President Donald Trump’s call to end the domestic HIV epidemic in his 2019 State of the Union address may have taken some listeners by surprise. Many Americans consider HIV to be a plague of the past — a problem now resolved. For others, the initiative seems at odds with the Trump administration’s other health policy priorities, which include efforts to repeal the Affordable Care Act, restrictions on access to reproductive health services, and opposition to harm reduction for people who inject drugs — approaches that have undermined both access to health care and the civil rights of people in many of the communities hit hardest by HIV. Yet the effort is welcome and the goal is achievable, assuming it is informed by the latest advances in science and public health, as well as by earlier bipartisan initiatives to tackle HIV on the global stage.

The past three decades have seen enormous progress in confronting HIV, even in the absence of an effective vaccine or a cure. An ever-expanding array of antiretroviral drug combinations has transformed HIV infection from a “death sentence” to a chronic and manageable condition. Treatment has also been shown to eliminate the risk of HIV transmission to sexual partners, and new prevention methods, including needle-exchange programs and preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) with antiretroviral drugs, are highly effective.

Despite these tools, HIV is not a problem of the past in the United States. In 2010, we called attention to the persistence of the domestic epidemic.1 Since then, progress has been slow. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that 1.1 million Americans are living with HIV and that more than 15,800 people with diagnosed HIV died in 2017.2 For nearly a decade, the United States has been unable to reduce the number of new HIV infections below a startling 38,000 to 40,000 per year.3 Moreover, the epidemic is still growing rapidly among subgroups in the black and Latino communities, and recent data indicate that less than 20% of Americans who could benefit from PrEP have received it. These sobering realities raise two critical questions: Why is the United States falling short? And how feasible is the administration’s ambitious new goal?

HIV affects the most vulnerable among us. More than two thirds of new infections occur among people who are economically disenfranchised or ethnic, racial, or sexual minorities. In 2017, of new infections reported in U.S. men, 56% were in black and Latino men who have sex with men, a group that represents less than 1% of the U.S. population. HIV prevalence is much higher among transgender women than among the general population, and women of color bear most of the burden of HIV among U.S. women. In addition, injection drug use in the context of the opioid crisis has resulted in HIV outbreaks, particularly in rural areas of the country with historically low HIV prevalence and often underdeveloped HIV services.

Members of these diverse populations face stigma, are affected by legacies of mistrust of the medical system, and have often had negative experiences with the health system themselves, all of which create barriers to engagement with HIV testing, prevention, and treatment services. People who are most likely to be living with or to acquire HIV are frequently living in poverty, without stable housing or reliable health insurance, which hinders their access to care within the fragmented U.S. health care system. Moreover, the U.S. epidemic is not evenly distributed geographically; the highest rates of infection are in urban centers along the coasts and increasingly in smaller towns and rural areas in the South.

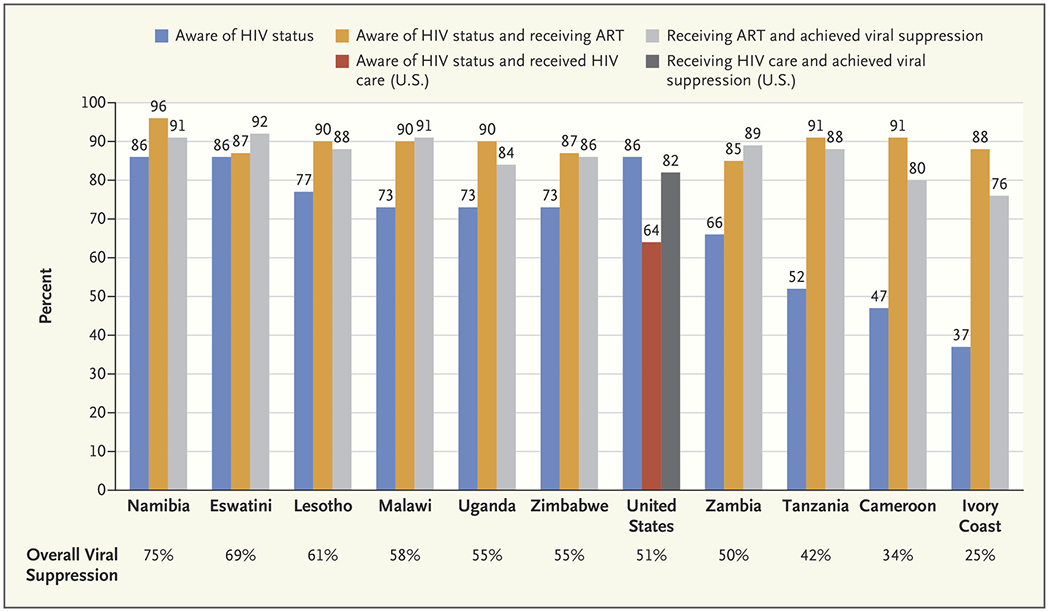

More than 16 years ago, another U.S. president made a dramatic promise about HIV in a State of the Union address. In 2003, President George W. Bush launched the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), an unprecedented effort to con-front the HIV epidemic devastating some of the poorest countries in the world. Today, more than 21 million people living with HIV, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa, have access to lifesaving treatment. Recent population-based HIV surveys show remarkable progress, including that some lower-income countries are achieving what the United States has yet to achieve — decreasing numbers of new infections. Remarkably, several African countries are on their way to achieving epidemic control, with rates of linkage to HIV treatment and viral-load suppression that are higher than those in the United States (see graph). When PEPFAR was launched, the goal was to share American resources and know-how with the rest of the world. Although much remains to be done to control the global epidemic, it is now time to ask ourselves what we can learn from Africa’s HIV response in order to control the HIV epidemic in the United States.

Diagnosis and Treatment Status of Persons Living with HIV in Ten African Countries and the United States.

Overall viral suppression is the percentage of all people with HIV in whom the virus is suppressed. U.S. data are based on HIV measures that use slightly different denominators from those in other countries. Data are from ICAP at Columbia University and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

One lesson is to use a public health approach. This strategy involves bringing services to everyone who needs them, rather than focusing on the privileged few who have the resources to obtain and pay for treatment. Bringing HIV services closer to where people live, at no cost to them and in culturally acceptable ways, was a critical strategy that turned the tide in some regions in Africa. HIV diagnosis, treatment, and prevention were simplified to enable such services to be provided more effectively and efficiently by nurses and other nonphysician health workers, including by community health workers who reached out beyond clinic walls, rather than by scarce physicians. This approach is highly relevant to the epidemic in the United States, where financial barriers and lack of adequate health insurance coverage limit access to HIV services.

Another critical lesson involves the importance of engaging communities in ways that mitigate stigma and discrimination. HIV programs in Africa rely on people living with HIV reaching out to others who have felt forgotten, helpless, and shunned. This emphasis on solidarity contrasts with the sense of isolation and alienation that many vulnerable Americans may feel as sexual, racial, or ethnic minorities or because they are poor. Embracing the U=U (undetectable equals untransmissible) approach, which acknowledges that people living with HIV who are treated effectively won’t transmit HIV to their partners, can help combat stigma. Protecting the civil liberties and dignity of all people is essential to a successful domestic HIV response.

Effective responses to the HIV epidemic must also embrace evidence-based interventions identified through rigorous research. The global community has consistently and rapidly incorporated new evidence as it has been identified, adopting new approaches to HIV testing, new antiretroviral drugs, and evidence-based prevention strategies such as PrEP. Denying scientific evidence in favor of political expedience can be disastrous, as Indiana learned when its rejection of needle-exchange programs led to the worsening of a preventable local HIV outbreak.4

Most important, the global response has been built on the principle of “know your epidemic” and on reaching ambitious targets. Data from population-based surveys and national program performance are carefully, yet rapidly, examined and used to determine where countries should intervene, whom they should aim to reach, and what types of interventions and services they should prioritize. Given the demographic and geographic heterogeneity of the U.S. epidemic, this type of approach is essential. The plan to focus the U.S. response on the counties and municipalities most severely affected by HIV is an important step forward, enhanced by the establishment of specific goals for the new initiative.5 Such goals will need to be supplemented with specific targets at the local level to concentrate efforts and drive action.

We are encouraged by the reenergized commitment to tackling the U.S. HIV epidemic. Ending AIDS as a public health threat in the United States is achievable, but it will not be a simple endeavor. It will require the commitment of sufficient resources and a fierce determination. It will require setting ambitious targets and milestones for prevention and treatment, engaging and respecting affected communities, using the best scientific evidence, and conducting repeated assessment to gauge progress and realign programs as needed. Most important, it will require concerted and genuine efforts to overcome the economic, cultural, and social barriers that prevent disenfranchised and vulnerable people from obtaining the services they need.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Disclosure forms provided by the authors are available at NEJM.org.

An audio interview with Dr. El-Sadr is available at NEJM.org

References

- 1.El-Sadr WM, Mayer KH, Hodder SL. AIDS in America — forgotten but not gone. N Engl J Med 2010;362:967–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS basic statistics (https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html).

- 3.CDC data confirm: progress in HIV prevention has stalled. Press release of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, February 27, 2019. (https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2019/0227-hiv-prevention-stalled.html).

- 4.Peters PJ, Pontones P, Hoover KW, et al. HIV infection linked to injection use of oxymorphone in Indiana, 2014–2015. N Engl J Med 2016;375:229–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA 2019;321:844–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.