Abstract

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is associated with endothelial inflammation and a hypercoagulable state resulting in both venous and arterial thromboembolic complications. We present a case of COVID-19-associated aortic thrombus in an otherwise healthy patient.

Case Report

A 53-year-old woman with no past medical history presented with a 10-day history of dyspnea, fever, and cough. Her pulse oximetry on room air was 84%. She tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 infection, and chest radiography revealed moderate patchy bilateral airspace opacities. Serology markers for cytokine storm were significantly elevated, with a serum D-dimer level of 8180 ng/mL (normal < 230 ng/mL). Computed tomography of the chest with i.v. contrast was positive for bilateral ground-glass opacities, scattered filling defects within the bilateral segmental and subsegmental pulmonary arteries, and a large thrombus was present at the aortic arch. The patient was admitted to the intensive care unit and successfully treated with unfractionated heparin, alteplase 50 mg, and argatroban 2 μg/kg/min.

Why Should an Emergency Physician Be Aware of This?

Mural aortic thrombus is a rare but serious cause of distal embolism and is typically discovered during an evaluation of cryptogenic arterial embolization to the viscera or extremities. Patients with suspected hypercoagulable states, such as that encountered with COVID-19, should be screened for thromboembolism, and when identified, aggressively anticoagulated.

Keywords: COVID-19, aortic thrombus, arterial thromboembolism, hypercoagulable state

Introduction

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has affected more than 20 million humans globally and caused over 164,000 deaths in the United States alone. Up to 20% of all COVID-19 patients require hospitalization, and 10% may develop severe symptoms that will require admission to an intensive care unit and mechanical ventilation (1). From initial reports, it has become clear that a large percentage of these critically ill patients develop a prothrombotic state that has been attributed to a variety of factors, including antiphospholipid antibodies and vascular endothelial inflammation (endotheliitis) (2,3). We report the case of a patient who presented to our institution with severe acute respiratory syndrome due to COVID-19, complicated by a large-vessel thrombosis.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 53-year-old woman presented with dyspnea, fever, and cough that had started approximately 10 days prior to her hospitalization. The patient tested positive for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection. In the Emergency Department she was noted to be afebrile but hypoxic. Oxygen saturation was 84% on room air, improving to 88% with a nasal cannula and to 98% with a nonrebreather mask. Initial blood tests showed a serum D-dimer level of 8180 ng/mL (normal < 230 ng/mL), activated partial thromboplastin time 33.5 s (normal 27.5–35.5 s), prothrombin time 12.2 s (normal 10.6–13.6 s), international normalized ratio 1.08 (normal 0.88–1.16 ratio), and platelet count 281 × 109/L (normal 150–400 K/uL). Serum ferritin level peaked at 1058 ng/mL (normal, 15–150 ng/mL) and C-reactive protein at 10.04 mg/dL (normal < 0.4 mg/dL). Chest x-ray study revealed moderate patchy bilateral airspace opacities, worse in the mid to lower lungs. Computed tomography examination of the chest revealed severe bilateral ground-glass opacities in the lungs with some subpleural sparing and a more consolidative appearance at the bilateral lower lobes (Figures 1 A and 1B). There was no pleural effusion. There were scattered filling defects within the bilateral segmental and subsegmental pulmonary arteries, with a mild to moderate clot burden. The heart was within normal limits in size, with no evidence of right heart strain. A large thrombus was present at the aortic arch (Figures 2 A and 2B). The ascending and descending aorta were not enlarged, with no evidence of atherosclerosis or vessel wall abnormality. The aortic arch had atherosclerotic plaque at the site of thrombus without evidence of penetrating ulcer. There were no signs of central nervous system, hepatic, renal, splenic, or peripheral embolization. A thrombus was also seen in the suprahepatic inferior vena cava (Figure 2C). Venous duplex of the lower extremities did not reveal any evidence of deep venous thrombosis. The patient was treated with hydroxychloroquine 400 mg/day, azithromycin 250 mg/day, unfractionated heparin, alteplase 50 mg, and argatroban 2 μg/kg/min, with partial resolution of the thrombus on follow-up computed tomography and no in-hospital adverse events.

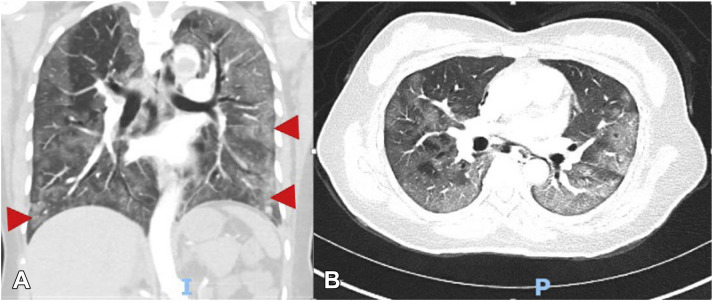

Figure 1.

Chest computed tomography with (A) sagittal and (B) coronal views showing ground-glass opacities (arrows).

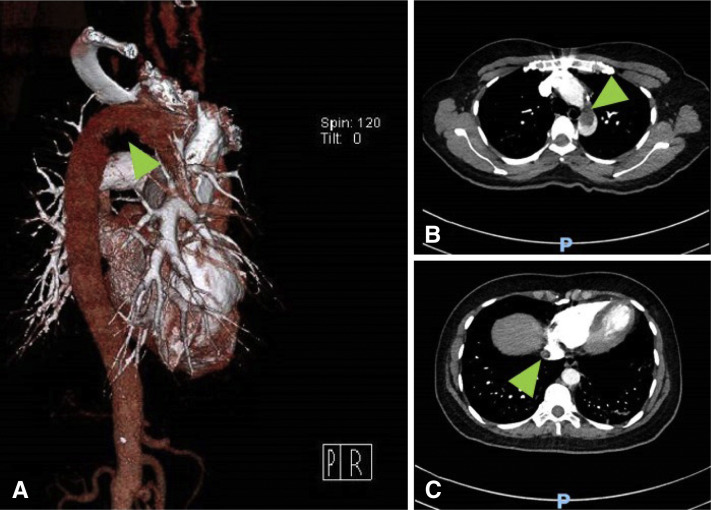

Figure 2.

(A) Computed tomography (CT) with three-dimensional reconstruction of the aortic arch with a filling defect (arrow). (B) Coronal view of the chest, with a large thrombus present in the aortic arch (arrow). (C) CT of the chest with a thrombus seen in the suprahepatic portion of the inferior vena cava (arrow).

Discussion

COVID-19 has a broad range of clinical manifestations. Although initially described as a respiratory disease resulting in severe and progressive respiratory failure, a disproportionate number of patients have developed cardiovascular involvement across different organs and multiple vascular beds. Case reports and observational cohort studies support both a hypercoagulable state and a thrombo-inflammatory response associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Blood coagulation derangements including elevated D-dimer, fibrinogen, and fibrin degradation products, as well as low antithrombin levels compared with a healthy control population, are documented (4). D-dimer elevations more than 1000 ng/mL have been associated with increased COVID-19 mortality (5). Although there are no set cut-off values for the work-up of active thromboembolic disease in patients with COVID-19, a single-center retrospective study suggested that a D-dimer cutoff of > 3000 ng/mL predicted venous thromboembolism with a sensitivity, specificity, and negative predictive value of 76.9%, 94.9%, and 92.5%, respectively (6).

The incidence of venous thromboembolism during COVID-19 infection is reported as high as 25%, and arterial vascular events in up to 4% (7,8). Kashi et al. reported seven cases of severe arterial thrombosis, including two COVID-19 patients with asymptomatic floating thoracic aortic thrombi (9). Hypercoagulable states are commonly identified in patients with aortic mural thrombus (10).

There are numerous therapeutic options for the management of aortic mural thrombus. However, no definitive consensus on treatment of aortic thrombus exists. Fayad et al. found that patients receiving anticoagulation, either as the primary treatment modality or after aortic surgery, were less likely to experience recurrent peripheral embolic events (odds ratio 0.3; 95% confidence interval 0.1–1) (10). An anticoagulation first approach is recommended in the setting of mild distal organ involvement (11).

Pharmacological thrombosis prophylaxis and treatment in all COVID-19 patients have been empiric and vary across institutions. Until further data are available, COVID-19 patients with embolic complications should be screened and aggressively treated for possible large-vessel thrombosis.

Why Should an Emergency Physician Be Aware of This?

Mural aortic thrombus is a rare but serious cause of distal embolism, and is typically discovered during an evaluation of cryptogenic arterial embolization to the viscera or extremities. Patients with suspected hypercoagulable states, such as that encountered with COVID-19, should be aggressively anticoagulated and referred to endovascular services.

References

- 1.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with COVID-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e38. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Varga Z., Flammer A.J., Steiger P. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet. 2020;395:1417–1418. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han H., Yang L., Liu R. Prominent changes in blood coagulation of patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2020;58:1116–1120. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui S., Chen S., Li X. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18:1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bompard F., Monnier H., Saab I. Pulmonary embolism in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2001365. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01365-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J., van der Meer N.J. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID-19. Thromb Res. 2020;191:145–147. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kashi M., Jacquin A., Dakhil B. Severe arterial thrombosis associated with COVID-19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;192:75–77. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fayad Z.Y., Semaan E., Fahoun B. Aortic mural thrombus in the normal or minimally atherosclertic aorta. Ann Vasc Surg. 2013;27:282–290. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2012.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reyes Valdivia A., Duque Santos A., Garnica Ureña M. Anticoagulation alone for aortic segment treatment in symptomatic primary aortic mural thrombus patients. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;43:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]