Abstract

The corona pandemic is an opportunity to rethink and revamp the academic career and reward system that consistently disadvantages parenting scientists and women.

Subject Categories: S&S: Careers & Training, S&S: Ethics

The current COVID‐19 pandemic constitutes a “stress test” for our knowledge‐based society and presents a threat to the diversity and quality of our research communities. But this situation only highlights and exacerbates the long‐existing and festering challenges and disadvantages experienced by parenting researchers. It is therefore an opportunity to address these problems now and overhaul the entire academic system before the pandemic subsides, and we return to the old state of affairs.

“…we trust that you will think about how you can turn this set‐back into an opportunity.” I (HJ Wieden) think that we have all received similar emails during the past couple of weeks. However, this particular one has resonated deeper and made me realize that I, indeed, had not thought about the potential opportunities that the COVID‐19 pandemic might offer. This is particularly shocking as I thought I was fairly good at spotting an opportunity. I just recently turned 50; was I losing my edge? I then realized that this was likely due to the fact that my partner (Ute Kothe, also a principal investigator) and I were simply too busy juggling all our new responsibilities emerging from the COVID‐19 pandemic including childcare, home schooling, closing our laboratories, and supervising graduate students (including Luc Roberts) (Fig 1).

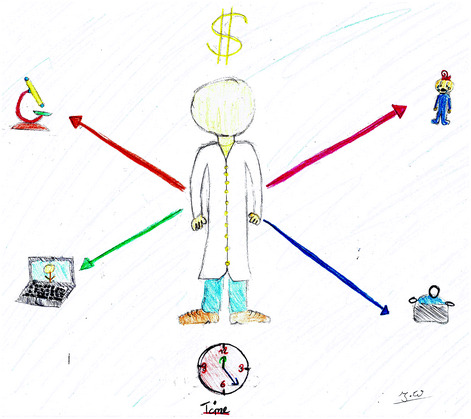

Figure 1. The fate and chores of parenting scientists as seen by their children. © Johanna Wieden.

This email and COVID‐19 has re‐illuminated often‐forgotten, but long‐existing disadvantages that parenting and caregiving researchers face during their entire careers and which are now amplified by the loss of childcare and school closures. How we will deal with this situation will define the character of our research community: do we reward only the most productive ones or do we embrace anyone who genuinely conducts quality research? It has also made visible the urgent need to think about how we will cope with the COVID‐19 pandemic and our “new normal” while keeping and supporting the best minds in science. How can we avoid deepening the existing invisible divide between actively parenting/caregiving researchers and their peers who do not have to take care of children?

“It is work from home and not a vacation.” While the sender was probably not intentionally malicious, frustration filled me as I (Luc Roberts) read the words informing me that a global health pandemic was no excuse to be unproductive. The email reminded me that I had made almost no progress on my thesis since COVID‐19 and that was not likely to change. I'm a PhD candidate nearing the end of my degree, a husband to a front‐line medical worker (registered nurse), and a father to a toddler. The delicate balance that enabled me to be an active researcher and parent has been uprooted by COVID‐19 and the accompanying loss of childcare. This combined with the essential nature of my wife's work means I am now spending the majority of my time caring for my son.

In many fields, productivity is a key factor for success and career advancement; this is especially true in the natural sciences where it is often touted as “publish or perish.” Being productive is particularity relevant for graduate students as early problems or missed opportunities can cascade and affect entire careers. In the short term, delays in thesis completion result in increased tuition payments and delayed entry into the workforce, that is lost earning potential. Lack of productivity also negatively affects the competitiveness for scholarships and postdoctoral positions. Moreover, the associated economic shrinkage as a result of COVID‐19 means there will be fewer non‐academic jobs available for freshly minted graduates. I'd also like to address the most commonly used phrase in this new COVID‐19 era: “now you have lots of time to write your thesis.” Let's be honest, unless my thesis is going to be about the sounds farmyard animals make—co‐authored by my son of course—it is not getting written. It feels as though I have to choose between my child and a scientific career, and as much as I love science, I am always going to pick my family.

In contrast to graduate students, principal investigators “have made it,” and our jobs are reasonably secure. But as researchers and parents, we had to construct a careful and delicate system of outsourcing childcare and domestic work to allow us to work more than full‐time. This is now all gone with the ongoing pandemic, and there is no sign yet if/when things will go back to normal. Here, we want to give a voice to all researchers that are now faced with the double duty of actively caring for their children in addition to working full‐time—an impossible combination. Faced with these full‐time tasks that we usually “enjoy” only for a couple hours each day, time has become an even more precious resource for parenting researchers than ever before.

And thus, we must ask ourselves: What is most important? The answer is clear and easy, even if it comes with challenges: Without any doubt, the well‐being of our children and family is most important. But it is not only for selfish reasons that our children must be the highest priority. They will be a generation who has experienced and been shaped by the pandemic—the greatest global crisis since the Second World War. It is essential that they are not traumatized by this experience, that they become strong and smart individuals who can build a resilient and intelligent society that is better prepared to handle future threats and pandemics. All parents have an “essential and system‐relevant” job.

While the choice is clear, the pandemic still places parenting researchers in a difficult situation. We are being told that we should have more time to write funding applications, finish our manuscripts, and supervise our students. At the same time, all colleagues at the forefront of post‐secondary teaching are expected to seamlessly move their courses online, which is a tremendous challenge. Clearly, there is a stark disconnect between the daily experience of parenting researchers and the expectations from the scientific community, funding agencies, university administration, and the general public. Moreover, the current structure of the academic system—funding, publishing incentives, and career options—disadvantages parents and women in particular. The present pandemic deepens the already existing divide between parenting researchers and their peers without such obligations. In the long run, this will negatively affect recruiting and retaining junior scientists and maintaining a diverse talent pool. Addressing these issues is of particular urgency given the uncertainty of how the “new normal” will look like once we all go back to work—those of us who still have work, that is.

How can we develop a scientific culture that offers everyone the same chances and supports the best minds regardless of whether they are active parents or not? Now is the time to completely re‐think the academic system to truly facilitate equity, diversity, and inclusion. Therein, different factors need to be considered in order to retain and support current researchers and attract future scientists. In particular, many questions regarding the funding of research and the career perspectives of scientists with non‐linear life paths need to be addressed by the whole community. How can career delays and lower productivity of parenting graduate students be limited and fairly recognized? How can we ensure their job perspectives in both academic and non‐academic settings? How will future competition for research funding address these issues? These problems have been known for many decades and will further be exacerbated by the expected economic challenges in the wake of the pandemic: Both job prospects and research funding will likely be even more competitive. Without conscious and radical efforts to build a strong and diverse scientific ecosystem, there will be additional damage to the competitiveness of our societies if we compromise on the quality of innovation, knowledge, and intellectual resources. It is therefore critical that we analyze the effects of the pandemic on parenting researchers and trainees, and seize the opportunity to thoroughly revamp the academic system and not simply go back to the old routine once it is over.

EMBO Reports (2020) 21: e50738

Contributor Information

Ute Kothe, Email: ute.kothe@uleth.ca.

Hans‐Joachim Wieden, Email: hj.wieden@uleth.ca.