INTRODUCTION

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) individuals (including lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer) experience substantial cancer-related health disparities compared with heterosexual individuals (who partner exclusively with opposite-gender people) and cisgender individuals (whose gender identities are the same as their sex assigned at birth). For example, gay men and bisexual women have higher cancer prevalence than heterosexuals.1,2 Gender identity data were not collected in these epidemiologic studies, so less is known about cancer rates in transgender populations; limited data suggest the incidence of specific types of cancers is higher, although overall incidence may be similar.3-5 SGM patients report negative experiences with oncologic care, including stigmatization, barriers to timely diagnoses, mistaken assumptions, disrespect of gender identities, and lack of inclusion of partners.6 After cancer treatment, SGM patients with cancer continue to experience disparities, including increased risk factors for cancer recurrence, more tobacco use, poorer quality of life, more anxiety and depression, and more fear of cancer recurrence.7-14

A minority (20%-40%) of oncology clinicians (physicians, nurses, and advanced practitioners) feel knowledgeable to address SGM-specific health disparities, but a majority (70%-80%) want education regarding the unique health needs of SGM patients with cancer.15,16 To improve clinicians’ knowledge, institutions have begun providing SGM-focused training for oncology clinicians.17,18 The goal is to reduce barriers SGM people face in accessing high-quality cancer care and decrease disparities in cancer outcomes. However, few training programs have collected data regarding whether training is effective. To optimize the delivery of cancer care and reduce cancer disparities among SGM patients, we must decide which measures will tell us whether clinician training programs work. The aims of this commentary are to outline frameworks to guide SGM-focused cultural humility training in oncology, describe existing measures of cultural humility training, and discuss future directions.

FRAMEWORKS FOR SGM-FOCUSED TRAINING IN ONCOLOGY

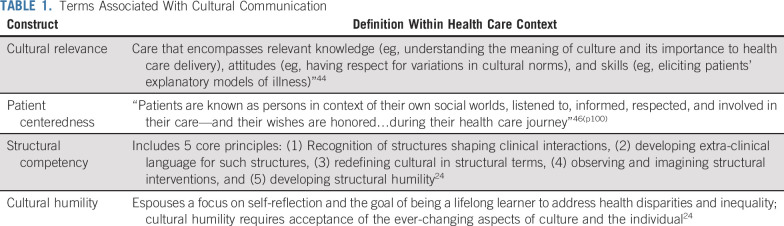

Training programs designed to enhance clinicians’ ability to work with minority and other underserved patients often draw on one of several interrelated frameworks.18 Historically, training programs have referenced the framework of cultural competency. With regard to SGM patients, cultural competency encompasses a requisite understanding of cultural and social influences that affect the ability of healthcare professionals to provide appropriate care for patients with diverse sexual orientations and gender identities.18-20 This framework has been criticized for the assumption that a person can ever be competent in the diverse experiences of another culture. Cultural humility incorporates a lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and critique, to redressing the power imbalances in the physician-patient dynamic, and to developing mutually beneficial and nonpaternalistic partnerships with communities on behalf of individuals and defined populations.21(p123) Cultural humility training emphasizes understanding the influence of systemic oppression on the health of people with multiple, intersecting stigmatized identities.22-24 Given that SGM individuals come from every cultural background and therefore have multiple intersecting identities, we advocate using the framework of cultural humility to guide SGM-focused training in oncology. Other distinct but conceptually related frameworks are defined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Terms Associated With Cultural Communication

SGM-focused cultural competency/humility training for health care clinicians has proved efficacious in improving clinician knowledge about SGM patients’ needs.24,25 To date, no studies have examined whether such training improves SGM patient outcomes. Parallel studies of racial and ethnic cultural competency/humility training demonstrate a moderate effect on satisfaction with care, trust in physicians, and access to health care.25-28 Other studies have shown little to no effect on patient outcomes.29,30 The quality of evidence arising from these studies is generally low because of methodologic issues, including lack of validated measurement strategies.25,31

MEASURES OF SGM CULTURAL HUMILITY IN ONCOLOGY

Presently, few validated measures exist to assess the outcomes of SGM cultural humility training, and none are specific to oncologic care. A systematic review of SGM-focused cultural competency/humility programs among medical and allied health students and clinicians identified 13 studies. Each evaluated training programs using trainee knowledge and/or attitude scales.32 Among studies assessing knowledge, all but one used nonvalidated measures designed by the researchers.32 A majority of studies assessing attitudes used existing scales and indices developed outside of the training context.33 An increase in trainees’ knowledge may not be associated with increased humility, a more patient-centered stance, or improvement in SGM patients’ outcomes. Similarly, measures of attitudinal change may elicit a high degree of social desirability and may not lead to behavior change.34,35 Limitations and advantages of these measures have been summarized elsewhere.36 New measures are needed that capture facets of cultural humility specific to care of SGM patients, correlate with clinical practice changes, and lead to improvements in SGM patient outcomes.37

Communication theory can serve as a guide for evaluation of SGM cultural humility training. Effective communication in medical interactions is “the ability to gather information to facilitate accurate diagnosis, counsel appropriately, give therapeutic instructions, and establish caring relationships with patients.”19(p177) Poor communication with racial/ethnic minority patients is associated with poorer pain control and postsurgical outcomes and fewer diagnostic tests.17,28 Cultural humility training could ameliorate health disparities in SGM patients by improving the quality of communication delivered by oncology clinicians. However, measuring change in communication quality is as complex as measuring change in attitudes. Multiple contextual factors influence the style and content of communication in oncology. Furthermore, communication theory posits that communication takes place within the receiver; communication is successful only when the receiver correctly interprets the sender’s message. If the patient is receiver and the clinician the sender, only the patient can truly evaluate the clinician’s cultural humility. However, no studies to date have evaluated SGM patient response to a clinician’s cultural humility.

Practice changes specific to the care of SGM patients with cancer should be measured as outcomes of cultural humility training. For example, unlike many racial and ethnic minority identities, the identities, relationships, and experiences of SGM patients may not be visible. After institutional cultural humility training, oncologists should be better prepared to ask patients about their sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) and use this information to improve shared decision making. In tandem, clinicians must learn to use language inclusive of SGM experiences (eg, partner rather than wife or people with breast cancer rather than women with breast cancer) and ask and respect patients’ names, pronouns, and surgical or quality-of-life preferences, which may differ from physicians’ expectations, as they may with any patient.12,14,17 Administrators should be motivated to revise patient intake forms and educational material to be inclusive of SGM people. Other aspects of the health care environment should also change. For example, gender-neutral bathrooms should be made available, and gendered spaces (eg, men’s prostate center) should be renamed.

To measure cultural humility and its influence on the health of SGM populations, we advocate incorporating all of the above into a multilevel evaluation strategy that emphasizes structural change. The Betancourt et al38 model for using cultural humility interventions to address health disparities in racial and ethnic minority patients provides a template. This framework advocates for implementing cultural humility interventions at the organizational, structural, and clinical levels in health care settings and measuring patient-reported variables, including satisfaction, adherence, and outcomes.38 Creating a safe environment for marginalized patients also leads to the development of a safe environment for staff. Improving the experiences for SGM patients and employees would likely be mutually reinforcing, and therefore, both should be evaluated. On an organizational level, evaluations of SGM cultural humility training in oncology should include (1) an increase in SGM personnel, (2) an increase in job satisfaction of SGM personnel, and (3) endorsement of SGM personnel for leadership positions. On a structural level, evaluations should include (1) the presence of nondiscrimination policies and patient bills of rights that include SOGI, (2) the collection of SOGI data in clinical records, and (3) support resources and materials tailored to SGM patients. On a clinical level, evaluations should assess SGM patient outcomes and SGM patient satisfaction for physicians who have completed cultural humility training versus those who have not. ASCO endorses many of these changes in its position statement on reducing cancer disparities in SGM patients.39 The Human Rights Campaign has formalized these organizational and structural metrics in its Healthcare Equality Index (HEI). Scores on this index could be used as an evaluation strategy after SGM cultural humility training. However, association between HEI score and provider attitudes and behaviors is unclear, and no studies have evaluated association of these organizational and structural metrics with patient outcomes.40

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR SGM CULTURAL HUMILITY TRAINING IN ONCOLOGY

Thus far, we have argued that cultural humility serve as a framework for SGM-focused training in oncology and for multilevel evaluations of such training with attention to structural change. Most importantly, we advocate for the creation of SGM oncology cultural humility training and patient-centered measurement tools in partnership with SGM patients who have had cancer, particularly people of color, those who are working class, and those with other intersecting marginalized identities.6,41-44 Partnerships between community stakeholders and clinicians have the potential to decrease hierarchic power dynamics between patients and physicians and improve relationships. The Betancourt et al38 model offers several patient-level measures that could be cocreated in collaboration with SGM stakeholders. For example, SGM patients with cancer have outlined domains that contributed to their satisfaction with care: entering clinical spaces that acknowledge their identities, being assured of safe and respectful treatment, and interacting with providers who engage in patient-centered communication. Patient-derived components of satisfaction should be measured after cultural humility training. Additional patient-level measures should include whether SGM oncology patients remain in care, which is particularly germane in situations where SGM patients might leave care because of mistreatment. Additional metrics of SGM cultural humility training in oncology should be derived in partnership with stakeholders. Setting goals of training and developing relevant measurement tools should be a continuous, context-dependent, and iterative process.

The question for future studies to answer is how can providers who have been trained to be more culturally humble with SGM patients, directly improve their patients’ health? An SGM patient who feels understood and accepted may be more likely to disclose important facts about their health and behaviors, allowing their clinician to make more timely diagnoses and/or more relevant treatment recommendations. Moreover, a patient who feels accepted by their clinician may be more likely to stay in care and experience less cancer-related distress. Future studies should evaluate the association between particular cultural humility trainings, practice and systemic changes, and SGM patient satisfaction, engagement, and outcomes based on assessments created in collaboration with community stakeholders. The results of such studies should be provided to stakeholders and researchers to be used in a process of continuous growth and quality improvement.

Training is unlikely to be sufficient in changing the climate of care for SGM people. We also recommend that health care policies reinforce individual and system changes. For example, we strongly recommend that cancer centers provide incentives (eg, pay increases) based on SGM and other marginalized patients’ engagement and satisfaction with care. Additionally, we recommend the National Cancer Institute (NCI) include in its assessment of eligibility for NCI designation (1) the satisfaction, engagement, and outcomes of SGM and other marginalized patient populations compared with nonmarginalized patient populations, and (2) the satisfaction, retention, and promotion/rank of SGM and other marginalized clinicians and administrators.

ASCO and the National Institutes of Health have classified SGM persons as a population experiencing health disparities.39,45 Despite this designation, and the many health disparities experienced by SGM patients with cancer, the field of SGM cultural humility in oncology is in its infancy. Although there is much promise in improving structural, organizational, and clinical aspects of oncology care to meet the needs of SGM patients, more work is needed in developing frameworks for evaluation and specific measures of change. To build medical systems that are truly inclusive of marginalized people, we must be committed to radical change in our individual relationships and systems. These changes must be visualized and developed by marginalized patients and clinicians hand in hand with our allies with an eye toward achieving the ultimate goal of reducing discrimination and eliminating health disparities.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Meghan Bowman-Curci for her editing and assistance with formatting and the associate editor for insightful comments and suggestions.

Footnotes

Supported by National Cancer Institute grant No. K07 CA190529 (C.K.).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

What Exactly Are We Measuring? Evaluating Sexual and Gender Minority Cultural Humility Training for Oncology Care Clinicians

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/jco/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Gwendolyn P. Quinn

Honoraria: FLO Health

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boehmer U, Miao X, Ozonoff A. Cancer survivorship and sexual orientation. Cancer. 2011;117:3796–3804. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Quinn GP, Sanchez JA, Sutton SK, et al. Cancer and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender/transsexual, and queer/questioning (LGBTQ) populations. CA Cancer J Clin. 2015;65:384–400. doi: 10.3322/caac.21288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nash R, Ward KC, Jemal A, et al. Frequency and distribution of primary site among gender minority cancer patients: An analysis of U.S. national surveillance data. Cancer Epidemiol. 2018;54:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.canep.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boehmer U, Gereige J, Winter M, et al. Transgender individuals’ cancer survivorship: Results of a cross-sectional study. Cancer. 2020;126:2829–2836. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braun H, Nash R, Tangpricha V, et al. Cancer in transgender people: Evidence and methodological considerations. Epidemiol Rev. 2017;39:93–107. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxw003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamen CS, Alpert A, Margolies L. “Treat us with dignity”: A qualitative study of the experiences and recommendations of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) patients with cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2019;27:2525–2532. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4535-0. et al. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Milton J, et al. Health-related quality of life in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:225–236. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9947-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartman ME, Irvine J, Currie KL, et al. Exploring gay couples’ experience with sexual dysfunction after radical prostatectomy: A qualitative study. J Sex Marital Ther. 2014;40:233–253. doi: 10.1080/0092623X.2012.726697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thomas C, Wootten A, Robinson P. The experiences of gay and bisexual men diagnosed with prostate cancer: Results from an online focus group. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2013;22:522–529. doi: 10.1111/ecc.12058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boehmer U, Glickman M, Winter M. Anxiety and depression in breast cancer survivors of different sexual orientations. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:382–395. doi: 10.1037/a0027494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews AK, Peterman AH, Delaney P, et al. A qualitative exploration of the experiences of lesbian and heterosexual patients with breast cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2002;29:1455–1462. doi: 10.1188/02.ONF.1455-1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamen C, Palesh O, Gerry AA, et al. Disparities in health risk behavior and psychological distress among gay versus heterosexual male cancer survivors. LGBT Health. 2014;1:86–92. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2013.0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Margolies L. The psychosocial needs of lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender patients with cancer. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2014;18:462–464. doi: 10.1188/14.CJON.462-464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamen C, Blosnich JR, Lytle M, et al. Cigarette smoking disparities among sexual minority cancer survivors. Prev Med Rep. 2015;2:283–286. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2015.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schabath MB, Blackburn CA, Sutter ME, et al. National survey of oncologists at National Cancer Institute-designated comprehensive cancer centers: Attitudes, knowledge, and practice behaviors about LGBTQ patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37:547–558. doi: 10.1200/JCO.18.00551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shetty G, Sanchez JA, Lancaster JM, et al. Oncology healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes, and practice behaviors regarding LGBT health. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99:1676–1684. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2016.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown O, Ten Ham-Baloyi W, van Rooyen DR, et al. Culturally competent patient-provider communication in the management of cancer: An integrative literature review. Glob Health Action. 2016;9:33208. doi: 10.3402/gha.v9.33208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi AL, Lopez EJ. Contextualizing competence: Language and LGBT-based competency in health care. J Homosex. 2017;64:1330–1349. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashing KT, Chávez NR, George M. A health equity care model for improving communication and patient-centered care: A focus on oncology care and diversity, in Kissane DW, Bultz BD, Butow PN, et al (eds): Oxford Textbook of Communication in Oncology and Palliative Care. Oxford, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press. 2017:257–264. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Radix A, Maingi S. LGBT cultural competence and interventions to help oncology nurses and other health care providers. Semin Oncol Nurs. 2018;34:80–89. doi: 10.1016/j.soncn.2017.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tervalon M, Murray-García J. Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 1998;9:117–125. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Turan JM, Elafros MA, Logie CH, et al. Challenges and opportunities in examining and addressing intersectional stigma and health. BMC Med. 2019;17:7. doi: 10.1186/s12916-018-1246-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Metzl JMHH, Hansen H. Structural competency: Theorizing a new medical engagement with stigma and inequality. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:126–133. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feagin J, Bennefield Z. Systemic racism and U.S. health care. Soc Sci Med. 2014;103:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lie DA, Lee-Rey E, Gomez A, et al. Does cultural competency training of health professionals improve patient outcomes? A systematic review and proposed algorithm for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:317–325. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1529-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majumdar B, Browne G, Roberts J, et al. Effects of cultural sensitivity training on health care provider attitudes and patient outcomes. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2004;36:161–166. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wade P, Bernstein BL. Culture sensitivity training and counselor’s race: Effects on black female clients’ perceptions and attrition. J Couns Psychol. 1991;38:9–15. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clifford A, McCalman J, Bainbridge R, et al. Interventions to improve cultural competency in health care for Indigenous peoples of Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA: A systematic review. Int J Qual Health Care. 2015;27:89–98. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzv010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Bertakis KDFP, et al. The cost of satisfaction: A national study of patient satisfaction, health care utilization, expenditures, and mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:405–411. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: A systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:99. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jongen CS, McCalman J, Bainbridge RG. The implementation and evaluation of health promotion services and programs to improve cultural competency: A systematic scoping review. Front Public Health. 2017;5:24. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grove J. How competent are trainee and newly qualified counsellors to work with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients and what do they perceive as their most effective learning experiences? Couns Psychother Res. 2009;9:78–85. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rutter PA, Estrada D, Ferguson LK, et al. Sexual orientation and counselor competency: The impact of training on enhancing awareness, knowledge and skills. J LGBT Issues Couns. 2008;2:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bonvicini KA. LGBT healthcare disparities: What progress have we made? Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100:2357–2361. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dorsen C, Van Devanter N. Open arms, conflicted hearts: Nurse practitioner’s attitudes towards working with lesbian, gay and bisexual patients. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:3716–3727. doi: 10.1111/jocn.13464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hook JN, Davis DE, Owen J, et al. Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. J Couns Psychol. 2013;60:353–366. doi: 10.1037/a0032595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seay J, Hicks A, Markham MJ, et al. Web-based LGBT cultural competency training intervention for oncologists: Pilot study results. Cancer. 2020;126:112–120. doi: 10.1002/cncr.32491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Betancourt JR, Green AR, Carrillo JE, et al. Defining cultural competence: A practical framework for addressing racial/ethnic disparities in health and health care. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:293–302. doi: 10.1016/S0033-3549(04)50253-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Griggs J, Maingi S, Blinder V, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology position statement: Strategies for reducing cancer health disparities among sexual and gender minority populations. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:2203–2208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.0441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jabson JM, Mitchell JW, Doty SB. Associations between non-discrimination and training policies and physicians attitudes and knowledge about SGM. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:256. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2927-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Douglas C, Moody J, Broussard DA. Black beyond the rainbow: Clinical implications for the intersectionality of race, gender, and queer identity. J Black Sex Relatsh. 2019;5:21–41. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alpert AB, CichoskiKelly EM, Fox AD. What lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and intersex patients say doctors should know and do: A qualitative study. J Homosex. 2017;64:1368–1389. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1321376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boroughs MS, Andres Bedoya C, O’Cleirigh C, et al. Toward defining, measuring, and evaluating LGBT cultural competence for psychologists. Clin Psychol (New York) 2015;22:151–171. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Betancourt JR, Green AR. Commentary: Linking cultural competence training to improved health outcomes—Perspectives from the field. Acad Med. 2010;85:583–585. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b2f3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Institutes of Health Sex and gender minorities recognized as health disparity population. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/grants-contracts/sex-gender-minorities-health-disparity-population

- 46.Epstein RM, Street RL., Jr The values and value of patient-centered care. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9:100–103. doi: 10.1370/afm.1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]