DNA methylation and gene expression in carbon reserve mobilization of rice stems occurs during grain filling under moderate soil drying.

Abstract

In rice (Oryza sativa), a specific temporary source organ, the stem, is important for grain filling, and moderate soil drying (MD) enhanced carbon reserve flow from stems to increase grain yield. The dynamics and biological relevance of DNA methylation in carbon reserve remobilization during grain filling are unknown. Here, we generated whole-genome single-base resolution maps of the DNA methylome in the stem. During grain filling under MD, we observed an increase in DNA methylation of total cytosines, with more hypomethylated than hypermethylated regions. Genes responsible for DNA methylation and demethylation were up-regulated, suggesting that DNA methylation changes in the stem were regulated by antagonism between DNA methylation and demethylation activity. In addition, methylation in the CG and CHG contexts was negatively associated with gene expression, while that in the CHH context was positively associated with gene expression. A hypermethylated/up-regulated transcription factor of MYBS2 inhibited MYB30 expression and possibly enhanced β-Amylase5 expression, promoting subsequent starch degradation in rice stems under MD treatment. In addition, a hypermethylated/down-regulated transcription factor of ERF24 was predicted to interact with, and thereby decrease the expression of, abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylase1, thus increasing abscisic acid concentration under MD treatment. Our findings provide insight into the DNA methylation dynamics in carbon reserve remobilization of rice stems, demonstrate that MD increased this remobilization, and suggest a link between DNA methylation and gene expression in rice stems during grain filling.

Cereal crop productivity is highly promoted by source activity, including high photosynthesis or nutrient remobilization rates, and sink strength, including the high capacity for the import of assimilates or the starch and protein biosynthesis rates. Rice (Oryza sativa) production mainly depends on both the current carbohydrate content and the content of redistributed carbohydrates from reserve pools in vegetative tissues either before or after anthesis (Kobata et al., 1992; Scnyhder, 1993). Currently, unused carbon reserves left in stems, caused by unfavorable delays in senescence or the heavy utilization of nitrogen fertilizers, inhibit rice yield potential (Ricciardi and Stelluti, 1995; Yang and Zhang, 2006). In rice, carbon reserves are responsible for grain filling, which typically accounts for approximately one-third of the grain yield and ranges from 0% to 40%, depending on the cultivar and environmental conditions (Ricciardi and Stelluti, 1995; Takai et al., 2005). Moreover, rice is one of the most important crops in the world, with rice production consuming approximately 80% of the total fresh water irrigation resources in Asia (Tuong and Bouman, 2000; Fageria, 2003). Therefore, finding an efficient irrigation practice that not only saves water but also maintains or even increases rice yield is always urgent. The portion of carbohydrates that are considered carbon reserves and are redistributed from reserve pools are known as nonstructural carbohydrates (NSCs). NSCs are mainly composed of soluble sugars and starch (Ishimaru et al., 2004). Previous work has shown that mild soil drying, particularly when imposed during the middle to late stages of grain filling, could improve the transportation of carbon reserves from the stems to grains, accelerate the grain filling rate, and increase grain weight in both rice and wheat (Triticum aestivum; Yang et al., 2001; Yang and Zhang, 2006). The above farming practices not only can save fresh water but also can increase the crop yield. However, no study has assessed the potential involvement of alterations in DNA methylation and its effect on gene expression in response to moderate soil drying (MD) in rice stems during grain filling.

DNA methylation is considered a major and conserved epigenetic mark for maintaining genome integrity, inactive transcription, developmental regulation, and environmental responses (Zhu, 2009; Law and Jacobsen, 2010). It has also been proposed that DNA methylation can modulate the pretranscriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of gene expression in eukaryotic cells (Mirouze and Paszkowski, 2011). A number of recent studies have revealed that DNA methylation is involved in both biotic (Dowen et al., 2012) and abiotic (Sahu et al., 2013) stress responses by modulating gene expression. In addition, using low-resolution, nonquantitative, and locus-specific methods, several studies have shown the potential involvement of alterations in DNA methylation in response to stresses in various plants (Chinnusamy and Zhu, 2009; Mirouze and Paszkowski, 2011; Wang et al., 2011a, 2011b; Karan et al., 2012; Chen and Zhou, 2013; Sahu et al., 2013). For example, in rice, drought stress-induced genome-wide DNA methylation alterations and 70% of the site changes by drought-induced methylation were reversed to their original status after irrigation from the tillering stage until maturity (Wang et al., 2011b). Moreover, induction of the rice OsMYB91 gene in response to salt stress was associated with rapid loss of promoter cytosine methylation, suggesting that dynamic methylation may play a role in regulating the expression of this gene (Zhu et al., 2015). In addition, single-base resolution methylome analysis of drought-stressed poplar (Populus spp.) and apple (Malus domestica) revealed widespread changes in DNA methylation (Liang et al., 2014; Xu et al., 2018).

In plants, DNA methylation has been found in three contexts (CG, CHG, and CHH, where H = A, C, or T), with distinct mechanisms for establishing and maintaining the DNA methylation mark. The maintenance of DNA methylation in the CG and CHG contexts is mediated by METHYLTRANSFERASE1 (MET1) and CHROMOMETHYLASE3 (CMT3) methyltransferases, respectively (Lindroth et al., 2001). Such cases of DNA methylation in the CG and CHG contexts are thus referred to as symmetrical methylation. However, the nonsymmetrical CHH context can be maintained by the activities of the DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLTRANSFERASE1 (DRM1), DRM2, and CMT2 methyltransferases (Finnegan et al., 1996; Zemach et al., 2013; Stroud et al., 2014). DNA methylation levels are dynamically regulated by the antagonism of methylation and demethylation. The process of DNA demethylation is mainly regulated by the enzyme activities of REPRESSOR OF SILENCING1 (ROS1), DEMETER, DEMETER-LIKE2 (DML2), and DML3 (Zhu, 2009). Rice putative orthologs of the above genes have been identified and are presented in Supplemental Table S1. Based on the results of previous studies on the DNA methylation of plant species, the methylation profile is relatively conserved among genomic features, with transposable elements often being highly methylated in all contexts and CG methylation commonly occurring in gene bodies (Feng et al., 2010; Zemach et al., 2013; Mirouze and Vitte, 2014).

Given previous studies assessing the impact of MD on carbon reserve remobilization in the stem, studies of the DNA methylome, and the temporal relationship between DNA methylation and transcriptional changes in plant species, we comprehensively assessed the impact of MD on DNA methylation patterns and transcription in japonica rice. Using whole-genome bisulfite sequencing, we gained insights into the genomic landscape of the rice stem methylome during grain filling, changes in the methylation profiles under MD treatment, and estimated the relationship between the methylome and gene expression changes.

RESULTS

Methylation Landscapes in Rice Stems

Stems under the control (CK) and MD treatments were sampled at 12, 18, and 24 d after anthesis (DAA) during the middle to late grain-filling period. The starch content, soluble sugar level, and NSC contents are shown in Supplemental Figure S1. The starch content in the stems decreased when soil drying was applied during the middle to late grain-filling stages (Supplemental Fig. S1A). MD reduced the starch content dramatically at 18 and 24 DAA (Supplemental Fig. S1A). However, the soluble sugar level showed the opposite pattern: MD increased the soluble sugar level during grain filling (Supplemental Fig. S1B). Obviously, the NSC content was consistent with the starch content (Supplemental Fig. S1C), which was significantly decreased by MD treatment at the late stage of grain filling. The above results suggested that MD improved starch degradation and Suc synthesis, which might enhance carbon reserve remobilization during grain filling.

To investigate the DNA methylation dynamics of stems under MD during grain filling, we generated single-base resolution maps of DNA methylation for rice stems treated with soil drying during the middle to late grain-filling stages. The total average number of clean reads was 5.9 billion, the mapping rate was greater than 88.6%, and the conversion rate was over 98% in all the libraries (Supplemental Data Set S1). Global methylation analysis revealed that the percentage of methylated cytosine sites increased during grain filling under the CK conditions, which were also increased under MD treatment compared with those under the CK conditions, especially at 18 DAA (Fig. 1A). The total methylation level of methyl-cytosine (mC) was enhanced by the MD treatment at 12 and 18 DAA but slightly reduced at 24 DAA both in genic and intergenic regions (Fig. 1B; Supplemental Fig. S2). Higher methylation levels of mCG, mCHG, and mCHH contexts in terms of intron, exon, upstream 2-kb, downstream 2-kb, and intergenic regions were identified in the MD treatment at 12 and 18 DAA (Fig. 1, C–E). By contrast, mCG, mCHG, and mCHH under MD treatment displayed lower methylation levels than those under CK conditions at 24 DAA (Fig. 1, C–E). Obviously, the MD treatment promoted the methylation level of stems in all three contexts at 12 and 18 DAA (Fig. 1, C–E). The mCG sites occupied the largest proportions among the three contexts, followed by CHG and then CHH in rice stems, and the relative percentage of each context was similar to that in previous reports on rice embryos and rice seedlings exposed to cadmium (Fig. 1F; Zemach et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2016). In addition, from the perspective of all chromosomes, the CHH context also presented the lowest methylation level on each chromosome (Supplemental Fig. S3A). In rice stems, among the CG contexts, CGA had the highest enrichment, followed by the CGT and CGG motifs, which suggests that cytosine methylation in the CGA context was much more popular than in all the other relative contexts (Supplemental Fig. S3B). For the context of CHG, the CCG motifs showed the lowest enrichment, and then the enrichment of CAG and CTG increased throughout the genomes (Supplemental Fig. S3C), which is consistent with observations in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), maize (Zea mays), and orange (Citrus sinensis; Gouil and Baulcombe, 2016). In the context of CHH motifs, CAA had the highest enrichment, followed by CTT and CCC throughout the genomes, which was similar to the previously reported results in rice leaves (Supplemental Fig. S3D; Gouil and Baulcombe, 2016).

Figure 1.

Changes in DNA methylation levels in stems during grain filling under the CK and MD treatments. A, Percentage of methylated cytosines from 12 to 24 DAA under the CK and MD treatments. B, mC methylation levels from 12 to 24 DAA under the CK and MD treatments. C to E, Methylation levels of mCG, mCHG, and mCHH, respectively, from 12 to 24 DAA in different genomic regions under the CK and MD treatments. F, Relative proportions of mCG, mCHG, and mCHH in total mCs.

DNA Methylation Patterns in Different Genomic Regions of Rice Stems

The DNA methylation status varies among different genomic regions. In this study, the genomic regions were characterized into seven subregions, including the upstream 2-kb region, 5′ untranslated region (UTR), exon region, intron region, 3′ UTR, downstream 2-kb region, and repeat region. First, we analyzed the methylation status of stems under CK conditions during grain filling. As shown in Figure 2A and Supplemental Figure S4, the CG context presented the highest methylation level and CHH presented the lowest methylation level among the three contexts in different gene regions. The methylation level of the CG context was highest among all three contexts in exon and intron regions. Moreover, the intron regions demonstrated higher methylation level compared with the exon regions in the CG context. The methylation level in the CHG context displayed similar patterns to the CHH context. In these two contexts, the level of methylation was highest in the upstream 2-kb region and lowest in the exon region (Supplemental Fig. S4). Substantially, the methylation level of repeat regions was highest among all the regions in the CG, CHG, and CHH contexts (Fig. 2A). Regarding the effect of MD treatment on the methylation level, we found that MD influenced the methylation level of upstream 2-kb, downstream 2-kb, and repeat regions, especially in the CHH context (Fig. 2B). In addition, the MD treatment dramatically reduced the methylation level of repeat regions in the CHH context (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

DNA methylation patterns in different genomic regions. A, Methylation level of upstream 2-kb (upstream2k), downstream 2-kb (downstream2k), repeat, and coding genes with 5′ UTR, exon, intron, and 3′ UTR regions in the CG, CHG, and CHH contexts at 12 DAA under the CK condition. The white dots represent the median methylation level, and the black rectangles are the range from the lower quartile to the upper quartile. The length of each shape represents the degree of dispersion and symmetry of nonabnormal data. Longer is scattered, and shorter is concentrated. B, Percentage of methylation levels altered by MD treatment among gene features in each sample.

An Antagonism between DNA Demethylase and Methyltransferase Is Associated with the Increased DNA Methylation after MD Treatment

DNA methyltransferase and DNA demethylase activities play crucial roles in maintaining the DNA methylation status during plant development. Methylation levels could be induced by altered expression levels of DNA methyltransferase genes or DNA demethylase genes. Thus, we examined the expression levels of methylation-related genes under both CK and MD treatments during grain filling. The expression levels of DNA methyltransferase genes, including OsMET1, OsCMTs, and OsDRMs, are presented in Figure 3. Based on the transcriptomic profiles, genes encoding OsCMT1, OsCMT3, and OsDRM1 were undetectable in stems during grain filling, suggesting that these genes might not be responsible for DNA methylation in rice stems. MD treatment slightly reduced the expression level of OsMET1-2 and increased the expression levels of OsCMT2 and OsDNMT2 without significance (Fig. 3, A–C). Instead, the most highly expressed methyltransferase genes in stems, OsDRM2 and OsDRM3, were significantly promoted by MD treatment at 18 DAA (Fig. 3, D and E). Thus, the MD treatment may increase the DNA methylation level at 18 DAA by changing the expression of DNA methyltransferase genes. OsROS genes, including OsROS1a, OsROS1b, OsROS1c, and OsROS1d, were responsible for DNA demethylase. The OsROS1b gene was barely detected in stems during grain filling. The MD treatment increased the expression of OsROS1a, OsROS1c, and OsROS1d genes, especially OsROS1d, which showed a substantial change at 18 DAA (Fig. 3, F–H). Thus, antagonism between DNA demethylation and DNA methylation might play a role in dynamically regulating the stem methylome in response to MD treatment.

Figure 3.

Expression of DNA methyltransferase and DNA demethylase genes in stems during grain filling. Fragments per kilobase million (FPKM) values are shown for OsMET1-2 (A), OsCMT2 (B), OsDNMT2 (C), OsDRM2 (D), OsDRM3 (E), OsROS1a (F), OsROS1c (G), and OsROS1d (H). Values represent means ± sd of three biological replicates. Asterisks indicate that the values of the two treatments were significantly different at P < 0.05 determined by Student’s t test.

Association between DNA Methylation Status and Gene Expression Levels

To investigate whether the changes in the methylation levels imposed by MD treatment were associated with gene expression during grain filling, we generated the transcriptome profiles for the stems at each stage under both the CK and MD treatments. Genes were first divided into nonexpressed genes, lowest expression level, a medium expression level, and the highest expression level. Since each sample showed a similar relationship between methylation and expression level, a sample of N_CK-12 was used as an example to explain this relationship in rice stems during grain filling (Fig. 4A). As expected, the genes with the highest expression showed relatively low methylation levels in the CHG sequence throughout most of the gene regions (Fig. 4A). However, the methylation status of either CG or CHH was complicated. Nonexpressed genes presented high CG methylation levels in the upstream 2-kb and downstream 2-kb regions, especially at the transcription start and end sites. By contrast, high CG methylation levels throughout much of the gene body were associated with high expression (Fig. 4A). Unlike those for CG and CHG contexts, the levels of CHH methylation in the promoter region were positively associated with gene expression levels. Methylation levels within gene bodies were negatively correlated with gene expression, whereas less difference was observed in the downstream 2-kb region and the transcription start and end sites (Fig. 4A). The positive correlation between CHH methylation flanking genes and gene expression level was consistent with the results of previous studies (Gent et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2018).

Figure 4.

Relationship between DNA methylation and gene expression. A, Distribution of methylation levels within gene bodies based on four different expression levels: nonexpressed (non), high (hig), medium (med), and low. B, Expression profiles of methylated genes compared with unmethylated genes. Methylated genes were further divided into four quantiles based on the upstream 2-kb (up2k), gene body, and downstream 2-kb (down2k) regions.

To further assess the relationship between gene methylation and gene expression, genes were classified into four groups based on their methylation level in terms of CG and CHG contexts, including 0.25 for genes with the lowest methylation level and the fourth group with the highest methylation level ranging from 0.75 to 1, while for the CHH context, genes were only classified into two groups because of the relatively low methylation level (Fig. 4B). For the CG context, genes with the highest methylation level in the upstream 2-kb region showed relatively low expression levels, and no distinct differences were identified in the other three methylation level groups. However, the highest and lowest methylation levels in the gene body region showed relatively low and high expression levels, respectively, while the other two methylation quartiles showed much higher expression levels. The methylation level in the downstream 2-kb region was negatively associated with the gene expression level (Fig. 4B). For the CHG context, the methylation levels were negatively associated with gene expression in the upstream 2-kb, gene body, and downstream 2-kb regions (Fig. 4B). Notably, the methylation level in the upstream 2-kb region was positively associated with gene expression level, opposite to that relationship in the gene body region in the CHH context, consistent with the results in Figure 4A. In addition, no distinct differences were identified in the downstream 2-kb region for the two groups in the CHH context (Fig. 4B).

More Hypomethylated DMRs Than Hypermethylated DMRs Were Identified under MD Treatment

In our analysis, DMRs were identified between the CK and MD treatments during grain filling. Many more CHH-DMRs were identified than CG-DMRs, and many fewer CHG-DMRs were detected in the stems of rice under MD treatment at three grain-filling stages (Fig. 5A). Apparently, most of the DMRs were contributed by the CHH context. It is clear that the number of hypomethylated DMRs was higher than that of hypermethylated DMRs during grain filling, especially at 24 DAA (Fig. 5B). Then, we investigated the DMR status in different genomic regions and found that the total DMR number and DMR number in each of the three methylation contexts gradually increased from 12 to 24 DAA (Fig. 5, C–F), suggesting that MD treatment promoted changes in DNA methylation during grain filling. The largest number of CG DMRs was identified in the upstream regions, followed by the promoter regions, downstream regions, exon regions, repeat regions, and UTRs (Fig. 5D). By contrast, the largest numbers of CHG DMRs and CHH DMRs were identified in repeat regions, followed by the upstream regions, promoter regions, and downstream regions (Fig. 5, E and F). Moreover, the number of DMRs detected in the exon region was higher than that in the intron region in both the CG and CHG contexts, which was opposite to the findings in the CHH context (Fig. 5, D–F).

Figure 5.

Differential methylome analysis under MD treatment. A, Number of DMRs in the CG, CHG, and CHH contexts in three comparisons. B, Number of total hypomethylated and hypermethylated DMRs in three comparisons. C, Total DMRs in different gene features at three grain-filling stages. D, Number of DMRs in different gene features in the CG context. E, Number of DMRs in different gene features in the CHG context. F, Number of DMRs in different gene features in the CHH context.

In addition, we also normalized DMR number in the number of DMRs per Mb sequences on each chromosome between CK and MD conditions (Fig. 6). At 12 DAA, the number of hypomethylated DMRs per Mb on each chromosome was larger than the hypermethylated DMRs per Mb in all three contexts (Fig. 6A). However, at 18 DAA, the number of hypomethylated DMRs per Mb was less than that of hypermethylated DMRs in most of the chromosomes in the CG context; we identified a larger number of hypomethylated DMRs per Mb than hypermethylated DMRs on most of the chromosomes in the CHG context; and the number of hypomethylated DMRs per Mb was larger than that of hypermethylated DMRs in the CHH context (Fig. 6B). We identified that at 24 DAA, the numbers of hypomethylated DMRs and hypermethylated DMRs per Mb were similar in the CG context, whereas the number of hypomethylated DMRs per Mb was larger than hypermethylated DMRs in both the CHG and CHH contexts (Fig. 6C).

Figure 6.

Normalized value of DMR number in the number of DMRs per Mb in each chromosome. A, DMR number per Mb between the CK and MD conditions at 12 DAA in CG, CHG, and CHH contexts. B, DMR number per Mb between the CK and MD conditions at 18 DAA in CG, CHG, and CHH contexts. C, DMR number per Mb between the CK and MD conditions at 24 DAA in CG, CHG, and CHH contexts.

Analysis of Genes Associated with DNA Methylation

To investigate how MD treatment enhances carbon reserve remobilization in stems at the methylation level, we analyzed differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the CK and MD treatments at 12, 18, and 24 DAA during grain filling (Supplemental Table S2). The numbers of up-regulated DEGs and down regulated DEGs were substantially larger at 18 DAA among all three comparisons (Fig. 7A). The above transcriptomic profiles suggest that the global expression patterns were substantially altered by the MD treatment at 18 DAA during grain filling, which was consistent with the largest difference in mC methylation level between the CK and MD conditions at 18 DAA (Fig. 1B). Based on the results of the global methylation level and transcriptional expression pattern, in this study, we mainly analyzed the methylation status of stems at 18 DAA, which was more obviously altered by the MD treatment than the two other grain-filling stages.

Figure 7.

Association between gene expression and methylation during grain filling under soil-drying conditions. A, Number of DEGs during grain filling among the three comparisons. B, Venn diagram showing the number of DMRs that occurred in promoter regions proximal to DEGs in the CG context at 18 DAA. C, Venn diagram showing the number of DMRs that occurred in promoter regions proximal to DEGs in the CHG context at 18 DAA. D, Venn diagram showing the number of DMRs that occurred in the promoter regions proximal to DEGs in the CHH context at 18 DAA. E, Down-regulated gene of OsSAUR2 (N_CK_18 versus N_MD-18), which is proximal to a hypomethylated DMR in the upstream region of this gene in the IGV. F, Up-regulated gene of SWEET6b (N_CK_18 versus N_MD-18), which is proximal to a hypermethylated DMR in the upstream region of this gene in the IGV. In E and F, blue represents the methylation levels and red represents the gene expression levels.

Since DNA methylation occurring in the promoter region is associated with the repression of gene transcription, we identified DMRs in the promoter region proximal to DEGs in terms of mCG DMRs and mCHG DMRs. We focused on the hypermethylated DMRs, which associated with down-regulated DEGs, and hypomethylated DMRs, which associated with up-regulated DEGs, in CG and CHG contexts (Fig. 7, B and C). There were 42 hypermethylated mCG DMRs in promoters proximal to down-regulated DEGs, while 80 hypomethylated mCG DMRs in promoters were associated with up-regulated DEGs (Fig. 7B). The above mCG DMRs in promoters associated with DEGs were enriched in various Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathways, including Metabolic pathways, DNA replication, and Cysteine and methionine metabolism (Supplemental Fig. S5A). The pathways of Spliceosome and Plant hormone signal transduction were also enriched in the methylated promoters in response to MD treatment, although they were not significant. The Os02g0240300 gene, which was stress responsive, was hypomethylated and up-regulated, suggesting that demethylation activated its expression in response to the MD treatment. One gene encoding Splicing Factor8 (Os05g0163250) was hypomethylated and up-regulated in response to MD, suggesting that the alternative splicing process might play a role in carbon reserve remobilization of rice stems. Interestingly, the gene encoding Leaf Senescence Protein-Like (Os06g0234300) displayed demethylation and increased expression levels, suggesting that DNA demethylation controls rice senescence under MD treatment. Additionally, Potassium Transporter3 (Os01g0369300) was also hypomethylated and up-regulated. In terms of mCHG DMRs, 32 hypomethylated mCHG DMRs in promoters were associated with up-regulated DEGs and 14 down-regulated DEGs were proximal to hypermethylated mCHG DMRs (Fig. 7C). Some of these mCHG DMRs were associated with DEGs encoding Protein Ubiquitination (Os03g0398600), Defense Protein (Os01g0382400), F-Box Domain Containing Protein (Os03g0855500), etc. Importantly, β-Glucosidase24 (Os06g0320200) was hypomethylated and up-regulated, suggesting that demethylation activated the expression of genes related to starch degradation in response to the MD treatment.

By contrast, CHH methylation levels in the promoter region were positively associated with gene expression levels. There were 183 hypomethylated mCHH DMRs in the promoters proximal to down-regulated DEGs, while 178 hypermethylated mCHH DMRs were associated with up-regulated DEGs (Fig. 7D). In Gene Ontology analysis of mCHH DMRs, hypomethylated DMRs associated with down-regulated DEGs were significantly enriched in the cellular component category, followed by the categories of molecular function and biological process (Supplemental Fig. S5B). Among the above mCHH hypomethylated DMRs associated with down-regulated DEGs, for example, a gene encoding auxin-responsive SAUR protein, OsSAUR2 (Os01g0768333), was hypomethylated and down-regulated, as presented in the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; Fig. 7E). On the other hand, hypermethylated mCHH DMRs associated with up-regulated DEGs were only significantly enriched in the cellular component category (Supplemental Fig. S5C). It is notable that the gene encoding Sugars Will Eventually Be Exported Transporter6b (SWEET6b; Os01g0605700), a member of the sugar transporters, was significantly methylated with elevated transcript levels under MD treatment (Fig. 7F).

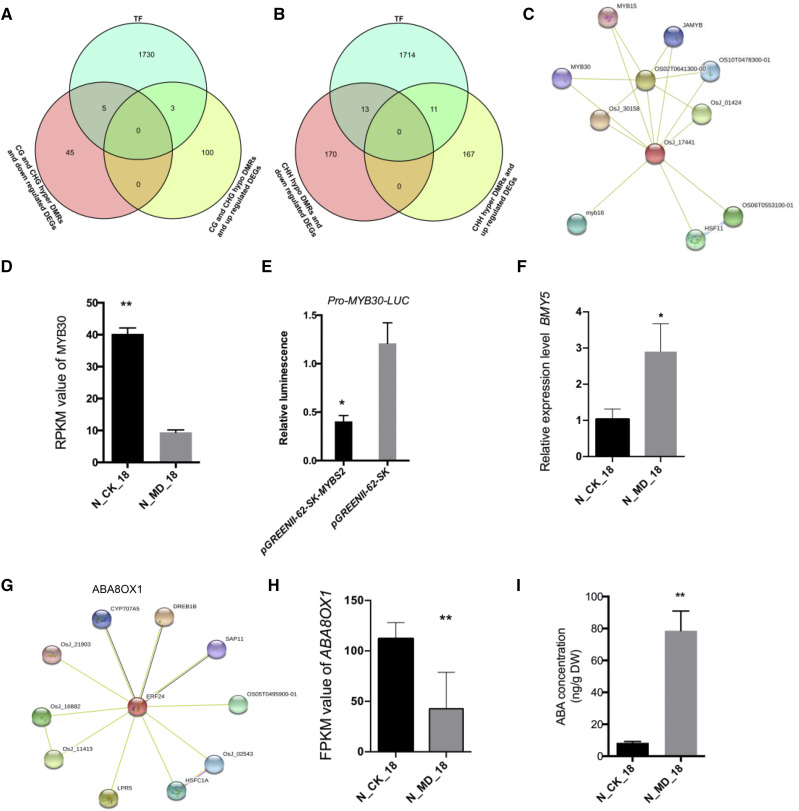

Changes in the Methylation and Expression Profiles of Transcription Factors under MD Are Related to Carbon Reserve Remobilization in Stems

MD treatment applied at the grain-filling stage led to differential methylation levels and expression levels of transcription factors (TFs) belonging to multiple TF families. The TFs overlapping with two gene clusters, which were associated with DMRs that occurred in promoter regions, were plotted in Venn diagrams (Fig. 8, A and B). In total, eight differentially expressed TFs associated with mCG DMRs and mCHG DMRs in promoter regions (cluster 1; Fig. 8A) and 24 differentially expressed TFs associated with mCHH DMRs in promoter regions (cluster 2; Fig. 8B) were identified at 18 DAA between the CK and MD treatments. In cluster 1, the TFs were classified into the families of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH), basic leucine zipper (bZIP), ethylene-responsive element-binding factor (ERF), MYB, etc. (Supplemental Table S3). Notably, most of the TFs function in stress responses, such as drought and heat. The TFs in cluster 2 belonged to various TF families, such as WRKY, bHLH, bZIP, NAC, and ERF (Supplemental Table S3). One of the MYBS2-like TFs (Os05g0195700), hypermethylated in promoter regions with enhanced transcript levels (Supplemental Fig. S6A), was predicted to interact with MYB30 (Os02g0624300), which was significantly down-regulated under MD treatment (Fig. 8, C and D). Luciferase assays indicated that MYBS2-like inhibited MYB30 at the transcriptional level (Fig. 8E). In addition, MYB30 has been demonstrated to negatively regulate β-amylase genes (Os07g0543300 [BMY2], Os10g0565200 [BMY6], and Os02g0129600 [BMY10]) at the transcription level in response to cold stress (Lv et al., 2017). The MD treatment induced the expression of BMY5 (Os10g0465700) in stems, which was consistent with the expression of MYB30 (Fig. 8F). Notably, ERF24, an mCHH hypermethylated and down-regulated TF, encoded by Os09g0522200 (Supplemental Fig. S6B), was predicted to be coexpressed with the abscisic acid (ABA) catabolism gene, ABA8OX1, which was down-regulated by 77% under the MD treatment compared with the CK conditions (Fig. 8, G and H). Furthermore, stem ABA concentration was significantly increased by the MD treatment, consistent with the ABA8OX1 expression level (Fig. 8I).

Figure 8.

Associated TFs between DNA methylation in the promoter region and gene expression during grain filling at 18 DAA. A, Venn diagram showing the TFs of hypomethylated DMRs in promoter regions proximal to up-regulated genes and hypermethylated DMRs in promoter regions and down-regulated genes in CG and CHG contexts. B, Venn diagram showing the TFs of hypomethylated DMRs in promoter regions proximal to down-regulated genes and hypermethylated DMRs in promoter regions and up-regulated genes in CHH contexts. C, Interacting proteins of MYBS2 predicted using Interactions Viewer (https://string-db.org/cgi/input.pl). D, Reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads (RPKM) values of MYB30 at 18 DAA under the CK and MD treatments. Values represent means ± sd of three biological replicates. **, P < 0.01 determined by Student’s t test. E, Coexpression of MYBS2 with LUC driven by the MYB30 promoter in leaf protoplasts. Values represent means ± sd of two biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 determined by Student’s t test. F, Relative expression levels of BMY5 under MD conditions at 18 DAA. Values represent means ± sd of three biological replicates. *, P < 0.05 determined by Student’s t test. G, Interacting proteins of ERF24 predicted using Interactions Viewer. H, Gene expression levels of ABA8OX1 during grain filling under MD conditions. Values represent means ± sd of three biological replicates. **, P < 0.01 determined by Student’s t test. I, ABA concentration measured at 18 DAA under MD conditions. Values represent means ± sd of three biological replicates. **, P < 0.01 determined by Student’s t test. DW, Dry weight.

DISCUSSION

DNA methylation is a marker of plant stress responses, which regulate gene expression during development and in response to different kinds of stress. In this study, moderate soil drying during grain filling of rice enhanced the remobilization of pre-stored carbon reserve in the stems to the grains (Supplemental Fig. S1, A and B), consistent with previous reports (Yang et al., 2001; Yang and Zhang, 2006). This remobilization increased NSC translocation from stems to grains, especially to the inferior grains (Yang and Zhang, 2006; Zhang et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2019). However, although MD at grain filling enhanced prestored carbon reserve remobilization and increased the grain yield (Yang et al., 2001; Yang and Zhang, 2006; Wang et al., 2019), very little is known about the potential role of epigenetic regulation in response to moderate drying-induced improvement of carbon reserve remobilization in stems. Comprehensive methylome profiling coupled with the transcriptome profiling might reveal the potential role of epigenome changes and the relationship between changes in DNA methylation and gene expression during grain filling under MD treatment. In this study, single-base resolution maps of DNA methylation of rice stems under CK and MD conditions at three grain-filling stages were generated. More hypomethylated DMRs than hypermethylated DMRs were identified (Fig. 5B), which was quite strange based on the increased methylation level in both genic and intergenic regions at 12 and 18 DAA. This result was similar to the cadmium stress response of rice, in which more hypermethylated DMRs than hypomethylated DMRs were found on the basis of dramatically reduced methylation levels on each chromosome in the CG and CHG contexts (Feng et al., 2016). DNA methylation is dynamically regulated by an antagonism between DNA demethylation and DNA methylation (Lang et al., 2017; Cheng et al., 2018).We also found that several genes encoding both DNA methyltransferases and demethylases, especially OsDRM2, OsDRM3, and OsROS1d, were up-regulated by MD treatment (Fig. 3). Therefore, we hypothesize that the antagonism of increased DNA methylation activity and demethylation activity could contribute to the DNA hypomethylation in certain genomic regions and to the DNA hypermethylation at the whole-genome level during grain filling under MD conditions.

DNA methylation is believed to repress gene expression and maintain genome stability (Chan et al., 2005). However, recent studies have demonstrated that methylation in different genomic regions has different effects on controlling gene expression. For example, promoter methylation represses gene expression only in heavily methylated gene loci and gene body methylation is usually positively associated with gene expression in rice (Li et al., 2012). In addition, no apparent association between promoter methylation and gene expression occurred in apple (Xu et al., 2018). In our results, methylation in the CG and CHG contexts was usually negatively associated with gene expression, while methylation in the CHH context was positively associated with gene expression in the promoter regions (Fig. 4A). It was also demonstrated that gene expression at the transcript level was not always positively or negatively associated with methylation, which is consistent with previous observations that alterations in methylation status may not always influence gene expression (Zemach et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2018). Although DNA methylation occurring in the promoter region is associated with the repression of gene transcription, the function of DNA methylation beyond the promoter regions is complicated and not so well understood (Henderson and Jacobsen, 2007; Hernando-Herraez et al., 2015). In this study, we identified the genes with DMRs in the promoter proximal to the DEGs (Fig. 7, B–D), suggesting that the changed methylation level might lead to differential gene expression in response to MD treatment, consistent with previous stress-induced DNA methylation differences in plants (Chinnusamy and Zhu, 2009; Mirouze and Paszkowski, 2011; Wang et al., 2011a, 2011b; Karan et al., 2012; Chen and Zhou, 2013; Sahu et al., 2013). SWEET Suc transporters, including SWEET4, SWEET9, SWEET11, and SWEET15, are essential in sugar transportation in rice spikelet grain filling, through playing roles in phloem loading (Lin et al., 2014; Ma et al., 2017; Yang et al., 2018). In this study, SWEET6b was hypermethylated and up-regulated under MD treatment, indicating its essential role in sugar transportation during carbon reserve remobilization in rice stems, not only in the spikelets (Fig. 7F).

TFs are essential regulators that play crucial roles in plant growth and development and in response to a range of abiotic stresses (Sperotto et al., 2009; Shamimuzzaman and Vodkin, 2013). The TF families of AP2 and NAC participate in regulating the grain-filling process in spikelets (Uauy et al., 2006; Oh et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2019). Methylation changes in TFs may control their expression, which can further affect the expression levels of their downstream targets. In our study, the differentially expressed TFs associated with methylation were mostly stress-induced genes, including the WRKY, ERF, bZIP, and bHLH families. Notably, the MYBS2-like TF encoded by Os05g0195700 inhibited the expression level of MYB30 (Fig. 8, D and E) and might have subsequently regulated the expression of BMY5 (Fig. 8F). Therefore, the regulatory module of MYBS2-like, MYB30, and BMY5 might be involved in the starch degradation process, which could improve carbon reserve remobilization in stems. The down-regulated and hypermethylated TF of ERF24 encoded by Os09g0522200 was predicted to be coexpressed with down-regulated ABA8OX1 (Fig. 8, G and H; Supplemental Fig. S6B). However, mCHH methylation in ERF24 displayed a negative association with transcript level that was opposite to the results in Figure 4. This change increased stem ABA concentration in the MD treatment (Fig. 8I) and thus increased starch degradation and sugar transport in stems (Chen and Wang, 2012).

CONCLUSION

Herein, we investigated the dynamics and biological relevance of DNA methylation during the carbon reserve remobilization in rice stems at grain filling by using whole-genome single-base resolution maps of the DNA methylome. There was an increase in DNA methylation in total cytosines, while more hypomethylated DMRs than hypermethylated DMRs were found during grain filling under MD, which needs to be further investigated. The dynamic changes in DNA methylation were regulated by the antagonism of DNA methylation and demethylation activity. Additionally, methylation in the CG and CHG contexts was usually negatively associated with gene expression, while methylation in the CHH context was positively associated with gene expression. Our findings provide insight into the DNA methylation dynamics in rice stems during the carbon reserve remobilization under MD treatment and address the importance of DMRs associated with DEGs in rice stems during grain filling.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Experiments were conducted at the genetic garden of the Chinese University of Hong Kong during the rice (Oryza sativa) growing season (from March to August 2016). The japonica inbred cv Nipponbare was grown in rice growth pools (width, 1.5 m; length, 5 m) under a plastic shelter located in the field. The water content of the soil was controlled with a tensiometer. Seedlings were transplanted into the soil at a hill spacing of 0.2 m × 0.2 m with one seedling per hill. The water level in the pool was maintained at 1 to 2 cm above the soil surface until 9 DAA, when the MD treatment was initiated. Fertilizer was applied to the soil before transplanting as follows: N (60 kg ha−1 as urea), P (30 kg ha−1 as single superphosphate), and K (40 kg ha−1 as KCl). N as urea was also applied at the midtillering stage (40 kg ha−1) and panicle initiation stage (25 kg ha−1). Fifty percent of plants headed on June 18 to 20 and were harvested on August 10.

Water Stress Treatments

Plant pools were well irrigated until 9 DAA. Then, two different soil water potential levels were applied by controlling the application of water. CK plants were grown in the pools at a water depth of 1 to 2 cm (soil water potential equal to 0 kPa), which was maintained by manually applying tap water, while the plants subjected to the MD treatment were maintained with a soil water potential of –25 ± 5 kPa. Each treatment was performed with three pools as replicates. The soil water potential in the pools used for the MD treatment was monitored at a soil depth of 15 to 20 cm using a tensiometer consisting of a 5-cm-long sensor (Institute of Soil Science, Chinese Academy of Sciences); four tensiometers were installed in each pool to maintain an even distribution, and readings were recorded twice daily at 10 am and 4 pm. When the readings dropped to a designated value, 40 L of tap water per pool was added manually. The pools were sheltered from rain by covering with a polyethylene shelter.

Sampling

Two hundred stems that were headed on the same day were chosen and tagged. Thirty tagged stems (only the sheath of the flag leaf and the stem inside it) from each cultivar were sampled at 12, 18, and 24 DAA. The sampled stems were divided into two groups (15 plants each) of subsamples. Fifteen tagged stems (five stems formed a subsample) from each stage were sampled for determination of their NSC contents. The remaining sampled stems (three stems formed a subsample) at each stage were immediately chopped, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for total RNA and DNA extraction.

Assays of NSC, Soluble Carbohydrate, and Starch Contents

Stems (sheaths and stems) were immediately dried in a forced-air dryer at 80°C to constant weight for NSC measurements. The dry stems were ground into powder. The NSC measurement was performed as previously described (Yang et al., 2001). The samples used for measuring the starch and Suc contents were ground into a fine powder. In a 15-mL centrifuge tube, 500 mg of the ground sample was added to 10 mL of 80% (v/v) ethanol and kept in a water bath at 80°C for 30 min. After cooling in water, the tube was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was collected, and the extraction was repeated three times. Then, the sugar extract was diluted to 50 mL with distilled water. The Suc content was measured as described in a previous study (Wang et al., 2020). The residue remaining in the centrifuge tube after sugar extraction was dried at 80°C for starch extraction using the HClO4 reagent following the method described by Yang et al. (2001).

Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing and Data Analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from stems using a DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen), and equal amounts of DNA from three replicates were well mixed for subsequent bisulfite sequencing. The whole-genome bisulfite sequencing libraries were prepared using an NEBNext Ultra II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina (New England Biolabs) and an EpiTect Plus DNA Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) with 1 μg of genomic DNA sonicated into 200- to 400-bp fragments on a Covaris M220. The fragmented DNA was subjected to end repair and adenylation. Then, the DNA fragments were treated twice with bisulfite using an EZ DNA Methylation Gold Kit (Zymo Research). After bisulfite treatment, the unmethylated C site was converted into U, and the methylated C site remained the same. Then, all the fragments were amplified by PCR to obtain the final whole-genome bisulfite sequencing library. The library was then subjected to paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq4000 PE101 platform. BSMAP (version 2.73) was used to perform alignments of bisulfite-treated reads to the reference genome (https://rapdb.dna.affrc.go.jp/download/irgsp1.html) using default parameters. DMRs were identified by Metilene v0.2-7 (Jühling et al., 2016), with a threshold of differences of more than 10 cytosines and methylation differences larger than 0.1 in CHH, five cytosines and methylation differences larger than 0.3 in CG, and five cytosines and methylation differences larger than 0.2 in CHG. The cutoff of methylation analysis was P < 0.01 using a double statistical test (MWU_test and 2D KS_test) to detect significant DMRs. The genomic regions were classified as upstream 2-kb, promoter (upstream 1,500 bp of the transcription start site and downstream 500 bp of the transcription start site), exon, intron, 5′ UTR, 3′ UTR, downstream 2 kb, and repeat regions.

RNA Extraction and Library Construction

Total RNA from stems sampled at 12, 18, and 24 DAA under the CK and MD treatments was extracted using an RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) following a previously described method with three biological replicates (Wang et al., 2019). Then, libraries were constructed according to the previously described method (Wang et al., 2019). The library was then subjected to paired-end sequencing on an Illumina HiSeq4000 PE101 platform. The data analysis was performed according to previously described methods (Wang et al., 2019).

Determination of Endogenous ABA Concentration

Plant materials (50 mg fresh weight) were frozen in liquid nitrogen, ground into powder, and extracted with methanol:water:formic acid (15:4:1, v/v/v). The combined extracts were evaporated to dryness under a nitrogen gas stream, reconstituted in 80% (v/v) methanol, and filtered (polytetrafluoroethylene, 0.22 μm; Anpel). The sample extracts were analyzed using a liquid chromatography-electrospray ionization-tandem mass spectrometry system (HPLC, Shim-pack UFLC Shimadzu CBM30A system; mass spectrometry, Applied Biosystems 6500 Triple), and the data were analyzed by Metware Biotechnology. Three replicates of each assay were performed.

Analysis of Luciferase in Vivo

The 2,600-bp sequence of the native MYB30 promoter (Pro-MYB30) was amplified from japonica rice genomic DNA using the primers MYB30-F (5′-CTATAGGGCGAATTGGGTACCCGACACGTTACTTTGACCGAC-3′) and MYB30-R (5′-CGCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCCGACCTTTCCTCCTCTCGTT-3′), with restriction sites KpnI and BamHI, respectively. The amplified promoters were cloned into the pGREENII-0080-luc vector by a one-step cloning kit (Vazyme) to form the reporter construct. Then, the coding sequence region of MYBS2 was amplified using the primers of MYBS2-F (5′-CGCTCTAGAACTAGTGGATCCATGGCTAGGAAGTGCTCT-3′) and MYBS2-R (5′-TCAGCGTACCGAATTGGTACCTCAGGTAACTCTGATGGTC-3′), with restriction sites BamHI and KpnI, respectively. And it was cloned into the pGREENII-62-SK vector by a one-step cloning kit (Vazyme) to form the effector construct. Then, the two constructed vectors were mixed well for the transient expression assay in the protoplast. This transient expression assay was performed as described previously (Wang et al., 2019).

Data Analysis

Statistical analysis of the data was performed in GraphPad Prism 6 software using Student’s t test.

Accession Numbers

Sequence data from this article can be found in the GenBank/EMBL data libraries under accession numbers PRJNA565146 and PRJNA615291.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. MD applied postanthesis alters the NSC, soluble sugar, and starch concentrations of stem during grain filling.

Supplemental Figure S2. The mC methylation levels in different genome contexts during grain filling.

Supplemental Figure S3. The genome of the rice stem.

Supplemental Figure S4. Distributions of DNA methylation levels among gene features, including the upstream 2-kb, exon, intron, and downstream 2-kb regions, at 12 DAA under CK conditions.

Supplemental Figure S5. Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes pathway and Gene Ontology analyses of DMRs in promoter regions associated with DEGs.

Supplemental Figure S6. Examples of methylated DMRs associated with DEGs in the IGV.

Supplemental Table S1. DNA methyltransferase genes and DNA demethylase genes in rice.

Supplemental Table S2. Summary of RNA sequencing libraries.

Supplemental Table S3. DMRs occurring in promoters associated with differentially expressed TFs.

Supplemental Data Set S1. Summary of DNA methylation libraries.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2017YFD0301502), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. NSFC31771701), the Key Research and Development Program of Hunan Province (grant no. 2018NK1010), the Hunan Agricultural University Excellent Talent Fund of Crop Science (grant no. ZD2018–2), the Double First-Class Construction Project of Hunan Agricultural University (grant no. SYL201802013), and the Hong Kong Research Grant Council (grant nos. AoE/M–05/12, AoE/M–403/16, GRF14122415, 14160516, and 14177617).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Chan SWL, Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE(2005) Gardening the genome: DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nat Rev Genet 6: 351–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HJ, Wang SJ(2012) Abscisic acid enhances starch degradation and sugar transport in rice upper leaf sheaths at the post-heading stage. Acta Physiol Plant 34: 1493–1500 [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Zhou DX(2013) Rice epigenomics and epigenetics: Challenges and opportunities. Curr Opin Plant Biol 16: 164–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J, Niu Q, Zhang B, Chen K, Yang R, Zhu JK, Zhang Y, Lang Z(2018) Downregulation of RdDM during strawberry fruit ripening. Genome Biol 19: 212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnusamy V, Zhu JK(2009) Epigenetic regulation of stress responses in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 12: 133–139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowen RH, Pelizzola M, Schmitz RJ, Lister R, Dowen JM, Nery JR, Dixon JE, Ecker JR(2012) Widespread dynamic DNA methylation in response to biotic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: E2183–E2191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fageria NK.(2003) Plant tissue test for determination of optimum concentration and uptake of nitrogen at different growth stages in lowland rice. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 34: 259–270 [Google Scholar]

- Feng S, Cokus SJ, Zhang X, Chen PY, Bostick M, Goll MG, Hetzel J, Jain J, Strauss SH, Halpern ME, et al. (2010) Conservation and divergence of methylation patterning in plants and animals. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 8689–8694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng SJ, Liu XS, Tao H, Tan SK, Chu SS, Oono Y, Zhang XD, Chen J, Yang ZM(2016) Variation of DNA methylation patterns associated with gene expression in rice (Oryza sativa) exposed to cadmium. Plant Cell Environ 39: 2629–2649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnegan EJ, Peacock WJ, Dennis ES(1996) Reduced DNA methylation in Arabidopsis thaliana results in abnormal plant development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 8449–8454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gent JI, Ellis NA, Guo L, Harkess AE, Yao Y, Zhang X, Dawe RK(2013) CHH islands: De novo DNA methylation in near-gene chromatin regulation in maize. Genome Res 23: 628–637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouil Q, Baulcombe DC(2016) DNA methylation signatures of the plant chromomethyltransferases. PLoS Genet 12: e1006526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson IR, Jacobsen SE(2007) Epigenetic inheritance in plants. Nature 447: 418–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernando-Herraez I, Garcia-Perez R, Sharp AJ, Marques-Bonet T(2015) DNA methylation: Insights into human evolution. PLoS Genet 11: e1005661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru K, Kosone M, Sasaki H, Kashiwagi T(2004) Leaf contents differ depending on the position in a rice leaf sheath during sink-source transition. Plant Physiol Biochem 42: 855–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jühling F, Kretzmer H, Bernhart SH, Otto C, Stadler PF, Hoffmann S(2016) Metilene: Fast and sensitive calling of differentially methylated regions from bisulfite sequencing data. Genome Res 26: 256–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karan R, DeLeon T, Biradar H, Subudhi PK(2012) Salt stress induced variation in DNA methylation pattern and its influence on gene expression in contrasting rice genotypes. PLoS ONE 7: e40203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobata T, Palta JA, Turner NC(1992) Rate of development of postanthesis water deficits and grain filling of spring wheat. Crop Sci 32: 1238–1242 [Google Scholar]

- Lang Z, Wang Y, Tang K, Tang D, Datsenka T, Cheng J, Zhang Y, Handa AK, Zhu JK(2017) Critical roles of DNA demethylation in the activation of ripening-induced genes and inhibition of ripening-repressed genes in tomato fruit. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: E4511–E4519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Law JA, Jacobsen SE(2010) Establishing, maintaining and modifying DNA methylation patterns in plants and animals. Nat Rev Genet 11: 204–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Zhu J, Hu F, Ge S, Ye M, Xiang H, Zhang G, Zheng X, Zhang H, Zhang S, et al. (2012) Single-base resolution maps of cultivated and wild rice methylomes and regulatory roles of DNA methylation in plant gene expression. BMC Genomics 13: 300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang D, Zhang Z, Wu H, Huang C, Shuai P, Ye CY, Tang S, Wang Y, Yang L, Wang J, et al. (2014) Single-base-resolution methylomes of Populus trichocarpa reveal the association between DNA methylation and drought stress. BMC Genet 15(Suppl 1): S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin IW, Sosso D, Chen LQ, Gase K, Kim SG, Kessler D, Klinkenberg PM, Gorder MK, Hou BH, Qu XQ, et al. (2014) Nectar secretion requires sucrose phosphate synthases and the sugar transporter SWEET9. Nature 508: 546–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindroth AM, Cao X, Jackson JP, Zilberman D, McCallum CM, Henikoff S, Jacobsen SE(2001) Requirement of CHROMOMETHYLASE3 for maintenance of CpXpG methylation. Science 292: 2077–2080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Y, Yang M, Hu D, Yang Z, Ma S, Li X, Xiong L(2017) The OsMYB30 transcription factor suppresses cold tolerance by interacting with a JAZ protein and suppressing β-amylase expression. Plant Physiol 173: 1475–1491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Zhang D, Miao Q, Yang J, Xuan Y, Hu Y(2017) Essential role of sugar transporter OsSWEET11 during the early stage of rice grain filling. Plant Cell Physiol 58: 863–873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirouze M, Paszkowski J(2011) Epigenetic contribution to stress adaptation in plants. Curr Opin Plant Biol 14: 267–274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirouze M, Vitte C(2014) Transposable elements, a treasure trove to decipher epigenetic variation: Insights from Arabidopsis and crop epigenomes. J Exp Bot 65: 2801–2812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SJ, Kim YS, Kwon CW, Park HK, Jeong JS, Kim JK(2009) Overexpression of the transcription factor AP37 in rice improves grain yield under drought conditions. Plant Physiol 150: 1368–1379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ricciardi L, Stelluti M(1995) The response of durum wheat cultivars and Rht1/rht1 near-isogenic lines to simulated photosynthetic stresses. J Genet Breed 49: 365–375 [Google Scholar]

- Sahu PP, Pandey G, Sharma N, Puranik S, Muthamilarasan M, Prasad M(2013) Epigenetic mechanisms of plant stress responses and adaptation. Plant Cell Rep 32: 1151–1159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scnyhder H.(1993) The role of carbohydrate storage and redistribution in the source-sink relations of wheat and barley during grain filling: A review. New Phytol 123: 233–245 [Google Scholar]

- Shamimuzzaman M, Vodkin L(2013) Genome-wide identification of binding sites for NAC and YABBY transcription factors and co-regulated genes during soybean seedling development by ChIP-seq and RNA-seq. BMC Genomics 14: 477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sperotto RA, Ricachenevsky FK, Duarte GL, Boff T, Lopes KL, Sperb ER, Grusak MA, Fett JP(2009) Identification of up-regulated genes in flag leaves during rice grain filling and characterization of OsNAC5, a new ABA-dependent transcription factor. Planta 230: 985–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud H, Do T, Du J, Zhong X, Feng S, Johnson L, Patel DJ, Jacobsen SE(2014) Non-CG methylation patterns shape the epigenetic landscape in Arabidopsis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 21: 64–72 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takai T, Fukuta Y, Shiraiwa T, Horie T(2005) Time-related mapping of quantitative trait loci controlling grain-filling in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Exp Bot 56: 2107–2118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuong B, Bouman T(2000) Field water mangement to save water and increase its productivity in irrigated lowland rice. Agric Water Manage 49: 11–30 [Google Scholar]

- Uauy C, Distelfeld A, Fahima T, Blechl A, Dubcovsky J(2006) A NAC gene regulating senescence improves grain protein, zinc, and iron content in wheat. Science 314: 1298–1301 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Li H, Wang K, Yang J, Duan M, Zhang J, Ye N(2020) Regulation of gene expression involved in the remobilization of rice straw carbon reserves results from moderate soil drying during grain filling. Plant J 101: 604–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GQ, Li HX, Feng L, Chen MX, Meng S, Ye NH, Zhang J(2019) Transcriptomic analysis of grain filling in rice inferior grains under moderate soil drying. J Exp Bot 70: 1597–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Zhao X, Pan Y, Zhu L, Fu B, Li Z(2011a) DNA methylation changes detected by methylation-sensitive amplified polymorphism in two contrasting rice genotypes under salt stress. J Genet Genomics 38: 419–424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang WS, Pan YJ, Zhao XQ, Dwivedi D, Zhu LH, Ali J, Fu BY, Li ZK(2011b) Drought-induced site-specific DNA methylation and its association with drought tolerance in rice (Oryza sativa L.). J Exp Bot 62: 1951–1960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J, Zhou S, Gong X, Song Y, van Nocker S, Ma F, Guan Q(2018) Single-base methylome analysis reveals dynamic epigenomic differences associated with water deficit in apple. Plant Biotechnol J 16: 672–687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Luo D, Yang B, Frommer WB, Eom JS(2018) SWEET11 and 15 as key players in seed filling in rice. New Phytol 218: 604–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhang J(2006) Grain filling of cereals under soil drying. New Phytol 169: 223–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J, Zhang J, Wang Z, Zhu Q(2001) Activities of starch hydrolytic enzymes and sucrose-phosphate synthase in the stems of rice subjected to water stress during grain filling. J Exp Bot 52: 2169–2179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemach A, Kim MY, Hsieh PH, Coleman-Derr D, Eshed-Williams L, Thao K, Harmer SL, Zilberman D(2013) The Arabidopsis nucleosome remodeler DDM1 allows DNA methyltransferases to access H1-containing heterochromatin. Cell 153: 193–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemach A, Kim MY, Silva P, Rodrigues JA, Dotson B, Brooks MD, Zilberman D(2010) Local DNA hypomethylation activates genes in rice endosperm. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107: 18729–18734 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Tieman DM, Jiao C, Xu Y, Chen K, Fei Z, Giovannoni JJ, Klee HJ(2016) Chilling-induced tomato flavor loss is associated with altered volatile synthesis and transient changes in DNA methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113: 12580–12585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H, Li H, Yuan L, Wang Z, Yang J, Zhang J(2012) Post-anthesis alternate wetting and moderate soil drying enhances activities of key enzymes in sucrose-to-starch conversion in inferior spikelets of rice. J Exp Bot 63: 215–227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu JK.(2009) Active DNA demethylation mediated by DNA glycosylases. Annu Rev Genet 43: 143–166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu N, Cheng S, Liu X, Du H, Dai M, Zhou DX, Yang W, Zhao Y(2015) The R2R3-type MYB gene OsMYB91 has a function in coordinating plant growth and salt stress tolerance in rice. Plant Sci 236: 146–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]