Abstract

Background

The novel coronavirus, SARS‐CoV‐2, caused the COVID‐19 global pandemic. In response, the Australian and New Zealand governments activated their respective emergency plans and hospital frameworks to deal with the potential increased demand on scarce resources. Surgical triage formed an important part of this response to protect the healthcare system's capacity to respond to COVID‐19.

Method

A rapid review methodology was adapted to search for all levels of evidence on triaging surgery during the current COVID‐19 outbreak. Searches were limited to PubMed (inception to 10 April 2020) and supplemented with grey literature searches using the Google search engine. Further, relevant articles were also sourced through the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons COVID‐19 Working Group. Recent government advice (May 2020) is also included.

Results

This rapid review is a summary of advice from Australian, New Zealand and international speciality groups regarding triaging of surgical cases, as well as the peer‐reviewed literature. The key theme across all jurisdictions was to not compromise clinical judgement and to enable individualized, ethical and patient‐centred care. The topics reported on include implications of COVID‐19 on surgical triage, competing demands on healthcare resources (surgery versus COVID‐19 cases), and the low incidence of COVID‐19 resulting in a possibility to increase surgical caseloads over time.

Conclusion

During the COVID‐19 pandemic, urgent and emergency surgery must continue. A carefully staged return of elective surgery should align with a decrease in COVID‐19 caseload. Combining evidence and expert opinion, schemas and recommendations have been proposed to guide this process in Australia and New Zealand.

Keywords: COVID‐19, health resources, personal protective equipment, surgery, surgical specialties, triage

In response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) pandemic, the Australian and New Zealand governments have activated their respective emergency plans and hospital frameworks to deal with the potential increased demand on scarce resources. Surgical triage is an important part of this response to protect the healthcare system's capacity to respond to COVID‐19.This rapid review summarises advice from Australian, New Zealand and international speciality groups regarding triaging of surgical cases, as well as the peer‐reviewed literature, and was utilised by the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons COVID‐19 Working Group of expert surgeons to formulate evidence‐based recommendations.

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS‐CoV‐2). 1 This disease has spread rapidly around the world. In the absence of effective treatment or vaccines, strict prevention and control methods have been applied to minimize community spread. 2 COVID‐19 has the potential to overrun the capacity of healthcare systems since a significant number of infected patients require hospitalization and critical care.

During this pandemic, the Australian Government Department of Health 3 and the Ministry of Health in New Zealand 4 enacted their health management plans to support an integrated and co‐ordinated response and ensure the appropriate allocation of resources. During the early phases of preparation and actions, there was a focus on ensuring healthcare services were organized to manage increased demand, particularly for scarce resources such as intensive care, and to protect healthcare workers from infection. 5 , 6 Health emergencies, such as those experienced in a pandemic, require priority‐setting, rationing and triage. Triage relates to decision‐making regarding the order of treating patients based on urgency of need; it should follow due process and be transparent. 7

In response to the COVID‐19 pandemic, and at the combined urging of the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons (RACS), the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists, the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, and the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists, 8 the Australian and New Zealand Governments issued initial directives regarding elective surgery. The advice was to either postpone surgery or, for those that could not wait, redirect it from public to private providers, if necessary, due to a potential lack of capacity in the public healthcare system. 9 , 10 The intention of these directives was to protect surgical teams and patients from infection, and to preserve medical supplies and vital equipment needed for the anticipated surge in COVID‐19 patients requiring high‐acuity care. RACS 11 and the specialty surgical societies produced guidelines to dispel uncertainty around patient and procedure classifications and support decision‐making for the postponement of surgery.

There was the concern that a rigid adherence to restrictions in elective cases may create the unintended consequence of a surge in surgery following the first wave of COVID‐19, potentially overwhelming and compromising healthcare in Australia and New Zealand. The continued requirement to postpone elective surgery depended on the effectiveness of social control measures in limiting the number of infections.

The aim of this review was to summarize the advice of Australian and New Zealand speciality societies, as well as those of other countries, regarding triaging of surgical cases. Based on this advice and input from an expert working group, overarching principles have been provided to inform local decision‐making on elective surgery, and to protect surgical teams while maintaining equitable access to surgical treatment. It should be acknowledged that the applicability of these guidelines is dependent on the COVID‐19 caseload within the locality of implementation.

Methods

A rapid review methodology was adapted to search for all levels of evidence on triaging surgery during the current COVID‐19 outbreak. Searching for peer‐reviewed publications was limited to PubMed from inception to 10 April 2020. The search developed for the ‘Guidelines for safe surgery: open versus laparoscopic’ rapid review 12 , 13 was adapted to target surgery triage in the COVID‐19 pandemic.

PubMed searches were supplemented with grey literature searches using the Google search engine. Searching was limited to websites of departments of health, surgical colleges, health authorities (e.g. World Health Organization, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)), and major teaching hospitals. Relevant articles were also sourced through the RACS COVID‐19 Working Group.

Study selection and extraction was performed by KW, DRT, JGK and WJB. All levels of evidence were considered, and inclusion was not limited by language. Non‐English articles were translated using Artificial Intelligence translation tools, which may affect the interpretation of results. Included studies report primary research, reviews and opinion pieces that are either in print or published. When necessary, supplementary searches were conducted to fill any evidence gaps identified during meetings with the Working Group. In addition, recent Australian and New Zealand government advice regarding triage of elective surgery since the completion of this review is included.

The working group responsible for this evidence‐based guidance consisted of expert general surgeons, with additional advice provided by representatives from three specialty colleges and one surgical association within Australia and New Zealand.

Results and discussion

Guidance from Australia and New Zealand

The challenging situation due to the COVID‐19 pandemic is recognized, which has impacted surgical healthcare staff and their patients. RACS 14 and the Australian and New Zealand specialty societies produced guidance for managing surgical cases at this time (Tables S1–S4).

Advice provided at the time highlighted the need to triage and ration cases due to the potential shortage of hospital and intensive care unit (ICU) beds, ventilators and personal protective equipment (PPE) during the peak of the pandemic; the impact on hospital resources due to staff sickness, quarantine or home duties; and the potential increased exposure of surgeons and other healthcare workers due to community spread from undiagnosed patients. 15 It was also advised that decisions regarding patient treatment consider the available healthcare staff required for each case. 16

Individual patient‐needs assessments considering patient age, comorbidities, disease site and staging, and the wishes of the patient, were to be conducted in the context of the capacity to deliver care. Where possible, non‐operative treatment was to be considered, especially where significant comorbidities were present. It was critical to have a plan to deal with complications, especially in settings where resources were potentially limited. Surgery was to be avoided, where possible, in older or more compromised patients. 17 The importance of multidisciplinary care was stressed, with multidisciplinary team meetings considering the complex issues. There could have even been consideration of inter‐hospital multidisciplinary teams, or referral to less affected centres. 16

The COVIDSurg Collaborative estimated that due to the transient suspension of elective surgery around the world, a global backlog of operations was created that could take close to a year to clear. 18 Thus, where a brief delay in treatment or diagnosis would not result in worse outcomes, there was to be no unnecessary delay. These cases might have become more urgent and complex as the disease progressed, resulting in a backlog of surgical cancer cases requiring treatment coinciding with a COVID‐19 peak. 19 The need to avoid potential long‐term harm for patients who may have suffered a significant adverse outcome by a considerable delay in their surgery 17 needed to be considered alongside the impact of a potential COVID‐19 infection in surgical patients, especially for those with comorbidities that might have worsened their outcomes if infected. 20

Guidance on factors to assist decision‐making regarding the urgency of the investigation or intervention 21 aimed to achieve the shortest hospital stay with the fewest likely complications, the least likelihood of needing critical care or shortest duration in critical care, the highest life expectancy and return to best functional capacity, and the lowest combined utilization of hospital resources and lowest risk of transmitting COVID‐19 to healthcare workers.

Where there was uncertainty regarding the urgency for surgery it was recommended that surgeons confer with a colleague or the hospital administration 22 to obtain a documented, independent peer opinion 23 or have cases reviewed by a hospital‐based committee before scheduling surgery. 17

Certain surgical procedures presented a higher risk due to aerosol production as well as the anatomical site of the surgery, where the virus was more likely to be present. In COVID‐19‐infected patients, otolaryngology head and neck surgeons were at particular risk due to potential exposure to a high viral load. 24 A guide for triage of endoscopic procedures during the COVID‐19 pandemic was produced by the Gastroenterological Society of Australia. 25

International guidance

Similar guidelines for triage were produced in other countries (Tables S1–S4). The American College of Surgeons (ACS) developed a phased model to support decision‐making by both administrators and healthcare professionals relative to the acuity of the specific local COVID‐19 situation. 26 In the UK, the Royal College of Surgeons of England 27 stressed the importance of maintaining a real‐time data‐driven approach for both the governance of surgical management and the allocation of resources within a healthcare facility. Further, the ACS advised that a Surgical Review Committee composed of surgery, anaesthesiology and nursing personnel is essential to provide defined, transparent and responsive oversight amidst this current crisis. 28 Multidisciplinary care was deemed crucial, and to be implemented at all stages of a surgical patient's management.

When making treatment decisions during the COVID‐19 pandemic, multiple factors should be considered, including current and projected COVID‐19 cases in the community and region, the hospital's ability to implement telehealth, supply of PPE and staff, medical office/ambulatory service location capacity, testing capability in the local community, health and age of each individual patient, and the urgency of the respective surgical treatment or service. 29 , 30 It is crucial that administrative personnel provide input to clinical surgical staff regarding the status of hospital and community supply of resources, so that logistical efficiency is optimized. 31

Hospitals and surgeons were to review all scheduled elective procedures with a plan to minimize, postpone or cancel scheduled operations, endoscopies 32 and other invasive procedures as necessary. 27 , 33 , 34 At the height of the pandemic, the capacity of ICU facilities was to be re‐evaluated before scheduling any surgery, especially for operations with a high probability for postoperative intensive care. In general, non‐essential surgery should have been deferred wherever possible 29 ; however, procedures and operations should have proceeded if a delay was likely to prolong the hospital stay, increase the likelihood of later hospital admission, or cause patient harm. Patients for whom medical management of a surgical condition failed, should have been considered for surgery to decrease the future use of resources for the treating institution. 35 The ACS recommended the Elective Surgery Acuity Scale from St. Louis University to assist in the surgical decision‐making process for triage of non‐emergent operations. 31 Similarly, multiple international organizations developed classification systems designed to facilitate the rapid triage of patients depending on the severity and urgency of their clinical situation. 26 , 32 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 , 42

The Spanish Association of Surgery strongly advised full patient testing and workup for COVID‐19 prior to surgery, with surgery suspended until test results are returned. 43 This was particularly important if a patient presented with any symptoms of COVID‐19 or influenza‐like illness or had been in direct contact with a known positive COVID‐19 case. 44 In these situations, a complete COVID‐19 workup was to be conducted and surgery should not have proceeded within 14 days, even if the patient was asymptomatic. The exceptions to this were urgent situations where an immediate threat to a patient's life or organs necessitated operative management. In these cases the operation would have to be conducted with minimal staff and full PPE precautions. 29 , 30 , 42 , 43 It was important that any decisions regarding surgical procedures were made using all available medical and logistical information, not solely based on risks associated with COVID‐19. 31

Perioperative considerations

The status of COVID‐19 in Australia 45 and New Zealand 46 was reported daily. The number of new cases slowed significantly after the introduction of social distancing. 47 Modelling conducted by the Australian government, 48 but based on overseas data, showed that ICU bed capacity exceeded requirements in the early stages of the pandemic. The situation was similar in New Zealand, with ICU admissions well below the total capacity. 46

The risk of perioperative complications associated with COVID‐19 could be significant, and profoundly affect postoperative mortality and complication rates. 49 , 50 , 51 , 52 This may influence future considerations regarding preoperative testing, but ideally, if it does not worsen postoperative patient outcomes, the COVID‐19 status of surgical patients should be determined before surgery. 53 Where this is not possible, it is key to know which patients pose the highest risk, including those more likely to have been exposed to COVID‐19 due to their profession. Lippi et al. reviewed current RT‐PCR tests for COVID‐19 and identified issues of false negative results in up to 30% of cases. 54 In emergency cases, when time to surgery does not allow return of RT‐PCR test results, a patient's symptoms, contact history and diagnostic imaging can be used to assess risk of COVID‐19 infection. Emergency surgery should be performed promptly with the minimal number of operative staff all using full PPE and, where possible, avoiding aerosol‐generating procedures. 53

There were concerns in the Australian and New Zealand media that PPE was in short supply. To address this concern a rapid review was conducted on Personal Protective Equipment for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Evidence‐Based Guidance from the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons 55 and a subsequent manuscript published in this issue. 63 It was concluded that adequate PPE was available in accordance with the COVID‐19 status in Australia and New Zealand, however this situation could have changed rapidly if a second wave of infection occurred after containment measures were relaxed.

Staged return to surgery

Published evidence pointed to the need for a staged return to surgery that allowed release of staff, beds and resources should COVID‐19 cases rapidly increase. 56 It was advised that the decision to expand surgery caseload should be informed by local COVID‐19 information, preferably at a health‐network level. 57 Models were made available to evaluate the impact of infectious disease outbreaks at an area‐ or hospital‐level, for example, the COVID‐19 Hospital Impact Model (based on local COVID‐19 data for three Philadelphia hospitals 57 ) and the AsiaFluCap Simulator. 58 Australia collected local epidemiological data that could inform model inputs to generate outputs. Although the models are not perfect, they were able to assist decision‐making around local resource allocation to manage COVID‐19 and determine whether there was capacity to accommodate non‐emergency surgical cases.

In Australia, the Federal government issued new guidance on the restoration of elective surgery on 23 April 2020. 59 Noted risks for the reintroduction of elective surgery related to the increased burden on ICUs, infection control, PPE supplies and preoperative testing for COVID‐19. Principles for the first tranche of elective surgery recommencement were outlined. Based on the categories outlined by the Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council, 60 a suggested approach (from 27 April 2020) included reopening 25% of elective surgery and endoscopy lists, focusing on category 2 procedures supplemented by some category 3 procedures, in addition to the previously allowed category 1 procedures.

Advice was provided by the New Zealand Ministry of Health's Planned Care Sector Advisory Group on 21 April 2020 for the resumption of delivery of planned care. The document ‘Increasing and improving Planned Care in accordance with the National Hospital Response Framework’ is for use from 27 April for Community Alert Level 3. 61

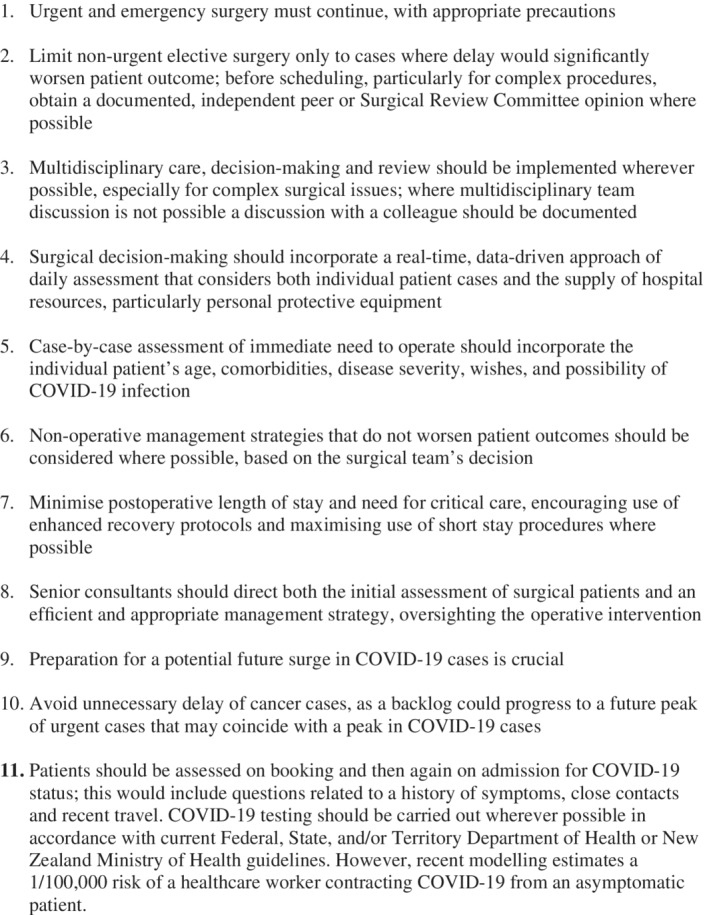

On the assumption that current COVID‐19 cases and related resource needs remain low, the RACS COVID‐19 Working Party developed the following recommendations (Fig. 1).

Fig 1.

Recommendations derived from rapid review of existing guidelines.

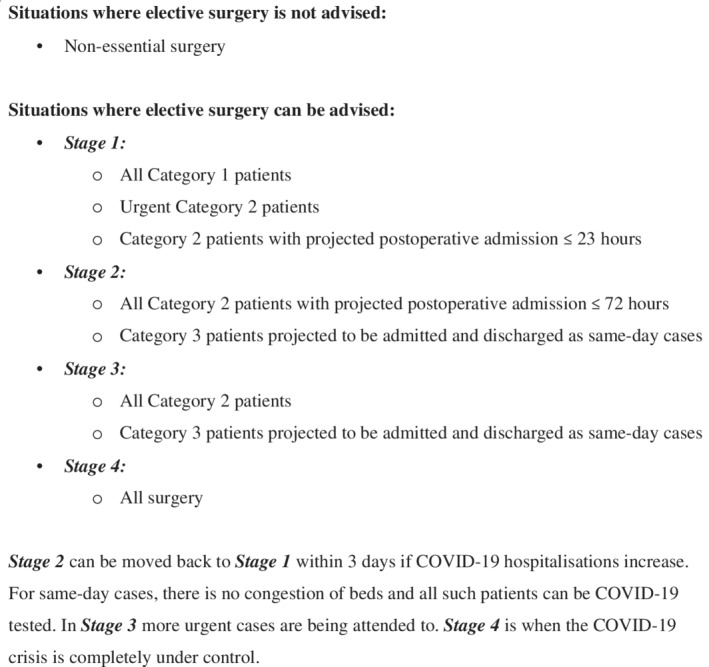

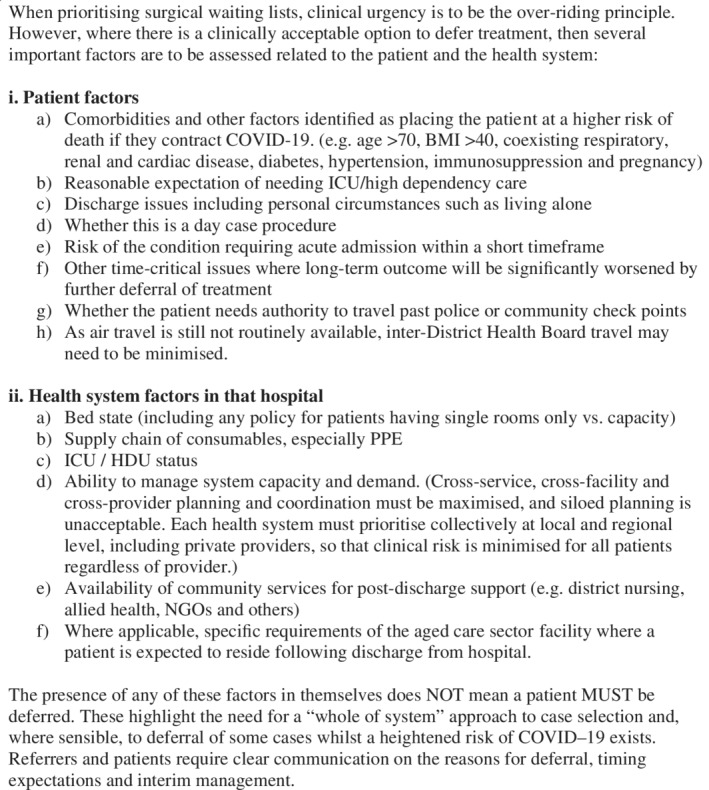

Schemata for guiding expansion of surgical services in Australia and New Zealand were also produced (Figs 2, 3). These guidelines balanced urgency with patient COVID‐19 status and resource needs for surgery, or ongoing healthcare needs if surgery was further postponed. They were designed to help health service providers develop clear plans about surgical procedures that should continue during the pandemic. 62

Fig 2.

Advised schema for Elective Surgery Triage within Australia (developed by COVID‐19 Working Group).

Fig 3.

Advised schema for Elective Surgery Triage within New Zealand (developed by the New Zealand National Board).

Conclusions

There was agreement across surgical specialties and jurisdictions regarding recommendations for surgical triage when faced with a high incidence of COVID‐19 infections. In such situations, COVID‐19 patients would have dominated hospital and ICU admissions, thereby limiting resources for surgery to the most urgent. Government directives of social distancing in Australia and the initial lockdown measures in New Zealand have restricted COVID‐19 transmission thus releasing resources for non‐COVID‐19 patients.

Based on the review findings and current incidence of infection, the schemata developed by the COVID‐19 Working Group for both Australia and New Zealand hoped to assist with broadening the criteria of allowable operations in the ongoing context of fighting the pandemic.

Limitations of the review

The limitation to a single database for sourcing peer‐reviewed publications may have overlooked some articles. In addition, the expedited publication of peer‐reviewed articles means the currency of information related to COVID‐19 changes rapidly. To mitigate this limitation, the review team established automated alerts to identify relevant evidence on this topic.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Supporting information

Table S1. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by a selection of General Surgical Societies/Associations, effective as of 17 April 2020.

Table S2. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by a selection of Orthopaedic Surgical Societies/Associations, effective as of 17 April 2020.

Table S3. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by a selection of Surgical Societies/Associations, effective as of 17 April 2020.

Table S4. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by international organizations, effective as of 17 April 2020.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Dr Vanessa Beavis, representing the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA); Dr Vicky H. Lu, representing the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Ophthalmologists (RANZCO); Dr James Churchill, representing the Royal Australasian College of Surgeons Trainees' Association (RACSTA); Dr Chloe Ayres, representing the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RANZCOG); Dr Shane Kelly, representing St John of God Healthcare. The study was funded by Medibank Better Health Foundation.

W. J. Babidge BApp Sci (Hons), PhD; D. R. Tivey BSc (Hons), PhD; K. Weidenbach BSc (Hons), PhD; T. G. Collinson MS, FRACS; P. J. Hewett MBBS, FRACS; T. J. Hugh MD, FRACS; R. T. A. Padbury PhD, FRACS; N. M. Hill MBChB, FRACS; G. J. Maddern PhD, FRACS.

References

- 1. World Health Organization . Naming the Coronavirus Disease (COVID‐19) and the Virus That Causes It. Geneva: World Health Organization. [Cited 16 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel‐coronavirus‐2019/technical‐guidance/naming‐the‐coronavirus‐disease‐(covid‐2019)‐and‐the‐virus‐that‐causes‐it

- 2. Dhama K, Sharun K, Tiwari R et al. COVID‐19, an emerging coronavirus infection: advances and prospects in designing and developing vaccines, immunotherapeutics, and therapeutics. Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 2020; 16: 1232–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Australian Government Department of Health . Australian Health Sector Emergency Response Plan for Novel Coronavirus (COVID‐19). Canberra: Commwealth of Australia. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.gov.au/resources/publications/australian‐health‐sector‐emergency‐response‐plan‐for‐novel‐coronavirus‐covid‐19?utm_source=health.gov.au&utm_medium=redirect&utm_campaign=digital_transformation&utm_content=covid19‐plan

- 4. COVID‐19 Public Health Response Strategy Team Ministry of Health, New Zealand Government . Background and Overview of Approaches to COVID‐19 Pandemic Control in Aotearoa/New Zealand. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/background-overview-approaches-covid-19-pandemic-contro-aotearoa-new-zealand-30mar20.pdf

- 5. Ministry of Health New Zealand Government . New Zealand Influenza Pandemic Plan: A Framework for Action, 2nd edn. Wellington: Ministry of Health, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Australian Government . Australian Health Management Plan for Pandemic Influenza. Canberra, ACT: Department of Health; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Petrini C. Triage in public health emergencies: ethical issues. Intern. Emerg. Med. 2010; 5: 137–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Sparnon T, Mitchell R, Roach V, Mack H. Medical Colleges Call for Urgent Freeze to all Non‐critical Elective Surgery. Melbourne: RANZCOG, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Prime Minister of Australia The Hon Scott Morrison MP . Elective Surgery, Media Release, 25 March 2020. Canberra: Prime Minister of Australia 2020.

- 10. New Zealand Ministry of Health . COVID‐19 Media Update, 29 March. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.govt.nz/news-media/news-items/covid-19-media-update-29-march

- 11. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons . Surgery Triage: Responding to the COVID‐19 Pandemic, 2nd edn. [Cited 9 Jun 2020.] Available from URL: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5254/2020-04-22_racs-triage-of-surgery-web.pdf

- 12. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons . Guidelines for Safe Surgery: Open versus Laparoscopic. 1st Edition., [Cited 9 June 2020.]. Available from: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5214/2020‐04‐15‐recommendations‐on‐safe‐surgery‐laparoscopic‐vs‐open.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Tivey DR, Davis SS, Kovoor JG et al. Safe surgery during the coronavirus disease 2019 crisis. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2020; 10.1111/ans.16089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons . RACS Guidelines for the Management of Surgical Patients During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5137/racs‐guidelines‐for‐the‐management‐of‐surgical‐patients‐during‐the‐covid‐19‐pandemic.pdf

- 15. Australian and New Zealand Endocrine Surgeons . ANZES Executive Position Statement: Endocrine Surgery during the COVID‐19 Pandemic. Defining urgent endocrine surgical conditions. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5166/anzes-executive-position-statement.pdf

- 16. Australia and New Zealand Gastric and Oesophageal Surgery Association . ANZGOSA General Guidelines for Managing Patients with Oesophageal and Gastric Cancer During COVID‐19 pandemic. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: http://www.anzgosa.org/pdf/general-guidelines-og-cancer-managment-covid-new.pdf

- 17. Australian Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society . Position Statement from the AOFAS about Elective Surgery and Covid‐19. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.aoa.org.au/docs/default‐source/advocacy/aofas‐position‐statement‐‐‐covid‐19.pdf?sfvrsn=4f77dd04_2

- 18. COVIDSurg Collaborative . Elective surgery cancellations due to the COVID‐19 pandemic: global predictive modelling to inform surgical recovery plans. Br. J. Surg. 2020. 10.1002/bjs.11746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Australian and New Zealand Hepatic Pancreatic and Biliary Association . Considerations for HPB Surgeons in a Complex Triage Scenario COVID‐19. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://anzmoss.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Considerations-for-HPB-surgeons-in-a-complex-triage-scenario-COVID19_1.pdf

- 20. Shoulder and Elbow Society of Australia . SESA Position Statement on Surgery During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.aoa.org.au/docs/default-source/advocacy/sesa-position-statement-on-surgery-during-the-covid-19-pandemic.pdf?sfvrsn=727ddd04_4

- 21. Australian and New Zealand Hepatic Pancreatic and Biliary Association . ANZHPBA Guidelines for Management of HPB Surgery During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://anzmoss.com.au/wp-content/uploads/Guidelines-for-ANZHPB-Surgeons-during-the-COVID-pandemic-1-April.pdf

- 22. Spine Society of Australia . SSA COVID‐19 Surgery Position Statement and Category Definitions. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.aoa.org.au/docs/default‐source/advocacy/ssa‐covid‐19‐surgery‐position‐statement‐and‐categery‐definitions.pdf?sfvrsn=2677dd04_4

- 23. Australian Knee Society . AKS Position Statement, COVID‐19 Pandemic. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: http://aoa.e-newsletter.com.au/link/id/zzzz5e814ac7478de180Pzzzz508f44ad8c994136/page.html

- 24. The Australian Society of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery . ASOHNS Guidelines Addressing the COVID‐19 Pandemic. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5176/australian-society-of-otolaryngology-head-neck-surgery-covid-19-statement.pdf

- 25. Gastroenterological Society of Australia on behalf of the New Zealand Association of General Surgeons . Guide for Triage of Endoscopic Procedures During the COVID‐19 Pandemic. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.gesa.org.au/public/13/files/COVID-19/Triage_Guide_Endoscopic_Procedure_26032020.pdf

- 26. American College of Surgeons and COVID 19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium . COVID 19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care, Breast Cancer Surgery. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/covid19/guidance_for_triage_of_nonemergent_surgical_procedures_breast_cancer.ashx

- 27. Royal College of Surgeons of England . COVID‐19: Good Practice for Surgeons and Surgical Teams. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/standards-and-guidance/good-practice-guides/coronavirus/covid-19-good-practice-for-surgeons-and-surgical-teams/

- 28. American College of Surgeons, American Society of Anesthesiologists, Association of periOperative Registered Nurses . Create a Surgical Review Committee for COVID‐19‐Related Surgical Triage Decision Making. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/review-committee

- 29. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services . Non‐Emergent, Elective Medical Services, and Treatment Recommendations. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.cms.gov/files/document/cms-non-emergent-elective-medical-recommendations.pdf

- 30. Coccolini F, Perrone G, Chiarugi M et al. Surgery in COVID‐19 patients: operational directives. World J. Emerg. Surg. 2020; 15: 25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. American College of Surgeons . COVID‐19: Guidance for Triage of Non‐Emergent Surgical Procedures. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.facs.org/covid-19/clinical-guidance/triage

- 32. Joint Advisory Group on GI Endoscopy, British Society of Gastroenterology . Endoscopy Activity and COVID‐19: BSG and JAG Guidance. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.bsg.org.uk/covid-19-advice/endoscopy-activity-and-covid-19-bsg-and-jag-guidance/

- 33. The International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus . ISDE Guidance Statement: Management of Upper‐GI Endoscopy and Surgery in COVID‐19 Outbreak. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.isde.net/resources/Documents/Resources/ISDE_Position_Statement_COVID19_2020.03.30.pdf

- 34. Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, European Association for Endoscopic Surgery and other Interventional Techniques . SAGES and EAES Recommendations Regarding Surgical Response to COVID‐19 Crisis. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.sages.org/recommendations-surgical-response-covid-19/

- 35. American College of Surgeons . COVID 19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care, Emergency General Surgery. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/covid19/guidance_for_triage_of_nonemergent_surgical_procedures_general_surgery.ashx

- 36. Burke JF, Chan AK, Mummaneni V et al. Letter: the coronavirus disease 2019 global pandemic: a neurosurgical treatment algorithm. Neurosurgery 2020; 87: E50–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. American College of Surgeons . COVID 19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care, Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/covid19/guidance_for_triage_of_nonemergent_surgical_procedures_metabolic_bariatric.ashx

- 38. American College of Surgeons . COVID 19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care, Pediatric Surgery. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/covid19/guidance_for_triage_of_nonemergent_surgical_procedures_pediatric.ashx

- 39. The American Society of Breast Surgeons . Recommendations for Prioritization, Treatment and Triage of Breast Cancer Patients During the COVID‐19 Pandemic: Executive Summary, Version 1.0, The COVID‐19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. [Cited 12 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.breastsurgeons.org/docs/news/The_COVID‐19_Pandemic_Breast_Cancer_Consortium_Recommendations_EXECUTIVE_SUMMARY.pdf

- 40. American College of Surgeons . COVID 19: Elective Case Triage Guidelines for Surgical Care, Vascular Surgery. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.facs.org/-/media/files/covid19/guidance_for_triage_of_nonemergent_surgical_procedures_vascular.ashx

- 41. European Association of Urology . EAU Robotic Urology Section (ERUS) Guidelines During COVID‐19 Emergency. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://uroweb.org/wp-content/uploads/ERUS-guidelines-for-COVID-def.pdf

- 42. North American Spine Society . NASS Guidance Document on Elective, Emergent and Urgent Procedures. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.spine.org/Portals/0/assets/downloads/Publications/NASSInsider/NASSGuidanceDocument040320.pdf

- 43. Spanish Society of Surgery (AEC) . General Recommendations of Urgent Surgical Care in the Context of the COVID‐19 Pandemic (SARS‐CoV‐2) from the Spanish Association of Surgery (AEC). [Cited 15 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.aecirujanos.es/files/noticias/158/documentos/4_-_Recomendaciones_for_URGENT_Surgical_care_during_the_pandemic_COVID_19__v_2.pdf

- 44. Shared health Soins communs Manitoba . COVID‐19: Provincial Guidance on Management of Elective Surgery. [Cited 13 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://sharedhealthmb.ca/files/covid-19-elective-surgery.pdf

- 45. Australian Government . Coronavirus (COVID‐19) Current Situation and Case Numbers. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.gov.au/news/health‐alerts/novel‐coronavirus‐2019‐ncov‐health‐alert/coronavirus‐covid‐19‐current‐situation‐and‐case‐numbers

- 46. New Zealand Ministry of Health . COVID‐19 – Current Cases. [Cited 20 Apr 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/diseases-and-conditions/covid-19-novel-coronavirus/covid-19-current-situation/covid-19-current-cases

- 47. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons . Surgery Triage: Responding to the COVID‐19 Pandemic.

- 48. Australian Government . Impact of COVID‐19: Theoretical Modelling of How the Health System Can Respond. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2020/04/impact-of-covid-19-in-australia-ensuring-the-health-system-can-respond-summary-report.pdf

- 49. Aminian A, Safari S, Razeghian‐Jahromi A, Ghorbani M, Delaney CP. COVID‐19 outbreak and surgical practice: unexpected fatality in perioperative period. Ann. Surg. 2020; 272: e27–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. COVIDSurg Collaborative . Mortality and pulmonary complications in patients undergoing surgery with perioperative SARS‐CoV‐2 infection: an international cohort study. Lancet 2020; 396: 27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Lei S, Jiang F, Su W et al. Clinical characteristics and outcomes of patients undergoing surgeries during the incubation period of COVID‐19 infection. EClinicalMedicine. 2020; 21: 100331. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Doglietto F, Vezzoli M, Gheza F et al. Factors associated with surgical mortality and complications among patients with and without coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19) in Italy. JAMA Surg. 2020. 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.2713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chew MH, Koh FH, Ng KH. A call to arms: a perspective of safe general surgery in Singapore during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Singapore Med. J. 2020; 1: 10. 10.11622/smedj.2020049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Lippi G, Simundic AM, Plebani M. Potential preanalytical and analytical vulnerabilities in the laboratory diagnosis of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19). Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2020; 58: 1070–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Royal Australasian College of Surgeons . Guidelines for Personal Protective Equipment: A Rapid Review Commissioned by RACS. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://umbraco.surgeons.org/media/5302/2020-05-05-covid19-ppe-guidelines.pdf

- 56. Ross SW, Lauer CW, Miles WS et al. Maximizing the calm before the storm: tiered surgical response plan for novel coronavirus (COVID‐19). J. Am. Coll. Surg. 2020; 230: 1080–1091.e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Weissman GE, Crane‐Droesch A, Chivers C et al. Locally informed simulation to predict hospital capacity needs during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Ann. Intern. Med. 2020; 173: 21–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stein ML, Rudge JW, Coker R et al. Development of a resource modelling tool to support decision makers in pandemic influenza preparedness: the AsiaFluCap simulator. BMC Public Health 2012; 12: 870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Australian Government . Australian Health Protection Principal Committee (AHPPC) Statement on Restoration of Elective Surgery. [Cited 9 May 2020.] Available from URL: https://www.health.gov.au/news/australian-health-protection-principal-committee-ahppc-statement-on-restoration-of-elective-surgery

- 60. Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council (AHMAC) . National Elective Surgery Urgency Categorisation. Canberra: Australian Health Ministers' Advisory Council, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 61. New Zealand Ministry of Health Planned Care Sector Advisory Group . Increasing and improving Planned Care in accordance with the National Hospital Response (in press).

- 62. Brindle M, Gawande A. Managing COVID‐19 in surgical systems. Ann. Surg. 2020; 272: e1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Tan L, Kovoor JG, Williamson P et al. Personal Protective Equipment and Evidence‐Based Advice for Surgical Departments during COVID ‐19. ANZ Journal of Surgery. 2020; 90: 1566–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by a selection of General Surgical Societies/Associations, effective as of 17 April 2020.

Table S2. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by a selection of Orthopaedic Surgical Societies/Associations, effective as of 17 April 2020.

Table S3. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by a selection of Surgical Societies/Associations, effective as of 17 April 2020.

Table S4. Summary surgical triage guidance provided by international organizations, effective as of 17 April 2020.