretory phase | 40 | ||

| Hyaluronan | Stroma and vessels | ↓ in secretory phase | 41 | ||

| Fibronectin | Basement membrane & PCM | ↑ in decidualization | 42 | ||

| Laminin | Basement membrane & PCM | ↑ in decidualization | 42 | ||

| Collagen IV | Basement membrane & PCM | ↑ in decidualization | 42 | ||

| Heparan Sulfate | Basement membrane & PCM | ↑ in decidualization | 42 | ||

| Placenta | Collagen I | Stromal fibers & vessels | ↓ in 3rd trimester | 43 –45 | |

| Collagen III | Stromal thin beaded fibers | – | 44 | ||

| Collagen V | Stromal thin filaments | – | 44 | ||

| Fibrillin | Villous stroma | ↑ in 3rd trimester | 43,46 | ||

| Fibulin | Villous/extravillous trophoblast | ↑ 1st, 2nd,3rd trimester | 47 | ||

| Elastin | Stroma and vessels | – | 43,48 | ||

| Tenascin C | Stroma and vessels | – | 43 | ||

| Hyaluronan | Stroma and vessels | – | 49 | ||

| Fibronectin | Stroma & basement membrane | ↑ in 3rd trimester | 44 | ||

| Laminin | Stroma & basement membrane | ↑ in 3rd trimester | 43–45 | ||

| Collagen IV | Stroma & basement membrane | ↑ 1st, 2nd,3rd trimester | 43,44 | ||

| Heparan sulfate | Stroma & basement membrane | 50 | |||

| Myometrium | Collagen I | Smooth muscle cells | ↓ in 3rd trimester | 51 | |

| Collagen III | Smooth muscle cells & fibers | ↑ in pregnancy | 51 | ||

| Collagen V | Smooth muscle cells | – | 51,52 | ||

| Fibrillin | Colocalized with elastin fibers | ↑ in pregnancy | 53 | ||

| Fibulin | – | – | – | ||

| Elastin | Outer myometrium | ↑ in pregnancy | 54,55 | ||

| Tenascin C | Basement membrane and smooth muscle | ↑ in pregnancy | 56,57 | ||

| Hyaluronan | Cervical tissue | ↑ at term & labor | 58 | ||

| Fibronectin | Connective tissue & PCM | ↑ in late pregnancy | 51 ,59 | ||

| Laminin | Basement membrane | ↑ in pregnancy | 60 | ||

| Collagen IV | Basement membrane | ↑ in late pregnancy | 53,59 | ||

| Heparan sulfate | Cervix & PCM | ↑ in labor | 61 | ||

PCM: pericellular matrix.

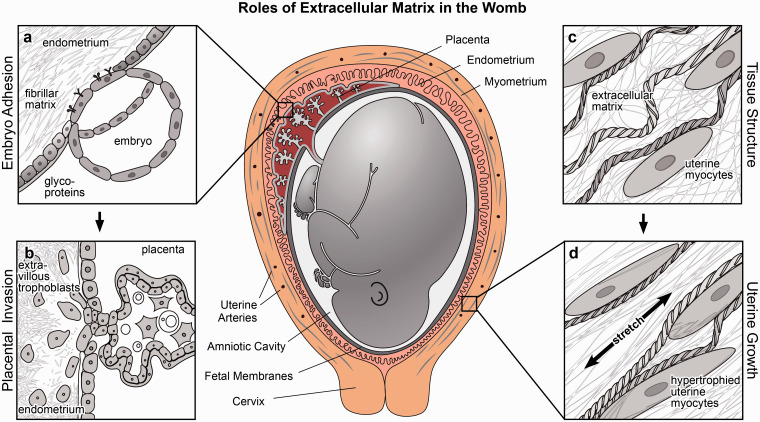

Figure 1.

Roles of extracellular matrix in the womb. Extracellular provides structural support in the womb and mediates important cellular processes including adhesion, migration, invasion, and mechanical signaling. (a) Extracellular matrix regulates embryonic adhesion by defining a window of receptivity for implantation. (b) Extracellular matrix guides placental invasion and is dynamically remodeled when extravillous trophoblasts invade the endometrium. (c–d) Extracellular matrix forms a fibrillar scaffold to reinforce tissue strength and extensibility, propagating mechanical signals that induce stretch-mediated hypertrophy and uterine contractile activation at the onset of labor.

Throughout the menstrual cycle, endometrial matrix composition shifts in response to cycling levels of estrogen and progesterone to balance factors that prevent or potentiate embryonic adhesion.62 Before ovulation, the surface of the endometrium is coated with anti-adhesion glycoproteins, such as mucin and Tenascin-C, that inhibit cell attachment until secretion is suppressed or cleared by cell surface proteases.40,63 After ovulation, the endometrium undergoes a process known as decidualization, where endometrial fibroblasts differentiate into secretory decidual cells that produce extracellular matrix and secrete factors that nourish the embryo.64 As steroid hormone levels increase, decidual cells deposit matrix proteins such as laminin, entactin, fibronectin, collagen IV, and heparan sulfate in the glandular areas of the endometrium to promote embryonic attachment and invasion.42,65 Heparan sulfate, in particular, has been shown to facilitate implantation as it is recognized by selectins found on the outer layer of the blastocyst.66 Decidual cells also synthesize more collagen V, which has high affinity for heparan sulfates and is thought to stabilize growth factors found in the extracellular microenvironment.67,68 Together, the reduction of anti-adhesive glycoproteins and the synthesis of proteoglycans which promote cell–matrix and matrix–matrix interactions help to create a receptive and adhesive environment for implantation.

Coinciding with the secretion of specific matrix molecules during decidualization, transiently expressed integrins in the endometrium also signify the window of receptivity for implantation. In decidual cells, integrin activation potentiates cytoskeletal remodeling and focal adhesion assembly that stabilizes embryo apposition and attachment to the uterine wall, which are important initial steps in implantation.69 Evidence from animal models has shown that implantation efficiency is impaired when certain integrins are inhibited or lacking. For example, mice embryos lacking integrin ß1, which is required for implantation, do not develop beyond the point when normal embryos implant.70 Further, mice and rabbits that receive an intrauterine injection of integrin αVß3 blocking antibody have fewer successful implantations than control animals injected with bovine serum albumin or antibodies for non-RGD peptides.71,72 Integrins αV and ß3 are also thought to be involved in regulating human implantation, as both integrins are temporarily upregulated during decidualization and ovulation.10

Aberrant expression of these integrins has been observed in women with a history of infertility and endometriosis, an inflammatory disease of the inner lining of the uterus. In some cases, integrin ß3 expression is delayed, resulting in a window of endometrial receptivity that is not synchronized with the developmental stage of the embryo trying to implant.10 In other cases, integrin ß3 expression is reduced in endometrial lesions, which may contribute to the subfertility often seen in women with endometriosis.40 Reduced sensitivity to progesterone in endometriosis further disrupts the balance of matrix deposition and degradation necessary for decidualization and implantation.73–75 Because of their role in implantation, integrins and adhesive extracellular matrix molecules are potential biomarkers to improve assisted reproductive technologies and fertility treatments. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that extracellular matrix composition and binding site availability contribute to endometrial receptivity and thereby regulate embryo implantation.

Extracellular matrix guides placental invasion

After a blastocyst apposes and attaches to inner lining of the uterus, extraembryonic cells that will form the placenta begin to migrate into and remodel the endometrium. These invasive cells, called extravillous trophoblasts, travel along fibrillar matrices in uterine tissue, degrading and depositing new matrix proteins as they anchor the embryo to the uterine wall (Figures 1(b) and 2(a) and (b).76 In concert with decidual cells and maternal immune cells, extravillous trophoblasts use enzymes such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) to degrade the native matrix and remodel uterine spiral arteries, ensuring sufficient blood flow from the maternal to the fetal compartment.43,79,80 As the placenta develops, it secretes hormones that further stimulate matrix deposition and protease secretion in both placental trophoblasts and maternal endometrial cells.81 Ultimately, the degree of tissue remodeling and vascularization is regulated by a delicate balance of MMP expression, enzymatic activation, and abundance of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs),82 which are controlled by a combination of steroid hormones as well as genetic and epigenetic programming.83,84

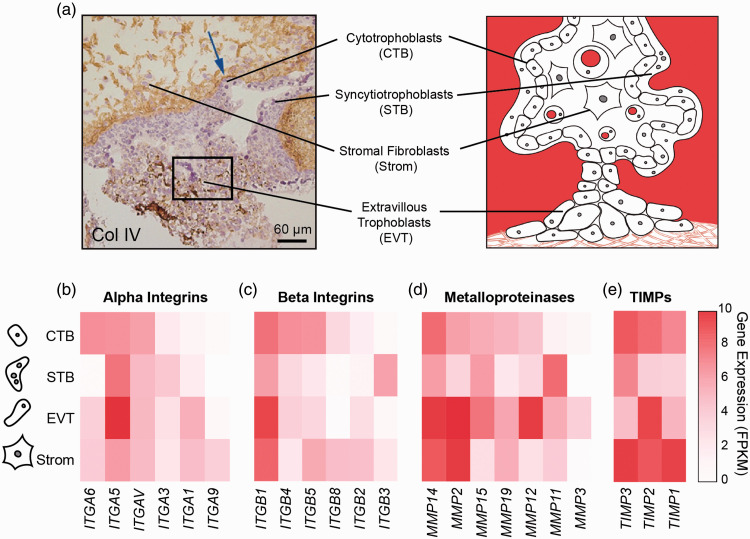

The spatiotemporal regulation of integrins and MMP expression in the placenta and endometrium is critical for proper trophoblast invasion. In early pregnancy when the placenta is most invasive, these extravillous trophoblasts secrete mostly MMP-2, a gelatinase that targets collagens and basement membrane proteins near the surface of the endometrium.85 By the end of the first trimester, these cells also secrete MMP-9 to degrade interstitial collagens deeper in the uterus.86 Expression of integrins and MMPs also varies among trophoblasts derived from different regions of the placenta.87,88 To illustrate this differential expression, we parsed integrin and MMP expression data from a genome-wide transcription study of sorted trophoblast cells isolated from first trimester placentas (Figure 2(c) to (e)).77 Here, we see that extravillous trophoblasts express more fibronectin-binding integrins and basement membrane degrading proteases than other cell types in the placenta, which is necessary to penetrate endometrial basal lamina. If MMPs or their target matrix proteins are missing or are overabundant, the placenta cannot invade properly, resulting in obstetric syndromes that increase risks of both maternal and fetal morbidity.18,89–91

Figure 2.

Integrin and matrix metalloproteinase gene expression in placental cell types. (a) First trimester placental villi stained for Collagen IV and counterstained with hematoxylin and simplified illustration (right). Arrow indicates basement membrane staining and box represents globular Col IV in extravillous column (reprinted with permission from Oefner et al.78). (b–e) Heatmaps of alpha (panel b) and beta (panel c) integrin and matrix metalloproteinase (panel d) and tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases (panel e) transcription levels in placental cells (RNA sequencing data were extracted from a previously published dataset77) For clarity, only genes with more than 3.6 fragments per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (FPKM) in at least one cell type are included.

Insufficient placental invasion is thought to contribute to preeclampsia, an obstetric disease characterized by the onset of hypertension, proteinuria, and maternal inflammation after the 20th week of pregnancy.92 During preeclampsia, shallow trophoblast invasion and incomplete remodeling of the spiral arteries result in reduced placental volume and increased blood pressure that often lead to fetal growth restriction.93,94 Aberrant integrin and MMP expression at the maternal fetal interface are one explanation for this restricted invasion. For example, placental cells isolated from patients with preeclampsia express lower levels of integrins and MMPs that bind to and degrade laminin, collagen, and fibronectin compared to cells from normal pregnancies.19,90 Genetic deficiency in MMP-9—a proteinase that cleaves collagens that are abundant in the womb—impairs trophoblast invasion and decidualization in mice, producing a preeclamptic phenotype with intrauterine growth restriction, hypertension, and proteinuria.89 Interestingly, not all matrix degrading enzymes are reduced in preeclampsia. Patients with preeclampsia have elevated levels of extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducers circulating in their bloodstream, while their placentae express a broader range of MMPs, suggesting a possible compensatory mechanism to overcome insufficient invasion and vascular remodeling.95,96 However, matrix fragments generated by excessive proteases can cause inflammation by triggering additional immune cell activation and recruitment.97,98 Therefore, maladaptive proteinase expression and aberrant remodeling of the extracellular matrix at the maternal–fetal interface contribute to both insufficient invasion at the onset of preeclampsia and overactive maternal immune response seen in the later stages of the disease.99

Maladaptive matrix proteinase expression in the womb is also associated with excessive trophoblast invasion as seen in placenta accreta spectrum disorder. Instead of adhering to and remodeling maternal tissues to connect to the maternal circulation, these placentae penetrate the deep muscular layers of the uterus and sometimes even enter the abdominal cavity, resulting in a cancer-like growth. Overly invasive placentas show increased expression of MMPs and lower levels of enzyme degradation inhibitors.100 Specifically, extravillous trophoblasts from patients with placenta accreta spectrum disorder retain the highly invasive phenotype of first trimester trophoblasts well into the third trimester of gestation.101 Although the disease is characterized by improper trophoblast invasion, placenta accreta spectrum disorder is not considered to be a disease of placental origin. On the contrary, risk factors for placenta accreta spectrum include past uterine surgeries such as cesarean section and uterine fibroid removal, suggesting disruption in maternal endometrial tissue architecture is a contributing factor in the disease.102 Disorganized and fibrotic extracellular matrix in uterine scar tissues is weaker than that of healthy tissue and presents points of entry for excessive invasion.103 To improve uterine tissue integrity and reduce scar formation after cesarean deliveries, matrix-based scaffolds have emerged as an approach to facilitate wound healing in the womb.104–106 By recapitulating the healthy matrix that supports cellular migration and integration, tissue-engineered wound healing approaches may reduce scar formation in the uterus after cesarean delivery, thereby ameliorating the risk of developing placenta accreta spectrum disorder in subsequent pregnancies. Altogether, these results emphasize the importance of uterine matrix integrity in regulating trophoblast invasion and underscore the potential for novel approaches to improve scarless wound healing after cesarean delivery.

Extracellular matrix remodeling during uterine growth and labor

In the uterus, layers of smooth muscle and extracellular matrix wrap circumferentially and longitudinally around the uterine cavitity.107 Within these layers, the concentration and structure of extracellular matrix change throughout pregnancy to enable dramatic growth and expansion without increasing intrauterine pressure.54 Strikingly, the matrix surrounding the outer layer of the uterus possesses not only the strength to withstand forces generated during labor but also the flexibility to expand to a volume almost 500 times its original size.107 Matrix strength derives from elaboration by uterine cells that remodel the extracellular fibrils that reinforce tissues (Figure 1(c)). For example, small collagen fibrils are degraded and reassembled within the uterus to form larger collagen bundles that increase tissue strength.37,51,60 Thicker elastic fibers are similarly formed by increased expression of elastin and fibrillin to accommodate tissue strain.55 Further, basement membrane proteins are upregulated near the end of term, with increased deposition near hypertrophied muscle cells to improve cellular integration within the tissue.59 Interestingly, this increase in extracellular matrix deposition is only temporary. Towards the end of pregnancy, the body begins to degrade the additional matrix and soften uterine tissue,108 thereby increasing connectivity between uterine muscle cells to achieve synchronized contractions for labor.109,110

The dynamic deposition and remodeling of extracellular matrix proteins are important for maintaining a healthy pregnancy and enabling a safe labor and delivery. If extracellular matrix composition is disrupted or lacking, the structural integrity of the uterus is impaired.111 For example, women with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome, a family of diseases that disrupts connective tissues in the body, are more likely to experience obstetric complications including premature rupture of membranes and preterm birth.112 Pregnant patients with severe forms Ehlers-Danlos syndrome also face an increased risk of uterine rupture and maternal mortality.113 The hypothesized mechanism of premature membrane rupture is a defect in collagen synthesis, which weakens the chorionic membrane of the affected fetus.114 Aside from genetic defects that impair collagen synthesis, uterine integrity is also compromised in women with who have had a previous cesarean delivery.115,116 After a cesarean section, fibrotic scar tissue with increased but disrupted collagen at the site of the incision leads to uterine tissue weakness that is more prone to rupture in subsequent pregnancies.117–119 While cesarean scar niche formation directly effects myometrial tissue mechanical properties, including elasticity, extensibility, and strength, the close proximity of uterine tissues with the chorionic and amniotic membrane can influence their mechanical properties as well.111,119 Together, these clinical observations suggest that extracellular matrix plays an important role in maintaining uterine integrity throughout pregnancy and delivery.

Throughout gestation, uterine growth is mediated by a combination of steroid hormone dynamics and mechanical stretch. In early pregnancy, uterine myocyte hyperplasia and matrix deposition are triggered by hormones released by the ovaries and the nascent placenta. Specifically, both estrogen and progesterone stimulate increased extracellular matrix production and remodeling in the womb that increase tissue strength and extensibility.111 As pregnancy progresses, mechanical stretch plays a more significant role by modulating uterine response to hormonal cues and transmitting physical signals that modulate gene expression and cellular function. Importantly, uterine stretch caused by the growing fetus is necessary for the normal induction of matrix protein expression.98 Even in the absence of steroid hormones, stretch alone can induce uterine growth and protein production; for example, when a balloon was used to inflate the uterus of ovariectomized rabbits, uterine cell mass and protein expression increased as if the animals were pregnant.37 Mechanical stretch also regulates uterine muscle hypertrophy that enables uterine contractility in the later stages of pregnancy and labor (Figure 1(d)).120,121 After first proliferating in early pregnancy, uterine myocytes then grow and expand by hypertrophy, simultaneously becoming more excitable and contractile in preparation of labor. Importantly, these muscle cells do not contract synchronously until active labor begins.122 For labor to begin, the extracellular matrix that once reinforced tissue strength must be degraded to enable electromechanical coupling between uterine myocytes. Like extracellular matrix production, matrix degradation is also regulated by a combination of hormonal and mechanical signals. Injections of progesterone in the final days of pregnancy can postpone matrix degradation and the onset of labor in rats.59 The activity of matrix degradation enzymes is also sensitive to stretch,123 further contributing to the mechanosensitive matrix remodeling and tissue softening that is necessary for labor to begin.

Due to its regulation of labor onset in normal pregnancies, mechanical signaling has been investigated as a potential cause of preterm labor and preterm birth. Preterm birth—or delivery that occurs before 37 weeks gestation—affects between 5% and 18% of pregnancies and is the leading cause of infant mortality and morbidity.85,124 Of these preterm deliveries, approximately two-thirds are due to preterm labor and premature rupture of fetal membranes, and one-third represent medical interventions to treat preeclampsia or fetal growth restriction.125 Mechanical signaling and maladaptive remodeling of extracellular matrix in the myometrium or fetal membranes contribute to certain cases of spontaneous preterm labor. For example, twin or multiple gestation pregnancies are more likely to result in preterm birth, in part because the uterus stretches and remodels more rapidly than in singleton pregnancies.126–128 Pregnant patients with a history of endometriosis also face increased risk of premature rupture of membranes or preterm birth.129 Just as reduced progesterone sensitivity in early pregnancy impairs decidualization and implantation, aberrant expression of MMPs and TIMPs near term can cause precocious softening of the cervix and amnion.111 Further, uterine collagenase and elastase expression in both term and preterm labor are also upregulated in response to stretch and can induce contraction of uterine smooth muscle cells necessary for labor.110 In sum, matrix degrading enzymes are critical for the completion of normal labor and represent possible pharmacological targets for preventing or postponing preterm labor.

Recapitulating the maternal–fetal interface in vitro

While extracellular matrix performs key roles in pregnancy, it remains difficult to fully elucidate how matrix aberrations lead to obstetric disease and how to correct them to improve pregnancy outcomes. Difficulties stem from the limitations of clinical trials in pregnant women and species variation in reproductive anatomy and gestation in animal models.130 Further, the multivariate interactions that influence extracellular matrix remodeling, including hormonal and immune signaling, are difficult to control and manipulate in vivo. Therefore, there is a need for alternative approaches to study the contributions of extracellular matrix remodeling in healthy and pathological pregnancies.

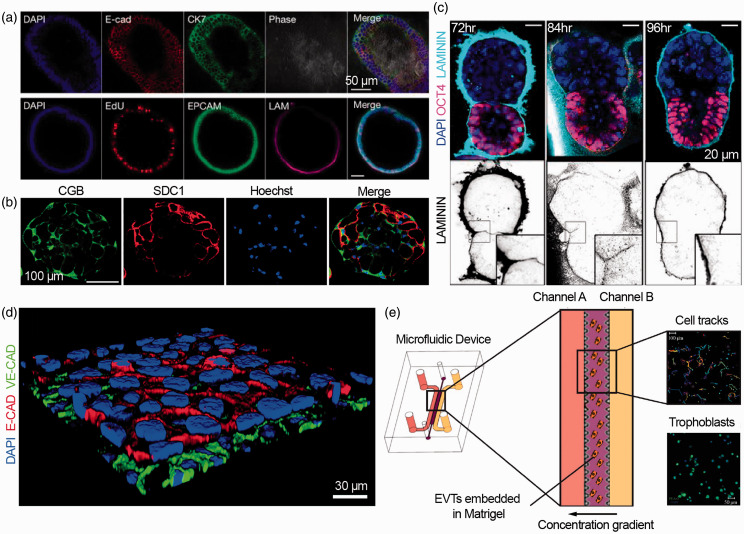

Addressing the limitations of in vivo experiments, complex reproductive tissue structures have already been generated from stems cells and primary cell cultures in vitro. For example, human endometrial and decidual cells have been used to model maternal tissues (Figure 3(a)),131 while cytotrophoblast aggregates have been used to recapitulate placental development (Figure 3(b)).77,132 While in vitro fertilization has enabled the study of early embryogenesis for many years,133,134 later stages of embryonic development have recently been modeled in vitro by combining mouse embryonic and trophoblast stem cells (Figure 3(c)).135 Thus far, these organoid models have relied on tissue self-assembly within undefined mixtures of animal-derived matrices.

Figure 3.

In vitro models of the maternal–fetal interface and embryogenesis. (a) Primary endometrial cells suspended in matrigel self-organize into organoids in chemically defined medium (adapted from Turco et al.131). (b) Human trophoblast stem cells form three-dimensional syncytiotrophoblasts aggregates that produced human chorionic gonadotropin (CGB) and syndecan-1 (SDC) a trophoblast marker (adapted from Okae et al.77). (c) Mouse embryonic stem cells and extra-embryonic trophoblast stem cells create embryo-like structures in three-dimensional matrigel scaffolds (adapted from Harrison et al.135). (d) Microphysiological model of the placental barrier composed of trophoblasts and endothelial cells on a fibronectin-coated membrane, stained with E-cadherin and VE-cadherin, respectively (adapted from Blundell et al.151). (e) Microfluidic model of trophoblast invasion, with primary extravillous trophoblasts (EVTs) embedded in Matrigel between two channels that create a chemokine gradient (adapted from Abbas et al.153 under Creative Commons CC BY 4.0).

In conjunction with advances in stem cell biology, microphysiological systems, or organs on chips,136–140 have emerged as human tissue models with the potential to control and study cell–cell and cell–matrix interactions.141–146 When applied to the female reproductive tract,147 endometrial,148 placental,151 and fetal membrane149 models have provided insight into reproductive diseases,150 prenatal drug safety,152 and basic developmental biology.132 Featuring multiple cell types and continuous perfusion, these systems can quantify cellular migration, invasion, and barrier function in response to dynamic stimuli (Figure 3(d) and (e)).151,153–156

By recreating aspects of native extracellular matrix, microphysiological systems are ideal for probing the contributions of matrix cues on cellular behavior at the maternal–fetal interface.157–159 Using native tissue composition as a guide,160 experiments in microphysiological systems have demonstrated that matrix proteins including fibronectin, laminin, and collagen regulate placental and amniotic cell adhesion, morphology, differentiation, and function.159,161,162 In addition to structural proteins, matrix-binding and matrix-degrading proteins can be spatially and temporally controlled in vitro to study their effects on cell migration, invasion, and hormone secretion.163–165 Beyond protein composition, matrix stiffness can also be tuned,166 allowing co-culture of endometrial epithelial and stromal cells that require different local microenvironments,167 and generation of three dimensional models to study endometrial vascularization and trophoblast invasion.168 These studies demonstrate that microphysiological systems can be used prior to in vivo testing to elucidate the functions of extracellular matrix at the maternal–fetal interface.

Even with advances in stem cells and tissue engineering, microphysiological systems of the maternal–fetal interface have yet to realize their full potential to advance reproductive medicine. To realize this potential, microphysiological systems should incorporate and continue to study the effects of extracellular cues at the maternal–fetal interface. To inform and improve the design and accuracy of these systems, structural and mechanical properties of the womb microenvironment should also be further characterized throughout development and disease.169 As microphysiological systems move towards exclusively human tissues and matrix, minimum essential elements of the extracellular microenvironment should be identified to balance precision with scalability for clinical applications. By engineering the biotic–abiotic interface of stem cell-derived tissues to match their native counterparts, microphysiological systems of the maternal–fetal interface will provide a platform for personalized reproductive medicine.

Conclusions

The extracellular matrix coordinates cellular differentiation and morphogenesis in the womb. Though often overlooked, maladaptive extracellular matrix composition and remodeling in womb are contributing factors for obstetric complications that threaten both maternal and fetal health. To close the gap in our understanding and appreciation of the role of extracellular matrix in pregnancy, we propose to use microphysiological systems to further probe the relationship between maternal and fetal cells and their physical microenvironment. By incorporating physiologically relevant cues from the extracellular matrix, these in vitro models can be used to improve reproductive technologies and identify therapeutic interventions for obstetric diseases. We envision the knowledge gained from these systems can be used to engineer more receptive environments for assisted reproduction, to develop wound dressings to scarlessly heal surgical incisions, and to better predict prenatal drug safety, thereby improving women’s reproductive health.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Michael Rosnach for schematic design and illustrations, as well as Dan Drennan, Luke MacQueen, Dan Needleman, Suzanne Smith, and John Zimmerman for constructive feedback on the manuscript.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the design, writing, review, and editing of the manuscript.

DECLARATION OF CONFLICTING INTERESTS

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

FUNDING

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at Harvard University; the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard University; the Harvard Materials Research Science and Engineering Center [grant number DMR-1420570]; and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development [award number F31HD095594]. B. D. Pope is a Good Ventures Fellow of the Life Sciences Research Foundation. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

ORCID iD

Kevin K Parker https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5968-7535

References

- 1.Napso T, Yong HEJ, Lopez-Tello J, Sferruzzi-Perri AN. The role of placental hormones in mediating maternal adaptations to support pregnancy and lactation. Front Physiol 2018; 9:1091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knöfler M. Critical growth factors and signalling pathways controlling human trophoblast invasion. Int J Dev Biol 2010; 54:269–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muiznieks LD, Keeley FW. Molecular assembly and mechanical properties of the extracellular matrix: a fibrous protein perspective. Biochim Biophys Acta 2013; 1832:866–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yanagishita M. Function of proteoglycans in the extracellular matrix. Acta Pathol Jpn 1993; 43:283–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Piez KA. History of extracellular matrix: a personal view. Matrix Biol 1997; 16:85–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vining KH, Mooney DJ. Mechanical forces direct stem cell behaviour in development and regeneration. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2017; 18:728–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnans C, Chou J, Werb Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2014; 15:786–801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mammoto T, Ingber DE. Mechanical control of tissue and organ development. Development 2010; 137:1407–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang N, Butler JP, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science 1993; 260:1124–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lessey BA, Damjanovich L, Coutifaris C.Castelbaum A, Albelda SM, Buck CA. Integrin adhesion molecules in the human endometrium. Correlation with the normal and abnormal menstrual cycle. J Clin Invest 1992; 90:188–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pelham RJ, Wang Y-L. Cell locomotion and focal adhesions are regulated by substrate flexibility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997; 94:13661–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mouw JK, Yui Y, Damiano L, et al. Tissue mechanics modulate microRNA-dependent PTEN expression to regulate malignant progression. Nat Med 2014; 20:360–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wang N, Tytell JD, Ingber DE. Mechanotransduction at a distance: mechanically coupling the extracellular matrix with the nucleus. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2009; 10:75–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aplin JD, Jones C. Extracellular matrix in endometrium and decidua In: Genbačev O, Klopper A, Beaconsfield R. (eds) Placenta as a model and a source. Boston, MA: Springer US, 1989, pp. 115–28 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sahoo SS, Quah MY, Nielsen S, et al. Inhibition of extracellular matrix mediated TGF-ß; signalling suppresses endometrial cancer metastasis. Oncotarget 2017; 8:71400–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zbucka M, Miltyk W, Bielawski T, et al. Mechanism of collagen biosynthesis up-regulation in cultured leiomyoma cells. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 2007; 45:S181–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Malik M, Britten J, Segars J, et al. Leiomyoma cells in 3-dimensional cultures demonstrate an attenuated response to fasudil, a rho-kinase inhibitor, when compared to 2-dimensional cultures. Reprod Sci 2014; 21:1126–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brosens I, Pijnenborg R, Vercruysse L, et al. The ‘great obstetrical syndromes’ are associated with disorders of deep placentation. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204:193–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim M-S, Yu JH, Lee M-Y, et al. Differential expression of extracellular matrix and adhesion molecules in fetal-origin amniotic epithelial cells of preeclamptic pregnancy. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0156038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Timor-Tritsch IE, Monteagudo A, Cali G, et al. Cesarean scar pregnancy and early placenta accreta share common histology. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2014; 43:383–95 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jauniaux E, Silver RM, Matsubara S. The new world of placenta accreta spectrum disorders. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2018; 140:259–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox KA, Shamshirsaz AA, Carusi D, et al. Conservative management of morbidly adherent placenta: expert review. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015; 213:755–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Russell DL, Salustri A. Extracellular matrix of the cumulus-oocyte complex. Semin Reprod Med 2006; 24:217–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Familiari G, Heyn R, Relucenti M, et al. Structural changes of the zona pellucida during fertilization and embryo development. Front Biosci 2008; 13:6730–51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salustri A, Yanagishita M, Hascall VC. Synthesis and accumulation of hyaluronic acid and proteoglycans in the mouse cumulus cell-oocyte complex during follicle-stimulating hormone-induced mucification. J Biol Chem 1989; 264:13840–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Irving-Rodgers HF, Rodgers RJ. Extracellular matrix in ovarian follicular development and disease. Cell Tissue Res 2005; 322:89–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhuo L, Yoneda M, Zhao M, et al. Defect in SHAP-hyaluronan complex causes severe female infertility. A study by inactivation of the bikunin gene in mice. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:7693–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ishizuka Y, Takeo T, Nakao S, et al. Prolonged exposure to hyaluronidase decreases the fertilization and development rates of fresh and cryopreserved mouse oocytes. J Reprod Dev 2014; 60:454–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hassani F, Oryan S, Eftekhari-Yazdi P, et al. Downregulation of extracellular matrix and cell adhesion molecules in cumulus cells of infertile polycystic ovary syndrome women with and without insulin resistance. Cell J 2019; 21:35–42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang H-L, Lv C, Zhao Y-C, et al. Mutant ZP1 in familial infertility. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1220–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharkey AM, Smith SK. The endometrium as a cause of implantation failure. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 17:289–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koot YEM, Teklenburg G, Salker MS, et al. Molecular aspects of implantation failure. Biochim Biophys Acta 2012; 1822:1943–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilcox AJ, Baird DD, Weinberg CR. Time of implantation of the conceptus and loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1999; 340:1796–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wilcox AJ, Weinberg CR, O’Connor JF, et al. Incidence of early loss of pregnancy. N Engl J Med 1988; 319:189–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mancini V, Pensabene V. Organs-on-chip models of the female reproductive system. Bioengineering 2019; 6:pii: E103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aplin JD. Adhesion molecules in implantation. Rev Reprod 1997; 2:84–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zorn TT, Bevilacqua EAF, Abrahamsohn PA. Collagen remodeling during decidualization in the mouse. Cell Tissue Res 1986; 244:443–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fleming S, Bell SC. Localization of fibrillin-1 in human endometrium and decidua during the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. Hum Reprod 1997; 12:2051–2056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Winship A, Cuman C, Rainczuk K, et al. Fibulin-5 is upregulated in decidualized human endometrial stromal cells and promotes primary human extravillous trophoblast outgrowth. Placenta 2015; 36:1405–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Klemmt PAB, Carver JG, Koninckx P, et al. Endometrial cells from women with endometriosis have increased adhesion and proliferative capacity in response to extracellular matrix components: towards a mechanistic model for endometriosis progression. Hum Reprod 2007; 22:3139–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Salamonsen L, Shuster S, Stern R. Distribution of hyaluronan in human endometrium across the menstrual cycle. Cell Tissue Res 2001; 306:335–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wewer UM, Faber M, Liotta LA, et al. Immunochemical and ultrastructural assessment of the nature of the pericellular basement membrane of human decidual cells. Lab Invest 1985; 53:624–33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen C, Aplin J. Placental extracellular matrix: gene expression, deposition by placental fibroblasts and the effect of oxygen. Placenta 2003; 24:316–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amenta PS, Gay S, Vaheri A, et al. The extracellular matrix is an integrated unit: ultrastructural localization of collagen types I, III, IV, V, VI. Coll Relat Res 1986; 6:125–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tenney B. A study of the collagen of the placenta. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1935; 29:819–825 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacobson SL, Kimberly D, Thornburg K, et al. Localization of fibrillin-1 in the human term placenta. J Soc Gynecol Investig 2:686–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gauster M, Berghold VM, Moser G, et al. Fibulin-5 expression in the human placenta. Histochem Cell Biol 2011; 135:203–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Baran Ö, Tuncer M, Nergiz Y, et al. An increase of elastic tissue fibers in blood vessel walls of placental stem villi and differences in the thickness of blood vessel walls in third trimester pre-eclampsia pregnancies. Open Med 2010; 5:227–234 [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matejevic D, Neudeck H, Graf R, et al. Localization of hyaluronan with a hyaluronan-specific hyaluronic acid binding protein in the placenta in pre-eclampsia. Gynecol Obstet Invest 2001; 52:257–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Chen C-P, Liu S-H, Lee M-Y, et al. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans in the basement membranes of the human placenta and decidua. Placenta 2008; 29:309–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pulkkinen MO, Lehto M, Jalkanen M, et al. Collagen types and fibronectin in the uterine muscle of normal and hypertensive pregnant patients. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1984; 149:711–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abedin MZ, Ayad S, Weiss JB. Type V collagen: the presence of appreciable amounts of α3(V) chain in uterus. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1981; 102:1237–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rehman KS, Yin S, Mayhew BA, et al. Human myometrial adaptation to pregnancy: cDNA microarray gene expression profiling of myometrium from non-pregnant and pregnant women. Mol Hum Reprod 2003; 9:681–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Metaxa-Mariatou V, McGavigan CJ, Robertson K, et al. Elastin distribution in the myometrial and vascular smooth muscle of the human uterus. Mol Hum Reprod 2002; 8:559–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leppert PC, Yu SY. Three-dimensional structures of uterine elastic fibers: scanning electron microscopic studies. Connect Tissue Res 1991; 27:15–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jamaluddin MFB, Nagendra PB, Nahar P, et al. Proteomic analysis identifies tenascin-C expression is upregulated in uterine fibroids. Reprod Sci 2019; 26:476–486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kida H, Taga M, Minaguchi H, et al. The change in tenascin expression in mouse uterus during early pregnancy. J Assist Reprod Genet 1997; 14:44–50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.El Maradny E, Kanayama N. The role of hyaluronic acid as a mediator and regulator of cervical ripening. Hum Reprod 1997; 12:1080–1088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shynlova O, Mitchell JA, Tsampalieros A, et al. Progesterone and gravidity differentially regulate expression of extracellular matrix components in the pregnant rat myometrium. Biol Reprod 2004; 70:986–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nishinaka K, Fukuda Y. Changes in extracellular matrix materials in the uterine myometrium of rats during pregnancy and postparturition. Acta Pathol Jpn 1991; 41:122–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hjelm AM, Barchan K, Malmström A, et al. Changes of the uterine proteoglycan distribution at term pregnancy and during labour. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2002; 100:146–151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Aplin JD, Ruane PT. Embryo–epithelium interactions during implantation at a glance. J Cell Sci 2017; 130:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Constantinou PE, Morgado M, Carson DD. Transmembrane mucin expression and function in embryo implantation and placentation In: Geisert R, Bazer F. (eds) Regulation of implantation and establishment of pregnancy in mammals: tribute to 45 year anniversary of Roger V. Short’s “maternal recognition of pregnancy”, advances in anatomy, embryology and cell biology. Switzerland: Springer, Cham, 2015, pp. 51–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gellersen B, Brosens I, Brosens J. Decidualization of the human endometrium: mechanisms, functions, and clinical perspectives. Semin Reprod Med 2007; 25:445–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wewer UM, Damjanov A, Weiss J, et al. Mouse endometrial stromal cells produce basement-membrane components. Differentiation 1986; 32:49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yucha RW, Jost M, Rothstein D, et al. Quantifying the biomechanics of conception: L-selectin-mediated blastocyst implantation mechanics with engineered 'trophospheres'. Tissue Eng Part A 2014; 20:189–96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aplin JD, Charlton AK, Ayad S. An immunohistochemical study of human endometrial extracellular matrix during the menstrual cycle and first trimester of pregnancy. Cell Tissue Res 1988; 253:231–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iwahashi M, Muragaki Y, Ooshima A, et al. Alterations in distribution and composition of the extracellular matrix during decidualization of the human endometrium. J Reprod Fertil 1996; 108:147–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Burghardt RC, Burghardt JR, Taylor JD, et al. Enhanced focal adhesion assembly reflects increased mechanosensation and mechanotransduction at maternal-conceptus interface and uterine wall during ovine pregnancy. Reproduction 2009; 137:567–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fässler R, Meyer M. Consequences of lack of beta 1 integrin gene expression in mice. Genes Dev 1995; 9:1896–908 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Illera MJ, Cullinan E, Gui Y, et al. Blockade of the alpha(v)beta(3) integrin adversely affects implantation in the mouse. Biol Reprod 2000; 62:1285–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Illera MJ, Lorenzo PL, Gui Y-T, et al. A role for alphavbeta3 integrin during implantation in the rabbit model. Biol Reprod 2003; 68:766–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Burney RO, Talbi S, Hamilton AE, et al. Gene expression analysis of endometrium reveals progesterone resistance and candidate susceptibility genes in women with endometriosis. Endocrinology 2007; 148:3814–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim TH, Yoo JY, Choi KC, et al. Loss of HDAC3 results in nonreceptive endometrium and female infertility. Sci Transl Med 2019; 11:pii:eaaf7533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bruner-Tran KL, Eisenberg E, Yeaman GR, et al. Steroid and cytokine regulation of matrix metalloproteinase expression in endometriosis and the establishment of experimental endometriosis in nude mice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2002; 87:4782–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh H, Aplin JD. Adhesion molecules in endometrial epithelium: tissue integrity and embryo implantation. J Anat 2009; 215:3–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Okae H, Toh H, Sato T, et al. Derivation of human trophoblast stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2018; 22:50–63.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Oefner CM, Sharkey A, Gardner L, et al. Collagen type IV at the fetal-maternal interface. Placenta 2015; 36:59–68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Zhou Y, Genbacev O, Fisher SJ. The human placenta remodels the uterus by using a combination of molecules that govern vasculogenesis or leukocyte extravasation. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2003; 995:73–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ji L, Brkić J, Liu M, et al. Placental trophoblast cell differentiation: physiological regulation and pathological relevance to preeclampsia. Mol Aspects Med 2013; 34:981–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tapia-Pizarro A, Argandona F, Palomino WA, et al. Human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) modulation of TIMP1 secretion by human endometrial stromal cells facilitates extravillous trophoblast invasion in vitro. Hum Reprod 2013; 28:2215–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kessenbrock K, Plaks V, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases: regulators of the tumor microenvironment. Cell 2010; 141:52–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang X, Miller DC, Harman R, et al. Paternally expressed genes predominate in the placenta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:10705–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fowden AL, Coan PM, Angiolini E, et al. Imprinted genes and the epigenetic regulation of placental phenotype. Prog Biophys Mol Biol 2011; 106:281–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Romero R, Dey SK, Fisher SJ. Preterm labor: one syndrome, many causes. Science 2014; 345:760–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Librach CL, Werb Z, Fitzgerald ML, et al. 92-kD type IV collagenase mediates invasion of human cytotrophoblasts. J Cell Biol 1991; 113:437–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Genbacev O, Zhou Y, Ludlow JW, et al. Regulation of human placental development by oxygen tension. Science 1997; 277:1669–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Damsky CH, Fitzgerald ML, Fisher SJ. Distribution patterns of extracellular matrix components and adhesion receptors are intricately modulated during first trimester cytotrophoblast differentiation along the invasive pathway, in vivo. J Clin Invest 1992; 89:210–22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Plaks V, Rinkenberger J, Dai J, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deficiency phenocopies features of preeclampsia and intrauterine growth restriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2013; 110:11109–14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Lian IA, Toft JH, Olsen GD, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase 1 in pre-eclampsia and fetal growth restriction: reduced gene expression in decidual tissue and protein expression in extravillous trophoblasts. Placenta 2010; 31:615–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Perez-Garcia V, Fineberg E, Wilson R, et al. Placentation defects are highly prevalent in embryonic lethal mouse mutants. Nature 2018; 555:463–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Martinez-Fierro ML, Hernández-Delgadillo GP, Flores-Morales V, et al. Current model systems for the study of preeclampsia. Exp Biol Med 2018; 243:576–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Boyd PA, Scott A. Quantitative structural studies on human placentas associated with pre-eclampsia, essential hypertension and intrauterine growth retardation. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1985; 92:714–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lyall F, Robson SC, Bulmer JN. Spiral artery remodeling and trophoblast invasion in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction: relationship to clinical outcome. Hypertens 2013; 62:1046–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Romão M, Weel IC, Lifshitz SJ, et al. Elevated hyaluronan and extracellular matrix metalloproteinase inducer levels in women with preeclampsia. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2014; 289:575–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Vettraino IM, Roby J, Tolley T, et al. Collagenase-I, stromelysin-I, and matrilysin are expressed within the placenta during multiple stages of human pregnancy. Placenta 1996; 17:557–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Hunninghake G, Davidson J, Renard S, et al. Elastin fragments attract macrophage precursors to diseased sites in pulmonary emphysema. Science 1981; 212:925–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Steadman R Irwin MH, St John PL, et al. Laminin cleavage by activated human neutrophils yields proteolytic fragments with selective migratory properties. J Leukoc Biol 1993; 53:354–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Ilekis JV, Tsilou E, Fisher S, et al. Placental origins of adverse pregnancy outcomes: potential molecular targets: an executive workshop summary of the eunice kennedy shriver national institute of child health and human development. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2016; 215:S1–S46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kocarslan S, Incebıyık A, Guldur ME, et al. What is the role of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in placenta percreta? J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2015; 41:1018–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.DaSilva-Arnold SC, Zamudio S, Al-Khan A, et al. Human trophoblast epithelial-mesenchymal transition in abnormally invasive placenta. Biol Reprod 2018; 99:409–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Silver RM, Landon MB, Rouse DJ, et al. Maternal morbidity associated with multiple repeat cesarean deliveries. Obstet Gynecol 2006; 107:1226–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Roeder HA, Cramer SF, Leppert PC. A look at uterine wound healing through a histopathological study of uterine scars. Reprod Sci 2012; 19:463–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kuo CY, Baker H, Fries MH, et al. Bioengineering strategies to treat female infertility. Tissue Eng Part B Rev 2017; 23:294–306 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Song T, Zhao X, Sun H, et al. Regeneration of uterine horns in rats using collagen scaffolds loaded with human embryonic stem cell-derived endometrium-like cells. Tissue Eng Part A 2015; 21:353–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ding L, Li X, Sun H, et al. Transplantation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells on collagen scaffolds for the functional regeneration of injured rat uterus. Biomaterials 2014; 35:4888–900 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Ramsey EM. Anatomy of the human uterus. In: Chard T, Grudzinskas JG (eds). Uterus. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1994; pp. 18–40 [Google Scholar]

- 108.Myers KM, Elad D. Biomechanics of the human uterus. Wires Syst Biol Med 2017; 9:e1388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lombardi A, Makieva S, Rinaldi SF, et al. Expression of matrix metalloproteinases in the mouse uterus and human myometrium during pregnancy, labor, and preterm labor. Reprod Sci 2018; 25:938–49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Walsh SW, Nugent WH, Solotskaya AV, et al. Matrix metalloprotease-1 and elastase are novel uterotonic agents acting through protease-activated receptor 1. Reprod Sci 2018; 25:1058–66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Nallasamy S, Yoshida K, Akins M, et al. Steroid hormones are key modulators of tissue mechanical function via regulation of collagen and elastic fibers. Endocrinology 2017; 158:950–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pezaro S, Pearce G, Reinhold E. Hypermobile Ehlers-Danlos syndrome during pregnancy, birth and beyond. Br J Midwifery 2018; 26:217–23 [Google Scholar]

- 113.Murray ML, Pepin M, Peterson S, et al. Pregnancy-related deaths and complications in women with vascular Ehlers–Danlos syndrome. Genet Med 2014; 16:874–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Hermanns-Lê T, Piérard GE. Skin ultrastructural clues on the impact of Ehlers-Danlos syndrome in women. J Dermatological Res 2016; 1:34–40 [Google Scholar]

- 115.Alamo L, Vial Y, Denys A, et al. MRI findings of complications related to previous uterine scars. Eur J Radiol Open 2018; 5:6–15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Antila-Långsjö RM, Mäenpää JU, Huhtala HS, et al. Cesarean scar defect: a prospective study on risk factors. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018; 219:458.e1-458–e8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Landon MB, Hauth JC, Leveno KJ, et al. Maternal and perinatal outcomes associated with a trial of labor after prior cesarean delivery. N Engl J Med 2004; 351:2581–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Motomura K, Ganchimeg T, Nagata C, et al. Incidence and outcomes of uterine rupture among women with prior caesarean section: WHO multicountry survey on maternal and newborn health. Sci Rep 2017; 7:44093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Buhimschi CS, Zhao G, Sora N, et al. Myometrial wound healing post-Cesarean delivery in the MRL/MpJ mouse model of uterine scarring. Am J Pathol 2010; 177:197–207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Shynlova O, Kwong R, Lye SJ. Mechanical stretch regulates hypertrophic phenotype of the myometrium during pregnancy. Reproduction 2010; 139:247–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Shynlova O, Williams SJ, Draper H, et al. Uterine stretch regulates temporal and spatial expression of fibronectin protein and its alpha 5 integrin receptor in myometrium of unilaterally pregnant rats. Biol Reprod 2007; 77:880–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Garfield RE, Maner WL. Physiology and electrical activity of uterine contractions. Semin Cell Dev Biol 2007; 18:289–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Zhou D, Lee HS, Villarreal F, et al. Differential MMP-2 activity of ligament cells under mechanical stretch injury: an in vitro study on human ACL and MCL fibroblasts. J Orthop Res 2005; 23:949–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Strauss JF., III, Extracellular matrix dynamics and fetal membrane rupture. Reprod Sci 2013; 20:140–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.de Laat MWM, Pieper PG, Oudijk MA, et al. The clinical and molecular relations between idiopathic preterm labor and maternal congenital heart defects. Reprod Sci 2013; 20:190–201 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Turton P, Arrowsmith S, Prescott J, et al. A comparison of the contractile properties of myometrium from singleton and twin pregnancies. PLoS One 2013; 8:e63800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Biggio JR, Anderson S. Spontaneous preterm birth in multiples. Clin Obstet Gynecol 2015; 58:654–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Challis JRG, Sloboda DM, Alfaidy N, et al. Prostaglandins and mechanisms of preterm birth. Reproduction 2002; 124:1–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Kobayashi H, Kawahara N, Ogawa K, et al. A relationship between endometriosis and obstetric complications. Reprod Sci 2020;1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Gundling WE, Wildman DE. A review of inter- and intraspecific variation in the eutherian placenta. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2015; 370:20140072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Turco MY, Gardner L, Hughes J, et al. Long-term, hormone-responsive organoid cultures of human endometrium in a chemically defined medium. Nat Cell Biol 2017; 19:568–577 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Haider S, Meinhardt G, Saleh L, et al. Self-renewing trophoblast organoids recapitulate the developmental program of the early human placenta. Stem Cell Rep 2018; 11:537–551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Edwards RG, Bavister BD, Steptoe PC. Early stages of fertilization in vitro of human oocytes matured in vitro. Nature 1969; 221:632–635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Edwards RG, Steptoe PC, Purdy JM. Fertilization and cleavage in vitro of preovulator human oocytes. Nature 1970; 227:1307–1309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Harrison SE, Sozen B, Christodoulou N, et al. Assembly of embryonic and extraembryonic stem cells to mimic embryogenesis in vitro. Science 2017; 356:pii:eaal1810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Lind JU, Busbee TA, Valentine AD, et al. Instrumented cardiac microphysiological devices via multimaterial three-dimensional printing. Nat Mater 2017; 16:303–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Herland A, van der Meer AD, FitzGerald EA, et al. Distinct contributions of astrocytes and pericytes to neuroinflammation identified in a 3D human blood-brain barrier on a chip. PLoS One 2016; 11:e0150360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Glieberman AL, Pope BD, Zimmerman JF, et al. Synchronized stimulation and continuous insulin sensing in a microfluidic human islet on a chip designed for scalable manufacturing. Lab Chip 2019; 19:2993–3010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Nesmith AP, Wagner MA, Pasqualini FS, et al. A human in vitro model of duchenne muscular dystrophy muscle formation and contractility. J Cell Biol 2016; 215:47–56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Alford PW, Nesmith AP, Seywerd JN, et al. Vascular smooth muscle contractility depends on cell shape. Integr Biol 2011; 3:1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Angelini TE, Hannezo E, Trepat X, et al. Glass-like dynamics of collective cell migration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2011; 108:4714–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Bhatia SN, Ingber DE. Microfluidic organs-on-chips. Nat Biotechnol 2014; 32:760–772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Benam KH, Dauth S, Hassell B, et al. Engineered in vitro disease models. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Pathol 2015; 10:195–262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wikswo JP. The relevance and potential roles of microphysiological systems in biology and medicine. Exp Biol Med 2014; 239:1061–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Maoz BM, Herland A, FitzGerald EA, et al. A linked organ-on-chip model of the human neurovascular unit reveals the metabolic coupling of endothelial and neuronal cells. Nat Biotechnol 2018; 36:865–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Novak R, Ingram M, Marquez S, et al. Robotic fluidic coupling and interrogation of multiple vascularized organ chips. Nat Biomed Eng 2020; 4:407–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Young AN, Moyle-Heyrman G, Kim JJ, et al. Microphysiologic systems in female reproductive biology. Exp Biol Med 2017; 242:1690–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Weimar CHE, Post Uiterweer ED, Teklenburg G, et al. In-vitro model systems for the study of human embryo-endometrium interactions. Reprod Biomed Online 2013; 27:461–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Richardson L, Gnecco J, Ding T, et al. Fetal membrane organ-on-chip: an innovative approach to study cellular interactions. Reprod Sci 2019. doi: 10.1177/1933719119828084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Zhu Y, Yin F, Wang H, et al. Placental barrier-on-a-chip: modeling placental inflammatory responses to bacterial infection. ACS Biomater Sci Eng 2018; 4:3356–3363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Blundell C, Tess ER, Schanzer ASR, et al. A microphysiological model of the human placental barrier. 2016; 16:3065–73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Blundell C, Yi Y-S, Ma L, et al. Placental drug transport-on-a-chip: a microengineered in vitro model of transporter-mediated drug efflux in the human placental barrier. Adv Healthcare Mater 2018; 7:1700786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Abbas Y, Oefner CM, Polacheck WJ, et al. A microfluidics assay to study invasion of human placental trophoblast cells. J R Soc Interface 2017; 14:pii:20170131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Lee JS, Romero R, Han YM, et al. Placenta-on-a-chip: a novel platform to study the biology of the human placenta. J Matern Neonatal Med 2016; 29:1046–1054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Gnecco JS, Ding T, Smith C, et al. Hemodynamic forces enhance decidualization via endothelial-derived prostaglandin E2 and prostacyclin in a microfluidic model of the human endometrium. Hum Reprod 2019; 34:702–714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Gnecco JS, Pensabene V, Li DJ, et al. Compartmentalized culture of perivascular stroma and endothelial cells in a microfluidic model of the human endometrium. Ann Biomed Eng 2017; 45:1758–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Shao Y, Taniguchi K, Gurdziel K, et al. Self-organized amniogenesis by human pluripotent stem cells in a biomimetic implantation-like niche. Nat Mater 2017; 16:419–425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Ma Z, Sagrillo-Fagundes L, Tran R, et al. Biomimetic micropatterned adhesive surfaces to mechanobiologically regulate placental trophoblast fusion. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 2019; 11:47810–47821 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Wong MK, Shawky SA, Aryasomayajula A, et al. Extracellular matrix surface regulates self-assembly of three-dimensional placental trophoblast spheroids. PLoS One 2018; 13:e0199632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Gnecco JS, Anders AP, Cliffel D, et al. Instrumenting a fetal membrane on a chip as emerging technology for preterm birth research. Curr Pharm Des 2017; 23:6115–6124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Kilburn BA, Wang J, Duniec-Dmuchkowski ZM, et al. Extracellular matrix composition and hypoxia regulate the expression of HLA-G and integrins in a human trophoblast cell line. Biol Reprod 2000; 62:739–747 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Richardson L, Jeong S, Kim S, et al. Amnion membrane organ-on-chip: an innovative approach to study cellular interactions. FASEB J 2019; 33:8945–8960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Klaffky EJ, Gonzáles IM, Sutherland AE. Trophoblast cells exhibit differential responses to laminin isoforms. Dev Biol 2006; 292:277–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Castellucci M, Kaufmann P, Bischof P. Extracellular matrix influences hormone and protein production by human chorionic villi. Cell Tissue Res 1990; 262:135–142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Desforges M, Harris LK, Aplin JD. Elastin-derived peptides stimulate trophoblast migration and invasion: a positive feedback loop to enhance spiral artery remodelling. Mol Hum Reprod 2015; 21:95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Grevesse T, Versaevel M, Circelli G, et al. A simple route to functionalize polyacrylamide hydrogels for the independent tuning of mechanotransduction cues. Lab Chip 2013; 13:777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Cook CD, Hill AS, Guo M, et al. Local remodeling of synthetic extracellular matrix microenvironments by co-cultured endometrial epithelial and stromal cells enables long-term dynamic physiological function. Integr Biol 2017; 9:271–289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Zambuto SG, Clancy KBH, Harley B. A gelatin hydrogel to study endometrial angiogenesis and trophoblast invasion. Interf Focus 2019; 9:20190016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Abbas Y, Carnicer-Lombarte A, Gardner L, et al. Tissue stiffness at the human maternal–fetal interface. Hum Reprod 2019; 34:1999–2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]