Abstract

Hypercoagulability is an increasingly recognized complication of SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. As such, anticoagulation has become part and parcel of comprehensive COVID‐19 management. However, several uncertainties exist in this area, including the appropriate type and dose of heparin. In addition, special patient populations, including those with high body mass index and renal impairment, require special consideration. Although the current evidence is still insufficient, we provide a pragmatic approach to anticoagulation in COVID‐19, but stress the need for further trials in this area.

Keywords: anticoagulant, coagulopathy, Covid‐19, D‐dimer, prothrombin time

1. INTRODUCTION

Morbidity and mortality secondary to COVID‐19 is increasing worldwide. Venous thromboembolism (including pulmonary embolism), arterial thrombosis, and microvascular thrombi appear to contribute to adverse outcomes.1., 2. One of the key interventions that appears to be effective in reducing mortality associated with thrombosis in non‐COVID‐19 settings is anticoagulant therapy.3 Accordingly, the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis published an interim guideline that recommended the use of prophylactic anticoagulation with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) in all patients admitted with COVID‐19 in the absence of contraindications.4 With the increasing experience of health care providers in managing COVID‐19 patients, several questions have arisen about the use of anticoagulation that we address in this practice communication. Although possible solutions are suggested, we stress the need for well‐designed randomized studies (performed rapidly) to produce evidence‐based recommendations. The following recommendations are for adult patients only.

2. UNFRACTIONATED HEPARIN OR LOW MOLECULAR WEIGHT HEPARIN?

In the study by Tang et al, a minority of all COVID‐19 patients received LMWH in prophylactic doses, with relatively few given unfractionated heparin (UFH).3 The use of LMWH reflects the evolving practice worldwide toward LMWH becoming the standard of care for the prevention and treatment of thromboembolism versus UFH because of better bioavailability, fixed dosing, decreased risk of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), and osteoporosis.5., 6. However, LMWH can accumulate with renal impairment and has a longer half‐life than UFH.5., 6. Hence, in patients with severe renal impairment, at a high‐risk of bleeding, or the need to undergo invasive procedures, UFH is preferred, which may be particularly relevant in critically ill COVID‐19 patients, in whom coagulopathy is the most severe.

When using UFH, however, numerous variables ranging from preanalytic issues (sample collection and processing), and reagent differences can influence activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) measurements.7 The aPTT may be prolonged in some COVID‐19 patients because of consumptive coagulopathy in the most critically ill and possibly from the presence of a lupus anticoagulant. A recent report implicating antiphospholipid antibodies in COVID‐19 patients with thrombotic events found elevated aPTT levels and presence of anticardiolipin and anti‐β2‐glycoprotein antibodies, although lupus anticoagulant tests were negative.8 Another paper noted 20% of patients had a prolonged aPTT, most of which were due to lupus anticoagulants.9 A French group observed 45% positivity in lupus anticoagulant tests in 56 patients diagnosed with COVID‐19.10 Whether these antibodies are pathogenic and result in thrombosis (including arterial thrombosis) remains to be determined.

One potential concern with the use of UFH in COVID 19 patients is the possible development of heparin resistance in the setting of an acute phase response. In COVID‐19 and other inflammatory states, acute phase reactants, including fibrinogen11 and C‐reactive protein,12 are elevated. It has been shown that increased fibrinogen levels and other heparin‐binding acute‐phase reactants create a prohemostatic environment that can antagonize the anticoagulant effects of heparin, with hyperfibrinogenemia a key factor causing heparin resistance.13 Heparin resistance is defined as the requirement of high doses of UFH (daily dose in excess of 35 000 units/d) to achieve a therapeutic range.14 This phenomenon occurs because of heparin’s ability to bind to various acute‐phase plasma proteins (increased in COVID‐19), as well as macrophages and endothelial cells,15 which are both activated in COVID‐19. Although low antithrombin levels are another potential reason for heparin resistance, moderate to severe decreased antithrombin levels are unusual in COVID‐19 patients, with most patients having plasma levels within the low‐normal range of ~80%.11., 16. However, Ranucci et al did report antithrombin levels <60% in two of 16 patients in their analysis of COVID‐19 critically ill subjects.17 In addition, thrombocytosis, which has been noted in COVID‐19, possibly from excessive thrombopoietin production of the liver, has also been suggested as a reason for heparin resistance.3., 18. A practical solution for “overcoming” heparin resistance is to measure both aPTT and a concomitant anti‐factor Xa heparin level.7 If monitoring is impractical, alternate agents such as longer‐acting, non‐aPTT adjusted subcutaneous fondaparinux or danaparoid may be alternatives if the renal function is normal.19., 20. Prophylactic‐dose LMWH (dalteparin) has been studied in critically ill patients even with markedly impaired renal function without monitoring and no adverse effects.21

3. STANDARD PROPHYLACTIC‐DOSE ANTICOAGULATION?

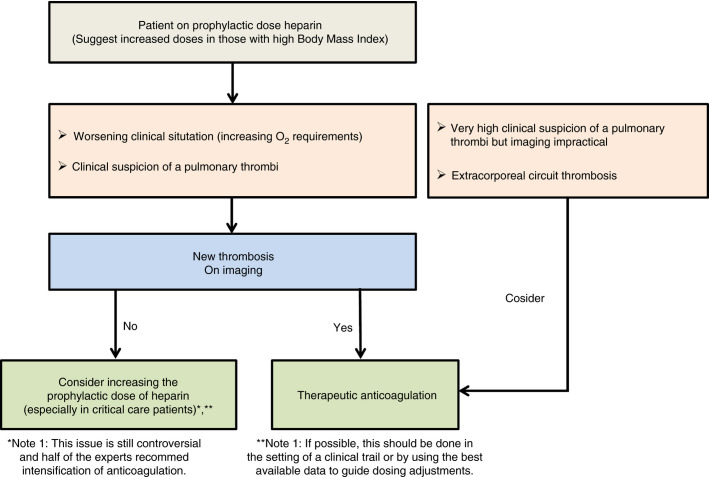

Clinical experience in COVID‐19 suggests there are anticoagulation failures in patients already receiving prophylactic anticoagulation. In a recently published study, despite systematic thromboprophylaxis, 31% of the 184 patients in critical care units with COVID‐19 developed thrombotic complications.2 In an update of this cohort, the cumulative incidence of arterial and venous thromboembolism was 49% (95% confidence interval, 41‐57).22 Other studies have found similarly marked increase in the incidence of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in patients requiring intensive care unit (ICU) care that exceed similarly cared for ICU patients without COVID‐19, including comparison to past influenza patients.23., 24., 25. This could be due to several reasons including (a) COVID‐19‐specific coagulation changes with extensive coagulation activation for which prophylactic dosing may be insufficient, (b) thromboembolism had already developed before starting anticoagulation, or (c) inadequate dosing (high body mass index or inaccurate dosing). In the setting of critically ill patients requiring mechanical ventilation, immobilization can occur from deep sedation and muscle paralysis. Also, the use of high‐pressure ventilation settings resulting in high intrathoracic pressure may impair pulmonary perfusion. Significant controversy has developed regarding an empiric increase in the dose of heparin, especially in the following situations (Figure 1 ):

-

1.

Worsening of the clinical picture manifest as increasing oxygen requirements, which may be due to pulmonary microthrombi

-

2.

Suspicion of pulmonary thromboembolism based on abrupt development of hypoxemia, new tachycardia, and right heart strain seen on echocardiogram. Heightened suspicion should be maintained in ALL patients;

-

3.

Need for ICU care and ventilatory support as the cumulative incidence of VTE in ICU patients has been found to be higher than those not requiring ICU care22., 23., 24.

Figure 1.

Suggested algorithm for anticoagulation in patients with COVID‐19

If imaging can be performed, and there is definite evidence of thrombi, therapeutic anticoagulation should be administered. In those patients for whom pulmonary thromboembolism is highly likely based on clinical findings but imaging is not feasible, an increase to therapeutic‐dose anticoagulation may be appropriate. Therapeutic‐dose anticoagulation in a large cohort of hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 was associated with a reduced risk of mortality (adjusted hazard ratio of 0.86 per day; 95% confidence interval, 0.82‐0.89; P < .001).25 In addition, the higher dose reduced the incidence of mechanically ventilated patients (in‐hospital mortality of 29.1% compared with 62.7% in those who did not receive anticoagulation).25 However, this retrospective review of hospital system data has many limitations, including lack of information on patient selection for therapeutic‐dose anticoagulation, indication for anticoagulation, severity of illness, and other unknown confounding variables. Other centers are using “intermediate‐dose” anticoagulation in patients who have no evidence of VTE but require ICU care based on the increased incidence of VTE despite standard‐dose thromboprophylaxis.22., 23. Although Goyal et al have shown that critically ill patients with COVID‐19 may not have higher incidence of thrombosis compared with other critically ill patients,26 the reports from several different countries are showing a remarkably increased thrombotic risk in these patients and “failure” of standard dose prophylactic anticoagulation. Hence, until trials prove otherwise, the authors suggest an intensification of the prophylactic dose of heparin if patients require critical care support if there are no contraindications. The risk of bleeding under anticoagulation in COVID‐19 patients is summarized in Table 1 .

Table 1.

Bleeding adverse events under anticoagulation in COVID‐19 patients

| Source | Cases or Incidence of Bleeding | Anticoagulation |

|---|---|---|

| Bargellini et al47 | Four consecutive patients with spontaneous bleedings underwent endovascular embolization. | 6000 IU LMWH/12 h or 8000 IU/12 h |

| Carroll et al48 | Two cases of patients developed catastrophic intracranial hemorrhage and cerebral edema. | Anti‐Xa levels: <0.73 and 0.62 IU/mL |

| Al‐Samkari et al49 | Overall and major bleeding rates were 4.8% (19/400 cases) and 2.3% (3/144 cases). | Standard‐dose prophylactic anticoagulation |

If therapeutic anticoagulation with UFH is chosen, the issue of "aPTT confounding" should be considered; this is a situation where an underlying condition (eg, liver impairment, lupus anticoagulant) may cause pretreatment aPTT elevations and patients may have "therapeutic" aPTT values, but where the anticoagulant level is actually subtherapeutic.19

4. EXTRACORPOREAL FILTER CLOTS OR OCCLUSION

Health care providers are noticing in COVID‐19 patients an increase in filter occlusion and thrombosis with extracorporeal circuits including hemofiltration or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, despite routine anticoagulation.27 Contact activation and the complement system are both involved in thrombin generation in patients who require dialysis or extracorporeal membrane oxygen (ECMO).28., 29. Because the inflammatory process is closely linked to both these pathways, intense inflammation in COVID‐19 could predispose to filter clots or occlusion.29., 30. Possible management approaches include administration of higher doses of heparin as well as more accurately assessing the anticoagulant effects of heparin. Additional therapies that may also be considered include complement inhibitors and possibly agents that can inhibit the contact pathway of the coagulation cascade. For patients on ECMO or with continuous veno‐venous hemofiltration, therapeutic anticoagulation may be appropriate if there is evidence of clots in the extracorporeal circuits.

5. PATIENTS WITH RENAL IMPAIRMENT

Abnormalities in renal function are rare at least in the early phases of the COVID‐19 infection.11 But there may be patients who already have known kidney problems or can develop renal impairment secondary to the critical illness or the use of hydroxychloroquine. If the patient is receiving LMWH in treatment doses, the amount should be adjusted based on anti‐Xa measurements to avoid drug accumulation.31 Some experts recommend switching to UFH in this clinical situation, which may be reasonable, but as discussed before, ensuring rapid and adequate anticoagulation is imperative.7 Alternatives to UFH include renally adjusted dose danaparoid, argatroban, or bivalirudin.32

6. SPECIAL PATIENT POPULATION: OBESITY

Obesity with body mass index > 35 in patients with COVID‐19 appears to be a poor prognostic indicator.33 A possible explanation is the higher susceptibility to inflammation and thrombotic complications in obese patients. Debate exists about the appropriate dose for prophylaxis in obese patients with limited data to guide care. These patients should be given a weight‐adjusted appropriate prophylactic dose at admission, with an increase to intermediate intensity or full therapeutic dose based on clinical parameters (Figure 1).34., 35. Treatment doses also require adjustment for weight.36., 37.

7. THE ROLE OF POINT‐OF‐CARE TESTING

Point‐of‐care testing, including viscoelastic testing, has been used in the critical care setting to guide transfusion of blood products in patients undergoing cardiothoracic surgery, liver transplantation surgery, massive transfusion protocols for trauma, and postpartum haemorrhage.38 Point‐of‐care testing has never been validated for use in patients to predict risk of bleeding or thrombosis, although several studies have examined this aspect.39 Ranucci et al reported hemostatic changes in patients with COVID‐19 pneumonia using Quantra Hemostasis analyser (Quantra System, HemoSonics LLC), using a device based on lower manipulation of the samples because blood is directly suctioned from citrated vials.17 The study reported increased clot firmness consistent with hypercoagulability, but decreased biomarkers with a higher level of anticoagulation; and clopidogrel if platelet count >400 000 cells/μL. This small study provides important initial information, but requires validation using larger patient numbers. Thromboelastography parameters in an Italian study of 24 patients were also suggestive of hypercoagulability, as shown by decreased R time and K value, and increased K angle and MA.40 ROTEM analysis by Pavoni and colleagues also demonstrated a state of severe hypercoagulability not obvious on standard coagulation parameters.41

8. HEPARIN‐INDUCED THROMBOCYTOPENIA

The use of heparin can be associated with HIT, a well‐known side effect of this drug.42 HIT is also more common in patients who have associated inflammatory conditions, a finding that may reflect increased platelet activation in patients receiving UFH or therapeutic doses of LMWH.43 Because thrombocytopenia is uncommon in patients with COVID‐19, a significant drop in platelet count that begins 5 or more days after starting UFH or LMWH should raise suspicion for HIT, especially if additional explanations such as bacterial superinfection or consumption coagulopathy has been excluded. Moreover, development of clinically evident venous or arterial thrombosis in a patient receiving heparin should also prompt consideration of HIT.44 Until the diagnosis of HIT can be confirmed, heparin exposure that includes line flushes should be discontinued and substituted with an alternate anticoagulant such as danaparoid, fondaparinux, bivalirudin, or argatroban.42 Recently, high‐dose intravenous immunoglobulin has been advocated as an adjunctive treatment for severe HIT,45 and used with anecdotal success in deteriorating patients with COVID‐19 infection.46

9. LIMITATIONS OF THE PUBLISHED STUDIES ON ANTICOAGULATION IN COVID‐19

Overall, all of the existing studies about anticoagulation type and dosing in COVID‐19 share the same limitations: (a) the retrospective nature and (b) a limited population size. These two factors led to a lack of information on the effects of different anticoagulation regimens in terms of containment of thromboembolic complications. The recommendations from the different societies are summarized in Table 2 . Several trials are under way examining the type, and dose of heparin in patients admitted with COVID‐19. Additional antithrombotic agents to heparin are also under evaluation.

Table 2.

Existing guidelines and consensus documents addressing anticoagulation in COVID‐19

| Source | Setting | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Thachil et al4 | ISTH interim guidance | Prophylactic dose of LMWH in all patients requiring hospitalization |

| Jin et al50 | CPAM | Evaluate the risk of venous embolism in patients and use LMWH or heparin in high‐risk patients without contraindications |

| Song et al51 | Committee of Critical Care Medicine, Chinese Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis | In severe COVID‐19 patients with coagulation dysfunction, anticoagulant therapy using unfractionated heparin/low‐ molecular weight heparin is recommended to reduce the depletion of coagulation substrates |

| Vivas et al52 | Working Group on Cardiovascular Thrombosis of the Spanish Society of Cardiology | 1. Nonsevere case and no high thrombotic risk: LMWH prophylactic dose 2. Nonsevere case and high thrombotic or severe case and no high thrombotic risk: Intermediate LMWH dose 3. Severe case and high thrombotic risk: Anticoagulant LMWH dose |

| Bikdeli et al53 | Endorsed by ISTH, NATF, ESVM, and others | Hospitalized patients with COVID‐19 eligible for anticoagulation. “If VTE prophylaxis is considered, enoxaparin 40 mg daily or similar LMWH regimen (eg, dalteparin 5000 U daily) can be administered. Subcutaneous heparin (5000 U twice to three times per day) can be considered for patients with renal dysfunction (ie, creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min).” Insufficient data to consider routine therapeutic or intermediate‐dose parenteral anticoagulation. |

| Spyropoulos et al54 | ISTH Clinical Guidance | Prophylactic dose of UFH or LMWH for ICU patients is recommended, and 50% of experts recommend intermediate dose of LMWH in high‐risk patients. |

| Moores et al55 | CHEST Guideline | LMWH or UFH for critical patients over fondaparinux or a DOAC. Recommend against the use of antiplatelets. |

| https://www.hematology.org/covid‐19 | American Society of Hematology | Standard prophylaxis for all hospitalized patients |

| https://www.covid19treatmentguidelines.nih.gov/ | National Institutes of Health | Hospitalized adults with COVID‐19 should receive venous thromboembolism prophylaxis per the standard of care for other hospitalized adults |

| https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/clinical‐management‐of‐novel‐cov.pdf | World Health Organization | Use pharmacological prophylaxis (low molecular weight heparin [preferred if available] or heparin 5000 units subcutaneously twice daily) in adolescents and adults without contraindications. |

Abbreviations: CPAM, China International Exchange and Promotive Association for Medical and Health Care; DOAC, direct oral anticoagulant; ESVM, European Society of Vascular Medicine; ISTH, International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis; NATF, North American Thrombosis Forum.

10. SUMMARY

Thrombosis is a major problem in patients with COVID‐19 requiring hospitalization. Anticoagulation is important in these patients but questions have arisen about the appropriate type, dose, and timing of anticoagulation. Existing guidelines and consensus documents are providing general suggestions on the LMWH dose based on the severity of the disease and the thrombotic risk, but a link between coagulation markers and anticoagulation regimen is still lacking. Many clinical trials addressing these questions are in progress; participation in these trials is encouraged to determine the best management strategies for COVID‐19 patients. Increasing knowledge with rapid sharing is required to adequately care for patients in this pandemic.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Dr. Ortel has received royalties from Up To Date; has provided consulting services to Instrumentation Laboratory; and has received research funding from Instrumentation Laboratory, Siemens, Stago, and Ergomed. Dr. Warkentin has received lecture honoraria from Alexion and Instrumentation Laboratory and royalties from Informa (Taylor & Francis); has provided consulting services to Aspen Global, Bayer, CSL Behring, Ergomed, and Octapharma; has received research funding from Instrumentation Laboratory; and has provided expert witness testimony relating to heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia (HIT) and non‐HIT thrombocytopenic and coagulopathic disorders. Dr. Thachil has received honoraria from Bayer, BMS‐Pfizer, Daichii‐Sankyo, Boehringer, Mitsubishi, Novo Nordisk, Octapharma, Novartis, Amgen, Norgine, Alexion, Sobi, and CSL‐Behring. The remaining authors state that they have no conflicts of interests.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Jeco Thachil conceived the paper and drafted the first manuscript. Nicole P. Juffermans, Marco Ranucci, Jean M. Connors, Theodore E. Warkentin, Thomas L. Ortel, Marcel Levi, Toshiaki Iba, and Jerrold H. Levy made critical comments. All authors approved the final submission.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

None

Footnotes

Manuscript handled by: Marc Carrier

Final decision: Marc Carrier, 09‐Jul‐2020

REFERENCES

- 1.Cui S., Chen S., Li X., Liu S., Wang F. Prevalence of venous thromboembolism in patients with severe novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(6):1421–1424. doi: 10.1111/jth.14830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klok F.A., Kruipb M.J.H.A., van der Meerc N.J.M., et al. Incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19. Thromb Res. 2020;S0049‐3848(20):30120–30121. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tang N., Bai H., Chen X., Gong J., Li D., Sun Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1094–1099. doi: 10.1111/jth.14817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thachil J., Tang N., Gando S., et al. ISTH interim guidance on recognition and management of coagulopathy in COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(5):1023–1026. doi: 10.1111/jth.14810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hirsh J., Warkentin T.E., Shaughnessy S.G., et al. Heparin and low‐molecular weight heparin: mechanism of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy and safety. Chest. 2001;119(1Suppl):64S–95S. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1_suppl.64s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirsh J., Bauer K.A., Donati M.B., Gould M., Samama M.M., Weitz J.I. Parenteral anticoagulants: American College of Chest Physicians evidence‐based clinical practice guidelines (8th edition) Chest. 2008;133(6):141S–159S. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Smythe M.A., Priziola J., Dobesh P.P., Wirth D., Cuker A., Wittkowsky A.K. Guidance for the practical management of the heparin anticoagulants in the treatment of venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2016;41(1):165–186. doi: 10.1007/s11239-015-1315-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang Y., Xiao M., Zhang S., et al. Coagulopathy and antiphospholipid antibodies in patients with Covid‐19. New Engl J Med. 2020;1105:208–213. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bowles L., Platton S., Yartey N., et al. Lupus anticoagulant and abnormal coagulation tests in patients with Covid‐19. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(3):288–290. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2013656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harzallah I., Debliquis A., Drénou B. Lupus anticoagulant is frequent in patients with Covid‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):2064–2065. doi: 10.1111/jth.14867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang N., Li D., Wang X., Sun Z. Abnormal coagulation parameters are associated with poor prognosis in patients with novel coronavirus pneumonia. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(4):844–847. doi: 10.1111/jth.14768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guan W.J., Ni Z.Y., Hu Y., et al. China medical treatment expert group for Covid‐19. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(18):1708–1720. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2002032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harr J.N., Moore E.E., Chin T.L., et al. Postinjury hyperfibrinogenemia compromises efficacy of heparin‐based venous thromboembolism prophylaxis. Shock. 2014;41(1):33–39. doi: 10.1097/SHK.0000000000000067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Levine M.N., Hirsh J., Gent M., et al. A randomized trial comparing activated thromboplastin time with heparin assay in patients with acute venous thromboembolism requiring large daily doses of heparin. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:49–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Finley A., Greenberg C. Review article: heparin sensitivity and resistance: management during cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Analg. 2013;116(6):1210–1222. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31827e4e62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chlebowski M.M., Baltagi S., Carlson M., Levy J.H., Spinella P.C. Clinical controversies in anticoagulation monitoring and antithrombin supplementation for ECMO. Crit Care. 2020;24(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-2726-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ranucci M., Ballotta A., Di Dedda U., et al. The procoagulant pattern of patients with COVID‐19 acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1747–1751. doi: 10.1111/jth.14854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koster A., Zittermann A., Schirmer U. Heparin resistance and excessive thrombocytosis. Anesth Analg. 2013;117(5):1262. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3182a5392f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warkentin T.E. Anticoagulant failure in coagulopathic patients: PTT confounding and other pitfalls. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(1):25–43. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2013.823946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koster A., Faraoni D., Levy J.H. Argatroban and bivalirudin for perioperative anticoagulation in cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2018;128(2):390–400. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000001976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cook D., Meade M., Guyatt G., et al. PROTECT investigators for the Canadian critical care trials group and the Australian and New Zealand intensive care society clinical trials group, Dalteparin versus unfractionated heparin in critically ill patients. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(14):1305–1314. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1014475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klok F.A., Kruip M.J.H.A., van der Meer N.J.M., et al. Confirmation of the high cumulative incidence of thrombotic complications in critically ill ICU patients with COVID‐19: an updated analysis. Thromb Res. 2020;S0049‐3848(20):30157–30162. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Middeldorp S., van Haaps T.F., et al. Incidence of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1995–2002. doi: 10.1111/jth.14888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Helms J., Tacquard C., Severac F., et al. High risk of thrombosis in patients with severe SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: a multicenter prospective cohort study. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(6):1089–1098. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-06062-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paranjpe I., Fuster V., Lala A., et al. Association of treatment dose anticoagulation with in‐hospital survival among hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;S0735‐1097(20):35218–35219. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goyal P., Choi J.J., Pinheiro L.C., et al. Clinical characteristics of Covid‐19 in New York City. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(24):2372–2374. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2010419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wright F.L., Vogler T.O., Moore E.E., et al. Fibrinolysis shutdown correlates to thromboembolic events in severe COVID‐19 infection. J Am Coll Surg. 2020;S1072‐7515(20):30400–30402. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Colman R.W., Schmaier A.H. Contact system: a vascular biology modulator with anticoagulant, profibrinolytic, antiadhesive, and proinflammatory attributes. Blood. 1997;90(10):3819–3843. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruan C.C., Gao P.J. Role of complement‐related inflammation and vascular dysfunction in hypertension. Hypertension. 2019;73(5):965–971. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.11210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maas C., Renné T. Coagulation factor XII in thrombosis and inflammation. Blood. 2018;131(17):1903–1909. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-04-569111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Favaloro E.J., Bonar R., Aboud M., et al. How useful is the monitoring of (low molecular weight) heparin therapy by anti‐Xa assay? A laboratory perspective. Lab Hematol. 2005;11(3):157–162. doi: 10.1532/LH96.05028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garcia D.A., Baglin T.P., Weitz J.I., Samama M.M. Parenteral anticoagulants: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American college of chest physicians evidence based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2):e24S–e43S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tamara A., Tahapary D.L. Obesity as a predictor for a poor prognosis of COVID‐19: a systematic review. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):655–659. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee Y.R., Blanco D.D. Efficacy of standard dose unfractionated heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis in morbidly obese and non‐morbidly obese critically Ill patients. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2017;44(3):386–391. doi: 10.1007/s11239-017-1535-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shlensky J.A., Thurber K.M., O'Meara J.G., et al. Unfractionated heparin infusion for treatment of venous thromboembolism based on actual body weight without dose capping. Vasc Med. 2020;25(1):47–54. doi: 10.1177/1358863X19875813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ebied A.M., Li T., Axelrod S.F., Tam D.J., Chen Y. Intravenous unfractionated heparin dosing in obese patients using anti‐Xa levels. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;49(2):206–213. doi: 10.1007/s11239-019-01942-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sebaaly J., Covert K. Enoxaparin dosing at extremes of weight: literature review and dosing recommendations. Ann Pharmacother. 2018;52(9):898–909. doi: 10.1177/1060028018768449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Curry N.S., Davenport R., Pavord S., et al. The use of viscoelastic haemostatic assays in the management of major bleeding: a British Society for Haematology guideline. Br J Haematol. 2018;182(6):789–806. doi: 10.1111/bjh.15524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Levi M., Hunt B.J. A critical appraisal of point‐of‐care coagulation testing in critically ill patients. J Thromb Haemost. 2015;13(11):1960–1967. doi: 10.1111/jth.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Panigada M., Bottino N., Tagliabue P., et al. Hypercoagulability of COVID‐19 patients in intensive care unit. a report of thromboelastography findings and other parameters of hemostasis. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(7):1738–1742. doi: 10.1111/jth.14850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pavoni V., Gianesello L., Pazzi M., Stera C., Meconi T., Frigieri F.C. Evaluation of coagulation function by rotation thromboelastometry in critically ill patients with severe COVID‐19 pneumonia. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(2):281–286. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02130-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cuker A., Arepally G.M., Chong B.H., et al. American Society of Hematology 2018 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. Blood Adv. 2018;2(22):3360–3392. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018024489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Arepally G.M. Heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2017;129(21):2864–2872. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-11-709873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Warkentin T.E. Think of HIT when thrombosis follows heparin. Chest. 2006;130(3):631–632. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.3.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Warkentin T.E. High‐dose intravenous immunoglobulin for the treatment and prevention of heparin‐induced thrombocytopenia: a review. Exp Rev Hematol. 2019;12(8):685–698. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2019.1636645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao W., Liu X., Bai T., et al. High‐dose intravenous immunoglobulin as a therapeutic option for deteriorating patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(3) doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofaa102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bargellini I., Cervelli R., Lunardi A., et al. Spontaneous bleedings in COVID‐19 patients: an emerging complication. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol. 2020;43(7):1095–1096. doi: 10.1007/s00270-020-02507-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carroll E., Lewis A. Catastrophic intracranial hemorrhage in two critically Ill patients with COVID‐19. Neurocrit Care. 2020:1–5. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-00993-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al‐Samkari H., Karp Leaf R.S., Dzik W.H., et al. COVID and coagulation: bleeding and thrombotic manifestations of SARS‐CoV2 infection. Blood. 2020;136(4):489–500. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin Y.H., Cai L., Cheng Z.S., et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019‐nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version) Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):4. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-0233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song J.C., Wang G., Zhang W., et al. Chinese expert consensus on diagnosis and treatment of coagulation dysfunction in COVID‐19. Mil Med Res. 2020;7(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40779-020-00247-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vivas D., Roldán V., Esteve‐Pastor M.A., et al. Recommendations on antithrombotic treatment during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Position statement of the Working Group on Cardiovascular Thrombosis of the Spanish Society of Cardiology. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2020;73(9):749–757. doi: 10.1016/j.rec.2020.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bikdeli B., Madhavan M.V., Jimenez D., et al. COVID‐19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow‐up: JACC state‐of‐the‐art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Spyropoulos A.C., Levy J.H., Ageno W., et al. Scientific and standardization committee communication: clinical guidance on the diagnosis, prevention and treatment of venous thromboembolism in hospitalized patients with COVID‐19. J Thromb Haemost. 2020;18(8):1859–1865. doi: 10.1111/jth.14929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Moores L.K., Tritschler T., Brosnahan S., et al. Prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of VTE in patients With COVID‐19. Chest. 2020;S0012‐3692(20):31625–31631. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.05.559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]