Abstract

Escherichia coli carrying prophage with genes that encode for Shiga toxins are categorized as Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) pathotype. Illnesses caused by STEC in humans, which are often foodborne, range from mild to bloody diarrhea with life-threatening complications of renal failure and hemolytic uremic syndrome and even death, particularly in children. As many as 158 of the total 187 serogroups of E. coli are known to carry Shiga toxin genes, which makes STEC a major pathotype of E. coli. Seven STEC serogroups, called top-7, which include O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157, are responsible for the majority of the STEC-associated human illnesses. The STEC serogroups, other than the top-7, called “non-top-7” have also been associated with human illnesses, more often as sporadic infections. Ruminants, particularly cattle, are principal reservoirs of STEC and harbor the organisms in the hindgut and shed in the feces, which serves as a major source of food and water contaminations. A number of studies have reported on the fecal prevalence of top-7 STEC in cattle feces. However, there is paucity of data on the prevalence of non-top-7 STEC serogroups in cattle feces, generally because of lack of validated detection methods. The objective of our study was to develop and validate 14 sets of multiplex PCR (mPCR) assays targeting serogroup-specific genes to detect 137 non-top-7 STEC serogroups previously reported to be present in cattle feces. Each assay included 7–12 serogroups and primers were designed to amplify the target genes with distinct amplicon sizes for each serogroup that can be readily identified within each assay. The assays were validated with 460 strains of known serogroups. The multiplex PCR assays designed in our study can be readily adapted by most laboratories for rapid identification of strains belonging to the non-top-7 STEC serogroups associated with cattle.

Keywords: shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC), top-7 STEC, non-top-7 STEC, Multiplex PCR assays, cattle, feces

Introduction

The polysaccharide portion, called the O-antigen, of the lipopolysaccharide layer of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli provides antigenic specificity and is the basis of serogrouping. As many as 187 E. coli serogroups have been described based on the nucleotide sequences of O-antigen gene clusters (DebRoy et al., 2016). Escherichia coli serogroups that cause disease in humans and animals are categorized into several pathotypes. The serogroups that carry Shiga toxin genes on a prophage are categorized as the Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (STEC) pathotype. As many as 158 serogroups of E. coli are known to carry Shiga toxin gene(s), which make STEC the most predominant E. coli pathotype (Table 1). Illnesses caused by STEC in humans, which are often foodborne, range from mild to bloody diarrhea with life-threatening complications of renal failure and hemolytic uremic syndrome (HUS), and even death, particularly in children (Karmali et al., 2010; Davis et al., 2014). Seven serogroups of STEC, O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157, called “top-7,” are responsible for the majority of human STEC illnesses, including food borne-outbreaks (Brooks et al., 2005; Scallan et al., 2011; Gould et al., 2013; Valilis et al., 2018). However, STEC serogroups other than the top-7, called “non-top-7” have also been reported to cause human illnesses, more often as sporadic infections, although a few are also known to cause severe infections, such as hemorrhagic colitis and HUS (Hussein and Bollinger, 2005; Bettelheim, 2007; Hussein, 2007; Bettelheim and Goldwater, 2014; Valilis et al., 2018). In a recent systematic review done by Valilis et al. (2018), 129 O-serogroups of STEC were identified to be associated with clinical cases of diarrhea in humans.

Table 1.

Serogroups that belong to the Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli pathotype.

| O1 | O2/O50 | O3 | O4 | O5 | O6 | O7 | O8 | O9 | O10 |

| O11/OX19 | O12 | O13/O129/O135 | O14 | O15 | O16 | O17/O44/O73/O77/O106 | O18ab/O18ac | O19 | O20/O137 |

| O21 | O22 | O23 | O25 | O26a | O27 | O28ac/O42 | O29 | O30 | O32 |

| O33 | O35 | O36b | O37 | O38 | O39 | O40 | O41 | O43 | O45a |

| O46/O134 | O48 | O49 | O51 | O52 | O53 | O54 | O55 | O56 | O57 |

| O58 | O59 | O60 | O62/O68 | O63 | O64 | O65 | O66b | O69 | O70 |

| O71 | O74 | O75 | O76 | O78 | O79 | O80 | O81 | O82 | O83 |

| O84 | O85 | O86 | O87 | O88 | O89/O101/O162 | O90/O127 | O91 | O92 | O93 |

| O95b | O96 | O97 | O98 | O100 | O102 | O103a | O104 | O105 | O107/O117 |

| O108 | O109 | O110 | O111a | O112 | O113 | O114 | O115 | O116 | O118/O151 |

| O119 | O120 | O121a | O123/O186 | O124/O164 | O125 | O126 | O128/OX3 | O130 | O131 |

| O132 | O133 | O136 | O138 | O139 | O140 | O141 | O142 | O143 | O144 |

| O145a | O146 | O147 | O148 | O149 | O150 | O152 | O153 | O154 | O156 |

| O157a | O158 | O159 | O160 | O161 | O163 | O165 | O166 | O167 | O168/OX6 |

| O169 | O170 | O171 | O172 | O173 | O174 | O175 | O176 | O177 | O178 |

| O179 | O180 | O181 | O182 | O183 | O184b | O185 | O187b |

Serogroups (highlighted in blue color) considered as top-7 STEC.

Serogroups (highlighted in green color) have not yet been reported in cattle feces, beef, or beef products.

Ruminants, especially cattle, are a major reservoir of STEC and harbor the organisms in the hindgut and shed them in their feces. A number of studies have reported on the fecal prevalence of the top-7 STEC in cattle because of the availability of detection methods. For these serogroups, culture method involving serogroup-specific immunomagnetic separation and media for selective isolation and PCR assays to identify serogroups of putative isolates have been developed, validated and widely used (Bielaszewska and Karch, 2000; Chapman, 2000; Bettelheim and Beutin, 2003; Noll et al., 2015a). A number of studies have reported shedding of non-top-7 STEC in cattle feces (Table 2). However, not much is known about the prevalence of these STEC serogroups in cattle feces, in terms of their distribution and proportion of animals in a herd positive for various serogroups, largely because of lack of isolation and detection methods. Traditionally, identification of serogroups or serotyping of E. coli, conducted by agglutination reaction using serogroup-specific antisera, is restricted to a few reference laboratories that possess the required antisera. However, the method is time consuming and often exhibits cross-reactions with other serogroups (DebRoy et al., 2011a). A number of PCR-based assays, end point or real time, have been developed and validated for the detection of one or more clinically relevant serogroups of E. coli (Perelle et al., 2004; Monday et al., 2007; Fratamico et al., 2009; Bai et al., 2010, 2012; DebRoy et al., 2011b; Madic et al., 2011; Luedtke et al., 2014; Iguchi et al., 2015b; Noll et al., 2015b; Sanchez et al., 2015; Shridhar et al., 2016a). However, only a few mPCR assays have been described to detect certain STEC serogroups that are non-top-7 (Iguchi et al., 2015b; Sanchez et al., 2015; DebRoy et al., 2018).

Table 2.

Serogroups of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli other than the top-7 in gut contents or feces of cattle.

| Cattle type | Sample type | O-serogroups reported | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Calves with diarrhea or dysentery | Feces | O2, O5, O8, O29, O55, O149, O153 | (Smith et al., 1988) |

| Calves | Feces | O2, O104, O128, O153 | (Gonzalez and Blanco, 1989) |

| Bulls and dairy cows | Colonic contents of bulls at slaughter, rectal content of dairy cows | O3, O10, O22, O39, O75, O82, O91, O104, O105, O113, O116, O126, O136, O139, O156 | (Montenegro et al., 1990) |

| Beef and dairy cattle, water buffalo | Rectal swab | O11, O25, O113, O116 | (Suthienkul et al., 1990) |

| Dairy cattle: cows, heifers, calves; feedlot cattle | Rectal swab | O10, O15, O22, O76, O84, O116, O153, O163, O171 | (Wells et al., 1991) |

| Dairy cows and calves | Fecal swab | O2, O3,O 4, O6, O8, O9, O11, O15, O22, O25, O32, O40, O43, O82, O87, O106, O109, O113, O117, O146, O153, O163, X3, X8 | (Wilson et al., 1992) |

| Cattle | Rectal swab | O2, O8, O20, O22, O76, O82, O87, O88, O113, O146, O152, O156 | (Beutin et al., 1993) |

| Cattle | Culture from cattle | O8, O9, O11, O15, O17, O20, O78, O86, O101 | (Wray et al., 1993) |

| Dairy cows and calves | Rectal swab | O5, O18, O49, O69, O74, O76, O80, O84, O98, O118, O119, O156, O172 | (Sandhu et al., 1996) |

| Calves, diarrheic | Feces | O4, O5, O15, O17, O53, O80, O84, O92, O118, O119, O128, O153 | (Wieler et al., 1996) |

| Cattle | Feces | O74, O87, O90, O91, O116 | (Beutin et al., 1997) |

| Cows and calves | Fecal swab | O2, O4, O8, O9, O20, O22, O41, O74, O77, O78, O82, O90, O91, O92, O105, O113, O116, O132, O136, O146, O150, O162, O163, O165, O171 | (Blanco et al., 1997) |

| Calves with diarrhea | Feces | O6, O8, O25, O52, O86, O113, O167, ONT | (Beutin and Muller, 1998) |

| Cattle | Feces or rectal contents | O2, O16, O22, O42, O70, O74, O84, O87, O105, O109, O113, O132, O136, O146, O153, O156 | (Miyao et al., 1998) |

| Calves, healthy and diarrheic | Feces | O118 | (Wieler et al., 1998) |

| Dairy cows and calves | Fecal swabs | O5, O8, O22, 38, O69, O84, O98, O113, O116, O119, O132, O153, O156 | (Sandhu et al., 1999) |

| Dairy cow with diarrhea and calves with a herd history of ill-thrift and diarrhea | Feces | O84 | (Hornitzky et al., 2000) |

| Beef and dairy cattle: healthy and diarrheic calves; Cattle at slaughter; Grazing cows | Rectal swab | O2, O5, O20, O38, O39, O74, O79, O91, O113, O116, O117, O118, O141, O165, O168, O171 | (Parma et al., 2000) |

| Cattle at slaughter | Feces | OX3, O1, O2, O6, O8, O15, O20, O22, O23, O39, O40, O46, O49, O74, O77, O84, O87, O88, O91, O96, O98, O102, O105, O106, O109, O112, O113, O116, O117, O120, O130, O132, O136, O140, O141, O150, O159, O163, O171, O172, OX177, OX7, OX178 | (Pradel et al., 2000) |

| Cattle at slaughter | Rectal swab | O2, O8, O22, O43, O91, O110, O113, O116, O119, O132, O136, O153, O172 | (Schurman et al., 2000) |

| Dairy cows and calves | Feces | O12, O35, O98, O165 | (Cobbold and Desmarchelier, 2001) |

| Cattle | Feces | O5, O6, O7, O21, O28, O91, O113, O130, ONT | (Hornitzky et al., 2001) |

| Cattle at slaughter | Rectal swab | O15, O84, O91, O172 | (Leung et al., 2001) |

| Beef and dairy cattle | Rectal swab | O20, O22, O74, O79, O84, O110, O112, O119, O125, O126, O128, O149, O156, O159, O165, O172, ONT | (Geue et al., 2002) |

| Beef cattle at slaughter | Fecal from cecum | O2, O8, O11, O116 | (Gioffré et al., 2002) |

| Beef and feedlot cattle | Feces | O2, O3, O5, O6, O8, O28, O51, O68, O75, O76, O77, O81, O82, O84, O91, O93, O101, O104, O108, O110, O113, O116, O130, O149, O153, O154, O160, O163, ONT | (Hornitzky et al., 2002) |

| Beef or dairy cattle, calves | Feces (diagnostic samples, gastrointestinal infections) | O2, O5, O7, O8, O15, O22, O28, O41, O53, O71, O74, O75, O81, O84, O88, O98, O112, O113, O118, O119, O123, O130, O146, O159, O163, O174, O175, O177, O178, O179, O181 | (Hornitzky et al., 2005) |

| Dairy cows, heifers, calves | Rectal swab | O29, O91, O112, O119, O125 | (Moreira et al., 2003) |

| Cattle | Fecal swab | O22, O91, O113, O117, OX179 | (Urdahl et al., 2003) |

| Calves | Feces | O7, O22, O113, O118, O119, O123 | (Leomil et al., 2003) |

| Cattle, diarrheic and healthy | Feces | O2, O4, O6, O7, O8, O9, O15, O17, O20, O22, O28, O38, O39, O41, O49, O60, O64, O65, O74, O77, O79, O80, O81, O82, O84, O88, O90, O91, O96, O104, O105, O110, O113, O116, O117, O118, O123, O126, O127, O128, O132, O136, O138, O140, O141, O146, O148, O149, O150, O156, O162, O163, O165, O166, O167, O168, O171, O174, OX177, OX178, ONT | (Blanco et al., 2004a) |

| Cattle, grazing or feedlot | Feces | O2, O5, O8, O15, O20, O25, O38, O39, O74, O79, O91, O113, O116, O117, O118, O120, O141, O165, O168, O171, O174, O175, O177, O178, O185, ONT | (Blanco et al., 2004b) |

| Cattle at slaughter | Cecal content | O74, O91, O109, O110, O116, O117 | (Bonardi et al., 2004) |

| Cattle at slaughter | Cecal content | O2, O8, O11, O25, O91, O104, O112, O113, O143, O171, O174, ONT | (Meichtri et al., 2004) |

| Cows and calves | Feces | O2, O8, O77, O113, O116, O136, O171, O177 | (Muniesa et al., 2004) |

| Cattle at slaughter | Feces | O2, O5, O8, O10, O15, O35, O64, O77, O113, O119, O128, O156, O177, ONT | (Blanco et al., 2005) |

| Dairy cows, heifers, calves, some diarrheic | Rectal swab | O22, O44, O77, O79, O87, O88, O91, O98, O105, O112, O113, O136, O178, O181, ONT | (Irino et al., 2005) |

| Cattle | Feces | O2, O4, O8, O20, O22, O41, O64, O77, O82, O91, O105, O113, O116, O117, O118, O126, O128, O136, O141, O146, O150, O156, O162, O163, O168, O171, O174, O177, ONT | (Mora et al., 2005) |

| Cattle at slaughter | Feces | O1, O2, O5, O8, O15, O22, O86, O91, O113, O116, O117, O136, O148, O174, O182, ONT | (Zweifel et al., 2005) |

| Beef and dairy cattle | Feces | O2, O10, O15, O22, O74, O82, O96, O113, O116, O119, O124, O128, O137, O141, O159, O160, O63, O174, O177, O178, ONT | (Timm et al., 2007) |

| Steers, feedlot | Feces | O2, O8, O9, O10, O23, O37, O49, O87, O98, O132, O135, O136, O139, O153, O154, O156, O172 | (Diarra et al., 2009) |

| Cattle | Feces | O2, O63, O148, O149, O174, ONT | (Scott et al., 2009) |

| Dairy cows | Feces | O2, O3, O5, O8, O11, O22, O39, O46, O64, O74, O79, O84, O88, O91, O105, O113, O130, O136, O139, O141, O163, O166, O168, O171, O1788, O179, ONT | (Fernández et al., 2010) |

| Beef cattle | Feces | O2, O7, O8, O15, O22, O39, O46, O73, O74, O79, O82, O91, O113, O116, O130, O136, O139, O141, O153, O163, O165, O178, O179, ONT | (Masana et al., 2011) |

| Cattle, beef and dairy | Pen-floor feces | O2, O13, O20, O86, O109, O113, O116, O119, O136, O168, O171, O174, ONT | (Monaghan et al., 2011) |

| Cattle, beef and dairy | Feces | O2, O3, O33, O69, O76, O88, O113, O118, O136, O150, O153, O171, OR, OX18 | (Ennis et al., 2012) |

| Calves | Rectal swabs | O8, O11, O15, O91, O101, O171, ONT | (Fernández et al., 2012) |

| Dairy cows | Feces | O8, O21, O116, O118, O141, O153, NT | (Polifroni et al., 2012) |

| Beef Cattle | Rectal swabs | O2, O7, O8, O15, O22, O79, O84, O91, O107, O124, O130, O136, O141, O163, O174, O179, ONT | (Tanaro et al., 2012) |

| Cattle | Feces | O1, O2, O5, O8, O55, O84, O91, O109, O113, O136, O150, O156, O163, O168, O174, 177, UT | (Mekata et al., 2014) |

| Feedlot heifer | Colonic mucosal tissue at necropsy | O165 | (Moxley et al., 2015) |

| Dairy Cattle | Feces | O2, O8, O10, O15, O20, O22, O39, O46, O55, O74, O77, O79, O82, O89, O91, O105, O113, O116, O141, O171, O172, O153, O165 | (Gonzalez et al., 2016) |

| Cattle | Feces | O113, NT | (Jajarmi et al., 2017) |

| Cattle | Feces | O2, O3, O6, O8, O22, O28ac, O55, O71, O74, O76, O82, O87, O88, O96, O100, O104, O108, O109, O113, O115, O116, O123, O130, O132, O136, O140, O150, O153, O156, O163, O168, O171, O174, O178, O179, O183, O185 | (Lee et al., 2017) |

| Steers | Recto anal mucosal swab | O101, O109, O177 | (Stromberg et al., 2018) |

| Beef cattle | Feces | O178 | (Paquette et al., 2018) |

| Dairy cattle | Feces | O3, O8, O18ac, O39, O48, O58, O77, O80, O88, O104, O112ac, O116, O146, O154, O174, O175, O176, O178, O179, O180 | (Navarro et al., 2018) |

| Dairy cattle | Feces | O21, O22, O54, O55, O64, O69, O75, O78, O91, O92, O97, O100, O149, O173 | (Peng et al., 2019) |

| Beef cattle | Feces | O5, O8, O15, O22, O65, O74, O76, O81, O84, O96, O116, O165, O166, O177, ONT | (Fan et al., 2019) |

| Beef and dairy cattle | Feces | O17, O22, O40, O76, O87, O99, O102, O108, O116, O124, O129, O136, O140, O154, O156, O163 | (Bumunang et al., 2019) |

ONT, Non typeable O; UT, Untypeable; NT, nontypeable.

In recent years, DNA microarray and whole genome sequencing have been widely used to identify E. coli serogroups and serotypes (Liu and Fratamico, 2006; Lacher et al., 2014; Joensen et al., 2015; Norman et al., 2015). However, mPCR assays targeting serogroup-specific genes to identify STEC is a simpler, low-cost alternative method, readily adaptable to most laboratories. Iguchi et al. (2015a) and DebRoy et al. (2016) have analyzed the nucleotide sequences of O-antigen gene clusters of 184 serogroups of E. coli and reported remarkable diversity among different serogroups and a high level of conservation of genes within a given serogroup in the O-antigen encoding gene clusters and suggested that these gene sequences can be targeted for serogroup identification. To understand the ecology and prevalence of these STEC serogroups in cattle, it is essential to detect the non-top-7 STEC serogroups shed in cattle feces in order to determine their impact on food safety and human health. Therefore, the objectives of the present study were to develop and validate mPCR assays targeting serogroup-specific genes to detect 137 non-top-7 STEC serogroups known to be associated with cattle.

Materials and Methods

Design of the Assays

A total of 14 mPCR assays, each targeting 7–12 STEC serogroups were designed. The targeted genes to design primers for serogroup detection included: wzx, which encodes for the O-antigen flippase required for O-polysaccharide export (Liu et al., 1996), wzy, which encodes for the O-antigen polymerase required for O antigen biosynthesis (Samuel and Reeves, 2003), gnd, which encodes for 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase for O antigen biosynthesis (Nasoff et al., 1984), wzm, which encodes for transport permease for O antigen transport, and orf469 and wbdC, which encode for mannosyltransferase for O antigen biosynthesis (Kido et al., 1995). The primers were designed based on the available nucleotide sequences of the target genes for each of the STEC serogroups from the GenBank database. The sequences for each serogroup were aligned using ClustalX version 2.0. The primers were designed to amplify the target genes with distinct amplicon sizes for each serogroup within an assay for easier visualization. The forward and reverse primer sequences for these serogroups are provided in Supplementary Tables 1A–N.

PCR Assay Conditions

The working concentrations of all primers in a primer mix were 4–7 pM/μl of each primer. The reaction consisted of 1 μL of primer mix, 10 μL of BioRad iQ Multiplex Powermix, 7 μL of sterile PCR grade water, and 2 μL of DNA template. The total reaction volume was 20 μL. The number of PCR cycles and annealing temperatures varied based on optimization for each set (Table 3). The PCR protocol for specific gene target, for sets no. 1–11, included an initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 min, followed by 25 or 30 cycles of denaturation at 94° C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s at 58–68°C, extension for 75 s at 68°C and a final step of extension at 68° C for 7 min. The assay conditions for PCR sets no. 12, 13, and 14 were initial denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, followed by 25 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing for 30 s at 58–63°C, extension for 60–80 s at 72°C and final step of extension at 72°C (Table 3). All the other conditions were similar for all 14 sets of assays. Amplicon size of PCR products was determined using a capillary electrophoresis system, QIAxcel Advanced System with QIAxcel DNA Screening Kit (Qiagen, Germantown, MD). DNA extracted from pooled strains of known serogroups for each specific set was used as positive controls and size markers for each set of assay.

Table 3.

Multiplex PCR assays running conditions for the detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) serogroups, other than top-7 serogroups.

| Assays | Number of O groups | PCR cycles | Annealing temperature (°C) | O-serogroups (amplicon size in bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set-1 | 8 | 25 | 65 | O109 (204), O91 (277), O168 (336), O80 (406), O156 (452), O84 (501), O86 (562), O4 (832) |

| Set-2 | 10 | 30 | 65 | O5 (176), O22 (246), O171 (281), O175 (343), O13/O129/O135 (364), O119 (421), O120 (535), O123/O186 (619), O138 (696), O128 (768) |

| Set-3 | 9 | 30 | 64 | O25 (230), O79 (266), O150 (313), O116 (355), O33 (413), O75 (511), O181 (595), O98 (675), O6 (783) |

| Set-4 | 10 | 30 | 63 | O147 (230), O15 (288), O118/O151 (344), O113 (419), O126 (465), O178 (495), O76 (533), O146 (640), O2/O50 (819), O78 (992) |

| Set-5 | 9 | 30 | 61 | O20 (204), O55 (262), O87 (306), O92 (375), O8 (448), O136 (528), O163 (596), O7 (753), O62/O68 (906) |

| Set-6 | 12 | 30 | 66 | O115 (158), O39 (201), O38 (253), O74 (303), O107/O117 (357), O88 (394), O96 (457), O108 (515), O130 (567), O132 (652), O153 (741), O141 (880) |

| Set-7 | 12 | 30 | 63 | O1 (152), O18ab/O18ac (199), O28 (O28ac/O42; 255), O35 (305), O37 (353), O40 (396), O43 (445), O17/O44/O73/O77/ O106 (500), O51 (566), O69 (649), O53 (735), O70 (863) |

| Set-8 | 11 | 25 | 68 | O140 (155), O148 (201), O81 (248), O82 (301), O85 (353), O105 (407), O102 (453), O90/O127 (498), O124/O164 (570), O125ab/O125ac (652), O139 (859) |

| Set-9 | 9 | 25 | 63 | O21 (145), O49 (197), O149 (253), O93 (299), O110 (346), O114 (396), O154 (499), O161 (646), O169 (865) |

| Set-10 | 12 | 25 | 59 | O152 (150), O159 (202), O170 (233), O172 (278), O174 (317), O176 (356), O177 (395), O46/O134 (455), O179 (505), O182 (566), O160 (655), O165 (735) |

| Set-11 | 11 | 30 | 62 | O3 (145), O10 (187), O11 (225), O112ab (270), O101/O162 (309), O29 (348), O23 (403), O63 (455), O16 (505), O19 (574), O131 (655) |

| Set-12 | 9 | 25 | 63 | O56 (250), O9 (309), O54 (351), O27 (382), O60 (443), O143 (500), O142 (538), O48 (793), O41 (942) |

| Set-13 | 7 | 25 | 58 | O133 (294), O83 (362), O167 (403), O166 (462), O64 (727), O12 (885), O58 (1046) |

| Set-14 | 8 | 25 | 58 | O100 (193), O144 (245), O66 (301), O71 (344), O65 (381), O32 (452), O173 (606), O180 (744) |

Validation of PCR assays

The specificity of each assay was determined with pooled DNA of the positive controls from the other 13 sets and top-7 STEC plus O104 PCR assays. Additionally, each assay was validated with one or more strains of the targeted serogroups. A total of 460 STEC strains belonging to 137 targeted serogroups were used for the validation of the assays (Table 4; Supplementary Tables 2A–N). The strains were obtained from our culture collection (n = 104), E. coli Reference Center at Pennsylvania State University (n = 223), Michigan State University (n = 42), University of Nebraska (n = 5), and Food and Drug Administration (n = 86). Strains stored in CryoCare beads (CryoCare, Key Scientific Products, Round Rock, TX) at −80°C were streaked onto blood agar plates (Remel, Lenexa, KS) and incubated overnight at 37°C. Following incubation, colonies from the blood agar plates were suspended in 1 ml of distilled water, boiled for 10 min, centrifuged at 9,300 × g for 5 min and the supernatant was used for the PCR assays.

Table 4.

Validation of multiplex PCR (mPCR) assays to detect “non-top-7” Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli..

| mPCR assay | Serogroups (No. of strains positive/No. of strains tested) |

|---|---|

| 1 | O4 (5/5)a,b, O80 (6/6)b,c, O84 (4/4)a,c, O86 (6/6)b,c, O91 (4/4)a,c, O109 (5/5)a,b,d, O156 (6/6)b,c, O168 (5/5)b |

| 2 | O5 (4/4)b,c, O13/O129/O135 (2/2)b, O22 (7/7)a,b,c, O119 (2/2)b,c, O120 (5/5)b, O123/O186 (5/5)b, O128 (6/6)b,c, O138 (4/4)b,c, O171 (4/4)a,c, O175 (5/5)b |

| 3 | O6 (4/4)a,c, O25 (6/6)b, O33 (5/5)b, O75 (6/6)b,c, O79 (2/2)b, O98 (3/3)a,b, O116 (8/8)a,c, O150 (6/6)b,c, O181 (4/4)b |

| 4 | O2/O50 (4/4)a,b,c, O15 (8/8)a,b,c, O76 (6/6)b,c, O78 (4/4)a,b, O113 (5/5)a,c, O118/O151 (4/4)a,b,c, O126 (5/5)a,b,c, O146 (7/7)a,c, O147 (2/2)a,c, O178 (5/5)b |

| 5 | O7 (4/4)b,c, O8 (20/20)a,b,c, O20 (1/1)a, O55 (6/6)a,c, O62/O68 (4/4)b, O87 (3/3)b, O92 (1/1)b, O136 (6/6)a,b,c, O163 (4/4)a,c |

| 6 | O38 (3/3)a, O39 (3/3)b, O74 (4/4)a, O88 (5/5)a, O96 (4/4)a, O107/O117 (3/3)a, O108 (1/1)a, O115 (1/1)b, O130 (4/4)a, O132 (2/2)a, O141 (3/3)b, O153 (2/2)a |

| 7 | O1 (2/2)b,e, O17/O44/O73/O77/O106 (6/6)b,e, O18 (4/4)b,e, O28 (3/3)b,e, O35 (3/3)b,e, O37 (3/3)b,e, O40 (2/2)b, O43 (4/4)b,e, O51 (4/4)b,e, O53 (2/2)b,e, O69 (3/3)b,e, O70 (3/3)b,e |

| 8 | O81 (3/3)b,e, O82 (3/3)b,e, O85 (3/3)b,e, O90/O127 (2/2)b,c, O102 (4/4)b,e, O105 (3/3)b,e, O124/O164 (2/2)b, O125 (3/3)b,e, O139 (3/3)b,e, O140 (2/2)b,e, O148 (2/2)e |

| 9 | O21 (3/3)b,e, O49 (2/2)b,e, O93 (2/2)b,e, O110 (2/2)b,e, O114 (3/3)b,e, O149 (3/3)b,e, O154 (3/3)b,e, O161 (1/1)e, O169 (2/2)b,e |

| 10 | O46/O134 (5/5)a,b,e, O152 (2/2)b, O159 (2/2)a,b, O160 (2/2)b, O165 (4/4)a,b,e, O170 (3/3)b,e, O172 (2/2)a, O174 (2/2)b,e, O176 (2/2)b,e, O177 (5/5)b,d, O179 (4/4)b, O182 (4/4)a,b,e |

| 11 | O3 (3/3)b,e, O10 (2/2)b,e, O11 (3/3)b,e, O16 (1/1)e, O19 (3/3)b, O23 (3/3)b,e, O29 (3/3)a,b,e, O63 (3/3)b,e, O101/O162 (1/1)d, O112 (3/3)b,e, O131 (3/3)b,e |

| 12 | O9 (2)e, O27 (1/1)e, O41 (2/2)e, O48 (2/2)e, O54 (2/2)e, O56 (1/1)e, O60 (2/2)e, O142 (2/2)e, O143 (2/2)e |

| 13 | O12 (2/2)e, O58 (2/2)e, O64 (2/2)e, O83 (2/2)e, O133 (1/1)e, O166 (2/2)e, O167 (1/1)e |

| 14 | O32 (3/3)e, O65 (2/2)e, O66 (2/2)e, O71 (2/2)e, O100 (2/2)e, O144 (1/1)e, O173 (1/1)e, O180 (2/2)e |

Strains obtained from our culture collection.

Strains obtained from Pennsylvania State University.

Strains obtained from Michigan State University.

Strains obtained from University of Nebraska.

Strains obtained from Food and Drug administration.

Results

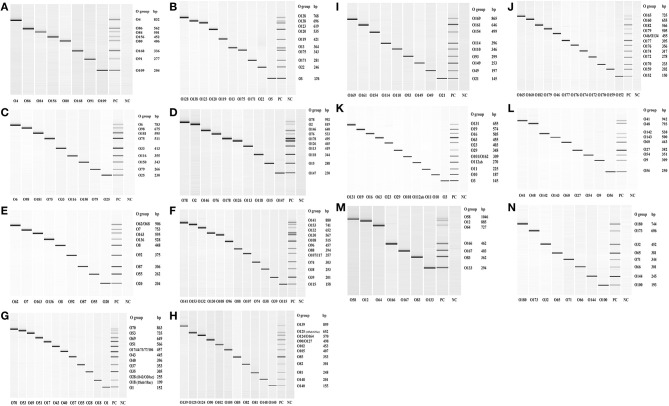

Out of the 158 serogroups of STEC, only five, which include O36, O66, O95, O184, and O187, have not been reported to be present in cattle feces, beef or beef products (Table 1). A total of 14 mPCR assays, each targeting 7–12 O-types of 137 non-top-7 serogroups, were designed (Table 3). Each set of mPCR assay contained primer pairs that generated amplicons of different sizes for each target serogroup that were readily differentiated using a capillary electrophoresis system (Table 3; Figures 1A–N). The PCR product size for all the assays ranged from 145 to 1,046 bp (Table 3; Figures 1A–N). The specificity of each assay was confirmed when only the genes of the targeted serogroups were amplified and none of the serogroups targeted by the other 13 sets and top-7 plus O104 PCR assays was amplified (data not shown). The assays were validated with 460 strains of known serogroups, and the results indicated that all the assays correctly identified the target serogroups (Table 4). The 14 sets of mPCR assays did not include the following 14 serogroups: O14, O30, O36, O52, O57, O59, O95, O97, O104, O158, O183, O184, O185, and O187.

Figure 1.

QIAxcel images of the amplicons of serogroup-specific genes of 137 serogroups of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli amplified by 14 sets (A–N) of multiplex PCR assays. Positive control (PC) included pooled cultures of the known serogroups within each assay. Negative control (NC) included all reagents except the DNA template.

Discussion

Of the known 187 serogroups of E. coli, 158 serogroups have been shown to possess genes that encode for Shiga toxin 1, 2 or both. Serogroups, O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157, are top-7 serogroups responsible for a majority of human STEC illness outbreaks (Scallan et al., 2011; Gould et al., 2013). Among the top-7, fecal shedding of the O157 serogroup has been studied extensively, but relatively fewer studies have examined fecal shedding of the other six non-O157 serogroups in cattle, particularly in the United States (Renter et al., 2005; Cernicchiaro et al., 2013; Dargatz et al., 2013; Baltasar et al., 2014; Ekiri et al., 2014; Paddock et al., 2014; Dewsbury et al., 2015; Noll et al., 2015a; Cull et al., 2017). Among the six top-7 non-O157 serogroups, O26, O45, and O103 are the dominant serogroups in cattle feces with prevalence ranging from 40 to 50%. However, only a small proportion of these serogroups (2–6%) carry Shiga toxin genes (Noll et al., 2015a). Because Shiga toxin genes are located on a prophage, it is suggested that the serogroups lacking these genes either have lost the prophage or have the potential to acquire the prophage (Bielaszewska et al., 2007). A majority of the non-O157 top-six STEC have been show to carry Shiga toxin 1 gene (Shridhar et al., 2017). There is evidence that the type of stx gene carried by STEC in cattle is dependent on the age of the animal and season. Shiga toxin gene of STEC strains in adult cattle are predominantly of the stx2 type, whereas the strains from calves primarily possess stx1 type (Cho et al., 2006; Fernández et al., 2012). In a study on E. coli O157 in Argentina, strains of O157 detected in all seasons were predominantly of the stx2 type, the proportion of strains containing stx1 decreased and proportion of strains possessing both types increased in warm seasons (Fernández et al., 2009).

Many PCR assays have been developed and validated, generally targeting top-7 STEC serogroups, and often in combination with major virulence genes (Shiga toxins 1 and 2, intimin, and enterohemolysin: Bai et al., 2010, 2012; DebRoy et al., 2011b; Fratamico et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2011; Anklam et al., 2012; Paddock et al., 2012; Noll et al., 2015b; Shridhar et al., 2016a). There is limited development of PCR assays targeting the non-top-7 STEC in cattle feces. Individual primer pairs have been described and PCR assays have been developed for each of the 187 serogroups of E. coli (DebRoy et al., 2018). However, there are only a few multiplex PCR assays targeting non-top-7 STEC serogroups (Iguchi et al., 2015b; Sanchez et al., 2015). Sanchez et al. (2015) reported the development of three mPCR assays targeting 21 of the most clinically relevant STEC serogroups associated with infections in humans. The assays included, top-7 serogroups and O5, O15, O55, O76, O91, O104, O118, O113, O123, O128, O146, O165, O172, and O177. Iguchi et al. (2015b) designed primer pairs to develop 20 mPCR assays, with each set containing six to nine serogroups, to detect 147 serogroups that included STEC and non-STEC.

Because cattle are a major reservoir of STEC, we designed a series of multiplex PCR assays targeting serogroups, other than the top-7, that have been shown to be associated with feces, beef, or beef products. The nucleotide sequences of some of the targeted serogroups included in our assays have been previously shown to be 98–99.9% identical to other E. coli serogroups (O2/O50, O13/O129/O135, O17/O44/O73/O77/O106, O42/O28ac, O46/O134, O62/O68, O90/O127, O107/O117, O118/O151, O123/O186, O124/O164, O118/O51; DebRoy et al., 2016). Of the 158 known STEC serogroups, only five serogroups, O36, O66, O95, O184, and O187, have not been detected in cattle. The 14 sets of PCR assays did not include O104 because we have published a mPCR assay for the top-7 STEC and O104 (Paddock et al., 2013). The reason for including O104 with the top-7 STEC was because O104:H4, a hybrid pathotype of STEC and enteroaggregative E. coli, was involved in a major foodborne outbreak in Germany in 2011 (Bielaszewska et al., 2011). Cattle have been shown to harbor serogroup O104 in the gut and shed in the feces, however, none of the isolates was the H4 serotype and none possessed traits characteristic of the enteroaggregative E. coli (Paddock et al., 2013; Shridhar et al., 2016b). The 14 sets of mPCR assays did not include the following 13 serogroups: O14, O30, O36, O52, O57, O59, O95, O97, O158, O183, O184, O185, and O187. Of the 13 serogroups, O14 and O57 have been shown to contain no O-antigen biosynthesis gene clusters (Iguchi et al., 2015a; DebRoy et al., 2016). The reason for not including the remaining 11 serogroups (O30, O36, O52, O59, O95, O97, O158, O183, O184, O185, and O187) was because we were unable to procure known strains of the serogroups required for validation.

STEC serogroups other than the top-7 have been reported to be involved in sporadic cases and a few outbreaks of human illness (McLean et al., 2005; Espie et al., 2006; Buchholz et al., 2011; Mingle et al., 2012). Among the non-top-7 STEC, certain serogroups, such as O1, O2, O8, O15, O25, O43, O75, O76, O86, O91, O101, O102, O113, O116, O156, O160, and O165, specifically certain serotypes within these serogroups, have been involved in outbreaks associated with consumption of contaminated beef in the US and European countries (Eklund et al., 2001; Hussein, 2007). Many of the outbreaks included cases of hemorrhagic colitis and HUS. Serogroups O91 (mostly H21 and H14 serotypes) and O113 (mostly H21 serotype) have been associated with severe cases of hemorrhagic colitis and HUS in the US and other countries (Feng et al., 2014, 2017). Obviously, the difference in virulence between serogroups and serotypes is attributable to specific virulence factors encoded by genes in the chromosome, particularly on large horizontally acquired pathogenicity islands, or on plasmids (Levine, 1987; Bolton, 2011).

In contrast to humans, cattle are generally considered to be not susceptible to STEC infections. Only new born calves, particularly those that are immunocompromised because of deprived colostrum, have been shown to exhibit E. coli O157:H7 infections characterized by bloody diarrhea and attaching and effacing lesions (Dean-Nystrom et al., 1998; Moxley and Smith, 2010). Other serogroups that have been associated with diarrheal diseases of calves include O5, O8, O20, O26, O111, and O113 (Mainil and Daube, 2005). The majority of the serotypes causing infections in calves carried only Shiga toxin 1 gene (Mainil and Daube, 2005). Moxley et al. (2015) have reported isolation of STEC O165:H25 from the colonic mucosal tissue of an adult heifer that died of hemorrhagic colitis.

Some of the serogroups detected in cattle feces such as O5, O8, O9, O11, O15, O20, O49, O59, O62, O65, O69, O71, O76, O78, O86, O87, O89, O91, O100, O114, O115, O116, O119, O120, O128, O138, O139, O141, O143, O147, O159, O163, O167, O172, O174, and O180 have also been detected in swine feces (Cha et al., 2018; Peng et al., 2019). A few of the swine STEC serogroups, particularly O8, O138, O139, O141, and O147, are more often implicated in edema disease in weaned piglets and young finishing pigs (Kaper et al., 2004; Melton-Celsa et al., 2012).

Of the 158 STEC serogroups, 130 serogroups have been associated with clinical cases of diarrhea in humans (Mainil and Daube, 2005; Hussein, 2007; Valilis et al., 2018). Therefore, there are 28 STEC serogoups that have not been reported to cause human infections, which is interesting because Shiga toxins are potent virulence factors. Either these STEC have not yet been linked to an illness or they lack other virulence factors, such as those needed for attachment and colonization, necessary to cause infections. A further understanding and assessment of the virulence potential of these serogroups will require sequencing of the whole genome to obtain a comprehensive gene profile.

In conclusion, the multiplex PCR assays designed in our study, which can be readily performed in most microbiology laboratories, will allow for rapid identification of isolates belonging to the non-top-7 E. coli STEC serogroups that are prevalent in cattle feces, beef or beef products.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

JB, TN, and CD conceived and designed the experiments. JL and XS performed the experiments. XS, JB, CD, ER, RP, and TN contributed reagents, materials, and analysis tools. PS, CD, XS, JB, and TN wrote the paper. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Shannon Manning (Michigan State University), Dr. Rod Moxley (University of Nebraska) and Ms. Isha Patel (U. S. Food and Drug Administration) for providing us with known serogroups of E. coli and Neil Wallace and Leigh Ann George for assistance in the laboratory. This publication is contribution no. 20-251-J of the Kansas Agricultural Experiment Station.

Footnotes

Funding. This material is based upon work that is supported by the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, U. S. Department of Agriculture, under award number 2012-68003-30155. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analyses, preparation of the manuscript or decision to publish.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcimb.2020.00378/full#supplementary-material

References

- Anklam K. S., Kanankege K. S. T., Gonzales T. K., Kaspar C. W., Döpfer D. (2012). Rapid and reliable detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli by real-time multiplex PCR. J. Food Prot. 75, 643–650. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-392 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J., Paddock Z. D., Shi X., Li S., An B., Nagaraja T. G. (2012). Applicability of a multiplex PCR to detect the seven major Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli based on genes that code for serogroup-specific O-antigens and major virulence factors in cattle feces. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9, 541–548. 10.1089/fpd.2011.1082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai J., Shi X., Nagaraja T. G. (2010). A multiplex PCR procedure for the detection of six major virulence genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7. J. Microbiol. Meth. 82, 85–89. 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baltasar P., Milton S., Swecker W., Elvinger F., Ponder M. (2014). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli distribution and characterization in a pasture-based cow-calf production system. J. Food. Prot. 77, 722–731. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelheim K. A. (2007). The non-O157 shiga-toxigenic (verocytotoxigenic) Escherichia coli; under-rated pathogens. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 33, 67–87. 10.1080/10408410601172172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelheim K. A., Beutin L. (2003). Rapid laboratory identification and characterization of verocytotoxigenic (Shiga toxin producing) Escherichia coli (VTEC/STEC). J. Appl. Microbiol. 95, 205–217. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02031.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bettelheim K. A., Goldwater P. N. (2014). Serotypes of non-O157 shigatoxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC). Adv. Microbiol. 04:13. 10.4236/aim.2014.4704515135507 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beutin L., Geier D., Steinruck H., Zimmermann S., Scheutz F. (1993). Prevalence and some properties of verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin)-producing Escherichia coli in seven different species of healthy domestic animals. J. Clin. Microbiol. 31, 2483–2488. 10.1128/JCM.31.9.2483-2488.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutin L., Geier D., Zimmermann S., Aleksic S., Gillespie H. A., Whittam T. S. (1997). Epidemiological relatedness and clonal types of natural populations of Escherichia coli strains producing Shiga toxins in separate populations of cattle and sheep. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 2175–2180. 10.1128/AEM.63.6.2175-2180.1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beutin L., Muller W. (1998). Cattle and verotoxigenic Escherichia coli (VTEC), an old relationship? Vet. Rec. 142, 283–284. 10.1136/vr.142.11.283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielaszewska M., Dobrindt U., Gärtner J., Gallitz I., Hacker J., Karch H., et al. (2007). Aspects of genome plasticity in pathogenic Escherichia coli. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 297, 625–639. 10.1016/j.ijmm.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bielaszewska M., Karch H. (2000). Non-O157:H7 Shiga toxin (verocytotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli strains: epidemiological significance and microbiological diagnosis. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 16, 711–718. 10.1023/A:1008972605514 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bielaszewska M., Mellmann A., Zhang W., Köck R., Fruth A., Bauwens A., et al. (2011). Characterisation of the Escherichia coli strain associated with an outbreak of haemolytic uraemic syndrome in Germany, 2011: a microbiological study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 11, 671–676. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70165-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M., Blanco J. E., Blanco J., Mora A., Prado C., Alonso M. P., et al. (1997). Distribution and characterization of faecal verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) isolated from healthy cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 54, 309–319. 10.1016/S0378-1135(96)01292-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M., Blanco J. E., Mora A., Dahbi G., Alonso M. P., Gonzalez E. A., et al. (2004a). Serotypes, virulence genes, and intimin types of Shiga toxin (Verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli isolates from cattle in Spain and identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-). J. Clin. Microbiol. 42, 645–651. 10.1128/JCM.42.2.645-651.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M., Padola N. L., Kruger A., Sanz M. E., Blanco J. E., Gonzalez E. A., et al. (2004b). Virulence genes and intimin types of Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and beef products in Argentina. Int. Microbiol. 7, 269–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanco M., Schumacher S., Tasara T., Zweifel C., Blanco J. E., Dahbi G., et al. (2005). Serotypes, intimin variants and other virulence factors of eae positive Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy cattle in Switzerland. Identification of a new intimin variant gene (eae-eta2). BMC Microbiol. 5:23. 10.1186/1471-2180-5-23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton D. J. (2011). Verocytotoxigenic (Shiga toxin-producing) Escherichia coli: virulence factors and pathogenicity in the farm to fork paradigm. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 8, 357–365. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonardi S., Foni E., Brindani F., Bacci C., Chiapponi C., Cavallini P. (2004). Detection and characterization of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) O157 and non-O157 in cattle at slaughter. New Microbiol. 27, 255–261. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks J. T., Sowers E. G., Wells J. G., Greene K. D., Griffin P. M., Hoekstra R. M., et al. (2005). Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States, 1983-2002. J. Infect. Dis. 192, 1422–1429. 10.1086/466536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz U., Bernard H., Werber D., Böhmer M. M., Remschmidt C., Wilking H., et al. (2011). German outbreak of Escherichia coli O104:H4 associated with sprouts. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 1763–1770. 10.1056/NEJMoa1106482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumunang E. W., McAllister T. A., Zaheer R., Ortega Polo R., Stanford K., King R., et al. (2019). Characterization of non-O157 Escherichia coli from cattle faecal samples in the North-West province of South Africa. Microorganisms 7:8. 10.3390/microorganisms7080272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cernicchiaro N., Cull C. A., Paddock Z. D., Shi X., Bai J., Nagaraja T. G., et al. (2013). Prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and associated virulence genes in feces of commercial feedlot cattle. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 10, 835–841. 10.1089/fpd.2013.1526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha W., Fratamico P. M., Ruth L. E., Bowman A. S., Nolting J. M., Manning S. D., et al. (2018). Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in finishing pigs: Implications on public health. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 264, 8–15. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2017.10.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman P. A. (2000). Methods available for the detection of Escherichia coli O157 in clinical, food and environmental samples. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 16, 733–740. 10.1023/A:1008985008240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Diez-Gonzales F., Fossler C. P., Wells S. J., Hedberg C. W., Kaneene J. B., et al. (2006). Prevalence of Shiga toxin-encoding bacteria and Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from dairy farms and county fairs. Vet. Microbiol. 118, 289–298. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.07.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobbold R., Desmarchelier P. (2001). Characterisation and clonal relationships of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli (STEC) isolated from Australian dairy cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 79, 323–335. 10.1016/S0378-1135(00)00366-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cull C. A., Renter D. G., Dewsbury D. M., Noll L. W., Shridhar P. B., Ives S. E., et al. (2017). Feedlot- and pen-level prevalence of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in feces of commercial feedlot cattle in two major U.S. cattle feeding areas. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 14, 309–317. 10.1089/fpd.2016.2227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargatz D. A., Bai J., Lubbers B. V., Kopral C. A., An B., Anderson G. A. (2013). Prevalence of Escherichia coli O-types and Shiga toxin genes in fecal samples from feedlot cattle. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10, 392–396. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis T. K., Van De Kar N. C. A. J., Tarr P. I. (2014). Shiga toxin/Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infections: Practical clinical perspectives. Microbiol. Spect. 2:4. 10.1128/microbiolspec.EHEC-0025-2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dean-Nystrom E. A., Bosworth B. T., Moon H. W., O'Brien A. D. (1998). Bovine infection with Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli, in Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Other Shiga Toxin-producing E. coli Strains, eds Kaper J. B., O'Brien A. D. (Washington, DC: ASM Press; ), 261–267. [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy C., Fratamico P. M., Roberts E. (2018). Molecular serogrouping of Escherichia coli. Anim. Hlth. Res. Rev. 19, 1–16. 10.1017/S1466252317000093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy C., Fratamico P. M., Yan X., Baranzoni G., Liu Y., Needleman D. S., et al. (2016). Comparison of O-antigen gene clusters of all O-serogroups of Escherichia coli and proposal for adopting a new nomenclature for O-typing. PLoS ONE 11:e0147434 10.1371/journal.pone.0147434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy C., Roberts E., Fratamico P. M. (2011a). Detection of O antigens in Escherichia coli. Anim. Health Res. Rev. 12, 169–185. 10.1017/S1466252311000193 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DebRoy C., Roberts E., Valadez A. M., Dudley E. G., Cutter C. N. (2011b). Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O26, O45, O103, O111, O113, O121, O145, and O157 serogroups by multiplex polymerase chain reaction of the wzx gene of the O-antigen gene cluster. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8, 651–652. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewsbury D. M. A., Renter D. G., Shridhar P. B., Noll L. W., Shi X., Nagaraja T. G., et al. (2015). Summer and winter prevalence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157 in feces of feedlot cattle. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 12, 726–732. 10.1089/fpd.2015.1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diarra M. S., Giguère K., Malouin F., Lefebvre B., Bach S., Delaquis P., et al. (2009). Genotype, serotype, and antibiotic resistance of sorbitol-negative Escherichia coli isolates from feedlot cattle. J. Food Prot. 72, 28–36. 10.4315/0362-028X-72.1.28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekiri A. B., Landblom D., Doetkott D., Olet S., Shelver W. L., Khaitsa M. L. (2014). Isolation and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serogroups O26, O45, O103, O111, O113, O121, O145, and O157 shed from range and feedlot cattle from postweaning to slaughter. J. Food Prot. 77, 1052–1061. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-373 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eklund M., Scheutz F., Siitonen A. (2001). Clinical isolates of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: serotypes, virulence characteristics, and molecular profiles of strains of the same serotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 2829–2834. 10.1128/JCM.39.8.2829-2834.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis C., McDowell D., Bolton D. J. (2012). The prevalence, distribution and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) serotypes and virulotypes from a cluster of bovine farms. J. Appl. Microbiol. 113, 1238–1248. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2012.05421.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espie E., Grimont F., Vaillant V., Montet M. P., Carle I., Bavai C., et al. (2006). O148 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli outbreak: microbiological investigation as a useful complement to epidemiological investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 12, 992–998. 10.1111/j.1469-0691.2006.01468.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan R., Shao K., Yang X., Bai X., Fu S., Sun H., et al. (2019). High prevalence of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in beef cattle detected by combining four selective agars. BMC Microbiology 19:213. 10.1186/s12866-019-1582-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng P. C. H., Delannoy S., Lacher D. W., Bosilavac J. M., Fach P., Beutin L. (2017). Shiga toxin-producing serogroup O91 Escherichia coli strains isolated from food and environmental samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e01231–e012317. 10.1128/AEM.01231-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng P. C. H., Delannoy S., Lacher D. W., Fernando dos Santos L., Beutin L., Fach P., et al. (2014). Genetic diversity and virulence potential of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O113:H21 strains isolated from clinical, environmental, and food sources. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 4757–4763. 10.1128/AEM.01182-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández D., Irino K., Sanz M. E., Padola N. L., Parma A. E. (2010). Characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from dairy cows in Argentina. Lett. Appl. Micribiol. 51, 377–382. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02904.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández D., Rodriguez E. M., Arroyo G. H., Padola N. L., Parma A. E. (2009). Seasonal variation of Shiga toxin-encoding genes (stx) and detection of E. coli O157 in dairy cattle from Argentina. J. Appl. Micribiol. 106, 1250–1267. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.04088.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández D., Sanz M. E., Parma A. E., Padola N. L. (2012). Short communiaction: Characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from newborn, milk-fed, and growing calves in Argentina. J. Dairy Sci, 95, 5340–5343. 10.3168/jds.2011-5140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratamico P. M., Bagi L. K., Cray W. C., Narang N., Yan X., Medina M., et al. (2011). Detection by multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assays and isolation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serogroups O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, and O145 in ground beef. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 8, 601–607. 10.1089/fpd.2010.0773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratamico P. M., DebRoy C., Miyamoto T., Liu Y. (2009). PCR detection of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O145 in food by targeting genes in the E. coli O145 O-antigen gene cluster and the Shiga toxin 1 and Shiga toxin 2 genes. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 6, 605–611. 10.1089/fpd.2008.0254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geue L., Segura-Alvarez M., Conraths F., Kuczius T., Bockemühl J., Karch H., et al. (2002). A long-term study on the prevalence of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) on four German cattle farms. Epidemiol. Infect. 129, 173–185. 10.1017/S0950268802007288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gioffré A., Meichtri L., Miliwebsky E., Baschkier A., Chillemi G., Romano M. I., et al. (2002). Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli by PCR in cattle in Argentina: Evaluation of two procedures. Vet. Microbiol. 87, 301–313. 10.1016/S0378-1135(02)00079-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez A. G., Cerqueira A. M., Guth B. E., Coutinho C. A., Liberal M. H., Souza R. M., et al. (2016). Serotypes, virulence markers and cell invasion ability of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from healthy dairy cattle. J. Appl. Microbiol. 121, 1130–1143. 10.1111/jam.13230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez E. A., Blanco J. (1989). Serotypes and antibiotic resistance of verotoxigenic (VTEC) and necrotizing (NTEC) Escherichia coli strains isolated from calves with diarrhoea. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 51, 31–36. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1989.tb03414.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould L. H., Mody R. K., Ong K. L., Clogher P., Cronquist A. B., Garman K. N., et al. (2013). Increased recognition of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli infections in the United States during 2000-2010: epidemiologic features and comparison with E. coli O157 Infections. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10, 453–460. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitzky M. A., Bettelheim K. A., Djordjevic S. P. (2000). The isolation of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O111:H- from Australian cattle. Aust. Vet. J. 78, 636–637. 10.1111/j.1751-0813.2000.tb11941.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitzky M. A., Bettelheim K. A., Djordjevic S. P. (2001). The detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in diagnostic bovine faecal samples using vancomycin-cefixime-cefsulodin blood agar and PCR. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 198, 17–22. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2001.tb10613.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitzky M. A., Mercieca K., Bettelheim K. A., Djordjevic S. P. (2005). Bovine feces from animals with gastrointestinal infections are a source of serologically diverse atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Shiga toxin-producing E. coli strains that commonly possess intimin. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 3405–3412. 10.1128/AEM.71.7.3405-3412.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornitzky M. A., Vanselow B. A., Walker K., Bettelheim K. A., Corney B., Gill P., et al. (2002). Virulence properties and serotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy Australian cattle. Appl. Eenviron. Microbiol. 68, 6439–6445. 10.1128/AEM.68.12.6439-6445.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein H. S. (2007). Prevalence and pathogenicity of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in beef cattle and their products. J. Anim. Sci. 85, E63–E72. 10.2527/jas.2006-421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein H. S., Bollinger L. M. (2005). Prevalence of Shiga toxin–producing Escherichia coli in beef cattle. J. Food Protect. 68, 2224–2241. 10.4315/0362-028X-68.10.2224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi A., Iyoda S., Kikuchi T., Ogura Y., Katsura K., Ohnishi M., et al. (2015a). A complete view of the genetic diversity of the Escherichia coli O-antigen biosynthesis gene cluster. DNA Res. 22, 101–107. 10.1093/dnares/dsu043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iguchi A., Iyoda S., Seto K., Morita-Ishihara T., Scheutz F., Ohnishi M. (2015b). Escherichia coli O-Genotyping PCR: a comprehensive and practical platform for molecular O serogrouping. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 2427–2432. 10.1128/JCM.00321-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irino K., Kato M. A. M. F., Vaz T. M. I., Ramos I. I., Souza M. A. C., Cruz A. S., et al. (2005). Serotypes and virulence markers of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolated from dairy cattle in São Paulo State, Brazil. Vet. Microbiol. 105, 29–36. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jajarmi M., Imani Fooladi A. A., Badouei M. A., Ahmadi A. (2017). Virulence genes, Shiga toxin subtypes, major O-serogroups, and phylogenetic background of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from cattle in Iran. Microb. Pathog. 109, 274–279. 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.05.041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joensen K. G., Tetzschner A. M., Iguchi A., Aarestrup F. M., Scheutz F. (2015). Rapid and easy In Silico serotyping of Escherichia coli isolates by use of whole-genome sequencing data. J. Clin. Microbiol. 53, 2410–2426. 10.1128/JCM.00008-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaper J. B., Nataro J. P., Mobley H. L. (2004). Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 123–140. 10.1038/nrmicro818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmali M. A., Gannon V., Sargeant J. M. (2010). Verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC). Vet. Microbiol. 140, 360–370. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.04.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kido N., Torgov V. I., Sugiyama T., Uchiya K., Sugihara H., Komatsu T., et al. (1995). Expression of the O9 polysaccharide of Escherichia coli: sequencing of the E. coli O9 rfb gene cluster, characterization of mannosyl transferases, and evidence for an ATP-binding cassette transport system. J. Bacteriol. 177, 2178–2187. 10.1128/JB.177.8.2178-2187.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacher D. W., Gangiredla J., Jackson S. A., Elkins C. A., Feng P. C. H. (2014). Novel Microarray design for molecular serotyping of shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from fresh produce. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 4677–4682. 10.1128/AEM.01049-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Kusumoto M., Iwata T., Iyoda S., Akiba M. (2017). Nationwide investigation of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli among cattle in Japan revealed the risk factors and potentially virulent subgroups. Epidemiol. Infect. 145, 1557–1566. 10.1017/S0950268817000474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leomil L., Aidar-Ugrinovich L., Guth B. E. C., Irino K., Vettorato M. P., Onuma D. L., et al. (2003). Frequency of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolates among diarrheic and non-diarrheic calves in Brazil. Vet. Microbiol. 97, 103–109. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2003.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung P. H., Yam W. C., Ng W. W., Peiris J. S. (2001). The prevalence and characterization of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and pigs in an abattoir in Hong Kong. Epidemiol. Infect. 126, 173–179. 10.1017/S0950268801005210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine M. (1987). Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea - enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. Am. J. Infect. Dis. 155, 377–389. 10.1093/infdis/155.3.377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A., Sultan O., Lau H. K., Wong E., Hartman G., Lauzon C. R. (2011). O serogroup specific real time PCR assays for the detection and identification of nine clinically relevant non-O157 STECs. Food Microbiol. 28, 478–483. 10.1016/j.fm.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D., Cole R. A., Reeves P. R. (1996). An O-antigen processing function for Wzx (RfbX): a promising candidate for O-unit flippase. J. Bacteriol. 178, 2102–2107. 10.1128/JB.178.7.2102-2107.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y., Fratamico P. (2006). Escherichia coli O antigen typing using DNA microarrays. Mol. Cell Probes 20, 239–244. 10.1016/j.mcp.2006.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luedtke B. E., Bono J. L., Bosilevac J. M. (2014). Evaluation of real time PCR assays for the detection and enumeration of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli directly from cattle feces. J. Microbiol. Methods 105, 72–79. 10.1016/j.mimet.2014.07.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madic J., Vingadassalon N., de Garam C. P., Marault M., Scheutz F., Brugere H., et al. (2011). Detection of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serotypes O26:H11, O103:H2, O111:H8, O145:H28, and O157:H7 in raw-milk cheeses by using multiplex real-time PCR. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2035–2041. 10.1128/AEM.02089-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mainil J. G., Daube G. (2005). Verotoxigenic Escherichia coli from animals, humans and foods: who's who? J. Appl. Microbiol. 98, 1332–1344. 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2005.02653.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masana M. O., D'Astek B. A., Palladino P. M., Galli L., Del Castillo L. L., Carbonari etal. (2011). Genotypic chatcterization of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in beef abattoirs of Argentina. J. Food Prot. 74, 2008–2017. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-11-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean C., Bettelheim K. A., Kuzevski A., Falconer L., Djordjevic S. P. (2005). Isolation of Escherichia coli O5:H-, possessing genes for Shiga toxin 1, intimin-beta and enterohaemolysin, from an intestinal biopsy from an adult case of bloody diarrhoea: evidence for two distinct O5:H- pathotypes. J. Med. Microbiol. 54(Pt 6), 605–607. 10.1099/jmm.0.45938-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meichtri L., Miliwebsky E., Gioffre A., Chinen I., Baschkier A., Chillemi G., et al. (2004). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in healthy young beef steers from Argentina: prevalence and virulence properties. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 96, 189–198. 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2004.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekata H., Iguchi A., Kawano K., Kirino Y., Kobayashi I., Misawa N. (2014). Identification of O serotypes, genotypes, and virulotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates, including non-O157 from beef cattle in Japan. J. Food Prot. 77, 1269–1274. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-13-506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melton-Celsa A., Mohawk K., Teel L., O'Brien A. (2012). Pathogenesis of Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 357, 67–103. 10.1007/82_2011_176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mingle L. A., Garcia D. L., Root T. P., Halse T. A., Quinlan T. M., Armstrong L. R., et al. (2012). Enhanced identification and characterization of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli: a six-year study. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 9, 1028–1036. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyao Y., Kataoka T., Nomoto T., Kai A., Itoh T., Itoh K. (1998). Prevalence of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli harbored in the intestine of cattle in Japan. Vet. Microbiol. 61, 137–143. 10.1016/S0378-1135(98)00165-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monaghan A., Byrne B., Fanning S., Sweeney T., McDowell D., Bolton D. J. (2011). Serotypes and virulence profiles of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolates from bovine farms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 8662–8668. 10.1128/AEM.06190-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monday S. R., Beisaw A., Feng P. C. H. (2007). Identification of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli seropathotypes A and B by multiplex PCR. Mol. Cell Probes. 21, 308–311. 10.1016/j.mcp.2007.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montenegro M. A., Bulte M., Trumpf T., Aleksic S., Reuter G., Bulling E., et al. (1990). Detection and characterization of fecal verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli from healthy cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 28, 1417–1421. 10.1128/JCM.28.6.1417-1421.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora A., Blanco J. s,.E, Blanco M., Alonso M. P., Dhabi G., et al. (2005). Antimicrobial resistance of Shiga toxin (verotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli O157: H7 and non-O157 strains isolated from humans, cattle, sheep and food in Spain. Res. Microbiol. 156, 793–806. 10.1016/j.resmic.2005.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreira C. N., Pereira M. A., Brod C. S., Rodrigues D. P., Carvalhal J. B., Aleixo J. A. (2003). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) isolated from healthy dairy cattle in southern Brazil. Vet. Microbiol. 93, 179–183. 10.1016/S0378-1135(03)00041-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxley R. A., Smith D. R. (2010). Attaching and effacing Escherichia coli infections in cattle. Vet. Clin. North Amer. Food Anim. 26, 29–56. 10.1016/j.cvfa.2009.10.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moxley R. A., Stromberg Z. R., Lewis G. L., Loy J. D., Brodersen B. W., Patel I. R., et al. (2015). Haemorrhagic colitis associated with enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli O165:H25 infection in a yearling feedlot heifer. J. Microbiol. Mtds Case Rep. 2, 1–6. 10.1099/jmmcr.0.005004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muniesa M., Blanco J. E., de Simon M., Serra-Moreno R., Blanch A. R., Jofre J. (2004). Diversity of stx2 converting bacteriophages induced from Shiga-toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from cattle. Microbiology 150(Pt 9), 2959–2971. 10.1099/mic.0.27188-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasoff M. S., Baker H. V., II., Wolf R. E., Jr. (1984). DNA sequence of the Escherichia coli gene, gnd, for 6-phosphogluconate dehydrogenase. Gene 27, 253–264. 10.1016/0378-1119(84)90070-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarro A., Cauich-Sanchez P. I., Trejo A., Gutierrez A., Diaz S. P., Diaz C. M., et al. (2018). Characterization of diarrheagenic strains of Escherichia coli isolated from cattle raised in three regions of Mexico. Front. Microbiol. 9:2373. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll L. W., Shridhar P. B., Dewsbury D. M., Shi X., Cernicchiaro N., Renter D. G., et al. (2015a). A comparison of culture- and PCR-based methods to detect six major non-O157 serogroups of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in cattle feces. PLoS ONE 10:e0135446. 10.1371/journal.pone.0135446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noll L. W., Shridhar P. B., Shi X., An B., Cernicchiaro N., Renter D. G., et al. (2015b). A four-plex real-time PCR assay, based on rfbE, stx1, stx2, and eae genes, for the detection and quantification of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 in cattle feces. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 12, 787–794. 10.1089/fpd.2015.1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman K. N., Clawson M. L., Strockbine N. A., Mandrell R. E., Johnson R., Ziebell K., et al. (2015). Comparison of whole genome sequences from human and non-human Escherichia coli O26 strains. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 5:21. 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock Z., Shi X., Bai J., Nagaraja T. G. (2012). Applicability of a multiplex PCR to detect O26, O45, O103, O111, O121, O145, and O157 serogroups of Escherichia coli in cattle feces. Vet. Microbiol. 156, 381–388. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2011.11.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock Z. D., Bai J., Shi X., Renter D. G., Nagaraja T. G. (2013). Detection of Escherichia coli O104 in the feces of feedlot cattle by a multiplex PCR assay designed to target major genetic traits of the virulent hybrid strain responsible for the 2011 German outbreak. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 3522–3525. 10.1128/AEM.00246-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paddock Z. D., Renter D. G., Cull C. A., Shi X., Bai J., Nagaraja T. G. (2014). Escherichia coli O26 in feedlot cattle: fecal prevalence, isolation, characterization, and effects of an E. coli O157 vaccine and a direct-fed microbial. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 11, 186–193. 10.1089/fpd.2013.1659 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette S.-J., Stanford K., Thomas J., Reuter T. (2018). Quantitative surveillance of shiga toxins 1 and 2, Escherichia coli O178 and O157 in feces of western-Canadian slaughter cattle enumerated by droplet digital PCR with a focus on seasonality and slaughterhouse location. PLoS ONE 13:e0195880. 10.1371/journal.pone.0195880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parma A. E., Sanz M. E., Blanco J. E., Blanco J., Vinas M. R., Blanco M., et al. (2000). Virulence genotypes and serotypes of verotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from cattle and foods in Argentina. Importance in public health. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 16, 757–762. 10.1023/A:1026746016896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Z., Liang W., Hu Z., Li X., Guo R., Hua L., et al. (2019). O-serogroups, virulence genes, antimicrobial susceptibility, and MLST genotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli from swine and cattle in Central China. BMC Veterinary Res. 15, 427–427. 10.1186/s12917-019-2177-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perelle S., Dilasser F., Grout J., Fach P. (2004). Detection by 5'-nuclease PCR of Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli O26, O55, O91, O103, O111, O113, O145 and O157:H7, associated with the world's most frequent clinical cases. Mol. Cell. Probes 18, 185–192. 10.1016/j.mcp.2003.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polifroni R., Etcheverría A. I., Sanz M. E., Cepeda R. E., Krüger A., Lucchesi P. M., et al. (2012). Molecular characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from the environment of a dairy farm. Curr. Microbiol. 3, 337–343. 10.1007/s00284-012-0161-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradel N., Livrelli V., De Champs C., Palcoux J. B., Reynaud A., Scheutz F., et al. (2000). Prevalence and characterization of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle, food, and children during a one-year prospective study in France. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 1023–1031. 10.1128/JCM.38.3.1023-1031.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renter D. G., Morris J. G., Sargeant J. M., Hungerford L. L., Berezowski J., Ngo T., et al. (2005). Prevalence, risk factors, O serogroups, and virulence profiles of Shiga toxin-producing bacteria from cattle production environments. J. Food Prot. 68, 1556–1565. 10.4315/0362-028X-68.8.1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel G., Reeves P. (2003). Biosynthesis of O-antigens: genes and pathways involved in nucleotide sugar precursor synthesis and O-antigen assembly. Carbohydr. Res. 338, 2503–2519. 10.1016/j.carres.2003.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez S., Llorente M. T., Echeita M. A., Herrera-Leon S. (2015). Development of three multiplex PCR assays targeting the 21 most clinically relevant serogroups associated with Shiga toxin-producing E. coli infection in humans. PLoS ONE 10:e0117660. 10.1371/journal.pone.0117660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu K. S., Clarke R. C., Gyles C. L. (1999). Virulence markers in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle. Can. J. Vet. Res. 63, 177–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu K. S., Clarke R. C., McFadden K., Brouwer A., Louie M., Wilson J., et al. (1996). Prevalence of the eaeA gene in verotoxigenic Escherichia coli strains from dairy cattle in Southwest Ontario. Epidemiol. Infect. 116, 1–7. 10.1017/S095026880005888X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scallan E., Hoekstra R. M., Angulo F. J., Tauxe R. V., Widdowson M.-A., Roy S. L. (2011). Foodborne illness acquired in the United States—major pathogens. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 7–15. 10.3201/eid1701.P11101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurman R. D., Hariharan H., Heaney S. B., Rahn K. (2000). Prevalence and characteristics of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in beef cattle slaughtered on Prince Edward Island. J. Food Prot. 63, 1583–1586. 10.4315/0362-028X-63.11.1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott L., McGee P., Walsh C., Fanning S., Sweeney T., Blanco J., et al. (2009). Detection of numerous verotoxigenic E. coli serotypes, with multiple antibiotic resistance from cattle faeces and soil. Vet. Microbiol. 134, 288–293. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2008.08.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shridhar P. B., Noll L. W., Shi X., An B., Cernicchiaro N., Renter D. G., et al. (2016a). Multiplex quantitative PCR assays for the detection and quantification of the six major non-O157 Escherichia coli serogroups in cattle feces. J. Food Prot. 79, 66–74. 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-15-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shridhar P. B., Noll L. W., Shi X., Cernicchiaro N., Renter D. G., Bai J., et al. (2016b). Escherichia coli O104 in feedlot cattle feces: prevalence, isolation and characterization. PLoS ONE 11:e0152101. 10.1371/journal.pone.0152101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shridhar P. B., Siepker C., Noll L. W., Shi X., Nagaraja T. G., Bai J. (2017). Shiha toxin subtypes of non-O157 Escherichia coli serogroups isolated from cattle feces. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 7:121. 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H. R., Scotland S. M., Willshaw G. A., Wray C., McLaren I. M., Cheasty T., et al. (1988). Vero cytotoxin production and presence of VT genes in Escherichia coli strains of animal origin. Microbiology 134, 829–834. 10.1099/00221287-134-3-829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stromberg Z. R., Lewis G. L., Schneider L. G., Erickson G. E., Patel I. R., Smith D. R., et al. (2018). Culture-based quantification with molecular characterization of non-O157 and O157 enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli isolates from rectoanal mucosal swabs of feedlot cattle. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 15, 26–32. 10.1089/fpd.2017.2326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suthienkul O., Brown J. E., Seriwatana J., Tienthongdee S., Sastravaha S., Echeverria P. (1990). Shiga-like-toxin-producing Escherichia coli in retail meats and cattle in Thailand. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 56, 1135–1139. 10.1128/AEM.56.4.1135-1139.1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaro J. D., Galli L., Lound L. H., Leotta G. A., Piaggio M. C., Carbonari C. C., et al. (2012). Non-O157:H7 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli in bovine rectums and surface water streams on a beef cattle farm in Argentina. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 9, 878–884. 10.1089/fpd.2012.1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timm C. D., Irino K., Gomes T. A. T., Viera M. M., Guth B. E. C., Vaz T. M. I., et al. (2007). Virulence markers and serotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from cattle in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 44, 419–425. 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2006.02085.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urdahl A. M., Beutin L., Skjerve E., Zimmermann S., Wasteson Y. (2003). Animal host associated differences in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli isolated from sheep and cattle on the same farm. J. Appl. Microbiol. 95, 92–101. 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.01964.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valilis E., Ramsey A., Sidiq S., DuPont H. L. (2018). Non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli-A poorly appreciated enteric pathogen: systematic review. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 76, 82–87. 10.1016/j.ijid.2018.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells J. G., Shipman L. D., Greene K. D., Sowers E. G., Green J. H., Cameron D. N., et al. (1991). Isolation of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7 and other Shiga-like-toxin-producing E. coli from dairy cattle. J. Clin. Microbiol. 29, 985–989. 10.1128/JCM.29.5.985-989.1991 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieler L., Vieler E., Erpenstein C., Schlapp T., Steinruck H., Bauerfeind R., et al. (1996). Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli strains from bovines: association of adhesion with carriage of eae and other genes. J. Clin. Microbiol. 34, 2980–2984. 10.1128/JCM.34.12.2980-2984.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieler L. H., Schwanitz A., Vieler E., Busse B., Steinrück H., Kaper J. B., et al. (1998). Virulence properties of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains of serogroup O118, a major group of STEC pathogens in calves. J. Clin. Microbiol. 36, 1604–1607. 10.1128/JCM.36.6.1604-1607.1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson J. B., McEwen S. A., Clarke R. C., Leslie K. E., Wilson R. A., Waltner-Toews D., et al. (1992). Distribution and characteristics of verocytotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from Ontario dairy cattle. Epidemiol. Infect. 108, 423–439. 10.1017/S0950268800049931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wray C., McLaren I. M., Carroll P. J. (1993). Escherichia coli isolated from farm animals in England and Wales between 1986 and 1991. Vet. Rec. 133, 439–442. 10.1136/vr.133.18.439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zweifel C., Schumacher S., Blanco M., Blanco J. E., Tasara T., Blanco J., et al. (2005). Phenotypic and genotypic characteristics of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) from Swiss cattle. Vet. Microbiol. 105, 37–45. 10.1016/j.vetmic.2004.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.