Abstract

The COVID‐19 pandemic has a pervasive effect on all aspects of family life. We can distinguish the collective societal and community effects of the global pandemic and the risk and disease impact for individuals and families. This paper draws on Rolland’s Family Systems‐Illness (FSI) model to describe some of the unique challenges through a multisystemic lens. Highlighting the pattern of psychosocial issues of COVID‐19 over time, discussion emphasizes the evolving interplay of larger systems public health pandemic challenges and mitigation strategies with individual and family processes. The paper addresses issues of coping with myriad Covid‐19 uncertainties in the initial crisis wave and evolving phases of the pandemic in the context of individual and family development, pre‐existing illness or disability, and racial and socio‐economic disparities. The discussion offers recommendations for timely family oriented consultation and psychoeducation, and for healthcare clinician self‐care.

Keywords: COVID‐19, Pandemic, Family, Biopsychosocial

Resumen

La pandemia de la COVID‐19 tiene un efecto generalizado en todos los aspectos de la vida familiar. Podemos distinguir los efectos comunitarios y sociales colectivos de la pandemia mundial, y el riesgo y el efecto de la enfermedad en las personas y en las familias. Este artículo hace uso del modelo de Sistemas Familiares y Enfermedad (Familly Systems Illness Model) de Rolland para describir algunos de los desafíos únicos que plantea la pandemia desde una perspectiva multisistémica. Destacando el patrón de problemas psicosociales de la COVID‐19 conforme avanza el tiempo, el debate enfatiza la interacción emergente de los desafíos que plantea la pandemia en sistemas más grandes como la salud pública y las estrategias de mitigación con procesos familiares e individuales. El artículo aborda los problemas del afrontamiento con innumerables incertidumbres sobre la COVID‐19 en la fase de crisis inicial y en las fases posteriores de la pandemia en el contexto del desarrollo individual y familiar, de discapacidades o enfermedades preexistentes, y de disparidades raciales y socioeconómicas. El debate ofrece recomendaciones para una consulta orientada a la familia y una psicoeducación oportunas, así como para el cuidado personal de los médicos de atención a la salud.

摘要

COVID‐19新冠肺炎疫情对家庭生活的各个方面都有普遍影响。我们可以区分全球性的疫病对作为整体的社会和社区的影响以及对个人和家庭的风险和疾病影响。本文借鉴了罗兰德的家庭系统疾病(FSI)模型,通过多系统视角描述了一些独特的挑战。本文突出强调了一段时期以来,COVID‐19带来的心理社会问题的模式,讨论的内容也强调了更大系统的公共健康流行病挑战与缓解战略两者之间不断变化发展的相互作用,这种缓解策略关系到个人和家庭过程。本文讨论了在个人和家庭发展、既往疾病或残疾以及种族和社会经济差距的背景下,在危机初期和疫情演变阶段中应对大量新冠肺炎不确定性的问题。本讨论为适时进行家庭咨询、心理教育及医疗保健临床医生的自我保健提供了建议。

The novel coronavirus‐19 pandemic presents unique challenges for individuals and families. With the current lack of an effective treatment or a preventive vaccine, all aspects of life are affected (Luttik et al., 2020). Stringent mitigation efforts, such as social distancing, household quarantine, facemasks, vigilant hand washing, and avoidance of public gatherings and transportation, were instituted in the United States in March 2020 and are likely to continue in some form for the foreseeable future.

The COVID‐19 pandemic has unmasked the stark reality and profound health and economic consequences of glaring socio‐economic and healthcare disparities. Risks for morbidity and mortality vary enormously by social location, in particular, race, social class, gender, age, ability, and geographic location (CDC, 2020; Price‐Haywood, Burton, Fort, & Seoane, 2020).

COVID‐19 Disease: Multisystemic Impact

With the COVID‐19 pandemic, we can conceptualize macro‐ and individual/family levels of the disease experience over time: (1) adaptation to the pandemic risk as a collective society or global community, (2) coping with the risk of contracting COVID‐19 for individuals and families, and (3) coping with the disease itself for affected individuals, their families, and networks. A multisystemic lens can help us understand the pandemic’s impact across these levels, thereby facilitating our clinical work.

At the societal level, there is the status and course of the broader pandemic for the global human family. This level includes the characteristics of this virus (e.g., how it manifests, its virulence, ease of human‐to‐human transmission), evolving prevention (vaccine), treatment options, and the incidence of new cases in different regions over time. Also, it includes the national and local availability and access to adequate healthcare system testing and disease management resources (e.g., emergency departments, ICU beds, ventilators). Progress or setback at this larger system level influences public health and region‐wide phase‐oriented recommendations that affect local communities, individuals, and families. This macrolevel encompasses the myriad disruptions wrought by the pandemic, such as upending daily life, employment, economic impact, and healthcare system overload.

The dominant, ongoing impact of the macro‐COVID‐19 pandemic level is particularly striking compared to chronic illnesses or most other infectious disease epidemics. For instance, HIV/AIDS has been predominant in high‐risk subpopulations of gay men, intravenous drug users, and those with hemophilia in transmission through direct exchange of bodily fluids (e.g., blood). With COVID‐19, transmission is widespread, primarily airborne, highly and rapidly contagious, and potentially lethal, putting everyone at increased risk.

At the individual and family level, the COVID‐19 disease is experienced as personal risk, and with infection, the course, and recovery or fatality. With a pandemic, individuals and families are continually dealing with developments at all levels. It is useful to inquire about and frame adaptation in those terms. Most people focus on their local situation and risks in their daily lives, job, family, and social network—getting food, medicine, and other needs.

This discussion will highlight the individual and family experience. Also, this paper is written in the midst of the pandemic when some of the emerging issues, such as if and when of second or third waves/spikes of cases, the timing of a vaccine or economic recovery, and the ultimate scale of emerging mental health and psychosocial impact remain uncertain (Amsalem, Dixon, & Neria, 2020; Wanga et al., 2020).

Overview of Family Systems‐Illness Model

How can we organize this complex COVID‐19 landscape in a manner helpful to families and clinical practice? The Family Systems‐Illness (FSI) model (Rolland, 2016, 2018, 2019) provides a useful framework for assessment and treatment with families dealing with a range of serious and chronic illness and disability, including infectious disease (see Rolland (2018) for useful resources, practice guidelines, and case examples).

The FSI model is grounded in a strengths orientation, viewing family relationships as a potential resource and emphasizing possibilities for resilience and growth (Walsh, 2016). Seeing the family as the interactive focal point, this approach attends to the systemic interaction between an illness and family that evolves over time. The goodness of “fit” between the psychosocial demands of a particular condition over time and the family style of functioning and resources is a prime determinant of successful versus dysfunctional coping and adaptation.

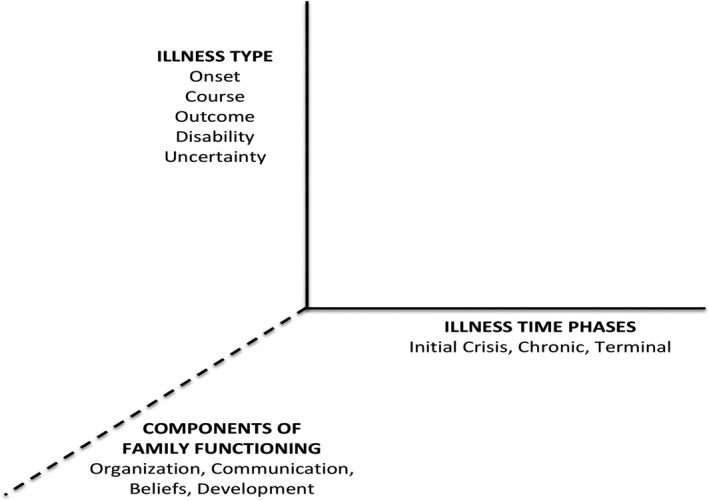

The FSI model focuses on three dimensions of experience: (1) a psychosocial typology of chronic conditions; (2) major time phases in their evolution; and (3) key family system components. In addition to communication processes and organizational/structural patterns, particular emphasis includes family and individual life course development in relation to the time phases of a disorder; multigenerational legacies related to illness and loss; and belief systems (including influences of culture, ethnicity, race, spirituality, and gender; Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Family Systems Illness Model: Three Dimensions.

COVID‐19 Disease Considerations

COVID‐19 is a novel coronavirus infectious disease. To create a normative context for the pandemic experience, families can benefit from a psychosocial map as they navigate overwhelming challenges. First, the psychosocial map offers an understanding of COVID‐19 in systems terms, which explicates the expected (or uncertain) pattern of practical and emotional demands of this disease over the course of the pandemic. Second, such maps are helpful for families in understanding systemic processes.

In the FSI model, illness patterning can vary in terms of type of:

Onset (acute or gradual)

Course (resolves versus progressive, constant, relapsing)

Outcome (nonfatal to fatal)

Type and degree of disability or complications

Level of uncertainty about its trajectory.

Some diseases have clear‐cut predictable patterns, such as ALS, which is gradual onset, progressive, disabling, and fatal. By contrast, COVID‐19 manifests in a variety of unpredictable ways. For most, it is not a chronic illness, but for some, it has long‐term health consequences. For some, it is fatal.

Despite significant risk differences related to social location, age, and health status, anyone can be infected and then can transmit COVID‐19; anyone may develop a severe case and may die. Unlike other infectious diseases that run their course in known timeframes or are seasonal and/or regional, currently, there is no known endpoint to the COVID‐19 pandemic. This uncertainty and indeterminate timeframe are particularly taxing in a cumulative way—pandemic fatigue. Further, data are accumulating that recovery can be protracted and result in long‐term medical complications—cardiovascular, pulmonary, and neuropsychiatric are among the most common (Long, Brady, Koyfman, & Gottlieb, 2020; Varatharaj et al., 2020).

Pre‐Existing Chronic Illness and Disability

In the United States, six in ten adults have a chronic illness (NCCDPHP, 2020), which medically heightens their risk of getting COVID‐19 and increases the risk, to varying degrees, of a severe case and mortality. One in four adults has a chronic disability. The pandemic magnifies longstanding prejudices toward those with disability, stigmatizing and treating them as inferior. Many in the disability community fear that their lives would be expendable in circumstances of a shortage of adequate COVID‐19 testing, ICU beds, respirators, and response resources. Ageism contributes to attitudes that older persons are expendable. Compared with younger and disease‐free individuals, older adults and those with pre‐existing chronic conditions must grapple with higher risk of complications and deciding their acceptable social risk as COVID‐19 restrictions are relaxed. Individuals and families with an already chronically ill or disability‐challenged member may be far less able to absorb the added caregiving burdens if either an affected member or a primary caregiver develops COVID‐19.

Living with the Uncertainties of COVID‐19

Uncertainties and unknowns abound with COVID‐19. Perhaps the most challenging are the facts that transmission is invisible and many individuals that carry the disease, maybe even most, are asymptomatic, yet contagious. These disease characteristics heighten the experience of living with risk and anticipatory loss (Rolland, 1990, 2018). For example, the ambiguity of being at risk versus an asymptomatic carrier would increase fears of transmitting COVID‐19 to an older or chronically ill at risk family member. The importance of viral load (the concentration of virus in saliva) in COVID‐19 severity is established, but the length of exposure and the level of viral load needed for infection to occur are still ambiguous. Further, the incubation period, although on average five days, can vary from 2 to 14 days. Technically, this means that if someone wants to visit an individual at higher risk beyond the socially distanced visit, they should consider self‐quarantine for fourteen days beforehand. For many families, this is not feasible or realistic. Now, the discussion is about safe “social pods” visiting with others who are practicing safe protections.

Individual uncertainties include:

Unpredictable course. Some who are infected seem fine then progress rapidly to a life‐threatening state (See the case description below). Some appear to be improving and then take a turn for the worse. This necessitates ongoing monitoring and vigilance by family members for a protracted period.

Uncertainty regarding long‐term complications (e.g., cardiac, respiratory, CNS). Recovery has proven slow, and ongoing complications may occur, even in those who were asymptomatic. This puts the affected member and family members into a protracted period of limbo. They do not know what will be the eventual new normal. Key questions for families include “What caregiving and role functions may need longer‐term reevaluation?” and “What additional economic strains would this create?”

Larger collective public health uncertainties include:

Who has been infected? Who has immunity and for how long? Antibody status and degree and length of time of protection from antibodies are not yet well understood (Robbiani et al., 2020).

How long until an effective and widely available vaccine emerges or until herd immunity (roughly 70% of total population has developed antibodies) negate the impact of the disease? Despite some horrific initial spikes, such as New York City, the proportion of individuals that have been infected with COVID‐19 in these hot spots is only 10% of the population.

Incidence and fatality trends can improve in one region, but then spike in another region. A second or third wave of resurgence is very likely, unless widespread readily accessible testing and contact tracing are implemented, and the public adheres to ongoing and shifting precautions. As of July 2020, we are seeing the dire consequence of too rapid state‐level relaxation of restrictions and resulting widespread disregard of key precautions (e.g., mask usage).

Without strong national leadership, regulations, and guidelines, regional improvements and surges can occur independently. From a public health standpoint, often divergent and sometimes politically motivated state‐based regulations are epidemiologically nonsensical. Locally, individuals and their families lack clear, consistent information and guidelines. This chaotic process is both medically dangerous and psychologically exhausting.

These myriad individual and population level uncertainties have significant impact on and implications for families. As this is written in July 2020, the cumulative mental and physical health consequences of this “pressure cooker” existence are just beginning to emerge (Killgore et al., 2020; Wanga et al., 2020). Living well with illness uncertainties and threatened loss (Rolland, 1990, 2018) entails acknowledging the possibility of loss, sustaining hope, and building flexibility into planning that can accommodate changing circumstances. Similar to living with chronic illness, the metaphor that living with the uncertainties of the pandemic is a marathon not a sprint is apt and clinically useful.

Disparities for Lower Income and Minority Families

Systemic racism has a profound impact on COVID‐19 susceptibility. July 2020 CDC data reveal that Latinx and African‐Americans are three times as likely to become infected with COVID‐19 as their white neighbors throughout urban and rural regions of the United States and across all age groups. And, they are twice as likely to die from the disease as white people. Native American people also experience similar disparities.

Lower income families, disproportionately African‐American, Latinx, and immigrant, rely on income from members working in job conditions at high risk of infection. Crowded multigenerational living conditions make social distancing difficult in households (CDC, 2020). Living with racial residential segregation, at a distance from healthcare facilities and grocery stores, makes it harder to get needed care or garner supplies for stay‐at‐home precautions. Lower income families’ livelihoods require leaving home and taking public transportation daily to work in the service sector, factories, and/or other crowded conditions, where personal safety is often compromised for the sake of a paycheck needed for family survival. These families live with the daily fear that COVID‐19 will be brought into the home from work settings and travel to and from work. The ability of most white‐collar desk jobs to be accomplished remotely has provided double protection—preventing COVID‐19 infection and keeping one’s job. This is a huge advantage over jobs requiring physical presence. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the Director of the National Institute for Allergy and Infectious Diseases, stated at a US Congressional hearing (Fauci, 2020 June 23, 2020) that the coronavirus has been a “double whammy” for African‐Americans, because they are more likely to be exposed to the disease by way of their employment in jobs that cannot be done remotely. Second, they are more vulnerable to severe illness from the coronavirus because they have higher rates of underlying conditions like diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, and chronic lung disease (Bolin & Kurtz, 2018; Cunningham et al., 2017). These individuals often lack health insurance or are underinsured and lack access to adequate basic health care, including paid family and medical leave (Bartel et al., 2019). This leaves them and their families extremely vulnerable to severe illness and economic ruin if COVID‐19 strikes. Almost two‐thirds of US bankruptcies are linked to illness and unaffordable medical bills (Himmelstein, Thorne, Warren, & Woolhandler, 2009). The need for an “improved Medicare for all” national healthcare system could never be more urgent.

Communication

COVID‐19 is a risk to all family members, and prevention requires an understanding of mitigation strategies within the household and in the community. This necessitates ongoing effective communication among family members of all ages.

Children coping with chronic illnesses, such as diabetes or asthma, need to learn about their illness and aspects of self‐management from an early age. The COVID‐19 pandemic warrants the same mind‐set, although here healthy children (and adults) may be introduced for the first time to a “new reality” of personal disease risk. It is valuable to inquire whether anyone is protected in or excluded from such discussions (e.g., children; or aged, frail, or vulnerable family members) and why. Adults may feel reticent to share with children given the uncertain nature of COVID‐19, but communicating age‐appropriate information about the disease supports psychological well‐being for the child and the family (Dalton, Rapa, & Stein, 2020). The pandemic may reveal sharp differences between partners regarding beliefs about appropriate safety restrictions for children or each other (Grose, 2020). Couples need to discuss these differences, which may warrant additional input from primary care providers.

Individual family members may process the same COVID‐19 information through very different historical, cultural, and political ideological filters, leading to conflicting views. It is crucial to understand beliefs about what can cause or prevent COVID‐19 and personal risk perception. Research has repeatedly shown that the perception of risk is a more powerful behavioral motivator than actual risk (Ferrer & Klein, 2015). Given COVID‐19 is highly transmissible nature, perceptions of relative invulnerability and disregarding precautions can put all family members at risk. Teenagers and young adults often ignore social distancing and mask use out of a belief in personal invulnerability.

It can be enormously helpful for families to hold regular family “meetings” to review daily life together during the pandemic and make any needed adjustments. Where possible, tele‐technology can enhance such pragmatic discussions by facilitating inclusion of family members living at a distance and separated by pandemic precautions. Families at higher risk benefit from proactive discussions or consultations about role function flexibility and other potential extended family, community, or healthcare provider resources. This might include adult children (and their parent(s)) conferring about shared responsibilities to protect an elder or tend to them if COVID‐19 strikes. Another example is proactive discussions among parents and with their teenage children about any misguided sense of invulnerability.

Unified national public health communication

Disagreements about appropriate safety precautions can occur among family members, between neighboring families, between states, and sadly often divide along political party lines. We need one data‐driven and unified national public health mandate on precautions and adequate testing, which is separated from politicians and divergent political agendas. This would save countless lives. It must be well funded across socio‐economic and minority group strata. Compared to other countries strategies over time, US failings at a national level are increasingly and blatantly clear. A unified message would greatly help galvanize state, community, and family level buy‐in and cohesion.

Gender

Although most contemporary couples and families strive toward flexible and equitable gender role relations, the influence of culturally based gender norms persists for caregiving roles (Knudsen‐Martin, 2012). As a health crisis, COVID‐19 heightens the tendency to expect women to absorb the bulk of child and elder care and attend to the practical and emotional needs of an ill member. It is crucial to explore family expectations about caregiving roles. Encourage flexibility and a shift from defining one female member as the caregiver to that of a collaborative caregiving team (Walsh, 2016).

Geographic Distance, Elders, Living Alone

With the geographic dispersion of many families, members may need to accept not seeing loved ones for an indeterminate period. Elders, especially those that are frail and chronically ill, consider that they may not see members living at a distance again. Adult children and grandchildren might not see an older parent again. This possibility always is present, yet, is heightened with the pandemic. Families can harness this fact to appreciate each other more fully, express caring, and use it as an opportunity to repair and heal relationship wounds. Similar to many people living with the uncertainties of a life‐threatening illness, the pandemic can stimulate a sense of urgency for family members to deal with unresolved relational issues.

Whether living near or far, adult sons and daughters have to weigh under what circumstances they would visit their elder parents. If their parents contract COVID‐19 or develop a different health crisis, would they accept the risk of seeing them and providing caregiving, thereby putting themselves and their own children at risk. Conversely, adult children often fear bringing the infection to their older parents, who are at higher risk. These are profoundly difficult questions, warranting proactive family discussion and consultation with healthcare providers. Adult children need to discuss these issues within their own nuclear family. A spouse or partner may have different views about acceptable risk as well as their own aging parents or kin to consider. As the pandemic continues to evolve, these discussions will need to be revisited—relating to new COVID‐19 data and to changing family circumstances, such as life cycle transitions or altered economic and health status.

Those living alone, especially seniors, are at increased mental health risk for anxiety, depression, even suicide during the pandemic (Aronson, 2020). They can experience despair that meaningful social contact and purpose will no longer occur within the timeframe of their remaining years. They typically lack the support and companionship provided by a spouse, partner, or sibling, for instance. Other family members carry additional concerns about the vulnerability of an isolated member.

Social media and tele‐technology options (e.g., Zoom, FaceTime, Skype) have provided ways for family members and friends to remain more connected. Many families have actually had this option for several years, but are now discovering its utility for the first time. Geographically dispersed members can gather for a weekly Zoom meeting. Grandparents can have a play date with grandchildren. Despite the two‐dimensional shortcomings and oft heard complaint that it is not the same as in‐person, this technology enables clinicians to more easily convene family members for health and mental healthcare consultations and therapy. However, lower income families often lack the computer resources to avail themselves of this technology, adding another layer of disparity.

Long‐Term Care Facilities

Long‐term care facilities (LTCF) are a major challenge for safety during the pandemic. June 2020 data revealed that in most states, a staggering 50%–80% of COVID‐19 related deaths occur in LTCF (D’Adamo, Yoshikawa, & Ouslander, 2020). Families may need to evaluate the relative safety of leaving a family member in a LTCF or bringing them to live with them. Data show that persons with cognitive impairment are four times more likely to die of COVID‐19 in a LTCF than other residents (Census Bureau & CDC:NCHS, 2020). Lack of judgment, impulsiveness, and confusion with dementia all interfere with risk reduction behavior. Those with dementia or intellectual disabilities may be particularly distraught and not comprehend why family members are not able to visit. A family caregiving for an elder with advancing Alzheimer’s disease, that is becoming unmanageable at home, may have to make a wrenching decision between their own limits and personally caring for a loved one. Consultation with involved primary care, specialist, and family behavioral health providers can guide and support family decision‐making. Fortunately, use of technology through video conferencing allows persons who are hospitalized or in LTCF and their loved ones to sustain vital contact. This is especially important in situations of advanced chronic illness or COVID‐19 where death may ensue without loved ones physically present again.

Time Phases of COVID‐19 Pandemic and Disease Considerations

Applying the FSI model, time phases can help us understand two levels: (1) the course of the COVID‐19 pandemic and (2) the experience living with personal COVID‐19 risk and infection over time. This section discusses the evolving challenges at both levels for individuals and families (Rolland, 2018).

COVID‐19 Pandemic Time Phases

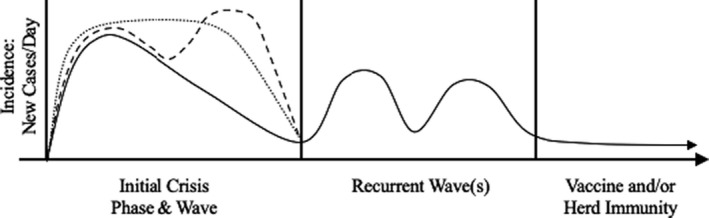

Despite the uncertainty of the future pandemic unfolding, we can diagram a timeline (Figure 2). The pandemic level phases are intended to clarify psychosocial challenges over time rather than emphasize COVID‐19 biological or public health incidence and prevalence. Core psychosocial themes in the evolving course of the COVID‐19 pandemic can be conceptualized into three broad phases. The initial crisis phase is characterized by a wave of cases with varying course, indeterminate length, and potential spikes. For some countries, this initial phase/wave subsided within a few months. In the United States, as of July 2020, with a rising spread of cases and regional spiking, it is unclear when the initial wave will end. In the next phase, a second wave is predicted with the potential for one or more following waves. In the final phase, the course of the pandemic spread diminishes as herd immunity is reached, with or without a vaccine. The pattern of the initial crisis wave has varied considerably in different regions. Figure 2 illustrates several general patterns in the initial crisis wave and recurrent wave(s).

Figure 2.

Covid‐19 Pandemic Timeline.

Initial crisis phase and wave

With the current pandemic, the initial crisis phase involves adaptation to the societal risk for everyone. Depending on social location, the entire population was presented with the medical risks of COVID‐19 as well as mitigation and prevention measures. Families needed to reorganize family life, including roles and routines, and communicate about practical and emotional challenges of living with the pandemic. Acknowledging risk is needed while maintaining hope. It is vital that families see the COVID‐19 pandemic as a shared challenge in “We” terms both at a community and family level.

Because this is a novel virus, our understanding of medical risks has been evolving as new and more population level data emerge. This changing landscape has been complicated by multiple scientific and political voices with different priorities and agendas. Healthcare experts and policy‐makers often vehemently disagree about whether to prioritize disease prevention or immediate economic recovery strategies. The lack of a unified message in the face of a life‐threatening illness is akin to multiple and divergent medical opinions that can leave families bewildered and frightened, often leading to opposing and conflicted viewpoints about what is needed. This pattern increases the likelihood that dysfunctional family patterns will emerge or pre‐existing ones will be exacerbated.

The economic consequences of the pandemic, stark witnessing and worsening of racial and socio‐economic disparities, and the need for COVID‐19‐related health precautions are all simultaneously important. Yet, immediate priorities, such as continued vigilant COVID‐19 illness prevention and back‐to‐work imperatives in the face of massive unemployment has collided both at the macrosocietal level and among family members. The relative weighing of these different risks and options can vary enormously depending on social location. More affluent families can prioritize COVID‐19 risk management because of a more secure economic base. Most working and middle class families, who live with economic strains, cannot afford to prioritize health unless protected economically by continued government subsidies.

Psychosocial transition period

With persistence of the initial wave, many individuals and families have shifted from a crisis reactive mode to a longer‐haul mind‐set. Where the initial wave has subsided, others may hold onto hope that there will be no second wave. Whenever this psychosocial transition occurs, it involves fuller acceptance of the ongoing nature of the pandemic and living with COVID‐19 uncertainty/risk and threatened loss. It is a period when families may consider modifying precautions and reorganizing to adapt to a more protracted coping with the pandemic. The emotional strain of living with COVID‐19 risk can feel heightened as they experience the realities of living with an ongoing pandemic. As discussed below, the enormous variation in timing and unfolding of COVID‐19 new case trajectories locally, regionally, and nationally adds ambiguity to when this transition is salient for a particular family or community.

Recurrent wave(s) phase

As with the initial crisis phase/wave, one can conceptualize a more indeterminate length recurrent wave phase in the COVID‐19 pandemic. This is distinct from an infected individual living with a chronic phase of COVID‐19.

COVID‐19 is not the only threat to health and well‐being. As Aronson (2020) notes, the challenge for individuals and a society, is that two contradictory realities are simultaneously true. Our approach to pandemic containment works, but our approach causes suffering, eroding physical and mental health, and causing economic dislocations. This affects everyone, but especially individuals with pre‐existing chronic illness, disability, in later life, and/or subject to socio‐economic and racial disparities. The key is to sustain daily structure and meaningful purpose. Digital technology facilitates roles for elders, for instance, in connecting with grandchildren, volunteering to help the less advantaged, or political activism.

Increasingly with COVID‐19, many families struggle with the ongoing challenges of being confined at close range for extended and open‐ended time. In the United States, many parents needed to negotiate more flexible childrearing roles to accommodate having their children home 24/7 without going to school, having after school activities, and depending on usual daycare. With special needs children (e.g., autism, cerebral palsy, intellectual disability) or adults (e.g., serious mental disorders, acquired brain injury), families are managing alone without the usual specialized supportive and educational services. Communities are exploring innovative ways to provide in‐person education and specialized services. Also, increased substance use and family violence are emerging as the pandemic continues (Bradbury‐Jones & Isham, 2020). Primary care based health and mental health clinicians can touch base periodically with families at known risk and provide some measure of prevention and early intervention.

Different geographic regions vary in their approach to transition (re‐entry) from the initial crisis phase/wave to a more protracted phase for living with ongoing COVID‐19 risk. State‐by‐state stages of re‐entry are akin to recovery and rehabilitation from an illness, where “vital signs” are monitored to guide timing of graduation to the next stage of recovery or retreat to a previous one. These larger system rules and recommendations inform and guide families. It is essential for families to discuss this step‐wise transition as newer longer‐haul COVID‐19 guidelines become available. Families need to consider how these guidelines fit with their own beliefs and priorities. Distinctions for members at different ages (e.g., children, elders) warrant discussion. Again, consultation with a healthcare provider can offer clearer guidance, for instance with decisions about a college student or young adult losing a job and returning home to live with parents.

With the COVID‐19 pandemic, relative risk may wax and wane with the alternation of periods of “flattening the curve” and decline in new cases with periods of resurgence, higher risk, and the need to resume more intensive case suppression/mitigation public health measures. Like relapsing illnesses, communities and families need to maintain some measure of vigilance and preparedness for both, not knowing “if” and “when” a resurgence/flare‐up may occur (Rolland, 2018). Unlike a condition that is always symptomatically present, here families are strained both by the potential fluctuation of transition between COVID‐19 quiescent and resurgence periods and the ongoing uncertainty of when a spike may occur. Good spirits in resuming more normal routines may be dashed by a new wave of cases. Hunkering‐down again after a period of greater freedom can be discouraging and anxiety provoking. The psychological shift between these two ways of living is a particularly taxing feature for this pandemic as it is for relapsing chronic illnesses. This fluctuating pattern may exact a huge psychological toll over time. Public health media and primary care based psychoeducation supplemented by offering periodic individual or family mental health consultation and brief treatment can be beneficial.

Individuals at Risk and Living with COVID‐19 Disease

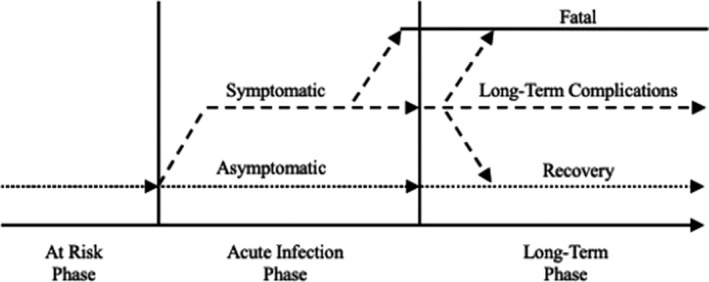

When living with personal risk and actual infection, shown in Figure 3, we can identify three phases: (1) at risk, (2) acute infection, which can be symptomatic (possibly fatal) or asymptomatic, and (3) a long‐term phase that can lead to recovery, may involve complications/chronicity, or can be fatal. Living at risk has been integrated into earlier discussion.

Figure 3.

Covid‐19 Pandemic: Individuals At‐Risk and Disease Timeline.

Acute Infection Phase

If a family member becomes ill with COVID‐19, especially an elder, precautions often require isolation and self‐care without direct caregiving support from family members. In severe life‐threatening situations that require hospitalization, family members are restricted from direct contact with the ill member. And, if the member dies in a hospital or skilled care facility, it is typically without loved ones present. The inability to be there physically for the dying member’s final hours, say goodbye, or have a traditional funeral and burial service can burden family members with myriad complex feelings, such as guilt and anger, that complicate grief reactions.

In one recent case, Bill, who is 70 and in good health, contracted COVID‐19. Six months earlier, he had sought therapy to help him during his wife’s terminal phase with cancer and then with his loss at her death three months before developing COVID‐19. His son, Jim, married with teenage children, lived in another region of the country. After a week of typical symptoms of cough and fever (without COVID‐19 testing), he suddenly developed shortness of breath. Within 24 hours, he was admitted to the ICU and required ventilator support and medical inducement of a coma‐state. Since the fatality rate for this age group once intubated is extremely high, Jim, at a distance was informed of the dire circumstances. Jim has a history of Chron’s disease and ongoing treatment with immune‐suppressants. He was advised not to travel to Chicago because of increased COVID‐19 risks with his chronic illness. Jim went through two agonizing weeks, while his father was on a ventilator. Still grieving for his mother, he was preparing for his father to succumb to an acute, untimely death without family present.

Against the odds, Bill survived and recovered, although with some cardiac complications and slowly resolving mild cognitive issues from the virus. On his return home, I coached Bill and his son via tele‐health therapy to focus initially on his regaining health. As his recovery/rehabilitation progressed, we began the much‐needed processing of his COVID‐19 experience. Bill was saddened, but emotionally very supportive, when hearing about his son’s anxieties and suffering while he was in a coma. This included Jim’s anguish at not being with his father, when he was so close to death. Bill and Jim resumed sharing their grief over the loss of their spouse/mother. In individual sessions, Bill began to think through the next phase of his life. Amidst profound grief over their loss and Bill’s near‐death from COVID‐19, both expressed a feeling of being fortunate to be alive and dedicating themselves to “pay it forward.” This family meaning‐making process was essential to their emotional recovery.

Long‐term phase

With the COVID‐19 disease, the long‐term phase for affected individuals and their families is influenced by an emerging wide range of complications and may be marked by constancy, progression, or episodic change. It is “the longer haul,” involving day‐to‐day living with a potentially chronic condition and associated disruptions in lives and livelihood. Salient family issues include (1) pacing and avoiding burnout; (2) minimizing relationship imbalances between the affected individual and other family members; (3) maximizing autonomy and preserving or redefining individual and family developmental goals within the constraints of COVID‐19; and (4) sustaining connectedness in the face of threatened loss (Rolland, 1990, 2018).

Life Course Developmental and Multigenerational Considerations

All major life course milestones and nodal events are impacted (Rolland, 2016, 2018). COVID‐19 risk has put a threatening cloud on the horizon of any event where family, friends, and community networks would gather. This includes weddings, graduations, funerals and memorial services, family reunions, annual holiday or vacation traditions, and regular gatherings of community groups or religious congregations. Improvisation and creative adapting of events and rituals are key responses fostering family and community resilience (Imber‐Black, 2019). By example, one of our Center trainees’ wedding plans was modified to include only ten individuals present for the actual ceremony in their backyard, while other family and friends joined the ceremony via Zoom. This adaptive response allowed family members, who live at a distance to join the celebration. While there are a number of important individual and family developmental phases, this discussion will highlight several especially salient ones.

Later Life

Those over 65 and/or with a chronic illness (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, obesity, respiratory conditions, immune system compromise) are at much higher risk with more stringent and ongoing restrictions. Many families have organized to protect elders and members with chronic conditions, such as limit entering their home or having close range contact. The lack of physical contact, such as hugging, is particularly difficult, contributing to feelings of isolation and disconnection (Killgore, Cloonan, Taylor, & Dailey, 2020).

With all older clients and those with chronic illness, it is important for clinicians to encourage them to have updated advance directives, a healthcare proxy, and wills. With life‐threatening conditions, like COVID‐19, that can involve rapid progression, unresponsive state, or leave cognitive impairment, there is added incentive for preventive or early frank conversations. Knowing family members’ wishes concerning heroic medical efforts and life support can benefit everyone. Despite the short‐run challenge of having end‐of‐life discussions, it is important to keep in mind that many of the most wrenching end‐of‐life experiences for families occur when the wishes of a dying member are unknown or have been disregarded. Since family members are typically not allowed to be present in the hospital with COVID‐19, it is particularly important that a healthcare proxy has been designated and identified to the healthcare team (Rolland, Emanuel, & Torke, 2017). The proxy can be proactive regarding limits of heroic measures or other important cultural and religious preferences. And, the healthcare team benefits in knowing whom to contact in dire circumstances, where urgent life and death decisions may be necessary.

Early Adulthood

With colleges managing remotely on‐line and unemployment staggering among younger adults, future plans are impacted and some put indefinitely on hold. For financial reasons, many young adults are returning home to live with their families‐of‐origin concurrent with increased economic hardships at home. COVID‐19 anxieties, pandemic fatigue, and evolving public health restrictions, along with economic and cohabiting stresses can easily lead to or heighten family tensions. Regular family “check‐in” meetings can help manage these inevitable strains. COVID‐19 and its economic fallout are causing young adults to encounter huge uncertainties about future hopes and dreams. This may be a significant undercurrent strain for adolescents, young adults, and their parents that can benefit from open discussion.

Multigenerational Considerations

It is worthwhile to ask individuals and family members about prior illness or life crisis/adversity experiences that they can draw on when facing the COVID‐19 pandemic. Areas of vulnerability and resilience are important to identify. For instance, a family history of an untimely illness or death by infection, the succumbing of a robust family member, or a family member suffering alone, can signify particular sensitivity in the context of COVID‐19. A past experience of enduring well prolonged adversity (e.g., poverty) or an illness with high risk and uncertainty (e.g., heart disease) can inspire resilience in the face of COVID‐19.

Healthcare Provider Considerations

As the COVID‐19 pandemic continues, the enormous toll on frontline healthcare workers is emerging as exhaustion, anxiety, depression, insomnia, trauma, and suicide (Schechter et al., 2020; Wong et al., 2020). This toll profoundly and severely impacts their own family relationships. At times, the relentless and largely untreatable nature of COVID‐19 confronts the core identity of healthcare professionals to save and cure patients. Although healthcare providers often make decisions amid uncertainty, “We typically focus on the patient’s risk, not our own. In an infectious disease epidemic, our calculus must incorporate our own exposure risk—and how exposure would limit our ability to care for future patients” (Rosenbaum, 2020). The sense of helplessness and witnessing waves of death is deeply and cumulatively disturbing and can lead to a sense of failure and moral injury (Griffin et al., 2019). This has been compounded by restrictions barring patients’ family members’ physical presence to provide comfort as their loved one’s life is threatened and often in their final hours. This leaves clinicians aware that they may be the last person that the COVID‐19 patient interacts with. As one anesthesiologist put it, “I could be the last person some of these patients ever see, or the last voice they hear. A lot of people will never come off the ventilator. That’s the reality of this virus. I force myself to think about that for a few seconds each time I walk into the ICU to do an intubation” (Saslow, 2020).

Working with illness and loss typically stimulates concerns related to our own and our loved ones’ physical vulnerability and mortality. This is especially true with COVID‐19, where we are all at risk. A we‐they mind‐set is impossible. There is an enormous need for debriefing with colleagues and the availability of individual and family mental health consultations.

Conclusion

A multisystemic lens and drawing on the Family Systems‐Illness model can provide a psychosocial map to guide individuals, couples, and families meet the myriad challenges of COVID‐19. As a worldwide crisis, the COVID‐19 pandemic gives us a sense of belonging that can promote solidarity and increase global empathy and caring for each other.

I wish to acknowledge Danielle Boisvert, Brandon Liu, Carolina Oliveira, Margaret Peterson, and Froma Walsh for their valuable input with the manuscript.

References

- Amsalem, D. , Dixon, L. B. , & Neria, Y. (2020). The Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) outbreak and mental health: Current risks and recommended actions. JAMA Psychiatry. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aronson, L. (2020, June 8). For older people, despair, as well as Covid‐19, is costing lives. The New York Times. Retrieved June 22, 2020, from http://www.nytimes.com. [Google Scholar]

- Bartel, A. P. , Kim, S. , Nam, J. , Rossin‐Slater, M. , Ruhm, C. , & Waldfogel, J. (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: Evidence from four nationally representative datasets. Monthly Labor Review, 1–29. 10.21916/mlr.2019.2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bolin, B. , & Kurtz, L. C. (2018). Race, class, ethnicity, and disaster vulnerability. In Rodríguez H., Donner W. & Trainor J. (Eds.), Handbook of disaster research. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Cham, Switzerland: Springer.181–203. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury‐Jones, C. , & Isham, L. (2020). The pandemic paradox: The consequences of COVID‐19 on domestic violence. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29, 2047–2949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Census Bureau & Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics (2020). https://data.cms.gov/Covid19‐nursing‐home‐data

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2020). COVID‐19 in racial and ethnic minority groups. (2020, June 04). Retrieved June 15, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019‐ncov/community/health‐equity/race‐ethnicity.html. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . Characteristics of persons who died with COVID‐19 ‐ United States, February 12 ‐ May 18, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6928e1.htm. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Cunningham, T. J. , Croft, J. B. , Liu, Y. , Lu, H. , Eke, P. I. , & Giles, W. H. (2017). Vital signs: Racial disparities in age‐specific mortality among blacks or African Americans—United States, 1999–2015. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(17), 444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Adamo, H. , Yoshikawa, T. , & Ouslander, J. G. (2020). Coronavirus disease 2019 in geriatrics and long‐term care: the ABCDs of COVID‐19. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 68(5), 912–917. 10.1111/jgs.16445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton, L. , Rapa, E. , & Stein, A. (2020). Protecting the psychological health of children through effective communication about COVID‐19. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(5), 346–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fauci, A. (2020, June 23). U.S. house of representatives energy and commerce committee hearing on oversight of the trump administration’s response to the COVID‐19 pandemic. Testimony. [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer, R. A. , & Klein, W. M. P. (2015). Risk perceptions and health behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 5, 85–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, B. , Purcell, N. , Burkman, K. , Litz, B. , Bryan, C. , Schmitz, M. et al. (2019). Moral injury: An integrative review. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(3), 350–362. 10.1002/jts.22362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grose, J. (2020, May 27). When couples fight about virus risks. Retrieved June 24, 2020, from http://www.nytimes.com. [Google Scholar]

- Himmelstein, D. , Thorne, D. , Warren, E. , & Woolhandler, S. (2009). Medical bankruptcy in the United States, 2007: Results of a national study. The American Journal of Medicine, 122, 741–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imber‐Black, E. (2019). Rituals in contemporary couple and family therapy. In Fiese B. H., Celano M., Deater‐Deckard K., Jouriles E. N. & Whisman M. A. (Eds.), APA handbooks in psychology®. APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Family therapy and training (pp. 239–253). American Psychological Association. 10.1037/0000101-015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Killgore, W. D. S. , Cloonan, S. A. , Taylor, E. C. , & Dailey, N. S. (2020). Loneliness: A signature mental health concern in the era of COVID‐19. Psychiatry Research, 290, 113117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudsen‐Martin, C. (2012). Changing gender norms in families and society. In Walsh F. (Ed.), Normal family processes, (4th ed., pp. 324–346). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Long, B. , Brady, W. , Koyfman, A. , & Gottlieb, M. (2020). Cardiovascular complications in COVID‐19. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 38(7), 1504–1507. 10.1016/j.ajem.2020.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttik, M. , Mahrer‐Imhof, R. , Garcia‐Vivar, C. , Brodsgaard, A. , Dieperink, K. , Imhof, L. et al. (2020). The COVID‐19 pandemic: A family affair. Journal of Family Nursing, 26(2), 87–89. 10.1177/1074840720920883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2020). https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/index.htm

- Price‐Haywood, E. , Burton, J. , Fort, D. , & Seoane, L. (2020). Hospitalization and mortality among black patients and white patients with Covid‐19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(26), 2534–2543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbiani, D. F. , Gaebler, C. , Muecksch, F. , Lorenzi, J. C. C. , Wang, Z. , Cho, A. et al. (2020). Convergent antibody responses to SARS‐CoV‐2 in convalescent individuals. Nature, 10.1038/s41586-020-2456-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, J. S. (1990). Anticipatory loss: A family systems developmental framework. Family Process, 29(3), 229–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, J. S. (2016). Chronic illness and the family life cycle. In McGoldrick M., Garcia‐Preto N. & Carter E. (Eds.), The expanded family life cycle: Family and social perspectives (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, J. S. (2018). Helping couples and families navigate illness and disability: An integrated Approach. New York: Guilford Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, J. S. (2019). The family, chronic illness, and disability: An integrated practice model. In Fiese B., Celano M., Deater‐Deckard K., Jouriles E. & Whisman M. (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology (Vol. 2,pp). APA Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland, J. S. , Emanuel, L. , & Torke, A. (2017). Applying a family systems lens to proxy decision making in clinical practice and research. Family Systems & Health, 35(1), 7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum, L. (2020). The untold toll – The pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid‐19. New England Journal of Medicine, 382(24), 2368–2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saslow, E. (2020, April 5). Voices from the pandemic. The Washington Post. Retrieved June 21, 2020, from http://www.washingtonpost.com. [Google Scholar]

- Schechter, A. , Diaz, F. , Moise, N. , Anstey, D. E. , Ye, S. , Agarwal, S. et al. (2020). Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during COVID‐19 pandemic. General Hospital Psychiatry, 66, 1–8. 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varatharaj, A. , Thomas, N. , Ellul, M. A. , Davies, N. W. S. , Pollak, T. A. , Tenorio, E. L. et al. (2020, published: June 25). Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID‐19 in 153 patients: A UK‐wide surveillance study. The Lancet Psychiatry. 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30287-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh, F. (2016). Strengthening family resilience (3rd ed.). New York: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wanga, C. , Pana, R. , Wana, X. , Tana, Y. , Xua, L. , McIntyre, R. et al. (2020). A longitudinal study on the mental health of general population during the COVID‐19 epidemic in China. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 87, 40–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong, A. , Pacella‐LaBarbara, M. , Ray, J. , Ranney, M. , & Chang, B. (2020). Healing the healer: Emergency health care workers’ mental health during COVID‐19. Annals of Emergency Medicine. 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2020.04.041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]