Abstract

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a bacterium that infects more than a half of world’s population. Although it is mainly related to the development of gastroduodenal diseases, several studies have shown that such infection may also influence the development and severity of various extragastric diseases. According to the current evidence, whereas this bacterium is a risk factor for some of these manifestations, it might play a protective role in other pathological conditions. In that context, when considered the gastrointestinal tract, H. pylori positivity have been related to Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease, Hepatic Carcinoma, Cholelithiasis, and Cholecystitis. Moreover, lower serum levels of iron and vitamin B12 have been found in patients with H. pylori infection, leading to the emergence of anemias in a portion of them. With regards to neurological manifestations, a growing number of studies have associated that bacterium with multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Interestingly, the risk of developing cardiovascular disorders, such as atherosclerosis, is also influenced by the infection. Besides that, the H. pylori-associated inflammation may also lead to increased insulin resistance, leading to a higher risk of diabetes mellitus among infected individuals. Finally, the occurrence of dermatological and ophthalmic disorders have also been related to that microorganism. In this sense, this minireview aims to gather the main studies associating H. pylori infection with extragastric conditions, and also to explore the main mechanisms that may explain the role of H. pylori in those diseases.

Keywords: Helicobacter pylori, Extragastric, Neurological, Cardiovascular, Autoimmune, Ophthalmic, Diabetes, Timeline, Treatment

Core tip: Helicobacter pylori is a bacterium that is known to infect the gastric environment and to be related to gastroduodenal diseases, including peptic ulcer and gastric adenocarcinoma. However, since the 80s the relationship between this infection and manifestations that affect not only the gastric system has been studied, such as inflammatory bowel disease, iron and B12 deficiency, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, hepatic carcinoma, multiple sclerosis, Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, and Guillain-Barré syndrome. In this sense, this study made a survey of these manifestations and their physiopathology.

INTRODUCTION

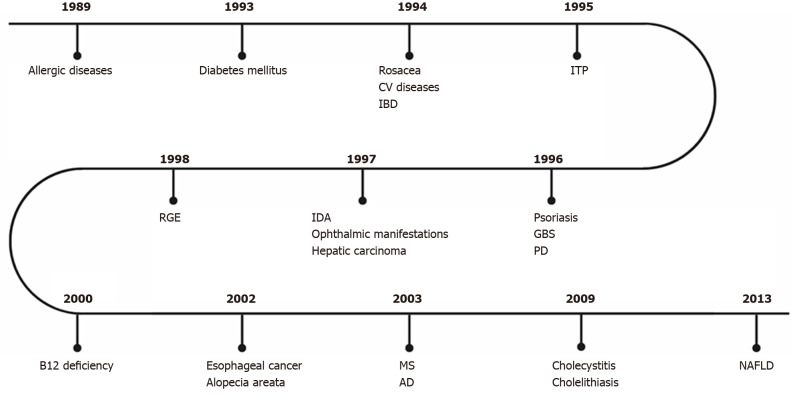

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is a gram-negative bacterium that inhabits the gastric environment of 60.3% of the world population, and its prevalence is particularly high in countries with inferior socioeconomic conditions, exceeding 80% in some regions of the globe[1]. This phenomenon occurs, among other reasons, due to the unsatisfactory basic sanitation and high people agglomerations observed in many underdeveloped nations, scenarios that favour the oral-oral and fecal-oral transmissions of H. pylori[2]. Another possible transmission route of this pathogen currently being discussed is the sexual route[3], since people with H. pylori-positive sexual partners have higher infection rates than control groups. It is well established that this microorganism is mainly related to the development of gastroduodenal disturbances, of which stand out peptic ulcer, mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma[4-6]. However, since the 1980s, growing evidence have associated such infection with several extragastric manifestations (Figure 1)[7].

Figure 1.

First studies on the association between Helicobacter pylori infection and extragastric manifestations over time. CV: Cardiovascular; IBD: Intestinal bowel disease; ITP: Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura; GBS: Guillain-Barré Syndrome; IDA: Iron deficiency anemia; RGE: Gastroesophageal reflux disease; PD: Parkinson’s disease; MS: Multiple sclerosis; AD: Alzheimer’s disease; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease.

In that context, H. pylori infection seems to influence the onset and the severity of diseases from multiple organ systems, behaving as a risk factor for a number of disorders but also as a protective agent against some conditions[8]. Regarding the main diseases that affect organs other than the stomach in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT), the H. pylori infection appears to be associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), hepatic carcinoma, cholelithiasis, and cholecystitis[7]. Besides that, serum vitamin B12 and iron deficiencies are known to be worsen or even caused by H. pylori infection. In addition, ocular, dermatological, metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurological diseases are also related to that microorganism[8,9].

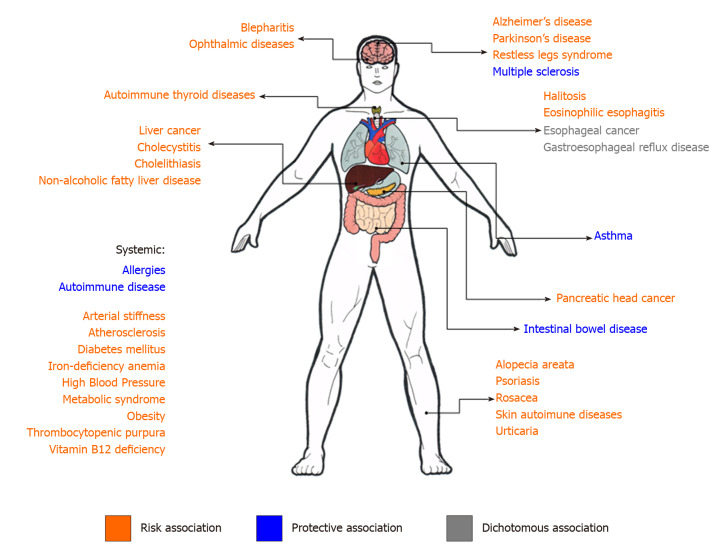

Given the background, this minireview aimed to compile evidence supporting the main associations between H. pylori infection and extragastric diseases (Figure 2), as well as to gather information on the supposed mechanisms that may link that bacterium to manifestations occurring in organs far from their primary infection site (Table 1)[10]. The publications with the highest level of evidence found for each non-gastroduodenal manifestation were selected and listed at Table 2.

Figure 2.

Summary scheme of non-gastric manifestations of Helicobacter pylori infection. In orange, the manifestations for which Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection represents a risk association. In green, the manifestations for which H. pylori infection represents a protective association. In gray, the manifestations for which studies show a dichotomous association.

Table 1.

Non-gastric manifestations of Helicobacter pylori and their suggested mechanisms of pathophysiology

| Non-gastric manifestation | Mechanisms of pathology suggested to be correlated | |

| Allergic diseases | Hygiene hypothesis[9,96] | |

| Alzheimer’s disease | Vitamin B12 deficiency leading to increased concentrations of homocysteine[109] | |

| Anormal hyperphosphorylation of the TAU protein caused by H. pylori infection[109] | ||

| ApoE polymorphism[110] | ||

| Asthma | Treg pattern, suppressing Th-2-mediated allergic response[94] | |

| Atherosclerosis and myocardial infarction | Stimulation of foam production inside macrophages, contributing to the magnification of the atherosclerotic plaque and arterial dysfunction[122] | |

| B12 deficiency | Still to be clarified, but proven to be independent of gastric atrophy and bleeding that impair their dietary absorption[49] | |

| Cholelithiasis | Presence of H. pylori infected bile[43,44] | |

| Coronary arterial disease/systemic arterial stiffness | Increased levels of homocysteine[132]. | |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | Hyperacidity[25] | |

| Diabetes mellitus | Increased cytokine production; phosphorylation of serine residues from the insulin receptor substrate[136] | |

| Hepatic carcinoma | Inflammatory, fibrotic and, consequently, necrotic process[37,38] | |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) | CagA may stimulate the synthesis of anti-CagA antibodies that cross-react with platelet surface antigens causing ITP[74,75] | |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Reduced intestinal inflammation through release of IL-18 and development of FoxP3-positive regulatory T cells[16-18] | |

| Neutrophil-activating protein reducing inflammation through Toll-like receptor 2 and IL-10 stimulation[19,20] | ||

| Iron deficiency anemia | Still to be clarified, but proven to be independent of gastric atrophy and bleeding that impair their dietary absorption[49] | |

| Relationship with growth disorders in children[52,53] | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | Hygiene hypothesis[9] | |

| Inhibitory induction of H. pylori over the Th1 and Th17 immune response[103] | ||

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | H. pylori induced insulin resistance[32] | |

| Reduced production of adiponectin[33] | ||

| Liver inflammation[34,35] | ||

| Ophthalmic manifestations | Systemic inflammatory status; increased oxidative stress; mitochondrial dysfunction; damage to DNA[82] | |

| Parkinson’s disease | Increased synthesis of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,36-tetrahydropyridine[118] | |

| Reduced levodopa absorption[118] | ||

H. pylori: Helicobacter pylori; CagA: Cytotoxin-associated gene A.

Table 2.

Levels of evidence of the risk relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and each non-gastroduodenal manifestation

| Manifestation | Year of publication1 | Ref.1 | Level of evidence |

| Alopecia areata | 2017 | Behrangi et al[72] | III |

| Alzheimer’s disease | 2016 | Shindler-Itskovitch et al[107] | II |

| 2020 | Fu et al[108] | II | |

| Arterial hypertension | 2018 | Wan et al[127] | III |

| Asthma | 2013 | Wang et al[90] | II |

| 2017 | Chen et al[91] | III | |

| Atherosclerosis | 2019 | Iwai et al[124] | III |

| B12 deficiency | 2000 | Kaptan et al[47] | I |

| 2018 | Mwafy et al[48] | III | |

| Central serous chorioretinopathy | 2006 | Cotticelli et al[88] | IV |

| Cholecystitis and cholelithiasis | 2015 | Guraya et al[43] | II |

| 2018 | Tsuchiya et al[41] | III | |

| 2018 | Cen et al[44] | III | |

| Coronary artery disease | 2016 | Sun et al[131] | II |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2019 | Chen et al[135] | III |

| Gastroesophageal reflux disease | 2016 | Wang et al[26] | II |

| Glaucoma | 2018 | Zeng et al[83] | III |

| 2002 | Kountouras et al[84] | III | |

| Guillain-Barré syndrome | 2020 | Dardiotis et al[120] | III |

| Halitosis | 2017 | HajiFattahi et al[29] | III |

| 2019 | Anbari et al[30] | III | |

| Hepatic carcinoma | 2017 | Huang et al[39] | III |

| Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura | 2018 | Kim et al[78] | II |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | 2017 | Castaño-Rodríguez et al[13] | III |

| 2019 | Lin et al[14] | III | |

| Iron deficiency anemia | 2018 | Mwafy et al[48] | III |

| Myocardial infarction | 2015 | Liu et al[125] | III |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2007 | Li et al[100] | III |

| 2016 | Jaruvongvanich et al[101] | III | |

| 2016 | Yao et al[102] | III | |

| Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease | 2019 | Liu et al[36] | II |

| Parkinson’s disease | 2020 | Wang et al[118] | III |

| Psoriasis | 2019 | Yu et al[67] | II |

| 2017 | Mesquita et al[64] | III | |

| Rosacea | 2017 | Saleh P et al[59] | III |

| 2017 | Jørgensen et al[62] | III |

Adapted from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons rating scale for risk studies, 2011[137].

Publications with the higher level of evidence found for the risk relationship between Helicobacter pylori infection and each non-gastroduodenal manifestation. Levels of evidence: I - High-quality, multi-centered or single-centered, prospective cohort or comparative study with adequate power, or a systematic review of these studies; II - Lesser-quality prospective cohort or comparative study, retrospective cohort or comparative study, untreated controls from a randomized controlled trial, or a systematic review of these studies; III - Case-control study, or systematic review of these studies; IV - Case series with pre/post test, or only post test; V - Expert opinion developed via consensus process; case report or clinical example; or evidence based on physiology, bench research or “first principles”.

EXTRAGASTRIC MANIFESTATIONS

IBD

One of the most studied conditions in gastroenterology field, IBD is a set of chronic disorders that affects the digestive tract and includes Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC)[11]. Although the mechanisms involved in IBD genesis are broadly studied, they are not well understood and may include genetic, immune, and environmental interactions[12]. Among these complex interplays, the association between microorganisms and IBD has been broadly explored, and, interestingly, researches have pointed to a protective role of H. pylori gastric infection in that condition. In this sense, a meta-analysis that included 60 studies found a negative association between that infection and IBD (OR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.36-0.50, P < 1-10). Besides that, such protection relationship was stronger in CD (OR = 0.38, 95%CI: 0.31-0.47, P < 1-10) and in IBD unclassified (OR = 0.43, 95%CI: 0.23-0.80, P = 0.008) when compared to UC (OR = 0.53, 95%CI: 0.44-0.65, P < 1-10)[13]. In addition, a cohort carried out in Taiwan observed an increased risk of IBD development after bacterial eradication (adjusted hazard risk = 2.15; 95%CI: 1.88-2.46, P < 0.001)[14]. Furthermore, H. pylori infection seems not only reduces the risk of IBD acquirement but also seems to minimize the clinical severity of the disease. A recent study that evaluated CD patients observed that H. pylori infection was negatively associated with fistulizing or stricturing phenotype (OR = 0.22, 95%CI: 0.06-0.97, P = 0.022), as well as with active colitis (OR = 0.186, 95%CI: 0.05-0.65, P = 0.010)[15].

A hypothesis that can justify these findings is the fact that such infection induces interleukin (IL)-18 release, leading to the development of FoxP3-positive regulatory T cells, as well as decreases the maturation of antigen-presenting cells, what reduces intestinal inflammation[16-18]. Another contributory mechanism may be the presence of the H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein that attenuate inflammation by means of the activation of toll-like receptor 2 and stimulation of IL-10 production[19,20]. Finally, the composition of gut microbiota, which seems to play a crucial role in IBD development[21], is significantly affected by the H. pylori eradication[22]. In this sense, it is plausible to think that the changes in the intestinal microbiome may be decisive in the IBD onset after H. pylori treatment, although studies evaluating this proposition are not yet available.

GERD

Still regarding gastrointestinal diseases, GERD is characterized by the abnormal stomach content reflux through the esophagus, leading to damages in its organ mucosa, among other outcomes[23]. Pyrosis, regurgitation, sore throat, cough, chest pain, and dysphagia are the most common symptoms in that condition[24].

The role of H. pylori infection in GERD is controversial since its associated gastritis can lead both to an increase or to a reduction of acidic secretion, depending on the affected gastric region. On one hand, the H. pylori-associated antral gastritis causes hyperacidity, aggravating GERD. On the other hand, the corpus gastritis results in hypoacidity and plays a protective role against that disease. Such a protective behavior can be explained by bacterial genetic factors that influence H. pylori cytotoxin-associated gene A (CagA) positivity, once CagA-positive strains are associated with corpus atrophic gastritis and acidic secretion inhibition, which suggests that they may provide GERD protection[25]. A meta-analysis conducted by Wang et al[26], involving twenty randomized controlled trials, evaluated the onset of GERD-associated symptoms and esophageal lesions, comparing H. pylori-positive patients who underwent bacterial eradication with others who did not went through it. Their results showed a rise in endoscopic reflux esophagitis incidence among treated patients (OR = 1.62, 95%CI: 1.20-2.19, P = 0,002). However, the occurrence of GERD symptoms was not significantly different between the groups (OR = 1.03, 95%CI: 0.87-1.21, P = 0.76), suggesting that the H. pylori eradication does not influence GERD symptoms onset. Regarding esophageal adenocarcinoma, which is usually due to GERD, a recent meta-analysis that included 35 studies showed that H. pylori infection may reduce the risk of development of that cancer (OR = 0.71, 95%CI: 0.57-0.92)[27]. Meantime, these studies did not distinguish the patients infected by CagA-positive H. pylori from those colonyzed by CagA-negative bacteria.

Halitosis

Another non-gastric manifestation suggested to be related to H. pylori infection is halitosis[28]. In 2017, HajiFattahi et al[29] tried to prove this correlation, showing that among patients with halitosis, 91% were H. pylori-positive, against only 32% in the control group (P < 0.001). However, knowing that halitosis is associated with poor oral hygiene conditions, it is possible that there is a bias related to theory of hygiene in this association and, in this sense, studies have tried to prove this relationship and its pathophysiology, aiming biases exclusion[30].

NAFLD

NAFLD refers to a range of disorders in which hepatic steatosis is observed by means of image or histology exams[31]. It is believed that the above-mentioned condition is promoted by the insulin resistance induced by molecules whose production is stimulated by H. pylori infection such as tumor necrosis factor and C-reactive protein[32]. Furthermore, a reduced production of adiponectin, a molecule that inhibits the fatty acid deposition in the liver, is observed in H. pylori patients[33]. Moreover, the bacterium can reach the liver through the biliary tree and can lead to liver inflammation[34,35]. Recently, studies have been developed in order to verify if H. pylori infection plays a role in that disease. Indeed, a meta-analysis that included 21 studies observed a positive association between this infection and NAFLD (OR = 1.529, 95%CI: 1.336-1.750, P = 0.000)[36]. It is important to be highlighted that most available studies on this issue took place in Asian countries, so this data should be interpreted with caution when considered the Western population.

Hepatic carcinoma

Although researches have investigated the association between H. pylori infection and liver carcinoma, conflicting results have been found. However, it was already shown that H. pylori infection is associated with liver inflammation, fibrosis, and necrosis. Along with these repercussions, the bacterial translocation through the biliary tract may also lead to direct hepatic damage, predisposing or even triggering the carcinogenic process[37,38]. The rates of H. pylori infection among HBV-related hepatic carcinoma patients (68.9%) and HBV-negative hepatic carcinoma (33.3%) were higher when compared to control groups (P < 0.001)[39]. In this sense, studies agree with regards to the screening of H. pylori infection followed by the bacterial eradication in patients with liver disorders, in order to prevent the progression of the preexisting disease and the cancer onset[39,40].

Cholecystitis and cholelithiasis

Recent research has investigated the possible risk relationship between H. pylori infections and the development of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis[41,42]. Regarding the first one, studies have shown that the presence of H. pylori in bile may be a risk factor for its development[43]. Moreover, among other studies, a meta-analysis demonstrated a positive association between H. pylori infection and chronic cholecystitis/ cholelithiasis (OR = 3.022; 95%CI: 1.897-4.815; I2 = 20.1%)[44-46]. Among the possible explanations for that phenomenon, it is believed that H. pylori may infects the biliary system, causing chronic inflammation in its mucosa and, as a result, leading to the impairment of acid secretion and reduction of the dissolvability of calcium salts in bile, what predisposes the formation of gallstones[44].

B12 deficiency

A probable risk relationship between H. pylori infection and pernicious anemia was also suggested[47]. Case-control and prospective cohort studies have shown that patients with positive H. pylori had lower Vitamin B12 (Cobalamin) levels when compared to control groups[47,48]. In addition, when treated with triple therapy - clarithromycin, amoxicillin and omeprazole - to eradicate H. pylori, patients with previous pernicious anemia obtained satisfactory levels of Vitamin B12, with mean iron levels of 262.5 ± 100.0 pg/mL among H. pylori-positives against 378.2 ± 160.6 pg/mL in the group of H. pylori-negatives, representing a difference of 30.6% between those groups, with a P value of 0.001[48]. Corroborating to the consolidation of this association, studies have shown that there is a decrease in Cobalamin levels in H. pylori positive patients regardless of gastric atrophy and dyspepsia[49]. Even though there is still a lack of studies with regard to clarifying the pathophysiological process of this risk association, the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report[50] recommends that in patients with this deficiency, H. pylori should be sought and eradicated.

Iron deficiency anemia

Choe et al[51] conducted a randomized case-control study to test whether anemic patients positive for H. pylori, when underwent infection eradication therapy, have a better response of blood iron levels when compared to the control group. The results were positive for the risk association between infection and anemia. Since then, studies have tried to understand the pathophysiology behind this manifestation, in addition to evaluate its occurrence in different age groups.

In this scenario, subsequent studies confirmed this correlation, in addition to explaining that it occurs regardless of bleeding. That is, there is no need for tissue damage and hemorrhagic processes for the onset of anemia due to infection by H. pylori[52]. When comparing H. pylori positive patients to the H. pylori negative ones, the first group had iron levels of 71.6 ± 24.8 μg/dL against 80.1 ± 20.7 μg/dL of the second one, a difference of 10,6%, with a t value of −3.206 and P value: 0.001[48].

It has also been suggested that the anemia triggered by H. pylori infection is a causal factor for growth disorders among children and adolescents. Although this is a difficult relationship to be proven, some studies agree on the influence of anemia triggered by H. pylori as a causal factor for developmental gap among infants[52,53]. In this sense, groups of children with unexplained anemia and growth disorders presenting clinical manifestations suggestive of infection by this bacterium should be screened and, if necessary, undergo H. pylori eradication, as recommended by current guidelines[50].

Dermatological and autoimmune diseases

Some studies suggest an association and possible causality of H. pylori infection in some dermatological diseases[8]. Among them, rosacea and some immunological diseases such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, psoriasis, alopecia areata, and urticaria are the most studied ones. However, the evidence makes it clear that significant associative power with H. pylori infection only occurs in some of these diseases, whereas in many of them conflicting results have been obtained, demanding further research with more appropriate methodologies and statistical designs[54]. As for autoimmune diseases, they are characterized by a dysregulation of the immune system, which leads to loss of tolerance to auto antigens[55]. It is believed that these diseases have a multivariate etiology and that infectious agents can trigger them. The immunological response against H. pylori can generate an inflammatory condition that potentially leads to the development of cross-reactive antibodies[56].

Rosacea is a chronic disease with skin manifestations such as facial erythema, edema, papules, telangiectasia, and pustules that are located, most of the time, in the center of the face[57]. A risk association has been observed between H. pylori infection and rosacea, and the treatment of this bacterial infection dramatically decreases the severity of such dermatological disorder[58]. Other authors observed the same associative results, and began to recommend that patients with rosacea who are positive for H. pylori should be treated with bacterial eradication[59-61]. However, a meta-analysis concluded that cause-effect associations are weak between this disease and H. pylori infection (OR = 1.68, 95%CI: 1.100-2.84, P = 0,052) and that H. pylori eradication therapy does not reach the statistical significance necessary for its mass recommendation, (RR= 1.28, 95%CI: 0.98-1.67, P = 0,069)[62]. The contrast of the results found in the literature may be related, among other things, to the big variability in methodological and statistical designs used.

Psoriasis is a chronic, non-contagious inflammatory skin disease, with genetic and autoimmune characteristics that affects the skin and joints[63,64]. Its association with H. pylori infection had already been investigated with the search for antibodies against H. pylori in patients with psoriasis without known gastrointestinal complaints[65]. Recently, a meta-analysis found a strong evidence demonstrating this association (OR = 1.19, 95%CI: 1.15-2.52, P = 0.008) and highlighted that the rate of H. pylori infection, interestingly, was significantly high in patients with moderate and severe psoriasis (OR = 2.27; 95%CI: 1.42-3.63, I2 = 27%) but not in patients with the milder disease (OR = 1.10; 95%CI: 0.79-1.54, I2 = 0%)[66]. Another disease commonly associated with H. pylori infection is chronic urticaria, a clinical condition that presents with itchy, erythematous or swollen urticaria[67,68]. The studies reveal conflicting evidence regarding the cause-effect association of H. pylori with chronic urticaria. Interestingly, a meta-analysis showed that the improvement in chronic urticaria was not directly linked to the eradication of H. pylori, but with the antibiotic therapy used, and, even if the treatment was not effective, a significant remission in chronic urticaria was observed in those patients[69,70].

Alopecia areata (AA), an autoimmune disease, leads to hair loss and can present a variable course among affected individuals[71]. There are few published studies on the association of AA with H. pylori infection. In an Iranian case control study, a statistically significant risk association was observed (OR = 2.263, 95%CI: 1.199-4.273); however, the study limitations such as the incapacity of controlling some confounding variables weaken this evidence[72].

Idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) is a condition that results from the individual's platelet destruction mediated by antiplatelet antibodies[73]. Several studies associate the relationship between H. pylori infection and ITP. Although the pathogenesis involved in this process is inconclusive, some authors suggest that CagA stimulates the synthesis of anti-CagA antibodies that cross-react with platelet surface antigens causing ITP[74,75]. The first correlation of this possible pathogenesis observed an increase in patients' platelet count after H. pylori eradication[76]. Other studies have also been conducted in order to evaluate the remission of PTI after the treatment of H. pylori infection. A prospective Brazilian study demonstrated an increase in platelets after bacterial eradication in part of the H. pylori-positive patients with ITP. In addition, a significant decrease in the levels of cytokines of the pro-inflammatory profiles Th1 and Th17 as well as an increase in anti-inflammatory cytokines linked to regulatory T cells (Treg) and Th2 were observed in infected patients with ITP in whom an increase in platelet count after H. pylori eradication was observed[77]. A recently published meta-analysis corroborates the significant therapeutic effect that H. pylori eradication has on patients with ITP and suggests that this evidence can be taken into account in the clinical treatment of patients with ITP (OR = 1.93, 95%CI: 1.01-3.71, P = 0.05)[78]. This study presents fragilities since it included researches with a limited number of individuals, few studies with adults, and embraced a small variation of ethnicities. However, it is important to highlight that H. pylori infection investigation and eradication have been recommended by ITP clinical management guidelines[79].

Ophthalmic manifestations

Ophthalmic manifestations association with H. pylori was firstly studied by Mindel and Rosenberg[80], when they tried to relate the rosacea’s ocular manifestations with this bacterium. The ocular and extraocular microbiomes and their influence in ophthalmic diseases have been extensively studied and although some associations with H. pylori infection are controversial, a set of diseases as open-angle glaucoma, central serous chorioretinopathy (CSCR), and blepharitis have been more widely studied[81,82].

Cytokines induced by the H. pylori in gastric mucosa can generate a systemic inflammatory status contributing with the pathogenesis of these diseases through increased oxidative stress, causing mitochondrial dysfunction and damage to DNA. This process culminates in morphological changes and apoptosis. Oxidative stress is an important pillar in the pathogenesis of both conditions but it is a controversial causal association without large-scale studies[82].

A meta-analysis showed a significant correlation between H. pylori infection and open-angle glaucoma (OR = 2.08, 95%CI: 1.42–3.04). Analyzing the subgroups, this association was present in primary open-angle glaucoma (OR = 3.06, 95%CI: 1.76-5.34; P < 0.001) and normal tension glaucoma (OR = 1.77, 95%CI: 1.27-2.46; P = 0.001), but not seen with pseudoexfoliation glaucoma (OR = 1.46, 95%CI: 0.40-5.30; P = 0.562)[83]. The H. pylori eradication can result in an improvement of intraocular pressure (P < 0.001) and visual field (P ≤ 0.01) parameters[84]. The eradication had been either associated with the reduction of ocular rosacea symptoms in a case series[85], improvement in patients with CSCR[86] and better cytology results in 50%of patients with H. pylori and blepharitis (n = 142)[87]. Regarding CSCR, studies have shown a higher prevalence of the disease among H. pylori positive patients (78.2%, 95%CI: 56% -92%) when compared to the control group (43.5%, 95%CI: 23%-65%), with P < 0.03 and a 4.6 OR[88].

Asthma and allergic diseases

The research on infections, microbiome and allergic diseases started with the discussion about hygiene hypothesis due to the increase of allergic diseases as allergic rhinitis or hay fever, asthma and eczema in the post industrial revolution world[9]. The first study that aimed to determine the seroprevalence of H. pylori in asthma patients was performed in 2000 and had inconclusive founds[89]. Therefore, several studies were conducted in an attempt to elucidate the association between both conditions and although some findings are controversial, meta-analyses indicate that H. pylori infection could be considered a protective factor for asthma especially in children and in patients with cagA-positive strains[90,91].

The H. pylori infection as other microbial antigens tends to induce, especially in adults, a Th1 polarized response. This pro-Th1 balance inhibits the activation of a Th2 immune response, fundamental in the asthma and allergies pathophysiology whereas eosinophilic activation and IgE production are dependent of IL-4 and IL-5[92]. The neutrophil-activating protein of H. pylori (H. pylori-NAP) can induce this polarization in vivo and in vitro and could be a target in the development of a treatment or a prevention strategy for asthma and others allergic diseases[93].

In children, the H. pylori infection produces a predominant Treg pattern[94] that either suppress the Th2-mediated allergic response. Furthermore, the H. pylori IgG titre in children was inversely correlated with asthma severity[95]. This response triggered against bacterial antigens is strong and could suppress responses to autoantigens and allergens[96]. Another mechanism that could explain the lower incidence of asthma in H. pylori carriers is that the presence of the bacteria, especially CagA+ strains, protects against gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), reducing GERD-related asthma and the exacerbations associated with this condition[97].

Considering that H. pylori infection is associated with poor household hygiene, some authors and studies endorse that the infection should be considered a biomarker for precarious condition instead of a specific protective factor for allergic diseases[98].

Multiple sclerosis

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic inflammatory disease that affects the central nervous system (CNS), causing a multifactorial immune dysregulation that involves genetic and environmental factors[99]. For the first time, in 2007, it was reported a negative association between H. pylori infection and MS[100]. In that occasion, a japanese study included patients with opticospinal MS (OSMS), conventional MS (CMS), and healthy controls (HC). The results showed a considerably lower H. pylori seropositivity in CMS patients (22.6%, P < 0.05) when compared to HC (42.4%, P = 0.0180) and OSMS individuals (51.9%, P = 0.0019). After that, various studies investigated such association and two meta-analyses were conducted in order to evaluate the possible protective effect of H. pylori infection to MS. The first one included 1902 patients and demonstrated a significantly lower infection prevalence among SM patients when compared to controls with the same age range and sex (OR = 0.59, 95% CI: 0.37–0.94, P = 0.03)[101]. The second one embraced 2806 individuals and also found a reduced general prevalence of H. pylori infection in MS patients (24.66% vs 31.84%, OR: 0.69, 95%CI: 0.57-0.83, P < 0.0001)[102].

Among the various hypothesis that try to justify the H. pylori infection as a protection factor for MS, the hygiene hypothesis argues that the exposition to microbial agents during childhood modulates the human immune system, avoiding the development of immune hypersensitivity during adulthood[9]. Another mechanism that is probably associated with this process is the inhibitory induction of H. pylori over the Th1 and Th17 immune response by means of the FoxP3-positive regulatory cells[103].

Interestingly, the immune response against the H. pylori infection also seems to be influenced by the MS. In a cohort that included 119 MS patients (most of them with acute remittent-recurrent MS), it was demonstrated that the H. pylori positive patients presented a reduced humoral response against the bacterial protein HP986[104]. However, another study investigated the antibodies production against the H. pylori VacA (vacuolating cytotoxin A) in patients with secondary progressive MS, who presented such immunoglobulins more often when compared to healthy individuals. This suggests that the recognition of H. pylori antigens by antibodies is influenced not only by the positivity status for EM, but also by the forms of presentation of this autoimmune disease[105].

Alzheimer’s disease

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disturb with progressive cognitive impairment and has the gradual involvement of the sporadic memory as its commonest clinical representation[106]. Shindler-Itskovitch et al[107], 2016, conducted a meta-analysis that embraced 13 observational studies on the association between H. pylori and dementia. The results showed that the H. pylori-positive patients had higher risk of dementia when compared to the not infected ones (OR = 1.7, 95%CI: 1.17-2.49). However, when considered only AD patients, such association was not statistically significant (OR = 1.39, 95%CI: 0.76-2.52). Despite that, a more recent meta-analysis identified a significant positive association between H. pylori infection and AD in an Asian population (OR = 1.60, 95%CI: 1.20-2.15)[108].

Some mechanisms are supposed to be involved in the increase of AD risk in individuals infected by H. pylori. The vitamin B12 deficiency due to gastric alterations induced by the infection leads to increased concentrations of homocysteine, what leads to dementia. Other hypothesized mechanism for such association is the anormal hyperphosphorylation of the TAU protein caused by H. pylori infection. That protein is involved in the AD-linked neurodegeneration[109]. Besides that, Kountouras et al[110], showed that the H. pylori infection positively influence the ApoE polymorphism known as the mais genetic risk factor for AD.

Some hypotheses affirm that H. pylori can reach the brain, leading to changes that trigger AD. One of them is based on the H. pylori ability to reach the olfactory bulb through the oral-nasal-olfactive via[111]. Such bulb is responsible for the decodification of olfactive signals in the brain and its dysfunction is related to the enfecalic neurodegeneration. Other supposition is the bacterial access through the rupted hematoencephalic barrier (HEB) inside leukocytes, causing an inflammatory process with the release of chemical mediator[112]. All of the above-mentioned H. pylori ways to reach CNS could allow H. pylori to exert its potential neurodegenerative action in that environment[113].

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is the second most prevalent progressive neurodegenerative disturb in the world, and has tremor, postural instability, and bradykinesia as preeminent outcomes[114,115]. However, among other reverberations in the human body, gastrointestinal impairments, such as constipation, are important consequences of that disease and they often represent the first PD manifestations[116]. The supposed link between Parkinson’s disease and gastrointestinal tract led researchers to further investigate that relationship, raising the hypothesis that microorganisms from the digestive system could influence PD pathophysiology[117].

In that context, a recent meta-analysis that included 23 studies investigated the impact of viral, fungal, and bacterial infections in the risk of PD and found a positive association between H. pylori infection and that disease (pooled OR, 95%CI: 1.653, 1.426-1.915, P < 0.001)[118]. Furthermore, another meta-analysis which included 7 studies found that the H. pylori infection is also associated with the clinical severity of the PD, since H. pylori-positive patients presented poorer scores when undergone Unified Parkinson Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS) evaluation [mean ± SD, 95%CI: 6.83, 2.29-11.38, P = 0.003][119]. In addition, the last study also observed an improvement in the UPDRS-III scale in PD patients after H. pylori eradication (mean ± SD, 95%CI: 6.83, 2.29-11.38, P = 0.003). It is important to be highlighted that these researches present some limitations. Firstly, the included studies used different diagnostic criteria of PD, and the methods performed for the detection of H. pylori infection also varied. The use of ELISA for H. pylori infection diagnosis in some of these studies may have overestimated the number of positive individuals, since that test is often reagent even when performed months following a possible H. pylori spontaneous eradication. Last but not least, H. pylori infection is closely related to various socioeconomic factors, including hygiene. Consequently, some of the associations between H. pylori and PD could have been correlational and not causal[118,119].

It is known that the H. pylori infection increases the synthesis of 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,36-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP)[118]. Such substance can cause dopamine depletion, as well as damage to the substantia nigra, what can lead to PD. Concomitantly, H. pylori infection has been found to reduce levodopa absorption, what potentially has the exacerbation of PD symptoms as a consequence[118].

Guillain-Barré syndrome

The association between the Guillain-Barré syndrome and the H. pylori infection have been widely studied and, recently, a meta-analysis about this issue confirmed this interrelation, proceeding with the analysis of the anti-H. pylori antibody in serum and cerebrospinal liquid (CSL). When the first one was analyzed, the antibodies prevalence in the patients that presented GBS was significantly higher when compared to those without GBS (OR = 2.31, 95%CI: 1.30-4.11, P = 0.004). In the CSL analysis, there was also a strong positive association between GBS and anti-H. pylori IgG (OR = 42.45, 95%CI: 9.66-186.56, Pz < 0.00001)[120].

Cardiovascular diseases

Atherosclerosis is a ischemic disease caused by a chronic inflammatory process in the arterial wall and that can lead to other circulatory system diseases[121]. Yang et al[122] showed, in an animal model, a positive association between H. pylori infection and atherosclerosis. They also observed that CagA potentially stimulates the foam production inside macrophages, what contributes to the magnification of the atherosclerotic plaque and arterial dysfunction. In addition, the H. pylori-infected gastric epithelial cells-derived exosomes (Hp-GES-EVs) are absorbed by the plaques and CagA is released inside them. Such event exacerbates the obstructive inflammatory process and lead to in vitro and in vivo lesions[122]. A south korean study that evaluated the relationship between H. pylori and cardiovascular risk factors concluded that this bacterial infection has a atherogenic potential once it seems to influence the lipidic profile of the patient. The results pointed to higher levels of total cholesterol and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), as well as to decreased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) in H. pylori-positive individuals[123]. In that context, another recent study complemented that hypothesis, showing that the H. pylori eradication intensely contributed to the improvement of the lipidic parameters in dyslipidemic individuals by means of an increase in HDL levels and a drop in LDL/HDL ratio, which is a parameter used in the evaluation of the atherosclerosis risk[124].

Another meta-analysis explored the association between H. pylori and myocardial infarction (MI), and concluded that H. pylori implies a higher risk of MI (OR = 2.10, 95%CI: 1.75-2.53, P = 0.06)[125]. Interestingly, a study identified that people with IL-1 polymorphisms present higher inflammatory activity and higher chances of suffering from ST-segment elevation MI (OR = 2.32, 95%CI: 1.23-4.37, P = 0.009)[126].

A study conducted in a Chinese population identified a high prevalence of arterial hypertension in H. pylori seropositive patients (OR = 1.23; 95%CI: 1.04-1.46)[127]. One of the mechanisms that can explain that association is the production of inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, interleukin-6 and c-reactive protein induced by the H. pylori[128]. These cytokines lead to insulin resistance, contributing to the total peripheral vascular resistance and to the atherosclerotic process. Both phenomenons are related to the hypertension[129].

The coronary artery disease (CAD) is characterized by a heart blood flow reduction in the as a result of obstructions of the coronary arteries due to their narrowing due to an atherosclerotic and/or a thrombotic process[130]. A meta-analysis showed that the H. pylori infection is significantly related to higher odds of CAD (OR = 1.11, 95%CI: 1.01-1.22, P = 0.24)[131].

According Tamura et al[132], the probable hypothesis to explain the positive association between H. pylori and CAD may be linked to the atrophic gastritis caused by the bacterial chronic infection, leading to a decreased absorption of vitamin B12 and folic acid in the gastrointestinal tract. This absorptive deficiency causes an increase in the circulant levels of homocysteine, which potentially contribute to the CAD development. In addition, a study conducted by Kutluana and Kilciler[133], 2019, demonstrated that the reduced absorption of above-mentioned nutrients due to atrophic gastritis and gastric intestinal metaplasia during H. pylori infection also lead to an increase in the arterial stiffness.

Diabetes mellitus

A positive association between H. pylori infection and diabetes mellitus (DM) was found in a meta-analysis of 39 studies that included more than 20 thousands patients (OR = 2.00, 95%CI: 1.82-2.20, P = 0.07)[134]. Besides that, the H. pylori infection not only increase the risk of DM, but it also impairs the satisfactory control of glycemic levels in DM patients. A meta-analysis that included 35 studies observed that the glycated hemoglobin A levels were significantly higher in H. pylori-positive patients when compared to H. pylori negative individuals (weighted mean difference 0.50, 95%CI: 0.28-0.72, P < 0.001)[135]. However, the fact that these studies do not take into account other factors that influence the glycemic control, such as obesity index and smoking status, constitute an important limitation[134,135]. Among the hypothesis on how does H. pylori increases the risk of DM, it is believed that the increased cytokine production leads to the phosphorylation of serine residues from the insulin receptor substrate, whose linkage with insulin receptors turns deficient[136].

CONCLUSION

Although H. pylori infection is most commonly associated with gastric manifestations, growing evidence have drawn attention to its role in extragastric diseases. The knowledge on how does that bacterium influence non-gastroduodenal disorders can elucidate little understood points about their pathophysiology and may shed light on new therapeutic targets in the management of these conditions. The H. pylori eradication is already a well established therapeutic alternative in some of these diseases. However, further studies are needed in order to evaluate if the bacterial elimination can be a consistent therapeutic alternative in a greater number of health problems. Finally, the beneficial association of H. pylori infection with some extragastric diseases should be explored by future research in order to evaluate the use of the bacterium and its products in new prophylactic and therapeutic protocols.

Footnotes

Conflict-of-interest statement: There is no conflict of interest associated with any of the senior author or other coauthors contributed their efforts in this manuscript.

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Peer-review started: March 28, 2020

First decision: April 25, 2020

Article in press: July 14, 2020

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Brazil

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Abraham P, Buzas G, Kravtsov V, Lee CL, Romano M, Tosetti C S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: A E-Editor: Ma YJ

Contributor Information

Maria Luísa Cordeiro Santos, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil.

Breno Bittencourt de Brito, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil.

Filipe Antônio França da Silva, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil.

Mariana Miranda Sampaio, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil.

Hanna Santos Marques, Universidade Estadual da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45083-900, Bahia, Brazil.

Natália Oliveira e Silva, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil.

Dulciene Maria de Magalhães Queiroz, Laboratory of Research in Bacteriology, Faculdade de Medicina, Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Belo Horizonte 30130-100, Minas Gerais, Brazil.

Fabrício Freire de Melo, Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde, Universidade Federal da Bahia, Vitória da Conquista 45029-094, Bahia, Brazil. freiremelo@yahoo.com.br.

References

- 1.Coelho LGV, Marinho JR, Genta R, Ribeiro LT, Passos MDCF, Zaterka S, Assumpção PP, Barbosa AJA, Barbuti R, Braga LL, Breyer H, Carvalhaes A, Chinzon D, Cury M, Domingues G, Jorge JL, Maguilnik I, Marinho FP, Moraes-Filho JP, Parente JML, Paula-E-Silva CM, Pedrazzoli-Júnior J, Ramos AFP, Seidler H, Spinelli JN, Zir JV. Ivth brazilian consensus conference on Helicobacter pylori infection. Arq Gastroenterol. 2018;55:97–121. doi: 10.1590/S0004-2803.201800000-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sjomina O, Pavlova J, Niv Y, Leja M. Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2018;23 Suppl 1:e12514. doi: 10.1111/hel.12514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sgambato D, Visciola G, Ferrante E, Miranda A, Romano L, Tuccillo C, Manguso F, Romano M. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in sexual partners of H. pylori-infected subjects: Role of gastroesophageal reflux. United European Gastroenterol J. 2018;6:1470–1476. doi: 10.1177/2050640618800628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leja M, Grinberga-Derica I, Bilgilier C, Steininger C. Review: Epidemiology of Helicobacter pylori infection. Helicobacter. 2019;24 Suppl 1:e12635. doi: 10.1111/hel.12635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Urita Y, Watanabe T, Kawagoe N, Takemoto I, Tanaka H, Kijima S, Kido H, Maeda T, Sugasawa Y, Miyazaki T, Honda Y, Nakanishi K, Shimada N, Nakajima H, Sugimoto M, Urita C. Role of infected grandmothers in transmission of Helicobacter pylori to children in a Japanese rural town. J Paediatr Child Health. 2013;49:394–398. doi: 10.1111/jpc.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahmed KS, Khan AA, Ahmed I, Tiwari SK, Habeeb MA, Ali SM, Ahi JD, Abid Z, Alvi A, Hussain MA, Ahmed N, Habibullah CM. Prevalence study to elucidate the transmission pathways of Helicobacter pylori at oral and gastroduodenal sites of a South Indian population. Singapore Med J. 2006;47:291–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mladenova I, Durazzo M. Transmission of Helicobacter pylori. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2018;64:251–254. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.18.02480-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gravina AG, Zagari RM, De Musis C, Romano L, Loguercio C, Romano M. Helicobacter pylori and extragastric diseases: A review. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3204–3221. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i29.3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strachan DP. Hay fever, hygiene, and household size. BMJ. 1989;299:1259–1260. doi: 10.1136/bmj.299.6710.1259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hung IF, Wong BC. Assessing the risks and benefits of treating Helicobacter pylori infection. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2009;2:141–147. doi: 10.1177/1756283X08100279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Torres J, Ellul P, Langhorst J, Mikocka-Walus A, Barreiro-de Acosta M, Basnayake C, Ding NJS, Gilardi D, Katsanos K, Moser G, Opheim R, Palmela C, Pellino G, Van der Marel S, Vavricka SR. European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation Topical Review on Complementary Medicine and Psychotherapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13:673–685e. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjz051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borg-Bartolo SP, Boyapati RK, Satsangi J, Kalla R. Precision medicine in inflammatory bowel disease: concept, progress and challenges. F1000Res. 2020;9 doi: 10.12688/f1000research.20928.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Castaño-Rodríguez N, Kaakoush NO, Lee WS, Mitchell HM. Dual role of Helicobacter and Campylobacter species in IBD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2017;66:235–249. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-310545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin KD, Chiu GF, Waljee AK, Owyang SY, El-Zaatari M, Bishu S, Grasberger H, Zhang M, Wu DC, Kao JY. Effects of Anti-Helicobacter pylori Therapy on Incidence of Autoimmune Diseases, Including Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17:1991–1999. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2018.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fialho A, Fialho A, Nassri A, Muenyi V, Malespin M, Shen B, De Melo SW., Jr Helicobacter pylori is Associated with Less Fistulizing, Stricturing, and Active Colitis in Crohn's Disease Patients. Cureus. 2019;11:e6226. doi: 10.7759/cureus.6226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arnold IC, Hitzler I, Müller A. The immunomodulatory properties of Helicobacter pylori confer protection against allergic and chronic inflammatory disorders. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2012;2:10. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rad R, Brenner L, Bauer S, Schwendy S, Layland L, da Costa CP, Reindl W, Dossumbekova A, Friedrich M, Saur D, Wagner H, Schmid RM, Prinz C. CD25+/Foxp3+ T cells regulate gastric inflammation and Helicobacter pylori colonization in vivo. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:525–537. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arnold IC, Dehzad N, Reuter S, Martin H, Becher B, Taube C, Müller A. Helicobacter pylori infection prevents allergic asthma in mouse models through the induction of regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3088–3093. doi: 10.1172/JCI45041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Codolo G, Mazzi P, Amedei A, Del Prete G, Berton G, D'Elios MM, de Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori down-modulates Th2 inflammation in ovalbumin-induced allergic asthma. Cell Microbiol. 2008;10:2355–2363. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01217.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Windle HJ, Ang YS, Athie-Morales V, McManus R, Kelleher D. Human peripheral and gastric lymphocyte responses to Helicobacter pylori NapA and AphC differ in infected and uninfected individuals. Gut. 2005;54:25–32. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.025494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin J, Li R, Raes J, Arumugam M, Burgdorf KS, Manichanh C, Nielsen T, Pons N, Levenez F, Yamada T, Mende DR, Li J, Xu J, Li S, Li D, Cao J, Wang B, Liang H, Zheng H, Xie Y, Tap J, Lepage P, Bertalan M, Batto JM, Hansen T, Le Paslier D, Linneberg A, Nielsen HB, Pelletier E, Renault P, Sicheritz-Ponten T, Turner K, Zhu H, Yu C, Li S, Jian M, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhang X, Li S, Qin N, Yang H, Wang J, Brunak S, Doré J, Guarner F, Kristiansen K, Pedersen O, Parkhill J, Weissenbach J MetaHIT Consortium, Bork P, Ehrlich SD, Wang J. A human gut microbial gene catalogue established by metagenomic sequencing. Nature. 2010;464:59–65. doi: 10.1038/nature08821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Xu W, Lee A, He J, Huang B, Zheng W, Su T, Lai S, Long Y, Chu H, Chen Y, Wang L, Wang K, Si J, Chen S. The impact of Helicobacter pylori infection, eradication therapy and probiotic supplementation on gut microenvironment homeostasis: An open-label, randomized clinical trial. EBioMedicine. 2018;35:87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2018.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spechler SJ. Epidemiology and natural history of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Digestion. 1992;51 Suppl 1:24–29. doi: 10.1159/000200911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen J, Brady P. Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2019;42:20–28. doi: 10.1097/SGA.0000000000000359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowrey DJ, Williams GT, Clark GW. Interactions between Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Dis Esophagus. 1998;11:203–209. doi: 10.1093/dote/11.4.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang XT, Zhang M, Chen CY, Lyu B. [Helicobacter pylori eradication and gastroesophageal reflux disease: a Meta-analysis] Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi. 2016;55:710–716. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0578-1426.2016.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao H, Li L, Zhang C, Tu J, Geng X, Wang J, Zhou X, Jing J, Pan W. Systematic Review with Meta-analysis: Association of Helicobacter pylori Infection with Esophageal Cancer. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2019;2019:1953497. doi: 10.1155/2019/1953497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tiomny E, Arber N, Moshkowitz M, Peled Y, Gilat T. Halitosis and Helicobacter pylori. A possible link? J Clin Gastroenterol. 1992;15:236–237. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199210000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.HajiFattahi F, Hesari M, Zojaji H, Sarlati F. Relationship of Halitosis with Gastric Helicobacter Pylori Infection. J Dent (Tehran) 2015;12:200–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Anbari F, Ashouri Moghaddam A, Sabeti E, Khodabakhshi A. Halitosis: Helicobacter pylori or oral factors. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12556. doi: 10.1111/hel.12556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pappachan JM, Babu S, Krishnan B, Ravindran NC. Non-alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: A Clinical Update. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2017;5:384–393. doi: 10.14218/JCTH.2017.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gen R, Demir M, Ataseven H. Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on insulin resistance, serum lipids and low-grade inflammation. South Med J. 2010;103:190–196. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e3181cf373f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adolph TE, Grander C, Grabherr F, Tilg H. Adipokines and Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease: Multiple Interactions. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18 doi: 10.3390/ijms18081649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vcev A, Nakić D, Mrden A, Mirat J, Balen S, Ruzić A, Persić V, Soldo I, Matijević M, Barbić J, Matijević V, Bozić D, Radanović B. Helicobacter pylori infection and coronary artery disease. Coll Antropol. 2007;31:757–760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korponay-Szabó IR, Halttunen T, Szalai Z, Laurila K, Király R, Kovács JB, Fésüs L, Mäki M. In vivo targeting of intestinal and extraintestinal transglutaminase 2 by coeliac autoantibodies. Gut. 2004;53:641–648. doi: 10.1136/gut.2003.024836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu R, Liu Q, He Y, Shi W, Xu Q, Yuan Q, Lin Q, Li B, Ye L, Min Y, Zhu P, Shao Y. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and nonalcoholic fatty liver: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019;98:e17781. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000017781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waluga M, Kukla M, Żorniak M, Bacik A, Kotulski R. From the stomach to other organs: Helicobacter pylori and the liver. World J Hepatol. 2015;7:2136–2146. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v7.i18.2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nilsson HO, Mulchandani R, Tranberg KG, Stenram U, Wadström T. Helicobacter species identified in liver from patients with cholangiocarcinoma and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:323–324. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.21382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Huang J, Cui J. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients with Chronic Hepatic Disease. Chin Med J (Engl) 2017;130:149–154. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.197980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Calvet X, Sanfeliu I, Musulen E, Mas P, Dalmau B, Gil M, Bella MR, Campo R, Brullet E, Valero C, Puig J. Evaluation of Helicobacter pylori diagnostic methods in patients with liver cirrhosis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:1283–1289. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsuchiya Y, Mishra K, Kapoor VK, Vishwakarma R, Behari A, Ikoma T, Asai T, Endoh K, Nakamura K. Plasma Helicobacter pylori Antibody Titers and Helicobacter pylori Infection Positivity Rates in Patients with Gallbladder Cancer or Cholelithiasis: a Hospital-Based Case-Control Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2018;19:1911–1915. doi: 10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.7.1911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yucebilgili K, Mehmetoĝlu T, Gucin Z, Salih BA. Helicobacter pylori DNA in gallbladder tissue of patients with cholelithiasis and cholecystitis. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2009;3:856–859. doi: 10.3855/jidc.334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guraya SY, Ahmad AA, El-Ageery SM, Hemeg HA, Ozbak HA, Yousef K, Abdel-Aziz NA. The correlation of Helicobacter Pylori with the development of cholelithiasis and cholecystitis: the results of a prospective clinical study in Saudi Arabia. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2015;19:3873–3880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cen L, Pan J, Zhou B, Yu C, Li Y, Chen W, Shen Z. Helicobacter Pylori infection of the gallbladder and the risk of chronic cholecystitis and cholelithiasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2018;23 doi: 10.1111/hel.12457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Abro AH, Haider IZ, Ahmad S. Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with calcular cholecystitis: a hospital based study. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2011;23:30–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Arismendi-Morillo G, Cardozo-Ramones V, Torres-Nava G, Romero-Amaro Z. [Histopathological study of the presence of Helicobacter pylori-type bacteria in surgical specimens from patients with chronic cholecystitis] Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;34:449–453. doi: 10.1016/j.gastrohep.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kaptan K, Beyan C, Ural AU, Cetin T, Avcu F, Gülşen M, Finci R, Yalçín A. Helicobacter pylori--is it a novel causative agent in Vitamin B12 deficiency? Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1349–1353. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.9.1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mwafy SN, Afana WM. Hematological parameters, serum iron and vitamin B12 levels in hospitalized Palestinian adult patients infected with Helicobacter pylori: a case-control study. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2018;40:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2017.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Serin E, Gümürdülü Y, Ozer B, Kayaselçuk F, Yilmaz U, Koçak R. Impact of Helicobacter pylori on the development of vitamin B12 deficiency in the absence of gastric atrophy. Helicobacter. 2002;7:337–341. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2002.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malfertheiner P, Megraud F, O'Morain CA, Gisbert JP, Kuipers EJ, Axon AT, Bazzoli F, Gasbarrini A, Atherton J, Graham DY, Hunt R, Moayyedi P, Rokkas T, Rugge M, Selgrad M, Suerbaum S, Sugano K, El-Omar EM European Helicobacter and Microbiota Study Group and Consensus panel. Management of Helicobacter pylori infection-the Maastricht V/Florence Consensus Report. Gut. 2017;66:6–30. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-312288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choe YH, Kim SK, Son BK, Lee DH, Hong YC, Pai SH. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of Helicobacter pylori eradication for iron-deficiency anemia in preadolescent children and adolescents. Helicobacter. 1999;4:135–139. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.1999.98066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ferrara M, Capozzi L, Russo R. Influence of Helicobacter pylori infection associated with iron deficiency anaemia on growth in pre-adolescent children. Hematology. 2009;14:173–176. doi: 10.1179/102453309X402287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ashorn M, Ruuska T, Mäkipernaa A. Helicobacter pylori and iron deficiency anaemia in children. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2001;36:701–705. doi: 10.1080/003655201300191950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guarneri C, Lotti J, Fioranelli M, Roccia MG, Lotti T, Guarneri F. Possible role of Helicobacter pylori in diseases of dermatological interest. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2017;31:57–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ram M, Barzilai O, Shapira Y, Anaya JM, Tincani A, Stojanovich L, Bombardieri S, Bizzaro N, Kivity S, Agmon Levin N, Shoenfeld Y. Helicobacter pylori serology in autoimmune diseases - fact or fiction? Clin Chem Lab Med. 2013;51:1075–1082. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Uemura N, Okamoto S, Yamamoto S, Matsumura N, Yamaguchi S, Yamakido M, Taniyama K, Sasaki N, Schlemper RJ. Helicobacter pylori infection and the development of gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:784–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa001999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Buechner SA. Rosacea: an update. Dermatology. 2005;210:100–108. doi: 10.1159/000082564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Szlachcic A, Sliwowski Z, Karczewska E, Bielański W, Pytko-Polonczyk J, Konturek SJ. Helicobacter pylori and its eradication in rosacea. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1999;50:777–786. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Saleh P, Naghavi-Behzad M, Herizchi H, Mokhtari F, Mirza-Aghazadeh-Attari M, Piri R. Effects of Helicobacter pylori treatment on rosacea: A single-arm clinical trial study. J Dermatol. 2017;44:1033–1037. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.13878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang X. Relationship between Helicobacter pylori and Rosacea: review and discussion. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:318. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3232-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gravina A, Federico A, Ruocco E, Lo Schiavo A, Masarone M, Tuccillo C, Peccerillo F, Miranda A, Romano L, de Sio C, de Sio I, Persico M, Ruocco V, Riegler G, Loguercio C, Romano M. Helicobacter pylori infection but not small intestinal bacterial overgrowth may play a pathogenic role in rosacea. United European Gastroenterol J. 2015;3:17–24. doi: 10.1177/2050640614559262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jørgensen AR, Egeberg A, Gideonsson R, Weinstock LB, Thyssen EP, Thyssen JP. Rosacea is associated with Helicobacter pylori: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017;31:2010–2015. doi: 10.1111/jdv.14352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rendon A, Schäkel K. Psoriasis Pathogenesis and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20061475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mesquita PM, Diogo A Filho, Jorge MT, Berbert AL, Mantese SA, Rodrigues JJ. Relationship of Helicobacter pylori seroprevalence with the occurrence and severity of psoriasis. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92:52–57. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20174880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Halasz CL. Helicobacter pylori antibodies in patients with psoriasis. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:95–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu M, Zhang R, Ni P, Chen S, Duan G. Helicobacter pylori Infection and Psoriasis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Medicina (Kaunas) 2019;55 doi: 10.3390/medicina55100645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hon KL, Leung AKC, Ng WGG, Loo SK. Chronic Urticaria: An Overview of Treatment and Recent Patents. Recent Pat Inflamm Allergy Drug Discov. 2019;13:27–37. doi: 10.2174/1872213X13666190328164931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Antia C, Baquerizo K, Korman A, Bernstein JA, Alikhan A. Urticaria: A comprehensive review: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and work-up. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:599–614. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim HJ, Kim YJ, Lee HJ, Hong JY, Park AY, Chung EH, Lee SY, Lee JS, Park YL, Lee SH, Kim JE. Systematic review and meta-analysis: Effect of Helicobacter pylori eradication on chronic spontaneous urticaria. Helicobacter. 2019;24:e12661. doi: 10.1111/hel.12661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gu H, Li L, Gu M, Zhang G. Association between Helicobacter pylori Infection and Chronic Urticaria: A Meta-Analysis. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:486974. doi: 10.1155/2015/486974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pratt CH, King LE, Jr, Messenger AG, Christiano AM, Sundberg JP. Alopecia areata. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17011. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2017.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Behrangi E, Mansouri P, Agah S, Ebrahimi Daryani N, Mokhtare M, Azizi Z, Ramezani Ghamsari M, Rohani Nasab M, Azizian Z. Association between Helicobacter Pylori Infection and Alopecia Areata: A Study in Iranian Population. Middle East J Dig Dis. 2017;9:107–110. doi: 10.15171/mejdd.2017.59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Neunert CE. Current management of immune thrombocytopenia. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2013;2013:276–282. doi: 10.1182/asheducation-2013.1.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Takahashi T, Yujiri T, Shinohara K, Inoue Y, Sato Y, Fujii Y, Okubo M, Zaitsu Y, Ariyoshi K, Nakamura Y, Nawata R, Oka Y, Shirai M, Tanizawa Y. Molecular mimicry by Helicobacter pylori CagA protein may be involved in the pathogenesis of H. pylori-associated chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol. 2004;124:91–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04735.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kodama M, Kitadai Y, Ito M, Kai H, Masuda H, Tanaka S, Yoshihara M, Fujimura K, Chayama K. Immune response to CagA protein is associated with improved platelet count after Helicobacter pylori eradication in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Helicobacter. 2007;12:36–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2007.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gasbarrini A, Franceschi F, Tartaglione R, Landolfi R, Pola P, Gasbarrini G. Regression of autoimmune thrombocytopenia after eradication of Helicobacter pylori. Lancet. 1998;352:878. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)60004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Rocha AM, Souza C, Melo FF, Clementino NC, Marino MC, Rocha GA, Queiroz DM. Cytokine profile of patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia affects platelet count recovery after Helicobacter pylori eradication. Br J Haematol. 2015;168:421–428. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kim BJ, Kim HS, Jang HJ, Kim JH. Helicobacter pylori Eradication in Idiopathic Thrombocytopenic Purpura: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Trials. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2018;2018:6090878. doi: 10.1155/2018/6090878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ozelo MC, Colella MP, de Paula EV, do Nascimento ACKV, Villaça PR, Bernardo WM. Guideline on immune thrombocytopenia in adults: Associação Brasileira de Hematologia, Hemoterapia e Terapia Celular. Project guidelines: Associação Médica Brasileira - 2018. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2018;40:50–74. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Mindel JS, Rosenberg EW. Is Helicobacter pylori of interest to ophthalmologists? Ophthalmology. 1997;104:1729–1730. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(97)30035-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Baim AD, Movahedan A, Farooq AV, Skondra D. The microbiome and ophthalmic disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2019;244:419–429. doi: 10.1177/1535370218813616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Saccà SC, Vagge A, Pulliero A, Izzotti A. Helicobacter pylori infection and eye diseases: a systematic review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2014;93:e216. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000000216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Zeng J, Liu H, Liu X, Ding C. The Relationship Between Helicobacter pylori Infection and Open-Angle Glaucoma: A Meta-Analysis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2015;56:5238–5245. doi: 10.1167/iovs.15-17059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kountouras J, Mylopoulos N, Chatzopoulos D, Zavos C, Boura P, Konstas AG, Venizelos J. Eradication of Helicobacter pylori may be beneficial in the management of chronic open-angle glaucoma. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1237–1244. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.11.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Daković Z, Vesić S, Vuković J, Milenković S, Janković-Terzić K, Dukić S, Pavlović MD. Ocular rosacea and treatment of symptomatic Helicobacter pylori infection: a case series. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2007;16:83–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bagheri M, Rashe Z, Ahoor MH, Somi MH. Prevalence of Helicobacter pylori Infection in Patients with Central Serous Chorioretinopathy: A Review. Med Hypothesis Discov Innov Ophthalmol. 2017;6:118–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Saccà SC, Pascotto A, Venturino GM, Prigione G, Mastromarino A, Baldi F, Bilardi C, Savarino V, Brusati C, Rebora A. Prevalence and treatment of Helicobacter pylori in patients with blepharitis. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47:501–508. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cotticelli L, Borrelli M, D'Alessio AC, Menzione M, Villani A, Piccolo G, Montella F, Iovene MR, Romano M. Central serous chorioretinopathy and Helicobacter pylori. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2006;16:274–278. doi: 10.1177/112067210601600213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tsang KW, Lam WK, Chan KN, Hu W, Wu A, Kwok E, Zheng L, Wong BC, Lam SK. Helicobacter pylori sero-prevalence in asthma. Respir Med. 2000;94:756–759. doi: 10.1053/rmed.2000.0817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wang Q, Yu C, Sun Y. The association between asthma and Helicobacter pylori: a meta-analysis. Helicobacter. 2013;18:41–53. doi: 10.1111/hel.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Chen C, Xun P, Tsinovoi C, He K. Accumulated evidence on Helicobacter pylori infection and the risk of asthma: A meta-analysis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119:137–145.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lankarani KB, Honarvar B, Athari SS. The Mechanisms Underlying Helicobacter Pylori-Mediated Protection against Allergic Asthma. Tanaffos. 2017;16:251–259. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.D'Elios MM, Codolo G, Amedei A, Mazzi P, Berton G, Zanotti G, Del Prete G, de Bernard M. Helicobacter pylori, asthma and allergy. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2009;56:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2009.00537.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Freire de Melo F, Rocha AM, Rocha GA, Pedroso SH, de Assis Batista S, Fonseca de Castro LP, Carvalho SD, Bittencourt PF, de Oliveira CA, Corrêa-Oliveira R, Magalhães Queiroz DM. A regulatory instead of an IL-17 T response predominates in Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis in children. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:341–347. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fouda EM, Kamel TB, Nabih ES, Abdelazem AA. Helicobacter pylori seropositivity protects against childhood asthma and inversely correlates to its clinical and functional severity. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2018;46:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.aller.2017.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Okada H, Kuhn C, Feillet H, Bach JF. The 'hygiene hypothesis' for autoimmune and allergic diseases: an update. Clin Exp Immunol. 2010;160:1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2010.04139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chen Y, Blaser MJ. Inverse associations of Helicobacter pylori with asthma and allergy. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:821–827. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.8.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Miftahussurur M, Nusi IA, Graham DY, Yamaoka Y. Helicobacter, Hygiene, Atopy, and Asthma. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1034. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Katz Sand I. Classification, diagnosis, and differential diagnosis of multiple sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 2015;28:193–205. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0000000000000206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li W, Minohara M, Su JJ, Matsuoka T, Osoegawa M, Ishizu T, Kira J. Helicobacter pylori infection is a potential protective factor against conventional multiple sclerosis in the Japanese population. J Neuroimmunol. 2007;184:227–231. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jaruvongvanich V, Sanguankeo A, Jaruvongvanich S, Upala S. Association between Helicobacter pylori infection and multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;7:92–97. doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2016.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Yao G, Wang P, Luo XD, Yu TM, Harris RA, Zhang XM. Meta-analysis of association between Helicobacter pylori infection and multiple sclerosis. Neurosci Lett. 2016;620:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Salama NR, Hartung ML, Müller A. Life in the human stomach: persistence strategies of the bacterial pathogen Helicobacter pylori. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:385–399. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cossu D, Yokoyama K, Hattori N. Bacteria-Host Interactions in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2966. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Efthymiou G, Dardiotis E, Liaskos C, Marou E, Tsimourtou V, Rigopoulou EI, Scheper T, Daponte A, Meyer W, Sakkas LI, Hadjigeorgiou G, Bogdanos DP. Immune responses against Helicobacter pylori-specific antigens differentiate relapsing remitting from secondary progressive multiple sclerosis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:7929. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07801-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Lane CA, Hardy J, Schott JM. Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Neurol. 2018;25:59–70. doi: 10.1111/ene.13439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Shindler-Itskovitch T, Ravona-Springer R, Leibovitz A, Muhsen K. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Association between Helicobacterpylori Infection and Dementia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;52:1431–1442. doi: 10.3233/JAD-160132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Fu P, Gao M, Yung KKL. Association of Intestinal Disorders with Parkinson's Disease and Alzheimer's Disease: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11:395–405. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.9b00607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wang XL, Zeng J, Yang Y, Xiong Y, Zhang ZH, Qiu M, Yan X, Sun XY, Tuo QZ, Liu R, Wang JZ. Helicobacter pylori filtrate induces Alzheimer-like tau hyperphosphorylation by activating glycogen synthase kinase-3β. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;43:153–165. doi: 10.3233/JAD-140198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kountouras J, Tsolaki F, Tsolaki M, Gavalas E, Zavos C, Polyzos SA, Boziki M, Katsinelos P, Kountouras C, Vardaka E, Tagarakis GI, Deretzi G. Helicobacter pylori-related ApoE 4 polymorphism may be associated with dysphagic symptoms in older adults. Dis Esophagus. 2016;29:842. doi: 10.1111/dote.12364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Doulberis M, Kotronis G, Thomann R, Polyzos SA, Boziki M, Gialamprinou D, Deretzi G, Katsinelos P, Kountouras J. Review: Impact of Helicobacter pylori on Alzheimer's disease: What do we know so far? Helicobacter. 2018;23 doi: 10.1111/hel.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Franceschi F, Gasbarrini A, Polyzos SA, Kountouras J. Extragastric Diseases and Helicobacter pylori. Helicobacter. 2015;20 Suppl 1:40–46. doi: 10.1111/hel.12256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kountouras J, Zavos C, Polyzos SA, Deretzi G. The gut-brain axis: interactions between Helicobacter pylori and enteric and central nervous systems. Ann Gastroenterol. 2015;28:506. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Antony PM, Diederich NJ, Krüger R, Balling R. The hallmarks of Parkinson's disease. FEBS J. 2013;280:5981–5993. doi: 10.1111/febs.12335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Capriotti T, Terzakis K. Parkinson Disease. Home Healthc Now. 2016;34:300–307. doi: 10.1097/NHH.0000000000000398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]