Abstract

Background

Persistent oxidative stress can lead to chronic inflammation and mediate most chronic diseases including neurological disorders. Oleuropein has been shown to be a potent antioxidant molecule in olive oil leaf having antioxidative properties.

Objective

The aim of this study was to investigate the protective effects of oleuropein against oxidative stress in human glioblastoma cells.

Methods

Human glioblastoma cells (U87) were pretreated with oleuropein (OP) essential oil 10 µM. After 30 minutes, 100 µM H2O2 was added to the cells for three hours. Cell survival was quantified by colorimetric MTT assay. Glutathione level, total oxidant capacity, total antioxidant capacity and nitric oxide levels were determined by using specific spectrophotometric methods. The relative gene expression level of iNOS was performed by qRT-PCR method.

Results

According to viability results, the effective concentration of H2O2 (100µM) significantly decreased cell viability and oleuropein pretreatment significantly prevented the cell losses. Oleuropein regenerated total antioxidant capacity and glutathione levels decreased by H2O2 exposure. In addition, nitric oxide and total oxidant capacity levels were also decreased after administration of oleuropein in treated cells.

Conclusion

Oleuropein was found to have potent antioxidative properties in human glioblastoma cells. However, further studies and validations are needed in order to understand the exact neuroprotective mechanism of oleuropein.

Keywords: Anti-inflammatory, anti-oxidant, glioblastoma, in vitro, neuroprotection, oleuropein

1. INTRODUCTION

Ageing is one of the most important factors in the pathologies of diseases such as Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s that occur in advanced ages. Recent studies have supported that high intake of food rich in monounsaturated fatty acids has a protective effect against Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s diseases [1]. This effect of monounsaturated fatty acids could be related to their role of maintaining the structural integrity of neuronal membranes [1, 2]. Oleuropein is the main phenolic compound in olive leaf and responsible for the characteristic bitterness of immature and unprocessed olives. It is heterosidic ester of elenolic acid and hydroxytyrosol and possesses beneficial effects on human health [3]. Oleuropein is known to have many biological activities like antimicrobial, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-carcinogenic and antiviral activity [4-10].

Many neurodegenerative diseases result in damage to neurons and disruptions in their structural functions. Oxidative stress is one of the most important key factors in aging and leads to the development and progression of neurodegenerative diseases [11]. Hydrogen peroxide is produced in neurons and it is one of the major contributors to oxidative damage. Olive, in its leaf and oil, contains some biologically active polyphenols like oleuropein, hydroxytyrosol, tyrosol and caffeic acid. These compounds have important antioxidant effects and protect brain cells against oxidative damage. Oleuropein may prevent oxidative stress by leading an enhancement of the antioxidant response and scavenging free radical species [12]. Therefore, in this study, it was aimed to investigate the effects of oleuropein on H2O2 induced neuronal toxicity in human glioblastoma cells.

2. MATERIALs and METHODS

2.1. Cell Culture and Treatments

Human glioblastoma (U87) cells were obtained from American Tissue Culture Collection (Manassas, VA) and maintained in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 2mM glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin, at 37°C with 5% CO2 conditions. Then the cells were plated in 24-well plates (0.4×105cells/ml). In order to measure the effective concentration of exogenously applied H2O2 (5-250 μM), the maintenance medium was removed, medium containing H2O2 was added, and the cells were incubated for 24h. Similarly, the effective concentration of oleuropein (Sigma, EU) was identified. For this purpose, Oleuropein stock solution (1mM) was prepared by dissolving it in cell culture media. It was applied to the cells at different concentrations (5-100 μM) taking into account the required dilution factors. The cells were pretreated with oleuropein for 30 minutes before H2O2 application and then incubated for 24h.

2.2. Viability Assay

Cell viability was determined by MTT (4-5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2-5-diphenyltetrazolium bro- mide) assay [13]. Briefly, the viable cells produced a dark blue formazan product, whereas no such staining was formed in the dead cells. The cell viability was calculated by the normalization of optical densities (OD 570 nm) to the untreated control cells.

2.3. Homogenate Preparation

Cells were homogenized in ice-cold homogenization buffer (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA, 25 mM MgCl2, 0.1 mM dithiothreitol, 0.25 M sucrose, pH 7.4) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (aprotinin, phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, leupeptin, sodium fluoride) (Sigma, Germany). Homogenates were centrifuged at 4ºC, 15000×g for ten minutes and the soluble fraction was retained. The protein concentrations of cell extracts were measured by the Bradford reagent using bovine serum albumin as a standard.

2.4. Spectrophotometric Analyses

Nitric oxide concentration in cultured cell medium was determined indirectly by measuring the nitrite levels based on Griess reaction [14]. Samples were deproteinized with 75 mM zinc sulphate. Total nitrite was determined by spectrophotometrically at 546 nm after conversion of nitrate to nitrite by copperized cadmium granules. Non-enzymatic antioxidant (GSH) content of U87 cell homogenates was determined according to the method of Sedlak and Lindsay [15].

2.5. Total Antioxidant Capacity (TAC) Analy- ses

TAC levels in homogenates were analyzed by using commercial kits (Rel Assay Diagnostics, Turkey). Absorbance measurements were performed on the spectrophotometer at the wavelength of 660 nm. TAC values of the samples were recorded as µmol Trolox Eqiv./L.

2.6. Total Oxidant Capacity (TOC) Analyses

TOC levels in homogenates were analyzed using commercial kits (Rel Assay Diagnostics, Turkey) by following the procedures given. The absorbance values of the standard and the samples were read at the wavelength of 530 nm in the spectrophotometer. The TOC values of the samples were recorded in µmol H2O2 Eqiv/L.

2.7. RNA Isolation and qRT-PCR Analyses

Real-time PCR was performed in a qPCR system (Bio-RAD CFX96, Touch-South Korea). Total RNA from U87 cells were extracted using TRI- reagent (Sigma, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. One µg of total RNA was reverse-transcribed with reverse transcriptase kit (Thermo, Germany) in 20µl reaction volume. One µl of each cDNA was used as a template for amplification by using SYBER Green PCR amplification reagent and gene-specific primers. The human primer sets used were obtained from Thermo Electron Corporation (Germany): iNOS forward: 5’-GGC CTC GCT CTG GAA AGA A-3’, reverse: 5’-TCC ATG CAG ACA ACC TT-3’. The amount of RNA was normalized to β-actin amplification in a separate reaction. β-actin forward: 5’-CAT CGT CAC CAA CTG GGA CGA C-3’, reverse: 5’-CGT GGC CAT CTC TTG CTC GAA G-3’. The cycling method was performed shortly as an initial 5m denaturing step at 95°C, followed by 40 cycles of 95°C for 10s, 60°C for 30s, and 72°C for 15s. Relative quantification of iNOS expression levels was elevated by the 2-DDCt method.

2.8. Statistical Analyses

The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and post hoc Duncan tests was performed on the data to examine the differences among the groups using the SPSS statistical software package. The results are presented as Mean ± SEM. A value of p<0.05 was considered significant.

3. RESULTS

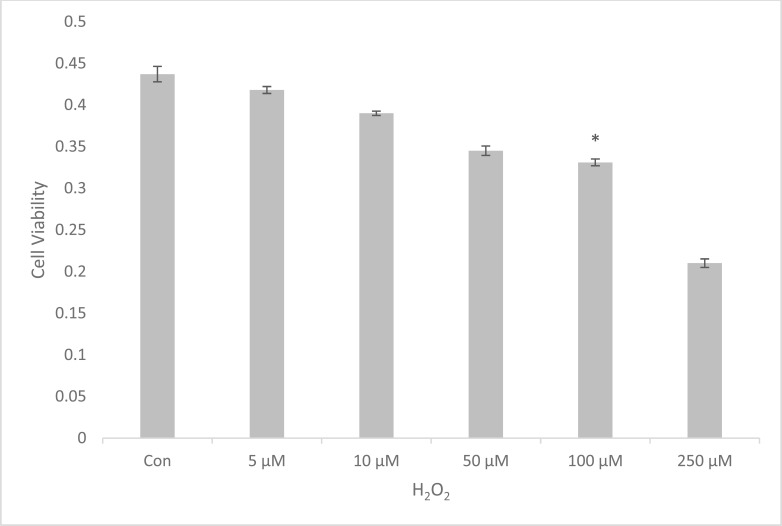

The viability of U87 cells was decreased steadily in a concentration-dependent manner over the range of 5 to 250µM following H2O2 treatment. The data showed that 100µM H2O2 killed about 24% (0.331 ± 0.009) of the cells at the end of the incubation when compared to the control (0.437 ± 0.021) (*p<0.05) (Fig. 1).

Fig. (1).

Dose dependent effect of H2O2 on U87 cell viability. The data is represented as Mean ± SEM of five independent experiments (*p<0.05 compared to control group).

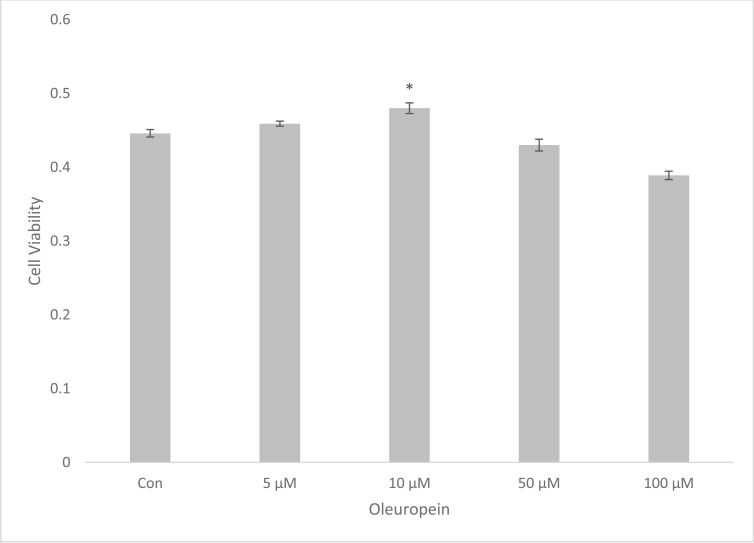

Our viability results indicated that 10µM OP (0.480 ± 0.016) increased the number of viable cells by 7.6% when compared to the control (0.446 ± 0.011). This concentration was used as a cell protective concentration for further experiments. Treatments utilizing 50µM and higher concentrations of OP decreased cell viability (Fig. 2) (*p<0.05). Dose-response studies demonstrated that 10µM OP pretreatment (0.428 ± 0.014) decreased cell losses by 18% caused by H2O2 (0.347 ± 0.006) (**p<0.05) (Fig. 3).

Fig. (2).

Dose dependent effect of OP in viability. The data is represented as Mean ± SEM of five independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared to control group.

Fig. (3).

Dose dependent protective effect of OP on H2O2-induced cytotoxicity in cells. The data is represented as Mean ± SEM of five independent experiments. *P<0.05 compared to control group. **P<0,05 versus H2O2 group.

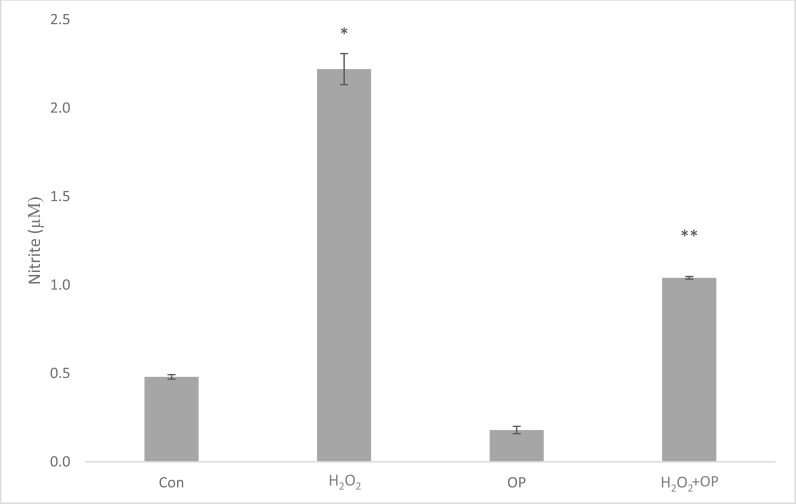

In the present study, H2O2 exposure of the cells in culture medium elevated nitrite levels by 4.4 fold (2.2 ± 0.196) in comparison to control group (0.5 ± 0.029)(*P<0.05). A significant decrease (54%) in nitrite production was observed in cells pretreated with 10µM OP (1.01 ± 0.016) (**p<0.05) according to H2O2 treatment (Fig. 4). In addition, H2O2 exposure significantly induced iNOS (4.2 fold) mRNA expressions in comparison with control cells (Fig. 5). As shown in the same figure, OP pretreatment decreased iNOS mRNAs by 21%, when compared to the H2O2 group.

Fig. (4).

Effects of OP, H2O2 and H2O2+OP treatments on nitrite levels in neuronal cells The data is represented as Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to control group; **P < 0.05 compared to H2O2-treated group (n = 5).

Fig. (5).

Analysis of iNOS expression in U87 cells. The results were normalized with housekeeping gene β actin. The data is represented as Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to control group; **P < 0.05 compared to H2O2-treated group (n = 6).

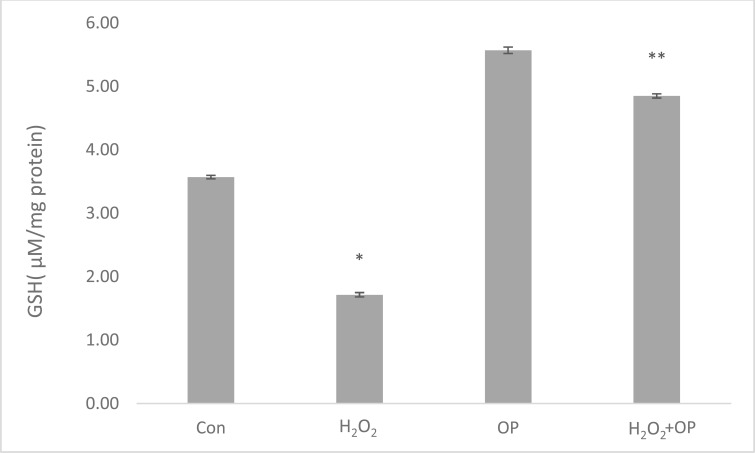

In order to determine the effect of H2O2 exposure on oxidant and antioxidant homeostasis, we measured reduced glutathione (GSH) levels in U87 cells. There was a significant decrease (52%) in GSH levels in H2O2 treated cells (1.71 ± 0.24) when compared to the control (3.57 ± 0.61) (*p≤0.05). A significant increase (2.83 fold) in GSH production was observed in cells pretreated with 10 µM OP (4.86 ± 0.34) according to H2O2 treated group (**P≤0.05) (Fig. 6).

Fig. (6).

Measured GSH levels of U87 cells with H2O2, OP and H2O2+OP. The data is represented as Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to control group; **P < 0.05 compared to H2O2-treated group (n = 6).

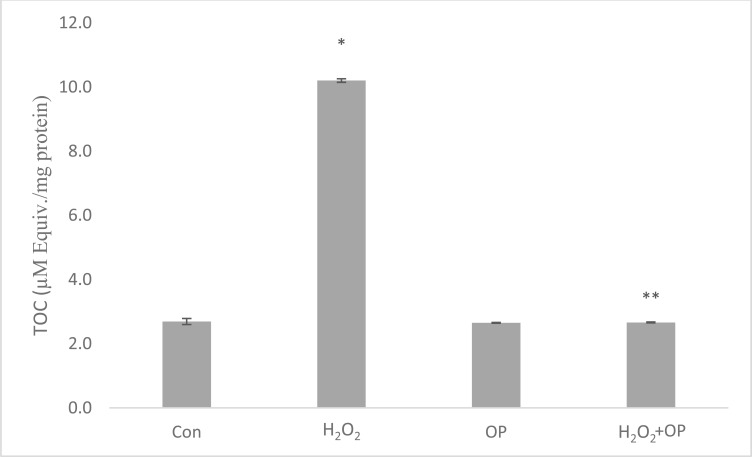

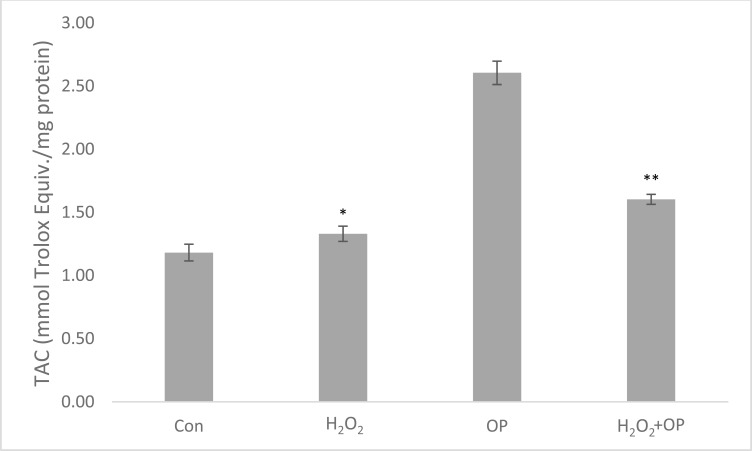

After incubation periods, H2O2 increased the total oxidant capacity about 4 times (10.2 ± 0.21) with respect to control group and it was found that this increase was suppressed by oleuropein in OP pretreated group (2.7 ± 0.25) by 3.7 fold (Fig. 7). On the other hand, H2O2 increased total antioxidant capacity by 12% (1.33 ± 0.14) and in the oleuropein pretreated group, this increase was observed as 35% (1.6 ± 0.08) according to control group (Fig. 8).

Fig. (7).

Total oxidant status of the cells in the groups after the incubation periods. The data is represented as Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to control group; **P < 0.05 compared to H2O2-treated group (n = 6).

Fig. (8).

Total antioxidant status in the groups after incubation periods. The data is represented as Mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05 compared to control group; **P < 0.05 compared to H2O2-treated group (n = 6).

4. DISCUSSION

Oxidative stress is one of the most important intracellular stimuli caused by reactive oxygen species such as H2O2 and superoxide anion [16]. The process of neuron injury is complicated and associated with oxygen free radical injury, inflammatory factor damage [17]. Many researches have demonstrated that H2O2 is used extensively in cell culture studies to explore the molecular mechanism of oxidative stress to glial cells, because the production of H2O2 is one of the main causes of oxidative damage [18, 19]. Sun et al., [20] documented that the application of H2O2 (100µM) caused significant cell loss in in vitro neuroblastoma culture. This data is in agreement with those of Malhotra et al., [21] who reported that 1h incubation of H2O2 caused significant cell losses on viability. In previous researches [22-24], it has been reported that H2O2 caused cell losses by increasing ROS production, pro-apoptotic Bax protein levels and DNA fragmentation. Here, we used an oxidative stress model of neuronal injury in U87 cells by addition of exogenous H2O2. H2O2 (100 µM) decreased cell proliferation in a dose-dependent manner and caused significant cell loss in neuronal cells.

Olive oil phenols are known to have strong antioxidant activity [25]. Recent literature indicates that oleuropein has also neuroprotective activity against Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s diseases [1]. It was reported that OP significantly inhibited cell losses on PC-12 neuron cells [22] and also prevented H2O2-induced β cell losses [26]. In our study, we observed increased cell proliferation at increasing concentrations of oleuropein and 10 μM oleuropein was found to be the most effective concentration. In addition, it was observed that oleuropein pretreatment showed good protection against neuronal cell losses induced by H2O2.

Oxidative stress in the brain of elderly people is mainly caused by the excessive production of ROS and impaired function of the antioxidant system [27]. Glutathione, a tripeptide present in almost all cells, has important roles like taking part in oxidation-reduction reactions, acting as cofactors in enzymatic reactions, scavenging free radical species and toxic xenobiotics. Porres-Martínez et al., [28] reported that administration of 100 μM H2O2 for 30 m significantly reduced intracellular GSH levels in cells in the hydrogen peroxide-induced neuronal oxidative damage model. Moreover, GSH levels were shown to be reduced significantly with 100 μM H2O2 treatment in H2O2-induced neuronal oxidative damage [29]. In a recent study, the amount of GSH increased significantly in a dose-dependent manner by the application of oleuropein to the rats in Alzheimer model of hippocampal area neurons. In addition, oleuropein significantly increased antioxidant capacity and GSH in the carbon tetrachloride-stimulated hepatotoxicity [30]. Similarly, our results indicated that 100 μM H2O2 reduced intracellular GSH contents of the cells by half. On the other hand, oleuropein pretreatment prevented the reduction in GSH levels. Oleuropein treatment alone increased the intracellular GSH levels and oleuropein administration before H2O2 regenerated the levels of GSH reduced by hydrogen peroxide. Moreover, oleuropein administration decreased the total oxidant capacity that increased by H2O2 and enhanced total antioxidant capacity in a similar manner. Moreover, similar to the data we obtained in our study, it was reported that GSH injection decreased NO levels at 3 and 6 hours in an in vivo study [31]. Based on this information, it can be said that one of the causes of cell damage of hydrogen peroxide is its reducing effect in the amount of GSH levels in the cells. Also, it can be proposed that one of the most important reasons for the antioxidant properties of oleuropein is that it regulates the intracellular GSH molecule responsible for the scavenging of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species.

NO is an important molecule in the development, maintenance and regulation of brain circuits. However, under oxidative stress, nitric oxide (NO) and its metabolites give rise to the formation of neurodegeneration by oxidizing biomolecular targets such as proteins, lipids and nucleic acids [32, 33]. Hu et al., [34] reported that H2O2 application increased both iNOS and nitrite levels in neuronal damage. In addition, it was shown that iNOS expression was significantly increased in hydrogen peroxide toxicity model of spiral ganglion cells [35]. Our study indicated that H2O2 significantly increased NO levels and upregulated iNOS gene expression in the cells. However, oleuropein pretreatment attenuated the increase in a considerable amount in NO and iNOS gene expression levels. Oxidative stress-induced cell damage is particularly associated with prostaglandins, interleukins and nitric oxide-induced inflammation. Cabrerizo et al., [36] used hydroxytyrosol, a metabolite of oleuropein, in their in vitro and in vivo neurodegeneration studies. They reported that hydroxytyrosol has an anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory effect by suppressing the increase of hypoxia-induced nitric oxide levels via increasing intracellular glutathione capacity. Besides, hydroxytyrosol was found to reduce both the activity and expression levels of inducible enzymes of COX-2 and iNOS [37]. Cell death due to neuroinflammation is mostly due to the long-term effects of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) that play an important role in the emergence of apoptotic cell death due to irreversible oxidative or nitrosative damage of neuronal cells. Therefore, oleuropein in our study can be said to have the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential to neurodegeneration by increasing glutathione level, ameliorating increased NO amounts and downregulating iNOS expression.

CONCLUSION

Many researches focus on the neuroprotective role of oleuropein which constitutes a possible pharmacological agent against oxidative stress-related neurodegeneration. Taken together, above results indicated that oleuropein, as the most active polyhydroxyl component of olive leaf and olive oil, can be said to be an effective natural compound for decreasing oxidative and nitrosative stress in hydrogen peroxide-induced neuronal toxicity. However, recent researches on the neuroprotective role of oleuropein are still very few and further analysis is a need in this area.

Acknowledgements

Declared none.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Human and Animal Rights

No Animals/Humans were used for studies that are the basis of this research.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Funding

None.

conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest, financial or otherwise.

REFERENCES

- 1.Panza F., Solfrizzi V., Colacicco A.M., D’Introno A., Capurso C., Torres F., Del Parigi A., Capurso S., Capurso A. Mediterranean diet and cognitive decline. Public Health Nutr. 2004;7(7):959–963. doi: 10.1079/PHN2004561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solfrizzi V., Panza F., Torres F., Mastroianni F., Del Parigi A., Venezia A., Capurso A. High monounsaturated fatty acids intake protects against age-related cognitive decline. Neurology. 1999;52(8):1563–1569. doi: 10.1212/WNL.52.8.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gikas E., Bazoti F.N., Tsarbopoulos A. Conformation of oleuropein, the major bioactive compound of Oleaeuropea. J. Mol. Struct. THEOCHEM. 2007;821:125–132. doi: 10.1016/j.theochem.2007.06.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bisignano G., Tomaino A., Lo Cascio R., Crisafi G., Uccella N., Saija A. On the in-vitro antimicrobial activity of oleuropein and hydroxytyrosol. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 1999;51(8):971–974. doi: 10.1211/0022357991773258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanchez J.C., Alsina M.A., Herrlein M.K., Mestres C. Interaction between the antibacterial compound, oleuropein, and model membranes. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2007;285:1351–1360. doi: 10.1007/s00396-007-1693-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andreadou I., Sigala F., Iliodromitis E.K., Papaefthimiou M., Sigalas C., Aligiannis N., Savvari P., Gorgoulis V., Papalabros E., Kremastinos D.T. Acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity is successfully treated with the phytochemical oleuropein through suppression of oxidative and nitrosative stress. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 2007;42(3):549–558. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Owen R.W., Giacosa A., Hull W.E., Haubner R., Würtele G., Spiegelhalder B., Bartsch H. Olive-oil consumption and health: the possible role of antioxidants. Lancet Oncol. 2000;1:107–112. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00015-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Visioli F., Bellosta S., Galli C. Oleuropein, the bitter principle of olives, enhances nitric oxide production by mouse macrophages. Life Sci. 1998;62(6):541–546. doi: 10.1016/S0024-3205(97)01150-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamdi H.K., Castellon R. Oleuropein, a non-toxic olive iridoid, is an anti-tumor agent and cytoskeleton disruptor. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005;334(3):769–778. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.06.161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Micol V., Caturla N., Pérez-Fons L., Más V., Pérez L., Estepa A. The olive leaf extract exhibits antiviral activity against viral haemorrhagic septicaemia rhabdovirus (VHSV). Antiviral Res. 2005;66(2-3):129–136. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin M.T., Beal M.F. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443(7113):787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Visioli F., Galli C. Biological properties of olive oil phytochemicals. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2002;42(3):209–221. doi: 10.1080/10408690290825529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hansen M.B., Nielsen S.E., Berg K. Re-examination and further development of a precise and rapid dye method for measuring cell growth/cell kill. J. Immunol. Methods. 1989;119(2):203–210. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(89)90397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cortas N.K., Wakid N.W. Determination of inorganic nitrate in serum and urine by a kinetic cadmium-reduction method. Clin. Chem. 1990;36(8 Pt 1):1440–1443. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/36.8.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sedlak J., Lindsay R.H. Estimation of total, protein-bound, and nonprotein sulfhydryl groups in tissue with Ellman’s reagent. Anal. Biochem. 1968;25(1):192–205. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(68)90092-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crow M.T., Mani K., Nam Y.J., Kitsis R.N. The mitochondrial death pathway and cardiac myocyte apoptosis. Circ. Res. 2004;95(10):957–970. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000148632.35500.d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakase T., Yamazaki T., Ogura N., Suzuki A., Nagata K. The impact of inflammation on the pathogenesis and prognosis of ischemic stroke. J. Neurol. Sci. 2008;271(1-2):104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Floyd R.A., Hensley K. Oxidative stress in brain aging. Implications for therapeutics of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol. Aging. 2002;23(5):795–807. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(02)00019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yanishlieva N.V., Marinova E., Pokorný J. Natural antioxidants from herbs and spices. Eur. J. Lipid Sci. Technol. 2006;108:776–793. doi: 10.1002/ejlt.200600127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun Z.G., Chen L.P., Wang F.W., Xu C.Y., Geng M. Protective effects of ginsenoside Rg1 against hydrogen peroxide-induced injury in human neuroblastoma cells. Neural Regen. Res. 2016;11(7):1159–1164. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.187057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Malhotra S., Tavakkoli M., Edraki N., Miri R., Sharma S.K., Prasad A.K., Saso L., Len C., Parmar V.S., Firuzi O. Neuroprotective and antioxidant activities of 4-methylcoumarins: development of structure-Activity relationships. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2016;39(9):1544–1548. doi: 10.1248/bpb.b16-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Achour I., Arel-Dubeau A.M., Renaud J., Legrand M., Attard E., Germain M., Martinoli M.G. Oleuropein prevents neuronal death, mitigates mitochondrial superoxide production and modulates autophagy in a dopaminergic cellular model. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016;17(8):E1293. doi: 10.3390/ijms17081293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling Y.Z., Li X.H., Yu L., Zhang Y., Liang Q.S., Yang X.D., Wang H.T. Protective effects of parecoxib on rat primary astrocytes from oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2016;17(9):692–702. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nousis L., Doulias P.T., Aligiannis N., Bazios D., Agalias A., Galaris D., Mitakou S. DNA protecting and genotoxic effects of olive oil related components in cells exposed to hydrogen peroxide. Free Radic. Res. 2005;39(7):787–795. doi: 10.1080/10715760500045806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vissers M.N., Zock P.L., Roodenburg A.J., Leenen R., Katan M.B. Olive oil phenols are absorbed in humans. J. Nutr. 2002;132(3):409–417. doi: 10.1093/jn/132.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cumaoğlu A., Rackova L., Stefek M., Kartal M., Maechler P., Karasu C. Effects of olive leaf polyphenols against H2O2 toxicity in insulin secreting β-cells. Acta Biochim. Pol. 2011;58(1):45–50. doi: 10.18388/abp.2011_2284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreyev A.Y., Kushnareva Y.E., Starkov A.A. Mitochondrial metabolism of reactive oxygen species. Biochemistry (Mosc.) 2005;70(2):200–214. doi: 10.1007/s10541-005-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porres-Martínez M., González-Burgos E., Carretero M.E., Gómez-Serranillos M.P. Protective properties of Salvia lavandulifolia Vahl. essential oil against oxidative stress-induced neuronal injury. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;80:154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwon S.H., Hong S.I., Ma S.X., Lee S.Y., Jang C.G. 3′,4′,7-Trihydroxyflavone prevents apoptotic cell death in neuronal cells from hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2015;80:41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domitrović R., Jakovac H., Marchesi V.V., Šain I., Romić Ž., Rahelić D. Preventive and therapeutic effects of oleuropein against carbon tetrachloride-induced liver damage in mice. Pharmacol. Res. 2012;65(4):451–464. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atakisi O., Erdogan H.M., Atakisi E., Citil M., Kanici A., Merhan O., Uzun M. Effects of reduced glutathione on nitric oxide level, total antioxidant and oxidant capacity and adenosine deaminase activity. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2010;14(1):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Butterfield D.A., Castegna A., Lauderback C.M., Drake J. Evidence that amyloid beta-peptide-induced lipid peroxidation and its sequelae in Alzheimer’s disease brain contribute to neuronal death. Neurobiol. Aging. 2002;23(5):655–664. doi: 10.1016/S0197-4580(01)00340-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beckman J.S., Koppenol W.H. Nitric oxide, superoxide, and peroxynitrite: the good, the bad, and ugly. Am. J. Physiol. 1996;271(5 Pt 1):C1424–C1437. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1996.271.5.C1424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hu J., Luo C.X., Chu W.H., Shan Y.A., Qian Z.M., Zhu G., Yu Y.B., Feng H. 20-Hydroxyecdysone protects against oxidative stress-induced neuronal injury by scavenging free radicals and modulating NF-κB and JNK pathways. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e50764. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cai J., Li J., Liu W., Han Y., Wang H. α2-adrenergic receptors in spiral ganglion neurons may mediate protective effects of brimonidine and yohimbine against glutamate and hydrogen peroxide toxicity. Neuroscience. 2013;228:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2012.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cabrerizo S., De La Cruz J.P., López-Villodres J.A., Muñoz-Marín J., Guerrero A., Reyes J.J., Labajos M.T., González-Correa J.A. Role of the inhibition of oxidative stress and inflammatory mediators in the neuroprotective effects of hydroxytyrosol in rat brain slices subjected to hypoxia reoxygenation. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2013;24(12):2152–2157. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Richard N., Arnold S., Hoeller U., Kilpert C., Wertz K., Schwager J. Hydroxytyrosol is the major anti-inflammatory compound in aqueous olive extracts and impairs cytokine and chemokine production in macrophages. Planta Med. 2011;77(17):1890–1897. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1280022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]