Abstract

Background

Primary care physician (PCP) burnout is prevalent and on the rise. Physician burnout may negatively affect patient experience of care.

Objective

To identify the direct impact of PCP burnout on patient experience in various domains of care.

Design

A cross-sectional observational study using physician well-being (PWB) surveys collected in 2016–2017, linked to responses from patient experience of care surveys. Patient demographics and practice characteristics were derived from the electronic health record. Linked data were analyzed at the physician level.

Setting

A large non-profit multi-specialty ambulatory healthcare organization in northern California.

Participants

A total of 244 physicians practicing internal medicine or family medicine who responded to the PWB survey (response rate 72%), and 30,701 completed experience surveys from patients seeing these physicians.

Measurements

Burnout was measured with a validated single-item question with a 5-point scale ranging from (1) enjoy work to (5) completely burned out and seeking help. Patient experience of patient-provider communication, access, and overall rating of provider was measured with Clinician & Group Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers & Systems (CG-CAHPS) survey. Patient experience scores (0–100 scale) were adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity, and English proficiency.

Results

Physician burnout had a negative impact on patient-reported experience of patient-provider communication but not on access or overall rating of providers. A one-level increase in burnout was associated with 0.43 decrease in adjusted patient-provider communication experience score (P < 0.01).

Limitations

Data came from a single large healthcare organization. Patterns may differ for small- and mid-sized practices.

Conclusion

Physician burnout adversely affects patient-provider communication in primary care visits. Efforts to improve physician work environments could have a meaningful positive impact on patient experience as well as physician well-being.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s11606-020-05770-w) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

KEY WORDS: physician burnout, patient experience, access, patient-provider communication

INTRODUCTION

Physician burnout has reached alarming rates in many countries, with recent national surveys in the United States (US) indicating more than half of physicians experiencing symptoms of burnout.1 Primary care physicians (PCPs) in the US may experience higher rates of burnout than other specialties.1 Shortages of PCPs2 along with a growing workload associated with the widespread use of electronic health records (EHR) and patient portals are key contributors to PCP burnout.3–6 EHR adoption over the past two decades has reshaped PCP practices and how they interact with patients both during and outside office encounters. Recent studies indicate that a half of PCP’s total work time is spent working on the computer outside of visits, including documenting patient visits in the EHR, reviewing laboratory test results, renewing medications, and responding to messages from clinical staff and patients,4, 5 and that EHR functionality is related to work stress and satisfaction.3, 6

Burnout not only has detrimental personal consequences for physicians, but also can negatively affect patient outcomes.1, 7 Recent systematic reviews found that physician burnout negatively affects patient safety (e.g., increased medical errors) and quality of care in general, but these observations are largely derived from hospital settings, focusing on clinical outcomes.8–11 The Quadruple Aim framework suggests that an engaged, healthy workforce is a key driver of improved patient experience, ultimately leading to better clinical outcomes and reduced healthcare costs.12, 13

Little is known about the consequences of physician burnout on patient experience in primary care, and results from the few published studies to date are inconclusive. Two studies—one surveying 30 PCPs in Greece14 and another studying 239 general practitioners in the Netherlands,15 respectively—reported an overall negative relationship between PCP burnout and patient experience. On the other hand, a study of 305 PCPs in Germany reported no relationship between physician job satisfaction and patient satisfaction.16 To our knowledge, no study to date has reported the linkage between physician burnout and patient-reported experience of care in outpatient care settings in the US.

We sought to identify the impact of PCP burnout on patient-reported experience of care in three key domains: appointment availability, communication with provider, and overall provider rating. We hypothesized that physician burnout has a direct negative effect on patient-provider communication and overall rating of the provider while it has no direct effect on patient access, e.g., appointment availability, after taking into account measures of PCP panel size and workload.

METHODS

Study Design/Setting/Participants

We conducted a cross-sectional observational study using surveys and linked EHR data from a large non-profit multi-specialty ambulatory healthcare organization in northern California in the US. Study participants were primary care physicians (PCPs) practicing internal or family medicine. At the time of the survey, the organization had a total of 369 PCPs across 40 work sites in and around the San Francisco Bay Area, ranging from urban, exurban, to rural areas.

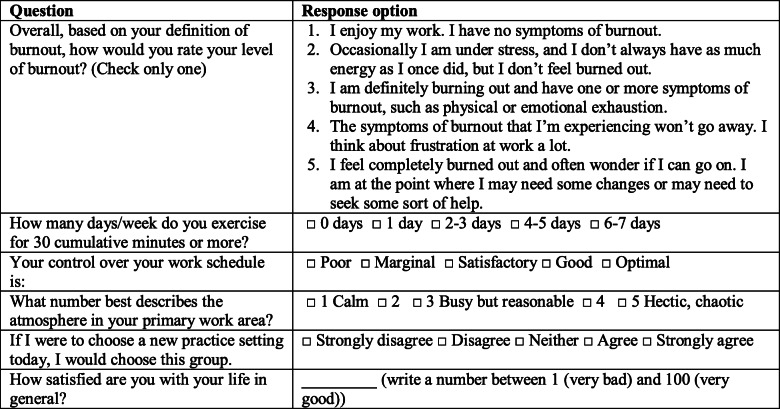

The Physician Well-being (PWB) survey was fielded between November 2016 and April 2017 as part of the organization’s efforts to understand and address physician burnout. All physicians were invited to respond to a confidential one-page survey asking about multiple dimensions of well-being including burnout, life satisfaction, time spent on self-care practices and work-related activities, workload, departmental climate, and level of autonomy (Table 1). The introduction to the survey clearly stated that survey responses would be confidential, all data would be handled by the research team alone, and no health system leaders would see any individual level data. The PWB survey achieved an overall response rate of 72%.3

Table 1.

Selected Questions from the Physician Well-being Survey

Patient experiences of care surveys are routinely collected as part of the organization’s quality improvement efforts using the Clinical and Group version of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CG-CAHPS). Developed through rigorous processes, including seeking stakeholder input iteratively, assessing psychometric properties, and conducting field tests,17–19 the CG-CAHPS is considered the standard patient experience survey and used in performance evaluation programs by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and other payers in the US.20

The surveys were sent via mail to patients who had an office visit encounter with a provider. Patients were randomly selected from the patients each provider saw, with a target of collecting 60 completed surveys per provider each year, which was implemented as 5 per month. Response rates ranged from 15 to 20%, typical of patient experience surveys sent without financial incentives or reminders.21, 22 While response rates vary by patient demographics, e.g., older and non-Hispanic white individuals are more likely to respond,23–27 potential bias due to low response rate at provider level, after adjusting for respondent characteristics, is unknown. We selected responses to the visits with 244 physicians practicing internal medicine or family medicine during June 1, 2016, to May 31, 2017, ± 2–3 months before and after PWB survey fielding. The CG-CAHPS data are aggregated at provider level, with an average of 126 (SD = 44; range 11–258) surveys per PCP, adjusting for patient age, gender, and race/ethnicity.

The PWB and CG-CAHPS survey data were linked at the PCP level, and information on physician demographics, panel size, and panel demographic and clinical characteristics as of 2016, extracted from administrative records and the EHR, were added. All data were collected as part of routine clinical practice and quality improvement. The Sutter Health Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol. Data analysis was conducted between May 2018 and June 2019.

Variables/Measurement/Bias

Patient-Reported Experience of Care (Outcome)

We used CG-CAHPS questions asking about three domains of experiences: (1) provider communication: how well providers communicate with patients (4 questions: Provider explained things in a way that was easy to understand; provider listened carefully to patient; provider showed respect for what patient had to say; and provider spent enough time with patient); (2) access: getting timely appointments, care, and information (3 questions: Patient got appointment for urgent care as soon as needed; patient got appointment for non-urgent care as soon as needed; and patient got answer to medical question the same day he/she contacted provider’s office); and (3) provider rating: patients’ overall rating of the provider (1 question). We computed composite scores for each domain in a scale of 0 to 100 (www.ahrq.gov/cahps/surveys-guidance/cg/about/survey-measures.html).

Domain-specific scores were aggregated at the PCP level. Scores were adjusted for patient characteristics including age, gender, race/ethnicity, and English proficiency, which are known to be associated with response patterns independent of patient experience itself.23, 28 While patient experience survey response rates are low, typically 15–30%,29 and can be positively biased (as patients with better experience are more likely to respond), there is no reason we are aware of to believe potential bias would be systematically different across PCPs, after taking into account relevant respondent demographic characteristics.

Burnout (Exposure/Predictor)

The degree of burnout was measured with the Physician Work-Life Study’s single-item burnout question, a validated 5-point scale variable from the PWB survey, ranging from 1 (enjoy work) to 5 (completely burned out)30 (Table 1). The measure has been validated against the commonly used, though proprietary and lengthy Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI).30–32 While there is a strong correlation between the two measures, recent data suggest the one-item measure using a dichotomous cut-point33 may underestimate the prevalence of burnout compared with the gold standard MBI measure.34 We therefore used the complete 5-point scale as a continuous variable to capture the full spectrum of burnout.

Practice Characteristics (Potential Confounders)

Characteristics of PCPs, including their workload, and panel composition are potential confounders of the relationship between burnout and patient-reported experience of care, and were accounted for with the following variables. Clinical full time equivalent (cFTE) was derived from administrative data, based on the number of hours spent seeing patients. We defined adjusted panel size as the number of patients a PCP saw during a year, applying weights based on expected workload (measured with work relative value units) given patient age and gender. Another indicator of panel characteristics is the proportion of visits made by a PCP’s own patient, rather than other PCPs’ patients. Newer PCPs generally have more availability in their schedule, and therefore have more visits by other PCPs’ patients. Physician gender, years of medical practice, and specialty (internal vs. family medicine) were also included.

Physician Well-Being, Department Climate, and Job Satisfaction (Correlates of Burnout)

Growing evidence suggests that more chaotic workplaces, less control over work, workload and time pressure have been associated with increased burnout in primary care.4, 30, 35–40 Life satisfaction has also been shown to be associated with burnout.41, 42 In our PWB survey, these correlates of burnout were measured with questions asking about the department climate,39, 43 degree of control over work schedule and workload (from the American Medical Association’s Mini-Z survey derived from the Physician Worklife Survey),44 degree of life satisfaction,45 and self-care practices (sleep hours, exercise frequency, mindfulness practices46–48 (Table 1). After specification tests as described below, the following variables were included in the analysis: a continuous variable indicating the degree of life satisfaction and dichotomous variables indicating calmer department climate (1: calm to 3: reasonable vs. 4 to 5: hectic to chaotic), good control over the schedule, and willingness to choose to work in the same practice again.

Statistical Methods

Relationships between level of burnout and adjusted patient experience scores, physician practice characteristics, and responses to other physician well-being items (that were used as instruments), respectively, were compared with one-way analysis of variance for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-squared test for categorical variables.

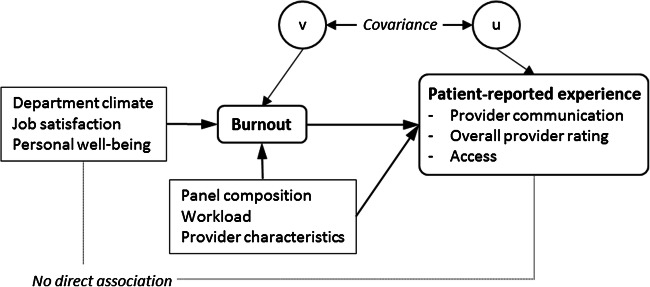

We used structural equation models (SEM) with instruments to estimate the direct relationship between PCP burnout and patient-reported experiences, while controlling for potential confounders, e.g., objective indicators of PCP workload.49–52 Correlates of physician burnout collected through the PWB survey including department climate, control over work schedule, intent to choose the practice again, regular exercise, and life satisfaction were chosen as potential instruments as they are known to be highly correlated with burnout39, 41, 42, 44, 45 but may not be directly related to patient experience once burnout is taken into account (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the relationship between PCP burnout and patient-reported experience score, and its moderators.

Prior to conducting SEM, we carefully selected valid instruments with various specification tests. For the main outcome of provider communication, it was determined that the covariance of burnout and patient experience scores were substantial and significant (Hausman test: χ2(1) = 3.85; P < 0.05) and that, while the selected instruments were strong predictors of burnout (F(5,222) = 27.9; P < 0.001; partial R2 = 0.39), they had no direct association with patient experience scores (LR test: χ2(4) = 3.06, P > 0.55) (Table 3). Specification test results were similar for provider rating and access. Using these valid instruments, we employed SEM with maximum likelihood methods to simultaneously estimate equations for burnout and each of patient experience measures. The analysis was conducted using STATA 14.2 (College Station, TX).

Table 3.

Association of Burnout and Patient-Reported Experience of Care—Results from Structural Equation Modeling with Instrumental Variable

| Patient-reported experience of care* | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provider communication | Rate provider | Access | ||||

| Variables | Coeff. | S.E. | Coeff. | S.E. | Coeff. | S.E. |

| Equation 1. Burnout (1–5) | ||||||

| Department atmosphere: calm to reasonable | − 0.26‡ | (0.094) | − 0.0098 | (0.03) | − 0.25‡ | (0.10) |

| Good control over work schedule | − 0.18 | (0.10) | − 0.016† | (0.007) | − 0.17 | (0.10) |

| Would choose the practice again | − 0.67‡ | (0.10) | 0.062 | (0.033) | − 0.68‡ | (0.10) |

| Exercise 4+ a week | − 0.12 | (0.10) | 0.037 | (0.10) | − 0.1 | (0.10) |

| Life satisfaction/100 (0–1) | − 1.87‡ | (0.30) | 0.13 | (0.092) | − 1.87‡ | (0.30) |

| Clinical FTE/10 (1–10) | − 0.0096 | (0.031) | − 0.018‡ | (0.005) | − 0.0098 | (0.031) |

| Adjusted panel size/100 (0.7–58) | − 0.017† | (0.007) | − 0.26‡ | (0.10) | − 0.016† | (0.007) |

| Proportion of own patient visits/10 (3.6–9.5) | 0.062 | (0.03) | − 0.19 | (0.10) | 0.061 | (0.033) |

| Female provider | 0.038 | (0.10) | − 0.68‡ | (0.10) | 0.037 | (0.10) |

| Internal medicine | 0.13 | (0.09) | − 0.11 | (0.10) | 0.13 | (0.092) |

| Years of medical practice (4–48) | − 0.018‡ | (0.005) | − 1.85‡ | (0.30) | − 0.019‡ | (0.005) |

| Intercept | 5.01‡ | (0.46) | 5.00‡ | (0.46) | 5.01‡ | (0.46) |

| Equation 2. Patient experience score (0–100) | ||||||

| Burnout (1–5) | − 0.26‡ | (0.094) | − 0.33 | (0.23) | − 0.59 | (0.32) |

| Clinical FTE/10 (1–10) | − 0.11 | (0.078) | − 0.22† | (0.09) | − 0.058 | (0.12) |

| Adjusted panel size/100 (0.7–58) | − 0.013 | (0.017) | − 0.015 | (0.02) | − 0.04 | (0.026) |

| Proportion of own patient visits/10 (3.6–9.5) | 0.0044 | (0.08) | 0.069 | (0.10) | 0.021 | (0.13) |

| Female provider | 0.84‡ | (0.26) | 1.50‡ | (0.29) | − 2.37‡ | (0.40) |

| Internal medicine | 0.93‡ | (0.23) | 1.88‡ | (0.26) | 1.91‡ | (0.36) |

| Years of medical practice (4–48) | 0.037‡ | (0.013) | 0.10‡ | (0.02) | 0.041† | (0.020) |

| Intercept | 88.8‡ | (1.00) | 81.5‡ | (1.12) | 68.0‡ | (1.56) |

| Variance (Eq. 1) | 0.49‡ | (0.04) | 0.49‡ | (0.04) | 0.49‡ | (0.044) |

| Variance (Eq. 2) | 3.08‡ | (0.29) | 3.91‡ | (0.36) | 7.55‡ | (0.70) |

| Covariance (var1 × var2) | 0.23 | (0.13) | 0.13 | (0.14) | 0.22 | (0.20) |

| LR test of model versus saturated χ2(4), P value | 3.06 | P = 0.55 | 2.03 | P = 0.73 | 1.80 | P = 0.77 |

*Number of observations = 224; †P < 0.05; ‡P < 0.01

RESULTS

Of the 369 PCPs who were invited to complete the PWB survey, 248 (67.2%) returned the survey with valid responses to burnout and well-being questions. After further excluding 4 PCPs who lacked information on practice characteristics, 244 PCPS were included in the overall analysis. Those who were excluded due to non-response to the survey or other missing values did not differ from the included PCPs in patient experience scores, although there were some differences in practice characteristics with excluded PCPs being more likely to be newer to the organization and to have a higher clinical FTE but smaller patient panels (Supplemental Table 1).

The average patient experience score for each domain, adjusting for respondent demographic factors, was highest for provider communication (mean [SD] = 88.3 [1.9]), followed by the overall provider rating (83.1 [2.6]) and lowest for access (65.5 [3.2]) (Table 2). Two thirds of PCPs (65.2%) were female and about half (53.6%) practiced family medicine. On average, PCPs had 20 years of medical practice experience.

Table 2.

Summary Statistics: Overall and Comparison by Burnout Response

| All (N = 244) | Enjoy work (N = 21; 8.6%) | Occasionally under stress (N = 112; 45.9%) (referent group)* | Burn out (N = 76; 31.2%) | Frustration (N = 24; 9.8%) | Seeking help (N = 11; 4.5%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable (min–max) | Mean | [SD] | Mean | [SD] | Mean | [SD] | Mean | [SD] | Mean | [SD] | Mean | [SD] |

| Adjusted patient experience score (0–100) | ||||||||||||

| Provider communication | 88.3 | [1.9] | 88.7 | [2.0] | 88.3 | [2.0] | 88.4 | [1.7] | 87.9 | [2.1] | 88.4 | [2.1] |

| Provider rating | 83.1 | [2.6] | 83.5 | [2.7] | 83.0 | [2.6] | 83.1 | [2.5] | 82.7 | [2.8] | 83.7 | [2.2] |

| Access | 65.4 | [3.2] | 65.9 | [3.8] | 65.6 | [3.1] | 65.6 | [2.9] | 64.5 | [3.6] | 64.2 | [3.9] |

| Physician practice characteristics | ||||||||||||

| Clinical FTE (10–100%) | 68.9 | [16.9] | 62.0† | [21.3] | 71.2 | [18.3] | 70.7 | [14.9] | 62.1† | [18.9] | 62.3 | [12.1] |

| Adjusted panel size (1–5803) | 2349 | [825] | 2255 | [799] | 2471 | [845] | 2419 | [732] | 1910‡ | [777] | 1804† | [1025] |

| Proportion of own patient visits (0–95%) | 72.8 | [15.7] | 67.82 | [20.0] | 72.1 | [18.2] | 73.4 | [12.7] | 76.5 | [7.5] | 77.4 | [8.8] |

| Female | 65.2% | 60.0% | 59.0% | 70.3%† | 69.6% | 90.9%† | ||||||

| Internal medicine | 45.9% | 25.0%† | 47.6% | 48.6% | 47.8% | 45.5% | ||||||

| Years of medical practice4–47 | 20.2 | [9.4] | 28.3‡ | [11.5] | 20.0 | [9.2] | 18.4 | [8.4] | 20.0 | [9.7] | 20.7 | [8.6] |

| Correlates of burnout (instruments) | ||||||||||||

| Calm department climate | 49.8% | 75.0% | 59.0% | 43.2%† | 26.1%‡ | 9.1%‡ | ||||||

| Good control over work schedule | 34.8% | 60.0% | 47.6% | 16.2%‡ | 26.1%† | 9.1%‡ | ||||||

| Would choose the practice again | 65.7% | 80.0% | 87.6% | 52.7%‡ | 13.0%‡ | 27.3%‡ | ||||||

| Exercise 4+ a week | 34.8% | 75.0%‡ | 35.2% | 27.0% | 26.1% | 27.3% | ||||||

| Life satisfaction (0–100) | 79.6 | [16.0] | 89.5 | [6.2] | 84.4 | [13.6] | 75.8‡ | [13.9] | 70.7‡ | [14.1] | 59.5‡ | [30.5] |

*Compared with the “Occasionally under stress” (referent group), difference in mean values are statistically significant: † = P < 0.05, ‡ = P < 0.01

In bivariate analysis, the patient experience scores of all three domains did not differ by PCP’s level of burnout (P > 0.05). Physician practice characteristics differed substantially by level of burnout. Compared with PCPs who reported to be occasionally under stress (level 2 of 5 on the burnout scale) (n = 105; 45.1%), PCPs who reported enjoying work (level 1 of 5 on burnout scale) (n = 20; 8.6%) had lower clinical FTE (62.0 vs. 71.2%; P < 0.05) and more years of medical practice (28.3 vs. 20.0; P < 0.01), and practiced family medicine (75.0% vs. 52.4%; P < 0.05). Compared with those reporting occasionally under stress, PCPs who were burning out (level 3 of 5) (n = 74; 31.8%) were more likely to be female (70.3 vs. 59.0%; P = 0.05), PCPs who were burnt-out and frustrated (level 4 of 5) (n = 23; 9.9%) were likely to have lower clinical FTE (62.1 vs. 71.2%; P < 0.05) and smaller adjusted panel size (1910 vs. 2471; P < 0.01), and PCPs who were burnt out to the level of seeking help (level 5 of 5) (n = 11; 4.7%) were more likely to be female (90.9% vs. 59.0%; P < 0.05).

In the structural equation models with adjustment of all covariates, selected instruments for burnout (i.e., life satisfaction, calmer department climate, good control over the work schedule, and willingness to choose to work in the same practice again) showed strong correlations with burnout in the expected direction; e.g., PCPs who felt that their department is calm to reasonable (vs. 4 to 5: hectic/chaotic) reported a lower level of burnout by 0.27 (in 1–5 scale) (P < 0.01) (see Table 3 for the association of other characteristics and burnout).

The structural equation models showed a statistically significant, but clinically marginal, negative relationship between the degree of burnout and patient-reported experiences of provider communication such that a one-level increase in burnout was associated with 0.43 percentage points decrease in the adjusted score (P < 0.01) (Table 3). For the provider rating and access domains, the relationship was in the same, negative, direction, but was not statistically significant. Female providers were more likely to receive higher scores on provider communication and provider rating by 0.84 and 1.49, respectively (P < 0.01), but lower for access by 2.37 (P < 0.01). Practicing internal medicine versus family medicine was associated with higher patient experience scores for all three domains, by 0.93 (provider communication), 1.88 (rate provider), and 1.90 (Access) (all P < 0.01). Similarly, longer years of medical practice was associated with higher patient experience scores in all three domains, by 0.038 (P < 0.01) (provider communication), 0.10 (P < 0.01) (rate provider), and 0.041 (P < 0.05) (access). Clinical FTE, adjusted panel size, and proportion of seeing own patients were not associated with patient-reported experiences.

DISCUSSION

We found that the negative effect of burnout is not limited to physicians’ own well-being but also impacts patient experience. A higher degree of burnout was associated with poorer patient experience in providers’ communication with patients. The magnitude of the relationship was modest (0.43 percentage point per each level in burnout scale) in part due to the ceiling effect in patient experience surveys. As variation in patient experience scores across organizations is known to be very small23, 53, 54 and the variation across providers within an organization can be even smaller, the effect size observed here can be considered meaningful. Although the trends were in the same direction, the effects on access and the overall rating of the physician, after controlling for PCP workload, were not significant. Effective patient-provider communication requires time and effort and may be the first domain to suffer when physicians experience burnout.

It is notable that PCPs who were female and had fewer years of experience were more likely to be burned out, but these characteristics were not negatively associated with patient experience. Rather, for the provider communication domain, female physicians scored higher. Consistently, previous studies found that female physicians engaged in more patient-centered communication and that they scored higher in patient experiences despite lower access.55, 56 Further understanding of the components of burnout (depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and personal accomplishment57) by gender would shed light on gender differences in the relationship between burnout and patient experience. A wider research literature has demonstrated the gender differences in physician burnout in many samples, with women and mothers consistently reporting work stress and even discrimination.58–60 The increasingly female PCP workforce in the US and differences in clinical practice by gender indicate a need for careful exploration of this concern.

On the other hand, adjusted panel size and clinical FTE were not consistently associated with burnout nor patient experience of care. One possible explanation is that PCPs with a large panel or FTE may do well if they have adequate staff support which can have protective effect on physician burnout and patient experience.61 Thus, panel size and clinical FTE may not be the best indicators of workload, in the absence of other contributors that were not available for the study, such as having inadequate support staff in clinics (e.g., too few medical assistants) or high volumes of electronic messages from patients and staff. Such indicators of staff support and EHR workload are also known predictors of burnout and patient experience.3, 61 It might also be the case that physicians with low clinical FTE may have other responsibilities and higher administrative workload.

This is the first large-scale empirical study of burnout and patient experience among American PCPs in the US. Consistent with our findings, some previous studies reported negative relationships, among PCPs in Greece14 and the Netherlands.15 Another related study conducted in the US in 2002 found no relationship between physician burnout and effectiveness of patient-provider communication rated by researcher’s observation, rather than patient self-report,62 but limited sample size (n = 40 PCPs and 235 patients with hypertension) may have contributed to the lack of statistical significance, and changes in medicine and the widespread introduction of EHR systems since this research was conducted also warrant more attention to this topic.

Several limitations of this study should be considered in the interpretation and generalization of our findings. First, we used a validated, single-item measure of burnout to keep the survey short and maximize the response rate. A longer survey using the MBI would have enabled a more thorough assessment of which dimensions of burnout are associated with particular patient experience domains. Second, while the survey response rate was high, at 72%, it is still possible that respondents are systematically different from non-respondents in unobservable ways. To minimize potential bias, we employed structural equation models with an instrumental variable approach to identify direct relationships between burnout and patient experience, unaffected by unobserved confounders. Third, with low response rates, patient experience survey responses may be biased in unknown directions. Patient experience surveys are also known to have ceiling effects, thereby not being sensitive to capture differences in quality. These issues might have been mitigated in this study by using the data aggregated at the provider level. Finally, our study participants came from a large medical group. Recent research indicates that burnout may be lower in small private practices and there may be different mediating factors in that environment,63 and thus, our findings may not generalize to all practice settings.

In conclusion, primary care physician burnout has a direct negative impact on patient experience of care especially in the domain of patient-provider communication. Department climate and degree of physician autonomy in scheduling are important contributors of burnout, while panel size and work hours are not associated with burnout or patient experience. Efforts to improve the work environment to address physician well-being would be beneficial not only for physicians but also for patient experience.

Electronic Supplementary Material

(DOCX 16 kb).

Acknowledgments

We thank the study team who contributed to the conception and execution of physician joy of work surveys and to the data preparation for this study including Ruth Steinberg, Teresa Nauenberg, Tim C Lee, Ming Tai-Seale, and Yan Yang.

Funding Information

The study was funded internally by the Palo Alto Medical Foundation, Sutter Health.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

The Sutter Health Institutional Review Board approved the study protocol.

Conflict of Interest

The authors are employees of the healthcare system where the surveys were conducted and data were collected. The organization had no influence in the conduct or reporting of this study.

Disclaimer

The organization was not involved in the analysis and interpretation of the data.

Footnotes

All the analytical work and manuscript writing was completed during Dr. Chung’s employment at Sutter Health.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–13. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL, Jr, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503–9. doi: 10.1370/afm.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tai-Seale M, Dillon EC, Yang Y, Nordgren R, Steinberg RL, Nauenberg T, et al. Physicians’ Well-Being Linked To In-Basket Messages Generated By Algorithms In Electronic Health Records. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(7):1073–8. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tai-Seale M, Olson CW, Li J, Chan AS, Morikawa C, Durbin M, et al. Electronic Health Record Logs Indicate That Physicians Split Time Evenly Between Seeing Patients And Desktop Medicine. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(4):655–62. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, Temte JL, Tuan WJ, Sinsky CA, et al. Tethered to the EHR: Primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(5):419–26. doi: 10.1370/afm.2121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, Montague E, Williams E, Schwartz M, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100–6. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wallace JE, Lemaire JB, Ghali WA. Physician wellness: a missing quality indicator. Lancet. 2009;374(9702):1714–21. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61424-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hall LH, Johnson J, Watt I, Tsipa A, O’Connor DB. Healthcare Staff Wellbeing, Burnout, and Patient Safety: A Systematic Review. PLoS One. 2016;11(7):e0159015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0159015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Panagioti M, Geraghty K, Johnson J, Zhou A, Panagopoulou E, Chew-Graham C, et al. Association Between Physician Burnout and Patient Safety, Professionalism, and Patient Satisfaction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178(10):1317–30. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.3713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 10.Dewa CS, Loong D, Bonato S, Trojanowski L. The relationship between physician burnout and quality of healthcare in terms of safety and acceptability: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(6):e015141. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halbesleben JR, Rathert C. Linking physician burnout and patient outcomes: exploring the dyadic relationship between physicians and patients. Health Care Manage Rev. 2008;33(1):29–39. doi: 10.1097/01.HMR.0000304493.87898.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sikka R, Morath JM, Leape L. The Quadruple Aim: care, health, cost and meaning in work. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(10):608–10. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2015-004160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573–6. doi: 10.1370/afm.1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Anagnostopoulos F, Liolios E, Persefonis G, Slater J, Kafetsios K, Niakas D. Physician burnout and patient satisfaction with consultation in primary health care settings: evidence of relationships from a one-with-many design. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2012;19(4):401–10. doi: 10.1007/s10880-011-9278-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van den Hombergh P, Künzi B, Elwyn G, van Doremalen J, Akkermans R, Grol R, et al. High workload and job stress are associated with lower practice performance in general practice: an observational study in 239 general practices in the Netherlands. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:118. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Szecsenyi J, Goetz K, Campbell S, Broge B, Reuschenbach B, Wensing M. Is the job satisfaction of primary care team members associated with patient satisfaction? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):508–14. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2009.038166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee S, Rodriguez HP, Elliott MN, Crane PK. Modern psychometric methods for estimating physician performance on the Clinician and Group CAHPS® survey. Health Serv Outcome Res Methodol. 2013;13(2–4):109–23. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dyer N, Sorra JS, Smith SA, Cleary PD, Hays RD. Psychometric properties of the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS(R)) Clinician and Group Adult Visit Survey. Med Care. 2012;50(Suppl):S28–34. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31826cbc0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rodriguez HP, Crane PK. Examining multiple sources of differential item functioning on the Clinician & Group CAHPS(R) survey. Health Serv Res. 2011;46(6pt1):1778–802. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01299.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Changes for Calendar Year 2014 Physician Quality Programs and the Value-Based Payment Modifier. CMS.gov. 2013.

- 21.Elliott MN, Zaslavsky AM, Goldstein E, Lehrman W, Hambarsoomians K, Beckett MK, et al. Effects of Survey Mode, Patient Mix, and Nonresponse on CAHPS® Hospital Survey Scores. Health Serv Res. 2009;44(2 Pt 1):501–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2008.00914.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groves RM, Peytcheva E. The Impact of Nonresponse Rates on Nonresponse Bias: A Meta-Analysis. Public Opin Q. 2008;72(2):167–89. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chung S, Mujal G, Liang L, Palaniappan LP, Frosch DL. Racial/ethnic differences in reporting versus rating of healthcare experiences. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97(50):e13604. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Elliott MN, Edwards C, Angeles J, Hambarsoomians K, Hays RD. Patterns of Unit and Item Nonresponse in the CAHPS® Hospital Survey. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(6 Pt 2):2096–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zaslavsky AM, Zaborski LB, Cleary PD. Factors affecting response rates to the Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study survey. Med Care. 2002;40(6):485–99. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200206000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tyser AR, Abtahi AM, McFadden M, Presson AP. Evidence of non-response bias in the Press-Ganey patient satisfaction survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16(a):350. doi: 10.1186/s12913-016-1595-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boscardin CK, Gonzales R. The impact of demographic characteristics on nonresponse in an ambulatory patient satisfaction survey. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2013;39(3):123–8. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(13)39018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chung S, Johns N, Zhao B, Romanelli R, Pu J, Palaniappan LP, et al. Clocks Moving at Different Speeds: Cultural Variation in the Satisfaction With Wait Time for Outpatient Care. Med Care. 2016;54(3):269–76. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tesler R, Sorra J. CAHPS Survey Administration: What We Know and Potential Research Questions. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rohland B, Kruse G, Rohrer J. Validation of a single item measure of burnout against the Maslach Burnout Inventory among physicians. Stress Health. 2004;20(2):75–9. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolan ED, Mohr D, Lempa M, Joos S, Fihn SD, Nelson KM, et al. Using a single item to measure burnout in primary care staff: a psychometric evaluation. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(5):582–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3112-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Trockel M, Bohman B, Lesure E, Hamidi MS, Welle D, Roberts L, et al. A brief instrument to assess both burnout and professional fulfillment in physicians: reliability and validity, including correlation with self-reported medical errors, in a sample of resident and practicing physicians. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;42:11–24. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0849-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hansen V, Pit S. The Single Item Burnout Measure is a Psychometrically Sound Screening Tool for Occupational Burnout. Health Scope. 2016.

- 34.Knox M, Willard-Grace R, Huang B, Grumbach K. Maslach Burnout Inventory and a self-defined, single-item burnout measure produce different clinician and staff burnout estimates. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(8):1344–51. doi: 10.1007/s11606-018-4507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rabatin J, Williams E, Baier Manwell L, Schwartz MD, Brown RL, Linzer M. Predictors and Outcomes of Burnout in Primary Care Physicians. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):41–3. doi: 10.1177/2150131915607799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Swensen S, Kabcenell A, Shanafelt T. Physician-Organization Collaboration Reduces Physician Burnout and Promotes Engagement: The Mayo Clinic Experience. J Healthc Manag. 2016;61(2):105–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272–81. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Awa WL, Plaumann M, Walter U. Burnout prevention: a review of intervention programs. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78(2):184–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Linzer M, Manwell L, Williams E, Bobula J, Brown R, Varkey A, et al. Working conditions in primary care: physician reactions and care quality. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2009;151(1):28. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-1-200907070-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Linzer M, Baier Manwell L, Mundt M, Williams E, Maguire A, McMurray J, et al. Advances in Patient Safety Organizational Climate, Stress, and Error in Primary Care: The MEMO Study. In: Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, Lewin DI, et al., editors. Advances in Patient Safety: From Research to Implementation (Volume 1: Research Findings) Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hakanen JJ, Schaufeli WB. Do burnout and work engagement predict depressive symptoms and life satisfaction? A three-wave seven-year prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2012;141(2–3):415–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB. A model of burnout and life satisfaction amongst nurses. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(2):454–64. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01496.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Henriksen K, Battles JB, Marks ES, Lewin DI, Linzer M, Manwell LB, et al. Organizational climate, stress, and error in primary care: the MEMO study. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality: Rockville, MD; 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linzer M, Poplau S, Grossman E, Varkey A, Yale S, Williams E, et al. A Cluster Randomized Trial of Interventions to Improve Work Conditions and Clinician Burnout in Primary Care: Results from the Healthy Work Place (HWP) Study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(8):1105–11. doi: 10.1007/s11606-015-3235-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mochon D, Norton MI, Ariely D. Getting off the hedonic treadmill, one step at a time: The impact of regular religious practice and exercise on well-being. J Econ Psychol. 2008;29(5):632–42. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Weight CJ, Sellon JL, Lessard-Anderson CR, Shanafelt TD, Olsen KD, Laskowski ER. Physical activity, quality of life, and burnout among physician trainees: the effect of a team-based, incentivized exercise program. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013:1435–42. Elsevier. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med. 2006;81(1):82–5. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200601000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, et al. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. Jama. 2009;302(12):1284–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goldberger AS. Structural Equation Methods in the Social Sciences. Econometrica. 1972;40(6):979–1001. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newhouse JP, McClellan M. Econometrics in outcomes research: the use of instrumental variables. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:17–34. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hoyle RH. Handbook of structural equation modeling: Guilford press: 2012.

- 52.Kenny DA. Estimation with instrumental variables.

- 53.Wood R, Paoli CJ, Hays RD, Taylor-Stokes G, Piercy J, Gitlin M. Evaluation of the consumer assessment of healthcare providers and systems in-center hemodialysis survey. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(6):1099–108. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10121013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glickman SW, Schulman KA. The mis-measure of physician performance. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(10):782–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Roter DL, Hall JA. Physician gender and patient-centered communication: a critical review of empirical research. Annu Rev Public Health. 2004;25:497–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.25.101802.123134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Panattoni L, Stone A, Chung S, Tai-Seale M. Patients report better satisfaction with part-time primary care physicians, despite less continuity of care and access. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3):327–33. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-3104-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maslach C, Jackson S. The Measurement of Experienced Burnout. J Org Behav. 1981;2:99–113. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Halley MC, Rustagi AS, Torres JS, Linos E, Plaut V, Mangurian C, et al. Physician mothers’ experience of workplace discrimination: a qualitative analysis. Bmj. 2018;363:k4926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, Nora LM, Newman C, Burstin H, et al. Gender-Based Differences in Burnout: Issues Faced by Women Physicians. NAM Perspectives. 2019.

- 60.Hedden L, Barer ML, Cardiff K, McGrail KM, Law MR, Bourgeault IL. The implications of the feminization of the primary care physician workforce on service supply: a systematic review. Hum Resour Health. 2014;12:32. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Helfrich CD, Simonetti JA, Clinton WL, Wood GB, Taylor L, Schectman G, et al. The association of team-specific workload and staffing with odds of burnout among VA primary care team members. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(7):760–6. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4011-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ratanawongsa N, Roter D, Beach MC, Laird SL, Larson SM, Carson KA, et al. Physician burnout and patient-physician communication during primary care encounters. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(10):1581–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0702-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Blechter B, Jiang N, Cleland C, Berry C, Ogedegbe O, Shelley D. Correlates of burnout in small independent primary care practices in an urban setting. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(4):529–36. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2018.04.170360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX 16 kb).