Abstract

To systematically analyze the blood coagulation features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) patients to provide a reference for clinical practice. An electronic search in PubMed, EMbase, Web of Science, Scopus, CNKI, WanFang Data, and VIP databases to identify studies describing the blood coagulation features of COVID‐19 patients from 1 January 2020 to 21 April 2020. Three reviewers independently screened literature, extracted data, and assessed the risk of bias of included studies, then, the meta‐analysis was performed by using Stata 12.0 software. Thirty‐four studies involving 6492 COVID‐19 patients were included. Meta‐analysis showed that patients with severe disease showed significantly lower platelet count (weighted mean differences [WMD]: −16.29 × 109/L; 95% confidence interval [CI]: −25.34 to −7.23) and shorter activated partial thromboplastin time (WMD: −0.81 seconds; 95% CI: −1.94 to 0.33) but higher D‐dimer levels (WMD: 0.44 μg/mL; 95% CI: 0.29‐0.58), higher fibrinogen levels (WMD: 0.51 g/L; 95% CI: 0.33‐0.69) and longer prothrombin time (PT; WMD: 0.65 seconds; 95% CI: 0.44‐0.86). Patients who died showed significantly higher D‐dimer levels (WMD: 6.58 μg/mL; 95% CI: 3.59‐9.57), longer PT (WMD: 1.27 seconds; 95% CI: 0.49‐2.06) and lower platelet count (WMD: −39.73 × 109/L; 95% CI: −61.99 to −17.45) than patients who survived. Coagulation dysfunction is common in severe COVID‐19 patients and it is associated with severity of COVID‐19.

Keywords: coagulation dysfunction, coronavirus disease 2019, critically ill, meta‐analysis, severe disease

Highlights

-

1.

Covid‐19 is a new respiratory disease and it has spread rapidly around the world.

-

2.

Coagulation dysfunction is associated with severity of COVID‐19.

-

3.

Monitoring blood coagulation parameters during course of the disease may be helpful for the early identification of severe COVID‐19 patients.

1. INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) has spread rapidly around the world since its emergence in humans last December. 1 , 2 According to data released by World Health Organization (WHO), as of 02:00 on 24 April, there have been 2 626 321 confirmed cases of COVID‐19 patients including 181 938 deaths worldwide, with a fatality rate of approximately 6.93%. 2

According to a study conducted by Dr Chen et al, 3 36% of the patients showed an elevated levels of D‐dimer, 16% showed a reduced activated partial thromboplastin time (APTT), and 30% showed a shortened prothrombin time (PT). Besides, Wang et al 4 conducted a retrospective study of 339 COVID‐19 patients, including 80 critical and 159 severe cases. Their results showed that the PT was significantly prolonged, and D‐dimer levels were evidently elevated in the death group. Another study by Professor Tang, found that the nonsurvivors COVID‐19 patients revealed significantly higher levels of D‐dimer and FDP, longer PT, and APTT compared to survivors group on admission. 5 Elevated levels of D‐dimer are an independent risk factors for acute respiratory distress syndrome and mortality in COVID‐19 patients. 6

Although the above studies have shown that COVID‐19 has been linked to coagulation dysfunction, most of them were single‐center studies that were conducted in a specific hospital or region. Due to differences in study design and small samples, the key outcomes of these studies are complicated and unclear. A meta‐analysis of nine studies suggested that COVID‐19 involves longer PT and elevated D‐dimer levels, 7 yet several large clinical studies of the disease have been conducted since then and have reported inconsistent findings about coagulation dysfunction. 8 , 9 , 10 Therefore, we meta‐analyzed the blood coagulation features of COVID‐19 patients to provide a reference for clinical decisions and future research.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Search strategy

This meta‐analysis was carried out according to Preferred Reporting Items for Meta‐Analyzes of Observational Studies in Epidemiology Statement. 11 The databases PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, Chinese National Knowledge Infrastructure, WanFang, and China Science and Technology Journal Database were systematically searched for studies published from 1 January 2020 to 21 April 2020 without language limits. We also manually searched the lists of included studies to identify additional potentially eligible studies. If there were two or more studies described the same population, only the study with the largest sample size was chosen. There was no language restriction placed in the literature search, but only literature published online was included. The following keywords were used, both separately and in combination, as part of the search strategy in each database: “Coronavirus,” “2019‐nCoV,” “COVID‐19,” “SARS‐CoV‐2,” “D‐dimer,” “platelet,” “coagulation function,” “blood clotting,” “coagulation,” “activated partial thromboplastin time,” “fibrinogen,” or “prothrombin time.”

2.2. Study eligibility

Studies were included in the meta‐analysis if they met the following criteria: (a) if they had cohort, case‐control, or case series designs involving more than 40 patients with confirmed COVID‐19; (b) if they reported sufficient details about blood coagulation parameters; (c) the diagnosis and severity classification were based on the New Coronavirus Pneumonia Prevention and Control Program in China or WHO interim guideline, and patients were grouped into different types such as mild, moderate, severe, and critical pneumonia; (d) the coagulation parameters of the COVID‐19 patients were the findings when they were admitted to the hospital or first visited the hospital without the use of anticoagulant prophylaxis or treatment, disease severity classification was done at the end of the follow‐up.

2.3. Data extraction and quality assessment

Three reviewers independently selected literature, extracted data to an Excel database. And any disagreement was resolved by another reviewer. When required, the authors were contacted directly to obtain further information and clarifications regarding their study. Data extraction included the first author's surname and the date of publication of the article, study design, sample size, age, outcome measurement data; relevant elements of bias risk assessment.

The quality of included studies was independently evaluated by the three reviewers based on the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale 12 guidelines. Any disagreement was resolved by another reviewer. This evaluation was conducted based on a set of nine criteria, and studies with a score greater than 6 were considered to be of high quality (total score = 9).

2.4. Statistical analyzes

Data from studies reporting continuous data as ranges or as median and interquartile ranges were converted to mean ± standard deviation. 13 The weighted mean differences (WMDs) in continuous variables between patient groups were calculated, together with the associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs). All meta‐analyzes were performed using STATA 12 (StataCorp, TX). A fixed‐effects model was used when the I 2 statistic was below 50% and the associated P > .10; otherwise, a random‐effects model was used. Funnel plot together with Egger's regression asymmetry test and Begg's test was used to evaluate publication bias. A two‐tailed P < .05 was regarded as statistically significant.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Literature screening and assessment

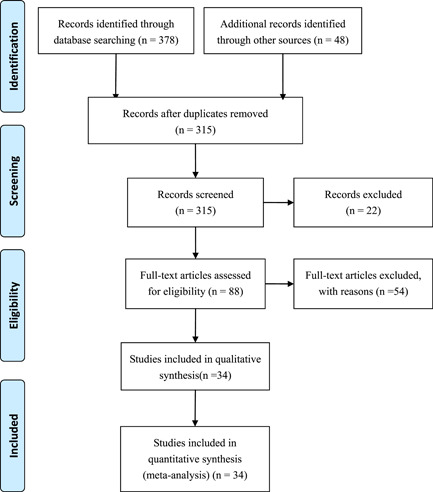

A total of 378 records were identified from the various databases examined. A total of 48 additional records were identified from the Chinese Medical Journal Network. After a detailed assessment based on the inclusion criteria, 34 studies 4 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42 , 43 involving 6492 COVID‐19 patients were included in the meta‐analysis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart depicting literature screening process

3.2. Characteristics of included studies

All studies included in the meta‐analysis were conducted in China and published between 24 January 2020 and 16 April 2020. These retrospective studies examined Chinese patients distributed across 31 provinces. Follow‐up data was reported for most patients. All studies received quality scores varied from 6 to 9 points, indicating high quality (Table 1).

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of included studies of COVID‐19 patients in China

| First author | Publication date in 2020 | n | Single‐ or multicentera | Patient population | Ageb, y | Diagnosis and severity criteriac | Outcomesd | Follow‐up | Quality scoree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yang XB 14 | 24 Feb | 52 | Single center | Survival and nonsurvival COVID‐19 patients | 59.7‐13.3 | WHO interim guideline | ① | 2 Dec 2019 to 9 Feb 2020 | 7 |

| Zhou F 15 | 11 Mar | 191 | Multicenter | Survival and nonsurvival COVID‐19 patients | 56 (46‐67) | WHO interim guideline | ①②③ | Dec 2019 to 31 Jan 2020 | 8 |

| Wang Y 16 | 8 Apr | 344 | Single center | Survival and nonsurvival COVID‐19 patients | 52‐72 | WHO interim guideline | ①②③ | 25 Feb to 25 Feb | 7 |

| An W 17 | 16 Apr | 110 | Single center | Survival and nonsurvival COVID‐19 patients | 72.4/54.6 | Current trail version | ②③⑤ | 24 Jan to 19 Feb | 6 |

| Wang L 4 | 30 Mar | 339 | Single center | Survival and nonsurvival COVID‐19 patients | 69 (65‐76) | Trial sixth Edition | ①②③⑤ | 1 Jan to 5 Mar | 8 |

| Ruan QR 18 | 6 Apr | 150 | Multicenter | Survival and nonsurvival COVID‐19 patients | 67 (15‐81)/50 (44‐81) | Survival and nonsurvival | ① | NR | 7 |

| Tu WJ 19 | 6 Apr | 174 | Single center | Survival and nonsurvival COVID‐19 patients | 64‐80 | Survival and nonsurvival | ② | 3 Jan to 24 Feb | 6 |

| Liu W 20 | 28 Feb | 79 | Multicenter | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 38 (33, 57) | Trial fourth Edition | ①② | 30 Dec 2019 to 15 Jan 2020 | 7 |

| Shi JH 21 | 12 Mar | 54 | Single center | Mild, severe, and critically ill COVID‐19 patients | 62.5 (50.5, 68.5) | Trial sixth Edition | ② | 9 Feb to 29 Feb | 6 |

| Cheng KB 22 | 12 Mar | 463 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 15‐90 | Trial fifth Edition | ① | Dec 2019 to 06 Feb 2020 | 7 |

| Wang D 23 | 08 Feb | 138 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 56 (42‐68) | WHO interim guideline | ①②③⑤ | 1 Jan to 28 Jan | 7 |

| Yuan J 24 | 06 Mar | 223 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 46.5 ± 16 | Trial sixth Edition | ①② | 24 Jan to 23 Feb | 9 |

| Fang XW 25 | 25 Feb | 79 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 45 ± 16.6 | Trial sixth Edition | ①②③⑤ | 22 Jan to 18 Feb | 6 |

| Guan W 26 | 06 Feb | 1099 | Multicenter | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 47.0 | WHO interim guideline | ① | NR | 9 |

| Qian GQ 27 | 17 Mar | 88 | Multicenter | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 50 (36.5‐57) | WHO interim guideline | ①②④ | 20 Jan to 11 Feb | 9 |

| Huang CL 28 | 15 Feb | 41 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 49 (41‐58) | WHO interim guideline | ①②③⑤ | Dec 2019 to 2 Jan 2020 | 7 |

| Wan SX 29 | 21 Mar | 135 | Retrospective | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 47 (36‐55) | WHO interim guideline | ①②③⑤ | 23 Jan to 8 Feb | 8 |

| Gao Y 30 | 17 Mar | 43 | Retrospective | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 45 ± 7.7/43 ± 14 | WHO interim guideline | ②③⑤ | 23 Jan to 2 Feb | 6 |

| Zhang JJ 31 | 23 Feb | 140 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 57.0 | trail version 3‐5 | ② | 16 Jan to 3 Feb | 7 |

| Li D 32 | 26 Mar | 80 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 47.8 ± 19.5 | Trial fifth Edition | ①②③ | 20 Jan to 27 Feb | 7 |

| Li D 33 | 2 Apr | 62 | Single center | Mild, severe, and critically ill COVID‐19 patients | 49 ± 37/59 ± 31 | Trial sixth Edition | ① | 31 Jan to 25 Feb | 6 |

| Zhang W 34 | 2 Apr | 74 | Single center | Mild, Severe, and critically ill COVID‐19 patients | 52.7 ± 19 | Trial sixth Edition | ①③ | 21 Jan to 11 Feb | 7 |

| Xiong J 35 | 03 Mar | 89 | Single center | Mild, severe, and critically ill COVID‐19 patients | 53 ± 16.9 | Trial sixth Edition | ① | 17 Jan to 20 Feb | 7 |

| Xie HS 36 | 2 Apr | 79 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 60 (48‐66) | Trial sixth Edition | ② | 2 Feb to 23 Feb | 7 |

| Peng YD 37 | 2 Mar | 112 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 62 (55, 67) | Trial sixth Edition | ③⑤ | 20 Jan to 15 Feb | 7 |

| Ling Y 38 | 18 Mar | 292 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 48.7 ± 16/65.5 ± 16 | Trial fifth Edition | ②④ | 20 Jan to 10 Feb | 9 |

| Zhan TT 39 | 7 Apr | 40 | Single center | Mild, severe, and critically ill COVID‐19 patients | 25‐90 | Trial sixth Edition | ① | 20 Jan to 20 Feb | 6 |

| Liu SJ 40 | 2 Apr | 342 | Single center | Mild, severe, and critically ill COVID‐19 patients | 1‐88 | Trial sixth Edition | ①②④ | 23 Jan to 12 Feb | 7 |

| Zuo FT 41 | 14 Apr | 50 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 48.2 ± 15.3 | Trial fifth Edition | ①③④⑤ | 19 Jan to 20 Mar | 6 |

| Feng Y 8 | 10 Apr | 476 | Multicenter | Mild, severe, and critically ill COVID‐19 patients | 53 (40‐64) | Trial fifth Edition | ①②④ | 1 Jan to 21 Mar | 8 |

| Cai QX 42 | 2 Apr | 298 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 47.5 (33‐61) | WHO interim guideline | ② | 11 Jan to 6 Mar | 7 |

| Zheng F 43 | Mar | 161 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 45 (33.5, 57) | Trial fifth Edition | ① | 17 Jan to 7 Feb | 6 |

| Chen X 9 | 10 Apr | 296 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | NR | Trial sixth Edition | ①② | 27 Jan to 15 Feb | 8 |

| Zheng YL 10 | 10 Apr | 99 | Single center | Mild and severe COVID‐19 patients | 49.4 ± 18.45 | Trial fifth Edition | ②③ | 16 Jan to 23 Feb | 8 |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; WHO, World Health Organization.

All studies were retrospective.

Reported as range, mean ± SD, or median (interquartile range). NR, not reported.

Version of New Coronavirus Pneumonia Prevention and Control Program in China, or WHO interim guideline.

① Platelet count, ② D‐dimer level, ③ prothrombin time,④ fibrinogen level,⑤ activated partial thromboplastin time.

Score on the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale guidelines. 12

3.3. Meta‐analysis results

3.3.1. Coagulation parameters

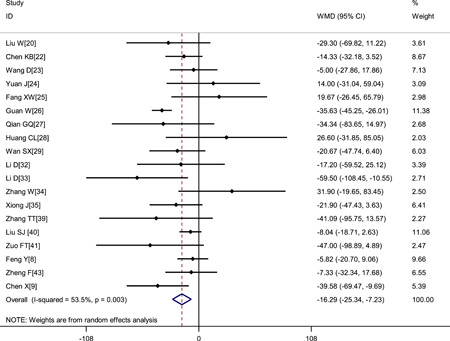

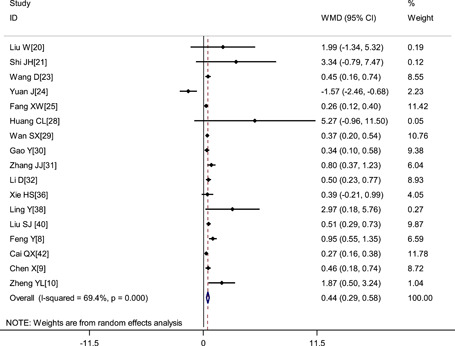

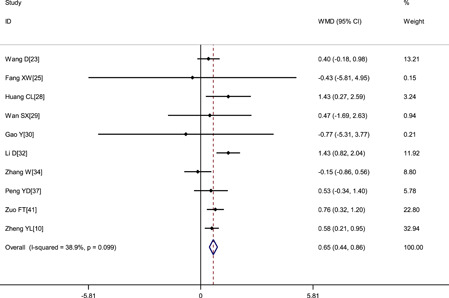

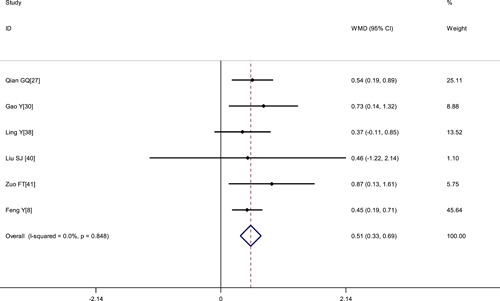

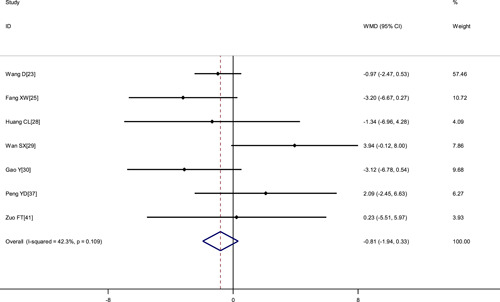

Pooled results revealed that patients with severe disease showed significantly lower platelet count (WMD: −16.29 × 109/L; 95% CI: −25.34 to −7.23) and shorter APTT (WMD: −0.81 seconds; 95% CI: −1.94 to 0.33) but higher D‐dimer level (WMD: 0.44 μg/mL; 95% CI: 0.29‐0.58), higher fibrinogen level (WMD: 0.51 g/L; 95% CI: 0.33‐0.69) and longer PT (WMD: 0.65 seconds; 95% CI: 0.44‐0.86) (Figures 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and Table 2).

Figure 2.

Meta‐analysis of platelet count (×109/L) between COVID‐19 patients with mild or severe disease. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; WMD, weighted mean difference

Figure 3.

Meta‐analysis of D‐dimer (μg/mL) between COVID‐19 patients with mild or severe disease. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; WMD, weighted mean difference

Figure 4.

Meta‐analysis of the prothrombin time (s) between COVID‐19 patients with mild or severe disease. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; WMD, weighted mean difference

Figure 5.

Meta‐analysis of the FIB (g/L) between COVID‐19 patients with mild or severe disease. COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; WMD, weighted mean difference

Figure 6.

Meta‐analysis of APTT (s) between COVID‐19 patients with mild or severe disease. APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019; WMD, weighted mean difference

Table 2.

Meta‐analysis of different blood coagulation parameters in COVID‐19 patients

| Parameter | No. of studies | No. of patients | Heterogeneity | Model | Meta‐analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | I 2 | WMD (95%CI) | P | ||||

| Mild vs severe disease | |||||||

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 19 | 4027 | .003 | 53.5% | Random | −16.29 (−25.34, −7.23) | <.001 |

| D‐dimer level, μg/mL | 17 | 2903 | <.001 | 69.4% | Random | 0.44 (0.29, 0.58) | <.001 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 10 | 851 | .099 | 38.9% | Fixed | 0.65 (0.44, 0.86) | <.001 |

| Fibrinogen level, g/L | 6 | 1304 | .848 | 0.0% | Fixed | 0.51 (0.33, 0.69) | <.001 |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time, s | 7 | 598 | .109 | 42.3% | Fixed | −0.81 (−1.94, 0.33) | <.001 |

| Death vs survival | |||||||

| Platelet count, ×109/L | 5 | 1076 | .003 | 74.9% | Random | −39.73 (−61.99, −17.45) | <.001 |

| D‐dimer level, μg/mL | 5 | 1258 | .001 | 79.6% | Random | 6.58 (3.59, 9.57) | .001 |

| Prothrombin time, s | 4 | 984 | .012 | 72.7% | Random | 1.27 (0.49, 2.06) | .001 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; WMD, weighted mean difference.

Another analysis of seven studies 4 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 whose primary outcome was death. The results showed that patients who died showed significantly higher D‐dimer levels (WMD: 6.58 μg/mL, 95% CI: 3.59‐9.57), longer PT (WMD: 1.27 seconds; 95% CI: 0.49‐2.06) and lower platelet count (WMD: −39.73 × 109/L; 95% CI: −61.99 to −17.45) (Table 2).

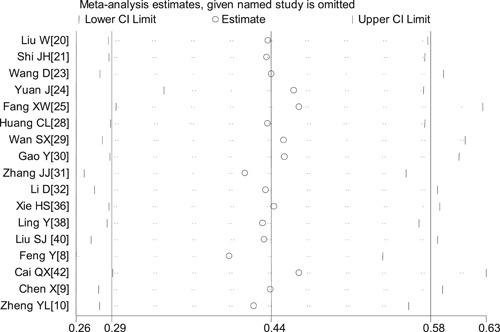

3.3.2. Sensitivity analysis

There was heterogeneity in the pooled results of the platelet count and D‐dimer. To determine sensitivity, the meta‐analyzes of platelet count and D‐dimer levels from all included studies were repeated after omitting each study in turn, and the results were similar to those obtained with the entire dataset, indicating the reliability and stability of our meta‐analysis (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Sensitivity analysis of D‐dimer levels between COVID‐19 patients with mild or severe disease.COVID‐19, coronavirus disease 2019

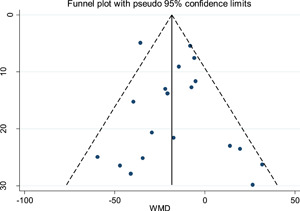

3.4. Publication bias

A funnel plot based on the outcome of platelet count showed the P values of Egger's test and Begg's test were .516 and .529 respectively, suggesting no significant risk of publication bias (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Funnel plot of platelet count data from all included studies

4. DISCUSSION

Previous studies have shown that COVID‐19 infection has been linked to coagulation dysfunction and coagulopathy appears to be related to severity of illness and resultant thromboinflammation which may increase risk of associated mortality. 23 , 44 , 45 This suggested that monitoring blood coagulation parameters during course of the disease may be helpful for the early identification of severe COVID‐19 patients, which is essential for healthcare providers in their efforts to treat patients and contain the current outbreak.

Compared to the nine studies involving 1105 patients in the most recent relevant meta‐analysis, 7 the present work includes 34 studies published up to 21 April 2020 and a total pooled population of 6492 COVID‐19 patients. Our results indicate that low platelet count, elevated D‐dimer levels, and prolonged PT occur more often in severe than mild COVID‐19, and they occur more often in patients who die from the disease than in those who survive. Consistent with this, individual studies have reported that COVID‐19 patients in the intensive care unit have significantly higher coagulation parameters than those of COVID‐19 patients not receiving intensive care, 28 and that more than 70% of patients who die from COVID‐19 meet the criteria of disseminated intravascular coagulation. 5 These findings suggest that monitoring blood coagulation parameters in COVID‐19 patients may aid in early detection of severe disease.

The coronavirus causing COVID‐19 may trigger coagulation dysfunction because it induces abundant release of proinflammatory cytokines in various tissues, which can lead to systemic inflammatory response syndrome that damages the microvascular system and thereby activates the coagulation system, leading to generalized small vessel vasculitis, and extensive microthrombosis. 46 , 47 In particular, patients with severe COVID‐19 may be at high risk of venous thromboembolism, which may be present in up to 25% of such patients. 48 Indeed, a study of 1099 patients across China suggests that 40% of all COVID‐19 patients may be at high risk of venous thromboembolism. 49 Risk may be exacerbated by the dehydration due to fever and diarrhea, hypotension, and prolonged bed rest characteristic of the disease, all of which are risk factors for coagulation in their own right, 50 as well as by the use of vasopressors and central venous catheters in the intensive care unit. 51 This has led to the recommendation that patients with severe COVID‐19 should be carefully monitored for coagulation function and given prophylactic anticoagulant therapy in the absence of anticoagulant contraindications. 47 Dr Connors et al also reported that the use of an increased prophylactic dose of nadroparin resulted in a significant decrease in D‐dimer levels. 52

Although this study rigorously analyzed coagulation parameters data collected from a large sample of COVID‐19 patients, we were unable to eliminate the heterogeneity observed between studies. For example, the course and the severity of the disease varied across studies. Given that most of the studies included in our meta‐analysis were single‐center, retrospective studies, it was difficult for us to control for the effects of several confounding factors, including bias in patient admission and selection, as well as differences in disease severity and course. Further research is needed to verify and extend our results.

5. CONCLUSION

In summary, current evidence showed that coagulation dysfunction is common in severe COVID‐19 patients, and it is associated with severity of COVID‐19. And thus could be used as early warning indicators of disease progression during hospitalization.

CONFLICT OF INTERESTS

The authors declare that there are no conflict of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Pan Ji, Hongyuan Li, Zhimei Zhong, and Bocheng Li collected and analyzed the data. Jianfeng Zhang acquired the funding. Jieyun Zhu and Jielong Pang designed the study and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Jianfeng Zhang and Junyu Lu designed and supervised the study and finalized the manuscript, which all authors read and approved.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This study was supported by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81960343; 81660132); the Emergency Science and Technology Brainstorm Project for the Prevention and Control of COVID‐19, which is part of the Guangxi Key Research and Development Plan (GuikeAB20058002) and the High‐level Medical Expert Training Program of Guangxi “139” Plan Funding (G201903027).

Zhu J, Pang J, Ji P, et al. Coagulation dysfunction is associated with severity of COVID‐19: A meta‐analysis. J Med Virol. 2021;93:962–972. 10.1002/jmv.26336

Jieyun Zhu and Jielong Pang contributed equally to this study.

Contributor Information

Jianfeng Zhang, Email: zhangjianfeng@stu.gxmu.edu.cn.

Junyu Lu, Email: junyulu@gxmu.edu.cn.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Walls AC, Park YJ, Tortorici MA, Wall A, McGuire AT, Veesler D. Structure, function, and antigenicity of the SARS‐CoV‐2 spike glycoprotein. Cell. 2020;181:281‐292. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. WHO . Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) Situation Dashboard[Internet]. Available: https://covid19.who.int/. Accessed April 25, 2020.

- 3. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):507‐513. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wang L, He W, Yu X, et al. Coronavirus disease 2019 in elderly patients: characteristics and prognostic factors based on 4‐week follow‐up. J Infect. 2020;80(6):639‐645. 10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang N, Li D, Wang X, Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associatedwith poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844‐847. 10.1111/jth.14768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wu C, Chen X, Cai Y, et al. Risk factors associated withacute respiratory distress syndrome and death in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(7):1‐11. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Xiong M, Liang X. Changes in blood coagulation in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): a meta‐analysis. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(6):1050‐1052. 10.1111/bjh.16725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Feng Y, Ling Y, Bai T, et al. COVID‐19 with different severity: a multi‐centerstudy of clinical features. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201(11):1380‐1388. 10.1164/rccm.202002-0445OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen X, Ou JY, Huang Y, et al. Diagnostic roles of several parameters in corona virus disease 2019. Lab Med. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/31.1915.R.20200410.0956.002.html

- 10. Zheng Y, Xu H, Yang M, et al. Epidemiological characteristics and clinical features of 32 critical and 67 noncritical cases of COVID‐19 in Chengdu. J Clin Virol. 2020;127:104366. 10.1016/j.jcv.2020.104366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, et al. Meta‐analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008‐2012. 10.1001/jama.283.15.2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Stang A. Critical evaluation of the Newcastle‐Ottawa scale for the assessment ofthe quality of nonrandomized studies in meta‐analyses. Eur J Epidemiol. 2010;25(9):603‐605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang X, Yu Y, Xu J, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of critically ill patientswithSARS‐CoV‐2 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a single‐centered, retrospective, observational study. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(5):475‐481. 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30079-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Zhou F, Yu T, Du R, et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID‐19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;03(28):1054‐1062. 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wang Y, Lu X, Li Y, et al. Clinical course and outcomes of 344 intensive care patients with COVID‐19. Am J Respir Criti Care Med. 2020;201(11):1430‐1434. 10.1164/rccm.202003-0736LE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. An W, Xia F, Chen M, et al. Analysis of clinical features of 11 death cases caused by COVID⁃19. The Journal of Practical Medcine. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/44.1193.r.20200414.1620.007.html

- 18. Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID‐19based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive CareMed. 2020;46(5):846‐848. 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tu WJ, Cao J, Yu L, Hu X, Liu Q. Clinicolaboratory study of 25 fatal cases of COVID‐19 in Wuhan. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1117‐1120. 10.1007/s00134-020-06023-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu W, Tao ZW, Wang L, et al. Analysis of factors associated with disease outcomes inhospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus disease. Chin Med J. 2020;133(9):1032‐1038. 10.1097/CM9.0000000000000775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Shi JH, Wang YR, Li WB, et al. Digestive system manifestations and analysis ofdisease severity in 54 patients with corona virus disease 2019. Chin J Dig. 2020;40(03):167‐170. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-1432.2020.0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Cheng KB, Wei M, Shen H, et al. Clinical characteristics of 463 patients with common and severe type coronavirus disease 2019. Shanghai Medical Journal. 2020;43(04):224‐232. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/31.1366.r.20200312.1254.004.html [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus‐infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061‐1069. 10.1001/jama.2020.1585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Yuan J, Sun YL, Zuo YJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 223 novel coronaviruspneumonia cases in Chongqing. J Southwest University(Natural Science Edition). 2020;42(03):1‐7. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/50.1189.N.20200305.1429.004.html [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fang XW, Mei Q, Yang TJ, et al. Clinical characteristics and treatment analysis of 79 cases of COVID‐19. Chinese Pharmacological Bulletin. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/34.1086.r.20200224.1340.002.html

- 26. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of 2019 novel coronavirusinfection in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708‐1720. 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Qian GQ, Yang NB, Ding F, et al. Epidemiologic and Clinical Characteristics of91 Hospitalized Patients with COVID‐19 in Zhejiang, China: A retrospective, multi‐centre case series. QJM. pii: hcaa089. 10.1093/qjmed/hcaa089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):497‐506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wan S, Xiang Y, Fang W, et al. Clinical features and treatment of COVID‐19 patients in northeast Chongqing. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):797‐806. 10.1002/jmv.25783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gao Y, Li T, Han M, et al. Diagnostic utility of clinical laboratory data determinationsfor patients with the severe COVID‐19. J Med Virol. 2020;92(7):791‐796. 10.1002/jmv.25770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zhang JJ, Dong X, Cao YY, et al. Clinical characteristics of 140 patients infectedwith SARS‐CoV‐2 in Wuhan, China. Allergy. 10.1111/all.14238 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32. Li D, Long YZ, Huang P, et al. Clinical characteristics of 80 patients with COVID‐19 in Zhuzhou City. Chinese Journal of Infection Control. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/43.1390.R.20200324.1537.004.html

- 33. Li D, Wang ML, He B, et al. Laboratory test analysis of sixty⁃two COVID⁃19 patients. Medical Journal of Wuhan University. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/42.1677.r.20200401.1707.001.html

- 34. Zhang W, Hou W, Li TZ, et al. Clinical characteristics of 74 hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. Journal of Capital Medical University. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/11.3662.r.20200401.1501.006.html

- 35. Xiong J, Jiang WL, Zhou Q, et al. Clinical characteristics, treatment, and prognosis in 89 cases of COVID‐2019. Medical J Wuhan Univ (Health Sciences). 2020;41(04):542‐546. 10.14188/j.1671-8852.2020.0103 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Xie H, Zhao J, Lian N, Lin S, Xie Q, Zhuo H. Clinical characteristics of non‐ICU hospitalized patientswith coronavirus disease 2019 and liver injury: a retrospective study. Liver Int. 2020;40:1321‐1326. 10.1111/liv.14449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Peng YD, Meng K, Guan HQ, et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of 112 cardiovascular disease patients infected by 2019‐nCoV. Chin J Cardiol. 2020;48(06):450‐455. 10.3760/cma.j.cn112148-20200220-00105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ling Y, Lin YX, Qian ZP, et al. Clinical analysis of risk factors for severe patientswith novel coronavirus pneumonia. Chin J Infect. http://rs.yiigle.com/yufabiao/1185115.htm

- 39. Zhang TT, Zheng HP, Mai YZ, et al. The correlation between serological dynamic evolution and the severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Guangdong Medical Journal. 10.13820/j.cnki.gdyx.20200642 [DOI]

- 40. Liu SJ, Cheng F, Yang XY, et al. A study of laboratory confirmed cases between laboratory indexesand clinical classification of 342 cases withCorona Virus Disease 2019 in Ezhou. Laboratory Medicine. http://kns.cnki.net/kcms/detail/31.1915.r.20200401.1647.004.html

- 41. Zuo FT, Li CL, Dong ZG, et al. Analysis of thecorrelation between clinical characteristics and disease severity in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. Tianjin Med J. 2020;5(5):455‐460. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cai Q, Huang D, Ou P, et al. COVID‐19 in a designated infectious diseases hospital outside Hubei Province, China. Allergy. 2020;75(7):1742‐1752. 10.1111/all.14309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zheng F, Tang W, Li H, Huang YX, Xie YL, Zhou ZG. Clinical characteristics of 161 cases of corona virus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Changsha. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci. 2020;24(6):3404‐3410. 10.26355/eurrev_202003_20711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Connors JM. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1559‐1561. 10.1111/jth.14849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Connors JM, Levy JH. COVID‐19 and its implications for thrombosis and anticoagulation. Blood. 2020;135(23):2033‐2040. 10.1182/blood.2020006000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chousterman BG, Swirski FK, Weber GF. Cytokine storm and sepsis disease pathogenesis. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39(5):517‐528. 10.1007/s00281-017-0639-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Song JC, Wang G, Zhang W, et al. Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in COVID‐19. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):19. 10.1186/s40779-020-00247-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Cui S, Chen S, Li X, Liu S, Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemosta. 2020;18(6):1421‐1424. 10.1111/jth.14830 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Wang T, Chen R, Liu C, et al. Attention should be paid to venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in the management of COVID‐19. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7(5):e362‐e363. 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30109-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Zhou B, She J, Wang Y. Venous thrombosis and arteriosclerosis obliterans of lower extremities in a very severe patient with 2019 novel coronavirus disease: a case report. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(1):229‐232. 10.1007/s11239-020-02084-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kollias A, Kyriakoulis KG, Dimakakos E, Poulakou G, Stergiou GS, Syrigos K. Thromboembolic risk and anticoagulant therapy in COVID‐19 patients: emerging evidence and call for action. Br J Haematol. 2020;189(5):846‐847. 10.1111/bjh.16727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Connors JM, Levy JH. Thromboinflammation and the hypercoagulability of COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1559‐1561. 10.1111/jth.14849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.