Abstract

Objectives

UK Black African/Black Caribbean women remain disproportionately affected by HIV. Although oral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) could offer them an effective HIV prevention method, uptake remains limited. This study examined barriers and facilitators to PrEP awareness and candidacy perceptions for Black African/Black Caribbean women to help inform PrEP programmes and service development.

Methods

Using purposive sampling through community organisations, 32 in-depth, semi-structured interviews were conducted with Black African/Black Caribbean women living in London and Glasgow between June and August 2018. Participants (aged 19–63) included women of varied HIV statuses to explore perceptions of sexual risk and safer sex, sexual health knowledge and PrEP attitudes. A thematic analysis guided by the Social Ecological Model was used to explore how PrEP perceptions intersected with wider safer sex understandings and practices.

Results

Four key levels of influence shaping safer sex notions and PrEP candidacy perceptions emerged: personal, interpersonal, perceived environment and policy. PrEP-specific knowledge was low and some expressed distrust in PrEP. Many women were enthusiastic about PrEP for others but did not situate PrEP within their own safer sex understandings, sometimes due to difficulty assessing their own HIV risk. Many felt that PrEP could undermine intimacy in their relationships by disrupting the shared responsibility implicit within other HIV prevention methods. Women described extensive interpersonal networks that supported their sexual health knowledge and shaped their interactions with health services, though these networks were influenced by prevailing community stigmas.

Conclusions

Difficulty situating PrEP within existing safer sex beliefs contributes to limited perceptions of personal PrEP candidacy. To increase PrEP uptake in UK Black African/Black Caribbean women, interventions will need to enable women to advance their knowledge of PrEP within the broader context of their sexual health and relationships. PrEP service models will need to include trusted ‘non-sexual health-specific’ community services such as general practice.

Keywords: ethnicity, gender, HIV, HIV women, PREP

Introduction

UK black and minority ethnic (BME) populations remain disproportionately affected by HIV. Black/Black British populations comprise 42.1% of new diagnoses among heterosexual adults despite being 3.0% of the population. Among BME women, prevention efforts have stalled with little change in newly diagnosed HIV rates despite decreases in other groups (ie, men who have sex with men).1–3 These prevention disparities reflect the difficulties BME women face accessing appropriate HIV prevention, including a lack of targeted interventions to assess risk and community stigma around sexual/reproductive (SRH) health services.4 5

New biomedical interventions could prevent infections among UK BME women. Daily, oral regimes of either tenofovir or tenofovir and emtricitabine (PrEP) reduce HIV acquisition risk and represent some of the first HIV prevention tools women can autonomously control.6 All UK countries provide PrEP either through or in partnership with their national health systems. At the time of the study, PrEP was available in England through the PrEP Impact Trial, an implementation trial from NHS England and Public Health England,7 and in Scotland as part of routine sexual health services from July 2017 onward.8 In both countries, women require a clinically assessed risk commensurate to that of an HIV-negative person with a virally unsuppressed partner to be PrEP eligible.7 8

Few women use PrEP.7–9 Limited research exists on barriers to and motivations for UK BME women accessing it.4 The lack of evidence on awareness of and attitudes towards PrEP in this population and the lack of knowledge on how women situate new tools like PrEP within safer sex discourses as they navigate their own sexual health have made it difficult for clinicians, activists and policy-makers to support candidacy perceptions, uptake and adherence in those who may benefit from PrEP.

This study explored PrEP awareness and candidacy perceptions in UK BME women in London and Glasgow, the cities with the highest HIV prevalence in England and Scotland, respectively. We draw on the Social Ecological Model (SEM) to map how women understand their candidacy for PrEP in light of their safer sex practices. The SEM purports that multiple levels of an individual’s social environment influence personal health behaviours (ie, choosing which safer sex tools to use). In addition to their personal attributes, interpersonal interactions with other community members, community norms and values, and policies affecting the areas individuals inhabit shape individuals’ decisions about their health.9 10 We identify potential barriers and facilitators to PrEP awareness and candidacy perceptions, providing much-needed evidence to support PrEP uptake and effective use in women most at risk of HIV.

Methods

Between June and August 2018, a purposive sample of 32 BME women was recruited for semi-structured, in-depth interviews. Eligibility criteria included (1) identifying as a BME woman (including trans/transgender women), (2) having been sexually active in the last 6 months, and (3) being older than 18. Interviews were conducted in London and Glasgow to provide geographical diversity and explore the influence of PrEP provision through a trial and through routine NHS care. Women of all HIV statuses and ages were included to ensure diversity of experience.

In London, participants were recruited by distributing flyers at relevant community events, emailing service users of and volunteers with partner HIV advocacy organisations, circulating information on social media through community influencers and activists, and encouraging study participants to refer friends. In Glasgow, a community organisation with programmes supporting HIV prevention and care among BME communities referred clients to the study. All participants received £25 in cash.

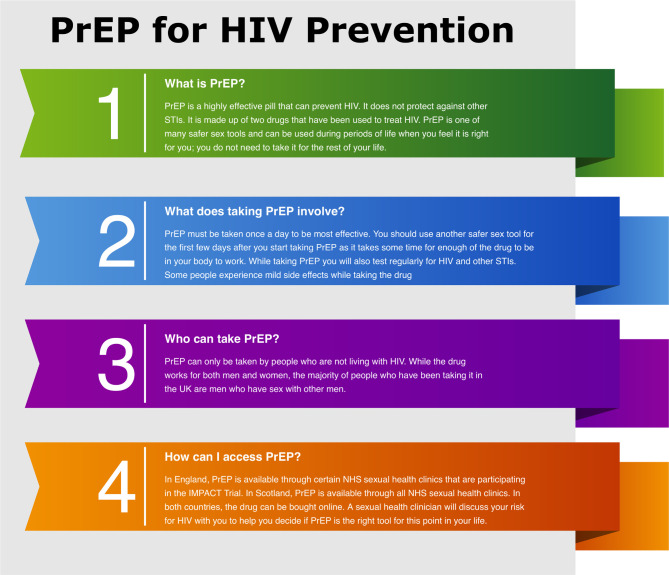

Each interview was conducted at a semi-private location chosen by the participant. Interviews explored (1) personal safer sex definitions, (2) personal and community HIV risk perceptions, (3) engagement with HIV prevention methods, (4) attitudes towards PrEP, and (5) opinions of PrEP advertising and access (online supplementary appendix 1 lists the interview guides). Participants were offered materials from two UK PrEP literacy projects during the interview.11 12 The interviewer and participant discussed key facts about PrEP (figure 1) and participants were invited to ask additional questions.

Figure 1.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) facts shared during interviews.

sextrans-2020-054457supp001.pdf (86KB, pdf)

Interviews were recorded and transcribed by the lead author for data familiarisation. Transcripts were iteratively coded using ATLAS.ti.13 Following initial coding, inductive thematic analysis was used to organise and categorise the data using the constant comparison approach.14 Study team members read transcripts and discussed emerging themes at multiple points to ensure that the final theme list reflected the data’s breadth and depth.

Results

Twenty-two interviews were conducted in London (mean age: 37.15, range: 21–60) and 10 in Glasgow (mean age: 43.4, range: 19–63). All participants were born outside the UK, but most had lived in the UK for over a decade. Nearly half were born in East Africa; others had Central, West and North African backgrounds. Only two women (both from London) identified as Black Caribbean. The majority of participants identified as heterosexual and all were assigned female sex at birth. Table 1 shows sample demographic details.

Table 1.

Population characteristics

| Age | Self-identified HIV status | Number of participants | |

| London interviews (n=22) | Between 18 and 30, inclusive | HIV positive | 1 |

| HIV negative/unknown | 9 | ||

| Older than 30 | HIV positive | 7 | |

| HIV negative/unknown | 5 | ||

| Glasgow interviews (n=10) | Between 18 and 30, inclusive | HIV positive | 0 |

| HIV negative/unknown | 1 | ||

| Older than 30 | HIV positive | 5 | |

| HIV negative/unknown | 4 |

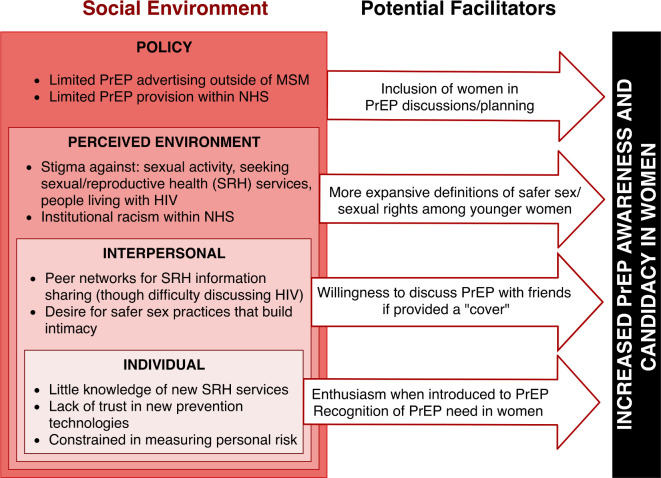

Consistent with the SEM, respondents discussed multiple levels of influence that shaped how they understood and practised safer sex. Four levels of influence emerged: (1) participants’ specific knowledge of and engagement with SRH services (individual), (2) interactions with peers and sexual partners (interpersonal), (3) interactions with and assumptions about community members (perceived environment), and (4) sexual health policy and PrEP activism (policy). Figure 2 shows emerging themes organised by these levels and the potential effect of these themes on targeted PrEP dissemination to women. Online supplementary appendix 2 lists illustrative extracts.

Figure 2.

Barriers and facilitators to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PreP) candidacy perceptions.

sextrans-2020-054457supp002.pdf (119KB, pdf)

Individual influences

Nearly all respondents displayed good HIV knowledge; most could identify transmission modes and established prevention tools such as condoms. Many attributed this knowledge to personal experience (eg, living in an HIV-endemic country) (Q1, online supplementary appendix 2). Few respondents knew about biomedical prevention options like PrEP and the concept of ‘Undetectable=Untransmittable’ (U=U) (ie, virally suppressed individuals living with HIV cannot transmit it.)15 Once PrEP was explained, participants described it as a necessary intervention and one that could be useful for ‘women they knew’ (Q2).

While respondents reported enthusiasm for PrEP, they also discussed safer sex beliefs that might prevent them from using or recommending PrEP. Noting that most participants learnt about PrEP through the interview, many reported uncertainty in PrEP’s effectiveness. Women expressed concerns that PrEP’s efficacy could not be ‘guaranteed’ (Q3). Similar fears emerged when discussing U=U. Women living with HIV feared that, even when undetectable, they could transmit the virus (Q4). By itself, information about PrEP (and U=U) appeared to be insufficient to challenge existing HIV risk understandings.

Many respondents struggled to articulate how they assessed risk, broadly seeing ‘everyone’ as at risk but unable to judge when that risk was severe enough to warrant preventative measures. While useful for others, participants had difficulty viewing PrEP as personally useful. Participants living with HIV reinforced this point by explaining how they struggled to identify being ‘at risk’ before diagnosis (Q5).

Interpersonal influences

Some respondents preferred accessing sexual health information from peer networks over NHS professionals. Peer discussions provided advice on choosing contraceptive services, seeking care for STI symptoms and general sexual wellness (Q7–8, online supplementary appendix 2). Participants in London were more likely to cite peer networks as a major influence in sexual health decision-making. A few used these networks to avoid the long waiting times for appointments with their general practitioner (GP). Participants also complained these appointments weretoo brief to discuss sexual health questions (Q9). Participants in Glasgow described limited comparable peer networks: some respondents thought living in majority-white areas made constructing community more difficult, potentially complicating finding trusted peers (Q10).

Despite openness with topics such as contraception services, many women were hesitant to discuss HIV prevention within these networks. While sharing general PrEP facts was acceptable, participants thought detailed PrEP discussions risked offense, especially since they could be seen as accusing others’ partners of infidelity (Q11). Some women stressed the need for a ‘cover’ when discussing HIV; if they could pre-empt questions about why they were discussing PrEP by offering ‘legitimate’ explanations (ie, participating in a research project), they were more comfortable broaching the topic (Q12).

Women did not know how they would discuss PrEP with sexual partners. Many prioritised safer sex practices that built trust and intimacy, not just those that prevented STIs. For example, women explained how they saw joint HIV testing as a way to strengthen a relationship—they could assess how much their partner cared about the health of both people in the relationship and ensure fidelity (Q13). Women reported they did not want to use PrEP to circumvent conversations about risk with their partner. They wanted a tool that would help them approach such conversations and could not see how PrEP could help achieve this.

Perceived environment influences

Almost all women interviewed believed community stigma would complicate PrEP access. Stigma towards those living with HIV was perceived as prevalent by women of all HIV statuses. This made participants wary of discussing HIV for fear their peers would presume they were living with HIV. This was especially a concern for women who were living with HIV and who did not want to risk disclosure (Q14, online supplementary appendix 2). Some women were also wary of accessing SRH services, as they feared being seen at a clinic would cause community members to view them negatively (Q15).

In addition to community HIV stigma, institutional stigma dissuaded some women from seeking SRH services. Despite overall satisfaction with the NHS, some women reported experiencing institutional racism either when seeking SRH care or related to their HIV diagnoses. Glasgow participants recounted experiencing racism within the NHS and believed they had received delayed or substandard care because of their ethnicity (Q16). London participants had fewer complaints, though some felt pushed into using contraception by healthcare professionals in a way they believed had racial undertones (Q17).

The context and time during which women grew up and learnt about their sexuality framed their safer sex definitions. Women over 30 often defined safer sex by the tools they had available to them (ie, condoms, testing). Younger respondents (under 30) were more likely to define safer sex in ways that embraced who they were holistically and what they needed from a relationship, incorporating concepts of sexual autonomy, empowerment, and consent (Q18).

Policy influences

Though most respondents were unaware of current PrEP advocacy campaigns or clinical guidelines, many still raised concerns that address current provision policies. Some respondents who did not previously know about PrEP valued receiving materials that displayed women and/or wanted PrEP information to come from other women. Respondents discussed how seeing someone who looked like them helped them feel like PrEP could be something with which they might engage (Q19). In contrast, the minority of participants who knew about early PrEP advocacy efforts and saw them largely directed at white, self-identified gay men complained that this had prevented them from seeing themselves as a PrEP candidate (Q20).

Some women described discomfort with PrEP provision through SRH services. Participants expressed concerns that if community members saw them going to a sexual health clinic, these community members might view them negatively. Many women wished to access PrEP through their GP, a provider with whom they had been able to build trust and who could counsel them about sexual health in a less stigmatised environment (Q21).

Discussion

In the first study to focus on PrEP attitudes in UK Black African/Black Caribbean women exclusively, our findings suggest that increasing PrEP uptake in this multifaceted group, many of whom do not view themselves as PrEP candidates, will be challenging. Barriers to PrEP use included personal safer sex definitions that did not match definitions used in clinical guidelines, community stigma around HIV that extended to stigmatising HIV risk, fear of being seen accessing SRH services, and perceived institutional racism. In contrast, PrEP normalisation via GP provision and some forms of peer networking were seen as potential facilitators to PrEP use. Women’s safer sex definitions varied, especially between women over 30 (who defined safer sex as the tools they used) and their younger counterparts (who defined safer sex as part of their holistic health). These findings help explain women’s low PrEP uptake in current UK programmes, where PrEP has been provided solely through SRH services and without large-scale, diverse, woman-specific messaging.

In accord with similar studies of PrEP attitudes in women and Black African/Black Caribbean heterosexual populations, respondents were enthusiastic about the idea of PrEP but struggled to see how they would incorporate it within their own safer sex routines. This was because they did not see themselves as at risk of HIV and did not understand how PrEP could address their specific safer sex needs.16–18 As in previous studies, a lack of patient/community knowledge about PrEP hindered uptake.19 Consistent with other research on HIV/HIV prevention in this population, these findings show the importance of health campaigns that work to address influences across multiple layers of the social environment.20 21

We demonstrate that simply knowing about PrEP does not mean women will trust or use it. Some participants had safer sex priorities that went beyond avoiding STIs to priorities such as building trust and intimacy in their relationships—priorities which PrEP did not address.

For Black African/Black Caribbean women to benefit from PrEP, campaigns will need to engage multiple levels of influence that shape their safer sex perceptions. Helping women understand how PrEP fits into their personal safer sex narratives, addressing community stigma around HIV and SRH, and creating institutional environments more welcoming of Black African/Black Caribbean women will be critical.

Our findings underscore the need for dynamic processes to develop health literacy around prevention22 23 which acknowledges the role of social identity.24 Increasing women’s PrEP knowledge will be an important first step, but additional work to make sure women understand how PrEP may fit into their social environments and their own safer sex narratives will be critical. Open discussions with clinical providers and women-focused advertising may help.

PrEP has limited utility as an HIV prevention tool for people who are unaware they are at risk of HIV, such as women whose partners have sex with other people who are at high risk of HIV. Sensitive, culturally appropriate approaches will be needed and, in these cases, prevention interventions may be better focused on their male partners.

Social networking and information sharing around SRH emerged as a key support avenue for participants in this study. These networks have, in the past, provided an alternative advice source to official medical structures that operate on safer sex definitions unrepresentative of women5 25 and may be actively hostile to racial minorities. While these networks proved important to many in the study and facilitated dialogue around multiple SRH topics, they may not help increase candidacy notions around PrEP in their current form. These networks are influenced by community stigmas around HIV and may foreclose discussions around anything more than acknowledging PrEP exists. While providers should recognise and use avenues, such as peer networks, through which women receive sexual health information, this needs to be done while recognising and responding to the HIV stigma and sexual norms which permeate them.

For women to access PrEP, services likely need to be provided outside of sexual health settings. However, unless community stigma is also addressed, appeal will remain limited. Provision through trusted healthcare providers such as GPs may help reach women who would benefit from PrEP but are apprehensive about seeking care in SRH services. Such approaches may also help ‘normalise’ PrEP uptake among Black African/Black Caribbean women by providing it in areas not characterised by existing stigma. However, the challenges to providing PrEP services through general practice should not be underestimated.

This is the first qualitative study to explore PrEP attitudes among UK Black African/Black Caribbean women exclusively in the context of PrEP provision, and one of very few worldwide. Our research makes important contributions towards understanding the issues these women may face when situating PrEP within their safer sex narratives and provides pointers to areas of consideration for developing novel PrEP interventions. Our sample included women from communities at higher risk of HIV rather than women who were at elevated risk of HIV per se. Most women in the study had not heard of PrEP before the interview or had only minimal knowledge of it. Expressed intentions to use PrEP should be interpreted with caution. Our study sample was recruited almost entirely through organisations that provide supportive services for HIV and sexual healthcare. This may have made the overall sample more aware and accepting of those living with HIV than the general population.

Conclusions

Multiple influences within UK Black African/Black Caribbean women’s environments shape their safer sex understandings and practices, including their own trust in new biomedical HIV prevention techniques, their interactions with friends and partners, existing stigma within their communities, current PrEP advertising, and existing PrEP services. Examining how each level of influence interacts with the others elucidates why many Black African/Black Caribbean women in the UK have limited PrEP candidacy notions, both for themselves and for other women in their community. Attending to divergent safer sex definitions, working to ameliorate community stigma (especially in social networks through which women currently receive sexual health information) and providing PrEP in alternative acceptable settings may facilitate PrEP uptake.

An urgent need exists for rigorously developed, co-created interventions which facilitate discussion of PrEP in the broader context of women’s perceptions of safer sex and tackle HIV and PrEP stigma. Interventions will need to be tailored to women at different life course stages and involve trusted community healthcare settings. For some women, PrEP may not be the most appropriate prevention tool and, in some cases, interventions which target their male partners may be more relevant.

Key messages.

Multi-layered influences including interpersonal networking around sexual health and community stigma shape Black African/Black Caribbean women’s perceptions of safer sex and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) candidacy.

PrEP campaigns must engage with community norms around safer sex to increase uptake in Black African/Black Caribbean women.

Women-focused PrEP marketing is needed with tailoring of messages to different points in the life course.

Black African/Black Caribbean women may be unlikely to access PrEP through sexual health services; alternative community-based delivery models should be considered.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Embrace UK, Positive East, and Waverley Care for their assistance recruiting study participants. We are particularly indebted to Yasmin Dunkley (Positive East), Claire Kofman (Waverley Care) and Mariegold Akomode (Waverley Care) for their help. Activists from PrEPster, iwantPrEPnow and the Sophia Forum also provided invaluable advice throughout the project. Our biggest thanks go to the women who gave their voices to this study.

Footnotes

Handling editor: Tristan J Barber

Twitter: @sarahnakasone, @ingridkyoung, @PaulFlowers1

Contributors: SEN, IY, CSE, PF, JR and MS designed the research study. SEN, MS, IY and CSE conceived the paper and designed the analysis plan. SEN led the analysis with contributions from IY, CSE, JC and MS. SEN led the drafting of the manuscript. All authors read, critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was received from the University of Chicago’s Biological Sciences Division Institutional Review Board (Ref IRB18-0622).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement: Data are available on reasonable request. De-identified manuscripts are available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Nash S, Desai S, Croxford S, et al. . Progress towards ending the HIV epidemic in the United Kingdom: 2018 report. London: Public Health England, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brown A, Czachorowski M, Davidson J, et al. . HIV testing in England: 2017 report. London: Public Health England, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Stokes P. 2011 census: key statistics and quick statistics for local authorities in the United Kingdom—Part 1. Office for National Statistics, 2013. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/datasets/2011censuskeystatisticsandquickstatisticsforlocalauthoritiesintheunitedkingdompart1 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Young I, Flowers P, McDaid LM. Barriers to uptake and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PreP) among communities most affected by HIV in the UK: findings from a qualitative study in Scotland. BMJ Open 2014;4:1 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-005717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Anaebere AK, Maliski S, Nyamathi A, et al. . “Getting to know”: exploring how urban African American women conceptualize safer and risky sexual behaviors. Sex Cult 2013;17:113–31. 10.1007/s12119-012-9142-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, et al. . Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS 2016;30:1973–83. 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sullivan A. PrEP impact trial: a pragmatic health technology assessment of PrEP and implementation, 2019. Available: https://www.prepimpacttrial.org.uk/protocol [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. National HIV PrEP Coordinating Group Implementation of HIV PreP in Scotland: first year report. Health Protection Scotland and Information Services Division, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Baral S, Logie CH, Grosso A, et al. . Modified social ecological model: a tool to guide the assessment of the risks and risk contexts of HIV epidemics. BMC Public Health 2013;13:482 10.1186/1471-2458-13-482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention The Social-Ecological Model: a framework for prevention, 2019. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/publichealthissue/social-ecologicalmodel.html [Accessed 5 May 2019].

- 11. Young I. Making the case for HIV literacy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Women and PrEP Sophia forum. Available: https://sophiaforum.net/index.php/women-and-prep/ [Accessed 20 Aug 2019].

- 13. ATLAS.ti 8 ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol 2006;3:77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15. The Lancet HIV U=U taking off in 2017. Lancet HIV 2017;4:e475 10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30183-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Auerbach JD, Kinsky S, Brown G, et al. . Knowledge, attitudes, and likelihood of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) use among US women at risk of acquiring HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2015;29:102–10. 10.1089/apc.2014.0142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bond KT, Gunn AJ. Perceived advantages and disadvantages of using pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among sexually active black women: an exploratory study. J Black Sex Relatsh 2016;3:1–24. 10.1353/bsr.2016.0019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ridgway J, Almirol E, Schmitt J, et al. . Exploring gender differences in PrEP interest among individuals testing HIV negative in an urban emergency department. AIDS Educ Prev 2018;30:382–92. 10.1521/aeap.2018.30.5.382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, et al. . Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med 2014;11:e1001613 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tariq S, Elford J, Tookey P, et al. . "It pains me because as a woman you have to breastfeed your baby": decision-making about infant feeding among African women living with HIV in the UK. Sex Transm Infect 2016;92:331–6. 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Doyal L. Challenges in researching life with HIV/AIDS: an intersectional analysis of black African migrants in London. Cult Health Sex 2009;11:173–88. 10.1080/13691050802560336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Green J, Lo Bianco J, Wyn J. Discourses in interaction: the intersection of literacy and health research internationally. LNS 2007;15:19–38. 10.5130/lns.v15i2.2205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Young I, Valiotis G. Strategies to support HIV literacy in the roll-out of pre-exposure prophylaxis in Scotland: findings from qualitative research with clinical and community practitioners. BMJ Open Forthcoming. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zarcadoolas C, Pleasant A, Greer DS. Understanding health literacy: an expanded model. Health Promot Int 2005;20:195–203. 10.1093/heapro/dah609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blair TR. Safe sex in the 1970s: community practitioners on the eve of AIDS. Am J Public Health 2017;107:872–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

sextrans-2020-054457supp001.pdf (86KB, pdf)

sextrans-2020-054457supp002.pdf (119KB, pdf)