Abstract

Bones are structurally heterogeneous organs with diverse functions that undergo mechanical stimuli across multiple length scales. Mechanical characterization of the bone microenvironment is important for understanding how bones function in health and disease. Here, we describe the mechanical architecture of cortical bone, the growth plate, metaphysis, and marrow in fresh murine bones, probed using atomic force microscopy in physiological buffer. Both elastic and viscoelastic properties are found to be highly heterogeneous with moduli ranging over three to five orders of magnitude, both within and across regions. All regions include extremely compliant areas, with moduli of a few pascal and viscosities as low as tens of Pa·s. Aging impacts the viscoelasticity of the bone marrow strongly but has a limited effect on the other regions studied. Our approach provides the opportunity to explore the mechanical properties of complex tissues at the length scale relevant to cellular processes and how these impact aging and disease.

Significance

The mechanical properties of biological materials at a cellular scale are involved in guiding cell fate. However, there is a critical gap in our knowledge of such properties in complex tissues. The physiochemical environment surrounding the cells in in vitro studies differs significantly from that found in vivo. Existing mechanical characterization of real tissues is largely limited to properties at larger scales, structurally simple (e.g., epithelial monolayers), or non-intact (e.g., through fixation) tissues. In this article, we address this critical gap and present the micromechanical properties of the relatively intact bone microenvironment. The measured Young’s moduli and viscosity provide a sound guidance in bioengineering designs. The striking heterogeneity at supracellular scale reveals the potential contribution of the mechanical properties in guiding cell behavior.

Introduction

It is increasingly clear that mechanical properties and forces play an essential role in controlling many aspects of cell biology of tissues and organs, including growth, migration, differentiation, homeostasis, and communication (1). How these fundamental cellular processes are influenced by such forces requires an understanding of the mechanical properties at a subcellular scale but in the context of the tissue, organ, or even the whole organism. Obtaining this information is particularly challenging as most traditional methods for tissue processing (e.g., sectioning) or fixation radically change the mechanical properties of at least part of the structure (e.g., by freezing and thawing). Similarly, obtaining the relevant spatial and temporal resolution with sufficient force sensitivity to systematically determine the mechanical variation at the different cell and tissue scales requires new specialized approaches. Here, we present an atomic force microscopy (AFM)-based approach for tackling these issues, allowing the study of bones, a unique and mechanically complex organ.

Bone tissue consists predominantly of two types of bone, cortical and trabecular. The cortical bone (also known as dense bone) is structurally compact and bears the load of the body’s weight. The trabecular bone (also known as cancellous bone or spongy bone) has a more loosely organized structure and a high metabolic activity (2). Both types of bone contain inorganic (bone mineral and water) and organic (bone cells and matrix) components that form complex, interconnected structures (3). In addition to being central to mechanical support, bone contains bone marrow, which plays a significant role in mammalian physiology through hematopoiesis and by regulating immune and stromal cell trafficking (4). Bone tissues undergo continuous dynamic remodeling in response to changes in mechanical loading and during the homeostatic repair of microdamage occurring through normal “wear and tear.” The balance between bone deposition and resorption is orchestrated by bone cells, called osteoblasts and osteoclasts, respectively (2,3). Osteoblasts are derived from mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and osteoclasts are derived from hematopoietic stems cells (HSCs), both of which are resident in bone marrow (4). In addition there are a multitude of progenitor cells, immune cells, stromal cells, and adipocytes involved in maintaining the homeostasis of bone.

The mechanical properties of bone are fundamental to the function of the skeleton (5), and changes in bone loading can influence bone turnover, a process whereby bone formation and absorption is in physiological balance, preventing the net gain or loss of bone tissue (6). Investigations of bone mechanics are necessary to fully understand how the mechanical properties of the bone microenvironment (BMev) influence the biological functions such as bone turnover and have been well developed in recent decades. In vitro models mimicking the BMev are commonly used to study the role of mechanical properties in bone function and related diseases, such as cancer-induced bone metastasis (7). However, these in vitro models do not fully recapitulate the complexity of the in vivo BMev and hence lack fundamental components of the underlying biology (7).

Numerous studies using a variety of techniques have characterized the mechanical properties of bone at multiple length scales. Elastic and viscoelastic studies on both cortical and trabecular bones generally give Young’s/shear moduli in the GPa range, though the results vary because of different experimental conditions (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13). The Young’s/shear modulus of trabecular bone is slightly lower than that of the cortical bone and occasionally as low as 10 s–100 s MPa (14,15). The growth plate is more compliant than both cortical and trabecular bone tissues, with the Young’s modulus ranging from 300 kPa to 50 MPa (16,17). In contrast, most studies on bone marrow have considered it as a purely viscous tissue, reporting viscosity values ranging from below 1 to 100 Pa·s (18, 19, 20).

The structural complexity of bone samples can hinder accurate mechanical monitoring. A number of approaches have been taken to overcome this through freezing (21), dehydration (22), jet washing (23), polishing (8,13), and homogenizing (24) in addition to sectioning or fracturing. Although differences in the mechanical properties of the BMevs may be extracted from samples prepared via these methods, such treatments substantially modify the surface structures (23) and consequently cause a shift in the measured mechanical properties (10,13). However, the ability to quantify the mechanical properties of tissues at different length scales is critical in building models for theoretical simulations or in tissue engineering to replicate key features of such tissues. A recent study on intact bone marrow demonstrated both the feasibility and advantages of mechanical measurements using minimally deconstructed samples (25). In contrast to other studies, this work identified that the bone marrow is predominantly elastic and suggested that the extracellular matrix contribution to the mechanical properties from fresh samples is essential to explain the observed heterogeneity. The accessible scale in (25) was not sufficient to reveal the mechanical heterogeneity of bone and suggested that techniques suitable for smaller scale characterization are necessary.

Several methods to evaluate the local (i.e., cellular or subcellular) mechanical properties of biological tissues have emerged over the last decade, including optical (26) and acoustic (27) techniques. However, the structural and mechanical heterogeneity of the BMev makes the application of these approaches particularly challenging. AFM enables characterization at length scales ranging from nm to tens of μm (28), which is of particular relevance for understanding the biological mechanisms arising at the molecular and cellular level.

Here, we focused on measuring the subcellular mechanical properties of the nonload-bearing components of untreated bone on the internal surfaces (except for longitudinal splitting, which is necessary to access the tissue). Mechanical measurements were made using colloidal probe AFM, as opposed to nanoindentation (13,22) or AFM with conventional sharp probes (9, 10, 11,16), because of the extreme softness of nonmineralized components in the BMev. Point measurements were performed randomly over a macroscale (>100 μm) of bone surfaces. Both the elastic and viscoelastic properties of different regions of the BMev were quantified by fitting data obtained from force-distance and creep (i.e., strain relaxation) curves acquired with the AFM with appropriate mechanical models. Bones from young (6–8 weeks) and mature (11–13 weeks) mice were compared to determine any mechanical changes due to age-associated skeletal maturation. Finally, AFM force mapping was used to collect images (maximal size 100 × 100 μm2) that represented the heterogeneity of the BMev morphology and mechanics at a supracellular scale (from 5 to 100 μm). The implications of our findings for the potential correlation with biological functions in bones are also discussed.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All experiments involving animals were approved by the University of Sheffield Project Applications and Amendments (Ethics) Committee and conducted in accordance with UK Home Office Regulations under project license number 70/8964 (N.J. Brown). Immunocompetent BALB/c female mice (Charles River Laboratories, Margate, UK) were housed in a controlled environment with a 12-h light/dark cycle, at 22°C. Mice had access to food and water ad libitum (Teklad Diet 2918, Envigo, Bicester, UK). A total of 23 mice were used in these studies.

Bone sample preparation

Femurs from both young (6–8 weeks old, nine bones from seven mice) and skeletally mature (11–13 weeks old, 24 bones from 16 mice) mice were used in this study. Data from mice at both ages were pooled together, apart from where the influence of age (mature skeleton) on mechanical properties was quantified. The mice were culled by cervical dislocation, and the hind limbs were detached from the pelvis at the femoral head. Muscle tissue connected to the bone was removed, and the femur was separated from the tibia at the knee joint. The dissected femurs were placed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) at 4°C. Each bone was split immediately before mechanical measurement. The majority of measurements were completed within 12 h of culling, but on occasion (because of the length of time taken for AFM evaluation), bone measurements were made the day after cull after storing the (unsplit) bone overnight in PBS at 4°C. All measurements were completed no longer than 36 h postcull. Including data obtained from bones stored overnight had negligible effects on the resultant mechanical properties (discussed in the Supporting Materials and Methods). A custom designed tool with a razor blade (Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods and Figs. S1–S10, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material) was used to longitudinally fracture the bone, which was immobilized on a platform using a two-component dental impression putty (Provil Novo Light, Kulzer, Basingstoke, UK). The split bone was then immersed in PBS and immobilized in a petri dish (Techno Plastic Products, Trasadingen, Switzerland) with the same dental impression material. Care was taken to maintain hydration of the exposed bone surface during the entire process.

Colloidal probe cantilever preparation

Rectangular Si3N4 cantilevers with a nominal spring constant of 0.02 N/m (MLCT cantilever B, Bruker, Billerica, MA) were used for all AFM measurements. A polystyrene microsphere with 25-μm diameter (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was attached to the cantilever using a UV-curing adhesive (NOA 81; Norland, Cranbury, NJ), using an AFM (Nanowizard III, JPK Instruments, Berlin, Germany) and combined with an inverted optical microscope (Eclipse Ti, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan) as a micromanipulator. Before attachment of the colloidal probe, the spring constant of each cantilever was determined in air using the thermal noise method (29). To prevent strong nonspecific binding between the probe and sample surface, the cantilever with attached colloidal probe and cantilever holder were passivated by 20-min immersion in 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich). Excess bovine serum albumin was removed by washing with 5 × 1 mL PBS.

AFM force spectroscopy and mapping

AFM measurements were all performed on a Nanowizard III system (JPK Instruments) using a heated sample stage (35–37°C). The cantilever deflection sensitivity was calibrated before each measurement, from the hard contact regime of force-distance curves (average of 10 repeated curves) obtained from a clean petri dish containing PBS. Prepared bone samples in PBS (Fig. 1 a) were then mounted on the sample stage and probed after the temperature of the liquid had stabilized. Force-distance curves (Fig. 1 b) were acquired at randomly selected positions from different regions of interest toward the distal end of each femur, as shown in Fig. 1 a. For the majority of samples, 5–10 positions within each BMev region were measured from each femur, but on occasion, the number varied beyond this range depending on sample quality (e.g., surface roughness). The approach speed was 1 μm/s unless otherwise stated. This low speed ensured that cantilever bending due to the hydrodynamic effect was minor (i.e., the separation of baselines in the approach and retract curves was minimal). Subsequently, curves with 3 s dwell under constant force (0.5 nN), i.e., creep curves, were also acquired from the same position (Fig. 1 d). For both force-distance and creep curves, a minimum of three measurements were taken at each location.

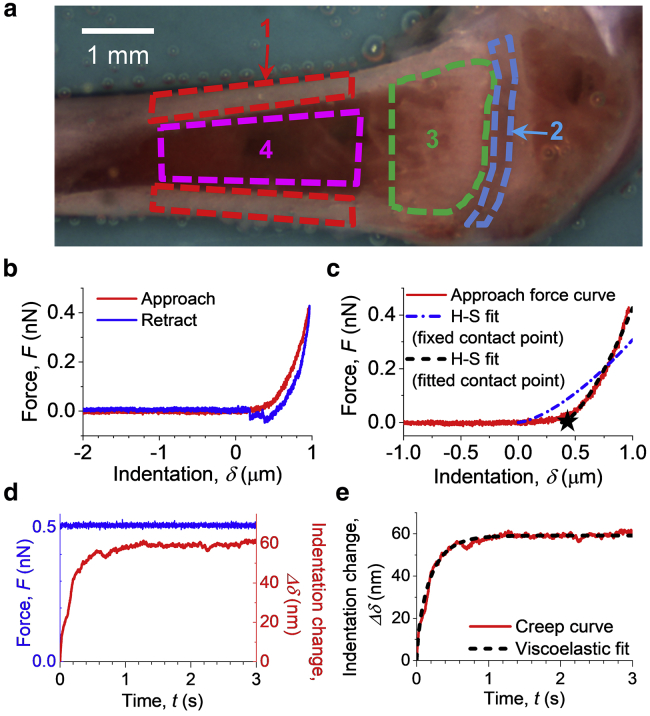

Figure 1.

Method for measuring the mechanical properties on internal bone surfaces. (a) Bright field image of a prepared bone surface for AFM characterization. Four regions of interest are indicated by colored dashed lines: 1) cortical bone (red), 2) the growth plate (blue), 3) the metaphysis (green), and 4) bone marrow in diaphysis (magenta). (b) An example of the force (F) versus indentation (δ) curve obtained during AFM probe approach (red) and retract (blue) taken on the bone surface. Negative indentation represents tip-surface distance before contact. The contact position (δ = 0) was determined from the approach curve using the triangle thresholding method described in the Supporting Materials and Methods. (c) Examples of Hertz-Sneddon (H-S) model fits to the approach segment of a force-indentation curve (red). H-S fit either using a fixed contact point (blue dash-dotted line) determined using the triangle thresholding method (described in the Supporting Materials and Methods) or with the contact point as a free fitting parameter (black dashed line). The star shows the position of the contact point determined by the fit. (d) An example of the creep curve (Δδ versus t) obtained from the dwell segment of a force curve taken on the bone surface. The applied force (blue) was held constant for 3 s, whereas the indentation depth increased (red) because of the material being viscoelastic rather than purely elastic. (e) Example of the viscoelastic model fit (black dashed line) on a creep curve (red line). To see this figure in color, go online.

A two-dimensional array of force-distance curves (i.e., an AFM map, one force curve per pixel) was then produced at randomly selected areas in the different bone regions, with 30 μm/s approach speed. The faster approach speed for force maps was chosen to minimize data collection time and consequent degradation of the sample. Before obtaining maps for analysis (typically 1–1.6 μm per pixel), low resolution “survey” maps (10–15 μm per pixel) were collected to ensure that the major features in the selected region could be mapped without exceeding the 15-μm Z range of the AFM.

All AFM measurements (force-distance curves, creep curves, and force maps) on a single bone sample could typically be collected in 2–6 h. The measured bone surfaces were stable during this time (i.e., there was no significant dissociation or significantly different features in force curves observed). Reference force-distance curves were acquired on a petri dish at the end of the measurements to check for colloidal probe contamination, with no significant contaminants (expected to manifest as strong adhesive features in the retract segment of the curves) found.

Raw data were exported as .txt format using JPK Data Processing and imported into customized algorithms in MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA) (generated in-house by X. Chen) for all subsequent analyses. Data processing scripts are available upon request.

Processing and analysis of force-distance curves

Raw force-distance curves were first converted into force (F)-indentation (δ) curves (Fig. 1 b) by applying a baseline correction, determining the contact point and subtracting the cantilever deflection from the Z displacement in the contact regime (see Fig. S1, b–e). Curves were fitted to a Hertz-Sneddon model (30) using a custom MATLAB (The MathWorks) routine, with the Young's modulus (EH-S) and a virtual contact point as free fitting parameters (see Supporting Materials and Methods). The EH-S at any measured position was determined by the mean value resulting from fitting to all repeated F-δ curves at the same position, unless otherwise specified. The quality of F-δ curves (i.e., tilt in baselines) and the fitting quality variation only had a minor impact on the results, as discussed in the Supporting Materials and Methods. It is important to note that the analysis described in this section implicitly assumes that the mechanical response of the BMev is purely elastic.

Processing and analysis of creep curves

Raw force (F)-time (t) curves from the dwell segment of force-distance curves were checked and discarded if the force could not be maintained constant by the feedback loop. The Z displacement value at the start of the dwell segment was subtracted from the displacement-time curve to yield an indentation variation (Δδ)-time (t) curve (creep curve). This was fitted to both a standard linear solid (SLS) model (Fig. S1 f) and a Kelvin-Voigt (K-V) model (Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods and Figs. S1–S10, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material), based on the theory developed by Cheng et al. (31) (see Supporting Materials and Methods). The instantaneous elastic modulus (E1), delayed elastic modulus (E2), and viscosity (η) were free fitting parameters using the SLS model, and the Young’s modulus (EK-V) and viscosity (η) were free fitting parameters using the K-V model. Results were obtained from the mean value of repeated measurements at each position, and those with low fit quality (R2 < 0.9) were discarded if not specified.

Processing of AFM map data

Three types of maps that graphically represented topography and mechanical properties of the scanned areas were generated from the AFM maps. First, the trigger point map was constructed from a vertical position where the interaction force between the probe and the sample reached the trigger value. This represents the topography of the surface, including the indentation of the probe into the sample. Second, the contact point map was constructed from the vertical position where the probe was deemed to have made initial contact with the sample surface, determined from the contact point found for every force curve in the map using the triangle thresholding method, as shown in Fig. S1 b. This represents an approximation to the topography at zero load and indentation. Third, the elastic map was constructed from the Young’s modulus EH-S extracted from all force curves in the map using the Hertz-Sneddon model with a fitted contact point. For both the contact point map and the mechanical map, pixels with curves that could not be properly fitted because of not having a clear noncontact baseline, contact point, and monotonic contact regime were considered as “missing data” and colored black in the figures.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro software. A normality test was applied to all distributions before any further analysis. Data were then analyzed by the Kruskal Wallis test for comparison between different groups. A statistically significant difference was defined as p < 0.05. The number of mice in each group used to collect data was above the minimum required for statistical comparison, calculated using the resource equation approach (32).

Results and Discussion

This study aims to establish a benchmark for characterizing the micromechanical architecture of bones. Therefore, a healthy bone model (i.e., wild-type mouse strain at a relatively young age) was selected. Due to our research interest in breast cancer metastasis, bones from only female mice were characterized. Four regions of interest (Fig. 1 a) within the BMev were selected on the surface of split bones for AFM characterization because of their diverse composition and function: 1) cortical bone, 2) growth plate, 3) metaphysis, and 4) bone marrow in the diaphysis. The four regions of interest are shown by colored outlines in the bright field image (Fig. 1 a). In long bones such as the femur, the growth plate (also known as the epiphyseal plate or physis) is found at each end. This is where longitudinal bone growth takes place and is composed of a large number of chondrocytes and proteinaceous matrix (17). The narrow portion located just below the growth plate, the metaphysis (2), was also examined. Previous preclinical in vivo studies from our group have identified this as the predominant region where circulating metastatic cancer cells home to and colonize in bone (33,34). In the metaphysis, measurements were made on either the trabecular bone tissue or adjacent soft tissue in the surrounding marrow. In the diaphysis, we measured both the cortical bone (outer shaft of the long bone) and the central bone marrow cavity. Cortical bone is composite and highly mineralized, playing a crucial role as the scaffold to support the whole body (35). Bone marrow, containing the pluripotent stem cells, is the major hematopoietic organ and a primary lymphoid tissue (36). The four regions of interest contain the majority of the different tissue types in bone; thus, characterization of these regions provides a comprehensive analysis of the bone mechanical architecture as a benchmark for subsequent studies. Meanwhile, these regions of interest are distinct in the bright field image (Fig. 1 a), ensuring easy targeting during mechanical characterization.

Only bones with an acceptably smooth surface topography after splitting were used for AFM measurements. However, even on these specimens, the height range of the surface profile could still vary by several hundred micrometers across the whole bone. Tilt or curvature of the split surface occasionally caused fouling of the cantilever or cantilever holder on parts of the bone that were higher than the region of interest. In these cases, it was not possible to measure all regions of interest on the same specimen.

Point force-indentation measurements reveal mechanical heterogeneity spanning orders of magnitude over each of the different regions of the BMev, with all regions containing very compliant (1–10 Pa) areas

To probe the overall mechanical profile for each bone region, we first applied point force (F)-indentation (δ) measurements at randomly selected positions within the specified region. An example F-δ curve acquired on the surface of a split bone is shown in Fig. 1 b (see Fig. S1, b–e for details of conversion of raw deflection-distance curves to F-δ curves). In the majority of curves, features associated with plastic deformation (yield points, plateaus, etc.) were not observed, indicating that elastic or viscoelastic analyses were appropriate. For simplicity, the Young’s modulus EH-S, together with a virtual contact point, were obtained from Hertz-Sneddon model fits to the F-δ curves (Fig. 1 c), assuming a purely elastic response. Data include bones from both young and mature mice.

Histograms of EH-S for each bone region are shown in Fig. 2 (note the logarithmic scale of the horizontal axes) and follow neither normal nor log-normal distributions. The median EH-S is 1) cortical bone: 0.29 kPa, 2) growth plate: 91 Pa, 3) metaphysis: 17 Pa, and 4) bone marrow: 6.7 Pa. The mean EH-S is 1) cortical bone: 2.7 kPa, 2) growth plate: 0.19 kPa, 3) metaphysis: 0.42 kPa, and 4) bone marrow: 0.14 kPa. These data indicate that the BMev is very compliant.

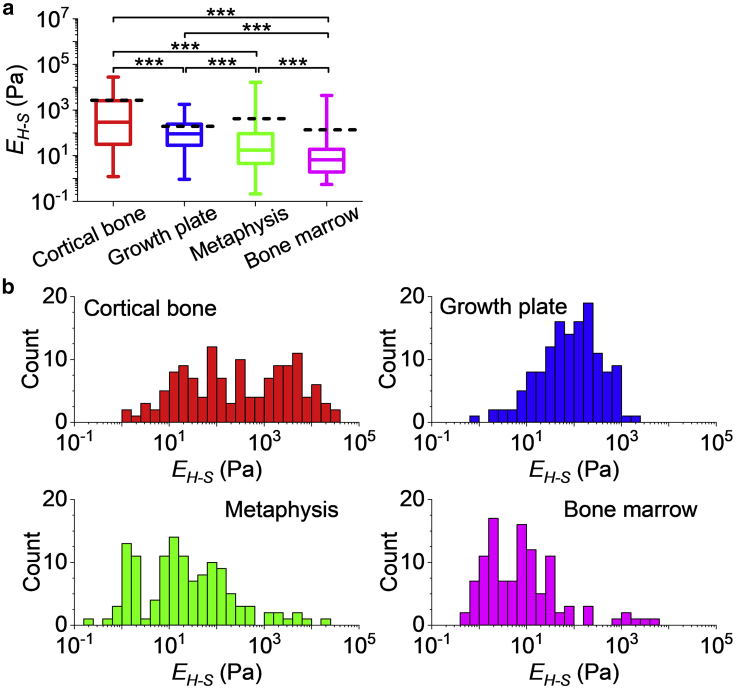

Figure 2.

Elastic properties of different bone regions. (a) The Young’s modulus (EH-S) of different regions in the BMev was calculated using the Hertz-Sneddon model with fitted contact point. The central box spans the lower quartile to the upper quartile of the data. The solid line inside the box shows the median, and whiskers represent the lower and upper extremes. The mean values are indicated by black dashed lines. Data were obtained at randomly selected positions within regions of interest on bones from both young and mature mice. The Young’s modulus reported at each position is the mean value of individual fits to all force-indentation curves taken at that location. Curves with strongly tilted baselines (i.e., db > dc/4, as in Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods and Figs. S1–S10, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material) were discarded. Results from low quality fittings (i.e., R2 < 0.9) were also discarded. The significance of statistical comparisons using the Kruskal Wallis method have been indicated above each group of boxplots (∗∗∗p < 0.001). (b) Histograms of the EH-S of different bone regions, as in (a). The corresponding histograms in linear scale are presented in Fig. S2. Data were collected from at least n = 17 mice (cortical bone n = 18, growth plate n = 19, metaphysis n = 20, and bone marrow n = 17 mice). To see this figure in color, go online.

The distributions of EH-S are very broad in all regions of interest, covering several orders of magnitude (see Fig. S2 for data on a linear scale), revealing the extreme mechanical heterogeneity within each region, which is consistent with the known heterogeneous structure of bone (8,17,21).

The mechanical distributions vary significantly between different bone regions (p < 10−4 using the Kruskal Wallis test). Such distributions are not normal and vary in shape from region to region. No commonly used parameters are sufficient to quantify the differences in heterogeneity in different bone regions. However, qualitative differences are directly visible from the histograms shown in Fig. 2 b. Histograms of EH-S measured for cortical bone show a wide distribution that lacks a sharp peak with a large portion of data at relatively high EH-S (i.e., EH-S > 103 Pa), compared with the mechanical distribution of the other bone regions measured. This is in agreement with the high level of mineralization in cortical bone (3). The mechanical distribution of both the growth plate and bone marrow are narrower, reflecting the more homogeneous composition and structure compared to other bone regions (37). The measured modulus of the metaphysis covers the widest range because of the presence of both bone tissue and bone marrow in this region, enhancing the structural and consequently the mechanical heterogeneity.

Our approach has limits in acquiring data beyond the range shown in the histograms. At the low stiffness end of the distribution (Pa), errors are dominated by inaccuracies in determining the contact point and tend to lead to an overestimate of the extracted moduli, so the distributions may extend to still lower moduli. At the high stiffness end (100 s kPa), there is insufficient indentation at the maximal (trigger) forces used, which may lead to an underestimate in the extracted moduli. As a control, the EH-S extracted from hard wall F-δ curves, from the polystyrene petri dish (expected EH-S ∼3 GPa) under the same experimental conditions, does not exceed 10 s to 100 s kPa, which is the upper limit of EH-S using the current AFM setup (that is focused on measuring soft components). The experimental setup is not sensitive to the GPa moduli of calcified cortical and trabecular bone previously described (8, 9, 10), as this is beyond the scope of this study.

However, our approach has the important advantage of being able to measure the subcellular properties of soft tissues, i.e., the cellular microenvironment. The Young’s moduli found in the current study are orders of magnitude lower than the values reported in the majority of previous studies (8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17,22). Direct comparison is difficult, but the ability to measure at the length scale of the cellular components is likely to contribute to the difference. Previous experiments performed with non-AFM indentation approaches (13,22) normally average over large areas (hundreds μm2) and thus are unable to determine the properties of the smaller scale. Meanwhile, the low spring constant cantilever and relatively large contact radius probe were selected for use in the current study after extensive preliminary experiments and provide sufficient force sensitivity to assess subcellular scale mechanics in soft tissue. This is in contrast to using conventional sharp AFM probes and enables accurate measurements of the soft components in the BMev, rather than simply being able to obtain measurements from the calcified regions (8, 9, 10).

In previous studies, mechanical characterization of the bone marrow is reported to be distinct from other regions within the BMev. The marrow region is traditionally considered as a viscous fluid (19), and there are only a few studies describing the elastic properties. However, a recent study suggested that the bone marrow is predominantly elastic and reported an effective Young’s modulus ranging from 0.1 to 10.9 kPa measured at physiological temperature (25). This value obtained from porcine bone is similar to that obtained in the current study from murine bone, the difference in the resultant moduli most likely due to the use of rheological measurements instead of indentation. It is important to note that the bone marrow used both in the previous (36) and the current study is essentially intact with no processing (such as fixation) before measurement of the mechanical properties.

The H-S model with fitted contact point does not fit the entire F-δ curve perfectly (Fig. 1 c). This is likely because the H-S model assumes that the probed material is homogeneous and linearly elastic, whereas the BMev is known to be structurally heterogeneous (3) (additional errors in the model are discussed in the Supporting Materials and Methods). Elastic models describing discontinuous materials (e.g., cell-polymer brush model (38)) may be helpful for improved determination of the elasticity of the BMev. Also, the BMev is suggested to be a viscoelastic material in many studies (12,22). Consequently, the H-S model assuming pure elasticity is not sufficient to describe the mechanical properties. The resulting measured Young’s modulus is likely to be velocity dependent and should only be compared directly with other measurements made at a similar velocity. To explore this further, we characterized the viscoelastic properties by indentation-creep measurements.

Point indentation-creep measurements demonstrate that the BMev can be described as a heterogeneous viscoelastic K-V solid

To extract the viscoelastic properties of the BMev, an equation based on a three element SLS model (Fig. S1 f) developed by Cheng et al. (31) was first used to fit the indentation change (Δδ) versus creep time (t) curves (Fig. 1, d and e). The Δδ-t curves from 90% of the total 779 measured positions in all BMev regions of bones from both young and mature mice could be fitted well by this simple viscoelastic model (R2 > 0.9). This supports the premise that the BMev is viscoelastic rather than purely elastic.

The moduli presenting both the instantaneous elastic behavior (E1) and the delayed elastic behavior (E2) could be obtained from the SLS model (Fig. S3). It is notable that in the majority of cases, E1 was significantly higher than E2. For all positions that were well fitted by the SLS model, 93% have E1 > 10E2, and 84% have E1 > 100E2 (Fig. S3 d). This indicated that any strain caused by the instantaneous elasticity was negligible. Thus, the complete SLS model is largely unnecessary and can be further simplified to a two-element K-V model (Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods and Figs. S1–S10, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material). The Δδ versus t curves were then fitted to the simplified equation (for development and validation, see the Supporting Materials and Methods) based on the K-V model. Compared to using the SLS model, a similar number of measured positions could be fitted well (R2 > 0.9). This suggests that the K-V model is sufficient to describe the viscoelasticity, and the majority of BMev acts like a K-V solid in nature. A K-V-type solid is predominantly a viscous liquid at short timescales and predominantly an elastic solid at long timescales. This is biologically meaningful in the context of the BMev. Being a K-V-type solid ensures fast energy damping through the BMev in reaction to any abrupt mechanical loading as well as maintaining a stable shape in the long term as part of the body scaffold.

The Young’s modulus determined by the K-V model EK-V and viscosity η for the different bone regions are shown in Fig. 3. The median EK-V for the different regions of interest in the BMev, represented in Fig. 3 a, are 1) cortical bone: 0.86 kPa, 2) growth plate: 1.5 kPa, 3) metaphysis: 0.40 kPa, and 4) bone marrow: 0.14 kPa. The mean EK-V for the different regions of interest in the BMev are 1) cortical bone: 4.2 kPa, 2) growth plate: 2.9 kPa, 3) metaphysis: 1.7 kPa, and 4) bone marrow: 0.52 kPa. These values are significantly higher than the EH-S values obtained from the pure elastic fit (see Fig. S4, cortical bone: p < 0.01, growth plate: p < 10−33, metaphysis: p < 10−18, marrow: p < 10−22), which is not surprising because the latter does not take into account the presence of the viscous effect. The EK-V distributions of all BMev regions (Fig. 3 c) cover several orders of magnitude, with significant differences (p < 0.05) found between the bone regions.

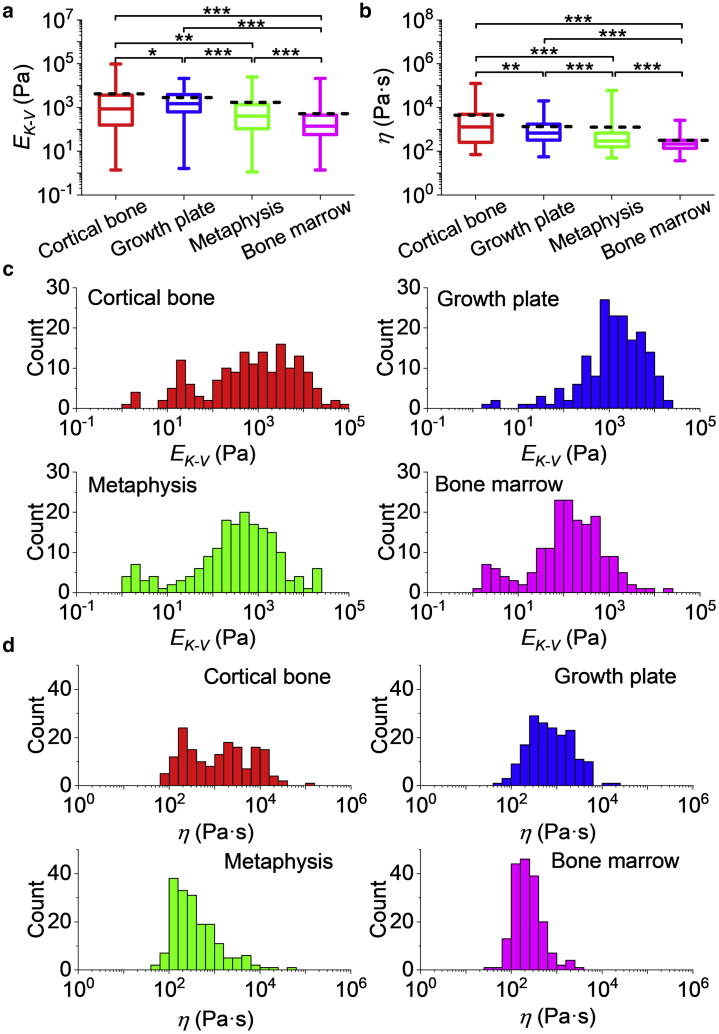

Figure 3.

Viscoelastic properties of different bone regions. (a) The Young’s modulus EK-V and (b) viscosity η of different bone regions calculated from fits to creep curves using the viscoelastic K-V model. The central box spans the lower quartile to the upper quartile of the data. The solid line inside the box shows the median, and whiskers represent the lower and upper extremes. The mean values are indicated by black dashed lines. Data were obtained at the same positions as elastic measurements (Fig. 2) from all mice bones. The results are from the mean value from all repeated measurements at each position. Results from low quality fittings (i.e., R2 < 0.9) were discarded. The significance of statistical comparisons using the Kruskal Wallis method have been indicated above each group of boxplots (∗p < 0.05; ∗∗p < 0.01; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Histograms of (c) EK-V and (d) η of different bone regions are also shown. Data were collected from at least n = 17 mice (cortical bone n = 18, growth plate n = 19, metaphysis n = 20, and bone marrow n = 17 mice). To see this figure in color, go online.

The median resultant viscosity η of different BMev regions are represented in Fig. 3 b as 1) cortical bone: 1.3 kPa·s, 2) growth plate: 0.68 kPa·s, 3) metaphysis: 0.29 kPa·s, and 4) bone marrow: 0.21 kPa·s. The mean resultant viscosity η of different BMev regions are 1) cortical bone: 4.4 kPa·s, 2) growth plate: 1.3 kPa·s, 3) metaphysis: 1.3 kPa·s, and 4) bone marrow: 0.31 kPa·s. The width of the η distribution (Fig. 3 d) is smaller than that of EK-V but still spans several orders of magnitude. Significant differences between different bone regions (p < 0.01) are also found as for the elasticity data. The creep time τ, defined as the time for the strain to decay to 1/e of its total change, can be calculated from the values of EK-V and η of each measured position by τ = 3η/EK-V. The median creep time τ of different BMev regions are 1) cortical bone: 2.2 s, 2) growth plate: 1.3 s, 3) metaphysis: 2.1 s, and 4) bone marrow: 4.1 s. The mean creep time τ of different BMev regions are 1) cortical bone: 140 s, 2) growth plate: 16 s, 3) metaphysis: 34 s, and 4) bone marrow: 36 s. The median creep time for all regions is similar to the indentation time in the elastic measurements, so creep relaxation and indentation are most likely occurring simultaneously in force-distance experiments. As such, the viscous drag force is likely to have a strong effect on the F-δ curve, especially in more compliant areas and around the contact point, where the indentation speed is highest. This is most likely the main reason for the discrepancy between the Hertz-Sneddon fit and the modulus obtained from the creep data.

It is difficult to make comparisons with the previous published studies quantifying the viscoelastic properties of the hard regions of the bone as these studies have measured the potential load bearing mechanics (i.e., mineralized regions) (12,13), whereas the current study focused on obtaining measurements from the cellular microenvironment. Studies of the metaphysis have measured trabecular bone (14,22), whereas our measurements are dominated by a more marrow-like component, which accounts for most of the surface area in the region quantified in our samples.

In contrast to the hard bone regions, the composition of bone marrow in previous studies are more comparable to the values reported here. The Young’s modulus from both the elastic (EH-S) and viscoelastic (EK-V) characterization in our study is in good agreement with the effective Young’s modulus obtained in (25). The viscosity η from rheological measurements (18, 19, 20) ranges from far below 1 to ∼100 Pa·s. However, the resultant median and mean value of the bone marrow viscosity is significantly greater (0.2 and 0.3 k Pa·s) in our study. This can be explained by both sample preparation and instrument limits. The preparation and postprocessing of the sample have been shown to affect the bone marrow viscosity. For instance, the viscosity of samples undergoing a freeze-thaw cycle before testing was lower by an order of magnitude compared to the fresh samples (20). Also, in our studies, the bone marrow was not extracted from the medullary cavity. Thus, connections of the marrow and bone tissues, and subsequently the rigidity of bone marrow structure, were maintained and relatively intact.

It is notable that viscosity is often a function of velocity and consequently varies with different measurement frequencies used in different studies. The viscosity of bone marrow has been shown to decrease as the shear rate increases according to a power law (20,25). In contrast to dynamic measurements, the quasistatic method used in our study does not cover a broad range of frequencies. This quasistatic method requires the creep time τ of the sample to be significantly larger than the time required to overcome system inertia during the transition from indentation to dwelling (∼0.05 s). As τ is correlated with both EK-V and η, the lower limit in detectable τ indicates that the resultant viscosity η using such a quasistatic method cannot be found to be much lower than the lowest values we measured (or EK-V much higher than the current highest values we measured). An alternative published method obtained the elastic modulus and viscosity from the force-indentation curves (both approach and retract) instead of using the creep curve (39). Future studies comparing the viscoelastic properties obtained from the two different methods will be useful for improving the quality of the analysis.

Skeletal maturation impacts on the subcellular mechanical properties at the macroscale of bone marrow but only has minor effects on other regions of the BMev

Bone turnover in health and disease such as osteoporosis and cancer-induced bone loss show age-dependent features (17,33,40, 41, 42). Therefore, comparing the mechanical properties of the BMev from mice at different ages will elucidate changes occurring in the mechanics of the BMev during skeletal maturation. The Young’s modulus from the elastic model, EH-S, together with the viscoelastic parameters EK-V and η were classified into two groups: data obtained from young mice (age 6–8 weeks old, blue) and mature mice (age 11–13 weeks, red) (Fig. 4, corresponding distribution histograms in Fig. S5). Two groups of data in each region were compared by the Kruskal Wallis (KW) method.

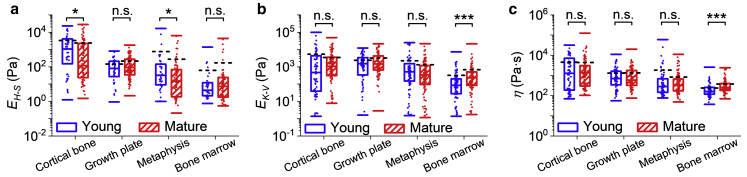

Figure 4.

Comparison of the mechanical properties of bones from young (blue) and mature (red) mice. (a) The Young’s modulus EH-S obtained from the H-S model. Results were generated by separating the data in Fig. 2 into two groups based on different ages representing differences in skeletal maturity. (b) The Young’s modulus EK-V and (c) viscosity η obtained from the K-V model. Results are generated by separating the data used in Fig. 3 into two groups based on different ages representing differences in skeletal maturity. The central box spans the lower quartile to the upper quartile of the data. The solid line inside the box shows the median, and caps below and above the box represent the lower and upper extremes. The mean values are indicated by black dashed lines. Dots represent individual data points overlaid on top of the boxplots. Data include results from both young and mature mice. The significance of statistical comparisons using the Kruskal Wallis method have been indicated above each group of boxplots (n.s., not significant; ∗p < 0.05; ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Data were collected from all bone regions in n = 8 young mice and from at least n = 9 mature mice (cortical bone n = 10, growth plate n = 11, metaphysis n = 12, and bone marrow n = 9 mice). To see this figure in color, go online.

The KW test comparing EH-S (Fig. 4 a) shows a minor yet statistically significant difference (0.05 > p > 0.03) in the cortical bone and the metaphysis, whereas the EH-S of growth plate and the bone marrow did not vary with age. For EK-V and η (Fig. 4, b and c), the KW test demonstrates a high level of significance (p < 0.001) in bone marrow but not for any other BMev region. There are differences in the statistical comparison of pure elastic fit results (i.e., EH-S) and viscoelastic fit results (i.e., EK-V and η). The main reason is most likely that the Hertz-Sneddon model does not adequately describe the BMev properties because of not considering the viscous force, especially in compliant areas such as bone marrow.

Very few studies have been performed quantifying the mechanical properties of the BMev in relation to age. Tensile tests on whole bones reported in 1976 showed only moderate differences between bones from humans at different ages (40). Recently, micro-/nanoindentation tests revealed that the mechanical properties of human cortical (41) and trabecular (42) bones were remarkably constant as a function of age. The elastic modulus of murine growth plate was reported to be significantly different between the embryonic stage and postnatal stage, age 2 weeks, but did not vary significantly through the next growth stages until adulthood (up to age 4 months) (16). These results are consistent with our findings. Dynamic stiffness of bone marrow stromal cells was significantly higher in adult horses compared to foals (43), which is in agreement with the age-dependent trend of bone marrow mechanics observed in our study.

Such comparisons reflect the impact of aging on the subcellular mechanical properties of different regions of the BMev only at macroscales. It would be helpful to integrate the impacts of aging and different length scales in future studies. Although the sample size of the young mice was adequate for statistical comparisons (32), a larger sample size would assist in consolidating our conclusion.

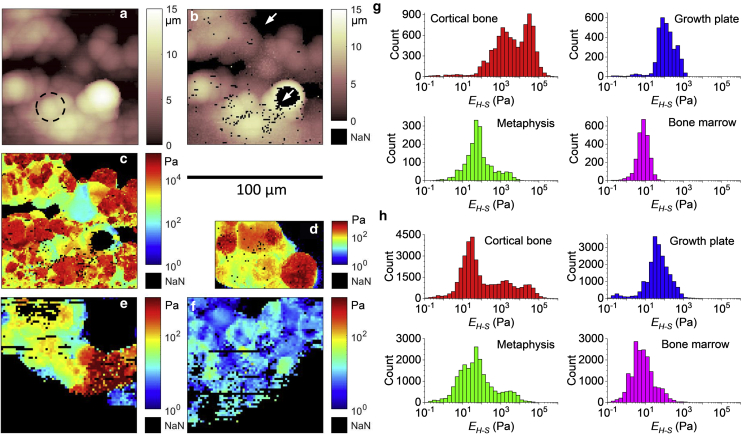

Force mapping at the supracellular scale reveals high local mechanical heterogeneity within the different regions of the BMev

The data discussed in the previous sections were from point measurements, which do not inform on the spatial distribution of mechanical heterogeneity at the cellular scale. To explore this further, we carried out AFM force mapping. The maximal area for AFM force mapping in our setup is 100 × 100 μm2 with each pixel in the map down to 1 μm2. This ensures that AFM mapping is sufficient to resolve the subcellular mechanical profile at a supracellular scale, considering the dimensions of most cells in bone (mean diameter ranging from 0.5 to ∼100 μm) (44, 45, 46).

Fig. 5, a–c shows representative maps obtained from cortical bone. The trigger point map (Fig. 5 a) reveals the surface topography of the BMev at the trigger force. Tightly packed structures are visible (as indicated by the dashed circle), the size and shape of which are consistent with those expected for individual cells. An approximation to the surface topography of the BMev at zero load is given by the contact point map (Fig. 5 b). This appears significantly smoother than the trigger point map because of the minimal indentation at the contact point and indicates that the bone surface after splitting is relatively smooth on a supracellular scale. The lateral resolution of both maps is limited by the colloidal probe and its convolution with the surface topography. Black pixels in Fig. 5 b represent missing data because of the force-distance curves at these pixels being unsuitable for fitting (see Materials and Methods). These include the large black regions indicated by arrows where the topography exceeds the lower and upper limits of the AFM’s vertical scan range. The corresponding map of EH-S is shown in Fig. 5 c. The R2 is greater than 0.9 for 54% and 0.5 for 95% of all curves in this map and independent of EH-S values. Interestingly, the mechanical heterogeneity is correlated with the topographic structures in Fig. 5, a and b and thus helps to distinguish cellular and acellular components (the former is normally stiffer because of the nuclear, cytoskeletal, and membrane components) and mineralization status (mineralized components are expected to be much stiffer). These maps clearly show the mechanical complexity of the BMev at the supracellular scale, which is likely to be important for processes such as cell migration and proliferation that are mediated by the mechanical properties of both cells and surrounding extracellular matrix (1).

Figure 5.

Mechanical heterogeneity of different bone regions at supracellular scale. (a–c) Example of AFM maps obtained from a randomly selected position on the cortical bone. (a) Topographic map showing the height at which the trigger force was reached. Dashed circle highlights an observed spherical structure. (b) Topographic map showing the height at which the probe first makes contact with the surface. The position of the contact point was determined by the triangle thresholding method as in Fig. S1 b. (c) Map of the measured Young’s modulus EH-S from all force curves in the map. Curves with strongly tilted baselines (i.e., db > dc/4, as in Document S1. Supporting Materials and Methods and Figs. S1–S10, Document S2. Article plus Supporting Material) were discarded. (d–f) Examples of EH-S maps obtained from (d) growth plate, (e) metaphysis, and (f) bone marrow. The data include values from curves with strongly tilted baselines (i.e., db > dc). For all maps in (a–f), missing data (i.e., no proper force-indentation curves could be fitted) are indicated by black pixels (white arrows in b). The scale bar for all maps is below b. (g) Histograms of the EH-S distribution compiled from the maps in (c–f). (h) Histograms of the EH-S distribution for different bone regions compiled from all AFM maps. Data in (h) were collected from at least n = 4 mice (cortical bone n = 8, growth plate n = 4, metaphysis n = 6, and bone marrow n = 8 mice), including at least five maps for each bone region. To see this figure in color, go online.

Structure-correlated mechanical heterogeneity is found in all regions of interest in this study (Figs. 5, d–f and S6) with EH-S values covering several orders of magnitude. The structures and mechanical properties reflected in the AFM maps vary from region to region and are difficult to accurately quantify as some areas are more difficult to map because of their large topography. Semiquantitative comparison of the mechanical properties of different bone regions is feasible by comparing the histograms of EH-S calculated from the maps.

The histograms of EH-S, corresponding to the Young’s modulus maps in Fig. 5, c–f, are shown in Fig. 5 g. The histograms representing EH-S obtained from all maps of each bone region (minimum five maps per region) are shown in Fig. 5 h. These histograms include data from all F-δ curves with no selection criteria for curve or fit quality. As discussed in the Supporting Materials and Methods, removal of poor curves has little effect on the distributions, so map data can be compared directly with individual curves from the point measurements (Fig. 2 b). For all regions except the cortical bone, the shape of the distribution of EH-S obtained from a single map (Fig. 5 g), all maps (Fig. 5 h), and individual curves covering the entire region (Fig. 2 b) are comparable. The comparable width of the EH-S distributions in Figure 2, Figure 5 g indicates that the degree of elastic heterogeneity at the supracellular scale is comparable to the heterogeneity at a macroscopic scale. The similar shape and peak of the EH-S distributions in Fig. 5, g and h suggest that such supracellular mechanical heterogeneity is evenly spread throughout different mapping areas within each bone region. In contrast, the histograms from cortical bones are significantly different from each other. The EH-S distribution of a single map (Fig. 5 g) covers several orders of magnitude, indicating that the mechanical properties of the cortical bone are also highly heterogeneous at the supracellular scale, as in other bone regions. However, compared to the profile of the entire cortical bone region (Fig. 2 b), the peak of EH-S distribution of the selected force map shifts by more than one order of magnitude. Also, the shape of the histogram for all maps obtained on the cortical bone are highly distinct from that of the histograms of either the selected map or the individual curves over the entire cortical bone region. This indicates that in contrast to the other bone regions studied, the mechanical architecture of a supracellular area in the cortical bone varies significantly through different mapping areas over the bone region.

It is notable that the approach speed used in force mapping was significantly increased (30 μm/s, compared to 1 μm/s in point measurements). The frequency ratio of the resonant frequency of the cantilever (a few kHz in PBS) to the frequency at which the distance is modulated (1 Hz corresponding to 30 μm/s) remains high, which ensures no violation of the fundamental Hooke’s law in force determination (47). However, the indentation time of the majority of F-δ curves in the maps is generally not greater than 0.3 s. This is significantly shorter than the mean/median creep time τ of each of the BMev regions, as described in the viscoelastic section. Within such short timescales, the BMev will be predominantly viscous as a K-V-type solid (see Supporting Materials and Methods). We should therefore regard the modulus values obtained from indentation as an effective modulus, specific to strain rate, and encompassing both elastic and viscous contributions.

Conclusions

In this work, we have used minimally processed murine bone samples from female wild-type immunocompetent BALB/c mice to quantify the micromechanical properties of four distinct regions of interest using AFM. The mechanical profile of each bone region at macroscale, revealed by point force-indentation or creep measurements using pure elastic or viscoelastic models, was found to be highly heterogeneous. The mechanical properties of different BMev regions have also shown significant differences. Moreover, aging was found to strongly impact the viscoelastic properties of the region comprising the bone marrow while having no or minimal effects in other regions of interest.

All bone regions contained extremely compliant areas (i.e., the Young’s moduli from both elastic and viscoelastic models were as low as a few pascal), and the overall moduli were much lower than the values reported from previous studies performed on individual cells in vitro, whole tissues ex vivo, or highly processed bone samples. Indeed, the viscoelastic model described the mechanical response better than the elastic model. The majority of the BMev within all regions of interest acted as a K-V-type solid.

This study demonstrates the feasibility of obtaining high-resolution AFM data and maps reflecting both three-dimensional morphology and mechanical properties from complex bone tissues. AFM maps revealed that the mechanical properties of all bone regions are highly heterogeneous at the cellular/supracellular scales, ranging over three to five orders of magnitude. Such a unique mechanical architecture may impact on a substantial number of active biological processes, such as bone remodeling, vascularization, hematopoiesis, and cancer-induced bone disease. With further improvements, such as combining with post-AFM optical images, this AFM-based system will be a powerful tool for further characterization of bones in the presence of stimuli (e.g., hormones, cancer cells, and therapeutics) or addressing mechanically relevant questions on other complex biological structures.

Author Contributions

X.C. designed the study, performed the experiments, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. R.H. prepared the bone samples, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. N.M. provided support for the experiments, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. R.J.H. improved the theoretical model, interpreted the data, and wrote the manuscript. I.H., N.J.B., and J.K.H. designed the study, interpreted the data, wrote the manuscript, and directed the project.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Keith Hunter, Dr. Ashley Cadby, and Miss Natasha Cowley (University of Sheffield) for fruitful discussions.

This research was supported by Cancer Research UK and the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (grant A21082).

Editor: Cynthia Reinhart-King.

Footnotes

Supporting Material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2020.06.026.

Supporting Citations

Refs (48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53) appear in the Supporting Material.

Supporting Material

References

- 1.Lange J.R., Fabry B. Cell and tissue mechanics in cell migration. Exp. Cell Res. 2013;319:2418–2423. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bussard K.M., Gay C.V., Mastro A.M. The bone microenvironment in metastasis; what is special about bone? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2008;27:41–55. doi: 10.1007/s10555-007-9109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morgan E.F., Barnes G.L., Einhorn T.A. The bone organ system: form and function. In: Marcus R., Feldman D., Dempster D.W., Luckey M., Cauley J.A., editors. Osteoporosis. Academic Press; 2013. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Florencio-Silva R., da Silva Sasso G.R., Cerri P.S. Biology of bone tissue: structure, function, and factors that influence bone cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2015;2015:421746. doi: 10.1155/2015/421746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morgan E.F., Unnikrisnan G.U., Hussein A.I. Bone mechanical properties in healthy and diseased states. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2018;20:119–143. doi: 10.1146/annurev-bioeng-062117-121139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robling A.G., Castillo A.B., Turner C.H. Biomechanical and molecular regulation of bone remodeling. Annu. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2006;8:455–498. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.8.061505.095721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vanderburgh J.P., Guelcher S.A., Sterling J.A. 3D bone models to study the complex physical and cellular interactions between tumor and the bone microenvironment. J. Cell. Biochem. 2018;119:5053–5059. doi: 10.1002/jcb.26774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zebaze R.M.D., Jones A.C., Seeman E. Differences in the degree of bone tissue mineralization account for little of the differences in tissue elastic properties. Bone. 2011;48:1246–1251. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2011.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tai K., Dao M., Ortiz C. Nanoscale heterogeneity promotes energy dissipation in bone. Nat. Mater. 2007;6:454–462. doi: 10.1038/nmat1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lefèvre E., Guivier-Curien C., Charrier A. Determination of mechanical properties of cortical bone using AFM under dry and immersed conditions. Comput. Methods Biomech. Biomed. Engin. 2013;16(Supp1 1):337–339. doi: 10.1080/10255842.2013.815974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asgari M., Abi-Rafeh J., Pasini D. Material anisotropy and elasticity of cortical and trabecular bone in the adult mouse femur via AFM indentation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2019;93:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2019.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bembey A.K., Oyen M.L., Boyde A. Viscoelastic properties of bone as a function of hydration state determined by nanoindentation. Philos. Mag. 2006;86:5691–5703. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pathak S., Swadener J.G., Goldman H.M. Measuring the dynamic mechanical response of hydrated mouse bone by nanoindentation. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2011;4:34–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pugh J.W., Rose R.M., Radin E.L. Elastic and viscoelastic properties of trabecular bone: dependence on structure. J. Biomech. 1973;6:475–485. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(73)90006-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Manda K., Xie S., Pankaj P. Linear viscoelasticity - bone volume fraction relationships of bovine trabecular bone. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2016;15:1631–1640. doi: 10.1007/s10237-016-0787-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Prein C., Warmbold N., Clausen-Schaumann H. Structural and mechanical properties of the proliferative zone of the developing murine growth plate cartilage assessed by atomic force microscopy. Matrix Biol. 2016;50:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2015.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villemure I., Stokes I.A.F. Growth plate mechanics and mechanobiology. A survey of present understanding. J. Biomech. 2009;42:1793–1803. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bryant J.D., David T., Lond G. Rheology of bovine bone marrow. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. H. 1989;203:71–75. doi: 10.1243/PIME_PROC_1989_203_013_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gurkan U.A., Akkus O. The mechanical environment of bone marrow: a review. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2008;36:1978–1991. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metzger T.A., Shudick J.M., Niebur G.L. Rheological behavior of fresh bone marrow and the effects of storage. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2014;40:307–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2014.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morgan E.F., Bayraktar H.H., Keaveny T.M. Trabecular bone modulus-density relationships depend on anatomic site. J. Biomech. 2003;36:897–904. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(03)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Isaksson H., Nagao S., Jurvelin J.S. Precision of nanoindentation protocols for measurement of viscoelasticity in cortical and trabecular bone. J. Biomech. 2010;43:2410–2417. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Knapp H.F., Reilly G.C., Knothe Tate M.L. Development of preparation methods for and insights obtained from atomic force microscopy of fluid spaces in cortical bone. Scanning. 2002;24:25–33. doi: 10.1002/sca.4950240104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhong Z., Akkus O. Effects of age and shear rate on the rheological properties of human yellow bone marrow. Biorheology. 2011;48:89–97. doi: 10.3233/BIR-2011-0587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jansen L.E., Birch N.P., Peyton S.R. Mechanics of intact bone marrow. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. Mater. 2015;50:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jmbbm.2015.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eom J., Park S., Lee B.H. SPIE; 2017. Noncontact measurement of elasticity using optical fiber-based heterodyne interferometer and laser ultrasonics. In 25th International Conference on Optical Fiber Sensors. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beshtawi I.M., Akhtar R., Radhakrishnan H. Scanning acoustic microscopy for mapping the microelastic properties of human corneal tissue. Curr. Eye Res. 2013;38:437–444. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2012.753094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Butt H.-J., Cappella B., Kappl M. Force measurements with the atomic force microscope: technique, interpretation and applications. Surf. Sci. Rep. 2005;59:1–152. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hutter J.L., Bechhoefer J. Calibration of atomic force microscope tips. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 1993;64:1868–1873. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sneddon I.N. The relation between load and penetration in the axisymmetric boussinesq problem for a punch of arbitrary profile. Int. J. Eng. Sci. 1965;3:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cheng L., Xia X., Gerberich W.W. Spherical-tip indentation of viscoelastic material. Mech. Mater. 2005;37:213–226. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arifin W.N., Zahiruddin W.M. Sample size calculation in animal studies using resource equation approach. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2017;24:101–105. doi: 10.21315/mjms2017.24.5.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang N., Reeves K.J., Eaton C.L. The frequency of osteolytic bone metastasis is determined by conditions of the soil, not the number of seeds; evidence from in vivo models of breast and prostate cancer. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2015;34:124. doi: 10.1186/s13046-015-0240-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ottewell P.D., Wang N., Holen I. Zoledronic acid has differential antitumor activity in the pre- and postmenopausal bone microenvironment in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 2014;20:2922–2932. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Augat P., Schorlemmer S. The role of cortical bone and its microstructure in bone strength. Age Ageing. 2006;35(Suppl 2):ii27–ii31. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Travlos G.S. Normal structure, function, and histology of the bone marrow. Toxicol. Pathol. 2006;34:548–565. doi: 10.1080/01926230600939856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ottewell P.D., Wang N., Holen I. OPG-Fc inhibits ovariectomy-induced growth of disseminated breast cancer cells in bone. Int. J. Cancer. 2015;137:968–977. doi: 10.1002/ijc.29439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guz N., Dokukin M., Sokolov I. If cell mechanics can be described by elastic modulus: study of different models and probes used in indentation experiments. Biophys. J. 2014;107:564–575. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2014.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia P.D., Guerrero C.R., Garcia R. Time-resolved nanomechanics of a single cell under the depolymerization of the cytoskeleton. Nanoscale. 2017;9:12051–12059. doi: 10.1039/c7nr03419a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Evans F.G. Mechanical properties and histology of cortical bone from younger and older men. Anat. Rec. 1976;185:1–11. doi: 10.1002/ar.1091850102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mirzaali M.J., Schwiedrzik J.J., Wolfram U. Mechanical properties of cortical bone and their relationships with age, gender, composition and microindentation properties in the elderly. Bone. 2016;93:196–211. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2015.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Peters A.E., Akhtar R., Bates K.T. The effect of ageing and osteoarthritis on the mechanical properties of cartilage and bone in the human knee joint. Sci. Rep. 2018;8:5931. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-24258-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kopesky P.W., Lee H.Y., Grodzinsky A.J. Adult equine bone marrow stromal cells produce a cartilage-like ECM mechanically superior to animal-matched adult chondrocytes. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:427–438. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Noguchi N., Tabata S., Matsumoto K. Cellular size of bone marrow cells from rats and beagle dogs. J. Toxicol. Sci. 1998;23:189–195. doi: 10.2131/jts.23.3_189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hu Y., Ek-Rylander B., Andersson G. Osteoclast size heterogeneity in rat long bones is associated with differences in adhesive ligand specificity. Exp. Cell Res. 2008;314:638–650. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmitt A., Guichard J., Cramer E.M. Of mice and men: comparison of the ultrastructure of megakaryocytes and platelets. Exp. Hematol. 2001;29:1295–1302. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(01)00733-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Amo C.A., Garcia R. Fundamental high-speed limits in single-molecule, single-cell, and nanoscale force spectroscopies. ACS Nano. 2016;10:7117–7124. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b03262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo D., Li J., Luo J. Elastic properties of polystyrene nanospheres evaluated with atomic force microscopy: size effect and error analysis. Langmuir. 2014;30:7206–7212. doi: 10.1021/la501485e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lai Y.S., Chen W.C., Chang T.K. The effect of graft strength on knee laxity and graft in-situ forces after posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0127293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shahar R., Zaslansky P., Weiner S. Anisotropic Poisson’s ratio and compression modulus of cortical bone determined by speckle interferometry. J. Biomech. 2007;40:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2006.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Monclus M.A., Jennett N.M. In search of validated measurements of the properties of viscoelastic materials by indentation with sharp indenters. Philos. Mag. 2011;91:1308–1328. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Metzger T.A., Niebur G.L. Comparison of solid and fluid constitutive models of bone marrow during trabecular bone compression. J. Biomech. 2016;49:3596–3601. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2016.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao X., Gu W. A new constitutive model for hydration-dependent mechanical properties in biological soft tissues and hydrogels. J. Biomech. 2014;47:3196–3200. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.