Abstract

Objective:

To assess the clinical utility of the adjusted Global AntiphosPholipid Syndrome Score (aGAPSS) in determining the recurrent thrombosis risk in antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) patients.

Methods:

In this cross-sectional study of antiphospholipid antibody (aPL)-positive patients, we identified APS patients with history of documented thrombosis from the AntiPhospholipid Syndrome Alliance For Clinical Trials and InternatiOnal Networking (APS ACTION) Clinical Database and Repository (“Registry”). Data on aPL-related medical history and cardiovascular risk factors were retrospectively collected. The aGAPSS was calculated at registry entry by adding the points corresponding to the risk factors: three for hyperlipidemia, one for arterial hypertension, five for positive anticardiolipin antibodies, four for positive anti-β2 glycoprotein-I antibodies; and four for positive lupus anticoagulant test.

Results:

The analysis included 379 APS patients who presented with arterial and/or venous thrombosis. Overall, significantly higher aGAPSS were seen in patients with recurrent thrombosis (arterial or venous) compared to those without recurrence (7.8±3.3 vs. 6±3.9, p<0.05). When analyzed based on the site of the recurrence, patients with recurrent arterial, but not venous, thrombosis had higher aGAPSS (8.1 ±SD 2.9 vs. 6±3.9; p<0.05).

Conclusions:

Based on analysis of our international large-scale registry of aPL-positive patients, the aGAPSS might be able to help risk stratifying patients based on the likelihood of developing recurrent thrombosis in APS.

Keywords: Antiphospholipid Syndrome, Antiphospholipid Antibodies, GAPSS, APS ACTION, thrombosis, Clinical Database, Risk Stratification

Introduction:

The current Antiphospholipid Syndrome (APS) classification criteria [1] are useful in clinical research, however, identifying patients with antiphospholipid antibodies (aPL) who are at higher risk for thrombosis and/or pregnancy morbidity remains an unmet clinical need and a major challenge in clinical practice.Recently, the global APS score (GAPSS), a risk score for clinical manifestations of APS, which incorporates independent cardiovascular disease risk factors and aPL profile, was developed (Table 1). Global APSScore, initially developed and validatedin systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), has been applied in a cohort of SLE patients followed prospectively, and then validated in APS patients without associated SLE [2-6]. Due to the relative low prevalence of APS in the general population, estimated as an incidence of five cases per 100,000 persons per year [7,8], APS clinical research requires international efforts and multicenter collaborations. The AntiPhospholipid Syndrome Alliance For Clinical Trials and InternatiOnal Networking (APS ACTION) is an international research network that has launched a web-based registry of aPL-positive patients with or without systemic autoimmune diseases. With these resources, our objective was to assess the clinical utility of the aGAPSS to identify patients with thrombotic APS at higher risk of recurrences using the data from the APS ACTION registry.

Table 1.

The Adjusted Global Antiphospholipid Syndrome Score (aGAPSS)

| Factor | Point Value |

|---|---|

| Anticardiolipin Antibody IgG/IgM | 5 |

| Anti-β2-glycoprotein I IgG/IgM | 4 |

| Lupus anticoagulant | 4 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 3 |

| Arterial hypertension | 1 |

Patients and methods:

Patients:

APS ACTION registry inclusion criteria have been extensively described elsewhere [9]. In brief, the inclusion criteriawere: positive lupus anticoagulant (LA) test based on the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis (ISTH) and British Committee for Standards in Haematology (BSH) recommendations [10-12] and/or medium-to-high titer anticardiolipin (aCL) and/or anti-β2 glycoprotein I (aβ2GPI) antibodies, tested at least twice 12 weeks apart within one year prior to enrolment. A secure web-based data capture system (REDCap) was used to store patient information including demographics, clinical manifestations, and aPL data [13]. Patients are followed annually with clinical data and blood collection.

Study Design:

Computed variables were collected at entry visit in the APS ACTION registry and demographic, clinical and laboratory data were retrospectively analyzed. Cardiovascular disease risk factors at registry entry (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, hormone replacement therapy, and smoking history) were retrieved from the clinical database.

The cumulative global APS score was calculated for each patient, as previously reported, by adding all points corresponding to the risk factors based on a linear transformation derived from the ß-regression coefficient (Table1) [14]. Despite much data supporting the usefulness of antiphosphatidylserine/prothrombin (aPS/PT) antibodies as a diagnostic and prognostic biomarker, these antibodies are not included as a laboratory criterion for APS or used in the routine clinical setting, and therefore, were unavailable for this study [15]. For this reason, we performed our analysis using the previously validated adjusted GAPSS or aGAPSS, which excludes aPS/PT from the computation [3].

Statistical analysis:

Categorical variables are presented as number (%) and continuous variables are presented as mean ±SD. The significance of baseline differences was determined by the chi-squared test, Fisher’s exact test or the unpaired t-test, as appropriate. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to identify any independent predictors of recurrence of thrombosis. A two-sided p-value <0.05 was considered as statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 19.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results:

Three hundred and seventy nine patients with thrombotic APS [mean age at registry entry: 47.3±11.4y, female 70%, Primary APS: 259 (68%)] were included in the analysis. Of the total 379 patients, 154 (40%) had at least one episode of documented arterial thrombosis, 199 (53%) had at least one episode of documented venous thrombosis, and 26 (7%) had at least one episode of both an arterial and a venous event.One hundred and eleven patients (29%) had a history of recurrences of thrombosis, either arterial or venous. Of them,30 patients (27%) experienced recurrences of arterial thrombosis and 65 patients (58.6%) experienced recurrences of venous thrombosis, ranging from 2 to 5 documented events. Sixteen patients (14.4%) had a history of both recurrent arterial and venous events.

The demographic, clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with or without documented recurrentthrombosis, are summarized in Table 2. In multivariate analysis, when we included each cardiovascular disease risk factor individually (i.e., dyslipidemia, arterial hypertension, age, and smoking) and aPL positivity (single, multiple, or triple), no significant differences were observed between APS patients with and without recurrent thrombosis arterial and/or venous).

Table 2.

Demographic, Clinical and Laboratory Characteristics of the Cohort

| No Recurrent Thrombosis n=268 (%) |

Recurrent Thrombosis n=111 (%) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any n=111 (%) |

Only Arterial n=30 (%) |

Only Venous n=65 (%) |

Arterial & Venous n=16 (%) |

||

| Female sex | 180 (67%) | 73 (71%) | 20 (67%) | 45 (69%) | 12 (75%) |

| Age, years, mean (±SD) | 48 (±13) | 50 (±12) | 50 (±12) | 48 (±13) | 59 (±15) |

| Arterial hypertension, n=128 | 85 (32%) | 43 (39%) | 16 (53%) | 19 (29%) | 6 (38%) |

| Hyperlipedemia, n=103 | 70 (26%) | 33 (30%) | 7 (23%) | 17 (26%) | 5 (31%) |

| Diabetes, n=18 | 14 (5%) | 4 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 3 (4%) | 0 (0%) |

| Smoking (H= history, n= 101; C= current, n= 38), | H: 71 (27%) C: 26 (9%) | H: 30 (26%) C: 12 (11%) | H: 9 (30%) C: 3 (9%) | H: 17 (26%) C: 6 (9%) | H: 4 (25%) C: 4 (25%) |

| LA, n=239 | 168 (62%) | 71 (64%) | 13 (43%) | 46 (71%) | 11 (69%) |

| aCLIgG/IgM, n=160 | 114 (42%) | 46 (51%) | 14 (47%) | 34 (52%) | 7 (43%) |

| aβ2GPI IgG/IgM, n=103 | 71 (27%) | 32 (29%) | 12 (40%) | 20 (31%) | 4 (25%) |

| Triple positive, n= 57 | 38 (14%) | 19 (17%) | 5 (16%) | 11 (17%) | 3 (19%) |

LA: Lupus anticoagulant; aCL: anticardiolipin antibodies; aβ2GPI: anti-β2-glycoprotein 1antibodies; aGAPSS: adjusted global antiphospholipid score

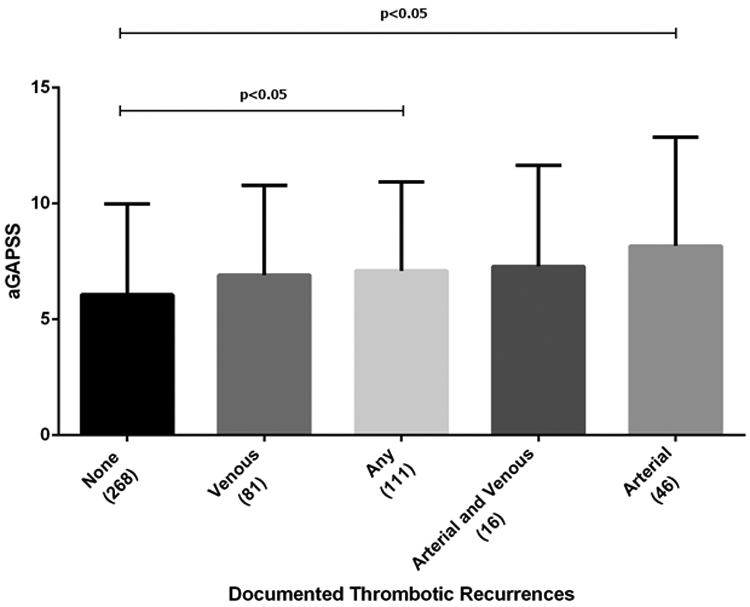

Overall, aGAPSS was significantly higher in patients with recurrent thrombosis (arterial or venous), compared to those without recurrence (7.8±3.3 vs. 6 ±3.9, p<0.05). In subgroup analysis, patients with recurrent arterial thrombosis, but not venous, had higher aGAPSS (8.1 ±2.9 vs. 6 ±3.9; p<0.05) when compared to those without recurrences (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Levels of Adjusted Global Antiphospholipid Syndrome Score Among Different Study Subgroups

Discussion

Antiphospholipid syndrome remains a clinical challenge for the physicians, and accurate thrombosis risk assessment plays a crucial part in the management of APS patients [16]. When identifying patients at higher risk of developing clinical manifestations of APS, aPL profile represents the most accurate risk stratification tool. In this study, we demonstrated the utility of aGAPSS in stratifying subgroups of patients at different thrombotic risks, finding higher levels of aGAPSS in patients with recurrent thrombosis (arterial or venous), compared to those without recurrences,and in patients who developed recurrent arterial thrombotic manifestations. Among others, Pengo et al. found that triple aPL positivity was associated with a higher risk of thrombosis in APS (13). However, in the current study, we did not demonstrate differences between each aPL profile when comparing the rate for recurrence in patients with single/double/triple positivity. Similarly, no single cardiovascular disease risk factor seemed to be independently associated with the risk of developing recurrent thrombosis. It is important to clarify that this lack of association should not be considered as a refusal of previous data since all patients recruited to this study fulfill the criteria for APS and are strictly monitored in tertiary centers, potentially representing a sampling bias when compared to other observation cohorts. In addition, these findings are in line with the concept that aPL is a necessary but insufficient step in the development of thrombosis where a “second hit” probably push the haemostatic balance in favor of thrombosis by including added factors necessary for its development, such as uncontrolled traditional cardiovascular risk factors [18,19]. Among the various methods for risk stratifications, aGAPSS displays important advantages. Firstly, scoring systems have been proven to be valid tools easily accessible for the treating clinician. Secondly, when considering the “second hit” theory, aGAPSS considers both the aPL profile (including both criteria and non-criteria aPL) and traditional cardiovascular risk factors. Although no single aPL positivity and traditional cardiovascular risk factor was found to be independently associated with an increased risk of developing recurrence of thrombosis, when computed in a scoring system, both factors contribute to the risk assessment stratification as part of the variables included in the aGAPSS score.

It is important to acknowledge the limitations for our study. First, treatment was based on the treating clinician’s judgment. Secondly, the use of a retrospective as well as the cross-sectional approach might influence the reproducibility of the results, as individual aGAPSS scores could fluctuate at different time points. Thirdly, APS ACTION registry does not include clinical information on cardiovascular risk factors at the time of the recurrent event or on other potential thrombotic risk factors. However, one should consider the fact that APS is a low prevalence condition[20] and our study comprehended one of the largest thrombotic APS cohorts. Fourth, details on different methods used in local laboratories to test aPL (e.g. type of ELISA Kit, home-made assay information) were not available. While a longitudinal study would be highly informative, a cross-sectional approach using international joint efforts represents a solid shared ground for further investigation.

In conclusion, analysis of our international large-scale registry of aPL-positive patients, the aGAPSS might help to risk stratifying patients based on the likelihood of developing recurrent thrombosis in APS.

On the one hand, scoring systems are not meant to substitute the judgment of the treating physicians. On the other, the combination ofaccessible tools for risk stratification such as aGAPSS and the APS ACTION scientific networking collaborative efforts, could aid improved management of APS patients, as more accurate identification of those a higher risk for thrombotic events would provide a basis for tailored therapeutic approaches.

Acknowledgments

Disclosure and conflict of interests

Michelle Petri’s contribution was supported by NIH RO-AR069572

Funding: None declared

Appendix

* APS ACTION Members Include:Argentina: Santa Fe (Guillermo Pons-Estel); Australia: Sydney (Bill Giannakopoulos, Steve Krilis); Brazil: Rio de Janeiro (Guilherme de Jesus, Roger Levy), São Paulo (Michelle Ugolini-Lopes, Renata Rosa, Danieli Andrade); Canada: Quebec (Paul F. Fortin); China: Beijing (Zhouli Zhang); France: Nancy (Stephane Zuily, Denis Wahl); Greece: Athens (Maria Tektonidou); Italy: Brescia (Cecilia Nalli, Laura Andreoli, Angela Tincani), Milan (Cecilia B. Chighizola, Maria Gerosa, PierluigiMeroni), Padova (Alessandro Banzato, Vittorio Pengo), Turin (Savino Sciascia); Jamaica: Kingston (Karel De Ceulaer, Stacy Davis); Japan: Sapporo (Olga Amengual, Tatsuya Atsumi); Lebanon: Beirut (Imad Uthman); Netherlands: Utrecht (Maarten Limper, Ronald Derksen, Philip de Groot); Spain:Barakaldo (AmaiaUgarte, Guillermo Ruiz Irastorza), Barcelona (Ignasi Rodriguez- Pinto, Ricard Cervera), Madrid (Esther Rodriguez,MariaCuadrado), Cordoba (Maria Angeles Aguirre Zamorano, Rosario Lopez-Pedrera); Turkey: Istanbul (Bahar Artim-Esen, Murat Inanc); United Kingdom: London (Ian Mackie, Maria Efthymiou, Hannah Cohen; and Maria Laura Bertolaccini, Munther Khamashta, Giovanni Sanna); USA: Ann Arbor (Jason S. Knight), Baltimore (Michelle Petri), Chapel Hill (Robert Roubey), Durham (Tom Ortel), Galveston (Emilio Gonzalez, Rohan Willis), New York City (Steven Levine, Jacob Rand, H. Michael Belmont; and Medha Barbhaiya, Doruk Erkan, Jane Salmon, Michael Lockshin), Salt Lake City (Ware Branch).

Footnotes

Disclosure of Conflicts of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Miyakis S, Lockshin MD, Atsumi T, Branch DW, Brey RL, Cervera R, et al. International consensus statement on an update of the classification criteria for definite antiphospholipid syndrome (APS). J Thromb Haemost [Internet]. 2006. February [cited 2016 Jul 4];4(2):295–306. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16420554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. GAPSS: the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score. Rheumatology (Oxford) [Internet]. 2013. August [cited 2016 Sep 21];52(8):1397–403. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23315788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sciascia S, Radin M, Sanna G, Cecchi I, Roccatello D, Bertolaccini ML. Clinical utility of the global anti-phospholipid syndrome score for risk stratification: a pooled analysis. Rheumatology [Internet]. 2018;(January):1–5. Available from: http://academic.oup.com/rheumatology/advance-article/doi/10.1093/rheumatology/kex466/4803081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massimo Radin, Karen Schreiber, Irene Cecchi, Roccatello Dario CMJ and SS. The risk of ischaemic stroke in primary APS patients: a prospective study. Eur J Neurol. 2017;Accepted F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Radin M, Ugolini-Lopes MR, Sciascia S, Andrade D. Extra-criteria manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: Risk assessment and management. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2018; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oku K, Amengual O, Bohgaki T, Horita T, Yasuda S, Atsumi T. An independent validation of the Global Anti-Phospholipid Syndrome Score in a Japanese cohort of patients with autoimmune diseases. Lupus [Internet]. 2015. June [cited 2016 Sep 21];24(7):774–5. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25432782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Petri M Epidemiology of Antiphospholipid Syndrome In: Hughes Syndrome. London: Springer-Verlag; 2006. p. 22–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sciascia S, Radin M, Unlu O, Erkan D, Roccatello D. Infodemiology of antiphospholipid syndrome: Merging informatics and epidemiology. Eur J Rheumatol [Internet]. 2018;5(2). Available from: http://www.eurjrheumatol.org/eng/makale/3080/214/Full-Text [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Erkan D, Lockshin M, APS ACTION members. APS ACTION - AntiPhospholipid Syndrome Alliance For Clinical Trials and InternatiOnal Networking. Lupus [Internet]. 2012. June 1 [cited 2016 Dec 22];21(7):695–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22635205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keeling D, Mackie I, Moore GW, Greer IA, Greaves M, British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Guidelines on the investigation and management of antiphospholipid syndrome. Br J Haematol [Internet]. 2012. April [cited 2018 Jul 30];157(1):47–58. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22313321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brandt JT, Triplett DA, Alving B, Scharrer I. Criteria for the diagnosis of lupus anticoagulants: an update. On behalf of the Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibody of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee of the ISTH. Thromb Haemost [Internet]. 1995. October [cited 2016 Dec 22];74(4):1185–90. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8560433 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pengo V, Tripodi A, Reber G, Rand JH, Ortel TL, Galli M, et al. Update of the guidelines for lupus anticoagulant detection. Subcommittee on Lupus Anticoagulant/Antiphospholipid Antibody of the Scientific and Standardisation Committee of the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2009. October;7(10):1737–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)—A metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform [Internet]. 2009. April [cited 2017 Oct 6];42(2):377–81. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18929686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sciascia S, Sanna G, Murru V, Roccatello D, Khamashta MA, Bertolaccini ML. The global anti-phospholipid syndrome score in primary APS. Rheumatology (Oxford) [Internet]. 2015. January [cited 2016 Sep 21];54(1):134–8. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25122726 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bertolaccini ML, Sanna G. The Clinical Relevance of Noncriteria Antiphospholipid Antibodies. Semin Thromb Hemost [Internet]. 2017. [cited 2017 Jun 9]; Available from: https://www.thieme-connect.com/products/ejournals/abstract/10.1055/s-0037-1601328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Otomo K, Atsumi T, Amengual O, Fujieda Y, Kato M, Oku K, et al. Efficacy of the antiphospholipid score for the diagnosis of antiphospholipid syndrome and its predictive value for thrombotic events. Arthritis Rheum. 2012. February;64(2):504–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pengo V, Ruffatti A, Legnani C, Gresele P, Barcellona D, Erba N, et al. Clinical course of high-risk patients diagnosed with antiphospholipid syndrome. J Thromb Haemost [Internet]. 2010. February [cited 2016 Sep 21];8(2):237–42. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19874470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meroni PL, Borghi MO, Raschi E, Tedesco F. Pathogenesis of antiphospholipid syndrome: understanding the antibodies. Nat Rev Rheumatol [Internet]. 2011. June [cited 2016 Jul 4];7(6):330–9. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21556027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Radin M, Schreiber K, Costanzo P, Cecchi I, Roccatello D, Baldovino S, et al. The adjusted Global AntiphosPholipid Syndrome Score (aGAPSS) for risk stratification in young APS patients with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol [Internet]. 2017;240:72–7. Available from: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.02.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abreu MM, Danowski A, Wahl DG, Amigo M-C, Tektonidou M, Pacheco MS, et al. The relevance of "non-criteria" clinical manifestations of antiphospholipid syndrome: 14th International Congress on Antiphospholipid Antibodies Technical Task Force Report on Antiphospholipid Syndrome Clinical Features. Autoimmun Rev. 2015. May;14(5):401–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]