Abstract

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a syndrome of severe immune dysregulation, characterised by extreme inflammation, fever, cytopaenias and organ dysfunction. HLH can be triggered by conditions such as infection, autoimmune disease and malignancy, among others. Both a familial and a secondary form have been described, the latter being increasingly recognised in adult patients with critical illness. HLH is difficult to diagnose, often under-recognised and carries a high mortality. Patients can present in a very similar fashion to sepsis and the two syndromes can co-exist and overlap, yet HLH requires specific immunosuppressive therapy. HLH should be actively excluded in patients with presumed sepsis who either lack a clear focus of infection or who are not responding to energetic infection management. Elevated serum ferritin is a key biomarker that may indicate the need for further investigations for HLH and can guide treatment. Early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach to HLH management may save lives.

Keywords: Lymphohistiocytosis, haemophagocytic, histiocytosis, macrophage activation syndrome, sepsis

Introduction

Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a potentially life-threatening syndrome characterised by dysregulation of immune cells, excessive production of cytokines, extreme inflammation and tissue damage. HLH may be indolent or progress to a self-perpetuating, hyperinflammatory cytokine storm and multiorgan failure. HLH can be triggered by infection, malignancy and rheumatological disease and has a high acute mortality rate of 40%.1 HLH is almost certainly under-recognised, or only recognised late at least partly due to the protean nature of presenting symptoms and lack of validated diagnostic criteria in adults. Early recognition and treatment of HLH potentially improves outcomes.2–5

The true prevalence of HLH in critical care is unknown. Sepsis, in particular, has a large overlap with HLH in both clinical features and pathophysiology3 and, crucially, infection may be an HLH trigger. HLH or a related syndrome of sepsis-induced hyperinflammation may be present in a distinct subset of critically ill patients with presumed or confirmed sepsis, particularly those who deteriorate despite intensive infection management. Given the very high mortality, it is important to consider and identify HLH early.6,7 Furthermore, therapeutic approaches involve heavy immunosuppression, a strategy that could appear counter-intuitive in septic patients.8

This article aims to provide an overview of adult-onset HLH for the general intensive care clinician, to outline pragmatic diagnostic and treatment approaches in light of the existing evidence, and to discuss emerging avenues for better characterisation of this heterogeneous clinical syndrome.

Historical context and terminology

Historically, HLH has been classified into familial HLH (fHLH, a genetic disorder presenting in infancy) and secondary or acquired HLH (sHLH, a secondary immune phenomenon diagnosed in later childhood, adolescence or adult life). However, there is a growing recognition of a complex interplay between inherited, acquired and environmental factors across all forms of HLH, leading to a large variability in the timing and severity of clinical disease expression. A key message for clinicians is that sHLH can occur at any age.

The existing terminology for sHLH is confusing, leading to a growing call for a unified nomenclature across specialties.8 HLH in the context of autoimmune disease is commonly referred to as macrophage activation syndrome (MAS).8 However, there are multiple alternative terms used, some of which refer to specific clinical circumstances. These include MALS (MAS-like syndrome), hyperferritinaemic syndrome, viral-associated haemophagocytic syndrome and sepsis–HLH overlap syndrome, among others.3,9–11 Of note, some studies have used broad surrogate definitions such as ‘sepsis with hepatobiliary dysfunction and disseminated intravascular coagulation’.11,12 Given this lack of unified terminology, acquired HLH should perhaps be considered a clinical syndrome rather than a ‘disease’ in itself, with the emphasis on early recognition and treatment. For practical purposes, we use the term sHLH in this review.

Pathogenesis

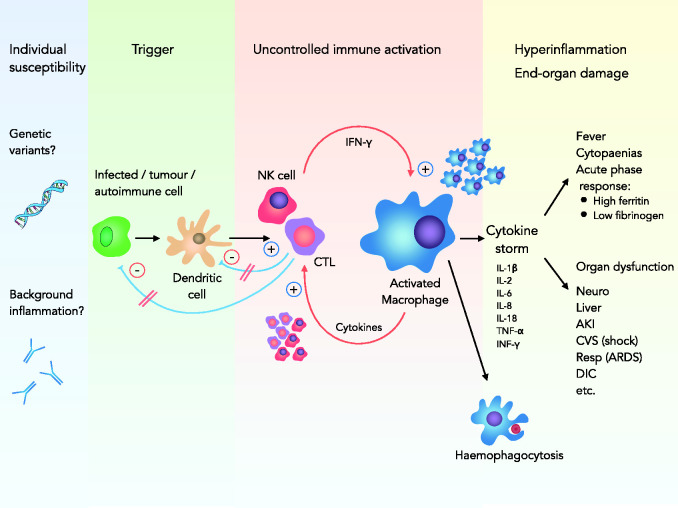

HLH is caused by a failure of the negative feedback loops that normally control inflammation. Our understanding of the complex pathophysiology of secondary HLH is still evolving; a basic overview of current concepts is therefore provided in Figure 1. The result of this dysregulation is persistent immune activation and a self-perpetuating hyperinflammatory state: the cytokine storm.8 The clinical sequelae are fever, cytopaenias, end-organ damage (often manifested as multiple organ dysfunction) and, in some cases, haemophagocytosis evident on biopsy of bone marrow or other tissues. It is important to note, however, that despite the syndromic name, haemophagocytosis need not be present and is not required for diagnosis.1,8

Figure 1.

Pathogenesis of sHLH. An underlying defect in NK cells and CTLs, on the background of preexisting susceptibility, leads to failure to clear antigen from infected tumour or autoimmune cells and antigen-presenting dendritic cells. This leads to uncontrolled immune stimulation with activation and proliferation of macrophages and CTLs in a self-perpetuating fashion. A massive production of cytokines (cytokine storm) results in hyperinflammation, end-organ damage and haemophagocytosis.

AKI: acute kidney injury; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; CTL: cytotoxic T lymphocyte; CVS: cardiovascular system; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulopathy; IFN-γ: interferon gamma; IL: interleukin; NK cell: natural killer cell; Resp: respiratory system; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; TNF: tumour necrosis factor.

Susceptibility to HLH seems to have a genetic basis for both primary and secondary forms. In fHLH patients, several discrete causative genetic defects involving cytolytic pathways have been identified. In sHLH, the genetic contribution is less well understood to date. However, there is emerging evidence for genetic variants involving similar genes and, for example, low natural killer cell (NK cell) activity has been reported in both sHLH patients and close relatives.13,14

sHLH can be triggered by a large variety of stimuli, including infection, haematological and other malignancy, rheumatological or autoimmune disease, severe burns, chemotherapy, other cancer therapies and stem-cell transplant, among others.1 However, in a proportion of patients no discrete trigger can be identified at the time.

Infection and sHLH

The leading trigger for sHLH worldwide is infection, which can be viral, bacterial, fungal or protozoal in origin (see Table 1).1,15–19

Table 1.

Infective triggers for sHLH.

| Infective triggers |

|---|

| Viral |

| Epstein–Barr virus |

| Other herpesviruses: CMV, HSV, HHV-6, VZV |

| Adeno-/enteroviruses |

| Hepatitis viruses |

| HIV |

| Parvovirus B19 |

| Dengue/Ebola viruses |

| Influenza A (especially H5N1 and H1N1 strains) and B |

| Others |

| Bacterial |

| Mycobacteria spp. |

| Rickettsia spp. |

| Legionella spp. |

| Staphylococcus spp. |

| Escherichia coli |

| Others |

| Parasitic |

| Leishmania spp. |

| Plasmodium spp. |

| Toxoplasma spp. |

| Others |

| Fungal |

| Histoplasma |

| Pneumocystis jiroveci |

| Candida spp. |

| Aspergillus spp. |

| Others |

CMV: cytomegalovirus; HHV-6: human herpesvirus 6; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; HSV: herpes simplex virus; sHLH: (secondary) haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; spp: species; VZV: varicella zoster virus.

Among many possible viral triggers, Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) is the predominant agent recognised in the developed world and much of Asia.1,19 However, its pathophysiological role is complex. EBV can be an independent trigger of HLH or precipitate sHLH in conjunction with associated malignancy (EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disorders). In some patients, EBV viraemia simply reflects the activation of lymphocytes containing virus; in this context, EBV can be seen as an innocent bystander.20

Bacterial infections are reported in around 9% of sHLH cases.1 Parasitic and fungal triggers are less frequently observed but should be considered in patients with immunosuppression, a relevant travel history or other suggestive clinical context.1,19 Visceral leishmaniasis is of particular importance as it is very effectively treated with liposomal amphotericin, even in the context of sHLH. The majority of recent UK cases were acquired in the Mediterranean littoral including Spain and Italy, with only small numbers from Africa, Asia and South America.21

Of note, the initial screen for an infective sHLH precipitant is often negative; specialised/repeat sampling is often required.

sHLH in malignancy and associated therapies

sHLH can be a direct consequence of malignancy or a result of cancer treatments such as chemotherapy, haematopoietic stem cell transplantation or novel immune therapies. Most commonly, it is associated with haematological malignancy, in particular lymphomas.22–24 sHLH has also been reported in solid cancers and is probably underdiagnosed in this group. sHLH may also occur after both haematological and solid organ transplantation, and is often associated with opportunistic infections.1 After haematopoietic stem cell transplantation, sHLH can mimic graft versus host disease, in which case hyperferritinaemia might be the key differentiating diagnostic feature.8,25,26

Most recently, hyperinflammatory clinical syndromes have been described in patients receiving novel targeted immunotherapy, increasingly used in cancer management. Intensivists are likely to see progressively more patients suffering from their unique side effects. Examples of potentially HLH-inducing therapies include monoclonal antibodies, dendritic vaccines, checkpoint inhibitor combinations and chimeric-antigen receptor T-cell (CAR-T) therapies.22 CAR-T therapy is strongly associated with overproduction of cytokines leading to systemic inflammation and organ dysfunction. The clinical syndrome is termed cytokine release syndrome (CRS) in its initial phase, but may progress to sHLH if severe. While the incidence of CRS is estimated to be very high (74%–100% in the anti-CD19 setting), the risk of developing sHLH in this context is currently less clear.27

Autoimmune disease and MAS

A large number of rheumatological and autoimmune diseases are associated with sHLH, where the syndrome is termed MAS for historical reasons. The strongest connection exists with systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis (sJIA), with an estimated sHLH incidence of 10% in paediatric and adolescent sJIA populations, often co-triggered by infection. In adult rheumatological practice, sHLH is most closely associated with adult-onset Still’s disease (on the same disease continuum as sJIA), and with systemic lupus erythematosus. In addition, sHLH has been described complicating rheumatoid arthritis, systemic vasculitides, inflammatory bowel disease and other conditions, where the main suspected triggers are infection and drug therapy.1,8,28

Sepsis and HLH: Overlap and distinguishing features

There is large overlap between the definitions for sHLH and sepsis. The recent consensus definition (‘Sepsis-3’) characterises sepsis as ‘life-threatening organ dysfunction caused by a dysregulated host response to infection’,29 a description that would be equally applicable to sHLH triggered by infection. Both conditions share similarities in their pathophysiology, cytokine profile and clinical features.3,7 It has to be noted that sepsis may demonstrate a variety of immunological phenotypes, from a predominant inflammatory response to suppressed immune function or a combination of both, and this may be subject to evolution over time.30,31 It has been suggested that sHLH could be implicated in the hyperinflammatory subset of septic patients.10,11,32 This is in keeping with a post-hoc analysis by Shakoory et al. of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) from the 1990s, which suggested a potential mortality benefit from IL-1 receptor blockade with Anakinra in septic ICU patients with hepatobiliary dysfunction and disseminated intravascular coagulopathy (DIC), but not in patients with either alone.12 However, due to statistical uncertainty (low fragility index), the study should be regarded as hypothesis-generating only at present.

The true incidence of sHLH in sepsis remains unknown. Recently, Kyriazopoulou et al. estimated the incidence of a MALS at around 4% in a large sepsis cohort.11 MALS was defined by a modified HScore (see further detail below), HPB and DIC or a combination of these, and was associated with a significant rise in early mortality. This further supports the existence of sHLH secondary to bacterial infection, although its true prevalence remains imprecise. Aside from the fact that human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-positive patients were excluded, no further information was provided on the source of sepsis, microbiology, or comorbidity to clarify the context of MALS. It shall therefore be of interest to see whether Anakinra reduces mortality in an ongoing RCT among a homogenous group of septic patients (based on serum ferritin >4420 ng/mL, lung infections, primary bacteraemia and acute cholangitis but without risk factors from biological treatment, immunodeficiency, stage IV malignancy or autoimmune disease (PROVIDE Trial, ClinicalTrials.gov NCT03332225)).

Differentiating sHLH from sepsis may be difficult. sHLH may be present in the absence of infection but cause an identical clinical presentation to septic shock (a ‘sepsis mimic’). In addition, sHLH can be triggered by infection or predispose to sepsis by virtue of its inherent immune dysfunction.3,10,32 Furthermore, both conditions can co-exist in the context of an underlying disease such as malignancy or an autoimmune condition. From a practical perspective, sHLH could, and probably should, be suspected in all critically ill patients with unexplained fever, cytopaenias and organ dysfunction, particularly those not responding to aggressive sepsis treatment.

Clinical and laboratory features in the context of critical care

Clinical presentation

The clinical picture of sHLH in a critical care patient is characterised by fever, organ dysfunction, lymphadenopathy and, potentially, hepato- and/or splenomegaly.1,3,33–39 An outline of possible clinical findings is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

| Clinical features | Additional information |

|---|---|

| Fever | |

| The cardinal sign of sHLH; almost always present at some stage of disease process Classically persistent and non-remitting, though recurrent fever pattern possible Typically unresponsive to antibiotics | |

| Organomegaly | |

| Lymphadenopathy | |

| Not consistently seen | |

| Splenomegaly or hepatomegaly | |

| More common in children | |

| Strong association with lymphoma or viral infection (esp. EBV) | |

| Splenomegaly is rarely observed in sepsis alone (unless antibiotics not commenced) | |

| Organ dysfunction | |

| Pulmonary manifestation | |

| Common; around 50% of patients; frequently ARDS requiring mechanical ventilation | |

| Carries poor prognosis | |

| Cardiovascular dysfunction | |

| From mild hypotension to profound shock; vasopressors/inotropes often required | |

| HLH-related cardiomyopathy described | |

| Successful use of ECLS as bridging therapy in sHLH has been described | |

| Renal impairment | |

| Well described; not consistently seen and frequently absent in early stages | |

| Majority with AKI will require renal replacement therapy | |

| Significant proportion of survivors with long-term chronic renal impairment | |

| Neurological dysfunction | |

| Wide spectrum of presentation | |

| From mild cognitive impairment to delirium, seizures and coma | |

| Might signify advanced stage sHLH | |

| Associated with poor prognosis | |

| Skin manifestations | |

| In up to 25% of a series of 775 adults with HLH | |

| Varied clinical picture: from rashes to erythroderma, petechiae and generalised purpura | |

AKI: acute kidney injury; ARDS: acute respiratory distress syndrome; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; ECLS: extra-corporeal life support; (s)HLH: (secondary) haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Laboratory features

A combination of cytopaenia and transaminitis in a patient with persistent fever not responding to initial treatment should trigger investigation for possible HLH. These features, alongside raised ferritin, elevated triglycerides and low fibrinogen, are highly suggestive of HLH. Typical laboratory features of sHLH are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

| Laboratory features | Likely derangement or pattern in sHLH | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| Routine biochemical markers | ||

| Liver biochemistry | Raised transaminases, alkaline phosphatase and LDH | Approx. 80% of patients |

| Fibrinogen | Low | Approx. 50% of patients |

| D-dimers | Elevated | Approx. 50% of patients |

| Routine clotting screen | Coagulopathy | Approx. 60% of patients |

| Serum triglycerides | Elevated | Approx. 70% of patients |

| C-reactive protein | May be raised or low | Low CRP levels in context of presumed bacterial sepsis should raise suspicion of sHLH if cardinal features of fever, cytopaenia and organ dysfunction are present |

| Cytopaenias | ||

| Full blood count | Usually cytopaenia in two or more lineages | Mainly related to cytokine-driven inflammation |

| Similar trends can be observed in sepsis but degree of cytopaenia tends to be milder (unless frank DIC present) | ||

| Anaemia and thrombocytopaenia | Approx. 80% of patients | |

| Request blood film to look for red cell fragments characteristic of TTP (differential diagnosis) | ||

| Leukopenia | Approx. 69% of cases | |

| Serum ferritin | ||

| Moderately to highly elevated | Consider HLH if >500 µg/L; increased probability >4000 µg/L; significantly increased specificity >10,000 µg/L; can reach levels >100,000 µg/L | |

| For comparison: Median levels in adults with bacterial sepsis and in surgical ICU patients are 300–600 µg/L and up to 1500 µg/L, respectively. | ||

| Haemophagocytosis | ||

| Bone marrow aspirate Lymphnode, spleen or liver biopsy | May or may not be present | Not necessary for diagnosis; not specific for HLH; often a late feature in sHLH |

CRP: C-reactive protein; DIC: disseminated intravascular coagulopathy; ICU: intensive care unit; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; (s)HLH: (secondary) haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; TTP: thrombotic thrombocytopaenic purpura.

Serum ferritin

Ferritin is a protein with numerous functions including iron storage, cell signalling and regulation of immune function. It is used as an inflammatory biomarker, released into serum in response to high levels of cytokines, hormones and oxidative stress. The differential diagnosis for hyperferritinaemia includes iron overload, liver dysfunction, chronic renal failure with secondary siderosis, malignancy, inflammatory disease, infection, sepsis and HLH, among others. Very high levels (>10,000 µg/L) are 96% specific and 90% sensitive for HLH in children.40 However, marked hyperferritinaemia is less specific for HLH in adults41,42 and must be used in combination with other criteria. Concomitant measurement of glycosylated ferritin may potentially increase the diagnostic specificity of ferritin.43 Trends in serum ferritin levels are useful in tracking progress, predicting short-term outcome and identifying rebound hyperinflammation.8,44

Haemophagocytosis

Haemophagocytosis refers to a process where macrophages engulf mature or immature blood cells in bone marrow or other reticuloendothelial organs. While this histological finding lends its name to HLH, it is neither pathognomonic nor is it required for HLH diagnosis.1 Of note, haemophagocytes may be systematically misclassified using the histological method, which lacks specificity and sensitivity as a test of haemophagocytosis.45 Within critical care, a degree of haemophagocytosis has been observed in 60% of patients with sepsis and thrombocytopaenia46 and in 65% of autopsies from patients with multiple organ dysfunction.47 If invasive diagnostic samples are obtained, pathologists should be alerted that HLH is being considered.

Specific immune markers and additional laboratory tests

A variety of potential specific immunological response markers for sHLH have been described, such as soluble interleukin 2 receptor (sIL-2R or sCD25), soluble CD163, NK cell activity and cytokine profiling.2,3,48 Given their prolonged turn-around times and lack of routine availability, none of these specialised immunological assays offer immediate diagnostic benefits in the critical care setting. Specialist advice from immunology/HLH multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) should be sought on which tests to use.

Clinical diagnosis

Diagnostic criteria

There are no universally agreed diagnostic criteria for sHLH. The two main existing scoring systems for HLH are summarised in Table 4.

Table 4.

HLH-2004 criteria and HScore.

| HLH-2004 criteria (Henter et al.49) |

HScore (Fardet et al.51) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | No. of points | Parameter | No. of points (criteria for scoring) |

| 1. Fever | 1 | 1. Temperature (℃) | 0 (<38.4), 33 (38.4–39.4) or 49 (>39.4) |

| 2. Splenomegaly | 1 | 2. Organomegaly | 0 (none), 23 (hepatomegaly or splenomegaly alone), 38 (both) |

| 3. Cytopaenia of ≥2 cell lines | 1 | 3. No of cytopaenias | 0 (1 lineage), 24 (2 lineages) or 34 (3 lineages) |

| Haemoglobin <90 g/L, platelets <100 × 109/L or neutrophil count <1 × 109/L | Haemoglobin <90 g/L, platelets <100 × 109/L or neutrophil count <1 × 109/L | ||

| 4. Hypertriglyceridaemia or hypofibrinogenaemia | 1 | 4. Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 0 (<1.5), 44 (1.5–4) or 64 (>4) |

| Fasting triglycerides ≥3.0 mmol/L or fibrinogen <1.5 g/L | 5. Fibrinogen (g/L) | 0 (>2.5) or 30 (≤2.5) | |

| 5. Haemophagocytosis demonstrated in bone marrow, spleen or lymph nodes | 1 | 6. Haemophagocytosis on bone marrow aspirate | 0 (no) or 35 (yes) |

| 6. Low or absent NK cell activity | 1 | 7. Ferritin (µg/L) | 0 (<2000), 35 (2000–6000) or 50 (>6000) |

| 7. Serum ferritin >500 µg/L | 1 | 8. Serum aspartate aminotransferase (ALT, IU/L) | 0 (<30) or 19 (≥30) |

| 8. Soluble CD25 (soluble interleukin-2 receptor) >2400 U/mL | 1 | 9. Known immunosuppression | 0 (no) or 18 (yes) |

| HIV positive or on long-term immunosuppressive therapy (i.e. glucocorticoids, ciclosporin, azathioprine) | |||

| Diagnosis of HLH if ≥5 out of 8 criteria positive (or molecular diagnosis) | HScore gives probability estimate for sHLH/MAS. Scores >169 reported to have 93% sensitivity and 86% specificity | ||

ALT: alanine transaminase; CD25: CD25 antigen (=soluble interleukin-2 receptor); HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MAS: macrophage activation syndrome; NK cell: natural killer cell; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Of note, neither has been validated in a critical care population and both have significant short-comings:

HLH-2004 is the diagnostic framework for fHLH, with diagnosis requiring the presence of five positive criteria from eight categories. Although frequently used for diagnosis in adult sHLH for lack of alternative criteria, HLH-2004 has only been validated in children and encompasses a variety of tests that are impractical in routine intensive care practice. Furthermore, turn-round times for specialised tests are usually slow, leading to concerns that the score does not become positive until very late in the clinical presentation, at which point patients may no longer be salvageable.49

The HScore is a simple bedside scoring system specifically developed for sHLH. It encompasses nine routine clinical and laboratory parameters, is easy to compute with an online calculator (http://saintantoine.aphp.fr/score/) and provides a probability score for the presence of sHLH. The HScore is based on a single-centre retrospective study with external validation for rheumatological patients.50,51 While it has not been fully validated as a diagnostic tool for sHLH in the critical care population, Kyriazopoulou et al. found a modified HScore to correlate with the presence of MALS and, by proxy, outcome in patients with sepsis.11

Diagnostic approach in critical care

We suggest the following pragmatic approach to diagnosis of sHLH in critical care patients:

sHLH should be suspected in any unwell patient with unexplained fever, cytopaenias (especially thrombocytopaenia) and organ dysfunction.

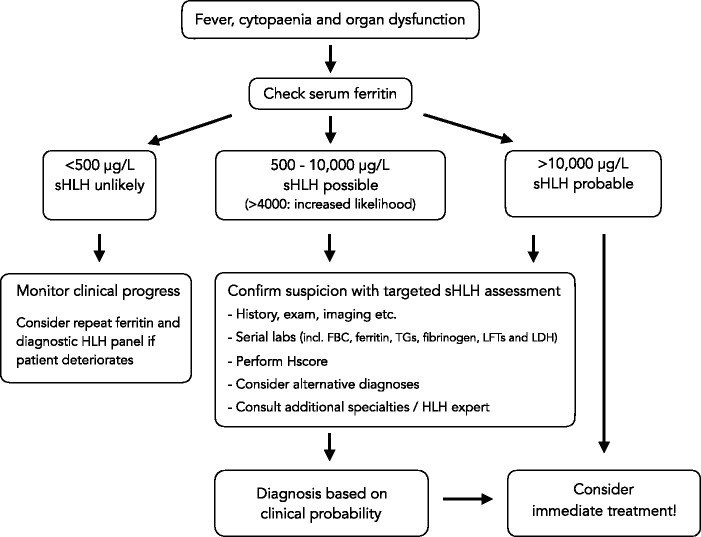

A serum ferritin level should be checked in these cases and, if elevated >500 µg/L or rapidly rising on serial measurements, should trigger further investigations.

Ferritin levels >4000 µg/L in sepsis significantly increase the likelihood of concomitant sHLH,11,52 while levels >10,000 µg/L are highly concerning and may indicate immediate need for treatment.

Additional work-up should include clinical assessment, laboratory tests and imaging to establish the probability of sHLH, and to identify potential triggers. Calculation of the HScore may aid in corroborating a clinical suspicion but time-critical treatment should not be withheld on the basis of insufficient HLH-2004 criteria or a low HScore.

A final diagnosis of sHLH hinges on clinical judgement and pattern recognition (see Figure 2). When possible, a dedicated HLH expert opinion should be sought (from a local or regional HLH expert or MDT) to advise on diagnosis and immediate treatment. Unfortunately, sHLH carries an exceedingly high mortality if advanced. Therefore, the risk of missing the diagnosis needs to be balanced against potential side-effects from aggressive immunosuppressive therapy. Early treatment should be considered if there is a reasonable clinical suspicion.

Figure 2.

Diagnostic approach for sHLH in critical care.

Source: Modified with permission from Carter et al., 2019.

FBC: full blood count; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; LFTs: liver function tests; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; TGs: triglycerides.

Suggested initial work-up

Table 5 provides an overview of diagnostic considerations in suspected sHLH on critical care.

Table 5.

Diagnostic work-up for sHLH in critical care.

| Diagnostic evaluation |

|---|

| History |

| Including travel/drug/sexual/family history etc. |

| Examination |

| Lymphadenopathy, hepato-splenomegaly, rashes, bleeding, signs of organ dysfunction |

| Initial laboratory tests |

| Full blood count including differential/blood film |

| Routine renal biochemistry and electrolytes |

| Serum ferritin, triglycerides and C-reactive protein |

| Liver function tests, including AST, ALT, GTT, total bilirubin and LDH |

| Coagulation screen, including PT, aPTT, fibrinogen, D-dimer |

| ECG, Echocardiogram |

| Routine imaging |

| CXR |

| Ultrasound scan: abdomen or as clinically indicated |

| CT neck, chest, abdomen, pelvis |

| Infectious diseases work-up |

| Infectious disease +/− tropical disease consult |

| Cultures from blood, sputum, urine, CSF and other body fluids as clinically indicated |

| Serum ‘save’ sample (prior to blood products/IVIG) for future testing |

| Respiratory virus screen (combined nose/throat swab) |

| HIV screen, hepatitis virology screen |

| EBV, CMV serology and PCR (other herpesvirus PCR may be appropriate in paediatric or immunocompromised patients) |

| Parvovirus B19 serology |

| Parasitology (blood film for malaria, serology for toxoplasma and leishmaniasis) |

| Fungal screen cultures (BD glucan, PCP from deep respiratory samples) |

| Consider tuberculosis (histopathology, TB cultures +/− TB Gen Xpert of appropriate tissues/fluids as clinically indicated; immunological tests do not have sufficient validity in this setting) |

| Additional tests in immunosuppression |

| Malignancy work-up |

| Haematology consult |

| Bone marrow aspirate/trephine (haemophagocytosis? Leishmania amastigotes?) may need repeat sampling |

| Additional tests as recommended (steroids might mask lymphoma diagnosis) |

| Autoimmune work-up |

| Rheumatology consult |

| Autoimmune screen |

| Additional immunological profiling |

| Other/miscellaneous |

| Cerebrospinal fluid analysis (abnormal in 50%) |

| MRI brain |

| PET scan (infection, malignancy) |

| Tissue sampling (lymphnodes, spleen biopsy, etc.) |

| Genetic testing (no acute role; as advised by HLH expert) |

aPTT: activated partial thromboplastin time; ALT: alanine aminotransferase; AST: aspartate aminotransferase; CMV: cytomegalovirus; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; CT: computed tomography; CXR: chest radiograph; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; ECG: electrocardiogram; GTT: gamma glutamyl transferase; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IVIG: intravenous immunoglobulin; LDH: lactate dehydrogenase; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; PCP: pneumocystis pneumonitis; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; PET: positron emission tomography; PT: prothrombin time; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis; TB: tuberculosis.

Targeted imaging, including ultrasound and cross-sectional radiology are important to establish underlying triggers and alternative causes for the clinical presentation; CT scanning of chest, abdomen and pelvis may be considered for relative ease of availability and the broad diagnostic scope. Specialty consultations from infectious diseases, rheumatology or haematology should be sought as clinically indicated; these may inform further specialised testing (see Tables 3 and 5). Of note, repeat sampling may be required to identify underlying malignancy (such as lymphoma diagnosis masked by steroids) or occult infection (unusual pathogens). Bone marrow examination, additional tissue sampling, positron emission tomography (PET) scanning and other investigations (such as cell-free DNA for lymphoma diagnosis) may be helpful.

Treatment approach in critical care

There are no randomised trials to guide treatment of sHLH in adults. Most treatment regimens have been extrapolated from the intensive immunosuppressive treatment of fHLH. Hence, decision to initiate therapy and choice of agents depend largely on expert opinion and clinical experience. Based on available evidence, we suggest that the general principles for treatment of adult onset sHLH treatment on critical care should revolve around:

Early diagnosis

Supportive care and multiple organ support

Rapid initiation of specific HLH therapy to control cytokine storm

Identification and treatment of any underlying trigger

Early involvement of an HLH expert or HLH MDT.

Specific sHLH treatment involves aggressive suppression of the hyperinflammatory response and cytokine storm. Tissue collection prior to treatment may be considered in stable patients but treatment should not be delayed if the patient is acute unwell or deteriorating. A suggested treatment approach on critical care is provided in Table 6. Importantly, this needs to be modified for individual patients, depending on the underlying pathology and clinical context.2,53 The complexity of sHLH diagnosis and the potential co-existence of multiple underlying pathophysiological processes emphasise the need for a nuanced treatment approach delivered by multidisciplinary collaboration.

Table 6.

Suggested treatment approach for sHLH in critical care.

| Timing | Choice of agent | Dosing | Additional considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immediate/first-line | |||

| Consider combination therapy | Anakinra | 1–2 mg/kg/dose (max 100 mg) Q12h SC (could consider IV); can increase to max 8 mg/kg/day | Preferred over steroids if the trigger for sHLH is not clear (does not preclude lymphoma diagnosis); consider high starting dose and tapering regimen; IV use not licensed but may have favourable absorption characteristics in critically ill patients |

| Methylprednisolone | 30 mg/kg/dose (max 1 g) IV Q24h for 3 days | More readily available than Anakinra; may mask lymphoma diagnosis; dexamethasone is a suitable alternative in CNS involvement | |

| Intravenous immunoglobulin | 2 g/kg/dose over 1–2 days | Consider repeat dose after 14 days (limited half-life) | |

| Second-line | |||

| Etoposide | As advised by haematologist | Particularly for malignancy-related sHLH. Dose reduction required in renal in liver impairment | |

| Maintenance/relapse prevention | |||

| Ciclosporin | 1–2 mg/kg/day enterally (preferred) or IV, then titrated to target levels | May be considered as second-line treatment in some patients | |

| Parallel treatment considerations | |||

| Antimicrobial therapy | Including intracellular and atypical organisms | ||

| Rituximab | EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disease | ||

| HAART | HIV-associated sHLH | ||

| Targeted cancer chemo and biological therapy | As guided by haematologist | ||

CNS: central nervous system; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; HAART: highly active anti-retroviral therapy; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IV: intravenously; SC: subcutaneously; sHLH: secondary haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.

Steroids are usually the mainstay of initial immunosuppression. If already in use, ‘sepsis-dose’ steroids such as hydrocortisone may be converted to a course of high-dose pulsed methylprednisolone. Dexamethasone is a suitable alternative and may be superior if central nervous system (CNS) involvement is suspected (around one-third of patients).

There are concerns regarding the primary use of steroids when the HLH-driver has not yet been identified. Some lymphomas are initially very steroid-sensitive, so starting treatment with high-dose steroids prior to taking all the required biopsies or performing a PET scan risks masking the lymphoma diagnosis. Conversely, a delay in definitive treatment is again associated with poor outcome. If available, therefore, there is a strong argument for using Anakinra as first-line treatment where diagnostic uncertainty exists. Anakinra is a recombinant IL-1 receptor antagonist and very effective in controlling the initial cytokine storm of sHLH.8 It is well tolerated, has a favourable side-effect profile and is therefore increasingly being considered as an early treatment modality in sHLH. The financial cost of Anakinra is moderate, yet local availability for emergency use on critical care may be limited. Anakinra is usually given subcutaneously (SC) but can be given intravenously, which might be preferable in unwell ICU patients with unclear SC absorption characteristics. A higher than usual starting dose with a plan for gradual weaning should be considered in very sick patients. Due to its short half-life, Anakinra may be administered in split doses or via continuous infusion.

HLH is a recognised indication for intravenous immunoglobulin.54 A repeat dose should be considered after 2 weeks due to the limited half-life. Plasma exchange to remove cytokines is an alternative but has little evidence in adults.1,2

Etoposide is a cytotoxic agent with particular activity against macrophages and cytotoxic T cells. It should be considered a third-line treatment for refractory sHLH cases, particularly in EBV-driven disease and malignancy. Caution is advised in severe renal and liver impairment, and dose reductions are advised to mitigate haematological toxicity.1,7,32 Intrathecal methotrexate may be added with progressive CNS involvement.1,8 Ciclosporin has a potential role in relapse prevention but is associated with neurotoxicity, including posterior reversible encephalopathy. This may be difficult to distinguish from HLH with CNS involvement.8

Aside from routine antibacterial management, specific therapies for intracellular diseases such as tuberculosis, rickettsial disease and leishmaniasis may be crucial.2

Highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has improved the prognosis for HIV-related HLH.2 HAART may cure sHLH in the context of primary HIV infection and may ameliorate mild to moderate sHLH in context of cytomegalovirus or human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) viraemia by virtue of immune reconstitution. However, it is unlikely to be effective in fulminant AIDS-related sHLH. In the latter context, additional pathology such as HHV-8-associated lymphoproliferative disorder should be considered as this may benefit from immediate anti-cytokine treatment (IL-6 inhibition) and rituximab.55 Rituximab also plays an important role in EBV-driven lymphoproliferative disorder.56

Further novel therapies including biological agents are on the horizon but evidence so far is scarce.1,8

Salvage therapy with haematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) may rarely be considered in selected cases of sHLH, who survive the initial critical illness but suffer from relapsing disease, CNS involvement or haematological malignancy.1,2,22 In the UK, sHLH is an accepted indication for HSCT under the ‘transplant for rare diseases’ category, and patients should be discussed with an experienced transplant centre.

Prognosis

sHLH carries a high acute mortality of around 40% for all groups combined.1 Malignancy-associated HLH has a particularly poor prognosis with acute mortality exceeding 80% and 5-year survival of <15%.8,22 In ICU patients, the published hospital mortality rates range from 52%7 to 68%.6 The presence of shock or severe thrombocytopaenia indicates increased risk.7 Of interest, the maximum serum ferritin elevation concentration is directly correlated with an increased mortality risk, while a rapid fall in serum ferritin levels in response to treatment is associated with a more favourable short-term outcome.8,44

Future perspectives

Prospective research on sHLH in critical care is still in its infancy. The Hellenic Sepsis Study Group is currently conducting a randomised controlled trial (PROVIDE Trial) on the use of Anakinra in patients with high ferritin, sepsis, liver dysfunction and DIC.57 However, the wider problem remains that sHLH in the context of sepsis essentially constitutes a syndrome within a syndrome. Experience from existing critical care research indicates that large patient heterogeneity often reduces the ability to demonstrate meaningful changes in clinical outcomes within randomised controlled studies.

In addition to research, there is clearly a need for better understanding of sHLH as a clinical phenomenon and for a systematic approach to patient identification, diagnosis and management across different specialties. This is facilitated by local or regional HLH MDTs, which would ideally include representation from rheumatology, haematology, infectious disease and critical care, with additional specialties as needed. Increasingly, HLH MDTs are being established within both paediatric and adult settings.53 Within the UK, a national cross-specialty collaboration on HLH is being developed (HASC; HLH across specialty collaboration). This draws upon the specialties above with additional clinical input from immunology, genetics, virology, transplant specialists, etc. Future work will focus on establishing a national HLH register in order to capture clinical data and create a comprehensive biobank, following the footsteps of countries such as Germany (hlh-registry.org) and the USA (histiocytesociety.org). The initial aims are to characterise clinical phenotypes of sHLH, identify potential genetic variants in adult sHLH and explore avenues for clinical research.

Conclusion

sHLH is not a disease in itself but rather a clinical syndrome of extreme hyperinflammation, which is triggered by infection, auto-immunity or malignancy, among others. sHLH can lead to rapidly life-threatening organ dysfunction and is likely underdiagnosed in critical care. It should be suspected and actively investigated in any unwell patient with unexplained fever, cytopaenias, progressive organ dysfunction and failure to respond to intensive infection management. Treatment revolves around high-quality supportive care, early anti-inflammatory and immunosuppressive therapy and identification and treatment of any precipitating pathology. In a patient with undifferentiated rapidly progressing organ failure, or if the presumed sepsis diagnosis does not quite ‘feel’ right or respond appropriately, think, could this be HLH?

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Kris Bauchmuller https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9648-1328 Rachel Tattersall https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1087-6546 Christopher McNamara https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8581-2790 Mervyn Singer https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1042-6350 Stephen J Brett https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4545-8413

References

- 1.Ramos-Casals M, Brito-Zeron P, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Adult haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet 2014; 383: 1503–1516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.La Rosee P, Horne A, Hines M, et al. Recommendations for the management of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Blood 2019; 133(23): 2465–2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machowicz R, Janka G, Wiktor-Jedrzejczak W. Similar but not the same: Differential diagnosis of HLH and sepsis. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2017; 114: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park HS, Kim DY, Lee JH, et al. Clinical features of adult patients with secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis from causes other than lymphoma: An analysis of treatment outcome and prognostic factors. Ann Hematol 2012; 91: 897–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tothova Z, Berliner N. Hemophagocytic syndrome and critical illness: New insights into diagnosis and management. J Intensive Care Med 2015; 30: 401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barba T, Maucort-Boulch D, Iwaz J, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in intensive care unit: A 71-Case Strobe-Compliant Retrospective Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2015; 94: e2318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buyse S, Teixeira L, Galicier L, et al. Critical care management of patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Intensive Care Med 2010; 36: 1695–1702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carter SJ, Tattersall RS, Ramanan AV. Macrophage activation syndrome in adults: Recent advances in pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2019; 58: 5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carcillo JA, Simon DW, Podd BS. How we manage hyperferritinemic sepsis-related multiple organ dysfunction syndrome/macrophage activation syndrome/secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis histiocytosis. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2015; 16: 598–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Farkas J. Sepsis 4.0: Understanding sepsis-HLH overlap syndrome. PulmCrit 2016. Available at: https://emcrit.org/pulmcrit/sepsis-hlh-overlap-syndrome-shlhos/. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kyriazopoulou E, Leventogiannis K, Norrby-Teglund A, et al. Macrophage activation-like syndrome: An immunological entity associated with rapid progression to death in sepsis. BMC Med 2017; 15: 172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shakoory B, Carcillo JA, Chatham WW, et al. Interleukin-1 receptor blockade is associated with reduced mortality in sepsis patients with features of macrophage activation syndrome: Reanalysis of a prior phase III trial. Crit Care Med 2016; 44: 275–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cetica V, Sieni E, Pende D, et al. Genetic predisposition to hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: Report on 500 patients from the Italian registry. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2016; 137: 188–196.e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang K, Jordan MB, Marsh RA, et al. Hypomorphic mutations in PRF1, MUNC13-4, and STXBP2 are associated with adult-onset familial HLH. Blood 2011; 118: 5794–5798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beutel G, Wiesner O, Eder M, et al. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome as a major contributor to death in patients with 2009 influenza A (H1N1) infection. Crit Care 2011; 15: R80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brisse E, Wouters CH, Andrei G, et al. How viruses contribute to the pathogenesis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Front Immunol 2017; 8: 1102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harms PW, Schmidt LA, Smith LB, et al. Autopsy findings in eight patients with fatal H1N1 influenza. Am J Clin Pathol 2010; 134: 27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh SM, Chang SC. Insufficient perforin expression in CD8+ T cells in response to hemagglutinin from avian influenza (H5N1) virus. J Immunol 2006; 176: 4530–4533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rouphael NG, Talati NJ, Vaughan C, et al. Infections associated with haemophagocytic syndrome. Lancet Infect Dis 2007; 7: 814–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Worth AJ, Houldcroft CJ, Booth C. Severe Epstein-Barr virus infection in primary immunodeficiency and the normal host. Br J Haematol 2016; 175: 559–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malik AN, John L, Bruceson AD, et al. Changing pattern of visceral leishmaniasis, United Kingdom, 1985-2004. Emerg Infect Dis 2006; 12: 1257–1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Daver N, McClain K, Allen CE, et al. A consensus review on malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Cancer 2017; 123: 3229–3240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delavigne K, Berard E, Bertoli S, et al. Hemophagocytic syndrome in patients with acute myeloid leukemia undergoing intensive chemotherapy. Haematologica 2014; 99: 474–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Machaczka M, Vaktnas J, Klimkowska M, et al. Malignancy-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: A retrospective population-based analysis from a single center. Leukemia Lymphoma 2011; 52: 613–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Asano T, Kogawa K, Morimoto A, et al. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in children: A nationwide survey in Japan. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2012; 59: 110–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandler R, Tattersall RS, Snowden J. Haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) following allogeneic haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) – Time to reappraise with modern diagnostic and treatment strategies? 2019 Aug 27. doi: 10.1038/s41409-019-0637-7. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Titov A, Petukhov A, Staliarova A, et al. The biological basis and clinical symptoms of CAR-T therapy-associated toxicities. Cell Death Dis 2018; 9: 897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukaya S, Yasuda S, Hashimoto T, et al. Clinical features of haemophagocytic syndrome in patients with systemic autoimmune diseases: Analysis of 30 cases. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2008; 47: 1686–1691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 2016; 315: 801–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davies R, O'Dea K, Gordon A. Immune therapy in sepsis: Are we ready to try again? J Intensive Care Soc 2018; 19: 326–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hotchkiss RS, Monneret G, Payen D. Sepsis-induced immunosuppression: From cellular dysfunctions to immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol 2013; 13: 862–874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raschke RA, Garcia-Orr R. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis: A potentially underrecognized association with systemic inflammatory response syndrome, severe sepsis, and septic shock in adults. Chest 2011; 140: 933–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Arismendi-Morillo GJ, Briceno-Garcia AE, Romero-Amaro ZR, et al. Acute non-specific splenitis as indicator of systemic infection. Assessment of 71 autopsy cases. Invest Clin 2004; 45: 131–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aulagnon F, Lapidus N, Canet E, et al. Acute kidney injury in adults with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Kidney Dis 2015; 65: 851–859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cashen K, Chu RL, Klein J, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation outcomes in children with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Perfusion 2017; 32: 151–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Feig JA, Cina SJ. Evaluation of characteristics associated with acute splenitis (septic spleen) as markers of systemic infection. Arch Pathol Lab Med 2001; 125: 888–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kim MM, Yum MS, Choi HW, et al. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement is a critical prognostic factor for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Korean J Hematol 2012; 47: 273–280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saites VA, Hadler R, Gutsche JT, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Am J Case Rep 2016; 17: 686–689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seguin A, Galicier L, Boutboul D, et al. Pulmonary involvement in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Chest 2016; 149: 1294–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allen CE, Yu X, Kozinetz CA, et al. Highly elevated ferritin levels and the diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2008; 50: 1227–1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sackett K, Cunderlik M, Sahni N, et al. Extreme hyperferritinemia: Causes and impact on diagnostic reasoning. Am J Clin Pathol 2016; 145: 646–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schram AM, Campigotto F, Mullally A, et al. Marked hyperferritinemia does not predict for HLH in the adult population. Blood 2015; 125: 1548–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fardet L, Coppo P, Kettaneh A, et al. Low glycosylated ferritin, a good marker for the diagnosis of hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheum 2008; 58: 1521–1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin TF, Ferlic-Stark LL, Allen CE, et al. Rate of decline of ferritin in patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis as a prognostic variable for mortality. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011; 56: 154–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gars E, Purington N, Scott G, et al. Bone marrow histomorphological criteria can accurately diagnose hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Haematologica 2018; 103: 1635–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Francois B, Trimoreau F, Vignon P, et al. Thrombocytopenia in the sepsis syndrome: Role of hemophagocytosis and macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Am J Med 1997; 103: 114–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Strauss R, Neureiter D, Westenburger B, et al. Multifactorial risk analysis of bone marrow histiocytic hyperplasia with hemophagocytosis in critically ill medical patients–A postmortem clinicopathologic analysis. Crit Care Med 2004; 32: 1316–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.von Muller L, Klemm A, Durmus N, et al. Cellular immunity and active human cytomegalovirus infection in patients with septic shock. J Infect Dis 2007; 196: 1288–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Henter JI, Horne A, Arico M, et al. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007; 48: 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Batu ED, Erden A, Seyhoglu E, et al. Assessment of the HScore for reactive haemophagocytic syndrome in patients with rheumatic diseases. Scand J Rheumatol 2017; 46: 44–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fardet L, Galicier L, Lambotte O, et al. Development and validation of the HScore, a score for the diagnosis of reactive hemophagocytic syndrome. Arthritis Rheumatol 2014; 66: 2613–2620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Saeed H, Woods RR, Lester J, et al. Evaluating the optimal serum ferritin level to identify hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in the critical care setting. Int J Hematol 2015; 102: 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Halyabar O, Chang MH, Schoettler ML, et al. Calm in the midst of cytokine storm: A collaborative approach to the diagnosis and treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis and macrophage activation syndrome. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2019; 17: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.NHS England. Immunoglobulin Commissioning Guidelines V1.0 Dec 2018. 2018.

- 55.Rokx C, Rijnders BJ, van Laar JA. Treatment of multicentric Castleman’s disease in HIV-1 infected and uninfected patients: A systematic review. Neth J Med 2015; 73: 202–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chellapandian D, Das R, Zelley K, et al. Treatment of Epstein Barr virus-induced haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis with rituximab-containing chemo-immunotherapeutic regimens. Br J Haematol 2013; 162: 376–382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karakike E, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ. Macrophage activation-like syndrome: A distinct entity leading to early death in sepsis. Front Immunol 2019; 10: 55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]