Abstract

Prostate cancer is a common malignancy in men worldwide and it is known that oxidative stress is a risk factor for cancer development. A common functional haptoglobin (Hp) polymorphism, originating from a duplication of a gene segment spanning over two exons, results in three distinct phenotypes with different anti-oxidative capacities: Hp1-1, Hp1-2, and Hp2-2. The aim of the study was to investigate the relationship between this Hp polymorphism and prostate cancer mortality. The study was performed on 690 patients with histologically confirmed prostate cancer, recruited between January 2004 and January 2007. Hp genotypes were determined by a TaqMan fluorogenic 5′-exonuclease assay. Hp1-1 was present in 76 (11%), Hp1-2 in 314 (45.5%), and Hp2-2 in 300 (43.5%) patients. During a median follow-up of 149 months, 251 (35.3%) patients died. Hp genotypes were not significantly associated with higher overall mortality (HR 1.10; 95% CI 0.91–1.33; p = 0.34). This remained similar in a multivariate analysis including age at diagnosis, androgen deprivation therapy, and risk group based on PSA level, GS, and T stage (HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.91–1.34; p = 0.30). We conclude that the common Hp polymorphism does not seem to be associated with overall mortality in prostate cancer patients.

Subject terms: Cancer, Genetics, Molecular medicine, Oncology, Urology

Introduction

Prostate cancer is the second most common malignant tumor and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related mortality in men worldwide1. Although the etiology of prostate cancer is still not entirely understood, heredity, age, and ethnicity have been firmly established as risk factors2. In addition, it is known that reactive oxygen species play a role in malignant transformation, progression and the aggressive phenotype of prostate cancer3. More precisely, the accumulation of such radicals in cells results in modification of biomolecules such as proteins, lipids, and DNA. Subsequently these alterations lead to functional impairment of the cell and diseases like cancer or cardiovascular disease.

Hydroxyl radicals, the biologically most active free radicals, can be generated when hemoglobin (Hb) breaks free during hemolysis, due to the oxidative nature of iron-containing heme4. Hb found in the cytoplasm of red blood cells is a functionally important protein that, amongst other tasks, carries oxygen from the lungs to the tissues of the body. Haptoglobin (Hp) is involved in promoting the clearance of plasma Hb to prevent iron loss, kidney damage and the oxidative potential of the iron contained in the Hb molecule. Binding of the Hp-Hb complex to the membrane protein CD 163, found on macrophages and monocytes, subsequently leads to clearance of the entire complex by receptor-mediated endocytosis5.

Beyond the task of capturing Hb in the plasma, Hp is a positive acute-phase protein which serves as a bacteriostatic agent, an inhibitor of prostaglandin synthesis and angiogenesis6. It is synthesized in the liver in response to inflammatory cytokines and glucocorticoids7. Hp is characterized by a molecular heterogeneity on chromosome 16q22 that gives rise to 3 functionally and structurally distinct phenotypes: Hp1-1, Hp2-2, and the heterozygous Hp2-1. The allelic differences originate from crossover duplication, resulting in an Hp1 allele with 5 exons and an Hp2 allele with 7 exons8.

The Hp1 allele product binds to hemoglobin with a higher affinity compared to Hp2, leading to a higher antioxidant capacity of Hp19. The Hp2 allele results in higher B-cell and T-lymphocyte counts in the peripheral blood10, whereas the anti-inflammatory action is less pronounced compared to Hp1. People with Hp1-1 have the highest plasma concentrations, those with Hp2-2 the lowest, and the ones with Hp2-1 have concentrations lying in between11.

Due to the substantial differences in characteristics of the Hp1 and Hp2 proteins, several studies have investigated the impact of the Hp phenotype on cancer. Lee CC et al. showed an increased frequency of the Hp2-2 phenotype in people suffering from nasopharyngeal carcinoma12. Other studies reported an increased risk for the Hp1-1 phenotype for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia13 and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in kidney transplant patients14. Mandato VD et al. showed a better outcome for epithelial ovarian cancer for carriers of the Hp2-2 phenotype15.

For prostate cancer, no larger studies investigating the Hp polymorphism are available. Interestingly, Van Hemelrijck et al. found no association between serum haptoglobin levels and prostate cancer risk, whereas Arthur et al. reported an association of higher haptoglobin levels with increased risk of metastatic prostate cancer, but not with prostate cancer death or overall death16,17.

Aim of the present study was therefore to evaluate the potential association of the Hp polymorphism with long-term mortality in a large cohort of Caucasian prostate cancer patients.

Results

HP genotypes were successfully determined in 690 (98.3%) patients of the PROCAGENE study. In the remaining 12 subjects, no valid genotype result was achieved after three attempts. All further analyses were based upon the subset of 690 patients with valid HP genotypes measurements.

Demographic data and genotype frequencies are shown in Table 1. HP genotypes were not associated with tumor stage, Gleason score or risk group. Median follow-up time was 149 months. During follow-up, 251 (35.3%) patients died.

Table 1.

Demographic data of study participants stratified by haptoglobin (HP) phenotypes.

| Hp1-1 | Hp1-2 | Hp2-2 | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 76 | 314 | 300 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | 67.7 ± 6.8 | 68.6 ± 7.0 | 67.8 ± 7.2 | 0.31 |

| Stage | ||||

| T1/T2 | 36 (50.7) | 161 (56.7) | 151 (54.9) | 0.66 |

| T3/T4 | 35 (49.3) | 123 (43.3) | 124 (45.1) | |

| Gleason score | ||||

| < 7 | 47 (61.8) | 192 (61.3) | 175 (58.3) | 0.71 |

| ≥ 7 | 29 (38.2) | 121 (38.7) | 125 (41.7) | |

| PSA at diagnosis | ||||

| < 10 | 31 (42.5) | 170 (56.5) | 162 (56.6) | 0.16 |

| 10–20 | 22 (30.1) | 75 (24.9) | 62 (21.7) | |

| > 20 | 20 (27.4) | 56 (18.6) | 62 (21.7) | |

| Risk group | ||||

| Low | 10 (13.2) | 61 (19.4) | 64 (21.3) | 0.43 |

| Intermediate | 21 (27.6) | 87 (27.7) | 70 (23.6) | |

| High | 45 (59.2) | 166 (52.9) | 166 (53.3) | |

| Death during follow-up | 21 (27.6) | 110 (35.0) | 120 (40.0) | 0.108 |

Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, or number of subjects (percentage). Gleason score was available for 689 (99.9%) subjects, PSA at first diagnosis was available for 660 (95.7%) subjects and stage data were available for 630 (91.3%) subjects.

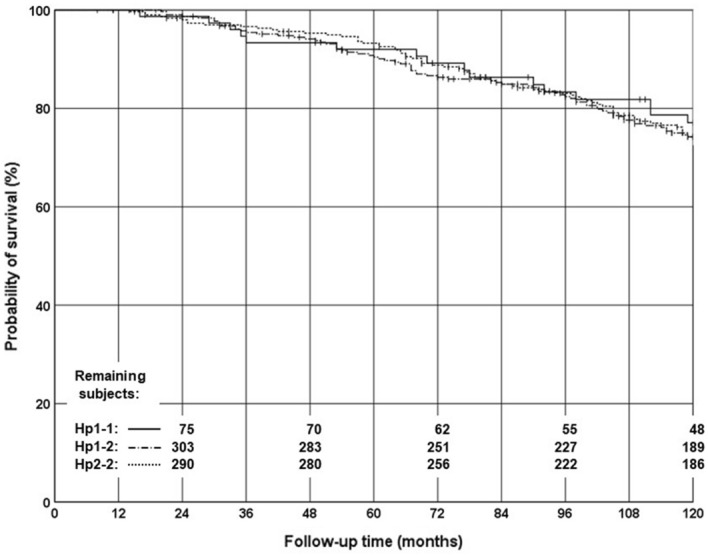

In a univariate Cox regression analysis, HP genotypes were not significantly associated with higher overall mortality (HR 1.10; 95% CI 0.91–1.33; p = 0.34) (Fig. 1). Similarly, in a multivariate Cox regression model including age at diagnosis, androgen deprivation therapy, and risk group (based on PSA level, GS, and T stage), HP genotypes showed no association with overall mortality (HR 1.11; 95% CI 0.91–1.34; p = 0.30).

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier curves of overall survival. The solid line indicates the Hp1-1 genotype, the dash-dotted line the Hp1-2 genotype, and the dotted line the Hp2-2 genotype. Vertical dashes on the lines indicate censored cases. The remaining subjects at risk in each genotype group are given in intervals of 24 months.

The study had a statistical Power of more than 0.80 to exclude a HR of 1.44 or higher for carriers of the Hp2-2 genotype, and to exclude a HR of 1.77 or higher for carriers of an Hp2 allele (Hp1-2 and Hp2-2 combined).

In the majority of patients, follow-up data did not allow to discriminate between prostate cancer specific death and death from other causes.

Discussion

On the one hand, it has been shown in previous studies that Hp polymorphism plays a role in susceptibility to certain cancers and outcome of the disease12–14. On the other hand, Mavondo et al. propose that Hp polymorphism is associated with neither the risk of developing prostate cancer nor outcome of disease in people of African origin. However, their study included only a brief follow up time of 18 months coupled with a small sample size. Since allele frequency of Hp1 and incidence of prostate cancer is higher in African American ancestry compared to Caucasians18, the study at hand explored the impact of Hp polymorphism and its prognostic value in Caucasians with prostate cancer. Therefore, Hp genotypes in 690 patients were determined with a median survival follow-up time of 149 months. The data indicate that there is no association between Hp polymorphism and overall mortality in prostate cancer patients.

The Hp polymorphism comprises a larger duplication, which is usually not captured by whole genome association studies. To the best of our knowledge there is no single nucleotide polymorphism in strong linkage disequilibrium with the Hp polymorphism, therefore no data from larger consortia are available for this polymorphism.

However, some limitations of the present study should be taken into account: No serum Hp levels were measured. Therefore, we cannot conclude that Hp levels in the blood or tissue have no effect on the survival of Caucasians with prostate cancer. In fact, Tai et al. showed that tissue Hp expression is highly correlated with better hepatocellular carcinoma tumor differentiation and increased five-year overall survival rate19. This still needs to be elucidated in patients with prostate cancer.

Furthermore, Goldenstein et al. suggest that the risk of developing vascular complications in Hp 2–2 individuals is likely due to the impaired ability of the Hp 2–2 protein to prevent Hb-driven oxidation. But they also found that vitamin E may be protective against cardiovascular disease in individuals comprising the Hp 2–2 phenotype20. However, for the present work data on the Vitamin E levels or parameter of oxidative stress were not available and thus could not be considered in the analysis.

Although our data suggest that the Hp gene polymorphism has little if any relevance for prostate cancer prognosis, this does not necessarily exclude a role of this polymorphism for other cancers. Previous studies reported associations of the Hp polymorphism with a variety of cancers, such as actinic keratosis, esophageal cancer, cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma, nasopharyngeal carcinoma, cervical neoplasia, and breast cancer12–14,21–23. Interestingly, for some cancers the greater risk was conferred by the Hp1 allele, whereas for others the greater risk was conferred by the Hp2 allele. The pathological mechanisms leading to these different effects of the Hp polymorphism in different cancers is currently unclear.

To conclude, this paper presents the first large scale study that provides evidence that genetic variability in the Hp gene seems not to play a prognostic role in Caucasians with prostate cancer.

Methods

The Austrian Prostate Cancer Genetics (PROCAGENE) study included 702 prostate cancer patients who were recruited between January 2004 and January 2007. A detailed description has been published previously24–26. Briefly, PROCAGENE is a prospective study aimed to investigate genetic risk factors, functional relationships between genetic variations and clinical phenotypes, genetically modified response to radiotherapy (radiogenomics), and the prognostic importance of genetic markers27–30.

Participants of PROCAGENE were male patients with sporadic, histologically confirmed prostate cancer, treated with radiotherapy. All subjects were Caucasian. Clinical characteristics were obtained from medical records and prostate cancer patients were stratified into low-, intermediate-, and high-risk groups according to the NCCN guidelines31. A total of 454 patients (64.7%) received neo-adjuvant androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), 153 patients (21.8%) were treated with additional adjuvant ADT. The administration of ADT was at the discretion of the treating urologists and generally recommended in intermediate and high risk patients.

Follow-up examinations were performed in regular intervals at the Department of Therapeutic Radiology and Oncology26. The primary study endpoint was overall mortality.

The study was performed according to the Austrian Gene Technology Act and has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical University of Graz. Written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects. All subjects were Caucasian.

Genotypes were determined by a TaqMan fluorogenic 5′-exonuclease assay (Applied Biosystems, Austria) as described previously32.

Statistical analysis was done using IBM SPSS statistics 25 software (IBM Deutschland GmbH, Ehningen, Germany). Continuous variables were compared between groups by univariate analysis of variance (ANOVA). Hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were analyzed by Cox regression analyses assuming additive effects of the HP alleles. For this analysis, genotypes were coded corresponding to the number of HP-2 alleles (HP 1/1 genotype = 0; HP 1/2 genotype = 1; HP 2/2 genotype = 2). Median follow-up times were calculated according to Schemper and Smith33. The criterion for statistical significance was p < 0.05.

Research involving human participants

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments. The study has been approved by the Ethical Committee of the Medical University of Graz.

Informed consent

Written informed consent was obtained from all participating subjects.

Author contributions

M.K.: Protocol/project development, data analysis, manuscript writing/editing. E.-M.T.: data collection, manuscript writing/editing. H.M.: data analysis, manuscript writing/editing. M.H.: manuscript writing/editing. M.D.S.: manuscript writing/editing. W.R.: protocol/project development, data collection, data analysis. T.L.: protocol/project development, data collection, data analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bray F, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: Globacan estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leitzmann MF, Rohrmann S. Risk factors for the onset of prostatic cancer: Age, location, and behavioral correlates. Clin. Epidemiol. 2012;4:1–11. doi: 10.2147/CLEP.S16747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khandrika L, Kumar B, Koul S, Maroni P, Koul HK. Role of oxidative stress in prostate cancer. Cancer Lett. 2009;282:125–136. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadrzadeh SM, Graf E, Panter SS, Hallaway PE, Eaton JW. Hemoglobin. A biologic fenton reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:14354–14356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kristiansen M, et al. Identification of the haemoglobin scavenger receptor. Nature. 2001;409:198–201. doi: 10.1038/35051594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Langlois MR, Delanghe JR. Biological and clinical significance of haptoglobin polymorphism in humans. Clin. Chem. 1996;42:1589–1600. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/42.10.1589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang Y, Kinzie E, Berger FG, Lim SK, Baumann H. Haptoglobin, an inflammation-inducible plasma protein. Redox. Rep. 2001;6:379–385. doi: 10.1179/135100001101536580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robson EB, Polani PE, Dart SJ, Jacobs PA, Renwick JH. Probable assignment of the alpha locus of haptoglobin to chromome 16 in man. Nature. 1969;223:1163–1165. doi: 10.1038/2231163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lange V. Haptoglobin polymorphism—not only a genetic marker. Anthropol. Anz. 1992;50:281–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Langlois M, et al. Distribution of lymphocyte subsets in bone marrow and peripheral blood is associated with haptoglobin type. Binding of haptoglobin to the B-cell lectin CD22. Eur. J. Clin. Chem. Clin. Biochem. 1997;35:199–205. doi: 10.1515/cclm.1997.35.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Imrie H, et al. Haptoglobin levels are associated with haptoglobin genotype and alpha +-Thalassemia in a malaria-endemic area. Am. J. Trop. Hyg. 2006;74:965–971. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2006.74.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee CC, et al. Haptoglobin genotypes in nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Int. J. Biol. Mark. 2009;24:32–37. doi: 10.1177/172460080902400105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahmud SM, et al. Haptoglobin phenotype and risk of cervical neoplasia, a case-control study. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2007;385:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speeckaert R, et al. The haptoglobin phenotype influences the risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in kidney transplant patients. J. Eur. Acad. Dermatol. Venereol. 2012;26:566–571. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2011.04112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mandato VD, et al. Haptoglobin phenotype and epithelial ovarian cancer. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:4353–4358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Van Hemelrijck M, et al. Risk of prostate cancer is not associated with levels of C-reactive protein and other commonly used markers of inflammation. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;129:1485–1492. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arthur R, et al. Serum inflammatory markers in relation to prostate cancer severity and death in the Swedish AMORIS study. Int. J. Cancer. 2018;142:2254–2262. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Odedina FT, et al. Prostate cancer disparities in Black men of African descent, a comparative literature review of prostate cancer burden among Black men in the United States, Caribbean, United Kingdom, and West Africa. Infect. Agent Cancer. 2009;10(4 Suppl 1):S2. doi: 10.1186/1750-9378-4-S1-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tai CS, et al. Haptoglobin expression correlates with tumor differentiation and five-year overall survival rate in hepatocellular carcinoma. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0171269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldenstein H, Levy NS, Ward J, Costacou T, Levy AP. Haptoglobin genotype is a determinant of hemoglobin adducts and vitamin E content in HDL. J. Diabetes Res. 2018;2018:6125420. doi: 10.1155/2018/6125420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brochez L, Speeckaert R, De Bacquer D, Delanghe J, Hoorens I. Haptoglobin polymorphism and the risk of actinic keratoses and cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: A case-control study. J Dermatol. 2019;46:274–275. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hosseinzadeh S, Alipanah-Moghadam R, Isapanah Amlashi F, Nemati A. Evaluation of haptoglobin genotype and some risk factors of cancer in patients with early stage esophageal cancer. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2019;20:2897–2901. doi: 10.31557/APJCP.2019.20.10.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Awadallah SM, Atoum MF. Haptoglobin polymorphism in breast cancer patients form Jordan. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2004;341:17–21. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2003.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Langsenlehner T, et al. The Glu228Ala polymorphism in the ligand binding domain of death receptor 4 is associated with increased risk for prostate cancer metastases. Prostate. 2008;68:264–268. doi: 10.1002/pros.20682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langsenlehner T, et al. Impact of VEGF gene polymorphisms and haplotypes on radiation-induced late toxicity in prostate cancer patients. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2011;187:784–791. doi: 10.1007/s00066-011-1106-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Trummer O, et al. Vitamin D and prostate cancer prognosis, a Mendelian randomization study. World J. Urol. 2016;34:607–611. doi: 10.1007/s00345-015-1646-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langsenlehner T, et al. Association of genetic variants in VEGF-A with clinical recurrence in prostate cancer patients treated with definitive radiotherapy. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2014;190:364–369. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0503-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thurner EM, et al. Association of genetic variants in apoptosis genes FAS and FASL with radiation-induced late toxicity after prostate cancer radiotherapy. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2014;190:304–309. doi: 10.1007/s00066-013-0485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langsenlehner T, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and haplotypes in the gene for vascular endothelial growth factor and risk of prostate cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2008;44:1572–1576. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Langsenlehner T, et al. Association between single nucleotide polymorphisms in the gene for XRCC1 and radiation-induced late toxicity in prostate cancer patients. Radiother. Oncol. 2011;98:387–393. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mohler J, et al. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology, prostate cancer. J. Natl. Comp. Cancer Netw. 2010;8:162–200. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2010.0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Renner W, Jahrbacher R, Marx-Neuhold E, Tischler S, Zulus B. A novel exonuclease (TaqMan) assay for rapid haptoglobin genotyping. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2016;54:781–783. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2015-0586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schemper M, Smith TL. A note on quantifying follow-up in studies of failure time. Control. Clin. Trials. 1996;17:343–346. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(96)00075-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]