Abstract

The application of CRISPR technology has greatly facilitated the creation of transgenic Caenorhabditis elegans lines. However, methods to insert multi-kilobase DNA constructs remain laborious even with these advances. Here, I describe a new approach for introducing large DNA constructs into the C. elegans genome at specific sites using a combination of Flp and Cre recombinases. The system utilizes specialized integrated landing sites that express GFP ubiquitously flanked by single loxP, FRT, and FRT3 sites. DNA sequences of interest are inserted into an integration vector that contains a sqt-1 self-excising cassette and FRT and FRT3 sites. Plasmid DNA is injected into the germline of landing site animals. Transgenic animals are identified as Rol progeny, and the sqt-1 marker is subsequently excised with heat shock Cre expression. Integration events were obtained at a rate of approximately one integration per three injected F0 animals—a rate substantially higher than any current approach. To demonstrate the robustness of the approach, I compared the efficiency of the Gal4/UAS, QF (and QF2)/QUAS, tetR(and rtetR)/tetO, and LexA/lexO bipartite expression systems by assessing expression levels in combinations of driver and reporter GFP constructs and a direct promoter GFP fusion each integrated at multiple sites in the genome. My data demonstrate that all four bipartite systems are functional in C. elegans. Although the new integration system has several limitations, it greatly reduces the effort required to create single-copy insertions at defined sites in the C. elegans genome.

Keywords: bipartite expression systems, Cre recombinase, integration

TRANSGENESIS is an integral part of virtually every research program using C . elegans. Transgenes are used to express genes in specific cell types (Hunt-Newbury et al. 2007), to tag and visualize subcellular components (Nonet 1999), to monitor concentrations of signaling molecules in real time using genetically encoded sensors (Kerr 2006), to perturb cellular functions using toxins (Davis et al. 2008), targeted protein degradation (Zhang et al. 2015) or RNA interference (Esposito et al. 2007), and to create optogenetic tools (Zhang et al. 2007). Currently, genome integration of new molecularly encoded tools remains the limiting factor in the development of these valuable resources. While CRISPR technology has greatly increased the efficiency of small genome modifications (Dickinson and Goldstein 2016), insertion of larger DNA elements remains inefficient.

C. elegans single-copy transgenic lines are also sometimes of limited utility due to low expression levels. In both Drosophila and mammalian systems, bipartite reporter systems have been used widely to overcome this issue (Schönig et al. 2010; Caygill and Brand 2016; Riabinina and Potter 2016). These systems combine two distinct, often unlinked, transgenic elements: (1) a driver consisting of a strongly activating transcription factor (TF) under the control of the promoter of interest, and (2) a reporter consisting of a promoter specifically responsive to the driver TF controlling the expression of the tool of interest. Constitutive, drug-inducible and drug-repressible bipartite systems have been developed, and have been particularly well refined in Drosophila (Caygill and Brand 2016; Riabinina and Potter 2016). The most common systems are one based on the DNA-binding domain of the Escherichia coli tetracycline repressor tetR and a tetO operator (Gossen and Bujard 1992), and another based on the DNA-binding domain of the yeast galactose regulatory protein Gal4 and the UAS regulatory element (Brand and Perrimon 1993). In addition, systems based on the LexA DNA-binding domain and a lexO operator (Fashena et al. 2000), and the Neurospora transcription factor QF and a QUAS binding site have been widely adopted (Potter et al. 2010). The activity of tetR and QF systems can be controlled by addition of small molecules, and the activity of the Gal4 TF can be modulated by the repressor GAL80, providing multiple different approaches to controlling expression both in space and time.

In C. elegans, development of bipartite reporter systems has been much more limited. A QF/QUAS system was introduced almost a decade ago (Wei et al. 2012), and, more recently, Gal4/UAS and hybrid tetR-QF/tetO bipartite systems were developed (Wang et al. 2017; Mao et al. 2019). However, only the QF/QUAS system was shown to function in single copy, and none of the systems has been widely adopted. One factor limiting the development of these systems is the methodology available to create transgenic animals.

A variety of different technologies have been developed since the late 1980s to create transgenic C. elegans (Nance and Frøkjær-Jensen 2019). The first transgenic method predominantly created semistable extrachromosomal arrays, which are very valuable for mosaic analysis and often function well enough to perform many transgenic assays such as testing for rescue of a mutant with a cloned gene (Stinchcomb et al. 1985; Mello et al. 1991). However, due to their inherent variability, these arrays are not suitable for assays that require consistent expression across animals or cells. Methods to integrate these arrays were developed to create genetically stable transgenic animals (Way et al. 1991). Subsequently, ballistic bombardment was developed as an alternate method to directly generate integrants (Praitis et al. 2001). However, ballistic transformation is limited because insertions occur at random positions, are of ill-defined structure, and are relatively laborious to generate. More recently, the development of genetically engineered transposons in C. elegans led to two new methods for integration: MosSCI and miniMos integration (Frøkjær-Jensen et al. 2008, 2014). MosSCI was the first method that permitted reliable integration at specific sites (though limited to sites of Mos1 transposon insertions). MosSCI improved integration efficiencies over bombardment but remains much more laborious than creating an extrachromosomal array. miniMos, a cargo-accepting mini-transposon can be much more efficiently integrated into the genome, but the sites of integration are random. Most recently, CRISPR technology has greatly increased the efficiency of creating transgenic C. elegans with insertions of small genetic elements (<1 kb), but larger DNA inserts remain laborious to integrate in a site-specific manner (Dickinson and Goldstein 2016). Thus, in developing new transgenic animals, C. elegans researchers must decide whether to use efficient methods to integrate at random sites, or less efficient methods to target a specific site.

Flp is a recombinase that catalyzes recombination between FRT sites, which has been widely utilized to manipulate genomes both in germline and somatic tissue (Turan et al. 2013). Several distinct uses of Flp technology have been developed previously in C. elegans (Davis et al. 2008; Voutev and Hubbard 2008; Muñoz-Jiménez et al. 2017). These “Flp-out” tools have only been used to alter gene expression by manipulating DNA elements containing FRT sites previously integrated into the genome or incorporated into extrachromosomal arrays. However, in other systems Flp/FRT approaches have been developed to insert DNA sequences at specific sites in a genome. The simplest systems integrate an entire plasmid into the genome at an FRT site. However, this insertion event is easily reversed by Flp and inserting sequences requires a pulse of recombinase to trap the insertion (O’Gorman et al. 1991; Koch et al. 2000). More recently, recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) methods have been developed that use two distinct FRT site variants to create an insertion that is stable even in the presence of recombinase (Schlake and Bode 1994; Turan et al. 2013). This type of cassette exchange approach has been used widely in tissue culture cells (Callesen et al. 2016), and whole organisms, including Drosophila, where other recombinases including Cre and ϕ C-31 have also been used (Oberstein et al. 2005; Bateman et al. 2006). However, an RMCE system has not been developed for C. elegans.

I sought to determine if RMCE technology could be adapted to C. elegans. One complication in C. elegans is that DNA can be semistably inherited without inserting into the chromosome (Stinchcomb et al. 1985). DNA injected into the germline forms large arrays consisting of hundreds to thousands of copies of the injected plasmids. These arrays assemble, at least in part, by homologous recombination between plasmid molecules forming concatemers (Mello et al. 1991). Nonhomologous end-joining likely also occurs since extrachromosomal arrays can be created that contain multiple plasmids that do not contain homologous sequences, or that incorporate co-injected linear genomic DNA (Stinchcomb et al. 1985; Kelly et al. 1997). These large arrays replicate and are propagated to daughter cells both in the germline and soma, but the efficiency of transmission is not 100%, yielding mosaic animals. A robust system for integration must distinguish easily between integration events and these extrachromosomal events.

Here, I describe a method to integrate plasmid-derived sequences into specific sites at improved efficiency via a strategy that utilizes an RMCE approach by combining two recombinase systems. Plasmid sequences are integrated into specialized landing sites using the Flp/FRT system, then the markers utilized to detect integration events are excised using Cre/loxP, leaving an insertion containing only the sequences of interest and flanking loxP and FRT sites. I then use RMCE to test the functionality of four different bipartite reporter system in single copy.

Materials and Methods

Nomenclature

C. elegans RMCE insertions into a landing site locus (e.g., jsTi1493) should technically be called jsTi1493 jsSi# according to C. elegans nomenclature rules (Tuli et al. 2018), but were referred to in the latter paper as jsSi# except when the position of the insertion was critical.

C. elegans strain maintenance

C. elegans was grown on NGM plates seeded with E. coli OP-50 on 6-cm plates. Strains were maintained at RT (∼22.5°) unless otherwise noted. Doxycycline hyclate (GoldBio, St. Louis, MO) was added to plates by diluting a 25 mg/ml stock (6% DMSO; stored at −20°) to 100 ng/ml in sterile H2O, and pipetting 100 µl onto the plate. Induction of rtetR-QFAD regulated genes was robust by 24 hr after addition of doxycycline.

Microscopy

Screening of worms for fluorescence during the RMCE protocol was performed on a Leica (Heerbrugg, Switzerland) MZ16F FluoCombi III microscope with a planapo 1X and planapo 5X LWD objective for high power observation illuminated using a Lumencor (Beaverton, OR) Sola light source.

For quantification of fluorescence, worms were mounted on 2% agarose pads in a 2 µl drop of 1 mM levamisole in phosphate-buffered saline; 10–20 L4 animals were typically placed on a single slide. Animals were imaged using a 10× air (na 0.45) or 40× air (na 0.75) lens on an Olympus (Center Valley, PA) BX-60 microscope equipped with a Qimaging (Surrey, BC, Canada) Retiga EXi monochrome CCD camera, a Lumencor AURA LED light source, Semrock (Rochester, NY) GFP-3035B and mCherry-A-000 filter sets, and a Tofra (Palo Alto, CA) focus drive, run using Micro-Manager 2.0β software (Edelstein et al. 2014). For quantification, all images were taken using identical LED power and camera settings for all data in a comparison group (typically 50% LED power and either 50, 100, or 200 msec camera exposures with a gain of 1 and 0 offset depending on the strength of the brightest strain in the group). Images with the nucleus of the soma or the process in focus were used for quantification. Images were quantified using the FIJI version of ImageJ software (Schindelin et al. 2012). Specifically, I calculated the integrated density of a circular region of interest (ROI) of 60 pixels diameter centered over the soma, and then I subtracted the integrated density of similar sized ROI in an adjacent area of background. Processes were quantified in a similar manner, but using a smaller 40 pixel diameter ROI, positioned with the process running through the center of the ROI, and a background ROI positioned in an area adjacent to the process. Data plots were created using PlotsOfData (Postma and Goedhart 2019).

Plasmid micro-injections

Plasmids for injection were prepared using QIAprep Spin Miniprep columns (Qiagen, Venlo, The Netherlands) using the manufacturer’s protocol, but eluting the DNA in TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 0.1 mM EDTA) instead of the provided elution buffer. Plasmids were combined at experiment specific concentrations (see Supplemental Materials, Table S1 and Table S2) using TE to dilute the samples to final concentrations. Bee-sting style needles used for injections were pulled from 1.0 mm BF-100-58-15 glass capillaries (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA) with a model Sutter P97 pipette puller with an FB255B box filament. DNA mixtures were centrifuged at 15,000 g for 5 min before loading into the pipette to reduce clogging. DNA injections were performed on a Zeiss axiovert 100 microscope equipped with a glide stage, DIC optics, 5× and 40× air (na 0.75) lens, a World Precision Instruments (Sarasota, FL) 3301L micromanipulator, and a Medical Instruments Corp (Greenvale, NY) PLI-90 pressure injector. L4 animals were picked in the late afternoon the day before morning injections, and incubated at 20° overnight. Animals were mounted individually on 2% dried agar pads under Halocarbon 700 oil (Halocarbon product, River Edge, NJ). Approximately two-thirds of animals were injected in only a single gonad. The volume injected is ill-defined, but likely around to 0.1–0.5 nl based on measuring the volume of mock injections into oil. After injection, animals were teased off the pad, and placed in 30 µl of recovery buffer (5 mM HEPES pH 7.2, 3 mM CaCl2, 3 mM MgCl2, 66 mM NaCl, 2.4 mM KCl, 4% glucose) on NGM plates. Successful injections were defined as injections with surviving animals where flow of injected DNA was observed and consistent with a gonad injection. Only successfully injected animals were included in the analysis. These represent ∼80% of injected animals under typical conditions. Injected animals were grown at 25°, except in two experiments where half the injected animals were grown at 22.5°. This temperature was used because a subset of injections (miniMos) has been observed to work more efficiently at high temperature (Frøkjær-Jensen et al. 2014), and to take advantage of the rapid generation time at 25°. No experiments were performed to quantify temperature effects on Flp-mediated integration.

To assess the localization of plasmid DNA in the germline, a mixture of 50 nM 80mer 5′ FITC labeled oligonucleotide NMo1625 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and 100 ng/µl Cy3-conjugated pRF4 plasmid were co-injected into the germline of adult N2 animals as described above. pRF4 was labeled using a Mirus Bio (Madison, WI) Label IT Cy3 nucleic acid labeling kit (Cat # 3625) using the manufacturer’s recommended protocol at a 0.1:1 reagent to DNA ratio. The labeled DNA was purified using an ethanol precipitation. After injection, some animals were mounted and imaged at 40X in the GFP and mCherry channels as described in the microscopy methods. However, the light source for this experiment was a X-Cite 120 mercury lamp (EXFO Photonics Solutions; Mississauga, Ontario, Canada) rather than an LED. Other animals were allowed to lay eggs to confirm the functionality of the labeled DNA through identification of F1 Rol animals.

Isolation of miniMos insertions

A mixture of a miniMos plasmid (NM3649, NM3681, or NM3689 at 10–25 ng/µl), pCFJ601 (50 ng/µl), pGH8 (2 ng/µl), and pCFJ90 (4 ng/µl) was injected into N2 animals as described above. F1 Rol progeny were picked and pooled at five to six per plate. F1 plates were screened for F2 Rol animals that did not express detectable levels of mCherry in the pharynx or nervous system on an epifluorescence dissecting microscope, and these were cloned. F2 Rol animals which segregated Rol progeny in a 3:1 Mendelian ratio were analyzed further. F3 animals that segregated 100% Rol were examined for appropriate fluorescence expression, and complete absence of detectable pharyngeal muscle or neuronal mCherry expression and analyzed using inverse PCR to determine the position of miniMos insertion(s). The insertions were then heat shocked to excise the SEC. A total of 12–15 young L1/L2 animals were heat shocked at 34° for 4 hr, or 37° for 40 min, and the progeny were screened for non-Rol animals. jsTi1453 was outcrossed to bqSi711 and to him-8(e1489), jsTi1485 was outcrossed to jsSi1487, and jsTi1490, jsTi1492, and jsTi1493 were outcrossed to N2.

Isolation of RMCE insertions

DNAs (see Table S1 and Table S2) were injected into a landing site strain (NM5161, NM5176, NM5178, or NM5179) as described above. Injected P0 animals were pooled at three animals per plate, and the plates were screened 2.5 and 3 days after injection for Rol progeny. F1 Rol progeny were picked and pooled (usually five to six animals per plate). The F1 Rol plates were incubated at 25°, and 2.5 and 3 days later the plates were screened for F2 Rol progeny. F2 Rol progeny were picked and singled (if only a few Rol animals were present). When many Rol animals were present on a plate, the Rol animals were examined under epifluorescence to determine if any were somatic GFP(−) indicating that they were homozygous insertion animals. If homozygous animals were present, two or three were cloned. If all animals were GFP(+), two were singled and the others were pooled. F3 homozygous Rol somatic GFP(−) progeny were cloned. F4 late L1 or early L2 homozygous animals were heat shocked to excise the SEC. A total of 15–20 animals were placed on each of three plates and heat shocked either 40 min at 37°, 4 hr at 34°, or 18 hr at 30°. The 18-hr heat shock was found to be most reliable. Non-Rol animals were cloned to establish an insertion line. Molecular analysis of the insertions was performed by long range PCR followed by restriction digestion for all insertions, and sequence analysis for a subset of insertions. To remove the bqSi711 transgene, jsTi1453; him-8(e1489) males were crossed to an insertion, then after isolating him-8/bqSi711; insertion/jsTi1453 cross progeny, him-8; insertion animals were isolated. I quantified the integration rates by recording the number of P0 animals injected, the number of F1 Rol animals obtained, the number of F2 Rol animals obtained and the number of F2 Rol animals yielding integration events. To minimize the number of plates requiring examination, P0, F1, and some F2 animals were pooled on plates.

Plasmid constructions

All PCR amplifications for plasmid constructions were performed using Q5 polymerase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Most PCR reactions were performed using the following conditions: 98° for 0:30, followed by 30 cycles of 98° for 0:10, 62° for 0:30, 72° for 1:00/kb). Occasionally, the first five cycles were replaced by (98° for 0:10, 55° for 0:30, and 72° for 1:00/kb) for oligonucleotide pairs with a low annealing temperature. PCR products were digested with DpnI to remove template if amplified from a plasmid, then purified using a standard Monarch (New England Biolabs) column purification procedure. Restriction enzymes, T4 DNA ligase, and polynucleotide kinase were purchased from New England Biolabs. The E. coli strain DH5α was used for all transformations. Sequencing was performed by GENEWIZ (South Plainfield, NJ), oligonucleotides were obtained from IDT (Coralville, IA), and synthetic DNA fragment were purchased from Twist Biosciences (South San Francisco, CA). The sequence of all vectors and synthetic fragments is provided in Table S3. In Fusion (TaKaRa Bio, Kusatsu, Shiga, Japan) reactions were performed as recommended by the manufacturer. Golden Gate (GG) reactions (Engler et al. 2008) were performed by mixing 50 fmol of the vector, 60 fmol of each insert plasmid or PCR fragment, and 150 fmol of each hybridized oligonucleotide pair and diluting the mix to 10 µl with TE. Oligonucleotides pairs were annealed by heating a 0.5 nM solution of each oligonucleotide in 50 mM KAc, 5 mM Tris pH 7.5–95° for 2 min, then slow cooling at −0.1°/sec to RT; 1 µl of the DNA mix was added to 1 µl of 6× Sap buffer (300 mM Tris-HCl, 25 mM KAc, 60 mM MgCl2, 60 mM dithiothreitol, 6 mM ATP, pH 7.5 @ 25°), 3.5 µl H2O, 0.5 µl of SapI or BsaI, and 0.25 µl T4 DNA ligase. When oligonucleotides were used, 0.25 µl of polynucleotide kinase was also added. The reactions were incubated 15 min at 37°, 5 min at 16°, followed by 10 cycles of 2 min at 37°, and 2 min at 16°, followed by 5 min at 37°, and 20 min at 65°. A 0.5 µl aliquot of the reaction was transformed into DH5α. Typically, hundreds to thousands of transformants were obtained, and the majority were correctly assembled clones. A detailed description of the construction of all plasmids is provided in Supplemental methods.

Preparation of genomic DNA

Genomic DNA was prepared from worms collected from a single, recently starved, 60-mm plate, and frozen in 50 µl of water. The worm pellet was thawed, and 150 µl of 2 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris 7.5, 0.5% SDS, and 100 µg/ml Proteinase K was added, and the worms were lysed for 1 hr at 60° with occasional mixing. To remove RNA, 2 µl of 10 mg/ml RNase A was added, and incubated for 30 min at 37°. However, removal of RNA is not necessary for either long-range PCR or inverse-PCR. Next, 200 µl of 3 M guanidine HCl, 3.75 M NH4Ac, pH 6 was added, followed by 200 µl of 96% ethanol. The solution was loaded on a Qiagen QIAquick (PCR purification) column, washed two times with 600 µl of PE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 80% ethanol), and eluted with 100 µl of TE. Yields were typically ∼1 µg of genomic DNA.

Inverse PCR of mini Mos insertions

Genomic DNA (15 ng) was digested with Sau3A or HpaII in a 10 µl reaction for 90 min and heat inactivated at 80° for 20 min. The inactivated digestion was diluted with 40 µl of 1× T4 DNA ligase buffer, and 0.16 µl of T4 DNA ligase was added and incubated at 16° for 1 hr. Circular products were amplified using two rounds of PCR. In the first round, 2 µl of the ligation was amplified in a 15 µl reaction using NMo5078/5085 and cycling conditions: 0:30 @ 98°, 30 X [0:10 @ 98°,0:30 @ 64°, 1:00 @ 72°]. A 1 µl aliquot of a 1:100 dilution of the first PCR was used in a second 20 µl PCR using NMo5079/5080 and cycling conditions: 0:30 @ 98°, 30 X [0:10 @ 98°, 0:30 @ 62°, 1:00 @ 72°]; 1 µl of the second PCR was examined by gel electrophoresis. Unique products were directly purified using QIAquick column purification. When multiple products were present, the entire PCR reaction was loaded on an agarose gel, and single bands were excised and purified. Products were sequenced using NMo5080.

Analysis of miniMos and RMCE inserts

The structure of all miniMos and RMCE insertions was confirmed by restriction digestion of long-range PCR products obtained from amplifying across the entire insertion site using LongAmp polymerase (New England Biolabs) under the manufacturer’s suggested conditions. NMo6563/6564 were used to amplify jsTi1453 inserts, NMo6613/6614 for jsTi1490 inserts, NMo6619/6675 for jsTi1492 inserts, and NMo6617/6618 for jsTi1493 insert. In some cases, portions of the PCR product were also sequenced.

Data availability

The authors state that all data necessary for confirming the conclusions presented in the article are represented fully within the article. All data generated is present in figures, supplemental figures, tables and supplemental tables. Supplemental materials consisting of supplemental methods, supplemental statistics, and supplemental figure legends files, 14 supplemental figures, eight supplemental tables, and a detailed RMCE protocol have been deposited at figshare. The RMCE protocol will be updated periodically and available at https://sites.wustl.edu/nonetlab/rmce-integration/. Critical worm strains and plasmids will be made available at the CGC and Addgene, respectively. At the time of publication, the COVID-19 pandemic is impairing distribution of materials to the CGC and Addgene. All other reagents are available upon request from Michael Nonet. Supplemental material available at figshare: https://doi.org/10.25386/genetics.12378473.

Results

Flp expression prevents extrachromosomal array formation

I assessed the behavior of plasmid DNA containing an FRT site in injections into C. elegans strains expressing Flp recombinase in the germline. I generated a dpy-7p::FRT::GFP; mex-5p::FLP::sl2::mNG strain (Figure S1A) using previously described FRT and Flp reagents (Muñoz-Jiménez et al. 2017; Macías-León and Askjaer 2018), performed germline injections of a plasmid containing a sqt-1 marker and an FRT site, and screened the progeny for Rol animals (Figure S1B). My working hypothesis was that the DNA injected into the germline would concatenate into arrays, but that Flp would then act to disassemble the arrays. Additionally, I hypothesized that some injected plasmid DNA monomers or concatemers would briefly integrate into the dpy-7p::FRT::GFP locus, but would quickly be re-excised by the further action of Flp. At equilibrium, I expected the injected DNA to be primarily monomers, and, hence, be unable to stably transmit as extrachromosomal arrays. Surprisingly, I was able to obtain F1 Rol progeny injecting low concentrations of plasmid (21 P0 injected, 6.3 F1 Rol/P0). These F1 rollers were cloned and the F2 progeny screened for Rol animals. Among the progeny of 133 F1 Rol animals, no F2 Rol progeny were identified. In parallel, I created Rol extrachromosomal arrays containing FRT sites (ExRol-FRT) in a dpy-7p::FRT::GFP strain, then crossed in the mex-5p::FLP::sl2::mNG transgene to test if FRT-containing sequences derived from arrays could be integrated (Figure S1C). Among 12 Rol animals expressing Flp, none reliably transmitted the array. By contrast, all 12 Rol animals lacking Flp reliably transmitted the Rol array, yielding 30–60% Rol progeny. These experiments suggest that arrays containing FRT sites cannot be reliably transmitted through a hermaphrodite germline that expresses Flp. Furthermore, they suggest that plasmids containing a single FRT site cannot efficiently integrate into chromosomal FRT landing sites in the presence of Flp.

Dual-component RMCE integration

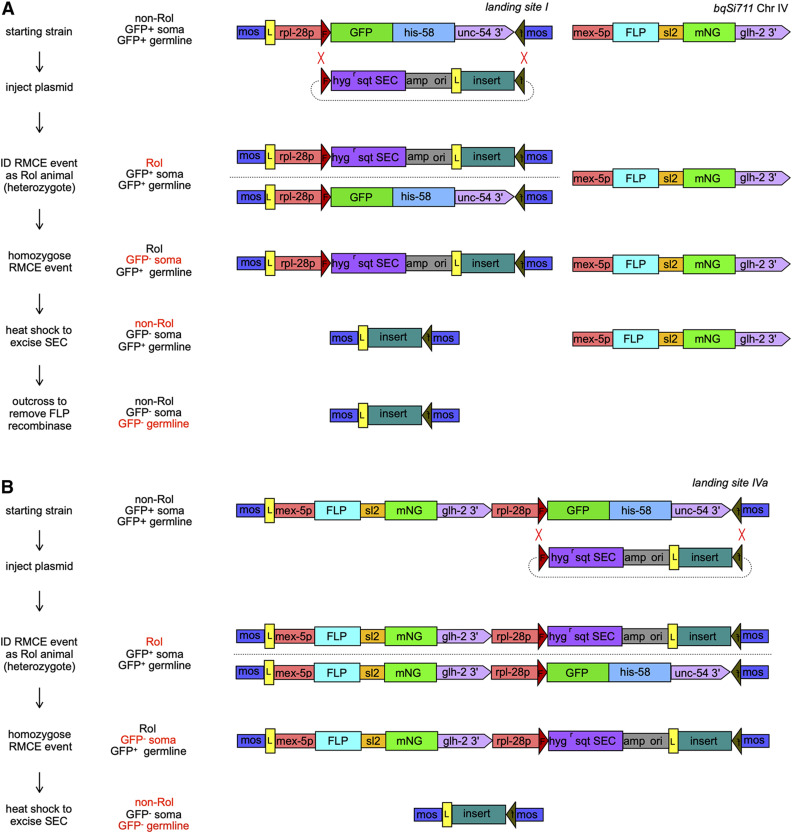

The most efficient RMCE integration methods take advantage of a pair distinct noncross reactive FRT sites present in both a genomic landing site and a targeting plasmid, and allow for integration that is stable even in the continued presence of Flp. I developed vectors and integration sites with dual FRT sites for C. elegans. I engineered a landing site consisting of the ubiquitous rpl-28 promoter driving a nuclear targeted GFP-his-58 fusion flanked by 5′ FRT and 3′ FRT3 sites in a miniMos vector (Figure 1A). I integrated this miniMos plasmid and isolated jsTi1453 (Figures S2 and S3A), a well-behaved insertion of this landing cassette in an intergenic region on chromosome I, referred to herein as landing site I. I crossed in a mex-5p::FLP::sl2::mNG transgene creating a strain containing both an FRT FRT3 landing site and expressing Flp in the germline. landing site I appears stable in the face of persistent germline Flp expression over many generations of passaging as evidenced by continued expression of GFP-HIS-58.

Figure 1.

RMCE integration methods. Shown are diagrams illustrating the methodology used to create single copy insertions using RMCE. (A) The two-component method using a landing site and an unlinked source of Flp. (B) The single component method using a single landing site that expresses germline Flp. On the left, the distinct steps of the approaches are listed. In the middle, the phenotypes of the relevant animals isolated at each step of the protocols are listed. The phenotype that is changing at each step is highlighted in red. On the right in (A) diagrams of the structure of landing site I (jsTi1453) and the Chr IV FLP expressing transgenic insertion bqSi711, and (B) a diagram of landing site IVa (jsTi493) containing a FLP expression cassette. In each diagram, a representative RMCE plasmid with an insert is also depicted. The two red Xs show the positions of recombination events that yield cassette replacement. Although this diagram depicts both events happening simultaneously for simplicity, it is likely they actually occur in series (see Figure S14). Abbreviations, mos: miniMos arm, L: loxP site, F:FRT site, backward “f”: FRT3 site in opposite orientation of the FRT site, hygr sqt SEC: a cassette containing a promoterless hygromycin resistance gene, the sqt-1(e1350) gene, and cre recombinase under the control of the hsp-16.1 promoter, mNG: mNeonGreen fluorescent protein gene, sl2: gpd2/3 trans-splicing sequences, amp: β-lactamase gene, ori: E. coli plasmid replication origin.

I also constructed the integration vector pLF3FShC, which contains an FRT site followed by a modified self-excising cassette (SEC) containing a promoter-less hygR gene, the sqt-1(e1350) gene, and an hsp-16 promoter driving Cre recombinase (Dickinson et al. 2015), an ampR plasmid vector backbone, and a single loxP site followed by a multiple cloning site (MCS) and an FRT3 site (Figure 1A). The plasmid was designed such that insertion into the landing site by recombination at the FRT sites would disrupt GFP-HIS-58 expression and permit selection with hygromycin B. Furthermore, this arrangement permits excision of the loxP flanked SEC by heat shock, leaving only the plasmid insert flanked by a 5′ loxP and a 3′ FRT3 site and the miniMos arms(Figure 1A). Thus, the design permits screening or selection for insertion into the locus, a phenotypic assay for homozygosity at the locus, and a method to excise the screening/selection cassette to minimize the size of the inserted sequences.

Stable RMCE integrations were obtained using the approach outlined in Figure 2. I injected four different insert containing constructs in separate experiments into landing site I; mex-5p::FLP::sl2::mNG animals. The injections all yielded F1 Rol animals, but surprisingly the F1 Rol animals rarely segregated Rol animals in a Mendelian ratio. However, ∼5–10% of the F1 Rol animals produced “rare” Rol progeny (typically one to four per transmitting F1). The vast majority (>90%) of these F2 Rol progeny were integration events based on several criteria. First, they segregated GFP-HIS-58(+) nonRol, GFP-HIS-58(+) Rol, and GFP-HIS-58(−) Rol progeny at approximately a 1:2:1 ratio. Second, PCR amplification from the homozygous Rol animals yielded products consistent with an insertion. Finally, after heat shock excision of the SEC, PCR amplification across the entire insertion site yielded products of a size consistent with the insert contained in the injected plasmid DNA (Figure S3, B and C). These insertions are stable both in the presence of germline Flp and after outcross of the Flp expressing transgene.

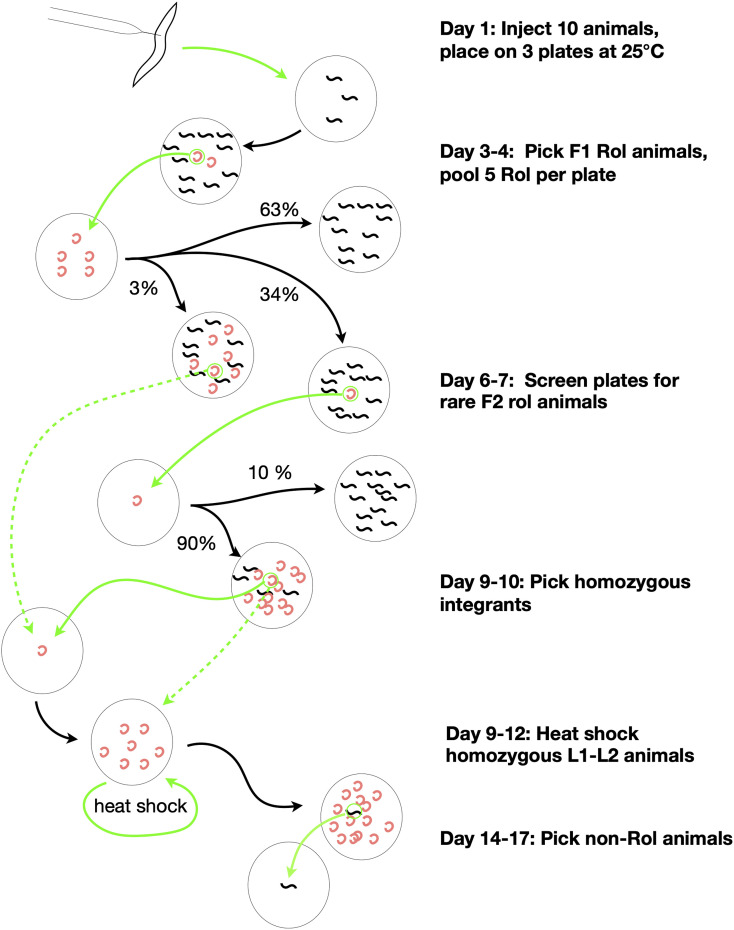

Figure 2.

Overview of RMCE procedure. A flow diagram illustrating the timeline of the RMCE procedure. The method consists of seven reliable steps. First, DNA of interest is inserted into pLF3FShC, a vector with a polylinker, which is compatible with SapI Golden Gate cloning (not shown). Second, miniprep DNA is injected at modest concentration (50 ng/µl) into the germline of animals carrying a landing site and injected animals are incubated at 25°. Third, on day 3, F1 Rol progeny are isolated and pooled ∼5 to a plate. Fourth, on day 6, “rare” F2 Rol are isolated as likely integrants. Fifth, on day 9, somatic non-GFP F3 homozygous animals are isolated. The loss of somatic GFP confirms the integration and provides a simple assay to identify homozygotes. Sixth, ∼20–30 L1–L2 homozygotes are heat shocked to induce Cre excision of the SEC. Finally, on day 14 or 15 non-Rol homozygous integrants are cloned. The large gray circles represent agar plates, small black squiggles represent wild type non-Rol worms and the red crescents represent Rol worms. Green arrows represent actions performed by the investigator and black lines represent one generation of growth of worms. Dashed arrows represent alternative time-saving steps that can occasionally be performed. The longer dashed arrow represents picking homozygous integrants on rare plates with early integration events. The smaller dashed arrow represents picking a large number of homozygous integrant individuals rather than allowing a single homozygous integrant to expand by selfing. The percentages represent the approximate fraction of plates which yield the distinct progeny distributions depicted.

Single component RMCE integration

Motivated by a desire to simplify the system, I inserted a mex-5p::FLP::SL2::mNG cassette in between the loxP site and rpl-28 promoter in the original miniMos landing site vector, then generated and characterized jsTi1490 IV (landing site IVb), jsTi1492 II (landing site II), and jsTi1493 IV (landing site IVa) insertions (Figure 1B, Figure S2, and Figure S3A). These three transgenes all express GFP-HIS-58 in all nuclei and mNG (and presumably Flp) in the developing germline, mature germline, and in the early embryo stages of progeny (Figure S4). I injected a variety of different pLF3FShC insert plasmids (as described below) into the three landing site strains and quantified the efficiency of integration (Table 1, Table S1 and Materials and Methods for details). I also performed additional injections using the two-component strain.

Table 1. Summary of quantified injections.

| INJ # | Injecteda | F0 Plates | F1 Rolsb | F1 Plates | F1 plates with F2 Rolsc | F2 Rols | F1 plates with integrants |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 126 | 7 | 4 | 30 | 3 | 3 (1–2) | 5 | 2 |

| 127 | 10 | 4 | 92 | 12 | 6 (2–10+) | 36 | 5 |

| 131 | 10 | 3 | 91 | 16 | 11 (1–10+) | >39 | 10 |

| 136 | 8 | 2 | 52 | 9 | 3 (1–10+) | >17 | 3 |

| 141 | 12 | 5 | 34 | 7 | 1 (4) | 4 | 1 |

| 142 | 12 | 4 | 54 | 9 | 1 (1) | 1 | 1 |

| 143 | 9 | 3 | 43 | 8 | 2 (2–10+) | >20 | 2 |

| 144 | 3 | 1 | 10 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| 145 | 10 | 4 | 107 | 18 | 7 (1–10+) | >100 | 5 |

| 146 | 8 | 3 | 38 | 8 | 3 (1–3) | 7 | 3 |

| 147 | 9 | 3 | 88 | 15 | 5 (1–4) | 13 | 4 |

| 148 | 7 | 3 | 67 | 13 | 7 (1–40+) | >50 | 6 |

| 149 | 10 | 3 | 43 | 9 | 7 (4–30+) | >50 | 7 |

| 150 | 6 | 3 | 42 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| 151 | 12 | 4 | 54 | 10 | 4 (1–20+) | >50 | 2 |

| 152 | 7 | 3 | 25 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 153 | 10 | 3 | 72 | 13 | 6 (1–8) | 19 | 5 |

| 154 | 3 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 156 | 8 | 3 | 18 | 4 | 1 (3) | 3 | 1 |

| 156B | 7 | 2 | 23 | 5 | 3 (2–6+) | >15 | 3 |

| 157 | 12 | 4 | 104 | 18 | 6 (1–6+) | >16 | 6 |

| 158 | 13 | 4 | 24 | 5 | 4 (1–2) | 6 | 3 |

| 159 | 12 | 4 | 37 | 8 | 4 (1–20+) | >30 | 4 |

| 160 | 9 | 3 | 46 | 11 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 161 | 9 | 3 | 24 | 6 | 1 (5) | 5 | 1 |

| 162 | 12 | 4 | 55 | 12 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 163 | 10 | 4 | 143 | 24 | 7 (1–10+) | >25 | 7 |

| 166 | 10 | 4 | 21 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 169 | 8 | 2 | 29 | 5 | 5 (1–30+) | >32 | 4 |

| 170 | 9 | 3 | 55 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 2 |

| SUMMARY | 272 | 96 | 1525 | 281 | 105 (1–40+) | ≫548 | 92 |

See Table S1 for an extended version of this table that lists total animals injected, strains injected, plasmids injected, concentration of DNA and other extended analysis.

Number of well injected P0 animals. See methods for definition.

Rol animals were picked at all ages. Some animals picked at L2/L3 stage did not Rol as adults. Both adult Rol and non-Rol transmitted Rol F2 animals.

Number of independent plates of pooled F1 Rols that yielded F2 Rol animals. In parentheses is the range of Rol animals found F1 plates with Rol animals.

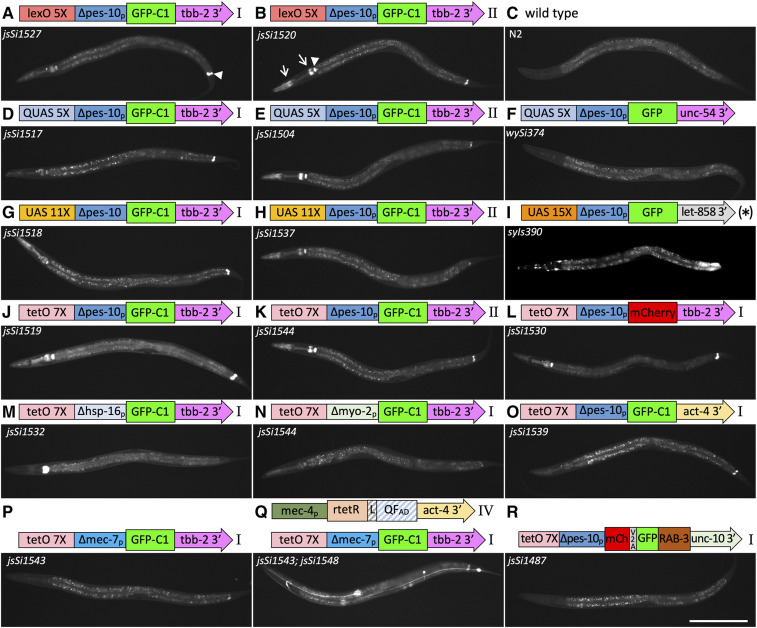

Insertion sites are all competent for expression

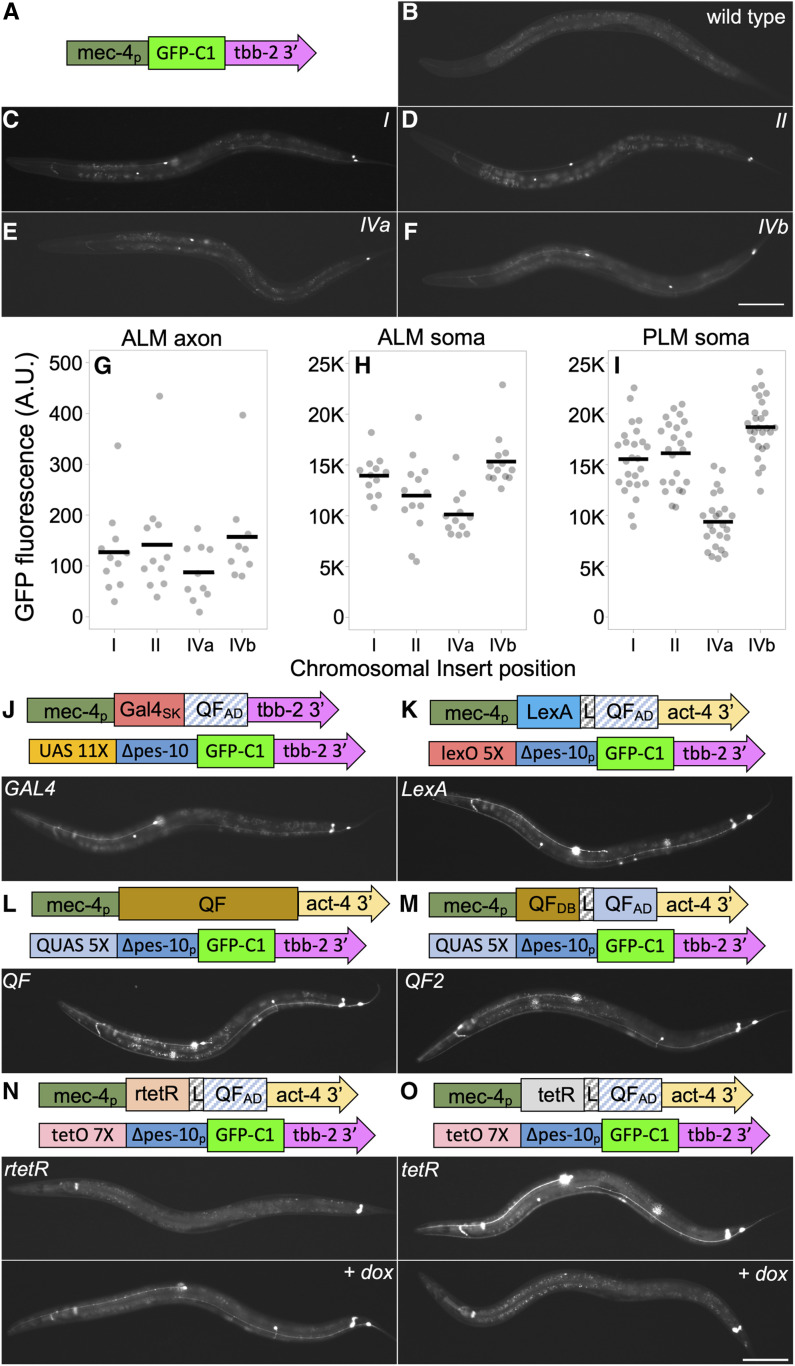

To assess the competency of the insertion sites for expression, I inserted the identical mec-4p GFP-C1 reporter at all four landing sites. GFP was expressed specifically in the six touch receptor neurons (TRNs) at roughly comparable intensity from all four landing sites, and was detectable in cell bodies on a high-magnification fluorescent dissecting scope (Figure 3, A–I). This observation supports the conclusion that the four sites are all generally permissive for expression, since the initial isolation of the landing sites additionally demonstrated the sites are permissive for the expression of (1) SQT-1 in the ectoderm, (2) GFP in all nuclei, and mNG in the germline (except in the case of landing site I).

Figure 3.

Expression levels from direct and bipartite reporter systems. (A–F) Expression from mec-4 promoter GFP-C1 transgenes integrated using RMCE. (A) Schematic of the integrated sequences. (B–F) Widefield epi-fluorescence images acquired with a 10× air lens of a representative L4 wild type hermaphrodite and L4 hermaphrodites harboring mec-4p::GFP-C1 integration events at four distinct RMCE landing sites. Bar, 100 µm. (G–I) Quantification of GFP intensity in (G) the ALM axon, (H) the ALM soma and (I) the PLM soma from widefield images acquired with a 40× air lens. Individual measurements (circles) and the mean (line) are shown. Arbitrary units (A.U.) are defined identically in (G–I). (J–O) Expression of GFP from bipartite reporter systems using the mec-4 promoter to express drivers. Schematics of the driver and reporter constructs for each strain are shown. Below the schematics, widefield epi-fluorescence images acquired with a 10× air lens of representative L4 hermaphrodites homozygous for a mec-4 promoter driver integrated at landing site IVa and homozygous for a GFP-C1 reporter line integrated at landing site I. The schematics of the constructs are not to scale. All images are taken with identical exposure and light settings including (B–F). See Figures S5 and S6 for more detailed schematics. 1 ng/ml of doxycycline was added to plates of animals labeled + dox (N and O) 2 days before imaging. Statistics (n, mean, SE, and P-values of comparisons) in Supplemental Materials. Bar, 100 µm. Complete genotypes: (B) N2 wild type, (C) jsTi1453 jsSi1514 [mec-4p GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I, (D) jsTi1492 jsSi1535 [mec-4p GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II, (E) jsTi1493 jsSi1502 [mec-4p GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] IV, (F) jsTi1490 jsSi1529 [mec-4p GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′ ] IV, (J) jsTi1453 jsSi1518 [UAS 11X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1515 [mec-4p GAL4-QFADtbb-2 3′] IV, (K) jsTi1453 jsSi1527 [lexO 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1549 [mec-4p lexA-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (L) jsTi1453 jsSi1517 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1551 [mec-4p QF act-4 3′] IV, (M) jsTi1453 jsSi1517 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1554 [mec-4p QF2 act-4 3′] IV, (N) jsTi1453 jsSi1519 [tetO 7X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1548 [mec-4p rtetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (O) jsTi1453 jsSi1519 [tetO 7X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1560 [mec-4p tetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV.

Four bipartite expression systems all function in single copy

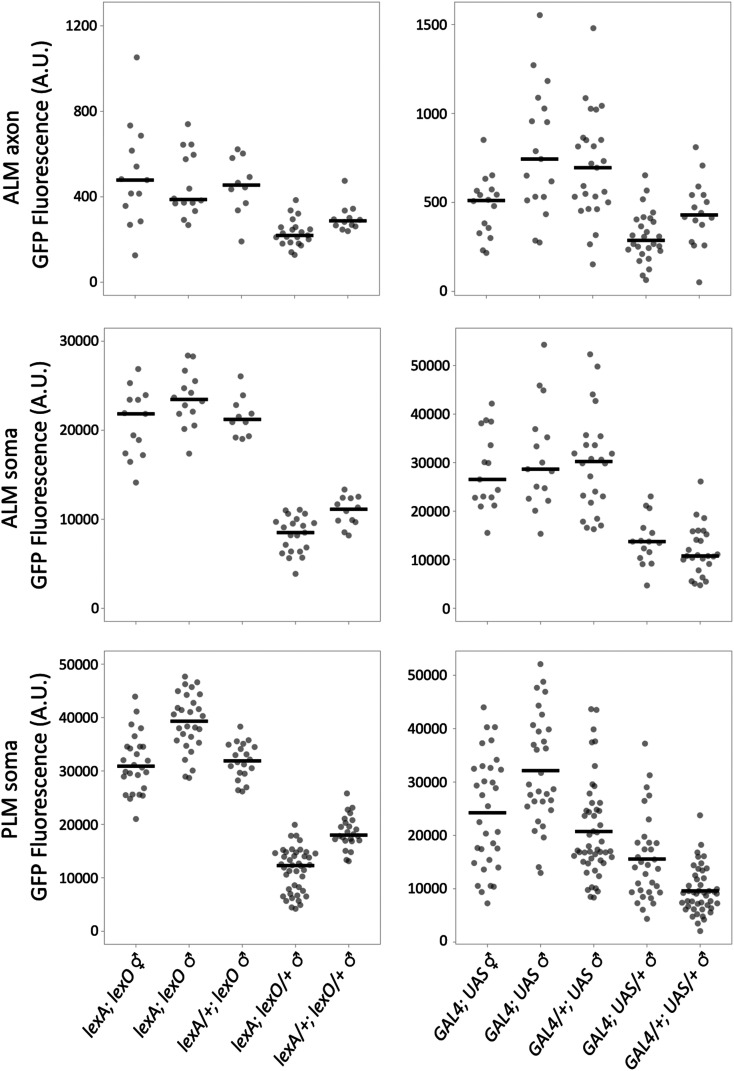

The simplicity of the RMCE integration system prompted me to test the relative efficiency of numerous bipartite reporter systems integrated in single copy. I created GFP-C1 reporter constructs driven by a 7X tetO ∆pes-10 promoter (Mao et al. 2019), a 11X UAS ∆pes-10 promoter, a 5X QUAS ∆pes-10 promoter, and a 5X lexO ∆pes-10 promoter (Figure 3, Figure S5 and Supplemental Methods), and inserted all four at both landing site I and II. mec-4 promoter constructs expressing drivers very similar or identical to Gal4SK-VP64 (Wang et al. 2017), QF (Wei et al. 2012), QF2 (Riabinina et al. 2015), and rtetR-L-QFAD (tet ON) (Mao et al. 2019) were constructed. In addition, constructs expressing novel tetR-L-QFAD (tet OFF), LexA-L-QF, and Gal4SK-QFAD C. elegans-codon-optimized drivers were created (Figure 3 and Figure S6, and Supplemental Methods). All constructs were integrated at landing site IVa and some were also integrated at landing site IVb. I then crossed the driver lines to the reporter lines to determine the relative efficacy of the various systems. My results indicate that tetR/tetO (tet OFF), rtetR/tetO (tet ON), LexA/lexO, QF/QUAS and QF2/QUAS were all expressed relatively robustly (∼4–10 times higher GFP levels than a direct promoter GFP-C1 transgene, Figure 3, J–O and Figure 4). The relative level of expression was cell-type-dependent with some drivers being brighter in ALM than PLM, and others vice versa (Figure 3 and Figure 4). All five driver/reporter lines were brighter than Gal4SK-QFAD/UAS, which may be nonoptimal as it does not contain a flexible linker between the DNA binding domain and activation domain. GFP was undetectable in TRNs in absence of doxycycline in the tet ON lines (Figure 3N), and GFP signals were repressed by the addition of doxycycline in the tet OFF lines (Figure 3O and Figure S7). rtetR/tetO (tet ON) was also demonstrated to function when driven under the weaker phat-5 promoter (Figure S8). Thus, all four reporter systems are functional in C. elegans in single copy.

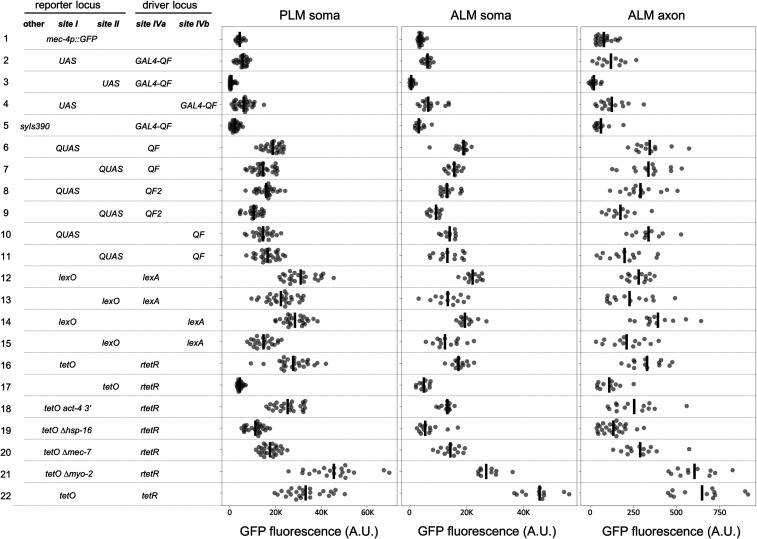

Figure 4.

Quantification of bipartite reporter expression. Quantification of GFP intensity in PLM soma, ALM soma, and ALM axon of various combinations of reporter and driver RMCE integration events. Quantification was performed using widefield images acquired with a 40× air lens. Individual measurements (circles) and the mean (line) are shown. Arbitrary units (A.U.) are defined identically for all measurements. The data for each strain analyzed is presented in a separate row of the figure. The position and type of reporter and driver locus in each strain is shown on the left. In bold at the top of each column is the RMCE integration site (site I = jsTi1453, site II = jsTi1492, site IVa = jsTi1493, site IVb = jsTi1490), and in the column is an abbreviated description of the specific integrated reporter and driver present in the strain. UAS, QUAS, lexO, and tetO refer to reporters using these binding sites in combination with ∆pes-10 GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′. The tetO derivatives with the alternate act-4 3′ UTR, or alternate basal promoters are labeled. lexA, tetR, and rtetR driver names are shorted and lack the “-L-QFAD” designations. Statistics (n, mean, SE, and P-values of comparisons) in Supplemental Materials. Complete genotypes: (1) jsTi1453 jsSi1514 [mec-4p GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I, (2) jsTi1453 jsSi1518 [UAS 11X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1515 [mec-4p GAL4-QFADtbb-2 3′] IV. (3) jsTi1492 jsSi1552 [UAS 11X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II; jsTi1493 jsSi1515 [mec-4p GAL4-QFADtbb-2 3′] IV. (4) jsTi1453 jsSi1518 [UAS 11X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1490 jsIs1528 [mec-4p GAL4-QFADtbb-2 3′] IV. (5) jsTi1493 jsSi1515 [mec-4p GAL4-QFADtbb-2 3′] IV; syIs390 [UAS 15X Δpes-10 GFP let-858 3′; ttx-3p RFP]. (6) jsTi1453 jsSi1517 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1551 [mec-4p QF act-4 3′] IV. (7) jsTi1492 jsSi1504 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II; jsTi1493 jsSi1551 [mec-4p QF act-4 3′] IV. (8) jsTi1453 jsSi1517 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1554 [mec-4p QF2 act-4 3′] IV. (9) jsTi1492 jsSi1504 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II; jsTi1493 jsSi1554 [mec-4p QF2 act-4 3′] IV. (10) jsTi1453 jsSi1517 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1490 jsSi1553 [mec-4p QF act-4 3′] IV. (11) jsTi1492 jsSi1504 [QUAS 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II; jsTi1490 jsSi1553 [mec-4p QF act-4 3′] IV. (12) jsTi1453 jsSi1527 [lexO 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1549 [mec-4p lexA-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (13) jsTi1492 jsSi1520 [lexO 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II; jsTi1493 jsSi1549 [mec-4p lexA-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (14) jsTi1453 jsSi1527 [lexO 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1490 jsSi1555 [mec-4p lexA-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (15) jsTi1492 jsSi1520 [lexO 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II; jsTi1490 jsSi1555 [mec-4p lexA-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (16) jsTi1453 jsSi1519 [tetO 7X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1548 [mec-4p rtetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (17) jsTi1492 jsSi1537 [tetO 7X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] II; jsTi1493 jsSi1548 [mec-4p rtetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (18) jsTi1453 jsSi1539 [tetO 7X GFP-C1 act-4 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1548 [mec-4p rtetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (19) jsTi1453 jsSi1532 [tetO 7X ∆hsp-16.1 GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1548 [mec-4p rtetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (20) jsTi1453 jsSi1543 [tetO 7X ∆mec-7 GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1548 [mec-4p rtetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (21) jsTi1453 jsSi1544 [tetO 7X ∆myo-2 GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1548 [mec-4p rtetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV, (22) jsTi1453 jsSi1519 [tetO 7X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′] I; jsTi1493 jsSi1560 [mec-4p tetR-L-QFADact-4 3′] IV.

Distinct landing sites have varied competency for expression

To assess if the position of driver and reporter insertions has significant influence on expression, I created most of the distinct reporter/driver insertion combinations in cases where I had created either reporter or driver lines at two distinct sites in the genome. I observed modest ∼twofold differences in expression among most distinct combinations of drivers and reporters (Figure 4). This influence was largely consistent across different bipartite systems, with reporters integrated at landing site I expressing more robustly than those integrated at landing site II, and drivers at landing site IVa being slightly stronger than those at landing site IVb. However, this data should be taken in context that only a single promoter was tested, and the context that landing sites were identified as miniMos insertions that permitted expression of sqt-1 and rpl-28.

Reporter function limits expression of bipartite systems

The efficiency of bipartite expression systems is determined by both the potency of the driver and the reporter. A system that is limited by the activity of the driver is unlikely to greatly amplify weak promoters. By contrast, a system that is limited by the reporter will likely result in similar expression levels despite driver promoters having dramatically different strengths. In this scenario, the potential of strong promoters to provide robust signals may be compromised. To assess what limits the bipartite systems, I examined expression levels in animals with various combinations of D and R dosage: D/+; R/+, D/D; R/+, D/+; R/R and R/R; D/D. I tested one weaker and one stronger reporter system; Gal4SK-QFAD/UAS and the LexA-L-QFAD/lexO. In both cases, reporter copy number is limiting as expression levels correlate with the copy number of the reporter and not with copy number of the driver (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Effects of reporter and driver dosage on GFP expression. Quantification of TRN GFP expression level from widefield images acquired with a 40× air lens of strains carrying various dosage of reporter and driver insertions. Individual measurements (circles) and the mean (line) are shown. To obtain various reporter (R) and driver (D) combinations the following crosses were performed: R; D ♂ were obtained from crosses of R; D ♂ crossed to R; D ♀. R/+; D/+ ♂ were obtained from him-8 ♂ crossed to R; D ♀. R/R; D/+ ♂ animals were obtained from R; him-8 ♂ males crossed to R; D ♀. To obtain R/+; D/D ♂ animals, him-8 ♂ were crossed to jsTi1493 ♀, progeny jsTi1493/him-8 ♂ were crossed to D ♀, somatic GFP[+] progeny D/jsTi1493 ♂ were crossed to R;D ♀, and somatic GFP[-] progeny ♂ were imaged. Arbitrary units (A.U.) definition for the lexA strains is ∼4× those of the GAL4 strains. In building double transgenes for the QF and tet bipartite systems, I had difficulty distinguishing between R/R; D/+ and R/R; D/D animals, suggesting that activity of all four systems is limited by the reporter. Complete genotypes: lexA, jsSi1549 [mec-4p lexA-L-QF act-4 3′]; lexO, jsSi1527 [lexO 5X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′]; GAL4, jsSi1515 [mec-4p GAL4-QF tbb-2 3′]; UAS, jsSi1518 [UAS 11X GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′].

Promoter element contributions to reporter background

The bipartite systems express well, but all the reporter lines exhibit some background GFP expression in the absence of a driver. Interestingly, the GFP signal in all four reporters was similar in scope (Figure 6, rows 1–4) suggesting that common element(s) in the reporters were responsible for the background. To define the cause(s) of the background, I swapped out GFP for mCherry, the tbb-2 3′ UTR for the act-4 3′ UTR, and the ∆pes-10 basal promoter for the ∆hsp-16-1, ∆mec-7 and ∆myo-2 basal promoters, all with a tetO 7X regulatory region (Figure 6 and Figure S5) and integrated these reporter variants. Analysis of the strains suggests that multiple different elements are contributing to the background including elements I did not manipulate (the loxP site, the FRT3 site, and the Mos1 transposon ends). Consistent with the tbb-2 3′ UTR contributing to the background in the pharynx, reporters with an unc-10 3′ UTR (jsSi1487), and act-4 3′UTR (jsSi1539) had much lower pharyngeal background (Figure 6J vs. Figure 6, O and R and Figure S9J vs. FigureS9, O and R). However, the level of pharyngeal background was also affected by changing the basal promoter. The ∆hsp-16.1 basal promoter increased pharyngeal background (Figure 6J vs. Figure 6M), while the ∆myo-2 and ∆mec-7 basal promoters reduced background (Figure 6J vs. Figure 6, N and P). The background in the rectal gland cells was present in all reporters, but at substantially different levels, suggesting that other elements contribute in part to that background (Figure S10). Importantly, none of these background signals were influenced by the presence of drivers (Figure 3, Figure 6, P and Q, Figure S9, P and Q, and Figure S10, P and Q). In addition, altering the basal promoter changed the overall expression of the reporters (Figure 4, row 16, 19–21). The reporter with the highest signal-to-noise ratio, jsSi1543 [7X tetO ∆mec-7 GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′], had background levels that are still slightly higher than that of wySi374 [QUAS 5X GFP unc-54 3′] (Wei et al. 2012), but substantially lower than syIs390 [UAS 15X GFP let-858 3′ multi-copy] (Wang et al. 2017). Further experiments to define the optimal enhancer spacing, basal promoter and 3′ UTR sequences should permit the development of promoters that induce strongly with little or no signal in the absence of a driver.

Figure 6.

Background observed in bipartite reporter constructs. Widefield epi-fluorescence images of L4 animals taken using a 10× air lens with accompanying schematic diagrams of reporter constructs. (A–K) Animals homozygous for RMCE insertions of four distinct reporter constructs at landing site I and II as well as a wild-type control, a QUAS integrant isolated using MosSCI (Wei et al. 2012), and a multi-copy (*) UAS 15× integrated array (Wang et al. 2017). Background signal in the absence of a driver is observed in the rectal gland cells rect_VL, rect _VR and rect_D in the tail (e.g., arrowhead in A), the pharyngeal/intestinal valve cells (e.g., arrowhead in B), and portions of the pharynx (e.g., arrows in B). Signal in the intestine is background autofluorescence (except for the posterior intestinal signal in (I). (L–R) Background levels in RMCE insertions at landing site I in cases where the fluorescent protein, the 3′ UTR sequences or the basal promoter of the tet0 7X ∆pes-10 GFP-C1 tbb-2 3′ reporter construct have been replaced. (P and Q) Comparison of tetO reporter background levels in presence and absence of a mec-4 driver showing that background in not amplified by the presence of doxycycline. Diagrams of constructs are not to scale. See Figures S5 and S6 for detailed diagrams. All images are taken under identical conditions (500 msec exposure). Detailed head and tail images are presented in Figures S9 and S10. Bar, 200 µm.

Attempts to obtain multi-insert integration

While single-copy integration is a powerful tool, in some situations a multi-copy integrant that permits higher expression may be more beneficial. One hypothetical mechanism to create multi-copy insertions from distinct input plasmids is to create an integration vector with a region within the insert sequences with homology to other plasmids. I re-engineered the integration vector moving the loxP site from adjacent to the FRT and FRT3 sites to the other side of the ∼3 kb vector backbone (Figure S11A). In this configuration recombination that occurs between vector backbones during initial array formation could create an insertion containing multiple plasmids depending on the ratio of the plasmids and the sites of recombination (Figure S11, B and C). I co-injected plasmids carrying the mec-4 promoter driving GAL4SK-QFAD and 11X UAS GFP-C1 with the modified integration vector at a ratio of 5:5:1 and derived four independent insertion events. However, none expressed GFP in TNRs and molecular characterization of the insertions indicated all are insertions of the integration vector alone (Figure S3, G and E).

Discussion

I describe a new integration method for creating single copy insertions of large DNA fragments in C. elegans at efficiencies of approximately one integration event per three injected P0 animals (Table 1). The method is efficient enough that it is feasible under certain conditions to co-inject multiple plasmids and isolate insertions of each plasmid from a single injection session (e.g., Table S1 injection 149). Since many aspects of the protocol have not been optimized, further improvements in the efficiency of the system are likely possible.

Bipartite reporter systems

I opted to examine the potential of bipartite reporter systems in C. elegans to test the efficiency of RMCE. I demonstrated that four different reporter systems can all induce expression of a reporter to high levels in specific cells in single copy. Specifically, I demonstrated for the first time that the LexA system is active in C. elegans. I also demonstrated that the previously developed Gal4 and tet ON systems also function in single copy and developed a novel tet OFF driver that functions in the absence of doxycycline, and turns off upon application of doxycycline. The expression levels obtained using these systems suggest that all are strong enough to utilize in single copy. This work provides a baseline level of confidence that a robust set of bipartite tools can be developed by the C. elegans community.

Each of the four traditional bipartite reporter systems has both benefits and limitations. The Gal4 system has been extensively engineered in Drosophila (e.g., split Gal4, estrogen responsive Gal4ER, and Gal80 mediated repression) to refine spatial control of expression patterns (Caygill and Brand 2016), which should simplify development of similar refinements for worms. Though the Gal4 system is the weakest of the four systems, multiple integrated UAS reporter lines have been developed in worms (Wang et al. 2017), making it an attractive system to try. The QF system offers temporal control in trans using QS, a quinic acid responsive repressor that acts by binding QFAD (Potter et al. 2010; Wei et al. 2012), and in cis using a QF-GR glucocorticoid receptor ligand-binding domain fusion that provides ligand-gated control of transcriptional activation (Monsalve et al. 2019). Similarly, the tet ON and tet OFF drivers provide temporal control both in the on and off directions (Schönig et al. 2010). In addition, Mao et al. (2019) have shown that the tet ON rtetR-QF hybrid driver can be controlled by QS, allowing for intersectional control of gene expression in that system as well. Although not tested, tetR-L-QF, Gal4SK-QF, and LexA-L-QF drivers developed herein should in theory also be QS responsive. The major limitation of the QF and tet responsive systems is that fewer published tools are available to explore their utility. Lastly, the less extensively developed LexA system still has found significant utility in the Drosophila community (Riabinina and Potter 2016). Hopefully, C. elegans laboratories developing bipartite systems will initially converge on a subset of these systems.

In addition to developing drivers, I compared the background of the four different reporters and manipulated components of the reporters to alter the background. Importantly, most background is a consequence of the basal promoter and 3′ UTR rather than native transcription factor interactions with the UAS, QUAS, tetO, and lexO DNA binding enhancer sequences. Relatively straightforward experiments testing different basal promoters and 3′ UTRs, driver binding site spacing and testing distinct genome landing sites should further increase the specificity and control over expression levels. Furthermore, by changing the number of driver binding sites in reporter constructs, it should be feasible to change the strength of the reporters at least for the Gal4/UAS system (Wang et al. 2017). Using RMCE, these experiments are very feasible and should lay the foundation for a robust basic set of bipartite expression tools that can then be further refined, as has been done for Drosophila research (Caygill and Brand 2016; Riabinina and Potter 2016).

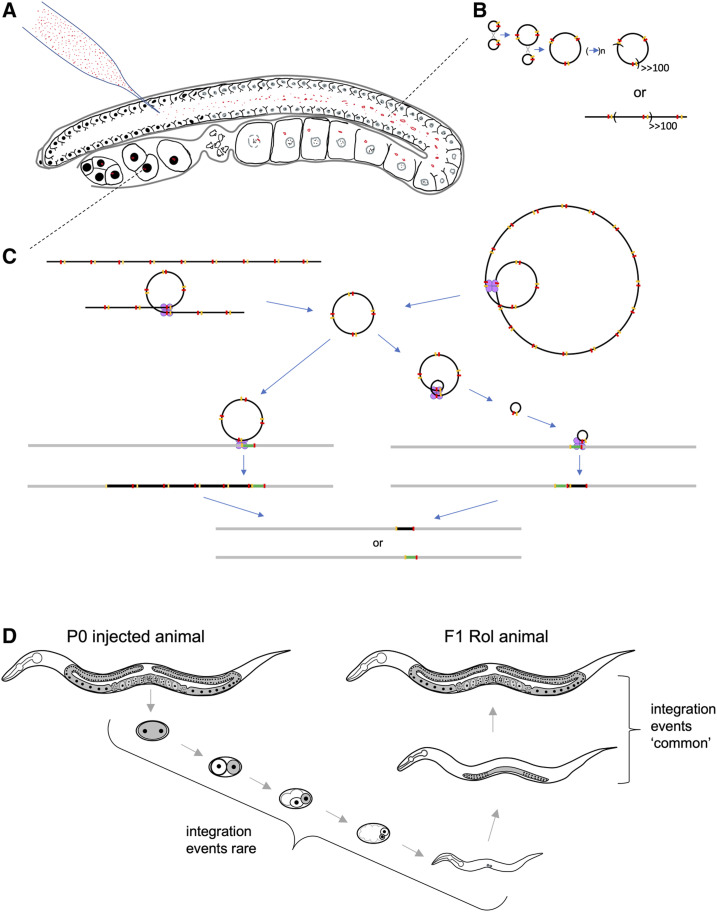

Mechanism of integration

Although I have developed a method for RCME in C. elegans, the exact mechanism of insertion remains unclear. On one hand, my data indicate that arrays containing FRT sites are unstable and not transmittable in animals expressing Flp in the germline. On the other hand, the biggest surprise in the development of this procedure was the finding that Flp recombination events rarely occur in the P0 germline, but instead commonly occur late in the development of the F1 germline.

My model for the mechanism of RMCE integration is based upon a previous observation I made injecting a mixture of an FITC-conjugated 80mer oligonucleotide and Cy3-conjugated pRF4 plasmid DNA into the C. elegans germline. The germline consists of an outer shell of syncytial nuclei surrounding a central cytoplasmic compartment called the rachis (Figure 7A). Injection of C. elegans adults typically delivers DNA in the rachis. In injected animals imaged 1 hr after injection of fluorescently labeled DNAs, I observed that oligonucleotides efficiently entered germline nuclei, but that Cy3-labeled plasmid DNA remained in the rachis (Figure S12). This suggests that injected DNA does not have the opportunity to become nuclear localized until after oocyte nuclear breakdown following fertilization (Greenstein 2005). Extrachromosomal arrays form largely by homologous recombination (Mello et al. 1991). One possibility is that array concatemer formation occurs in the cytoplasmic rachis (Figure 7B), and that large arrays then begin segregating as semistable chromosomes during cell divisions of the developing embryo. Since the Flp protein expressed in bqSi711 is tagged with a nuclear localization signal, I hypothesize that injected DNA in the rachis is protected from the action of Flp, which would break down arrays acting in opposition of array formation by homologous recombination (Figure 7C). Alternatively, the millions of injected plasmid molecules may simply overwhelm available Flp.

Figure 7.

Model of for the mechanism of Flp RMCE integration. (A) Shown is a C. elegans germline injected with plasmid DNA (red). Plasmid DNA is excluded from the syncytial germline nuclei, rather remaining in the rachis of the developing germline, and enters the nucleus only after nuclear envelop breakdown at the time of fertilization. Germline schematic based upon Huelgas-Morales et al. (2016). (B) In the germline, injected plasmid DNA molecules (black circles), each with an FRT and FRT3 site (yellow and red markings, respectively) form large concatemers primarily by Flp-independent homologous recombination. It is unclear if these large arrays resolve into linear “mini” chromosomes or remain circular. (C) After entering the nucleus, the large linear (left) or circular (right) arrays begin to be resolved into monomer and small multimer circular DNAs by the action of Flp (tetramers of purple circles) acting either at FRT or FRT3 sites. These smaller circular DNA molecules integrate by Flp-mediated integration either using FRT (shown on left) or FRT3 (shown on right) sites, and are then resolved by the further action of Flp to stable confirmations: either one containing only the insert plasmid and a single FRT and FRT3 site, or one consisting of the original landing site structure. This event is illustrated in more detail in Figure S14. Not shown, is the last step of excising the rpl-28 promoter, the SEC and the GFP-his-58 gene fusion by heat shock mediated Cre expression. (D) Shown is a schematic diagram of the development of an F1 Rol animal laid by a P0 injected animal. The germ plasm is shown in gray and select nuclei in black. The model proposes that most integration events occur late in the F1 germline development, and that rare events are occur in the early F1 germline. Schematic inspired by Xu et al. (2001).

Since most F1 Rol animals that segregate stable RMCE integrants produce only a few Rol progeny (typically one to four; Table S1) heterozygous for the insertion, these integration events must be occurring late in the germline. The C. elegans germplasm consists of only one cell in each gonad arm at the L1 larval stage, and these expand to a population of ∼50 cells in each gonad in L3, and ∼250 in adults (Figure 7D). If integration events occurred earlier than L3, one would predict the number of progeny carrying the integrant from an individual event would be higher than I regularly observed. Importantly, I did observe eight cases where homozygous integrants were isolated among the F2 progeny (Table S1). In these cases, the events must have occurred early since, statistically, a large fraction of the germplasm must have contained the integrant for substantial number of both sperm and oocytes to contain the insertion.

Mechanistically, it is likely that, in order for plasmid derived DNA to be stably segregated through multiple cell divisions and maintained in the developing germline, it must exist as a large array (rather than monomers), since the frequency of both array formation and transmission is known to correlate with DNA concentration (Mello et al. 1991). Thus, I propose that arrays that become nuclear in the young F1 embryo are replicated and segregated during cell divisions until Flp expression becomes robust in the late L4 stage (Figure S4). Later in germline development, the arrays are disassembled by the action of Flp into small multimer and monomer circular DNA molecules that serve as the templates for integration (Figure 7C). These insertions are then resolved by Flp, either stabilizing the insertion or restoring the original landing site configuration. The fact that addition of pBluescript carrier DNA to RMCE injection mixes does not reduce, and likely increases the frequency of insertions, is consistent with integration occurring via intermediate array formation and efficacious maintenance of the array in the developing germplasm during cell divisions in the embryo and early larval development (Figure S13A and Table S1). Also consistent with such a model is the fact that I often observe lethality from RMCE injections. The brood size of injected P0 progeny was often qualitative lower from plates where substantial numbers of Rol F1 were identified compared to plates where no F1 Rol progeny were identified. Furthermore, in experiments where a rab-3 promoter mCherry reporter plasmid was co-injected with pBluescript and the integration template plasmid, I observed dead eggs that were mCherry(+). While this lethality could simply be the result of toxicity of miniprep DNA, it would be expected that integration of linear templates (such as large arrays) with the chromosome by Flp would lead to the bisection of the chromosome, which would very likely be lethal. Further study of the mechanism of integration could help guide modifications of the protocol to increase integration frequency.

Single vs. dual component approach

I have created both single component and dual component strategies for RMCE insertion. The choice of which approach to use is worth discussing. Although the single component approach seems appealing, one of the insertions behaves unusually. Landing site II (jsTi1492) is inserted on the edge of a large 5-kb repeat region (Figure S2). Although I initially isolated several insertions (used within) at this locus, in some experiments I observed very high frequency of Rol animals and F2 animals that behaved as arrays. These animals expressed no GFP in the germline. I confirmed that germline expression from landing site II spontaneously silences while expression of rpl-28p driven GFP-his-58 in the soma is maintained, though at lower levels. Molecular analysis revealed no alteration in the structure of the insertion in germline GFP(−) animals (Figure S3A). I was still able to create additional insertions by prescreening young adults for GFP(+) germlines before injection, and during strain passage. In addition, several insertions in this locus exhibited conversion to non-Rol in absence of heat shock, and the molecular structure of these non-Rol animals was in two cases unexpected. Specifically, they appear to be deletions of the entire insertion and some surrounding DNA sequences, though I have not defined the deletions precisely (Figure S3I). However, the RMCE insertions I isolated that were of expected molecular structure appear stable. I also isolated two other miniMos landing site insertions, jsTi1509 X and jsTi1510 III (Figure S2), both of which were germline GFP(−) from the time of isolation as a non-Rol strain. It is unclear if these unusual behaviors (silencing and unusually molecular structure) are distinct phenomenon, or related, and it is unclear how common germline silencing will be among other insertions created at different chromosomal positions. Thus, while landing site IVa (jsTi1493) is a well-behaved single component landing site for RMCE, it is unclear how reliably single component inserts at other sites in the genome will yield other well-behaved landing sites. Multiple strategies to reduce germline silencing have been developed (Frøkjær-Jensen et al. 2016; Fielmich et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018) and could be incorporated into the single component construct if the problem is common.

In creating the one component vector, I chose to put the mex-5 promoter FLP mNeonGreen operon cassette in between the LoxP site and the rpl-28 promoter such that it was excised by the SEC heat shock step. An alternative would have been to place the cassette between the GFP-his-58 gene and the FRT3 site. In this case, the mex-5 promoter FLP cassette would be excised by the initial integration step. This could be advantageous in that one would remove the source of Flp and germline GFP more quickly in the procedure. However, the mechanism of the integration is likely not via simultaneous recombination at both the FRT and FRT3 sites but is instead likely occurring via a consecutive loop-in at FRT and loop-out at FRT3 (Figure S14). If the frequency of loop-out is related to the distance between the FRT sites, then this might affect the efficiency of the insertion. The current vector has a small FRT3/FRT3 distance compared to FRT/FRT distance, presumably favoring retaining the desired insertion.

The two-component system is lengthier to perform because, after excision of the SEC at the integration site, the strain must be outcrossed to remove the source of Flp (bqSi711). While this takes two generations, serendipitously, bqSi711 is closely linked to him-8 (∼5 μm). Outcrossing creates an insertion; him-8 strain which is convenient for crossing into other genetic backgrounds. A similar strategy can used for any landing site unlinked to bqSi711. Since bqSi711 has proved to be a reliable nonsilencing insert that expresses Flp, new two-component landing sites are likely to be well behaved. Furthermore, the size of the DNA fragment being excised by heat shock is smaller in landing site I, which may explain why the heat shock step appears to be more efficient in this background.

DNA concentration effects on rates of integration

The initial experiments I performed in establishing this method were performed using a mixture of an integration plasmid and carrier pBluescript and rab-3p mCherry plasmids to identify potential lethality in F1 progeny associated with injecting DNA. Though I isolated integrants, I also observed lethality. On multiple F0 plates there were substantially more arrested fluorescent F1 animals than viable F1 Rol animals. I then performed other injections with varied concentrations of total DNA. Although the data are not formally quantified since injections volumes differ substantially among injections and injection quality varies, I plotted all of the results on scatter plots (Figure S13). Of 10 injections with the highest integration frequency, 4 were co-injections where carrier DNA was used in the experiment (Figure S13A). My results indicate that integration events can be obtained at reasonable frequency with a wide range of DNA concentrations from ∼20 ng/μl to over 100 ng/μl. One reason carrier DNA may help increase integration efficiency is due to the mechanism likely facilitating integration. Since most integration events occur late in F1 germline development, the assembly of an initial array that is capable of efficient segregation during mitosis increases the probability that the array will transmit to both somatic tissue (where it expresses an F1 Rol phenotype) and to germline tissue where it improves the efficiency of integration. Additionally, I plotted the integration frequency as a function of the integration site (Figure 13B). These data indicate the range of integration frequencies for the two most widely tested integration sites (two-component landing site I, and single component landing site IVa) are comparable.

Insert size and frequency

The single copy insertions generated using RMCE ranged from 1.6 to 6.2 kb. There was no correlation between insertion size and frequency (Figure S13C), though most of the data points are insertions in the range of 2–3.5 kb. In analyzing the influence of size on insertion frequency, it is more appropriate to consider the size of the insertions at the time they are isolated and homozygosed as Rol animals (9.3–13.9 kb), these being 7.7 kb larger because they contain the hyrRsqt-1 hsp-16p-cre SEC. In practice, it is likely that the size limitations imposed by E. coli during insert vector construction will limit the size of insertions that can be created using the technique in current form.

Use of selection to isolate integration events

Although I designed the integration vectors to permit selection for insertion events using hygromycin, I opted not to use this selection during my initial testing of the method because I felt I would be unable to get accurate data if I could not examine all progeny of my injections. Given that my data suggest many integration events occur in F1 animals, it may be the case that applying hygromycin to F1 animals may not be successful depending on whether somatic mosaic F1 animals survive hygromycin selection. I have, to date, not attempted any experiments to test the utility of hygromycin.

Multiplexing injections

Since the action of Flp is predicted to prevent multimer plasmid insertions, I attempted 11 co-injections of two to four plasmids with the expectation that one could isolate independent integrants of each plasmid from a single injection. This approach works, as I was able to isolate integrants of four distinct constructs in an injection into landing site I (Table S1: injection 149). In other cases, I was able to isolate integrants for a subset of the co-injected plasmids. However, my conclusion from these experiments was that the work involved in characterizing multiple integrants from an injection using PCR and restriction digestions to determine which plasmid is integrated in each distinct isolate is substantially higher than the 30–40 min required per construct to inject the plasmids individually. In addition, one needs to be careful that homologous recombination between the plasmids cannot create novel assemblies. Indeed, jsIs1528, an integration of GAL4SK-QFAD isolated in a co-injection experiment, has an unusual molecular structure that has not been precisely defined (Figure S3H), but clearly contains rtetR sequences in addition to GAL4SK-QFAD. There may still exist circumstances where co-injection of many plasmids may be beneficial. For example, I could envision injecting a large pool of mutant derivatives with distinct lesions in a domain of a protein to map critical residues in the domain by performing the injection in a mutant background and focusing specifically on integration events that fail to rescue.

Attempts to obtain multi-insert integration

I attempted to drive formation of a multi-insert substrate for RMCE integration using the strategy outlined in Figure S11. However, all four integration events I characterized using this strategy integrated only the vector. Since the ratio of non-FRT containing plasmids to integration plasmids was 10:1, I expected that, during array formation, many structures like those shown in Figure S11C would form. This suggests that either large inserts integrate at substantially lower frequency than small inserts, or that suitable substrates rarely form during array assembly, even at the ratios used for injection. Only a small fraction of the insertion vector is homologous to the driver and reporter plasmids. This could result in most recombination events during concatemer formation occurring between identical plasmids, and rarer events occurring between distinct plasmids. In such a scenario, most substrates for recombination would likely be simple integration vectors. It is possible that linearizing the DNAs before injection might alter the assembly of higher order arrays in the germline, and might drive array formation assemblies more compatible with multi-plasmid insertions. However, linear fragments presumably assemble in random orientation and this will create novel arrangements of neighboring FRT and FRT3 sites, which will then be recombined by Flp. Other creative modifications to the RMCE method hopefully will yield approaches that permit simultaneous multi-plasmid integration at a single site.

Advantages and limitations of RMCE integration

The RCME method has several advantages and limitations compared to other methods that can be used to create single copy insertions in C. elegans. The efficiency of RCME is higher than that of MosSCI or CRISPR mediated plasmid insertion and is more faithful in creating complete insertions. However, CRISPR is more flexible in that inserts can be created at virtually any position in the genome. I have created vector backbones that can be used in a SapI Golden Gate reaction to add homology arms to create RMCE landing constructs at novel sites using CRISPR technology. These could also be used to convert well-characterized Mos1 insertion sites (Frøkjær-Jensen et al. 2008) into RMCE landing sites using MosSCI. Thus, combining MosSCI or CRISPR with RMCE may be the most efficient method to create multiple large inserts at specific sites in the genome. Another advantage of RCME is that the same vector construct can be used to insert the same sequence at distinct sites in the genome, as is the case using MosSCI universal landing pads (Frøkjær-Jensen et al. 2014). Perhaps the two most critical advantages of the RMCE procedure are that (1) that every step is associated with a specific change in phenotype that is easy to identify (Figure 1) and (2) that one does not isolate any false positives such as stable extrachromosomal arrays. Because Flp expression in the germline breaks apart arrays, virtually every transmitting Rol line that is obtained is an integrant. By contrast, using ballistic transformation, MosSCI or CRISPR to integrate large inserts, my laboratory has found that many candidate integration events end up being genetic elements that do not behave in a Mendelian fashion, and are likely highly stable arrays. miniMos transposition provides another efficient method with insertion frequencies comparable to RMCE, but these insertions are random, and molecular analysis is required to determine the insertion site. However, only RCME provides both positional specificity and high efficiency.

One limitation of RCME is that it will, in many cases, be incompatible with using Flp-out or Cre approaches for controlling gene expression. RCME inserts created using pLF3FShC and landing sites I, II, IVA, or IVb leave only a loxP and an FRT3 site at the insertion site. Thus, in principle, a Flp-out system using only FRT sites should be compatible in a background containing only a single RCME insert. Transgene development using SECs that use distinct loxP511, loxP2722, or loxN sites (Dickinson et al. 2018; Pani and Goldstein 2018) should be compatible with RMCE insertion at landing sites described herein. However, if a bipartite system is being used that harbors two RMCE inserts, or if a Cre/loxP is system is being used, interchromosomal recombination events between loxP or FRT3 sites at different positions in the genome could create major genomic abnormalities. I have no data assessing the actual frequency of such events.

A second limitation is that it may be difficult to create an RCME insertion in a genetic background that already harbors an RMCE derived transgene. Again, possibilities for interlocus recombination may cause chromosomal abnormalities. How common these events will be is unclear and will likely need to be tested empirically. However, one option currently being tested is the use of alternative landing sites utilizing loxP511, FRT13, and FRT14. In theory, this system will be completely orthogonal to the loxP, FRT, FRT3 system permitting insertion in an RCME background.

An additional limitation of the RCME method, as currently configured, is that it can be difficult to quickly assess the utility of an insertion if it expresses GFP weakly. This is because the landing site background expresses GFP at significant levels in all somatic nuclei and the cytosol of the germline and early embryo. It is not until an insertion is homozygous that somatic nuclear GFP is eliminated, and not until after SEC excision that germline expression is eliminated. Development of landing sites based on a bright red fluorescent reporter for construction of GFP-based transgenes could remedy this issue.

In summary, despite some limitations, RMCE provides a new tool for manipulation of the C. elegans genome that will be particularly powerful in creating complex transgenic tools such as transgenic animals that target multiple different cellular organelles using distinct fluorescent reporters to visualize the dynamics of real-time interactions among cellular components. These tools often require multiple rounds of optimization to develop and are difficult to rapidly integrate because of their size. Combining RMCE with bipartite expression systems should also facilitate the rapid adoption of new reporters to study distinct cell types.

Acknowledgments