Introduction

As severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2), the virus that causes COVID‐19, is highly infectious and variable, and given that we now understand a large proportion of asymptomatic carriers can be still infectious [1], it is expected that a normalization of epidemic prevention and control measures will be required for a long time worldwide. Our neurology department at Xuanwu Hospital in Beijing is one of the national centers for the research and treatment of neurological disorders in China. Since healthcare settings are at a high risk of virus dissemination, we have implemented timely strategies to reduce cross‐infection and protect our patients and staff to avoid critically overloading our system as a result of a sudden decrease in staff because of quarantining or isolation [2]. Moreover, having made it through several months of this crisis, it is now clear to us that the pattern of clinical practice and research at our hospital has already undergone major changes, many of which are very likely to persist well into the future. In the present paper, we summarize our experiences in adapting neurological practice during the COVID‐19 outbreak and post‐pandemic era, and we discuss how our experiences are helping us think about and meet some unsolved problems and challenges.

Emergency and inpatient care

During the SARS epidemic in 2003, China established fever clinics in all general hospitals (above level two) [3]. Each outpatient with a body temperature higher than 37.3°C attends a fever clinic first to screen for potential infectious diseases. Policies ensure that fever clinic staff are equipped with enhanced medical personal protective equipment (PPE) compared to the ordinary medical staff at a hospital. At Xuanwu Hospital, patients with neurological emergencies accompanied by fever are first sent to the fever clinic, and the neurologists go to the fever clinic to treat these patients. Our fever clinic is equipped with a dedicated computer tomography (CT) scanner; therefore, patients with acute ischaemic stroke can be treated with intravenous thrombolysis without leaving the fever clinic.

We adopted several changes to our inpatient management strategies and optimized our workflow to admit patients from the emergency room (ER) or clinics. First, we deployed a multidisciplinary team (MDT) screening protocol, seeking to detect asymptomatic inpatients with potential SARS‐CoV‐2 infection. The MDT comprises ER neurologists, radiologists, ER internists, and consulting pulmonologists along with infectious disease specialists. Information spanning four categories was obtained, including detailed epidemiological information, core clinical features of COVID‐19 (fever and/or respiratory symptoms), a chest CT scan, and a complete blood count. If patients have conditions that may preclude completion of CT, lung ultrasonography is an alternative option [4]. The team stratified incoming patients based on an evaluation of the above risk factors. As nucleic acid testing capability increased over time, we integrated nucleic acid tests into our protocol (since April, 2020). Thus, every patient is carefully screened for COVID‐19 infection prior to admission.

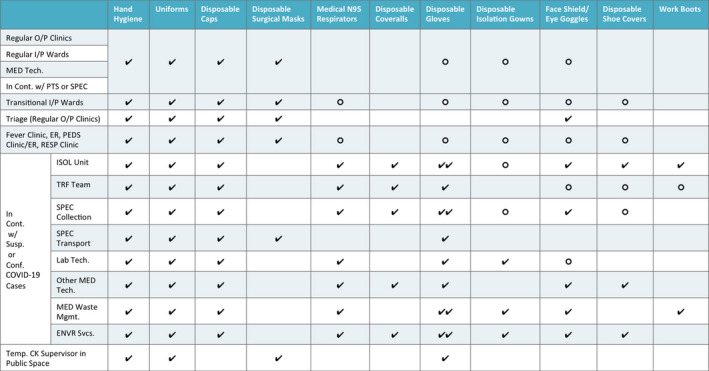

Second, after admission, we set up a transitional ward that was designed to solve two major problems we were facing: a shortage of PPE and a limited number of single rooms. The rationale for the transitional ward was based on the incubation period of COVID‐19 from early reports of confirmed COVID‐19 cases in Hubei, China [5]. We dedicated one floor of our wards for this purpose, and the transitional ward used a higher level of PPE. Newly admitted patients would spend 5 days in the transitional ward and were transferred to the regular ward with standard PPE. Notably, virtual visitations were encouraged for patients in the transitional ward, which did not permit physical entry for any visitors. Importantly, we enforced different levels of PPE depending on the assessment of anticipated exposure risk (summarized in Fig. 1) and deployed mandatory training programs to ensure the appropriate use of PPE.

Figure 1.

A proposed guideline for application of personal protection equipment by healthcare workers. ENVR Svcs., environmental service; ER, emergency room; In Cont. w/PTS or SPEC, in contact with patients or specimen; In Cont. w/Susp. or Conf. COVID‐19 Cases, in contact with suspected or confirmed COVID‐19 cases; I/P, inpatient; ISOL, isolation unit; Lab Tech., laboratory technician; MED Tech., medical technician; MED Waste Mgmt., medical waste management; O/P, outpatient; PEDS, pediatric; RESP, respiratory; clinic; SPEC, specimen; Temp. CK Supervisor in Public Space, temperature check supervisor in public space. TRF, transfer team. ✔:required; ○: selected based on exposure risk.

Outpatient care

The largest‐scale changes we have deployed in the pandemic and post‐pandemic periods deal with remote care of patients for whom in‐person clinic visits have become unfeasible. Obviously, telemedicine technologies have been extensively developed in the past. However, there have been some major barriers to the widespread deployment of telemedicine. Given the unique context our department faced with COVID‐19, we were able to deploy some real telemedicine innovations that allowed us to provide continuous care for patients with chronic neurological disorders.

Firstly, Xuanwu Hospital has developed the 'Xuanwu‐APP', which supports online consultation, the scheduling of appointments, checking of test results, prescription writing, and coordination of the physical delivery of medicines. Beyond these relatively obvious advantages, the fundamental enabling aspect of the Xuanwu‐APP is its integrated implementation of medical insurance coverage: this enabled reimbursement of patients for telemedicine services, which profoundly increased the utilization rates of our patients. We found that once the patients were comfortable with the reimbursement options, they were eager to engage with our physicians via telemedicine. It is notable that the APP and the reimbursement functionality also facilitated specialist consultations with experts at senior hospitals, which substantially reduced the need for highly resource‐intensive patient transfer between hospitals in the pandemic. If a remotely monitored outpatient presents suspected features of COVID‐19, we will recommend the patient visits the fever clinic immediately with appropriate personal protection equipment.

New technologies and impacts on clinical research

Our recently gained experience using remote technologies has us very excited about their integration into the design and management of clinical research. For example, videoconferencing is optimal for conducting pre‐trial screening and for both participant training and consultation. For many interventions under study, online supervision should be acceptable. Further, participants can be encouraged to record and upload a video when taking study drugs or conducting non‐pharmacological interventions, and an e‐diary (with attendant notification functionality) can clearly be a useful digital tool for monitoring symptoms and side effects. Currently, multicentre neuroimaging trials have become a trend, although there are still challenges to correct for heterogeneity among centers [6]. We are highly confident that collaboration among regional or even nationwide multi‐site neuroimaging facilities will increase in the wake of this crisis, primarily because of its obviously improved convenience and safety for participants.

Summary

Our strategies and insights about future directions could be valuable as a reference for the global neurology community. There are still many ongoing challenges related to COVID‐19, but we believe that this crisis can be viewed as a powerful chance to advance the implementation of new technologies that facilitate pandemic‐specific changes as well as attractive upgrades that can profoundly affect both clinical practice and research in the post‐COVID 19 era.

Declaration of conflicts of interest

The authors declare no financial or other conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Y. Tang, Email: tangyi@xwhosp.org.

Y. Wang, Email: wangyuping01@sina.cn.

G. Zhao, Email: ggzhao@vip.sina.com.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the study.

References

- 1. Wang C, Horby PW, Hayden FG, Gao GF. A novel coronavirus outbreak of global health concern. Lancet 2020; 395: 470–473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pascarella G, Strumia A, Piliego C, et al. COVID‐19 diagnosis and management: a comprehensive review. J Intern Med 2020; 288: 192–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zhang J, Zhou L, Yang Y, Peng W, Wang W, Chen X. Therapeutic and triage strategies for 2019 novel coronavirus disease in fever clinics. Lancet Respir Med 2020; 8: e11–e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piliego C, Strumia A, Stone MB, Pascarella G. The ultrasound guided triage: a new tool for prehospital management of COVID‐19 pandemic. Anesth Analg 2020;131: e93–e94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Guan WJ, Ni ZY, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Poldrack RA, Gorgolewski KJ. Making big data open: data sharing in neuroimaging. Nat Neurosci. 2014; 17: 1510–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the study.