A widely conserved but noncatalytic starch synthase-like protein interacts with the known granule-initiating factor MRC and regulates the number of starch granules formed in chloroplasts.

Abstract

What determines the number of starch granules in plastids is an enigmatic aspect of starch metabolism. Several structurally and functionally diverse proteins have been implicated in the granule initiation process in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), with each protein exerting a varying degree of influence. Here, we show that a conserved starch synthase-like protein, STARCH SYNTHASE5 (SS5), regulates the number of starch granules that form in Arabidopsis chloroplasts. Among the starch synthases, SS5 is most closely related to SS4, a major determinant of granule initiation and morphology. However, unlike SS4 and the other starch synthases, SS5 is a noncanonical isoform that lacks catalytic glycosyltransferase activity. Nevertheless, loss of SS5 reduces starch granule numbers that form per chloroplast in Arabidopsis, and ss5 mutant starch granules are larger than wild-type granules. Like SS4, SS5 has a conserved putative surface binding site for glucans and also interacts with MYOSIN-RESEMBLING CHLOROPLAST PROTEIN, a proposed structural protein influential in starch granule initiation. Phenotypic analysis of a suite of double mutants lacking both SS5 and other proteins implicated in starch granule initiation allows us to propose how SS5 may act in this process.

INTRODUCTION

Green plants and algae produce transitory starch as a temporary storage compound that provides energy during phases of darkness that would otherwise result in deleterious energy starvation (Stitt and Zeeman, 2012). As a dense, compact, and osmotically inert carbohydrate polymer, starch allows the efficient storage of photoassimilates directly within the chloroplast. Transitory starch takes the form of discrete, lenticular (discoid) granules that occur between the thylakoid membranes (Streb and Zeeman, 2012). In Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) leaves, chloroplasts reportedly contain five to seven granules, a number that was shown to be correlated with chloroplast volume (i.e., larger chloroplasts have more starch granules; Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2012). The situation is different in starch-containing storage organs, where different types or populations of starch granules have been described. Some amyloplasts (e.g., in potato [Solanum tuberosum] tubers) are reported to contain just one simple granule (Ohad et al., 1971), whereas other amyloplasts (e.g., in rice [Oryza sativa]) initiate multiple granules that grow together to form compound granules (Matsushima et al., 2010; Toyosawa et al., 2016). In other cases, such as in wheat (Triticum aestivum) or barley (Hordeum vulgare), amyloplasts contain distinct populations of large and small granules that are initiated at different times (Tomlinson and Denyer, 2003).

Starch consists of glucose units that are condensed into two distinct polysaccharides—amylopectin and amylose—by ⍺-1,4- and ⍺-1,6-glycosidic linkages. The predominant component, amylopectin, has ⍺-1,4-linked glucan chains connected by ⍺-1,6 bonds to form a branched molecule with a tree-like (racemose) structure that contains clusters of unbranched chain segments. Neighboring linear chain segments within clusters form double helices that pack tightly into crystalline lamellae. These crystalline lamellae alternate with amorphous lamellae, which contain the branched chain segments connecting the clusters (Streb and Zeeman, 2012). Amylose, a minor component of starch and a mostly linear glucan made from ⍺-1,4-linked glucose units, is thought to be synthesized within the amorphous lamellae (Denyer et al., 2001). Amylose is not strictly required for the formation of starch granules, but it may increase the efficiency of glucan storage by occupying residual space in the semicrystalline amylopectin matrix.

Three enzyme classes are needed to make branched, crystallization-competent amylopectin. First, starch synthases (SSs) elongate glucan chains by catalyzing the formation of ⍺-1,4-glycosidic bonds using ADP-glucose (ADP-Glc) as a glucosyl donor. Second, branching enzymes introduce ⍺-1,6-glycosidic linkages by catalyzing glucanotransferase reactions. Third, and less intuitively, debranching enzymes hydrolyze some of the ⍺-1,6 branch points introduced by branching enzymes, and this is thought to promote crystallization by refining the branching pattern (Streb and Zeeman, 2012). Plants possess genes encoding multiple isoforms of SSs, branching enzymes, and debranching enzymes, and these isoforms have distinct roles in amylopectin synthesis. For example, in Arabidopsis, six genes are described as encoding SSs. Four isoforms (SS1 to SS4) have been implicated in amylopectin biogenesis (Delvallé et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2005; Roldán et al., 2007; Zhang et al., 2008) and are thought to be active at the granule surface. The fifth isoform, granule-bound starch synthase (GBSS), is responsible for amylose production (Denyer et al., 2001). The last isoform, SS5, has not been assigned a specific function, which is likely due to its very unusual features (Liu et al., 2015; Helle et al., 2018; Qu et al., 2018).

At the protein level, the canonical SSs (SS1 to SS4 and GBSS) share a conserved catalytic domain. They are glycosyltransferases (GTs) with a GT-B fold (Carbohydrate Active Enzymes database; Lombard et al., 2014), meaning that their structure consists of two similar Rossmann-like subdomains that are connected via a hinge region. It is proposed that the N-terminal subdomain binds the acceptor substrate and the C-terminal subdomain binds the donor substrate; the active site is thus formed between the two (Qasba et al., 2005; Sheng et al., 2009a). Based on amino acid sequence similarity, GTs have been further classified into 109 GT families in the Carbohydrate Active Enzymes database. Both ADP-Glc-utilizing bacterial glycogen synthases and plant starch synthases are assigned to GT family 5 (http://www.cazy.org/), and their N-terminal and C-terminal subdomains are denoted as GT5 and GT1 subdomains, respectively.

Despite the similarities in their catalytic domains, plant SS isoforms differ significantly at their N termini, which are variable in length and contain either no conserved predicted domains (GBSS and SS1), predicted coiled-coil motifs (SS4 and some SS2 orthologs), or both coiled-coil motifs and carbohydrate binding modules (CBMs; in the case of SS3, three CBMs of family 53). At the enzymatic level, SSs seem to differ mostly in their acceptor substrate preferences. The loss of individual SS1, SS2, or SS3 isoforms results in characteristic changes in the amylopectin fine structure (Pfister and Zeeman, 2016). A special role has been assigned to SS4, however. In Arabidopsis, this isoform strongly influences both the numbers and morphology of starch granules produced. Rather than forming five to seven discoid starch granules, chloroplasts from Arabidopsis ss4 mutants contain far fewer granules that are nearly spherical rather than discoid, and many chloroplasts fail to produce any granules at all (Roldán et al., 2007; Szydlowski et al., 2009). This starch granule phenotype is accompanied by a substantial accumulation of ADP-Glc and mild chlorosis, which probably results from a deleterious shortage of adenylates for photosynthesis (Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2013; Ragel et al., 2013). These observations have led to the hypothesis that SS4 is a key factor in starch granule initiation. Consistent with this hypothesis, the partial loss of function of SS4 in wheat has similar effects on the numbers of granules formed in leaves (Guo et al., 2017).

Recent research has identified additional proteins that influence starch granule initiation in Arabidopsis (Seung et al., 2017, 2018; Vandromme et al., 2019). First, PROTEIN TARGETING TO STARCH2 (PTST2), a protein containing predicted coiled-coil motifs and a family 48 CBM, has been shown to work with SS4 in the granule initiation process. PTST2 is proposed to interact with and provide SS4 with appropriate oligosaccharide primers (Seung et al., 2017). The loss of PTST2 leads to a reduction in starch granule numbers per chloroplast, a phenotype exacerbated by the additional loss of its homolog, PTST3, with which it also interacts. PTST2 also interacts with MAR BINDING FILAMENT-LIKE PROTEIN1 (MFP1) and MYOSIN-RESEMBLING CHLOROPLAST PROTEIN (MRC), also called PROTEIN INVOLVED IN STARCH INITIATION1, two proteins containing extensive predicted coiled-coil motifs. Both MFP1 and MRC influence the number of starch granules formed per chloroplast, with mfp1 and mrc mutants having low numbers of granules compared with wild-type plants (Seung et al., 2018; Vandromme et al., 2019). MRC further directly interacts with SS4 (Vandromme et al., 2019). At present, the mechanism(s) by which this network of interacting proteins function together to control granule initiation is not well understood, nor is it known whether this protein network is complete. Here, we demonstrate that the starch synthase-like protein, SS5, also influences the numbers of starch granules that form in chloroplasts. SS5 is widely conserved across the plant kingdom and most closely related to SS4. Yet, unlike the other starch synthases, SS5 lacks the C-terminal GT1 subdomain that has been proposed to bind the donor substrate and is unlikely to function as a canonical starch synthase. We show that SS5 interacts with MRC and propose that it serves to regulate other components of the starch granule initiation network.

RESULTS

Arabidopsis SS5 Is a Conserved Noncanonical Starch Synthase with Unique Features

The canonical starch synthases SS1 to SS4 are highly conserved in plants (Pfister and Zeeman, 2016). The presence of SS5 has also been reported in several plant species, and, although bioinformatic analyses have indicated intriguing features (Liu et al., 2015; Helle et al., 2018; Qu et al., 2018), its function is unclear. To clarify this, we first used the protein sequences of the soluble Arabidopsis starch synthases (SS1 to SS5) as queries to isolate possible orthologous sequences and create a phylogenetic tree (Supplemental Figure 1). In accordance with previous observations (Liu et al., 2015; Helle et al., 2018), a number of the retrieved protein sequences clustered together with At-SS5 (ABJ17089.1) into a separate SS5 clade (including the rice SS5 protein, Os-SS5; XP 015626202.1) that was most closely related to the group of SS4 proteins, confirming that SS5 proteins are evolutionarily conserved. Despite the generally broad phylogenetic representation of SS5 proteins, we noticed the apparent absence of SS5 in Brachypodium distachyon. We further failed to identify SS5 orthologs in the genomes of wheat and barley, suggesting a relatively recent gene loss within the Pooideae.

We next explored the features of the isolated SS5 proteins using bioinformatics and in vivo and in vitro assays. Consistent with a putative role in starch metabolism, the algorithm TargetP (Emanuelsson et al., 2000) predicted a chloroplast transit peptide at the N terminus of the At-SS5 protein (Figure 1A). To verify its plastidial localization in vivo, we cloned and stably expressed in wild-type Arabidopsis plants an mCitrine-tagged version of the At-SS5 protein. We used a construct based on the genomic sequence of AT5G65685, including ∼1.7 kb of upstream sequence containing the putative endogenous SS5 promoter (At-SS5pro), the 5′ untranslated region (UTR), and the complete intron-exon structure. Confocal laser scanning microscopy of those lines confirmed that At-SS5-mCitrine localized to the chloroplast (Figure 1B), a feature that is likely common to SS5 proteins because most have a predicted transit peptide. Interestingly, we observed that At-SS5-mCitrine accumulated mostly in specific subchloroplastic locations, the nature of which we could not conclusively determine.

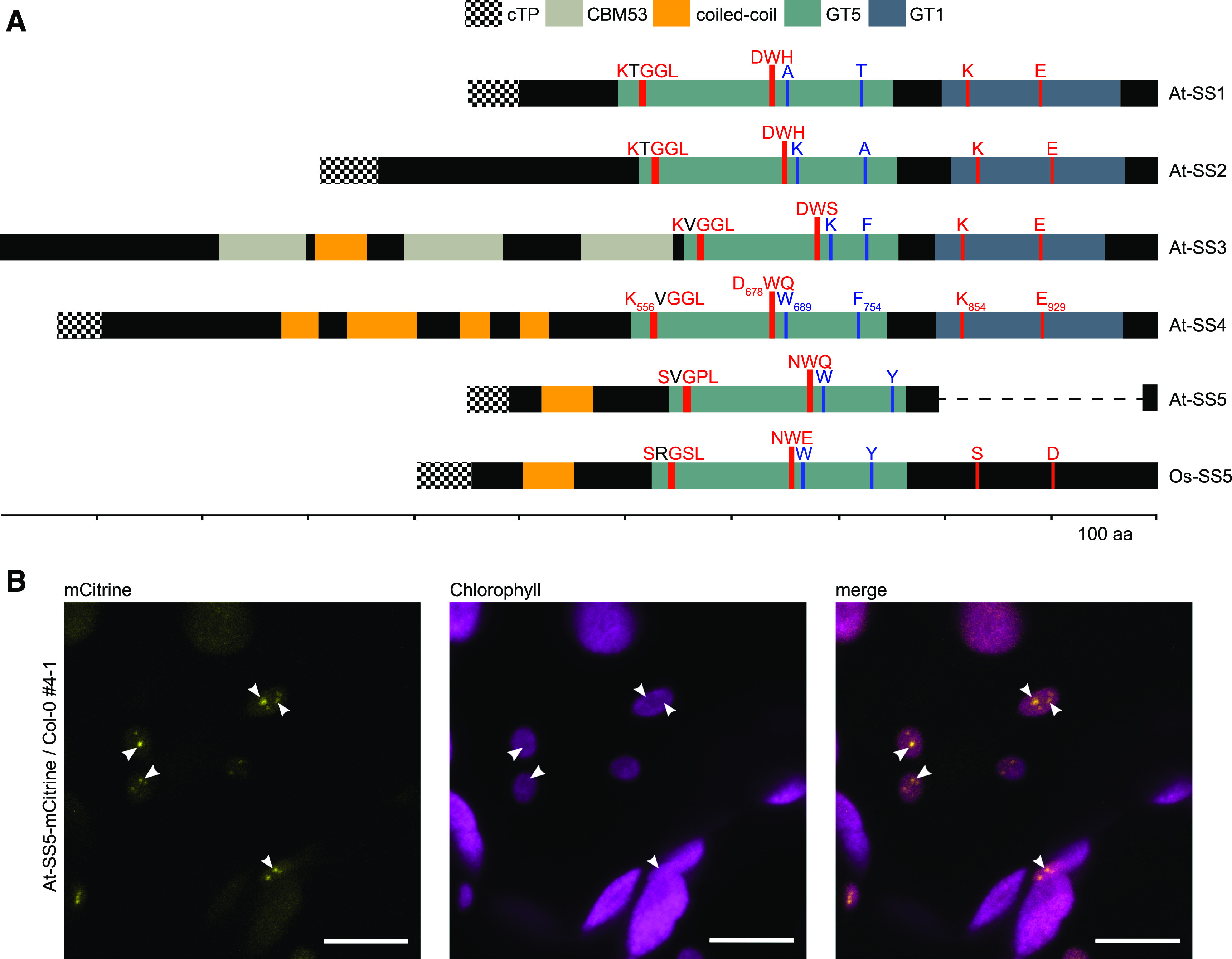

Figure 1.

SS5 Proteins Differ Substantially from the Canonical Starch Synthases but Localize to the Chloroplast.

(A) Protein domain organization of the Arabidopsis soluble starch synthases SS1 to SS5. Note that the transit peptide (cTP) of SS3 is not predicted for the splice form resulting from the longest transcript. The rice SS5 ortholog (Os-SS5) is included because the At-SS5 structure is not representative of the majority of SS5 proteins. The dashed line in At-SS5 indicates the C-terminal deletion relative to the rice ortholog. Locations of amino acid residues and motifs mentioned in the text and Supplemental Figures 3A and 3D are highlighted in red (conserved in all canonical starch synthases) and blue (SS4-specific). Residue identities in each starch synthase isoform are specified. aa, amino acids.

(B) Fluorescence images of representative leaf epidermal cells of a transgenic Arabidopsis plant expressing mCitrine-tagged At-SS5 under the control of the endogenous promoter. The images are orthogonal projections of several single images acquired in the Z plane. At-SS5-mCitrine adopts a punctate localization pattern (highlighted with white arrowheads). Bars = 10 μm.

The Arabidopsis SS5 gene has been reported to be truncated relative to its orthologs (Pfister and Zeeman, 2016; Helle et al., 2018). Our analysis confirmed that this is due to a deletion of the sequence corresponding to the C-terminal GT1 subdomain of the canonical starch synthases, a feature also observed in close Brassicaceae relatives of Arabidopsis (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 2A). While other SS5 proteins also displayed distinct truncations (e.g., from Glycine max and Amborella trichopoda; together with At-SS5 hereafter referred to as truncated SS5 proteins), most orthologs featured a C-terminal region that is likely derived from, but not predicted to be, a GT1 subdomain (Supplemental Figure 2A; Supplemental Data Set 1). In accordance with previous observations, we will refer to this region as the GT1-like subdomain (Liu et al., 2015) and to SS5 proteins carrying a GT1-like subdomain as nontruncated SS5 proteins. Whether truncated or not, all SS5 proteins that we isolated were consistently predicted to feature a GT5 subdomain (Supplemental Data Set 1).

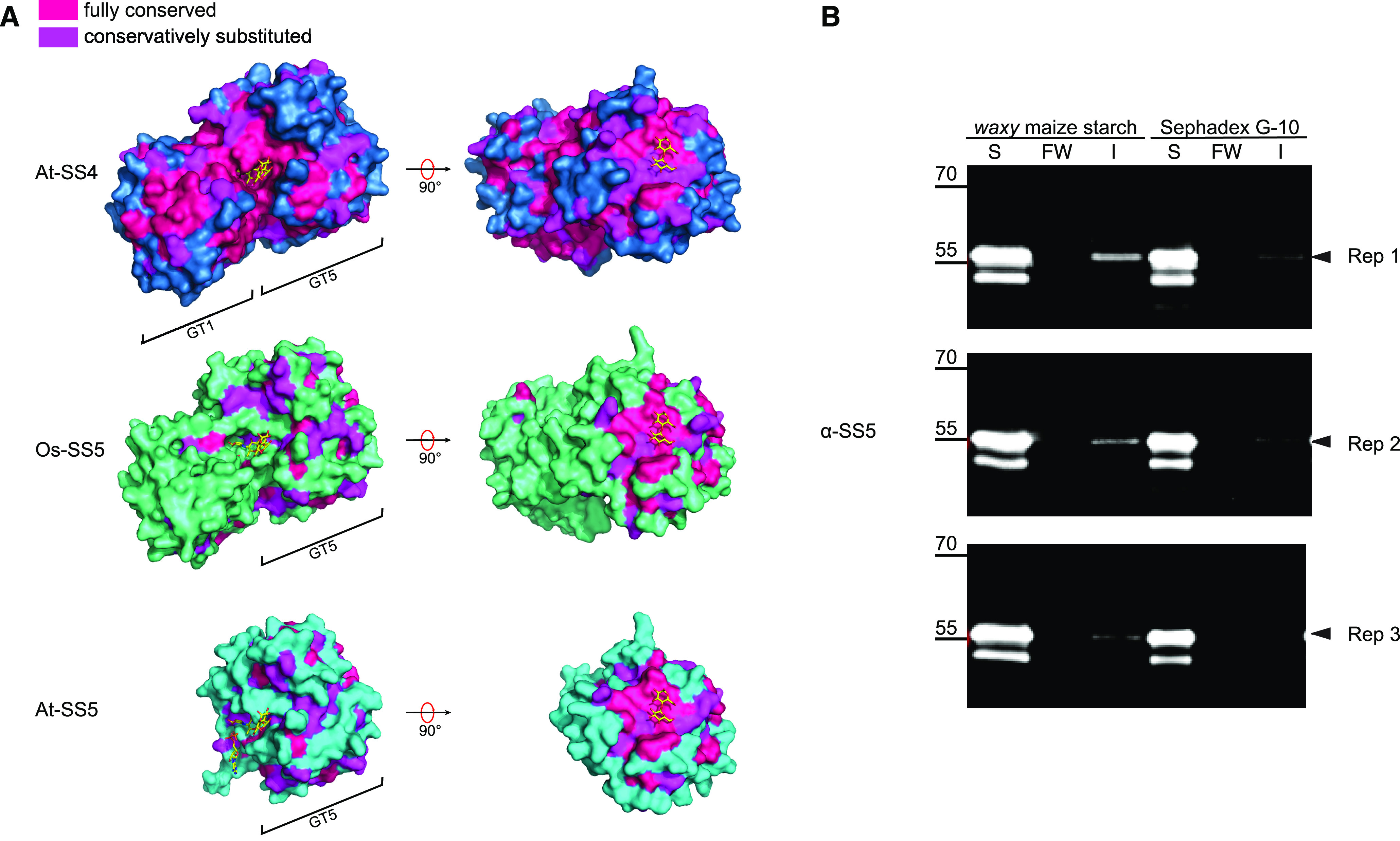

We next used the recently published crystal structure of the GT domain of At-SS4 (Nielsen et al., 2018) to explore structural features of SS5. The catalytic domain of At-SS4 adopts the classical GT-B-type fold, with the active site in the cleft between the two Rossmann-like subdomains involving residues from both subdomains (Nielsen et al., 2018). We used this structure as a template to model structures of both At-SS5 and Os-SS5 as representatives of truncated and nontruncated SS5 proteins, respectively. The modeled sequence of At-SS5 (corresponding to 257 amino acids covering the entire predicted At-SS5 GT5 subdomain) overlapped well with the N-terminal Rossmann-like subdomain of At-SS4, as expected. The Os-SS5 model covered the entire catalytic domain of At-SS4 (Supplemental Figure 2B). In order to identify protein regions that might be relevant to the respective starch synthase isoforms’ function, we mapped residues that were conserved or conservatively substituted onto the protein structures—either within all analyzed SS4 orthologs (for At-SS4), all SS5 orthologs (for At-SS5), or the nontruncated SS5 orthologs (for Os-SS5). This approach showed strong conservation of the GT1 subdomain of SS4 orthologs. However, the equivalent sequence in nontruncated SS5 orthologs was poorly conserved (Figure 2A). As expected, the catalytic cleft between the N- and C-terminal subdomains was strongly conserved in SS4. Again, this was not the case for SS5, irrespective of whether the protein was C-terminally truncated or not (Figure 2A).

Figure 2.

SS5 Shares a Putative Surface Carbohydrate Binding Site with SS4.

(A) Surface amino acid conservation in SS4 and SS5. The resolved crystal structure of the catalytic domain of At-SS4 (dark blue; Nielsen et al., 2018) was used to model corresponding three-dimensional structures of At-SS5 (cyan) and Os-SS5 (green). Amino acid conservation deduced from multiple sequence alignments of orthologs for each respective isoform was superimposed on the resulting models. The modeled structures are shown with ADP and acarbose (a glucosidase inhibitor used as an acceptor mimic; Nielsen et al., 2018) as ligands and maltose as a generic glucan at the surface binding site (carbon, oxygen, nitrogen, and phosphate atoms in yellow, red, blue, and orange, respectively) shown in the same position for Os-SS5 and At-SS5 as for At-SS4.

(B) Carbohydrate binding of recombinant polyhistidine-tagged At-SS5. S, soluble; FW, final wash, I, insoluble; Rep 1 to Rep 3, replicates. The immunoblot shows that some At-SS5 protein (black arrowheads) is detectable in the insoluble fraction when using maize starch as a binding reagent (variable levels, between 3 and 9% of the respective soluble portion). Note that some protein was detected in the insoluble fraction also when using cross-linked dextran beads (Sephadex G-10) as a nonstarch polymer. Further note the presence of a prominent double band, which is likely due to partial loss of the polyhistidine tag, in the soluble fraction.

These findings all suggest that SS5 lacks a functional catalytic domain and is unlikely to be an active GT. This is supported by the analysis of the conservation of key amino acids and amino acid motifs. Both bacterial glycogen synthases and starch synthases share a KXGGL motif in their GT5 subdomains (Figure 1A). Although the exact role of this motif is not entirely clear (Furukawa et al., 1993; Gao et al., 2004), it is stringently conserved in all canonical starch synthases, indicating a vital influence on enzymatic function. This motif is not conserved in SS5 isoforms (Supplemental Figure 3A). Similarly, two conserved residues located in the GT1 subdomain in canonical starch and glycogen synthases (K854 and E929 in At-SS4, corresponding to K305 and E377 in Escherichia coli GS, respectively), suggested to be essential for catalysis (Sheng et al., 2009b), are not conserved in SS5 isoforms, being either absent (in At-SS5) or substituted (in nontruncated orthologs; Supplemental Figure 3A). In SS4, these residues interact with ADP and acarbose (Nielsen et al., 2018).

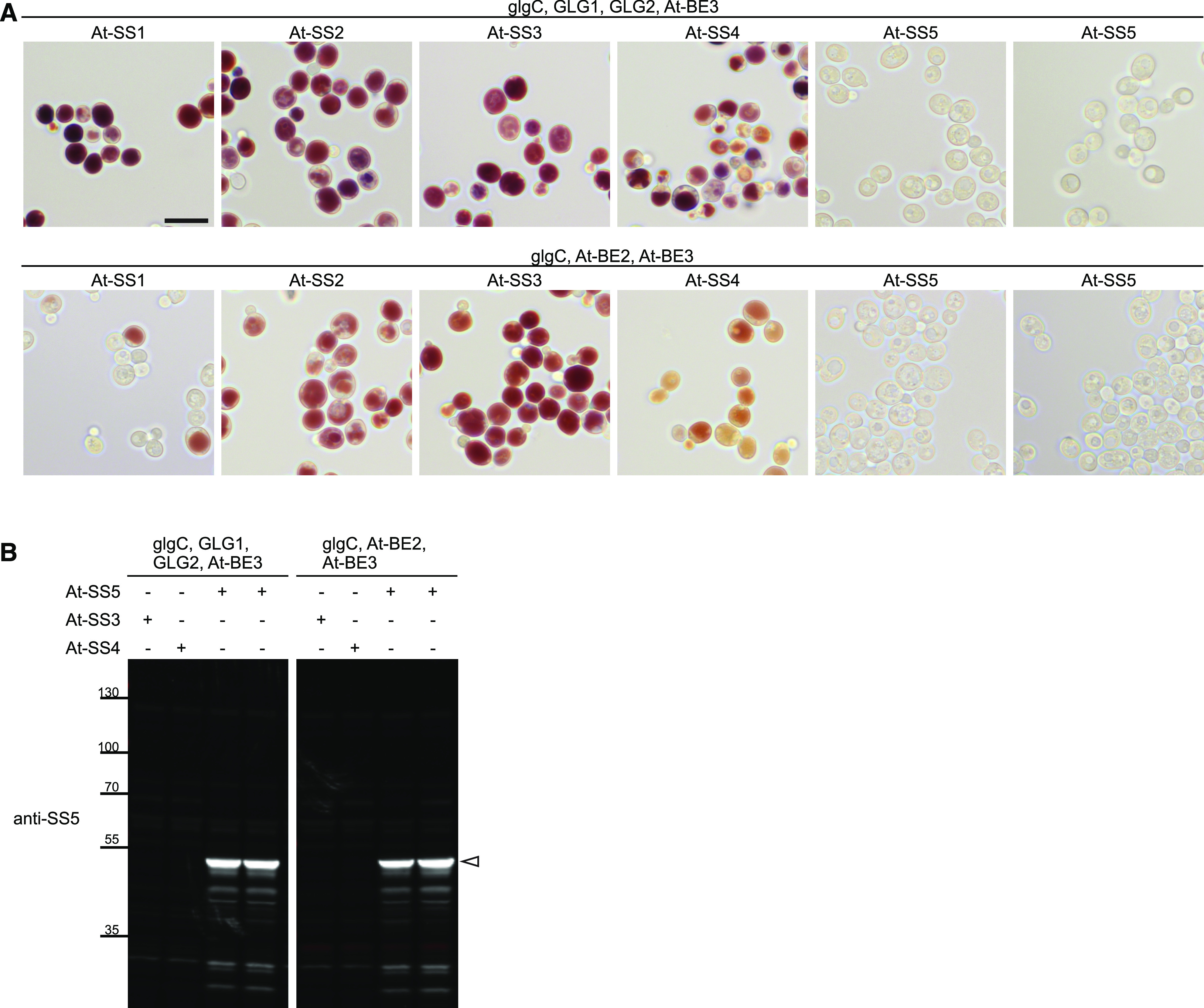

To validate experimentally that SS5 proteins are not functional GTs, recombinant At-SS5 and Os-SS5 proteins were expressed in and purified from E. coli (Supplemental Figure 3B). We then performed in vitro starch synthase assays, providing these purified proteins with 14C-labeled ADP-Glc and waxy maize (Zea mays) starch as donor and acceptor substrates, respectively. Neither SS5 protein was capable of incorporating any 14C into starch under these conditions, whereas recombinant At-GBSS did (Supplemental Figure 3C). The enzymatic inactivity of SS5 in this in vitro activity assay may be caused by a multitude of experimental details, such as the use of the wrong substrate. We thus expressed At-SS5 in our previously developed yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) system for the functional analysis of starch biosynthetic enzymes and the heterologous production of starch-like polymers (Pfister et al., 2016). In this system, all canonical Arabidopsis soluble SSs have been shown to produce glucans, presumably using the endogenous substrates in the yeast cells. When expressing At-SS5, we saw no glucan staining and thus no evidence of catalytic activity in two independent yeast strains, unlike strains expressing At-SS1, At-SS2, At-SS3, or At-SS4 (Figures 3A and 3B; Pfister et al., 2016). We also attempted to express the Os-SS5 protein in this yeast system but did not achieve reproducible expression. Nonetheless, the combination of bioinformatics and activity assays strongly suggests that SS5 proteins are not catalytically active as starch synthases.

Figure 3.

Arabidopsis SS5 Does Not Produce Glucans in Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

(A) At-SS1, At-SS2, At-SS3, At-SS4, and At-SS5 without their respective predicted chloroplast transit peptides were expressed in yeast cells purged of their endogenous glycogen-metabolic genes except for the glycogenin genes GLG1 and GLG2 as indicated by Pfister et al. (2016). Arabidopsis branching enzyme(s) and the bacterial ADP-Glc pyrophosphorylase (glgC; for the provision of ADP-Glc) were coexpressed as indicated. Six hours after the induction of heterologous protein expression, cells were stained with iodine to visualize glucan accumulation. Shown are representative light micrographs from two independent experiments that gave identical results. Bar = 10 μm.

(B) Representative immunoblot showing that At-SS5 was readily detected in soluble extracts of yeast at the expected size (white arrowhead) with the antibody raised against At-SS5.

The crystal structure of At-SS4 revealed a putative surface glucan binding site, characterized by an aliphatic patch on the surface of the GT5 subdomain (Nielsen et al., 2018). Interestingly, this site is strongly conserved not only in SS4 orthologs but also in SS5 homologs (Figure 2A, visible after a 90° turn; Supplemental Figure 3D). Potato SS5 has been found to be associated with potato starch granules in proteomic experiments (Helle et al., 2018), suggesting that the protein binds to starch. To test glucan binding for At-SS5, we incubated recombinant At-SS5 with waxy maize starch granules. This assay indicated that recombinant At-SS5 could indeed bind to starch, albeit weakly (Figure 2B). Residues suggested to interact with glucans at the active site (such as D678 in At-SS4; Sheng et al., 2009b; Nielsen et al., 2018) that are strongly conserved in canonical starch synthases are not consistently conserved in SS5 (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 3D). This suggests that glucan binding in At-SS5 may be mediated by the surface binding site. The At-SS5 GT5 subdomain is preceded by an N-terminal extension containing predicted (Lupas et al., 1991) coiled-coil motifs (Figure 1A). Regions with coiled-coil motifs are also present in the N termini of SS3 and SS4 (Pfister and Zeeman, 2016). The SS5 coiled-coil motif is conserved in orthologs (Supplemental Figure 4).

SS5 Is Weakly Expressed in Leaves

To study the role of SS5 in planta, we obtained three homozygous Arabidopsis lines with T-DNA insertions in different regions of the At-SS5 gene, AT5G65685 (Figure 4A). No phenotypic effects of the insertions were evident from an initial inspection of plant growth and morphology compared with the corresponding Col-0 wild type (Figure 4A). We confirmed disruption of the SS5 transcript by endpoint RT-PCR using primer pairs spanning the respective T-DNA insertion sites. As expected, no transcript fragments were detected in the insertional regions of the respective lines (Figure 4B). Because transcript fragments upstream and downstream of the respective insertions were readily amplified for all three lines, we further attempted to verify the absence of At-SS5 on the protein level. Proteome information from the publicly available database pep2pro (Baerenfaller et al., 2011) indicated low protein abundance for At-SS5. Furthermore, the predicted molecular mass (∼52 and ∼48 kD for full length and after chloroplast transit peptide cleavage, respectively) is similar to that of the large subunit of Rubisco (∼53 kD), rendering its detection by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting potentially problematic. Polyclonal antibodies recognizing the recombinant SS5 protein (Figure 2B) detected a faint band of the expected molecular mass on immunoblots of total protein extracts from wild-type but not ss5 leaves (Figure 4B). Its detection, however, was difficult due to nonspecific cross reactions with other, presumably more abundant, proteins and to the low SS5 protein levels. To determine the native SS5 expression pattern, we analyzed wild-type and ss5-1 plants transformed with the construct based on the genomic sequence of AT5G65685 that was used to confirm plastidial localization (Figure 1B). Expression of chimeric At-SS5-mCitrine, although low, was detectable when immunoblotting leaf protein extracts using anti-SS5 antibodies (Figure 5A). Again, endogenous SS5 could only be very faintly detected. Fluorescence microscopy of intact young rosettes expressing At-SS5-mCitrine confirmed very weak expression that was most visible in juvenile leaves (Figure 5B).

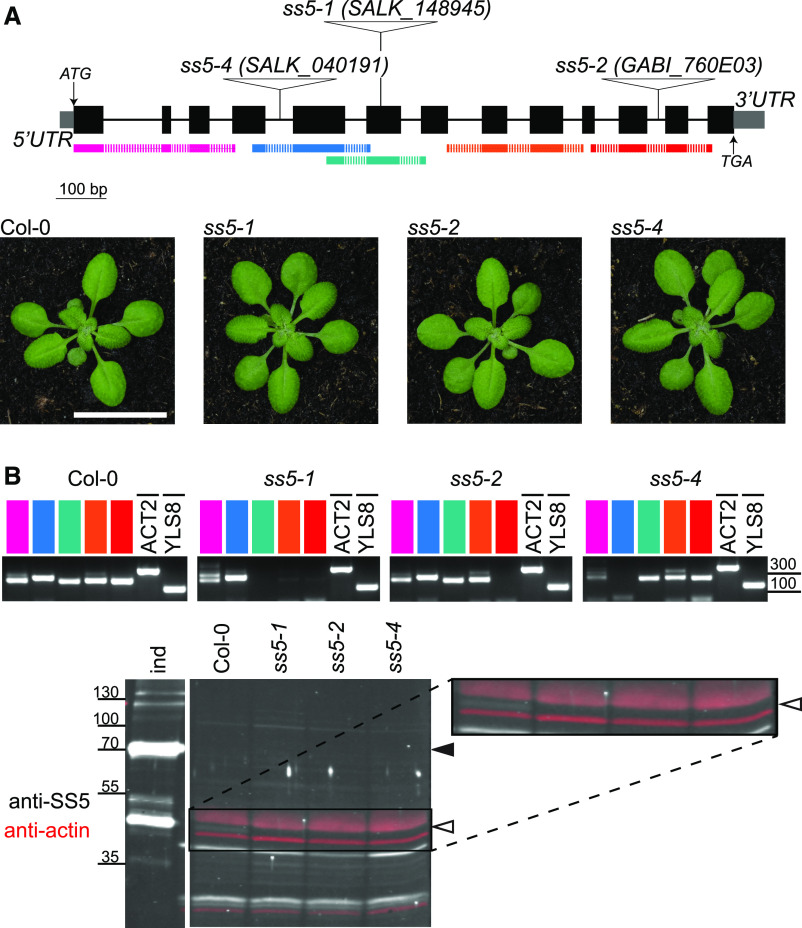

Figure 4.

Arabidopsis SS5 Insertional Mutants Lack SS5.

(A) Schematic representation of the At-SS5 genomic sequence (AT5G65685.1). Exons are represented as black boxes, introns as thin lines, and UTRs as gray boxes. Triangles show sites of T-DNA insertions of lines used in this study. Photographs of 25-d-old Arabidopsis rosettes of the respective lines are shown below the gene model. Bar = 2 cm.

(B) Confirmation of gene disruption in the T-DNA insertional mutants shown in (A). Upper panels, endpoint RT-PCR on cDNA preparations from wild-type (Col-0) plants and ss5 T-DNA lines. Colors correspond to the amplification products indicated below the gene model in (A). Note the absence of bands spanning the respective insertion sites. Primers used for RT-PCR are described in Supplemental Data Set 2. Lower panels, immunoblot of total leaf protein extracts probed with the antibody raised against At-SS5, showing a weak band corresponding to At-SS5 that is absent in the three T-DNA insertional mutant lines. An At-SS5-YFP anti-YFP immunoprecipitation sample (bait indicated by a black arrowhead) containing endogenous At-SS5 (indicated by a white arrowhead) as a prey was included as an indicator of native At-SS5 migration (ind); this lane was run on the same gel. Actin levels analyzed simultaneously on the blot (in red) served as a loading control.

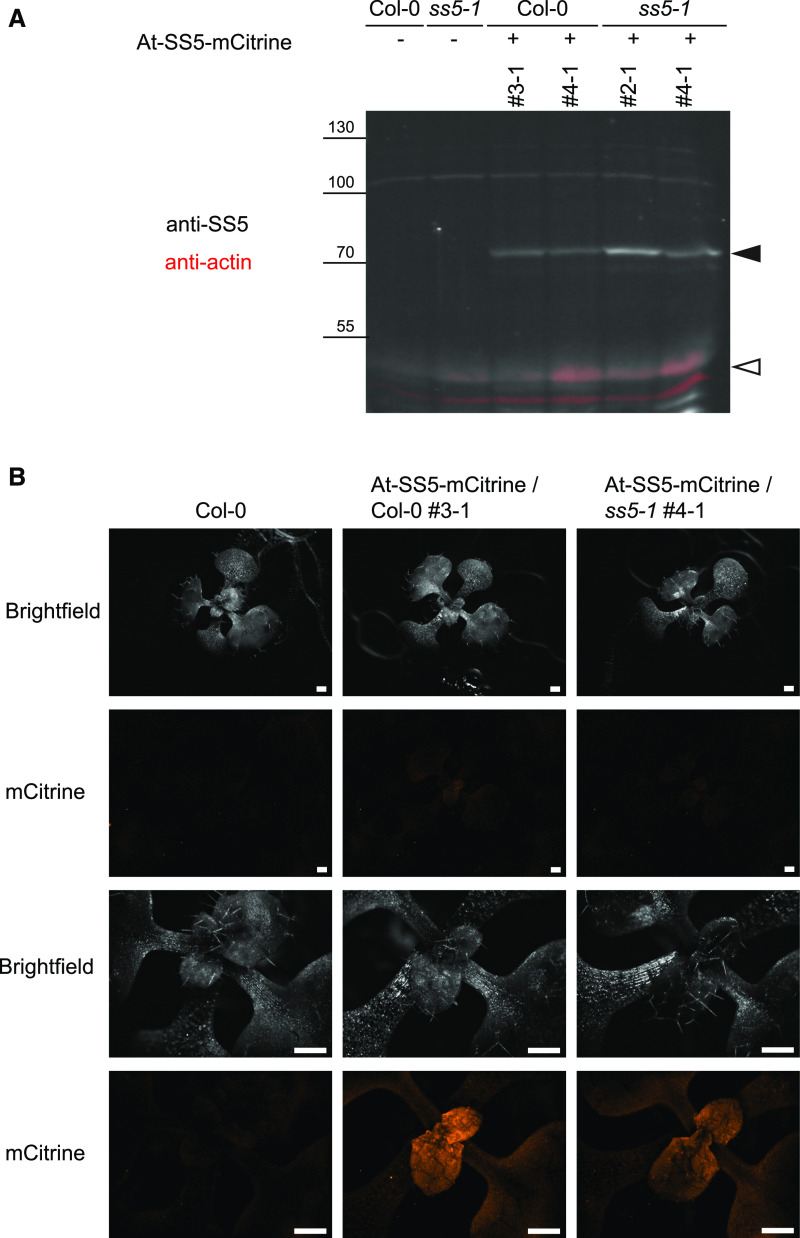

Figure 5.

Arabidopsis SS5 Is Expressed to Low Levels in Planta.

(A) Expression of At-SS5-mCitrine from a genomic fragment. An immunoblot of total leaf protein extracts is shown. Two independent transgenic lines are shown per background. mCitrine-tagged and endogenous At-SS5 are indicated by black and white arrowheads, respectively.

(B) Whole-rosette fluorescent imaging of 2-week-old transgenic plants expressing At-SS5-mCitrine driven by the At-SS5 promoter from a genomic fragment. The same rosette was imaged in both overview (upper two rows) and close-up magnifications (lower two rows). Bars = 500 μm.

SS5 Influences Both the Number and Size of Starch Granules in Chloroplasts

We investigated whether the loss of SS5 had any effect on amylopectin fine structure by analyzing the chain length distribution of ss5 starch. Consistent with the suspected catalytic inactivity of SS5, the chain length distribution of starch extracted from ss5 was indistinguishable from that of the wild type (Supplemental Figure 5). Measurements of the starch content in whole rosettes harvested at both the end of the day and the end of the night revealed a minor but statistically significant increase in starch content at the end of the night (Figure 6A). Similar trends were observed when starch content was monitored over a complete day-night (diel) cycle (Supplemental Figure 6A). We also tested whether the loss of SS5 affected the plant’s ability to regulate starch degradation by subjecting plants to unexpected changes in the length of the photoperiod. In wild-type plants, an unexpectedly long day elicits an increased rate of degradation during the subsequent short night, while an unexpectedly short day elicits a decreased rate during the subsequent long night (Scialdone et al., 2013). These patterns were also observed in ss5 mutants, although in each case there was a slight increase in starch throughout the measurements compared with the wild type (Supplemental Figure 6B).

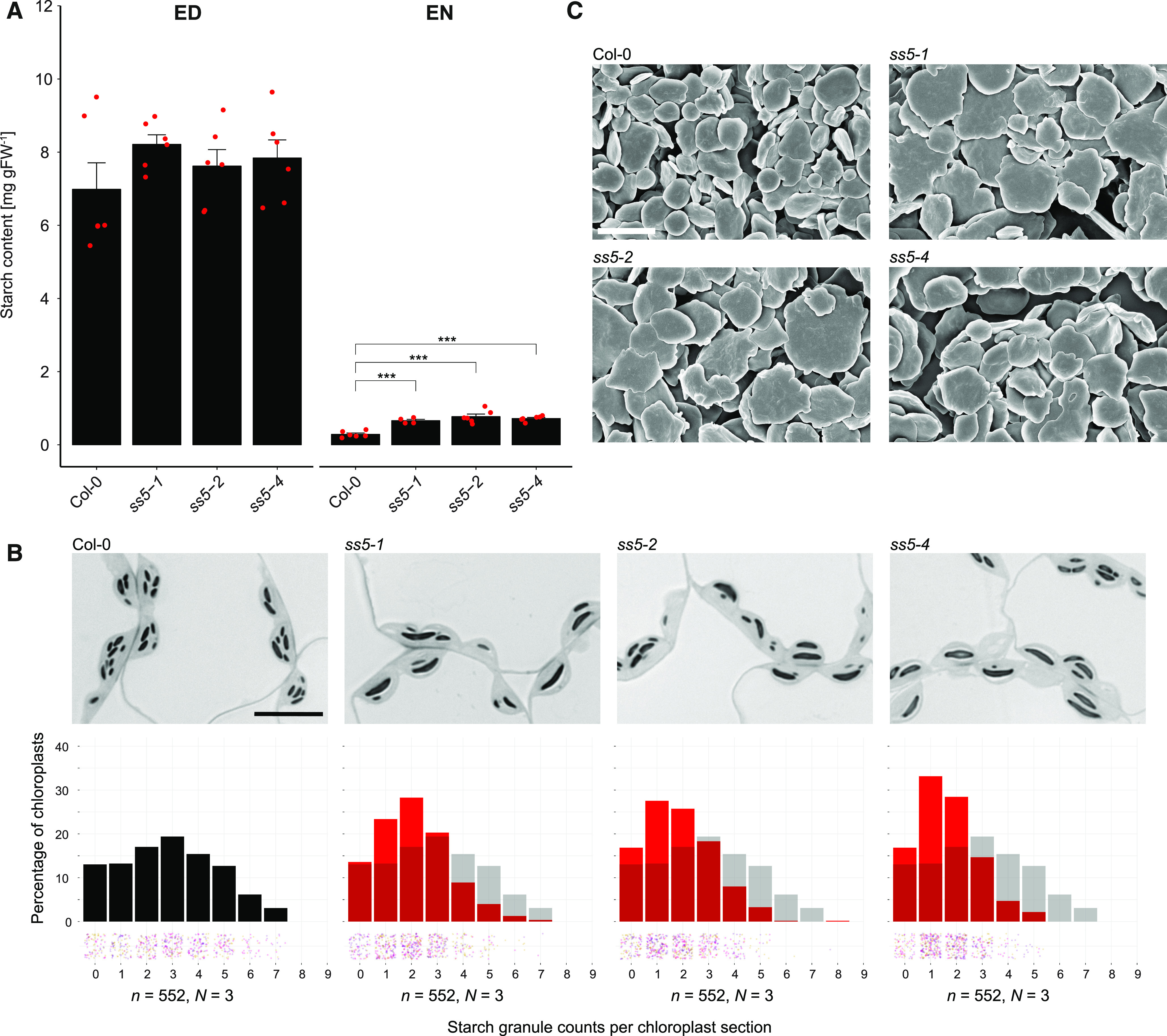

Figure 6.

Arabidopsis SS5 Insertional Mutants Produce Fewer but Larger Starch Granules Per Chloroplast.

(A) Starch content in whole Arabidopsis rosettes. Plants were harvested after 12 h of light (end of the day; ED) and after 12 h of dark (end of the night; EN). Error bars represent the se. ***, P < 0.001, based on t tests (n = 4 to 6 biological replicates [rosettes]; see also Supplemental Data Set 3). Individual measurements are shown by red points. FW, fresh weight.

(B) Starch granule quantifications in sections of embedded ss5 leaf tissue, represented as histograms of granules per chloroplast section in red with the wild-type (Col-0) distribution underlaid in transparent gray. Individual chloroplast counts (n) are scattered into bins below the histograms with hues differentiating the biological replicates (individually sampled rosettes; N). Representative light micrographs of the respective lines are shown above each histogram. Bar = 10 μm.

(C) Scanning electron micrographs of purified wild-type (Col-0) and ss5 starch granules at a magnification of 15,000×. Bar = 4 μm.

Next, we used light and electron microscopy to examine the chloroplasts and starch granules of ss5 mutants. Leaf samples were harvested at the end of the day, chemically fixed, and embedded in epoxy resin. Interestingly, quantitative analysis of the light micrographs revealed that the ss5 mutant lines produced significantly fewer starch granules per chloroplast than wild-type plants (Figure 6B). Sections from ss5 and the wild type had a grand mean ± composite se of 1.85 ± 0.03 and 2.89 ± 0.08 starch granules per chloroplast section, respectively. Note that these numbers are derived from 500-nm-thick sections only and that the actual number of granules in the entire chloroplast volume will be higher in both cases, as only a fraction of the chloroplast is being sectioned. The shift toward lower granule number per chloroplast in ss5 was comparable in all three T-DNA insertion lines (Figure 6B) and milder than in mutants recently identified and analyzed by our laboratory and others (e.g., ss4, ptst2, and mrc; Roldán et al., 2007; Seung et al., 2017, 2018; Vandromme et al., 2019). We purified and analyzed the starch granules of ss5 by scanning electron microscopy, and, consistent with the impression from light micrographs, purified ss5 starch granules appeared as flattened discoids but were much larger in diameter than wild-type granules (Figure 6C). Furthermore, they appeared irregular in shape, as has been observed for other abnormally large starch granules (Mahlow et al., 2014; Seung et al., 2017, 2018). These observations suggest that SS5, although probably not catalyzing a classic glucosyltransferase reaction, does have a role in the regulation of starch granule initiation.

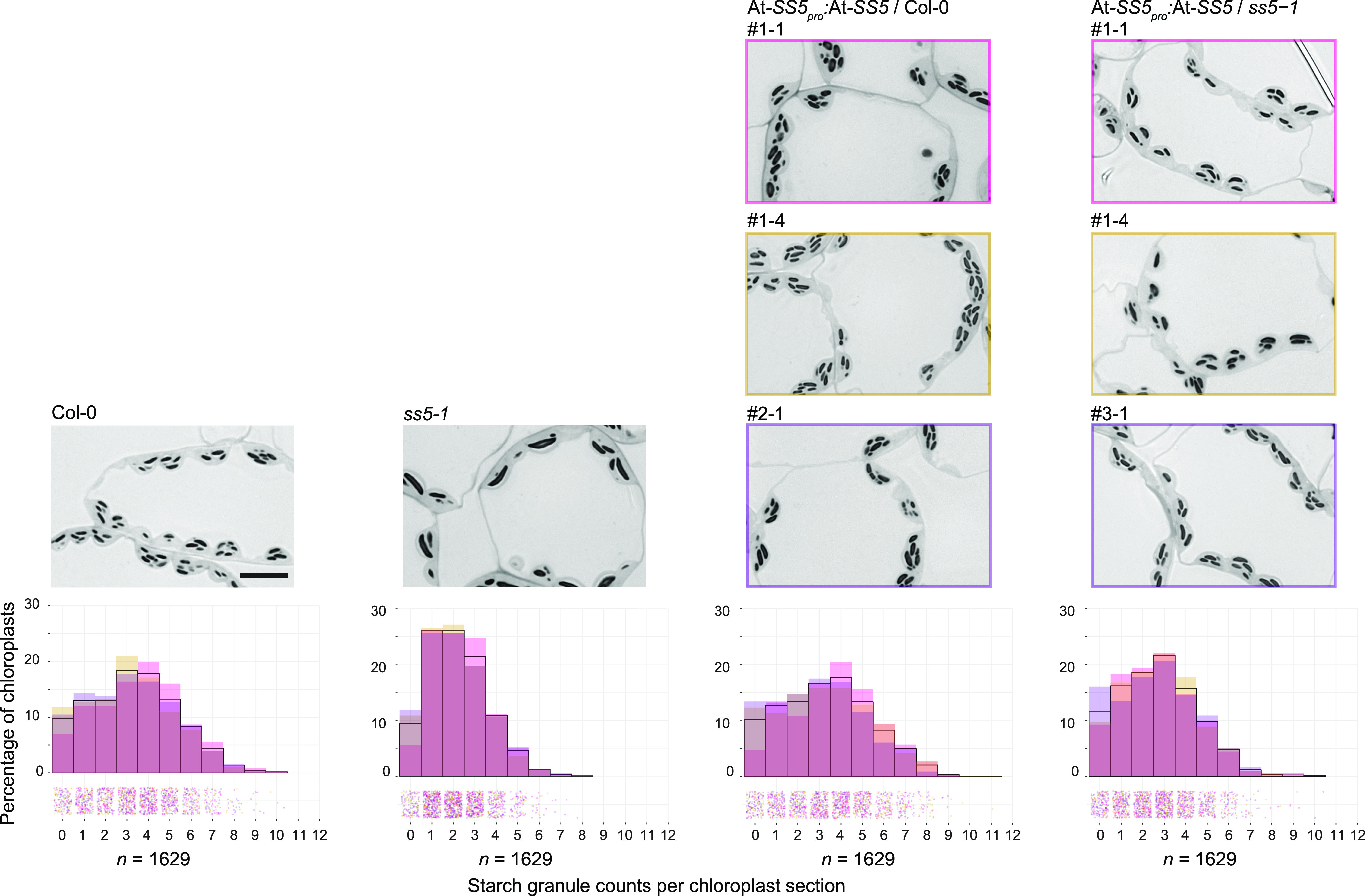

Surprisingly, the reduced granule number phenotype of ss5 was only partially complemented by the expression of At-SS5-mCitrine. Furthermore, we observed a slight dominant-negative effect when expressing this chimeric protein in the wild-type background (Supplemental Figure 7). This suggests that the mCitrine-tagged protein version is only partially functional and, when present, may interfere with the function of endogenous SS5. Given that the very C-terminal amino acids in SS5 proteins are conserved (Supplemental Figure 2A), we reasoned that the C-terminally placed tag may be the reason for dysfunction. Therefore, we modified our construct, introducing a stop codon before the tag. Indeed, At-SS5 expression from this construct fully complemented the starch granule number phenotype of ss5 mutants already in the T1 population (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Complementation of the ss5 Phenotype by SS5 Expression from a Genomic Fragment.

Overlay histograms represent the distribution of granule numbers per chloroplast section in each three replicate plants (Col-0 and ss5-1) or three independent T1 transformants per background. Different hues are shown to account for variations between different transgene insertions in this experiment; black outlines represent the mean across all lines or replicates. Individual counts (n) are scattered into bins below the histograms with hues corresponding to the respective transformant/replicate histogram. Representative micrographs of each transformant or control are shown above each histogram. Bar = 10 μm.

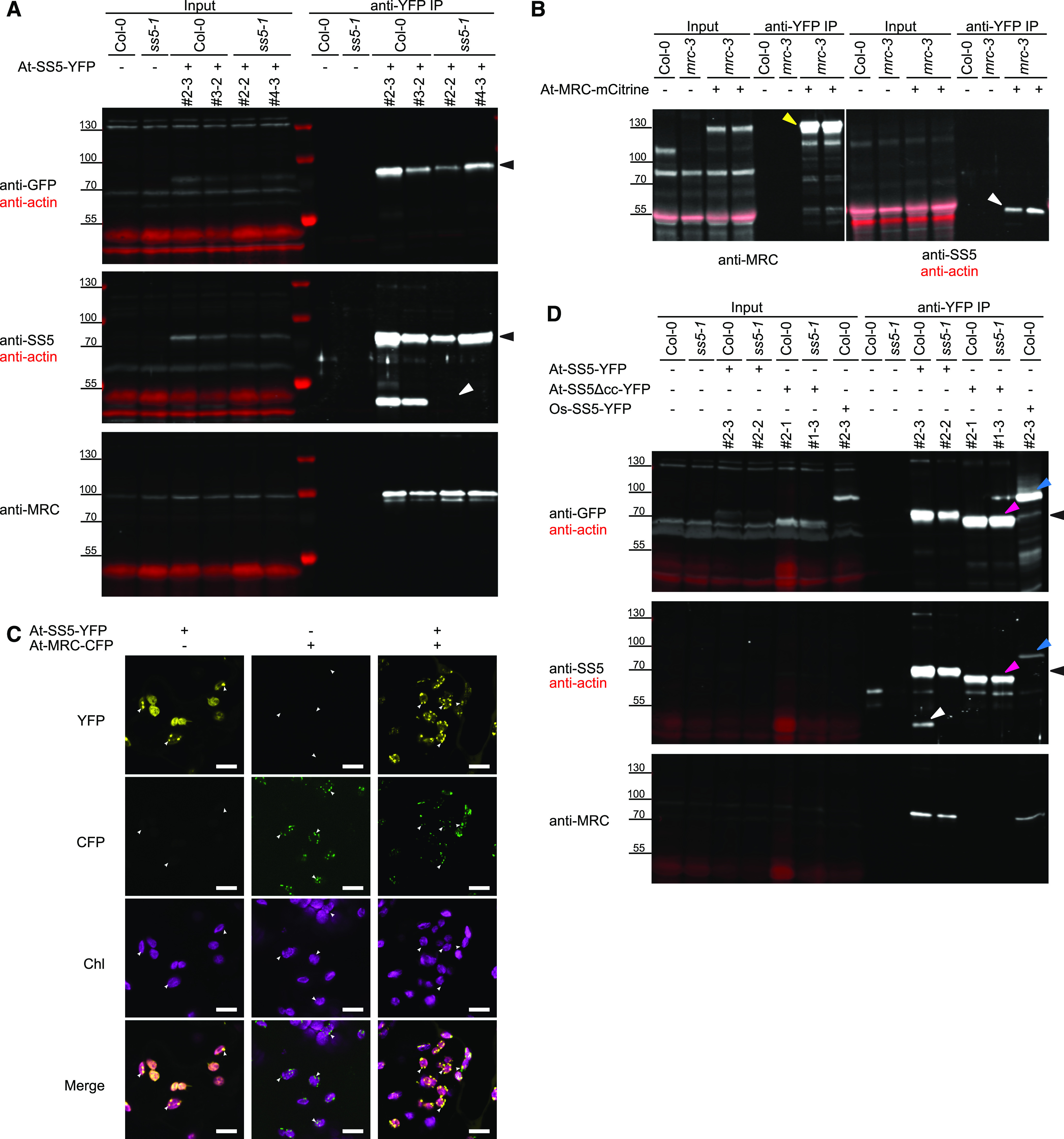

SS5 Interacts with Itself and MRC

Because SS5 has an N-terminal conserved coiled-coil region (Figure 1A; Supplemental Figure 4), we reasoned that it may exert its influence on granule initiation by interacting with other proteins. Therefore, we used both At-SS5-mCitrine expressed from the genomic construct as well as At-SS5-YFP expressed under the control of the UBIQUITIN10 promoter (UBQ10pro) as baits in immunoprecipitation experiments. Like At-SS5-mCitrine, At-SS5-YFP had a slight dominant-negative effect when expressed in the wild-type background and did not fully rescue the mutant ss5 phenotype (Supplemental Figure 8). We used magnetic beads to capture and enrich the baits via their mCitrine and YFP epitopes, respectively. When confirming bait enrichment using anti-At-SS5 antibodies, we noticed that the immunoprecipitate of plants expressing At-SS5-YFP in a wild-type background also contained a band corresponding to the endogenous SS5 protein. This band was absent when the At-SS5-YFP protein was immunoprecipitated from the ss5-1 background (Figure 8A, middle panel). This suggested that SS5 was able to multimerize in vivo. We made use of this feature as an indicator of endogenous At-SS5 migration in SDS-PAGE (Figure 4B). We also used it to test whether any of our ss5 mutant lines still expressed At-SS5 protein (e.g., a truncated form). As expected, this approach failed to retrieve the endogenous SS5 protein in different ss5 T-DNA insertion lines (Supplemental Figure 9).

Figure 8.

Arabidopsis SS5 and MRC Interact.

(A) At-SS5-YFP was expressed in different genetic backgrounds and immunoprecipitated via the YFP tag (black arrowheads). Shown are immunoblots using antibodies recognizing GFP/YFP, SS5, or MRC. Endogenous At-SS5 (white arrowhead) is enriched in the immunoprecipitate (IP) when the bait is expressed in a wild-type (Col-0) background, whereas At-MRC is enriched when it is expressed in either the wild-type or ss5 mutant background. Two independent transgenic lines are shown per genetic background. Actin, analyzed simultaneously (in red), served as a loading control on anti-GFP and anti-SS5 immunoblots.

(B) Immunoprecipitation using At-MRC-mCitrine (yellow arrowhead) as bait. Endogenous At-SS5 (white arrowhead) is enriched in the immunoprecipitate. Note that endogenous MRC runs slightly higher in this blot than in (A), likely due to the polyacrylamide gradient gel used for SDS-PAGE in this case.

(C) At-SS5-YFP and At-MRC-CFP were transiently expressed in tobacco leaves. When expressed together, the proteins colocalize to the same puncta (examples indicated by white arrowheads) in the chloroplast. Bars = 10 μm.

(D) Deletion of the At-SS5 coiled coil in the At-SS5Δcc-YFP bait abolishes both dimerization and interaction with At-MRC. The Os-SS5-YFP immunoprecipitate contains At-MRC but not endogenous At-SS5. Protein bands are indicated with arrowheads as follows: At-SS5-YFP, black; endogenous At-SS5, white; At-SS5Δcc-YFP, pink; Os-SS5-YFP, blue.

Next, we analyzed the At-SS5-mCitrine immunoprecipitate for other putative interaction partners using mass spectrometry. In addition to stably expressed At-SS5-mCitrine, we also used N-terminally polyhistidine-tagged At-SS5 recombinant protein purified from E. coli as a bait in crude extracts from wild-type plants. With both approaches, we consistently identified peptides of the MRC protein coprecipitating with At-SS5 baits, even when using very stringent exclusion criteria (Supplemental Table 1). Two other proteins (At-AMT1 and At-CHY4) were found in both immunoprecipitate types with our stringent exclusion criteria. However, both are likely false positives, as both proteins are not predicted to localize to the chloroplast (Loqué et al., 2006; Gipson et al., 2017).

We confirmed the presence of MRC in the At-SS5-YFP immunoprecipitate by immunoblotting with antibodies raised against MRC (Figure 8A, bottom). MRC was enriched by the SS5-YFP bait, regardless of whether it was expressed in wild-type or ss5 plants. Next, we used plants expressing At-MRC-mCitrine (Seung et al., 2018) for a reverse immunoprecipitation. Using this bait, we could detect coprecipitating endogenous At-SS5 in the immunoprecipitate (Figure 8B), confirming the interaction between the two proteins in vivo.

At-MRC was recently found to adopt a punctate subchloroplastic distribution (Seung et al., 2018), similar to what we observe for At-SS5-mCitrine (Figure 1B). To determine whether the two proteins localize to the same region in chloroplasts, we transiently expressed At-SS5-YFP and At-MRC-CFP in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaves under the control of the strong constitutive cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter (CaMV35Spro). Consistent with the results from stable Arabidopsis transformants, both At-MRC-CFP and At-SS5-YFP localized to discrete puncta when expressed individually (Figure 8C). A significant fraction of At-SS5-YFP additionally displayed a diffuse, likely stromal, localization. Interestingly, when coexpressing both proteins, At-SS5-YFP and At-MRC-CFP colocalized to the same puncta, consistent with their physical interaction.

To test our initial hypothesis that the N-terminal coiled-coil motif of At-SS5 mediates the observed protein-protein interactions, we expressed an At-SS5 protein version lacking this region (At-SS5Δcc-YFP) in Arabidopsis. Expression of the At-SS5Δcc-YFP protein version did not elicit the dominant-negative phenotypic effects seen for the expression of At-SS5-YFP in the wild-type background, indicating that this deletion protein is not functional. Consistently, expression of At-SS5Δcc-YFP in the ss5 mutant background did not strongly affect the starch granule phenotype (Supplemental Figure 10). To test whether this may be related to protein-protein interactions, we used protein extracts of plants expressing At-SS5Δcc-YFP for immunoprecipitations. We detected neither the endogenous At-SS5 nor At-MRC in the immunoprecipitate when using this truncated protein as a bait (Figure 8D), suggesting both that the conserved coiled coil is directly or indirectly mediating homomeric and heteromeric interactions and that these interactions are crucial to the protein’s function.

We further investigated if the homomeric and heteromeric interactions that we observed for At-SS5 are evolutionarily conserved by cloning and expressing the rice Os-SS5-YFP protein in wild-type Arabidopsis under the control of CaMV35Spro. As with fluorescently tagged At-SS5, we observed a dominant-negative effect on starch granule numbers when expressing this protein in the wild-type background (Supplemental Figure 10). When subjecting these plants to an anti-YFP immunoprecipitation, we detected the Arabidopsis MRC protein both by immunoblotting (Figure 8D, bottom panel) and by mass spectrometry (Supplemental Table 1), indicating that the rice SS5 ortholog can also interact with At-MRC. However, we could not detect the endogenous At-SS5 in the immunoprecipitate by immunoblotting (Figure 8D, middle panel). Using mass spectrometry, two peptides matching At-SS5 were detected in one of the replicates only (Supplemental Table 1). This experiment could not determine whether or not Os-SS5 undergoes homomultimerization as does At-SS5.

SS5 Modifies Several Starch Granule Initiation Phenotypes

Our observations strongly suggest a physical interaction between MRC and SS5. This is interesting since their mutant phenotypes are similar despite that of mrc being more severe; the vast majority of chloroplast sections in mrc mutant plants contain a single, large starch granule (Seung et al., 2018). We thus crossed the ss5-1 line with mrc and selected a homozygous double mutant line to determine whether the additional loss of SS5 in the mrc background would enhance the mrc phenotype. However, we could not discriminate between the phenotypes of mrc and the mrc ss5 double mutant (Figure 9A). This suggests that SS5 influences starch granule numbers via the MRC protein.

Figure 9.

SS5 Exerts Its Function through MRC and Acts in the Absence of SS4.

(A) Quantification of starch granule content, represented as histograms of counts per chloroplast section, in crosses of ss5-1 and mutants of other proteins involved in starch granule initiation. Shown is the distribution upon loss of SS5 (red) in the wild-type (Col-0) or mutant background (transparent blue). Individual chloroplast counts (n) upon loss of SS5 are scattered into bins below the histogram with different hues representing biological replicates (N). Representative micrographs of the genetic background as well as the respective double mutants are shown above each histogram. Note that plants used for this quantification come from the same experimental batch (and therefore share the same Col-0 and ss5-1 quantifications) as the ones used for Figure 6B. Bar = 10 μm.

(B) Whole-rosette measurements of starch content in the ss4 ss5 double mutant (n = 4 to 6 rosettes). Plants were harvested after 12 h of light (end of the day; ED) and after 12 h of dark (end of the night; EN). Individual data points are shown in red. FW, fresh weight.

(C) Iodine-stained rosettes harvested at end of the day. Wild types and ss5-1 stain similarly. As in ss4, immature leaves of ss4 ss5 double mutants show very weak staining. Shown are two biological replicates for each genotype.

(D) ADP-Glc content measurements of the ss4 ss5 double mutant (n = 3 to 4 rosettes). Entire rosettes were harvested at end of the day, and metabolites were extracted and quantified as described previously by Seung et al. (2016). Individual data points are shown in red.

Error bars in (B) and (D) represent the se. Asterisks show statistical significance: *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; and ***, P < 0.001, based on t tests.

Given that SS5 is most closely related to SS4 and that SS4 has a pivotal role in starch granule initiation, we also created an ss4 ss5 double mutant. We found no significant difference in starch contents of ss4 ss5 compared with the ss4 single mutant parent (Figure 9B). Iodine-stained rosettes harvested at the end of the light phase showed a characteristic ss4-like heterogenous starch accumulation in leaves of different ages in the ss4 ss5 double mutant (Figure 9C), whereas starch was homogenously distributed in ss5-1 rosettes, as in the wild type. Quantification of starch granules in sections of ss4 ss5, however, revealed an even higher fraction of chloroplasts failing to initiate any granules than in ss4 (Figure 9A). Consistent with this, we measured a significant increase in ADP-Glc in ss4 ss5 compared with ss4 (Figure 9D). Because the ss4 and ss5 phenotypes are additive rather than epistatic, we conclude that SS5 does not exert its function through SS4.

We also crossed ss5-1 to the mutants lacking PTST2 or PTST3, two homologous proteins proposed to provide SS4 with malto-oligosaccharide substrates for granule initiation (Seung et al., 2017). In both cases, we observed a shift toward lower starch granule numbers (Figure 9A). This effect was relatively mild in the ptst2 ss5 double mutant compared with ptst2 but particularly strong in the ptst3 ss5 double mutant compared with ptst3. Both ss5 and ptst3 single mutant phenotypes are mild (Seung et al., 2017), but the combination of both mutations resulted in a strong phenotype that was similar to that of mrc. Last, we crossed ss5 to a mutant of MFP1, a plastidial coiled-coil protein that was suggested to influence the subchloroplastic localization of PTST2 (Seung et al., 2018). Here, we observed a granule number distribution that was, surprisingly, shifted slightly toward more granules compared with the mfp1 parent (Figure 9A). Because the difference was small, further investigation will be helpful to support this observation. Together, these data suggest that SS5, acting via MRC, operates in a previously unrecognized dimension of the starch granule initiation process.

DISCUSSION

Arabidopsis SS5 Is a Noncanonical Starch Synthase That Influences Starch Granule Abundance and Morphology

We have shown that Arabidopsis SS5 is a noncanonical member of the plastidial starch synthase family that, although lacking the glucosyltransferase activity associated with the canonical members (Figure 3; Supplemental Figure 3C), influences the number and morphology of starch granules that form in chloroplasts. The number of starch granules is significantly reduced in three independent ss5 mutant lines compared with the wild type, and the ss5 granules, although typically discoid, are abnormally large, with irregular margins (Figures 6B and 6C). Total starch content in ss5 is largely comparable to wild-type levels, except for slightly increased levels at the end of the dark phases, and this may be attributable to the alterations in the granule numbers and sizes having a direct effect on the rate of degradation, as previously suggested for SS4 (Roldán et al., 2007). However, amylopectin structure in the ss5 mutant lines is unaffected (Supplemental Figure 5), suggesting that SS5 plays a role in processes that directly initiate or otherwise control the number of starch granules in chloroplasts rather than in amylopectin biosynthesis.

Starch granule initiation in Arabidopsis has received much attention recently, with a multitude of novel proteins being discovered. SS4, the closest homolog of SS5, was the first protein to be identified as both a mediator of starch granule initiation (Roldán et al., 2007) and a determinant of starch granule morphology. The ss4 mutant phenotype is severe, with many chloroplasts failing to produce any granules and with those that are produced displaying morphological anomalies (i.e., they are more spherical than the normal discoid form; Roldán et al., 2007). The subsequent discovery of PTST2 and PTST3 (Seung et al., 2017) and MFP1 and MRC (Seung et al., 2018; Vandromme et al., 2019), all of which exert varying levels of influence on granule numbers, suggests that granule initiation is a far from simple process. Interactions among these proteins and with glucan substrates has fueled speculation about the molecular mechanisms underpinning granule initiation. Present models place PTST2 and SS4 at the heart of the process, with PTST2 binding long malto-oligosaccharides (degree of polymerization > 10) and presenting them as substrates to SS4 for elongation into granule initials (Seung et al., 2017). The association of PTST2 with thylakoid-associated MFP1 is suggested to determine where within the chloroplast these initiation events take place. The importance attributed to SS4 and PTST2 in the model is partly due to the strong phenotypic consequences of the loss of these proteins (Roldán et al., 2007; Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2013; Ragel et al., 2013; Seung et al., 2017). In comparison, the phenotypes of mfp1 and mrc are less severe (Seung et al., 2018) and that of ptst3 is even milder (Seung et al., 2017) under standard experimental conditions.

We showed that ss5 plants produce lower numbers of starch granules. The ss5 mutant phenotype is comparable to that of ptst3 (Figures 6B and 9A). Together with the protein’s relationship to SS4 (Figure 2A; Supplemental Figure 1), its capacity for carbohydrate binding (Figure 2B), and its interaction with MRC (Figures 8A and 8B; Supplemental Table 1), this strongly implicates SS5 as part of the protein network that establishes the correct number of starch granules per chloroplast. The phylogenetically broad representation of SS5 proteins (Supplemental Figure 1) indicates that this function may be well conserved.

SS5 Is Part of the Starch Granule Initiation Protein Network

Although our data show that SS5 is almost certainly not an active glucosyltransferase, there are conspicuous similarities with SS4. We have shown in vitro that At-SS5 is capable of binding glucans (Figure 2B) and that a putative surface carbohydrate binding site recently identified in At-SS4 (Nielsen et al., 2018) is strongly conserved in SS5 proteins. Although the significance of this site for SS4 function is not yet known, it is plausible that it plays a role in substrate coordination or the association of the protein with the starch granule surface. Because the glucosyltransferase active site is not conserved in SS5 (Figure 2A), we propose that the observed binding to glucans is mediated by this site.

We also observed that SS5 interacts with itself and with MRC (Figures 8A and 8B), and these are properties also reported for SS4 (Raynaud et al., 2016; Vandromme et al., 2019). Interestingly, the ability to interact with At-MRC was conserved in the full-length SS5 from rice (Figure 8D). It is uncertain whether the sites of interaction are common to SS4 and SS5 proteins. The N-terminal parts of both proteins feature predicted coiled-coil motifs, parts of which show amino acid sequence similarity. Deletion of the coiled coil from At-SS5 prevented both multimerization and interaction with MRC (Figure 8D). However, the part of the SS4 protein implicated in dimerization by Raynaud et al. (2016) is not conserved in SS5, and the part(s) mediating its interaction with MRC are unknown. Nevertheless, the N-terminal part of SS4 was shown to be critical both for its function in terms of localizing the protein within the chloroplast (Raynaud et al., 2016) and for controlling the morphology of the developing starch granules (Lu et al., 2018). In contrast to ss4, granules from ss5 display an overall discoid morphology. The same is true for mrc granules, suggesting that neither the interaction of SS4 or SS5 with MRC is involved in the regulation of granule morphology.

Our data suggest that SS5 may exert its function through its interaction with MRC, as the MRC mutation was epistatic over that of SS5 (Figure 9A). The MRC protein is rich in predicted coiled-coil motifs and likely serves some sort of scaffolding function, potentially bringing SS4 and/or SS5 into contact with other protein factors. Unfortunately, besides SS4 and SS5 binding, the precise role of MRC itself in granule initiation is unclear. Based on the analysis of fluorescent fusion proteins, its subchloroplastic localization appears to be concentrated in discrete puncta (Seung et al., 2018; Vandromme et al., 2019). Interestingly, we saw that SS5 localized to similar puncta when expressed as a fluorescent fusion protein in Arabidopsis (Figure 1B) and that the localization pattern of MRC and SS5 overlapped when the two proteins were coexpressed in tobacco (Figure 8C). Unlike MFP1, MRC behaves as a soluble stromal protein in extracts, and the nature of the puncta formed by fluorescently tagged MRC and SS5 thus remains unclear at this point. Furthermore, we again note that the SS5 fusion proteins used in this study were only partially functional. Even though they enabled us to detect the interaction with MRC, which could be validated by reciprocal immunoprecipitation experiments, the in vivo localization studies should be treated as preliminary. The use of new lines and advanced microscopy techniques capable of correlating fluorescent signals with the chloroplast ultrastructure will provide the necessary plastid context to fully evaluate such localizations in the future.

The analysis of double mutants between ss5 and lines lacking other granule initiation factors revealed intriguing genetic interactions. Whereas the observed epistasis of mrc over ss5 (Figure 9A) was clear and consistent with the observation of the two proteins interacting, observations made for other double mutants were more difficult to interpret. In the absence of SS4, SS5 still appeared to promote granule formation because the phenotype of the ss4 ss5 double mutant was more severe than that of the ss4 single mutant. Similarly, ptst2 ss5 had a stronger phenotype than ptst2, which is consistent with the current hypothesis of PTST2 and SS4 acting together (Seung et al., 2017). However, the phenotype of the ss5 mfp1 double mutant was no more severe than that of mfp1; if anything, a slight alleviation of the phenotype was observed. Strikingly, the ss5 ptst3 double mutant had a strongly enhanced, mrc-like phenotype compared with its parental mutant lines (Figure 9A). Importantly, these data illustrate that granule initiation can be greatly perturbed by the loss of factors that individually have small influences, emphasizing that the roles of such factors should not be underestimated based on their single mutant phenotypes. However, they also illustrate that proteins acting in the process of starch granule initiation may not act in linear pathways and that the analysis of mutant phenotypes consequently may not follow strict epistatic principles.

Future studies are needed to address potential confounding factors—including the high multiplicity and redundancy of the involved proteins—that may effectively mask aspects of how starch granules are being formed. These future studies may include a detailed analysis of higher order mutants and the thorough exploration of the extent to which the involved proteins colocalize and functionally interact in vivo. Such data will help us to understand how the numbers of initiated starch granules are determined, the way they develop, and where within the chloroplast this is most likely to happen. They will also help us to establish whether granules can be initiated via different mechanisms and which protein complex configurations can successfully do so, as discussed below. Parallel analyses will be required to clarify to which extent the roles and interactions of proteins are conserved in species other than Arabidopsis and in storage tissues. This is especially important since recent research has indicated significant species- and tissue-specific consequences of the loss of individual proteins involved in this aspect of starch metabolism (Peng et al., 2014; Saito et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2019; Zhong et al., 2019; Chia et al., 2020).

SS5 Is Relevant in Starch Granule Initiation: How and Why?

The similarities between SS4 and SS5 indicate that their functions likely have common mechanistic origins, yet functional divergence has occurred with the degeneration of catalytic GT abilities in SS5. The mild phenotype of ss5 mutants and the observation that SS5 acts in the absence of SS4 indicate that its role is related to aspects of granule initiation that do not directly or exclusively require SS4. Yet, both SS4 and SS5 interact with MRC. These findings may be interpreted in several ways. On the one hand, SS4, SS5, and MRC (and possibly other factors) may constitute one large protein complex that is compromised to a certain extent upon the absence of either constituent subunit. However, we did not detect SS4 among the potential interaction partners of SS5 in our immunoprecipitation experiments (Supplemental Table 1). This could be due to difficulties in detecting weak or indirect interactions. However, it is also possible that MRC may interact with either SS4 or SS5 but not with both at the same time.

Thus, an alternative explanation is that SS4 and SS5 act in separate protein complexes that both—via similar or different mechanisms—promote the initiation of starch granules. Given the enzymatic inactivity of SS5, a granule-initiating complex containing SS5 may require the incorporation of another canonical starch synthase. In the absence of SS4, SS3 can initiate some granules (Szydlowski et al., 2009; Seung et al., 2016), so SS3 may be a good candidate for this role. In this context, the fact that ss4 ss5 plants still produce some starch would suggest that SS5 assists, but is not essential for, SS3 to initiate granules. However, we also did not detect a physical interaction between SS5 and SS3. As for SS4, it is difficult to rule out the possibility of a weak, transient, or indirect interaction. Again, we note that the fluorescent tag, which influenced the function of SS5 somewhat, may have reduced or prevented some functionally important interactions. The overall question remains as to why a noncatalytic starch synthase would promote starch granule initiation by any of the canonical starch synthases.

An intrinsic aspect of transitory starch metabolism is the recurrent alternation between biosynthesis and degradation over the diel cycle, which intuitively implies the need for reinitiation. However, the need for starch granule initiation may differ greatly depending on the developmental stage of the leaf and on varying environmental conditions that may occur over multiple diel cycles. For instance, it has been suggested that starch granule initiation is closely coordinated with chloroplast division and maturation, which happens mostly as leaves develop and expand (Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2012, 2013). Because chloroplasts divide by fission, it would presumably be advantageous for each daughter chloroplast to be equally endowed with starch and the biosynthetic apparatus for producing it—something that is easiest to achieve by having multiple discrete granules. It is also possible that the presence of just a few, or only one, large starch granule may impede the chloroplast division process. These ideas are consistent with the observation that starch granule numbers per chloroplast are highest in immature leaves and lower in mature leaves (Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2012), even though the overall starch content is similar (Zeeman and Rees, 1999).

Furthermore, young, actively growing leaves have high metabolic demands and might fully deplete their starch reserves at night to fuel growth, and this could necessitate de novo initiations each dawn. In this context, SS4 appears to be especially important, as young ss4 mutant leaves are essentially starchless (Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2013). In contrast, cycles of granule growth and shrinkage may predominate in mature source leaves (Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2012), with remnant granules from the previous diurnal cycle serving as substrates for the starch biosynthetic machinery at dawn. In such a case, de novo initiations will be required less frequently or may even be suppressed. Consistent with this, inducible knockdown of SS4 expression only seemed to impact upon starch granule numbers in newly emerging tissue but not in mature leaves (Crumpton-Taylor et al., 2013).

Even if the need for granule initiation is high in young tissues, this does not mean that they are unnecessary in mature tissue; it is likely that individual chloroplasts undergo stochastic fluctuations in granule numbers and that low frequencies of new initiations may still be necessary to adjust those fluctuating numbers. Compared with the initiations presumably mediated by SS4 in developing/dividing chloroplasts, initiations in mature leaves would take place under quite different conditions and alongside existing starch granules, the growth of which may sequester active components of the biosynthetic machinery. In such a scenario, the unique features of SS5 may promote the initiation of new starch granules by binding glucan substrates and localizing them via interaction with MRC. Alternatively, SS5 may shield nascent granule initials from amylolytic degradation (Seung et al., 2016), thereby increasing their lifetime and availability to the biosynthetic machinery. Further biochemical and molecular genetic analyses, such as the characterization of the putative oligosaccharide surface binding site and the expression of altered protein versions, will help to resolve the precise function of SS5 in the network of proteins enabling starch granule initiation.

METHODS

Phylogenetic and Sequence Analyses

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) SS1, SS2, SS3, SS4, and SS5 sequences were retrieved from Phytozome and orthologs from the National Center for Biotechnology Information via BLASTp, searching the refseq_protein database. The three closest prokaryotic GS sequences of At-SS3, At-SS4, and At-SS5 (WP 048672006.1, WP 059061331.1, and WP 026046064.1, respectively), as determined by searching the Procaryotae, were included as an outgroup. A multiple sequence alignment was created using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004), and a phylogenetic tree was constructed in MEGA (Tamura et al., 2013), using a maximum likelihood method based on the Jones-Taylor-Thornton matrix-based model (Jones et al., 1992) and 1000 bootstrap replications. Positions with less than 95% site coverage were eliminated. The alignment used for tree construction in MEGA format is provided in Supplemental Data Set 4A, and the corresponding tree file is provided in Supplemental Data Set 4B.

For analyses of specific motifs and residues mentioned in this article and shown in Supplemental Figures 3A and 3D, regions of interest were located in the multiple sequence alignment created above based on previously published sequence information (Sheng et al., 2009b; Nielsen et al., 2018) and analyzed with respect to SS isoforms. WebLogos were constructed using WebLogo3 (Crooks et al., 2004).

For analysis of the C-terminal deletion in SS5 isoforms, sequences belonging to the SS5 family were complemented by the orthologous sequences of the close Arabidopsis relatives Arabidopsis lyrata, Camelina sativa, and Capsella rubella. An alignment was generated using MUSCLE (Edgar, 2004) in MEGA (Tamura et al,. 2013).

Batch GT5 and GT1 predictions for starch synthase sequences were performed using the HMMER web server (hmmer.org). Corresponding data can be found in Supplemental Data Set 1. Domain predictions for the Arabidopsis starch synthase isoforms and Os-SS5 depicted in Figure 1A were predicted using TargetP (Emanuelsson et al. 2000), ChloroP (Emanuelsson et al., 1999), SMART (Schultz et al., 1998), Coils (Lupas et al., 1991), and Pfam (Sonnhammer et al., 1997). Shown in Figure 1A are AED93283.1 (At-SS1), AEE73621.1 (At-SS2), AEE28775.1 (At-SS3), AEE84015.1 (At-SS4), ABJ17089.1 (At-SS5), and XP_015626202.1 (Os-SS5).

Protein Structure Prediction and Surface Conservation

For prediction of the three-dimensional structure of At-SS5 and Os-SS5, the respective primary sequences were used for homology modeling using SWISS-MODEL (Waterhouse et al., 2018) and the previously published structure of the At-SS4 catalytic domain (amino acids 533 to 1040 of the product of AT4G18240.1; SWISS-MODEL Template Library ID 6gne.1) as template (Nielsen et al., 2018). The resulting models were visualized in PyMOL (http://pymol.org). For surface residue conservation of SS4, amino acid sequences belonging to the SS4 family were aligned using Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011). From this alignment, conserved and conservatively substituted residues were identified and mapped to the PyMOL coordinates. This was similarly done for surface residue conservation of At-SS5 and Os-SS5, while for the latter, C-terminally truncated SS5 sequences (from Arabidopsis, Glycine max, and Amborella trichopoda) were excluded prior to alignment. The pdb models for At-SS5 and Os-SS5 can be found in Supplemental Data Sets 5 and 6.

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Arabidopsis plants were grown under controlled conditions in CLF Plant Climatics, Percival AR-95L fitted with fluorescent tubes (Philips 368290 F25T8/TL841 ALTO) and supplemented with red LED panels or Kälte 3000 climate chambers fitted with fluorescent tubes under a 12-h-light and 12-h-dark cycle, unless otherwise specified. Light intensity was fixed at 150 μmol photons m−2 s−1, the temperature was 20°C, and the relative humidity was 65%. Seeds were sown on soil (Klasmann TKS 2) or on 0.8% (w/v) agar plates containing one-half-strength Murashige and Skoog (MS) medium including vitamins (Duchefa Biochemie) at pH 5.7 and stratified at 4°C before germination.

T-DNA insertion lines for AT5G65685 were obtained from the Salk Institute Genomic Analysis Laboratory (Alonso et al., 2003) and from GABI-Kat (Kleinboelting et al., 2012). All mutants used are in the Col-0 ecotype background: ss5-1 (SALK_148945), ss5-2 (GABI_760E03), and ss5-4 (SALK_040191). Homozygous lines were isolated by PCR-based genotyping. Primers matching the corresponding transformation vector were used to amplify the region containing the border between T-DNA and genomic sequence, and the insertion sites were confirmed by Sanger sequencing. All crosses with ss5 in this study were done using the ss5-1 line, to the previously described ss4-1 (Roldán et al., 2007), ptst3-5 (Seung et al., 2017), mfp1-1, mrc-3, and ptst2-7 (Seung et al., 2018) lines. Homozygous double insertional mutants were selected as described above.

Cloning for Expression of Recombinant Protein, Purification of Polyhistidine-Tagged Protein, and Production of Anti-SS5 Antibody

Primers used for genotyping (unless described elsewhere) and molecular cloning are listed in Supplemental Data Set 2. For the expression of polyhistidine-tagged At-SS5 in Escherichia coli, the At-SS5 coding sequence was amplified excluding the first 117 bp encoding the putative chloroplast transit peptide. For the expression of polyhistidine-tagged Os-SS5, an E. coli codon-optimized version of starch synthase V precursor (ACC78131.1) was synthesized (Invitrogen) and amplified excluding the first 156 bp encoding the putative chloroplast transit peptide. At-SS5 and Os-SS5 fragments were then cloned into the E. coli expression vector pProEX HTb (Invitrogen) using BamHI/XhoI and NotI/XhoI, respectively, in frame with an N-terminal poly(6×)histidine tag and transformed into BL21 CodonPlus ΔglgAP cells (Morán-Zorzano et al., 2007; Szydlowski et al., 2009). Note that ACC78131.1 differs from XP_015626202.1 (used for phylogeny and modeling) by one nonconserved amino acid C terminal to the predicted GT5 subdomain.

For recombinant protein purification, cells were grown in Luria-Bertani medium to an OD of 0.6. Recombinant protein expression was induced by the addition of 1 mM isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside, followed by a 16-h incubation at 18.5°C. Cells were lysed, and polyhistidine-tagged proteins were purified using Ni2+-NTA-agarose affinity chromatography. Briefly, cells were pelleted at 3000 relative centrifugal force (rcf) at 4°C for 15 min, resuspended in lysis medium (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 1× protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche], 2 mM DTT, and 1 mg/mL lysozyme) and incubated with slight shaking for 15 min at 4°C. Cells were broken by three cycles in a microfluidizer (M-110P, Microfluidics), and insoluble material was pelleted by centrifugation (10 min, 20,000 rcf, 4°C). The pellet containing inclusion bodies was stored at −20°C for the purification of denatured protein for rabbit immunization (see below). The lysate supernatant containing soluble proteins was incubated with Ni2+-NTA resin (MN Protino) for 2 h at 4°C on a spinning wheel. The resin was collected by centrifugation (200 rcf, 1 min), resuspended in lysis medium, and washed five times with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, 2 mM DTT, and 0.5% (v/v) Triton X-100 and five times with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 40 mM imidazole, and 2 mM DTT. Proteins were eluted at 4°C in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, and increasing imidazole concentrations (100, 250, and 500 mM). Protein in each elution fraction was measured using a Bradford Assay reagent (Bio-Rad). Protein-enriched fractions were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra Centrifugal Filter Units 3 kD MWCO, then exchanged into 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10% (v/v) glycerol, and 2 mM DTT using NAP-5 (GE Healthcare) columns. Final protein content was quantified using the Bradford reagent. Samples collected during the expression and purification process were monitored by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Brilliant Blue G-250 staining.

For the purification of denatured recombinant polyhistidine-tagged At-SS5 protein from inclusion bodies, the insoluble material obtained by cell lysis (see above) was resuspended in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, and 8 M urea and stirred at 4°C for 30 min. The suspension was clarified by centrifugation (10 min, 20,000 rcf, 20°C), and the resulting supernatant was incubated with Ni2+-NTA resin (MN Protino) for 90 min on a spinning wheel (∼30 rpm). The resin was then sedimented by centrifugation (500 rcf, 5 min, 4°C), washed five times with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 8 M urea and five times with 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, and 6 M urea. Proteins were eluted in 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, and 5 M urea, concentrated, exchanged into 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, and 4 M urea, and quantified as above.

A polyclonal antibody raised against At-SS5 was ordered at Eurogentec. Denatured recombinant At-SS5 purified from inclusion bodies (see above) served as antigen for the immunization of rabbits. For the purification of anti-SS5 antibodies from immune sera, recombinant polyhistidine-tagged At-SS5 protein was covalently coupled to N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated Sepharose. In brief, 1 mg of At-SS5 protein in 0.2 M NaHCO3 and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 8.3, was injected into a HiTrap N-hydroxysuccinimide-activated HP column (GE Healthcare) for covalent coupling. The column was washed and excess active groups were deactivated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Dilute rabbit immune serum was circulated over the ligand-coupled column for 1 h at 20°C. The column was then washed with PBS (137 mM NaCl, 2.7 mM KCl, 8.7 mM Na2HPO4, and 1.8 mM KH2PO4 pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.1% (v/v) Tween 20 and then with three alternating washes using 0.1 M NaHCO3, 0.5 M NaCl, pH 9.5, 0.1 M sodium acetate, and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 4. Bound antibodies were eluted from the column using a pH shift (0.1 M glycine-HCl and 0.5 M NaCl, pH 2.3) and immediately neutralized with HEPES-KOH, pH 8. The protein content in elution fractions was measured using the Bradford assay reagent. Protein-enriched fractions were pooled and concentrated using Amicon Ultra 3 kD MWCO spin filters. They were then exchanged into PBS using a NAP10 column, and 0.1% (w/v) BSA was added before storage at −80°C.

Cloning of Expression Vectors, Expression in Arabidopsis, and Imaging

The AT5G65685.1 cDNA was obtained from the RIKEN Bioresource Centre (clone pda11967). The coding sequence (CDS) was amplified from the cDNA and cloned into pCR8 using the pCR8/GW/TOPO TA cloning kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). For expression of At-SS5-YFP driven by CaMV35Spro, At-SS5:pCR8 was recombined with pB7YWG2 (Karimi et al., 2002) between CaMV35Spro and the in-frame C-terminal eYFP tag using Gateway recombination cloning technology (Invitrogen). For expression driven by UBQ10pro, At-SS5:pCR8 was recombined with pUBC-YFP (Grefen et al., 2010) between UBQ10pro and the in-frame C-terminal eYFP tag (for simplicity, we refer to this tag as YFP) using Gateway recombination cloning technology (Invitrogen). For expression of the Δcc protein version, At-SS5:pCR8 was used in QuikChange (Agilent Technologies) site-directed mutagenesis, with primers designed to delete the base pairs encoding the amino acids between W68 and D120, representing the predicted coiled coil of At-SS5. The resulting At-SS5Δcc:pCR8 vector was then recombined with pUBC-YFP as described above.

For expression of At-SS5-mCitrine under the control of the native Arabidopsis SS5pro, the full genomic construct with 1704 bp (including the 5′ UTR) upstream sequence containing the At-SS5 promoter and the complete intron-exon structure (lacking the stop codon) was amplified from genomic DNA with Gateway recombination sites and ligated into pJET1.2 using the CloneJET PCR Cloning Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Subsequent sequencing revealed a point mutation that was corrected using QuikChange site-directed mutagenesis before recombination into pDONR221 using Gateway recombination cloning technology (Invitrogen). At-SS5:pDONR221 was then recombined as previously described by Seung et al. (2018) into pH7m34GW,0, resulting in an in-frame fusion of the genomic fragment with a C-terminal mCitrine tag.

For the expression of untagged At-SS5 driven by SS5pro, the above-mentioned At-SS5:pDONR221 was modified by site-directed mutagenesis to carry a stop codon at the 3′ end of the genomic fragment. The resulting At-SS5*:pDONR221 was then recombined as described above, in this case using mCherry:pDONR P2RP3 and the destination vector pB7m34GW,0.

For expression of Os-SS5-YFP driven by CaMV35Spro, the E. coli codon-optimized gene synthesis product (Invitrogen) of ACC78131.1 was cloned into pDONR221. The coding sequence was then recombined into pB7YWG2 (Karimi et al., 2002) between CaMV35Spro and the in-frame C-terminal eYFP tag (for simplicity, we refer to this tag as YFP).

For expression of At-MRC-CFP driven by CaMV35Spro, the AT4G32190.1 cDNA was obtained from the RIKEN Bioresource Centre (clone pda01994). This clone contained an A-to-G polymorphism that led to an amino acid change (D98→G) relative to the TAIR reference sequence. The coding sequence was amplified with Gateway recombination sites and recombined into pDONR221 using Gateway recombination cloning technology. The resulting vector was used in a QuikChange mutagenesis reaction to correct the polymorphism to match the TAIR reference sequence. The corrected coding sequence was subsequently recombined into pH7CWG2 in-frame with a C-terminal CFP tag.

For expression in plants, constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains AGLØ (At-SS5 in pB7YWG2 only) or GV3101 by electroporation. For stable expression in Arabidopsis, wild-type (ecotype Col-0) and ss5 plants were transformed using a floral dip method (Zhang et al., 2006). Transformants were selected using their respective resistance markers either on soil (Basta spraying) or on 0.8% (w/v) agar plates containing one-half-strength MS salts (with 25 mg/mL hygromycin B selection) and further analysis for transgene expression by immunoblotting and/or RT-PCR. For At-SS5-YFP and At-SS5-mCitrine lines, genomic T-DNA integration sites were determined by thermal asymmetric interlaced PCR (http://www.protocol-online.org/cgi-bin/prot/view_cache.cgi?ID=3615), and homozygous offspring were selected by PCR-based genotyping. Homozygous lines were used for all experiments except those involving At-SS5Δcc-YFP- and Os-SS5-YFP-expressing plants, which were performed on segregating but Basta-resistant T2 individuals, and those involving untagged At-SS5-expressing plants as well as At-SS5-YFP-expressing ss5-2 and ss5-4 plants, which were performed on Basta-resistant T1 individuals.

To determine the subcellular localization of SS5, leaf tissue from 35-d-old Col-0 plants expressing At-SS5-mCitrine was imaged with a Zeiss LSM780 confocal imaging system. The specimens were sequentially excited with either 514-nm (mCitrine) argon or 633-nm (chlorophyll) helium-neon lasers. Images were acquired using filters ranging from 519 to 600 nm (mCitrine) and 647 to 721 nm (chlorophyll). At least 20 regions of interest from two independent transgenic lines were imaged.

For fluorescence detection in whole Arabidopsis rosettes, 2-week-old seedlings grown on 0.8% (w/v) agar plates containing one-half-strength MS salts were imaged using a fluorescence stereomicroscope (Leica M205 FCA) and the filter set ET-YFP. Images were adjusted using Fiji (Schindelin et al., 2012). Backgrounds were subtracted using a sliding paraboloid with a rolling ball radius of 300 pixels, and a specific look-up table was applied with the minimum and maximum set to 9 to 199 for the overview images and 12 to 255 for the closeup images.

Transient expression in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) was performed as described by Sharma et al. (2018), except that the tobacco plants were grown and incubated after infiltration under a 12-h-light/12-h-dark cycle. The specimens were analyzed using a Zeiss LSM780 confocal imaging system using either 514-nm (YFP) and 458-nm (CFP) argon or 633-nm (chlorophyll) helium-neon lasers. Image acquisition was done sequentially using filters ranging from 526 to 624 nm (YFP), 463 to 509 nm (CFP), and 647 to 721 nm (chlorophyll). For protein colocalizations, at least 20 regions of interest were imaged from two independent biological replicates.

Two-Step Endpoint RT-PCR

For cDNA preparation, snap-frozen leaf tissue was homogenized for 1 min (Retsch mixer mill at a vibration intensity of 30 s−1 using glass beads) and immediately mixed with TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). After the addition of ice-cold chloroform and mixing, samples were incubated at 20°C for 3 min and then centrifuged (15 min, 4°C, 12,000 rcf). The aqueous phase was mixed with ice-cold isopropanol and incubated at 20°C for 10 min. RNA was pelleted by centrifugation (10 min, 4°C, 12,000 rcf), washed twice with cold 75% (v/v) ethanol (with centrifugation in between, 3 min, 4°C, 12,000 rcf), dried, and dissolved in water. Equal amounts of total RNA were digested using DNase I (Roche) and subsequently used for first-strand cDNA synthesis from poly(A)-tailed mRNA using the RevertAid Reverse Transcription Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and oligo(dT)18 primers. cDNA was used as a template for endpoint PCR with 35 cycles. SS5 RT-PCR primers were designed such that at least one of the two primers in each reaction spanned two exon borders.

In Vitro Activity Assay

Reactions of 1 μg of recombinant protein and 1.5 mg of hydrated waxy maize (Zea mays) starch in 100 mM Bicine-KOH, pH 8, 25 mM KCH3CO2, 2 mM MgCl2, 5 mM DTT, 0.05% (w/v) BSA, and 125 nM ADP-Glc [D-glucose-14C(U)] were incubated on a rotating wheel at 20°C. Reactions were stopped by the addition of SDS to a final concentration of 3.3% (w/v). Starch was collected by centrifugation (3 min at 20,817 rcf), washed once with water, and subsequently resuspended in water. The amount of radioactivity incorporated into the starch by recombinant protein activity was measured by scintillation counting. Three experimental replicates (N) were performed for each protein/control reaction.

In Vitro Starch Binding Assay