Abstract

Background

The optimal sequence of stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT) and immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) and assessment of response in patients with brain metastases from melanoma remain challenging.

Methods

We reviewed clinical and neuroimaging data of 62 patients with melanoma, including 26 patients with BRAF-mutant tumours, with newly diagnosed brain metastases treated with ICI alone (n=10, group 1), SRT alone or in combination with other systemic therapies (n=20, group 2) or ICI plus SRT (n=32, group 3). Response was assessed retrospectively using response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (RECIST) V.1.1, response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) and immunotherapy RANO (iRANO) criteria. MRI follow-up from 43 patients was available for central review.

Results

Patients treated with ICI alone showed no objective responses and had worse outcome than patients treated with SRT without or with ICI. RECIST, RANO and iRANO criteria were concordant for complete response (CR) and partial response (PR). RANO called progression earlier than RECIST for clinical deterioration without MRI progression in some patients. Progression was called later when using iRANO criteria because of the need for a confirmatory scan. Pseudoprogression was documented in seven patients: three patients in group 2 and four patients in group 3. Radionecrosis was documented in seven patients: two patients in group 2 and five patients in group 3. Regression of non-irradiated lesions was seen neither in two patients treated with SRT alone nor in five patients treated with SRT plus ICI, providing no evidence for rare abscopal effects.

Conclusions

Pseudoprogression is uncommon with ICI alone, suggesting that growing lesions in such patients should trigger an intervention. Pseudoprogression rates were similar after SRT alone or SRT in combination with ICI. Abscopal effects are rare or do not exist. Response assessment criteria should be considered carefully when designing clinical studies for patients with brain metastases who receive SRT.

Keywords: gamma knife, stereotactic radiotherapy, criteria, radionecrosis, pseudoprogression

Key points.

What is already known about this subject?

Metastases to the central nervous system are an increasing challenge in general oncology, specifically in melanoma. They may affect up to 30% of all patients with cancer and are a major source of morbidity and mortality. As patients with cancer survive longer because of improved medical treatments, the control of brain metastasis (BM) emerges as a major goal of cancer treatment in general.

How might this impact on clinical practice?

While the novel systemic therapies including immunotherapy and targeted treatment contribute to the control of BM, radiotherapy has traditionally been the mainstay of treatment of BM. One of the major current controversies centres on the optimal timing of focal radiotherapy for BM: should it be administered upfront to optimise local control, with a potential risk of neurotoxicity in long-term surviving patients, or should radiotherapy be delayed until systemic therapy has failed? And how do we address the challenges experienced with neuroimaging-based response assessment? Do abscopal effects truly exist in this patient population?

How might this impact on clinical practice?

The present study illustrates several pitfalls in the assessment of these patients. It does not support that abscopal effects are common and, regarding outcome, lends support to the notion that stereotactic radiotherapy should not be readily abandoned as a first-line treatment option.

Introduction

Patients with metastatic melanoma carry a high lifetime risk of developing brain metastasis (BM). The outcome for these patients improved when whole brain radiotherapy was substituted by stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT)1 and when effective targeted therapies for BRAF-mutant tumours2 3 as well as immune checkpoint inhibition (ICI) were introduced.4–6 However, both treatment modalities, SRT and ICI, have caused new challenges when evaluating neuroimaging by MRI which is considered the gold standard of monitoring response during follow-up. It is not surprising that a treatment like SRT that is designed to eradicate metastatic lesions causes tissue damage, but differentiating this tissue damage from progressive tumour growth has turned out to be difficult. Furthermore, ICI treatment is meant to induce an immune and associated inflammatory response to metastatic lesions, and these changes would also be expected to resemble progressive tumours. These considerations have led the response assessment in neuro-oncology (RANO) group to design specific response criteria for patients with brain tumours exposed to immunotherapy already in 2015 when little data on specific challenges in the assessment of BM were available.7 Since then response assessment in BM treated with SRT or ICI remains to be an issue of controversy primarily in clinical practice, and in the conduct of clinical trials.

Compared with the response evaluation criteria in solid tumours (RECIST) criteria,8 RANO criteria for BM were expanded to also include clinical status and steroid medication within the response criteria9 (online supplementary table S1). The major goal of the immunotherapy RANO (iRANO) criteria was to make sure that patients are not taken off a potentially effective treatment prematurely.7 immune (i)RECIST criteria have been introduced with a similar rationale.10 The present retrospective analysis compared how clinical decision making should have evolved when either of these sets of criteria was used and compared these data with the treatment that was actually administered in real life.

esmoopen-2020-000763supp001.pdf (126.9KB, pdf)

Patients and methods

Patients

We retrospectively reviewed the charts of consecutive patients with histologically confirmed melanoma that were newly diagnosed with BM, fulfilled criteria of measurable disease by RANO,9 and were treated, without or with prior surgical resection, with ICI targeting cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen (CTLA) 4, programmed death (PD)−1 or PD-ligand (PD-L) 1 (group 1), SRT without or with non-immuno-oncology (IO) pharmacotherapy (group 2), or ICI plus SRT (group 3). Patients were assigned to group 3 if the time interval between SRT and IO was less than 90 days. The parameters documented in the electronic case report form (eCRF) are summarised in online supplementary table S2.

Study design

The main objective was to determine response based on the application of RECIST 1.1, RANO and iRANO criteria (online supplementary table S1). Furthermore, we assessed the frequency of pseudoprogression and radionecrosis on standard MRI sequences and explored the pattern of central nervous system (CNS) progression including any potential abscopal effect. Pseudoprogression was defined as an increase of lesion volume of 25% or more that resolved without institution of a new anticancer treatment except steroids. Radionecrosis was defined as the appearance of necrosis within the treated target volume irrespective of size. We explored two operational definitions of abscopal effects induced by SRT: (A) An abscopal effect can be stated when there is a significant reduction of the volume of a distant lesion not treated by SRT in a SRT-treated patient who received no concomitant systemic treatment; (B) abscopal effects can be postulated if ICI induces a better outcome when combined with SRT compared with ICI alone, excluding irradiated lesions as target lesions.

Data on progression-free survival (PFS) as assessed by the treating physicians were compiled for 3-month intervals from BM-directed treatment to progression at any site. CNS progression was defined as time from BM-directed treatment to progression anywhere in the CNS. Target-specific PFS was determined for irradiated lesions in groups 2 and 3. These PFS parameters were based on imaging alone. Extra-CNS PFS was defined as the time from BM-directed treatment to extra-CNS progression. Global PFS was defined as the time from BM-directed treatment to first progression. In addition, we explored whether clinical neurological progression occurred in the absence of MRI progression on neuroimaging. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from BM-directed treatment to death or last follow-up. Neuroimaging data of 43 patients were centrally reviewed. All data were extracted from medical records. The melanoma Diagnosis-specific Graded Prognostic Assessment Score (DS GPA) was determined as described.11

Statistical analysis

Descriptive analyses were performed in order to check and summarise the data. Survival rates were determined using the Kaplan-Meier method. Survival curves were compared between groups using the log-rank test. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS software V.9.4 (Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 62 patients was studied (Lille, n=36, diagnosed November 2008 to May 2017; Zurich, n=26, diagnosed November 2010 to April 2017). The melanoma history is summarised in online supplementary table S3. The median Breslow Index at melanoma diagnosis was 3 (interquartile range (IQR 1.5–5.5). A BRAF mutation was present in tumours of 26 patients (42%). At the time of melanoma diagnosis, distant metastases were identified in 17 patients, including 9 patients with BM. Treatment prior to BM diagnosis included chemotherapy for 6 patients, targeted therapy for 8 patients and immunotherapy for 18 patients. Ten patients were treated by ICI targeting CTLA-4, PD-1 or PD-L1 (group 1). Twenty patients were treated by SRT without or with non-ICI pharmacotherapy (group 2), and 32 patients were treated by ICI plus SRT (group 3). In the latter group, 25 patients received the combined treatment within 1 month, whereas the time interval was greater than 30 days for 7 patients (SRT first for 3 patients with a time interval of 38, 46 and 83 days; ICI first for 4 patients with a time interval of 38, 42, 44, 62 days).

Presentation of BM

Median age at BM diagnosis was 58 years (IQR 45–68), median Karnofsky Performance Score was 90 (IQR 80–100). The median interval from diagnosis of the primary tumour to the diagnosis of BM was 23 months (IQR 9–43). The most frequent neurological symptoms and signs at BM diagnosis were headaches and paresis, but 31 patients (50%) were asymptomatic for BM. Thirty-four patients (55%) had one BM, 19 patients (31%) two to three BM, 3 patients (5%) four to five BM and six patients (10%) had more than five BM. The median maximum diameter of the largest BM was 18 mm (IQR 13–25). BM were haemorrhagic in 19 patients (31%). Perilesional oedema of at least 20% of the BM diameter was noted in 42 patients (68%). A comparison of groups showed that group 1 patients had more often multiple, and more often smaller BM characteristics whereas BM in groups 2 and 3 were similar (table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline clinical and MRI characteristics

| Items | All patients (n=62) |

Group 1 ICI alone (n=10) |

Group 2 Stereotactic radiotherapy without or with non-ICI pharmacotherapy (n=20) |

Group 3 ICI plus stereotactic radiotherapy (n=32) |

| Age at BM diagnosis (years): median (IQR) | 58 (45–68) | 58 (47–71) | 55 (43–63) | 58 (51–69) |

| KPS at BM diagnosis (n, %) | ||||

| 90-100 | 35 (56) | 6 (60) | 13 (65) | 16 (50) |

| 70-80 | 25 (40) | 4 (40) | 7 (35) | 14 (44) |

| <70 | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) |

| Median KPS (IQR) | 90 (80–100) | 95 (80–100) | 90 (80–100) | 85 (80–92) |

| Time interval between diagnosis of melanoma and diagnosis of BM in months: median (IQR) | 23 (9–43) | 22 (15–25) | 19 (13–40) | 28 (7–50) |

| New metastatic sites outside CNS at BM diagnosis | 30 (48) (3 n=59) | 6 (60) (n=10) | 9 (45) (1 n=9) | 15 (47) (2 n=30) |

| Symptoms and signs (n, %) | ||||

| Seizures | 9 (14) | 0 | 2 (10) | 7 (22) |

| Paresis | 15 (24) | 0 | 3 (15) | 12 (37) |

| Aphasia | 7 (11) | 0 | 0 (0) | 7 (22) |

| Visual disturbance | 4 (6) | 0 | 0 (0) | 4 (12) |

| Sensory deficits | 8 (13) | 0 | 3 (15) | 5 (16) |

| Headache | 14 (23) (n=31) | 0 | 7 (35) | 7 (22) (n=31) |

| Psychiatric and cognitive disorders | 8 (13) | 0 | 2 (10) | 6 (19) |

| Cerebellar and brainstem symptoms | 1 (2) (n=30) | 0 | 1 (5) (n=9) | 0 (0) (n=31) |

| Other symptoms | 1 (2) (n=31) | 0 | 0 (0) (n=9) | 1 (3) |

| Asymptomatic | 31 (50) | 10 (100) | 8 (40) | 13 (41) |

| LDH level at BM diagnosis (n, %) | ||||

| Elevated | 14 (23) | 3 (30) | 5 (25) | 6 (19) |

| Normal | 36 (58) | 6 (60) | 8 (40) | 22 (69) |

| No data | 12 (19) | 1 (10) | 7 (35) | 4 (12) |

| Median LDH level (IQR) | 326 (251–449) (n=43) | 262 (197–353) (n=7) | 397 (284–492) (n=11) | 321 (268–412) (n=25) |

| DS-GPA at BM diagnosis: median (IQR) | 2 (1.5-.2.5) | 1.75 (1.1–2.4) | 2.5 (1.5–3) | 2 (1.5–2.5) |

| Number of BM (n, %) | ||||

| 1 | 34 (55) | 4 (40) | 14 (70) | 16 (50) |

| 2 | 13 (21) | 0 (0) | 2 (10) | 11 (34) |

| 3 | 6 (10) | 1 (10) | 3 (15) | 2 (6) |

| 4 | 1 (2) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 5 | 2 (3) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| >5 | 6 (10) | 3 (30) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 3.5 (1.5–5.75) | 1 (1–2) | 1.5 (1–2) |

| Maximum diameter of largest BM: median (IQR) | 18 (13–25) | 13 (10–15) | 21 (17–24) | 18 (14–25) |

| BM with a maximal diameter >30 mm (n, %) | 9 (14) | 0 | 5 (25) | 4 (12)) |

| Necrotic BM (n, %) | 6 (10) (n=59) | 0 (n=9) | 3 (15) (n=19) | 3 (9) (n=31) |

| Cystic BM (n, %) | 8 (13) (n=61) | 0 (n=9) | 2 (10) (n=20) | 6 (19) (n=32) |

| Haemorrhagic BM (n, %) | 19 (31) (n=58) | 1 (11) (n=9) | 5 (25) (n=18) | 13 (41) (n=31) |

| Significant oedema (n, %) | 42 (68) (n=59) | 5 (50) (n=10) | 14 (70) (n=17) | 23 (72) (n=32) |

| Oedema, mm: median (IQR) | 10.5 (1.5–17) (n=54) | 0 (0–5.5) (n=7) | 18 (10–25) (n=17) | 10 (2–14) (n=30) |

The number of patients is given when not all the data are available.

*Two patients had multiple brain metastases and were considered with 10 metastases.

BM, brain metastases; CNS, central nervous system; DS-GPA, diagnosis-specific graded prognostic assessment; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition; KPS, Karnofsky Performance Score; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; n, number of patients.

Treatment characteristics and follow-up

In response to BM diagnosis, 14 patients (22%) were treated with antiepileptic drugs and 29 patients (47%) received steroids. Prior to further BM-directed treatment, surgery for BM was performed in 22 patients (35%), with a gross total resection in 15 (68%) of these patients. Seven of these 15 patients (47%) had two BM-suspicious lesions and 2 patients had three BM-suspicious lesions that were all treated by SRT. The rates of surgery differed substantially: none in group 1, 7 patients (35%) in group 2 and 15 patients (47%) in group 3. SRT to the surgical bed was performed in 19 patients (86%). Group 2 patients received SRT with a median number of 1 target (IQR 1–1.25), a median dose of 25 Gray (Gy) (24–25) and a median volume of 3 mL (2–8). Group 3 patients received SRT with a median number of targets of 1 (IQR 1–2), a median dose of 27 Gy (IQR 25–30), and a median volume of 4 mL (IQR 3–9). In group 3, ICI was started prior to SRT in 15 patients and after SRT in 16 patients each. The median interval between start of SRT and start of ICI was 14 days (IQR 9–25) when SRT was initiated first. The median interval between start of ICI and start of SRT was 18 days (IQR 11–30) when ICI was initiated first. One patient had both treatments on the same day. Ten patients developed an adverse event severe enough to stop ICI treatment, one in group 1 (hypophysitis) and nine in group 3 (colitis, n=3; interstitial nephritis, n=1; interstitial pneumopathy, n=1; exanthema, hypophysitis, encephalitis pneumopathy, n=1; hepatitis and thrombosis, n=1; hepatitis, n=1; thyroiditis, n=1).

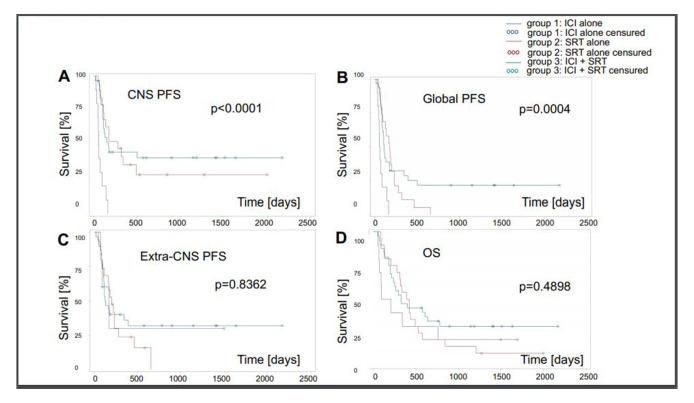

After a median follow-up of 30.5 months for surviving patients, 37 patients (60%) had experienced CNS progression, 9 patients (90%) in group 1, 14 (patients 70%) in group 2 and 17 patients (53%) in group 3. Median CNS-related PFS was lowest in group 1. CNS progression was BM in 29 (46%) patients: 9 patients (90%) in group 1, 9 patients (45%) in group 2 and 11 patients (34%) in group 3. Leptomeningeal metastasis (LM), alone or combined with BM progression, was observed in 11 patients (18%); 1 patient (10%) in group 1, 4 patients (20%) in group 2 and 6 patients (18%) in group 3. Among 22 patients operated for BM, 6 patients (27%) developed LM (1 LM only, 5 BM and LM). Among 40 patients not operated, 5 patients (12.5%) developed LM (2 LM only, 2 BM and LM). Median survival of operated versus non-operated patients was 12 (IQR 7–28) vs 11 (IQR 4–22) months. Forty-eight patients (77%) had died at the time of the analysis; 8 patients (80%) in group 1, 18 patients (90%) in group 2 and 22 patients (69%) in group 3. CNS disease only or in combination with extra-CNS disease was a cause of death in 5 patients (50%) in group 1, in 5 patients (62%) in group 2 and in 11 patients (50%) in group C. Median OS was shortest in group 1 (figure 1, table 2).

Figure 1.

Outcomes by group assignments: (A) CNS-PFS. (B) Global PFS. (C) Extra-CNS. (D) OS. CNS, central nervous system; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-freesurvival; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy.

Table 2.

BM treatment characteristics and outcome[‡]

| All patients | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| ICI alone | Stereotactic radiotherapy without or with non-ICI pharmacotherapy | ICI plus stereotactic radiotherapy | ||

| (n=62) | (n=10) | (n=20) | (n=32) | |

| Concomitant medication | ||||

| Antiepileptic drugs (n, %) | ||||

| No antiepileptic drug | 34 (55) | 8 (80) | 9 (45) | 17 (53) |

| Initiated at BM diagnosis | 14 (22) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 13 (41) |

| During the course of BM diagnosis | 14 (22) | 2 (20) | 10 (50) | 2 (6) |

| Steroid intake at BM diagnosis (n, %) | 29 (47) (n=61) |

1 (10) | 12 (60) | 16 (50) (n=31) |

| Steroid dose (dexamethasone equivalent) at BM diagnosis (n, IQR) | 13 (10–16) | 10 (10–10) | 10 (6–15) | 16 (12–16) |

| (n=29) | (n=1) | (n=12) | (n=16) | |

| Steroids at immunotherapy initiation | 14 (28) (n=50) |

1 (10) (n=10) |

n.a. | 13 (43) (n=30) |

| Surgery for BM | ||||

| Any neurosurgical intervention (n, %) | 22 (35) | 0 (0) | 7 (35) | 15 (47) |

| Time interval between BM diagnosis by imaging and surgery in days: median (IQR) | 8 (5–19) (n=22) | n.a. | 6 (4–7.5) (n=7) | 8 (5–20) (n=15) |

| Type of surgery: (n, % among operated patients) | ||||

| Partial resection | 7 (32) | 0 (0) | 2 (28) | 4 (27) |

| Gross total resection | 15 (68) (n=22) | 0 (0) (n=0) | 5 (71) (n=7) | 11 (73) (n=15) |

| Radiotherapy (RT) | ||||

| RT for surgical cavity in operated patients (n, %) | 19 (86) (n=22) | n.a. | 6 (86) (n=7) | 13 (87) (n=15) |

| RT in addition to surgical bed/RT for further lesions (n, % among patients treated with SRS/SRT) | ||||

| SRS | 27 (52) | n.a. | 13 (65) | 14 (44) |

| FSRT | 24 (46) | 7 (35) | 17 (53) | |

| SRS and FSRT | 1 (2) (n=52) | 0 (0) (n=20) | 1 (3) (n=32) | |

| For SRS or FSRT, number of targets (n, % among patients treated with SRS/SRT) | ||||

| 1 | 36 (69) | n.a. | 15 (75) | 21 (66) |

| 2 | 9 (17) | 2 (10) | 7 (22) | |

| 3 | 5 (10) | 3 (15) | 2 (6) | |

| >3 | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | |

| Number of targets: median (IQR) | 1 (1–2) | 1 (1–1.25) | 1 (1–2) | |

| (n=52) | (n=20) | (n=32) | ||

| For SRS or FSRT, maximum dose in Gy: median (IQR) | 25 (25–30) (n=52) |

n.a. | 25 (24–25) (n=20) |

27 (25–30) (n=32) |

| For SRS or FSRT, total volume treated in ml (median, IQR) | 4 (2–9) | n.a. | 3 (2–8) | 4 (3–9) |

| (n=48) | (n=19) | (n=29) | ||

| Time interval between BM diagnosis by imaging and first dose of RT in days (median, IQR) | 34 (23–45) | n.a. | 33 (25–38) | 35 (20–52) |

| (n=52) | (n=20) | (n=32) | ||

| ICI | ||||

| n (n (%) | ||||

| Any | 42 (68) | 10 (100) | n.a. | 32 (100) |

| Ipilimumab | 21 (34) | 6 (60) | 15 (47) | |

| Nivolumab | 5 (8) | 0 (0) | 5 (16) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 15 (24) | 4 (40) | 11 (34) | |

| Ipilimumab + nivolumab | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | |

| Time interval between SRS or first dose of FSRT and first dose of ICI in days (median, IQR) | ||||

| RT prior to ICI | n.a. | n.a. | 14 (9–25) (n=15) | |

| ICI prior to RT | 18 (11–30) (n=16)* | |||

| Median duration of ICI in months: median (IQR) | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–2) | n.a. | 2 (1–6) |

| ICI-related AE leading to permanent stop of IO treatment (n, % among patients treated with ICI) | 10 (24) | 1 (10) | n.a. | 9 (28) |

| Systemic targeted therapy | ||||

| n (n (%) | n.a. | n.a. | ||

| Any | 5 (8) | 5 (25) | ||

| Vemurafenib | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | ||

| Dabrafenib | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | ||

| Vemurafenib + cobimetinib | 2 (3) | 2 (10) | ||

| Dabrafenib + trametinib | 1 (2) | 1 (5) | ||

| Time interval between SRS or FSRT and systemic targeted therapy (TT) in days (median, range) | n.a. | n.a. | ||

| RT prior to TT | 8 (8–8) (n=1) | 8 (8–8) (n=1) | ||

| TT prior to RT | 17 (13–22) (n=4) | 17 (13–22) (n=4) | ||

| Systemic chemotherapy | ||||

| n (n (%) | n.a. | |||

| Any | 7 (11) | 2† (20) | 5 (25) | |

| Fotemustine | 1 (2) | 1 (10) | 1 (5) | |

| Temozolomide | 5 (8) | 0 (0) | 4 (20) | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 1 (2) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | |

| Time interval between SRS or FSRT and systemic chemotherapy in days (median, IQR) | n.a. | |||

| RT prior to chemotherapy | 14 (14–14) (n=1) | n.a. | 14 (14–14) (n=1) | |

| Chemotherapy prior to RT | 18 (12–23) (n=4) | 18 (12–23) (n=4) | ||

| Outcome | ||||

| CNS progression (n, %) | 37 (60) | 9 (90) | 14 (70) | 17 (53) |

| CNS PFS from BM diagnosis in months (median, IQR) | 5 (3–17) | 3 (1–4) | 7 (4–42) | 6 (3–28) |

| CNS PFS from first BM treatment in months (median, IQR) | 5 (3–16) | 2 (2–3) | 7 (4–42) | 5 (3–26) |

| Type of CNS progression (n, type of CNS progression (n, %) | ||||

| Brain | 29 (46) | 9 (90) | 9 (45) | 11 (34) |

| Leptomeningeal metastases | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Both | 8 (13) | 1 (10) | 3 (15) | 4 (12) |

| None | 19 (31) | 0 (0) | 6 (30) | 13 (41) |

| Unknown | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| Pattern of BM progression (n, %) | ||||

| Local | 10 (16) | 2 (20) | 2 (10) | 6 (19) |

| Distant | 21 (34) | 3 (30) | 9 (45) | 9 (28) |

| Both | 7 (11) | 4 (40) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| None | 19 (31) | 0 (0) | 6 (30) | 13 (41) |

| Unknown | 5 (8) | 1 (10) | 2 (10) | 2 (6) |

| Extra-CNS progression at the time of brain progression (n, %) | ||||

| Progression | 29 (47) | 3 (30) | 11 (55) | 15 (47) |

| Stability | 5 (8) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 4 (12) |

| Improvement | 2 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| None | 16 (26) | 2 (20) | 4 (20) | 10 (31) |

| Unknown | 10 (16) | 5 (50) | 3 (15) | 2 (6) |

| Extra-CNS PFS from BM diagnosis in months (median, IQR) | 5 (3–12) | 3 (3–22) | 6 (3–21) | 5 (3–28) |

| Extra-CNS PFS from first BM treatment in months (median, IQR) | 5 (3–11) | 3 (2–20) | 7 (4–22) | 4 (3–14) |

| Any first progression (n,%) | ||||

| Yes | 54 (87) | 10 (100) | 19 (95) | 25 (78) |

| No | 7 (11) | 0 | 1 (5) | 6 (19) |

| Death without precision | 1 (2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (3) |

| Global PFS from BM diagnosis in months (median, IQR) | 5 (3–7) | 3 (1–4) | 6 (4–22) | 5 (3–13) |

| Global PFS from first BM treatment in months (median, IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 2 (2–3) | 6 (3–21) | 3 (3–12) |

| Type of any first progression (n, %) | ||||

| LM | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| BM | 14 (22) | 6 (60) | 3 (15) | 5 (16) |

| Extra-CNS | 17 (27) | 0 (0) | 8 (40) | 9 (28) |

| LM and BM | 1 (2) | 1 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| LM and extra-CNS | 1 (2) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| BM and extra-CNS | 18 (29) | 3 (30) | 7 (35) | 8 (5) |

| LM and BM and extra-CNS | 3 (5) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 2 (6) |

| None | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) |

| Unknown | 7 (11) | 0 (0) | 1 (5) | 6 (19) |

| Treatment after any progression | ||||

| Yes | 40 (74) | 5 (50) | 16 (84) | 19 (76) |

| No | 14 (26) | 5 (50) | 3 (20) | 6 (4) |

| (n=54) | (n=10) | (n=19) | (n=25) | |

| Median time to next treatment after progression in days (median, IQR) | 22 (7–46) | 15 (8–17) | 20 (6–46) | 28 (8–46) |

| Death (n, %) | 48 (77) | 8 (80) | 18 (90) | 22 (69) |

| Cause of death (n, % among deceased patients) | ||||

| Neurological | 21 (27) | 5 (62) | 8 (44) | 8 (36) |

| Extra-CNS | 5 (10) | 1 (12) | 3 (17) | 1 (4) |

| Neurological and extra-CNS | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 3 (0) |

| Complication of treatment | 2 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 2 (9) |

| Other | 3 (6) | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | 2 (9) |

| Unknown | 13 (27) | 2 (24) | 5 (28) | 6 (27) |

| (n=48) | (n=8) | (n=18) | (n=22) | |

| OS from BM diagnosis in months (median, IQR) | 11 (6–27) | 6 (3–23) | 14 (10–42) | 11 (7–28) |

| OS from first BM treatment in months (median, IQR) | 11 (6–25) | 5 (3–21) | 13 (8–42) | 11 (6–27) |

*One patient had both treatment (SRT and ICI) on the same day.

†Two patients received a combination of ICI and chemotherapy.

‡Among the whole cohort, unless specified.

§The number of patients is given when not all the data are available. % among the whole cohort, unless specified

AE, adverse event; BM, brain metastases; CNS, central nervous system; Gy, Grey; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition; IO, immuno-oncology; LM, leptomeningeal metastases; n, number of patients; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression-free survival; SRS, stereotactic radiosurgery; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy.

Retrospective review of response: landmark analyses

Online supplementary table 4 summarises response status per local assessment and survival status at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. The data overall indicate poor control by ICI alone and similar outcome in patients treated with SRT with or without ICI. Complete MRI sequences during follow-up for post hoc review were available for 43 patients. Patients who did not undergo MRI, but who deteriorated clinically were not taken into account for this analysis since no RECIST or imaging only assessment could be performed on these patients. Representative patients illustrating some of the challenges are shown in figure 2. Assessment of local response of SRT targets in groups 2 and 3 revealed very few complete responses (CRs) and comparable overall response rates that did not differ using RECIST or RANO criteria. Fewer progressive disease (PD) were observed when using iRANO criteria in both groups since iRANO requires a confirmatory scan in patients with apparently worse MRI who are clinically stable (table 3). Similar results were obtained when using RECIST or RANO regarding the overall brain response. Less PD were also noted when using iRANO criteria.

Figure 2.

Response patterns. (A) Pseudoprogression: a 65-year-old man treated with SRT (6×5 Gy) to the surgical bed in April 2017, followed by four cycles of ipilimumab from April to July 2017. (B) Radionecrosis: A 57-year-old woman treated with SRT (5×5) February to March 2013, followed by four cycles of ipilimumab from February to April 2013. (C) CR: A 35-year-old woman treated with SRT (1×20 Gy) in February 2016, followed by three cycles of pembrolizumab. Gy, Grey; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy.

Table 3.

Radiological response assessment by central review (for patients without treatment changes and with available MRI scans): response at 3 months and 6 months for SRT targets and overall brain

| All patients | Group 1 | Group 2 | Group 3 | |

| ICI alone | SRT without or with non-ICI pharmacotherapy | ICI plus SRT | ||

| MRI response for SRT targets in groups 2 and 3 at 3 months | (n=36)* | n.a. | (n=11)* | (n=25)* |

| Local assessment (n, %) (n= | ||||

| PD | 6 (15) | n.a. | 2 (13) | 4 (16) |

| SD | 15 (37) | 6 (40) | 9 (36) | |

| PR/CR | 15 (37) | 6 (40) | 9 (36) | |

| data incomplete | 4 (10) | 1 (7) | 3 (12) | |

| (n=40)† | (n=15)† | (n=25)† | ||

| RECIST V.1.1 (MRI only) (n, %) (n=40) | ||||

| PD | 7 (19) | n.a. | 3 (27) | 4 (16) |

| SD | 8 (22) | 2 (18) | 6 (24) | |

| PR | 10 (27) | 4 (36) | 6 (24) | |

| CR | 2 (5) | 0 | 2 (8) | |

| Data incomplete | 9 (25) | 2 (18) | 7 (28) | |

| RANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 8 (22) | n.a. | 3 (27) | 5 (20) |

| SD | 7 (19) | 2 (18) | 5 (20) | |

| PR | 10 (27) | 4 (36) | 6 (24) | |

| CR | 2 (5) | 0 | 2 (8) | |

| Data incomplete | 9 (25) | 2 (18) | 7 (28) | |

| iRANO (considering MRI only) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SD | 16 (44) | n.a. | 6 (54) | 10 (40) |

| PR | 10 (28) | 4 (36) | 6 (24) | |

| CR | 2 (1) | 0 | 2 (8) | |

| Data incomplete | 8 (22) | 1 (9) | 7 (28) | |

| iRANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 2 (5) | n.a. | 1 (9) | 1 (4) |

| SD | 14 (39) | 5 (45) | 9 (36) | |

| PR | 10 (28) | 4 (36) | 6 (24) | |

| CR | 2 (5) | 0 | 2 (8) | |

| Data incomplete | 8 (22) | 1 (9) | 7 (28) | |

| MRI response for overall brain at 3 months | (n=39)* | (n=3)* | (n=11)* | (n=25)* |

| Local assessment (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 13 (30) | 1 (33) | 5 (33) | 7 (22) |

| SD | 13 (30) | 2 (66) | 4 (27) | 7 (22) |

| PR/CR | 17 (39) | 0 | 6 (40) | 11 (34) |

| Data incomplete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (n=43)† | (n=3)† | (n=15)† | (n=25)† | |

| RECIST V.1.1 (MRI only) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 12 (31) | 2 (66) | 4 (36) | 6 (24) |

| SD | 10 (26) | 0 | 3 (27) | 7 (28) |

| PR | 10 (26) | 0 | 4 (36) | 6 (24) |

| CR | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Data incomplete | 5 (13) | 1 (33) | 0 | 4 (16) |

| RANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 12 (31) | 2 (66) | 4 (36) | 6 (24) |

| SD | 10 (26) | 0 | 3 (27) | 7 (28) |

| PR | 10 (26) | 0 | 4 (36) | 6 (24) |

| CR | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Data incomplete | 5 (13) | 1 (33) | 0 | 4 (16) |

| iRANO (considering MRI only) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 7 (18) | 2 (66) | 2 (18) | 3 (12) |

| SD | 15 (38) | 0 | 5 (45) | 10 (40) |

| PR | 10 (26) | 0 | 4 (36) | 6 (24) |

| CR | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Data incomplete | 5 (13) | 1 (33) | 0 | 4 (16) |

| iRANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 8 (20) | 2 (66) | 3 (27) | 3 (12) |

| SD | 14 (36) | 0 | 4 (36) | 10 (40) |

| PR | 10 (26) | 0 | 4 (36) | 6 (24) |

| CR | 2 (5) | 0 | 0 | 2 (8) |

| Data incomplete | 5 (13) | 1 (33) | 0 | 4 (16) |

| MRI response (for SRT targets in groups 2 and 3) at 6 months | (n=20)* | (n=8)* | (n=12)* | |

| Local assessment (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 1 (4) | n.a. | 0 | 1 (8) |

| SD | 9 (39) | 5 (45) | 4 (33) | |

| PR/CR | 10 (43) | 5 (45) | 5 (4) | |

| Data incomplete | 2 (9) | 1 (9) | 2 (17) | |

| (n=23)† | (n=11)† | (n=12)† | ||

| RECIST 1.1 (MRI only) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 2 (10) | n.a. | 2 (18) | 0 |

| SD | 4 (20) | 1 (12) | 3 (25) | |

| PR | 7 (35) | 4 (50) | 3 (25) | |

| CR | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (25) | |

| Data incomplete | 4 (20) | 1 (12) | 3 (25) | |

| RANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 2 (10) | n.a. | 2 (18) | 0 |

| SD | 4 (20) | 1 (12) | 3 (25) | |

| PR | 7 (35) | 4 (50) | 3 (25) | |

| CR | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (25) | |

| Data incomplete | 4 (20) | 1 (12) | 3 (25) | |

| iRANO (considering MRI only) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| SD | 7 (35) | n.a. | 4 (50) | 3 (25) |

| PR | 7 (35) | 4 (50) | 3 (25) | |

| CR | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (25) | |

| Data incomplete | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (25) | |

| (n=20) | (n=8) | (n=12) | ||

| iRANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 1 (5) | n.a. | 1 (12) | 0 |

| SD | 6 (30) | 3 (37) | 3 (25) | |

| PR | 7 (35) | 4 (50) | 3 (25) | |

| CR | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (25) | |

| Data incomplete | 3 (15) | 0 | 3 (25) | |

| (n=20) | (n=8) | (n=12) | ||

| MRI response for overall brain at 6 months | (n=21)* | (n=1)* | (n=8)* | (n=12)* |

| Local assessment (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 4 (17) | 1 (100) | 2 (18) | 1 (0.5) |

| SD | 10 (42) | 0 | 5 (45) | 5 (42) |

| PR/CR | 10 (42) | 0 | 4 (36) | 6 (50) |

| Data incomplete | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (n=24)† | (n=1)† | (n=11)† | (n=12)† | |

| RECIST V.1.1 (MRI only) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 3 (14) | 0 | 3 (37) | 0 |

| SD | 7 (33) | 0 | 2 (25) | 5 (42) |

| PR | 6 (28) | 0 | 3 (37) | 3 (25) |

| CR | 3 (14) | 0 | 0 | 3 (25) |

| Data incomplete | 2 (9) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| RANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 3 (14) | 0 | 3 (37) | 0 |

| SD | 7 (33) | 0 | 2 (25) | 5 (42) |

| PR | 6 (28) | 0 | 3 (37) | 3 (25) |

| CR | 3 (14) | 0 | 0 | 3 (25) |

| Data incomplete | 2 (9) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| iRANO (considering MRI only) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 2 (9) | 0 | 2 (25) | 0 |

| SD | 8 (38) | 0 | 3 (37) | 5 (42) |

| PR | 6 (28) | 0 | 3 (37) | 3 (25) |

| CR | 3 (14) | 0 | 0 | 3 (25) |

| Data incomplete | 2 (9) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (8) |

| iRANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n, %) | ||||

| PD | 2 (9) | 0 | 2 (25) | 0 |

| SD | 8 (38) | 0 | 3 (37) | 5 (42) |

| PR | 6 (28) | 0 | 3 (37) | 3 (25) |

| CR | 3 (14) | 0 | 0 | 3 (25) |

| Data incomplete | 2 (9) | 1 (100) | 0 | 1 (8) |

*Number of MRI scans available for central review.

†Number of patients evaluated locally.

CR, complete response; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition; iRANO, immunotherapy response assessment in neuro-oncology; n, number of patients; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RANO, response assessment in neuro-oncology; RECIST, response evaluation criteria in solid tumours; SD, stable disease; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy.

Retrospective evaluation of best response

For SRT targets, CR was the best response in six patients and partial response (PR) was the best response in eight patients across criteria used. CRs were only observed in group 3. One patient had clinical deterioration without MRI progression at the first scan which accounts for the higher rate of PD as best response with RANO versus RECIST. The rates of CR and PR as best response in irradiated patients for overall whole brain were identical to those for the stereotactic radiosurgery targets, suggesting that patients who respond to SRT locally rarely show distant progression at this time point. Formally, when MRI iRANO criteria were used, 7 patients (11%) showed PD as the best response versus 11 patients (18%) had PD as the best response using RECIST or RANO criteria (table 4).

Table 4.

Radiological response assessment by central review (for patients without treatment changes and with available MRI scans): best response

| All patients | Group 1 ICI alone |

Group 2 SRT without or with non-ICI pharmacotherapy |

Group 3 ICI plus SRT |

|

| Best MRI response for SRT targets in groups 2 and 3 | (n=40)* | (n=15)* | (n=25)* | |

| Local assessment (n=52)† | ||||

| PD | 10 (19) | n.a. | 4 (20) | 6 (19) |

| SD | 20 (38) | 7 (35) | 13 (41) | |

| PR/CR | 18 (35) | 8 (40) | 10 (31) | |

| Data unavailable | 4 (8) | 1 (5) | 3 (9) | |

| RECIST V.1.1 (MRI only) (n=40) | ||||

| PD | 7 (17) | n.a. | 3 (20) | 4 (16) |

| SD | 8 (20) | 2 (13) | 6 (24) | |

| PR | 7 (17) | 4 (27) | 3 (12) | |

| CR | 6 (15) | 0 | 6 (24) | |

| Data unavailable | 12 (30) | 6 (40) | 6 (24) | |

| RANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n=40) | ||||

| PD | 9 (2) | n.a. | 4 (27) | 5 (20) |

| SD | 6 (15) | 2 (13) | 4 (16) | |

| PR | 7 (16) | 4 (27) | 3 (12) | |

| CR | 6 (15) | 0 | 6 (24) | |

| Data unavailable | 12 (30) | 5 (33) | 7 (28) | |

| iRANO (considering MRI only) (n=40) | ||||

| PD | 0 | n.a. | 0 | 0 |

| SD | 15 (37) | 6 (40) | 9 (36) | |

| PR | 8 (20) | 5 (33) | 3 (12) | |

| CR | 6 (15) | 0 | 6 (24) | |

| Data unavailable | 11 (27) | 4 (27) | 7 (28) | |

| iRANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n=40) | ||||

| PD | 3 (7) | n.a. | 2 (10) | 1 (4) |

| SD | 14 (35) | 5 (33) | 8 (32) | |

| PR | 7 (17) | 4 (27) | 3 (12) | |

| CR | 6 (15) | 0 | 6 (24) | |

| Data unavailable | 11 (27) | 4 (27) | 7 (28) | |

| Best MRI response for overall brain | (n=43) | (n=3) | (n=15) | (n=25) |

| Local assessment (n=62)† | ||||

| PD | 24 (39) | 6 (60) | 8 (40) | 10 (31) |

| SD | 15 (24) | 2 (20) | 4 (20) | 9 (28) |

| PR/CR | 19 (31) | 0 | 7 (35) | 12 (37) |

| Data unavailable | 4 (6) | 2 (20) | 1 (5) | 1 (3) |

| RECIST V.1.1 (MRI only) (n=43) | ||||

| PD | 13 (30) | 2 (66) | 5 (33) | 6 (24) |

| SD | 9 (21) | 0 | 3 (20) | 6 (24) |

| PR | 7 (16) | 0 | 4 (27) | 3 (12) |

| CR | 6 (14) | 0 | 0 | 6 (24) |

| Data incomplete | 8 (19) | 1 (33) | 3 (20) | 4 (16) |

| RANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n=43) | ||||

| PD | 13 (30) | 2 (67) | 5 (33) | 6 (24) |

| SD | 9 (1) | 0 | 3 (20) | 6 (24) |

| PR | 7 (16) | 0 | 4 (27) | 3 (12) |

| CR | 6 (14) | 0 | 0 (0) | 6 (24) |

| Data unavailable | 8 (19) | 1 (33) | 3 (20) | 4 (16) |

| iRANO (considering MRI only) (n=43) | ||||

| PD | 8 (13) | 2 (67) | 3 (20) | 3 (12) |

| SD | 13 (21) | 0 | 4 (27) | 9 (36) |

| PR | 8 (13) | 0 | 5 (33) | 3 (12) |

| CR | 6 (10) | 0 | 0 | 6 (24) |

| Data unavailable | 8 (19) | 1 (33) | 3 (20) | 4 (16) |

| iRANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) (n=43) | ||||

| PD | 8 (13) | 2 (67) | 3 (20) | 3 (12) |

| SD | 13 (30) | 0 | 4 (27) | 9 (36) |

| PR | 8 (19) | 0 | 5 (33) | 3 (12) |

| CR | 6 (14) | 0 | 0 | 6 (24) |

| Data unavailable | 8 (19) | 1 (33) | 3 (20) | 4 (16) |

| Pseudoprogression and radionecrosis | (n=43) | (n=0) | (n=15) | (n=25) |

| Pseudoprogression (n, %) | 7 (16) | 0 | 3 (20) | 4 (16) |

| Detected first on MRI at | ||||

| 3 months | 4 (57) | 0 | 3 (100) | 1 (25) |

| 6 months | 3 (43) | 0 | 0 | 3 (75) |

| 9 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Radionecrosis (n, %) | 7 (16) | 0 | 2 (13) | 5 (20) |

| Detected first on MRI at | ||||

| 3 months | 6 (86) | 0 | 1 (50) | 5 (100) |

| 6 months | 1 (14) | 0 | 1 (50) | 0 (0) |

| 9 months | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| 12 months | 0 | 0 | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

*Number of MRI scans available for central review.

†Number of patients evaluated locally.

CR, complete response; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition; iRANO, immunotherapy response assessment in neuro-oncology; n, number of patients; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RANO, Response assessment in neuro-oncology; RECIST, Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours; SD, stable disease; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy

Pseudoprogression and radionecrosis

We noted seven instances of pseudoprogression, three patients in group 2 and four patients in group 3, all within 6 months. It appeared to be more common in patients with cystic lesions. No patient diagnosed with pseudoprogression achieved a CR without further intervention subsequently. Radionecrosis occurred in seven patients, too, two in group 2 and five in group 3, again all within 6 months. It appeared to be more common in patients with a BM diameter above 30 mm (online supplementary table S5). The seven patients with pseudoprogression were different from the seven patients with radionecrosis.

We also compared the effects of single fraction (n=27) versus multiple fraction (n=25) SRT. Pseudoprogression was more common after single fraction SRT than after multiple fraction SRT: five of seven patients with pseudoprogression had received single fraction SRT, three SRT alone and two SRT plus ICI. In contrast, only two of the seven patients with pseudoprogression had received multiple fraction SRT, both in combination with ICI. Radionecrosis was also more common after single fraction SRT than after multiple fraction SRT: five of seven patients with radionecrosis had received single fraction SRT, two SRT alone and three SRT plus ICI. In contrast, only two of the seven patients with radionecrosis had received multiple fraction SRT, both in combination with ICI.

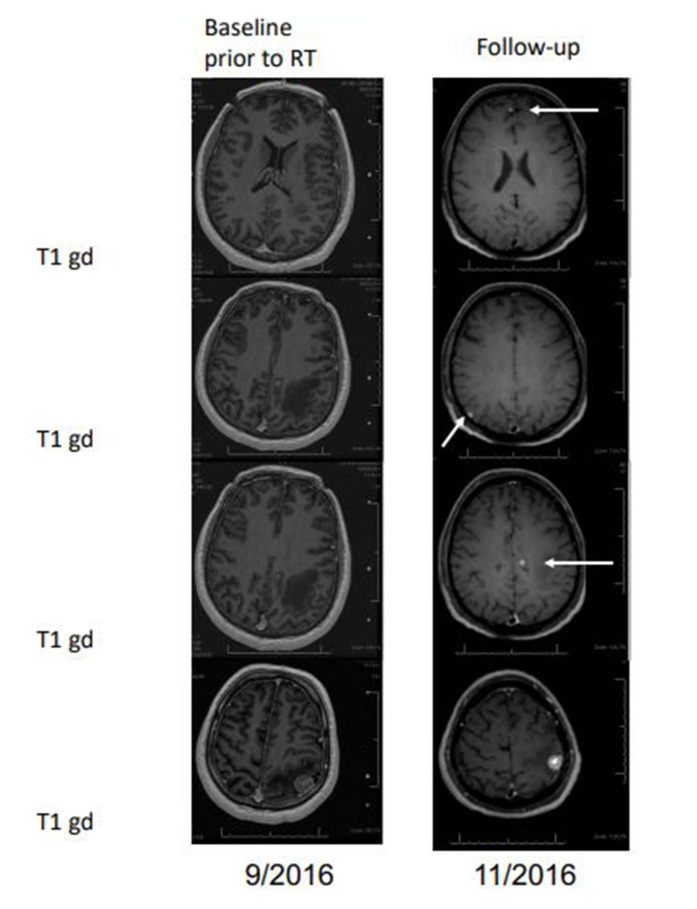

Abscopal effects

No evidence for abscopal effects of SRT were seen. Only two group 2 patients had more BM than those treated by SRT, three BM but only two treated or six BM but only three treated; both patients had global brain PD at 3 months whereas the treated SRT lesions were stable or progressive, too (figure 3). Further, we compared the 10 patients treated by ICI alone (group 1) with 5 patients of group 3 who had more BM lesions than SRT targets. There were no responses in group 1. Similarly, none of the five patients who did not have SRT to all lesions showed a response of a non-irradiated lesion, but these patients may present a priori a negative selection because they also showed poor control of their irradiated lesions (table 5). Finally, one might argue that the rate of new BM after initial treatment might provide weak evidence for abscopal effects: in that regard, we noted 6 new BM (60%) after a median of 2 months in group 1, 11 new BM (55%) after a median of 3.9 months in group 2, and 12 new BM including one case of LM (37.5%) after a median of 3.7 months in group 3.

Figure 3.

Absence of abscopal effects (case presentation). Stable disease of stereotactic radiotherapy (SRT) treated lesion (bottom panel), but detection of new lesions at first follow-up (arrows).

Table 5.

Exploration of the abscopal effect: best brain response for the overall brain

| All patients (n=15) | Group 1 ICI alone (n=10) |

Group 3' ICI plus SRT: patients with more BM than SRT targets (n=5) |

|

| Local assessment (n, %) | |||

| PD | 3 (20) | 1 (10) | 2 (40) |

| SD | 3 (20) | 2 (20) | 1 (20) |

| PR/CR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Data incomplete | 9 (60) | 7 (70) | 2 (40) |

| (9 PD prior to 3 months) | (7 PD prior to 3 months) | (2 PD prior to 3 months) | |

| RECIST V.1.1 (MRI only) | |||

| PD | 5 (23) | 2 (20) | 3 (60) |

| SD | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Data incomplete | 10 (67) | 8 (80) | 2 (40) |

| (9 PD prior to 3 months) | (7 PD prior to 3 months) | (2 PD prior to 3 months) | |

| RANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) | |||

| PD | 5 (23) | 2 (20) | 3 (60) |

| SD | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| PR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Data incomplete | 10 (67) | 8 (80) | 2 (40) |

| (9 PD prior to 3 months) | (7 PD prior to 3 months) | (2 PD prior to 3 months) | |

| iRANO (considering MRI only) | |||

| PD | 3 (20) | 2 (20) | 1 (20) |

| SD | 2 (13) | 0 | 2 (40) |

| PR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Data incomplete | 10 (67) | 8 (80) | 2 (40) |

| (9 PD prior to 3 months) | (7 PD prior to 3 months) | (2 PD prior to 3 months) | |

| iRANO (MRI, clinical, steroids) | |||

| PD | 3 (20) | 2 (20) | 1 (20) |

| SD | 2 (13) | 0 | 2 (40) |

| PR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| CR | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Data incomplete | 10 (67) | 8 (80) | 2 (40) |

| (9 PD prior to 3 months) | (7 PD prior to 3 months) | (2 PD prior to 3 months) | |

BM, brain metastasis; CR, complete response; ICI, immune checkpoint inhibition; iRANO, immunotherapy response assessment in neuro-oncology; n, number of patients; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; RANO, response assessment in neuro-oncology; RECIST, response evaluation criteria in solid tumours; SD, stable disease; SRT, stereotactic radiotherapy.

Discussion

Clinical decision making and response assessment in patients with BM from melanoma remain challenging, notably if systemic therapy and SRT are combined. Several series of patients with melanoma and lung cancer with BM treated with SRT or ICI or their combination have recently been reported,1 4–6 12–18 but the best timing and sequencing of these treatments remains controversial. Here we retrospectively applied different sets of response criteria to a cohort of 62 such patients from two centres to investigate current patterns of decision making and the potential usefulness of RECIST versus RANO versus iRANO criteria in this setting. Outcome was inferior in patients treated with ICI alone than in patients receiving SRT alone or in combination with systemic therapy, and CRs were only observed in group 3 patients that had SRT combined with ICI (figure 1, tables 2 and 3). The higher rate of LM in operated patients supports the development of surgical strategies seeking to avoid this complication.

Assessment of SRT-treated targets revealed low CR and similar overall response rates independent of criteria used. Using RANO instead of RECIST may increase the rate of early PD because clinical deterioration was occasionally noted in patients with MRI findings that did not yet qualify for PD (data not shown). Application of iRANO criteria lowers the early PD rate because of the requirement for a confirmatory scan in patients with suspected MRI progression who are clinically stable (table 3).

The absence of pseudoprogression in patients treated with ICI alone suggests that an increase in lesion size in such patients should commonly trigger a change in management, for example, probably SRT in most instances. The numerically lower rate of pseudoprogression in group 3 versus group 2 also does not support concerns regarding our capability to determine response in ICI-treated patients. Not surprisingly, the rate of pseudoprogression and radionecrosis were higher after single fraction compared with multiple fraction SRT.

Abscopal effects remain to be discussed in the context of BM treated with SRT, but clinical evidence is virtually absent. We identified only two patients treated with SRT alone who did not have SRT to all lesions. These are the ideal patients to explore abscopal effects, and there were none. Supportive evidence for abscopal effects could also be derived if patients treated with SRT for some lesions combined with ICI showed a better overall brain response than patients treated with ICI alone. However, we saw no response of non-irradiated lesions in any of five such patients, providing no evidence for abscopal effects of SRT when combined with ICI either.

This report has major limitations, including its retrospective nature associated with lack of standardised delivery of SRT (single fraction in Lille vs multiple fractions in Zurich), lack of standardised follow-up, the small sample size per group and the uncontrolled assignment of treatment. Its strength may be the identification of shortcomings in the currently applied response criteria which may guide the continuous efforts of improving and standardise how we monitor patients with BM by clinical and neuroimaging assessment. The survival data observed here may support recent concerns that the omission of SRT from first-line treatment may compromise outcome.19

Footnotes

Contributors: ELR, MW: designed and conceptualised the study; were involved with acquisition of data; analysed the data; drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. FW, MF: were involved with acquisition of data; analysed the data; revised the manuscript for intellectual content. PD: designed and conceptualised the study; analysed the data; drafted the manuscript for intellectual content. NA, NR, LR, RD, LM: analysed the data; revised the manuscript for intellectual content.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board in Zurich (2018–00192). A declaration to the Commission Nationale de l'Informatique et des Libertés, an independent French administrative authority, was made on 09 November 2017.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: No data are available.

References

- 1.Liew DN, Kano H, Kondziolka D, et al. . Outcome predictors of gamma knife surgery for melanoma brain metastases. Clinical article. J Neurosurg 2011;114:769–79. 10.3171/2010.5.JNS1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davies MA, Saiag P, Robert C, et al. . Dabrafenib plus trametinib in patients with BRAFV600-mutant melanoma brain metastases (COMBI-MB): a multicentre, multicohort, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:863–73. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30429-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McArthur GA, Maio M, Arance A, et al. . Vemurafenib in metastatic melanoma patients with brain metastases: an open-label, single-arm, phase 2, multicentre study. Ann Oncol 2017;28:634–41. 10.1093/annonc/mdw641 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Long GV, Atkinson V, Lo S, et al. . Combination nivolumab and ipilimumab or nivolumab alone in melanoma brain metastases: a multicentre randomised phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:672–81. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30139-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tawbi HA, Forsyth PA, Algazi A, et al. . Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab in melanoma metastatic to the brain. N Engl J Med 2018;379:722–30. 10.1056/NEJMoa1805453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schvartsman G, Ma J, Bassett RL, et al. . Incidence, patterns of progression, and outcomes of preexisting and newly discovered brain metastases during treatment with anti-PD-1 in patients with metastatic melanoma. Cancer 2019;125:4193–202. 10.1002/cncr.32454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Okada H, Weller M, Huang R, et al. . Immunotherapy response assessment in neuro-oncology: a report of the RANO Working group. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:e534–42. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00088-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. . New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer 2009;45:228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lin NU, Lee EQ, Aoyama H, et al. . Response assessment criteria for brain metastases: proposal from the RANO group. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:e270–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)70057-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Seymour L, Bogaerts J, Perrone A, et al. . iRECIST: guidelines for response criteria for use in trials testing immunotherapeutics. Lancet Oncol 2017;18:e143–52. 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30074-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sperduto PW, Jiang W, Brown PD, et al. . Estimating survival in melanoma patients with brain metastases: an update of the graded prognostic assessment for melanoma using molecular markers (Melanoma-molGPA). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2017;99:812–6. 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2017.06.2454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Queirolo P, Spagnolo F, Ascierto PA, et al. . Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab in patients with advanced melanoma and brain metastases. J Neurooncol 2014;118:109–16. 10.1007/s11060-014-1400-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.An Y, Jiang W, Kim BYS, et al. . Stereotactic radiosurgery of early melanoma brain metastases after initiation of anti-CTLA-4 treatment is associated with improved intracranial control. Radiother Oncol 2017;125:80–8. 10.1016/j.radonc.2017.08.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minniti G, Anzellini D, Reverberi C, et al. . Stereotactic radiosurgery combined with nivolumab or ipilimumab for patients with melanoma brain metastases: evaluation of brain control and toxicity. J Immunother Cancer 2019;7:102. 10.1186/s40425-019-0588-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tétu P, Allayous C, Oriano B, et al. . Impact of radiotherapy administered simultaneously with systemic treatment in patients with melanoma brain metastases within MelBase, a French multicentric prospective cohort. Eur J Cancer 2019;112:38–46. 10.1016/j.ejca.2019.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stera S, Balermpas P, Blanck O, et al. . Stereotactic radiosurgery combined with immune checkpoint inhibitors or kinase inhibitors for patients with multiple brain metastases of malignant melanoma. Melanoma Res 2019;29:187–95. 10.1097/CMR.0000000000000542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rauschenberg R, Bruns J, Brütting J, et al. . Impact of radiation, systemic therapy and treatment sequencing on survival of patients with melanoma brain metastases. Eur J Cancer 2019;110:11–20. 10.1016/j.ejca.2018.12.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martins F, Schiappacasse L, Levivier M, et al. . The combination of stereotactic radiosurgery with immune checkpoint inhibition or targeted therapy in melanoma patients with brain metastases: a retrospective study. J Neurooncol 2020;146:181–93. 10.1007/s11060-019-03363-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kruser TJ, Gondi V, Sperduto PW, et al. . Omitting radiosurgery in melanoma brain metastases: a drastic and dangerous de-escalation. Lancet Oncol 2018;19:e366. 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30439-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

esmoopen-2020-000763supp001.pdf (126.9KB, pdf)