Dear Editor,

In December 2019, the coronavirus SARS‐CoV‐2 (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome CoronaVirus 2) was identified in China and the COVID‐19 (Coronavirus Disease 19) infection rapidly spread.

Various cutaneous manifestations have been observed in COVID‐19 patients 1 and there has been worldwide concern among patients undergoing biologic therapies. 2 , 3 , 4 We report our experience with a COVID‐19 psoriatic patient treated with anti‐interleukin‐(IL)‐17 who developed a late onset rash.

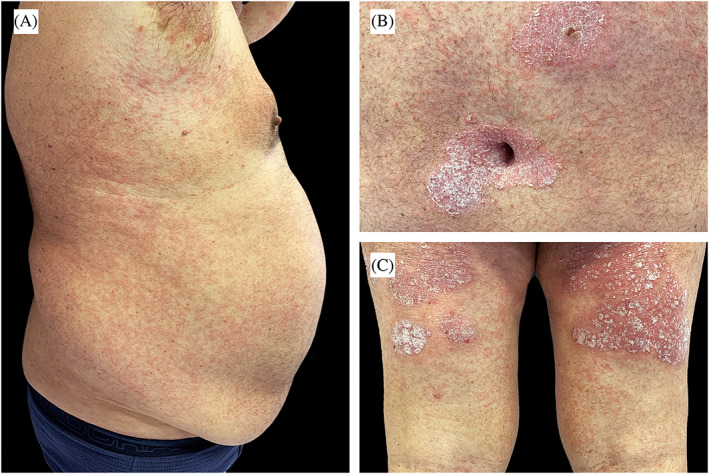

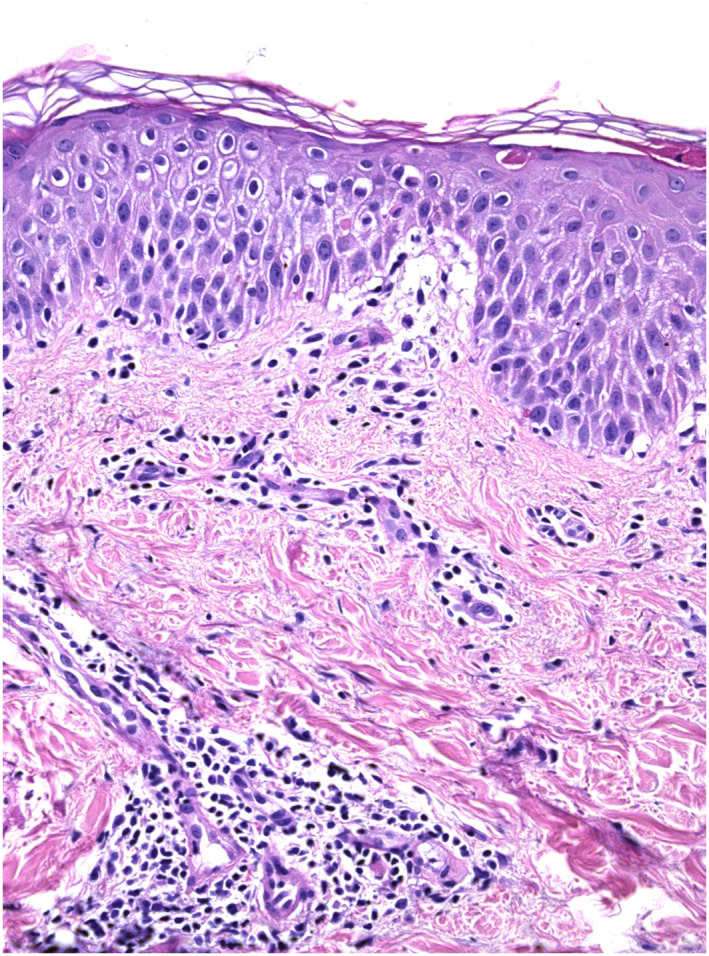

A 69‐year‐old obese, hypertense, diabetic man was previously followed for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis; he was treated with Secukinumab 300 mg every 4 weeks for 2 years. About 25 days after the last dose of Secukinumab he had close contact with his father, who died of COVID‐19 a few days later. In the following days the patient developed mild fever, asthenia, and ageusia, bringing high suspicion of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. After consultation, as precaution, we advised him not to administer the next injection of Secukinumab. All symptoms, except ageusia, were resolved in 5 days. About 5 weeks later, he referred to us due to the rapid onset of a mild pruritic erythemato‐oedematous morbilliform rash, rapidly spreading from arms to trunk and lower limbs; he also showed an initial flare‐up of his psoriasis (Figure 1). The patient was otherwise asymptomatic and denied any recent drug intake; the last Secukinumab administration dated back to 2 months earlier. We collected a nasopharyngeal swab (FLOQSwab, Copan, Italy) in UTM (Universal Transport Medium, Copan, Italy) and two skin biopsies for histology and real time polymerase chain reaction (RT‐PCR) viral detection. One skin biopsy was stored at −80°C in Biobank after treatment with RNAlater‐ICE (ThermoFisher Scientific). Subsequently it was digested with 50 μL of proteinase K (QIAGEN, Germany) and 200 μL of Tris‐EDTA buffer solution (Sigma‐Aldrich, Germany) for 24 hours at 56°C. After the purification of viral RNA from 200 μL of clinical samples, the detection of RdRp, E, and N SARS‐CoV‐2 viral genes were obtained by RT‐PCR (GeneFinderTM COVID‐19 Plus RealAmp Kit, Platform ELITe InGenius, ELITech Group, France) according to WHO protocol. 5 Nasopharyngeal swab was positive, RT‐PCR on skin sample was negative. Histology revealed mild epidermal spongiosis with few necrotic keratinocytes, oedema of the papillary dermis, and moderate lymphocytic perivascular infiltration of the superficial plexus; no eosinophils were observed (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

A, Erythemato‐oedematous morbilliform rash scattered over abdomen and back. B,C, Details of psoriatic plaques associated with erythemato‐oedematous papules

FIGURE 2.

Hyperorthokeratosis, mild epidermal spongiosis, and moderate lymphocytic perivascular infiltration in the papillary and mild dermis (Hematoxylin‐eosin stain; original magnification: ×20)

The skin rash disappeared spontaneously in about 7 days while psoriasis worsened. Only after double negative swab we allowed the patient to restart Secukinumab, with gradual improvement.

The patient developed a mild form of COVID‐19, even though his age and comorbidities are most typically associated with poorer prognosis. 6 The rash occurred about 40 days after the systemic symptoms and approximately 8 weeks after the last Secukinumab dose. The rash appeared together with the recurrence of psoriasis. At the onset of the rash, the patient still had a positive swab, but the RT‐PCR search for viruses in the skin was negative.

These observations seem consistent with the hypothesis of cytokine storm and Th17 involvement in the pathogenesis of COVID‐19 and COVID‐19‐related cutaneous manifestations. 3 , 4 , 7 In our case, the COVID‐19 clinical course was mild and therefore we can assume secukinumab does not increase risks for the patient and could support the hypothesis of the possible therapeutic use of IL‐17 inhibitors in COVID‐19. 7 , 8 , 9

The mechanisms of COVID‐19 cutaneous manifestation are still not well known. 1 The appearance of the manifestations 8 weeks after the last dose of the drug and the negativity of skin research of the virus with RT‐PCR seem more consistent with the hypothesis of inflammatory pathogenesis than with the presence of peripheral viral particles. Further observations are needed to confirm these hypotheses.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The patient in this manuscript has given written informed consent to publication of his case details. We wish to express our gratitude to Dr. Fabio Maria Carugno and Dr. Matteo Alberto Mariani for their precious help and advice.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brownstone ND, Thibodeaux QG, Reddy VD, et al. Novel coronavirus disease (COVID‐19) and biologic therapy in psoriasis: infection risk and patient counseling in uncertain times. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2020;10(3):1‐11. 10.1007/s13555-020-00377-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Magnano M, Balestri R, Bardazzi F, Mazzatenta C, Girardelli CR, Rech G. Psoriasis, COVID‐19 and acute respiratory distress syndrome: focusing on the risk of concomitant biological treatment. Dermatol Ther. 2020;e13706. 10.1111/dth.13706. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Garg S, Garg M, Prabhakar N, Malhotra P, Agarwal R. Unraveling the mystery of Covid‐19 cytokine storm: from skin to organ systems. Dermatol Ther. 2020;e13859. 10.1111/dth.13859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sachdeva M, Gianotti R, Shah M, et al. Cutaneous manifestations of COVID‐19: report of three cases and a review of literature. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;98(2):75‐81. 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) by real‐time RT‐PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):pii=2000045. 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jordan RE, Adab P, Cheng KK. Covid‐19: risk factors for severe disease and death. BMJ. 2020;368:m1198. 10.1136/bmj.m1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pacha O, Sallman MA, Evans SE. COVID‐19: a case for inhibiting IL‐17? Nat Rev Immunol. 2020;20(6):345‐346. 10.1038/s41577-020-0328-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Zumla A, Hui DS, Azhar EI, Memish ZA, Maeurer M. Reducing mortality from 2019‐nCoV: host‐directed therapies should be an option. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):e35‐e36. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30305-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Bashyam AM, Feldman SR. Should patients stop their biologic treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. J Dermatolog Treat. 2020;31(4):317‐318. 10.1080/09546634.2020.1742438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]