Abstract

Background

The world's most catastrophic epidemic thunderstorm asthma event (ETSA) affected Melbourne in 2016. Little is known about the natural history of individuals affected by such extreme events.

Objective

In this single center prospective 3-year longitudinal study, symptomatology and behaviors of individuals affected by ETSA were assessed.

Methods

Standardized telephone questionnaire was used to evaluate frequency of asthma symptoms, inhaled corticosteroid preventer use, asthma action plan ownership, and healthcare utilization. Questionnaires were administered at 12, 24, and 36 months after 2016 ETSA. Subgroup analyses of the ‘current’, ‘past’, ‘possible,’ and ‘no asthma’ subgroups were also conducted.

Results

Two hundred and eight, 164, and 112 completed questionnaires were analyzed in 2017, 2018, and 2019, respectively. Seventy to eighty five percent of respondents reported ongoing asthma symptoms in any given year, of which 20%–28% experienced weekly symptoms. Nearly 50% of respondents were prescribed preventers, with approximately 45% adherent at least 5 days a week. Less than 40% had an asthma action plan and 15%–20% sought urgent medical attention for asthma over the follow-up period. Among 106 individuals with 3 consecutive years of completed questionnaires, those with no prior doctor diagnosis of asthma were significantly more likely to be asymptomatic on follow-up than those with a prior doctor diagnosis of asthma (p = 0.02). Subgroup analyses suggest that large proportions of respondents with ‘past’ and ‘no asthma’ continue to remain symptomatic throughout the 36-month period.

Conclusion

In individuals affected by ETSA, we found evidence of ongoing loss of asthma control in those with previously well controlled asthma, and the persistence of symptoms suggestive of asthma in those with no history or symptoms suggestive of prior asthma, even after 36 months from initial ETSA. Low rates of inhaler adherence and asthma action plan ownership may contribute to increased morbidity and mortality from future ETSA events. Further research is required to confirm these findings.

Keywords: Asthma, Environment, Epidemics, Natural history, Pathophysiology, Public health

INTRODUCTION

Epidemic thunderstorm asthma (ETSA) is defined as an observed increase in cases of acute bronchospasm following thunderstorms in the local vicinity [1]. First described in the United Kingdom in 1983 [2], ETSA events have now been reported across the world including in Australia, Europe, the Middle East, and the United States of America [3].

On 21st November 2016, the world's largest and most catastrophic ETSA event struck Melbourne, resulting in over 3,500 Emergency Department (ED) presentations, 35 intensive care unit admissions and 10 deaths [4]. The natural history of asthma symptoms in individuals affected by such catastrophic events remains unclear due to the paucity of data available. One study suggested a pivotal change in asthma trajectory with both loss of asthma control and persistence of de novo asthma in certain individuals 12 months after an ETSA event [5]. Whether these phenomena persist over time remains uncertain.

We therefore conducted a single center prospective longitudinal study assessing the symptomatology, behaviors, and healthcare utilization of individuals 12, 24, and 36 months after the 2016 thunderstorm asthma event.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In December 2016, individuals who presented to the ED at our health service with a clinical diagnosis of ETSA were contacted and administered a standardized telephone questionnaire using methodology previously described and summarized here [4]. Individuals who indicated their willingness to participate in future research were contacted again in December 2017. A structured telephone questionnaire (Supplementary material 1) was utilized. Specific questions regarding frequency of asthma symptoms, use of inhaled preventer, asthma action plan ownership, and need for urgent healthcare utilization in the preceding 12 months were included. At the end of the questionnaire, individuals were given the option to participate in ongoing research. Those who agreed were contacted again in December 2018 and December 2019 and administered the same telephone questionnaire. Individuals whom had declined participation were not contacted subsequently, whereas those who were uncontactable were still eligible for inclusion and contacted the following year. Questionnaires with reply-paid envelops were mailed to individuals who were uncontactable by phone. Questionnaires were directed at the parents for individuals who were less than 18 years old. Patients who declined to consent, were uncontactable, or did not respond to the mailed questionnaire were excluded from the analysis.

Asthma symptoms (wheezing, coughing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness) were categorized into ‘persistent,’ ‘frequent episodic,’ ‘infrequent episodic,’ or ‘asymptomatic’ depending on their average frequency over the last 12 months. ‘Persistent’ was defined as having symptoms ≥ once a week; ‘frequent episodic’ as having symptoms > once a month but < once a week; ‘infrequent episodic’ as having symptoms ≤ once a month, with ‘asymptomatic’ reporting no symptoms.

The asthma status of an individual was determined from questionnaire responses obtained in the first survey round in December 2016 [4]. ‘Prior asthma’ was defined as any previous doctor-diagnosis of asthma, and within this category, ‘current asthma’ was defined as those with symptoms in the 12 months leading up to November 2016, and ‘past asthma’ as those without. Individuals who did not have a prior doctor diagnosis of asthma were further classified into those with ‘possible undiagnosed asthma’ or ‘no asthma’ based on whether they reported having experiences symptoms suggestive of asthma (wheeze, chest tightness, or shortness of breath) that either disrupted their sleep, or occurred with colds, hay-fever or exercise.

Data were summarized using mean ± standard deviation, or number (%) as appropriate, and compared using χ2 test or Student t test where applicable. The distribution of time-to-event end point for individuals remaining symptomatic was estimated by the Kaplan-Meier method, with log rank test utilized for comparison between groups. A p value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Eastern Health Office of Research and Ethics (reference number: LR76-2017).

RESULTS

Response rate and demographics

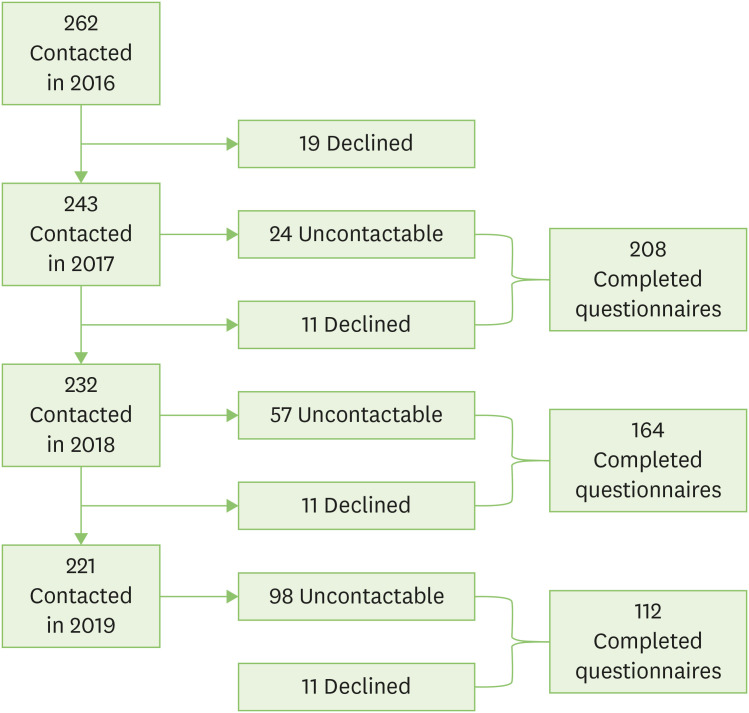

Two hundred and forty-three of the 262 individuals whom responded to the 2016 questionnaire agreed to future research and were contacted again in 2017. Of these, 11 declined to participate and 24 did not respond to either phone attempts or mail-out questionnaire, leaving 208 individuals (86%) with completed follow-up questionnaires. In 2018, 164 of the 232 individuals approached completed follow-up questionnaires (71%). Reasons for nonresponse include: 11 who declined and 57 uncontactable despite multiple attempts. Of the 221 individuals contacted in 2019, 112 completed follow-up questionnaires (51%), 11 declined participation and 98 could not be reached (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Consort diagram.

The mean age of respondents was 32 ± 19 years and 60% were males. The baseline characteristics of respondents were similar across the years, and were not statistically different from the 2016 cohort (Table 1).

Table 1. Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | 2016 Cohort (n = 262) | 2017 Respondents (n = 208) | 2018 Respondents (n = 164) | 2019 Respondents (n = 112) | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 32.2 ± 19.3 | 32.1 ± 18.4 | 32.2 ± 18.4 | 33.1 ± 19.4 | NS | |

| Male sex | 152 (58) | 126 (61) | 96 (59) | 67 (60) | NS | |

| Ever been diagnosed with asthma | ||||||

| Current asthma | 75 (68) | 63 (71) | 47 (71) | 30 (68) | NS | |

| Past asthma | 36 (32) | 26 (29) | 19 (29) | 14 (32) | NS | |

| Total | 111 (42) | 89 (43) | 66 (40) | 44 (39) | NS | |

| Never been diagnosed with asthma | ||||||

| Probable asthma | 80 (53) | 69 (58) | 51 (52) | 37 (54) | NS | |

| No asthma | 71 (47) | 50 (42) | 47 (48) | 31 (46) | NS | |

| Total | 151 (58) | 119 (57) | 98 (60) | 68 (61) | NS | |

Values are presented as mean ± standard deviation or number (%).

NS, not significant.

Symptomatology

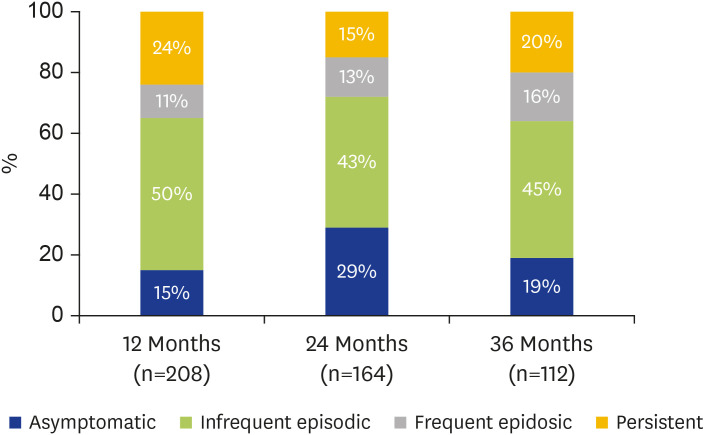

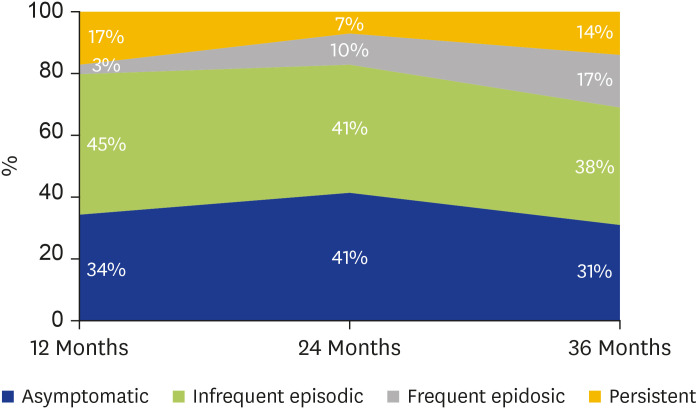

Frequency of symptoms in respondents at 12, 24, and 36 months following the ETSA event are presented in Fig. 2. At 12-month follow-up, 85% (n=176) of respondents reported at least one episode of asthma symptoms following the ETSA event. Of these, 60% (n=104) reported ‘infrequent episodic’ symptoms and 13% (n=23) ‘frequent episodic’ symptoms. Importantly, 28% (n=49) described ‘persistent’ symptoms. These were a subset of a collaborative multicenter cohort described in our previous publication [5].

Fig. 2. Frequency of symptoms in respondents at 12, 24, and 36 months after epidemic thunderstorm asthma event.

At 24- and 36-month follow-up, 70% and 80% of respondents respectively continued to report at least one episode of asthma symptoms in the preceding 12-month period. While the majority described ‘infrequent episodic’ symptoms, a concerning 20%–25% reported weekly symptoms.

Preventer prescription and adherence, asthma action plan ownership, and healthcare utilization

In general, inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) preventer prescription rate was approximately 50%. Of those prescribed a preventer, between 40%–50% of them reported adherence (usage ≥ 5 days a week) in any given year.

Less than 40% of respondents had an asthma action plan at any time point. Healthcare utilization, which was defined as any urgent visit to a general practitioner's clinic, ED or hospital admission for asthma, was stable across the 36-month period at 15%–20%.

Subgroup analysis

Amongst the 262 individuals initially contacted in 2016, 106 (40%) had 3 consecutive years of completed questionnaire data. The mean age of this group was 32 ± 19 years and 60% were males. This group was similar to the nonrespondents and those missing at least 1 year of follow-up data.

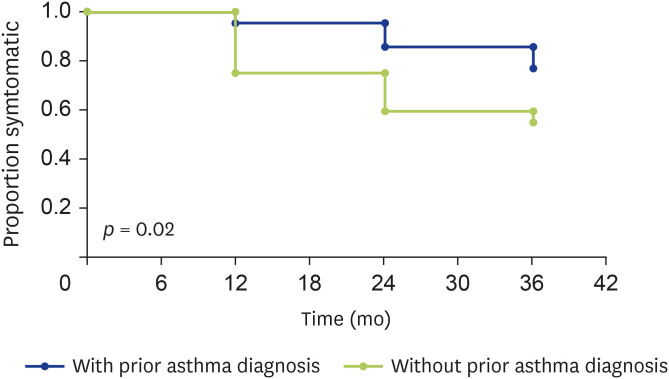

Within this group, 40% (n=42) had pre-existing doctor diagnosed asthma, and 60% (n = 64) did not. After the 2016 ETSA event, individuals without pre-existing doctor diagnosis of asthma were significantly more likely to report being asymptomatic at any time point during the study compared to those with a prior doctor-diagnosis of asthma (p = 0.02) (Fig. 3). While a proportion of respondents in either group became symptomatic again at a later time point, majority of them report symptoms less than once a month.

Fig. 3. Symptomatic analysis of those with and without prior asthma diagnosis.

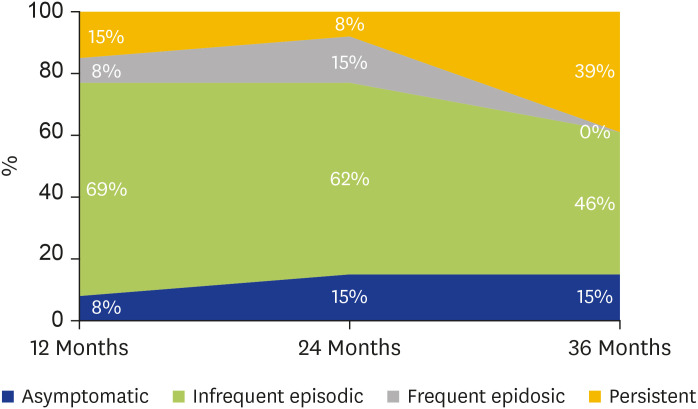

Of the 40% (n = 42) who had pre-existing ‘doctor diagnosed asthma’, 69% (n = 29) had ‘current asthma’ and 31% (n = 13) ‘past asthma.’ Notably, 92% (n = 12) of those who had reported ‘past asthma,’ that is no asthma symptoms in the 12 months preceding the 2016 ETSA event, reported asthma symptoms on 12-month follow-up. Although the majority of this cohort experienced ‘infrequent episodic’ symptoms, 17% (n = 2) had ‘persistent symptoms.’ Over the subsequent 24 months, 31% (n = 4) of respondents with ‘past asthma’ described an overall reduction of, or no change in their frequency of asthma symptoms. In contrast, 69% (n = 9) reported increasing frequency, or fluctuation in their asthma symptoms. At 36 months follow-up, 85% (n = 11) of respondents remained symptomatic, with 45% (n = 5) of them now reporting ‘persistent symptoms’ (Fig. 4). Among those with ‘current asthma,’ >93% reported ongoing asthma symptoms in any given year.

Fig. 4. Change in symptom frequency over time in those with ‘past asthma’ (n = 13).

Out of the remaining 60% (n = 64) with no doctor-diagnosis of asthma prior to November 2016, 55% (n = 35) had ‘possible undiagnosed asthma’ and 45% (n = 29) ‘no asthma,’ based on whether there was a history of ever having had wheeze, chest tightness or shortness of breath with colds, hay-fever, or exercise, or been woken up from sleep by them. Interestingly, 66% (n = 19) of those with ‘no asthma’ reported asthma symptoms at 12-month follow-up – 68% (n = 13) ‘infrequent episodic,’ 5% (n = 1) ‘frequent episodic,’ and 27% (n = 5) ‘persistent.’ Over the next 24 months, only 32% (n = 6) reported an overall reduction in their frequency of asthma symptoms. The remaining 68% (n = 13) described increasing, fluctuating or no change in the frequency of asthma symptoms. Of the 34% (n = 10) with ‘no asthma’ who were asymptomatic, 60% (n = 6) continued to remain symptom free over the following 24-month period, with the remaining 40% (n = 4) describing increased asthma symptoms over the same duration. At 36-month follow-up, 69% of respondents with ‘no asthma’ remained symptomatic with 14% experiencing persistent symptoms (Fig. 5). In contrast, approximately 80% of those with ‘probable asthma’ reported asthma symptoms in any given year.

Fig. 5. Change in symptom frequency over time in those with ‘no asthma’ (n = 29).

DISCUSSION

This is the first longitudinal study assessing symptomatology and behaviors of individuals affected by ETSA. Our study shows that the overwhelming majority of individuals continue to experience asthma symptoms up to 36 months after the initial 2016 ETSA event. Worryingly, almost a quarter of them reported symptoms at least once a week. Low rates of inhaled preventer use and asthma action plan ownership were also observed throughout the study. Notably, our data suggests ongoing loss of asthma control in those with previously well controlled asthma, and the persistence of symptoms suggestive of de novo asthma in those with no history or symptoms suggestive of prior asthma, even after 36 months from the initial ETSA event. These findings have wide ranging implications for clinical management, preventative health policy, and public health messaging.

The high burden of symptoms on follow-up suggest suboptimal control of asthma in this cohort. The low rates of ICS usage in those affected by the initial ETSA event has already been recognized as a risk factor in ambulance calls [6], ED presentations and admissions to respiratory wards [7]. This may be due to a number of factors: (1) most ETSA affected individuals had predominantly airway reactivity with no prior diagnosis of asthma or were not aware of asthma symptoms; (2) they had less severe or intermittent asthma for which regular ICS may not have been indicated, or (3) they were nonadherent to regular ICS use despite having persistent asthma. However, the low rates of ICS prescription and high rates of nonadherence even in those reporting ‘persistent symptoms’ post ETSA is of great concern. ICS remains the mainstay of asthma treatment, but are only effective if taken consistently. Poor adherence is a known issue in asthma management, with our findings consistent with the 30%–70% published rates [8,9]. Poor control of asthma increases individual susceptibility to acute triggers including future ETSA events [10], with the potential to increase morbidity and mortality [11]. Ongoing education campaigns with the emphasis on good asthma control and adherence to preventer medications is crucial to improve the health and wellbeing of this cohort.

Subgroup analysis of the respondents with 3 consecutive years of questionnaire data showed that 92% of respondents with a known doctor diagnosis of asthma who were asymptomatic in the 12 months leading up to 2016 ETSA reported asthma symptoms on 12-month follow-up. Additionally, 66% of respondents who neither had a prior doctor diagnosis of asthma nor any prior symptoms suggestive of undiagnosed asthma described asthma symptoms over the same period. While these findings are similar to those reported in a previous study [5], our data also suggest that majority of individuals in these subgroups continue to remain symptomatic over the 36-month follow-up period, with less than a third of them reporting a reduction in frequency of their asthma symptoms.

Current literature suggests that ETSA results from a complex interaction of environmental and individual susceptibility factors [4]. During the thunderstorm event, larger aeroallergens are broken down into smaller respirable particles (usually <5 μm in size) that are concentrated at ground level by the thunderstorm outflow tract. Upon inhalation into the lower respiratory tract, these allergens are able to induce asthma by provoking acute bronchospasm in sensitized individuals (allergen-induced early asthmatic response) [12,13]. Following this acute process, many individuals subsequently develop a late asthmatic response that is characterized by allergen-induced increase in airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation, a phenomenon that can persist for several days [12]. Furthermore, it is known that the likelihood of developing a late asthmatic response is increased with higher doses of inhaled allergen [14]. Subsequently, ETSA has been postulated to constitute a massive small airway allergen challenge inducing persistent airway inflammation with nonspecific bronchial hyperresponsiveness, with resultant loss of asthma control or development of de novo asthma in susceptible individuals [5]. Observations from this study provide further support for this theory with >85% of individuals with previously well controlled asthma, and >60% with no prior diagnosis or symptoms suggestive of undiagnosed asthma, reporting asthma symptoms at 12, 24, and 36 months after the initial ETSA event.

Interpretation of the results of this study is limited by the small sample size, restriction to a single center, and lack of a comparative control group – individuals with a similar demographic profile and asthma status whom were unaffected by the 2016 ETSA event. The recruitment of such a control group who remained asymptomatic has been a challenge that is compounded by the unpredictable nature of ETSA events. Nevertheless, this study is unique as it examines the largest cohort and longest follow-up of ETSA individuals, with the findings of ongoing destabilization of asthma in those with ‘past asthma’ and ‘no asthma’ an interesting observation that requires confirmation in future studies.

A large number of potential respondents were also loss to follow-up, with the majority of them being uncontactable rather than declining to participate. While it is possible that the more symptomatic individuals are more likely to respond to follow-up contact, the baseline characteristics of the respondents were not dissimilar to the nonrespondents.

Additionally, there are inherent biases associated with the use of questionnaire surveys including recall bias. It is plausible that individuals affected by the 2016 ETSA have an increased sense of awareness and better recall of asthma symptoms in the following years. However, the use of structurally identical questionnaires at 12, 24, and 36 months should minimize the effect of recall bias.

In conclusion, in this first and largest longitudinal study of individuals affected by ETSA, we provide new perspectives on the natural history of their airway disease, highlighting the ongoing difficulties in identification, diagnosis, and management of asthma. As thunderstorm asthma events are predicted to increase in frequency, the findings of ongoing loss of asthma control and persistence of de novo asthma underscore the importance of further research in this unique group of individuals to better understand the pathophysiology of such changes and ways to mitigate them.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Francis Thien, Alan C. Young.

- Data curation: Cheryl M.T. Lim, Golsa Adabi, Sonali Fernando, Naomi Cohen, Chuan T. Foo.

- Formal analysis: Chuan T. Foo.

- Funding acquisition: Francis Thien.

- Methodology: Francis Thien, Alan C. Young.

- Project administration: Francis Thien.

- Visualization: Francis Thien, Alan C. Young, Chuan T. Foo.

- Writing - original draft: Chuan T. Foo.

- Writing - review & editing: Francis Thien, Chuan T. Foo.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material 1 can be found via https://www.apallergy.org/src/sm/apallergy-10-e30-s001.pdf

References

- 1.D'Amato G, Vitale C, D'Amato M, Cecchi L, Liccardi G, Molino A, Vatrella A, Sanduzzi A, Maesano C, Annesi-Maesano I. Thunderstorm-related asthma: what happens and why. Clin Exp Allergy. 2016;46:390–396. doi: 10.1111/cea.12709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Packe GE, Ayres JG. Asthma outbreak during a thunderstorm. Lancet. 1985;2:199–204. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(85)91510-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harun NS, Lachapelle P, Douglass J. Thunderstorm-triggered asthma: what we know so far. J Asthma Allergy. 2019;12:101–108. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S175155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thien F, Beggs PJ, Csutoros D, Darvall J, Hew M, Davies JM, Bardin PG, Bannister T, Barnes S, Bellomo R, Byrne T, Casamento A, Conron M, Cross A, Crosswell A, Douglass JA, Durie M, Dyett J, Ebert E, Erbas B, French C, Gelbart B, Gillman A, Harun NS, Huete A, Irving L, Karalapillai D, Ku D, Lachapelle P, Langton D, Lee J, Looker C, MacIsaac C, McCaffrey J, McDonald CF, McGain F, Newbigin E, O'Hehir R, Pilcher D, Prasad S, Rangamuwa K, Ruane L, Sarode V, Silver JD, Southcott AM, Subramaniam A, Suphioglu C, Susanto NH, Sutherland MF, Taori G, Taylor P, Torre P, Vetro J, Wigmore G, Young AC, Guest C. The Melbourne epidemic thunderstorm asthma event 2016: an investigation of environmental triggers, effect on health services, and patient risk factors. Lancet Planet Health. 2018;2:e255–63. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(18)30120-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foo CT, Yee EL, Young A, Denton E, Hew M, O'Hehir RE, Radhakrishna N, Matthews S, Conron M, Harun NS, Lachapelle P, Douglass JA, Irving L, Lee J, Stevenson W, McDonald CF, Langton D, Banks C, Thien F. Continued loss of asthma control following epidemic thunderstorm asthma. Asia Pac Allergy. 2019;9:e35. doi: 10.5415/apallergy.2019.9.e35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrew E, Nehme Z, Bernard S, Abramson MJ, Newbigin E, Piper B, Dunlop J, Holman P, Smith K. Stormy weather: a retrospective analysis of demand for emergency medical services during epidemic thunderstorm asthma. BMJ. 2017;359:j5636. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hew M, Lee J, Susanto NH, Prasad S, Bardin PG, Barnes S, Ruane L, Southcott AM, Gillman A, Young A, Rangamuwa K, O'Hehir RE, McDonald C, Sutherland M, Conron M, Matthews S, Harun NS, Lachapelle P, Douglass JA, Irving L, Langton D, Mann J, Erbas B, Thien F. The 2016 Melbourne thunderstorm asthma epidemic: Risk factors for severe attacks requiring hospital admission. Allergy. 2019;74:122–130. doi: 10.1111/all.13609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dima AL, Hernandez G, Cunillera O, Ferrer M, de Bruin M ASTRO-LAB group. Asthma inhaler adherence determinants in adults: systematic review of observational data. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:994–1018. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00172114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mes MA, Katzer CB, Chan AHY, Wileman V, Taylor SJC, Horne R. Pharmacists and medication adherence in asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2018;52:1800485. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00485-2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Girgis ST, Marks GB, Downs SH, Kolbe A, Car GN, Paton R. Thunderstorm-associated asthma in an inland town in south-eastern Australia. Who is at risk? Eur Respir J. 2000;16:3–8. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.2000.16a02.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Amato G, Vitale C, Molino A, Stanziola A, Sanduzzi A, Vatrella A, Mormile M, Lanza M, Calabrese G, Antonicelli L, D'Amato M. Asthma-related deaths. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2016;11:37. doi: 10.1186/s40248-016-0073-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cockcroft DW, Davis BE, Blais CM. Thunderstorm asthma: An allergen-induced early asthmatic response. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120:120–123. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.D'Amato G, Annesi-Maesano I, Vaghi A, Cecchi L, D'Amato M. How do storms affect asthma? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2018;18:24. doi: 10.1007/s11882-018-0775-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lai CK, Twentyman OP, Holgate ST. The effect of an increase in inhaled allergen dose after rimiterol hydrobromide on the occurrence and magnitude of the late asthmatic response and the associated change in nonspecific bronchial responsiveness. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1989;140:917–923. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/140.4.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material 1 can be found via https://www.apallergy.org/src/sm/apallergy-10-e30-s001.pdf