Two SUN domain proteins have partially redundant functions in the regulation of telomere clustering, homologous pairing, and crossover formation during rice meiosis.

Abstract

During meiosis, Sad1/UNC-84 (SUN) domain proteins play conserved roles in promoting telomere bouquet formation and homologous pairing across species. Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 have been shown to have overlapping functions in meiosis. However, the role of SUN proteins in rice (Oryza sativa) meiosis and the extent of functional redundancy between them remain elusive. Here, we generated single and double mutants of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in rice using genome editing. The Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant showed severe defects in telomere clustering, homologous pairing, and crossover formation, suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are essential for rice meiosis. When introducing a mutant allele of O. sativa SPORULATION11-1 (OsSPO11-1), which encodes a topoisomerase initiating homologous recombination, into the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant, we observed a combined Osspo11-1- and Ossun1 Ossun2-like phenotype, demonstrating that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 promote bouquet formation independent of OsSPO11-1 but regulate pairing and crossover formation downstream of OsSPO11-1. Importantly, the Ossun1 single mutant had a normal phenotype, but meiosis was disrupted in the Ossun2 mutant, indicating that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are not completely redundant in rice. Further analyses revealed a genetic dosage-dependent effect and an evolutionary differentiation between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2. These results suggested that OsSUN2 plays a more critical role than OsSUN1 in rice meiosis. Taken together, this work reveals the essential but partially redundant roles of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in rice meiosis and demonstrates that functional divergence of SUN proteins has taken place during evolution.

During early prophase I of meiosis, homologous chromosomes recognize and pair with each other and then achieve full synapsis along their entire length. The pairing of homologous chromosomes is a vital event for proper meiotic recombination and accurate chromosome segregation (Scherthan, 2001). Dynamic chromosome movements occur accompanying pairing and involve polarized nuclear reorganization of chromosomes mediated by cytoskeleton proteins (Zickler and Kleckner, 1998). In detail, the ends of the chromosomes, the telomeres, attach to the nuclear envelope (NE) and then transiently cluster within a limited region of the NE to form a characteristic “bouquet” arrangement that is associated with the onset of pairing (Scherthan, 2001; Harper et al., 2004). The telomere bouquet is an evolutionarily conserved meiotic configuration among eukaryotes and is speculated to facilitate efficient homologous chromosome pairing by bringing distant chromosomes into close proximity (Scherthan, 2001; Harper et al., 2004).

In recent years, extensive genetic analyses in yeasts and mammals have led to the identification of a number of proteins that are involved in telomere clustering. A prerequisite for clustering is the attachment of telomeres to the NE, where “linker” proteins connect telomere-binding proteins with inner nuclear membrane (INM) proteins. For example, bouquet1 (Bqt1), Bqt2, Bqt3, and Bqt4 in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) form bridges between chromosomes and the NE and anchor telomeres to the spindle-pole body to ensure chromosomal bouquet formation (Chikashige et al., 2006, 2009). Nondisjunction1 (Ndj1) in budding yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae; Conrad et al., 1997; Trelles-Sticken et al., 2000), telomere repeat binding bouquet formation protein1 (TERB1), TERB2, and membrane-anchored junction protein in mice (Mus musculus; Shibuya et al., 2014, 2015) also have similar functions in the process of telomere attachment to the INM. Moreover, several meiosis-related molecules also play important roles in regulating the connection between telomeres and the INM, such as cyclin-dependent kinase2 (CDK2) and its activator Speedy/RINGO A (rapid inducer of G2/M progression in oocytes; Viera et al., 2015; Mikolcevic et al., 2016; Tu et al., 2017).

In addition to these “linker” proteins, the transmembrane LINC (linker of nucleoskeleton and cytoskeleton) complex also plays an essential role in telomere clustering (Ding et al., 2007; Yoshida et al., 2013). This complex consists of two proteins: Sad1/UNC-84 homology (SUN) in the INM and Klarsicht/ANC-1/Syne homology (KASH) in the outer nuclear membrane. The C-terminal region of SUN protein contains a conserved SUN domain that is located in the nuclear periplasm, where it interacts with the conserved KASH domain of the KASH protein. The N-terminal nucleoplasmic region of the SUN protein is associated with telomere-binding proteins, whereas the N terminus of the KASH protein protrudes into the cytoplasm, where it interacts with elements of the cytoskeleton (Morimoto et al., 2012; Horn et al., 2013). Thus, the LINC complex forms a structural bridge connecting chromosomes to the cytoskeleton and transduces forces generated in the cytoplasm to chromosomes to drive their movements (Starr and Fridolfsson, 2010).

SUN proteins are conserved across eukaryotes, including fungi, plants, and animals and share common features, such as a transmembrane domain that enables NE localization and a SUN domain that recruits KASH proteins in the perinuclear space (Starr and Fridolfsson, 2010). However, the nucleoplasmic domains of SUN proteins are not conserved, and many organisms have multiple SUN proteins with different expression patterns during development. Therefore, the functions of different SUN proteins vary in the same species, and even the same SUN protein may have different functions at different stages of development. For example, the SUN proteins Sad1 in fission yeast and UNC-84 in Caenorhabditis elegans were initially identified to be required for nuclear migration and positioning (Malone et al., 1999; Tran et al., 2001). Then, the meiotic function of SUN proteins was dissected in fission yeast through the major discovery of meiosis-specific Bqt1 and Bqt2, which connect Sad1 and Repressor/activator protein1 (Rap1, a telomere binding protein; Chikashige et al., 2006). In mammals, there are several SUN proteins, including UNC-84A (SUN1), UNC-84B (SUN2), SUN3, Sperm-associated antigen4 (SPAG4), and SPAG4L, and functional divergence of these SUN proteins has also been observed (Göb et al., 2010; Jiang et al., 2011). The role of mammalian SUN proteins in meiotic telomere clustering was first detected by targeted disruption of the mouse SUN1 gene, which resulted in complete sterility and severe defects in telomere NE attachment, homologous pairing, and recombination (Ding et al., 2007).

In plants, evidence suggests that there are two divergent classes of SUN proteins: the canonical C-terminal SUN-domain (CCSD) proteins and the plant-prevalent mid-SUN3 transmembrane (PM3) proteins, which have a SUN domain in the central region (Murphy et al., 2010; Graumann et al., 2014). The meiotic functions of both groups of SUN proteins have been characterized. For example, ZmSUN3, encoding a PM3-type SUN protein in maize (Zea mays), has been hypothesized to be the gene disrupted in the dy mutant, which is defective in homologous chromosome synapsis, recombination, telomere-NE interactions, and chromosome segregation (Murphy and Bass, 2012). In addition, a maize CCSD-type SUN protein, ZmSUN2, was shown to have dynamic NE localization during meiosis, and a zygotene-stage half-belt structure of ZmSUN2 was associated with the telomere cluster at the same side of the nucleus (Murphy et al., 2014). AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 are classical C-terminal SUN proteins that were identified to be orthologs of the C. elegans SUN protein UNC-84 in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana). They are consistently expressed in various tissues and show NE localization (Graumann et al., 2010), suggesting that they may have redundant functions in development. This hypothesis was then verified by the analysis of both AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 gene knockdowns, which showed defects in polarized nuclear shape in root hairs (Oda and Fukuda, 2011). Furthermore, Varas et al. (2015) revealed the overlapping functions of AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 in Arabidopsis meiosis. The double mutant Atsun1-1 Atsun2-2 displayed reduced fertility and severe meiotic defects: a delay in the progression of meiosis, an absence of full synapsis, the presence of unresolved interlock-like structures, and a reduction in chiasma frequency. In rice (Oryza sativa), there are four SUN proteins, among which OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are closely related to AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 (Murphy et al., 2010). However, whether they play redundant roles in rice has not yet been confirmed, and their functions in meiosis remain to be explored.

Here, we generated single and double mutants of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 using the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)/CRISPR-associated protein9 (Cas9) genome-editing approach. Cytological analyses of the double mutant revealed severe defects in telomere clustering, homologous pairing, and crossover (CO) formation. Importantly, we discovered normal meiotic progression in the Ossun1 single mutant but disrupted meiosis in the Ossun2 mutant, demonstrating that OsSUN2 plays a more critical role than OsSUN1 in rice meiosis. Furthermore, the finding of a dosage-dependent effect in genetic analyses, together with the results of phylogenetic analyses, all supported the hypothesis that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 play partially redundant roles in rice meiosis. This finding is quite different from that in Arabidopsis and suggests that functional divergence of SUN proteins occurred during evolution.

RESULTS

Identification of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2

To identify putative SUN domain proteins in rice, BLAST searches were performed using the amino acid sequences of Arabidopsis AtSUN1 and AtSUN2. According to the results, two candidate proteins, independently encoded by Os05g0270200 and Os01g0267600, share the highest similarity with AtSUN1 and AtSUN2. Thus, they were designated OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, respectively. Using the protein sequences as queries, SMART searches were performed to identify conserved domains in OsSUN1 and OsSUN2. These searches revealed a C-terminal SUN domain, a central coiled-coil motif, and an N-terminal transmembrane region in each protein (Fig. 1A). Multiple sequence alignments of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 with their orthologs revealed that they were highly conserved within the SUN domain (Supplemental Fig. S1), indicating that they may share similar functions in meiosis as their orthologs. Moreover, OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 showed sequence similarity with 45% amino acid sequence identity (Supplemental Fig. S2A). In contrast, AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 displayed a much higher sequence similarity, with 69% amino acid sequence identity (Supplemental Fig. S2B). These data suggest that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 may have some differences with their Arabidopsis counterparts.

Figure 1.

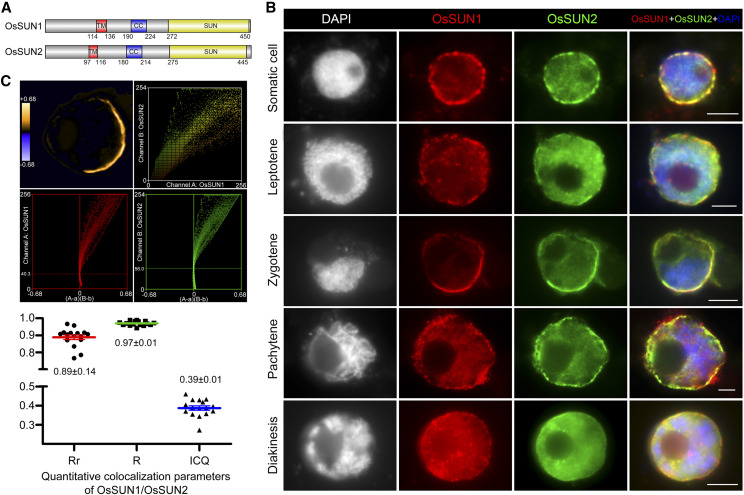

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are colocalized on the nuclear envelope. A, Protein domains of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2. Each protein contains a C-terminal SUN domain (SUN, yellow), a central coiled-coil motif (CC, blue), and an N-terminal transmembrane region (TM, red). B, The loading pattern of OsSUN1 (red) and OsSUN2 (green) in wild-type somatic cells and PMCs. Chromosomes were stained with DAPI (white or blue). Bars = 5 µm. C, Quantitative colocalization analysis of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in meiocytes of mixed stages from leptotene to diakinesis. The outputted images of a zygotene meiocyte were shown as an example. The first image shows the PDM (product of the differences from the mean) map, with orange pixels representing positive PDM values and purple pixels representing negative PDM values. The second image shows the respective intensity scatter plots of two channels. The middle two pictures show plots of signal intensity in the respective channels versus PDM. The bottom displays the statistical data of the parameters Pearson’s correlation coefficient (Rr), Mander’s overlap coefficient (R), and intensity correlation quotient (ICQ) of these meiocytes. Values are means ± sem, n = 16.

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 Are Colocalized on the NE

To define the spatial and temporal distributions of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, OsSUN1-GFP and OsSUN2-GFP fusion proteins were transiently expressed in rice protoplasts. Both OsSUN1-GFP and OsSUN2-GFP were detected as ring-like signals around the nucleus (Supplemental Fig. S3), suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 may be associated with the NE. To confirm this, a rabbit polyclonal antibody against OsSUN1 and a mouse polyclonal antibody against OsSUN2 were prepared for immunofluorescence assays. OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 were both localized on the NE in somatic cells and pollen mother cells (PMCs), which were distinguished according to the morphology of 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI)-stained chromosomes (Fig. 1B). During meiosis, the NE-associated signals of both SUN proteins changed along with meiotic progression. At leptotene, the proteins were uniformly localized on the NE. Upon entering into zygotene, they were gathered on one side of the NE, with the clustered chromosomes located on the same side of the nucleus. Thereafter, the polarized enrichment of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 gradually dispersed, and they were redistributed uniformly until NE breakdown. The association between chromosome clustering and polarized localization of SUN proteins indicated that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 may have roles in promoting chromosomal movement during meiosis.

To establish the relationship between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, the colocalization of these proteins was examined in the wild type, which revealed a high degree of overlap between these two proteins (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, quantitative colocalization analyses were performed in meiocytes of mixed stages from leptotene to diakinesis, and the parameters Rr, R, and ICQ were determined (Fig. 1C). Rr is the Pearson’s correlation coefficient ranging from 1 to −1, and a value close to 1 indicates reliable colocalization; R is Mander’s overlap coefficient, and it ranges between 1 and 0, with 1 being high colocalization, zero being low; ICQ is the intensity correlation quotient distributed between −0.5 and 0.5, and 0 < ICQ ≤ 0.5 indicates dependent staining of two channels. The results showed that the mean values of Rr, R, and ICQ were 0.89 ± 0.14, 0.97 ± 0.01, and 0.39 ± 0.01 (n = 16), respectively, all indicating that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 were highly colocalized.

Targeted Disruption of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 by CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing

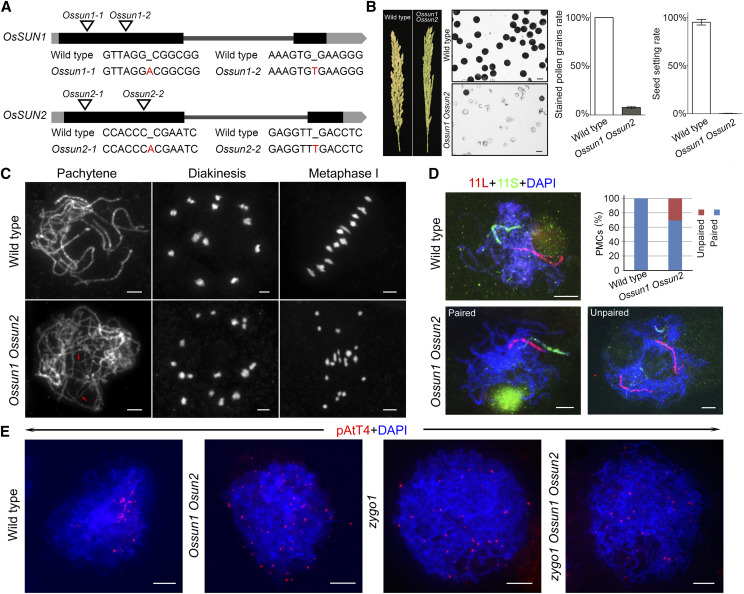

The cDNA sequences of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 were obtained by reverse transcription PCR and rapid amplification of cDNA ends PCR using gene-specific primers. Both genes have two exons and one intron, with a 1362-bp and a 1368-bp coding sequence (CDS), respectively (Fig. 2A). To clarify the function of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in meiosis, a double mutant was generated using the CRISPR-Cas9 method. In one transgenic line, we detected an A insertion at the 90-bp position in OsSUN1 and an A insertion at the 160-bp position in OsSUN2, both leading to frameshifts and premature termination of translation (Fig. 2A). This double mutant was designated Ossun1-1 Ossun2-1. Then, the corresponding Ossun1-1 and Ossun2-1 single mutants were also obtained from the progeny of a double-heterozygous mutant plant. The Ossun1-1 Ossun2-1 double mutant displayed normal vegetative growth but reduced fertility, with only a 0.2% seed-setting rate (Fig. 2B). Cytological observation of anthers stained with 1% I2-KI showed that about 91.8% of pollen grains were shrunken and inviable (Fig. 2B). To confirm that these defects were indeed the result of the loss of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, one additional double mutant (Ossun1-2 Ossun2-2) was generated using the same method, and this mutant mimicked the phenotype of Ossun1-1 Ossun2-1 (Supplemental Fig. S4).

Figure 2.

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 regulate homologous pairing and telomere clustering in rice meiosis. A, Gene structure of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2. Exons, introns, and untranslated regions are shown as black blocks, dark gray lines, and gray boxes, respectively. Mutation sites in OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are indicated in red. B, Comparison of phenotypes of the wild type and the Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant. Bars = 50 µm. Histograms of seed-setting rate (means ± sem, n = 3) and the percentage of stained pollen grains (means ± sem, n = 16) are shown beside. C, Meiotic chromosome behavior in wild type and Ossun1 Ossun2. Some unpaired chromosomes in Ossun1 Ossun2 are indicated with red arrows. Bars = 5 µm. D, The pairing status of homologous chromosomes in wild type and Ossun1 Ossun2. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assays were conducted with two probes, one specific to the short arm (11S, green) of chromosome 11 and one specific to the long arm (11L, red). Chromosomes were stained with DAPI (blue). Bars = 5 µm. The percentage of PMCs with paired or unpaired chromosome 11 is shown as a histogram. E, Detection of bouquet formation in wild type, Ossun1 Ossun2, zygo1, and the zygo1 Ossun1 Ossun2 triple mutant. FISH analyses were performed using the telomere-specific probe pAtT4 (red dots). Bars = 5 µm.

The Conserved Role of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in Homologous Pairing and Telomere Bouquet Formation

To investigate the reason for sterility in the Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant, we analyzed the meiotic chromosomal behavior of PMCs at different stages. Meiotic defects of the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant became apparent at pachytene (Fig. 2C), when no fully synapsed chromosomes were observed. Instead, some chromosomes were partially aligned, and some remained as single threads (Fig. 2C, arrows). Subsequently, a mixture of bivalents and univalents were detected at diakinesis and metaphase I, leading to unequal separation of chromosomes and finally the formation of sterile gametes in the double mutant. To ensure that PMCs at the same meiotic stage were compared in wild type and Ossun1 Ossun2 plants, we correlated meiotic stages with the length of spikelets according to the chromatin appearance as well as the pattern of Human enhancer of invasion10 (HEI10) foci in the PMCs of each spikelet (Supplemental Fig. S5). Our results showed that the length of spikelets was comparable in wild-type and Ossun1 Ossun2 plants from leptotene to late zygotene (P > 0.05). However, the length of pachytene-stage spikelets showed a considerable variation (from 3.3 to 4.2 mm) compared with the wild type (from 3.3 to 3.6 mm), suggesting a significant extension of the duration of pachytene meiocytes in the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant.

To further monitor the pairing status of homologous chromosomes, FISH assays were conducted using two probes, one specific to the short arm of chromosome 11 and one specific to the long arm (Fig. 2D). In the wild type, fully paired signals corresponding to these two probes were observed in all PMCs at pachytene (n = 88). In the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant, however, 30.7% of PMCs (n = 88) displayed unpaired probe signals. Next, the synaptonemal complex assembly was investigated by immunofluorescence analysis using antibodies against the transverse filament protein of synaptonemal complex (ZEP1), homologous pairing aberration in rice meiosis2 (PAIR2), and PAIR3; discontinuous loading of ZEP1 was detected in about 93.9% of Ossun1 Ossun2 PMCs (n = 49) at pachytene or late pachytene (Supplemental Fig. S6). Together, these results suggested that loss of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 disrupted the full-length alignment of homologous chromosomes.

Considering the known role of SUN proteins in telomere clustering, we suspected that defects in homologous pairing were closely related to the absence of a telomere bouquet. To confirm this, FISH analyses were performed using a telomere-specific probe (pAtT4) to detect the telomere bouquet. In all wild-type PMCs (n = 40), telomeres were clustered within a confined region on the chromosomal mass at zygotene (Fig. 2E). In contrast, telomere signals were still scattered over the nuclei in about 96.8% of Ossun1 Ossun2 PMCs (n = 31) at the same stage, indicating the failure to form a bouquet. As ZYGOTENE 1 (ZYGO1) plays an essential role in telomere clustering and homologous pairing in rice, we introduced the zygo1 mutation into the Ossun1 Ossun2 background. The triple mutant displayed a similar phenotype of pAtT4 distribution with that of the Ossun1 Ossun2 and zygo1 mutants, suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 have a similar function with ZYGO1 in regulating telomere clustering. Our data indicated that SUN proteins play conserved roles in promoting telomere clustering and homologous pairing in rice.

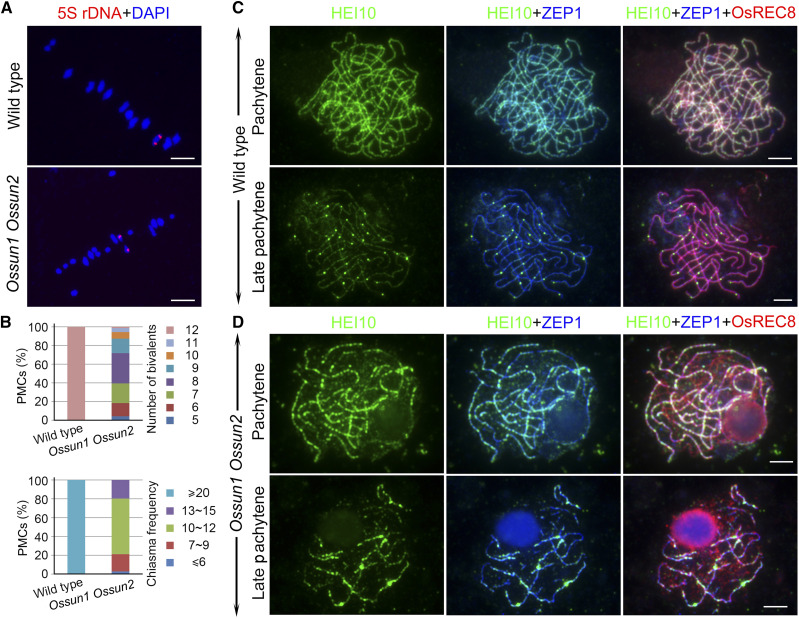

Loss of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 Leads to Reduced CO Level

To investigate whether bivalent formation was affected in the double mutant, we performed FISH assays using a probe against 5S ribosomal DNA (rDNA), which is located on the short arm of chromosome 11. In contrast to the wild type, two 5S rDNA foci, located on separated univalents, were observed in most meiocytes of the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant (88.4%, n = 43; Fig. 3A). The observation of univalents in Ossun1 Ossun2 prompted us to quantify the number of bivalents and chiasma frequency (Fig. 3B). The number of chiasmata in all wild-type PMCs was ≥ 20, corresponding to 12 bivalents per cell (n = 71). However, the chiasma frequency displayed considerable variation and was significantly reduced in Ossun1 Ossun2 PMCs; 2.8%, 18.3%, 59.2%, and 19.7% of PMCs had ≤6, 7 to 9, 10 to 12, and 13 to 15 chiasma, respectively (n = 71). The number of bivalents varied from 5 to 12, and 32.4% of PMCs had eight bivalents, and only 1.4% of PMCs had 12 bivalents. This result suggested that CO formation was severely affected in the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant. To explore whether this resulted from the reduction of double strand breaks (DSBs), we monitored the level of DSBs in both the wild type and the double mutant using an antibody against histone H2AX phosphorylation (γH2AX). We observed the same level of γH2AX foci in the wild type (214.9 ± 5.6, n = 15) and Ossun1 Ossun2 (209.9 ± 6.8, n = 15; P = 0.46; Supplemental Fig. S7A), suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are dispensable for DSB formation. Immunodetection of O. sativa disrupted meiotic cDNA1 (OsDMC1), a meiosis-specific recombinase involved in single-end invasion during recombination, was also performed. In the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant, this protein displayed normal punctate foci at zygotene (270.9 ± 6.9, n = 17), which is indistinguishable from its localization pattern in the wild type (285.9 ± 7.9, n = 16; P = 0.70; Supplemental Fig. S7B). Together, these data indicated that the reduced number of COs in the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant is not caused by defects in early recombination events.

Figure 3.

Loss of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 leads to reduced CO level. A, The distribution of 5S rDNA foci (red) revealed by FISH assays in wild type and Ossun1 Ossun2. Chromosomes at metaphase I were stained with DAPI (blue). B, Quantification of the number of bivalents and chiasma in wild type and Ossun1 Ossun2. C and D, Triple-immunolocalization of OsREC8 (red), HEI10 (green), and ZEP1 (blue) in wild type (C) and Ossun1 Ossun2 (D). Bright punctate signals of HEI10 were restricted to short stretches of ZEP1 in Ossun1 Ossun2. Bars = 5 µm.

We next investigated the loading of OsZIP4, a ZMM (for Zip1, Zip2, Zip3, Zip4, Msh4, Msh5, and Mer3) member required for the formation of class I COs, in the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant (318.2 ± 9.8, n = 17) and found that the loading of this protein was not significantly different from that in the wild type (313.6 ± 7.8, n = 17; P = 0.39; Supplemental Fig. S7C). This result indicated that SUN deficiency has no effect on the process of CO designation. Therefore, we hypothesized that the reduction in the number of COs may result from defects in CO maturation. To test this, we carried out coimmunolocalization of ZEP1 and HEI10 in both wild type and Ossun1 Ossun2 plants. In the wild type, small HEI10 foci stretched along entire chromosomes and colocalized well with linear signals of ZEP1 at pachytene (Fig. 3C). Thereafter, large HEI10 foci appeared on its faint linear foci at late pachytene, which are regarded to indicate the maturation sites of class I COs (Wang et al., 2012). In the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant, however, the linear array and large foci of HEI10 signals were only found on discontinuous ZEP1 stretches (Fig. 3D). Collectively, these results provided evidence that the loss of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 has no effect on early recombination events including CO designation, but disrupts the process of CO maturation, which relies on the normal chromosome alignment and synapsis.

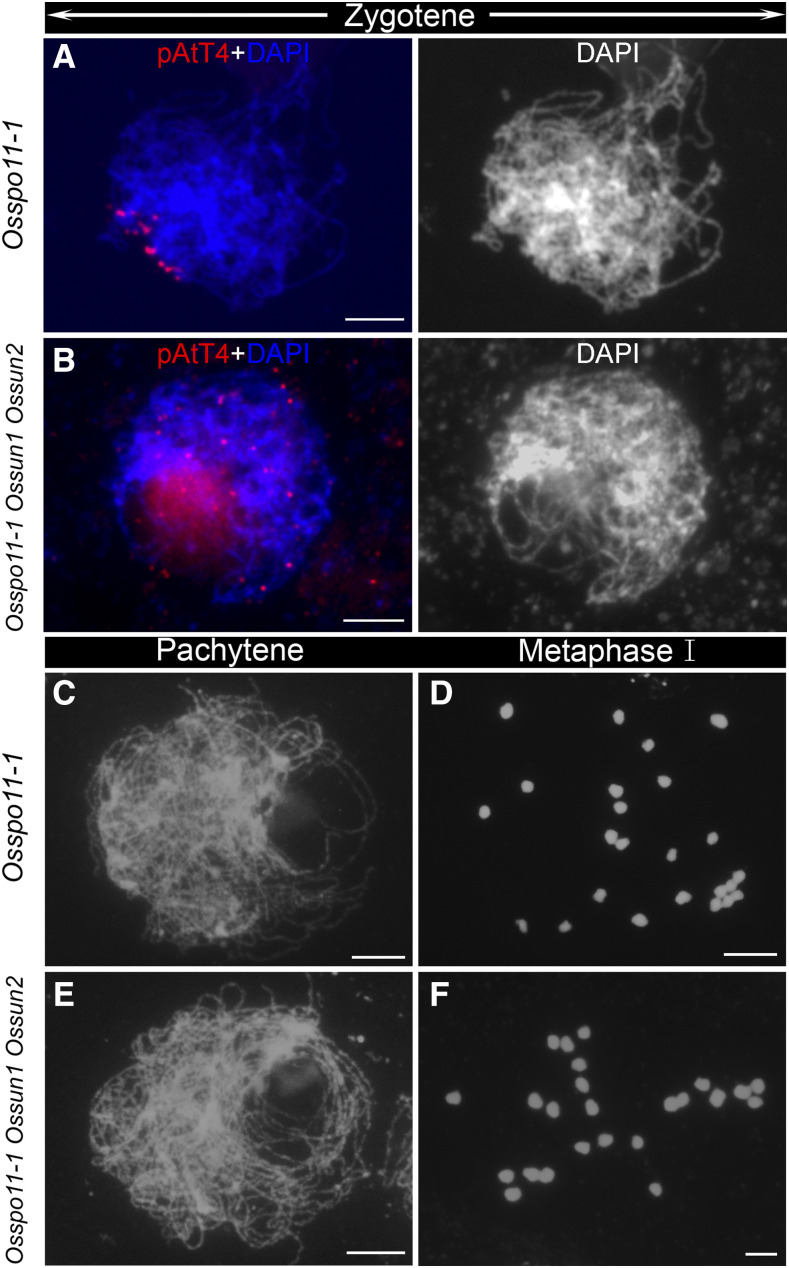

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 Promote Bouquet Formation Independent of OsSPO11-1 but Facilitate Pairing and CO Formation Downstream of OsSPO11-1

To clarify the relationship between telomere clustering and recombination, we constructed the Osspo11-1 Ossun1 Ossun2 triple mutant. O. sativa SPORULATION11-1 (OsSPO11-1) is one of the rice homologs of SPO11, a conserved topoisomerase that initiates homologous recombination (Yu et al., 2010). In the Osspo11-1 single mutant, a telomere bouquet was observed on the chromosome mass at zygotene (Fig. 4A), suggesting that telomere clustering is independent of DSB formation. At pachytene, chromosomes remained as single threads and no pairing was observed (Fig. 4C). Subsequently, 24 univalents were clearly observed at metaphase I (Fig. 4D). These observations demonstrated that homologous pairing and CO formation were completely abolished in the Osspo11-1 mutant. In contrast, a telomere bouquet was not detected in the Osspo11-1 Ossun1 Ossun2 triple mutant at zygotene (Fig. 4B), indicating that OsSUN1 together with OsSUN2 is a prerequisite for telomere clustering in Osspo11-1. At pachytene and metaphase I, the triple mutant showed a typical Osspo11-1 phenotype: no pairing and 24 univalents (Fig. 4, E and F). Taken together, the role of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in bouquet formation is independent of OsSPO11-1, but their roles in homologous pairing and CO formation are genetically downstream of OsSPO11-1.

Figure 4.

The triple mutant Osspo11-1 Ossun1 Ossun2 displayed a combination of the phenotypes of Osspo11-1 and Ossun1 Ossun2. A and B, Telomere behavior was investigated by performing FISH assays using pAtT4 as a probe (red) in Osspo11-1 (A) and Osspo11-1 Ossun1 Ossun2 (B). Chromosomes at zygotene were stained with DAPI (blue or white). C to F, PMCs at pachytene and metaphase I in Osspo11-1 (C and D) and Osspo11-1 Ossun1 Ossun2 (E and F). Bars = 5 µm.

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 Have Partially Redundant Roles in Rice Meiosis

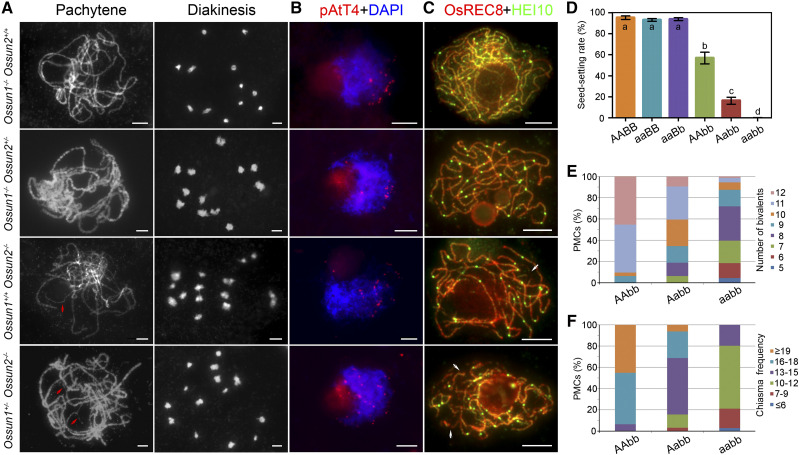

AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 are thought to play completely redundant roles in Arabidopsis meiosis because the Atsun1 and Atsun2 single mutants exhibit complete fertility and normal meiotic progression (Varas et al., 2015). To determine whether OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are functionally redundant, the phenotypes of Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+, Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/−, Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/−, and Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/−, which segregated from Ossun1+/− Ossun2+/−, were analyzed. Compared with the wild type, Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+ and Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/− showed normal fertility and meiotic chromosomal behavior, respectively, with a seed-setting rate of 93.1% ± 1.3% (P = 0.36) and 93.8% ± 1.4% (P = 0.73), respectively (Fig. 5, A–D). However, Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/− and Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/− displayed significantly reduced fertility, with a seed-setting rate of 56.8% ± 5.6% (P < 0.05) and 16.4% ± 3.3% (P < 0.05), respectively (Fig. 5D).

Figure 5.

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 have partially redundant roles in rice meiosis. A, Meiotic chromosome behavior in Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+, Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/−, Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/−, and Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/−. Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+ and Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/− showed normal chromosome behavior, whereas Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/− and Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/− displayed defects in homologous pairing (red arrows) and bivalent formation. B, Detection of bouquet formation in Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+, Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/−, Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/−, and Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/−. Chromosomes at zygotene were stained with DAPI (blue). pAtT4 (red) was used as a marker for telomere. C, Dual-immunolocalization of OsREC8 (red) and HEI10 (green) in Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+, Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/−, Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/−, and Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/−. Some unsynapsed regions without HEI10 foci are indicated by arrows (white). Bars = 5 µm. D, Quantifications of seed-setting rates in wild type (AABB), Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+ (aaBB), Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/− (aaBb), Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/− (AAbb), Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/− (Aabb), and Ossun1−/− Ossun2−/− (aabb). Values are means ± sem, n = 3. Lowercase letters indicate significant difference by two-tailed Student’s t tests (a, P = 0.36 or P = 0.73, and b–d, P < 0.05). E and F, Quantifications of the number of bivalents (E) and chiasma frequency (F) in AAbb, Aabb, and aabb.

When meiotic progression in Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/− was investigated, defects in homologous pairing (Fig. 5, A and C, arrows) and CO formation were also detected (Fig. 5, A and C). Statistical analysis showed that 90.4% of PMCs (n = 31) had 12 or 11 bivalents, and the number of chiasmata in 45.2% and 48.4% of PMCs was ≥ 19 or 16 to 18 (Fig. 5, E and F), respectively. The telomere bouquet-like configuration was observed in about 85.7% of zygotene-stage PMCs (n = 35) in Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/− (Fig. 5B). In contrast, Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/− displayed a more severe phenotype than Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/−, with about 73.2% of zygotene-stage PMCs (n = 41) showing failures to form telomere clusters (Fig. 5B). Besides, only 9.4% of PMCs (n = 32) had 12 bivalents in Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/−, and the number of chiasmata in 53.1% of PMCs was 13 to 15 (Fig. 5, E and F). Therefore, OsSUN2 is able to compensate for the loss of OsSUN1 during meiosis, but not vice versa. This suggested that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 are not completely redundant and OsSUN2 plays a more critical role in meiosis regulation. Moreover, we found that the reduction in fertility and COs in Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/− was more severe than that in Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/− but was less severe than that in the double mutant Ossun1−/− Ossun2−/− (Fig. 5, D–F). These data revealed a dosage-dependent effect between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, indicating that OsSUN1 still has a role in rice meiosis, which can only be detected when the function of OsSUN2 is completely lost.

The Functional Divergence between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2

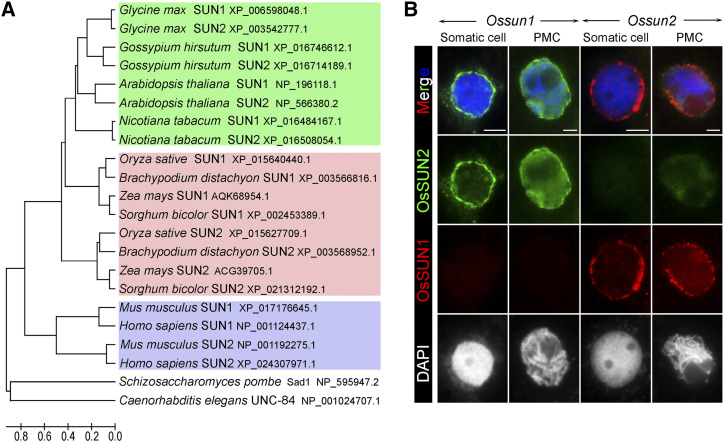

To verify the functional divergence between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, phylogenetic analyses were performed using protein sequences from representative species. The neighbor-joining method was used to construct an unrooted tree. These analyses revealed that SUN1 and SUN2 proteins from monocotyledonous species were assigned into two separate groups, whereas those from dicotyledonous plants were closely related to each other (Fig. 6A). This suggested that the functions of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in monocotyledons may have differentiated during evolution. Like the monocotyledon SUN proteins, mammalian SUN1 and SUN2 also belonged to two separate clades in the phylogenetic tree (Fig. 6A); these mammalian proteins have also been shown to have partially redundant functions in both somatic and meiotic cells (Lei et al., 2009; Link et al., 2014).

Figure 6.

The functional divergence between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2. A, Phylogenetic analysis of SUN1 and SUN2 proteins from representative dicotyledons (green), monocotyledons (pink), and mammals (purple). The neighbor-joining method was used to construct an unrooted tree. SUN1 and SUN2 from dicotyledons were closely related to each other, but SUN1 and SUN2 from monocotyledonous species and mammals were assigned to two separate clades. B, The loading dependency of OsSUN1 (red) and OsSUN2 (green) was investigated using immunofluorescence assays. Chromosomes of somatic cells and PMCs were stained with DAPI (blue or white). Bars = 5 µm.

To further investigate the divergence between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, quantitative PCRs were performed to examine the expression patterns of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2. We found that although OsSUN2 plays a more critical role than OsSUN1 during meiosis, the expression level of OsSUN2 is lower than that of OsSUN1 in meiosis-stage panicles, leaves, and roots (Supplemental Fig. S8A). This result suggested that the differential meiotic effects of loss of either of the two genes are not tightly associated with the differential expression levels.

Next, we investigated the loading dependency of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 using immunofluorescence assays. Normal signals corresponding to OsSUN1 were detected in the Ossun2 single mutant and vice versa (Fig. 6B). Thus, although OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 colocalized during meiosis, their localization is independent of each other. In addition, no OsSUN1 signal was detected either in the Ossun1 single mutant or the Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant in both the immunofluorescence assay and western blotting analysis, and the same results were acquired when using anti-OsSUN2 (Fig. 6B, Supplemental Fig. S8B), indicating the specificity of these two antibodies. Taking these results together with the genetic dosage-dependent effect between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, we proposed that OsSUN2 may play a more dominant role than OsSUN1 in rice meiosis.

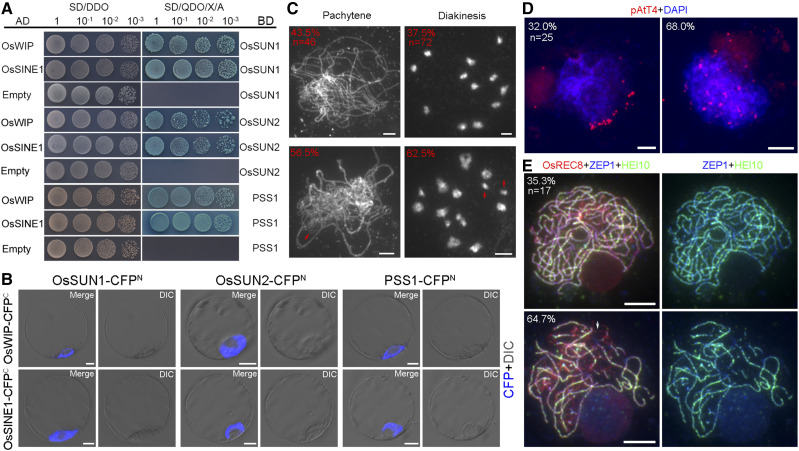

The Tandem Relationship of SUN-KASH-PSS1 Is Established on the NE

Although interactions between SUN and KASH proteins have been validated in many organisms, their relationship is still unclear in rice. O. sativa WPP domain-interacting protein (OsWIP, Os04g0471300), O. sativa SUN domain-binding and NE localization protein1 (OsSINE1, Os11g0580000), and OsSINE2 (Os12g0624800) are predicted to encode KASH proteins in rice (Zhou et al., 2015; Poulet et al., 2017). To detect possible interactions between rice KASH and SUN proteins, we cloned the full-length CDSs of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 into pGBKT7, and the full-length CDSs of OsWIP, OsSINE1, and OsSINE2 into pGADT7. Then, pairs of vectors were cotransformed into yeast cells, and coexpression was triggered by plating cells on double dropout medium (SD/-Leu/-Trp) and quadruple dropout medium (QDO; SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp). Transformants with these vector pairs (OsSUN1-BD and OsWIP-AD, OsSUN1-BD and OsSINE1-AD, OsSUN2-BD and OsWIP-AD, OsSUN2-BD and OsSINE1-AD) grew well on QDO/X/A medium (Fig. 7A), indicating that the OsWIP and OsSINE1 KASH proteins interact with OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in rice. We also found that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 interacted with themselves and each other (Supplemental Fig. S9).

Figure 7.

The tandem relationship of SUN-KASH-PSS1 is established on the nuclear envelope. A, Interactions between the KASH proteins (OsWIP and OsSINE1) and OsSUN1/OsSUN2/PSS1 were detected in yeast two-hybrid assays. SD/DDO, Double dropout medium; SD/QDO/X/A, quadruple dropout medium with x-α-gal and aureobasidin A. B, BiFC assays in rice protoplasts to validate these interactions. Cyan fluorescent protein signals (CFP, blue) were observed as a ring-like configuration on the nuclear envelope. C to E, The meiotic phenotypes of the pss1 mutant. The percentages of PMCs with or without defects are indicated at the top left corners. C, The meiotic chromosome behavior at pachytene and diakinesis in pss1. Some unpaired chromosomes and univalents are indicated with red arrows. D, Telomere behavior detected by pAtT4 (red) in pss1. Chromosomes at zygotene were stained with DAPI (blue). E, Triple immunolocalization of OsREC8 (red), HEI10 (green), and ZEP1 (blue) in pss1. The white arrow indicates the unsynapsed region without HEI10 or ZEP1 foci. Bars = 5 µm.

Pollen semisterility1 (PSS1), a kinesin-1-like protein that is mainly localized in the cytoplasm of rice protoplasts, is required for fertility in rice (Zhou et al., 2011). The Arabidopsis ortholog of PSS1 was shown to be required for synapsis and CO distribution during meiosis (Duroc et al., 2014). Our yeast two-hybrid experiments detected interactions between PSS1 and OsWIP as well as between PSS1 and OsSINE1 (Fig. 7A). To validate these interactions, we conducted bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assays in rice protoplasts. Cyan fluorescent protein signals were observed in cells coexpressing each vector pair, and ring-like NE localization was observed (Fig. 7B; Supplemental Fig. S10). This suggested that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 can recruit cytoplasmic PSS1 to the NE through interactions with KASH proteins.

When observing the phenotype of the pss1 mutant in rice, we found about 56.5% (n = 46) and 62.5% (n = 72) of PMCs had defects in chromosomal pairing at pachytene and bivalent formation at diakinesis (Fig. 7C), respectively. Using pAtT4 as a probe for telomeres, we detected that about 68.0% (n = 25) of PMCs in the pss1 mutant showed a failure in telomere clustering (Fig. 7D). Furthermore, the immunodetection of ZEP1 and HEI10 revealed that about 64.7% (n = 17) of PMCs displayed discontinuous ZEP1 and HEI10 stretches at pachytene (Fig. 7E). These data suggested that the meiotic defects in the pss1 mutant are similar to those of the Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant, strengthening that SUN proteins and PSS1 may act in the same pathway. Taken together, these results implied that KASH proteins may transfer the force that was generated by the kinesin PSS1 and then pass it to SUN to drive telomere clustering and later meiotic progression in rice.

DISCUSSION

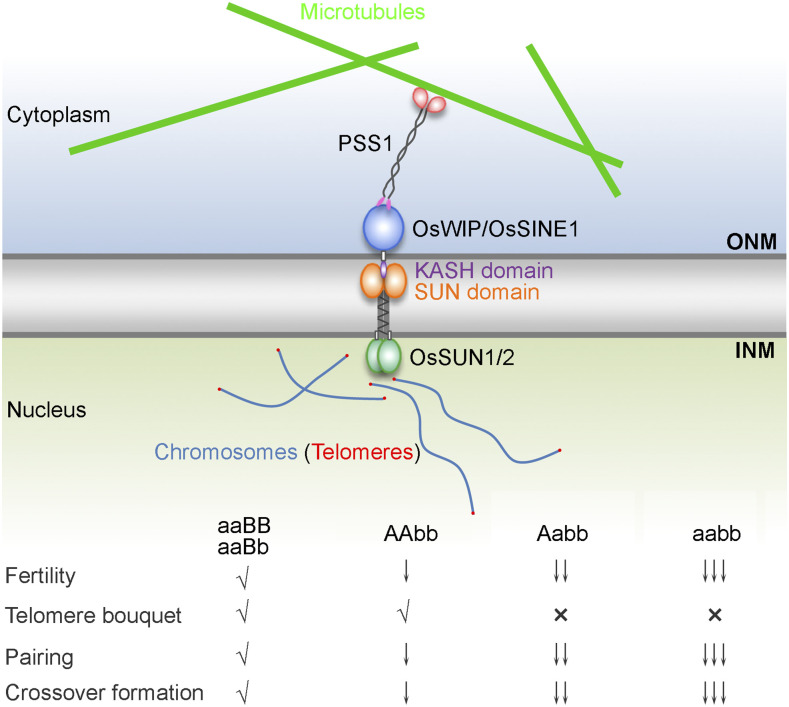

Previous studies have demonstrated that SUN proteins have a broadly conserved role, functioning as key players in chromosome dynamics during meiosis (Scherthan, 2001; Harper et al., 2004; Starr and Fridolfsson, 2010). Nonetheless, many aspects of rice meiotic bouquet formation and pairing, including their regulation, are not yet fully understood. For example, whether OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 function redundantly during rice meiosis remains unknown. Also, research is still required to determine the contributions of SUN protein-mediated bouquet formation and SPO11-induced recombination to homologous pairing, and we still lack a full understanding of the mechanisms by which SUN proteins affect recombination. In this study, these questions have been deeply investigated and key linkages between bouquet formation and other meiotic events have been identified, leading to the putative functional model for the role of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in rice meiosis (Fig. 8). In this model, the INM-anchored OsSUN1/2 complex interacts with the outer nuclear membrane-anchored KASH proteins OsWIP/OsSINE1 to recruit the kinesin-1-like protein PSS1 from the cytoplasm to the NE, thus promoting telomere clustering, homologous pairing, and CO maturation during meiosis. However, mutation of one or both copies of the OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 genes leads to varied levels of meiotic defects, suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 have partially redundant roles in rice meiosis and that OsSUN2 plays a more dominant role.

Figure 8.

A putative functional model for the role of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 during meiosis. During rice meiosis, the INM-anchored OsSUN1/2 complex interacts with the outer nuclear membrane (ONM)-anchored KASH proteins OsWIP/OsSINE1 to recruit the kinesin-1-like protein PSS1 from the cytoplasm to the nuclear envelope, thus promoting telomere clustering, homologous pairing, and CO maturation. However, mutation of one or both copies of the OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 genes leads to varied levels of meiotic defects, suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 have partially redundant roles in rice meiosis and that OsSUN2 plays a more dominant role. The symbol “√” indicates normal phenotype, “×” indicates disrupted telomere bouquet, and the number of “↓” symbols represents the level of defective reduction. aaBB, Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/+; aaBb, Ossun1−/− Ossun2+/−; AAbb, Ossun1+/+ Ossun2−/−; Aabb, Ossun1+/− Ossun2−/−; aabb, Ossun1−/− Ossun2−/−.

OsSUN2 Plays a More Important Role in Rice Meiosis

In Arabidopsis, AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 are thought to have completely redundant functions during meiosis; the single mutants display no obvious loss of fertility and have normal meiotic progression, but when combining the two single mutations, a significant reduction in fertility and severe meiotic defects are observed (Varas et al., 2015). In contrast, the rice Ossun2 single mutant exhibited reduced fertility and disrupted meiosis, whereas the Ossun1 single mutant showed no obvious defects. Consistent with this, our phylogenetic analyses found that AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 were closely related to each other, whereas OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 were assigned to two separated clades in an unrooted tree. These results reveal the functional divergence of rice SUN proteins in meiosis regulation, which is quite different from the lack of divergence of their Arabidopsis counterparts. Besides, both the protein sequence and expression pattern of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 show some divergences between them. These findings, in combination with the dosage-dependent effects between OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, lead us to propose that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 function partially redundantly in rice meiosis and that OsSUN2 plays a more dominant role.

MmSUN1 and MmSUN2, the meiosis-specific SUN proteins in mice, were also shown to have partially redundant meiotic functions (Link et al., 2014). Although MmSUN2 was found to be required for NE-associated telomere clustering in SUN1-deficient meiocytes, the infertile phenotype of the Mmsun1−/− single mutant demonstrated that MmSUN2 is not able to effectively compensate for the loss of MmSUN1 in meiosis (Ding et al., 2007; Schmitt et al., 2007; Link et al., 2014). These observations in mammals accord closely with our phylogenetic analyses, which revealed that SUN1 and SUN2 in mammals are also found in two separate branches of the unrooted tree. These data suggest that the functions of SUN proteins have diverged during evolution.

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 Facilitate Full-Length Pairing but Are Dispensable for the Initiation of Homologous Pairing

It is generally believed that bouquet formation is an evolutionarily conserved meiotic event necessary for homologous pairing (Scherthan, 2001; Harper et al., 2004). Our data revealed that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 have partially redundant functions in telomere clustering during rice meiosis. The Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant showed severe defects in telomere clustering, leading to the absence of the typical “bouquet” organization at zygotene. However, OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 deficiency did not fully suppress the homologous pairing process. A high level of homologous chromosome alignment was still detected in the Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant, indicating that the telomere bouquet is not absolutely required for the initiation of homologous pairing. In agreement with our results, other bouquet-deficient mutants, such as nondisjunction1Δ (ndj1Δ), plural abnormalities of meiosis1 (pam1), and Atsun1 Atsun2, also achieve some degree of pairing (Trelles-Sticken et al., 2000; Golubovskaya et al., 2002; Varas et al., 2015). Therefore, the effect of the telomere bouquet on homologous pairing during meiosis seems to be limited. Considering the partial alignment of chromosomes observed in the double mutant, we propose that telomere clustering mediated by OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 may promote the extension of homologous pairing from the initiation sites to full-length chromosomes.

OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 Are Not Required for Early Recombination but Guarantee Normal CO Maturation

According to our data, DSB formation and loading of early recombination-related factors occurs normally in the Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant, suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 deficiency does not affect the initiation or early processes of homologous recombination. In turn, mutation of OsSPO11-1 also had no effect on telomere clustering. Taken together, these results indicate that bouquet formation and DSB formation are two mutually independent meiotic events. In addition to telomere bouquet formation, recombination-dependent homologous recognition is another vital event for homologous pairing in many eukaryotes. This process relies on interchromosomal interactions that result from the initial steps in SPO11-induced DSB formation and the later steps of recombinase-mediated homology searching (Naranjo, 2012; Zickler and Kleckner, 2015). Homologous pairing was fully disrupted in the rice Osspo11-1 mutant, further demonstrating that recombination is necessary for the pairing process. Introducing Osspo11-1 into the Ossun1 Ossun2 background led to serious defects in both pairing and telomere clustering, suggesting that OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 promote homologous pairing downstream of OsSPO11-1 but promote bouquet formation independent of OsSPO11-1. Moreover, the normal loading of OsZIP4 on chromosomes indicates that CO designation is not affected in the Ossun1 Ossun2 mutant. However, the maturation of CO-designated intermediates depends on normal chromosomal alignment in a wide range of species (Lambing et al., 2015; Zickler and Kleckner, 2015). Because of the partial alignment of chromosomes and the restricted distribution of HEI10 foci on synapsed regions in the double mutant, we reason that the reduction of chiasma frequency may be caused by the defects in full-length chromosomal alignment.

OsSUN1, OsSUN2, and KASH Proteins Recruit PSS1 to the NE

The rice PSS1 gene encodes a kinesin-1-like protein, which is predominantly localized in the cytoplasm of rice protoplasts and is required for fertility and meiotic chromosome segregation in rice (Zhou et al., 2011). Its Arabidopsis ortholog, AtPSS1, was subsequently revealed to play an essential role in synapsis and CO formation (Duroc et al., 2014). Yeast two-hybrid experiments showed that AtPSS1 interacts with WIP1 and WIP2, the KASH-domain proteins that interact with the SUN proteins. These data indicate that PSS1 might be the cytoskeletal element interacting with KASH proteins to generate forces that are transduced through the NE to chromosomes in plants. In our study, both OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 displayed dynamic NE localization. Further BiFC experiments validated the interactions of SUN-KASH and KASH-PSS1 at the NE in rice protoplasts. These results provide evidence for the hypothesis that, through interactions with KASH proteins, meiotic SUN proteins may recruit cytoplasmic PSS1 to the NE to promote normal progression of rice meiosis. Further investigations need to be conducted on the proteins that connect SUN proteins and telomeres.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

The double mutants Ossun1-1 Ossun2-1 and Ossun1-2 Ossun2-2 were generated by targeted mutagenesis of the OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 genes in the japonica rice (Oryza sativa) variety Yandao 8 using CRISPR-Cas9 technology. The corresponding single mutants were segregated from the double heterozygous mutant Ossun1+/− Ossun2+/−. The zygo1 mutant used in this study was reported previously (Zhang et al., 2017), and the Osspo11-1 mutant was induced by 60Co γ-ray irradiation in our lab. The pss1 mutant allele was previously reported (Zhou et al., 2011). The japonica rice variety Yandao 8 was used for wild-type analysis. All plant materials were grown in paddy fields in Beijing or Hainan Province, China.

CRISPR-Cas9 Targeting of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2

For targeted mutation of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, target sites in these two genes were selected, and primers specific to these sites were designed (Supplemental Table S1). The intermediate vector SK-gRNA and the binary vector pC1300-cas9 of the CRISPR-Cas9 system were used in this study. Vector construction and transformation were performed as previously described (Zhang et al., 2017).

Antibody Production

The rabbit polyclonal antibody against OsSUN1 was produced by GenScript using the synthetic peptide “IRGESVLGKSKYPL” (Zhang et al., 2017). To generate the mouse polyclonal antibody against OsSUN2, the 822 bp C-terminal fragment of OsSUN2 cDNA (amino acids 181–454) was amplified using primers OsSUN2-Ab-F and OsSUN2-Ab-R (Supplemental Table S1). This PCR product was cloned into the expression vector pET30a (Amersham). Then, the His-fused OsSUN2 peptide was expressed and purified and used to immunize mice. The primary antibodies against PAIR3, γH2AX, OsDMC1, OsZIP4, ZEP1, and HEI10 were from our lab.

Western Blotting

Total proteins were extracted from rice meiotic panicles (5–7 cm) with an extraction buffer that was previously described (Li et al., 2018). Protein samples were separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12% (v/v) polyacrylamide gel and electroblotted onto polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (GE Healthcare). Western blots were conducted with anti-OsSUN1 (1:1,000) or anti-OsSUN2 (1:10,000) primary antibodies, followed by incubation with anti-rabbit or anti-mouse secondary antibodies conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Abcam, diluted 1:15,000). The internal reference HSP90 was detected with an anti-HSP90 antibody (BGI).

Chromosome Preparation

Young panicles of both wild-type and mutant plants were harvested and fixed in Carnoy’s solution (ethanol:acetic acid, 3:1). Meiosis-stage anthers were squashed in 1% (w/v) acetocarmine solution and then washed with 45% (v/v) acetic acid. Slides were frozen in liquid nitrogen for a few minutes and then the coverslips were removed. After dehydration through an ethanol series (70%, 90%, 100% [v/v]), the slides were stained with DAPI in an antifade solution (Vector Laboratories).

FISH Analysis

The FISH analysis was conducted as previously described (Zhang et al., 2017). The pAtT4 clone containing telomeric repeats was used as a probe for anchoring telomeres. The bulked oligonucleotide probes painting chromosome 11 (short and long arm) were developed following previously reported procedures (Zhang et al., 2017). These probes were finally labeled with biotin or digoxigenin and detected by Alexa Fluor 488 streptavidin and rhodamine antidigoxigenin, respectively.

Immunofluorescence Assay

For immunodetection of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2, fresh panicles were fixed in 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde at 4°C for about 6 h. For other meiotic proteins, panicles were fixed at room temperature for 0.5 to 2 h. Meiosis-stage anthers were squashed in 1× PBS and then slides were frozen in liquid nitrogen for a few minutes. After the coverslips were removed, diluted antibodies were placed on the slides, and the slides were incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After washing with 1× PBS, one of the following fluorochrome-coupled secondary antibodies was added to the slides for fluorescence detection: fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody (Southern Biotech), rhodamine-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Southern Biotech), and aminomethylcoumarin acetate-conjugated goat anti-guinea pig antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). After incubation at 37°C for another hour, the slides were washed again and eventually stained with DAPI.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay

For yeast two-hybrid assays, the full-length CDSs of OsSUN1, OsSUN2, and PSS1 were cloned into the pGBKT7 vector, whereas the full-length CDSs of OsWIP, OsSINE1, and OsSINE2 were amplified and inserted into the pGADT7 vector. The primers for vector construction are listed in Supplemental Table S1. The bait and prey vectors were cotransformed into the yeast strain Y2HGOLD using the Matchmaker Gold yeast two-hybrid system (Clontech, no. 630489). The transformants were first cultured on double dropout (SD/-Trp-Leu) medium, and surviving clones were further screened on QDO (SD/-Trp-Leu-His-Ade) medium with X-α-gal and aureobasidin A to examine the interaction. Detailed procedures from the Yeast Handbook (Clontech) were followed.

BiFC Assay

To conduct BiFC assays, the full-length CDSs of related genes were amplified by specific primers (Supplemental Table S1) and then ligated into the BiFC vector pairs: pSCYNE (SCFP3A N-terminus) and pSCYCE(R; SCFP3A C-terminus). Then, the proper plasmid pairs were cotransformed into rice protoplasts using polyethylene glycol-mediated transformation. After incubation in darkness for 18 h at 28°C, the cyan fluorescent protein signals were finally captured at an excitation wavelength of 405 nm using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica TCS SP5).

Image Capture and Data Analysis

Superresolution images were captured with a Delta Vision microscope (OMX V4; GE Healthcare) and processed with SoftWoRx (Applied Precision). Other images were captured under a Zeiss A2 fluorescence microscope with a micro CCD camera and processed with Photoshop CS2 (Adobe). Quantitative colocalization analysis was performed using Image J according to a previous report (Li et al., 2004). Statistical significance was determined by unpaired two-tailed t test, and graphs were drawn with GraphPad Prism 6 software (http://www.graphpad.com/). The multiple sequence alignment was conducted using MAFFT (https://toolkit.tuebingen.mpg.de/#/tools/mafft) and colored with ESPript (http://espript.ibcp.fr/ESPript/ESPript/). The protein domains were predicted by SMART (http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/) and drawn by IBS software (http://ibs.biocuckoo.org/).

Accession Numbers

Sequence data of the major genes from this article can be found in the NCBI data libraries under the following accession numbers: OsSUN1 (O. sativa), Os05g0270200; OsSUN2 (O. sativa), Os01g0267600; AtSUN1 (Arabidopsis), At5g04990; AtSUN2 (Arabidopsis), At3g10730; ZYGO1 (O. sativa), Os01g0219200; OsSPO11-1 (O. sativa), Os03g0752200; OsWIP (O. sativa), Os04g0471300; OsSINE1 (O. sativa), Os11g0580000; OsSINE2 (O. sativa), Os12g0624800; PSS1 (O. sativa), Os08g0117000. Accession numbers of the homologs of SUN1 and SUN2 used in the neighbor-joining tree construction are as follows: OsSUN1 (O. sativa), XP_015640440.1; OsSUN2 (O. sativa), XP_015627709.1; SUN1 (Z. mays), AQK68954.1; SUN2 (Z. mays), ACG39705.1; SUN1 (Sorghum bicolor), XP_002453389.1; SUN2 (S. bicolor), XP_021312192.1; SUN1 (Brachypodium distachyon), XP_003566816.1; SUN2 (B. distachyon), XP_003568952.1; AtSUN1 (Arabidopsis), NP_196118.1; AtSUN2 (Arabidopsis), NP_566380.2; SUN1 (Nicotiana tabacum), XP_016484167.1; SUN2 (N. tabacum), XP_016508054.1; SUN1 (Glycine max), XP_006598048.1; SUN2 (G. max), XP_003542777.1; SUN1 (Gossypium hirsutum), XP_016746612.1; SUN2 (G. hirsutum), XP_016714189.1; SUN1 (Mus musculus), XP_017176645.1; SUN2 (M. musculus), NP_001192275.1; SUN1 (Homo sapiens), NP_001124437.1; SUN2 (H. sapiens), XP_024307971.1; Sad1 (Schizosaccharomyces pombe), NP_595947.2; UNC-84 (Caenorhabditis elegans), NP_001024707.1.

Supplemental Data

The following supplemental materials are available.

Supplemental Figure S1. Multiple sequence alignments of the SUN domains of OsSUN1, OsSUN2, and their orthologs.

Supplemental Figure S2. Alignment of the full-length protein sequences of OsSUN1, OsSUN2, AtSUN1, and AtSUN2.

Supplemental Figure S3. Subcellular localization of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 in rice protoplasts.

Supplemental Figure S4. The phenotype of Ossun1-2 Ossun2-2.

Supplemental Figure S5. The Ossun1 Ossun2 double mutant showed extension of the duration of pachytene.

Supplemental Figure S6. Full-length synapsis was affected in Ossun1 Ossun2.

Supplemental Figure S7. Normal loading of γH2AX, OsDMC1, and OsZIP4 was observed in Ossun1 Ossun2.

Supplemental Figure S8. Expression patterns of OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 and the antibody specificity of anti-OsSUN1 and anti-OsSUN2.

Supplemental Figure S9. OsSUN1 and OsSUN2 interacted with themselves and each other in a yeast two-hybrid assay.

Supplemental Figure S10. The positive and negative controls in BiFC assays.

Supplemental Table S1. List of primers used in this study.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 31930018) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (grant no. 2016YFD0100901).

Articles can be viewed without a subscription.

References

- Chikashige Y, Tsutsumi C, Yamane M, Okamasa K, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y(2006) Meiotic proteins bqt1 and bqt2 tether telomeres to form the bouquet arrangement of chromosomes. Cell 125: 59–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chikashige Y, Yamane M, Okamasa K, Tsutsumi C, Kojidani T, Sato M, Haraguchi T, Hiraoka Y(2009) Membrane proteins Bqt3 and -4 anchor telomeres to the nuclear envelope to ensure chromosomal bouquet formation. J Cell Biol 187: 413–427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad MN, Dominguez AM, Dresser ME(1997) Ndj1p, a meiotic telomere protein required for normal chromosome synapsis and segregation in yeast. Science 276: 1252–1255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding X, Xu R, Yu J, Xu T, Zhuang Y, Han M(2007) SUN1 is required for telomere attachment to nuclear envelope and gametogenesis in mice. Dev Cell 12: 863–872 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duroc Y, Lemhemdi A, Larchevêque C, Hurel A, Cuacos M, Cromer L, Horlow C, Armstrong SJ, Chelysheva L, Mercier R(2014) The kinesin AtPSS1 promotes synapsis and is required for proper crossover distribution in meiosis. PLoS Genet 10: e1004674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Göb E, Schmitt J, Benavente R, Alsheimer M(2010) Mammalian sperm head formation involves different polarization of two novel LINC complexes. PLoS One 5: e12072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golubovskaya IN, Harper LC, Pawlowski WP, Schichnes D, Cande WZ(2002) The pam1 gene is required for meiotic bouquet formation and efficient homologous synapsis in maize (Zea mays L.). Genetics 162: 1979–1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann K, Runions J, Evans DE(2010) Characterization of SUN-domain proteins at the higher plant nuclear envelope. Plant J 61: 134–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann K, Vanrobays E, Tutois S, Probst AV, Evans DE, Tatout C(2014) Characterization of two distinct subfamilies of SUN-domain proteins in Arabidopsis and their interactions with the novel KASH-domain protein AtTIK. J Exp Bot 65: 6499–6512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper L, Golubovskaya I, Cande WZ(2004) A bouquet of chromosomes. J Cell Sci 117: 4025–4032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn HF, Kim DI, Wright GD, Wong ESM, Stewart CL, Burke B, Roux KJ(2013) A mammalian KASH domain protein coupling meiotic chromosomes to the cytoskeleton. J Cell Biol 202: 1023–1039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang XZ, Yang MG, Huang LH, Li CQ, Xing XW(2011) SPAG4L, a novel nuclear envelope protein involved in the meiotic stage of spermatogenesis. DNA Cell Biol 30: 875–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambing C, Osman K, Nuntasoontorn K, West A, Higgins JD, Copenhaver GP, Yang J, Armstrong SJ, Mechtler K, Roitinger E, et al. (2015) Arabidopsis PCH2 mediates meiotic chromosome remodeling and maturation of crossovers. PLoS Genet 11: e1005372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei K, Zhang X, Ding X, Guo X, Chen M, Zhu B, Xu T, Zhuang Y, Xu R, Han M(2009) SUN1 and SUN2 play critical but partially redundant roles in anchoring nuclei in skeletal muscle cells in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 10207–10212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Lau A, Morris TJ, Guo L, Fordyce CB, Stanley EF(2004) A syntaxin 1, Galpha(o), and N-type calcium channel complex at a presynaptic nerve terminal: Analysis by quantitative immunocolocalization. J Neurosci 24: 4070–4081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Qin B, Shen Y, Zhang F, Liu C, You H, Du G, Tang D, Cheng Z(2018) HEIP1 regulates crossover formation during meiosis in rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 115: 10810–10815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link J, Leubner M, Schmitt J, Göb E, Benavente R, Jeang KT, Xu R, Alsheimer M(2014) Analysis of meiosis in SUN1 deficient mice reveals a distinct role of SUN2 in mammalian meiotic LINC complex formation and function. PLoS Genet 10: e1004099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone CJ, Fixsen WD, Horvitz HR, Han M(1999) UNC-84 localizes to the nuclear envelope and is required for nuclear migration and anchoring during C. elegans development. Development 126: 3171–3181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolcevic P, Isoda M, Shibuya H, del Barco Barrantes I, Igea A, Suja JA, Shackleton S, Watanabe Y, Nebreda AR(2016) Essential role of the Cdk2 activator RingoA in meiotic telomere tethering to the nuclear envelope. Nat Commun 7: 11084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morimoto A, Shibuya H, Zhu X, Kim J, Ishiguro K, Han M, Watanabe Y(2012) A conserved KASH domain protein associates with telomeres, SUN1, and dynactin during mammalian meiosis. J Cell Biol 198: 165–172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SP, Bass HW(2012) The maize (Zea mays) desynaptic (dy) mutation defines a pathway for meiotic chromosome segregation, linking nuclear morphology, telomere distribution and synapsis. J Cell Sci 125: 3681–3690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SP, Gumber HK, Mao Y, Bass HW(2014) A dynamic meiotic SUN belt includes the zygotene-stage telomere bouquet and is disrupted in chromosome segregation mutants of maize (Zea mays L.). Front Plant Sci 5: 314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SP, Simmons CR, Bass HW(2010) Structure and expression of the maize (Zea mays L.) SUN-domain protein gene family: Evidence for the existence of two divergent classes of SUN proteins in plants. BMC Plant Biol 10: 269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo T.(2012) Finding the correct partner: The meiotic courtship. Scientifica (Cairo) 2012: 509073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y, Fukuda H(2011) Dynamics of Arabidopsis SUN proteins during mitosis and their involvement in nuclear shaping. Plant J 66: 629–641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poulet A, Probst AV, Graumann K, Tatout C, Evans D(2017) Exploring the evolution of the proteins of the plant nuclear envelope. Nucleus 8: 46–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherthan H.(2001) A bouquet makes ends meet. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2: 621–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt J, Benavente R, Hodzic D, Höög C, Stewart CL, Alsheimer M(2007) Transmembrane protein Sun2 is involved in tethering mammalian meiotic telomeres to the nuclear envelope. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 7426–7431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya H, Hernández-Hernández A, Morimoto A, Negishi L, Höög C, Watanabe Y(2015) MAJIN links telomeric DNA to the nuclear membrane by exchanging telomere cap. Cell 163: 1252–1266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya H, Ishiguro K, Watanabe Y(2014) The TRF1-binding protein TERB1 promotes chromosome movement and telomere rigidity in meiosis. Nat Cell Biol 16: 145–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr DA, Fridolfsson HN(2010) Interactions between nuclei and the cytoskeleton are mediated by SUN-KASH nuclear-envelope bridges. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 26: 421–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran PT, Marsh L, Doye V, Inoué S, Chang F(2001) A mechanism for nuclear positioning in fission yeast based on microtubule pushing. J Cell Biol 153: 397–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trelles-Sticken E, Dresser ME, Scherthan H(2000) Meiotic telomere protein Ndj1p is required for meiosis-specific telomere distribution, bouquet formation and efficient homologue pairing. J Cell Biol 151: 95–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu Z, Bayazit MB, Liu H, Zhang J, Busayavalasa K, Risal S, Shao J, Satyanarayana A, Coppola V, Tessarollo L, et al. (2017) Speedy A-Cdk2 binding mediates initial telomere-nuclear envelope attachment during meiotic prophase I independent of Cdk2 activation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 114: 592–597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varas J, Graumann K, Osman K, Pradillo M, Evans DE, Santos JL, Armstrong SJ(2015) Absence of SUN1 and SUN2 proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana leads to a delay in meiotic progression and defects in synapsis and recombination. Plant J 81: 329–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viera A, Alsheimer M, Gómez R, Berenguer I, Ortega S, Symonds CE, Santamaría D, Benavente R, Suja JA(2015) CDK2 regulates nuclear envelope protein dynamics and telomere attachment in mouse meiotic prophase. J Cell Sci 128: 88–99 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang K, Wang M, Tang D, Shen Y, Miao C, Hu Q, Lu T, Cheng Z(2012) The role of rice HEI10 in the formation of meiotic crossovers. PLoS Genet 8: e1002809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Katsuyama S, Tateho K, Nakamura H, Miyoshi J, Ohba T, Matsuhara H, Miki F, Okazaki K, Haraguchi T, et al. (2013) Microtubule-organizing center formation at telomeres induces meiotic telomere clustering. J Cell Biol 200: 385–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H, Wang M, Tang D, Wang K, Chen F, Gong Z, Gu M, Cheng Z(2010) OsSPO11-1 is essential for both homologous chromosome pairing and crossover formation in rice. Chromosoma 119: 625–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F, Tang D, Shen Y, Xue Z, Shi W, Ren L, Du G, Li Y, Cheng Z(2017) The F-box protein ZYGO1 mediates bouquet formation to promote homologous pairing, synapsis, and recombination in rice meiosis. Plant Cell 29: 2597–2609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S, Wang Y, Li W, Zhao Z, Ren Y, Wang Y, Gu S, Lin Q, Wang D, Jiang L, et al. (2011) Pollen semi-sterility1 encodes a kinesin-1-like protein important for male meiosis, anther dehiscence, and fertility in rice. Plant Cell 23: 111–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou X, Graumann K, Meier I(2015) The plant nuclear envelope as a multifunctional platform LINCed by SUN and KASH. J Exp Bot 66: 1649–1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickler D, Kleckner N(1998) The leptotene-zygotene transition of meiosis. Annu Rev Genet 32: 619–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickler D, Kleckner N(2015) Recombination, pairing, and synapsis of homologs during meiosis. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 7: a016626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]