Abstract

Transcription initiation is a key checkpoint and highly regulated step of gene expression. The sigma (σ) subunit of RNA polymerase (RNAP) controls all transcription initiation steps, from recognition of the −10/−35 promoter elements, upon formation of the closed promoter complex (RPc), to stabilization of the open promoter complex (RPo) and stimulation of the primary steps in RNA synthesis. The canonical mechanism to regulate σ activity upon transcription initiation relies on activators that recognize specific DNA motifs and recruit RNAP to promoters. This mini-review describes an emerging group of transcriptional regulators that form a complex with σ or/and RNAP prior to promoter binding, remodel the σ subunit conformation, and thus modify RNAP activity. Such strategy is widely used by bacteriophages to appropriate the host RNAP. Recent findings on RNAP-binding protein A (RbpA) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Crl from Escherichia coli suggest that activator-driven changes in σ conformation can be a widespread regulatory mechanism in bacteria.

Keywords: RNAP-binding transcriptional regulators, sigma subunit conformational dynamics, promoter specificity, RbpA, Tuberculosis

Introduction

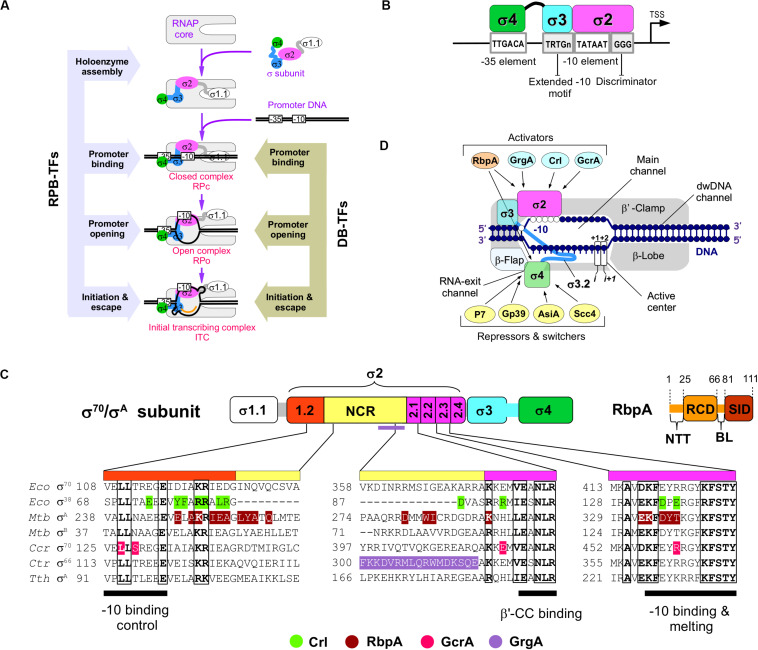

Transcription initiation starts with the assembly of the active RNA polymerase (RNAP) holoenzyme from the catalytic core (subunits 2α, β, β′, ω) and the promoter–specificity subunit sigma (σ). The RNAP holoenzyme binds to promoter DNA, and forms a closed promoter complex (RPc) that isomerizes into the open promoter complex (RPo) through several intermediates (Buc and McClure, 1985; Saecker et al., 2011; Boyaci et al., 2019). Upon isomerization, RNAP melts ∼13 bp of DNA duplex between the promoter positions –11 to +2 that encompass the transcription start site (Figure 1A). Recognition of the −10 (Escherichia coli consensus motif T–12A–11T–10A–9A–8T–7) and −35 elements (E. coli consensus motif T–35T–34G–33A–32C–31A–30) of the promoter (Figure 1B) and promoter DNA melting depend on the σ subunit (Feklistov et al., 2014; Zuo and Steitz, 2015). All bacteria have at least one principal σ subunit [group 1: σ70 in E. coli and σA in other species (Gruber and Gross, 2003)] that ensures transcription of most genes [e.g., at least 70% in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb)] (Cortes et al., 2014). Alternative σ subunits (groups 2–4) control transcription of specialized sets of genes upon stress response, starvation, and stationary growth (Österberg et al., 2011). Compared with group 1 σ subunits, the group 2 stress-response/stationary phase σ subunits (E. coli σS and Mtb σB) lack the N-terminal variable domain σ1.1 and have a shorter non-conserved region (NCR) located in domain σ2 (Figure 1C). RNAPs harboring group 1 and group 2 σ subunits can transcribe the same promoter sets (Rodrigue et al., 2006; Hu et al., 2014). The σ2 domain harbors the highly conserved regions 1.2, 2.1, 2.2, 2.3, and 2.4 that are essential for binding to RNAP β′ clamp, for recognition of the−10 element, and for melting of promoter DNA (Feklistov and Darst, 2011; Zhang et al., 2012). About 73% of the σ2 contact surface with ssDNA of the −10 element is formed by region 2.3 residues. In addition, residues in region 1.2 contact with the T–7 base of the −10 element (Feklistov and Darst, 2011) and control recognition of the −10 element allosterically (Zenkin et al., 2007; Morichaud et al., 2016). The σ70 NCR interacts with promoter DNA at positions –16/–17 (R157Eco) and is implicated in DNA unwinding (Narayanan et al., 2018). The σ70 NCR/β′ interaction facilitates promoter escape (Leibman and Hochschild, 2007). Domain σ4 interacts with the β-flap domain of core RNAP and harbors a helix-turn-helix DNA binding domain that recognizes the −35 motif. The σ3 and σ4 subunits are connected by a weakly structured linker (region 3.2) that fills the RNA exit channel and is ejected upon the initial RNA synthesis (Zhang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2020). Most bacterial promoters recognized by group 1 and 2 σ subunits belong to the −10/−35 class and contain the −10 and also the −35 elements. The extended −10 class of promoters (∼20% in E. coli) contains the extended −10 motif (T–17R–16T–15G–14; R = purine) that is located one base upstream of the −10 element (Keilty and Rosenberg, 1987; Burr et al., 2000; Mitchell et al., 2003) and interacts with the σ3 domain (Barne et al., 1997) (Figure 1B). It has been shown that the extended −10 motif bypasses the requirement of the σ4/−35 element interaction (Kumar et al., 1993). However, σ4 per se is essential for transcription initiation by σB-MtbRNAP at the extended −10 promoters (Perumal et al., 2018).

FIGURE 1.

The RNAP-binding σ-regulators and their interaction with RNAP. (A) Scheme of the main steps in transcription initiation. The steps regulated by RNAP-binding transcription factors (RPB-TFs) and DNA-binding transcription factors (DB-TFs) are indicated. (B) Basal promoter architecture (first described in E. coli) and interaction of its key elements with σ-domains. (C) Domain organization of the principal σ subunits and RbpA. NCR – non-conserved region, NTT – N-terminal tail, RCD – RbpA core domain, BL – basic linker, SID – σ-interacting domain. Alignment of the σ subunits from E. coli (Eco), M. tuberculosis (Mtb), C. crescentus (Ccr), C. trachomatis (Ctr), and T. thermophilus (Tth). Amino acid residues implicated in contacts with activators (bottom) are shown in color. (D) Schematic presentation of the RNAP holoenzyme structure with the binding sites for the activators and repressors targeting domains σ2 and σ4, respectively.

As a general rule, the principal σ subunit, the cellular concentration of which exceeds that of core RNAP (Gaal et al., 2006) should recognize and bind to promoter DNA only in the context of RNAP holoenzyme. Free σ should be devoid of DNA binding activity that might inhibit transcription. Data from structural and biophysical studies suggest that free group 1 and 2 σ subunits adopt a “closed” inactive conformation in which the spatial arrangement of domains σ2 and σ4 is incompatible with promoter DNA binding. Binding to core RNAP induces or stabilizes an “open,” active σ conformation, optimal for promoter binding (Callaci et al., 1999; Schwartz et al., 2008; Vishwakarma et al., 2018). Canonically, RNAP activity at promoters is regulated through DNA-binding transcription factors (Browning and Busby, 2016) that recognize and bind to specific motifs on dsDNA (DB-TFs) and influence the initiation pathway steps after promoter binding (Figure 1A). A number of proteins, called σ-regulators in this review, have evolved to tune the structure of the σ/core RNAP interaction, thus altering RNAP promoter selectivity and activity globally. These RNAP-binding transcription factors (RPB-TFs) bind to RNAP before the RNAP-promoter complex formation upon RNAP assembly. Consequently, RPB-TFs can influence all the ensuing steps of initiation and in some cases, also elongation and termination (Figures 1A,D). These proteins can be divided in two groups: (1) σ-activators (RbpA, Crl, GcrA, and GrgA) that target the σ2 domain and consequently its interaction with the −10 element, and (2) σ-repressors (Gp39, AsiA, P7, and Scc4) that target the σ4 domain and consequently its interaction with −35 element (Table 1). All σ-repressor, but one, are phage-encoded proteins that appropriate the host transcriptional machinery during infection (Tabib-Salazar et al., 2019).

TABLE 1.

Properties of the RNAP-binding σ-regulators.

| Name | Phylum/organism | Targeted σ | Binding site | DNA interaction | Regulated process | Mode of action | Structures/PDB code |

| σ-activators | |||||||

| RbpA | Actinobacteria/Mycobacterium tuberculosis | σA, σB | σ2, β′−clamp/RNA−exit channel | Nonspecific | •Growth •Stress response •Stationary phase |

σ–RNAP assembly (chaperon); Stimulates RPo formation; Stimulates promoter escape | RbpA–σA-RPo/6C04, 5TW1, 5VI5; RbpA-σA-RNAP/6C05 |

| Crl | γ-Proteobacteria/Escherichia coli | σS | σ2/β′−CT | No | •Stress response •Stationary phase |

σ–RNAP assembly (chaperon); Stimulates RPo formation | Crl–ITC5/6KJ6; Crl–RPo/6OMF |

| GcrA | α–Proteobacteri/Caulobacter crescentus | σA | σ2 | Methylated DNA (m6A) | •Cell cycle | Stimulates RPo formation at methylated promoters | GcrA-σA/5YIX |

| GrgA | Chlamydiae/Chlamydia trachomatis | σA, σ28 | σ2 | Nonspecific | Unknown | Activates transcription initiation | – |

| σ-repressors | |||||||

| Scc4 (CT663) | Chlamydiae/Chlamydia trachomatis | σA | σ4/β-FLAP | No | • Growth • Infection |

Inhibits transcription initiation at −10/−35 promoters (likely by σ4 displacement) | – |

| Gp39 | Deinococcus-Thermus/Thermus thermophilus Phage P23-45 | σA | σ4/β-FLAP | No | •Phage transcription | Inhibits RPo formation by σ4 displacement; Stimulates elongation. Anti-terminator function | RNAP-Gp39/3WOD |

| AsiA | γ-Proteobacteria/Escherichia coli Phage T4 | σ70 | σ4/β-FLAP | Nonspecific | •Phage transcription | Inhibits host RPo formation by σ4 appropriation (σ4 displacement); Stimulates phage RPo formation | RPo-AsiA-MotA/6K4Y |

| P7 | γ-Proteobacteria/Xanthomonas oryzae Phage Xp10 | No | β′−NTD/β–FLAP/RNA–exit channel | Unknown | •Phage transcription | Inhibits RPo formation by σ4 displacement; Stimulates elongation; Anti–terminator function | P7–TEC/6J9F |

Activators Targeting the σ2 Domain

RbpA

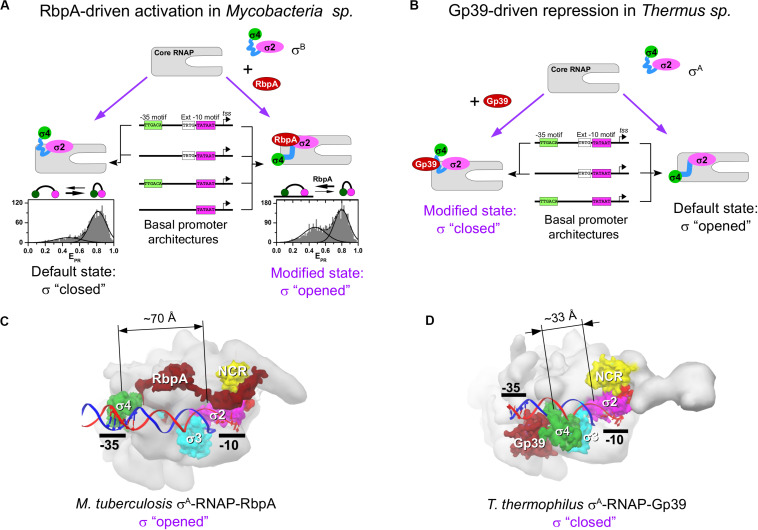

RbpA is a ∼14-kDa protein specific to Actinomycetes sp. RbpA was discovered in Streptomyces coelicolor as a protein that is associated with the RNAP holoenzyme (Paget et al., 2001) and is required for rapid growth and confers basal levels of rifampicin resistance (Newell et al., 2006). Later studies in Mtb described RbpA as a σ-specific transcriptional activator implicated in the stress response (Hu et al., 2012, 2014) and essential for growth (Forti et al., 2011). RbpA binds to group 1 and group 2 σ subunits (σA and σB in Mtb;σHrdB and σHrdA in S. coelicolor), but not to group 3 and group 4 σ subunits (Bortoluzzi et al., 2013; Tabib-Salazar et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2014). RbpA exerts multiple effects on transcription initiation. It stabilizes σ interaction with core MtbRNAP, promotes DNA melting, stabilizes RPo, and accelerates promoter escape (Hu et al., 2012, 2014; Perumal et al., 2018). However, a recent study on the σA-MtbRNAP holoenzyme suggests that RbpA inhibits promoter escape (Jensen et al., 2019). This discrepancy indicates that RbpA effect on transcription might be promoter-specific. RbpA structure comprises an unstructured N-terminal tail (NTT), a central RbpA core domain (RCD), and a C-terminal region called the σ-interacting domain (SID) (Figure 1C). RCD and SID are connected by a flexible loop called the basic linker (BL) (Bortoluzzi et al., 2013; Tabib-Salazar et al., 2013; Hubin et al., 2015). RbpA interacts with σ2 via its SID, whereas BL (R79) interacts with promoter DNA upstream of the −10 element (Hubin et al., 2017). RbpA-SID interacts with three σ2 regions: NCR, 1.2, and 2.3 (Figure 1C). RbpA tethers σA to core RNAP via the β′-Zinc–binding domain (Hubin et al., 2015, 2017). Recent cryo-EM structures of Mtb RPo (Figure 2C) showed that RbpA-NTT threads through the RNA exit channel into the active site cleft and interacts with the 3.2 region of σA and the DNA template strand at position −5 (Boyaci et al., 2019). However, RbpA-SID is sufficient for partial transcription activation (Hubin et al., 2015). The complex network of interactions between RbpA and key structural modules of RNAP explains why RbpA affects different steps of initiation, from RPo formation to promoter escape. Recent single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (smFRET) study showed that Mtb σB adopts a closed, inactive conformation (∼50 Å distance between σ2 and σ4) even after assembly of the σB-RNAP holoenzyme (Vishwakarma et al., 2018). During holoenzyme assembly, RbpA stabilizes (or induces) the open conformation of σB (∼83 Å distance between σ2 and σ4), required for its tight binding to core MtbRNAP and to promoter DNA (Figure 2A). Thus, RbpA acts as a chaperone to promote holoenzyme formation. This finding suggests that in the absence of RbpA, part of the σ-core RNAP interface cannot be formed, thus explaining the low stability of the σA and σB MtbRNAP holoenzymes (Hu et al., 2012, 2014). On the basis of the high structural similarity between σA and σB we propose that the same activation mechanism works also for σA. This conclusion is supported by the cryo-EM structure of Mycobacterium smegmatisσA-RNAP holoenzyme lacking electron density for the domain σ4. This indicates that σ fluctuates between different conformational states (Kouba et al., 2019). The smFRET study on σB-MtbRNAP also explains why RbpA is essential for transcription initiation at the −10/−35 promoters and dispensable at the extended −10 promoters (Hu et al., 2012, 2014; Perumal et al., 2018). Indeed, RPo formation at the −10/−35 promoters requires the distance between domains σ2 and σ4 to match the distance between the −10 and −35 elements. This condition is dispensable for RPo formation at the extended −10 promoter. Therefore, regulation of the σ conformational state by RbpA allows modulating RNAP promoter selectivity (Perumal et al., 2018).

FIGURE 2.

Regulation of the σ subunit conformational states by RbpA and Gp39. (A) Model representing the mechanism of RbpA–driven transcription activation in Mycobacteria sp. At the bottom, the histograms show the smFRET efficiencies (EPR) distributions for the double–labeled σB subunit in the RNAP holoenzyme without (left) and with RbpA (right) (data from Vishwakarma et al., 2018). (B) Model representing the mechanism of gp39-driven transcription repression in T. thermophilus. (C) Structure of the MtbRNAP-σA RPo in complex with RbpA [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code: 6EDT]. (D) Structure of the Tht RNAP-σA RPo in complex with gp39 [Protein Data Bank (PDB) code: 3WOD]. The dimension lines show distances between Cα atoms of homologous residues in domain σ2 (Mtb T356, Tht N248) and domain σ4 (Mtb G497, Tht G391).

Crl

Crl is a ∼16-kDa protein from γ-proteobacteria, initially identified in E. coli as an activator of genes implicated in curli fimbriae production (Arnqvist et al., 1992). Crl binds to stationary phase σS and activates σS-RNAP-mediated transcription, independently of the promoter sequence (Pratt and Silhavy, 1998; Bougdour et al., 2004). Although Crl does not bind to σ70 because of the steric clash with σ70-NCR (Cartagena et al., 2019) it can activate σ70-dependent transcription (Gaal et al., 2006). As observed for RbpA, Crl facilitates transcription initiation by stabilizing the σS-RNAP holoenzyme and stimulating RPo formation (Banta et al., 2013; Xu et al., 2019). Two high resolution cryo-EM-based structures of Crl-σS-RNAP RPo have been recently described (Cartagena et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019). Cartagena et al., suggested that Crl stabilizes σS-RNAP by tethering σS directly to RNAP though contacts with the β′-clamp-toe domain (β′–CT, residues 144–179). Based on structure and hydrogen–deuterium exchange mass spectrometry analysis of σS conformation, Xu et al. (2019) suggested that Crl acts as a chaperone that facilitates the σS-RNAP holoenzyme assembly mainly by modifying σ2 conformation, but not through its contacts with the β′-clamp (Figure 1C) stabilizes its optimal conformation for binding to the −10 element ssDNA. This interaction promotes RPo formation. It is not known whether Crl plays any role in promoter escape. However, the finding that the β′CT/σ70-NCR interaction antagonizes the σ2/β′ clamp interaction and facilitaes promoter escape Leibman and Hochschild, 2007) suggests this possibility (Banta et al., 2013; Cartagena et al., 2019).

GcrA

GcrA (173–aa) is a transcription factor from Caulobacter crescentus that is well conserved in α–proteobacteria. GcrA forms a stable complex with σA-RNAP, recruits RNAP to methylated (m6A) promoters, and activates the expression of ∼200 genes that play an important role in cell cycle regulation during swarmer-to-stalked cell transition (Holtzendorff et al., 2004; Haakonsen et al., 2015). Analysis of the promoter binding kinetics demonstrated that GcrA increases RNAP affinity for the promoter and the rate of RPc isomerization to RPo (Haakonsen et al., 2015). GcrA is composed of two domains: the N-terminal DNA-binding domain (GcrA-DBD, residues 1–45) that recognizes methylated promoter DNA, and the C-terminal σ-interacting domain (GcrA-SID, residues 108–173) that binds to σ2 (Figure 1C). GcrA-DBD and GcrA-SID are connected by an unstructured linker (residues 46–107). Recent crystal structures of the GcrA-SID-σA complex and the GcrA-DBD-DNA complex revealed details of its interactions with RNAP and the promoter (Wu et al., 2018). Structural studies on the full length protein and its complex with RNAP are now needed to decipher GcrA mechanism of action.

GrgA

GrgA (ORF CTL0766, 288-aa) is a transcription factor from the human pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. GrgA activates σA- (also known as σ66) and σ28-dependent transcription by interacting with σ-NCR and binding to DNA in a non-sequence-specific manner (Bao et al., 2012; Desai et al., 2018). The GrgA binding site on σA was mapped to residues 269–316 (Bao et al., 2012) (Figure 1C). The detailed mechanism of GrgA action and its role in gene regulation remain obscure. GrgA is specific to Chlamydia species, and has not been found in any other organism. Therefore, it might be a good target for developing highly selective anti-chlamydial drugs (Zhang et al., 2019).

Repressors Targeting the σ4 Domain

Gp39 of Phage P23-45

Gp39, a ∼16-kDa protein encoded by the Thermus thermophilus phage P23-45, binds to the host σA-RNAP holoenzyme and inhibits transcription from −10/−35 class promoters. Transcription of the middle and late promoters of P23-45, which belong to the extended −10 class, is less affected (Berdygulova et al., 2011; Tagami et al., 2014). Gp39 blocks transcription initiation probably at the step of RPc formation that depends on the σ4/−35 element contact. Besides its effect on initiation, gp39 also displays anti-termination activity (Berdygulova et al., 2012) suggesting that the σ subunit is not essential for its binding to RNAP. The crystal structure of the σA-RNAP-gp39 complex (Tagami et al., 2014) reveled that gp39 binds to the RNAP β-flap and to the σ4 domain and induces a ∼45 Å displacement of the σ4 relative to its default position in the RNAP holoenzyme (Figures 2B,D). This conformational change in the σA subunit explains the selectivity of the RNAP-gp39 complex toward the extended −10 promoters.

AsiA of Phage T4

AsiA is 90-aa protein of the E. coli phage T4. AsiA employs a mechanism called σ appropriation to reprogram the host RNAP. AsiA forms a stable complex with σ70 before holoenzyme assembly (Hinton et al., 1996; Hinton and Vuthoori, 2000) and thus inhibits transcription from the −10/−35 class promoters. Conversely, transcription from the extended −10 promoters is less affected (Severinovaa et al., 1998). At the same time, AsiA acts as a co-activator of the phage activator protein MotA, required for binding to the T4 middle promoter. The σ appropriation complex, which includes σ70, RNAP, AsiA and MotA, recognizes the MotA-box that replaces the −35 element at the T4 middle promoters. NMR solution structures of the AsiA-σ4 complex demonstrated that AsiA remodels σ4 making impossible its binding to the −35 element and its interaction with β-flap (Simeonov et al., 2003; Lambert et al., 2004). A recent cryo-EM structure of the σ70-RNAP-AsiA-MotA RPo revealed the detailed mechanism of σ appropriation (Shi et al., 2019). AsiA binds to and remodels the structure of the σ region 3.2 and σ4, displaces σ4, and takes its place. This allows MotA recruitment and RPo formation. In addition, AsiA interaction with upstream dsDNA stabilizes RPo.

P7 of Phage Xp10

P7 is a small, ∼ 8-kDa, globular protein encoded by the lytic bacteriophage Xp10 that infects the Gram-negative bacterium Xanthomonas oryzae, which causes rice blight. At a later stage of infection, P7 shuts off the host gene transcription in favor of phage gene transcription by the Xp10 single-subunit RNAP (Nechaev et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2014). P7 forms a stable complex with the host σ70-RNAP holoenzyme and inhibits RPo formation at −10/−35 promoters and to a lesser extent, at the extended −10 promoters. Luminescence resonance energy transfer (LRET) measurements demonstrated that in the P7-σ70-RNAP complex, the σ70 subunit adopts a closed or partially closed conformation (Nechaev et al., 2002). The finding that P7 also binds to RNAP harboring the structurally distinct σ54 (Brown et al., 2016) suggests that the σ subunit is not essential for its interaction with RNAP. Indeed, P7 can also modulate post-initiation steps of transcription, such as pausing and intrinsic termination (Nechaev et al., 2002; Zenkin et al., 2015,You et al., 2019). A recently solved cryo-EM structure of P7 in the elongation complex (You et al., 2019) reveled that P7 binds to the RNA-exit channel at the place of σ4, and thus makes impossible the formation of the “open” σ conformation essential for RPo formation at −10/−35 class promoters. The lack of σ4-RNAP contact should decrease the overall stability of the holoenzyme, thus explaining the dissociation of σ from the P7-RNAP complex observed in biochemical experiments (Liu et al., 2014). It has been proposed that P7 induces the closed conformation of the RNAP clamp, and thus inhibits RPo formation (You et al., 2019). However, it is unlikely that such mechanism takes place at −10/−35 promoters. Indeed, according to the P7-RNAP complex structure, P7 should inhibit the interaction of σ4 with the −35 element, which is required for initial RNAP binding to the promoter (RPc formation). Clamp closing starts to play a role during RPc isomerization to RPo, the step following recognition of the −35 element. Thus, it is more likely that P7-mediated σ70 remodeling inhibits the σ4/−35 element interaction and consequently RPc formation, as observed for the σ54-RNAP holoenzyme (Brown et al., 2016). However, P7-induced clamp closing might play a role when the −35 element recognition is bypassed.

Scc4 (CT663) From Chlamydia trachomatis

Scc4 (ORF CT663) is a ∼15-kDa protein from the human pathogen C. trachomatis. Scc4 forms a heterodimer with Scc1, and both are type III secretion chaperons implicated in the regulation of cell growth and intracellular infection (Hanson et al., 2015). Scc4 was identified in a two-hybrid screen for regulators that interact with C. trachomatis RNAP β-FLAP (Rao et al., 2009). Scc4 binds to RNAP β-FLAP tip helix and also interacts with the σ4 domain of the principal σA subunit. It can also interact with the σ4 domain of E. coli σ70 that exhibits 60% amino acid identity with the σ4 of σA, but does not interact with the σ4 of C. trachomatis σ28 (Group 3). Scc4 inhibits transcription initiation from −10/−35 class promoters, but not from extended −10 type promoters. Although structural studies are needed to determine the mechanism of inhibition, on the basis of similarities with the mechanism of action of the phage proteins we hypothesize that Scc4 disrupts the σ4/Flap interaction and prevents RPo formation at −10/−35 promoters.

Conclusion

We can draw two basic principles of transcription regulation by RPB-TFs: positive regulation through strengthening of σ2/β′10 element interactions, and negative regulation through weakening of σ4/β-flap/−35 element interactions. All contacts made by the three σ-activators RbpA, Crl and GcrA overlap and are clustered in four σ regions (σ1.2, σ-NCR, σ2.1 and σ2.3) that are responsible for core RNAP binding and −10 element recognition/melting (Figure 1C). Consequently, all these activators act through a similar mechanism. They strengthen σ/RNAP interaction and stimulate RPo formation, the rate limiting step in transcription initiation. The only exception is GrgA the binding site of which was mapped entirely to σ NCR and thus may have a different mechanism of action. However, in the absence of a detailed biochemical and structural characterization, it cannot be excluded that GrgA contacts other regions besides σ-NCR.

At least for RbpA, the stimulation of the “closed-to-open” transition is part of the σ activation mechanism required for efficient transcription initiation at the −10/−35 class promoters, but not at the extended −10 class promoters (Vishwakarma et al., 2018). It remains to be explored whether Crl, GcrA and GrgA can affect the relative movement of the σ2 and σ4 domains. Remarkably, all σ-repressors mentioned here act as antagonists to RbpA-type activation by destabilizing the σ4/β-flap interaction, and should favor the “open-to-closed” transition in the σ subunit. Consequently, σ-repressor-modified RNAP cannot initiate transcription at the −10/−35 class promoters, but only at the extended −10 class promoters (Figure 2A,B).

The σ-activators and σ-repressors illustrate how σ conformational dynamics, controlled by contacts with core RNAP, can be used for fine-tuning transcription in a lineage-specific manner. Considering the huge diversity in lifestyles of bacterial species, the number of the currently known σ-regulators of bacterial origin is strikingly low. The reason might be that most of these proteins are of small size and are not easy to detect. Yet, their discovery in pathogenic bacteria may offer new targets for developing pathogen-specific drugs. We expect that the number of the described σ-regulators and the diversity of regulatory mechanisms will continue to grow.

Author Contributions

KB and RV wrote the manuscript. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the grant from the French National Research Agency [MycoMaster ANR-16-CE11-0025-01].

References

- Arnqvist A., Olsén A., Pfeifer J., Russell D. G., Normark S. (1992). The Crl protein activates cryptic genes for curli formation and fibronectin binding in Escherichia coli HB101. Mol. Microbiol. 6 2443–2452. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01420.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banta A. B., Chumanov R. S., Yuan A. H., Lin H., Campbell E. A., Burgess R. R., et al. (2013). Key features of σS required for specific recognition by Crl, a transcription factor promoting assembly of RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 15955–16960. 10.1073/pnas.1311642110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X., Nickels B. E., Fan H. (2012). Chlamydia trachomatis protein GrgA activates transcription by contacting the nonconserved region of σ66. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109 16870–16875. 10.1073/pnas.1207300109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barne K. A., Bown J. A., Busby S. J., Minchin S. D. (1997). Region 2.5 of the Escherichia coli RNA polymerase σ70 subunit is responsible for the recognition of the ‘extended-10’ motif at promoters. EMBO J. 16 4034–4040. 10.1093/emboj/16.13.4034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdygulova Z., Esyunina D., Miropolskaya N., Mukhamedyarov D., Kuznedelov K., Nickels B. E., et al. (2012). A novel phage-encoded transcription antiterminator acts by suppressing bacterial RNA polymerase pausing. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 4052–4063. 10.1093/nar/gkr1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdygulova Z., Westblade L. F., Florens L., Koonin E. V., Chait B. T., Ramanculov E. (2011). Temporal regulation of gene expression of the Thermus thermophilus bacteriophage P23-45. J. Mol. Biol. 405 125–142. 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.10.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bortoluzzi A., Muskett F. W., Ross W., Gourse R. L., Campbell E. A., Waters L. C., et al. (2013). Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA polymerase-binding protein A (RbpA) and its interactions with sigma factors. J. Biol. Chem. 288 14438–14450. 10.1074/jbc.M113.459883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bougdour A., Lelong C., Geiselmann J. (2004). Crl, a low temperature-induced protein in Escherichia coli that binds directly to the stationary phase sigma subunit of RNA polymerase. J. Biol. Chem. 279 19540–19550. 10.1074/jbc.M314145200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyaci H., Chen J., Jansen R., Darst S. A., Campbell E. A. (2019). Structures of an RNA polymerase promoter melting intermediate elucidate DNA unwinding. Nature 565 382–385. 10.1038/s41586-018-0840-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. R., Sheppard C. M., Burchell L., Matthews S., Wigneshweraraj S. (2016). The Xp10 bacteriophage protein P7 inhibits transcription by the major and major variant forms of the host RNA polymerase via a common mechanism. J. Mol. Biol. 428 3911–3919. 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning D. F., Busby S. J. W. (2016). Local and global regulation of transcription initiation in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 14 638–650. 10.1038/nrmicro.2016.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buc H., McClure W. R. (1985). Kinetics of open complex formation between Escherichia coli RNA polymerase and the lac UV5 promoter. Evidence for a sequential mechanism involving three steps. Biochemistry 24 2712–2723. 10.1021/bi00332a018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burr T., Mitchell J., Kolb A., Minchin S., Busbya S. (2000). DNA sequence elements located immediately upstream of the −10 hexamer in Escherichia coli promoters: a systematic study. Nucleic Acids Res. 28 1864–1870. 10.1093/nar/28.9.1864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaci S., Heyduk E., Heyduk T. (1999). Core RNA polymerase from E. coli induces a major change in the domain arrangement of the σ70 subunit. Mol. Cell 3 229–238. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80313-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartagena A. J., Banta A. B., Sathyan N., Ross W., Gourse R. L., Campbell E. A., et al. (2019). Structural basis for transcription activation by Crl through tethering of σS and RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 116 18923–18927. 10.1073/pnas.1910827116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cortes T., Schubert O. T., Rose G., Arnvig K. B., Comas I., Aebersold R., et al. (2014). Genome-wide mapping of transcriptional start sites defines an extensive leaderless transcriptome in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Cell Rep. 5 1121–1131. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai M., Wurihan W., Di R., Fondell J. D., Nickels B. E., Bao X., et al. (2018). A role for GrgA in regulation of σ28 dependent transcription in the obligate intracellular bacterial pathogen Chlamydia trachomatis. J. Bacteriol. 200:e00298-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feklistov A., Darst S. A. (2011). Structural basis for promoter −10 element recognition by the bacterial RNA polymerase σ subunit. Cell 147 1257–1269. 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feklistov A., Sharon B. D., Darst S. A., Gross C. A. (2014). Bacterial sigma factors: a historical, structural, and genomic perspective. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 68 357–376. 10.1146/annurev-micro-092412-155737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forti F., Mauri V., Deho G., Ghisotti D. (2011). Isolation of conditional expression mutants in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by transposon mutagenesis. Tuberculosis 91 569–578. 10.1016/j.tube.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaal T., Mandel M. J., Silhavy T. J., Gourse R. L. (2006). Crl facilitates RNA polymerase holoenzyme formation. J. Bacteriol. 188 7966–7970. 10.1128/jb.01266-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber T. M., Gross C. A. (2003). Multiple sigma subunits and the partitioning of bacterial transcription space. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 57 441–466. 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haakonsen D. L., Yuan A. H., Laub M. T. (2015). The bacterial cell cycle regulator GcrA is a σ70 cofactor that drives gene expression from a subset of methylated promoters. Genes Dev. 29 2272–2286. 10.1101/gad.270660.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson B. R., Slepenkin A., Peterson E. M., Tan M. (2015). Chlamydia trachomatis type III secretion proteins regulate transcription. J. Bacteriol. 197 3238–3244. 10.1128/jb.00379-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton D. M., Amegadzie R. M., Gerber J. S., Sharma M. (1996). Bacteriophage T4 middle transcription system: T4-modified RNA polymerase; AsiA, a σ70 binding protein; and transcriptional activator MotA. Methods Enzymol. 274 43–57. 10.1016/s0076-6879(96)74007-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton D. M., Vuthoori S. (2000). Efficient inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by the bacteriophage T4 AsiA protein requires that AsiA binds first to free σ70. J. Mol. Biol. 304 731–739. 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtzendorff J., Hung D., Brende P., Reisenauer A., Viollier P. H., McAdams H. H., et al. (2004). Oscillating global regulators control the genetic circuit driving a bacterial cell cycle. Science 304 983–987. 10.1126/science.1095191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Morichaud Z., Chen S., Leonetti J. P., Brodolin K. (2012). Mycobacterium tuberculosis RbpA protein is a new type of transcriptional activator that stabilizes the σA-containing RNA polymerase holoenzyme. Nucleic Acids Res. 40 6547–6557. 10.1093/nar/gks346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y., Morichaud Z., Perumal A. S., Roquet-Baneres F., Brodolin K. (2014). Mycobacterium RbpA cooperates with the stress-response σB subunit of RNA polymerase in promoter DNA unwinding. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 10399–10408. 10.1093/nar/gku742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubin E. A., Fay A., Xu C., Bean J. M., Saecker R. M., Glickman M. S., et al. (2017). Structure and function of the mycobacterial transcription initiation complex with the essential regulator RbpA. eLife 6:e22520. 10.7554/eLife.22520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubin E. A., Tabib-Salazar A., Humphrey L. J., Flack J. E., Olinares P. D. B., Darst S. A., et al. (2015). Structural, functional, and genetic analyses of the actinobacterial transcription factor RbpA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112 7171–7176. 10.1073/pnas.1504942112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen D., Manzano A. R., Rammohan J., Stallings C. L., Galburt E. A. (2019). CarD and RbpA modify the kinetics of initial transcription and slow promoter escape of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 13 6685–6698. 10.1093/nar/gkz449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilty S., Rosenberg M. (1987). Constitutive function of a positively regulated promoter reveals new sequences essential for activity. J. Biol. Chem. 262 6389–6395. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouba T., Pospíšil J., Hnilicová J., Šanderová H., Barvík I., Krásnı L. (2019). The core and holoenzyme forms of RNA polymerase from Mycobacterium smegmatis. J. Bacteriol. 201:e00583-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A., Malloch R. A., Fujita N., Smillie D. A., Ishihama A., Hayward R. S. (1993). The minus 35-recognition region of Escherichia coli sigma 70 is inessential for initiation of transcription at an “extended minus 10” promoter. J. Mol. Biol. 232 406–418. 10.1006/jmbi.1993.1400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert L. J., Wei Y., Schirf V., Demeler B., Werner M. H. (2004). T4 AsiA blocks DNA recognition by remodeling σ70 region 4. EMBO J. 23 2952–2962. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600312 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibman M., Hochschild A. (2007). A σ-core interaction of the RNA polymerase holoenzyme that enhances promoter escape. EMBO J. 26 1579–1590. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L., Molodtsov V., Lin W., Ebright R. H., Zhang Y. (2020). RNA extension drives a stepwise displacement of an initiation-factor structural module in initial transcription. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 117 5801–5809. 10.1073/pnas.1920747117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B., Shadrin A., Sheppard C., Mekler V., Xu Y., Severinov K., et al. (2014). A bacteriophage transcription regulator inhibits bacterial transcription initiation by σ-factor displacement. Nucleic Acids Res. 42 4294–4305. 10.1093/nar/gku080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J. E., Zheng D., Busby S. J. W., Minchin S. D. (2003). Identification and analysis of ‘extended −10′ promoters in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 31 4689–4695. 10.1093/nar/gkg694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morichaud Z., Chaloin L., Brodolin K. (2016). Regions 1.2 and 3.2 of the RNA polymerase σ subunit promote DNA melting and attenuate action of the antibiotic lipiarmycin. J. Mol. Biol. 428 463–476. 10.1016/j.jmb.2015.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan A., Vago F. S., Li K., Qayyum M. Z., Yernool D., Jiang W., et al. (2018). Cryo-EM structure of Escherichia coli σ70 RNA polymerase and promoter DNA complex revealed a role of σ non-conserved region during the open complex formation. J. Biol. Chem. 293 7367–7375. 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nechaev S., Yuzenkova Y., Niedziela-Majka A., Heyduk T., Severinov K. (2002). A novel bacteriophage-encoded RNA polymerase binding protein inhibits transcription initiation and abolishes transcription termination by host RNA polymerase. J. Mol. Biol. 320 11–22. 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00420-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell K. V., Thomas D. P., Brekasis D., et al. (2006). The RNA polymerase-binding protein RbpA confers basal levels of rifampicin resistance on Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol. Microbiol. 60 687–696. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05116.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Österberg S., del Peso-Santos T., Shingler V. (2011). Regulation of alternative sigma factor use. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 65 37–55. 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paget M. S., Molle V., Cohen G., Aharonowitz Y., Buttner M. J. (2001). Defining the disulphide stress response in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2): identification of the σR regulon. Mol. Microbiol. 42 1007–1020. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02675.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perumal A. S., Vishwakarma R. K., Hu Y., Morichaud Z., Brodolin K. (2018). RbpA relaxes promoter selectivity of M. tuberculosis RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 10106–10118. 10.1093/nar/gky714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pratt L. A., Silhavy T. J. (1998). Crl stimulates RpoS activity during stationary phase. Mol. Microbiol. 29 1225–1236. 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao X., Deighan P., Hua Z., Hu X., Wang J., Luo M., et al. (2009). A regulator from Chlamydia trachomatis modulates the activity of RNA polymerase through direct interaction with the β subunit and the primary σ subunit. Genes Dev. 23 1818–1829. 10.1101/gad.1784009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigue S., Provvedi R., Jacques P., Gaudreau L., Manganelli R. (2006). The σ factors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 30 926–941. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00040.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saecker R. M., Record M. T., deHaseth P. L. (2011). Mechanism of bacterial transcription initiation: RNA polymerase - promoter binding, isomerization to initiation-competent open complexes, and initiation of RNA synthesis. J. Mol. Biol. 412 754–771. 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.01.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz E. C., Shekhtman A., Dutta K., Pratt M. R., Cowburn D., Darst S., et al. (2008). A full-length group 1 bacterial sigma factor adopts a compact structure incompatible with DNA binding. Chem. Biol. 15 1091–1103. 10.1016/j.chembiol.2008.09.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severinovaa E., Severinova K., Darst S. A. (1998). Inhibition of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase by bacteriophage T4 AsiA. J. Mol. Biol. 279 9–18. 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1742 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Wen A., Zhao M., You L., Zhang Y., Feng Y. (2019). Structural basis of σ appropriation. Nucleic Acids Res. 47 9423–9432. 10.1093/nar/gkz682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simeonov M. F., Bieber Urbauer R. J., Gilmore J. M., Adelman K., Brody E. N., Niedziela-Majka A., et al. (2003). Characterization of the interactions between the bacteriophage T4 AsiA protein and RNA polymerase. Biochemistry 42 7717–7726. 10.1021/bi0340797 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabib-Salazar A., Liu B., Doughty P., Lewis R. A., Ghosh S., Parsy M.-L., et al. (2013). The actinobacterial transcription factor RbpA binds to the principal sigma subunit of RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 41 5679–5691. 10.1093/nar/gkt277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabib-Salazar A., Mulvenna N., Severinov K., Matthews S. J., Wigneshweraraj S. (2019). Xenogeneic regulation of the bacterial transcription machinery. J. Mol. Biol. 431 4078–4092. 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami S., Sekine S., Minakhin L., Esyunina D., Akasaka R., Shirouzu M., et al. (2014). Structural basis for promoter specificity switching of RNA polymerase by a phage factor. Genes Dev. 28 521–531. 10.1101/gad.233916.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vishwakarma R. K., Cao A. M., Morichaud Z., Perumal A. S., Margeat E., Brodolin K. (2018). Single-molecule analysis reveals the mechanism of transcription activation in M. tuberculosis. Sci. Adv. 4:eaao5498. 10.1126/sciadv.aao5498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Haakonsen D. L., Sanderlin A. G., Liu Y. J., Shen L., Zhuang N., et al. (2018). Structural insights into the unique mechanism of transcription activation by Caulobacter crescentus GcrA. Nucleic Acids Res. 46 3245–3256. 10.1093/nar/gky161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu J., Cui K., Shen L., Shi J., Li L., You L., et al. (2019). Crl activates transcription by stabilizing active conformation of the master stress transcription initiation factor. eLife 8:e50928. 10.7554/eLife.50928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- You L., Shi J., Shen L., Li L., Fang C., Yu C., et al. (2019). Structural basis for transcription antitermination at bacterial intrinsic terminator. Nat. Commun. 10:3048. 10.1038/s41467-019-10955-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenkin N., Kulbachinskiy A., Yuzenkova Y., Mustaev A., Bass I., Severinov K., et al. (2007). Region 1.2 of the RNA polymerase σ subunit controls recognition of the −10 promoter element. EMBO J. 26 955–964. 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zenkin N., Severinov K., Yuzenkova Y. (2015). Bacteriophage Xp10 anti-termination factor p7 induces forward translocation by host RNA polymerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 43 6299–6308. 10.1093/nar/gkv586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H., Vellappan S., Tang M. M., Bao X., Fan H. (2019). GrgA as a potential target of selective antichlamydials. PLoS One 14:e0212874. 10.1371/journal.pone.0212874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Feng Y., Chatterjee S., Tuske S., Ho M. X., Arnold E., et al. (2012). Structural basis of transcription initiation. Science 338 1076–1080. 10.1126/science.1227786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuo Y., Steitz T. A. (2015). Crystal structures of the E. coli transcription initiation complexes with a complete bubble. Mol. Cell 58 534–540. 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]