Abstract

Adverse events related to long-term use of bisphosphonates have raised interest in temporary drug discontinuation. Trends in bisphosphonate discontinuation and restart, as well factors associated with these decisions, are not fully understood at a population level. We investigated temporal trends of bisphosphonate discontinuation from 2010 to 2015 and identified factors associated with discontinuation and restart of osteoporosis therapy. Our cohort consisted of long-term bisphosphonate users identified from 2010 to 2015 Medicare data. We defined discontinuation as ≥12 months without bisphosphonate prescription claims. We used conditional logistic regression to compare factors associated with alendronate discontinuation or osteoporosis therapy restart in the 120-day period preceding discontinuation or restart referent to the 120-day preceding control periods. Among 73,800 long-term bisphosphonate users, 59,251 (80.3%) used alendronate, 6806 (9.2%) risedronate, and 7743 (10.5%) zoledronic acid, exclusively. Overall, 26,281 (35.6%) discontinued bisphosphonates for at least 12 months. Discontinuation of bisphosphonates increased from 1.7% in 2010, reaching a peak of 14% in 2012 with levels plateauing through 2015. The factors most strongly associated with discontinuation of alendronate were: benzodiazepine prescription (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 2.5; 95% confidence interval [CI] 2.1, 3.0), having a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scan (aOR = 1.8; 95% CI 1.7, 2.0), and skilled nursing facility care utilization (aOR = 1.8; 95% CI 1.6, 2.1). The factors most strongly associated with restart of osteoporosis therapy were: having a DXA scan (aOR = 9.9; 95% CI 7.7, 12.6), sustaining a fragility fracture (aOR = 2.8; 95% CI 1.8, 4.5), and an osteoporosis or osteopenia diagnosis (aOR = 2.5; 95% CI 2.0, 3.1). Our national evaluation of bisphosphonate discontinuation showed that an increasing proportion of patients on long-term bisphosphonate therapy discontinue medications. The factors associated with discontinuation of alendronate were primarily related to worsening of overall health status, whereas traditional factors associated with worsening bone health were associated with restarting osteoporosis medication.

Keywords: ALENDRONATE, BISPHOSPHONATES, MEDICATION DISCONTINUATION, MEDICATION RESTART, OSTEOPOROSIS

Introduction

Bisphosphonates are widely prescribed for the treatment of osteoporosis, of which alendronate is the most commonly prescribed.(1) Given their high skeletal retention, prolonged suppression of bone remodeling continues to occur after discontinuation.(2) This unique feature of bisphosphonates, including alendronate, is likely the main mechanism that mediates the observed sustained lumbar spine bone mineral density (BMD) found in the alendronate withdrawal arm of the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX) clinical trial.(3)

Over the last decade, there has been a significant decline in the use of bisphosphonates.(1,4) This decline is related, in part, to the fear of rare adverse events, namely osteonecrosis of the jaw (ONJ) and atypical femoral fractures. These possible side effects were highlighted by US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announcements in 2005 and 2007, respectively.(5) In addition, atypical femoral fractures may be related to the prolonged antiresorptive effects of bisphosphonates,(6) although there is less compelling evidence that ONJ is duration dependent. In 2016, a Task Force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research (ASBMR) advocated a “drug holiday” after 5 years of continuous bisphosphonate therapy.(7) More than 80% of US physicians consider a drug holiday after long-term bisphosphonate treatment.(8) Retrospective analyses and a systematic review showed that a drug holiday of 12 months in patients with 2 years or more of previous bisphosphonate exposure might be safely executed without a subsequent increase in fractures.(9-11) In contrast, bisphosphonate discontinuation of more than 3 years has been associated with an increased rate of hip fractures.(12) However, the appropriate timing and duration of a drug holiday for each patient remains controversial.

Although the effects of bisphosphonates are long-lasting and a prolonged drug holiday may be warranted in some patients, osteoporosis is a chronic condition and resumption of an osteoporosis therapy is likely to be necessary for most people. The optimal duration of a bisphosphonate drug holiday may likely be influenced by a number of variables, including baseline fracture risk, as well as changes in BMD and bone turnover markers (BTMs), fractures, altered risk factors, or changes in comorbidities that occur during the holiday.(7,13) However, the patient and provider factors associated with the suspension of bisphosphonates and restart of osteoporosis medications are not fully known at a population-level and might vary based on a number of factors including route of administration (ie, intravenous versus oral bisphosphonates) or drug affinity to bone. A previous analysis of Medicare data from 2006 to 2010 reported that baseline characteristics of patients (sex, race, income, number of visits) at the time of bisphosphonate treatment initiation were only weakly associated with subsequent discontinuation.(14) These weak associations may be explained by the presence of more relevant events, closer to the time of discontinuation, which presumably could have precipitated the decision to stop therapy. Indeed, circumstances occurring at follow-up time points (eg, results of a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry [DXA], high drug co-pays, or experiencing adverse events) were more predictive of medication adherence than factors measured at therapy initiation in one study.(14)

Previous analyses included patients who discontinued osteoporosis medication for a short period (90 days), which may not truly represent an intentional drug discontinuation. To our knowledge, past studies also have not investigated reasons associated with the restart of osteoporosis therapy. Thus, a better understanding of patient and provider variables immediately preceding bisphosphonate long-term discontinuation and restart is needed to guide osteoporosis treatment strategies and management with a personalized medicine approach. Although retrospective cohort designs can comprehensively assess the reasons for discontinuation/restart of therapy, they lack the ability to control personal characteristics that can confound these associations. In contrast, a case-crossover is a time-focused design in which each case serves as its own control across different time periods, allowing for a unique analytical approach to investigate factors that may precipitate bisphosphonate discontinuation and subsequent restarting therapy, thereby providing better control for temporally associated confounding than other study designs.(15) The aims of the present study were to: 1) describe the temporal trends of bisphosphonate discontinuation among women in a national Medicare population, and 2) evaluate patient and provider factors associated with discontinuation of alendronate and restart of any osteoporosis medication using a case-crossover design study.

Materials and Methods

Study design overview

To describe the temporal trends of bisphosphonate discontinuation from 2010 to 2015 (January 1, 2010 to December 31, 2014), we created a retrospective cohort derived from all women with fee-for-service Medicare coverage receiving any bisphosphonate therapy from 2006 to 2012. Data derived from the Chronic Disease Warehouse included information on demographics; insurance coverage; claims for inpatient, outpatient, skilled nursing facility, noninstitutional provider, home health, hospice, durable medical equipment services; and claims for prescription drugs. We identified long-term adherent bisphosphonate women users based on proportion of days covered (PDC)(16) ≥80% for at least 3 continuous years who then were at risk to subsequently stop therapy. The PDC considers the days that are covered by a prescription and represents a measure of drug adherence based on prescription pharmacy claims. A PDC of 80% reflects a patient likely taking their medication most of the time. This threshold of PDC has been shown to be sufficient to achieve the potential clinical benefit of oral bisphosphonates(17) for fracture risk reduction.(18) We restricted our analyses to only highly adherent patients in the first 3 years of treatment to mirror the pattern of drug utilization typical for patients in the pivotal osteoporosis clinical trials and to focus on those patients who might have preplanned and/or physician-advised drug discontinuation given that duration of exposure with good adherence.(17)

We analyzed temporal trends of bisphosphonate discontinuation according to calendar time in 6-month intervals starting January 1, 2010 through December 31, 2014. To identify time-varying factors associated with discontinuation of alendronate and restart of that or any other osteoporosis therapy, we conducted a case-crossover analysis. All study procedures were approved by the institutional review board of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Bisphosphonate discontinuation temporal trend analysis

We conducted a retrospective analysis on temporal trends of drug discontinuation in the US using national Medicare data from 2010 to 2015. Eligible subjects for the cohort included women ≥65 years, with fee-for-service Medicare beneficiaries, who lived in the US and who were prescribed any bisphosphonate(s) for at least 3 years with high adherence based on the proportion of days covered (PDC).(16) PDC was measured from the time of first BP use and was estimated beginning at day 1096 (3 years) after BP initiation. We defined start of follow-up (index date) as the first day on or after day 1096 that PDC exceeded 80%.

The definition of discontinuation was subsequent cessation of bisphosphonates for a period of ≥12 months. We restricted the analysis to alendronate, risedronate, and zoledronic acid users. A priori, we excluded ibandronate because of the small amount of ibandronate users for both oral and intravenous routes of administration. We required women in the cohort to have no evidence of malignancy (diagnosis codes or treatment and ignoring nonmelanoma skin cancer), diagnosis of Paget’s disease, or osteogenesis imperfecta during all available baseline data (from first eligible coverage start date), and who did not have previous systemic hormone therapy. Women were excluded if they had prescriptions for other osteoporosis drugs (eg, raloxifene, teriparatide, calcitonin, or denosumab) or use of bisphosphonates not approved in US for treatment of osteoporosis (eg, tiludronate, pamidronate, and etidronate) in the 365 days before the index date.

Case-crossover design

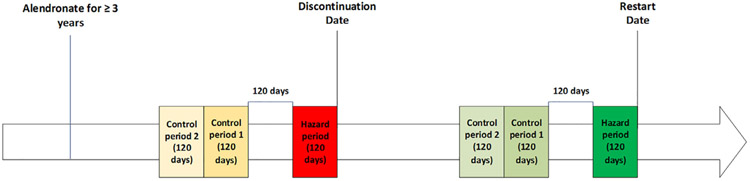

We restricted our case-crossover study design to women who took alendronate, the most frequently prescribed oral bisphosphonate in the US and internationally, in order to increase the homogeneity of the analysis.(1) Indeed, the factors that contribute to drug discontinuations might be different for zoledronic acid (which is characterized by intravenous administration) and risedronate (a less potent bisphosphonate than alendronate). In this design, every patient contributed one hazard period and two control periods to each outcome (restart and/or discontinuation). The case-crossover design schema is depicted in Fig. 1. We assessed factors measured during the 120-day hazard period before alendronate discontinuation and two consecutive control periods of 120 days before discontinuation. The hazard period was anchored at the time of alendronate discontinuation (day −120 to 0) and the two consecutive control periods were separated from the hazard period by a 120-day gap.

Fig.1.

Case-crossover design for identifying factors associated with alendronate discontinuation and restart of osteoporosis medication (restart cohort is a subgroup of the discontinuation cohort).

The approach for assessment of factors associated with the restart of any osteoporosis medication was similar, only that analysis was conducted on the subgroup of women that had previously discontinued alendronate. In the restart case-crossover analysis, the time frame without any osteoporosis medication before restarting had to be at least 480 days, to be consistent with expectations regarding the minimum length of a drug holiday. This design feature of the analysis thus allowed for four 120-day windows (two control periods, one gap period, and one hazard period). We conducted sensitivity analysis widening the hazard period from days −90 to +30. In this sensitivity analysis, the gap was widened to 150 days and extended from day −91 to day −240.

We used multivariable conditional logistic regression to compare factors associated with alendronate discontinuation and osteoporosis medication restart in the hazard period referent to the preceding control periods. The factors included in the multivariable analysis for both discontinuation cohort and restart cohort were the following: diagnosis of osteoporosis or osteopenia, DXA, measurement of BTMs (osteocalcin, phosphatase alkaline, serum procollagen type I N-terminal propeptide, serum procollagen I carboxyterminal propeptide, serum or urine collagen type I cross-linked N-terminal telopeptide A, serum or urine hydroxyproline, serum or urine collagen type I cross-linked C-terminal telopeptide, tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase), case-qualifying fragility fracture, fall, at least one visit with an osteoporosis specialist (rheumatology or endocrinology), number of unique days with at least one physician visit (categorized based on distribution of the data [eg, tertiles]), any emergency room visit, hospitalization due to stroke, myocardial infarction, cardiovascular disease, or chronic heart disease (ICD 433.x1, 434.x1, 436; 410.x1), hospitalization for noncardiovascular reason, number of hospitalization days (categorized based on distribution of the data [eg, tertiles]), new diagnosis of Alzheimer’s or other dementia, new diagnosis of depression or anxiety, Charlson comorbidity index(19) and any skilled nursing facility (SNF) care. We also included use of medications that affect fracture risk as potential factors associated with discontinuation/restart (alpha blockers, anticholinergic antihistamines, antipsychotics, barbiturates, benzodiazepines, beta blockers, muscle relaxants, nonbenzodiazepines or nonbenzodiazepine GABA receptor agonists, opioids, oral glucocorticoids, proton pump inhibitors, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, tricyclic antidepressants, vasodilators). We identified these medications using the criterion of at least one claim for a prescription filled in Medicare Part D data during the relevant time window. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC, USA; Enterprise Guide v4.3).

Results

We identified 107,633 adherent long-term bisphosphonate users (Fig. 2). We only included the 83,973 patients with prescriptions for a single bisphosphonate (ever) and excluded those who switched between bisphosphonate medications. The final cohort was composed of 73,800 women, of which 59,251 (80.3%) used alendronate exclusively, 6806 (9.2%) used risedronate exclusively, and 7743 (10.5%) used zoledronic acid exclusively. The median (IQR) follow-up was 2.8 (1.5–4.1), 2.3 (1.1–4.0), and 2.2 (1.3–3.3) years, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Algorithm for selection of the eligible women in the final cohort. BP = bisphosphonate; OP = osteoporosis; PDC = proportion of days covered.

Temporal trends of bisphosphonate discontinuation

Overall, 26,281 (35.6%) women discontinued their respective bisphosphonate for at least 12 months. Long-term bisphosphonate users who underwent a drug discontinuation increased from 1.7% in 2010, reaching a peak of 14.0% in 2012, and continuing in a relatively stable to slightly declining fashion thereafter (Fig. 3). Discontinuation frequency varied by bisphosphonate: 20,455 (34.5%) for alendronate users, 2388 (35.1%) for risedronate users, and 3438 (44.4%) for zoledronic acid users, with a median follow-up after bisphosphonate discontinuation (IQR) of 1.4 (0.6–2.5), 1.6 (0.7–2.6), and 1.0 (0.4–1.8), respectively.

Fig. 3.

Temporal trends of bisphosphonate discontinuation in US Medicare women by calendar year.

Among women who discontinued their drug for ≥12 months, 87.6% (23,041) did not restart osteoporosis therapy, whereas 12.3% (3240) restarted an osteoporosis therapy during follow-up. Characteristics of the analyzed population are represented in Table 1 (stratified by patients who underwent drug discontinuation versus those who did not) and Table 2 (stratified by whether individuals eventually restarted any osteoporosis medication versus those who did not). For the many factors that were measured at baseline, we found no differences in the frequency of drug discontinuation, race/ethnicity, previous DXA scans, glucocorticoid use, or fragility fractures between those who stopped versus those who restarted, nor between beneficiaries who used different oral bisphosphonates (eg, alendronate 34.5% discontinuation rate versus risedronate 35.1% discontinuation rate). However, beneficiaries who used zoledronic acid were more likely to discontinue the drug compared with oral bisphosphonate (zoledronic acid 44.4%). Furthermore, women who used zoledronic acid were more likely to be white, be on glucocorticoids, and have had a previous DXA scan or a previous fragility fracture compared with those on oral bisphosphonates. In addition, women who discontinued zoledronic acid were more likely to restart the treatment compared with oral bisphosphonates (zoledronic acid 21.4% versus alendronate 10.7% versus risedronate 13.4%).

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics of Patients Meeting Inclusion Criteria Who Received Alendronate, Risedronate, or Zoledronic Acid, Stratified by Beneficiaries Who Discontinued Drug and Those Who Did Not

| Alendronate (59,251) |

Risedronate (6806) |

Zoledronic acid (7743) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation | No discontinuation | Discontinuation | No discontinuation | Discontinuation | No discontinuation | ||

| No. (%) | 20,455 (34.5) | 38,796 (65.5) | 2388 (35.1) | 4418 (64.9) | 3438 (44.4) | 4305 (55.6) | |

| Age (years) at index date | Mean (SD) | 79.1 (7.0) | 79.0 (7.4) | 79.2 (7.2) | 79.6 (7.6) | 79.1 (6.7) | 78.5 (6.7) |

| 65–69 (%) | 1685 (8.2) | 3871 (10.0) | 203 (8.5) | 393 (8.9) | 282 (8.2) | 397 (9.2) | |

| 70–74 (%) | 5142 (25.1) | 9724 (25.1) | 612 (25.6) | 1046 (23.7) | 788 (22.9) | 1134 (26.3) | |

| 75–79 (%) | 4758 (23.3) | 8565 (22.1) | 499 (20.9) | 918 (20.8) | 840 (24.4) | 1050 (24.4) | |

| 80–84 (%) | 4420 (21.6) | 7776 (20.0) | 504 (21.1) | 923 (20.9) | 785 (22.8) | 906 (21.0) | |

| 85+ (%) | 4450 (21.8) | 8860 (22.8) | 570 (23.9) | 1138 (25.8) | 743 (21.6) | 818 (19.0) | |

| Race (%) | White | 17,872 (87.4) | 31,607 (81.5) | 2083 (87.2) | 3608 (81.7) | 3295 (95.8) | 4063 (94.4) |

| Geographic region on index date (%) | Midwest | 6532 (31.9) | 12,099 (31.2) | 497 (20.8) | 987 (22.3) | 1180 (34.3) | 1433 (33.3) |

| Northeast | 3762 (18.4) | 6302 (16.2) | 617 (25.8) | 962 (21.8) | 507 (14.7) | 552 (12.8) | |

| South | 6603 (32.3) | 12,875 (33.2) | 855 (35.8) | 1606 (36.4) | 1428 (41.5) | 1862 (43.3) | |

| West | 3558 (17.4) | 7520 (19.4) | 419 (17.5) | 863 (19.5) | 323 (9.4) | 458 (10.6) | |

| Ever DXA (%) | Yes | 17,635 (86.2) | 32,476 (83.7) | 2054 (86.0) | 3585 (81.1) | 3251 (94.6) | 4062 (94.4) |

| Ever CQ major fragility fracture (%) | Yes | 3332 (16.3) | 7564 (19.5) | 404 (16.9) | 879 (19.9) | 854 (24.8) | 1133 (26.3) |

| Ever CQ hip fracture (%) | Yes | 935 (4.6) | 2207 (5.7) | 113 (4.7) | 278 (6.3) | 182 (5.3) | 237 (5.5) |

| Ever CQ vertebral fracture (%) | Yes | 1506 (7.4) | 3449 (8.9) | 170 (7.1) | 401 (9.1) | 501 (14.6) | 664 (15.4) |

| Charlson score category (%) | 0 | 10,177 (49.8) | 16,563 (42.7) | 1185 (49.6) | 1831 (41.4) | 1592 (46.3) | 1978 (45.9) |

| 1–2 | 5316 (26.0) | 10,552 (27.2) | 610 (25.5) | 1186 (26.8) | 994 (28.9) | 1213 (28.2) | |

| 3+ | 4962 (24.3) | 11,681 (30.1) | 593 (24.8) | 1401 (31.7) | 852 (24.8) | 1114 (25.9) | |

| Ever steroid use (%) | Yes | 7668 (37.5) | 13,523 (34.9) | 885 (37.1) | 1563 (35.4) | 606 (17.6%) | 769 (17.9) |

| 12,787 (62.5) | 25,273 (65.1) | 1503 (62.9) | 2855 (64.6) | 2832 (82.4) | 3536 (82.1) | ||

DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; CQ = case qualifying.

Table 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Patients Who Discontinued Bisphosphonates, Stratified by Those Who Restarted Any Osteoporosis (OP) Therapy and Those Who Did Not

| Alendronate (20,455) |

Risedronate (2388) |

Zoledronic acid (3348) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Did not restart OP therapy |

Restarted OP therapy |

Did not restart OP therapy |

Restarted OP therapy |

Did not restart OP therapy |

Restarted OP therapy |

||

| No. (%) | 18,270 (89.3) | 2185 (10.7) | 2069 (86.6) | 319 (13.4) | 2702 (78.6) | 736 (21.4) | |

| Age (years) at index date | Mean (SD) | 79.2 (7.1) | 78.0 (6.3) | 79.5 (7.2) | 77.7 (6.5) | 79.5 (6.8) | 77.7 (6.2) |

| 65–69 (%) | 1501 (8.2) | 184 (8.4) | 168 (8.1) | 35 (11.0) | 212 (7.8) | 70 (9.5) | |

| 70–74 (%) | 4509 (24.7) | 633 (29.0) | 522 (25.2) | 90 (28.2) | 583 (21.6) | 205 (27.9) | |

| 75–79 (%) | 4229 (23.1) | 529 (24.2) | 423 (20.4) | 76 (23.8) | 641 (23.7) | 199 (27.0) | |

| 80–84 (%) | 3913 (21.4) | 507 (23.2) | 434 (21.0) | 70 (21.9) | 621 (23.0) | 164 (22.3) | |

| 85+ (%) | 4118 (22.5) | 332 (15.2) | 522 (25.2) | 48 (15.0) | 645 (23.9) | 98 (13.3) | |

| Race (%) | White | 15,975 (87.4) | 1897 (86.8) | 1815 (87.7) | 268 (84.0) | 2587 (95.7) | 708 (96.2) |

| Geographic region on index date (%) | Midwest | 5833 (31.9) | 699 (32.0) | 437 (21.1) | 60 (18.8) | 935 (34.6) | 245 (33.3) |

| Northeast | 3397 (18.6) | 365 (16.7) | 538 (26.0) | 79 (24.8) | 419 (15.5) | 88 (12.0) | |

| South | 5881 (32.2) | 722 (33.0) | 731 (35.3) | 124 (38.9) | 1101 (40.7) | 327 (44.4) | |

| West | 3159 (17.3) | 399 (18.3) | 363 (17.5) | 56 (17.6) | 247 (9.1) | 76 (10.3) | |

| Ever DXA (%) | Yes | 15,685 (85.9) | 1950 (89.2) | 1757 (84.9) | 297 (93.1) | 2547 (94.3) | 704 (95.7) |

| Ever CQ major fragility fracture (%) | Yes | 2967 (16.2) | 365 (16.7) | 355 (17.2) | 49 (15.4) | 665 (24.6) | 189 (25.7) |

| Ever CQ hip fracture (%) | Yes | 846 (4.6) | 89 (4.1) | 104 (5.0) | 9 (2.8) | 147 (5.4) | 35 (4.8) |

| Ever CQ vertebral fracture (%) | Yes | 1331 (7.3) | 175 (8.0) | 144 (7.0) | 26 (8.2) | 388 (14.4) | 113 (15.4) |

| Ever steroid (%) | Yes | 11,393 (62.4) | 1394 (63.8) | 1300 (62.8) | 203 (63.6) | 2223 (82.3) | 609 (82.7) |

| Charlson score category (%) | 0 | 9028 (49.4) | 1149 (52.6) | 1030 (49.8) | 155 (48.6) | 1219 (45.1) | 373 (50.7) |

| 1–2 | 4749 (26.0) | 567 (25.9) | 512 (24.7) | 98 (30.7) | 789 (29.2) | 205 (27.9) | |

| 3+ | 4493 (24.6) | 469 (21.5) | 527 (25.5) | 66 (20.7) | 694 (25.7) | 158 (21.5) | |

DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; CQ = case qualifying.

Time-varying factors associated with discontinuation/restarting alendronate using case-crossover design

Among alendronate users, 20,455 (34.5%) discontinued for ≥12 months, serving as our sample for the case-crossover cohort to identify factors associated with discontinuation. Multivariable analysis demonstrated several factors associated with discontinuation, represented as adjusted odds ratio (aOR) (95% confidence interval [CI]) (Table 3). The factors most strongly associated with discontinuation included: a new prescription of benzodiazepine (aOR = 3.1 [2.7–3.6]), Alzheimer’s or other dementia diagnosis (aOR = 2.0 [1.8, 2.3]), SNF care utilization (aOR = 1.9 [1.7, 2.2]), prescription of proton pump inhibitor (aOR = 1.8 [1.6, 1.9]), performing a DXA scan (aOR = 1.7 [1.7, 1.6]), hospitalization (aOR = 1.5 [1.3, 1.6]), osteoporosis and osteopenia diagnosis (aOR = 1.4 [1.3, 1.5] and aOR = 1.8 [1.7, 2.0], respectively). Many medication prescriptions and greater use of medical services were also significantly related to discontinuation of alendronate (Table 3).

Table 3.

Time-Varying Factors Associated With Prolonged Discontinuation of Alendronate

|

N = 20,455 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard period n (%) |

Control periods 1 and 2 n (%) |

Adjusted OR (Wald 95% CI) |

|

| Factors associated with bone health | |||

| Case qualifying fragility fracture | 441 (2.2) | 400 (1.0) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.4) |

| Osteopenia diagnosis | 1499 (7.3) | 1794 (4.4) | 1.8 (1.7, 2.0) |

| Osteoporosis diagnosis | 5510 (26.9) | 7820 (19.1) | 1.4 (1.3, 1.5) |

| Fall | 744 (3.6) | 986 (2.5) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) |

| DXA scan | 2884 (14.1) | 3219 (7.9) | 1.7 (1.6, 1.7) |

| Bone turnover markers | 3 (0.0) | 1 (0.0) | 6.6 (0.7, 64.2) |

| At least 1 visit with an osteoporosis specialist (rheumatologist or endocrinologist) | 1328 (6.5) | 2343 (5.7) | 1.2 (1.0, 1.3) |

| Factors associated with overall health status | |||

| No. of unique days with at least 1 physician visit | 6512 (31.8) | 15,079 (36.9) | ref |

| 0–1 | |||

| 2–4 | 6605 (32.3) | 13,694 (33.5) | 1.0 (1.0, 1.1) |

| 5 or more | 7338 (35.9) | 12,137 (29.7) | 1.3 (1.2, 1.3) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 15,726 (76.9) | 32,382 (79.2) | ref |

| 0 | |||

| 1 to 2 | 3507 (17.1) | 6690 (16.4) | 1.0 (0.9, 1.1) |

| 3+ | 1222 (6.0) | 1838 (4.5) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.3) |

| At least 1 ER visit | 3694 (18.1) | 4706 (11.5) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.2) |

| At least 1 day hospitalized as inpatient | 2538 (12.4) | 2358 (5.8) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.6) |

| Hospitalized stroke, MI, CHD, CVD event | 97 (0.5) | 130 (0.3) | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) |

| Any skilled nursing facility care | 1163 (5.7) | 791 (2.0) | 1.9 (1.7, 2.2) |

| Alzheimer’s or other dementia | 2176 (10.6) | 2858 (7.0) | 2.0 (1.8, 2.3) |

| Depression or anxiety | 2251 (11.0) | 3309 (8.1) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.2) |

| Medications | |||

| Alpha blocker | 1350 (6.6) | 2456 (6.1) | 1.6 (1.3, 1.9) |

| Anticholinergic antihistamine | 284 (1.4) | 538 (1.3) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) |

| Antipsychotic | 189 (0.9) | 355 (0.9) | 1.4 (0.8, 2.4) |

| Barbiturate | 34 (0.2) | 38 (0.1) | 23.6 (3.1, 181.8) |

| Benzodiazepine | 1168 (5.7) | 1345 (3.3) | 3.1 (2.7, 3.6) |

| Beta blocker | 7871 (38.5) | 15,238 (37.3) | 1.3 (1.2, 1.4) |

| Muscle relaxant | 712 (3.5) | 1379 (3.4) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) |

| Nonbenzodiazepine, benzodiazepine agonist | 902 (4.4) | 1801 (4.4) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) |

| Opioid | 4852 (23.7) | 8823 (21.6) | 1.1 (1.0, 1.1) |

| Oral glucocorticoids | 1597 (7.8) | 2949 (7.3) | 1.2 (1.1, 1.3) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 4900 (24.0) | 8684 (21.3) | 1.8 (1.6, 1.9) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 3560 (17.4) | 6613 (16.2) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.7) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 496 (2.4) | 1055 (2.6) | 0.7 (0.6, 1.0) |

| Vasodilator | 992 (4.9) | 1766 (4.3) | 1.5 (1.3, 1.9) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; ER = emergency room; MI = myocardial infarction; CHD = chronic heart disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease.

Associations significant at p value <0.01 are in bold.

Among women taking alendronate who underwent a drug discontinuation, 2185 (10.7%) restarted any osteoporosis medication. Women who restarted an osteoporosis medication during the follow-up served as the sample for the case-crossover study for identifying factors associated with osteoporosis therapy restart (Table 4). The factors most strongly associated with osteoporosis treatment restart included: receiving a DXA scan (aOR = 9.0 [7.6, 10.7]), sustaining a fragility fracture (aOR = 2.8 [1.9, 4.0]), benzodiazepine prescription (aOR = 2.7 [1.8, 3.9]), new osteoporosis and osteopenia diagnosis (aOR = 2.3 [1.9, 2.8] and aOR = 1.5 [1.1, 2.1] respectively), Alzheimer’s or other dementia diagnosis (aOR = 2.0 [1.4, 2.9]), SNF care utilization (aOR = 1.9 [1.3, 2.8]), at least one visit with an osteoporosis specialist (rheumatologist or endocrinologist) (OR = 1.4 [1.0, 1.9]), and an opioid prescription (OR = 1.3 [1.1, 1.6]).

Table 4.

Factors Associated With Restart of Any Osteoporosis Medication Among Those Who Discontinued Alendronate 1

|

N = 2185 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Covariate | Hazard periodn (%) |

Control periods 1 and 2n (%) |

Adjusted OR (Wald 95% CI) |

| Factors associated with bone health | |||

| Case qualifying fragility fracture | 183 (8.4) | 86 (2.0) | 2.8 (1.9, 4.0) |

| New osteopenia diagnosis | 170 (7.8) | 152 (3.5) | 1.5 (1.1, 2.1) |

| New osteoporosis diagnosis | 862 (39.5) | 774 (17.7) | 2.3 (1.9, 2.8) |

| Fall | 135 (6.2) | 124 (2.9) | 1.4 (0.9, 2.0) |

| DXA scan | 948 (43.4) | 217 (5.0) | 9.0 (7.6, 10.7) |

| Bone turnover markers | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) | NA |

| At least 1 visit with an osteoporosis specialist (rheumatologist or endocrinologist) | 273 (12.5) | 367 (8.4) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) |

| Factors associated with overall health status | |||

| No. of unique days with at least 1 physician visit | 630 (28.8) | 1547 (35.4) | ref |

| 0–1 | |||

| 2–4 | 692 (31.7) | 1386 (31.7) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.1) |

| 5 or more | 863 (39.5) | 1437 (32.9) | 0.9 (0.8, 1.2) |

| Charlson comorbidity index | 1697 (77.7) | 3502 (80.2) | ref |

| 0 | |||

| 1 to 2 | 363 (16.6) | 675 (15.5) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) |

| 3+ | 125 (5.7) | 193 (4.4) | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) |

| At least 1 ER visit | 457 (20.9) | 582 (13.3) | 1.3 (1.0, 1.6) |

| At least 1 day hospitalized as inpatient | 276 (12.6) | 342 (7.9) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.0) |

| Hospitalized stroke, MI, CHD, CVD event | 10 (0.5) | 17 (0.4) | 0.8 (0.3, 2.1) |

| Any skilled nursing facility care | 152 (7.0) | 133 (3.1) | 1.9 (1.3, 2.8) |

| Alzheimer’s or other dementia | 213 (9.8) | 270 (6.2) | 2.0 (1.4, 2.9) |

| Depression or anxiety | 260 (11.9) | 399 (9.1) | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) |

| Medications | |||

| Alpha blocker | 166 (7.6) | 304 (7.0) | 1.6 (0.9, 2.9) |

| Anticholinergic antihistamine | 24 (1.1) | 39 (0.9) | 1.7 (0.8, 3.7) |

| Antipsychotic | 8 (0.4) | 10 (0.3) | 3.2 (0.4, 27.2) |

| Barbiturate | 2 (0.1) | 2 (0.1) | NA |

| Benzodiazepine | 220 (10.1) | 346 (8.0) | 2.7 (1.8, 3.9) |

| Beta blocker | 790 (36.2) | 1531 (35.0) | 1.1 (0.8, 1.6) |

| Muscle relaxant | 93 (4.3) | 155 (3.6) | 1.1 (0.7, 1.8) |

| Nonbenzodiazepine, benzodiazepine agonist | 79 (3.6) | 184 (4.3) | 0.6 (0.3, 1.1) |

| Opioid | 601 (27.5) | 969 (22.2) | 1.3 (1.1, 1.6) |

| Oral glucocorticoids | 229 (10.5) | 379 (8.7) | 1.2 (0.9, 1.6) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 537 (24.6) | 993 (22.7) | 1.4 (1.0, 1.9) |

| Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor | 336 (15.4) | 654 (15.0) | 1.3 (0.8, 1.9) |

| Tricyclic antidepressant | 39 (1.8) | 77 (1.8) | 1.3 (0.5, 3.0) |

| Vasodilator | 97 (4.4) | 198 (4.5) | 0.9 (0.4, 1.7) |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; DXA = dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry; ER = emergency room; MI = myocardial infarction; CHD = chronic heart disease; CVD = cardiovascular disease.

Associations significant at p value <0.01 are in bold.

Subgroup of the women in Table 3; treatment gap at least 365 days.

Discussion

Using a national cohort of long-term bisphosphonate users, we describe temporal trends and factors associated with bisphosphonate discontinuations and subsequent restart of osteoporosis medications. From 2010 to 2015, slightly more than one-third of the women in Medicare with long-term bisphosphonate treatment discontinued treatment for 12 months or more. We found that there was an increase in bisphosphonate discontinuation from just under 2% in the first half of 2010 to a peak of 14% in the last half of 2012. After 2012, the proportion of women who discontinued a bisphosphonate remained steady through the end of 2014. The factors associated with discontinuation of alendronate were mainly related to a worsening in the overall health status, whereas the factors associated with restart of any osteoporotic medication after discontinuation of alendronate were related to worsening bone health (eg, new osteoporotic fracture).

Oral bisphosphonates, alendronate and risedronate, had a smaller proportion of patients discontinue treatment than patients treated with zoledronic acid. This noted difference between zoledronic acid, an intravenous medication administered yearly, and other oral bisphosphonates might be attributable to zoledronic acid’s higher skeletal affinity, longer retention, and/or issues with timely receipt.(20) We also found that the increasing trend in discontinuation happened before the 2016 ASBMR recommendation on drug holidays and could partially reflect a response to a 2014 ASBMR report on atypical femoral fractures and the FDA 2010 drug safety communication.(21,22) Indeed, in 2010, the FDA required that all bisphosphonate drug labels suggest a discontinuation after 3 to 5 years of continuous use.

The prevalence of discontinuation in our study was similar to a previous study showing that, with a 120-day gap definition, the 1-year discontinuation rate among alendronate users was 42.2%.(23) The small difference noted between that study and ours might be explained by the slightly different definitions of discontinuation. We defined discontinuation as a treatment gap of >12 months compared with >4 months used in the study by Lo and colleagues. Our study included long-term adherent users (at least 3 years), whereas their analysis included patients who were initiating alendronate only, allowing for withdrawal related to early intolerance. Another similar analysis used a 60-day gap definition for discontinuation and showed that 58% of patients initiating an osteoporosis medication discontinued therapy by 12 months.(24) Defining discontinuation using shorter periods may fail to reflect an intentional discontinuation but rather represent the effect of a concomitant relevant medical event. For example, persons who develop acute medical illness are more likely to discontinue nonessential medications leading to a “sick-stopper” effect.(25) The careful consideration given to our definitions make it more likely that our findings are indicative of true drug holidays.

We determined that about 12% of those who discontinue a bisphosphonate subsequently restarted therapy. This result is lower than a previous study that reported 46% of patients who discontinue medication subsequently reinitiate an osteoporosis treatment, the majority within 6 months of discontinuation.(24) One explanation for this disparate finding is that the larger proportion could possibly be attributable to the shorter drug discontinuation definition the other authors used. Indeed, this shortterm discontinuation of bisphosphonates might not be planned and reflect only a temporary lack of adherence or drug unavailability.

The factors associated with discontinuation of alendronate were primarily associated with new medical diagnoses (eg, Alzheimer’s or other dementia), initiation of a medication suggesting worsening of overall health status (eg, benzodiazepines, vasodilators), or SNF care utilization. One of the possible explanations of this finding is that women who have had a significant worsening of health status (ie, new diagnosis or new medication) might consider the treatment of osteoporosis not essential, futile, or even harmful. Interestingly, newly prescribed proton pump inhibitors were one of the medications associated with discontinuation. This might be reflective of real or perceived gastrointestinal intolerance to alendronate. However, we have included only women who have been highly adherent to long-term bisphosphonate treatment, and such patients are less likely to experience delayed gastrointestinal intolerance to alendronate. The fact that patients who get sick with major medical conditions often discontinue alendronate might not be justifiable or desirable in many circumstances because those who have more comorbidity may be the very patients in whom continued osteoporosis care is most necessary. However, the reasons behind the decision to stop alendronate were unknown, given the nature of this data source. We do not know if the decision of stopping an osteoporosis medication was recommended by a bone specialist or another health care provider with less expertise in osteoporosis treatment or the patient alone. The factors associated with restarting osteoporosis medication after alendronate discontinuation were factors traditionally associated with worsening bone health. Indeed, having a DXA scan was among the main factors associated with restarting an osteoporosis medication. In addition, we found that, not surprisingly, patients who fracture are more likely to restart a treatment than patients who do not fracture. This result might be explained by the fact that patients who fracture seek medical attention more intensely than patients who do not fracture. Indeed, another factor strongly related to restarting an osteoporosis medication as opposed to discontinuation of alendronate was an office visit with an osteoporosis specialist (rheumatologist or endocrinologist). This difference could be related to the concerns that osteoporosis specialists may have about continued fracture risk or possibly in the onset of a new medical condition aggravating bone health and requiring a rheumatologist or endocrinologist visit.

Some factors were associated both with discontinuation of alendronate and restart of any osteoporosis medication. This result might be secondary to different prescription indications. For example, benzodiazepines and opioids might be used for pain control in patients with a recent fracture; on the other hand, the same drugs are prescribed for other medical reasons that reflect the “sick stopper” effect and might introduce new perceived contraindications to the osteoporosis medication. Another at first sight unexpected result is the association between diagnosis of osteoporosis and discontinuation of alendronate. In our analysis, a diagnosis of osteoporosis represent a new coding for osteoporosis and might be related to a mere acknowledgment of the disease made by a physician during the hazard period. Moreover, a new diagnosis of osteopenia was more strongly associated with discontinuation than osteoporosis diagnosis, supporting the hypothesis that improved BMD values were associated with discontinuation of alendronate.

A key strength of this study is that our data are based on the highly generalizable data from US women and their health care providers who prescribe osteoporosis therapy. However, it has some limitations common to administrative claims data. For example, repeated refills of prescription claims for medications do not indicate actual medication use with complete certainty. We also could not assess the underlying reasons for treatment discontinuation or restarting, and we did not have detailed information on covariates that may influence care decisions, including BMD result and biochemical markers of bone remodeling. To attenuate confounders of starting and stopping therapy, we designed a case-crossover study that controls for between-patient confounding and within-person, time-invariant confounding. Nonetheless, since some residual confounding may still be present in light of changes in health status, our results should be interpreted cautiously.

In summary, we analyzed temporal trends of discontinuation of bisphosphonates and sought to identify the factors associated with the discontinuation and restart of alendronate. Bisphosphonate discontinuation increased substantially between 2010 and 2012 and then continued steadily through 2014. Among our cohort of patients on long-term bisphosphonates, over a third discontinued the medication for more than 12 months and, among those, nearly 90% never restarted any osteoporosis medication during the time frame of our study. The factors associated with discontinuation of alendronate were predominately related to a worsening in overall health, whereas the main factors associated with restart of any osteoporosis medication were receipt of a DXA scan and new fragility fractures. Our study depicts the current trend in the discontinuation of bisphosphonates and provides new insights about patient factors associated with discontinuation of alendronate and restart of any osteoporosis medication at a population level. Further studies are needed to better ascertain factors most strongly associated with discontinuation/restart of osteoporosis therapies and to design future educational interventions aimed at avoiding unnecessary or inappropriate bisphosphonate discontinuation and restarting.

Footnotes

Disclosures

GA: None declared, AJ: None declared, JC: None declared, RC: None declared, HY Grant/research support from: BMS, Pfizer, SD: None declared, TA Grant/research support from: Amgen, MD Grant/research support from: Pfizer, Inc., Consultant for: Sanofi Genzyme & Regeneron, NW Grant/research support from: Amgen, Consultant for: NortonRose Fulbright/Pfizer, SC: None declared, AM: None declared, JF: None declared, KS Grant/research support from: Amgen, Radius Consultant for: Amgen, Daiichi Sankyo, Radius, Roche/Genentech.

References

- 1.Wysowski DK, Greene P. Trends in osteoporosis treatment with oral and intravenous bisphosphonates in the United States, 2002-2012. Bone. 2013;57(2):423–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodan G, Reszka A, Golub E, Rizzoli R. Bone safety of long-term bisphosphonate treatment. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004;20(8): 1291–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black DM, Schwartz AV, Ensrud KE, et al. Effects of continuing or stopping alendronate after 5 years of treatment: the Fracture Intervention Trial Long-term Extension (FLEX): a randomized trial. JAMA. 2006;296(24):2927–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jha S, Wang Z, Laucis N, Bhattacharyya T. Trends in media reports, oral bisphosphonate prescriptions, and hip fractures 1996-2012: an ecological analysis. J Bone Miner Res. 2015;30(12):2179–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SC, Kim DH, Mogun H, et al. Impact of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s safety-related announcements on the use of bisphosphonates after hip fracture. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(8):1536–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dell RM, Adams AL, Greene DF, et al. Incidence of atypical nontraumatic diaphyseal fractures of the femur. J Bone Miner Res. 2012;27 (12):2544–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adler RA, El-Hajj Fuleihan G, Bauer DC, et al. Managing osteoporosis in patients on long-term bisphosphonate treatment: report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2016;31(1):16–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gu T, Eisenberg Lawrence DF, Stephenson JJ, Yu J. Physicians’ perspectives on the treatment of osteoporosis patients with bisphosphonates. Clin Interv Aging. 2016;11:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Adams AL, Adams JL, Raebel MA, et al. Bisphosphonate drug holiday and fracture risk: a population-based cohort study. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(7):1252–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Delzell E, Saag KG. Risk of hip fracture after bisphosphonate discontinuation: implications for a drug holiday. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19(11):1613–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fink HA, MacDonald R, Forte ML, et al. Long-term drug therapy and drug discontinuations and holidays for osteoporosis fracture prevention: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171(1):37–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Curtis JR, Chen R, Li Z, et al. The impact of the duration of bisphosphonate drug holidays on hip fracture rates. Ann Rheum Dis. 2018; 77(Suppl 2):58. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anagnostis P, Paschou SA, Mintziori G, et al. Drug holidays from bisphosphonates and denosumab in postmenopausal osteoporosis: EMAS position statement. Maturitas. 2017;101:23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yun H, Curtis JR, Guo L, et al. Patterns and predictors of osteoporosis medication discontinuation and switching among Medicare beneficiaries. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2014;15:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maclure M, Mittleman MA. Should we use a case-crossover design? Annu Rev Public Health. 2000;21:193–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raebel MA, Schmittdiel J, Karter AJ, Konieczny JL, Steiner JF. Standardizing terminology and definitions of medication adherence and persistence in research employing electronic databases. Med Care. 2013;51(Suppl 3):S11–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Curtis JR, Westfall AO, Cheng H, Lyles K, Saag KG, Delzell E. Benefit of adherence with bisphosphonates depends on age and fracture type: results from an analysis of 101,038 new bisphosphonate users. J Bone Miner Res. 2008;23(9):1435–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Burden AM, Paterson JM, Gruneir A, Cadarette SM. Adherence to osteoporosis pharmacotherapy is underestimated using days supply values in electronic pharmacy claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24(1):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell RGG, Xia Z, Dunford JE, et al. Bisphosphonates: an update on mechanisms of action and how these relate to clinical efficacy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1117:209–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.US Food and Drug Administration. FDA Drug Safety Communication: safety update for osteoporosis drugs, bisphosphonates, and atypical fractures [Internet]. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm229009.htm. Accessed October 16, 2018.

- 22.Shane E, Burr D, Abrahamsen B, et al. Atypical subtrochanteric and diaphyseal femoral fractures: second report of a task force of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. J Bone Miner Res. 2014;29(1):1–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo JC, Pressman AR, Omar MA, Ettinger B. Persistence with weekly alendronate therapy among postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2006;17(6):922–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balasubramanian A, Brookhart MA, Goli V, Critchlow CW. Discontinuation and reinitiation patterns of osteoporosis treatment among commercially insured postmenopausal women. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:839–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Glynn RJ, Knight EL, Levin R, Avorn J. Paradoxical relations of drug treatment with mortality in older persons. Epidemiology. 2001;12 (6):682–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]