Cell-wall thickening, rather than starch accumulation, leads to a decrease in mesophyll conductance after a reduction in the sink–source ratio in soybean and French bean.

Abstract

It has been argued that accumulation of nonstructural carbohydrates triggers a decrease in Rubisco content, which downregulates photosynthesis. However, a decrease in the sink–source ratio in several plant species leads to a decrease in photosynthesis and increases in both structural and nonstructural carbohydrate content. Here, we tested whether increases in cell-wall materials, rather than starch content, impact directly on photosynthesis by decreasing mesophyll conductance. We measured various morphological, anatomical, and physiological traits in primary leaves of soybean (Glycine max) and French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) grown under high- or low-nitrogen conditions. We removed other leaves 2 weeks after sowing to decrease the sink–source ratio and conducted measurements 0, 1, and 2 weeks after defoliation.

In both species, leaf mass per area (LMA), cell-wall mass per area (CMA), and starch content increased about 2-fold in defoliated (Def) plants compared to control (Ct) plants. Concurrently, photosynthetic rate, stomatal conductance, and mesophyll conductance (gm) decreased in Def plants. The value gm was negatively correlated with CMA but not with starch content. Consistent with the increase in CMA, defoliation significantly increased cell-wall thickness (CWT). We conclude that gm was reduced by cell-wall thickening rather than starch accumulation. Therefore, the downregulation of photosynthesis in response to a decrease in the sink–source ratio in soybean (Glycine max) and French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) is associated with stomatal closure, a reduction in gm, and reduced Rubisco activation.

Leaf photosynthetic rate is mainly limited by stomatal conductance (gs), which is an indicator of stomatal opening; gm, which is the diffusivity of CO2 from the intercellular space to the chloroplast stroma through the cell wall and cell membrane; and content and activity of Rubisco, which determine the maximum carboxylation rate. It is thought that these factors change in response to changes in the sink–source balance and both biotic and abiotic factors, which contribute to the optimization of photosynthesis under fluctuating natural environments (Yamori, 2016).

In general, nonstructural carbohydrates (NSCs; soluble sugars and starch) accumulate in source leaves when the sink–source ratio is decreased by sink removal, low soil nitrogen availability, high-light intensity, and/or elevated CO2 conditions (Ainsworth et al., 2004; Kasai, 2008; Sugiura et al., 2019). The accumulated NSCs could decrease Rubisco content through the suppression of photosynthesis-related genes (Sheen, 1994), and the photosynthetic rate is downregulated consequently in various plant species (Krapp and Stitt, 1995; McCormick et al., 2008).

In addition to the biochemical alterations, morphological and anatomical characteristics, such as chloroplast-surface area and CWT, could change depending on the sink–source ratio and leaf developmental stages (Miyazawa et al., 2003; Teng et al., 2006). Starch granules that accumulate inside chloroplasts could hinder CO2 diffusion in the liquid phase by acting as physical barriers (Nafziger and Koller, 1976; Nakano et al., 2000; Sawada et al., 2001). Because these anatomical and structural factors affecting CO2 diffusion could increase or decrease gm, the downregulation of photosynthesis could be influenced not only physiologically but also morphologically (Tholen et al., 2008; Evans et al., 2009; Terashima et al., 2011).

Previously, we have reported how morphological and anatomical traits change in response to sink–source imbalance and cause the downregulation of photosynthesis. In reciprocally grafted Raphanus sativus with different sink activities, NSC level was unrelated to either maximum photosynthetic rate or Rubisco content. By contrast, CMA and relevant leaf anatomical characteristics, such as mesophyll cell size and intercellular air space, were significantly altered with the decrease in sink–source ratio (Sugiura et al., 2015, 2017). Sugiura et al. (2016) reported that NSCs and leaf structural carbohydrates both increase in response to sudden changes in sink–source ratio induced by transferring plants to low-nitrogen (LN) conditions or removing sink leaves in Japanese knotweed (Polygonum cuspidatum). We further clarified interspecific differences in how sink–source imbalance and NSC level cause the downregulation of photosynthesis among three legume plants. We found in soybean that decreasing sink–source ratio by defoliation causes an increase in CMA that could decrease gm and contribute toward photosynthetic downregulation, whereas excess NSC accumulation selectively decreased Rubisco content and photosynthetic rate in French bean (Sugiura et al., 2019).

These findings suggest that when NSCs accumulate in source leaves, a downregulation of photosynthesis could result not only from decreases in content and activity of Rubisco but also from anatomical factors, such as an increase in CWT leading to reduced chloroplast CO2 concentrations. However, no studies have investigated the effects of starch accumulation, content and thickness of cell walls, and other anatomical and physiological traits on gm at the same time. Some reviews evaluate relationships among the gm-related traits measured by different techniques derived from different species belonging to different functional groups (Terashima et al., 2006; Evans et al., 2009). Recent studies also reveal a negative correlation between mesophyll conductance and CWT among plants from different functional groups (Tosens et al., 2016; Onoda et al., 2017; Veromann-Jürgenson et al., 2017; Carriquí et al., 2019). However, ideally responses of these traits to sink–source balance should be evaluated using the same plant species and the same techniques under certain environmental conditions.

This study aimed to clarify the contributions of starch accumulation and cell-wall thickening to the downregulation of photosynthesis responding to the sink–source imbalance in a comprehensive manner. To obtain leaves with a wide range of starch content and photosynthetic capacity, we grew soybean and French bean under two different nitrogen fertilizer conditions (Fig. 1). To manipulate sink–source ratio, we removed sink leaves according to Sugiura et al. (2019), expecting increases in cell-wall content and thickness in primary leaves. We also aimed to quantitatively clarify the effect of starch accumulation on the hindrance of CO2 diffusion by evaluating gm of shade-treated plants with decreased leaf starch content. We calculated gm by measuring carbon isotope discrimination using a tunable-diode laser absorption spectroscope and precisely analyzed CWT by transmission electron microscopy (TEM). Lastly, we discuss possible mechanisms and the ecological significance of the downregulation of photosynthesis by physiological and anatomical changes.

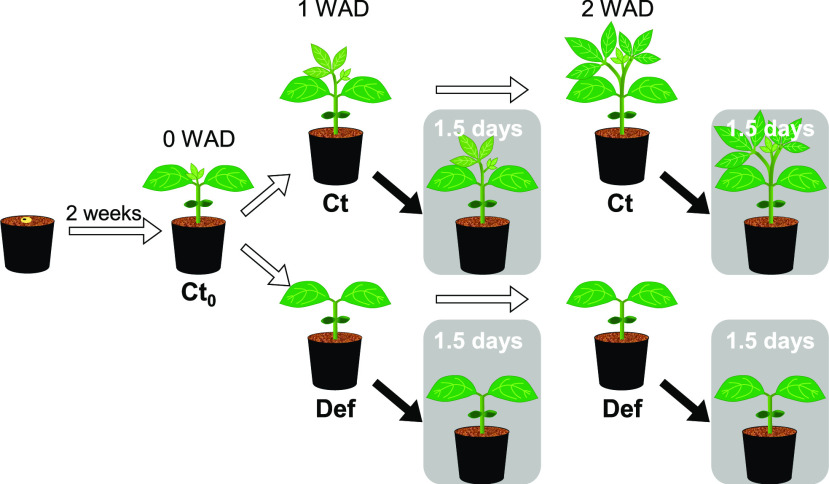

Figure 1.

The experimental design of this study. Seedlings of soybean and French bean were grown under LN or HN for 2 weeks until primary leaves fully expanded. After the first measurements of Ct0, half of the seedlings were grown under Ct conditions, and trifoliate leaves of the other half of the seedlings were Def. The second and third measurements were conducted at 1 and 2 WAD. At the second and third measurements, four seedlings were shaded for 1.5 d, where the shaded Ct and Def plants received a relative PPFD of 3% compared to nonshaded plants. Samples for light microscopy and TEM were taken at 0 and 2 WAD.

RESULTS

Leaf Physiological Changes

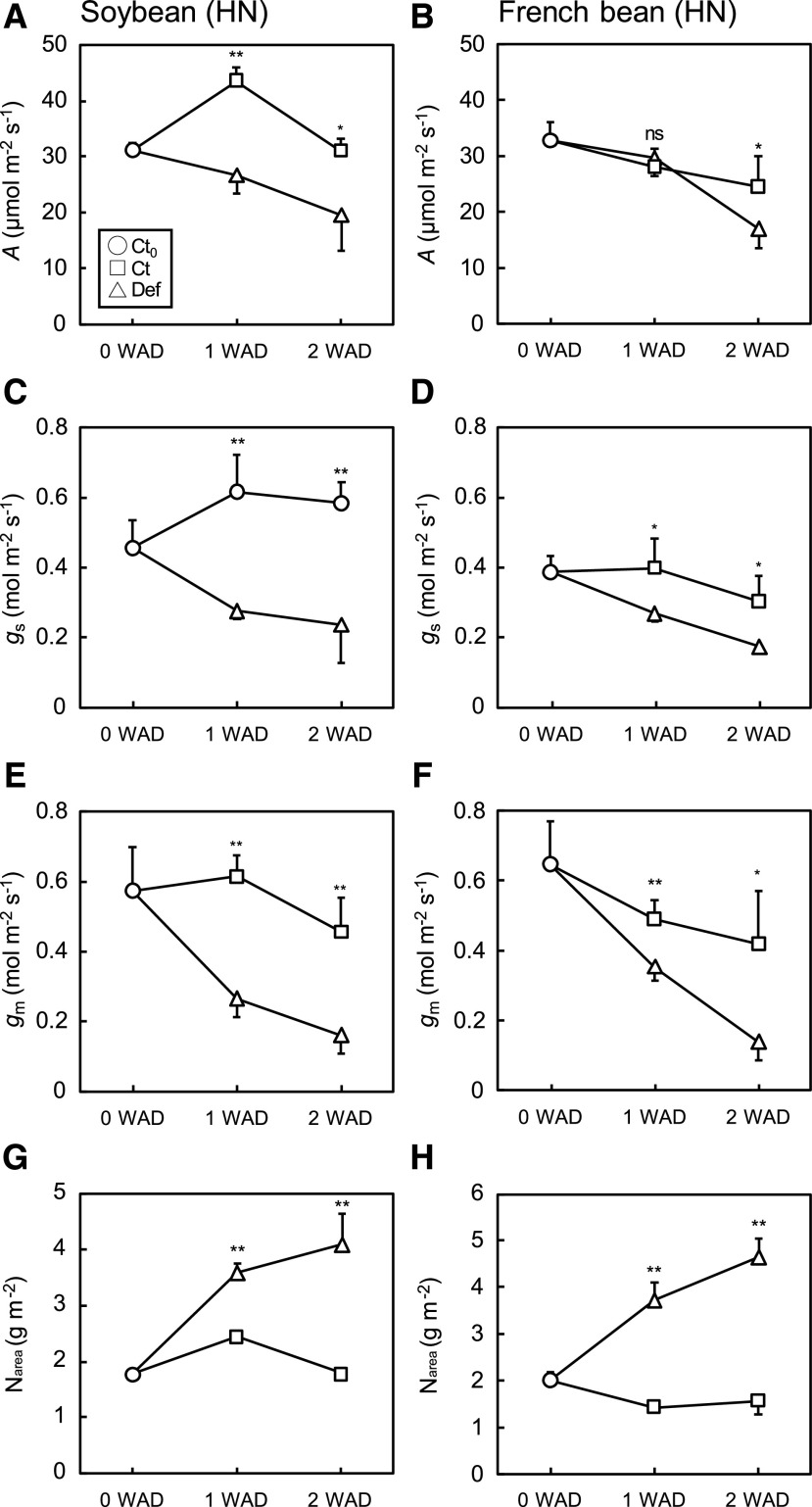

Photosynthetic traits measured at 2% O2 were markedly altered by the experimental treatments in both species. In soybean and French bean grown under high nitrogen (HN), the photosynthetic rate (A; Fig. 2, A and B), gs (Fig. 2, C and D), and gm (Fig. 2, E and F) values were significantly higher in Ct plants than in Def plants. On the other hand, Narea gradually increased in Def plants and was significantly higher than in Ct plants (Fig. 2, G and H). For soybean plants grown under LN, A (Supplemental Fig. S1A), and gs (Supplemental Fig. S1C) values were not significantly different between Ct and Def plants, while defoliation decreased gm (Supplemental Fig. S1E) and increased leaf nitrogen content per area (Narea; Supplemental Fig. S1G). For French bean plants grown under LN, there were no significant differences between Ct and Def plants in A (Supplemental Fig. S1B), gs (Supplemental Fig. S1D), and gm (Supplemental Fig. S1F) values, but defoliation increased Narea after 2 weeks (Supplemental Fig. S1H). Shading did not significantly affect these physiological traits (Supplemental Table S1).

Figure 2.

Photosynthetic characteristics in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN conditions. A and B, A at 2% O2. C and D, gs at 2% O2. E and F, gmat 2% O2. G and H, Narea. Values were obtained at 0, 1, and 2 WAD. Data are means (+ or –sd), n = 4. Significant differences between Ct and Def plants were determined by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, and ns, P > 0.05).

We identified positive correlations among the photosynthetic characteristics. A was positively correlated with gs and gm among Ct0, Ct, Def, and shaded plants grown under HN and LN conditions in both soybean (Supplemental Fig. S2, A and C) and French bean (Supplemental Fig. S2, B and D). Maximum carboxylation rate (Vcmax) and electron transport rate (J1500) were higher in plants grown under HN conditions than in plants grown under LN conditions (Table 1). In both species, defoliation greatly increased Vcmax and J1500, whereas shading did not affect them (Supplemental Table S1). Total Rubisco content was strongly and linearly correlated with Narea, regardless of treatment, in soybean (Supplemental Fig. S3A) and French bean (Supplemental Fig. S3B). However, the increase in Rubisco content after defoliation did not result in equivalent increases in Vcmax in soybean (Supplemental Fig. S3C) and French bean (Supplemental Fig. S3D), indicating that in both species, Rubisco activation state was reduced by the defoliation treatment.

Table 1. Photosynthetic characteristics in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under LN and HN conditions.

Vcmax (μmol m−2 s−1) and J1500 (μmol m−2 s−1). Values of Ct0 plants were measured at 0 WAD, and values of Ct and Def plants were obtained at 1 and 2 WAD. Data are means (±sd), n = 4. Significant differences between Ct and Def plants were determined by Student’s t test (**, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; ns, P > 0.05).

| Nitrogen Conditions | Soybean | Significance | 1 WAD | Significance | 2 WAD | French bean | Significance | 1 WAD | Significance | 2 WAD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ct0 | Ct | Def | Ct | Def | Ct0 | Ct | Def | Ct | Def | ||||||

| LN | Vcmax | 54.9 ± 15.7 | ns | 72.6 ± 3.3 | 88.8 ± 28.1 | ** | 34.7 ± 10.7 | 117.7 ± 20.1 | 76.8 ± 22.9 | ns | 42.2 ± 16.9 | 73.4 ± 7.9 | ** | 22.6 ± 4.3 | 49.8 ± 15.8 |

| J1500 | 96.1 ± 22.4 | * | 131.2 ± 8.5 | 153.8 ± 32.3 | * | 68.8 ± 21 | 180.4 ± 25.7 | 127.5 ± 33.3 | * | 79 ± 28.2 | 116.3 ± 15.7 | ** | 42.7 ± 7.2 | 83.3 ± 21.8 | |

| HN | Vcmax | 103.2 ± 9.1 | ns | 121.8 ± 17.6 | 110.8 ± 5.1 | ns | 112.3 ± 6 | 104 ± 22.6 | 109.9 ± 8.5 | ns | 72.4 ± 11.6 | 139.1 ± 18.6 | ns | 83.7 ± 13.2 | 110.9 ± 5 |

| J1500 | 172.4 ± 11.1 | ** | 198.2 ± 21.5 | 182.9 ± 13.7 | ** | 160.7 ± 6.6 | 154.1 ± 22.6 | 186.3 ± 20.5 | ** | 122.5 ± 23.4 | 209.2 ± 18 | ns | 132.3 ± 27.4 | 161.2 ± 22.4 | |

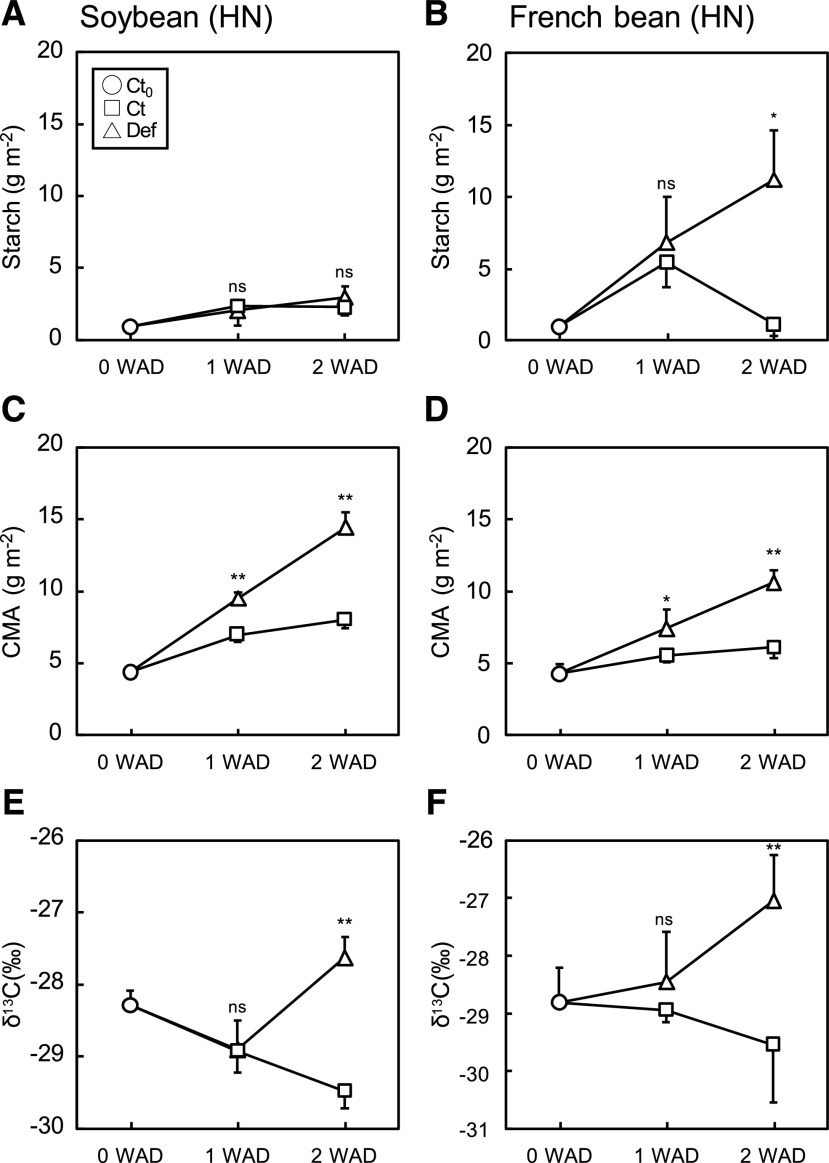

LMA, Starch, Cell Wall, and δ13C

NSCs and CMA were both significantly affected by the experimental treatments. For soybean, starch content was greater under LN than HN (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S4A), whereas nitrogen treatment did not affect starch content in French bean (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. S4B). Defoliation did not affect starch content in soybean (Fig. 3A; Supplemental Fig. S4A), whereas it increased starch content in French bean at 2 weeks after defoliation (WAD) regardless of nitrogen treatment (Fig. 3B; Supplemental Fig. S4B). Shading for 1.5 d significantly decreased starch content by 35% to 67% and 24% to 90% in soybean and French bean, respectively (Table 2), except for Ct plants of French bean grown under HN condition at 2 WAD. The results of two-way ANOVA showed that defoliation did not alter starch content in soybean, whereas shading significantly altered starch content in both species (Supplemental Table S1). French bean showed higher levels of soluble sugars (Glc and Suc) than soybean under LN and HN conditions, which tended to be higher in Def plants than Ct plants at 2 WAD (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Figure 3.

Starch content and cell-wall content in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN conditions. A and B, Starch content. C and D, CMA. E and F, δ13C. Values were obtained at 0, 1, and 2 WAD. Data are means (+ or –sd), n = 4. Significant differences between Ct and Def plants were determined by Student’s t test (**P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, and ns, P > 0.05).

Table 2. Percent change in starch by shade treatment in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under LN and HN conditions.

Values of Ct and Def plants were obtained at 1 and 2 WAD. Data are means (±sd), n = 4.

| Percent Change in Starch by Shading | Soybean | French Bean | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 WAD | 2 WAD | 1 WAD | 2 WAD | |||||

| Nitrogen conditions | Ct | Def | Ct | Def | Ct | Def | Ct | Def |

| LN | −58.6 | −67.4 | −34.8 | −54.5 | −52.4 | −46.0 | −31.7 | −40.3 |

| HN | −62.3 | −40.8 | −51.3 | −62.2 | −90.1 | −59.4 | 0.5 | −24.0 |

CMA gradually increased over time but significantly increased after defoliation in soybean under both HN and LN (Fig. 3C; Supplemental Fig. S4C), and French bean under HN (Fig. 3D). The increase in CMA was greater in soybean than in French bean at both nitrogen conditions. Leaf δ13C significantly increased in Def plants especially under HN conditions at 2 WAD (Fig. 3, E and F) but was less significant under LN conditions (Supplemental Fig. S4, E and F), consistent with the changes in starch content. Overall, the results of two-way ANOVA showed that the effect of defoliation significantly increased CMA and δ13C, whereas shading did not alter CMA and δ13C in both species at both nitrogen conditions (Supplemental Table S1).

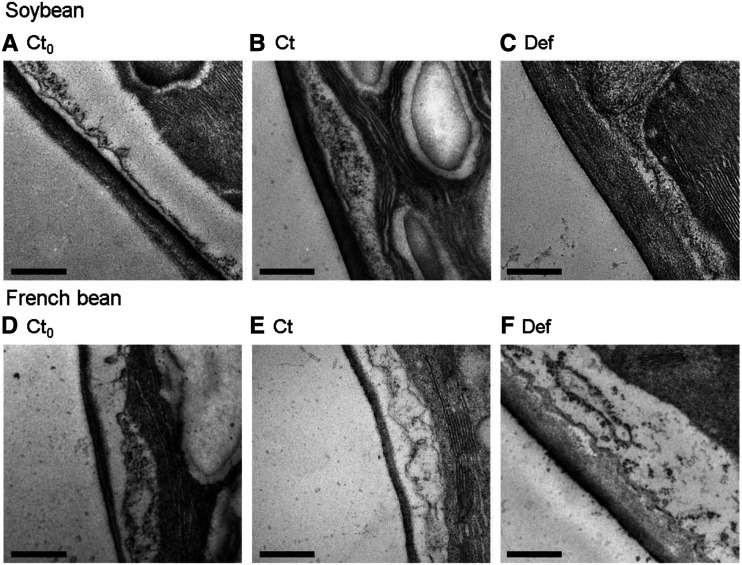

Leaf Anatomy

Leaf anatomical traits clearly differed between LN and HN conditions and were altered by defoliation in soybean and French bean. LMA significantly increased with defoliation (Table 3). TEM images showed that mesophyll cell walls thickened after defoliation in soybean (Fig. 4, A–C) and French bean (Fig. 4, D–F). CWT and leaf thickness were significantly greater in Def plants than in Ct plants at 2 WAD, except for French bean leaf thickness under LN conditions (Table 3). CWT increased ∼2-fold and 2.5- to 3-fold in soybean and French bean, respectively, whereas leaf thickness increased only 1.3 to 1.5 times in both species. The surface area of mesophyll cell walls exposed to the intercellular space (Sm, m2 m−2) and the surface area of chloroplasts facing the intercellular space (Sc, m2 m−2) were also generally higher in Def plants than in Ct plants, and Sm changed in proportion to leaf thickness. Sc/Sm was not altered by defoliation, and the values ranged from 0.79 to 0.99 for soybean grown under LN and HN conditions and French bean grown under HN conditions. In contrast, the values of Sc/Sm were 0.54 to 0.64 in Ct and Def plants of French bean grown at LN conditions, which were clearly lower than other plants.

Table 3. Anatomical characteristics in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under LN and HN conditions.

LMA, CWT from TEM, leaf thickness, Sc, Sm, and the ratio of Sc/Sm from light microscopy. Values of Ct0 plants were obtained at 0 WAD, and values of Ct and Def plants were obtained at 2 WAD. Data are means (±sd), n = 4. Significant differences between Ct and Def plants were determined by Student’s t test (**, P < 0.01; *, P < 0.05; and ns, P > 0.05).

| Nitrogen Conditions | Units of Measure | Soybean | 2 WAD | French Bean | 2 WAD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ct0 | Ct | De | Ct0 | Ct | De | ||

| LN | LMA (g m−2) | 29.73 ± 1.27 | 41.49** ± 8.62 | 68.40 ± 7.51 | 32.83 ± 3.75 | 25.25** ± 1.50 | 57.89 ± 10.96 |

| CWT (nm) | 129.2 ± 22.3 | 166.3** ± 34.9 | 354.1 ± 54.3 | 105.5 ± 21.7 | 99.5** ± 8.6 | 251.3 ± 71.6 | |

| Leaf thickness (μm) | 185.7 ± 18.1 | 256.2** ± 24.0 | 336.8 ± 33.4 | 183.7 ± 23.9 | 318.0 ns ± 32.4 | 410.1 ± 81.7 | |

| Sc (m2 m−2) | 13.7 ± 1.3 | 17.8** ± 1.6 | 23.0 ± 2.3 | 17.5 ± 2.6 | 10.8** ± 0.8 | 16.8 ± 2.8 | |

| Sm (m2 m−2) | 17.3 ± 1.6 | 21.4** ± 1.7 | 26.0 ± 1.7 | 19.4 ± 2.0 | 20.4** ± 3.1 | 26.1 ± 2.3 | |

| Sc/Sm (m2 m−2) | 0.79 ± 0.06 | 0.83 ns ± 0.10 | 0.88 ± 0.07 | 0.90 ± 0.05 | 0.54 ns ± 0.06 | 0.64 ± 0.08 | |

| HN | LMA (g m−2) | 26.04 ± 0.93 | 36.96** ± 2.34 | 68.11 ± 4.57 | 27.12 ± 3.04 | 36.20** ± 4.41 | 92.25 ± 14.70 |

| CWT (nm) | 112.3 ± 11.6 | 156.1** ± 33.0 | 326.4 ± 59.1 | 95.1 ± 10.3 | 101.6** ± 17.5 | 308.1 ± 29.2 | |

| Leaf thickness (μm) | 230.6 ± 15.0 | 274.3**±33.3 | 395.4 ± 16.2 | 287.7 ± 31.4 | 352.3** ± 14.9 | 545.1 ± 87.5 | |

| Sc (m2 m−2) | 18.4 ± 1.5 | 17.9** ± 2.5 | 27.9 ± 1.5 | 17.9 ± 3.0 | 16.9* ± 2.5 | 24.4 ± 5.1 | |

| Sm m2 m−2) | 19.4 ± 1.6 | 20.7* ±3.9 | 29.9 ± 1.3 | 18.2 ± 3.1 | 19.9 ns ± 2.3 | 27.5 ± 6.2 | |

| Sc/Sm (m2 m−2) | 0.95 ± 0.00 | 0.87 ns ± 0.06 | 0.93 ± 0.02 | 0.99 ± 0.00 | 0.85 ns ± 0.05 | 0.89 ± 0.08 | |

Figure 4.

TEM images showing CWT in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean. A and D, Ct0 plants at 0 WAD. B and E, Ct plants at 2 WAD. C and F, Def plants at 2 WAD grown under HN conditions. Scale bars = 500 nm.

Relationships between Physiology and Anatomy

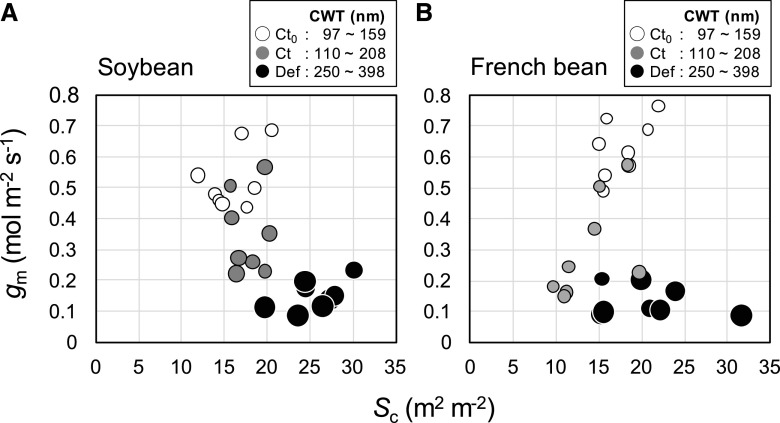

We visualized the relationships among gm, Sc, and CWT. In soybean, gm declined considerably over time for Ct plants without any change in Sc but with an increase in CWT. Furthermore, Def plants had the lowest gm, the thickest cell walls, and the highest Sc (Fig. 5A). By contrast for French bean, the significant decrease in gm for Ct plants over time was accompanied by a slight decrease in Sc and a slight increase in CWT. Again, Def plants had the lowest gm, the thickest cell walls, and the highest Sc (Fig. 5B).

Figure 5.

Relationships between gm and Sc in the primary leaves of soybean (A) and French bean (B), grown under HN and LN conditions. Values were obtained at 0 and 2 WAD. Open circle, gray circle, and closed circle represent Ct0, Ct, and Def plants at 2 WAD, respectively. Circle size represents the CWT.

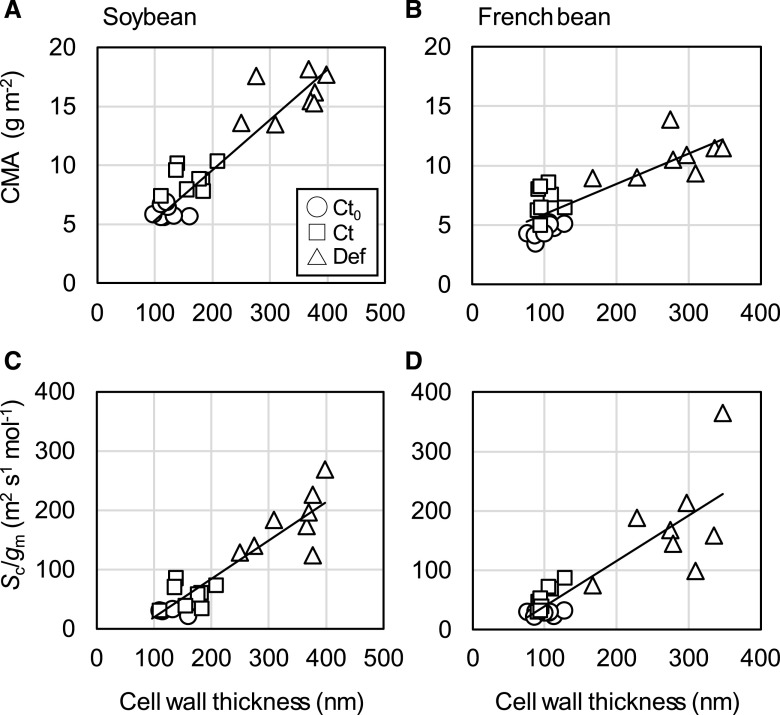

Comparison of anatomy, morphology, and physiology in the leaves used for TEM analysis showed that changes in CWT were reflected in both morphological and physiological traits. A single linear relationship between CMA and CWT was apparent in soybean, regardless of treatment (Fig. 6A). In French bean, although CMA correlated with CWT, Ct plant CMA increased over time without any change in CWT (Fig. 6B). The mesophyll resistance expressed per unit of chloroplast surface area exposed to intercellular airspace, Sc/gm, was positively correlated with CWT in both soybean (Fig. 6C) and French bean (Fig. 6D). Importantly, the increase in Sc/gm after defoliation implies either a decrease in wall permeability associated with altered properties of these thicker walls or an additional decrease in membrane permeability. CWT had no impact on the draw-down of CO2 between the atmosphere and intercellular airspace (Ca–Ci) in either species (Supplemental Fig. S6, A and B). However, the draw-down of CO2 from the intercellular airspace to the site of carboxylation in the chloroplast (Ci–Cc) increased in both soybean (Supplemental Fig. S6C) and French bean (Supplemental Fig. S6D), despite reduced CO2 assimilation rates.

Figure 6.

Relationships among CMA, Sc/gm, and CWT in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN and LN conditions. Values were obtained at 0 and 2 WAD. Open circle, open square, and open triangle represent Ct0 at 0 WAD, Ct at 2 WAD, and Def plants at 2 WAD, respectively. Regression lines are shown for all the plants. Values of R2 are 0.86 (A), 0.69 (B), 0.86 (C), and 0.74 (D).

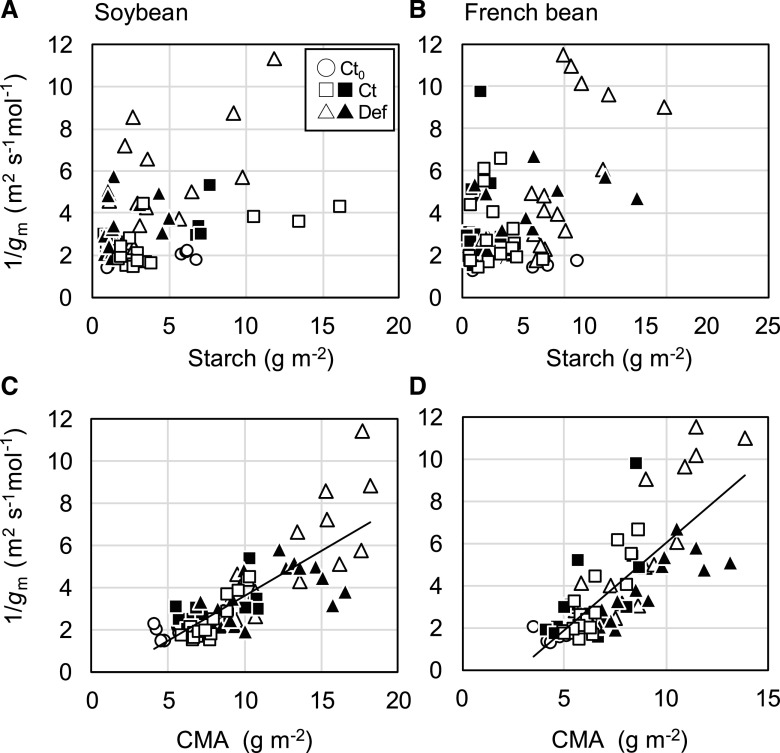

There was no evidence that mesophyll resistance increased with starch content in soybean (Fig. 7A) and French bean (Fig. 7B). On the other hand, there were strong positive linear correlations between 1/gm and CMA among all the treatments in both soybean (Fig. 7C) and French bean (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Relationships between 1/gm, starch content, and CMA in the primary leaves of soybean (A and C) and French bean (B and D) grown under HN and LN conditions. Values were obtained at 0, 1, and 2 WAD. Open circle, open square, and open triangle represent Ct0, Ct, and Def plants, respectively. Closed square and closed triangle represent Ct and Def plants shaded for 1.5 d at 1 and 2 WAD. Regression lines are shown for all the plants in C and D. Values of R2 are 0.65 (C) and 0.61 (D).

δ13C was negatively correlated with Cc among Ct0, Ct, Def, and shaded plants in soybean (Supplemental Fig. S7A) and French bean (Supplemental Fig. S7B), consistent with the accumulated starch and additional cell-wall material being assimilated with reduced chloroplast CO2 concentrations.

DISCUSSION

Cell Wall as a Greater Limiting Factor than Starch for gm

Our physiological and anatomical analyses demonstrate that cell-wall mass and thickness greatly increased in response to the defoliation treatment (Fig. 4; Table 3), thereby contributing to the decrease in gm (Figs. 6, C and D, and 7, C and D). Although LN and shading treatments caused significant changes in starch content (Table 2; Supplemental Fig. S1), this did not affect gm in either species (Fig. 7, A and B). There was a positive correlation between CMA and CWT (Fig. 6, A and B), and the lower chloroplast CO2 concentration (Cc) in leaves from the defoliation treatment was reflected in an increase in δ13C (Supplemental Fig. S7). These results demonstrate that mesophyll conductance was strongly affected by cell-wall thickening (Fig. 4), but was independent of starch accumulation.

This conclusion is supported by previous studies. Defoliation led to an increase in Narea and Rubisco content in response to the decreased sink activity in Japanese knotweed (Sugiura et al., 2016) and soybean (Sugiura et al., 2019). Despite increases in Narea and Rubisco content, photosynthetic rate did not increase. However, the structural carbohydrate, such as cell walls, markedly increased. Consequently, one might expect that the increased CWT could decrease gm and thus decrease A. In another study, CMA increased along with the NSC accumulation when sink–source ratio was decreased by low nitrogen availability in the leaves of reciprocally grafted radish (R. sativus; Sugiura et al., 2017). Increased cell-wall mass and thickness in response to a decreased sink–source ratio could be an adaptive mechanism to mitigate against excess accumulation of NSCs in radish plants.

In this study, CMA increased in Ct plants grown under LN conditions (on average 12%–13%), suggesting that a decrease in sink–source ratio under LN conditions caused increases in CMA and NSCs at the same time. Furthermore, CMA increased (Fig. 3, C and D; Supplemental Fig. S4, C and D) and gm decreased (Fig. 2, E and F; Supplemental Fig. S1, E and F) in the Ct plants as the growth stage progressed. This suggests that the decrease in gm observed in old senescing leaves can be partly explained by an increase in cell-wall mass (Loreto et al., 1994). On the other hand, a starch excess mutant of Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana; gwd1) does not show increased CWT and decreased gm compared with wild-type Arabidopsis. Furthermore, changes in mesophyll resistance (Sc/gm) were associated with thicker cell walls rather than with excess starch content among wild type and carbon-metabolism mutants of Arabidopsis (Mizokami et al., 2019). These results and our present results (Fig. 7) suggest that the increased mass and thickness of the cell wall contributes more to the decreased gm than starch.

Because excess accumulation of sugar-derived reactive carbonyls (RCs) could inactivate physiological functions of proteins in photosynthetic organisms, plants possess a RC-scavenging system by detoxifying the RCs (Shimakawa et al., 2014). In addition to the scavenging system of sugar-derived RCs, the observed increase in cell-wall mass could be another mechanism to avoid diabetic conditions by consuming excess NSCs and suppressing further carbon assimilation by decreasing gs and gm and deactivating Rubisco (Fig. 2; Supplemental Figs. S1 and S2).

Defoliation and Shading to Manipulate Sink–Source Balance

As in previous studies (Sugiura et al., 2016, 2019), we removed trifoliate leaves to cause the sink–source imbalance. Other studies have manipulated sink–source balance by partial defoliation (von Caemmerer and Farquhar, 1984; Turnbull et al., 2007), depodding (Nakano et al., 2000), or using mutants with different sink capacity (Ainsworth et al., 2004) to investigate how sink–source imbalance could affect photosynthetic traits. Consistent with these studies, partial defoliation resulted in an increase in photosynthetic capacity (Vcmax, J1500 in Def plants; Table 1), Narea, and Rubisco content (Supplemental Fig. S3, A and B). Defoliation led to a decrease in Vcmax per Rubisco site, suggestive of a reduction in Rubisco activation state (Supplemental Fig. S3, C and D), which decreases in leaves with greater Rubisco content in wheat (Triticum aestivum; Carmo-Silva et al., 2017; Silva-Pérez et al., 2020) and apple (Malus domestica; Cheng and Fuchigami, 2000). It is also possible that the Rubisco activation state was decreased by lower Cc due to the increased CWT hindering CO2 diffusion (Supplemental Fig. S6). Increases in leaf structural carbohydrate in response to herbivory or artificial defoliation may be a means of physical defense (Nabeshima et al., 2001), so the increase in CMA observed here (Fig. 3, C and D; Supplemental Fig. S4, C and D) in response to defoliation could also be interpreted as a plant response to herbivory. However, such a protective physical barrier is usually formed at the site of damaged tissue (Neilson et al., 2013), and the primary leaves were not damaged in this study. Therefore, the observed increase in cell-wall mass and thickness contributed more to the decrease in CO2 diffusivity than physical defense against insects.

Short-term moderate shading (Fig. 1) is a useful experimental method to reduce the level of NSCs, especially starch, in plant tissues (Table 2), whereas extreme shading could promote a senescence-induced decrease in photosynthesis (Vlcková et al., 2006). In this study, maximum photosynthetic capacity (Vcmax and J1500), other photosynthetic characteristics (A, gs, and gm), and leaf morphological traits (CMA) were not affected by the shading at 3% photosynthetically active photon flux density (PPFD) for 1.5 d (Supplemental Table S1), indicating that this experimental shading was suitable for the research purpose.

How Can We Understand Inconsistent Relationships between Physiology and Anatomy Associated with gm among Different Studies?

Several studies report significant positive correlations between gm and Sc (the surface area of chloroplasts facing intercellular airspace) among wild type and chloroplast-positioning mutants of Arabidopsis (Tholen et al., 2008); among 35 ferns (Polypodiopsida spp.) and fern allies (Tosens et al., 2016); among seven sclerophyllous Mediterranean oaks (Peguero-Pina et al., 2017); and for deciduous species at different growth stages (Tosens et al., 2012). On the other hand, no significant correlations were found between gm and Sc among 15 species selected from different functional groups (annual herb, deciduous, and evergreen; Tomás et al., 2013), among wild type and carbon-metabolism mutants of Arabidopsis grown under ambient and elevated CO2 conditions (Mizokami et al., 2019), and among soybean and French bean with altered sink–source ratio (Fig. 5). These inconsistent results may indicate that physiological and anatomical characteristics in addition to Sc might be markedly different depending on plant species and leaf age in the latter cases. Terashima et al. (2005) found that variation between gm and Sc values for different functional groups was related to variation in CWT (Terashima et al., 2006; Evans et al., 2009). They further discussed that mesophyll conductance per chloroplast surface area (gm/Sc) depends on CWT (Terashima et al., 2011). Those previous studies used the values of physiological traits (A, gm, Ci, and Cc) and anatomical traits (Sc and CWT) measured by different techniques derived from different species. However, by using treatments to vary gm, our results more clearly demonstrate that the draw-down of CO2 (Ci–Cc; Supplemental Fig. S6) and mesophyll resistance (Sc/gm; Fig. 5) were strongly dependent on CWT (Tosens et al., 2012). The observed CWT in Def plants was close to that of ferns and much greater than that of fast-growing herbaceous species such as rapeseed (Brassica napus), cotton (Gossypium hirsutum), sunflower (Helianthus annuus), and tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum; Gago et al., 2019). Because these values are usually obtained from young leaves of plants grown under optimal conditions, age- and growth-condition–dependent changes in CWT and consequent physiological changes should be considered in future studies.

We should also consider how components of mesophyll resistance (Sc/gm or 1/gm) other than the cell wall will change depending on sink–source imbalance. As the cell wall is only one component of the total mesophyll resistance, we expected positive y-intercepts in the relationships between Sc/gm and CWT (Fig. 6, C and D) and those between 1/gm and CMA relationships (Fig. 7, C and D). However, this was not evident. This may indicate that membrane resistance changed with age or in response to defoliation. Aquaporin is one of the candidate proteins involved in CO2 membrane permeability (Mori et al., 2014; Groszmann et al., 2017). Some studies have reported age-dependent and stress-induced decreases in the expression levels of aquaporins (Regon et al., 2014), which could influence gm. In addition, it is possible that the properties of the cell wall do not simply scale with thickness. For example, wall porosity has not been quantified yet exists as a key parameter linking CWT to permeability. Overall, these results will be of great help for a comprehensive understanding of the discrepant relationships among various traits associated with gm.

Possibility of Flexible Regulation of gm under Field Conditions

A study of oak (Quercus robur) and ash trees (Fraxinus oxyphylla) in a Mediterranean climate reported significant seasonal and yearly dynamics in relative limitation imposed by Rubisco, stomatal resistance, and mesophyll resistance to A that were associated with leaf development, senescence, and severe drought (Grassi and Magnani, 2005). This suggests that photosynthesis may be flexibly regulated not only by biochemical factors and stomatal closure but also by changes in gm. Cell-wall components may flexibly change depending on the sink–source balance, which could contribute to the observed seasonal dynamics under fluctuating environments.

Although cellulose is an immobile carbohydrate, hemicellulose and pectin, which are also cell-wall components, are mobile carbohydrates. Hemicellulose and pectin content change depending on growth CO2 conditions and growth light intensity, suggesting that changes in these mobile cell-wall components could be involved in the regulation of gm (Teng et al., 2006; Schädel et al., 2010). In fact, primary cell walls in expanding leaves of Arabidopsis are composed of ∼14% cellulose, 24% hemicellulose, and 42% pectin (Zablackis et al., 1995). Moreover, pectin and hemicelluloses are substantially reduced by at least 30% in leaves of Arabidopsis suffering from carbon starvation (Lee et al., 2007).

Extracellular polysaccharides act as a microscale barrier to gas diffusion (Ahimou et al., 2007), and the changes in the contents of hemicellulose and pectin, which are also polysaccharides, could alter liquid-phase CO2 diffusivity through the changes in the cell-wall porosity and tortuosity as discussed in Evans et al. (2009). The increase in CMA did not accompany the increase in CWT in Ct plants of French bean at 2 WAD (Fig. 6B), suggesting that hemicellulose and pectin polymers accumulated in the cell-wall region, causing the increased cell-wall density in these plants. Recent studies are revealing that cell-wall properties, such as porosity (Ellsworth et al., 2018), the apoplastic antioxidant system (Clemente-Moreno et al., 2019), and modification of cell-wall components such as cellulose, hemicellulose, and pectin (Roig-Oliver et al., 2020), significantly affect mesophyll conductance in rice (Oryza sativa), Nicotiana sylvestris, and grape vine (Vitis vinifera), respectively. It is worth clarifying how the above factors affect gm in response to changes in sink–source balance and how the flexible regulation of gm could contribute to increasing crop productivity under fluctuating environments.

CONCLUSION

Our comprehensive analyses revealed that cell-wall mass and thickness changed in response to sink–source perturbation, which caused decreases in gm and photosynthesis in soybean and French bean. Meanwhile, variation in starch accumulation had little impact on gm, consistent with our previous study (Mizokami et al., 2019). Further study is needed to reveal the contribution of gm to regulating photosynthetic capacity in plants growing under natural environments where light intensity, temperature, and other environmental factors fluctuate greatly.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials and Growth Conditions

Soybean (Glycine max ‘Williams 82’) and French bean (Phaseolus vulgaris ‘Gourmet Delight’) seeds were sown in 500-mL plastic pots filled with commercial soil (Martins Mix, Martins Fertilizers) and slow release fertilizer (Osmocote Exact Mini, N:P:K = 16:3.5:9.1; Scotts). A quantity of 5 g and 0.625 g of the fertilizer were mixed with the soil for HN and LN conditions, respectively. For each nitrogen condition, ∼40 plants were grown for each species. Accordingly, ∼160 plants were grown in total.

The potted plants were grown in a glass house and were watered daily. During the growth period, average temperature, relative humidity, and atmospheric CO2 concentration recorded by an environmental logger (model no. MCH-383; Lutron) were measured at 23.5°C, 73.5%, and 420.4 μL L−1, respectively. Average PPFD measured with a quantum sensor (model no. S-LIA-M003; Onset Computer) was 22.8 mol m−2 d−1.

Experimental Design

The experimental design was described in Figure 1. At 2 weeks after sowing when two primary leaves were fully expanded and small trifoliate leaves appeared, the first measurements of photosynthetic and anatomical traits were conducted as described below. Ct plants used for the first measurements were called Ct0. After the harvest of Ct0, half of the plants were grown under Ct growth conditions, and trifoliate leaves of the other half of the plants were defoliated (Def) for each nitrogen condition and species as in Sugiura et al. (2019). The second and third measurements were conducted 1 and 2 WAD, respectively. At the second and third measurements, four plants were shaded for 1.5 d to reduce sugars and starch in the primary leaves for each treatment, nitrogen condition, and species. The shaded Ct and De plants received 3% of incident PPFD.

Leaf Gas Exchange Measurements

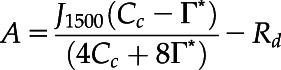

On the measurement days, gas exchange measurements were conducted from early in the morning until noon using two pairs of portable photosynthesis measurement systems (LI-6400XT; Li-Cor BioSciences). At first, CO2 response curves of the primary leaves were determined for each plant using the first pair of LI-6400XTs. The measurements were conducted at a PPFD of 1,500 μmol photons m−2 s−1, ambient CO2 concentration (Ca, μmol mol−1) ranging from 50 to 1,200 μmol mol−1, leaf temperature of 25°C, and O2 concentration of 21% (i.e. ambient O2 concentration). The maximum rate of RuBP carboxylation rate (Vcmax, μmol m−2 s−1) and maximum rate of electron transport driving RuBP regeneration (J1500, μmol m−2 s−1) were calculated by fitting the following equations (Farquhar et al., 1980):

|

|

where Cc is CO2 partial pressure at the chloroplast, Rd is the day respiration, Γ* is the CO2 compensation point in the absence of photorespiration (36.9 μmol mol−1 at 25°C), and O is the partial pressure of O2 (200 μmol mol−1). KC and KO are Michaelis–Menten constants of Rubisco activity for CO2 and O2, respectively. The values assumed for KC and KO were 259 and 179 μmol mol−1, respectively (von Caemmerer et al., 1994). PPFD was reduced to zero just after the measurement of CO2 response curve, and constant leaf respiration rates obtained within 5 min were assumed as Rd (Tazoe et al., 2011). Cc was calculated after the gm measurements as described later, and Vcmax and J1500 were calculated using Cc < 300 μmol mol−1 and > 300 μmol mol−1, respectively.

Concurrent Gas Exchange, Carbon Isotope Discrimination Measurements, and Calculation of Mesophyll Conductance

After the measurements of CO2 response curves, gm was estimated using the second pair of LI-6400XTs with a tunable diode laser (model no. TGA200; Campbell Scientific) as in Evans and von Caemmerer (2013) and Bahar et al. (2018). The measurements were conducted on the same set of leaves at PPFD of 1,500 μmol photons m−2 s−1, Ca of 400 μmol mol−1, leaf temperature of 25°C, and O2 concentration of 2% to suppress photorespiration. Air containing 2% O2 produced by mixing N2 and O2 using mass flow controllers (Omega Engineering) was supplied to both the pair of LI-6400XTs and the tunable diode laser. Mesophyll conductance was calculated as described by Evans and von Caemmerer (2013) where the ternary correction was applied as in Farquhar and Cernusak (2012). After the gm measurements, Cc was estimated as Cc = Ci – A/gm, then Vcmax was calculated using Equation 1 for each leaf (Bahar et al., 2018).

Sampling

After the gas exchange measurements, seven leaf discs (1 cm in diameter) were sampled from the primary leaves. Four discs were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at –80°C for later determination of Rubisco content and cell-wall content. Another three leaf discs were frozen in liquid nitrogen and then oven-dried at 80°C for later determination of LMA (g m−2), leaf nitrogen content, δ13C, and the content of NSCs (starch and soluble sugars).

Light and TEM Analyses

In the evening after the first and third harvests, the small leaf segments were further cut with a razor blade, then immediately immersed in 0.1 m of phosphate buffer at pH 7.0 containing 2.5% (v/v) glutaraldehyde and 2% (v/v) paraformaldehyde, vacuum-infiltrated for 15 min, and stored at 4°C overnight. On the following day, the segments were post-fixed in 1% (v/v) OsO4 for 1 h and dehydrated in an ethanol series. After dehydration, the segments were embedded in LR White resin (London Resin) and polymerized for both light microscopy and TEM analyses. For light microscopy, leaf transverse sections 1-μm-thick were cut on a microtome with a glass knife and stained with Toluidine Blue. Leaf thickness, the surface area of mesophyll cell walls exposed to the intercellular space (Sm, m2 m−2), and the surface area of chloroplasts facing the intercellular space (Sc, m2 m−2) were determined for each plant. Sm and Sc values were calculated for each plant using the curvature correction factor as in Thain (1983) and Evans et al. (1994). The values of the factor ranged from 1.28 to 1.42 in soybean and from 1.28 to 1.45 in French bean.

For TEM, ultrathin sections 70-nm-thick were cut on an ultramicrotome with a glass knife and placed on a 100-mesh copper grid with formvar. The grids were stained with a 2% (v/v) uranyl acetate solution followed by a lead citrate solution. The sections were examined on a transmission electron microscope (HA7100; Hitachi). The wall thickness of mesophyll cells was measured on the ultrathin sections using the software ImageJ (Schneider et al., 2012). The thickness was calculated for randomly selected cells by dividing the cross-sectional area of the cell wall by its length as in Mizokami et al. (2019).

NSCs

Oven-dried leaf discs of 1 cm in diameter were weighed to determine LMA and then ground with a Tissue Lyser II (Qiagen). The ground samples (3–5 mg each) were then used to determine the contents of Glc, Suc, and starch as in Araya et al. (2006). Soluble sugars were extracted with 80% ethanol, and Suc was hydrolyzed to Glc and Fru with an invertase solution (Wako Chemical). The precipitate was treated with amyloglucosidase (cat. no. A-9228; Sigma-Aldrich) to break down starch into Glc. Finally, Glc, and Glc equivalents of Suc and starch, were quantified using a Glc CII Test Kit (Wako Chemicals). The content of sugars and starch were expressed on a leaf-area basis.

Nitrogen and δ13C

The nitrogen content (Nmass, g N g−1) and δ13C of the ground leaf samples was determined with a CN analyzer (Elementar Analyzensysteme; Vario Micro) connected to an isotopic ratio mass spectrometer (model no. 100; IsoPrime). Nitrogen content per area (Narea, g N m−2) was calculated as a product of Nmass and LMA.

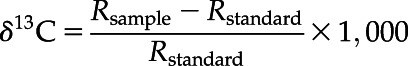

The value δ13C (‰) was calculated as follows:

|

where Rsample and Rstandard are the 13C/12C ratios of the sample and the standard (Pee Dee Belemnite, 0.011180).

Cell Wall

Three or four frozen leaf discs of 1-cm diameter, stored at –80°C, were used to determine the contents of cell-wall materials and the sum of cellulose and hemicellulose, as in Sugiura et al. (2017). After homogenizing the frozen discs with the Tissue Lyser II, the homogenized tissue was heated at 95°C in 1 mL of 20-mm HEPES buffer at pH 7.0 containing 1% SDS to remove soluble proteins. From the residual pellet, starch was removed using amyloglucosidase and the cytoplasmic protein was removed using 1 m of NaCl. The resultant pellet was assumed to contain the cell-wall materials, and the pellet was weighed after drying to calculate CMA (g m−2).

Rubisco Content

One frozen leaf disc of 1-cm diameter, stored at –80°C, was used for the determination of Rubisco active sites by the 14C-CABP binding assay (Ruuska et al., 1998). The frozen leaf disc (1-cm diameter) was ground rapidly using an ice-cold glass homogenizer with 1 mL of CO2-free extraction buffer (25 mm of HEPES at pH 7.8, 1 mm of EDTA, 10 mm of DTT, and 1% [w/v] polyvinylpolypyrrolidone) and 24 μL of the protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). The lysates were immediately transferred to microtubes, and they were centrifuged at 13,000 rpm at 4°C for 30 s. For the determination of total number of active sites, 100 μL of supernatant was transferred to microtubes containing 1.1 μL of 14CPBP, 3.5 μL of 0.5 m NaHCO3, and 1.8 μL of 1 m of MgCl2, and they were incubated at room temperature for 45 min. Rubisco-bound 14C-CABP was collected in glass vials by gel filtration, and the 14C content was measured by a liquid scintillation analyzer (model no. Tri-Carb 2800TR; PerkinElmer) after adding a scintillation cocktail (Ultima Gold XR; PerkinElmer). The total Rubisco content (μmol active sites m–2) was determined from the amount of 14C-CABP-Rubisco in fully activated samples.

Relationships among Cell-Wall–Related Traits

Cell-wall–related morphological and physiological traits were compared to quantify the effect of altered cell-wall mass and thickness on CO2 diffusion. Relationships among the reciprocal of mesophyll conductance, mesophyll resistance (1/gm), and CMA were investigated. Furthermore, because gm is proportional to the surface area available for CO2 diffusion, it was expressed as per-unit chloroplast surface area adjacent to the intercellular airspaces (gm/Sc; Terashima et al., 2011). Mesophyll resistance per Sc (Sc/gm), and the draw-down of CO2 from the intercellular space to the site of carboxylation in the chloroplast (Ci–Cc) were expected to linearly relate to CWT.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical tests were performed using the software Systat13 (Systat Software).

The effects of defoliation and shading on the photosynthetic and anatomical traits were evaluated by two-way ANOVA. Significant differences between Ct and Def plants were determined by Student’s t test for the physiological and morphological characteristics at 1 and 2 WAD and for leaf anatomical traits evaluated by microscopic analysis at 2 WAD.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Photosynthetic characteristics in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S2. Relationships between photosynthetic characteristics in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN and LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S3. Relationships among photosynthetic characteristics, leaf nitrogen content, and Rubisco content in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN and LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S4. Starch content and cell-wall content in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S5. Glc and Suc content in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN and LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S6. Relationships between draw-down of CO2 from the atmosphere to intercellular space (Ca–Ci), from the intercellular space to the chloroplast (Ci–Cc), and CWT in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN and LN conditions.

Supplemental Figure S7. Relationships between δ13C and chloroplast CO2 concentration (Cc) in the primary leaves of soybean and French bean grown under HN and LN conditions.

Supplemental Table S1. Results of two-way ANOVA to evaluate effects of defoliation and shading on the physiological and morphological traits.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nijat Imin for sharing soybean seeds, Soumi Bala for technical assistance with the photosynthesis measurements, Jiwon Lee for light microscopy and TEM, and Dr. Spencer Whitney for help with the 14C-CABP binding assay.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (grant no. 14J07443) and the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for Translational Photosynthesis (grant no. CE140100015).

References

- Ahimou F, Semmens MJ, Haugstad G, Novak PJ(2007) Effect of protein, polysaccharide, and oxygen concentration profiles on biofilm cohesiveness. Appl Environ Microbiol 73: 2905–2910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth A, Rogers A, Nelson R, Long SP(2004) Testing the source-sink hypothesis of down-regulation of photosynthesis in elevated [CO2] in the field with single gene substitutions in Glycine max. Agric Meteorol 122: 85–94 [Google Scholar]

- Araya T, Noguchi K, Terashima I(2006) Effects of carbohydrate accumulation on photosynthesis differ between sink and source leaves of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Plant Cell Physiol 47: 644–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahar NHA, Hayes L, Scafaro AP, Atkin OK, Evans JR(2018) Mesophyll conductance does not contribute to greater photosynthetic rate per unit nitrogen in temperate compared with tropical evergreen wet-forest tree leaves. New Phytol 218: 492–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmo-Silva E, Andralojc PJ, Scales JC, Driever SM, Mead A, Lawson T, Raines CA, Parry MAJ(2017) Phenotyping of field-grown wheat in the UK highlights contribution of light response of photosynthesis and flag leaf longevity to grain yield. J Exp Bot 68: 3473–3486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriquí M, Roig-Oliver M, Brodribb TJ, Coopman R, Gill W, Mark K, Niinemets Ü, Perera-Castro AV, Ribas-Carbó M, Sack L, et al. (2019) Anatomical constraints to nonstomatal diffusion conductance and photosynthesis in lycophytes and bryophytes. New Phytol 222: 1256–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L, Fuchigami LH(2000) Rubisco activation state decreases with increasing nitrogen content in apple leaves. J Exp Bot 51: 1687–1694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemente-Moreno MJ, Gago J, Díaz-Vivancos P, Bernal A, Miedes E, Bresta P, Liakopoulos G, Fernie AR, Hernández JA, Flexas J(2019) The apoplastic antioxidant system and altered cell wall dynamics influence mesophyll conductance and the rate of photosynthesis. Plant J 99: 1031–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellsworth PV, Ellsworth PZ, Koteyeva NK, Cousins AB(2018) Cell wall properties in Oryza sativa influence mesophyll CO2 conductance. New Phytol 219: 66–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, Kaldenhoff R, Genty B, Terashima I(2009) Resistances along the CO2 diffusion pathway inside leaves. J Exp Bot 60: 2235–2248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S(2013) Temperature response of carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance in tobacco. Plant Cell Environ 36: 745–756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans JR, von Caemmerer S, Setchell BA, Hudson GS(1994) The relationship between CO2 transfer conductance and leaf anatomy in transgenic tobacco with a reduced content of Rubisco. Funct Plant Biol 21: 475–495 [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, von Caemmerer S, Berry JA(1980) A biochemical model of photosynthetic CO2 assimilation in leaves of C3 species. Planta 149: 78–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar GD, Cernusak LA(2012) Ternary effects on the gas exchange of isotopologues of carbon dioxide. Plant Cell Environ 35: 1221–1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gago J, Carriquí M, Nadal M, Clemente-Moreno MJ, Coopman RE, Fernie AR, Flexas J(2019) Photosynthesis optimized across land plant phylogeny. Trends Plant Sci 24: 947–958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi G, Magnani F(2005) Stomatal, mesophyll conductance and biochemical limitations to photosynthesis as affected by drought and leaf ontogeny in ash and oak trees. Plant Cell Environ 28: 834–849 [Google Scholar]

- Groszmann M, Osborn HL, Evans JR(2017) Carbon dioxide and water transport through plant aquaporins. Plant Cell Environ 40: 938–961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai M.(2008) Regulation of leaf photosynthetic rate correlating with leaf carbohydrate status and activation state of Rubisco under a variety of photosynthetic source/sink balances. Physiol Plant 134: 216–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krapp A, Stitt M(1995) An evaluation of direct and indirect mechanisms for the “sink-regulation” of photosynthesis in spinach: Changes in gas exchange, carbohydrates, metabolites, enzyme activities and steady-state transcript levels after cold-girdling source leaves. Planta 195: 313–323 [Google Scholar]

- Lee E-J, Matsumura Y, Soga K, Hoson T, Koizumi N(2007) Glycosyl hydrolases of cell wall are induced by sugar starvation in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell Physiol 48: 405–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loreto F, Di Marco G, Tricoli D, Sharkey TD(1994) Measurements of mesophyll conductance, photosynthetic electron transport and alternative electron sinks of field grown wheat leaves. Photosynth Res 41: 397–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormick AJ, Cramer MD, Watt DA(2008) Differential expression of genes in the leaves of sugarcane in response to sugar accumulation. Trop Plant Biol 1: 142–158 [Google Scholar]

- Miyazawa SI, Makino A, Terashima I(2003) Changes in mesophyll anatomy and sink-source relationships during leaf development in Quercus glauca, an evergreen tree showing delayed leaf greening. Plant Cell Environ 26: 745–755 [Google Scholar]

- Mizokami Y, Sugiura D, Watanabe CKA, Betsuyaku E, Inada N, Terashima I(2019) Elevated CO2-induced changes in mesophyll conductance and anatomical traits in wild type and carbohydrate-metabolism mutants of Arabidopsis thaliana. J Exp Bot 70: 4807–4818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori IC, Rhee J, Shibasaka M, Sasano S, Kaneko T, Horie T, Katsuhara M(2014) CO2 transport by PIP2 aquaporins of barley. Plant Cell Physiol 55: 251–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nabeshima E, Murakami M, Hiura T(2001) Effects of herbivory and light conditions on induced defense in Quercus crispula. J Plant Res 114: 403–409 [Google Scholar]

- Nafziger ED, Koller HR(1976) Influence of leaf starch concentration on CO2 assimilation in soybean. Plant Physiol 57: 560–563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano H, Muramatsu S, Makino A, Mae T(2000) Relationship between the suppression of photosynthesis and starch accumulation in the pod-removed bean. Funct Plant Biol 27: 167–173 [Google Scholar]

- Neilson EH, Goodger JQD, Woodrow IE, Møller BL(2013) Plant chemical defense: At what cost? Trends Plant Sci 18: 250–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peguero-Pina JJ, Sisó S, Flexas J, Galmés J, García-Nogales A, Niinemets Ü, Sancho-Knapik D, Saz MÁ, Gil-Pelegrín E(2017) Cell-level anatomical characteristics explain high mesophyll conductance and photosynthetic capacity in sclerophyllous Mediterranean oaks. New Phytol 214: 585–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoda Y, Wright IJ, Evans JR, Hikosaka K, Kitajima K, Niinemets Ü, Poorter H, Tosens T, Westoby M(2017) Physiological and structural tradeoffs underlying the leaf economics spectrum. New Phytol 214: 1447–1463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regon P, Panda P, Kshetrimayum E, Panda SK(2014) Genome-wide comparative analysis of tonoplast intrinsic protein (TIP) genes in plants. Funct Integr Genomics 14: 617–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roig-Oliver M, Nadal M, Clemente-Moreno MJ, Bota J, Flexas J(2020) Cell wall components regulate photosynthesis and leaf water relations of Vitis vinifera cv. Grenache acclimated to contrasting environmental conditions. J Plant Physiol 244: 153084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruuska S, Andrews TJ, Badger MR, Hudson GS, Laisk A, Price GD, von Caemmerer S(1998) The interplay between limiting processes in C3 photosynthesis studied by rapid-response gas exchange using transgenic tobacco impaired in photosynthesis. Funct Plant Biol 25: 859–870 [Google Scholar]

- Sawada S, Kuninaka M, Watanabe K, Sato A, Kawamura H, Komine K, Sakamoto T, Kasai M(2001) The mechanism to suppress photosynthesis through end-product inhibition in single-rooted soybean leaves during acclimation to CO2 enrichment. Plant Cell Physiol 42: 1093–1102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schädel C, Richter A, Blöchl A, Hoch G(2010) Hemicellulose concentration and composition in plant cell walls under extreme carbon source-sink imbalances. Physiol Plant 139: 241–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW(2012) NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671–675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheen J.(1994) Feedback control of gene expression. Photosynth Res 39: 427–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimakawa G, Suzuki M, Yamamoto E, Saito R, Iwamoto T, Nishi A, Miyake C(2014) Why don’t plants have diabetes? Systems for scavenging reactive carbonyls in photosynthetic organisms. Biochem Soc Trans 42: 543–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Pérez V, De Faveri J, Molero G, Deery DM, Condon AG, Reynolds MP, Evans JR, Furbank RT(2020) Genetic variation for photosynthetic capacity and efficiency in spring wheat. J Exp Bot 71: 2299–2311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura D, Betsuyaku E, Terashima I(2015) Manipulation of the hypocotyl sink activity by reciprocal grafting of two Raphanus sativus varieties: Its effects on morphological and physiological traits of source leaves and whole-plant growth. Plant Cell Environ 38: 2629–2640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura D, Betsuyaku E, Terashima I(2019) Interspecific differences in how sink-source imbalance causes photosynthetic downregulation among three legume species. Ann Bot 123: 715–726 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura D, Kojima M, Sakakibara H(2016) Phytohormonal regulation of biomass allocation and morphological and physiological traits of leaves in response to environmental changes in Polygonum cuspidatum. Front Plant Sci 7: 1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiura D, Watanabe CKA, Betsuyaku E, Terashima I(2017) Sink-source balance and down-regulation of photosynthesis in Raphanus sativus: Effects of grafting, N and CO2. Plant Cell Physiol 58: 2043–2056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tazoe Y, von Caemmerer S, Estavillo GM, Evans JR(2011) Using tunable diode laser spectroscopy to measure carbon isotope discrimination and mesophyll conductance to CO2 diffusion dynamically at different CO2 concentrations. Plant Cell Environ 34: 580–591 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teng N, Wang J, Chen T, Wu X, Wang Y, Lin J(2006) Elevated CO2 induces physiological, biochemical and structural changes in leaves of Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol 172: 92–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Araya T, Miyazawa S, Sone K, Yano S(2005) Construction and maintenance of the optimal photosynthetic systems of the leaf, herbaceous plant and tree: An eco-developmental treatise. Ann Bot 95: 507–519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tazoe Y, Vyas P, Yano S(2006) Irradiance and phenotype: Comparative eco-development of sun and shade leaves in relation to photosynthetic CO2 diffusion. J Exp Bot 57: 343–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terashima I, Hanba YT, Tholen D, Niinemets Ü(2011) Leaf functional anatomy in relation to photosynthesis. Plant Physiol 155: 108–116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thain JF.(1983) Curvature correction factors in the measurement of cell surface areas in plant tissues. J Exp Bot 34: 87–94 [Google Scholar]

- Tholen D, Boom C, Noguchi K, Ueda S, Katase T, Terashima I(2008) The chloroplast avoidance response decreases internal conductance to CO2 diffusion in Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Plant Cell Environ 31: 1688–1700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomás M, Flexas J, Copolovici L, Galmés J, Hallik L, Medrano H, Ribas-Carbó M, Tosens T, Vislap V, Niinemets Ü(2013) Importance of leaf anatomy in determining mesophyll diffusion conductance to CO2 across species: Quantitative limitations and scaling up by models. J Exp Bot 64: 2269–2281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosens T, Niinemets U, Vislap V, Eichelmann H, Castro Díez P(2012) Developmental changes in mesophyll diffusion conductance and photosynthetic capacity under different light and water availabilities in Populus tremula: How structure constrains function. Plant Cell Environ 35: 839–856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tosens T, Nishida K, Gago J, Coopman RE, Cabrera HM, Carriquí M, Laanisto L, Morales L, Nadal M, Rojas R, et al. (2016) The photosynthetic capacity in 35 ferns and fern allies: Mesophyll CO2 diffusion as a key trait. New Phytol 209: 1576–1590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turnbull TL, Adams MA, Warren CR(2007) Increased photosynthesis following partial defoliation of field-grown Eucalyptus globulus seedlings is not caused by increased leaf nitrogen. Tree Physiol 27: 1481–1492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veromann-Jürgenson LL, Tosens T, Laanisto L, Niinemets Ü(2017) Extremely thick cell walls and low mesophyll conductance: Welcome to the world of ancient living!. J Exp Bot 68: 1639–1653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vlcková A, Spundová M, Kotabová E, Novotný R, Dolezal K, Naus J(2006) Protective cytokinin action switches to damaging during senescence of detached wheat leaves in continuous light. Physiol Plant 126: 257–267 [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Evans JR, Hudson GS, Andrews TJ(1994) The kinetics of ribulose-1, 5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase in vivo inferred from measurements of photosynthesis in leaves of transgenic tobacco. Planta 195: 88–97 [Google Scholar]

- von Caemmerer S, Farquhar GD(1984) Effects of partial defoliation, changes of irradiance during growth, short-term water stress and growth at enhanced p(CO2) on the photosynthetic capacity of leaves of Phaseolus vulgaris L. Planta 160: 320–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamori W.(2016) Photosynthetic response to fluctuating environments and photoprotective strategies under abiotic stress. J Plant Res 129: 379–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zablackis E, Huang J, Müller B, Darvill AG, Albersheim P(1995) Characterization of the cell-wall polysaccharides of Arabidopsis thaliana leaves. Plant Physiol 107: 1129–1138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]